West Nile virus and other mosquito-borne diseases surveillance report: Annual edition 2020

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.59 MB, 12 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2023-06-02

On this page

- Surveillance highlights

- Introduction

- Methods

- West Nile virus

- California serogroup viruses

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- Discussion

- Public health conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

Surveillance highlights

West Nile virus

- A total of 166 human cases of West Nile virus (WNV) were reported, 163 cases were acquired within Canada (153 clinical cases and 10 asymptomatic cases).

- Of the 153 WNV clinical cases: 37% were neurological, 33% were non-neurological and 30% were unclassified. Seven WNV-associated deaths were reported.

- 205 WNV-positive mosquito pools were reported. The percentage of mosquito pools positive for WNV increased in 2020 (1.2%) compared to 2019 (0.8%).

Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- 8 equine cases of EEE were reported.

California serogroup viruses

- A total of 13 human California serogroup (CSG) virus infections were reported: 2 from the National Microbiology Laboratory and 11 from Québec.

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV), Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus, and the California serogroup (CSG) viruses, specifically the Jamestown Canyon and snowshoe hare virus, are known to cause human infection in North AmericaFootnote 1. All four mosquito-borne diseases are endemic in parts of CanadaFootnote 2. In Canada, the incidence of most of these endemic mosquito-borne diseases in humans has increased by approximately 10% over the last 20 years, which is largely attributed to climate changeFootnote 2. To characterize the incidence and spread of mosquito-borne diseases among people and animals, the West Nile virus surveillance system has adopted a One Health approach involving experts from human, animal and environmental domains. This report integrates and describes surveillance data on human, mosquito, bird and other animal cases submitted by various partners, including participating provincial/territorial governments and non-governmental organizations.

Methods

WNV has been a nationally notifiable disease since 2003, and human cases of WNV in Canada are reported voluntarily by provincial/territorial public health authorities to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Other agencies such as Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec also report human infections of WNV in Canada via provincial and territorial health ministries.

Unlike WNV, CSG viruses and EEE virus infections in humans are not nationally notifiable diseases in Canada. Some provincial/territorial laboratory partners perform their own testing and there may be differences among their respective case definitions, which can lead to discrepancies in reported numbers. In addition, when requested by other laboratories, the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) within PHAC tests for EEE virus and CSG viruses in patients who present with symptoms consistent with an arboviral infectionFootnote 2.

In this report, human WNV cases were classified using the national WNV surveillance case definition and included both clinical (probable and confirmed) and asymptomatic cases. Of note, Saskatchewan reports WNV neurological syndrome cases only.

All travel-related WNV cases (travel within Canada, travel outside of Canada, and unspecified travel) were excluded from Figure 1. International travel-related and unspecified travel WNV cases were excluded from all epidemiological analyses. Episode week is calculated using CDC weeks and is based on the earliest available date based on the following hierarchy: symptom onset date, diagnosis date, laboratory sample date or reporting date. Cases reported outside of the typical WNV season, which starts in the summer and continues through fall, were excluded from Figures 2 and 3.

Other indicators of mosquito-borne disease activity in Canada include surveillance data from animals and mosquitoes. In 2020, information on WNV-positive dead wild birds was largely provided by the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC); however, the province of Manitoba reported avian cases directly to PHAC. WNV and EEE virus infections are immediately notifiableFootnote 3 diseases in animals. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) provided nationwide data on WNV and EEE virus veterinary cases. Mosquito surveillance data for WNV in 2020 was collected and provided by four participating provinces and one territory: Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec, and the Northwest Territories. In 2020, information about mosquito pools tested for CSG viruses was only reported by the Northwest Territories, where mosquito pools were sampled weekly and tested at the end of mosquito season.

The findings in this report are subject to several limitations. First, the West Nile Virus Surveillance system is a passive surveillance system; therefore, as for any surveillance system, it is likely that the actual incidence of WNV infections in humans is underreported. Moreover, only approximately 20% of WNV infections are symptomatic therefore it is suspected that many cases would go undetected. Detection and reporting of WNV neurological syndrome are considered more complete than that of WNV non-neurological syndrome. Second, data collection methods and case definitions vary within Canada, and provincial and territorial disease reporting systems allow ongoing data updates, which may result in differences between what is presented in this report and provincial and territorial websites. Third, EEE and CSG viruses are not nationally notifiable therefore the true burden of cases is unknown.

This report is based on the latest data provided to PHAC for the 2020 transmission season (date as of: 2022/12/08).

West Nile virus

Human case surveillance

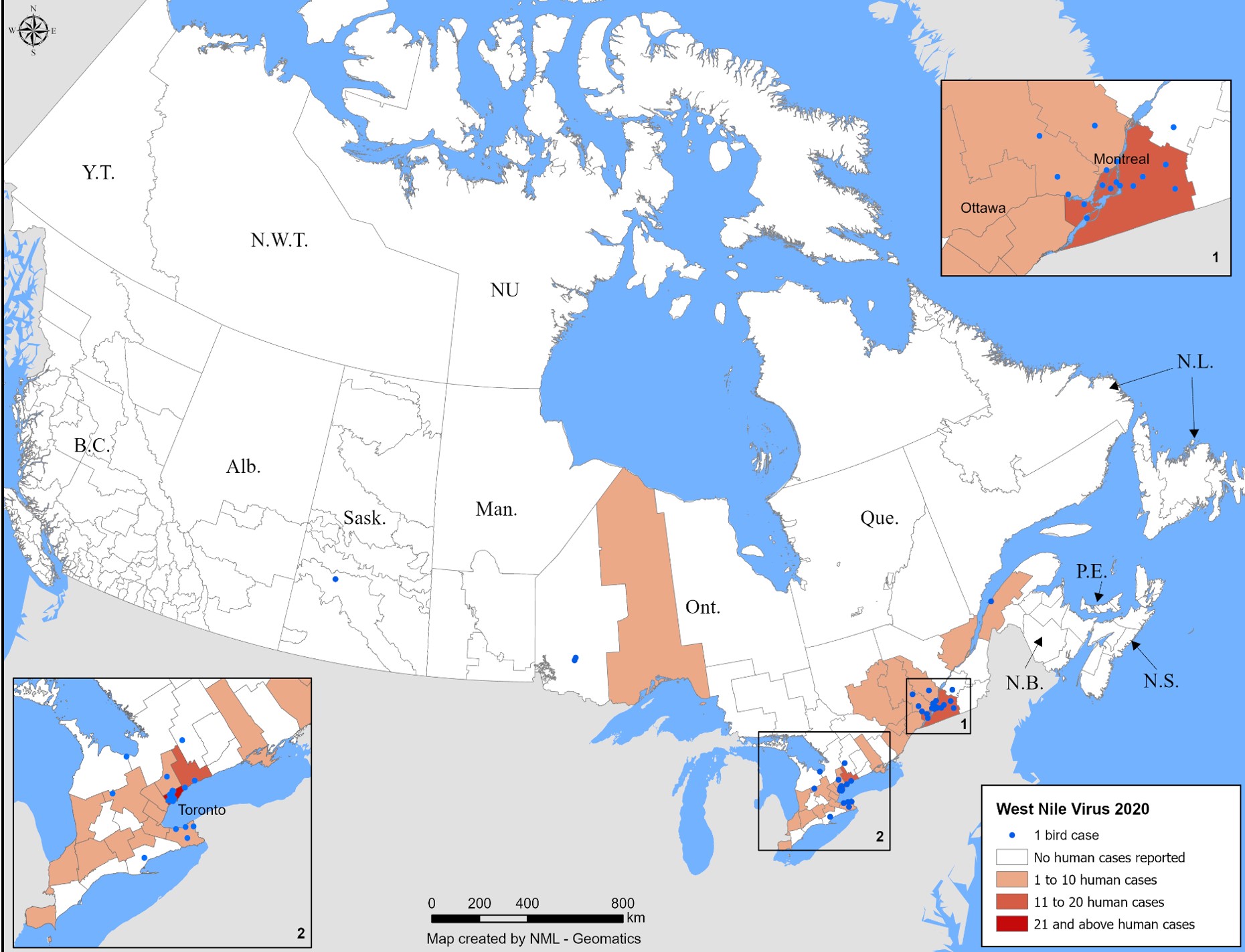

A total of 166 WNV human cases were reported to PHAC between January 1 and December 31, 2020. Cases were reported only by two provinces in 2020: Ontario (n=103) and Québec (n=63). Of the 166 cases, seven cases were travel-related and 159 cases were not travel-related (see section on Travel-Related Cases). The majority of the 159 cases were geographically distributed in the southern regions of Ontario and Québec (Figure 1).

In total, 98% of cases (n=163) acquired infection within Canada, including cases with no travel history (n=159) and cases with travel within Canada (n=4). Of the 163 cases, 153 were clinical and 10 were asymptomatic.

Figure 1 - Text description

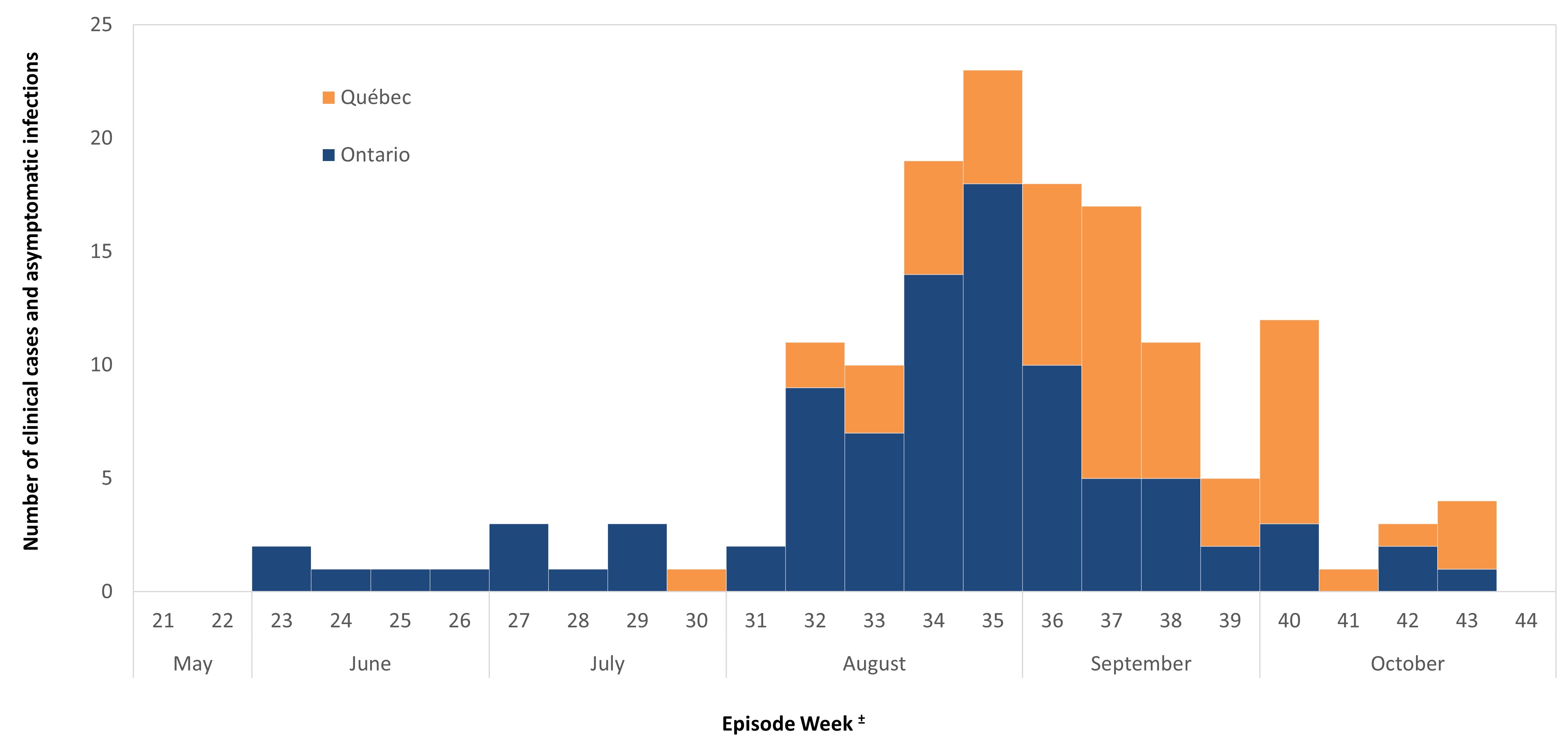

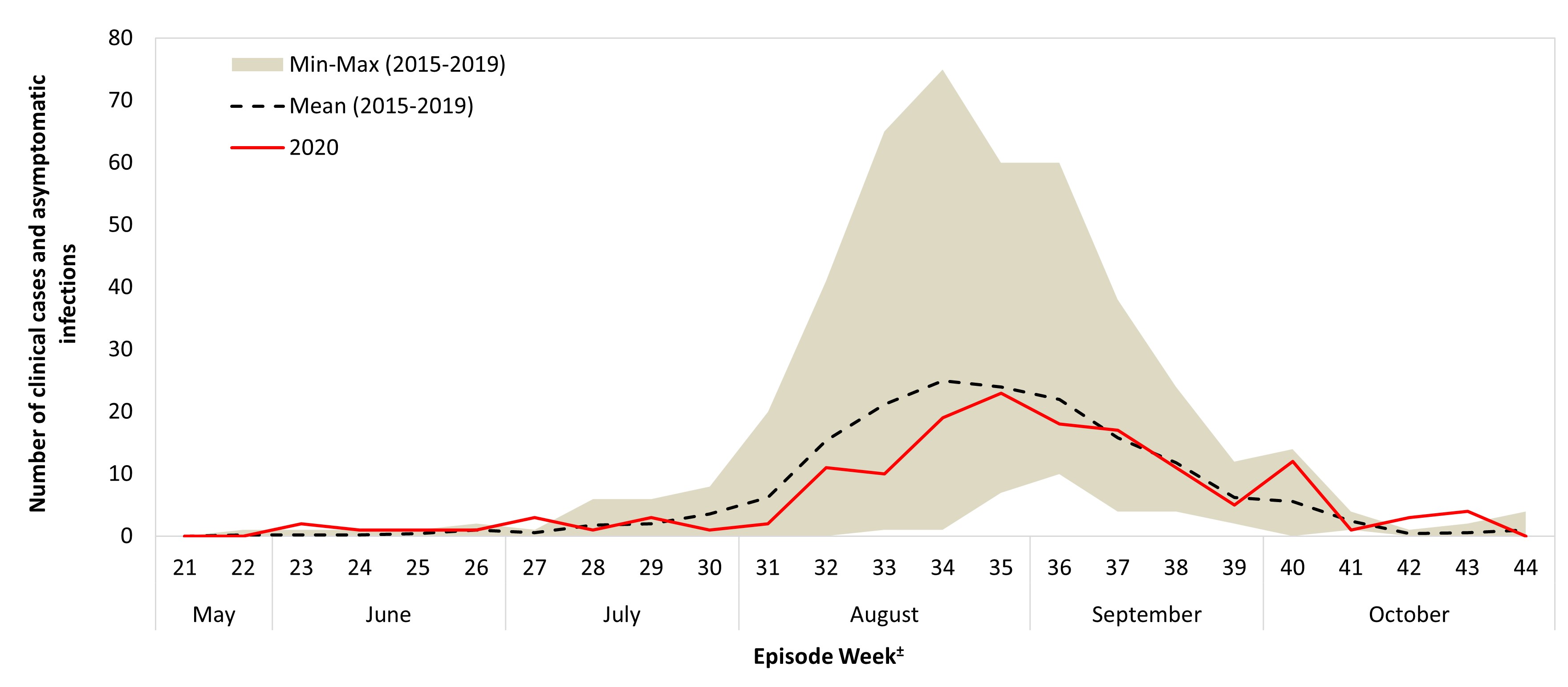

The earliest onset date for a WNV human case acquired within Canada in 2020 was June 1 (episode week 23). Over three-quarters (n=149) of cases were reported with an onset date between episode weeks 32 and 40 (mid-August to early October), peaking in week 35 (late August) (Figure 2). Typically, the peak weeks vary from year to year, ranging from week 32 to 37 (early August to mid-September) (Figure 3).

* Map excludes all travel-related cases.

Figure 2 - Text description

This graph shows that during 2020 transmission season, between surveillance week 21 and 44, 149 human infections (clinical and asymptomatic cases) were reported to Public Health Agency of Canada.

± WNV cases are grouped based on episode date. Episode week is calculated using the earliest available date based on the following hierarchy: symptom onset date, diagnosis date, laboratory sample date or reporting date.

Figure 3 - Text description

Of the 153 clinical cases acquired within Canada, 37% (n=56) were reported as WNV neurological syndrome, 33% (n=51) as WNV non-neurological syndrome and 30% (n=46) as unclassified/unspecified (Table 1). Among the clinical cases, seven deaths were reported; five were classified as neurological syndrome, one was non-neurological, and one was unclassified/unspecified. In addition, 10 WNV asymptomatic cases were reported.

± WNV cases are grouped based on episode date. Episode week is calculated using the earliest available date based on the following hierarchy: symptom onset date, diagnosis date, laboratory sample date or reporting date.

| Province | Clinical cases | Asymptomatic casesFootnote 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological | Non-neurological | Unclassified/Unspecified | Total | Rate (per 100,000)Footnote 1 | ||

| Ontario | 15 | 48 | 33 | 96 | 0.65 | 4 |

| Québec | 41 | 3 | 13 | 57 | 0.66 | 6 |

| Canada | 56 | 51 | 46 | 153 | 0.43 | 10 |

|

||||||

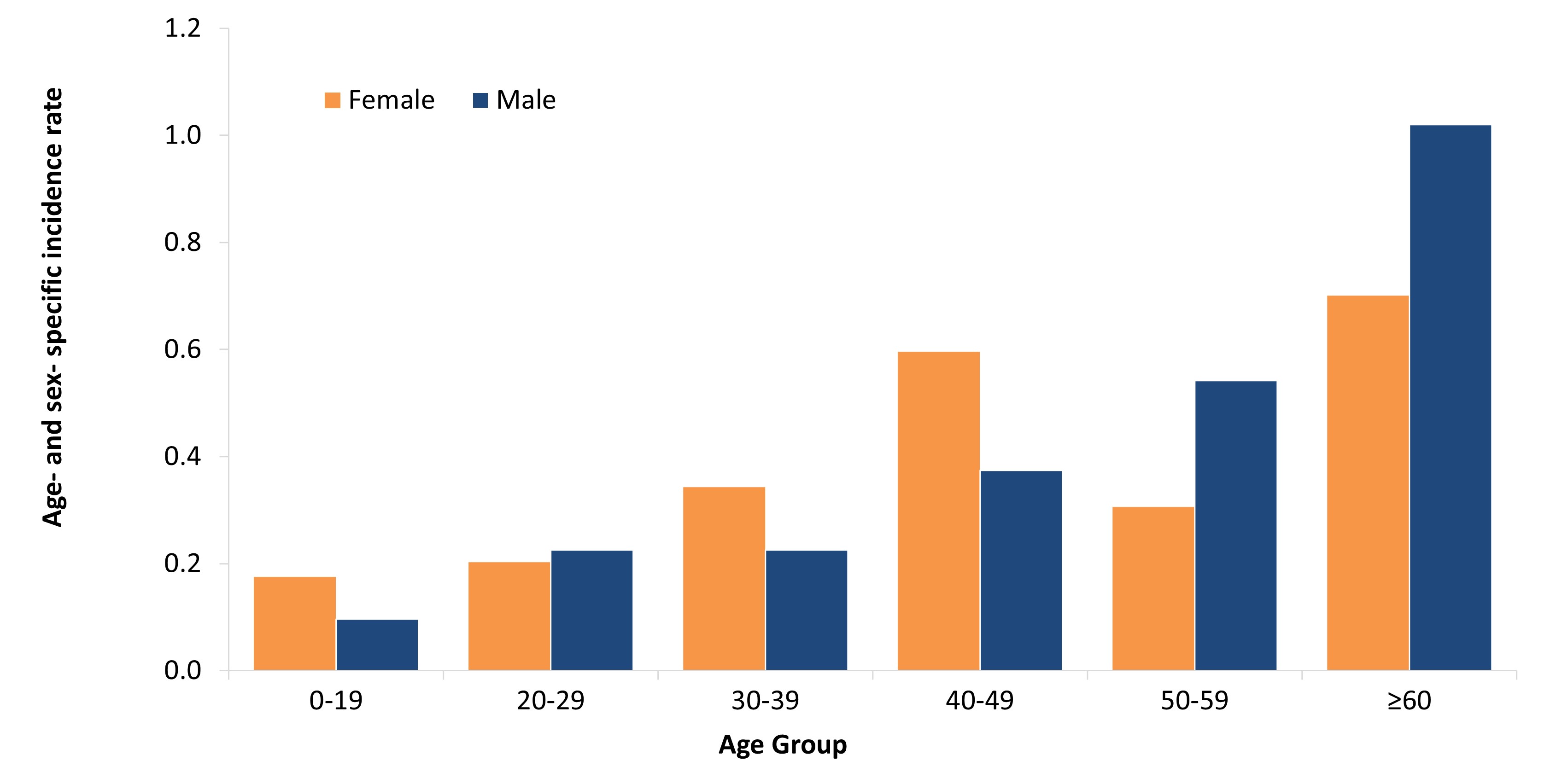

Figure 4 - Text description

This figure shows that the incidence rate* of reported infections (clinical and asymptomatic) increased with age; incidence was higher for females than males in the 0-19, 30-39 and 40-49 age groups, and lower in those 20-29, 50-59 and over 60 years old.

* Incidence was calculated using Q4 2020 Statistics Canada population estimates.

Travel-related cases

A total of seven travel-related WNV cases were reported; four cases were travel within Canada, two cases were acquired outside of Canada and one case did not specify a travel location during the 2020 transmission season. Of these, 71% (n=5) were classified as WNV non-neurological syndrome, 14% (n=1) as asymptomatic and 14% (n=1) as unclassified/unspecified. The median age of cases was 50 (range: 20-74). International travel locations included Cuba and Uganda.

Mosquito, wild bird, and equine surveillance

During the 2020 transmission season, 16,633 mosquito pools were tested for WNV in four provinces and one territory: Ontario (n=13,260), Québec (n=2,013), Manitoba (n=1,264), Saskatchewan (n=71) and Northwest Territories (n=25). Of these, 205 (<2%) pools tested positive for WNV: 171 in Ontario, 29 in Québec, and five in Manitoba (Table 2). In 2020, the percent of mosquito pools positive for WNV infection was highest in Québec (1.4%). The months with highest percent positivity for mosquito pools were August (Ontario, Manitoba) and September (Québec).

| Province | No. of Positive pools | Total Pools Tested | Percent Positive Pools | Month with highest percent positivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 171 | 13,260 | 1.3% | August |

| Québec | 29 | 2,013 | 1.4% | September |

| Manitoba | 5 | 1,264 | 0.4% | August |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 71 | 0% | N/A |

| Northwest Territories | 0 | 25 | 0% | N/A |

| Total | 205 | 16,633 | 1.2% | ------ |

|

||||

| Province | No. of Positive Birds | No. of Positive Horses |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 23 | 2 |

| Québec | 17 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 1 |

| Manitoba | 0 | 1 |

| Alberta | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 41 | 6 |

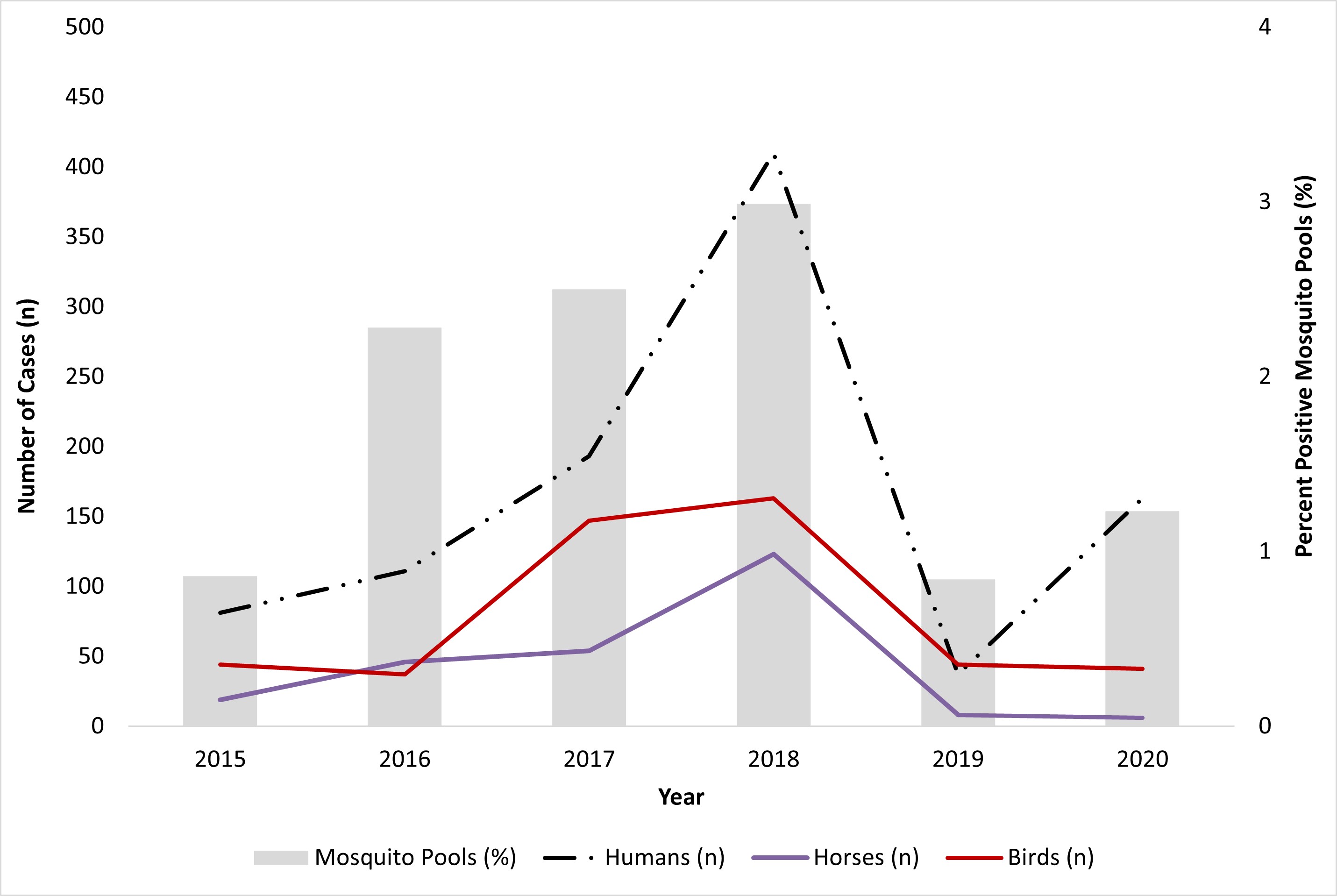

Figure 5 - Text description

This figure shows the number of human infections, birds, horses and percent positive mosquito pools observed in Canada in 2020 compared to 2015-2019.

California serogroup viruses

The NML identified a total of two human CSG virus infections: Alberta (n=1) and British Columbia (n=1). Further testing confirmed one infection was Jamestown Canyon (JC) virus and one infection was snowshoe hare (SSH) virus. Additionally, the province of Québec reported 11 infections of CSG viruses in humans (7 confirmed, 4 probable), of which 3 were associated with JC virus, 3 with SSH virus, 3 with SSH or JC virus and 2 were unknown. However, these infections were classified using a different case definitionFootnote 4 than the two infections reported by the NML.

In 2020, the Government of Northwest Territories tested 92 mosquito pools of which 32.6% (n=30) tested positive for CSG viruses. The collection dates for positive mosquito pools ranged from June 24th to August 12th, 2020, with the highest positivity rate (50%) in the month of August.

Eastern equine encephalitis virus

In 2020, the CFIA reported eight equine cases of EEE with either a clinical or laboratory diagnosis in Ontario. No human cases of EEE were reported in Canada.

Discussion

Despite the emergence of COVID-19 in late 2019, surveillance of mosquito-borne diseases continued in 2020, with an increase in human WNV cases and deaths reported in 2020 (166 cases, 7 deaths) compared to the previous year (45 cases, 2 deaths). This increase in human infections was accompanied by an increase in mosquito pool positivity across multiple jurisdictions in Canada. Similar increases were not noted in WNV infections reported in dead wild birds and horses. However, the number of reported human cases in 2020 was below the average of the previous five years (mean: 176 cases). Annual fluctuations in the number of WNV infections in humans, dead wild birds and horses, and percent positivity in mosquito pools are expected. It is unknown how factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted surveillance data for example, increased exposure due to time spent outdoors, travel restrictions, changes in health-seeking behaviours and constraints on public health programs.

Lower numbers of human WNV cases were observed in jurisdictions outside of Canada. Compared to 2019 (n=971), the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a lower number of cases of WNV in humans in 2020 (n=731)Footnote 5. Similarly, incidence rates for locally acquired cases in Europe in 2020 decreased when compared to 2019 (n=463), with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reporting 336 cases of WNV in humans Footnote 6Footnote 7.

In Canada, two confirmed infections of CSG viruses in humans were reported in 2020 by NML and 11 infections were reported by Québec. CSG viruses such as Jamestown Canyon virus and snowshoe hare virus are endemic in Canada, and evidenceFootnote 8 suggests that they are not only more common than previously thought, but their incidence might increase with climate changeFootnote 2. As CSG viruses are not nationally notifiable diseases in Canada, there is currently no formal surveillance system in place to monitor, track and report cases. Furthermore, infections caused by CSG viruses are likely under-diagnosed due to factors such as lack of awareness among healthcare professionals in CanadaFootnote 2.

There were no reports of human cases of EEE in Canada in 2020, despite eight horse cases. The last report of a human case of EEE occurred in Ontario in 2016. However, as with CSG, EEE is not nationally notifiable in humans and there is no formal surveillance system in place.

Public health conclusions

There are no vaccines or specific treatments for WNV, EEE virus and CSG virus human infections. Although severe illness can occur at any age, advanced age is one of the most important risk factors for the severe neurological disease after infection with WNVFootnote 9. Patients who develop severe neurological illness can experience a prolonged recovery and severe long-term sequelae (e.g., physical, cognitive, and functional)Footnote 9. Due to the serious and potentially fatal outcomes of WNV infection and lack of vaccines or treatment, it is important to focus on prevention strategies. Prevention strategies including education and promotion of personal protection (i.e., long-sleeved clothing, permethrin-treated clothing, window screens and mosquito repellents) from mosquito bites, as well as mosquito control programs in some jurisdictions in Canada, are critical for decreasing the risk of mosquito-borne infections in people. Continued education, increased awareness of CSG and EEE viruses and ongoing WNV surveillance is needed to help target prevention and control efforts and inform healthcare professionals as well as the public.

For more information including populations-at-risk, symptoms and treatment, please refer to Canada.ca.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada would like to acknowledge the provincial and territorial WNV and other mosquito-borne disease programs, Canadian Blood Services, Héma-Québec, the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC), and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) for their participation in the Canadian WNV Surveillance Program.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Kulkarni MA, Berrang-Ford L, Buck PA, Drebot MA, Lindsay LR & Ogden NH. Major emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases of public health importance in Canada. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015; 4(1):1-7.

- Footnote 2

-

Ludwig A, Zheng H, Vrbova L, Drebot MA, Iranpour M, Lindsay LR. Increased risk of endemic mosquito-borne diseases in Canada due to climate change. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2019; 45(4):90-7.

- Footnote 3

-

Government of Canada. Immediately Notifiable Diseases in Animals. [Internet]. 2021 [cited on 17 March 2022]. Available from: https://inspection.canada.ca/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/diseases/immediately-notifiable/eng/1305670991321/1305671848331.

- Footnote 4

-

Surveillance des maladies à déclaration obligatoire au Québec [Internet]. 2019 [cited on 27 January 2022]. Available from: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2019/19-268-05W.pdf.

- Footnote 5

-

Center for Disease Control. Final Cumulative maps and Data for 1999-2019 [Internet]. 2021 [cited on 27 January 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/statsmaps/cumMapsData.html.

- Footnote 6

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited on 15 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2019.

- Footnote 7

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2020 [Internet]. 16 February 2021 [cited on 15 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2020.

- Footnote 8

-

Drebot MA. Emerging mosquito-borne bunyaviruses in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2015; 41(6):117–23.

- Footnote 9

-

Patel H, Sander B, Nelder MP. Long-term sequelae of West Nile virus-related illness: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15(8):951-9.