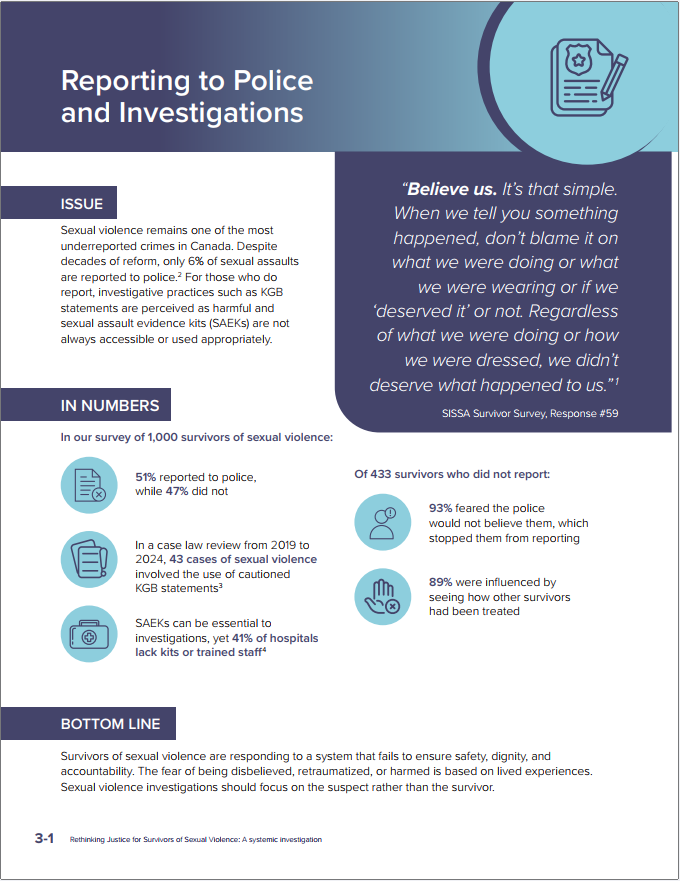

Reporting to Police and Investigations

“Believe us. It’s that simple. When we tell you something happened, don’t blame it on what we were doing or what we were wearing or if we ‘deserved it’ or not. Regardless of what we were doing or how we were dressed, we didn’t deserve what happened to us.” [1]

ISSUE

Sexual violence remains one of the most underreported crimes in Canada. Despite decades of reform, only 6% of sexual assaults are reported to police.[2] For those who do report, investigative practices such as KGB statements are perceived as harmful and sexual assault evidence kits (SAEKs) are not always accessible or used appropriately.

In Numbers

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- 51% reported to police, while 47% did not

- Of 433 survivors who did not report:

- 93% feared the police would not believe them

- 89% were influenced by seeing how other survivors had been treated

- In a case law review from 2019 to 2024, 43 sexual violence cases involved the use of cautioned KGB statements[3]

- SAEKs can be essential to investigations, yet 41% of hospitals lack kits or trained staff[4]

KEY IDEAS

- Survivors feared being blamed, judged, or not believed, a sentiment that was nearly universal

- Safety concerns and economic barriers are deeply interconnected. Survivors can’t risk retaliation, or losing housing, income and above all child custody

- Survivors report to protect others, often at personal cost

- They are experiencing more positive interactions with police, yet significant barriers remain in some investigative practices

- Sexual assault evidence kits are not available in rural and remote communities

- Trauma-informed protocols for sexual violence investigations are promising but are not always followed

BOTTOM LINE

Survivors of sexual violence are responding to a system that fails to ensure safety, dignity, and accountability. The fear of being disbelieved, retraumatized, or harmed is based on lived experiences. Sexual violence investigations should focus on the suspect rather than the survivor.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1.1. Implement the Calls for Justice from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls to improve policing and investigative practices:

a. Ensure equitable access to trauma-informed practice and investigative tools such as sexual assault evidence kits in all communities, including rural, remote and northern regions, in line with Call for Justice 5.5.

b. Embed Indigenous-led oversight and accountability in policing responses to sexual violence, ensuring culturally safe practices that respect Indigenous legal traditions and self-determination, in line with Calls for Justice 9.1 and 9.2.

c. Invest in Indigenous-led, community-based victim services to support survivors through reporting and investigation processes, in line with Calls for Justice 5.6, 16.29, and 17.28.

1.2 Evaluate trauma-informed protocols for police investigations. External monitoring promotes accountability and accessibility for equity-seeking groups.

1.3 Provide ongoing training to criminal justice actors on the unique needs of survivors based on sex, gender, sexual orientation, race, culture, religion, age, ability, mental health, immigration status, income and access to housing, with attention to intersecting identities.

1.4 Stop using KGB cautions with survivors of sexual violence. These warnings treat survivors like suspects based on the myth that survivors of sexual violence are more likely to lie.

1.5 Address the invisibility of Black survivors in research on the criminal justice system. The federal government should invest in Black-led, community-based research on the experiences of Black women, girls, and gender-diverse people affected by gender-based violence, including sexual violence.

Our investigation

BACKGROUND

“When citizens fail to report crimes, it is fair to presume that in many cases they are making a judgment that reporting does not promote their own interests or even those of the larger community… this judgment should not be rejected summarily as irrational.” [5]

Sexual violence is one of the most underreported crimes in Canada. Only 6% of sexual assaults are reported to police.[6] Despite decades of reforms, criminal justice responses to sexual violence continue to fail survivors. Reporting sexual violence is often framed as an individual choice, but survivors consistently indicate that their silence is in response to systemic barriers, institutional failures, and inequality rather than personal unwillingness. Further complicating this picture, investigative tools like KGB statements and SAEKs can reinforce these barriers, intensifying survivors’ hesitation to engage with police. Public safety and confidence in the criminal justice system (CJS) remain at risk until the system confronts the structural conditions silencing survivors.

What we heard

“If I could go back in time, I wouldn’t report.” [7]

Roughly half (51%) of survivors in our survey had reported sexual violence to the police, including survivors in every province and territory in Canada.[8]

Barriers to reporting

Survivors who do not report sexual violence are often responding to systemic, practical, and identity-based barriers that make reporting unsafe, inaccessible, or unthinkable.

Survivors are silenced by myths and stereotypes

Myths and stereotypes about sexual violence reinforce biases in how we respond to sexual violence as a society. Survivors who disclose sexual violence are often disbelieved, shamed, or judged. When a survivor’s behaviour differs from expectations of how an “ideal victim” would behave, society can be quick to assign blame. Many of the assumptions of how a sexual assault survivor should behave are contrary to the common experiences of survivors.

For example, the assumption that a survivor would immediately distance themself from the perpetrator is not grounded in evidence and lacks understanding of complex trauma reactions to violence, breach of trust, coercion, grooming, exploitation, or economic and social interdependence.

Structurally, the continued prevalence of myths and stereotypes offer survivors little confidence that they will be believed, silencing them and reproducing conditions that enable perpetrators of sexual violence to continue harming others.

This context is foundational to understanding reasons why survivors do not report sexual violence.

Fears of being misbelieved

“I witnessed a friend go through the process and she wasn’t believed because she had been drinking and she knew the person. One of the people who did this was a friend who assaulted me while I was asleep and drunk.” [10]

In our survivor survey, 47% did not report to police. More than 9 in 10 survivors said the expectation they would not be believed stopped them from reporting: 93% did not expect the police would believe them, and 89% were influenced by seeing how other survivors had been treated.

Several survivors emphasized how gender, race, Indigeneity, and other social markers made them even less likely to be taken seriously. “The system is biased against those who have intersectional marginalized identities (race, ethnicity, Indigenous status, sexual identity) which causes individuals to refrain from reporting as to prevent further harm.” [11]

“Police do not believe women… women are never believed over men, it’s just a very sad fact. Identifying as an Indigenous woman from a small town, police do not like us –always taking the side of white people no matter what.” [12]

Internalized blame and shame

Internalized shame, often learned from social norms and past experiences of being dismissed, created a powerful disincentive to report, especially when survivors lived with or depended on the person who harmed them.

Survivors shared that they:

- Feared being blamed for being intoxicated at the time of the assault[13]

- Worried they would be “slut-shamed”[14] after the incident or did not report out of fear they would be[15]

- Did not want people in their social circle to know what happened

- Feared other negative social repercussions[16]

- Believed that rape only “counted” if committed by a stranger[17]

- 61% of survivors in our survey said reporting would shame or dishonour their family

"Shame has to switch sides.” [18]

Credibility and the “ideal victim”

Survivors described struggling with societal expectations around appropriate victim behaviour. Any deviation from this “expectation” often damaged their credibility:

“The system is very broken. I had to spend time becoming the best victim of crime I could be. There was no good way to show up. If I show up distraught, I get patted on the head. You have to be emotional enough for them to feel sorry for you but not so emotional to make it too difficult for them. Have to be dedicated enough but not so dedicated that you are calling them too often. Paradox. As the victim I was under constant scrutiny.” [19]

Social expectations around the “perfect victim” [20] continue to shape reporting behaviour and institutional responses. Survivors who do not fit these expectations, due to identity, behaviour, or trauma responses, are frequently reclassified as the “bad victim” who is unreliable, uncooperative, or not credible.[21]

- Trauma Responses. Normal reactions to trauma create barriers to reporting. A survivor may not be considered an ideal victim or witness if they struggle to remember the events of the assault in chronological order or have difficulty explaining them in a coherent manner.[22]

- Racialized survivors. Gendered racial stereotypes frame some survivors, especially Black women and girls, as promiscuous, angry, or manipulative, undermining their credibility.

- Survivors with disabilities may be more likely to be perceived as uncooperative, unreliable witnesses, or mentally unstable by police or justice actors, resulting in their complaints being dismissed.[23]

Black women’s sexual assault disclosure experiences are framed by their unique social space at the margins of society due to systemic race, gender, and class oppression.[24] Slatton and Richard argue that there are three areas of marginalization: the delegitimization of Black women as victims of rape, the social construction of Black women as inordinately strong, and the sanctioning of intra-racial sexual assault disclosure.

Survivors are silenced by risks to safety, income, housing, and child custody

“It is a privilege to be able to go through the criminal justice system. You have to have supports in areas of basic needs, language, childcare, housing and work requirements; the onus needs to be on the government to provide these supports.” [25]

For survivors who consider reporting, the practical costs and immediate threats to their safety often come at a cost they simply cannot afford. Survivors consistently emphasized that deciding to report involves evaluating concrete risks, from financial stability to physical safety.

“I had no money, no home to go to, no car, I couldn’t leave and had to subject myself to more of it because there wasn’t adequate resources to help a brand new single parent in this economy.” [26]

Reporting is often framed as a choice, but for many, it is a false choice in the absence of basic supports. Survivors told us clearly: reporting is a privilege they simply cannot afford. Survivors identified multiple interconnected practical barriers:

- 27% identified potential loss of income from taking time off work as a factor

- 15% feared reporting would jeopardize child custody

- While some programs have limited funds to alleviate barriers, we heard that it is grossly unfair to assume survivors can overcome logistical barriers to reporting, such as taking time off work and paying for parking, transportation, and lunch.[27]

In a submission by Ontario Native Women’s Association, they emphasized that the ability to lay a report, or to be able to testify against a perpetrator, can seem insurmountable when a victim’s basic safety and housing needs are not met.[28]

Survivors in rural, remote, and northern communities described additional barriers:

- Long distances to reach police stations, hospitals, or sexual assault centres[29]

- Limited access to specialized officers of trauma-informed services

- Greater risk of encountering the perpetrator in court, in public, or in community settings

Survivors fear retaliation

For many survivors, reporting violence to police could directly endanger their personal safety or the safety of their loved ones. Fear of retaliation was particularly pronounced in the context of living with the perpetrator, intimate partner violence, or situations involving trafficking or organized crime.[30]

Safety, both personal and relational, was cited as a significant barrier:

- 85% of survivors feared revenge from perpetrators if they reported

- 83% of survivors feared reporting would make things worse

Some survivors reported being threatened with blackmail, such as threats to share intimate photos of the victim with friends and work,[31] or received death threats.[32] Others reported they did not trust that the systems in place would adequately protect them.

“Policing as an institution is not set up to support survivors of sexual violence. They do more harm than good.”[33]

Sexual violence in intimate relationships is often dismissed or ignored

“I was terrified I would not see another day if I ever called the police. I lived with them and they made me completely dependent on them so it wasn’t easy to report & run, and if I reported, I would have to run fast and far.” [34]

45% of survivors identified an intimate partner as the perpetrator. Survivors often live with, rely on, or co-parent with the person who harmed them. These situations can create a context of coercive control where reporting is not only unsafe, but it can also be life threatening.

Reporting requires a broad system of support: housing, relocation, child protection, and income. Survivors of sexual violence within relationships are often met with disbelief.

“I was sexually assaulted once by my husband. I didn’t even get close to reporting it to police. I reported physical assault and dangerous behaviour affecting a child and this was summarily dismissed. I had one male officer present to my home. He suggested that I just got in my husband’s way. When the system doesn’t even handle this fundamental situation well, sexual assaults will not be reported.” [35]

These experiences reinforce many survivors’ and advocates’ beliefs that the justice system is not equipped to recognize or respond to sexual violence in ongoing relationships, particularly when the violence is psychological, coercive, or part of a broad pattern of abuse.

Survivors are silenced by perpetrators and limited access to resources

Some survivors do not initially recognize their experiences as sexual violence. Lack of language, knowledge, or social validation can delay disclosure.

Key reasons for delayed recognition:

- Stakeholders highlighted that “grooming” is commonly used by a perpetrator to prepare a victim for abuse and creates a solid barrier to disclosure. Survivors may be conditioned to believe the abuse is normal.[36]

- Age and power imbalance. Many survivors who were assaulted as children described not understanding what had happened until years later. At the time they lacked the cognitive tools or adult support to recognize or disclose the abuse.

- Coercion without physical force. Survivors may dismiss the experience because it did not involve physical violence or “fight back” responses.

- Intimate or trusted relationships. Abuse by a partner, coach, or authority figure is often misinterpreted as a “bad relationship” or “confusing experience.”[37]

- Lack of language or education. Survivors emphasized that the absence of accessible information about consent and sexual violence, particularly tailored to youth or marginalized communities, prevented them from recognizing the harm.[38]

Why identity matters

We heard of many additional barriers to reporting among survivors in marginalized communities:[39]

- Not wanting to reinforce racial stereotypes that target members of their community

- Living in poverty. Some victims do not want to report abusers because they are the only source of income for the family. If they go to jail, then there could be financial insecurity for the survivor or the family

- Experiences with the child welfare system. Concerns that this system will become involved and they will lose custody of children.

- Fear of being reported or deported (migrant workers, non-status, international students, and others)

- Language barriers can limit a survivor’s options for places to turn and people to talk to about what happened.[40] For example, a survivor expressed that they did not report the sexual violence they experienced because services were not inclusive of their cultural identity and practices[41]

Mistrust Rooted in Lived Experience

“Poor responses by police – [I was a] child witness to domestic violence in the 1980s and how my mother was treated (Indian under the Indian Act and non-Indigenous father who was the one everyone believed). I also heard how other survivors were treated, at hospital I felt racialized (questions asked at hospital such as were you drinking) – I felt blamed for what happened so going to the police felt pointless.” [42]

Survivors and stakeholders cited a series of systemic failures that increased harm and discouraged reporting:

- A lack of confidence that child protection services will protect children from sexual violence[43]

- Criminal justice systems prioritize the perpetrator and their rights, while survivors felt treated as objects or pieces of evidence[44]

- The trial process was viewed as lengthy and retraumatizing,[45] especially due to invasive cross-examinations (Chapter 4), repeated questioning, and prolonged delays (Chapter 3)[46]

- Survivors were aware of high evidentiary burdens to prove incidents of sexual violence,[47] low conviction rates, and minimal consequences for perpetrators, which made reporting feel useless[48]

- For children and youth, the court process often dragged on for years – at a young age this becomes part of their identity[49]

- Victims perceived that the system is designed to respond to one-time occurrences of sexual assault and ill-equipped to respond to patterns of coercive or repeat assaults within an intimate relationship[50]

- In cases involving perpetrators holding a position of power (e.g., police, military), survivors lacked confidence that the system would act impartially[51]

- There was a lack of trauma-informed responses from medical staff, including barriers to accessing SAEK[52]

- Post-secondary institutions would deny the issue or not know how to respond[53]

Racism, colonialism, and power dynamics make reporting even harder

“I do not trust police as individuals or a system. Policing by definition does not see me (a Black queer trans-human) as a person worth protecting.” [54]

Consider these statistics:

- Nearly 1 in 10 Indigenous people (8.4%, or 5.5% of First Nations people, 11.7% of Métis, and 11.5% of Inuit) reported being victims of at least one sexual assault, robbery or physical assault in the 12 months preceding the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS). This is double the proportion for non-Indigenous people (4.2%)[55]

- More than triple the proportion of sexual minority Canadians (7%) reported that they had been sexually assaulted than did heterosexual Canadians (2%)[56]

For Indigenous survivors of sexual assault, barriers to justice “stem from the long history and legacy of colonialism and the ongoing impacts of settler-colonial violence enshrined in Canada’s Justice system.” [57] Formal legal processes may do more harm than good, often reinforcing racist and sexist stereotypes about how and why Indigenous peoples experience violence.[58]

This distrust is not only historical but well documented:

- The Oppal Inquiry[59] found that police repeatedly failed to respond to missing persons reports from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and failed to prevent serial violence against mostly Indigenous women

- The National Inquiry into MMIWG,[60] although not specifically mandated to investigate policing, documented widespread accounts of police mistreatment, discrimination, and violence against Indigenous women and girls

- Research by Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada[61] found that Inuit women face racist and violent policing, slow responses to calls for help, and long-standing harms rooted in colonial police practices such as the displacement of Inuit communities and the mass killing of sled dogs

Our survey findings reinforce these lived realities across other marginalized groups:

- 70% of Black survivors (n = 10) and 61% of racialized newcomers (n = 18) cited racism in the justice system as a factor in deciding not to report

- 100% of 2SLGBTQIA+ survivors who are also Indigenous (n = 13) said fear of the court process was part of the reason they did not report

The distinct experiences of Black women, girls and gender-diverse people

“Black women deserve a specific mention. Our experiences are very different from other racialized groups… We are not protected—from the womb to the tomb.”[62]

Black women, girls, and gender-diverse people are disproportionately impacted by sexual violence in Canada. Yet their experiences often remain invisible in research, policy, and service delivery. Too frequently, their realities are folded into broader categories such as “racialized” or “people of colour,” obscuring the distinct and compounding harms they face.

From the outset, this investigation sought to engage survivors from historically underrepresented groups. We reached out to Black-led organizations, circulated our calls for survey and interview participation, and invited input across multiple engagement channels. However, participation from Black survivors remained limited. We understand this is not simply a matter of outreach—but one of trust, safety, and historical experience. We recognize that institutions connected to the criminal justice system may not be viewed as safe or welcoming spaces for many Black survivors.

Stakeholders and research emphasized that:

- Harmful stereotypes: The enduring myth of the “strong Black woman,” combined with hyper-sexualization, undermines Black survivors’ credibility and discourages disclosure. Stereotypes such as the “angry Black woman trope” perpetuate the assumption that Black women are hostile, aggressive, overbearing and ill-tempered.[63]

- Preliminary findings from the Truth and Transformation project of WomenatthecentrE show that 314 (69%) English-speaking survivors responded that they had experienced anti-Blackness while accessing services in the GBV sector and 24 (92%) French-speaking survivors responded that they had experienced anti-Blackness. 215 (93.07%) of English-speaking advocates responded that they had experienced anti-Blackness in a workplace/organization and 9 (75%) French-speaking advocates responded that they had experienced anti-Blackness in a workplace/organization.[64]

- Institutional betrayal: Black communities have faced generations of surveillance, dismissal, and violence at the hands of state systems, including police, child welfare, and courts. These legacies foster justified mistrust.

- A cycle of neglect: The absence of disaggregated data and targeted investment makes Black survivors structurally invisible, reinforcing underfunding, policy inaction, and lack of culturally appropriate supports.

We acknowledge the investment made in Canada’s Black Justice Strategy, and its 10-year Implementation Plan. The Strategy commits to reducing the over-representation of Black people in the criminal justice system, including as victims of crime. This is an important step forward.

While the Strategy largely focuses on incarceration, policing, and diversion, less attention has been placed on the lived realities of Black survivors. The policy response must not overlook Black survivors, specifically of sexual violence, whose experiences have received less attention.

“There is no policy when there is no research—and no research when there is no investment.”[65]

We would like to see that the implementation of Canada’s Black Justice Strategy includes sustained, dedicated investments in Black-led, community-based research for Black women, girls, and gender-diverse people affected by sexual violence. These efforts must not only centre Black survivors but be shaped and led by them.

Barriers to reporting for Muslim women

Muslim women face intersectional barriers when engaging with the criminal justice system.

Maira Hassan’s dissertation, which is the first study in Canada to examine how Muslim women are portrayed and treated in sexual assault cases, combines legal analysis and interviews with front-line support workers to document these systemic challenges. Hassan found that “In addition to the already challenging circumstance of reporting to police, there can be mixed reactions from police when it comes to Muslim women survivors reporting their experiences of violence. Interview participants related the unpredictable reactions by the police, including overreactions at times and sometimes dismissal of complaints by Muslim women’s experiences of violence. Where overreactions corresponded to seeing Muslim women experiencing violence as an opportunity to save ‘the oppressed woman,’ the dismissals related to ‘othering’ the violence as something expected as part of ‘the Muslim culture.’”[66]

Hassan highlights how gendered racialization and Islamophobic stereotypes continue to shape the reporting experience for Muslim women. At times, this leads to heightened surveillance and paternalistic attitudes. At others, it leads to minimization or dismissal of the harm they have experienced.

Reasons for Reporting

Survivors report to protect others

“I used to believe it would protect me and my children. Now I know the only protection offered is to the perpetrator, while I continued to receive threats, have my reputation destroyed, and have had to finance a move and identity change alone and have paid thousands of dollars in trying to recover not only from the sexual assaults, but the Justice system harm to me as well.” [67]

For many survivors, reporting is driven by a deep sense of responsibility to protect others, especially children, women, and members of their own communities.

“The reason I did this was to protect other women and girls. To see them warned about him. But the reality is that his sentence will almost certainly be less time than the period between when he was charged and when he’s sentenced. The criminal justice system is so offender-centric that the safety of victims isn’t even considered.” [68]

“When I was a little girl, many of us were sexually abused by those in high positions of trust and authority in my community. Today, this is still happening. It is why I decided to come forward.” [69]

“I reported because my abuser said things that made it clear he would do it to others and I didn’t want other women to suffer this. But I wouldn’t report again.” [70]

Survey findings echoed this motivation (n = 1,000):

51% (n = 505) of survivors reported to police. Survivors often considered many different reasons in the choice to report:

- 97% reported to prevent the person from doing it to someone else

- 97% sought accountability

- 86% feared their safety

- 83% wanted the abuse or sexual violence stop

- 52% cited the perpetrator’s position of authority

- 43% felt pressured by others

- 38% reported because of a legal duty to report for a child

We also asked survivors to share how important different reasons were in their decision to report sexual violence to the police:

- 4 in 5 survivors said that preventing the person from doing it to someone else was a very important reason for them

- 3 in 4 survivors said that holding the person accountable was a very important reason for them

What happened when they reported?

Many survivors described how reporting inflicted new harm, even when they came forward to protect others. Despite being motivated by a desire to protect others, survivors found themselves retraumatized, disbelieved, or excluded from the very process they initiated.

- “Involving the police was worse than being drugged and raped for 24 hours by a disgusting and pathetic predator. The dishonesty of the ‘brotherhood’ of a useless police force is sickening. The rape did some serious damage to my life. But reporting it, then chasing any chance of justice, has broken me.” [71]

- “Reporting a few years after the assault felt useless because the RCMP officer asked, ‘What do you expect from this?’ He made it sound like it was not even possible to lay charges or interview the person who assaulted me.” [72]

Survivors who reported often carried a double burden: the trauma of the violence itself and the trauma of navigating a system not built to support them. This is particularly serious for racialized survivors, who faced both systemic bias and lack of support.

Survivors had mixed experiences with police

Among the 51% of survivors who reported to police, experiences were mixed. While some encountered understanding and respectful treatment, others described retraumatizing interactions.

Survivors had very mixed experiences with police:

- 27% said police understood their trauma

- 29% said their report was treated as a high priority

- 33% said their views were considered

- 42% said the place where they were interviewed felt safe

- 45% said they were treated with courtesy, compassion and respect

- 49% said they felt like the police believed them vs 32% who reported not being believed

Police are providing survivors with more information on their cases

Survivors who reported sexual violence in recent years noted improvements in police communication and access to case-related information. Nearly half indicated they felt believed by police, marking a notable step forward. Additionally, our data show clear upward trends over the past two decades in police how police informed and engage survivors:

- Outcome information: The percentage of survivors who were told about the outcome of their investigation increased from 28% prior to 2007 to 47% in 2020 or later.

- Right to request case updates: Awareness of this right nearly tripled, from 13% prior to 2007 to 34% in recent years.

Persistent Gaps

Despite improvements in these areas, the overall performance indicators in other important areas remain low.

- 1 in 4 survivors were told they had the right to know the outcome of the investigation

- 27% were told they could request an update

- 19% reported receiving information about their rights under the CVBR

- Only 9% were told how to access independent legal advice

When asked explicitly about their case outcomes, 28% of survivors said they received no clear communication about what happened after they reported to police.

The attention turns toward survivors

Despite improvement in police communication, survivors continue to describe experiences that suggest a default attitude of suspicion. In our survivor survey:

- 28% said police discouraged them from reporting

- 40% of survivors said they felt blamed or shamed by police

- 47% said they did not feel their views were considered

KGB statements and the presumption of doubt

“Basically, it’s a three-minute soliloquy telling you what’s going to happen if you lie. These are not best practices in sexual violence – telling survivors before they even open their mouths what’s going to happen to them if they’re liars. So many places around the country have struggled to figure out how to get rid of these warnings.” [73]

Imagine coming forward after experiencing a violent crime, only to be cautioned in a way that leaves you, the survivor, feeling that: any minor mistake or forgotten detail could lead to your own imprisonment. This is how KGB statements are often perceived by survivors; not because police say this outright, but because that is how the warning is perceived by survivors. While rare in other violent offences, it is disproportionately applied in sexual assault cases.

What is a KGB statement?

KGB statements[74] are cautioned, sworn, video-recorded statements taken by police, a tool originally developed to preserve reliable evidence from witnesses who may be reluctant to testify or whose testimony may later change. They were primarily intended for use in cases involving co-accused individuals or witnesses in high-risk contexts, such as organized crime, where there is a concern about witness intimidation, recantation, or refusal to testify.[75]

- KGB statements include multiple warnings about criminal prosecution for lying, including references to prison terms longer than the maximum length for most sexual offences[76]

- The use of KGB statements varies significantly across Canada[77]

Research, stakeholder interviews, and submissions raised concerns about the use of KGB statements in sexual assault investigations:

- Survivors feel like they are not believed and may fear criminal charges[78]

- Warnings reduce the amount of information survivors provide to police,[79] suggesting they may have an adverse impact on the truth-seeking purpose of the interview

- Neurobiological responses to trauma can affect memory and recall, resulting in inconsistent statements over time[80]

- The warnings may cause survivors to withdraw from the system, fuelling attrition[81]

- In cases of GBV, the use of a KGB statement paired with the threat of criminal prosecution for non-compliance can coerce survivors into participation in the court process, even if it is contrary to their best interests[82]

A stakeholder echoed these concerns:

“You can see the person’s whole demeanour change, regardless of how delicately, empathetically, or how trauma-informed the officer tries to talk about these statements. As soon as you start getting into sentencing, you can just see that they are immediately recognizing that they’re not believed, that this isn’t for them. It’s heartbreaking to watch that and to have to keep seeing that.” [83]

KGB Statements are being reconsidered

We asked the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for their perspective on the use of KGB warnings given to survivors. They told us:

“Sworn statements would very likely have a detrimental effect on the quality of evidence obtained during the interview and on the well-being of sexual assault victims. It can be misinterpreted as disbelief of the victim and is not consistent with using a trauma-informed approach to investigations. Individual investigators should make a decision about whether it is in the best interests of justice to utilize the KGB procedure when interviewing a victim, bearing in mind the advantages and disadvantages of doing so, as well as the potential detrimental effect on the victim. It is important to remember that a sexual offence victim will rarely be asked to testify without their ongoing agreement to be involved.”[84]

While RCMP policy indicates KGB statements should be used sparingly, there is no formal tracking or oversight of this practice, nor a standard script or form. “They are created Divisionally in conjunction with Provincial Crown Counsels. This allows for regional differences such as requirements for the Commissioner of Oaths.”[85]

There is growing consensus that KGB statements should not be used in sexual assault cases:

- The Uniform Law Conference of Canada (ULCC) recognized the damage that recanting witnesses can do to a trial and to the administration of justice, and that prosecution for recanting KGB witnesses is exceptionally rare.[86]

- Some prosecution services acknowledge that it is not in the “public interest” to prosecute cases against survivors of intimate partner violence who report violence and later recant.[87]

- We heard how rare it was for a sexual assault complainants to recant and have a KGB statement introduced at trial in the previous 25 years.[88]

- Sexual Violence New Brunswick shared a report funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE), calling for an end to the use of KGB statements with survivors of sexual violence.[89]

Are KGB statements necessary?

There may be limited circumstances – such as a sex-trafficking case or where a survivor may not later be available to testify - where a KGB statement may help to safeguard the interests of survivors. Other evidence suggests that warning survivors may not be necessary.

As one stakeholder noted:

“Other provinces have found ways to have those conversations without slapping that warning in front of someone and saying, ‘If you’re lying, all these terrible things are going to happen to you.’” [90]

Given the discriminatory and harmful impact of warnings when survivors report sexual violence to police, the potential benefit must be weighed against the harm.

Alternatives to KGB statements:

- It may be sufficient to record a sworn statement, without administering a KGB caution.[91] Notably, multiple cautions of jail time are not provided to witnesses in court.[92]

- Limit the scope of cautions. If a caution is deemed necessary, it should be brief, neutral, and trauma-informed. There is no need to repeatedly threaten lengthy jail time.

Sexual assault evidence kits are not always available

Another investigative tool that survivors identified as harmful were SAEKs. Though designed to preserve forensic evidence that may support a prosecution, the SAEK process often adds trauma, delays, and unnecessary burden.

SAEKs are typically framed as essential investigative tools. However, their evidentiary value may be limited in sexual assault cases:

- While SAEKs can help with investigations where the perpetrator is unknown or where there are serious injuries, 87% of accused persons in sexual assault cases were known to the victim.[93] These cases often involve no visible injury and no dispute that sexual activity occurred, the issue is one of consent, making the evidentiary value of SAEKs limited.

The RCMP offered their perspective:

“Even in cases where the accused is known to the survivor and there is no dispute that sexual activity occurred, sexual assault evidence kits (SAEKs) can still provide valuable confirmatory evidence. DNA evidence can:

- corroborate the survivor’s account of when and how the contact occurred.

- strengthen the case by removing the possibility of a denial defence, where the accused claims no sexual contact took place.

- support timelines and context, especially when combined with other forms of evidence (e.g., text messages, witness statements).

While SAEKs may not always be necessary, their potential to reinforce credibility and reduce ambiguity in legal proceedings should not be underestimated. The key is ensuring survivors are fully informed about their options and that the use of SAEKs is guided by trauma-informed, survivor-centred practices.”[94]

Accessibility

In many parts of Canada, SAEKs are unavailable or difficult to access:

- 41% of hospitals and health centres in Canada lack either kits or staff who are trained to administer them.[95]

- In rural and remote northern communities, access to SAEKs is limited. Stakeholders told us that the lack of local services means survivors are transported for hours by taxi or flown out of their community to undergo the examination.[96]

- Survivors described being examined by doctors with little or no training in sexual assault response, including fly-in physicians reading SAEK instructions for the first time.[97]

“[I had to] drive over 2 hours to [the city] to get a rape kit done because it wasn’t available in my town.” [98]

Waiting rooms in small communities also raises serious privacy concerns. This disproportionately affects survivors in close-knit northern, Indigenous and rural communities where anonymity is difficult. Patients are often asked intrusive questions about why they are seeking care.

Call for Justice 5.5 of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls specifically urges all governments to build capacity in investigative tools for sexual violence—including access to sexual assault kits and trauma-informed questioning techniques.[99] This call emphasizes the need to ensure that all Indigenous communities, particularly in remote and northern regions have timely and equitable access to these resources.

Pressure to Undergo SAEKs

Many survivors reported that police and even some health professionals pressured them to undergo a sexual assault exam in order to report the assault. Others were told, incorrectly, that without a rape kit, their case would be dismissed.

“Police do not believe women, and I have been told (by police officers) that if I did not have a rape kit done immediately after then the case would be thrown out as I could not prove the incident. Women are never believed over men, it’s just a very sad fact. It also does not help that I am Indigenous, and police especially in my small town do not like us. Always taking the side of white people no matter what.” [100]

These experiences reflect the persistence of rape myths and misinformation. These myths reinforce harmful stereotypes, for example, that sexual violence always results in injury, that complainants are more likely to lie about an assault, and that sexual violence is committed by strangers unknown to the victim.

- They also perpetuate the false idea that forensic evidence is required to validate sexual assault, which contributes to the overuse and misuse of SAEKs. Jane Doe’s interviews with women about sexual assault evidence kits revealed that they were “unnecessary, invasive, and terrorizing”[101]

The RCMP shared their views on the harmful aspects of SAEK:

“Sexual assault evidence kits (SAEKs) are not inherently harmful tools. When used appropriately and with trauma-informed care, SAEKs are designed to preserve critical forensic evidence that can support a survivor’s case, should they choose to pursue legal action. When administered with informed consent, sensitivity, and respect for the survivor’s autonomy, SAEKs can be empowering and play a vital role in justice processes. Many survivors choose to undergo the evidence collection process because they want the option to report or seek justice in the future.”[102]

Harm and revictimization during the examination

Some sexual assault survivors have described these forensic exams as a “second rape.”

“The whole process of getting a rape kit is also fully retraumatizing.” [103]

“I was also told by my nurse that if I did not think I wanted to report, the kit would be a really uncomfortable experience for my male doctor to have to do. Instead, they gave me Valium to help me ‘forget,’ in the doctor’s words.” [104]

Even so, some survivors report being pressured to involve police if they want to have an exam done.

“I was required to report to police to be able to have a rape kit done at the hospital. That was hard as I didn’t know anything about reporting or the criminal system or laying charges. I just wanted what happened to me to be acknowledged/recorded and to check my health. I did decide to proceed with reporting after they told me the police wouldn’t lay charges if I wasn’t ok with it. I had to give my report right then, alone in a private hospital room with two male cops. That was hard, I didn’t feel safe. I had just been [sexually assaulted] the night before and the man who did it wouldn’t let me leave until I talked him into letting me go. I wish a female nurse or someone else from the medical team stayed with me in the hospital room when the cops came. I was not aware or thinking that I could ask for this at the time. Later the police did the investigation, but I had to ask them if they tested my blood samples. They did not until I asked, and it turned out that I was severely drugged… I don’t think they were listening when I told my story, that I thought I was drugged. Maybe I didn’t say it directly enough.” [105]

The linking of reporting and forensic medical examination deters survivors who are not yet ready to engage with the justice system but still want medical care or to preserve evidence. We need to better protect survivors’ privacy interests over their own bodies.

Privacy and SAEK

A sexual assault examination kit (SAEK) records, on a specific forensic form, an examination done by a qualified medical practitioner. The complainant must consent to that form being released to the police, even if an investigation is underway. An Ontario case found that the SAEK was not a private record and that the nurse conducting the exam was part of the investigation of the sexual assault.* This meant that the complainant had no privacy interest in the SAEK.

- This is in stark contrast to how any other medical record would be viewed. Medical records, by any definition, are records to which a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy.

- This decision puts more emphasis on where the information is written (a forensic form) compared to what the information is (facts about the complainant’s physical and mental integrity from a medical exam).

* R v. T.C. 2021 ONCJ 299 (CanLII).

Delays and processing failures

Delays in SAEK testing stall investigations and, in some cases, jeopardize prosecutions. Survivors reported cases where kits were only partially processed, often without a clear explanation.

“To my knowledge the rape kit never made it to any database. I think it may have been destroyed. I have no idea, and I cannot find answers when I call them.” [106]

“There needs to be a better process for dealing with rape kits—I know it’s a cost and the government tries to save money, but not processing entire rape kits as soon as they’re collected is terrible. Such a low percentage of women go through with reporting and getting the kit done. Out of respect for those of us who do, there should be an investment in making sure that the evidence is duly processed in a timely manner. We were told that DNA testing could take up to 6 months!!” [107]

In some cases, partial processing may be appropriate, for example, when only certain samples are relevant to the live issues in a case, such as suspected drug-facilitated sexual assault or questions about intoxication. However, when survivors are not informed of what was tested or why, a lack of transparency can cause distrust.

One survivor shared that the accused delayed entering a plea for months because DNA results had not been received. The survivor had to personally follow up to confirm that her blood samples had even been tested, only to learn they had not been processed until she insisted.[108]

- A 2017 evaluation found that the RCMP’s forensic labs met their 40-day DNA processing target in only 44% of routine sexual assault cases.[109]

Such delays may also jeopardize prosecutions.

- Under the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R v. Jordan, unreasonable delays can result in charges being stayed. SAEK processing delays, particularly when uncommunicated, worsen this risk while undermining trust in the criminal justice system.

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners can reduce re-traumatization

“My choice ended at the hospital emergency room. I was not ready to make a decision about reporting but wanted to get a sexual assault kit done so that I had the option available. They were completely uneducated in handling my care. I was informed that I could only get the kit done if I was reporting.”[110]

Many survivors described uncomfortable or even traumatic experiences during SAEK exams, particularly when conducted by untrained or reluctant medical professionals. In contrast, Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs) were highlighted as a promising model for delivering compassionate, expert care.

- SANEs are trained to conduct forensic exams, document injuries, collect evidence properly, and testify in court. They are more likely to provide trauma-informed care, take survivors seriously, and ensure survivors understand their options.

“Some places have specially trained nurse teams that are called out to conduct rape kits are willing to testify, and act as a guide through the health system. That would have helped a lot.”[111]

However, stakeholders noted that most hospitals do not have specialized nurses trained on administering SAEKs.[112] In regions without SANEs, survivors described being examined by providers who were unprepared, uncomfortable, or dismissive:

“The doctor at the university did not want to take the pictures (of my injuries) or be involved. I learned later it was because they did not want to waste time testifying.”[113]

We also heard of remote fly-in physicians administering SAEKs without adequate knowledge, sometimes consulting instructions during the exam. These situations can create confusion, fear, and additional trauma for survivors. In some cases, local nurses could have provided better care but were prevented from doing so by institutional policy.[114]

Case Study: Racialized Harm and Survivor Advocacy1

In 2013, at age 17, Joëlle Kabisoso was sexually assaulted by five white boys. The assault was recorded and publicly mocked online, including a tweet “four little monkeys sitting on a bed, 2 got raped and one just bled,” which underscores the intersection of hate and sexual violence.

Despite the overt racism and brutality, Joëlle recalls that the detective assigned to her case dismissed the harm, telling her: “Maybe next time you shouldn’t drink so much.” Rather than support, Joëlle encountered institutional suspicion and indifference- an experience echoed in our survivor survey, where one survivor wrote: “Les femmes noires agressées ne sont aucunement prises au sérieux.” “Assaulted black women are not taken seriously at all.” [Translation]

From this trauma, Joëlle emerged as a leading voice for change. In 2018, she founded Sisters in Sync, a space for other Black girls and women to share their experiences of sexual violence.

- Today, Sisters in Sync continues to build healing-centred, survivor-led spaces for Black women and youth in Hamilton, Ontario. Joëlle’s work exemplifies how survivors transform systemic betrayal into community leadership and policy change.

1 Stakeholder interview #104; Survivor Survey #691.

Moving toward a trauma-informed approach

We heard about several promising reforms grounded in mitigating trauma:

- The Canadian Framework for Trauma Informed Response in Policing (2024)[115] was developed as a collaborative effort between police services across Ontario and Québec and the RCMP. The framework integrates principles of procedural justice and guides police services to embed trauma-informed policies, standards, and practices and includes considerations specifically to sexual assault, domestic violence, and child abuse.

- British Columbia’s 2024 provincial standards for victim interviews in sexual assault investigations require that interviews must avoid re-traumatization, support victim dignity, minimize repetition, provide accommodations, and give survivors control over where, when, and how they participate.[116]

- Innovative tools offer survivors more control. The paceKit initiative[117] allows for self-collection of DNA evidence with support from a trained frontline worker. Survivors use the kit to swab for DNA, submit clothing, and document the incident on their own terms.

It provides accessibility for people who live in rural and remote communities. Currently piloted in BC, the program is focused on improving access for Indigenous communities and plans to expand.[118]

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve safety at every step from the first disclosure

to the last piece of evidence

Reporting sexual violence should not open the door to suspicion, delay, or further harm.

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response # 59

[2] Statistics Canada conducts the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety every 5 years. It is a large victimization survey that collects self-reported data on criminal victimization from all provinces and territories. It includes questions on whether people reported a crime to police.

[3] Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review.

[4] She Matters. (2025). Silenced: Canada's sexual assault evidence kit accessibility.

[5] Finkelhor, D. (2008). Childhood Victimization: Violence, Crime, and Abuse in the Lives of Young People. New York: Oxford University Press.

[6] Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, & Cotter, A. (2024). Criminal justice outcomes of sexual assault in Canada, 2015 to 2019.

[7] SISSA Survivor Interview #31

[8] 51% (n = 503) is a significant over-representation of survivors who generally report to police. Since the reporting rate in Canada is roughly 6% according to the 2019 GSS, a sample of 503 survivors who reported to police would typically require a victimization survey with a sample size of approximately 8,500 people.

[9] *There is overlap in cases reported to police directly by survivors and those reported by someone else for a total of 548 cases reported to police.

[10] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #30

[11] SISSA Consultation Table #09: 2SLGTBQIA+ English

[12] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #118

[13] SISSA Survivor Survey 148; Survivor Survey, Response #30

[14] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #142

[15] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #348

[16] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #348

[17] Survivor Survey, Response #101

[18] Survivor Survey, Response #167

[19] SISSA Survivor Interview #093

[20] SISSA Survivor Interview #024

[21] SISSA Written Submission #33

[22] SISSA Written Submission #37

[23] SISSA Consultation Table #27: Independent SAC FR

[24] Slatton, B.C., & Richard, A.L. (2020) Black Women's experiences of sexual assault and disclosure: Insights from the margins. Sociology Compass, March 2020, 14(6). DOI:10.1111/soc4.12792

[25] SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women’s NGO/Advocacy Orgs EN

[26] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #106

[27] SISSA Survivor Interview #159

[28] SISSA Written Submission #31

[29] SISSA Consultation Table #13: Legal & ILA

[30] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #656: SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #88; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #106

[31] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #64

[32] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #49; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #172; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #656

[33] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #42

[34] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #106

[35] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #692

[36] SISSA Written Submission #69

[37] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #229

[38] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #259

[39] SISSA Consultation Table #08: Black and Racialized BIL; SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women’s NGO/Advocacy Orgs EN; SISSA Survivor Interview #178; SISSA Survivor Interview #021; SISSA Consultation Table #23: Academics EN; SISSA Consultation Table #06: Newcomers BIL

[40] SISSA Written Submission #38

[41] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #426

[42] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #915

[43] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #249

[44] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #024

[45] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #90

[46]SISSA Written Submission #37

[47] SISSA Survivor Interview #086

[48] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #263

[49] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth EN; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #364

[50] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #656

[51] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #253

[52] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #202

[53] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #569

[54] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #326

[55] Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2022b). The Daily — Criminal Victimization of First Nations, Métis and Inuit People in Canada, 2018 to 2020.

[56] Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, Jaffray, B., & Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics. (2020). Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018.

[57] Barkaskas, P. & S. Hunt. (2017). Access to justice for Indigenous adult victims of sexual assault. Department of Justice Canada.

[58] Barkaskas, P. & S. Hunt. (2017). Access to justice for Indigenous adult victims of sexual assault. Department of Justice Canada.

[59] Oppal, W. (2012). Forsake: The Missing Women Commission of Inquiry.

[60] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Final Report: Reclaiming Power and Place.

[61] Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (2020). Addressing Gendered Violence against Inuit Women: A Review of Police Policies and Practices in Inuit Nunangat.

[62] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #196.

[63] Motro, D., Evans, J. B., Ellis, A. P. J., & Benson, L. III. (2022). Race and reactions to women’s expressions of anger at work: Examining the effects of the “angry Black woman” stereotype. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(1), 142–152.

[64] Interim findings shared with OFOVC, July 28, 2025, WomenatthecentrE

[65] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #196

[66] Hassan, M. (2024). Gendered racialization and the Muslim identity: the difference that ‘difference’ makes for Muslim women complainants in Canadian sexual assault cases (T). University of British Columbia.

[67] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #22

[68] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #891

[69] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #439

[70] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #454

[71] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #70

[72] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #260

[73] SISSA Consultation Table #21: Independent Sexual Assault Centres

[74] The practice stems from the 1993 Supreme Court of Canada decision in R v. B. (K.G.),[73] which established a legal framework to admit hearsay evidence from adverse witnesses who provided prior inconsistent statements. This was a departure from the general rule that out-of-court statements are inadmissible hearsay.

[75] Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review.

[76] Survivors are told they may face up to 14 years in prison if they knowingly make a false statement-longer than many sentences for sexual assault. Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review.

[77] Uniform Law Conference of Canada. (2012). Working group on contradictory evidence: Criminal liability for recanted K.G.B. statements.

[78] SISSA Written Submission #35

[79] Snook, B., & Keating, K. (2011) A field study of adult witness interviewing practices in a Canadian police organization. Legal Criminal Psychology, 16(1), 160-172.

[80] Snook, B., & Keating, K. (2011) A field study of adult witness interviewing practices in a Canadian police organization. Legal Criminal Psychology, 16(1), 160-172.

[81] Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review. 6.

[82] Hoffart, R. (2021). Keeping women safe? Assessing the impact of risk discourse on the societal response to intimate partner violence. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Manitoba]. FGS—Electronic Theses and Practica.

[83] SISSA Consultation Table #21, Independent Sexual Assault Centres.

[84] RCMP Response to Questions from the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Violence for Systemic Investigation on Sexual Violence, May 7, 2025.

[85] RCMP Response to Questions from the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Violence for Systemic Investigation on Sexual Violence, May 7, 2025.

[86] Uniform Law Conference of Canada (2013). Working group on contradictory evidence: Criminal liability for recanted K.G.B. statements.

[87] Uniform Law Conference of Canada (2013). Working group on contradictory evidence: Criminal liability for recanted K.G.B. statements.

[88] Roussel, P. (2021). Inter-office memo: Sexual offense cases-KBG statement from complainant. Department of Justice and Public Safety, Government of New Brunswick.

[89] SISSA Written Submission #35

[90] SISSA Consultation Table #21, Independent Sexual Assault Centres

[91] Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review.

[92] Craig, E. (2025 Forthcoming). The Discriminatory Use of the ‘KGB Procedure’ by Police Against Women in Canada. McGill Law Review.

[93] Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, Rotenberg C. (2017). Police-reported sexual assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014: A statistical profile.

[94] Input provided by the RCMP, received July 25, 2025.

[95] She Matters. (2025). Silenced: Canada’s sexual assault evidence kit accessibility.

[96]SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crowns

[97] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #8

[98] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #145

[99] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls—Calls for justice.

[100] Survivor Survey, Response #118

[101] Sheehy E. (2012). Who Benefits from the Sexual Assault Evidence Kit? in Sexual Assault in Canada: Law, Legal Practice and Women’s Activism. University of Ottawa Press.

[102] Input from the RCMP, received July 25, 2025

[103] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #346

[104] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #202

[105] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #145

[106] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #518

[107] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #175

[108] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #145

[108] Government of Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police. (2019, November 5). Evaluation of the RCMP’s biology casework Analysis | Royal Canadian mounted Police.

[110] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #202

[111] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #518

[112] SISSA Consultation Table #08: Black and Racialized.

[113] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #518

[114] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #008

[115] The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP). (2024). Canadian framework for trauma-informed response in policing.

[116] Government of British Columbia. (2024). Victim interviews for sexual assault investigations (Section 5.4.4 in Provincial policing standards -Specialized investigations.

[117] PaceKit | FourWords Solutions. (n.d.). https://www.fourwords.ca/pacekit

[118] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #171