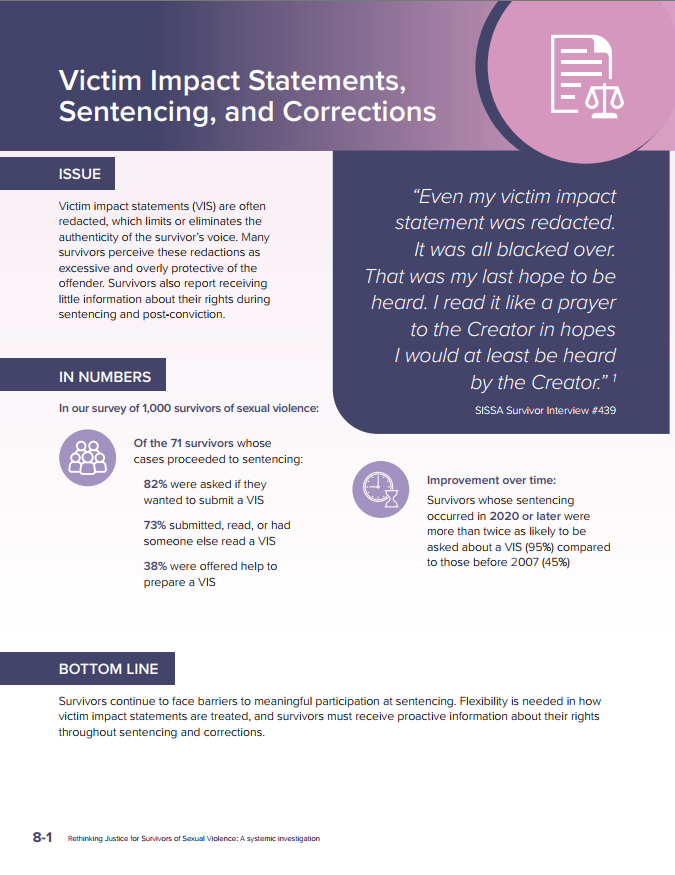

Victim Impact Statements, Sentencing and Corrections

“Even my victim impact statement was redacted. It was all blacked over. That was my last hope to be heard. I read it like a prayer to the Creator in hopes I would at least be heard by the Creator.” [1]

ISSUE

Victim impact statements (VIS) are often redacted, which limits or eliminates the authenticity of the survivor’s voice. Many survivors perceive these redactions as excessive and overly protective of the offender. Survivors also report receiving little information about their rights during sentencing and post-conviction.

IN NUMBERS

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- Of the 71 survivors whose cases proceeded to sentencing:

- 82% were asked if they wanted to submit a VIS

- 73% submitted, read, or had someone else read a VIS

- 38% were offered help to prepare a VIS

Improvement over time:

- Survivors whose sentencing occurred in 2020 or later were more than twice as likely to be asked about a VIS (95%) compared to those before 2007 (45%)

KEY IDEAS

- Redactions of victim impact statements reduce the perceived legitimacy of the criminal justice system (CJS)

- Survivors need proactive information about their rights at sentencing and post-conviction

- Victims often do not realize that an offender will be released long before their sentence ends

- The Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime lacks the authority to access information needed to resolve victim complaints

BOTTOM LINE

Survivors continue to face barriers to meaningful participation at sentencing. Flexibility is needed in how victim impact statements are treated, and survivors must receive proactive information about their rights throughout sentencing and corrections.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Victim Impact Statements (VIS)

6.1 Prevent early disclosure: The federal government should amend the Criminal Code to provide that a victim impact statement (VIS) is not given to the Crown or the defence until there is a finding of guilt, so it is not subject to disclosure and cross-examination prior to sentencing.

Federal Corrections and Parole

6.2 Allow partial summaries of victim statements: The federal government should amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) to allow victims to request that offenders in federal custody receive a partial summary of their victim impact statement, limiting details of emotional or psychological harm, while still providing full details on any conditions requested when a statement is used by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) or Parole Board of Canada (PBC) for decision-making. The victim should be provided with the summary and with the ability to remove any personal or other information that affects their safety.

6.3 Properly investigate complaints: The federal government should amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) to provide that the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime (OFOVC) shall receive, upon request, any document, recording, paper, or information relevant to a complaint made by a victim.

Background

Few sexual violence cases reach sentencing. When they do, survivors have the opportunity to submit a victim impact statement (VIS). This is often one of the only moments in the criminal justice process when a survivor can directly describe the impact of the crime in their own voice.

The opportunity to present a VIS is particularly important in cases resolved through a guilty plea or where survivors have otherwise had little involvement in the criminal justice system. In these situations, the VIS may be their only chance to describe the harm in their own words and have it formally acknowledged by the court.

At the same time, most sexual violence cases do not result in a federal sentence.

- The Correctional Service of Canada indicates that in 2022-23, 11,296 offenders were serving a federal sentence for Schedule 1 offences.[2]

- Schedule 1 includes all forms of sexual offences against adults and children, all forms of assaults, some weapons offences, and arson.

- CSC was not able to tell us how many offenders are serving a federal sentence for sexual offences.

This means many survivors never enter the correctional and parole system, and for those who do, there is limited clarity on how to remain involved or informed after sentencing.

What is a victim impact statement (VIS)?

A VIS is a statement from a survivor that is written prior to sentencing and can be presented to the Court by the victim, a friend, or the Crown. It becomes part of the evidence that the judge must consider in determining the sentence of the accused. The statement can include descriptions of emotional, physical, economic, or safety impacts of the offence. It can include photographs of the survivor, poems, or drawings.

According to the Criminal Code, a statement must not include:

- Any statement about the offence or the offender that is not relevant to the harm or loss suffered

- any unproven allegations

- any comments about any offence for which the offender was not convicted

- any complaint about any individual, other than the offender, who was involved in the investigation or prosecution of the offence

- except with the court’s approval, an opinion or recommendation about the sentence

Criminal Code of Canada, Forms 34.2 and 34.4.

Helpful clarifications about victim impact statements have been published by Justice Canada and many jurisdictions. See Victim Impact Statement.

Our Investigation

What we heard

“Why should the victim have to speak so carefully to not hurt the offender’s feelings?

Sugarcoating their response.” [3]

“Victim impact statements contribute significantly to a just sentencing process.” [4]

Of 1000 survivors who responded to our survey, 71 provided additional information about their experiences at the sentencing stage (7.1%). Fewer than half of respondents felt informed and supported during the sentencing process:

- 49% of survivors understood what would happen at sentencing

- 48% of survivors had the information they needed to attend

- 46% of survivors knew they could ask questions about anything they didn’t understand

- 27% of survivors learned new information about the offence at the sentencing hearing

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Improvements over time: When we examined these experiences by last contact with the CJS, it was clear that the use of VIS has increased over time.

- 95% of survivors in 2020 or later were asked if they wanted to submit a VIS compared to 45% of survivors prior to 2007

- 81% of survivors in 2020 or later submitted, read, or had someone else read a VIS compared to 55% prior to 2007

- 46% of survivors in 2020 or later were offered help to prepare a VIS compared to18% prior to 2007

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Prevalence of victim impact statements: Older research on victim impact statements showed a slower uptake in their use. A 2006 study estimated that VISs were presented in 8% of BC cases, 11% of Manitoba cases and 13% of Alberta.[5]

Case law review: Given the higher rates reported by survivors in our investigation and the absence of reliable national data, we conducted a simple case law review to examine judicial mention of victim impact statements in sentencing decisions. Using the Westlaw Canada database, we examined available non-appeal court sentencing decisions for sexual offences from 2014 to 2024 to identify trends (n = 3475).[6]

- Sentencing decisions for sexual offences in non-appeal courts that mentioned a VIS rose from 61% in 2014 to 69% in 2024.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Note: This includes cases where a judge commented on the absence of a VIS. Retaining only cases where the judge notes content from the VIS, we observed an increase from 52.4% in 2014 to 62.6% in 2024.

Submitting a victim impact statement can be beneficial for survivors

One study found that victims who submitted a statement were more satisfied than victims who did not.[7]

A 2021 report for Justice Canada noted multiple benefits from the victim impact statement regime:

- For many victims, the “therapeutic” purposes of the VIS are more predominant than the “instrumental” purposes (Roberts & Erez 2004) – i.e., the process itself seems to be more important than the ultimate outcome, as noted in numerous studies from various jurisdictions:

- Marshall (2014:574): “Interestingly, most victims do not seek harsher punishments, rather they seek participation in the justice system, and it is that participation that helps them in the healing process.”

- Rossi(2008:199): “[S]tudies show that victims are ‘not interested in changing sentencing outcomes,’ and they ‘do not want decision making powers.’ Rather, victims report that they only benefited from delivering victim impact statements because it provided an opportunity to be heard, to be treated with respect, to be informed and involved, to be taken seriously, to receive compensation, and to hear the offender’s admission of guilt.”

- Du Mont, Miller & White (2007): “Victims were not motivated to submit VISs to influence the outcome of the sentence; rather, they wanted to relay a message to the offender of the impact of the offence, to have their suffering acknowledged and to begin the recovery process.”

- Roberts & Erez (2004); Meredith & Paquette (2001):“Victims feel validated when their VIS is referred to by the sentencing judge, as it communicates to them that the community has recognized the harm they have suffered.” [8]

Barriers to meaningful participation at sentencing

“Nobody helped me, nobody walked me through everything. I was left to try to figure things out, and then when the VIS deadline was missed, oops, no one reminded me. Everyone was focused on making sure the criminal got all the help.” [9]

Of 1,000 survivors who responded to our survey, 71 provided additional information on their experiences with sentencing:

- 42 attended a sentencing hearing (roughly 7.7% of survivors whose cases were reported to police (n = 548))

- 82% were asked if they wanted to submit a VIS

- 73% submitted, read, or had someone else read a VIS

- 7% said that defence counsel objected to content in their VIS

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Many survivors told us they were offered the opportunity to submit a victim impact statement (VIS) but were left without support to do so.

- Just 38% of survivors who attended a sentencing hearing were offered help preparing their statement.

- Some were only informed at the last minute, sometimes the evening before the hearing, and felt unprepared, overwhelmed, or unable to participate. [10]

Victim services can provide support to prepare a victim impact statement. However, stakeholders explained that many offices are understaffed and overburdened and they may not have the capacity to help victims with their VIS if there is too short notice (for example, in a plea resolution).[11]

Why identity matters

Survivors who may need more support

Throughout our investigation, we heard that the victim impact statement process does not reflect the realities or needs of all survivors. Stakeholders shared:

- Young survivors often receive generic VIS information sheets that do not reflect their developmental stage or help them articulate long-term impacts of the crime. [12] In 2022-2023, Child and Youth Advocacy Centres (CYACs) in Canada supported 180 young survivors in preparing VIS, highlighted both the need and the benefit of specialized supports.[13]

- Survivors with intellectual disabilities may need more help writing a VIS to be able to include the messages they want.[14]

- Survivors living with mental health challenges and addictions are often not provided enough time or tailored support to complete a VIS.[15] [16]

- Survivors experiencing homelessness may also be more vulnerable to the process of VIS. We heard that survivors may be notified too late to participate and lack access to devices, internet, or local organizations that could assist them.[17]

- Newcomers may face barriers related to language, cultural norms, and discomfort with written statement. Standard French or English VIS forms may not align with their communication styles.[18]

- Indigenous survivors may find the written essay-style format of VIS and traditional courtrooms limit their ability to express the impact of the crime. We heard that in restorative approaches (such as healing circles), the impact on those harmed would be shared in a much different format.[19]

Are defence increasing their objections to victim impact statements?

In our survey, 1 in 10 survivors who submitted a VIS said that defence raised objections to content of their statement during sentencing (9.6%, 5 of 52 survivors). These objections, while not widespread in our dataset, raise important concerns about how survivors’ voices are handled in adversarial processes.

A survivor shared their experience:

“The defence cross-examined my victim impact statement to try to make it seem like I was the problem versus the family member that abused me. No one stopped him. The defence also had all my journals, as my parents took them without my consent, and they didn't tell me they had them (or the Crown) and were planning on using them for cross-examination purposes. I didn't know until after the court process was over and they released them to someone else to give to me. They used them in cross-examining my victim impact statement.” [20]

Stakeholders are divided on whether defence objections are increasing. Having heard similar concerns from interviews with court-based victim services and in the absence of formal court data to establish prevalence, we asked stakeholders for their perceptions of how frequently defence lawyers challenge VIS content over the past 5 years. Responses varied by role:

- Most stakeholders believed the prevalence of defence objections to VIS had stayed the same over the past 5 years or felt like they did not know enough to comment.

- Defence lawyers (n = 11) believed the prevalence had stayed the same (73%) or decreased (18%)

- Crown attorneys (n = 97) also believed the prevalence had stayed the same (62%) and were slightly more likely to believe the prevalence had decreased (18%) than increased (15%)

- Court-based victim services (n = 23) were the most likely to believe the prevalence had increased (30%)

These finding suggest differing perceptions across roles, particularly between service providers supporting survivors and legal professionals.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Redactions and procedural decisions reduce the perceived legitimacy of the criminal justice system

“My VIS was redacted. I never got a chance to go into a court room and explain what happened to me. It was hard to swallow and a slap in the face. I wish I had the opportunity to tell my story.” [21]

Victims' voices are being diminished

Survivors and stakeholders consistently raised concerns about how victim impact statements were redacted, often without consent, consultation, or clear justification:

- Numerous victims and victim services professionals told us that the scale of the redaction was so complete that the statement was no longer their voice[22]

- Some survivors only learned after sentencing that their VIS had been sanitized by the Crown, without their knowledge or agreement[23]

- They were left with the impression that the Crown was more concerned about protecting the sensitivities of the offender than hearing from the victim

- They had to prepare their statement so early in the criminal justice process that it felt “incomplete” when it was time to present the VIS to the Court

- They were unable to change the statement to reflect their additional or new evidence

- Allowing redactions to VIS contributes to the public’s sense of the futility and illegitimacy of the criminal justice process

Redactions are not required

In 2015, the Criminal Code was amended to give judges the explicit authority to disregard any portion of a victim impact statement they find inappropriate. Section 722(8) states:

“In considering the statement, the court shall take into account the portions of the statement that it considers relevant to the determination referred to in subsection (1) and disregard any other portion.” [24] [25]

Redaction is not necessary because the Court can “take into account the portions of the statement I consider to be relevant and to disregard the remainder.” [26]

While redaction by the Crown or victim services may be a way to manage defence applications to redact, limit, or remove victim impact statements, a VIS is often the only way the survivor can bring their evidence of impact of the offence in their own voice.

In fact, redactions may violate the victim’s rights under the CVBR to “convey their views about decisions to be by appropriate authorities in the criminal justice system that affect the victim’s rights under this Act and to have those rights considered” and “to present a victim impact statement to the appropriate authorities in the criminal justice system and to have it considered.” [27]

Case law supports this interpretation. In R v. C.C.,[28] the Court noted that judges may exclude inappropriate portions of a VIS but also emphasized that “requiring the victims to rewrite their statements would be both insensitive and unnecessary.” [29] Other Courts have used the power given in section 722(8) to disregard – without redacting – information that is not relevant or appropriate.

- “Other matters found in a victim [impact] statement, such as a sentencing recommendation, criticism of the offender, assertions as to the facts of the offences, statements directed to the offender and descriptions of other offences committed by the offender, are not properly included within a statement delivered under 722 of the Criminal Code and must be disregarded in accordance with s. 722(8) of the Criminal Code.” [30]

- “Rather than trying to judicially redact portions of certain statements, I find it to be sufficient to simply identify certain areas of concern and confirm my treatment of same.” [31]

- The Supreme Court noted that a victim impact statement “will usually provide the best evidence of the harm that the victim has suffered.” [32]

- In R v. CC,[33] the Court notes that “A Judge may choose to …. exclude inflammatory or offensive parts of victim impact statements that create the appearance of unfairness in the proceedings or reflect negatively on the integrity of the administration of justice.”

- The Court specifically notes that the approach contemplated by 722(8) “strikes an appropriate balance between the right of the offender to a fair trial and the rights of the victims to a fulsome opportunity to express the impact that his crimes have had on their lives.” [34]

In our 2024 report Worthy of Information, we recommended “Allow greater flexibility for the voices of victims to be heard:

- The guidelines for Victim Impact Statements at sentencing and Victim Statements used by the CSC and PBC should be more flexible to ensure that freedom of speech and freedom of expression of victims of crime are not unnecessarily limited.”

Victim impact statements and the CVBR

In the Nunavut case of R v. Aklok,[35] the Court discussed the CVBR obligation to provide a victim with the opportunity to present a victim impact statement.

[54] In 2015, Parliament enacted Bill C-32, the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights. The purpose of the legislation can be found in the law’s preamble, which states, in part:

Whereas crime has a harmful impact on victims and society;

Whereas victims of crime and their families deserve to be treated with courtesy, compassion and respect including respect for their dignity;

Whereas it is important that victims’ rights be considered throughout the criminal justice system;

Whereas victims of crime have rights that are guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[55] Among other things, this legislation established the right of victims of crime to participate in the sentencing process by filing, or reading aloud in court, a victim impact statement. ……

[56] Parliament also mandated an ongoing supervisory role for judges to ensure that this right is respected. Section 722(2) continues:

722 (2) As soon as feasible after a finding of guilt and in any event before imposing sentence, the court shall inquire of the prosecutor if reasonable steps have been taken to provide the victim with an opportunity to prepare a statement referred to in subsection 1. 2020 NUCJ 37 (CanLII) | R v. Aklok | CanLII

[57] However, more than five years after the Victims Bill of Rights came into effect, the Crown continues regularly to ask this Court to sentence offenders without victims having been informed of their right to be heard.

[58] As I noted above, I adjourned this case to allow the Crown to contact the victim. This Court requires prosecutors to contact victims regardless of whether the accused has entered an early guilty plea, whether the victim has a telephone, or whether the police have provided contact information for the victim. “The police and the prosecution have a statutory duty to establish a protocol ensuring that victims of crime receive early notice of their rights.” [36]

In a case of sexual abuse of a four-year-old girl by the mother and her boyfriend, the Supreme Court of Canada said:

“When possible, courts must consider the actual harm that a specific victim has experienced as a result of the offence. This consequential harm is a key determinant of the gravity of the offence. Direct evidence of actual harm is often available. In particular, victim impact statements, including those presented by parents and caregivers of the child, will usually provide the ‘best evidence’ of the harm that the victim has suffered. Prosecutors should make sure to put a sufficient evidentiary record before courts so that they can properly assess, ‘the harm caused to the child by the offender’s conduct and the life-altering consequences that can and often do flow from it.” [37]

Some survivors don’t want to keep exposing their private lives to the offender

- “It’s important but it sucks a lot to have the offender who purposefully hurt you get confirmation that they hurt you.” [38]

- “Many survivors struggle with whether they will complete a Victim Impact Statement or not. Some survivors have said that they don’t want to give their trafficker additional power by having their trafficker become aware of how their experience has hurt them .” [39]

- “It should be a closed court for vulnerable children and when the victim impact statement is read.” [40]

Many survivors do not want an offender to know the extent of the harm done. This perspective is grounded in the fact that sexual violence most often occurs between people known to each other. It is a crime of power, not a crime of passion. Submitting a VIS or a victim statement with information about how the crime has impacted them and how they feel is another slight on their privacy, or feeding future manipulation.

It is important to share the full impact with decision-makers. Some victims have indicated that they do not want to describe the ongoing harm to an offender who was motivated by sadism or racism, but they still want a court or Parole Board Members to know the ongoing effect of the offence.

- It is not necessary to describe all the graphic details to convey violent or sexual assault in what becomes a public document.

- We propose that offenders receive a summary of the information at a parole hearing. This would address the duty of procedural fairness to inform offenders of the information used in decisions about them, while allowing the survivor to retain some privacy. An example could be, “victim described ongoing psychological harms from the offence.”

- The CCRA already allows offenders to be provided with a summary of information where the information would “jeopardize the safety of any person, the security of a penitentiary or the conduct of any lawful investigation”. [41] This is in the context of a decision taken by the CSC.

Victims need proactive information about their rights after the offender receives a federal sentence

We asked survey respondents whose cases had resulted in the offender being sentenced to federal custody about their information preferences.

What we heard from survivors:

- Most wanted information but didn’t know how to access it as they have to opt in to receive updates. Among survivors whose cases led to a federal sentence (n = 26),

- 91% said they wanted to know as much as possible about corrections and parole (n = 23)

- 64% were registered to receive information with the CSC or PBC (n = 22)

- 36% were not in contact with CSC or PBC since the offender was sentenced (n = 22)

- Survivors were caught off-guard by parole hearings. Some survivors were not notified of parole hearings or told about their rights to submit a victim statement for parole. [42] Others discovered too late they had missed their opportunity to participate.[43]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Gaps in registration lead to missed safety-related information

If survivors are not registered, they miss critical updates, such as parole hearing dates, offender release dates and conditions, or geographic restrictions. If survivors have been receiving information and participating in the prosecution up until sentencing, many people assume that they would receive information about corrections and parole. The system does not notify survivors unless they ask to be notified.

Survivors carry the burden of navigating a complex system

Once an offender is in federal custody, the responsibility shifts entirely onto survivors to:

- Understand how CSC and PBC operate

- Know their rights in order to be able to advocate for themselves and their loved ones.

- What information to ask for, whom to ask, and what to do within the appropriate (and rigid) timelines.

The onus is on victims and survivors – those who have suffered harm – to navigate a complicated system in which they are treated as an afterthought.

- One survivor shared the Parole Board did not update them for 6 months due to a computer error. They said their safety was on the line and the Parole Board failed them.[44]

Gaps in support and accountability

The OFOVC regularly hears from victims who didn’t know that they had to register with CSC or PBC to stay informed, or who were confused over their right to submit Parole Board victim statements.[45] For many, especially those who had already submitted a VIS at sentencing , repeating their story or preparing another detailed account, without legal or therapeutic support, can be difficult.

Recent legislative changes offer some promise. Bill S-12 introduced a requirement that victims and survivors be asked whether they wanted to receive information about corrections.[46] The OFOVC will continue to monitor the implementation of these provisions.

Help us to help survivors. When survivors raise concerns or file complaints with the OFOVC, the OFOVC does not have the legislative ability to compel evidence used to make a decision directly affecting the survivor. As a result, victims are often forced to resubmit their information, and explain their situation again, without knowing what documents the agency used or what conclusions were drawn.

- This is an administrative and emotional burden on the victim.

- In contrast, the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI) has the power to compel any information relevant to their investigations – a power the OFOVC does not currently have.[47]

Processes must reflect the realities of marginalized survivors. For Indigenous and racialized survivors, existing processes need to reflect culturally grounded understandings of healing, harm, or justice. Survivors may not trust the institutions managing offender release and may feel excluded or tokenized when they try to participate.

Survivors are forced to make an impossible choice – privacy or safety

“Observing my ex’s day parole hearing last year and the full parole hearing this year was validating in many ways, but it was also harmful. As you are likely aware, during a parole hearing, victims are restricted to their prepared statements and otherwise are committed to silence even when untruths are spoken and they are disparaged by the offender or their representative.” [48]

In cases of sexual violence, where coercive control and psychological abuse are common, offenders may exploit federal parole and conditional release systems to maintain control. We heard:

- Victims heard offenders lying during parole hearings, where victims have no opportunity to rebut inaccurate statements, leaving them feeling unheard and revictimized.[49]

- Parole hearing took place in a healing center and the survivor had to walk through what was “his community” and “his home” with all of “his support” there. The parole report said he was low risk and “only” a risk to his intimate partner (the survivor).[50]

- Parole Board commended the offender for taking a plea agreement and “essentially sparing me from a trial.” [51]

- When parole hearings are held in a minimum-security prisons and healing centres, survivors can feel that these hearings are not “safe”. Survivors feel that they are in the living space of the offender.[52]

Requesting conditions shouldn’t be a painful choice between safety and privacy

“We shared concerns with your Office about offenders being released on parole or moved to an institution within the same community where their victim(s) live and being out in the community on escorted and unescorted release. While we recognize offenders eventually are released into the community, from a victim safety perspective, more care and attention must be given to their safety and security concerns.” [53]

To request protective conditions (e.g., geographic restrictions), survivors must often submit personal details about the ongoing effects of the offence. This information is disclosed to the offender. Knowing that this information will be shared with the offender creates an impossible choice between personal safety and personal privacy.

Some victims have indicated that they do not want to describe the ongoing harm to an offender who was motivated by sadism or racism, but they still want a court or Parole Board Members to know the ongoing effect of the offence.

What is a Victim Statement?

It is a statement written by a survivor and presented to the PBC or CSC when they are making decisions about an offender. The statement

- describes how the offender’s crime has impacted them

- reports any safety concerns

The content and limits on a victim statement are found in policy documents of the PBC and CSC.

Helpful clarifications about victim impact statements and victim statements have been published by Justice Canada and Public Safety Canada. See Victim Impact Statement and Infographic: Preparing a Victim Statement - Canada.ca

Survivors are often surprised to learn that conditions from pre-sentencing do not apply while the offender is incarcerated – unless a Court has ensured that the order stays in force.

- Survivors can ask for specific conditions and explain the reason for their request to both correctional and parole authorities. Board members can also independently impose any special conditions - regardless of whether a victim sought them.

- The information must also be provided to the offender. We have heard from survivors that they feel they must choose between sharing personal information with strangers or with the offender and the safety of themselves and their families.

Survivors do not understand that, in the current correctional system, an offender will be released long before their sentence ends

“The offender received a guilty verdict and a significant sentence – 2 1/2 years jail time. I thought he wouldn’t be eligible for parole until 1/3 of sentence, but actually, he is not available for FULL parole until 1/3 of his sentence. He was given day parole even earlier.” [54]

“There are so many examples that… span across Canada of offenders who get sentenced and spend the bare minimum time incarcerated just to get out and immediately reoffend. I know in my particular area there is a pedophile who has been in and out of custody for years. When I learned of this person, he had just been released and literally within days was back in custody as he had already reoffended. When he was finally convicted, he received a 10-year sentence. However, he is eligible for UTA [Unescorted Temporary Absence] as early as this year. He is eligible to apply for parole as early as 2026 and his SR [Statutory Release ] date is 2029. This means he will only be locked up for a maximum of 6 years after he spent 30+ [years] abusing innocent children. Destroying their childhoods. Ripping away their innocence.” [55]

Survivors are often surprised to learn that the sentence length announced in court does not equate to the actual time the offender will spend in custody.

- Survivors have described feeling betrayed by the system.

- We heard that this contributes to a sense of injustice, as offenders cascade through security levels quickly and apply for temporary absences and eventually parole.

- The OFOVC regularly hears myths and inaccuracies, sometimes based on entertainment sources, about the corrections and parole systems, and the criminal justice system in general.

- The CSC has published helpful information about offender releases.

TAKEAWAY

Justice for survivors means having their voices respected,

not redacted.

Respecting dignity starts with listening.

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Interview #439

[2] Correctional Service Canada. (2025, July). Corrections and Conditional Release Statistical Overview 2023 (Table C20c: Total offender population serving a sentence for a violent offence, 2022–23). Government of Canada.

[3] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #056

[4] R v. Gabriel 1999 CanLII 15050 (ONSC)

[5] M Lindsay. (2015). Victim Impact Statements in a Multi-site Criminal Court Processing Survey.

[6] Caselaw review of sentencing decisions for sexual offences in non-appeal courts, 2014-2024. Westlaw analysis, July 31, 2025.

[7] Young, A. Dhanjal, K. (2021) Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century. Department of Justice Canada.

[8] Young, A. Dhanjal, K. (2021) Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century. Department of Justice Canada.

[9] SISSA Survivor Interview #394

[10] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #176

[11] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #98

[12] SISSA Written Submission #13: Canadian Centre for Child Protection Inc.

[13] Strumpf, B. (2024). Results from the 2022-2023 Child Advocacy Centre/Child and Youth Advocacy Centre National Operational Survey. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada, p. 19.

[14] SISSA Consultation Table #07: Human Trafficking - Crown Attorneys, Police and Victim Services. For a discussion on justice needs of survivors with intellectual disabilities, see Spaan, N. A., & Kaal, H. L. (2018). Victims with mild intellectual disabilities in the criminal justice system. Journal of Social Work, 19(1), 60-82.

[15] Consultation Table #07: Human Trafficking; Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult; Consultation Table #17: Law Enforcement; Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[16] SISSA Survivor survey response #176

[17] SISSA Consultation Table #07: Human Trafficking; Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult; Consultation Table #17: Law Enforcement; Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[18] SISSA Consultation Table #06: Newcomers

[19] Annex D: SISSA Written Submission #31: Ontario Native Women’s Association

[20] Survivor Survey, Response #867

[21] SISSA Survivor Interview #38

[22] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #132

[23] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #122

[24] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s 722(8).

[25] R. v. Chaulk, 2021 NLPC 1319A00729 2021 CanLII 81813 (NL PC) | R. v Chaulk | CanLII; R. v. I.F.L., 2022 ONCJ 310 (CanLII), 2022 ONCJ 310 (CanLII) | R. v. I.F.L. | CanLII

[26] R v. K.P., 2022 SKQB 66 (CanLII) at para 40.

[27] Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, SC 2015, c 13, ss 14–15.

[28] R v. C.C. (2018) ONCJ 542

[29] R v. C.C. (2018) ONCJ 542, at para 27

[30] R v. Solorzano Sanclemente 2019 ONSC 695, at para 18; R v. KP 2022 SKQB 66; R v. White Quills 2020 ABPC 177

[31] R v. Adamko 2019 SKPC 27, at para 34

[32] R v. Friesen 2020 SCC 9, at para 85

[33] R v. C.C. (2018) ONCJ 542.

[34] R v. C.C. (2018) ONCJ 542, at para 24.

[35] R v. Aklok, 2020 NUCJ 37 (CanLII)

[36] R v. Aklok, 2020 NUCJ 37 (CanLII). Emphasis added. Footnotes omitted.

[37] R v. Friesen 2020 SCC 9, at para 85

[38] SISSA Survivor Interview #537

[39] SISSA Written Submission #46

[40] SISSA Consultation Table #05: Child & Youth EN

[41] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, RSC 1992, c 20, s 27(3).

[42] SISSA Survivor Interview #382

[43] SISSA Survivor Interview #519

[44] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #129

[45] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response # 382

[46] Parliament of Canada. (2024). Bill S-12, S-12 (44-1). LEGISinfo.

[47] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, RSC 1992, c 20, s 172.

[48] SISSA Written Submission #02

[49] SISSA Written Submission #02

[50] SISSA Survivor Interview #048

[51] SISSA Written Submission #02

[52] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #304

[53] SISSA Written Submission #13

[54] SISSA Survivor Interview #048

[55] SISSA Survivor Interview #684. In this quote, SR means statutory release date.