Access to Therapeutic Records

CONTENT WARNING: This chapter includes traumatic content

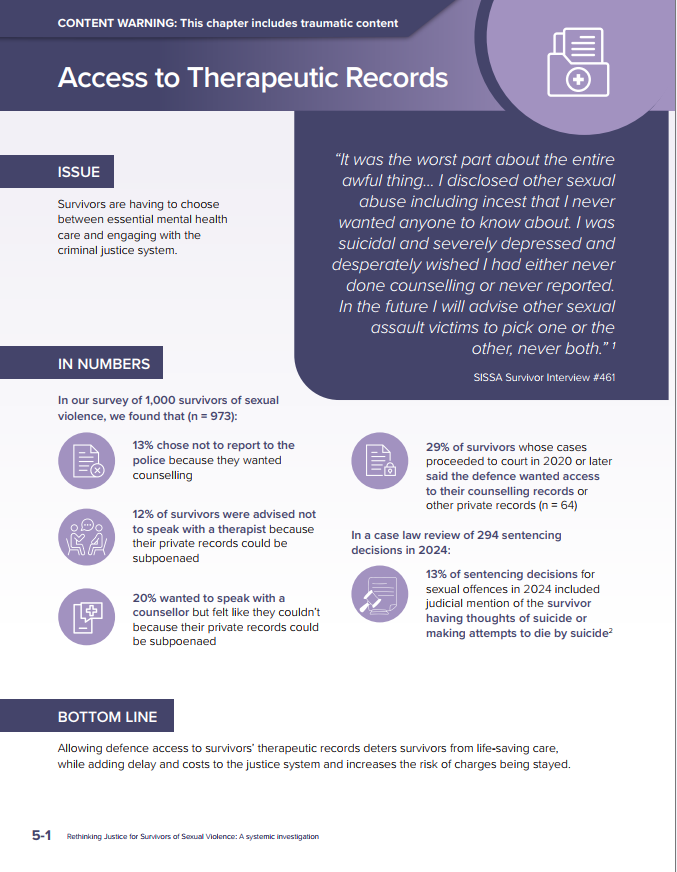

“It was the worst part about the entire awful thing... I disclosed other sexual abuse including incest that I never wanted anyone to know about. I was suicidal and severely depressed and desperately wished I had either never done counselling or never reported. In the future I will advise other sexual assault victims to pick one or the other, never both.” [1]

ISSUE

Survivors are having to choose between essential mental health care and engaging with the criminal justice system.

IN NUMBERS

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- 13% chose not to report to the police because they wanted counselling

- 12% of survivors were advised not to speak with a therapist because their private records could be subpoenaed

- 20% wanted to speak with a counsellor but felt like they couldn’t because their private records could be subpoenaed

- 29% of survivors whose cases proceeded to court in 2020 or later said the defence wanted access to their counselling records or other private records (n = 64).

In a case law review of 294 sentencing decisions in 2024:

- 13% of sentencing decisions for sexual offences in 2024 included judicial mention of the survivor having thoughts of suicide or making attempts to die by suicide.[2]

KEY IDEAS

- Therapeutic records are different from other records

- The threat of disclosure of a survivor’s therapeutic records[3] is a risk to the health and safety of survivors

- Records applications have a chilling effect on access to therapy

- Records applications have a chilling effect on reporting to police

- Some parts of the records regimes worsen Jordan-related delays

- Allowing defence access to therapeutic records can violate survivors’ Charter rights

BOTTOM LINE

Allowing defence access to survivors’ therapeutic records deters survivors from life-saving care, while adding delay and costs to the justice system and increases the risk of charges being stayed.

RECOMMENDATIONS

3.1 Invest in independent legal advice (ILA) and independent legal representation (ILR) The federal government should immediately invest in independent legal advice (ILA) and independent legal representation (ILR) programs for any proceeding where a survivor’s CVBR or Charter rights are engaged. This includes for sexual history, record production and record admissibility applications.

The federal government should immediately amend the Criminal Code to:

3.2 Protect therapeutic records: Recognize that psychiatric, therapeutic and counselling records as enumerated in s. 278.1 are distinct from other private records and should be the subject of a higher threshold to be accessed by the defence. Apply the “innocence at stake” threshold or “class protection” to Stage One of both private records regimes, given the highly prejudicial impact on the health, equality and safety of survivors during a time of predictable distress.

3.3 Add context disclaimers: Provide that, when used as evidence, any disclosure of a therapeutic record shall include a disclaimer that the contents are based on the therapist's impressions, have not met the privacy requirements of allowing the complainant to review and correct inaccuracies, and may contain factual errors.

3.4 Expand the definition of ‘record’: Amend the definition of a record in s. 278.1 of the Criminal Code to:

(a) Include electronic data found on a phone device or internet-based account for the purposes of the private records regimes

(b) Include the contents and results of a sexual assault examination kit (SAEK).

(c) Provide participation rights and standing for complainants where a motion for direction on the definition of a record engages the privacy interests of complainants.

3.5 Clarify the express waiver provision: Amend the express waiver provision for third party records (s. 278.2) to create an exception, where the Crown intends to adduce private records and cannot obtain the complainant’s express waiver, records can be disclosed to the defence without an express waiver.

3.6 Simplify applications of sexual non-activity: Create a simplified statutory regime for the complainant’s evidence of sexual non-activity and sexual activity when presented by the Crown.

3.7 Expand regime coverage: Include sex trafficking and voyeurism in all the records regimes.

Our investigation

Background

The Criminal Code contains several important provisions outlining how and if the sexual history evidence of a complainant or evidence in the possession of the accused or a third party can be used in sexual offence prosecutions. These are valuable protections for complainants about evidence for which they have a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Three regimes set out in the Criminal Code work together: sexual history evidence (s 276), private records in possession of a third party (s. 278.2), and private records in the possession of the accused (s. 278.92).

Sexual History Evidence

Section 276 of the Criminal Code governs the admissibility of evidence about a complainant’s sexual history and the uses of that evidence. The s. 276 regime aims to protect the integrity of the trial by excluding irrelevant and misleading evidence, protecting the accused’s right to a fair trial, and encouraging the reporting of sexual offences by protecting the security and privacy of complainants. Section 276 applies to any communication made for a sexual purpose or whose content is of a sexual nature to any proceeding in which a listed offence is implicated.[4]

A defence application under section 276 will outline the details of what they want to introduce as evidence and its relevance. The judge will determine if the evidence is admissible using the test in s. 276(2) and the factors in s. 276(3).

Twin myths and stereotypes cannot be used. The twin myths are that the past sexual behaviour of survivors make them (1) less worthy of belief about a sexual assault or (2) more likely to consent to the sexual activity in question. Section 276 of the Criminal Code is deliberate in stating that evidence of a complainant’s other sexual history can’t be used to infer that, by reason of that activity, the victim is more likely to have consented or less worthy of belief.

- “Sexual history evidence is also presumptively inadmissible to support other inferences unless the evidence is of specific instances of sexual activity, is relevant to an issue at trial, and has significant probative value that is not outweighed by the danger of prejudice to the proper administration of justice. …… The sexual history evidence regime is intended to keep myths and stereotypes about victims of sexual offending out of the courtroom to support its truth-seeking function.”[5]

- The SCC upheld these provisions in R v. Darrach.[6]

The procedure to be followed for prior or other sexual history applications is the same as the procedure for private records in the possession of the accused. (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

The factors used by the judge in a prior or other sexual history application include: “the potential prejudice to the personal dignity and right to privacy of any person to whom the record relates” and “the right of the complainant and every other person to personal security and to full protection and benefit of the law.”[7]

Private Records in possession of a Third Party[8] (Production and Admissibility)

The third-party records regime was enacted to require courts to conduct a balancing exercise before producing private records in cases of sexual assault.[9]

“Parliament enacted this regime with a view to (1) protecting the dignity, equality, and privacy interests of complainants; (2) recognizing the prevalence of sexual violence in order to promote society’s interest in encouraging victims of sexual offences to come forward and seek treatment; and (3) promoting the truth-seeking function of trials, including by screening out prejudicial myths and stereotypes.”[10]

What kind of records are sought in these applications?

- Psychiatric, therapeutic or counselling records

- Police records

- Child protection records

- Social services records

- Education or employment records

- Medical records unrelated to the assault

- Personal journal or diary

- Photos or videos

- Private electronic communications

This is not an exhaustive list*. The Court will consider whether the documents at issue are similar to these kinds of documents.

* See section 278.1. of the Criminal Code

Stage One determines if the records should be produced to a judge.

- A defence application for records in the possession of a third party must be made in writing, identify the record the accused seeks to have produced and the name of the person who has possession or control of the record, and must set the grounds upon which the accused relies to establish that the record is likely relevant to a triable issue or the competence of a witness to testify.

- This application must be provided to the Crown, the record-holder and the complainant 60 days prior to a hearing being scheduled. At the same time, the defence must serve a subpoena for the records on the record-holder.

- Stage One usually involves an oral hearing and submissions from the defence, the Crown’s response, and, if they make submissions, the complainant’s and the record-holder’s submissions and determines if the record is likely relevant to a triable issue or the competence of a witness to testify. If the judge agrees that they meet these criteria, the records are produced to the judge for review and the application goes to Stage Two. If the judge disagrees, the application ends.

- These applications can’t be published or shared with others, and the Stage One hearing takes place in camera.

Stage Two determines if the records should be produced to the accused

- Based on evidence presented at Stage One by the defence, Crown, and if they decide to give evidence, from the record-holder and complainant, the trial judge must determine whether the records sought by the defence meet the statutory criteria to be produced to the accused.

- To make this decision, the judge shall consider, “the effects of the decision to release or withhold the record on the right to privacy, personal security and equality of the complainant.”

- The judge shall consider these factors: “the potential prejudice to the personal dignity and right to privacy of any person to whom the record relates” and “society’s interest in encouraging the obtaining of treatment by complainants of sexual offences.”[11]

- The trial judge must provide written reasons for the decision.[12] The application, the evidence and the reasons for a determination cannot be published or shared with others, although the judge can decide to allow the publication of their reasons.

- The judge can decide to redact, release in part, impose restrictions on the viewing or use of the records, or any other condition necessary to protect the privacy of the complainant.[13]

- If the judge decides that the records should not be produced, the application ends but can be included in an appeal.

- The Supreme Court upheld these provisions in R v. Mills.[14]

The complainant has a right to participate and be represented by counsel at both stages of an application to access their private records.

“The more important issue is that complainants have lawyers to advocate strongly for them and outline these arguments clearly to the Judiciary.” [15]

Private Records in Possession of Accused (Admissibility)

If the accused wishes to adduce into evidence records about the complainant which are in the possession of the accused, the accused must comply with the two-stage procedure set out in the Criminal Code.

What kind of records are sought in these applications?

- Text messages between the accused and the survivor

- Text messages between the survivor and friends or family

- Diaries or journals of the survivor

- Correspondence from mutual friends, employers, professional colleagues or therapists

- Recordings of the complainant

This is not an exhaustive list*. The Court will consider whether the documents at issue are similar to these kinds of documents.

* See s. 278.1. of the Criminal Code

Stage One determines if the conditions for an admissibility hearing are met.

- A defence application to adduce records about the complainant in the possession of an accused must be made in writing, set out in detail the evidence the accused seeks to adduce and the relevance of that evidence to an issue at trial.

- This application must be provided to the Crown 7 days prior to a Stage Two hearing, although the trial judge has some discretion on the notice period.[16]

- A judge reviews the defence application, the Crown’s response and determines if the record is capable of being admissible under the statutory criteria of 276(2) or 278.92(2).

- If the judge agrees that the written application meets these criteria, the application goes to Stage Two. If the judge disagrees, the application ends.

- These applications can’t be published or shared with others. If oral submissions are made at Stage One, they are held in camera.

- The complainant does not have standing at this screening stage.

Stage Two is an in camera evidentiary hearing.

- Based on evidence presented at the hearing by the defence, Crown, and if they decide to give evidence, from the complainant,[17] the trial judge must determine whether the records sought by the defence meet the statutory criteria.

- The Criminal Code specifies these factors must be considered: “the potential prejudice to the complainant’s personal dignity and right of privacy” and “the right of the complainant and of every individual to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination” and “society’s interest in encouraging the obtaining of treatment by complainants of sexual offences.”[18]

- The trial judge must provide written reasons for the decision.[19] The reasons for an unsuccessful application cannot be published or shared with others, unless the judge allows it. The reasons for a successful application can be published.

- If the judge decides that the records cannot be used as evidence, the application ends but can be included in an appeal.

- The complainant has a right to participate and to be represented by counsel at Stage Two. Independent legal advice and representation for complainants in these applications is key.[20]

- The SCC upheld these provisions in R v. J.J.[21]

Proper administration of justice

Many tests in the Criminal Code require a consideration of whether this action or decision is “in the interests of the proper administration of justice.” See, for example,

- the criteria for admitting prior sexual history or the private records regime,1

- the standard for testimonial aids such as a support person, the exclusion of the public, publication bans,2

- the test for the publication of evidence at a preliminary inquiry,3 or

- the test for the use of video-recorded evidence.4

The CVBR indicates that consideration of the rights of victims of crime is in the interest of the proper administration of justice.5

1 Criminal Code, sections 276(2)(d), 278.92(2)(b)

2 Criminal Code, sections 486(1), 486.1(1), 486.5(1).

3 Criminal Code, section 537(1)(h)

4 Criminal Code, sections 715.1 and 715.2

5 Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, preamble.

Survivor therapeutic records contain personal information that many people would not want shared with anyone, particularly with the person who harmed them.

- They may mention prior sexual abuse by a different person or information about a miscarriage or an abortion.

- These records may reveal the deeply personal, physical, emotional, or mental state of a survivor following an assault.

- These records may reflect a survivor’s attempts to rebuild their health after an assault.

- They may contain information about economic or employment consequences after an assault.

- They may contain information about other people’s reactions to the assault, such as family, spouses, or children.

- They may reveal locations of safe houses or other places of safety for survivors.

Why therapeutic record subpoenas are problematic

- Therapeutic records are not verbatim reports of what the therapist said or what the survivor said.

- Therapeutic records are created for a different purpose; they were not created to be evidence for court.

- Therapeutic notes are not verified by survivors for accuracy.

- Therapy invites reflection and new ways of thinking about trauma.

- Counselling is subjective in nature.

- Allowing therapeutic records to be used as evidence denies survivors a safe place to heal.

Applying the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR)

One Court has specifically considered how the CVBR applies to the records regime. In R v. Mund, the Court found:

“In the hopes of redressing past injustices, the rights to privacy and psychological security of victims of crime have been explicitly protected in their own instrument, the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (herein after the CVBR).

Bestowed with quasi-constitutional status, the CVBR imposes that federal legislation, like the Criminal Code and the CEA, be applied in compliance with the statute and its enumerated rights.

The preamble of the CVBR affirms the importance of recognizing courtesy, compassion, and respect for the dignity of the victims as priorities throughout the criminal justice system. These values must guide litigants and deciders when navigating evidentiary provisions such as s. 278.1-278.9 of the Criminal Code. Just like these provisions have been enacted to protect the privacy and dignity of complainants and witnesses in sexual assaults procedures, the CVBR serves as a beacon of the society’s concern for the fair treatment of vulnerable persons who have been historically wronged by a merciless and overly legalistic justice system.” [22]

What we heard

Therapeutic records are distinct from other records

Survivors shared very personal reactions with our Office about how they felt when they found out the defence was asking for their counselling or therapy records. In fact, we encountered a clear disconnect between survivor experiences and stakeholder impressions. Some stakeholders believed that the private records regime in the Criminal Code strikes a balance between the privacy rights of complainants and the rights of the accused to a fair trial, and that the process – if applied properly – largely protects complainants. That was not what survivors experienced.

Survivors spoke clearly - counselling records are intimate and personal

“Even though I’ve heard people say counselling records could be ordered to be produced, I didn’t think it would happen because I didn’t think the records would be important for the trial. I haven’t read my counselling records, but my counselling sessions are mostly sobbing, talking about how I’m sleeping in my closet, hiding in my closet during the day, that I’m scared of everyone, that I’m phoning suicide crisis lines. I didn’t see how notes about that would ever be helpful to the person who raped me to defend themself in court.”

“I cannot overstate how hopeless I feel ever since the application was made. I never in a million years would have gone to counselling if I’d know this would happen. The ironic thing is that it was going to counselling that gave me the courage to report. So, I guess it’s probably more likely that if I had known, I would never in a million years have reported the rape.”

“I think it’s gross that the so-called justice system does this to victims of sexual crimes. Given the serious harm it does victims – which anyone who has any empathy would agree with – and given the minuscule chance counselling records would ever have something that’s helpful and necessary for the accused to defend themselves, it honestly feels to me like it’s just a state-sanctioned way to bully and intimidate and shame victims, the vast majority of whom are female, into regretting reporting and scaring them into begging the Crown to drop the charges. That’s what I am doing.”

“The decision about producing my records hasn’t been made yet. But if it orders them released, I will beg the Crown to drop the charges and say I won’t cooperate. I’m a dual citizen with [another country], and I will leave Canada permanently before I stay to have my so deeply, horribly personal counselling records handed over for a judge, Crown, defence counsel to read. It’s the record of the most awful, violent, scary, traumatic, life-altering thing that’s ever happened to me, and they might just get passed around.”

“I’ve never in my life done this before, but when I heard he was applying for my records I wanted to die. [Description of self-injury removed]. I spoke with two suicide crisis lines.”

“I did not feel like the process protected my dignity. Maybe my assumption is wrong, but I doubt victims of regular assaults or other non-sexual violent crimes often have defence counsel applying to get their counselling records.”[23]

Small changes to the definition of a record can protect complainants

A particular problem noted for us by several Crowns related to the definition of record – one Crown called this a “disturbing trend where judges find privacy interest is diminished when a complainant reports… that she was sexually assaulted.”

EXAMPLE A: A sexual assault examination kit (SAEK) records, on a specific forensic form, information gathered during an examination done by a qualified medical practitioner. The complainant must consent to that form being released to the police, even if a police investigation has already commenced. An Ontario case found that the SAEK was not a private record and that the nurse conducting the exam was part of the investigation of the sexual assault.[24] This meant that the complainant had no privacy interest in the SAEK. It would be automatically disclosed without consideration of the statutory factors.

- This is in stark contrast to how any other medical record would be viewed. Medical records, by any definition, are records to which a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy. Medical records are specifically included in the definition of a record for the private records regime.

- This decision puts more emphasis on where the information is written (a forensic form) compared to what the information is (facts about the complainant’s physical and mental integrity gathered during a medical examination).

EXAMPLE B: The proliferation of electronic records on personal devices is creating a mountain of records in sexual assault prosecutions. Because electronic communications and data are specifically noted in the definition of a record, Crown prosecutors must parse the contents of a phone to determine if each photo, message or data point contains personal information AND engages privacy interests of a complainant.[25]

- Personal information in the context of the records regime has been interpreted to mean, “intimate and personal details about oneself that go to one’s biographical core.”[26] The need for the record to go to a complainant’s biographical core is leading to many records being unprotected – such as a text between a parent and child or an email to a counsellor for which a reasonable expectation of privacy should be clear.

- This is in contrast to how data from an electronic device of the accused is treated. In R v. Marakah[27], (a firearms prosecution), the Supreme Court of Canada found that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in text messages they send and receive. The assessment is made on the totality of the circumstances – not made on each specific record.

EXAMPLE C: A related issue is the use of a motion for direction by defence counsel as a way to avoid the private records regime including the procedural protections for complainants and the balancing factors set out in the regime. Counsel will sometimes argue, in a motion for direction or at Stage One of an application, that a particular document does not meet the definition of record in s.278.1 and therefore is admissible without further screening. This determination turns on whether the information in question is “personal information” relating to the complainant, and whether the complainant has a reasonable expectation of privacy in that information or record.

- The Criminal Code could provide that, where a motion for direction or a Stage One hearing engages the privacy interests of complainants, complainants are entitled to participate and be represented.

- Counsel pointed us to obvious examples where a reasonable person would expect privacy protections, such as a text from a child to a parent or an email to a counsellor seeking urgent treatment.

The possibility of access to therapeutic records causes foreseeable harm to survivors

Sexual violence increases the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicide. Therapeutic interventions can help.

PTSD can occur in the aftermath of a sexual assault and can be severe.[28] Knowing the perpetrator, prior experiences of physical or sexual dating violence, stalking, or witnessing violence between parents can increase the likelihood of PTSD symptoms from sexual assault.[29] PTSD increases the risk of suicide, particularly for women.[30]

Survivors may experience higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.[31] Experiencing sexual violence from an intimate partner, childhood sexual abuse, and sexual assault increase the chances of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.[32]

- The risk is higher for people who identify as 2SLGBTQI+ or who have been exposed to suicide mortality.[33]

- Sexual violence against children increases the likelihood of psychiatric disorders, substance use, sexually transmitted infections, unwanted pregnancies, and suicide.[34]

Social isolation can further heighten the risk of suicidal ideation.[35] Young adults who are racialized and gender minorities are at an increased risk both of experiencing sexual violence and of suicidal thoughts and behaviours.[36] One study demonstrated that suicidal ideation was almost 3 times higher for female post-secondary survivors of sexual assault.

Suicide attempts have social and economic costs. Justice Canada estimates that in 2009, Canada spent $5,447,740 on medical responses to suicide attempts by non-spousal, adult survivors of sexual assault and other sexual offences.[37] Adjusting for population and inflation, in 2024, this could be as high as $9.1 million[38] without accounting for a slight decrease in police-reported rates of sexual assault and slight increase in the crime severity index since 2009.[39] Since we know that sexual violence also occurs between intimate partners and within spousal relationships, this figure is likely much higher. Even so, the most significant cost is to survivors and those who care about them.

Therapeutic interventions can help. Therapeutic interventions with survivors of sexual violence can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms, depression, and the risk of suicide.[40] Multiple psychotherapy treatments can reduce PTSD and mitigate short- and long-term negative impacts to mental health.[41]

- Access to evidence-informed mental health care can help people receive treatment and support before they become suicidal.[42]

- Access to mental health care can prevent suicide and save lives.[43]

Therapeutic interventions are in the public interest. Former Chief Justice McLachlin noted

- “Victims of sexual abuse often suffer serious trauma, which, left untreated, may mar their entire lives. It is widely accepted that it is in the interests of the victim and society that such help be obtained. The mental health of the citizenry, no less than its physical health, is a public good of great importance. Just as it is in the interest of the sexual abuse victim to be restored to full and healthy functioning, so it is in the interest of the public that she take her place as a healthy and productive member of society.”[44]

Sexual assault increases the risk of suicide for survivors.[45] Invasive investigations and aggressive cross-examinations make some survivors want to die.[46]

Most sexual assaults are perpetrated by a person known to the survivor.[47] Survivors told us that the accused’s access to their therapy records was another form of manipulation and control. These records, and the application to obtain them, require victims to have their personal life opened to strangers (the judge, court staff, Crown, defence) and provide intimate knowledge to the accused. If the application is successful, the information may become public knowledge.

While some survivors were angry at the accused for requesting their records, most of the anger we heard over these applications was not directed towards the accused, but to the criminal justice system itself for allowing survivors to be further exploited. Many survivors felt like they had to choose between justice or their own mental health.

“I wished I hadn’t gone to counselling. When I told the Crown, they dismissed my concerns and said counselling is important. Sure, but not having my former partner get to know about my most private thoughts is more important to me. When I [told my counsellor] I didn’t feel comfortable talking about the assaults anymore because of the records being disclosed, they suggested I tell the Crown I would no longer cooperate and try to convince them to drop the charges. It’s extremely important to me that the person who assaulted me faces consequences. I don’t want charges dropped. This convinced me the system really is unjust and the rights of the perpetrators are treated as far more important than the rights of their victims.”[48]

Just the possibility of therapeutic records being disclosed was sufficient to cut survivors off from access to life-affirming care.

In R v. J.J., the Supreme Court acknowledged that, historically, complainants could “expect to the minutiae of their lives and character unjustifiably scrutinized in an attempt to intimidate and embarrass them, and call their credibility into question.”[49] This is still the case.

- We heard that the complexity of the records regime itself is used to intimidate complainants into dropping charges.

- Threatening to access counselling records and initiating a hearing before a judge has a profound destabilizing impact on survivors.

- Multiple survivors told us, before a stage one hearing, they wanted to die, did not feel like it was safe to access mental health care, and asked the Crown to stay the charges.

“I feel like I’m the one suffering all the consequences… I have never been so depressed and wanting to die as when I found out they were applying for my records. I have given serious thought to either killing myself or disappearing. And never felt so keenly how unjust the legal system is that this is acceptable to do to victims, when what value do the counselling records actually provide? I will never report another crime. If other victims ask me, I will tell them they shouldn’t either.”[50]

Judges are familiar with the suicide risk to survivors. We reviewed available sentencing decisions for sexual offences in 2024 (n = 294) using the Westlaw Canada database to identify judicial mention of suicide risks to survivors.[51]

- 13% of sentencing decisions for sexual offences in 2024 included judicial mention of the survivor having thoughts of suicide or making attempts to die by suicide (39 of 294 available sentencing decisions). In most cases, the judge noted the suicide risk based on content provided in victim impact statements.

- This is likely an underestimate of the suicide risk to survivors since 31% of sentencing decisions in 2024 did not include victim impact statements, not all survivors who experienced suicide risk would have mentioned it in their statements, and judges may not always mention the risk when it is included in the victim impact statement.

- In addition to the 39 cases identified, judges often cited R v. Friesen[52] in sentencing decisions for sexual offences against children to acknowledge the wider harms of childhood sexual abuse, including an increased risk of suicide.

Stakeholder survey

Based on early interviews with survivors, we added some targeted questions to our stakeholder survey for counsellors or therapeutic support programs about what they observed when survivors’ therapeutic records were subpoenaed. A total of 38 therapists or service providers shared what they had observed in the past 5 years:

- 3 in 4 survivors regretted reporting sexual violence (76%)

- 1 in 2 survivors disclosed having thoughts of suicide (57%)

- 1 in 3 survivors withdrew from therapy or the support program (37%)

- 1 in 20 survivors felt protected by the criminal justice system (5%)[53]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Therapists told us that when the criminal justice system allows disclosure of therapeutic records, it is harmful to the mental health of survivors. Therapists reported that survivors withdrew from therapy, disclosed thoughts of suicide, and regretted reporting sexual violence. This places survivors at risk and compromises society’s trust in the criminal justice system.

Therapists reported that the threat of disclosure of their records made treatment less effective. It compromises the quality of notetaking to support sessions, violates the therapeutic relationship, takes time away from providing services to other survivors, and co-opts the therapy process to extend the impact of abusers. The continued risk also compromises quality of care to survivors who choose not to report.

Therapists and service providers said:

“Knowing that our records could be subpoenaed requires that we write our records extremely vaguely to ensure that there is nothing an ex-partner's lawyer could use against the client. It's frustrating because we must be vague almost to the point of the notes being difficult to follow, with a lot of relevant information omitted to protect the client.”[54]

“These requests take time and resources away from providing services for victims.”[55]

“The threat of subpoenas prevents good work from happening in terms of treatment and processing. Both the client and the therapist are reluctant to engage meaningfully.”[56]

“Requests are often made maliciously in an attempt by the abuser to further their power and control which makes the justice system another tool in their toolkit of abuse and violence.”[57]

“Survivors feel exposed and feel as though their suffering is now on display for the world to see. They also feel like it is a continuation of abuse from the abuser due to an infringement into their very personal life. Feel reduced safety. Breakdown in trust. If their counselling records are not safe and are ways that accused persons may use to humiliate or control the survivor.”[58]

Service providers whose records were subpoenaed also experienced distress. We asked therapists and service providers who had client records subpoenaed in the past 5 years to provide a subjective rating from 0 to 10 to describe the mental impact on clients and on themselves as helpers. A score of 0 represented no negative impact on mental health, and a score of 10 represented a very significant negative impact on mental health.

- Therapists and service providers indicated that subpoenas for therapy records have a significant negative mental health impact on survivors and on themselves.

- On a scale of 0 to 10 measuring subjective levels of distress, there was less than one point of difference in the score they attributed to survivors (7.71) and to themselves (7.03).[59] (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

In qualitative responses, we heard that many therapists felt like it damaged the therapeutic alliance, and they worried about the possible negative impact on survivors going through the criminal justice system.

- “I had my records subpoenaed and it was incredibly stressful. I felt so much worry about what I wrote and how that could be construed and thinking how that could impact the client. It also felt incredibly invasive, I felt like I would be under a microscope.”[60]

- “I didn't know if I might be penalized by the court for not bringing the records, if the court would compel me to produce them, or if my organization would back me with any potential consequences. I did not want to unintentionally do or say anything to cause harm to my client or the court case.”[61]

- “Gives rise to concern that a mistake may have been made, or you may have disclosed "too much” about a client's emotions/feelings in service notes. This creates fear that your documentation is going to have a detrimental impact on the client when they are crossed examined.”[62]

Many therapists or service providers contest records applications

“Protecting survivor records is a priority for our agency. Fighting these subpoenas has come at a great financial cost to our organization, which ultimately impacts our direct services. Further, it causes significant stress for our management team.” [63]

Therapists and other service providers felt like providing their records to the court was an ethical violation. Providers that worked within larger government-run agencies would disclose information as requested, but many more independent or community-based care providers fought against disclosure in court.

- In our study, 31 providers estimated they had received a total of more than 116 record applications in the past 5 years.

Costs associated with fighting record applications. Stakeholders whose records had been subpoenaed in the past 5 years reported legal costs that ranged from $0 where pro bono services were offered, up to $20,000 for one agency.

- For private therapists, responding to records applications is uncompensated time that directly affects their ability to provide for their family financially. The time involved getting legal advice, preparing documents, complying with court orders and attending court makes a therapist unavailable for counselling sessions, eliminating income and indirectly extending harm to others seeking urgent support for their mental health.[64]

Expenses for service providers:

- Sexual assault centres and therapists pay legal fees to contest third party applications for counselling records in court. We heard that some centres pay $2000-$5000 in legal fees annually. Money for legal fees takes away from core services for survivors.[65]

- In some of these cases, sexual assault centres are not keeping records because of the risk of subpoenas but will still pay legal fees to contest a records application because they believe survivors deserve safe spaces to heal that are not exploited by their abuser.[66]

- One private therapist had records for multiple clients subpoenaed in the same case, and they were also subpoenaed to testify. Preparing documents, getting legal advice, preparing for trial and attending court cost them a month’s worth of time with no billable hours, destabilizing family income and ability to provide for their family[67]

Therapists believed their records should be better protected. They believed, when therapeutic records are disclosed, what survivors share in therapy is twisted and used against the survivor.

“I believe strongly that the therapy records of clients must remain confidential. If there is anything that arises that indicates someone is at risk for harm, therapists are ethically required to report to the most appropriate authorities. Confidential therapy records should not be used in a court of law to discredit or downplay a violent attack or IPV. No one deserves to be abused.”[68]

Abusive use of counselling records in cross-examination

One Crown prosecutor shared that a complainant was cross-examined about a dream she had shared with her therapist about the sexual assault. In the dream she was experiencing self-blame and had shared these feelings in a therapeutic setting. She was cross-examined about the dream and its differences with her testimony.

There is clear evidence of a chilling effect

In our investigation, many stakeholders did not believe the private records production and admissibility regimes fully achieves their purposes.

Stakeholder survey

We heard that 47% of stakeholders disagreed that the records regimes effectively promote society’s interest in encouraging victims of sexual offences to come forward and report to police.

- 68% of mental health professionals (n = 44) and 61% of sexual assault centres (n = 36) disagreed that the records regimes encourage victims to come forward and report. These perspectives are important because many survivors talk to sexual assault centres and therapists about sexual offences – and do not report those offences to police or anyone else!

- 40% of Crown attorneys agreed (n = 103) that the records regimes help survivors to come forward, but 73% of defence attorneys disagreed (n = 11).[69]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Protection of records. Stakeholders had divergent views on whether counselling or therapy records are adequately protected under the current law.

- An equal percentage agreed and disagreed (35%)

- People working within the system were more likely to believe the law protected records, such as defence attorneys (70%), Crown (61%), and police (40%).

- Stakeholders working directly with survivors were more likely to disagree that the law protected records, such as sexual assault centres (48%) and mental health professionals (45%).

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Relevance of records. Overall, stakeholders were more likely to disagree that counselling or therapy records provide valuable evidence in sexual violence trials – 52% of stakeholders disagreed vs. 21% who agreed (n = 385).

- Since the use of records in a trial is directly related to the work of defence and Crown attorneys, it is valuable to note that only 18% of defence counsel (n = 11) and 8% of Crown attorneys (n = 103) agreed that counselling or therapy records provide valuable evidence.

- This result raises the question of the balancing of the clear harms to survivors compared to the benefits to accused persons.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Seeking treatment. In our investigation, 42% of stakeholders disagreed that the records production and admissibility regimes effectively promote society’s interest in encouraging victims of sexual offences to seek treatment vs. 23% who agreed.

- 59% of mental health professionals (n = 44) and 52% of sexual assault centres (n = 37) disagreed that the records production and admissibility regimes encourage victims to come forward and report. These perspectives are important because sexual assault centres and therapists regularly witness how survivors are harmed when they are told their therapy records may be subpoenaed.

- Slightly more Crown attorneys (n = 102) disagreed (36%) than agreed (31%) that the records regime encourages survivors to access treatment, while 73% of defence counsel disagreed (n = 11).

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Chilling effect on survivors. Even with the records production and admissibility records regime, survivors reported having to choose between access to mental health services and access to justice.

- Some survivors receive advice from service providers, other survivors, police, Crown attorneys, or independent legal advice (ILA) not to speak with a counsellor because their records could be subpoenaed (12%) or their therapist could be called to testify in court (11%). An equivalent proportion of survivors (11%) said that the existing protections in law were explained to them (n = 973).

- 187 survivors (20%) wanted to speak with a counsellor but felt like they couldn’t because their counselling record could be subpoenaed.

- 129 survivors (13%) chose not to report a sexual offence to the police because they wanted access to counselling.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Tracking the chilling effect over time. There is limited data available on applications for survivor counselling records. Previous reviews of case law have concluded that it is difficult to determine whether these applications are standard practice for defence and how frequently records are produced to the judge or disclosed to defence.[70] However:

- An older review of cases from December 1999 to June 2003 found that the majority of records applications included a request for counselling records (23%), women were more likely to have counselling records subpoenaed, and of the cases deemed relevant, records were produced to the judge in 63% of cases, with full or partial disclosure to defence in 35% of cases.[71]

- A study of the records regime done in 2008[72] found that certain categories of vulnerable complainants, especially women and children, may be most at risk of having their records accessed in trials. This includes children under the care of child welfare authorities, women with mental health histories or disabilities, Indigenous women, and immigrant and racialized women. The study also found that most Canadian sexual assault centres have adopted minimal record-keeping practices in response to disclosure applications.

In our survivor survey, we observed an increase over time in the percentage of survivors who felt like they could not access counselling or did not report to police because their records could be subpoenaed and an increase in the percentage of survivors whose records were eventually subpoenaed. The following table provides survivor responses based on a year of the last incident of sexual violence. (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

If we narrow our data to include only survivors who reported sexual violence to police, and filter by year of last contact with the criminal justice system, 1 in 4 survivors in contact with the criminal justice system in 2020 or later felt like they could not speak with a counsellor and 1 in 10 had their counselling records subpoenaed. (Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Because of the private records regime, we know that there are more attempts to access survivor therapy records than what the courts permit. Requests must satisfy a two-stage test before they can be produced to the defence and satisfy a second two-stage process before the records can be used by the defence as evidence – but they are subpoenaed from a record-holder in order to conduct this two-stage test. We also heard testimony from survivors that private record applications can be used to intimidate and embarrass complainants: this is exactly the SCC observation in R v. J.J.[73]

For survivors whose cases proceeded to court (n = 116):

- 1 in 3 survivors said defence wanted to raise prior sexual history (32%).

- 1 in 4 survivors said defence wanted to access private records (24%).

- 1 in 5 survivors said defence wanted to access their counselling records (22%).

Cases occurring in 2020 or later. The increase in defence applications is even more clear in recent cases. When we filter those responses by year of last contact with the criminal justice system, all indicators are higher in cases that ended in 2020 or later (n = 64):

- 34% of survivors said defence wanted to raise prior sexual history

- 29% of survivors said defence wanted to access their counselling records or other private records

The R v. Jordan timelines, combined with the record regimes, puts survivors in an untenable position[74]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Parliament has created the sexual history and records production and admissibility regimes with the goal of protecting sexual assault complainants. Since then, the SCC imposed numerical timelines for the prosecution of all criminal offences in R v. Jordan.

- The arbitrariness of the Jordan timelines means that, when the protections of the records regimes are applied, there is a greater likelihood that a case will be stayed, causing greater harm to survivors and compromising the purpose of these regimes.[75]

“All of these amendments were a much-needed change, and they have done a lot to protect survivors’ privacy and dignity. Unfortunately, the increase in the number of these motions and the increase in complexity of these motions causes a lot of delay in the court system. As a result, it can be difficult for the court to provide sufficient resources for these cases so that they can be completed within the timeframe imposed by R v. Jordan. Given how much courage it takes for survivors to come forward in the first place, it is devastating for survivors when charges are stayed as a result of the R v. Jordan decision.” [76]

We heard from Crown attorneys across Canada that these protections, and particularly the record screening regime, have resulted in multistage pre-trial motions being required on many sexual violence prosecutions.[77] Jurisdictions that have been disproportionately affected by R v. Jordan offer survivors less protection.

“For expediency, the judiciary is often skipping step 1 due to lack of time and resources. The gatekeeper function is almost nonexistent. This leads to complainants being forced to hire counsel and lengthy hearings being conducted which cause unnecessary stress on victims of sexual violence (fearing their personal records will be disclosed) and puts significant pressure on our justice system as these hearings and decisions are lengthy.” [78]

One proposal to us was to allow case management judges to deal with sexual history and private records applications. This would encourage early attention and scheduling of these applications and allow specialized expertise to develop among the case management judiciary.

In one stakeholder interview, a senior prosecutor said that trying to impose Jordan timelines on sexual assault cases where the SCC has recognized the need for extra protections is unreasonable and continues to reinforce gender inequality. They said it does not make sense to allocate the same amount of time to car theft as to sexual assault, when the legal obligations to survivors of sexual violence will predictably take more time. This increases the risk that cases for gender-based crime will be stayed under R v. Jordan.[79]

Another senior prosecutor noted that “I believe the focus should be about effective case management of sex assault cases and ensuring lawyers follow timelines as much as possible rather than focusing on how complex and time consuming, they make the process. Complainants should not have to choose between exercising their rights to privacy, equality and dignity as well as having their own lawyer argue for these rights versus having their trial proceed within the Jordan timelines.”[80]

“Free legal representation, especially in cases of therapy records, is vital to protect the dignity, equality and privacy rights of an individual survivor/complainant.”[81]

Another prosecutor noted that these protections are being well managed within her jurisdiction.[82] “If they are identified early in the process and effectively managed by judicial pre-trials and case management conferences, there is no reason that they cannot be adjudicated within the timelines established by Jordan. Generally, these are pre-trial applications that should be decided ahead of the trial and the real problems arise when they are brought mid-trial, especially in jury trials.”[83]

Mid-trial applications

We heard, very clearly, from Crowns and survivors about the harmful impact of mid-trial applications to obtain private records.

“Mid trial applications cause a lot of harm and often make survivors/complainants have to make hard choices. These types of applications should be avoided at all costs and defence counsel should be taken to task by the Judiciary and not allowed unless something new has arisen and it cannot have been anticipated.” [84]

These applications introduced significant delays and increased the risk of an application for a stay of proceedings. We also heard that mid-trial applications in a jury trial increased the risk of a mistrial.[85] Some survivors and stakeholders felt like this was an intentional defence strategy.[86]

Mid-trial applications have serious impacts on survivors under oath/affirmation.[87] Whether personal records applications are allowed or not, the mid-trial application harm survivors. There are multiple steps to these applications, and the complainant may be under oath when the application is presented and could be for weeks or months while this application is under way. When they are under oath, complainants:

- Cannot discuss anything with therapists, friends, or family.

- Could experience physical and psychological distress in preparing to testify (twice).

- Would be unable to ask questions to the Crown during the application time.

Essentially, complainants are effectively isolated – just when they need assistance.

We also heard:

- Crowns may hesitate to communicate or limit communication with the complainant.

- Family and friends’ life circumstances are negatively impacted.

- A prolonged delay is also not realistic for a jury trial.[88]

The harm to survivors happens whether or not the records application is successful - the harm comes from the application and the delay caused by a mid-trial application. These impacts could affect the complainant’s mental health significantly, along with any impacts on their dependants and employment.

Case study – Harmful impact of mid-trial applications on survivor

“This motion was not made in advance in either of my cases, instead defence brought it up as a delay tactic after I was sworn in. A motion was made for counselling records, and I was left sworn in.

I was advised by the judge not to discuss case details with my psychologist or another person until I finished testimony. I could not access therapy to discuss flashbacks, cross-examination, ongoing PTSD for over eight months while the 278.1 was processed.

This process happened to me twice [before I turned 18], with separate defence attorneys. Both waited until I was on stand at trial and sworn in. These motions ARE BEING USED TO DELAY.

My therapist was dismissed and her letter of recommendation for accommodations was entirely ignored and the defence laughed at her when she came in person. My psychologist and I both cried in the courthouse parking lot.”[89]

The increased burden of applications

Many stakeholders believed that applications to introduce other sexual history or to obtain private records were a significant cause of delays in the court system. One Crown suggested it was the primary reason the “system is clogged.” [90]

- We heard that in some jurisdictions, it was standard practice or almost “automatic” for defence counsel in sexual offences to seek therapeutic records, while stakeholders in other jurisdictions said it is quite rare for defence to request counselling records.[91]

- The increase in mid-trial applications and excessive volume of electronic records was the focus of a working group within the Uniform Law Conference Canada.[92]

Overall, we heard that disclosure requests and production orders for different types of records have increased exponentially. This has led to shortcuts to stay within R v. Jordan timelines. Crown attorneys and defence spoke about the significant volume of digital evidence being sought, including text messages, emails, and many other electronic records. One Crown attorney (who was previously a defence attorney) described this as a strategic move:

"I used to do a lot of wiretap cases. And often the name of the game in big complex criminal defence is to make the file as complicated as possible for the Crown so that it collapses under its own weight. I believe defence counsel are now adopting that same strategy in a lot of sexual violence cases, because of a lot of the special rules, and how flexible they are, and how everything requires a specific case analysis. It's really easy to derail these prosecutions and make them far more complex. What would have been a two-witness trial 10 years ago is now a one-week jury trial with multiple days of pretrial motions, and probably an adjournment that surprises you somewhere in there.” [93]

Defence counsel agreed that the records regime is a significant factor in delays in the criminal justice system.

- One person noted that the preponderance of electronic communications (texts, video, chats, emails, voice memos, social media posts) has exacerbated the complexity of the private records regimes.

- Some defence counsel felt that a victim advocate may help to reduce delays associated with records applications by offering advice about when to consent to the release of the records or helping to explain the complexity of the regime.[94]

- Defence counsel noted that it is challenging to schedule new dates for defence, Crown, and complainant’s counsel in mid-trial applications.[95]

- One representative of the defence bar felt that it is possible some defence counsel act unethically and use records applications to run the Jordan clock, but she explained that defence counsel are also conscious of their liability for unhelpful applications. In addition, she noted that a records application will expose the accused person to the possibility of testimony and cross-examination on the application.[96]

Evidence of a Survivor’s Sexual Inactivity

In 2025, the Supreme Court of Canada considered a case where the Crown had relied on the complainant’s evidence of a disinterest in sexual relationships.[97] The Court was concerned about inverse twin myth reasoning and held that evidence of a complaint’s sexual inactivity was also governed by the common law procedures governing Crown-led sexual history – effectively mirroring the section 276 regime. The Court said that evidence of sexual inactivity is part a survivor’s sexual history and is therefore presumptively inadmissible.

- This decision reverses prior appeal Court decisions in Alberta and Ontario.[98] This decision creates a requirement for a Crown Seaboyer[99] application in order to adduce sexual inactivity evidence about a survivor, such as communications by the victim that she did not want to engage in sexual activity. This judgment is turning a requirement designed to protect victims into something that is designed to protect the accused and brings prejudice to the rights of victims.

These new requirements on Crowns in Crown-led sexual history applications and the requirement of two stages will contribute to delays in sexual assault cases, affecting the Jordan timelines.

- Seaboyer applications are in two stages. These additional steps will take additional Crown, defence and judicial time as well as courtroom time.

- Complainants are not automatically entitled to standing in Seaboyer applications, but judges can exercise their discretion to grant standing. This may require an additional court date to litigate whether the complainant should have standing prior to the second stage of a Seaboyer application.

- Survivors will want to have legal representation for these applications -which adds to possible scheduling challenges for the Court.

- Stage two of a Crown Seaboyer application will generally require a personal affidavit, which will most often come from the complainant. While the SCC says that this affidavit is not a requirement, they also say that the Crown’s application will have little chance of success without it.

- A personal affidavit from the survivor on this application exposes her to cross-examination on the pre-trial application. Crowns will often be in a situation of having to choose between exposing the victim to early and harmful cross-examination on the application, or forgoing calling evidence that would be helpful to the prosecution (and victim).

- Cross-examinations are one of the most stressful parts of a criminal trial for survivors – this decision has added another possible cross-examination for a survivor.

The records regimes need to better protect therapeutic records in order to protect survivors’ Charter rights

Even with added protections available to survivors in the sexual history, records production and admissibility regimes, we have heard that:

- Defence counsel routinely request or threaten to request private records, including therapeutic records, or to adduce sexual history evidence based on rape myths and stereotypes.

- The records production and admissibility regimes have not sufficiently limited the overbreadth of defence counsel applications for counselling records.

- The mental health consequences on survivors when their counselling records are requested or disclosed is undeniable.

Section 11(b) rights of the accused can’t be considered in isolation

In R v. Mills,[100] the Supreme Court of Canada made it clear that none of the principles at stake in third-party records application – full answer and defence, privacy, and equality – were absolute and capable of trumping the others.[101] The Court also held that conflict between these rights should be resolved by considering the conflicting rights in the factual context of each particular case. Finally, the Court noted that Charter rights are to be read expansively: the balancing of Charter rights happens in a section 1 analysis.

In R v. J.J., the Supreme Court considered the record admissibility regime and standing for victims on s. 276 applications. The Court explained that “Section 11(d) does not guarantee ‘the most favourable procedures imaginable’ for the accused, nor is it automatically breached whenever relevant evidence is excluded … an accused is not entitled to have procedures crafted that take only [their] interests into account. Still less [are they] entitled to procedures that would distort the truth-seeking function of a trial by permitting irrelevant and prejudicial material at trial… Nor is the broad principle of trial fairness assessed solely from the accused’s perspective. Crucially, as this Court stated in Mills, fairness is also assessed from the point of view of the complainant and community.”[102] [Emphasis added]

Are the rights of survivors to security of the person being infringed?

In Morgentaler 1 (1988)[103] the majority found, “State interference with bodily integrity and serious state-imposed psychological stress, at least in the criminal law context, constitutes a breach of security of the person.”

- Applying this lens to therapeutic records, the question is whether allowing therapeutic records to be used as evidence limits survivors’ access to care. We think that there is convincing evidence that it does.

In Canada vs. PHS,[104] the Supreme Court found that “Where a law creates a risk to health by preventing access to health care, a deprivation of the right to security of the person is made out.”[105]

- Our evidence shows that allowing an accused person to seek access to therapeutic records increase a survivor’s risk to health.

Are the equality rights of survivors being infringed?

The two‑step test for assessing a s. 15(1) Charter claim “requires the claimant to demonstrate that the impugned law or state action a) creates a distinction based on enumerated or analogous grounds, on its face or in its impact; and b) imposes a burden or denies a benefit in a manner that has the effect of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantage.”[106]

- This test also applies in cases of adverse impact discrimination, which “occurs when a seemingly neutral law has a disproportionate impact on members of groups protected on the basis of an enumerated or analogous ground.”[107]

Historically, women, and specifically marginalized women, were discriminated against when they alleged rape or sexual assault.[108] Myths, stereotypes, and prejudice were used to discredit and harass women who made allegations of rape.

- We believe that failing to protect therapeutic records intensifies privacy concerns and further disadvantages those who experience sexual assault.[109]

Why identity matters

Differential and intersecting impacts must also be considered for those who experience systemic discrimination.[110]

- Survivors who are heavily monitored and documented by systems, including Indigenous women, racialized women, women living in poverty, and women with disabilities, are more likely to be watched and recorded by systems. There are more records available about them – the more records available increases privacy risks and adds barriers to reporting.

- Those who have been victimized or traumatized in the past are more likely to see a counsellor, and therefore disproportionately impacted by these applications.

- Members of the 2SLGBTQI+ community are disproportionately victims of sexual assault.[111] The Canadian Mental Health Association found that between 2022 to 2023, these populations were more likely to have poorer mental health and to be accessing mental health services.[112] This puts these groups at an increased risk of having records that are then requested during the criminal justice process. Coupled with the high rates of sexual victimization of 2SLGBTQI+ community, these people are at increased risk from the misuse of the records regime.

Other countries are considering this issue

In January 2025, the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) released the final report from their inquiry Justice Responses to Sexual Violence. Many of their findings parallel our own.

The ALRC acknowledges that, prior to the inquiry, they believed that regimes to protect counselling records through judicial review balanced the protection of complainants with the rights of the accused. Based on the evidence they collected, they conclude that their private records regime:

- is not working effectively in practice

- does not effectively safeguard survivor access to therapy or society’s interest in reporting to police

- causes further harm and trauma to survivors

- adds time and cost to the justice system

They discussed whether counselling communication privilege should be qualified or absolute.

- “If applications to access material are frequently granted, and if the material (once accessed) is frequently and successfully used by the defence, then this may justify retention of a qualified privilege. However, if applications are rarely granted, and the material is rarely of use, this would tend against a qualified privilege and in favour of an absolute prohibition. The justification for exposing all people who have experienced sexual violence to this potential harm becomes less tenable.”[113] (Safe, Informed, Supported: Reforming Justice Responses to Sexual Violence, Australian Law Reform Commission, 2025 at p. 379)

In a significant shift from past decisions, the ALRC argues that an absolute may be appropriate, but that more data is needed on how the regime is functioning to properly assess the balance. They recommend that the Standing Council of Attorneys-General consider whether sexual assault counselling communications should be absolutely privileged or admissible with leave of the court.

Options for Reform. We heard that the harms to survivors from the records regimes are so severe that the threshold to access therapeutic records should be nothing less than the protections provided to solicitor-client or informant privilege. “The privilege should be infringed only where core issues going to the guilt of the accused are involved and there is a genuine risk of a wrongful conviction.[114] A stakeholder said,

"If we truly wanted to provide protection [for] counselling records, they should be protected with the same level as lawyer-client privilege. These records are often thoughts and emotions of the survivor during a traumatic time and should not be entered as evidence."[115]

Independent Systemic Review in British Columbia: In June 2025, British Columbia published the final report from an independent systemic review into the legal system’s treatment of intimate partner violence and sexual violence. Dr. Kim Stanton came to similar conclusions about the way private records are being abused in the system, and the need to better protect therapy records:

“The Review heard considerable concern from support workers and lawyers that there is a rising use of third-party records applications by men who use violence as a further form of control and abuse. The Ministry of Attorney General, in consultation with relevant experts, should consider whether a form of presumptive evidentiary privilege (sometimes called a class privilege) could be extended through legislation to safeguard confidentiality of communications between survivors and crisis workers in order to thwart the weaponizing of records applications in cases of gender-based violence.”[116]

We also heard from feminist legal academics and leading advocates that there should be an absolute prohibition on the use of therapeutic records in the prosecution of sexual violence offences.

- They argue that this prohibition would reflect the SCC directions that sexual violence prosecutions should not require complainants to submit the minutiae of their lives to public scrutiny and the evolution in society that values the mental health and healing of complainants.

The criminal justice system is using women (overwhelmingly victims of sexual assault) to achieve the societal goal of preventing crime, encouraging reporting of crime, and responding to crime.

- We believe that the goal is not being met by the system (preventing crime, encouraging reporting, responding to crime) because it discourages reporting, increases harm and risk of harm.

In R v. J.J., one of the most recent Supreme Court cases on the private records regime, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Moldaver delivered the majority judgment:

[1] The criminal trial process can be invasive, humiliating, and degrading for victims of sexual offences, in part because myths and stereotypes continue to haunt the criminal justice system. Historically, trials provided few if any protections for complainants. More often than not, they could expect to have the minutiae of their lives and character unjustifiably scrutinized in an attempt to intimidate and embarrass them and call their credibility into question — all of which jeopardized the truth-seeking function of the trial. It also undermined the dignity, equality, and privacy of those who had the courage to lay a complaint and undergo the rigours of a public trial.

[2] Over the past decades, Parliament has made a number of changes to trial procedure, attempting to balance the accused’s right to a fair trial; the complainant’s dignity, equality, and privacy; and the public’s interest in the search for truth. This effort is ongoing, but statistics and well-documented complainant accounts continue to paint a bleak picture. Most victims of sexual offences do not report such crimes; and for those that do, only a fraction of reported offences result in a completed prosecution. More needs to be done.

The OFOVC has been calling for reforms to the records regime

In November 2024 in a submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women on their Gender-based Violence and Femicides against Women, Girls, and Gender Diverse People study,[117] we shared issues with accessing therapeutic records including causing delays and preventing survivors from accessing mental health support.[118]

In May 2024, we were part of the Survivor Safety Matters’ joint press conference with members Alexa Barkley and Tanya Couch, calling attention to the need for urgent reform of section 278.1 of the Criminal Code (see Annex D for Survivor Safety Matters’ Proposed Amendments for s.278 of the Criminal Code). This systemic investigation was also highlighted in the Ombud’s remarks.[119]

We highlighted problems with the records regime in a February 2024 submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights.[120]

In 2011, the Ombuds made recommendations to the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on their study of a Statutory Review on the Provisions and Operation of the Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Production of records in sexual offence proceedings). The final report included recommendations for better research into the effectiveness of records regime, looking at data from survivors compared to proceedings and lack of reporting, and changing legislation to ensure judges tell victims about their entitlement to independent counsel in records applications.

TAKEAWAY

A just system ensures survivors have access to therapy

and that asking for help is not used against them

Justice must ensure private healing is not public evidence

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Interview #461

[2] Based on a review of 294 available 2024 sentencing decisions for sexual offences in the Westlaw Canada database.

[3] In this chapter, we are using the term therapeutic records to include psychiatric records, psychological records, counselling records and therapeutic records related to treatment after sexual violence.

[4] R v. Barton, 2019 SCC 33 (CanLII)

[5] Input from Justice Canada, July 23, 2025.

[6] R v. Darrach, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 443 (SCC 2000‑46).

[7] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s 276(3).

[8] A third party can mean a counsellor, an employer, a private company (such as a pharmacist, a ride-share service), the Crown or the police.

[9] Donkers H. (2018). An Analysis of Third Party Record Applications Under the Mills Scheme, 2012-2017: The Right to Full Answer and Defence versus Rights to Privacy and Equality. CanLIIDocs 192.

[10] R v. J.J., 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII)

[11] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s. 278.5(2)

[12] Ducket, M., & Ruzicka, L. (2014). Applications in sexual assault offence cases: Third party records, Section 276, Records in the possession of the accused. Law Society of the Northwest Territories.

[13] This is not an exhaustive list of the conditions which a judge can put on the record to protect the complainant’s privacy and security.

[14] R v. Mills, 1999 CanLII 637 (SCC)

[15] Submission to the OFOVC, July 23, 2025.

[16] In 2018, FPT Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety recommended extending the application from 7 days to 30 days to provide more time for complainants to access legal advice or representation. Federal-Provincial-Territorial Meeting of the Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety. (2018). Reporting, investigation and prosecuting sexual assaults committed against adults: Challenges and promising practices in enhancing access to justice for victims.

[17] Criminal Code, section 278.994(2) which was discussed in R v. J.J. (2022) SCC 28 (CanLII), at para 176-179

[18] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s. 278.92(3)(c), (g), (h).

[19] Ducket, M., & Ruzicka, L. (2014). Applications in sexual assault offence cases: Third party records, Section 276, Records in the possession of the accused. Law Society of the Northwest Territories.

[20] See our chapter on Enforceable Rights for more about independent legal advice and independent legal representation.

[21] R v. J.J., 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII)

[22] R v. Mund (2024) QCCQ 5149, at para 68-70

[23] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #192

[24] R v. T.S. 2021 ONCJ 299 (CanLII)

[25] R v. J.J. 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII)

[26] R v. J.J. 2022 SCC 28 (CanLII), at para 44

[27] R v. Marakah 2017 SCC 59

[28] Meta-analysis of 22 studies. Dworkin, E. R., Jaffe, A. E., Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2021). PTSD in the year following sexual assault: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 497-514.

[29] Du Mont, J., Johnson, H., & Hill, C. (2019). Factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptomology among women who have experienced sexual assault in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17-18), NP9777-NP9795.

[30] Fox, V., Dalman, C., Dal, H., Hollander, A. C., Kirkbride, J. B., & Pitman, A. (2021). Suicide risk in people with post-traumatic stress disorder: A cohort study of 3.1 million people in Sweden. Journal of affective disorders, 279, 609–616.

[31] Review of 25 studies, reflecting N = 88,367 participants. Dworkin, E. R., DeCou, C. R., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2022). Associations between sexual assault and suicidal thoughts and behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 14(7), 1208-1211.

[32] Review of 46 meta-analyses. Na, P. J., Shin, J., Kwak, H. R., Lee, J., Jester, D. J., Bandara, P., Kim, J. Y., Moutier, C. Y., Pietrzak, R. H., Oquendo, M. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2025). Social Determinants of health and suicide-related outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry, 82(4), 337.

[33] Meta-analysis of 165 studies including 958,000 children from 80 countries. Piolanti, A., Schmid, I.E., Fiderer, F.J., Ward, C.L., Stöckl, H., Foran, H.M. (2025). Global prevalence of sexual violence against children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 179(3), 264–272.

[34] Piolanti, A., Schmid, I.E., Fiderer, F.J., Ward, C.L., Stöckl, H., Foran, H.M. (2025). Global prevalence of sexual violence against children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 179(3), 264–272.

[35] Oh, S., Banawa, R., Keum, B. T., & Zhou, S. (2025). Suicidal behaviors associated with psychosocial stressors and substance use among a national sample of Asian American college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 372, 540-547.

[36] Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental Health. (n. d.) Suicidality and Sexual Violence Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental Health

[37] Hoddenbagh, J., Zhang, T., & McDonald, S. (2021). An estimation of the economic impact of violent victimization in Canada, 2009. Department of Justice Canada.