The Royal Canadian Navy and Overseas Operations (1939-1945)

Stepping Forward and Upward

The Royal Canadian Navy’s greatest contribution in the Second World War was the role it played in the Battle of the Atlantic, the grim and unrelenting struggle against the German U-boats, which is the subject of the next chapter. What is often over-looked, however, is that the RCN also manned a variety of warships, from light cruisers to landing craft, which carried out many different tasks in European and Pacific waters. The RCN’s participation in surface warfare in these theatres was primarily driven by the ambition of Naval Service Headquarters in Ottawa to build up a “balanced fleet” or “blue water navy” that would be the foundation of a post-war service so strong that never again would it face possible dissolution as it had in the 1920s.

When war broke out in September 1939, NSHQ viewed the most dangerous threat as being large surface raiders, not submarines, and to counter this threat it wished to obtain powerful fleet destroyers of the Tribal class. In the winter of 1939-40 an arrangement was made with the Admiralty in London for Canada to produce escort vessels for the Royal Navy in return for British construction of four Tribal-class vessels in the United Kingdom. Until these ships were completed, NSHQ arranged for the conversion of three large passenger ships—Prince David, Prince Henry, and Prince Robert—as auxiliary cruisers, and while the seven destroyers of the pre-war fleet were employed on convoy duty in the Atlantic the “Prince” ships mainly operated on the Pacific coast. When the fall of France in June 1940 brought the U-boats to the Atlantic littoral, the RCN became increasingly involved with the North Atlantic but NSHQ never entirely relinquished its ambition to man larger warships.

As the first of the Tribals would not commission until late 1942, this ambition could not be realized in the short term. During the early part the war, however, many Canadian naval officers and seamen gained valuable experience by serving with the Royal Navy. The full story of their activities has never been properly told, but it should be emphasized that Canadian sailors served at sea in every theatre of war in appointments ranging from the conventional to the extreme.

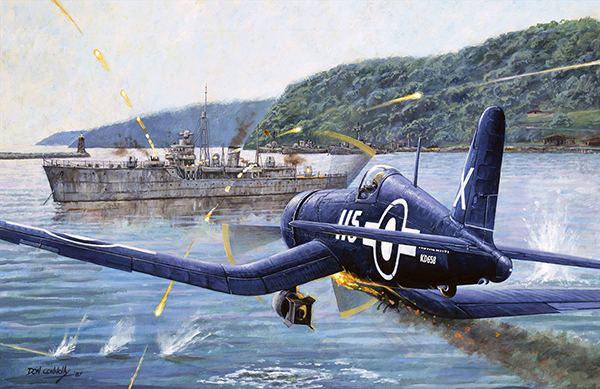

Donald Connolly, Finale, picturing the action in Onagawa Bay, Japan, 9 August 1945, from which Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray, VC, DSC, was posthumously awarded the RCN’s only Victoria Cross.

To provide just a few examples, Midshipman L.B Jenson, RCN, was in the battlecruiser HMS Renown when it engaged the German capital ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off Norway in April 1940. Lieutenant R.W. Timbrell, RCN, received a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for his service at Dunkirk in June 1940 while Sub-Lieutenant G.H. Hayes, RCNVR, survived being sunk in the same evacuation. Sub-Lieutenant G. Strathey, RCNVR, was a radar officer on the cruiser HMS Ajax when it sank three Italian destroyers in the Mediterranean in October 1940. Lieutenant S.E. Paddon, RCNVR, was a radar officer in the battleship HMS Prince of Wales when it fought the Bismarck in the spring of 1941 and survived his ship’s sinking off Malaya seven months later. Five Canadian officers were lost in the cruiser HMS Bonaventure when it was sunk off Crete in March 1941 and Lieutenant C. Bonnell, DSC, RCNVR, died in a Chariot “human torpedo” during a raid on Sardinia in December 1941. Surgeon-Lieutenant W.J. Winthrope, RCNVR, was killed in the daring commando attack on Saint-Nazaire in March 1942. Lieutenant J.H. O’Brien, RCN, witnessed the massive Allied amphibious landings in Sicily and Italy in 1943. Sixty Canadian ratings were serving in HMS Belfast when it participated in the sinking of the Scharnhorst in the Barents Sea in December 1943. Lieutenant R.H. Lane, RCNVR, served in the British heavy cruiser HMS Glasgow, Lieutenant-Commander F.H. Sherwood, RCNVR, was captain of the submarine HMS Spiteful operating in the Indian Ocean in 1945, while Captain H.T.W. Grant, RCN, commanded the cruiser HMS Enterprise in 1943-44. Lieutenant F.R. Paxton, RCNVR, was radar officer in the destroyer HMS Venus in May 1945 when it detected the Japanese heavy cruiser Haguro at the extreme range of 55 kilometres, a contact that ended with the enemy’s destruction. Perhaps one of the most unusual wartime jobs was that of Lieutenant-Commander B.S. Wright, RCNVR, as commander of a special operations detachment in central Burma in 1945 whose job was to swim across the Irawaddy River at night to raid the enemy.

Two branches of the Royal Navy in which Canadians formed a substantial presence were coastal forces and naval aviation—largely because NSHQ permitted Britain to recruit in Canada for these specialties. By 1943 more than 100 RCN officers were serving in coastal forces, commanding small but heavily-armed fast attack craft in the Channel and the Mediterranean. Their exploits were remarkable. Lieutenant-Commander T.G. Fuller, RCNVR, was awarded the DSO and two bars for operating against enemy warships in the Adriatic, while Lieutenant R. Campbell, RCNVR, participated in commando raids on Rommel’s troops in North Africa. Four young RCNVR officers, Lieutenants J. Davies, W. Johnston, R. MacMillan, and J.M. Ruttan, became responsible for mine clearance in Tobruk during the siege of 1941-42, while Lieutenant-Commanders G. Stead and N.J. Alexander, RCNVR, each commanded British coastal forces flotillas in the Mediterranean. One of the most outstanding feats accomplished by a Canadian was the action fought in May 1943 between MGB 657, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander J.D. Maitland, RCNVR, and a surfaced German U-boat—not only did Maitland beat off the enemy’s attack but so distracted the submarine’s bridge crew that it accidentally rammed another U-boat, sinking both vessels. Lieutenant A.G. Law, RCNVR, took part in an attack on the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau when they made the “Channel Dash” in February 1942. As Law attempted to avoid the attentions of German E-boats and destroyers that were determined to sink his fragile motor torpedo boat (MTB) before he got within torpedo range, his coxswain drew his attention to the sky: “Sir, aircraft with two wings—they must be British!”1 And they were, for overhead were five Swordfish torpedo planes flying in to make their own effort against the enemy battle cruisers. All five were shot down (and the German battlecruisers made it through).

Lieutenant-Commander G.C. Edwards, RCNVR, flew one of the antiquated aircraft that made this attack but survived to eventually command a squadron of Swordfish in the Fleet Air Arm. Edwards not only survived crashing a “Stringbag” (as these biplanes were termed) in the Mediterranean, he was one of the few pilots to survive a ditching in the frigid Arctic Ocean when his carrier escorted a Murmansk convoy. Lieutenant-Commander D.R.B. Cosh, RCNVR, commanded a squadron of the more modern Wildcat fighters in the escort carrier HMS Pursuer that participated in a strike against the German battleship Tirpitz in April 1944. Lieutenant-Commander R.E. Jess, RCNVR, commanded a Fleet Air Arm squadron of Avengers operating with the British Pacific Fleet against Japanese targets in 1945. There were a number of Canadian naval fighter pilots in the Pacific. Lieutenants D.J. Sheppard, RCNVR, and W.H.I. Atkinson both scored five kills in this theatre, and three of Atkinson’s victories were difficult night interceptions. Lieutenant D.M. Mcleod, RCNVR, survived miraculously almost unscratched when the engine of his Corsair failed on take-off, with the result that it cartwheeled several times—nose over wing over tail—on the water. Lieutenant A. Sutton, RCNVR, was posted missing in his Corsair during a raid on Sumatra in 1945. Lieutenant R.H. Gray, RCNVR, also flew Corsairs and his courageous attack on a Japanese destroyer in August 1945 brought a posthumous award of the only Victoria Cross earned by the RCN during the war. One of Gray’s squadron mates, Lieutenant G. Anderson, RCNVR, was killed in the same attack when his badly-damaged Corsair crashed while landing on their carrier, HMS Formidable. Anderson was the last member of the Canadian Navy to die in the Second World War.

The RCN also made a substantial contribution to the Combined Operations service, the organization created to carry out raids on occupied Europe and develop the specialized techniques required to conduct the large amphibious landings that marked the latter years of the war. In early 1942, 50 officers and 300 ratings proceeded to Britain to form two flotillas of landing craft. On 19 August 1942, 15 officers and 55 ratings from this group were with British landing craft flotillas that participated in Operation Jubilee, the ill-fated raid on Dieppe that cost the Canadian army nearly 3,000 casualties, or about 65 percent of the troops that took part. In a letter home written shortly afterward, Sub-Lieutenant D. Ramsay, RCNVR, provided a dramatic kaleidoscope of the images he had witnessed that terrible day, including:

a German armed trawler blown clear out of the water by one of our destroyers; a five-inch shell right through from one side to the other on the boat next to me without exploding; the boat officer, Skipper Jones, RNR (ex-Trawlerman as you can guess) screaming invectives at the Jerry and coming out once in a while with the famous Jonesian saying, “get stuffed;” a large houseful of Jerry machine gunners pasting hell out of anybody who dared come near the beach; a Ju 88 whose wing was cut in half by AB [Able-Bodied Seaman] Mitchinson of Ontario in the boat astern; a plane swooping down low behind a destroyer and letting go a 2000 lb. bomb, which ricocheted over the mast and burst about 10 yards on the starboard bow; peeking over the cox’ns box and looking into the smoking cannon of an Me 109. I’m here to state that that was close.2

Organized as four distinctly RCN flotillas, Canadian Combined Operations personnel then took part in Operations Torch (the landing in North Africa in November 1942), Husky (the Sicily landing in July 1943) and Baytown (the Italy landing that September). The achievements of the Canadian flotillas were almost unknown in Canada, much to the chagrin of NSHQ, which became determined that the same case would not apply with the RCN’s Tribal-class destroyers when they entered service.

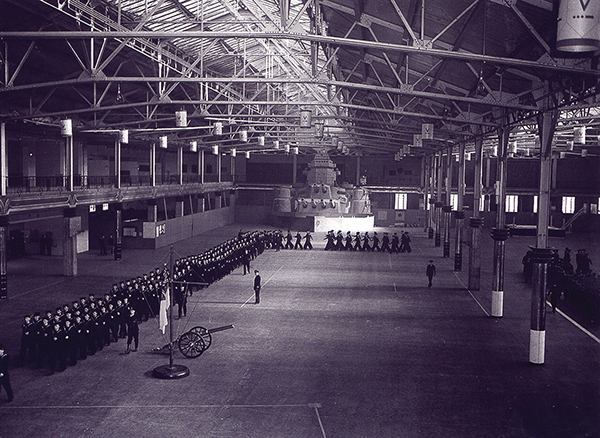

The war the navy expected: recruits at HMCS York, February 1942, doing close order drills in front of a full-size mock-up of a King George V-class battleship.

The first of these warships, HMCS Iroquois, was commissioned in November 1942 and was followed, over an eight-month period, by HMC Ships Athabaskan, Haida, and Huron. Armed with six 4.7-inch guns, two four-inch high-angle guns, four 21-inch torpedo tubes, and a variety of smaller anti-aircraft weapons, these big, graceful and powerful destroyers were intended not only to be the RCN’s striking force overseas, but also the nucleus of a post-war fleet. As it was, NSHQ narrowly stickhandled around a proposal by Prime Minister Wiliam Lyon McKenzie King that the Tribals be either employed on the North Atlantic convoys or for the defence of the Pacific Coast. “The Tribal is essentially a fighting Destroyer,” advised Commander H.G. DeWolf, Director of Plans, and would be wasted in any task other than that for which it had been designed. It was his opinion that the best course was to put the Tribals “under British operational control” where they could “contribute to the general cause.”3 Fortunately, this logic won the day and the four ships spent their wartime career with the RN’s Home Fleet where they carved out an impressive fighting record.

After working up and overcoming technical and personnel problems, Athabaskan and Iroquois saw their first action in the Bay of Biscay. The “Biscay Offensive” of the summer of 1943 was intended to catch and destroy U-boats transiting from their French bases to the North Atlantic but it enjoyed mixed success, particularly as Allied warships were within range of German shore-based aircraft. On 27 August, Athabaskan was operating in company with the destroyer HMS Grenville and the sloop HMS Egret when it was attacked by a new weapon—a radio-controlled “glider bomb,” actually a missile launched and guided by aircraft. As Athabaskan’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander G.R. Miles, RCN, reported, 19 Dornier 217 bombers approached and,

the three leading aircraft dropped their rocket bombs almost simultaneously; two were failures and the third, never deviating from its course for an instant, came straight for Athabaskan’s bridge. It was a magnificent shot and no dodging it. Striking the port side at the junction of B gun deck and the wheelhouse, it passed through the chief petty officers’ mess and out the starboard side where it exploded when twenty to thirty feet clear of the ship.4

Another bomber targeted Egret, which was hit and sunk. Suffering heavy damage but mercifully few casualties, Athabaskan was able to limp back to Plymouth to spend a lengthy period in drydock before being again fit for service.

The powerful Tribal-class destroyers Haida and Athabaskan steam in formation in the English Channel, spring 1944.

In November 1943 the three operational Tribals were ordered north to Scapa Flow, the barren and isolated Home Fleet base in the Orkneys, to work the “Murmansk Run,” escorting and screening convoys from Britain to Russia. From their inception in August 1941 to the end of the war, these convoys were the most dangerous operations carried out by the Allied navies, and losses in both merchant and warships were heavy as they took place within easy range of German bases in Norway. The Arctic convoys faced not only U-boats and aircraft, but also major fleet units—including the battleship Tirpitz, sister ship to the Bismarck—as well as terrible weather, rough seas, and extreme cold. Although the Murmansk Run was vital to the Russian war effort, it was not a popular service and Lieutenant P.D. Budge, RCN, of Huron explains why:

It seemed that gales were forever sweeping over the dark, clouded sea. The dim red ball of the sun barely reaching the horizon as the ship pitched and tossed, the musty smell of damp clothes in which we lived, the bitter cold, the long, frequent watches that seemed to last forever. This on a diet of stale bread, powdered eggs and red lead [stewed tomatoes] and bacon. The relief to get below for some sleep into that blessed haven—the comforting embrace of a well-slung hammock. There was no respite on watch for gun, torpedo or depth-charge crews as every fifteen minutes would come the cry “For exercise all guns train and elevate through full limits”—this to keep them free of ice.….The watch below would be called on deck to clear the ship of ice—the only time the engine room staff were envied. Each trip out and back seemed to last an eternity with nothing to look forward to at either end except that perhaps mail would be awaiting us at Scapa Flow.5

In late December 1943, Haida, Huron, and Iroquois formed part of the covering force for Convoy JW 55B, which was attacked by the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst. The Canadian vessels were not directly involved in the action but were long-distance witnesses by radio of the destruction of the Scharnhorst on Boxing Day 1943.When they anchored in the approaches to Murmansk two days later, their ships’ companies held a belated Christmas celebration, and in Haida one of its officers remembered, “the whole mess deck was draped with signal flags; a bottle of beer at each man’s plate; the candles throwing a pleasant light; and practically everyone drunk.”6

As the Tribals began operations during 1943, NSHQ made impressive strides toward achieving its plan of creating a balanced fleet that would survive inevitable post-war defence cutbacks. The RCN’s progress toward this bright, shining goal was accelerated by four factors. First, 1943 saw the climax of the Battle of the Atlantic and Allied dominance over the U-boats, allowing the RCN for the first time since 1940 to “draw breath” and contemplate the future. Second, recruiting for the Canadian Navy had reached the stage where there was a surplus of personnel, many waiting to man new escort vessel construction not yet completed. Third, in contrast, the RN was experiencing a severe personnel shortage and had more ships than it could man. Fourth, and most important, the time was approaching when the Western allies would have to undertake a major cross-Channel invasion, an operation that would require not just hundreds but thousands of ships and smaller craft.

These factors became apparent at the Quadrant conference attended by the leaders of Britain, the United States, and Canada at Quebec City in September 1943. In meetings with Admiral Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord of the RN, and Vice-Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the head of combined operations, Vice-Admiral Percy Nelles, the Canadian chief of the naval staff, confessed his concern that the Canadian Navy “did not finish the war as a small ship navy entirely.”7 Far from that, he informed his British counterparts, his intention was to create a post-war fleet of five cruisers, two light fleet aircraft carriers, and three flotillas of fleet destroyers. Nelles asked for British assistance in achieving this ambitious objective and he got it. With the help of Britain’s Winston Churchill in some very adroit manoeuvring around Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who was ever suspicious of defence expenditures, Nelles came away with happy results. It was agreed that the RCN would take over and man two escort carriers, two light cruisers, two fleet destroyers, three flotillas of LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry), and also contribute a beach commando—an amphibious traffic control unit—for the forthcoming invasion.

HMCS Prince Robert, one of three Canadian National Steamship liners converted into armed merchant cruisers by the RCN as a stopgap in 1940, is pictured here, in a British drydock in January 1944, after later conversion as an anti-aircraft cruiser.

Other initiatives undertaken in 1943 and early 1944 increased the RCN’s presence in European waters. The three Prince ships, no longer required as auxiliary cruisers, were taken in hand throughout the year and rebuilt: Prince David and Prince Henry were converted into landing ships, each of which would carry a landing craft flotilla, while Prince Robert was rebuilt as an anti-aircraft defence ship. The strong Canadian presence in Coastal Forces led to a British proposal that the RCN man two MTB flotillas for the invasion and the first personnel were on their way overseas by October 1943. In early 1944, a British request for minesweepers was met by the dispatch of 16 Bangor-class vessels. In all, the Canadian contribution to Operation Neptune, the naval component of the planned Normandy landing, would be 126 vessels of all types and no less than 10,000 officers and seamen. Apart from the boost this would give the Allied cause, NSHQ firmly believed that participation in the most crucial operation of the war would enhance the RCN’s prestige and increase its profile among the Canadian people. Neptune would be the culmination of the wartime growth of Canada’s navy and it would involve the cream of that service.

In January 1944, much to the satisfaction of their ships’ companies, the four RCN Tribals were transferred from Scapa to Plymouth. Here they formed, along with RN Tribals, the 10th Destroyer Flotilla, which had the task of carrying out “Tunnel” operations to reduce the strength of major German surface units in the Channel. Commencing in late February, the 10th Flotilla patrolled at night, searching for enemy destroyers and torpedo boats (actually small destroyers) based in Le Havre and Cherbourg. This work continued through March and into April, without any contact, causing the crews to term the Tunnel patrols as “FAFC,” an acronym that can be rendered most tactfully as “Fooling Around the French Coast.” Things changed on the night of th 25 - 26 of April 1944 when Athabaskan, Haida, and Huron, along with British vessels, encountered three large German torpedo boats, T-24, T-27, and T-29, and began a gun and torpedo battle that evolved into a long chase as the enemy tried to escape. T-27 and T-24 got away—although the former was badly damaged by accurate Canadian gunnery—but T-29 was not as fortunate. The Canadian destroyers circled it at close range hitting it with every weapon they could bring to bear until it was scuttled by its crew, becoming the largest warship to be sunk by the RCN up to that time in the war.

Two nights later, guided by radar, Athabaskan and Haida again caught up with T-24 and T-27 and damaged the latter vessel so severely that its commanding officer ran it aground. Unfortunately, Athabaskan was hit by a torpedo fired by one of the German vessels causing a magazine to explode, igniting fuel oil that set it on fire and quickly sank it. The disaster unfolded very fast. Leading Seaman B.R. Burrows, manning the destroyer’s gunnery radar, ran out on the starboard side of the stricken vessel and later recalled:

I just got blown over the side. Instinct told me, “Get the hell out of here, fast!” so I swam as fast as I could. Diesel fuel is very volatile and I got showered with diesel fumes [oil]—they burnt me from stem to stern. I didn’t know it at the time—it hit me so fast that I just kept on swimming. Also, although I didn’t know it at the time, I was swimming through Bunker C fuel, the black sticky stuff used in the ship’s boilers to drive the main engines. I got covered in it.8

Most of the Athabaskan’s crew were able to get off the destroyer before it went down, but the explosions had destroyed almost all its boats and floats. DeWolf in Haida, seeing his comrades’ plight, brought his ship near the men swimming in the water and proceeded to pick up survivors, thus placing his own destroyer in peril. Seeing this, Lieutenant- Commander Stubbs, the captain of Athabaskan, in the water with his men, shouted “get away, Haida, get clear!”9 and DeWolf regretfully had to leave the scene after picking up only 42 men, although he left his own boats and floats for their succour. Of Athabaskan’s ship’s company of 261 officers and men, 128 did not survive its sinking, among them Lieutenant-Commander Stubbs. The loss of Athabaskan was not in vain—by the end of April 1944, as the Allies began the final preparations for the invasion, German destroyer strength in the Channel had been reduced to just five vessels.

By this time, the various Canadian naval units that would participate in Operation Neptune had begun to assemble in southern British ports. The 16 Bangor-class minesweepers arrived in April to commence training in sweeping, a new activity for their ships’ companies. They did not impress their British instructors, who commented on the Canadians’ nonchalant attitude that minesweeping was “child’s play.” That attitude was quickly knocked out of them during six weeks of intense work-ups lasting until late May when they were judged by the RN as being “efficient, keen and competent.”10 Eight of the Bangors formed the 31st RCN Minesweeping Flotilla under Commander A.G. Storrs, RCN, the remainder being divided up among British flotillas.

Crew of the V-class destroyer Algonquin sponging out their 4.7-inch (12-centimetre) gun after bombarding German shore defences in the Normandy beachhead.

The two Canadian MTB flotillas, and the landing ship and landing craft flotillas, had fewer problems as they possessed a nucleus of veteran officers and warrant officers who knew their business. Prince David, Prince Henry, and the 260th, 262nd, and 264th LCI(L) Flotillas participated in the major amphibious exercises held in April and May, although to its dismay Beach Commando W learned that it would not be part of the assault forces but would come ashore at a much later date. The 29th RCN MTB Flotilla under Lieutenant- Commander A.G. Law, RCNVR, manning 20-metre“Short” boats armed with a two-pounder (40 mm) gun and 18-inch torpedoes, and the 65th RCN MTB Flotilla under Lieutenant- Commander J.R.H. Kirkpatrick, RCNVR, manning the larger and more heavily-armed Fairmile D Type “Dog Boat” craft worked up at Holyhead throughout April and May. Law was horrified when the 29th Flotilla’s torpedo tubes were removed and replaced with small depth charges. “Mere words,” he later commented, “cannot explain the effect on the Flotilla’s morale: the bottom dropped out of everything, and our faces were long as we watched our main armament and striking power being taken away.”11 Law lobbied hard to get the torpedoes back but it would take two months before they returned.

In late May, two of the fleet destroyers acquired from the RN after the Quadrant discussions of the previous September, HMCS Algonquin and HMCS Sioux, arrived in Portsmouth. Although given Tribal names, the newcomers were from the more modern “V” class and, although somewhat smaller and less heavily armed (only four 4.7-inch guns as opposed to six 4.7-inch and two four-inFch guns in the Tribals), they were sturdy ships with longer range. After commissioning and work ups both destroyers had been sent to Scapa Flow in April where they served as screening vessels in two carrier air strikes against the Tirpitz. They acquitted themselves well but the ships’ companies were happy to be ordered south to provide shore bombardment for the Normandy landing. They did not have long to wait. At 1500 hours on 5 June 1944, Lieutenant-Commander D.W. Piers, RCN, Algonquin’s commanding officer, assembled his officers and men on the destroyer’s quarter-deck to inform them that the invasion would take place on the following day and that Algonquin had “been chosen to be in the spearhead.” As Leading Seaman K. Garrett remembered,

Everyone there gave a low moan about being in the spearhead of the invasion, but Debbie [Piers] had more to say, which stunned everyone there. He mentioned that also we had been chosen to be the point on the end of the spear. I said to my fellow shipmates, “A spear sometimes gets blunted.” Then the Captain had more to say. He said, “If our ship gets hit near the shore, we will run the ship right upon the shore and keep firing our guns, until the last shell is gone.”

I was scared no longer. With a spirit like this, we couldn’t lose. I felt right then and there, “We will succeed.”12

Three hours later, HMCS Algonquin sailed for France.

The armada assembled for Operation Neptune consisted of 6,900 vessels, ranging from battleships to merchant ships, including 63 Canadian warships, and no fewer than 4,100 landing ships or craft, of which 46 were manned by the RCN. The first Canadian sailors to see action in the operation were the 16 Bangor-class minesweepers, which had the crucial task of clearing corridors through the German defensive mine belt so that landing craft could reach the beaches. The 31st Flotilla commenced its work in the early evening of June 5, sweeping and marking a channel to the American landing site dubbed “Omaha Beach,” and completed it by dawn on June 6. As the sweepers turned out to sea, they could see hundreds of landing craft approaching the coast under the cover of a heavy shore bombardment carried out by battleships, cruisers, and destroyers to neutralize the German shore defences. Algonquin and Sioux participated in this bombardment. Their initial task was to fire at shore batteries located on the eastern side of Juno Beach and both destroyers commenced shooting shortly after 0700. Sioux engaged a shore battery for 40 minutes before ceasing fire as the first landing craft approached the beach. Lieutenant L.B. Jenson, RCN, the executive officer of Algonquin, recalled that the destroyer hoisted its White Ensign before opening fire at a shore battery near the village of Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer. Forty-five minutes later, when Algonquin checked fire, the “sea was getting a little choppy and the hundreds of landing craft going in looked rather uncomfortable.”

“So far,” Jenson remembered,

no shells or bombs had come our way and we had the privilege of a grandstand view of British and Canadian forces in this incomparable assault. Fires were burning on shore and some landing craft also appeared to be on fire, while soldiers were clambering out of other landing craft and moving ashore without noticeable opposition.13

The two destroyers stood off the coast until the assault troops had secured the beaches, after which they provided fire support on call from forward observation officers who landed with the infantry. At 1051 Algonquin destroyed two German self-propelled guns with its third salvo.

The Canadian LCI flotillas and the two LCA (Landing Craft, Assault) flotillas carried by Prince David and Prince Henry had a less happy time. The 529th Flotilla from Prince David transported troops of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division into Juno Beach, but a 10-minute delay in landing meant that a rising tide covered many of the beach obstacles and seven of the eight LCAs in this flotilla were lost either from mines or German fire. The 528th Flotilla operating from Prince Henry suffered not only from shore fire but also explosive charges attached to obstacles and lost one LCA when the craft hit a mine. The 260th LCI Flotilla encountered similar perils when its seven craft landed later in the morning, as well as a German aircraft, which dive-bombed LSI 285 without effect. All of this flotilla’s craft managed to get off the beach, but the 262nd LCI Flotilla was forced to leave five of its 12 craft on the beach after they suffered mine damage. The 10 LCIs of the 264th Flotilla transported British troops to Gold Beach and, as the captain of each craft was anxious to win the £10 in the flotilla pool for the LCI that touched on shore first, they “jammed” their craft “full- ahead” with the result that some hit the beach at such speed that they could not get off again.14 Otherwise this flotilla had a rather quiet time.

Neptune was a complete success and when darkness came on 6 June 1944 just over 150,000 Allied troops were in France—at a cost of 9,000 casualties, of which 1,081 were from the Canadian Army and Navy. Having got the initial wave ashore, the Allied navies’ task was to guard their vulnerable seaborne lines of communication. Toward this end, the 29th MTB Flotilla was the first Canadian naval unit to see action. On the night of June 6, Lieutenant-Commander Law and four of his boats engaged German fast attack craft attempting to lay mines on the eastern flank of the beachhead. A swift and hard-fought little action followed in which the 29th Flotilla, along with British MTBs, sank one of the German craft and damaged others. On the following two nights, Law’s boats encountered and engaged several small German destroyers prowling around the beachhead. Although seriously over- matched and cursing the fact that their torpedoes had been removed, the Canadian MTBs engaged the enemy vessels with their two-pounder guns and managed to scare them off before they did any serious damage.

The 29th Motor Torpedo Boat flotilla races across the Channel.

The Kriegsmarine, however, was just getting started. On the night of the 8 - 9 of June, a powerful German surface force consisting of three destroyers (Zh-1, Z-24, Z-32) and a torpedo boat (T-24) attempted to attack shipping in the western side of the beachhead. Fortunately, the German movement was betrayed by signals intelligence, which permitted the 10th Destroyer Flotilla of eight vessels, including the Haida and Huron, to make an interception. Contact was made in the early hours of June 9 and a ferocious night-time engagement with guns and torpedoes ensued. Dodging a German torpedo attack, Haida, Huron, and their British consorts opened fire with their main armament, inflicting serious damage on the enemy. In just over an hour, ZH-1 was sunk and the three surviving German warships broke off contact and made for Brest, unwittingly steaming through a minefield, which hampered pursuit. Regaining contact with Z-32, Haida and Huron fired at the hapless destroyer, which had become separated from the other two enemy ships, with accurate radar-controlled gun fire until its captain deliberately ran it aground. This highly successful action, which saw the Canadian Tribals achieve the destruction of their third large German warship in two months, completely fulfilled NSHQ’s hopes that RCN surface warships would garner positive publicity.

Throughout the summer of 1944, Canadian ships continued to watch the seaward flank, as the Allied armies gradually expanded their bridgehead. The two MTB flotillas saw the most consistent action. Lieutenant-Commander Kirkpatrick’s 65th Flotilla arrived in Normandy on 11 June to operate on the western side of the beachhead, and for the next two weeks the flotilla’s Fairmile “Dog boats” fought a number of actions against German coastal convoys, sinking several small escort vessels. Perhaps the high point came on the night of the 3 - 4 of July when Kirkpatrick took his command into the port of Saint-Malo and shot up two German patrol boats before withdrawing unscathed under heavy fire. Thereafter things settled down on the western flank and the 65th Flotilla enjoyed a relatively quiet summer until it was withdrawn to Britain in early September.

Matters were more hectic on the eastern side. The 29th Flotilla rejoiced when it was re-armed with torpedoes in mid-June as they now had an effective weapon against the German “Night Train” operations that saw enemy surface ships, including destroyers, torpedo boats, E-boats, and small minesweepers attempting to break into the beachhead area. During the latter part of June and well into July, the 29th Flotilla fought several nighttime actions including a particularly dangerous one against nine German E-boats attempting to sortie from Le Havre on the night of the 4 - 5 July that encountered three of Law’s MTBs off Cap D’Antifer. As he remembered:

Simpson, the radar operator, soon picked up echoes at 2,000 yards dead ahead, and Footsie signalled the frigate that we had picked up the enemy. Sure enough, nine E-Boats, hugging the coast, were moving toward our position, and I grimly imagined their surprise when they found the opposition so well established in their hideaway.

459 moved off, steadily increasing speed, followed closely astern by Bobby and Bish. The enemy were now 1,500 yards from us, and both sides were closing dead ahead. It was exactly at midnight when our three boats opened fire at 1,400 yards, and at 1,200 yards all guns were blazing away at the leading E-Boat. We then switched targets to the third E-Boat in line, and under our concentrated volley it burst into flames and was left in a sinking condition. His comrades quickly made smoke, obscuring our view, but we could still see the glow of the fire through the haze, and I very much doubt if the craft could have made Le Havre.15

Darkness hours were often livened by attacks from the Luftwaffe, which rarely managed to hit anything but interfered with everyone’s sleep. Some of these aircraft, however, dropped “Oyster” pressure mines, which were virtually unsweepable. HMCS Algonquin, which, along with Sioux, had continued to engage shore targets at the request of the army in the weeks following D-Day, had a close call on June 24 when it came to anchor off the beachhead. Lieutenant L.B. Jenson, RCN, officer of the watch, spotted a floating mine and was granted permission to sink it with gunfire. As he recalled:

I decided to do it personally, using my Sten gun. Looking back, we were a bit too close and this was an unusually stupid thing to do. I did not stop to reflect that mines can blow up and shower you with shrapnel. God was with me. The mine with all its horns intact quietly sank.

[The British destroyer, HMS] Swift snootily signalled us, “While you play around, may I anchor in your billet and you anchor in mine?” I signalled, “Yes, please,” and she steamed ahead to what had been our spot. I watched in my binoculars as she let go her anchor and was immediately enveloped in a cloud of white spray. There was a second explosion, her back was broken and she started to sink.16

Fifty-seven British sailors died in this incident, but that did not stop the hard-bitten “Algonquins” from sending boats over to the wreck to salvage useful items of equipment, including a quantity of rum stored in the petty officers’ mess. Shortly thereafter, their bombardment tasks completed, the two “V”-class destroyers withdrew to Britain.

The cross-Channel invasion having been accomplished, the RCN’s participation in combined operations began to wind down. The three LCI flotillas were paid off in July just as Beach Commando W landed in Normandy where it remained for two months handling waterborne and vehicle traffic on Juno Beach before it too was paid off. Prince David and Prince Henry, with their attached LCA flotillas, left Normandy in late July and headed for the Mediterranean where they formed part of the Allied naval force assembled for Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France. This was successfully carried out on August 16 and the two ships were then employed in the eastern Mediterranean, ferrying troops and supplies to Allied forces operating in Yugoslavia and Greece until the end of the year.

The Canadian Tribals with the 10th Flotilla continued to be active in the Normandy area throughout the summer. On the 27 - 28 of June, Huron sank a heavily-armed German minesweeper and several patrol boats with gunfire before leaving for Canada for a refit. In the late summer Iroquois and Haida began to carry out offensive sweeps in the Bay of Biscay to clear out German coastal traffic. On the night of the 5 - 6 of August, the two destroyers engaged an enemy convoy of eight ships south of Saint-Nazaire, sinking two escorting minesweepers before starting to shell the remaining vessels. Haida had just started on this work when a round prematurely detonated in a gun of its “Y” turret, killing and wounding several members of the gun crew. Able Seaman M.R. Kerwin, though blinded and dazed by the explosion and wounded by splinters, went into the blazing turret and succeeded in dragging a gun crew member to safety, which brought him the award of a Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. This accident forced Haida to withdraw for repairs leaving Iroquois as Canada’s representative in the Biscay.

In the early hours of August 16, Iroquois, in company with the cruiser HMS Mauritius and the destroyer HMS Ursa, encountered a large convoy near the mouth of the Gironde River. The enemy escort, consisting of the old adversary, T-24, an aircraft tender, and several minesweepers, put up a stiff fight. After dodging torpedoes launched by T-24, Iroquois responded with a torpedo attack of its own, but Force 27 had to withdraw to seaward after coming under fire from heavy German coast batteries. It later returned, and Ursa and Iroquois between them sank or drove aground three minesweepers and two other vessels. The enigmatic T-24 escaped but was later sunk by British and Canadian aircraft. The commanding officers of both Mauritius and Ursa had high praise for Iroquois’ gunnery, the captain of Ursa reporting that the action reflected the greatest credit on its commanding officer, Commander James Hibbard, RCN. Iroquois remained with Force 27 until early September when it was withdrawn, as by this time German naval forces in France had nearly ceased to exist, either sunk at sea or destroyed in port by air bombardment.

The 16 Canadian minesweepers continued with their undramatic but important work in the Channel. It was not until early 1945 that they were returned to escort duties, but the end of the war saw them return to minesweeping when an international effort was made to clear European waters of the deadly items. The Canadian Bangors only ceased this task in September 1945, but mine clearance continued for many years after the shooting had ended.

After the Allied armies broke out of Normandy in mid-August to liberate Paris and the Low Countries, Canadian naval units continued to protect their seaward flank. Throughout the autumn, the 29th and 65th MTB Flotillas, based in southeast England, interdicted E-boat raids and harassed German coastal traffic. For the Canadian MTBs, the high point of this period was the amphibious landing on Walcheren Island in the Scheldt Estuary, which was carried out in early November. Shortly thereafter Lieutenant-Commander Law’s 29th Flotilla had the misfortune to run into the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” a force of four German flak trawlers armed with deadly 88 mm guns that enjoyed legendary status in Coastal Forces. As Law recalled,

Although I had not come in contact with these uncouth gentlemen since 1943 when I had been working off the Dutch coast, I knew that these bullies were far from gentle….We spent the remainder of the night playing a game with each other which consisted mainly of batting shells back and forth. No one was getting hurt, but it was a frighteningly dangerous game. As soon as we had manoeuvred into a possible torpedo position and were ready to pull the lever, what would happen?

The Four Horsemen would alter course toward us, and just to keep the game lively they would slam out a few more 88 mms…. .The game went on; and at the end of the period there was still no score.17

In December, the 29th Flotilla was glad when it was transferred to the liberated port of Ostend as it meant less transit time in the Channel. On Valentine’s Day 1945, however, Law’s command met an untimely end when an accident in the crowded harbour led to the destruction by fire of 12 MTBs and the deaths of 64 officers and sailors, including 29 Canadians. As only four, very worn, Canadian MTBs survived the disaster, it was decided to disband the 29th Flotilla. It was replaced at Ostend by the 65th Flotilla, which served there until the end of the war.

The two Canadian “V”-class destroyers, meanwhile, returned to northern waters. To reduce the German naval threat to the Murmansk convoys, a series of operations were undertaken to sink the remaining German capital ships based in Norway. Algonquin and Sioux joined a Home Fleet destroyer flotilla based at unlovable Scapa Flow and participated in Operation Mascot on July 17, screening carriers that flew off aircraft in an unsuccessful attempt to sink the dreaded Tirpitz. Subsequent strikes on the German battleship proved no more profitable, and it remained a threat until November when Royal Air Force (RAF) Lancaster bombers destroyed it with 5,450 kilogram “

The safe return to Scapa Flow of the Canadian-operated aircraft carrier HMS Nabob, after being torpedoed by a U-boat on 22 August 1944, was an amazing feat of seamanship.

Before that, in August, Algonquin and Sioux were joined by HMS Nabob, the Canadian- manned escort carrier. Carrying 13 Grumman Avenger torpedo-bombers and eight Wildcat fighters, Nabob saw its first action in Operation Offspring, an aerial minelaying operation in Norwegian coastal waters on August 9 and performed well. Then came Operation Good- wood, a planned air attack on the Tirpitz carried out by the fleet carriers, HM Ships Formidable, Furious, and Indefatigable, combined with a minelaying strike by Nabob and another escort carrier in the waters of the Altenfjord, the German battleship’s lair. Bad weather hampered Goodwood and most of the air strikes and minelaying attacks were cancelled. Unfortunately for Nabob, late in the afternoon of August 22 it was hit by torpedo fired by a U-boat that blasted a hole that measured 10 by 15 metres in its starboard side. As his ship began to settle by the stern, the commanding officer, Captain H.N. Lay, RCN, commenced damage control efforts and evacuated all non-essential personnel to waiting destroyers, including Algonquin. Within four hours, however, the flooding was brought under control and Nabob was able to raise steam and get under way, although down by the stern. Over the next five days, the wounded carrier slowly limped the 1,600 kilometres to safety at Scapa, even flying two Avengers off its sloping flight deck to harass a U-boat that was trailing it. For Nabob’s largely Canadian crew it was an impressive piece of seamanship, but the vessel’s fighting days were over—its company was paid off and the carrier was cannibalized for spare parts.

In September and October, Algonquin and Sioux resumed escort duty on the Murmansk Run. It was, as one officer recalled, a return to the “most hazardous and horrible place for naval operations” to take place, which had to be carried out in the face of not only pack ice, ferocious storms, “perpetual night in winter, perpetual day in summer,” but also German submarines and aircraft.18 In November, Algonquin got some relief from this onerous duty when it participated in Operation Counterblast, an attempt to interrupt enemy coastal traffic, transporting vital iron ore from Norway to Germany. In company with British cruisers and destroyers, Algonquin intercepted a large convoy off Stavanger on the 12th of November and, as its commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander D.W. Piers, RCN, reported:

Many targets were plainly visible and quickly engaged. ALGONQUIN opened fire on an escort vessel at an initial range of 5400 [yards or 4937 metres] at 2314 and obtained a hit with the first salvo. This target was also being engaged by other ships ahead; it burst into flames within a minute. Fire was shifted at 2317 to a merchant ship at an initial range of 8000 yards [7315 metres]. Using No. 2 gun (B) for starshell illumination and the remainder of the armament firing S.A.P [Semi-Armour-Piercing round] this second target was also reduced to flames by the first few salvoes.19

The result of Counterblast was that two of four German merchant ships and five of the six escorts were sunk. Unfortunately, however, similar operations carried out over the winter garnered minimal results.

When Algonquin left for refit in Canada in January 1945, Sioux continued serving on with the Murmansk Run. If anything, things got worse when the Luftwaffe deployed a large force of torpedo bombers to northern Norway—air attacks now became frequent and, inevitably, losses became heavier. On February 10, Sioux was with Convoy JW-64 outward bound to Murmansk when it came under heavy air attack. As its commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander E. Boak, RCN, reported, the Luftwaffe pressed its attacks home:

a JU 188 appeared from a bearing of Green 90 …, about 50 feet off the water and 3000 yards [2743 metres] away, flying directly towards the ship. At about 1500 yards [1371 metres] the plane dropped a torpedo and banked away to starboard, flying-up between HMCS SIOUX and HMS LARK.... [My] Ship went “Full ahead together, hard-a-port,” and steadied up on a course 060, Starboard [20 mm] Oerlikons opened up on the plane just before the torpedo was dropped and followed him out of range, and also one round from “B” gun was fired at him but was short. Enemy’s port engine was seen to be smoking heavily before he disappeared into a snow flurry.20

The return convoy, RA-64, encountered terrible weather. One of Sioux’s officers recalled that “abused engines broke down, cargoes shifted, decks split, steering gear went wonky, ice- chipped propellers thrashed,” while the seas “continued at awful heights, spindrift streaming from boiling crests.”21 The weather did not stop the Germans: not only was RA-64 attacked by torpedo bombers but also by a large force of U-boats that managed to sink two of the escorts while losing one of their own. On the 19th of February, the Luftwaffe appeared overhead and, at one point:

One of the planes closed to torpedo [merchant ship] number 103. Fire was opened and aircraft released torpedo which eventually exploded at end of run between 9th and 10th columns [of merchant ships].The plane went down the port side being heavily engaged with close range weapons. At the same time a plane coming in from the starboard quarter was also engaged and driven away.22

Throughout these two convoys, Sioux was almost in constant action and the efforts of its commanding officer and ship’s company were marked by the award of a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) to Lieutenant-Commander Boak. Shortly thereafter it departed for Canada for a well-deserved and needed refit.

Sioux was replaced by Haida, Huron, and Iroquois, returning from their own refits, as well as the second Canadian-manned escort carrier, HMS Puncher. This ship enjoyed better luck than Nabob and participated in four operations in February, March, and April against Norwegian targets, flying off its Wildcat fighters to provide air cover for shipping strikes and minelaying operations, before withdrawing for boiler cleaning. During these last few months of the war—although Iroquois participated in one coastal convoy attack, sinking a tanker—the major activity for the Tribals was the seemingly interminable Arctic convoys and perhaps no sailors in the RCN were happier when the surrender of Germany in May 1945 brought an end to the war in Europe and relieved them of this burdensome task.

One enemy remained. From 1943 onward, when it became clear that the Battle of the Atlantic and the war in Europe were moving toward a favourable conclusion, NSHQ had turned its attention to planning for the Pacific. The intent was to demonstrate that the RCN was more than an ASW escort force and affirm the objective NSHQ had doggedly pursued since 1939—to make a major contribution in terms of surface ships to act as the foundation for the balanced blue water post-war fleet. The Navy’s ambitious plans were thwarted only in part by Mackenzie King, who not only kept a careful eye on costs but was ever suspicious of getting Canada entangled in British colonial problems. After much discussion and a considerable amount of political manoeuvring between the government, NSHQ and the RN, it was ultimately agreed that the RCN would man two light fleet carriers with four Canadian air squadrons on board, two light cruisers, four Tribal-class destroyers, two “V”-class destroyers, eight new Crescent-class destroyers, the anti-aircraft ship Prince Robert, and no less than 44 anti-submarine warfare (ASW) vessels. In terms of personnel, this commitment would total about 37,000 officers and seamen, serving both afloat and ashore—nearly half the RCN’s strength in late 1944.

The RCN took greatest pride in the two light cruisers provided to Canada by Britain as a free gift. Armed with nine six-inch guns, eight four-inch high angle guns and many smaller 20 and 40 mm guns, these ships were intended to bolster the anti-aircraft defences of the British Pacific Fleet in which they would serve. HMCS Uganda, the first cruiser to enter service, was commissioned in Charleston, South Carolina, on Trafalgar Day (21 October) 1944. An impressive array of American, British, and Canadian dignitaries and senior officers attended the ceremony and the British ambassador reported that Canadian naval officers were “all labouring happily under a feeling of excitement and anticipation caused by the acquisition of what they called in their official leaflet ‘the first Canadian cruiser….’ It was as though,” he continued, “the Canadian Navy was reaching manhood and that, through its Navy, Canada herself was stepping forward and upward.”23 In early February 1945, following work ups, Uganda sailed for the Pacific, while the second cruiser, HMCS Ontario, commissioned in April and immediately sailed to join it.

In May Uganda participated in the shore bombardment of the Sakashima Islands, part of the invasion of Okinawa, but its normal role with the British Pacific Fleet was to act as an anti- aircraft guard, a duty it performed in June and July during a number of airstrikes on the Japanese home islands. In July, however, Uganda’s war and NSHQ’s plans for a major Pacific force came to a somewhat ignominious end, because of the federal government’s policy that only volunteers would serve in the Pacific and that all service personnel who volunteered would receive 30 days clear leave in Canada before being sent to that theatre. This meant that, if Uganda’s ship’s company did not volunteer en masse, the ship would have to return to Canada to re-commission with an all-volunteer crew. On 28 July 1945 the vote was held in Uganda and 80 percent of its officers and seamen opted not to volunteer. This being the case, Uganda departed for Esquimalt and arrived there shortly before the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to the Pacific conflict. Consequently, no Canadian warship was present in Tokyo Bay when representatives of the Japanese government unconditionally surrendered to the allied powers on board the American battleship USS Missouri.

The Canadian Navy’s role in surface warfare during the Second World War has been overshadowed by its major contribution to victory in the Battle of the Atlantic. During the long years of that seemingly interminable struggle, however, the RCN achieved an outstanding record of success in conventional naval operations in Europe and the Pacific, operations that would prove a very useful foundation for the post-war service.

Author: Donald E. Graves

1 C.A. Law, White Plumes Astern (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing Ltd., 1989), 11.

2 Quoted in W.A.B. Douglas, Roger Sarty, Michael Whitby, A Blue Water Navy (St. Catharines, ON: Vanwell Publishing, 2007), 111.

3 LAC, RG 24,Vol. 6797, Captain H.G. De Wolfe, “Employment of Tribal Destroyers,” 7 December 1942.

4 United Kingdom National Archives [UKNA], ADM 199/1406, Report of Proceedings, HMCS Athabaskan, 30 August 1943.

5 DHH, BIOG file, Address by Rear-Admiral P.D. Budge, 19 September 1981.

6 R.D. Butcher, I Remember Haida (Hantsport, NS: Lancelot Press, 1985), 36-37.

7 UKNA, ADM 205/31, Minutes of Meeting, Quebec, 11 August 1943.

8 P.R. Burrows, “Prisoners of War,” Salty Dips, Vol. 3 (Ottawa: Naval Officers’ Association of Canada, 1988), 171.

9 Len Burrow and Emile Beaudoin, Unlucky Lady: The Life and Death of HMCS Athabaskan (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982), 125.

10 DHH, Commander, Fleet Minesweeping Office, Devonport, to Captain, Minesweeping Command, 22 April 1944.

11 Law, White Plumes Astern, 37.

12 Quoted in L.B. Jenson, Tin Hats, Oilskins and Seaboots (Toronto: Robin Brass Studio, 2000), 222.

13 Jenson, 226.

14 J.M. Ruttan,“Race to Shore,” Salty Dips, Vol. 1 (Ottawa, 1985), 193.

15 Law, 104.

16 Jenson, 233.

17 Law, 148.

18 Jenson, 213.

19 LAC, RG 24, DDE 224, Report of Proceedings, HMCS Algonquin, 13 November 1944.

20 LAC, RG 24, DDE 225, Narrative of Air Attack, HMCS Sioux, 10 February 1945.

21 Hal Lawrence, A Bloody War (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1979), 168-69.

22 LAC, RG 24, DDE 225, Report of Air Attack, HMCS Sioux, 20 February 1945.

23 UKNA, ADM 1/18371, Sir Gerald Campbell to Director of Operations, 30 October 1944.