The Royal Canadian Navy and the First World War

By the time the Canadian high commissioner communicated the British government’s view that the Royal Canadian Navy was irrelevant to the empire’s war effort, the First World War was already two months old. As disappointing as London’s response may have been to the officers at Naval Service Headquarters (NSHQ) in Ottawa, it reflected the pre-war naval policy—or lack of naval policy—of the Borden administration. Perley’s telegram was also a strong indication that many of the basic decisions about Canada’s naval defence during the war would be made by the Admiralty and not by Ottawa. Although London’s naval advice during the war was often inconsistent and its promises of assistance would usually prove empty, the Borden government was never willing to go against it or adopt a course of action put forward by its own, more informed naval professionals at NSHQ. In keeping with British wishes, Canada recruited and maintained a four-division corps of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) on the battlefields of France and Belgium—one that would gain a well-deserved reputation as one of the shock formations of the British Empire—but the Borden government was never willing to provide Canada’s navy with resources adequate to meet its wartime responsibilities. As a result, the remnants of Laurier’s fledgling naval service would have to safeguard Canada’s maritime interests with a rather motley collection of seconded civilian vessels, war-built trawlers, and drifters and, at war’s end, with a handful of American-manned motorboats and seaplanes on loan from south of the border.

Peter Rindlisbacher, HMCS Niobe at Daybreak, depicting the ship proceeding out to sea.

In anticipation of the British declaration of war on 4 August 1914, the RCN’s largest warship, the cruiser Niobe, was in dockyard hands at Halifax being fitted for duty (it would not emerge from drydock to begin its power trials until early September), while the navy’s other warship, Rainbow, based in the Pacific at Esquimalt, had already proceeded to sea. Under the terms of the Naval Service Act, both cruisers, despite their obsolescence, were placed at the disposal of the British Admiralty “for general service in the Royal Navy” once war was declared. The navy’s remaining duties were largely supervisory ones at the nation’s various ports, since the civilian crews of government vessels carried out most of the actual work. At Halifax, for instance, the navy’s wartime responsibilities consisted variously of: blocking the eastern passage into the harbour past MacNab Island; placing net defences, making minesweeping arrangements, and buoying the war channel; establishing an examination service; assuming control of the wireless station at Camperdown, and transporting censorship staff and militia detachments to other coastal wireless stations; and controlling traffic in the harbour. On August 12, the captain-in-charge of the port informed the director of the naval service, Rear-Admiral Charles E. Kingsmill, that “everything has been completed in revised defence scheme except buoying the channel for war,” while the progress in preparing Niobe for sea was reported as “satisfactory.”1

With the RCN’s largest warship alongside at Halifax, the first operational cruise of the war was made on the West Coast. Rainbow’s commanding officer, Commander Walter Hose, had been ordered on 1 August to prepare his cruiser for active service, because Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s China Squadron, which included the heavy cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, had departed the Far East for the eastern Pacific. Indeed, on 2 August, the Admiralty reported that the German cruiser Leipzig had left the Mexican port of Mazatlan on the morning of July 30, and Rainbow was instructed to proceed south at once to guard the trade routes north of the equator. Despite concerns about the obsolete gunpowder shells Rainbow carried for its two six-inch guns and the large number of Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reservists in its scratch crew, Hose shaped course south on August 5 after receiving further instructions from Ottawa to protect the British sloops Algerine and Shearwater as they made their way north from San Diego, California.

The Canadian cruiser arrived at San Francisco on the morning of August 7 intending to coal at the port. American officials strictly enforced U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s neutrality proclamation, however, and Rainbow was only allowed to embark some 50 tonnes. With his ship’s radius of action curtailed, Hose decided to patrol off San Francisco:

It appeared to me that it was my duty, being apparently so close to the enemy, to try and get in touch with him at once, consequently I got under way at midnight and proceeded in misty weather to a point on the three mile limit fifteen miles to the southward of San Francisco, from there I steamed slowly to the southward all that forenoon, the weather being foggy and clear alternately.2

HMCS Rainbow returns to Esquimalt with the captured German schooner, Leonor, May 1916.

Rainbow continued to patrol off the California port without sighting the enemy until the morning of 10 August when fuel concerns forced Hose to return to Esquimalt. The timing proved fortunate as Leipzig — whose 10 higher velocity 4.1-inch guns easily outranged Rainbow’s obsolete six-inch armament—appeared off San Francisco on August 11 and remained in northern California waters until sailing south on August 18. It was the closest the Canadian cruiser would come to intercepting its German adversary.

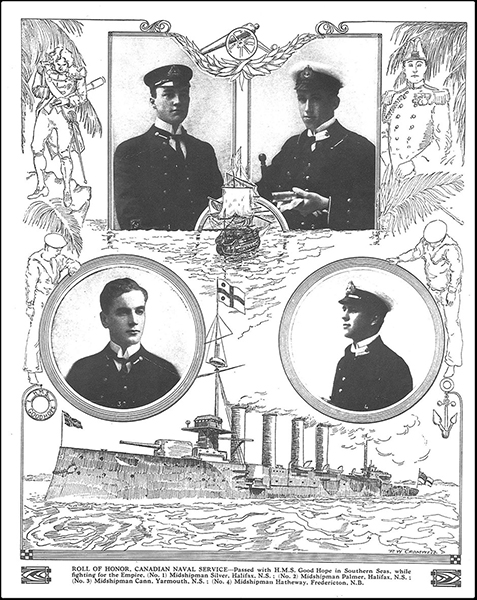

In the meantime, fears of the havoc enemy raiders might have on the relatively undefended West Coast had prompted the provincial government of British Columbia to purchase two submarines clandestinely from a Seattle, Washington shipyard. Commissioned as CC1 and CC2, the two boats were manned at Esquimalt by Canadian reservists together with a handful of experienced professionals. By the time the RCN submarines were operational, however, the German threat to the West Coast had largely passed. Concentrating his two heavy and three light cruisers off western South America by mid-October, von Spee easily defeated the first British naval force sent to engage him, Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Craddock’s squadron of two older armoured cruisers, a light cruiser, and an armed merchant cruiser. The Battle of Coronel, fought off the coast of Chile on the evening of 1 November 1914, ended with the sinking of both British armoured cruisers, but was most notable from a Canadian perspective because four RCN midshipmen, all recently assigned to Craddock’s flagship and killed along with the rest of the RN crew, were the first RCN casualties of the war. The victorious German squadron was subsequently intercepted and sunk by a powerful British force, which included the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, off the Falkland Islands on December 8. Following the British victory in the South Atlantic, the only real concern on the West Coast lay in the potential danger posed by German merchantmen in neutral ports should they be fitted out as armed commerce raiders. In that case, however, although it was over 20 years old, Rainbow was still faster than all but a few commercial vessels and adequately armed to subdue them.

HMCS Niobe in the Halifax drydock being readied for war, August 1914.

The potential threat of German merchantmen lying in America’s eastern ports was the RCN’s chief concern on the Atlantic coast. As mentioned, Niobe was already being fitted for sea when war was declared on 4 August. The obsolescent cruiser was scheduled to join the RN squadron on the North America and West Indies (NA and WI) Station to keep watch over the western North Atlantic shipping lanes, particularly their main focal point off New York, against a number of German ocean liners that had been fitted out as auxiliary cruisers. After emerging from drydock, Niobe was ready for a full power trial on September 1, and it remained only to crew it. The decision to pay off Algerine and Shearwater at Esquimalt freed their crews for service with the Canadian cruiser, including Captain Robert Corbett, the commanding officer of Algerine, who now assumed the same position in Niobe. Altogether some 16 RN officers and 194 ratings joined the cruiser’s crew. These were supplemented by 28 RCN and RNCVR officers, and 360 ratings. The crew was brought up to full strength when the government of Newfoundland agreed to assign one officer and 106 ratings from the Newfoundland Division of the Royal Naval Reserve to the ship. Very quickly, therefore, from October 1914 to July 1915, Niobe took its place in the regular rotation of British cruisers patrolling the American coast. Writing in 1944, its executive officer, Commander C.E. Aglionby, RCN, recalled that Niobe was part of “the blockading squadron of the Royal Navy off New York harbour, inside which there were thirty-eight German ships including some fast liners, which could act as commerce destroyers if they could escape”:

We boarded and searched all vessels leaving the harbour, and in the early days took off many German reservists who were trying to get back to Germany in neutral ships….We had to pass many things in neutral ships which we knew were destined for Germany, to be used against our men. One particular example I remember was a large sailing ship carrying a cargo of cotton bound for Hamburg, but this was not contraband at that time and we had to allow it to go on. It was very monotonous work, especially after the first few weeks when, owing to reports of possible submarine attacks, we had to keep steaming up and down, zig-zagging the whole time. After the first few weeks, owing to complaints in the American press by German sympathizers to the effect that we were sitting on Uncle Sam’s doorstep preventing people coming in and out, we had to keep our patrol almost out of sight of land.The American Navy were very friendly to us, and when their ships passed us they used to cheer ship and play British tunes.3

Canada’s first naval casualties: the four midshipmen embarked in HMS Good Hope who were lost with the ship at the Battle of Coronel, 1 November 1914.

By September 1915, however, the cruiser’s deteriorating condition meant that it had to be removed from operations, and was recommissioned as a depot ship at Halifax for the remainder of the war. It also served as a parent ship for vessels employed on patrol work and provided office space for the various Canadian naval staff officers employed at Halifax. Niobe’s new duties also reflected the changing nature of Germany’s guerre de course against merchant shipping as the enemy shifted its focus from surface raiders to U-boats. The annihilation of von Spee’s Pacific squadron at the Falkland Islands and the general ineffectiveness of other surface raiders in disrupting Allied trade during the war’s opening months led the German Admiralstab to launch an unrestricted submarine campaign against merchant shipping on 1 February 1915.

Despite a shortage of U-boats that could operate in British waters at any one time—an average of four in early 1915, only two of which were likely to be on station to the west of the British Isles—the results achieved by the German submariners more than made up for their small numbers. During the first seven months of the campaign, U-boats sank 470 ships totaling some 715,500 tonnes, including the large British passenger liner Lusitania on 7 May 1915. Against this background of sinkings in British waters, Admiralty intelligence alerted Naval Service Headquarters that German agents south of the border might attempt to establish supply bases for submarines along remote stretches of the Newfoundland and Canadian coasts. By late June the Canadian Navy’s chief of staff, Commander R.M. Stephens, proposed a scheme for 10 patrol vessels to watch the waters of the Gulf and the coast of Nova Scotia between Halifax, Cape Race and the Strait of Belle Isle. The five auxiliary patrol vessels already available—HMC Ships Canada, Margaret, Sable I, Premier, and Tuna—were typical of the warships the RCN was to employ during the war. The first two were fisheries patrol vessels that had at least been built along naval lines, while Premier and Sable I were civilian vessels chartered by the navy. Tuna, on the other hand, was a small, turbine- powered American yacht that was purchased by a wealthy Montreal playboy, J.K.L. Ross, and presented to the RCN as a gift. Ross later arranged the purchase of a second, larger turbine-yacht from the United States that was commissioned into Canadian service as HMCS Grilse. Armed with two 12-pounder guns and a torpedo tube, NSHQ recognized Grilse’s operational possibilities from the outset and the vessel was intended for employment near the Gulf ’s shipping lanes as the RCN’s primary offensive unit. Two other large American yachts, albeit ones with reciprocating engines, were also purchased and commissioned in mid-August as HMC Ships Stadacona and Hochelaga.

By late 1917, trawlers and drifters purpose- built in Canada were ready to join the East Coast Patrols.

In organizing the Gulf patrol, Kingsmill wisely decided to set it up as a command separate from Halifax. Undoubtedly concerned that the British might try to exercise de facto control of Gulf operations with little reference to Canadian needs or priorities, the Canadian naval director wanted to ensure that the patrol remained exclusively in NSHQ’s hands by placing in command an officer with his headquarters at Sydney acting under Ottawa’s direct orders. The work of the Gulf flotilla began in mid-July with Margaret and Sable keeping watch on the Cabot Strait, while the Canadian Navy hired civilian motorboats to patrol the shoreline. Command of the patrol was given to Captain F.F.C. Pasco, an officer who had been serving with the Royal Navy in Australia. After being rejected by the Australian army on the grounds of age, Pasco readily accepted Canada’s offer to command the Gulf patrol flotilla and arrived at Sydney on 5 September 1915.According to a junior RCN officer who served under him, Pasco “was a gruff old fellow who’s [sic] specialty was ‘finding fault.’ … For us this meant having every button on duty with no deviation from rules contained in the so-called Naval Bible, ‘King’s Rules and Regulations’ [sic].”4

The small force that Pasco found waiting for him in Sydney could not have inspired much confidence. The additional hiring of civilian motorboats to keep an eye on the many bays and inlets along the Gulf of St Lawrence coast at least gave the RCN a reason to maintain a presence in the area and investigate the numerous rumours and false sightings being reported by the anxious civilian population. A mix of Royal Navy and Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) officers and senior ratings gave the flotilla’s largely RNCVR crews a measure of naval experience and provided on-the-job instruction during patrols. As ad hoc a grouping of vessels as the Gulf patrol was, the quality of its warships would not be improved upon—despite NSHQ’s best efforts to do so—for the remainder of the war.

Although German U-boats had not crossed the Atlantic in 1915, the increasing volume of Canadian war supplies being transported to Europe suggested that enemy submarines would eventually operate in North American waters. In early March 1916, therefore, NSHQ asked the Admiralty what measures they would recommend with regard to naval patrols in 1916, and also what, if any, assistance the Admiralty could provide. London’s reply did not recommend any significant changes to the 1915 arrangements and indicated that no assistance should be expected from Britain in any event. Kingsmill believed that if the British were “unable to supply any additional vessels at present, it is very unlikely that they will ever be able to do so,”5 and suggested building destroyers for the RCN at the Canadian Vickers shipyard in Montreal. Both politicians and bureaucrats in Ottawa were well aware that the Montreal yard had assembled “H”-class submarines for the British government in 1915 and was currently constructing motor launches for the Royal Navy. Letting contracts in the spring of 1916 would allow Vickers to complete the destroyers by the fall of 1917. Although the Canadian destroyer proposal was viewed favourably as it made its way through the corridors of the Admiralty in April 1916, a sceptical First Sea Lord suggested that Canadian shipbuilding capacity might be better employed in constructing merchant ships, a view that was endorsed by the first lord, Sir Arthur Balfour. Without the Admiralty’s endorsement, Kingsmill’s destroyer plans were dead in the water. Having been elected with a naval policy that called for the scrapping of Laurier’s planned navy and replacing it with financial support for the Royal Navy, the Borden government would have needed a strong directive from London for it to have considered building sizable warships, even though the proposed destroyers would have given the RCN a far more effective naval force with which to combat the U-boat campaign that developed in Canadian waters in the summer of 1918.

Although the Canadian Navy was primarily occupied in deploying its makeshift patrol force to protect the East Coast shipping lanes in 1916, the RCN continued to maintain a naval presence in the Pacific where Rainbow, despite its obsolescence, performed useful reconnaissance work against German shipping activity along the coasts of Mexico and Central America. The Canadian cruiser, still under the command of Walter Hose, was earmarked for the operation because no other British ship was available. It spent the spring of 1916 patrolling the West Coast of Mexico and Central America, eventually capturing two German-owned schooners. The U.S.-flagged Oregon was boarded and seized on April 23 while the Leonor was taken on May 2, and Rainbow arrived at Esquimalt with its prize in tow on the morning of the 21st.

Despite Canada’s war effort being concentrated on its expeditionary force, there were a number of young Canadians who wished to serve in the navy instead of the army. Early in the war, NSHQ had arranged transportation for any RNR officers and men resident in Canada who wished to return to Britain, and had also assisted the Admiralty in enrolling men directly into British service. With the RCN preoccupied throughout 1915 with keeping the crews of its two cruisers up to strength and then with organizing and manning a patrol service in the Gulf of St Lawrence, it was not until early 1916 that the question of sending sailors overseas was raised once again. The Admiralty responded favourably to a February proposal put forward by the naval minister, suggesting that Canadians should be enrolled at British rates of pay for service in the RN’s auxiliary patrol. But British recruiters quickly discovered that Canadians were uninterested in joining the RN whose pay for an able-bodied seaman was only 40 cents a day, while the RCN paid 70 cents and the CEF $1.10 for similarly qualified men. Ottawa then offered to recruit an overseas division of the RNCVR and place the sailors at the disposal of the Admiralty. The personnel needs of the RCN’s expanded patrol forces during the final two years of the war, however, meant that a far greater proportion of RNCVR recruits remained in Canada than were sent overseas. As a result, while Ottawa’s original proposal had been to send up to 5,000 Canadians to the Royal Navy as part of the Overseas Division, only some 1,700 RNCVRs were sent across the Atlantic, while the majority, 6,300 volunteer sailors, served in Canadian waters during the war.

A view of the destruction caused on land by the Halifax Explosion.

Even as NSHQ was looking to assist the Royal Navy in European waters, North America’s vulnerability to submarine attack was dramatically brought home to both British and Canadian naval authorities by the sudden arrival of an unarmed German submarine freighter, U-Deutschland, off the coast of the United States in July 1916. The potential threat was reinforced when the combat submarine U-53 appeared off the Nantucket lightship on October 8 and proceeded to sink four merchant ships, totaling 15,355 tonnes, and the British-registered passenger ship Stephano bound from Halifax to New York with 146 passengers. In each case, the Germans adhered to accepted laws of war: they stopped the ship, examined its papers, and allowed the crew and passengers to take to lifeboats before sinking the vessel with either gunfire, scuttling charges, or torpedoes. With the USN destroyers on scene unable to intervene, aside from rescuing survivors, U-53 was free to conduct its attacks before setting course for Germany late that night.

The vulnerability of the North American shipping lanes was reinforced three weeks later when U-Deutschland undertook another commercial voyage. This third successful trans-Atlantic voyage by a German submarine finally convinced the Admiralty of the need to revise its advice regarding the RCN’s defence arrangements. On 11 November 1916, the British government informed the Canadian of its sudden reversal of policy. But other than noting that the present 12 vessels were insufficient and suggesting an expansion to 36 patrol vessels, the only actual British assistance was an offer “to lend an officer experienced in patrol work to advise the Newfoundland and Canadian governments as regards procuring and organizing vessels.”6

The 36-vessel auxiliary patrol now being advocated by the British government offered some protection to merchant ships in the immediate approaches to Saint John or Halifax during the winter shipping season, but did not provide for any effective escorts along the heavily-travelled Gulf of St. Lawrence route during the remainder of the year when Montreal resumed its place as Canada’s main Atlantic port. Moreover, the RCN was only able to make limited progress in acquiring additional auxiliary patrol vessels from the supply of suitable civilian vessels. Of the two government ships transferred from the department’s hydrographic survey, Cartier could manage a useful 12 knots, but the larger Acadia could make only eight. To these the Canadian Navy was only able to add the 320-tonne, 11-knot steamer Laurentian purchased from Canada Steamship Lines, and the 440-tonne, nine-knot Lady Evelyn transferred from the postmaster-general’s department later that spring. Looking to the United States, the RCN was able to purchase seven New England-built fishing trawlers, commissioned as PV I to PVVII, even though their eight-knot speed was best suited to minesweeping duties.

Since the 11 additional vessels still left the RCN well short of the 36 suggested by the Admiralty, the naval department approached Canadian shipyards to see if they could build auxiliary vessels for the patrol service. In mid-February 1917, contracts were let to construct a dozen 40-metre, 320-tonne Battle-class steam trawlers, six each at the Polson Iron Works shipyard in Toronto and the Vickers yard in Montreal—marking these inauspicious vessels as the first class purpose-built for the RCN. At the same time, the Admiralty decided to place orders for 36 trawlers and 100 wooden drifters with various Canadian shipyards, both classes to be capable of nine or 10 knots, with the former being armed with a single 12-pounder and the latter with a single six-pounder. In the event, shortages of labour and material delayed construction and the RCN did not begin to receive the vessels until late 1917.

In February 1917 the German high command had decided to gamble on victory by launching an unrestricted submarine campaign even though it risked bringing the United States into the war on the Allied side. Some 500 ships representing over 910,000 tonnes were sent to the bottom by the end of March, and in April the Allies lost 395 ships sunk totaling 800,933 tonnes, the highest shipping losses sustained in a single month during the war. It was a rate of loss that simply could not be sustained by the Allied merchant fleets. While successful in sinking ships, Germany’s gamble also produced the result it had feared the most when the United States declared war on 6 April 1917 as an “associate” power on the Allied side. As shipping losses mounted, a desperate Admiralty turned to a tactic it had previously resisted adopting—convoy. After several successful trial convoys, a comprehensive system was put in place over the summer. The first of the regular North American convoys, the “HH” series (Homeward from Hampton Roads) were started at four-day intervals on July 2. “HN” convoys (homeward from New York) began sailing at eight-day intervals on July 14. On June 22 the commander-in-chief, North America and West Indies station was informed that the Admiralty had decided to extend the convoy system to Canadian ports as well. The first of the “HS” convoys (homeward from Sydney), a total of 17 merchant ships, sailed from the Cape Breton port on July 10 commencing a regular eight-day cycle. A troopship “HX” convoy (homeward from Halifax) sailed for the first time on August 21 and included any merchant ships from New York or Montreal that were capable of maintaining 12.5 knots or more.

As successful as the introduction of convoy was in curtailing losses, its adoption also contributed to one of the country’s most devastating catastrophes. On the morning of 6 December 1917, a Belgian Relief Committee ship, SS Imo, was proceeding out of Bedford Basin on its way to New York just as a French merchant ship, Mont Blanc, was entering the harbour to await the next HX convoy. New York shipping agents had loaded the 2,840- tonne Mont Blanc with over 2,360 tonnes of wet and dry picric acid, TNT, and gun cotton. In addition, drums of flammable benzol were stacked three or four high on its fore and after decks. Running behind its scheduled departure, Imo was steaming south at high speed down the wrong side of the shipping channel when it collided with the slow-moving French steamer, a kilometre north of the naval dockyard. With some of the benzol drums rupturing and bursting into flame from the force of the collision, the French sailors quickly abandoned their burning ship to drift aground on the Halifax shore. Twenty minutes after the initial collision, as RCN sailors from Niobe raced to fight the fire, the munitions ship exploded in the largest detonation of manufactured explosives to that time.

The massive blast killed some 1,600 people, most of them instantaneously, and injured another 9,000, many of whom were cut by flying glass as they stood at windows looking out at the burning ship. It also left some 6,000 Haligonians homeless in the heavily damaged northeastern section of the city. About 700 metres to the south, the naval dockyard suffered extensive damage as well. For the RCN, however, the Halifax explosion’s greatest impact resulted from the public’s desire to assign blame to someone in authority. Although NSHQ was well aware that the main cause of the disaster had been the dangerous loading of Mont Blanc at New York and its subsequent routing to Halifax for convoy, it was determined that the Canadian government did not have jurisdiction to investigate the Admiralty. As a result, the public enquiry chaired by Judge Arthur Drysdale was unable to investigate the circumstances of the French ship until after its arrival at Halifax, a decision that excluded the Admiralty’s culpability from the proceedings while placing the actions of RCN officers under the public’s microscope. In the face of the understandably intense anger residents of Halifax felt because the disaster that happened, and ignoring the actual circumstances of the collision, the inquiry placed the full blame on the captain and pilot of the Mont Blanc, but also found the RCN’s chief examination officer to be guilty of neglect in not keeping himself fully acquainted with the movements of vessels in the harbour.

Despite the black eye the Canadian Navy received as a result of Drysdale’s findings, NSHQ’s biggest problem in early 1918 was the need to plan for the upcoming shipping sea- son without having a single effective anti-submarine vessel in its patrol force. In January, the Admiralty had provided Ottawa with a candid assessment of the likely scale of attack and the forces the RCN would need to meet it. Anticipating one or two long-range submarines to be operating off the Canadian coast at any one time, London stated that six destroyers, six four-inch-gunned fast trawlers, 36 additional trawlers, and 36 drifters would be required to supplement the RCN’s existing patrol force and meet the threat. The Admiralty telegram also assured Ottawa that the most important warships in the scheme, the six destroyers and the six fast trawlers, would be supplied either from the RN or the USN. Based on London’s promise of assistance, a relieved NSHQ set about planning its first adequate defence scheme of the war — only to have the rug pulled out from under them a few weeks later. In mid- March the Admiralty tersely informed Ottawa that the promised fast trawlers would not be sent, while the question of the six destroyers “should the necessity for them arise, is being discussed by [the British] C-in-C [NA&WI] with United States naval authorities.”7

As a result, the navy once again had to contemplate defending Canada’s shipping lanes with only slow, inadequately-armed auxiliary vessels, trawlers, and drifters. The arrival of the Canadian-built trawlers and drifters at Halifax and Sydney in June and July 1918 finally allowed the captain of patrols to expand his defence schemes for the approaches to the two convoy assembly ports. As a result, Captain Hose, who had been in charge of the East Coast patrol force since the previous August, had to draw up yet another defence scheme in early June. Although the navy would not have the 12 destroyers and fast trawlers that had been central to the scheme devised by Hose and Kingsmill in March, limited reinforcements had arrived from the United States Navy in the form of six submarine chasers—motorboats armed with depth charges—and two very old torpedo boats. The threat to Canada’s East Coast shipping lanes was emphasized when the first enemy submarine, U-151, began sinking merchant vessels off the coast of the United States in late May and into June. By mid-July a second U-cruiser, U-156, was also reported heading for New York where it laid mines in the port’s approaches. On July 19 the 12,440-tonne American armoured cruiser USS San Diego sank after hitting one of the U-boat’s mines off Long Island with the loss of six sailors. It was the largest American warship lost during the war.

On July 22, U-156 made a bold daylight attack on a tug and four barges only five kilometres off Cape Cod in front of thousands of stunned, sunbathing onlookers. Any doubts that the German submarine was moving into Canadian waters rather than returning to the busier shipping lanes off New York were removed on August 2 when the U-boat sank the Canadian four-masted schooner Dornfontein 40 kilometres south-southwest of Grand Manan Island at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy. The U-boat continued east across the south coast of Nova Scotia where it sank four American and three Canadian fishing vessels between 3 and 5 August before turning north and heading for the approaches to Halifax. Late on the morning of August 5, U-156 torpedoed the tanker Luz Blanca 58 kilometres south- southwest of the Sambro lightship.

While the Halifax command made a creditable effort in flooding the area of the attack with every trawler, drifter, and submarine chaser it had available (and U-156 spent the next two weeks cruising in U.S. waters), the Luz Blanca’s sinking convinced the naval authorities to shift the convoy assembly port to Quebec City for the remainder of the war. With the Halifax shipping lanes virtually devoid of traffic following the shift of convoys to the St. Lawrence, the only ships left in the area when U-156 returned to the Nova Scotia coast on August 18 were the many fishing vessels plying their trade on the Canadian and Newfoundland banks. These were, in fact, a target, and the German submariners had come prepared to adopt an entirely new tactic in their attacks against the fishing fleets.

Moving northeast parallel to the coast, U-156 was some 110 kilometres south-southwest of Cape Canso at noon on August 20 when its crew captured the Canadian fishing trawler Triumph. Arming the trawler with a three-pounder gun they had brought with them for the purpose and sending its Canadian crew off in a lifeboat to row for shore, the Germans set about capturing and sinking four more fishing vessels that afternoon. After spending the night of 20–21 August steaming northeast at the trawler’s top speed, U-156 and Triumph captured and sank two more fishing vessels at dawn on the 21st, 80 kilometres east-south- east of Cape Breton Island. The trawler in all probability was scuttled during the morning of the 21st, and the German submarine disappeared until 0130 hours on August 25 when it attacked the British steamer Eric about 115 kilometres west-northwest of the French island of St. Pierre. Then around 0600 hours U-156 overtook the Newfoundland schooner Wallie G. 40 kilometres west of Saint-Pierre.

Turning south-southwest, the U-boat had travelled approximately 30 kilometres when it spotted a group of four fishing schooners at anchor about a kilometre apart from each other. As U-156 was in the process of boarding and sinking the schooners, however, the vessels were spotted from the bridge of HMCS Hochelaga, part of a four-ship Canadian patrol searching for the German submarine. Rather than steering directly for the enemy, however, Hochelaga’s captain, Lieutenant R.D. Legate, turned back to the flotilla leader, urging caution and suggesting they await reinforcements. Ignoring Legate’s timidity, the flotilla leader in HMCS Cartier steamed at top speed for the U-boat’s reported position only to find that it had submerged after sinking the remaining schooners. Having failed immediately to close with the U-boat upon sighting it, Hochelaga’s captain was placed under arrest and court martialed at Halifax in early October. In view of the overwhelming evidence of a loss of nerve in the face of the enemy, Legate was found guilty and sentenced to dismissal from the navy with the forfeiture of his commission, war service gratuity, medals, and other benefits. Following this easy evasion of the Canadian flotilla, U-156 boarded and sank another Canadian fishing schooner, Gloaming, 118 tonnes, 130 kilometres southwest of Miquelon Island on August 26 before heading for home. Alone among the U-boats that operated off the North American coast in 1918, however, U-156 failed to return safely to Germany, disappearing on September 25, most likely a victim of the British mine barrage to the west of Fair Isle. Nevertheless, Legate’s actions on August 25 were a rather sorry conclusion to the RCN’s only direct encounter with an enemy warship during the course of the war.

Naval Air Station Dartmouth was established in the summer of 1918 as a base for the planned RCN Air Service, but only U.S. Navy HS-2L flying boats such as this were available before the war ended.

Even as the East Coast escort fleet was fanning out across the fishing banks to warn schooners of the presence of U-156, a second U-boat appeared off Nova Scotia. After operating south of New York, U-117 began its homeward voyage, stopping the Canadian schooner Bianca approximately 275 kilometres southeast of Halifax on August 24. But the attempt to sink the vessel with bombs failed when its tobacco cargo swelled with seawater and plugged the holes in the hull. Bianca was taken in tow by a Boston fishing schooner three days later and successfully brought into Halifax. The delay in survivors reaching shore, occasioned by the greater distance U-117 was operating from the coast, meant that naval authorities could not organize an effective response to its activities. By the time Halifax received word of the attack on Bianca, for instance, the U-cruiser had already sunk the American fishing trawler Rush on the morning of August 26, about 260 kilometres east-southeast of Canso and 170 kilometres south-southwest from where U-156 sank Gloaming that same morning. The next day U-117 torpedoed and sank a 2,320-tonne Norwegian merchant ship 175 kilometres southwest of Cape Race. On the evening of August 30, the U-boat overhauled two Canadian fishing schooners travelling in company and sank them with bombs 450 kilometres northeast of St. John’s. Fortunately, the abandoned fishermen were picked up by a passing steamer two days later and brought ashore while the submarine arrived safely in Germany in late October.

The Canadian Navy’s meagre anti-submarine forces also received a welcome reinforcement at the end of August. Throughout the spring and summer NSHQ had been attempting to organize a naval air service to operate patrol aircraft along the coastal shipping lanes. Since Canadian naval airmen had to be trained for the new service, the U.S. government agreed to send U.S. Navy aircraft and crews to Nova Scotia to man airbases at Halifax and Sydney in the meantime. An advance party of Americans arrived at Halifax on August 5. They brought portable hangers with them to begin the task of establishing a temporary aerodrome at Baker Point, on the Dartmouth side of the harbour. After receiving four Curtiss HS-2L flying boats by rail from the United States, the American airmen began air patrols off Halifax at the end of August. Meanwhile, a similar detachment of U.S. Navy flying boats assigned to the Sydney air station began their first air patrols off Cape Breton in mid-September. While the American patrols were being organized, the call for Canadian recruits for the new air service was sent out to newspapers on August 8, even though the government did not officially approve the Royal Canadian Naval Air Service (RCNAS) until September 5. Sixty-four RCNAS volunteers were sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston in late September and early October to commence aircrew training, while a third contingent of RCNAS cadets followed at the end of October. Another 12 RCNAS cadets and six RCN petty officers sailed to Britain in early October to begin airship training. The war ended, however, before any of the RCNAS airmen could complete their training.

Even as U-156 and U-117 departed Canadian waters at the end of August, the U- Deutschland, refitted and recommissioned as U-155, arrived in mid-September and laid a series of mines some 10 to 15 kilometres southwest of Chebucto Head and Sambro Island, at the entrance to Halifax Harbour. As well as being hampered by the fog that normally occurred off Nova Scotia during the summer months, the German submarine recorded having to interrupt its work after spotting destroyers and patrol vessels in the shipping lanes off the Sambro lightship—undoubtedly Grilse, deployed in the approaches along with the three USN submarine chasers as part of the port’s defences. After lying 20 kilometres off the coast during the night of 18–19 September, the U-cruiser made its way to Sable Island in an effort to cut some of the telegraph cables linking Canada to Britain, but did not waste much time on the effort, cutting only one cable before heading for U.S. waters. On October 17, U-155 sank the 6,130-tonne U.S. freighter Lucia as it was steaming in an unescorted convoy from New York to Marseilles, France, making it the last ship sunk in North American waters during the war.

In view of the complete absence of destroyers from the Canadian Navy’s order of battle, the fact that German submarines did not sink a single ship in convoy is a testament both to the effectiveness of shifting Halifax convoys to Quebec and to the RCN’s ability to get the most out its armed yachts, submarine chasers, trawlers, and drifters. The three merchant ships actually sunk in Canadian waters were all attacked while proceeding independently as, indeed, were most of the ships sunk off the U.S. coast. The only other victims in Canadian waters were the 15 small fishing schooners and trawlers sunk by U-156 and U-117 between the 20th and 30th of August. While there is no denying the success achieved by shifting the convoy assembly port to Quebec, the decision was an obvious one for the naval authorities to have made. With over 80 percent of Canadian-bound transports and liners having to journey up the St. Lawrence to load at Montreal in any event, the use of Halifax as an assembly port made little sense within the Canadian transportation network—of which the convoy system was an extension—and simply added 650 kilometres to a merchant ship’s voyage, all of it in the very waters that were most exposed to U-boat attack. Protecting the fishing fleets, however, was more problematic. Lacking radios, the unarmed schooners could not alert naval authorities of events until the crews rowed ashore, 12 to 24 hours after they had been attacked. As a consequence, the Canadian Navy could only see that word of the threat was spread across the various fishing banks even as their inability to intercept any U-boats (aside from Hochelaga’s encounter) made the RCN appear useless to many in the Maritimes. Nonetheless, Canadian naval officers were privately relieved that the U-boats had attacked vulnerable fishermen while ignoring the far more valuable Canadian convoy traffic.

Throughout the First World War, the RCN was squeezed between the Admiralty’s relative indifference to Canadian naval defence and Prime Minister Borden’s unwillingness to accept NSHQ’s advice unless it had London’s stamp of approval. The result was the situation in which the Canadian Navy found itself in 1918, facing the six-inch guns of U-cruisers with a fleet composed primarily of slow trawlers and drifters armed with weapons half the size of the enemy’s. Despite the handicaps imposed on it, the RCN’s war experience was not without some success. From the tiny, prewar remnants of Laurier’s navy, a total of 8,826 Canadian personnel served in the RCN during the war: 388 RCN officers and 1,080 RCN ratings, and 745 RNCVR officers and 6,613 RNCVR ratings. Another 90 RN and RNR officers and 583 ratings served with the RCN for a grand total of 9,499 sailors. Of these totals, 190 men in RCN service were killed in action, died of wounds, or died of disease or accident, the latter category including those sailors who were killed in the Halifax explosion. Although a much smaller service, the First World War navy’s fatality rate of two percent was, in fact, identical to that sustained by the RCN in the Second World War. While the prewar cruisers Niobe and Rainbow were the navy’s largest warships, the RCN employed 130 commissioned vessels on the East Coast during the war and another four in the Pacific. Nonetheless, there was no escaping the fact that the RCN emerged from the war with a tarnished reputation in the eyes of the Canadian public. Not only had the navy been saddled with a portion of the blame for the Halifax explosion, but the decision by the Germans to attack the fishing fleet also amounted to a direct, if unintended, attack on the RCN’s already limited public credibility. As the officer who would lead the post-war Canadian Navy for a decade and a half, Captain Walter Hose recalled in later life that the navy had to endure “scathing—you might say scurrilous—ridicule for years in the press and in parliament, against the navy itself, which was trying its best, making bricks without straw, to maintain the highest efficiency possible and which could not defend itself, it was indeed discouraging.”8 The discouragement reflected in Hose’s statement, however, also served to foster a determination among many of the RCN’s younger officers to see that the navy would never again be relegated to the status of afterthought in future Canadian conflicts.

Author: William Johnston

1 DHH, 81/520/1440–5,Vol. IV, “Defensive Measures—1914. Reports on Situation. Copies for Chief of Staff,” 12 August 1914.

2 DHH, 81/520/8000,“HMCS Rainbow,” Vol. 2, Hose to Senior Naval Officer Esquimalt, Report of Proceedings, 17 August 1914.

3 Aglionby’s account is quoted in Gilbert N. Tucker, The Naval Service of Canada (I) (Ottawa: The King’s Printer, 1952), 243–44.

4 DHH, 81/520/8000, HMCS Protector [Base],W. McLaurin to E.C. Russell (Naval Historian), 11 February 1963.

5 LAC, RG 24,Vol. 4020, Kingsmill, Memorandum for the Deputy Minister, 17 April 1916.

6 LAC, RG 24,Vol. 4031, Colonial Secretary to Governor General of Canada, 11 November 1916.

7 LAC, Admiralty to Naval Ottawa, 16 March 1918.

8 DHH, Hose, BIOG file, Rear-Admiral Walter Hose, “The Early Years of the Royal Canadian Navy,” 19 February 1960.