Employment Equity Promotion Rate Study

Table of Contents

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of the relevant literature

- 3. Methodology and data

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- Appendix A – Methodology and data

- Appendix B – Model results

- Appendix C – Groups in occupational categories

Key terms used in this report

- “federal public service”

-

- departments and agencies that fall under the jurisdiction of the Public Service Employment Act

- “employees” or “public servants”

-

- indeterminate employees who are employed in departments and agencies that fall under the jurisdiction of the Public Service Employment Act

- “employment equity groups”

-

- as defined in the Employment Equity Act, the 4 employment equity groups are women, members of visible minorities, Aboriginal peoples (referred to as Indigenous people throughout this study) and persons with disabilities

- “counterparts” and “reference group”

-

- a group of employees not belonging to the employment equity group being considered

- the counterparts for women are men, and the counterparts for each of the other 3 groups are people who did not self-identify as belonging to that particular group; for example, the counterparts for persons with disabilities are people who did not self-identify as having a disability

Executive summary

This study compares the promotion rates within the federal public service of each of the 4 employment equity groups to each of their counterparts.

In part 1 of the study, we analyze promotion data between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2018, for all public servants hired on or after April 1, 1991, and we compare the promotion rates of employment equity groups to those of their counterparts.

In part 2, we examine the promotion rates of new hires across 2 time periods: from April 1, 1991, to March 31, 2005, and from April 1, 2005, to March 31, 2018. As in part 1 of the study, within each time period, employment equity promotion rates are directly compared to those of their counterparts. By analyzing changes across these 2 time periods, we observe whether there has been progress in the relative promotion rates of employment equity groups.

In part 3 of the study, we shed light on differences in employment equity promotion rates, by comparing each group’s share of applicants to appointment processes, with their representation in the federal public service population, and with their share of promotions. This analysis allows us to explore whether lower promotion rates across employment equity groups are due to lack of participation in appointment processes or to a lower success rate in these processes.

Summary of findings

Part 1: Analysis of recent employment equity promotion rates

Part 1 of the study is based on 172 125 promotions from 230 310 indeterminate employees. Our findings present a mixed picture in terms of promotion rates across employment equity groups. Our public service-wide results indicate that women have a higher promotion rate when compared to men. This contrasts with Indigenous people and with persons with disabilities, who both experienced lower promotion rates than their respective counterparts. We found no appreciable difference between members of visible minorities and their counterparts.

Results also show variations for some employment equity groups across occupational categories. For example, despite having a higher overall promotion rate when compared to men, women have a lower promotion rate in the Scientific and Professional and the Technical categories. These lower promotion rates are offset by higher relative promotion rates for women in the Administrative Support and Administrative and Foreign Service occupational categories.

Part 2: Analysis of promotion rates of employment equity new hires across 2 time periods

Part 2 of the study relied on 74 762 promotions from 112 667 indeterminate employees and 97 856 promotions from 141 836 indeterminate employees for the first and second time periods respectively. Our results on the promotion rates of new hires across time periods (from April 1991 to March 2005 and from April 2005 to March 2018) suggest an improvement over time in the relative promotion rates of women, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities. However, promotion rates for Indigenous people and persons with disabilities remain below those of their counterparts. For members of visible minorities, there are no appreciable differences in promotion rates relative to their counterparts in either of the 2 time periods.

Part 3: Employment equity applicant representation and shares of promotions

Our analysis suggests that women and members of visible minorities apply at a higher rate than their rate of representation in the federal public service. Women’s share of promotions is roughly equivalent to their representation as applicants, while members of visible minorities exhibit a share of promotions that is lower than their representation as applicants.

A different pattern emerges for Indigenous people and persons with disabilities, whose representation as applicants is below their representation rates in the federal public service, while their share of promotions is on par or above their representation as applicants. This may, in part, explain differences in the promotion rates of these 2 employment equity groups as compared to their counterparts.

In response to these findings, we are recommending that, in consultation with stakeholders and employment equity community members:

- Recommendation 1: further research be conducted to better understand underlying barriers that contribute to lower promotion rates for some employment equity groups

- for example, the upcoming Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey (Spring 2020) should be leveraged to gain insight into employment equity group views on barriers to career progression

- Recommendation 2: work be undertaken to break down employment equity category data by sub-groups to allow for a more comprehensive and accurate identification of barriers that are unique to individual sub-groups, including their intersectionality

- Recommendation 3: further outreach be provided to federal departments and agencies in order to increase awareness of the range of policy, service and program options aimed at supporting a diverse workplace

- Recommendation 4: public service-wide approaches to career progression be explored including broadening access to existing successful programs and services such as the Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative and the Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology Program at Shared Services Canada

- Recommendation 5: concerted efforts across central agencies be undertaken to explore how we can learn from the Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative and extend similarly targeted services and development opportunities to all employment equity groups, including development programs and career support services that are specifically designed with, and for, employment equity groups

We extend our thanks to Professor Marcel Voia and Statistics Canada who have reviewed this study and provided insightful suggestions, comments and feedback.

1. Introduction

The Public Service Commission of Canada is responsible for promoting and safeguarding a merit-based, representative and non-partisan federal public service. As part of our oversight activities, we undertake investigations as well as research and audit activities to assess the integrity of the public service staffing system and its performance against intended outcomes.

This study, along with our pilot project on anonymized recruitment, our staffing and non-partisanship survey, and our current Audit on Employment Equity Representation in Recruitment, is part of a broader series of oversight initiatives aimed at assessing the staffing system’s performance with respect to representativeness.

Over the years, promotion rates for employment equity groups have been the subject of sporadic interest. For example, in 2000, we conducted a joint study with Canadian Heritage to analyze the mobility (lateral movement and promotions) of each employment equity group compared to a non-employment equity reference group. Our 2000 study explored 12 years of mobility data (from 1986 to 1998) and found that, with a few exceptions, all employment equity groups faced lower odds of a promotion across occupational categories. Footnote 1

More recently, in an unpublished 2015 study examining 22 years of mobility data in the federal public service, we found that members of visible minorities and Indigenous people experienced promotion rates that were similar to those of their counterparts, while women and persons with disabilities experienced lower promotion rates than those of their counterparts Footnote 2. Our 2015 study also concluded that the promotion rates for women had significantly improved over time.

In this present study, we introduce methodological improvements and draw on a longer longitudinal dataset spanning 27 years of promotions in the federal public service. For instance, in our 2015 study, employees who left the public service before the end of the period under study were excluded from the analysis. This may have inadvertently introduced a bias, as separations from the public service may be the result of dissatisfaction regarding career progression. As a result, it is likely that our 2015 study relied on a sample which excluded individuals with lower promotion rates. To remedy this, our methodological approach in this study includes individuals who have left the public service during the observation period. In addition, the analysis of intersectionality in the 2015 study was restricted to the interaction between gender and the employment equity status of each of the 3 other groups. Our study extends the analysis to all possible combinations of employment equity status. Due to these methodological improvements, it is difficult to make direct comparisons between this current study and previous ones.

This study aims to provide an empirical analysis of promotion rates of employment equity groups using administrative data. For this reason, this study does not investigate potential barriers to promotions, such as willingness to relocate for work, or other factors which may explain observed differences in promotion rates. This being said, an analysis of gaps in the promotion rates of employment equity groups is essential to providing insights into where efforts and resources should be allocated to identify and address barriers in the staffing system.

The analysis is divided into 3 parts:

- In part 1, we compare promotion rates of employment equity groups to their respective counterparts over a 13 year period — from April 1, 2005, to March 31, 2018.

- In part 2, we draw on 27 years of data holdings to compare the promotion rates of new employment equity hires across 2 time periods:

- April 1, 1991 to March 31, 2005

- April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2018

- In part 3, we compare the representation of employment equity groups within the applicant pool to their representation rates in the federal public service as well as to their share of appointments over 2 fiscal years (2016–17 and 2017–18).

2. Review of the relevant literature

Employment equity promotion rates have been the subject of increased attention in the private sector. For example, a 2009 study (English only) analyzed employee data for 22 000 full-time workers at a Canadian firm. The study noted that the promotion gap between men and women was largest at the lowest levels of the organization. It also found that while there was no promotion gap for Caucasian women at the highest levels of the organization, women who were members of visible minorities still lagged behind. The study suggested that women in Canada did not face a glass ceiling but rather a “sticky floor.”

A 2017 study of Belgian workers (English only) analyzed factors that could explain observed promotion gaps between women and men. The results suggest that the number of hours worked explained 40% of the promotion gap. The study found that women were more likely to work part-time, which offered them fewer promotion opportunities, and that they were also less available to work long hours. The fact that more women in the study tended to work in industries with flatter hierarchies, which offer fewer promotions, explained another 20% of the gap.

Similar patterns could also be at play in the Canadian labour market. In 2017, a report by the McKinsey Global Institute (English only) found that, compared to women in other countries, women in Canada had one of the highest labour force participation rates. However, the ratio of women in leadership positions and women doing unpaid care work was closer to the mid-point range. If, as was the case for women in the Belgian study, women in Canada work fewer hours, and in industries with fewer opportunities for advancement, this could explain in part the lower ratio of women in leadership position despite their high labour force participation rate.

Studies that have focused on public sector jurisdictions offer more positive results for women, although not necessarily for other employment equity groups. According to a 2018 report on gender diversity targets in Ontario, 47% of board members of Ontario provincial agencies were women. In contrast, women represented only 14% of board members of TSX-listed companies.

In 2015, a workforce profile report on British Columbia’s public service (English only) indicated that 12.2% of women in regular positions obtained a promotion, compared to 11.5% of men. On the other hand, members of visible minorities had a slightly lower promotion rate, with 11.7% of members of visible minorities having obtained a promotion, compared to 12% for their counterparts.

British Columbia’s public service report also showed that Indigenous people and persons with disabilities presented even larger gaps in their promotion rates. Only 9.1% of Indigenous people obtained a promotion compared to 12% for their counterparts, while only 8.9% of persons with disabilities obtained a promotion compared to 12.1% for their counterparts.

A 2013 report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights examined promotion rates versus the representation of employment equity groups in the federal public service in 2011–12. As was found in British Columbia’s public service report, the share of promotions for women and members of visible minorities was closely aligned to their representation rates in the public service workforce. Women and members of visible minorities represented 55.6% and 12.1% of all federal public servants, while receiving 57.6% and 13.5% of all promotions respectively.

On the other hand, similarly to what was reported in British Columbia’s public service report, the Standing Senate Committee also found that Indigenous people and persons with disabilities were promoted at a lower rate than their rates of representation in the federal public service. In fact, although persons with disabilities represented 5.7% of all public servants, they obtained only 4.6% of promotions, whereas Indigenous people represented 4.9% of public servants while obtaining only 4.6% of promotions.

Overall, while studies focusing on private sector organizations show that women have lower promotion rates than men, public sector reports that we’ve reviewed suggest that women in the public sector have equivalent or slightly better promotion rates than men.

Although our review of public sector organizations suggests that members of visible minorities also experience comparable or better promotion rates than their counterparts, the same may not be said of Indigenous people and persons with disabilities, who show a pattern of under-promotion when compared to their internal representation.

3. Methodology and data

Our broader dataset covers 27 years, from April 1, 1991, to March 31, 2018. The dataset includes all promotions of indeterminate employees employed within departments and agencies that are governed by the Public Service Employment Act.

This dataset was then divided based on requirements of part 1 of the study, which explores recent promotion patterns for employment equity groups between April 2005 and March 2018, and part 2, which seeks to assess to what extent we could observe progress over 2 time periods (April 1991 to March 2005, as compared to the period of April 2005 to March 2018).

In both parts 1 and 2 of our study, the results are presented as a percentage difference in the promotion rate between 2 groups. These differences in promotion rates are referred to as “relative promotion rates.” Accordingly, a relative promotion rate of 0 indicates equal promotion rates between 2 groups. Conversely a promotion rate above 0 for a given employment equity group indicates a higher promotion rate relative to its counterparts, whereas a relative promotion rate below 0 signals a lower relative promotion rate. Footnote 3

The model also allows us to investigate several factors that may have an impact on promotion rates. As in our 2000 study, our model controls for a number of these factors:

- employment equity status

- age

- first official language

- bilingual status

- salary range

- occupational category

- location (National Capital Region versus other regions)

- periods of leave without pay

For a more thorough explanation of the technical model and dataset, please refer to Appendix A.

3.1 Part 1 – Analysis of recent employment equity promotion rates

The objective of part 1 of the study is to explore promotion rates in the latter part of our dataset in order to compare employment equity promotion rates to those of their counterparts.

Observation period

We gave careful consideration to how best define our observation period. Promotion rates calculated over too long a period of time (27 years) may result in estimates that straddle significantly different eras. Estimating promotion rates over such a long period may not provide an accurate view of the current environment, and would not allow us to determine the progress or deterioration of promotion rates over time. Simply put, an observation period that is too long may combine widely different workplace conditions that exist at different points in time, without accurately reflecting any of them.

On the other hand, too short a period may result in too few observations (promotions) within groups to allow a reliable estimate of their promotion rate. This can be particularly the case for smaller groups such as Indigenous people or persons with disabilities. In striking a balance between these considerations, we opted for a 12- to 14-year observation period.

Dataset

From our broader dataset, we drew the career history of all employees hired on or after April 1, 1991. Although our analysis is restricted to promotions occurring between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2018, calculating time between promotions requires knowing when the previous promotion occurred, even when the previous promotion falls outside our observation period.

In addition, accounting for employees who never received a promotion during their career requires their full employment history as public servants up to the end of our observation period. By restricting the dataset to employees who were hired on or after April 1, 1991, we resolve both of these issues.

Combining requirements for our observation period with our dataset requirements, the resulting subset of data for part 1 covered 172 125 promotions from 230 310 employees.

In Section 4 of this report, we report relative employment equity promotion rates:

- for the overall federal public service

- at the occupational category level

- for promotions into and within the Executive Group

3.2 Part 2 – Analysis of promotion rates of employment equity new hires across 2 time periods

In order to assess whether promotion rates of employment equity groups have improved over time, we divided 27 years of available data into 2 time periods. The first period covers promotion data of all employees hired between April 1, 1991, and March 31, 2005. The second period covers promotion data for all employees hired between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2018. The relative employment equity promotion rates within each time period were then compared across the 2 time periods to observe any changes. The 2 datasets cover 74 762 and 97 856 promotions respectively, with a total number of employees of 112 667 and 141 836 respectively.

3.3 Part 3 – Employment equity applicant representation and shares of promotions

Lower employment equity promotion rates may be the result of either lower rates of application to promotion opportunities or a lower success rate in appointment processes or both. For example, an employment equity group may demonstrate an equal success rate to its counterpart during a staffing process but may be less inclined to apply for promotion opportunities.

As our analysis of employment equity promotion rates in parts 1 and 2 of our study cannot distinguish between these 2 possibilities, we examined the representation of each employment equity group in fiscal years 2016–17 and 2017–18:

- in the general population of federal public servants

- as a percentage of applicants

This data was then directly compared to each employment equity group’s share of total promotions in 2016–17 and 2017–18. The goal of this analysis is to better contextualize our findings on whether potential barriers exist in attracting employment equity groups to apply for promotions or within the staffing process itself, or both.

4. Findings

4.1 Part 1– Analysis of recent employment equity promotion rates

Our results are reported as relative promotion rates where a relative promotion rate above 0 indicates a higher promotion rate for a given employment equity group compared to their counterpart. Conversely, a negative relative promotion rate indicates an employment equity promotion rate that is lower to that of their counterparts.

Public service-wide results

Our analysis of relative promotion rates from April 2005 to March 2018 presents a mixed picture. As shown in Table 1, our results for the public service indicate that women have 4.3% higher rates of promotion than men, whereas there is no discernible difference between members of visible minorities and people who are not members of visible minorities (0.6%). On the other hand, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities experienced lower relative promotion rates.Footnote 4

| Employment equity group | Difference in promotion rates |

|---|---|

| Women | +4.3%** |

| Visible minorities | +0.6% |

| Indigenous people | -7.5%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -7.9%** |

| ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level | |

These results for the federal public service are consistent with those reported by British Columbia’s public service and by the Standing Senate Committee’s examination of promotion rates in the federal public service. However, when public service-wide promotion rates are broken down by occupational category, there are significant differences for some employment equity groups across categories.

Results by occupational categories

As shown in Table 2, women have considerably higher promotion rates than men in the Administrative Support and Administrative and Foreign Service occupational categories, but have considerably lower relative promotion rates in the Scientific and Professional and Technical categories.

Indigenous people and persons with disabilities saw lower relative promotion rates in the Administrative Support and the Scientific and Professional categories than their counterparts. When compared to their counterparts, Indigenous people also had a lower relative promotion rate in the Administrative and Foreign Service Category, whereas persons with disabilities had a substantially higher relative promotion rate in the Operational Category.

Finally, members of visible minorities show relative promotion rates similar to or higher than their counterparts across all occupational categories, with the highest promotion rate differentials for members of visible minorities being observed in the Administrative Support (+6.2%) and Technical categories (+7.0%) as well as a slightly lower relative promotion rate (-2.2%) in the Administrative and Foreign Service Category.

| Women | Visible minorities | Indigenous people | Persons with disabilities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Support | +11.5%** | +6.2%** | -11.6%** | -20.3%** |

| Administrative and Foreign Service | +10.0%** | -2.2%* | -6.7%** | -3.3% |

| Operational | +2.2% | +0.5% | -0.6% | +28.0%** |

| Scientific and Professional | -5.7%** | -0.3% | -13.3%** | -13.9%** |

| Technical | -10.6%** | +7.0%* | +1.1% | -2.0% |

| * stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level | ||||

Promotion rates within the Executive Category, from feeder groups, and to the Executive Category

We also undertook a separate analysis of relative promotion rates:

- within the Executive (EX) Group

- from the feeder groups (EX minus 1 level) to EX and EX-equivalent positions

- from the feeder groups (EX minus 1 level) to the EX group only

As can be seen in Table 3, lower relative rates of promotion within the Executive Category are observed for members of visible minorities ( 15.6%). Although not statistically significant, we note that the relative promotion rates of Indigenous people and persons with disabilities are estimated at -11.3% and -17.7% respectively. It is worth noting that statistical significance is strongly influenced by the number of observations under study. Given the relatively low number of Indigenous executives and executives with disabilities, larger differences in promotion rates would be required to achieve statistical significance.

Even so, such large differences, whether statistically significant or not, deserve attention and should be explored further, particularly when one considers that they fall in line with our results for the federal public service, which also point to a lower relative promotion rate for both of these groups.

| Promotions within the EX group | Promotions from EX minus 1 level to the EX group and EX-equivalent | Promotions from EX minus 1 level solely to the EX group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | -2.7% | -3.6% | +15.6%** |

| Visible minorities | -15.6%** | -0.5% | -25.7%** |

| Indigenous people | -11.3% | -10.6% | +3.5% |

| Persons with disabilities | -17.7% | +5.5% | +2.4% |

| * stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level | |||

A somewhat different picture emerges when we consider promotions from feeder groups either to the Executive Category or to EXequivalent positions (Table 3, column 2). While the relative promotion rate from the feeder groups of Indigenous people remains relatively low (-10.6%), all other groups display promotion rates broadly comparable to those of their counterparts.

When the analysis is restricted to promotions from the feeder groups to the Executive Group (Table 3, column 3), members of visible minorities display substantially lower relative rates of promotion (-25.7%), while all other employment equity groups show equal or higher promotion rates relative to their counterparts. However, it is important to note that promotion rates for members of visible minorities from the EX minus 1 level are on par with their counterparts (Table 3, column 2). This suggests a larger promotion rate from the EX minus 1 level to EX-equivalent positions compared to their counterparts. In fact, our data supports this interpretation. When compared to their counterparts, members of visible minorities have a relative promotion rate of +33.4% to EX-equivalent positions. Further analysis should be undertaken to determine whether members of visible minorities are concentrated in occupations for which a career progression towards EX-equivalent positions is more prevalent compared to a career progression leading to the Executive Category.

Intersectionality: Impact of belonging to 2 or more employment equity groups

Intersectionality refers to the compounding effect of belonging to 2 or more employment equity groups, above and beyond the individual impact of each employment equity status on promotion rates. For instance, the intersectionality between gender and Indigenous status captures the unique circumstances of Indigenous women, above and beyond the promotion rates of women and Indigenous people already estimated by the standard model.

Our analysis indicates that only the interaction of visible minority status and gender proved to be statistically significant. While women tend to have a higher promotion rate when compared to men, within the visible minority group, they have similar promotion rates. This result is also consistent with the findings of our 2015 study.

Other interactions

We also measured interactions between other factors and employment equity status. Among interactions of interest, we note how geographical location interacts with employment equity status. For instance, women tend to have higher promotion rates compared to men in the National Capital Region versus outside the region. Conversely, persons with disabilities have significantly lower promotion rates in the National Capital Region versus outside the region.

A number of interactions between age and employment equity status are also significant. Overall, for all employment equity and non-employment equity groups, promotion rates decrease with age. However, the decrease in promotion rates with age is not as pronounced for women, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities.

Thus, for Indigenous people and persons with disabilities, they are less likely to get promoted as they get older, although the gap between these groups and their counterparts shrinks with age. On the other hand, while women have similar promotion rates to men at the early stages of their careers, as they get older, their promotion rate tends to surpass that of men.

4.2 Part 2 – Progress on employment equity promotion rates: A comparison of 2 time periods

As noted in our Introduction, part 2 of our study seeks to compare the promotion rates of new employment equity hires to those of their counterparts across 2 different time periods. The first period captures promotions between April 1, 1991, and March 31, 2005, experienced by employees hired during this period.

The second time period covers promotions between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2018, for employees hired during this second time interval. The goal of this comparison is to determine whether progress in employment equity promotion rates can be observed across the 2 time periods as experienced by new hires.

As shown in Table 4, there were improvements for 3 of the 4 employment equity groups, namely women, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities. For women, we note a net gain of 6.2% in their relative promotion rate across time periods, going from -5.0% in the first time period to +1.2% in the second. For members of visible minorities, no appreciable difference is observed in their relative promotion rates in either time period or across time periods.

We note improvements for newly hired Indigenous people and persons with disabilities, as with women. Indigenous people saw a 2.3% improvement in their promotion rate when compared to their counterparts. For persons with disabilities, we note an improvement of 3.8% in their relative promotion rate. Yet, despite improvements, the relative promotion rates for newly hired Indigenous people and persons with disabilities remain significantly lower than those of their counterparts.

| 1991–92 to 2004–05 | 2005–06 to 2017–18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | -5.0%** | +1.2% |

| Visible minorities | -0.9% | -1.6% |

| Indigenous people | -8.2%** | -5.9%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -10.2%** | -6.4%** |

| ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level | ||

4.3 Part 3 – Representation of employment equity groups as applicants, in the federal public service, and as a share of promotions

Promotion rates depend on both the success of a particular employment equity group during the staffing process and how likely they are to apply for promotion opportunities. That is, an employment equity group may be under-promoted because it encounters barriers at the application stage, during the staffing process, or both.

A barrier-free staffing process can still result in the under-promotion of an employment equity group if its members do not apply to promotion opportunities in proportion to their representation rate in the federal public service. On the other hand, employment equity groups may apply for a promotion at a rate that is equivalent to or greater than their representation, but still face potential barriers during the staffing process.

As our analytical approach in parts 1 and 2 of the study does not differentiate between these 2 possibilities, we provide a cursory analysis of the representation of each employment equity group as applicants. This data is then compared to their representation rates in the federal public service to assess general interest in promotion opportunities and success rates in appointment processes to gauge for possible barriers. To this end, we analyzed application data to internal indeterminate job advertisements for fiscal years 2016–17 and 2017–18.Footnote 5 Table 5 summarizes our results.

As in parts 1 and 2 of our study, data presented in Table 5 is restricted to indeterminate employees who are employed in departments and agencies governed by the Public Service Employment Act. As a result, these figures differ slightly from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s annual report on employment equity representation.

| Women | Visible minorities | Indigenous people | Persons with disabilities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–17 | |||||

| Population | 54.0% | 14.6% | 5.3% | 5.7% | |

| Applicants | 60.6% | 21.0% | 3.9% | 3.9% | |

| Promotions | 58.0% | 15.7% | 4.9% | 4.0% | |

| 2017–18 | |||||

| Population | 54.1% | 15.4% | 5.3% | 5.4% | |

| Applicants | 60.7% | 21.8% | 4.0% | 4.0% | |

| Promotions | 59.2% | 17.1% | 5.0% | 4.0% |

Results from Table 5 cannot be directly compared with results from parts 1 and 2. This is due to the significant difference in the time periods being considered across these 2 parts of our study (13 years in part 1, compared to 2 years in part 3) as well as the fact that part 3 of our study does not control for other factors that may impact promotion rates, which we have controlled for in part 1 and 2 (such as age, location in the National Capital Region). Even so, Table 5 provides additional and complementary information which can contextualize our overall findings and help identify where efforts could initially be focussed.

For instance, women’s share of promotions (59.2% in 2017–18) is roughly in line with their representation as applicants (60.7%) and surpasses their representation in the federal public service (54.1%). In contrast, for members of visible minorities, their representation as applicants (21.8% in 2017–18) is considerably larger than both their representation in the general population (15.4%) and their share of promotions (17.1%).

Conversely, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities display a lower representation rate as applicants than their representation rates in both the general population and promotions. This indicates that these 2 groups are less likely to apply to promotion opportunities, which may explain their lower rates of promotion despite their relative success in appointment processes.

In fact, for both of these groups, applicants tend to be promoted in proportion to their representation as applicants. For example, in 2017–18, Indigenous people represented 4.0% of applicants but 5.0% of promotions, whereas persons with disabilities had a rate of promotions similar to their representation in the applicant pool (4.0%).

This analysis offers insight into where potential barriers may be present regarding the promotion rates of employment equity groups. Members of visible minorities tend to apply at a rate that is higher than their representation rate, but may encounter potential barriers during the staffing process. On the other hand, persons with disabilities and Indigenous people may face an entirely different set of challenges at the application stage, while presenting success rates which are in line with their representation as applicants.

More analysis should be done using data on employment equity group applicant representation in comparison to their representation rates in the federal public service and their share of promotions, while controlling for key factors (as was done in parts 1 and 2 of this study). This would deepen our understanding of potential barriers to promotion opportunities within specific employment equity groups.

5. Conclusions

The overarching goal of this study was to determine current gaps in the promotion rates of employment equity groups when compared to their counterparts, and to assess progress in promotion rates of employment equity groups over the past 30 years. The study relied on survival analysis techniques to estimate the differences in promotion rates between the 4 employment equity groups and their respective counterparts.

Part 1 of our study shows that, in the federal public service, women and members of visible minorities have equal or better rates of promotion than their counterparts. However, for women, a breakdown by occupational category indicates that this is due to a significantly higher promotion rate in the Administrative Support and Administrative and Foreign categories, and partially offset by significantly lower promotion rates in the Scientific and Professional, and Technical categories.

Within the Executive Category, except for women, all employment equity groups have appreciably lower promotion rates when compared to their respective counterparts. With regard to promotion rates from feeder groups to EX and EX-equivalent positions, of all the employment equity groups, only Indigenous people display rates of promotion that are different (and, in their case, lower) than those of their counterparts. However, with regard to entry into the Executive Group (and therefore not including EX-equivalent positions), all employment equity groups, except for members of visible minorities ( 25.7%), have equal or greater promotion rates when compared to their respective counterparts.

Part 2 of our study shows that over the past 27 years there has been a noticeable improvement in the rates of promotion for women, Indigenous people and persons with disabilities. Yet despite these improvements, current results for the public service show that Indigenous people and persons with disabilities still experience lower rates of promotion than their respective reference groups.

Part 3 of the study reveals that the share of promotions for members of visible minorities is below their representation as applicants. We also found that Indigenous people and persons with disabilities are less likely to apply for promotion opportunities. However, their share of promotions is equivalent to or above their representation as applicants. This indicates that these 2 groups may face barriers at the application stage.

These results complement the conclusions of the Senate Committee on Human Rights, but they also raise new issues. Like the Senate Committee, we found that, overall, persons with disabilities and Indigenous people are promoted at a lower rate than their representation rates in the federal public service. However, our analysis of applicant data points to possible barriers for these 2 employment equity groups that may reduce their interest in or willingness to apply for promotion opportunities.

As well, our analysis on the representation rates of members of visible minorities as applicants sheds light on the Senate Committee’s conclusion that members of visible minorities are promoted at the same rate as they are represented in the federal public service. This conclusion should be tempered by the fact that members of visible minorities apply at a rate that is higher than their representation rate in the public service, with a resulting share of promotions that is below their interest in promotion opportunities. In the same vein, our results by occupational categories suggest that an analysis of promotion rates for women should consider how overall promotion rates can sometimes be the result of diverging and offsetting trends in promotion rates across occupational categories.

Moving forward

The analysis presented in this study allows us to detect and measure gaps in the promotion rates of employment equity groups. As a next step, it will be important to explore what barriers employment equity groups may face in advancing their careers. This study suggests avenues for further inquiry.

For instance, more research is needed to understand why women are under-promoted in the Scientific and Professional and Technical categories. Current work such as our Audit on Employment Equity Representation in Recruitment will be instrumental in mapping potential barriers.

The Public Service Commission will also carry out more targeted research with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer to identify factors influencing employment equity promotion rates. We will continue to support departments by providing them with a range of policy, service and program options to support a diverse workplace.

Employment equity is a shared responsibility between the Public Service Commission, the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer and federal departments and agencies. With this in mind, we will engage key stakeholders as well as members of the employment equity community to identify barriers to career progression and to determine how best to address them.

Concerted efforts can lead to sustained and meaningful progress. They may also point to broader foundational changes, such as legislative or policy adjustments. We will be mindful of these possibilities as our work unfolds, and will actively recommend and support such changes should they be warranted.

As currently defined, employment equity categories are broad and may limit our ability to fully understand barriers that are unique to specific sub-groups. For instance, the current definition of members of visible minorities includes all racialized groups. It is possible that different groups within the visible minority community face unique challenges as was recently argued by the Federal Black Employee Caucus in Connect-Empower-Progressing: A Report on the Inaugural Symposium hosted by the Federal Black Employee Caucus with the Institute on Governance. In the same way, the category of persons with disabilities does not differentiate between types of disability or severity. To properly identify barriers to career progression, employment equity categories and related data need to be broken down. We are currently undertaking this work with our colleagues at the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer.

In response to these findings, we recommend that, in consultation with stakeholders and employment equity community members:

-

Recommendation 1: further research be conducted to better understand underlying barriers that contribute to lower promotion rates for some employment equity groups

- for example, the upcoming Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey (Spring 2020) should be leveraged to gain insight into employment equity group views on barriers to career progression

- Recommendation 2: work be undertaken to break down employment equity category data by sub-groups to allow for a more comprehensive and accurate identification of barriers that are unique to individual sub-groups, including their intersectionality

- Recommendation 3: further outreach be provided to federal departments and agencies in order to increase awareness of the range of policy, service and program options aimed at supporting a diverse workplace

- Recommendation 4: public service-wide approaches to career progression be explored including broadening access to existing successful programs and services such as the Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative and the Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology Program at Shared Services Canada

- Recommendation 5: concerted efforts across central agencies be undertaken to explore how we can learn from Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative and extend similarly targeted services and development opportunities to all employment equity groups including development programs and career support services that are specifically designed with, and for, employment equity groups

Appendix A – Methodology and data

In this paper, we relied on a Cox proportional hazards survival model to investigate the effect several variables have on the time to the first promotion and between 2 consecutive promotions for Canadian federal public servants. This type of model is generally used to look at the relationship between the “survival” of a subject and various explanatory variables. This type of analysis originates from research in the field of health sciences where the impact of various treatments for life-threatening conditions on the survival of patients are being compared. Due to technical similarities in experiment design and features of datasets, survival analysis has known considerable popularity beyond the narrow scope of health sciences, and it has been successfully used over a wide spectrum of research fields. It is particularly useful for social research aiming at following a subject until a certain event of interest occurs, and discerning the factors that predict the duration to that particular event. In our case, the event of interest is the promotion of a federal public servant. Our model allowed us to compare the survival times to promotion of members of an employment equity group to their counterparts.

Survival analysis has also been widely used in econometric modeling with respect to labour market analysis such as employee retention, career advancement, unemployment spells, and product life expectancy. Allison Milner et al. (2018) (English only) used survival analysis to identify employment characteristics associated with exiting work and assess if these were different for persons with disabilities versus those without disabilities. A paper by Daniela-Emanuela Danacica and Ana-Gabriela Babucea (2010) (English only) presented an application of survival analysis on the duration of unemployment using exogenous variables such as gender and age. More closely related to our work, Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Raphael C. Cunha, et al. (2015) (English only) used survival analysis to look at the impact of gender on the time of departure and time to promotion in academia.

Unlike logistic regression, which calculates the probability of an event happening based on explanatory variables, the response variable hi(t) in Cox Proportional Hazard models is the hazard function at a given time t. Therefore an underpinning assumption of our analysis is that all employees, regardless of employment equity status, are eligible to obtain a promotion at any given time. However federal public servants are only eligible to obtain a promotion if they are active in the pursuit of promotion opportunities. Our analysis of the propensities of the various employment equity groups to apply to staffing processes attempts to provide a better picture of the factors that may be at play behind promotion rates differentials across employment equity groups.

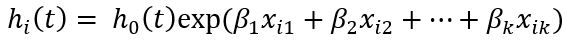

The model used in this analysis takes the form of

Text version

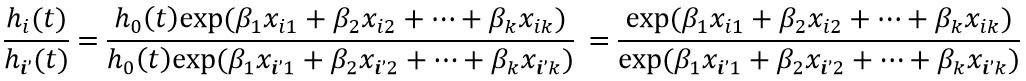

The function h underscript i at time t equals the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i.where h stands for the hazard function, x refers to a set of explanatory variables listed below and ranging from 1 to k, depending on each specification of the model, β represents the coefficients of these variables, the argument t stands for time, and the subscript i refers to a specific transaction (that is, a promotion or a waiting period leading to a separation) being described by the model. Here, h0(t) is the baseline hazard as hi(t) = h0(t) when all x’s are equal to zero. The baseline hazard is unspecified and can take any form. If we consider 2 different observation (i) and (i’), the hazard ratio given by

Text version

The fraction of the function h underscript i at time t to the function h underscript i prime (i’) at time t equals the fraction of the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i as the numerator and the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i prime (i’) as the denominator. Simplifying the equation by the common multiplier of the function h underscript 0 at time t, we get the fraction of the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i as the numerator and the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i prime (i’) as the denominator.is independent of time (t) and proportional across time. Not having to make arbitrary, and possibly counterfactual, assumptions about the form of the baseline hazard is a significant advantage of using Cox’s specification. Footnote 6

Observations

Due to a transition in data capture in April 1991, the dataset only contains employees hired into the public service after April 1, 1991, who are followed until their separation/retirement or until March 31, 2018. The rationale for the choice of the starting date is that, prior to the April 1991 transition, the data does not differentiate between a promotion and other types of staffing actions (such as new hires).

The time to promotion is calculated from the time of hire to the time of the first promotion, or the time between any 2 consecutive promotions. The main analysis considers promotions that occurred after April 1, 2005, for all public servants hired after April 1, 1991. This dataset consists of 409 381 observations from 230 310 indeterminate employees. These observations capture 172 125 waiting periods to promotions and 237 343 interrupted waiting periods. Interrupted waiting periods are periods of time (either since last promotion, or since hiring in cases where there was no promotion) which were interrupted either by a separation or by the end of the period under observation. Additional analysis includes comparing time to promotion for new hires for the following 2 time periods and cohorts:

- from April 1, 1991, to March 31, 2005 (112 667 indeterminate employees and 192 913 observations representing 74 762 waiting periods to promotions and 118 151 interrupted waiting periods)

- from April 1, 2005, to March 31, 2018 (141 836 indeterminate employees and 243 986 observations representing 97 856 waiting periods to promotions and 146 130 interrupted waiting periods)

This cohort analysis offers a secondary approach to test our benchmark results and thus improve our understanding of the progress, but also of its limits, that has been made in recent years.

The following variables were used in our benchmark model:

- Time: a continuous dependent variable, defined as length of time (in years) from being hired into the federal public service to first promotion, the length of time (in years) between 2 consecutive promotions or length of time with no promotion.

- Promotion: the event indicator, equal to 1 if the employee obtained a promotion; 0 otherwise.

- Women: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if indicated as such in the pay system; 0 otherwise.

- Visible minority: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the Employment Equity database by 2018; 0 otherwise.

- Indigenous people: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the Employment Equity database by 2018; 0 otherwise.

- Persons with disabilities: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the Employment Equity database by the end of the fiscal year the promotion was obtained; 0 otherwise.

- Age: a continuous variable, defined as age at hire or age at previous promotion

- Salary deciles: a dummy variable, derived from current salary of public servants who were not promoted and public servants’ salary before promotion for those who were promoted for each fiscal year. This was used as a proxy of seniority. The reference group selected was salary decile 1.

- Occupational categories: a dummy variable, based on Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada definitions. The reference group selected was the Executive Group.

- First official language: dummy variable, defined as 0 if Anglophone; 1 if Francophone.

- Bilingual bonus: a dummy variable, based on the requirements of the position and linguistic profile of the public servant. If the position is bilingual and the public servant meets the requirements of the position then 1; otherwise 0. For those who did not obtain a promotion, it is based on current position, for those who were promoted it is based on new position.

- National Capital Region: a dummy variable, defined as 1 if position is NCR; 0 otherwise. For those who did not obtain a promotion it is based on current position, for those who were promoted it is based on new position.

- Leave without pay: a continuous variable, defined as length of time (in years) that a public servant spent on leave without pay. For the public servants who were not promoted, it equates to all time spent on leave without pay throughout their career. For public servants who were promoted, it is the time spent on leave without pay from either the start of their career to promotion or the time spent on leave without pay between consecutive promotions.

Models

For this paper, we analyzed several models using a varying number of explanatory variables and interactions. Our benchmark model consisted of using all variables as listed above while considering promotions that occurred between April1, 2005, and March 31, 2018, for those hires on or after April1, 1991. The other models that we explored were:

- the benchmark model with leave without pay being removed from the set of explanatory variables

- the benchmark model augmented with factors capturing the interactions of pairs of employment equity statuses as well as of each employment equity status with age, first official language, bilingual status, National Capital Region, and leave without pay

- the benchmark model augmented with interactions between each employment equity status and occupational categories

For the same time period and explanatory variables as indicated above we also analyzed:

- promotions within the executive level (that is, an executive being promoted to a higher level executive position)

- promotions to the executive level or executive equivalent level from employees who held positions one level below the executive level

- promotions to the executive level from employees who held positions one level below the executive level

To leverage the existing dataset, the study also divides the time period in 2 almost equal sub-periods, from April 1991 to March 2005 and from April 2005 to March 2018. Given that the dataset only captures public servants hired after April 1, 1991, in order to ensure that the comparison between the 2 periods is consistent, only public servants hired after April 1, 2005, have been considered for the second period. Thus, this comparison between the 2 periods predominantly relies on promotions taking place at relatively early stages in a public servant’s career, and only reflects early career advancement.

Interpretation

Throughout the paper we refer to hazard rates as “promotion rates” for simplicity. This is not to be confused with other approaches, such as logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes, which calculates an event happening based on independent variables.

A hazard ratio (HR) is indeed a ratio and its interpretation in the context of this paper is as follows:

- HR = 0.5: at any particular time, half as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

- HR = 1: at any particular time, as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

- HR = 2: at any particular time, twice as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

The reporting of promotion rates in this paper is given as PR = HR -1. That means a (+) indicates a lower survival time (higher promotion rate) as compared to the reference groups and a (-) indicates a higher survival time (lower promotion rate) as compared to the reference groups.

Data

The dataset is derived from 2 internal data sources. The first data source, the Jobs-Based Analytical Information System, contains transactional data gathered from the government’s pay system since April 1990. This data source was used to identify promotions, as well as most of the explanatory variables used in the analysis, such as region and occupational category. The second data source, the Employment Equity Database, consists of representation data collected from employees on a voluntary basis through a self-identification questionnaire.

For the determination of employment equity status, women are identified through the federal government pay system. The other 3 groups are identified through the Employment Equity Database, which captures self-identification data collected from employees on a voluntary basis.

Appendix B – Model results

Table 6 reproduces the results of the different specifications of our model using our benchmark dataset of promotions having occurred after April 1, 2005, for all new hires after April 1, 1991.

| Parameter Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Model 1 (Benchmark model) |

Model 2 (Without leave without pay) |

Model 3 (Employment equity interactions with various covariates) |

Model 4 (Employment equity interactions withoccupation categories) |

|

| Women | 0.04236** | -0.04216** | -0.13106** | -0.02686 | |

| Visible minorities | 0.00592 | 0.00578 | 0.03258 | -0.12474* | |

| Indigenous people | -0.07813** | -0.08496** | -0.22836** | -0.10307 | |

| Persons with disabilities | -0.08218** | -0.11249** | -0.40268** | -0.21264* | |

| Administrative Support | 0.04476 | 0.04631 | 0.04495 | -0.0582 | |

| Administrative and Foreign Service | -0.24257** | -0.2238** | -0.24982** | -0.24982** | |

| Operational | -0.50778** | -0.525** | -0.54352** | -0.57539** | |

| Scientific and Professional | 0.04732* | 0.03409 | 0.03947 | 0.05091 | |

| Separate agencies | 0.71763** | 0.72906** | 0.71301** | 0.63635** | |

| Technical | -0.04295 | -0.03521 | -0.06489* | -0.06416 | |

| Age | -0.05214** | -0.04779** | -0.05403** | -0.0524** | |

| Salary decile 2 | -0.05363** | -0.0585** | -0.05564** | -0.05639** | |

| Salary decile 3 | -0.05616** | -0.05914** | -0.06118** | -0.05909** | |

| Salary decile 4 | -0.17646** | -0.16218** | -0.18242** | -0.17612** | |

| Salary decile 5 | -0.17998** | -0.19228** | -0.18598** | -0.17789** | |

| Salary decile 6 | -0.48187** | -0.48875** | -0.48558** | -0.47857** | |

| Salary decile 7 | -0.52217** | -0.53186** | -0.52565** | -0.51854** | |

| Salary decile 8 | -0.57681** | -0.56765** | -0.58088** | -0.57566** | |

| Salary decile 9 | -0.6833** | -0.66248** | -0.68551** | -0.68305** | |

| Salary decile 10 | -0.76263** | -0.72386** | -0.76227** | -0.76255** | |

| First official language | -0.06781** | -0.06409** | -0.03757** | -0.06999** | |

| Bilingual bonus | 0.17631** | 0.18483** | 0.16023** | 0.17566** | |

| National Capital Region | 0.49688** | 0.51886** | 0.40031** | 0.49907** | |

| Leave without pay | -0.35975** | -0.46955** | -0.35877** | ||

| Age*Women | 0.00221** | ||||

| Age*Persons with disabilities | 0.00978** | ||||

| Age*Visible minorities | -0.00085 | ||||

| Age*Indigenous people | 0.00421** | ||||

| Leave without pay*Women | 0.13385** | ||||

| Leave without pay*Persons with disabilities | 0.04585** | ||||

| Leave without pay*Visible minorities | 0.01091 | ||||

| Leave without pay*Indigenous people | -0.01694 | ||||

| First Official Language*Women | -0.07619** | ||||

| First Official Language*Indigenous people | 0.12077** | ||||

| First Official Language*Visible minorities | 0.08197** | ||||

| First Official Language*Persons with disabilities | 0.02808 | ||||

| Bilingual Bonus*Women | 0.0282* | ||||

| Bilingual Bonus*Indigenous people | -0.02061 | ||||

| Bilingual Bonus*Visible minorities | -0.04224* | ||||

| Bilingual Bonus*Persons with disabilities | 0.0008794 | ||||

| Women*National Capital Region | -0.1588** | ||||

| Indigenous people*National Capital Region | -0.02191 | ||||

| Visible minorities*National Capital Region | 0.03442* | ||||

| Persons with disabilities*National Capital Region | 12722 | ||||

| Women*Visible minorities | 0.05044** | ||||

| Women*Indigenous people | -0.01836 | ||||

| Women*Persons with disabilities | 0.01597 | ||||

| Visible minorities*Persons with disabilities | -0.00853 | ||||

| Indigenous people*Persons with disabilities | 0.0161 | ||||

| Administrative Support*Women | 0.13554** | ||||

| Administrative and Foreign Service*Women | 0.12239** | ||||

| Operational*Women | 0.04888 | ||||

| Scientific and Professional*Women | -0.032 | ||||

| Separate Agencies*Women | -0.02231 | ||||

| Technical*Women | -0.08527 | ||||

| Administrative Support*Visible minorities | 0.1845** | ||||

| Administrative and Foreign Service*Visible minorities | 0.10265 | ||||

| Operational*Visible minorities | 0.12972 | ||||

| Scientific and Professional*Visible minorities | 0.12172 | ||||

| Separate Agencies*Visible minorities | 0.72016** | ||||

| Technical*Visible minorities | 0.19286** | ||||

| Administrative Support*Indigenous people | -0.02016 | ||||

| Administrative and Foreign Service*Indigenous people | 0.03321 | ||||

| Operational*Indigenous people | 0.09738 | ||||

| Scientific and Professional*Indigenous people | -0.02192 | ||||

| Separate Agencies*Indigenous people | -0.03926 | ||||

| Technical*Indigenous people | 0.11425 | ||||

| Administrative Support*Persons with disabilities | -0.01459 | ||||

| Administrative and Foreign Service*Persons with disabilities | 0.17878 | ||||

| Operational*Persons with disabilities | 0.45936** | ||||

| Scientific and Professional*Persons with disabilities | 0.0624 | ||||

| Separate Agencies*Persons with disabilities | 0.30914 | ||||

| Technical*Persons with disabilities | 0.19256 | ||||

| *indicates estimate statistically significant at 5%, ** indicates estimate statistically significant at 1% | |||||

Appendix C – Groups in occupational categories

| Occupational category | Occupational group |

|---|---|

| Executive | EX – Executive |

| Executive Equivalent | AC 03 - Actuarial Science, AINOP 06/07/08 - Air Traffic Control, AOETP 01/02 - Aircraft Operations, AR 07 - Architecture and Town Planning, AS 08 - Administrative Services, AU 06 - Auditing, CO 04 - Commerce, CS 05 - Computer Systems, DE 03/04 - Dentistry, DS 05/06/07/08 - Defence Scientific Service, GX – General Executive, LA 02/03 - Law, LC - Law Management, LP 02/03/04/05 - Law Practitioner, MA 07 - Mathematics, MD 02/03/04/05 - Medicine, MT 08 - Meteorology, PC 05 - Physical Sciences, SEREM - Scientific Research, SERES03/04/05 - Scientific Research, SGPEM09 - Scientific Regulation, SOMAO13 - Ships' Officers, TI 09 - Technical Inspection, UT 04 - University Teaching, VM 05 - Veterinary Medicine, WP 07 - Welfare Program |

| Scientific and Professional | AC – Actuarial Science, AG – Agriculture, AR – Architecture and Town Planning, AU – Auditing, BI – Biological Sciences, CH – Chemistry, DE – Dentistry, DS – Defence Scientific Service, EC – Economics and Social Science Services, ED – Education, EN – Engineering and Land Survey, FO – Forestry, HR – Historical Research, LA – Law, LP – Law Practitioner, LS – Library Science, MA – Mathematics, MD – Medicine, MT – Meteorology, ND – Nutrition and Dietetics, NU – Nursing, OP – Occupational and Physical Therapy, PC – Physical Sciences, PH – Pharmacy, PS – Psychology, SE – Scientific Research, SG – Scientific Regulation, SW – Social Work, UT – University Teaching, VM – Veterinary Medicine |

| Administrative and Foreign Service | AS – Administrative Services, CO – Commerce, CS – Computer Systems, FI – Financial Management, FS – Foreign Service, IS – Information Services, OM – Organization and Methods, PE – Personnel Administration, PG – Purchasing and Supply, PL – Leadership Development Programs, PM – Program Administration, TR – Translation, WP – Welfare Program |

| Technical | AI – Air Traffic Control, AO – Aircraft Operations, DD – Drafting and Illustration, EG – Engineering and Scientific Support, EL – Electronics, EU – Educational Support, GT – General Technical, PI – Primary Products Inspection, PY – Photography, RO – Radio Operations, SO – Ships' Officers, TI – Technical Inspection |

| Administrative Support | CM – Communications, CR – Clerical and Regulatory, DA – Data Processing, OE – Office Equipment Operation, ST – Secretarial, Stenographic, Typing |

| Operational | CX – Correctional Services, FB – Border Services, FR – Firefighters, GL – General Labour and Trades, GS – General Services, HP – Heat, Power and Stationary Plant Operation, HS – Hospital Services, LI – Lightkeepers, PR – Printing Operations, SC – Ships' Crews, SR – Ship Repair |