R v. Jordan

“I don’t think there is anything worse for a victim than to have a trial stayed.” [1]

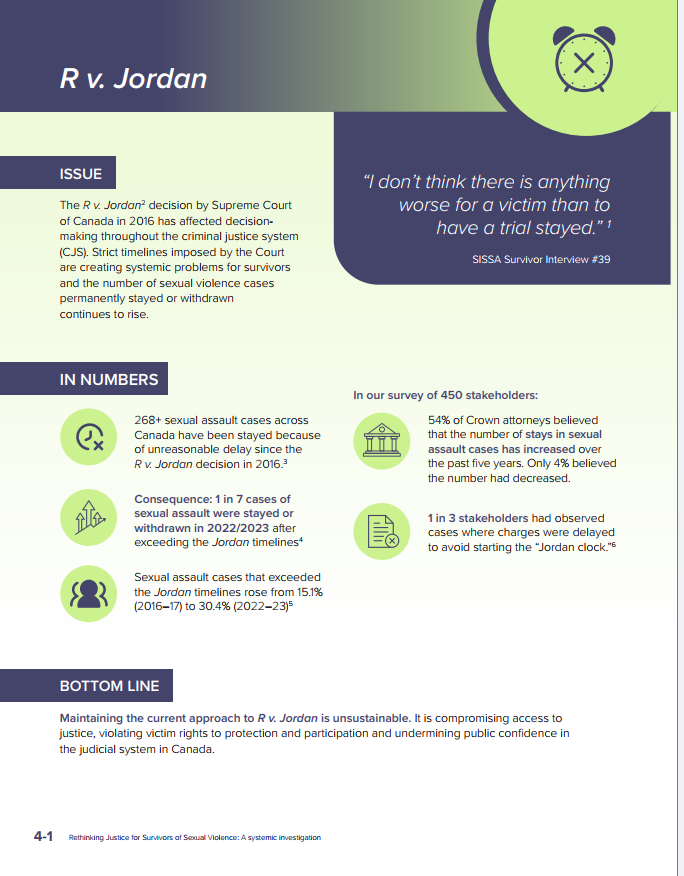

ISSUE

The R v. Jordan[2] decision by Supreme Court of Canada in 2016 has affected decision-making throughout the criminal justice system (CJS). Strict timelines imposed by the Court are creating systemic problems for survivors and the number of sexual violence cases permanently stayed or withdrawn continues to rise.

IN NUMBERS

- 268+ sexual assault cases across Canada have been stayed because of unreasonable delay since the R v. Jordan decision in 2016[3]

- 1 in 7 cases of sexual assault were stayed or withdrawn in 2022/23 after exceeding the Jordan timelines[4]

- Sexual assault cases that exceeded the Jordan timelines rose from 15.1% (2016–17) to 30.4% (2022–23)[5]

In our survey of 450 stakeholders:

- 54% of Crown attorneys believed that the number of stays in sexual assault cases has increased over the past five years. Only 4% believed the number had decreased

- 1 in 3 stakeholders had observed cases where charges were delayed to avoid starting the “Jordan clock”[6]

KEY IDEAS

- Sexual offences are being stayed or withdrawn

- R v. Jordan is reshaping decision-making across the CJS

- Stays are wasting scarce resources from governments, community groups, and survivors

- Survivors also have Charter rights

- Stays of sexual assault charges delegitimize the CJS

- Stays are compounding survivor trauma and leave some survivors at further risk of violence

BOTTOM LINE

Maintaining the current approach to R v. Jordan is unsustainable. It is compromising access to justice, violating victim rights to protection and participation, and undermining public confidence in the judicial system in Canada.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The federal government should amend the Criminal Code to

2.1 Guide judicial discretion in delay motions: Set out the following criteria to be considered by the Court in a Jordan motion (a motion to stay the charges for a lack of timely prosecution):

a) Nature and gravity of the alleged charges

b) Length of the delay

c) Complexity of the case

d) Vulnerability of the victims

e) Actions of defence

f) Actions of prosecution

g) Society's interest in encouraging the reporting of offences and the participation of victims and witnesses

h) Prejudice to the victims' Charter rights

i) Exceptional circumstances

j) Other factors including local conditions

2.2 Set consequences for defence delay: Provide that Crown can show that multiple contested procedural applications will count as defence delay if the applications have been found to be brought without adequate notice, frivolous, without basis, involve unnecessary argumentation, or show a failure to prepare.

2.3 Remedy for excessive prosecution delay: Where the Court finds there has been excessive delay in the prosecution of a case, upon conviction, these charges could receive a sentencing credit for days past the Jordan timelines, preserving judicial discretion to grant stays of charges for egregious or exceptional cases.

2.4 Ensure victims are informed of Jordan applications: When a Jordan application is filed under s. 11(b) of the Charter, the victim must be notified.

2.5 Protect victim safety in remedy decisions: Where a Court finds that there has been excessive delay and orders a stay, and where the charge relates to a violent offence, the Court must consider the victim’s safety concerns when releasing the accused.

Our investigation

Background

In R v. Jordan,[7] the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) created a framework to assess delays in prosecutions of a criminal charge. This is important because excessive delay is a violation of an accused’s 11(b) Charter right to be tried within a reasonable time. Later decisions applied the Jordan framework to other parts of the justice system, such as the youth criminal justice system.

Jordan established the current framework for assessing whether a delay is unreasonable by setting numerical ceilings beyond which delay is presumptively unreasonable:

- 18 months for cases going to trial in provincial court.

- 30 months for cases going to trial in superior court with or without a preliminary inquiry.[8]

These Jordan mandated timelines apply to all offences regardless of the seriousness of the charge.[9] Delays that are caused by the defence or are accepted by the defence do not count toward the numerical limit. Delays caused by the Crown or the Court count toward the numerical limit. The defence can ask the Court to stay the charges if the limit is reached or if there is no reasonable prospect that the prosecution can be completed.[10] The Crown can defeat this motion by showing that there were exceptional circumstances leading to the delay.[11]

The Jordan decision was a landmark moment for the Canadian justice system because the Jordan framework created clear numerical values that everyone in the CJS, regardless of jurisdiction, would have to follow. It gave certainty to prosecutors, defence, court personnel, the victim, witnesses, the public and accused about the probable length of a prosecution. The decision also gave victims and witnesses some certainty about a range of time during which they would be interacting with the CJS.

Most sexual assault prosecutions are conducted by provincial prosecutors, in provincial courtrooms supported by provincial employees. However, the federal government is responsible for developing the criminal law. There is a clear role for the federal government to solve the ‘Jordan problem’.

What’s a stay?

“Charges are “stayed” when a judge or a Crown decides that it would be bad for the justice system for the case to continue. This means the issue of guilt or innocence is never determined.

Stays can be granted when the state has acted unfairly, including a failure to bring the case to trial in a timely manner. A judicial stay brings the case to an end.

A different type of “stay” is done by the Crown. A Crown stay puts the case on hold. The Crown can bring the charges back before the court within 1 year of the date the charges were stayed. After a year has passed, the Crown cannot bring the stayed charges back before the court.”

Definition of “stay”, Steps to Justice, Community Legal Education Ontario. Accessed August 1, 2025.

What we heard

There is widespread concern in Canada about the increasing number of cases involving intimate partner violence and sexual violence that are being stayed due to the Jordan framework and the disproportionate impact this has for women’s safety. This was a significant theme in our interviews, consultation tables, surveys, written submissions, caselaw review, and media analysis.

Stays related to Jordan are not evenly distributed across Canada and some regions of the country rarely see stays. The Jordan framework has been positive for some jurisdictions where most criminal prosecutions are not delayed beyond the Jordan timelines. Other jurisdictions continue to see significant numbers of stays. Alberta is the only jurisdiction that proactively discloses the number of stays due to Jordan applications.[12]

In 2017, only one year after R v. Jordan, the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee (LCJC) wrote:

“Recent court decisions that have entered stays of proceedings in cases involving murder charges (see R v. Picard, 2016 ONSC 7061 and R v. Thanabalasingham, 2017 QCCS 1271) and child sexual assault charges (see R v. Williamson, 2016 SCC 28) shock the conscience of the community and bring the administration of justice into disrepute in Canada.”[13]

More sexual offences are being stayed

Things have gotten worse since the LCJC Senate Committee released their report. More cases of sexual violence and other cases of violent crime are being stayed, and media stories on court stays in egregious violent cases are becoming more frequent.

In a 2024 opinion piece in the Globe and Mail, Robyn Urback comments on two cases of long-term sexual violence against children that were stayed and echoes the sentiment of the Senate Committee. She says that in each case, “A rather arbitrary number meant that justice for the victim was forfeited for the rights of the accused… Canadians cannot, and will not, maintain faith in a justice system that so patently denies justice to victims of crime.”[14]

Many tests in the Criminal Code and criminal cases include this phrase “is this action or decision in the proper administration of justice.” 1

The CVBR indicates that consideration of the rights of victims of crime is in the interest of the proper administration of justice.2

1 Criminal Code, section 276(2)(d), 278.92(2)(b); Criminal Code, section 486(1), 486.1(1), 486.5(1); Criminal Code, section 537(1)(h); Criminal Code, section 715.1 and 715.2

2 Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, preamble.

The numbers of stays are increasing

An investigative report by CBC in 2025 found more than 268 criminal cases involving sexual violence across Canada were stayed since 2016 because of R v. Jordan.[15] Journalists Ireton and Oulette submitted access to information requests to all 13 provinces and territories and discovered a patchwork of reporting frameworks with no cohesive federal data on Jordan applications in court. Advocates working with survivors of sexual violence suspect issues with tracking hide the magnitude of the issue.

- Angela Marie MacDougall, Executive Director of Vancouver’s Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS), said the number seemed low.[16] Her organization has been tracking media reports and researching the impact of the Jordan framework on survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) since 2018.[17] On January 18, 2022, the BWSS wrote an open letter to former federal Justice Minister David Lametti about the harmful impacts of the Jordan framework following a review of 140 cases of Jordan applications in cases of GBV from 2016 to 2020.[18]

A 2024 CBC article reported that most criminal cases in Ontario (56% in 2022–23) now end with charges being withdrawn, stayed, dismissed, or discharged before proceeding to trial.[19] They found that 580 criminal cases in Ontario were stayed for unreasonable delay under the Jordan framework from 2016 to the end of 2023, including 145 cases of sexual assault, with 59 sexual assault cases stayed because of delay in 2023 alone.

Our analysis of publicly available data from the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) suggests that these numbers underestimate the magnitude of the problem because:

- many cases that are stayed or withdrawn close to or after exceeding the Jordan limit never proceed to a Jordan application hearing and would not appear in provincial or territorial databases that track Jordan-related stays.

- the ICCS compiles administrative court data from all provinces and territories in Canada, except for Superior Court data from Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.[20]

Other media reporting in Ontario has highlighted significant increases in the use of stays, suggesting that data in the ICCS may underestimate the impact on sexual assault cases.

From 2016–17 to 2022–23, the percentage of sexual assault cases that exceeded the Jordan limit across Canada rose from 15.1% to 30.4%.[21] This was significantly higher than the average for cases of violent crime.[22] (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

In 2022–23, nearly 1 in 3 sexual assault cases in adult courts (30.4%) exceeded the Jordan limit. Among these cases, 47.3% were stayed or withdrawn due to the limit.[23] Given that sexual assault cases in adult court were already the most likely to be past the Jordan limit, this means that 14.4% of all sexual assault cases in adult courts were stayed or withdrawn, representing 1 in 7 cases of sexual assault in adult courts in Canada, or roughly 500 cases.[24] In 2022–23, sexual assault offences in adult courts were the most likely to be stayed or withdrawn after exceeding the Jordan limit. (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Why are stays increasing?

Through our consultations, we heard about multiple sources of delay:

- Delayed analysis of SAEK[25]

- Increased numbers of elections for jury trials in some regions[26]

- Limited judges available and the ongoing need for judicial appointments[27]

- Lack of courthouse space and staff[28]

- Inefficient administration in scheduling hearings[29]

- Accused changing lawyers[30]

- Changes to judges or Crowns[31]

- The use of pre-trial motions as a tactic to cause delay[32]

- Contested motions on formerly uncontested issues, such testimonial aids[33]

- Pre-trial and mid-trial applications under ss. 276, 278.92 and 278.1 of the Criminal Code[34]

- Human trafficking being excluded from s. 276, requiring additional arguments and Court time during motions[35]

- Larger volume of electronic records, text messages, and video footage[36]

- Limited resources available for Crowns to argue section 11(b) motions[37]

- Strategic use of mid-trial motions for private records[38]

- Lengthy cross-examinations[39]

- Survivors requiring medical attention for their injuries[40]

Stakeholders also acknowledged the role the COVID-19 pandemic played in creating delays and increasing the risk of serious cases not being heard or resulting in a stay after consideration of evidence.[41] On the other hand, one stakeholder said that continued emphasis on COVID-19 is misplaced and that Crown’s offices have already resolved cases that were part of the backlog.[42]

Other countries are also struggling with the need for timely prosecutions.

A 2025 report from the Victims’ Commissioner for England and Wales warns that Crown-court delay is “actively harming victims,” with almost 48% of listed trials adjourned at least once and some postponed five times or more.[43]

UK comparative insight

In 2022, England and Wales amended their criminal law to allow pre-recorded testimony in all adult rape and serious sexual assault cases to ease survivor participation.[44]

A 2024 study reported that pre-recorded testimony cases resulted in lower conviction rates, a lower likelihood of guilty pleas, and longer delays for trials.[45] Conviction rates dropped to 41% for cases with pre-recorded evidence vs 69% for cases with live evidence.

Commentators attributed the change to courts prioritizing trials with live witnesses waiting to be cross-examined. The lack of courtrooms and prosecutors were also reasons for increased delays.

Promising Practice: New Zealand’s Timely Access Protocol

In June 2024, the Chief District Court Judge of New Zealand issued a Timely Access to Justice Protocol. This Protocol sets a public standard that 90% of criminal cases must be resolved inside category-based time limits, with performance reported quarterly.[46]

The Protocol has three categories of cases based on the complexity and seriousness of the case, with corresponding time limits. The time limits range from 6 months for the least complex to 15 months for the most complex. The Protocol recognizes that, even within these timeframes, some cases will take longer. The Protocol also gives the system until 2027 to reach this target.

“The standard is aspirational and an important next step in our efforts to enhance timely justice.”

Chief District Court Judge of New Zealand

R v. Jordan is reshaping decision-making across the criminal justice system

It became clear in our investigation that R v. Jordan affects decisions across the CJS and that stays are only one component. Efforts to avoid judicial stays have sparked innovation and investment in strategies to improve efficiency but have also led to unintended consequences that cause further delays or increase risks to public safety.

Pre-charge delay. Laying or approving charges is occasionally delayed to avoid starting the “Jordan clock.” We heard that, in some instances, there is enough evidence to make an arrest, but police or Crown want to have the whole case lined up to streamline prosecution and avoid delays.

Safety concerns. A senior prosecutor and a senior police leader mentioned that this fails to protect survivors, leaving them in situations that can compromise their safety and increase the risk of further violence or femicide.[47]

Nearly 2 out of 5 stakeholders in legal professions had observed pre-charge delay, including:

- 38% of police

- 45% of defence attorneys

- 36% of Crown attorneys

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

One proposal to moderate the Jordan framework

In 2024, Bill C-392 proposed codifying the Jordan framework and using the notwithstanding clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to exempt primary designated offences (such as sexual assault) from the Jordan framework. This Private Member’s Bill was not debated in the House of Commons.

Entering a plea. Stakeholders informed us that R v. Jordan has caused more accused to delay submitting a plea or accepting a plea deal while they wait on the “Jordan clock.” They said that there has been an increase in the number of cases in which court preparations with a victim are completed and the hearing is cancelled at the last minute.[48]

- Impact on services. They indicated this is a significant expense for victim services and places additional stress on victims.[49]

Pre-trial motions. We heard that R v. Jordan has incentivized the use of allowable motions by defence, particularly in cases of sexual violence.

- Strategic delays. Stakeholders described how multiple pre-trial motions are used to prolong proceedings and wear down complainants.[50]

- Misuse of Jordan. A Crown said that defence counsel use Jordan as a “sword” rather than the “shield” it was intended to be to protect the Charter rights of the accused.[51]

- Manipulation of protections available to survivors. Defence counsel are incentivized to apply for third-party records, bring applications to adduce sexual history evidence of the complainant, raise objections to the use of testimonial aids, bring applications to adduce records relating to the complainant, and conduct lengthy cross-examinations. There can be legitimate reasons for defence to take those actions, so it becomes difficult to discern when the practices may be exploitive.

Victim participation. We heard concerns that efforts to rapidly clear post-COVID case backlogs have negatively impacted victim participation and rights.

- Limited input. Plea resolutions frequently occur around the time of bail hearings, providing minimal or no opportunity for victims to submit a victim impact statement.

- Resource strain. Rural victim services are particularly strained, lacking sufficient resources to adequately support survivors when cases are rushed.

- Survivors with complex needs may be rushed to testify unprepared. A court support worker shared a case where a survivor, who had suffered a traumatic brain injury, was rushed into Court proceedings with no prior contact from the Crown.

Plea deals. We heard that there is no incentive for the accused to accept a plea deal early in the process because of the possibility of charges being stayed under Jordan.

- Trade-offs. Crown attorneys may accept less favourable plea deals to avoid stays.[52]

- Resource pressures. We heard that stays in the Yukon were rare until funding reduced the available number of prosecutors, leading to rapid plea bargaining to avoid stays.[53]

Discontinuations. When time is running out and a hearing is adjourned, the Crown may decide that the reasonable prospect of conviction has evaporated and may stay or withdraw the charges.

- Strategic withdrawals. Two stakeholders believed that the Crown was strategically withdrawing charges out of fear of potentially breaching Jordan[54] A former Crown noted for us that these withdrawals – perhaps due to lack of court resources - are their responsibility as Crowns.

Jury Trials. We heard that accused persons increasingly elect jury trials,[55] especially in those sexual assault cases which are also eligible for preliminary inquiries. Defence counsel recognize the complexity that jury trials create for meeting the Jordan timelines. They also recognize that judges have training on sexual assault.

- Strategic election. Defence counsel prefer jury trials because they take longer to administer and jurors are more vulnerable to myths and stereotypes about sexual assault.[56]

- Trial outcomes. Some counsel believe that convictions are harder to obtain in jury trials, and jury trials are more likely than judge-alone trials to result in mistrials.[57]

- Reform suggestion. The Charter grants the right to select a jury trial for offences with a maximum punishment of 5 years in prison or longer, but most sentences for sexual offences do not exceed 5 years. For example, the maximum sentences for sexual offences range from 10 years to life imprisonment; however, the median time in custody for sexual assault (level 1, 2, and 3) from 2015-2019 was less than 2 years.

| Sexual offence | Maximum Sentence | Median custody sentence (2015-2019)58 |

|---|---|---|

| (Level 1) Sexual assault | 10 years (if victim is 16 or older) 14 years (if victim is under 16) |

Adult victim (18+): 180 days Youth victim (12 to 17): 270 days Child victim (0-11): 365 days |

(Level 2) Sexual assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm

|

14 years | 407 days (less than 1.5 yrs) |

(Level 3) Aggravated sexual assault

|

Life imprisonment | 678 days (less than 2 years) |

- Some Crown counsel suggested lowering maximum sentences to remove the right to a jury trial and improve efficiency, or to develop a Charter compliant process to proceed with judge-alone trials where Crown and defence formally agree not to seek a sentence of 5 years or longer.[59]

Rushing highly consequential decisions. Stakeholders expressed concerns that serious sexual assault cases are increasingly rushed through the judicial process, impacting case quality and outcomes.[60]

- Resource strain. Judges lack sufficient time to consider pre-trial applications when they are scheduled to be heard immediately prior to trial

- Courtroom availability. Limited availability of courtrooms affects the speed at which cases can be heard and decided. This is particularly acute for courtrooms with CCTV or other witness accommodations

- Complex cases. Cases are becoming longer and more complex, with little time to prepare with survivors, yet resources for experienced counsel and proper mentorship are diminishing

We heard from a Crown:

“[Sexual assault] proceedings are the most drawn out of prosecutions. Application dates add significant time to estimates and those dates need to be spread out to give a judge meaningful time to consider the applications. Because the charges are serious, the accused is given significant time to retain counsel, and that delay is not deducted from the 18-month ceiling. The trials are getting longer and the cross-examinations are rarely curtailed. Trials are being stacked and Crowns with little experience are being given these cases with little mentorship or time to understand this area of law, meet with the survivor, and really prepare the case. The cases are complex and resources continue to dwindle.”[61]

Stays are resulting in inefficient use of resources from governments, community groups and survivors

When cases are stayed after significant investments of time, money, and emotional energy, the result is a complete loss of value for many people. Survivors are left without resolution. There has been no adjudication of the allegations. Community supports are wasted or undercut. Public systems absorb costs without achieving any outcomes. R v. Jordan has made this waste more frequent, visible, and costly.

Public and community resources lost

A single case that is stayed under the Jordan framework negatively affects government and community investments, including the costs of:

- Police investigations and forensic analysis of a sexual assault evidence kit

- Legal aid for the accused

- Independent legal advice sought by the complainant

- Legal representation for the complainant for sexual history and private records applications

- Crown prosecutors and staff time on case review and preparation

- Judges, court staff, and administrative time

- Physical courtroom infrastructure

- Victim Witness Assistance services

- Testimonial aids (e.g., therapy dog handlers)

- Services from Child and Youth Advocacy Centres and sexual assault centres

These resources are funded by government budgets, grants, and donations to community organizations. When cases are stayed due to delays, it is a significant waste of resources that could be better invested to improve access to justice. The growing number of stays under R v. Jordan is wasted dollars – from public and private sources.[62]

Survivors’ personal costs

Survivors are financially affected by the justice process. These are not planned or voluntary expenses, no one budgets to be a victim of crime. Survivors absorb the costs of participation, often in moments of crisis. When charges are stayed, this spending is wasted.

Time and emotional labour:

- Time off work, using paid vacation days or unpaid leave.

- Countless hours researching the legal system without access to legal services.

- Cancelled plans and other personal disruptions.

- Therapy or counselling costs for the trauma and stress of being in a courtroom

- Childcare or pet care expenses.

- Courtroom attendance costs, such as parking, lunches, transit.

Out-of-pocket expenses:

- Transportation and accommodations (particularly in rural or remote communities).

- Medical costs that aren’t covered, including dentistry, chiropractic care, psychotherapy, and physiotherapy.

Over the past year, many survivors have emphasized the significant toll this has taken on them and their children.[63]

National economic impact

In 2014, the Department of Justice estimated that crime in Canada cost survivors $13.99 billion in direct, tangible losses, including the kinds of expenses described above.[64] Adjusted for inflation in 2024, this could be as high as $20.85 billion,[65] without accounting for increases in crime rates, population increases, and the crime severity index from 2014 to 2024.[66]

The Supreme Court of Canada’s guidance on criminal trial delays

Jordan built on several seminal SCC cases on delay: R v. Morin (1992), R v. Askov (1990) and others. These cases lamented the problem of delays in the CJS and created various qualitative tests for determining unreasonable delay.

- In Jordan, the SCC concluded that the Morin framework was unduly complex and led to micro-counting and endless post-event rationalizations. The Jordan framework, in turn, has been criticized as “failing everyone.”[67]

- Across Jordan, Morin and Askov, the SCC consistently highlighted the societal interest in reducing delays in the CJS.

“Victims, too, have a special interest in having criminal trials take place within a reasonable time, and all members of the community are entitled to see that the justice system works fairly, efficiently and with reasonable dispatch. The failure of the justice system to do so inevitably leads to community frustration with the judicial system and eventually to a feeling of contempt for court procedures.”[68]

Later Supreme Court decisions applying the Jordan framework in cases of violent crime and young offenders have drawn on similar logic. In R v. J.F., the Court echoed that timely trials

- “encourage better participation by victims and witness.”

- “minimize worry and frustration.”

- “allow them to move on with their lives more quickly.”

- “help to maintain public confidence in the administration of justice.”[69]

The SCC observed that “Prolonged delay also causes prejudice to victims, witnesses and the justice system as a whole.” In R v. Thanabalasingham, a case involving femicide of an intimate partner, the Court upheld a stay of proceedings following a lengthy delay and identified that the s.11(b) Charter right benefits accused persons, victims, and society alike.[70]

Victims of crime have Charter rights

Victim concerns in criminal justice proceedings are sometimes dismissed because accused persons have specific rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This perspective diminishes Parliament’s direction to recognize that victims of crime also have Charter rights. Consider these examples:

Bill C-46 An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (production of records in sexual offence proceedings)

WHEREAS the Parliament of Canada recognizes that violence has a particularly disadvantageous impact on the equal participation of women and children in society and on the rights of women and children to security of the person, privacy and equal benefit of the law as guaranteed by sections 7, 8, 15 and 28 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

WHEREAS the Parliament of Canada intends to promote and help to ensure the full protection of the rights guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms for all, including those who are accused of, and those who are or may be victims of, sexual violence or abuse

WHEREAS the rights guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms are guaranteed equally to all and, in the event of a conflict, those rights are to be accommodated and reconciled to the greatest extent possible

Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR)

WHEREAS victims of crime have rights that are guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

WHEREAS consideration of the rights of victims of crime is in the interest of the proper administration of justice

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized the Charter rights of victims of crime:

- R v. Seaboyer [1991] 2 SCR 577

- R v. O’Connor, 1995 CanLII 51 (SCC)

- R v. J.Z.S., 2008 BCCA 401, appeal dismissed 2010 SCC 1

- R v. Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC)

- R v. Osolin, [1993] 4 SCR 595

- R v. Wyatt 1997 CanLII 12488 (BCCA)

- R v. L. (D.O.), 1993 CanLII 46 (SCC)

- R v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72 (CanLII)

- (L.L.) v. B. (A.), 1995 CanLII 52 (SCC)

- R v. Mills 1999 CanLII 637 (SCC)

- R v. Brown, 2022 SCC 18

An accused person's right to make full answer and defence in our system, while broad, is not absolute. “Section 7 of the Charter entitles an accused to a fair hearing but not always to the most favourable procedures that could possibly be imagined.”[71]

Given that sexual assault is a violation of a victim’s human rights, their rights should not be given less consideration than the accused’s 11(b) fair trial rights. In our view, the victim’s Charter rights can be engaged:

- when the procedures around reporting of sexual assault question victims about their sexual history (equality rights)

- when requests for private records affect women (who are more often victims of sexual assault) more than men (equality rights)

- when requests for private records have a disproportionate impact on 2SLGBTQI+ people

- when requests for private records have a disproportionate impact on vulnerable people and Indigenous people who are more likely to have institutional records

- when the accused uses the criminal law to access therapeutic records of a survivor (unreasonable search and seizure)[72]

- when the effects of the private records regime increase risks to a survivor’s health (life and security of person rights)

- when the defence seeks to adduce evidence about the complainant’s sexual history or to adduce private records relating to the complainant

Where an individual’s security or equality interests are at risk, they have a right to meaningful participation.[73]

“Be honest with victims about the state of the criminal justice system. How many cases get stayed due to delays? And how often are charges dropped by the Crown? And how many cases actually result in conviction? If the criminal justice system does not get a lot more funding so that cases aren't routinely thrown out, you shouldn't put survivors through the trauma of reporting.”

Survivor Survey; Response #275.

In R v. Jordan, the SCC made only 11 references to complainants or victims of crime in a decision of 87 pages. The analysis focuses on how timely trials can minimize disruption and suffering that prevent victims from moving forward with their lives. However, R v. Jordan does not include an analysis of the relevant Charter rights of victims of crime or provide any balancing of the accused’s right to a fair trial with the rights of victims.

Survivors of sexual assault have had their bodily integrity violated in the assault. Yet their voice is often silenced and their body turned into an object of evidence.

- From a victim’s perspective, it is a stunning realization that the violation of a survivor’s physical autonomy (human right to security of the person) is a fact to be proven, discussed and labelled, while the accused’s rights (right to a fair trial among others) are repeatedly affirmed by numerous criminal justice professionals and procedures.

- Survivors often describe the criminal justice process as “dehumanizing them into exhibits of evidence, analysing their culpability for the violence done onto them”.[74]

The Jordan framework, combined with complex evidentiary motions, systematically forces survivors to choose between access to their rights to life and security of the person versus the case being dropped.

“These (sexual assault) trials are often much more complicated than the average trial, which means they can take longer to get through the system and are therefore more at risk of being stayed. Where a complainant has to choose between exercising their statutory right to retain counsel and challenge the admissibility of records pursuant to the regime set out in the Code and risk the charges being stayed based on the concomitant delay, or surrendering those privacy rights to ensure the case gets to a verdict, justice is impaired.” [75]

Many survivors are angry that reporting exposes them to the harms of the CJS without warning them about the possibility of a serious case being dismissed after they are interviewed, have their records subpoenaed, testified in a public forum, and been cross-examined about intimate parts of their life.

- One survivor was specifically advised by a Crown that a stay would never happen in the prosecution of their assault because of the violent aggravated nature of the offence and the strength of the evidence, but the matter was stayed the following year after a section 11(b)[76]

“I was told it’s best to move on with your life. This is not ok.” [77]

We urge the federal government, in responding to the Jordan decision, to ensure that victims’ Charter rights are considered. This includes in any analysis done under section 1.

- The evidence provided to us indicates that there is no proportionality between the objectives of the Jordan framework and its effect on survivors of crime.

- We also believe that a stay that results from the Jordan framework is not a minimal impairment of the survivors’ Charter Survivors are not currently considered in the Jordan framework, at all.

- The SCC has noted that “a stay has been recognized as the most extreme remedy available for a Charter breach, and one that is to be reserved for exceptional cases.”[78] The routine ordering of stays for the most serious sexual violence offences is neither proportional nor minimal.

Case Study: Mother Jailed, Charges Against Abuser Stayed[79]

The survivor and her sister were sexually abused by her stepfather for many years as children. Once the police were involved, the stepfather was charged with sexual interference, and her mother was charged with sexual interference by complicity since she knew about the abuse.[80]

Her mother pled guilty to the charges and served 3.5 years in prison. Her stepfather pled not guilty, and despite admitting to sexual assault in Court, his charges were stayed because of delays that extended the case for nearly seven years.

The trial judge, in granting the stay, noted that the stepfather had been the cause of some of the delays as he was “talkative to a degree never seen by the Court” and made little effort to have the case completed.

The survivor sued the Attorney General and Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions (DPCP) in Quebec for $450,000 for the psychological harms to her in the stay of the prosecution.[81] Justice Prémont ruled that the prosecutors had made errors but still benefited from immunity. She reminded the victim that prosecutors represent society, and not the victim, and that a victim’s role is limited to being a witness in a criminal trial. The Judge estimated that if the prosecutors did not have immunity, the DPCP would have to pay $25,000 in damages.

Costs were ordered against the survivor.[82]

Litigating the right to life, liberty, and security of the person

EXAMPLE 1: Fourteen survivors of sexual violence and intimate partner violence have filed a lawsuit against the Government of Canada claiming that R v. Jordan violates their s. 7 Charter rights to life, liberty, and security of the person and that the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights fails to provide effective remedies.[83] At the time of this report, this case has not been adjudicated.

Each survivor’s case includes evidence that threats to their lives, the lives of their children, or other safety concerns were exacerbated when the criminal charges were stayed under 11(b):

- The survivors state that the impunity of a stay emboldened their abusers and the justice system’s failure to provide protection continues to place them at risk.

- The lawsuit provides specific examples of stalking, violence, and child abduction after charges were stayed.

- Some of the plaintiffs are still in danger, and one mother’s child is still missing.

EXAMPLE 2: The OFOVC has received several formal complaints from survivors whose cases have been stayed. We have also noted ongoing safety threats from serious violent crime where the perpetrator would generally be incarcerated. In one instance, we were required to report a child in need of protection.

EXAMPLE 3: In two Québec cases,[84] the victim’s lawyers have argued that the Charter interests of survivors of crime were violated in the Crown’s decision to stay charges or lack of diligent case management. Both cases have failed.

Stays of sexual assault charges delegitimize the criminal justice system

We heard repeatedly that stays granted under R v. Jordan undermine public confidence in the justice system. The Standing Senate Committee on LCJC said the stay in R v. Thanabalasingham – and similar decisions involving homicides and sexual assault against children – “shock the conscience of the community and bring the administration of justice into disrepute in Canada.”[85]

- Stakeholders emphasized to us that terminating sexual assault prosecutions for reasons unrelated to the assault, especially after a survivor has testified, undermines the legitimacy of the legal process and signals that procedural timelines are prioritized over substantive justice.[86]

- Survivors who endure months or years of delays, undergo cross-examination, and navigate retraumatizing proceedings are often devastated to learn that charges have been stayed due to delay. A victim service worker described a sexual assault case where a young survivor who had already testified was informed of a stay weeks before a new trial date. The worker told us that the “sobs and anger were intense” when the decision about the stay was shared.[87]

We heard that the Jordan framework is viewed as arbitrary and draconian, particularly in sexual assault and homicide cases.[88] One stakeholder noted:

“These survivors are retraumatized during the trial and then ultimately feel like it was for no reason because a judgment on the matter can't even be made. It's abhorrent that cases can be ‘thrown out’ due to time delay that simply cannot be resolved because of the sheer volume of files and difficulty coordinating schedules and available court time.” [89]

The message to survivors is clear: procedural delays can override their access to justice, no matter the harm they have endured or the strength of the evidence. For many, it confirms the broader perception that sexual assault is being decriminalized in Canada, not by statute, but by attrition and delay.

Growing liability and public confidence

The number of victims whose experiences of violent crime have been dismissed by the courts is rising. This increases the longer-term possibility of a class action lawsuit, particularly where survivors have participated in the justice process and incurred costs, been hospitalized for mental health, or lost their employment, housing, savings, or education.[90]

There is growing organization at the community and international level to challenge R v. Jordan. It is inevitable that the growing disrepute will extend internationally, undermining Canada’s commitments to gender equality and the rule of law. The Supreme Court observed in R v. Jordan:

“Extended delays undermine public confidence in the system. And public confidence is essential to the survival of the system itself, as ‘a fair and balanced criminal justice system simply cannot exist without the support of the community’.”[91]

At the community level, Vancouver Rape Relief’s 2024 CEDAW submission calls Jordan-related stays “a violation of Canada’s duty to ensure access to justice for women” and asks the UN committee to press Canada to prioritize sexual assault trials.[92]

Public confidence is eroding quickly as cases are profiled repeatedly in the media and shared by advocates.[93]

R v. Jordan violates the good faith and confidence survivors place in the criminal justice system to protect them and others. It exposes survivors to significant risks to their mental health, resources, and relationships through participation in the criminal justice system, then undercuts the process once survivors have already paid the costs of participation.

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve timely justice too.

Justice delayed is often justice denied.

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Interview #39

[2] R v. Jordan (2016) SCC 27 (CanLII).

[3] Ireton, J., & Ouellet, V. (February 3, 2025). Hundreds of stayed sexual assault cases send chilling message to victims, advocates warn. CBC News.

[4] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 35-10-0173-01 Key indicator results and absolute change for annual data, adult criminal court and youth court. For specific filters on sexual assault, see Sexual Assault Specific Filters. The statistics cover criminal proceedings against the accused that were stopped by the court after exceeding Jordan limits including stays under a Jordan application or without an application, charges being withdrawn, dismissed, or discharged at preliminary inquiry, or referred to alternative and extrajudicial measures including restorative justice.

[5] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 35-10-0173-01 Key indicator results and absolute change for annual data, adult criminal court and youth court. For specific filters on sexual assault, see Sexual Assault Specific Filters

[6] SISSA Stakeholder Survey results, question 16: 36.16% of stakeholders believe that the number of stays in sexual assault cases has increased over the past 5 years.

[7] R v. Jordan, 2016 SCC 27 (CanLII)

[8] R v. Jordan, 2016 SCC 27 (CanLII), [2016] 1 SCR 631, at para 49.

[9] Complexity of a case can be used to show that exceptional circumstances lead to a delay. Complexity refers to complex legal issues, extensive police investigation, complex preparations, multiple co-accused, etc. The Crown has the burden to show that it took reasonable steps to avoid and address problems relative to complexity.

[10] This is not an exhaustive list of the reasons that a defence can seek a stay under 11(b).

[11] This is not an exhaustive list of the reasons that a Crown can defeat a 11b motion.

[12] Everson, K. (2024, June 1). Long delays and collapsed cases are eroding faith in the justice system, lawyers warn. CBC.

[13] Runicman, B., The Honourable & Baker, G., The Honourable. (2017) Delaying Justice is Denying Justice: An Urgent Need to Address Lengthy Court Delays in Canada (Final Report). Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs. [Emphasis added]

[14] Urback, R (2024, November 14). Opinion: What kind of functional country lets alleged criminals, by the hundreds, walk free? Canada, apprently. The Globe and Mail.

[15] Ireton, J., & Ouellet, V. (2025, February 3). Hundreds of stayed sexual assault cases send chilling message to victims, advocates warn. CBC news.

[16] Ireton, J., & Ouellet, V. (2025, February 3). Hundreds of stayed sexual assault cases send chilling message to victims, advocates warn. CBC News.

[17] Battered Women’s Support Services. (2022, March 3). BWSS expresses concerns about Jordan framework to Federal Govt. Battered Women’s Support Services

[18] MacDougall, A. M. (2022, January 18). Open letter to the Honourable David Lametti. RE: R v. Jordan framework and implications for GBV. Battered Women’s Support Services.

[19] Brockbank, N., & MacMillan, S. (2024, November 12). Most criminal cases in Ontario now ending before charges are tested at trial. CBC News. The article notes that there may be many reasons for stays, including diversion programs.

[20] Statistics Canada. (2024). Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS): Detailed information 2024/2025.

[21] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 35-10-0173-01 Key indicator results and absolute change for annual data, adult criminal court and youth court. For specific filters on sexual assault, see Sexual Assault Specific Filters

[22] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 35-10-0173-01 Key indicator results and absolute change for annual data, adult criminal court and youth court. For specific filters on sexual assault, see Sexual Assault Specific Filters

[23] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 35-10-0173-01 Key indicator results and absolute change for annual data, adult criminal court and youth court. For specific filters on sexual assault, see Sexual Assault Specific Filters

[24] The statistics cover criminal proceedings against the accused that were stopped by the court after exceeding Jordan limits including stays under a Jordan application or without an application, charges being withdrawn, dismissed, or discharged at preliminary inquiry, or referred to alternative and extrajudicial measures including restorative justice.

[25] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #175; SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[26] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #306

[27] SISSA Consultation Table #30: Legal and Independent Legal Advice; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[28] SISSA Consultation Table #30: Legal and Independent Legal Advice; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[29] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #61

[30] SISSA Survivor Interview #38; SISSA Consultation Table #7: Human Trafficking Crown

[31] SISSA Consultation Table #7: Human Trafficking Crown

[32] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #62

[33] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #293

[34] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #611; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #23, #50, #61, #131

[35] SISSA Consultation Table #7: Human Trafficking Crown; SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult; SISSA Stakeholder Interview #161

[36] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #17

[37] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult

[38] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #611; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #49, #60

[39] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #590, #611

[40] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #245

[41] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #21

[42] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[43] Murray, S., Welland, S., & Storry, M. (2025). Justice delayed: The impact of the Crown Court backlog on victims, victim services and the criminal justice system. Victims Commissioner.

[44] Statute Law Database. (1999, August 6). Youth Justice and criminal evidence act 1999. Legislation.gov.uk.

[45] Dugan, E., & Goodier, M. (2024, December 6). Rape trials collapse as victims abandon cases amid long court delays. The Guardian.

[46] https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/reports-publications-and-statistics/new/timely-access-to-justice-protocol-releasedDistrict Court of New Zealand. (2024, June). Timely Access to Justice, Judicial Protocol Ref #01.

[47] SISSA Consultation Table #14; SISSA Stakeholder Interview #437

[48] SISSA Consultation Table #4: Independent Sexual Assault Centres, #27: Sexual Assault Centres

[49] SISSA Consultation Table #4: Independent Sexual Assault Centres, #14: Victim Services, #30: Legal and ILA

[50] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #62

[51] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #450

[52] SISSA Consultation table #4: Independent Sexual Assault Centres, #28: Women’s NGO/Advocacy Organizations

[53] SISSA Stakeholder Survey #368, #397

[54] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[55] Stakeholder Interview #131

[56] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crowns; SISSA Focus Group #02

[57] Stakeholder surveys #21, #65, #306. [57] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #21, #65, #306

[58] Statistics Canada. (2024). Table 3: Decisions and outcomes of adult criminal court cases linked to police-reported sexual assault, by selected characteristics, Canada, 2010-2014 and 2015-2019.

[59] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown consult

[60] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown consult; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #21, #65

[61] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #451

[62] Justice Canada and WAGE are preparing updated studies on costs of the criminal justice system that could be used to estimate the tax burden of cases that proceed through investigations, prosecution, and court and are then stayed according to Jordan. These costs could be cross-referenced with actual cases stayed to determine the cost of the Jordan decision to the criminal justice system.

[63] Sexual Assault Survivor Complaints to Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime, 2024–2025.

[64] Li, T. (2023). Costs of crime in Canada, 2014. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada.

[65] $14.4 Billion ÷ 35 million (2014 population) = $411/person x 40 million (2024 population) = $16.4 billion x inflation (28.04%, Bank of Canada Inflation Calculator) = $21 billion.

[66] Statistics Canada. (2024). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2023.

[67] Kane, L. (2017, July 6). 'Failing everyone': 204 cases tossed over delays since Supreme Court's Jordan decision. CBC.

[68] R v. Askov, (1990) CanLII 45 (SCC), headnote

[69] R v. J.F. 2022 SCC 17 at para 22, 72.

[70] R v. Thanabalashingham, 2020 SCC 18, at para 9

[71] R v. Lyons, 1987 CanLII 25 (SCC), at para 362; R v. Fox, 2024 SKCA 26 (CanLII)

[72] R v. Mills, [1999] 3 SCR 668

[73] New Brunswick (Minister of Health and Community Services) v. G. (J.), 1999 CanLII 653 (SCC), at para 2

[74] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #805, SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Responses #243, 523, 805.

[75] His Majesty the King in Right of Canada v. Vrbanic & Josipovic. (2025, May 26). Factum of the Appellant (Supreme Court of Canada, File No. 41741).

[76] Survivor Interview #141.

[77] Survivor Interview #141.

[78] R v. Regan, 2002 SCC 12 (CanLII).

[79] Bergeron, Y. (2023, 12 December). Arrêt Jordan pour « l’ange Daniel » : une victime n’a droit à aucune indemnité. CBC Radio-Canada. (Available in French only)

[80] Bergeron, Y. (2017, April 12). Arrêt Jordan : un présumé agresseur libéré à Québec. CBC Radio-Canada. (Available in French only)

[81] Biron, P-B. (2023, December 12). Procès avorté de «l'Ange Daniel» par l’arrêt Jordan: la plaignante déboutée contre l’État. Le journal de Québec. (Available in French only)

[82] J.V. c. Procureure générale du Québec, 2019 QCCS 3637 (CanLII); J.V. c. Procureure générale du Québec, 2020 QCCS 2534 (CanLII).

[83] Papineau, C. (2025, April 11). “Graveyard of preventable deaths”: IPV Survivors Sue Canadian Government. CTV News.

[84] J.V. c. Procureure générale du Québec, 2019 QCCS 3637 (CanLII); J.V. c. Procureure générale du Québec, 2020 QCCS 2534 (CanLII).

[85] Runciman, B., The Honourable & Baker, G., The Honourable. (June 2017). Delaying justice is denying justice: An urgent need to address lengthy court delays in Canada (Final Report). Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

[86] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #194

[87] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[88] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #410

[89] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #282

[90] Ireton, J., & Ouellet, V. (2025, February 3). Hundreds of stayed sexual assault cases send chilling message to victims, advocates warn. CBC News.

[91] R v. Jordan 2016 SCC 27 at para 26 citing R v. Askov 1990 CanLII 45 (SCC) at p. 1221.

[92] Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter. (2024, September). Report to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women on the occasion of the Committee’s periodic review of Canada [Submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, 89th session].

[93] The graphic shows an example of R v. Jordan media tracking from Vancouver Rape Relief & Women’s Shelter. Impact of Supreme Court of Canada's “Jordan Decision” on Sexual Assault Cases: Media Roundup - Vancouver Rape Relief & Women's Shelter.