Trial Fairness and Cross-examination

CONTENT WARNING: This chapter includes traumatic content

“It was a hell I will never forget or forgive. The system set me up for horror. This kind of treatment on the stand is in itself a crime but not one I can report or get any apology for.” [1]

ISSUES

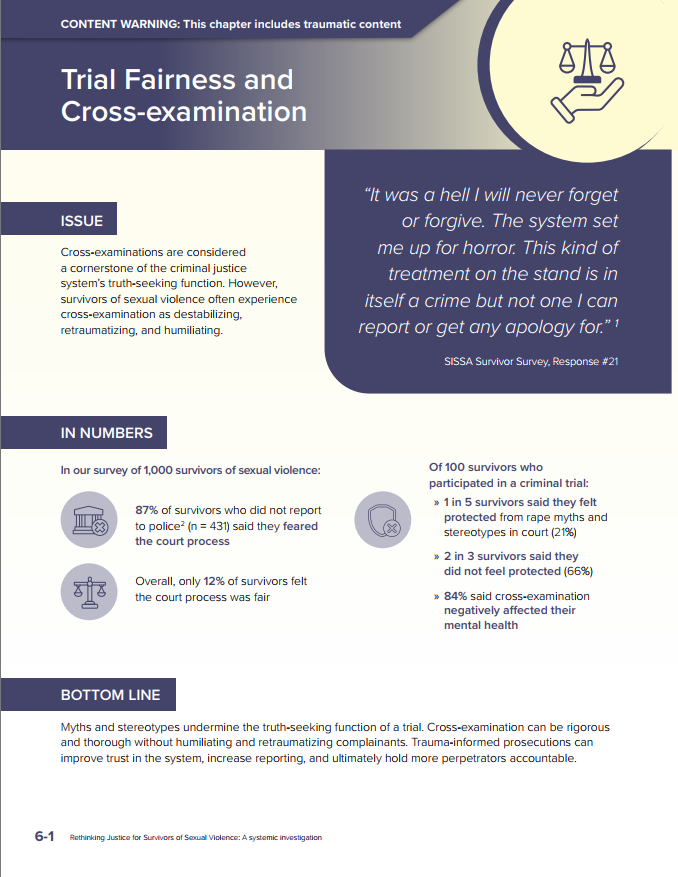

Cross-examinations are considered a cornerstone of the criminal justice system’s truth-seeking function. However, survivors of sexual violence often experience cross-examination as destabilizing, retraumatizing, and humiliating.

IN NUMBERS

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- 87% of survivors[2] who did not report to police (n = 431) said they feared the court process

- Overall, only 12% of survivors felt the court process was fair

Of 100 survivors whose cases went to trial:

- 1 in 5 survivors said they felt protected from rape myths and stereotypes in court (21%)

- 2 in 3 survivors said they did not feel protected (66%)

- 84% said cross-examination negatively affected their mental health

KEY IDEAS

- Despite important changes to the Criminal Code, some cross-examinations still rely on myths and stereotypes

- Certain methods of cross-examination can be dehumanizing

- Survivors with intellectual disabilities or neurodivergence may face cross examinations that don’t take into account their communication needs

- Cross-examination is traumatic for child survivors – especially when they have to testify twice

BOTTOM LINE

Myths and stereotypes undermine the truth-seeking function of a trial. Cross-examination can be rigorous and thorough without humiliating and retraumatizing complainants. Trauma-informed prosecutions can improve trust in the system, increase reporting, and ultimately hold more perpetrators accountable.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Preliminary Inquiries

4.1 Eliminate preliminary inquiries: The federal government should amend the Criminal Code to remove preliminary inquiries for all sexual offences, protecting children and vulnerable complainants from the harm of multiple cross-examinations.

Cross-Examinations

4.2 Review trial procedures to enhance trauma-informed and culturally safe practice: The federal government should review the Criminal Code to increase trauma-informed practice for all trials. Trauma-informed practice should include accessibility for people with disabilities and culturally safe, Indigenous specific supports, such as dedicated Indigenous survivor advocates.

4.3 Develop a national justice strategy to protect children and youth: The federal government should consider a coordinated national strategy to uphold the dignity and safety of all children and youth who have experienced sexual violence. This strategy could include national standardization of forensic interview protocols, mandatory training for interviewers, national training standards, and universal access to child and youth advocacy centres.

Our investigation

Background

In the groundbreaking 1993 judgment in R v. Osolin,[3] Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) Justice Cory wrote, “a complainant should not be unduly harassed and pilloried to the extent of becoming a victim of an insensitive judicial system.” [4]

- Thirty years later, complainants have shared that they are still being harassed, bullied, and retraumatized while on the stand.

As Justice Sopinka wrote in R v. Stinchcombe, “the right to make full answer and defence is one of the pillars of criminal justice on which we heavily depend to ensure that the innocent are not convicted.” [5] However, while a criminal trial must be fair to the accused, a trial that is fair only to the accused is not a fair trial.[6]

“If one set out intentionally to design a system for provoking symptoms of traumatic stress, it might look very much like a court of law.” [7]

What we heard

Survivors shared with us that:

- Cross-examination was very traumatic. It was catastrophic to their mental health and overall wellness,[8] causing panic attacks for months to follow[9]

- Cross-examination was humiliating; defence lawyers have “fun” destroying the survivor[10]

- Cross-examination caused them to be very angry[11]

- Cross-examination caused them to never report sexual violence again[12]

- Cross-examination led the survivor to believe that the criminal justice system is fundamentally flawed as a vehicle for justice for sexual assault survivors[13]

Public confidence in the justice system:

“I was too terrified of reporting because I didn’t want to have to go to court and be cross-examined.” [14]

One of the most concerning indicators of how survivors are treated in the criminal justice system, comes from the people working in the system. Stakeholders told us that police often warn survivors that reporting is not worth the pain and suffering it will cause. One judge told us that if their child experienced sexual violence, they would not suggest engaging with the criminal justice system.[15] In our survivor survey, 28% of survivors who went to police to report sexual violence were discouraged from making an official report (n = 499).

- Fear of the court process continues to grow. Of 431 survivors who chose not to report sexual violence to the police, 87% said that one of the reasons they did not report was because they feared the court process.

- 96% of survivors who experienced sexual violence in 2020 or later and did not report to police said fear of the court process was one of the reasons for their decision.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

“Cross-examination is a very traumatic experience. The sexual assault itself is already a horrific event to endure, but to have an aggressive cold-hearted defense lawyer pressure you into doubting your experience publicly in court to the judge, to your friends and supporters, to the press was catastrophic for my mental health and overall wellness. The court system did little if nothing to support us as victims. The judge and defense lawyer felt like forensic bean counters dissecting every shred of evidence, not displaying any care or empathy that there's a living human being who's been gravely hurt here. The defendant assaulted several women and yet the court process seemed to be designed to protect the defendant more so than the victims.” [16]

“I was never told that the defence lawyer … could laugh at me on stand and yell at me numerous times. I was never told that it would be acceptable for the accused to not only get up there and lie, but to call me fat and call me names and allow that to continue. I was never told that – after having the trial delayed so many times – they would be able to keep me on stand for three days, cross-examining me.” [17]

Cross-examination is sometimes premised upon myths and stereotypes

“The cross-examination was awful. I was surprised because they aren’t supposed to question based on myths and stereotypes. The judge didn’t stop that line of questioning.” [18]

“My assault took place when I was 6 or 7, and I was asked in court, “what were you wearing at the time of the assault?” Questions like this have a negative insinuation.

They are irrelevant and shaming to the victim.” [19]

The SCC has repeatedly held that “myths and stereotypes have no place in a rational and just system of law, as they jeopardize the courts’ truth-finding function.” [20] In R v. Kruk[21] the Supreme Court provides an overview of rape myths and stereotypes that used to be used to discredit complainants. Those myths and stereotypes perpetuated the view that women were less worthy of belief and did not deserve legal protection against sexual violence. Reliance on them is now an error in law.

Some of these myths include:[22]

- Genuine sexual assaults are perpetrated by strangers

- False allegations of sexual assault based on ulterior motives are more common than false allegations of other offences

- Victims of sexual assault will have visible physical injuries

- A complainant who said “no” did not necessarily mean “no”

- If a complainant remained passive or failed to resist the accused’s advances, either physically or verbally by saying “no,” she must have consented

- A sexually active woman is more likely to have consented to the sexual activity that formed the subject matter of the charge, and is less worthy of belief – otherwise known as the “twin myths”

The twin myths are set out in section 276(1) of the Criminal Code and apply to any part of a proceeding during the prosecution of a sexual offence.

These myths and stereotypes shifted the inquiry away from the alleged conduct of the accused and toward the perceived moral worth of the complainant.

- Negative social attitudes about women were often used to differentiate “real” rape victims from women suspected of concocting false allegations out of self-interest or revenge.

- Prejudicial beliefs about women who were Indigenous, Black, racialized, persons with disabilities, or part of the 2SLGBTQI+ community also influence societal expectations and rules about sexual assault victims.[23]

“Myths and stereotypes have taken deep root into our societal beliefs about what sexual assault is, and how a true victim of sexual assault should behave. The justice system is not immune to these myths and stereotypes. In fact, there are several well-publicized examples where myths and stereotypes have been employed knowingly or unintentionally throughout the criminal process.” [24]

Even though reliance on myths and stereotypes is now an error in law, the ability to distinguish them from legitimate lines of reasoning continues to be a challenge in sexual assault trials.[25]

- One legal scholar noticed a pattern that while more judges are trained on sexual assault, more jury trials are being elected by the accused. She thinks it is because defence believes it may be easier to get away with invoking myths and stereotypes with a jury comprised of lay people with no sexual assault training.[26]

- One survivor we interviewed explained how grateful she was that the judge interjected each time the defence relied on myths and stereotypes in their questioning.[27] Other survivors asked why the trial judge or Crown did not stop that line of questioning.[28]

- One person involved in training judges told us that some judges won’t intervene to avoid an appeal based on an allegation of bias toward the victim.[29]

“As has frequently been noted, speculative myths, stereotypes, and generalized assumptions about sexual assault victims and classes of records have too often in the past hindered the search for truth and imposed harsh and irrelevant burdens on complainants in prosecutions of sexual offences.” [30]

During the criminal trial of five hockey players accused of sexual assault, defence lawyers cross-examined the complainant on her text communication with her best friend that occurred the day after the assault.

Defence counsel suggested during cross-examination if she had been sexually assaulted, she would have told her best friend. This “suggestion” explicitly invokes the myth that it is common sense for a victim of sexual assault to tell people right away. The Crown objected, stating that that line of questioning relies entirely on myth-based reasoning.

However, the defence justified their questions to the Court by stating that they were part of the context to understand her actions the next day. The judge allowed it.

OFOVC Observation of R v. McLeod 2025 ONSC 4319

While a judge may be able to parse out myth-based reasoning from their analysis, a jury may be more easily influenced by the underlying insinuation of the myth and not understand that it is actually a normal trauma response to not speak out and tell people about a sexual assault.

- We know that survivors of sexual assault can experience confusion, trauma, shame, self-doubt, and may not tell anyone what happened, sometimes for years[31]

- Even if a jury is instructed to not rely on myth-based reasoning, the insinuation can easily lead to a question mark in the minds of judges and jurors and raise a doubt about how a “true” survivor would have behaved

“Juries are laypeople who lack training in interpreting the law and are susceptible to the practised theatrical performance of a defence lawyer. The Crown on the other hand, practices a more respectable form of law, where she doesn't use erroneous myths and stereotype or attack character; she merely applies the law to the situation. In the dramatized theatrics of a courtroom, the actual truth is muddled, and juries are making a decision based on a TV-drama caricature, not actual facts as they were documented verbatim in the written police statement and interview.” [32]

Case Study: Sexual Assault Court Watch

As a part of a three-year project to evaluate criminal legal responses to sexual violence in Canada, WomenatthecentrE attended 13 sexual assault trials in Toronto to analyze the administration of justice in the prosecution of sexual offences.

Court watchers noted the use of rape myths and stereotyping of complainants, which they attributed most frequently to judges and defence counsel. They applied a critical anti-oppression lens, including critical race, critical feminism, and critical queer approaches to better understand power imbalances in the courtroom based on gender, race, sex, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, ability, class, and citizenship.

They noted how the administration of hearings wreaks havoc on survivors, who were often not notified about changes and may have travelled long distances to attend court, only to be told the case would not proceed and they would have to prepare and travel again another day. When justice staff, accused, or complainants did not show up or were unprepared for trial, new hearings would be scheduled months later.

“We also want to acknowledge the few exemplary justice players who tirelessly called out rape myths and stereotypes, refusing to stand by while complainants were berated and badgered on and off the stand. By the same token, we completely denounce the outrageous and disappointing ways the legal system itself and many within it, continue to treat survivors of sexual violence.”

WomenatthecentrE found that external evidence (third party, expert, academic evidence) introduced by the Crown made a significant difference on the outcome of the case, although evidence remains subject to cross-examination and may still be used against the complainant. Cases that did not present evidence beyond the complainant’s testimony were frequently characterized by defence as, “he said–she said.” [33] They also noted that sexual violence complainants are reduced to “witnesses” in the justice system, but their testimonies are treated with a higher degree of suspicion and disbelief than other witnesses or victims of crime.[34]

Survivor survey:

Despite efforts to reduce the prevalence of rape myths and stereotypes in court, survivors told us that they felt unprotected. Of 100 survivors who participated in a criminal trial:

- 1 in 5 survivors said they felt protected from rape myths and stereotypes in court (21%)

- 2 in 3 survivors said they did not feel protected (66%)

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Protection is part of a fair process. Of 66 survivors who did not feel protected from rape myths and stereotypes during cross-examination, only 4 felt like the court process was fair (6%). Overall, only 12% of survivors felt that the court process was fair. 84% said cross-examination negatively affected their mental health and only 12% felt like cross-examination raised relevant facts about their case.

Some methods of cross-examination are dehumanizing

“Victims should not be required to park their dignity at the courtroom door.” [35]

“The most harmful aspect of the process was being cross-examined...

It was demeaning and belittling.” [36]

“Cross-examination was severely traumatizing and humiliating. He made up things and tried to convince the jury of flat out lies. He tried to take any detail he could and make me look as horrible as possible. It was beyond emotional abuse. I was unable to do any public speaking afterwards until I rehabilitated myself from the trauma. The lawyer was worse than the criminal. I'm sure the criminal enjoyed watching me be humiliated and created half of the insults himself. It was an extension of the horrors I experienced and should not be allowed.” [37]

Cross-examination is a key element of the right to make a full answer and defence,[38] however, “the right to cross-examine is not unlimited.” [39]

- Defence counsel must have a good faith basis for putting forth their questions.[40]

- Trial fairness does not guarantee the accused the best process without considering any other factors. A fair trial also must consider broader societal concerns.[41]

- “The right to a fair trial does not guarantee, the most advantageous trial possible from the accused’s perspective.” [42]

The goal of the court process is truth-seeking and, to that end, the evidence of all those involved in judicial proceedings must be given in a way that is most favourable to eliciting the truth.

Madame Justice L’Heureux-Dubé in R v. Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC).

Sexual violence is inherently and intentionally traumatizing. It is a crime of power and domination. If survivors must answer difficult questions and relive their experiences to hold perpetrators accountable, they must be provided a fair chance to do so. A fair chance means that the Crown, the defence, and judges must understand the impact of trauma and how it can affect a complainant’s testimony.

- People who have experienced trauma have more difficulty remembering some types of details, such as dates and times.[43]

- Trauma survivors are at a further disadvantage in court because they often have difficulty telling their stories in a coherent manner, especially under hostile questioning.[44]

- Research has shown that there are types of questions that are better suited to trigger a memory.[45]

Fear of Cross-examination

One of the main reasons women give for not reporting sexual violence is fear of the criminal justice process.[46] We learned:

- Some survivors told us that cross-examination felt like an intentional infliction of mental anguish

- Some described it as state facilitated sexual harassment[47] or a second rape[48]

- Cross-examination feels abusive to many survivors because they do not have the right to refuse to be cross-examined[49]

- Advocates believe that cross-examination is often used to get the complainants off balance, humiliate them, and pressure them to give up

“We now know why sexual assault victims are reluctant to proceed with criminal charges. Protected by the presumption of innocence, defendants do not have to testify while the complainant gets mercilessly grilled by defence lawyers in cross-examinations.” [50]

Some examples of cross-examination were so egregious they seem akin to cruel and unusual treatment.[51] In those cases, defence appears to be trying to shame and intimidate the victim, in front of the accused and everyone else in court.[52]

- Some survivors feel that the defence seems to enjoy mercilessly humiliating them and confusing them while they are publicly reliving their trauma. The defence counsel appear to believe that a torturous cross-examination will advantage their client by discrediting the complainant or making the complainant quit.[53]

Humiliation as a deliberate tactic

A survivor of intimate partner sexual violence and coercive control was subjected to a prolonged and invasive cross-examination in which the Court permitted the display of multiple hours of graphic video footage, recorded without her knowledge, on a large screen over several days. This footage formed part of the charges of sexual assault and voyeurism.

The Court allowed the defence to pause the video repeatedly while questioning her – so that shocking images of her were projected while she testified. The Court also permitted the creation and distribution of multiple printed booklets containing frame-by-frame stills of the assault. These booklets were visibly stacked on desks in the courtroom and used to interrogate her in extreme detail. She was very disturbed by the thought of who all had seen these images, as surely the lawyer didn’t print, cut, and professionally bind these himself.

Rather than recognizing the trauma of being confronted with non-consensual recordings of her own sexual assault, the Court treated these materials as evidentiary tools for discrediting her. This approach not only retraumatized her but created a public and humiliating experience that furthered the original harm. Notably, the judgment did not acknowledge the voyeuristic nature of the recordings, nor the invasive impact of presenting them in this manner to the court.

- Survivor Interview #198

Scrutiny about what the victim did or did not do, instead of the actions of the accused, can determine the outcome of a case.[54]

- A combative style of sexual assault lawyering used to be promoted by senior members of the bar and taught in law schools.[55]

- Defence counsel who used aggressive techniques of cross-examining to the point of completely devastating the witness were considered brilliant.[56]

- If the objective of a criminal trial is truth-seeking, we should be asking questions that facilitate that objective rather than interfere with it.[57]

“Defence was able to throw outlandish statements or lies. ‘I’m going to suggest that you wanted this to happen to you…’ Trying to rattle you. Meant to get you off balance.” [58]

“To put a bulldog there to rip the person to shreds is barbaric.” [59]

In R v. Khaery, the victim was a 19-year-old Indigenous woman. She did not want to testify. A roommate and four first responders were eyewitnesses to the rape, but she was still subjected to five days of cross-examination:

“I was not prepared for the questions… I thought I could handle it, and by the end of the week, I was drained and just… I couldn’t cope with it mentally. I thought I was going to snap.”

After the third day of cross-examination, she took herself to the hospital because she was feeling suicidal.

Craig, E. (2018). Putting trials on trial: Sexual assault and the failure of the legal profession. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 71-75.

Trauma-informed approaches are grounded in evidence and consider the impact of trauma on the brain. Trauma and violence-informed approaches also take into consideration the impact of violence. They aim to transform policies and practices based on an understanding of the impact of trauma and violence on victims’ lives and behaviours. These approaches are compatible with and supported by efforts to make policies and practices culturally safer.[61]

Trauma-informed prosecutions can help the truth-seeking function of the courts and improve trust in the criminal justice process. Understanding the range of normal responses to trauma can prevent survivors from unfairly being treated as not credible or not reliable. For example:

- Self-blame and shame are common reactions to sexual assault. Trauma-informed prosecutions apply this knowledge to acknowledge that self-blame and shame do not mean the survivor consented.

- Sexual contact is a very private and personal topic in all cultures. Trauma-informed prosecutions apply this knowledge to understand that difficulty answering questions does not mean an effort to hide the truth.

- Misleading terminology can blur the truth for the complainant, the public, and the Court. Trauma-informed prosecutions are careful with words used to describe the acts in question.

- Terms such as “kissed” when describing an experience of sexual violence confuses an assault with a consensual sexual encounter. Trauma-informed prosecutions use descriptive and factual language such as “put their mouth on your mouth.” [62]

Trauma-informed prosecutions also take into account that the acts involved in a sexual assault are socially normative under different circumstances. This is not true for other forms of assault.

- A punch to the face is always an assault. A man putting his penis in a woman’s vagina can either be a consensual act of sexual intercourse or an act of violence.[63]

“If they stopped allowing defence attorneys to badger and destroy witnesses on the stand. You can discredit a witness without completely devastating someone.” [64]

Other countries are also working on improving trauma-informed justice.

The Government of Scotland has created a national program with a wide range of sectors and services to prevent and more effectively respond to adverse childhood experiences.

- The program provides education modules, training guides, and other references for anyone working with people who have experienced trauma.

- One of the key principles is to prevent further re-traumatization. The program recognizes that services and systems can create further traumatization and that policies, not just service providers, need to become trauma-informed.[65]

Case study: How identity shapes survivors’ experience of the criminal justice system

Background

In R v. N.S.,[66] a Muslim woman who wears a niqab reported being sexually abused as a child by her uncle and cousin. As a teenager, she disclosed the abuse to a teacher, but police did not lay charges. As an adult, she came forward again.

At the preliminary inquiry, the accused requested that N.S. remove her niqab to testify, arguing their right to cross-examination required seeing her face. Without legal representation, N.S. explained to the judge that wearing the niqab was part of her religious identity.

Despite this, the Court questioned the sincerity of her faith, pointing to her driver’s licence photo, in which her face was visible, implying inconsistency.[67] The Ontario Court of Appeal later rejected this reasoning and found it to be a form of “othering.” [68]

Constitutional Rights in Conflict

On appeal at the SCC, the focus shifted to a constitutional debate over religious freedom and trial fairness. The Court created a four-part balancing test for trial judges to apply when a witness’s religious covering is raised as a concern.[69]

In dissent, Justice Abella warned of the chilling effect:

“The majority’s conclusion that being unable to see the witness’ face is acceptable from a fair trial perspective if the evidence is ‘uncontested,’ essentially means that sexual assault complainants, whose evidence will inevitably be contested, will be forced to choose between laying a complaint and wearing a niqab, which, as previously noted, may be no meaningful choice at all.” [70]

At a second trial, N.S. was never given the opportunity to testify. The charges were eventually dropped.[71]

Bottom line: Survivors from marginalized backgrounds may have their evidence intensely scrutinized or challenged in ways that discredit them and distract from the violence they endured. By insisting N.S. remove her niqab in order to proceed, the accused and the legal system mirrored aspects of the harm she reported, forcing unwanted exposure, shame, and vulnerability upon her.

Some cross-examination methods are unfair to survivors with intellectual disabilities or who are neurodivergent

“The right to cross-examination surely does not extend to the right to take advantage of vulnerable witnesses’ difficulties.” [72]

“We are making it so easy for men to sexually assault people with intellectual disabilities.” [73]

“Individuals with intellectual disabilities are four to ten times more likely to experience sexual assault than the general population.” [74]

Chief Justice McLachlin wrote, “to set the bar too high for the testimonial competence of adults with mental disabilities is to permit violators to sexually abuse them with near impunity.”

R v. D.A.I., 2012 SCC 5 (CanLII).

We heard that:

- When survivors with intellectual disabilities do get a chance to testify, some defence lawyers intentionally try and shut down their testimony through questions meant to confuse them.[75]

- Judges did not intervene often enough to assist witnesses with intellectual disabilities to ensure they understood the question.[76]

- During records admissibility and productions motions, victims with intellectual disabilities may be disproportionately impacted because

- they may not understand the reasoning to retain a lawyer

- they may disclose private information on their own that could be used against them

- they may consent to having their records accessed without knowing the impacts

- Some advocates believe that traditional methods of cross-examination are discriminatory against people with intellectual disabilities[77] and the use of complex language and questions may be particularly confusing on cross-examination for individuals with intellectual disabilities. They may be especially vulnerable to the heavily suggestive leading questions often used in cross-examination.[78]

“We must, of course, ensure that those with mental and physical disabilities receive equal protection of the law guaranteed to everyone by s. 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.” [79]

Section 15 (1) guarantees that “every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.” [80]

- The SCC has underscored that “the concept of equality does not necessarily mean identical treatment and that the formal ‘like treatment’ model of discrimination may in fact produce inequality.” [81]

- For witnesses with disabilities to be treated equally, they must be given a fair chance to express themselves. They should not be treated as less credible because their brain processes information in different ways.[82]

The International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities says: “States Parties shall recognize that persons with disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life” and “States Parties shall take appropriate measures to provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity.”

Article 12

Important advancements have been made to improve accessibility.

- Two testimonial aids (support person, testimony outside the courtroom or behind a screen) are presumptive for people with disabilities.[83]

- We learned that depending on where the survivor lives, closed circuit TV for testimony outside the courtroom may not be available.

Communication intermediaries are another option to increase access to the criminal justice process for people with intellectual disabilities or communication disabilities.

- Communication intermediaries can assist the Court with witnesses who communicate in a way that a traditional court is not equipped to understand.[84]

- Section 6 of the Canada Evidence Act[85] can be interpreted to permit and facilitate the use of communication intermediaries and ensure equality rights are respected.[86]

One example of the failure to protect people with disabilities came to light in a horrific situation of sexual abuse where residents with disabilities were sexually abused for years by a worker in their group home.

The person who abused them stated that “he waited to act on his urges until he was alone with the victims and targeted them because they were non-verbal and couldn’t report him.” [87]

- “I was told by a nurse in the ER that no one would believe me and it was not worth reporting. She said that I would be torn apart on the stand because I am diagnosed with borderline personality disorder.” [88]

Neurodivergence and credibility

A survivor who is neurodivergent, diagnosed with ADHD [Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder] and giftedness, was repeatedly mischaracterized as lacking credibility due to communication and cognitive traits consistent with her profile. For instance, the judge noted that her responses were sometimes so long that she “forgot the question,” implying evasiveness. In reality, this pattern reflects well-documented ADHD challenges with working memory and a tendency to provide detailed, contextual explanations, a common strategy used by neurodivergent and gifted individuals to ensure accuracy.

In one example, she corrected the defence lawyer, who claimed she had testified that the accused “slapped her on the vagina.” She refuted this, explaining that she did not and would not use that term because the vagina is an internal organ, and the accused had struck her vulva and clitoral area. Her precise use of language, driven by a need for factual accuracy and a fear of being perceived as dishonest, was instead interpreted as argumentative and ultimately contributed to the judge’s conclusion that she was not credible.

These examples mirror findings in current research, which demonstrate how neurodivergent witnesses are frequently misunderstood and discredited when their authentic communication styles are not recognized or accommodated in court.

The judge found that such behaviour is characteristic of unreliable witnesses, despite significant research showing that these are common traits among neurodivergent individuals. The judge described her testimony as lacking “spontaneity,” a term often used in credibility assessments to favour neurotypical communication styles.

These assessments failed to consider her neurodivergent cognitive profile and instead pathologized the very behaviours that are consistent with ADHD and gifted processing. Her testimony was judged not for its content or truthfulness, but for the way it was delivered.

SISSA Survivor Interview 198

Cross-examination can be profoundly traumatic for child survivors – especially when they have to testify twice

“He got a four-year prison sentence. But I got a life sentence.” [89]

Cross-examination is one of the most distressing parts of the criminal justice process for child victims.

- Some defence counsel try to ethically balance arguing for their client while considering the impact of their approach on the child.

- When the system that children trust to protect them exposes them to the courtroom processes, they can feel manipulated and lose confidence in public institutions.

Preliminary Inquiries

“It is unbelievably frustrating to have children testify twice. It doesn’t make sense.

It is a spectacularly bad idea.” [90]

Testifying is a difficult, sometimes traumatizing experience for anyone. While procedural reforms have eliminated the need to testify twice for most adult survivors of sexual violence,[91] children are often still required to testify at a preliminary inquiry and at trial.

- Crown prosecutors told us there is zero need for preliminary inquiries.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

In 2019,[92] Parliament restricted the use of preliminary inquiries, recognizing that the discovery function of preliminary inquiries had become unnecessary since R v. Stinchcombe.[93]

- Parliament recognized that preliminary inquiries added to trial delays and to victim distress. However, the amendments retained preliminary inquiries for offences carrying a possible sentence of 14 years or more, such as sexual offences against children.

Delays in testifying

The criminal justice process often fails to recognize the urgency of a child’s experience. We heard:

- Two young girls waited over two hours in a courthouse to testify for a preliminary inquiry for charges of child sexual interference. The courtroom had multiple matters that day. Despite the Crown’s request, the judge did not prioritize the children’s evidence.

- To an adult, two hours of waiting may not seem like a long time. For a child, waiting in a courthouse, not knowing when or how they will be called to testify, can trigger physical and emotional distress.

- It can impact their ability to self-regulate and provide testimony in a coherent way. Yet it is a regular occurrence. This impact is not reflected in the transcripts or records.[94]

Even with a conviction, child survivors often come out of the process with no sense of justice.

An investigator’s reflection

During an in-person interview, an adult survivor of child sexual abuse sobbed as she described cross-examination and how she was treated by the defence counsel. She said, “He shred me to bits.” [95]

It was painful to sit in that despair, that dreadful acknowledgement that a courtroom full of professionals allowed this woman to be humiliated.

Best practices for trauma-informed justice for children and youth

Many police services across Canada have protocols to ensure that child and youth survivors of sexual violence receive trauma-informed justice.

- They work together with child and youth advocacy centres that are equipped to conduct child forensic interviewing.

Child forensic interviews are a critical component of the investigative and judicial response to child sexual violence. These interviews aim to gather accurate and reliable information from children and youth in a trauma-informed, developmentally appropriate manner. Those recorded interviews could be used during trial so the child is not required to testify in court.

- Access to such interviews across Canada remains inconsistent, with disparities in training, protocols, and availability of services.

- Equitable access to high-quality forensic interviews is essential for protecting children’s rights, supporting their recovery, and ensuring justice.

- A coordinated national strategy including standardization of forensic interview protocols is needed to address current gaps and uphold the dignity and safety of all children and youth who have experienced sexual violence.[96]

Cross-examination of expert witnesses

During this OFOVC investigation, one of our investigators interviewed an expert on sexual assault law.

The expert asked, “have you ever been cross-examined?” I said no, I hadn’t.

She said, “I have. Twice. I was an expert witness at an inquest and at a human rights hearing. Those experiences were awful. I have refused to serve as an expert witness again.”

I admit, I was taken aback. She is an admired, well-known, well-respected lawyer, academic, and professor. She is confident, well-versed, a leader in the field, and has published on this topic multiple times.

Her experience being cross-examined was so awful, she would never put herself through that again. She wasn’t even the complainant.

How could a complainant, possibly traumatized already, be expected to go through with it when a highly respected and seasoned expert, invited to provide expertise for the courts, finds it unbearable? [97]

TAKEAWAY

TAKEAWAY

A just system prevents tactics that retraumatize

rather than test credibility

Legal questioning must never become sanctioned harm

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Interview #21

[2] SISSA Survivor Survey

[3] R v. Osolin, 1993 CanLII 54 (SCC).

[4] R v. Osolin, 1993 CanLII 54 (SCC), at para 669-670.

[5] R v. Stinchcombe, 1991 CanLII 45 (SCC).

[6] Cunningham, M. (2018). What Does #MeToo Mean for Crowns? Why Trauma-Informed Prosecutions are Necessary.

[7] Herman, J. L. (2005). Justice from the victim’s perspective. Violence Against Women, 11(5), 571–602.

[8] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #7

[9] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response#175

[10] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #21

[11] SISSA Survivor Interview #004

[12] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #386

[13] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #439; Mattoo, D., & Hrick, P. (2025). The criminal justice system keeps failing sexual-assault survivors. There has to be a better way. The Globe and Mail.

[14] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #341

[15] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #196

[16] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #007

[17] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #590

[18] SISS Survivor Interview, #121

[19] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #82

[20] R v. A.G., 2000 SCC 17 (CanLII), at para 2.

[21] R v. Kruk, 2024 SCC 7 (CanLII).

[22] R v. Kruk, 2024 SCC 7 (CanLII), at para 36.

[23] R v. Kruk, 2024 SCC 7 (CanLII), at para 35.

[24] Cunningham, M. (2018). What Does #MeToo Mean for Crowns? Why Trauma-Informed Prosecutions are Necessary. Heinonline.org.

[25] Dufraimont, L. (2019) Myth, Inference and Evidence in Sexual Assault Trials. Queen's Law Journal, 44(2), 316

[26] SISSA Focus Group 02

[27] SISSA Survivor Interview #015

[28] SISSA Survivor Interview #030, #121

[29] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #199

[30] R v. Mills, 1999 CanLII 637 (SCC), at para 119.

[31] Haskell, L., & Randall, M. (2019). The impact of trauma on adult sexual assault victims. Department of Justice Canada.

[32] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #151

[33] WomenattheCentrE. (2020). Declarations of truth: Documenting insights from survivors of sexual abuse.

[34] Ibid

[35] SISSA Stakeholder Interview, #17

[36] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #494

[37] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #21

[38] R v. Lyttle, 2004 SCC 5 (CanLII), at para 43.; R v. Osolin, 1993 CanLII 54 (SCC), at para 663-665.

[39] R v. J.J., 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII), at para 183.

[40] R v. Lyttle, 2004 SCC 5 (CanLII), at para 47.

[41] R v. Khelawon, 2006 SCC 57 (CanLII), [2006] 2 SCR 787, at para 48.

[42] R v. J.J., 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII), [2022] 2 SCR 3, at para 184.

[43] Haskell, L., & Randall, M. (2019). The impact of trauma on adult sexual assault victims. Department of Justice Canada.

[44] Jurist, E., & Ekhtman, J. (2024). Truth and repair: How trauma survivors envision justice. Psychoanalysis Culture & Society.

[45] Cunningham, M. & Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General. (2023, July 26). Presentation to OFOVC on Trauma Informed Prosecutions [Presentation].

[46] Craig, E. (2018). Putting trials on trial: Sexual assault and the failure of the legal profession. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 220.

[47] SISSA Stakeholder interview #113

[48] Craig, E. (2018). Putting trials on trial: Sexual assault and the failure of the legal profession. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 220.

[49] SISSA Survivor Interview #094

[50] Horsburgh, M. (2025, May 28). Opinion: In junior hockey players’ trial, what could go wrong, did. Winnipeg Free Press.

[51] Cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. This phrase appears in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, section 12. The purpose of section 12 is to prevent the state from inflicting physical or mental pain and suffering through degrading and dehumanizing treatment or punishment. It is meant to protect human dignity and respect the inherent worth of individuals. Charterpedia, Justice Canada.

[52] SISSA Survivor interview #106, Stakeholder interview #019

[53] SISSA Stakeholder interview #019

[54] Cunningham, M. & Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General. (2023, July 26). Presentation to OFOVC on Trauma Informed Prosecutions [Presentation].

[55] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #113

[56] Craig, E. (2018). Putting trials on trial: Sexual assault and the failure of the legal profession. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 63.

[57] Benedet, J., & Grant, I. (2012). Taking the stand: Access to justice for witnesses with mental disabilities in sexual assault cases. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(1), 1–45.

[58] SISSA Survivor Interview #004

[59] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #21

[60] Craig, E. (2018). Putting trials on trial: Sexual assault and the failure of the legal profession. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 71-75.

[61] Ponic, P., Varcoe, C., & Smutylo, T. (2016). Trauma- (and violence-) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: Policy and practice considerations. In Victims of Crime Research Digest (No. 9). Department of Justice Canada.

[62] Cunningham, M. & Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General. (2023, July 26). Presentation to OFOVC on Trauma Informed Prosecutions [Presentation].

[63] Cunningham, M. (2018). What Does #Metoo Mean for Crown. Crown’s Newsletter, 9, 20.

[64] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #52

[65]Roadmap for Creating Trauma-Informed and Responsive Change | NHS E. (2023, November 22). NHS Education for Scotland.

[66] R v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72 (CanLII), [2012] 3 SCR 726.

[67] Hassan, M. (2024). Gendered racialization and the Muslim identity: the difference that ‘difference’ makes for Muslim women complainants in Canadian sexual assault cases (T). University of British Columbia.

[68] Hassan, M. (2024). Gendered racialization and the Muslim identity: the difference that ‘difference’ makes for Muslim women complainants in Canadian sexual assault cases (T). University of British Columbia.

[69] R v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72 (CanLII), at para 9.

[70] R v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72 (CanLII), [2012] 3 SCR 726, at para 96.

[71] Bureau, A. H. C. H. (2014, July 17). Sex-assault case that led to Supreme Court niqab ruling ends abruptly. Toronto Star.

[72] Benedet, J., & Grant, I. (2012). Taking the stand: Access to justice for witnesses with mental disabilities in sexual assault cases. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(1), 1–45.

[73] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #131

[74] Disabled Women’s Network (DAWN Canada) Community Impact Statement. (May 2022). Community Impact Statement - Women and Girls with Disabilities and the Impact of Sexual Assault - Dawn Canada; Individuals with intellectual disabilities are four to ten times more likely to experience sexual assault than the general population, Inclusion Canada. (2024, January 26). Press Release: Inclusion Canada demands justice in light of inadequate sentencing in Brent Gabona case.

[75] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #113

[76] Benedet, J., & Grant, I. (2012a). Taking the stand: Access to justice for witnesses with mental disabilities in sexual assault cases. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(1), 1–45.

[77] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #131

[78] Benedet, J., & Grant, I. (2012). Taking the stand: Access to justice for witnesses with mental disabilities in sexual assault cases. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 50(1), 1–45.

[79] R v. Pearson, 1994 CanLII 8751 (BC CA), at para 36.

[80] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c. 11.

[81] Government of Canada, Department of Justice, (2025a, July 14). Charterpedia - Section 15 – Equality rights.

[82] Lim, A., Young, R., & Brewer, N. (2022). Autistic Adults May Be Erroneously Perceived as Deceptive and Lacking Credibility. National Library of Medicine.

[83] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, ss. 486.1, 486.2. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/page-175.html#h-1041671

[84] Communication Disabilities Access Canada. Communication intermediaries. (n.d.).

[85] Canada Evidence Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-5, s. 6. reads “6 (1) If a witness has difficulty communicating by reason of a physical disability, the court may order that the witness be permitted to give evidence by any means that enables the evidence to be intelligible. (2) If a witness with a mental disability is determined under section 16 to have the capacity to give evidence and has difficulty communicating by reason of a disability, the court may order that the witness be permitted to give evidence by any means that enables the evidence to be intelligible. “

[86] Birenbaum, J., Collier, B., & Communication Disabilities Access Canada (CDAC). (2017). Communication intermediaries in justice services. In Access to Justice for Ontarians Who Have Communication Disabilities. CDAC.

[87] McAdam, B. (2024). Former Sask. care aide gets 6.5 years for sexually abusing people with disabilities. Saskatoon StarPhoenix

[88] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #697

[89] SISSA Survivor Interview #012

[90] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #173

[91] Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2022). Legislative Background: An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, as enacted (Bill C-75 in the 42nd Parliament).

[92] Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2022). Legislative Background: An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, as enacted (Bill C-75 in the 42nd Parliament).

[93] R v. Stinchcombe, 1991 CanLII 45 (SCC), [1991] 3 SCR 326

[94] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #17

[95] SISSA Survivor Interview #090

[96] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #195 and Written Submission, Luna Child and Youth Advocacy Centre

[97] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #200