Testimonial Aids

“The goal of the court process is truth-seeking and, to that end, the evidence of all those involved in judicial proceedings must be given in a way that is most favourable to eliciting the truth.” [1]

Supreme Court of Canada Justice L’Heureux-Dubé

ISSUE

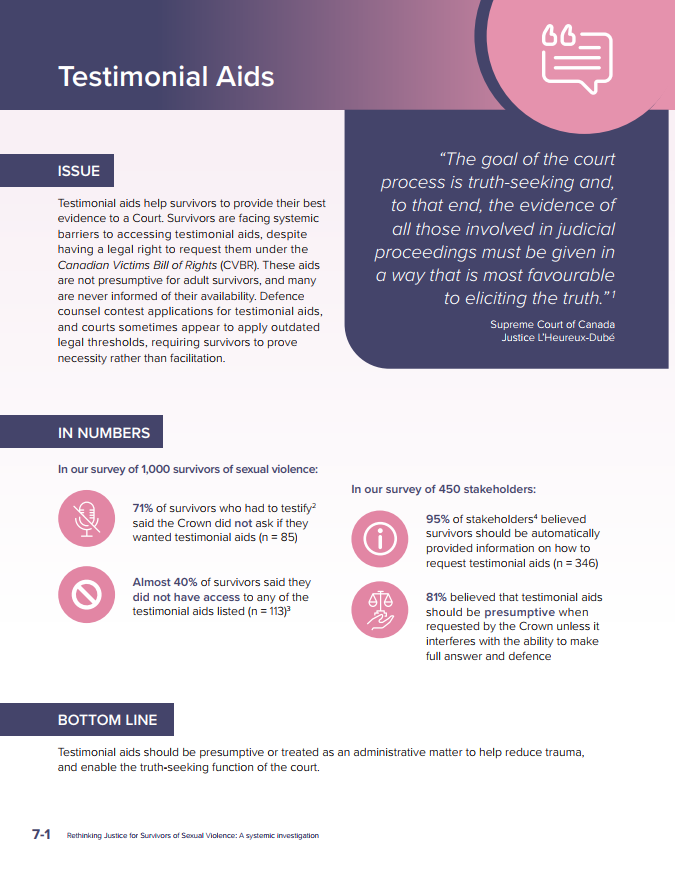

Testimonial aids help survivors to provide their best evidence to a Court. Survivors are facing systemic barriers to accessing testimonial aids, despite having a legal right to request them under the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR). These aids are not presumptive for adult survivors, and many are never informed of their availability. Defence counsel contest applications for testimonial aids, and courts sometimes appear to apply outdated legal thresholds, requiring survivors to prove necessity rather than facilitation.

IN NUMBERS

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- 71% of survivors who had to testify[2] said the Crown did not ask if they wanted testimonial aids (n=85)

- Almost 40% of survivors said they did not have access to any of the testimonial aids listed (n=113)[3]

In our survey of 450 stakeholders:

- 97% of stakeholders[4] believe survivors should be automatically provided information on how to request testimonial aids (n = 346)

- 81% believed that testimonial aids should be presumptive when requested by the Crown unless it interferes with the ability to make full answer and defence

KEY IDEAS

- Information about testimonial aids should be proactively offered to survivors

- Access to testimonial aids should be presumptive, not discretionary

- Testimonial aids should be available consistently across Canada

- There is an ongoing need for testimonial aids

BOTTOM LINE

Testimonial aids should be presumptive for survivors of sexual violence to help them participate more safely, reduce trauma, and enable the truth-seeking function of the court.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The federal government should amend the Criminal Code to increase access to testimonial aids:

Option 1: Administrative approach

5.1 Treat testimonial aids for sexual offences as an administrative matter that does not require a hearing to be awarded, based on the presumptions that sexual offence proceedings create a high likelihood of retraumatization. Testimonial accommodations for victims support the truth-seeking function of the court.

Option 2: Rebuttable Presumption

5.2 (a) Create a rebuttable presumption for testimonial aids for adult survivors of sexual offences.

(b) Require the Court to inquire if a victim has been offered or requested testimonial aids.

(c) Provide that, where a judge decides that a defence’s objection to testimonial aids was frivolous or made in bad faith, the time used to contest the application for a testimonial aid will be attributed as defence delay for the purposes of a Jordan application.

(d) Provide that, where the judge decides not to order testimonial aids, they must provide written reasons.

Additional provisions

5.3 Clarify that victims and witnesses may access multiple testimonial aids at the same time.

5.4 Add support dogs as a testimonial aid.

5.5 Clarify that the use of video testimony (s 486.2) outside the courtroom also means outside the courthouse.

5.6 [If preliminary hearings are not eliminated] provide that any testimonial aids used at a preliminary inquiry are automatically granted for a trial.

Amendment to the CVBR

5.7 The federal government should amend the CVBR to set out that victims have a right to testimonial aids (currently it is a right to request testimonial aids).

Background

Testimonial aids are tools provided in the Criminal Code that help survivors and witnesses to testify. Testimonial aids include:

- Excluding the public from the courtroom.

- Allowing a support person to be beside the witness when they are testifying.

- Allowing the survivor to testify outside the courtroom by closed-circuit television (CCTV) or inside the courtroom behind a screen.

- Preventing a self-represented accused from cross-examining a witness under 18 years or where the charge is a sexual assault offence.[5]

The Criminal Code also provides that a judge may make any order for a testimonial aid that is necessary to protect the security of witnesses and has several provisions to allow evidence by video, including during preliminary inquiries.[6]

Our investigation

Many survivors were NOT offered testimonial aids according to our survivor survey

- 71% said the Crown did not ask if they wanted testimonial aids (n=85).

- 25% said the Crown asked for testimonial aids at trial and they were granted (n=85).

- Almost 40% said they did not have access to any testimonial aids listed (n=113).

Stakeholders in our survey believed that testimonial aids should be presumptive:

- Over 80% would support Criminal Code amendments for testimonial aids to be presumptive when requested by the Crown unless the accused shows it interferes with the ability to make a full answer and defence (n = 361).

- Over 95% believe survivors should be automatically provided with information on how to request testimonial aids (n = 346).

Why it matters: Testimonial aids can help facilitate both survivor and witness participation and minimize stress when testifying in court.[7] Many judges and lawyers recognize that testimonial aids can help witnesses provide their best evidence while not violating an accused person’s fair trial rights.[8]

- The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has said that an accused does not have an absolute right to an unobstructed view of a witness who testifies against the accused. That right is subject to broader societal needs, in particular the need to protect and encourage child witnesses when they are testifying.[9]

- The SCC indicates that testimonial aids facilitate the truth-seeking function by allowing a complainant to be able to give her evidence more fully and candidly. [10]

These aids have been an option in Canada since the 1980s on a case-by-case basis.

- In 2006, Parliament provided that testimonial aids such as a CCTV, a support person, and video-recorded statements are presumptive for children.[11]

The CVBR provides victims and survivors with a right to request testimonial aids[12] as part of their right to protection. Consideration of the witness’ right to testimonial aids is in the interests of the proper administration of justice.

- In our view, the accused should not have standing on what a survivor needs to participate safely.

How to obtain testimonial aids?

- Victims of crime or witnesses can ask the Crown prosecutor to request that the Court grant testimonial aids before or at any time during the proceedings. The victim or witness is also allowed to directly ask the Court.[13]

- If anyone under 18 or a person with a disability requests a testimonial aid, it will be granted unless the Court believes it would interfere with the proper administration of justice.[14]

- An adult may be granted a testimonial aid if the Court believes it would make it easier for the victim or witness to testify fully and honestly or to serve justice. The Court will consider factors such as the witness’ age, the nature of the offence, the nature of any relationship between the witness and the accused, and whether the testimonial aid is needed for the witness' security.[15]

- In C. c. R., the Court acknowledged that the CVBR changed the threshold for testimonial aids. Applicants now just need to show that the testimonial aid will facilitate giving their account.[16]

Government action

- The National Action Plan to End Gender-based Violence acknowledges that testimonial aids are a positive measure for survivors in the criminal justice system (CJS).[17]

- Between 2015 and 2020, the Federal Victim Strategy provided $125 million in funding for projects and initiatives, some of which provided greater access to testimonial aids.[18]

- The 2022 report from the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights discussed testimonial aids as an option of support and highlighted the need for survivors to have choices such as testifying on video or in person.[19]

- A 2019 Department of Justice study found that one of the biggest obstacles with respect to the use of testimonial aids was professional resistance to their use (reported by 45% of respondents).[20]

Past OFOVC recommendation

In 2023, the Ombud submitted a brief to the Sub-Committee on the Open Court Principle and highlighted positive feedback around virtual testimony and access such as safety and accessibility. Victims should be informed of testimonial aids available for both in person and virtual hearings.

Testimonial aids and virtual participation

A detailed survivor perspective on testimonial aids and the value of virtual court participation for sexual assault survivors is outlined in this article in The Walrus. [21]

My Day in Zoom Court: Virtual Trials are a Better Option for Sexual Assault Survivor.

What we heard

Information about Testimonial Aids Should be Proactively Provided to Survivors

- “I was never told about testimony aids.“ [22]

- “Didn’t know any of the testimonial aids existed. Information deficit. Nobody tells you, and you don’t get what you need.” [23]

- “Crown asked if she wanted [closed circuit television] CCTV and she was surprised. [The survivor] didn’t know it was an option. Crown told her judge has to make determination, but she would advocate. Judge allowed it.” [24]

Many survivors shared that they were not aware or properly informed about testimonial aids.

Information about testimonial aids should be automatically provided to survivors.

- One survivor shared, “I’d also like Crown to share what options a survivor has when testifying (like testifying behind a screen, by video, etc.). I only found that information out from a friend.” [25]

- “Let survivors testify outside of the court room via virtual testifying in order to not be revictimized.” [26]

- “The judge got mad at me for uncontrollable crying in the court room and even got mad at my support person who put her arm around me to support me.” [27]

- “I wasn’t told anything about witness accommodations, but a friend mentioned it to me and asked if I’d have some. This caused me to ask the Crown about having a support animal ideally, but anything would help. The Crown said I could, but the jury might not approve and think that because the assaults happened in the context of a relationship that I stayed in, a jury might think I’m now pretending to be scared of him by using accommodations.” [28]

- “Not having to look at the person who did this terrible thing to you while you testify would be a start! I applied for a screen, and it was denied.” [29]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Testimonial Aids Of 85 survivors who provided further information on access to testimonial aids:[30]

- 71% said the Crown did not ask if they wanted testimonial aids

- 25% said the Crown asked for testimonial aids at trial and they were granted

- 8% said the defence argued that they should not have access to them

- 6% said the judge allowed testimonial aids, but not all they requested

- 6% said the judge did not allow testimonial aids.

Improvements over time: When we examined these experiences by last contact with the criminal justice system, the data suggests great improvements in Crown requests for testimonial aids and an increase in granted requests:

- The proportion of survivors who said the Crown did not ask if they wanted testimonial aids decreased over time: 87% prior to 2015, 71% between 2015 and 2019, and 62% in 2020 or later

- Requests for testimonial aids that were granted increased from 13% prior to 2015 to 29% in 2015-2019, then remained relatively stable at 29% in 2020 or later

- Defence opposition to testimonial aids was not reported in our data prior to 2015, but appeared in later periods: 12% in 2015-2019, and 13% in 2020 or later.

- Judicial decision to allow only some testimonial aids were reported only from 2015 onward (12% in 2015-2019, 7% in 2020 or later).

- Complete denial of testimonial aids by judges was not reported prior to 2015 but occurred in 12% of cases in 2015–2019 and 7% in 2020 or later.

Access to testimonial aids should be presumptive

Survivors and stakeholders shared that testimonial aids should be automatically offered

These views are consistent with our Office’s 2024 recommendation that testimonial aids should be presumptive.[31]

- One stakeholder said, “Create an automatic process for testimonial aids in all sexual assault cases.” [32]

- Another stakeholder shared that offering testimonial aids should be mandatory unless the defence can prove that testimonial aids would not be in the interest of justice.[33]

An understanding of the neurobiology of trauma helps us understand that people who have experienced trauma may not be able to testify in the way the court system demands:

“…trauma produces actual physiological changes, including a recalibration of the brain’s alarm system, an increase in stress hormone activity, and alterations in the system that filters relevant information from irrelevant.” [34]

- Offering testimonial aids might help a person feel safer, which can in turn help their ability to recall information.

A courtroom is already an intimidating place. Testifying in front of a person who harmed you can exacerbate the feeling of intimidation. Ruthless cross-examination can lead to confusion and retraumatization.

- Testimonial aids can help survivors answer questions by providing some sense of safety, limiting the traumatizing aspects of cross-examination in a courtroom setting and optimizing the truth-seeking goal of the court.

“The way trauma affects the brain has been well studied and it’s predictable. Unfortunately, it runs counter to a lot of our notions of what makes a good witness.” [35]

Trauma-informed practice: decades of research have established how trauma affects the brain and how that affects participation in the court process.[36]

- “Only if we assume that the accused has a right to intimidate the complainant by his presence or facial expressions can this measure be seen as a violation of his rights. As one judge put it, there is no right on the part of the accused to glower at a complainant.” [37]

We heard that many judges view testimonial aids positively.

- A victim services organization informed us that it is a regional practice to have counsel and judge in the courtroom and to use CCTV and have a support person for the survivor. They also shared that judges are able to grant multiple supports at the same time.[38]

Allow CCTV from any community equipped to provide the service. We heard recommendations to amend the Criminal Code to allow greater use of video testimony out of town. This would significantly reduce the burden on survivors living in rural or remote communities who may otherwise need to travel repeatedly for proceedings that are cancelled or adjourned. It would also provide greater protection for survivors who are asked to return to small communities for the trial where they are unsafe.

- We heard from one survivor who travelled from out of the country to attend a trial that was then adjourned for a medical appointment. The full travel costs including accommodation, time off work, and boarding for pets while abroad was about $10,000. The compensation which her country of residence provides to support participation in a justice process would be cancelled because the hearing in Canada was not held. This case was referred to the Ombudsperson by a Special Advisor to a foreign Minister of Justice.

- When we know that the technology exists to allow the survivor to participate virtually from their home country without any additional expenses to the survivor, this situation is beyond regrettable.

Private waiting areas and support people were common aids, according to survivors

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Access to testimonial aids should be consistent across Canada

“Where I am currently, there is such a lack of testimonial aids compared to where I used to work. It’s actually horrifying.” [39]

“In one jurisdiction I worked in, one-way screens were available that would come down from the ceiling. These were more efficient than tilt screens or video and allow judges to see witnesses clearly and also (the) accused but shield witnesses from seeing (the) accused. Such screens could be mandatory easily in all cases where requested. Video could be managed in the same way it currently is.” [40]

Limited and inconsistent access to testimonial aids

A stakeholder shared that sometimes testimonial aid applications are granted by the court, but at the last minute, the aids cannot be used due to a lack of human resources, space, or equipment.

- A private space might be granted, but it is in the corner of a busy victim services office.

- The survivor may be granted the use of a room with CCTV, but it is at an RCMP detachment cell block where the accused is detained.[41]

- We heard that the CCTV or virtual participation will be denied if internet connections are poor. There have been cases where judges will grant virtual appearances but, due to technical difficulties, the survivor is required to come in person.[42]

- One lawyer underlined the need to change the Criminal Code to allow virtual participation from a location other than the courthouse. Currently courts have varying interpretations of “outside the courtroom.” [43]

Funding may also have an impact on how the resources are provided

Some survivors have greater assistance with the court process, depending on where they live. Others do not have this type of assistance.

- Stakeholders who work with children and youth also shared that the limited resources can add delays. For example, having only one child-friendly room means having to wait until it is available to continue with a case.[44]

- One survivor said, “Believe them. Support them. And have more support around testifying including financial.” [45]

- We also heard that some places in Canada have access to court support dogs while others do not.[46]

10 Paws Up

Court support dogs were mentioned as positives for survivors and witnesses when testifying, but lack of resources causes in inconsistencies in access.

A 2014 report from the Department of Justice, Let’s “Paws” to Consider the Possibility: Using Support Dogs with Victims of Crime, discusses research on support animals that could apply to victims in the courtroom. The report outlines the many benefits of support animals, Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT), and Canadian and American perspectives on using support animals.

In 2022, the Department of Justice continued this research with a new report on:

- the definitions of service, therapy, and facility dogs

- literature available on the use of dogs in the court system

- Canadian case law where the dog handler is considered a “support person” or allowing the dog and handler to be the support person, allowing the dog to be with the witness but not the handler, or if the dog does not have a handler

- the lack of national standards or regulating bodies for training or testing

- the lack of research into the types of dogs available such as a facility or therapy dog

- the focus of many current studies on child victims of sexual abuse

We recommend the Criminal Code to be amended to allow for support dogs as a testimonial aid.

Survivors report that defence counsel are increasingly contesting testimonial aids

“I was not properly prepared for testifying; the Assistant Crown neglected to ask for the lifting of the publication ban as I requested, and defence blocked my ability to have my support person in the room with me while I testified. Throughout the entire process I was dismissed, ignored and disrespected. Defence counsel relied on rape myths and stereotypes to discredit and upset me during my testimony and blatantly ignored a warning about language with no consequences.” [47]

“He got the right to refuse court aids in both the criminal and family courts. I wasn’t allowed to have a support person from the shelter or victim services with me, but he was at a friend’s house smoking marijuana on zoom court.” [48]

A recurring theme from many survivors and Crowns was that defence counsel are increasingly contesting all procedural applications, perhaps as a means of incurring delays for the Jordan framework.

- Although the Criminal Code was amended in 2015 to provide that testimonial aids should be ordered when they will facilitate the evidence of witnesses or survivors, it is the impression of many survivors that Courts are applying the harder test of “are the testimonial aids necessary to give evidence?”

- This is an error in law, adding another hurdle for survivors. The threshold is no longer “is it necessary,” but “will it facilitate giving evidence.” [49]

Some stakeholders suggested that the current practice for testimonial aids should be reversed so defence counsel would have to prove that the testimonial aid would compromise how the accused would be able to defend their case rather than the Crown having to prove its need.[50]

- Given that testimonial aids have been found by the Courts to be entirely compatible with the section 11(b) rights of the accused and with the courts’ truth-seeking function, they believe that survivors should be granted testimonial aid presumptively or upon request.

- Making testimonial aids presumptive will reduce delays and costs to the CJS – that could be reinvested in testimonial aids, increasing their availability across the system. With finite resources, this would improve protection for survivors without diminishing trial fairness for the accused.

- Finite resources: Do we want to continue allowing the accused to use public resources (courtroom time, Crown time, judicial time) to argue that survivors do not need supports when testifying?

One suggestion to respond to these contested applications for testimonial aids was to bring in an expert witness to discuss the specific disability and how it may impact the victim and their ability to testify.[51]

“The right to face one’s accusers is not in this day and age to be taken in the literal sense. In my opinion, it is simply the right of an accused person to be present in court, to hear the case against him and to make answer and defence to it.” [52]

Crown prosecutors and testimonial aids

“Make testimonial aids an automatic practice for all victims of sexual assault (not just children) and enshrined in Crown guidelines.” [53]

One stakeholder shared how overworked and busy Crown prosecutors do not have the energy to fight for testimonial aids every time

“Crowns are overworked and under-resourced and therefore don't put time and effort into the cases. They are very quick to suggest resolving matters by way of a lesser option. They are quick to point out how hard testifying is and that matters will likely not even be reached in an attempt to discourage survivors from testifying. There is an insistence on getting an affidavit about the survivors’ fear level and why they want testimonial aids, which can make a survivor feel like they need to justify why they're afraid. The Crowns have resources in their application (such as SCC decisions about how it's understandable there is fear of testifying etc.). However, no one seems to understand how to present these arguments in court. Defence relies on how valid the fear is and questions if they're really afraid, when that is not the test. Crowns aren't doing anything to correct that and just falling into ‘this is how afraid they are.” [54]

- One stakeholder said, “Allow testimonial aids without difficulty. Crown quite often doesn't support testimonial aids.” [55]

- Another stakeholder shared that the Crown was using testimonial aids as a “bargaining tool” with the defence lawyer.[56]

There is an ongoing need for testimonial aids

“I wish I had the option to not testify in front of the abuser regardless of the privacy screen. I hated walking into the courtroom and he looked at me.” [57]

“ Zoom option was very helpful. Being in a room with accused triggered PTSD and visceral reactions I can’t control. On zoom, put a post-it note over his face to not see him. Nobody gave option to not testify in person. You have to be exposed to the person who abused you. Sadly that’s part of the process. Maybe it shouldn’t be, but it is.” [58]

We heard repeatedly that survivors do not want to see the one who caused them harm

- Having to testify and go through cross-examination is often retraumatizing. Having to sit in the same room as the accused should not be an added stressor.

- One survivor shared, “The victim should be able to decide who is allowed in the courtroom to hear that testimony because it is a very difficult thing to go through. There is so much emphasis on the accused’s rights, but little consideration given to the impacts of the process on the victim.” [59]

The courthouse and courtroom environment are intimidating

Stakeholders told us that the courts are not physically built for survivors. For example, there are common waiting areas, or they do not have comfortable testimony spaces.[60] The survivor has to put their life on hold, share their experience repeatedly, be denied remote testimony, and wait for hours without knowing when they will testify.

- Private waiting areas. In some communities, there are not sufficient spaces for survivors to wait privately.

- In northern Saskatchewan, the Ombudsperson heard about a survivor of child sexual abuse who was asked to wait in a broom closet until they were called into the courtroom. The victim service workers explained that there were better waiting spaces and access to CCTV in a victim services building across the street, but they were limited with what services could be provided within the courthouse.

- Crown Witness Coordinators in the Territories will sometimes use an RCMP truck as a safe and private space to wait with survivors.

- Privacy screen. In small courtrooms, a privacy screen may be insufficient to protect the victim, who may have to sit in such close proximity to the accused.

- Video conference. One child in a northern community was disturbed to find that even though they were permitted to testify by CCTV, the accused's face was still projected on their screen.

- In a consultation table with Crowns, they expressed concerns about safety risks when there is only one location for CCTVs.[61] These concerns included a single entrance for both witnesses and accused, limited waiting spaces for witnesses, overlapping scheduling of multiple matters.[62]

- Culturally safe spaces to testify were also mentioned. One stakeholder shared, “There are ongoing language, safety and cultural barriers to support immigrant and newcomers to Canada… It is imperative to ensure the availability of culturally safe places for the survivors in court houses while they are waiting to meet with the prosecutors or for their testimonies.” [63]

Calls for increased access to testimonial aids have not changed

In 2018, the Department of Justice held a conference on testimonial aids, with victim services workers, legal counsel, government policy employees and police.[64] Participants reported challenges when using testimonial aids with vulnerable witnesses such as the resistance to the use of testimonial aids, lack of availability/resources, technology issues (specifically CCTV equipment), and process issues for example providing 30-day advance notice to be able to use CCTV equipment.

They recommended:

- Change the process to apply for these aids and clarify the use of support animals and support people.

- Ensure broad access to testimonial aids, especially to remote, Indigenous communities.

- Changing logistics of testimonial aids. Improving screens, allowing survivors to enter court from another entrance, and expressed concerns about CCTV.

- Increasing access to technology.

- Increasing education and training for professionals and the public.

In 2018, the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety held a conference, Reporting, Investigating and Prosecuting Sexual Assaults Committed Against Adults – Challenges and Promising Practices in Enhancing Access to Justice for Victims, where one topic was testimonial aids.[65] The Working Group recommended:

- Testimonial aids be accessible in all court houses and when Crown prosecutors request them

- Allowing a survivor to testify outside the courtroom to answer questions via a CCTV or a screen during the application for these aids

- Allowing support dogs when testifying

In 2025, Dr. Kim Stanton released the Final Report on an independent systemic review of the British Columbia Legal System’s Treatment of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence. The report recommends that testimonial aids should be available in criminal and family courts (recommendation 20B).[66]

Why identity matters

Adult vs child survivors

- “Make testimonial aids for adult complainants of sexual violence mandatory if requested by the Crown - no exceptions.” [67]

- “I think that testimonial aids should be granted regardless of their age and I think dogs should be used for adults the same way they are for children/youth.” [68]

- “There should be more opportunities for adults to have access to testimonial aids who have no other underlying reason for it other than that they are very scared of their abuser.” [69]

The discretion given to the Courts to order testimonial aids creates uncertainty and stress for many adult witnesses. We heard that “aging out of presumption for testimonial aids can lead to drop out” and that “testifying was the hardest thing I have ever done” when denied these aids.[70]

Some survivors were told that testimonial aids are only available to children.

- Research has shown that children are more likely to be granted testimonial aids[71]

- While the Criminal Code makes testimonial aids presumptive for child survivors,[72] adults also have the right to request them

Northern and rural survivors

- “Provide expeditious and accessible supports for rural communities - many do not have access to transportation or can’t afford it to access mental health supports and services; nor do they have adequate access to virtual supports due to lack of strong internet or a device to connect.” [73]

- “For northern communities, survivors are scared to testify because the accused is usually a neighbour, close family friend, etc. They are scared to testify in their community because they do not want people from their community knowing the details of the incident. Difficult to have venue change at [victim's] request and closed court room applications granted. Less supports for survivors to access in the north for survivors of sexual assault.” [74]

- “Community attendance in court: The majority of sexual assault trials in large urban centres are relatively anonymous with lower levels of attendance. In northern communities, going to court is something to do, especially for circuit court. Large portions of a community may attend court for entertainment, which is particularly troubling to sexual assault survivors.” [75]

- “Returning for trial: Many people from northern communities relocate to more southern locations for different opportunities, or even to get away from a small community where everyone knows about their trauma. It is a significant barrier to have to return to northern communities to participate.” [76]

Access to testimonial aids in Northern and rural communities

- Accessibility in northern communities. We met with an inspiring Crown Witness Coordinator for the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) who challenged the assumption that the full use of testimonial aids is not possible in the territories. There is satellite internet service across the territories and newer fibre-optic service in some regions.

- She said that when staff complain about having to bring CCTV equipment to a fly-in community, she asks, “What's harder, carrying the equipment or testifying in a sexual assault trial?”

- Circuit courts are reluctant to close the courtroom, despite the deep personal nature of the evidence

- Circuit courts are often seen as a form of entertainment for the communities – which adds to the trauma of survivors who remain in the community long after the circuit court has left.

- Testimonial aids in circuit courts[77] are often limited to a support person.

- We were told that there is a particular challenge in northern areas of several provinces where the interpretation of the provision to allow testimony outside the courtroom does not allow for testimony outside of the courthouse. This limited interpretation requires survivors to travel long distances and to leave their support systems in order to give evidence.

- An Alberta Queen’s Bench case noted “Once a witness is testifying virtually, there is no practical difference in the trial setting arising from where the witness is physically located: same building, same city, another location.” [78]

- In our view, the provision can also be interpreted to allow for testimony in another building, another city, another location.

- Survivors in rural areas indicated that having courts in smaller communities would reduce the burden and stress associated with engaging with the CJS.

- They often have to travel far to meet with Crowns and attend trial.

- Better internet or capacity for video testimony would also assist these survivors and reduce delays.

Survivors with disabilities

“Greater use of closed-circuit television (CCTV) during trials could help adult survivors with disabilities testify without facing the accused directly. This approach, already used for child survivors, should be expanded to accommodate vulnerable adults.” [79]

“I had accommodations for disability. Heat pad for pain, extra breaks. Had to initiate. Wasn’t asked. No offer of testimonial aids.” [80]

We heard:

- One survivor mentioned that they were offered and granted a support dog in the courtroom, but the paperwork was not filled out in time, meaning the survivor was provided with false hope and did not have access to the support dog for testimony.

- Survivors were offered a private room to testify but it turned out to be a corner of a victim services office.[81]

- CCTVs are a good option for adult survivors with disabilities to be able to testify without seeing the accused.[82]

- Individuals who are autistic, have ADHD, or are gifted are often mistakenly perceived as less credible due to atypical communication styles.[83]

- The UK Family Justice Council (2017) recommends the use of intermediaries and tailored accommodations.[84] Witnesses who are neurodivergent should be offered accommodations such as breaks, communication supports, and question reformulation.

Testimonial aids are particularly important for people with disabilities and neurodivergence

In 2009, Justice Canada conducted a study with twelve victim service providers about their experiences with those who have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Participants agreed that criminal justice actors were inadequately aware of FASD and did not know that testimonial aids could benefit these witnesses.

- Recommendations included appropriate training and strategies for working with people with FASD and communication and learning challenges.[85]

Case study: No-one challenged this accused

“The man who raped me for years made himself at home in the victim witness room. I had not seen him in decades. It was extremely traumatizing, and he refused to leave. I was due on the stand two minutes later.

I had no time to smudge, prepare, and rebalance myself. I felt this was an assault on my whole spirit and to then be expected to sit on the stand for hours only minutes after.

The abuser then, even though he was told this room was for victims, kept returning to my supposedly safe space throughout the trial and we had to get the court guard to tell him. He and his lawyer then stood in front of my safe space room throughout the trial and then the women's washroom as well.

The victim's room was barren of any supportive atmosphere. There should be water, juices (diabetic here), some snacks, the Sacred Medicines, some Grandfather stones.

The court room was freezing, and I was expected to hold my microphone and sit in the most uncomfortable position so my abuser and his ex-wife, who helped cover up his crimes for decades, could hear. His lawyer actually stopped the court numerous times to make me repeat louder as they kept saying they could not hear. So, the abuser and his ex-wife were more important than a disabled woman who was testifying.

Again, no legal representation cared about how absolutely horrific it was to repeat disgusting things over and over with abusers only a few feet away.

His ex-wife was allowed to record the whole trial because she was supposedly deaf or hard of hearing??? What about my rights as the victim to not be exploited by this woman? I to this day fear she is sharing my personal and most painful experiences with others. This should never have been allowed!” [86]

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve the tools they need to testify safely and effectively

Support measures are rights, not consessions.

Endnotes

[1] R v. Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC), [1993] 4 SCR 475

[2] SISSA Survivor Survey

[3] Ibid

[4] SISSA Stakeholder Survey

[5] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, ss. 486.1–486.3.

[6] See, for example, section 715.1 and 715.2.

[7] McDonald, S. (2021). Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 11, Helping Victims Find their Voice: Testimonial Aids in Criminal Proceedings. Department of Justice Canada.

[8] R v Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC); Child Witness Project, & Bala, N. (2005). Brief on Bill C-2: Recognizing the Capacities & Needs of Children as Witnesses in Canada’s Criminal Justice System, submitted to the House of Commons Committee on Justice, Human Rights, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness; Young, A. N., & Dhanjal, K. (2021). Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century.

[9] R v Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC)

[10] R v. Levogiannis, 1990 CanLII 6873 (ON CA), at para 35; R v. J.Z.S., 2008 BCCA 401 (CanLII)

[11] Bala, N. (2025). Child Witnesses in Canada’s Criminal Justice System: Progress, Challenges, and the Role of Research. Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 18. Department of Justice Canada.

[12] Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, S.C. 2015, c. 13, s. 13.

[13] Government of Ontario. (2017). Crown Prosecution Manual, D. 35: Testimonial Aids and Accessibility.

[14] Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2024, May 10). Testimonial Aids.

[15] Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, ss. 486.1, 486.2.

[16] F.C. c. R, 2024 QCCQ 1474 (CanLII)

[17] Women and Gender Equality Canada, W. (2022). National Action Plan to End Gender-based Violence.

[18] Evaluation Branch & Internal Audit and Evaluation Sector. (2021). Evaluation of the Justice Canada Federal Victims Strategy [Report].

[19] Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. (2022). Improving support for victims of crime. In Report of the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights.

[20] Young, A. N., & Dhanjal, K. (2021). Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century, Department of Justice Canada. CanLIIDocs.

[21] Watson, S. (Pseudonym), & Schreiber, M. (2021. Updated 2024). My day in Zoom court: Virtual trials are a better option for sexual assault survivors. The Walrus.

[22] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #998

[23] SISSA Survivor Interview #004

[24] SISSA Survivor Interview #046

[25] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #280

[26] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #790

[27] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #289

[28] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #170

[29] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #37. This would apply both to section 486 provisions of the Criminal Code and to the video testimony of witnesses. (s. 715.1 Evidence of victim or witness under 18).

[30] Multiple responses were allowed.

[31] OFOVC. (2024). An Open Letter to the Government of Canada: It’s time for victims and survivors of crime to have enforceable rights.

[32] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #106

[33] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #37. This would apply both to section 486 provisions of the Criminal Code and to the video testimony of witnesses. (s. 715.1 Evidence of victim or witness under 18).

[34] Kolk, B. V. D. K. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

[35] Beazley, D. (2024, January 2). Understanding the impact of trauma on witness testimony. CBC / ABC National.

[36] P. Ponic et al. (2021). Trauma- (and Violence-) Informed Approaches to Supporting Victims of Violence: Policy and Practice Considerations. Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 9.

[37] R v. Levogiannis, 1993 CanLII 47 (SCC), [1993] 4 SCR 475, at para 17. Benedet, J., & Grant, I. (2012). Taking the Stand: Access to Justice for Witnesses with Mental Disabilities in Sexual Assault Cases. Osgood Hall Law Journal, 50(1), 1–45.

[38] SISSA Survivor Interview #017

[39] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #28

[40] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #55

[41] SISSA Survivor Interview #008

[42] SISSA Survivor Interview #008

[43] SISSA Written Stakeholder Submission #73.

[44] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth

[45] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #954

[46] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #045

[47] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #293

[48] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #286

[49] F.C. c. R., 2024 QCCQ 1474 (CanLII)

[50] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #122

[51] SISSA Consultation Table #07: Human Trafficking Crown

[52] R v. J.Z.S., 2008 BCCA 401 (CanLII)

[53] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #404; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #228

[54] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #346

[55] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #320

[56]SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #228

[57] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #817

[58] SISSA Survivor Interview #004

[59]SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #175

[60] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #368

[61] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown Consult

[62] Similar concerns were raised in a Justice Canada Knowledge Exchange. Hickey S., McDonald S. (2021). Testimonial AIDS Knowledge Exchange: Successes, challenges and Recommendations - Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 12. Department of Justice Canada.

[63] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #96

[64] Hickey S., McDonald S. (2021). Testimonial AIDS Knowledge Exchange: Successes, challenges and Recommendations - Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 12. ). Department of Justice Canada.

[65] Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety (2018). Reporting, Investigating and Prosecuting Sexual Assaults Committed Against Adults – Challenges and Promising Practices in Enhancing Access to Justice for Victims. Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat.

[66] Stanton, K. (2025). The British Columbia legal system’s treatment of intimate partner violence and sexual violence. Government of British Columbia.

[67] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #6

[68] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #204

[69] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #293

[70] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #53; SISSA Survivor Interview #140

[71] Young, A. N., & Dhanjal, K. (2021). Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century. Department of Justice Canada. CanLIIDocs.

[72] Criminal Code, sections 486.1, 486.2, 486.3.

[73] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #205

[74] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #223

[75] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #008

[76] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #008

[77] Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region to different towns or communities where they will hear cases.

[78] R v SLC, 2020 ABQB 515 (CanLII) includes a comprehensive discussion of testimony outside the courtroom.

[79] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[80] SISSA Survivor Interview #004

[81] SISSA Consultation Table #25: Persons with Disabilities

[82] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[83] Lim et al. (2022). Autistic Adults May Be Erroneously Perceived as Deceptive. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(2), 490-507.

[84] Family Justice Council. (2020). Safety from Domestic Abuse and Special Measures in Remote and Hybrid Hearings.

[85]McDonald, S. (2018). Helping Victims Find their Voice: Testimonial Aids in Criminal Proceedings. Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 11. Department of Justice Canada

[86] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #439