National COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign – Horizontal Lessons Learned Review

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

1. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization announced that COVID-19 was a global health pandemic. In the days and weeks that followed, Health Canada saw a need for a volunteer inventory as a means to support the delivery of the response to this public health threat. Emphasis was placed on collaborating with provincial and territorial governments and international partners to minimize the economic, health, and social impacts of the pandemic.

2. When the campaign was developed in March – April 2020, the Government of Canada response was based on the following principles:

- Collaboration. Working in partnership to produce an effective and coordinated response.

- Evidence-informed decision-making. Decisions being made based on the best evidence available at the time.

- Proportionality. The response measures put in place should be appropriate to the level of threat.

- Flexibility. Actions taken should be tailored to the situation and evolve as new information becomes available.

- A precautionary approach. Timely and reasonable preventive action should be proportional to the threat and informed by evidence to the extent possible.

- Use of established practices and systems. Well-practiced strategies and processes can be rapidly ramped up to manage a pandemic.

- Ethical decision-making. Ethical principles and societal values should be explicit and embedded in all decision-making.

3. As part of the response, Health Canada, like other departments involved in the federal response, is working closely with provincial and territorial officials to support a comprehensive, coordinated approach to protecting public health and safety. As a need to support provinces and territories with their recruitment of volunteers was identified, Health Canada had recourse to the Public Service Commission (PSC) expertise in recruitment and staffing under the Public Service Employment Act, to support provinces and territories with their pandemic response volunteer recruitment efforts. This lead to the design and delivery of the COVID-19 National Volunteer Recruitment Campaign (the campaign).

Prime Minister of Canada statement

“We thank and continue to encourage Canadians to sign up for the National COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign, and other organizations – because large or small, each act makes a difference as we work together to fight this pandemic”

April 19, 2020

4. To oversee the campaign, Health Canada established a project team comprised of 6 employees. The team was led by the PSC‘s Director General, Staffing Support, Priorities, and Political Activities. PSC employees were assigned to Health Canada’s project team to develop, administer, and deliver the campaign. This team became the central liaison office between Health Canada and the PSC’s National Recruitment Directorate.

5. With 5 regional offices across Canada, the National Recruitment Directorate is the PSC’s program delivery organization. This directorate has experience administering large, national recruitment initiatives such as the Post-Secondary Recruitment Campaign and the Federal Student Work Experience Program.

6. On April 1 and 2, 2020, the National Recruitment Directorate team worked with internal stakeholders (i.e. Information Technology Services Directorate and the Data Services and Analysis Directorate) and Health Canada project team members to develop a volunteer recruitment campaign campaign poster (see Annex 1). The COVID-19 National Volunteer Recruitment poster was placed on the Government of Canada Jobs (GC Jobs) recruitment platform from April 2 to 24, 2020 and included the following opportunities:

- COVID-19 case tracking and contact tracing;

- Health system surge capacity; and

- COVID-19 case data collection and reporting.

7. The campaign resulted in the creation of an inventory of volunteers that could be referred to provinces and territories to support pandemic response efforts. When the poster closed on April 24, over 54,000 Canadians had applied and offered to contribute to Canada’s COVID-19 response.

8. Health Canada and PSC project team members collaborated to develop applications and tools to administer the volunteer inventory and respond quickly to provincial and territorial referral requests for individuals to address emerging needs. Within a few weeks, new web and Excel-based applications were developed to manage the referral process. An inventory management tool was also developed to enable quick key data and information searches to respond to referral requests and report on campaign progress. A volunteer referral tool was developed to support the quick identification of potential candidates with specific skills and experiences in a specific location to respond to requests. Finally, a referral management tool was developed that maintained records of all previous request responses.

9. This inventory was used to refer volunteer candidates to support pandemic response efforts in a number of areas – including in long-term care homes. To support the campaign in this capacity, the National Recruitment Directorate contacted students from the Federal Student Work Experience Program asking if they were interested in being considered for support aid jobs in long-term care facilities (CHSLD in Quebec) through the Canadian Red Cross. Students did not require a background in health to perform these tasks and these referrals began at the beginning of May. In addition, Post-Secondary Recruitment campaign applicants were contacted asking if they were interested in being considered for internal Canadian Red Cross positions related to marketing and human resources. Overall, 152 Post-Secondary Campaign applicants were referred to the Canadian Red Cross. However, none of the individuals referred were offered a position. Some of the reasons for this include candidates not being available to work the various work schedules as well as more qualified applicants from other sources being hired.

10. To oversee this initiative, a COVID-19 Recruitment Operations Centre (the Centre), that included representatives from the PSC and Health Canada, was established on April 1 and continued operating until August 31 using resources, infrastructure, and capacity already in place to support large-scale recruitment programs. The Centre was comprised of 3 areas of expertise:

- PSC’s Public Service National Recruitment Team. This team oversaw all operational aspects, including the delivery of the national volunteer recruitment campaign, outreach initiatives, screening, referrals, reporting, and responding to queries;

- PSC’s Provinces and Territories Liaison Team. This team was the main point of contact for provincial and territorial officials regarding the identification of resourcing needs. The team responded to questions in a timely manner. Key contacts for each jurisdiction were established to help expedite requests and ensure continuity of services; and

- Health Canada Project Team. This team was the strategic liaison between Health Canada and the PSC and worked with internal services, such as Communications, Human Resources, and Information Technology in the administration of the campaign. This team also managed a broader contact tracing response team in partnership with Statistics Canada, among other key stakeholders.

11. As the pandemic response evolved, the Canadian Red Cross became a partner of this initiative once the inventory had been created – specifically in Quebec and Ontario – to enhance the collective pandemic response capacity in these provinces. Seven PSC employees worked on interchange with the Canadian Red Cross to assist capacity-building efforts.

12. The PSC employees who were part of the Health Canada project team returned to their regular positions by the end of August 2020.

1.2 Objective

13. The objective was to conduct a horizontal lessons learned review of the actions taken to develop and administer the campaign and volunteer inventory used to refer candidates that could support pandemic response efforts across Canada. The review identified good practices and lessons learned that could be applied to plan actions and address a potential resurgence in COVID-19 cases or similar initiatives. The PSC Internal Audit and Evaluation Directorate led the horizontal lessons learned review with support, when required, from Health Canada’s Office of Audit and Evaluation.

1.3 Scope

14. The scope included activities undertaken from March 31, 2020 to August 31, 2020 to develop the campaign poster; manage the referral of candidates to provinces, territories and the Canadian Red Cross; and, to support use of the volunteer inventory.

1.4 Review questions and Methodology

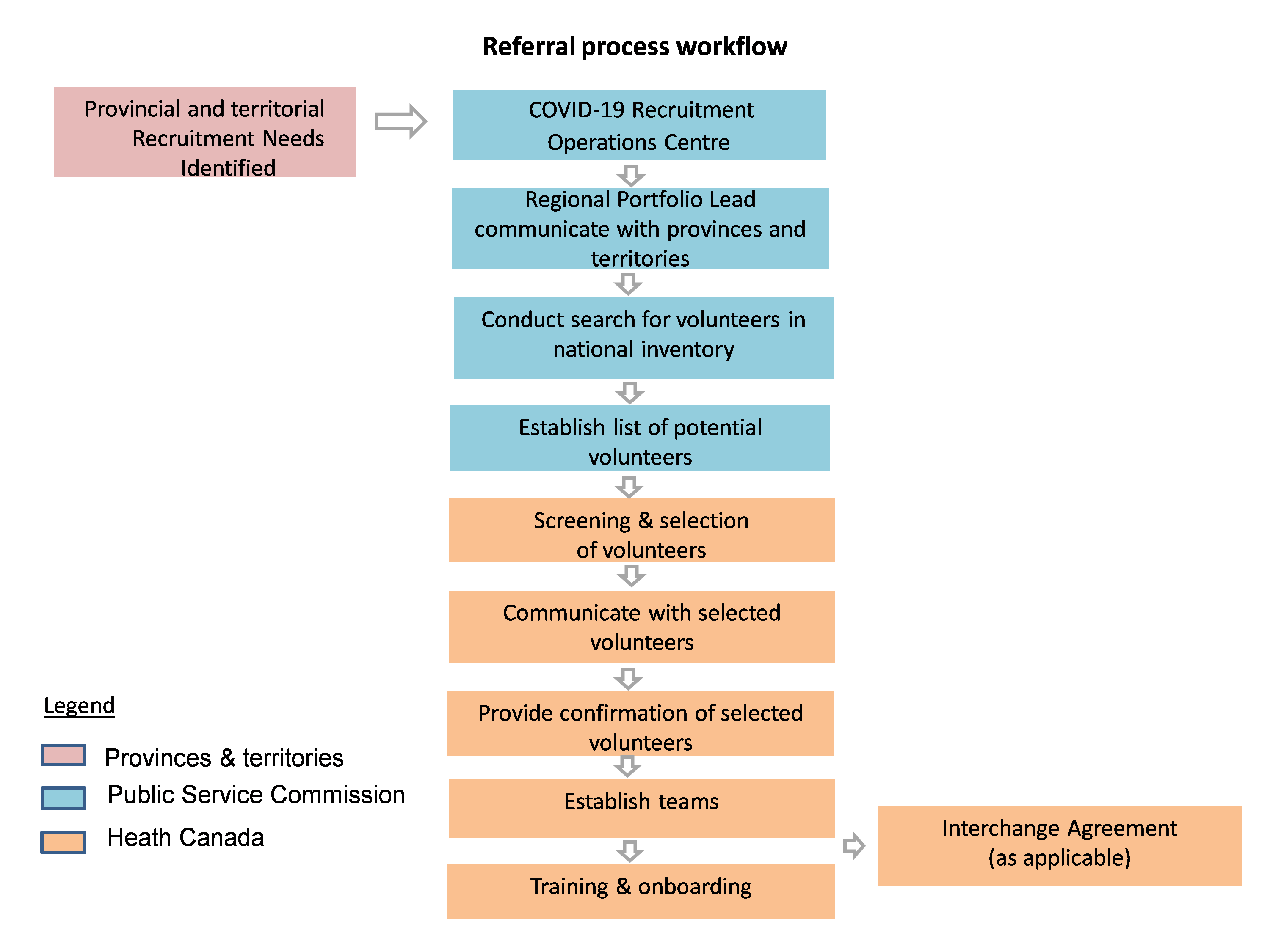

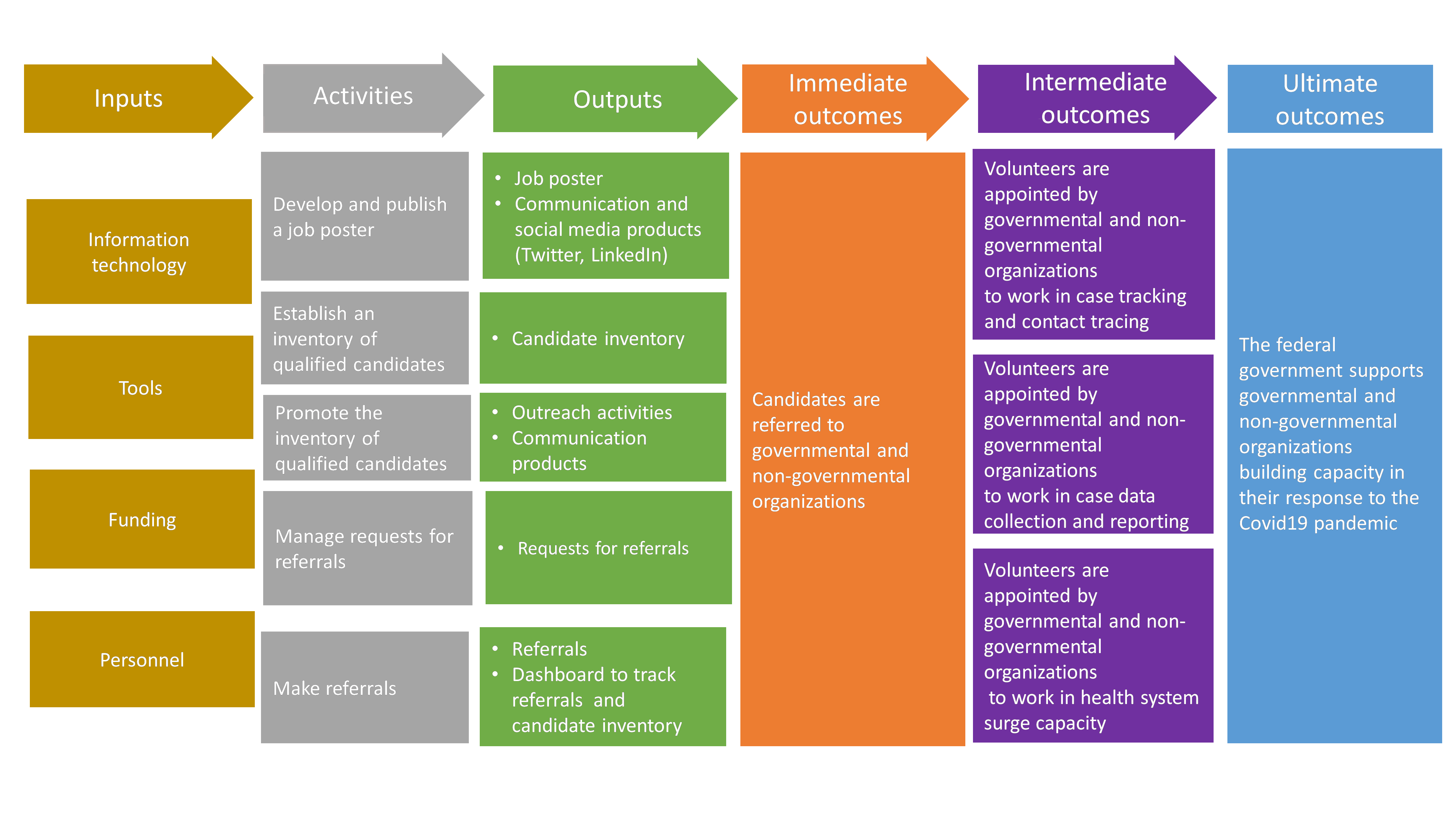

15. Based on the activities outlined in the referral process workflow (Annex 2) and the campaign’s logic model (Annex 3), the review focused on: governance and campaign coordination; application and referral processes; and, use of the inventory. These 3 areas were examined to identify good practices and lessons learned for consideration in response efforts to potential future waves or similar initiatives.

Methodology

16. The methodology included multiple lines of evidence as described below and are further elaborated in Annex 4.

17. Document review. The document review included Government of Canada COVID-19 announcements, and campaign-related documents provided by key stakeholders, including Health Canada, and PSC directorates.

18. Review of administrative and performance data. The review included obtaining and analyzing data from various sources, such as dashboards and campaign reports. This work was conducted in partnership with the Data Services and Analysis Directorate, the National Recruitment Directorate, Information Technology Services Directorate, and Health Canada’s Project Team.

19. Interviews and / or focus groups. Overall, 22 interviews were conducted with key internal and external campaign stakeholders. Internal representatives interviewed from the PSC included officials from the Data Services and Analysis Directorate (4), the National Recruitment Directorate (4), Information Technology Services Directorate (2), Communications and Parliamentary Affairs Directorate (1), Legal Services (1), and from the Health Canada Project Team (3) to obtain information on their experiences in delivering the campaign. Interviews with officials from the Provincial and Territorial Liaison Team (3), and external stakeholders including key informants from the provinces and territories (3), and the Canadian Red Cross (1) were conducted to gather their perspective on the administration of the campaign.

20. Two representatives from Health Canada’s Office of Audit and Evaluation were present on a rotational basis with the PSC’s evaluation team during interviews with Health Canada project office staff and external stakeholders.

21. Survey: A survey was sent to all 53,769 volunteers screened-in to the campaign to gather information about their experience. The survey launched on August 24, 2020 and ran until September 18, 2020. Overall, there were 10,768 respondents, which represents a 20% response rate.

2 Lessons Learned

2.1 The volunteer inventory

22. Overall, 54,248 applications were received from individuals from all provinces, territories, and overseas. In total, 53,769 applicants were screened into the inventory. Figure A represents the distribution of volunteer applicants by location. Table 1 provides an overview of applicants by first official language and table 2 represents the distribution by gender. Of note, 25,248 individuals indicated they have abilities in a language other than the 2 official languages. Furthermore, applicants were able to identify 4 specializations in their submissions. In total, 560 specializations were identified – ranging from software development and engineering to health sciences. Table 3 provides the top 10 specialities identified.

Text Alternative

| Location | Number of volunteers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Nunavut | 5 | 0% |

| Northwest Territories | 29 | 0% |

| Yukon | 59 | 0% |

| Prince Edward Island | 183 | 0.40% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 482 | 1% |

| New Brunswick | 515 | 1% |

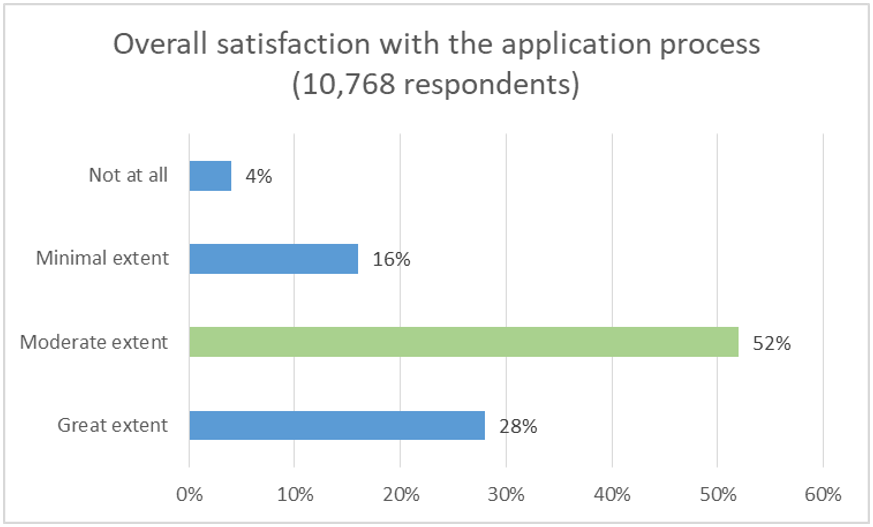

| Outside Canada | 702 | 0% |

| Saskatchewan | 992 | 2% |

| Manitoba | 1,153 | 2% |

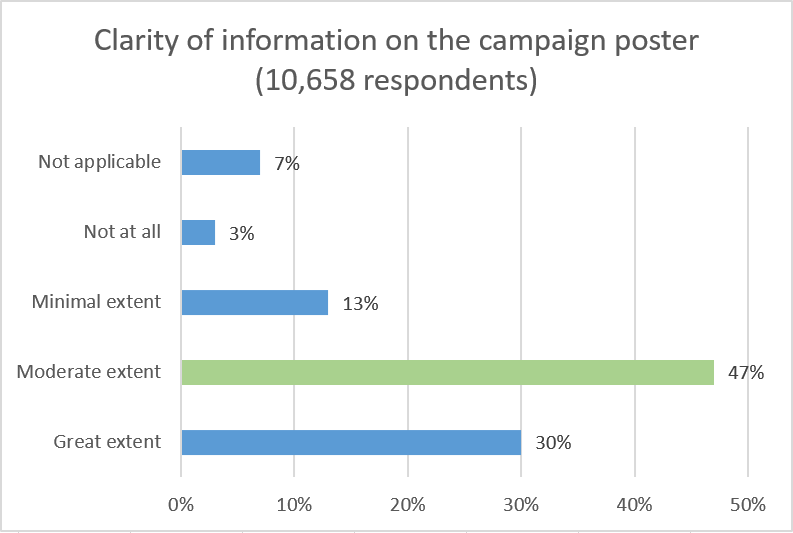

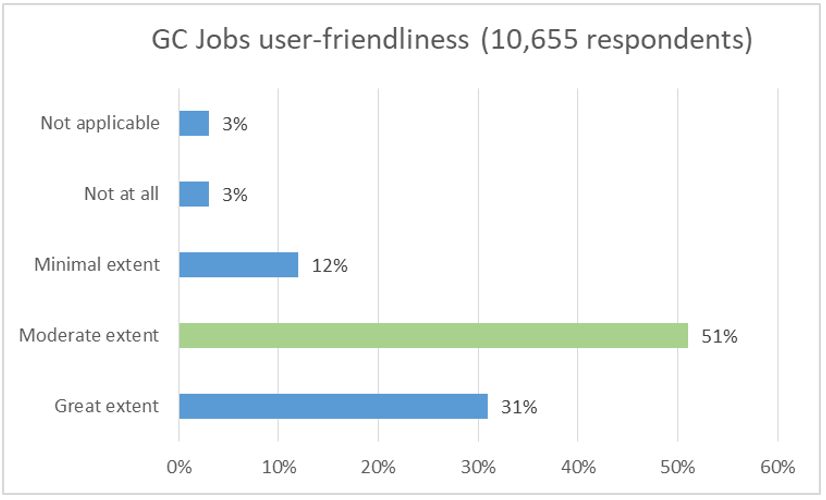

| Nova Scotia | 1,235 | 3% |

| Quebec (outside the National Capital Region) | 3,184 | 5% |

| National Capital Region | 4,757 | 10% |

| Alberta | 6,422 | 12% |

| British Columbia | 7,848 | 17% |

| Ontario (outside the National Capital Region) | 26,203 | 46% |

| First official language | Percentage | Number |

|---|---|---|

| English | 95% | 51,555 |

| French | 5% | 2,693 |

| Gender | Percentage | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 59% | 32,006 |

| Male | 35% | 18,986 |

| Prefer not to answer | 6.00% | 3,148 |

| Other | 0.00% | 108 |

| Specializations | Applicants |

|---|---|

| Health Sciences | 4,407 |

| Nursing | 3,049 |

| Business Administration | 2,961 |

| Medicine | 2,932 |

| Public Health and Hygiene | 2,881 |

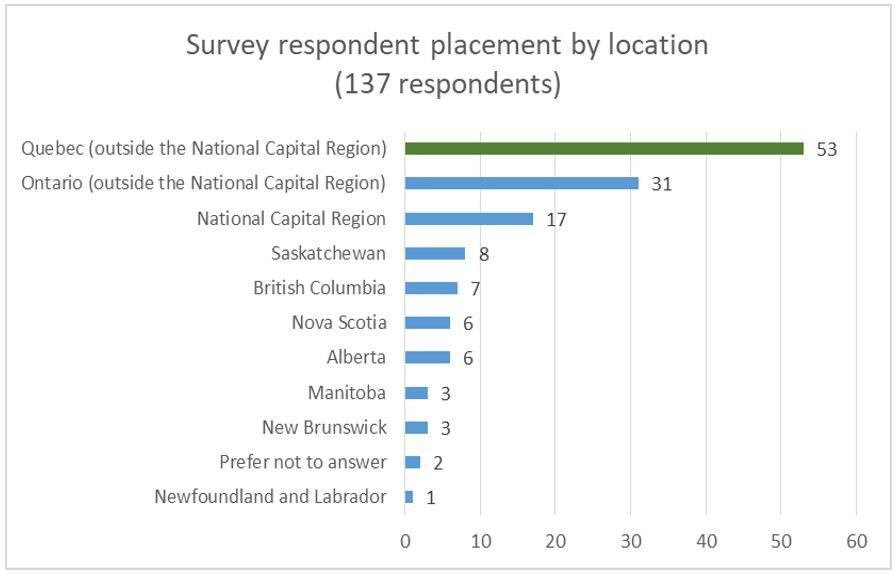

| Project Management | 2,541 |

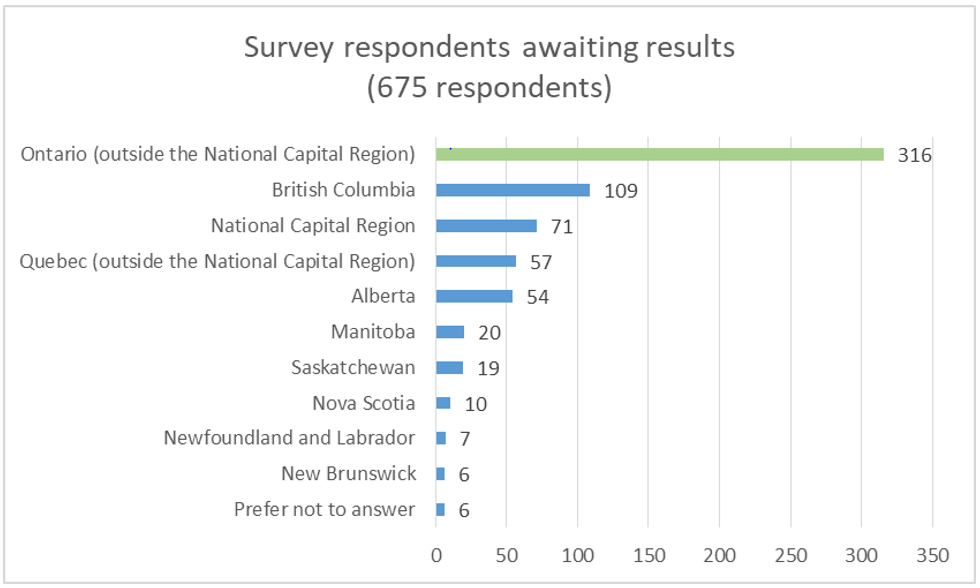

| Biomedical Sciences | 2,444 |

| Medical and Health Sciences | 2,348 |

| Computer Programming | 2,347 |

| Population Health | 2,250 |

23. In summary, the 53,769 individuals screened into the inventory includes representatives from all provinces and territories and a good cross-section of relevant skills and expertise. Annex 5 provides more demographic information on the inventory.

2.2 Governance and campaign coordination

Governance

24. The idea for the campaign came from the Health Canada COVID-19 task force, which was put in place to support the department’s contribution to the Government of Canada’s pandemic response. The idea was communicated by Health Canada representatives to the PSC at the end of March 2020 given the organization’s expertise in administering large-scale, national recruitment campaigns. When the request from Health Canada came in, the PSC’s Executive Management Committee acted quickly to assemble a Project Team and include campaign updates as a standing agenda item. The Acting Vice-President, Services and Business Development Sector provided daily updates to the Executive Management Committee on campaign administration and progress.

25. While the Executive Management Committee was the main strategic level governance body that oversaw PSC campaign activities, internal stakeholders interviewed noted that due to the urgency of getting the Project Team up and running, operational and tactical level governance and planning was not fully put in place up front. The initial focus was on getting the campaign poster out to support the quick development of an inventory of volunteers.

26. Shortly after the campaign poster was placed on the Government of Canada Jobs (GC Jobs) recruitment platform, team members assessed what governance elements were needed. Key elements considered included: having a liaison role between the PSC and Health Canada; developing and implementing tools to facilitate candidate referrals and performance reporting; and, including existing National Recruitment Directorate governance. An area of improvement identified by key internal stakeholders was to have their directorates involved earlier to assist in brainstorming and problem solving.

27. It was determined that using existing governance and individuals with experience managing large-scale recruitment activities would be best to support COVID-19 campaign delivery. For example, existing expertise was leveraged to respond to questions from volunteer applicants and external stakeholders. Individuals with experience in responding to questions from large-scale recruitment campaigns contributed significantly to the success of the campaign. Although, consideration should be given to the sustainability of such an endeavour, the implementation of a triage approach to provide timely responses to e-mail inquiries and using employees from all PSC offices across Canada has been identified as a good practice to ensure timely responses to requestors.

Good practice: Implementing a triage approach to respond to applicant and Health Canada questions led to the provision of timely information to requestors – both applicants and stakeholders. The approach was implemented by leveraging all 5 PSC offices across Canada.

28. A Director General-level committee was established on June 2, 2020. This committee was led by the Health Canada Project Team Director General and comprised of a number of PSC Directors General and staff. This committee contributed to information sharing, developing actions to improve campaign delivery, and served as an integration-type body that brought focus to key campaign issues such as: use of the inventory, development of applications, and performance reporting. The committee met weekly until the third week of August 2020 when the Project Team was winding down operations.

29. The review found that communications amongst sectors and team members internal to the PSC worked well to keep all stakeholders informed, particularly once the governance supporting campaign delivery became more established. Several internal interviewees noted that the lack of clear tactical and operational governance up-front created certain challenges regarding the ability to share information discussed at the Executive Management Committee and to have a common understanding of the needs and required activities across the organization; however, this was generally solved with the creation of the Director General-level committee.

30. Regular briefings were provided to the Executive Management Committee by the Acting Vice-President, Services and Business Development Sector and focused mainly on daily transactional issues. While a good flow of information from the strategic governance level occurred, some internal stakeholders mentioned that governance could have included briefings from other levels of senior management as well as individuals tasked with delivering the campaign. Their view was that this could have limited some of the re-work that had to be done, particularly as it related to the development of the tools and applications that supported campaign delivery.

31. Furthermore, it was mentioned that it might have been beneficial to have an external stakeholder (i.e. Health Canada official or Canadian Red Cross official) attend some of the Executive Management Committee briefings to support the provision of information from different perspectives to support decision-making.

32. It is important to note that the urgency surrounding the campaign’s development created a need for governance to adapt in order to accommodate the rapid development, administration and delivery of the campaign. The review was also informed that established approval processes and stages of governance were amended to facilitate efficient decision-making. These decisions, associated risks and mitigation measures were documented in daily Special Executive Management Committee meeting notes. The notes were approved at the meeting held on the subsequent day to ensure timely decision approvals.

Good practice: Having PSC employees join Health Canada on assignment and bring their large-scale recruitment expertise to the Project Team was a key success factor for this initiative.

33. In general, clear lines of communication were established amongst sectors working on the COVID-19 campaign, which supported timely decision-making. The urgency of the campaign allowed employees the opportunity to receive feedback and approval of changes in real time as new information was received. For example, legal advice was provided to the Project Team within a day, while this process could normally take a few days. All interviewees agreed that the efficient use of governance supported the timely delivery of the campaign and demonstrated that Health Canada and the PSC are capable of responding to rapidly changing environments and delivering timely, relevant services.

Roles, responsibilities, and collaboration

34. Existing relationships amongst PSC sector management teams helped establish clear roles and responsibilities during campaign development and implementation. Roles and responsibilities were established through consultation and were based on advice from internal partners, such as legal services, security, privacy and information technology teams. Key internal stakeholders have acknowledged that consultation with stakeholders such as the Data Services and Analysis Directorate should have occurred earlier as re-work incurred due to the timing in which they were brought into the campaign.

35. Key roles and responsibilities related to managing relations with provincial and territorial officials were established to create and manage a catalogue of external contact information. This led to the identification of portfolio leads, which were arranged by province and territory. This approach facilitated on-going communications with provincial and territorial officials regarding needs and referrals from the inventory.

Good practice: Effective collaboration and strong senior leadership support enabled the Project Team to act quickly to address this urgent public health situation.

36. At the same time, some internal stakeholders stated that a lack of shared understanding of strategic information regarding the campaign early on caused work to be duplicated and made coordination difficult. They indicated that with more consultation during the first few days of planning, these types of situations might be prevented in future initiatives. Furthermore, one internal stakeholder stated that for future initiatives, it would be important to consider that, as new stakeholders are added to existing working teams, their roles should be clearly defined and communicated at the time of their arrival to mitigate the risk of duplicating efforts.

Lesson learned: For the senior management team to be effective, clearly defining roles and responsibilities is important to ensure adaptability in a quickly evolving operational environment.

Challenges in determining results

External interviewees indicated that the national campaign’s inventory was used to supplement other provincial volunteer recruitment initiatives. This has been identified as an unintended benefit (or use) of the campaign’s inventory; however, it also presents a challenge regarding the ability to report on where volunteers were eventually placed.

For reasons such as this, determining an accurate account of all individuals placed from the campaign is difficult.

Campaign coordination

37. The Health Canada project team worked with provincial, territorial, and non-government organization (i.e. Canadian Red Cross) officials to provide information on the volunteer inventory, coordinate requests, and respond to questions. The project team maintained contact lists and held regular meetings with stakeholders to support efficient coordination of efforts. This team also integrated into broader pandemic response working groups led by Public Safety Canada and the Government Operations Centre. In addition, the PSC leveraged its regional offices to maintain contact with provincial and territorial representatives and to provide information to the Health Canada project team on regional needs based on these interactions.

38. PSC employees who worked on interchange with the Canadian Red Cross to assist capacity building efforts also served to augment the support provided to provinces and territories and increased the potential workforce that could fill gaps in resourcing at long-term care homes and address other urgent needs.

39. Given the exceptional circumstances surrounding the campaign where data collection systems, processes, and performance information were not established up front, the collection of consistent placement data from stakeholders proved to be challenging. While the PSC focused on developing tools to support the efficient provision of information on the number of referrals, the coordination with provincial and territorial officials on reporting on the campaign’s performance is considered an area that could have been further developed. Reliance was placed on obtaining data through provincial and territorial representatives at regular meetings. For instance, stakeholders were unable to distinguish between the sources or origins of those that they recruited, as this was not information that they typically collected.

40. Consequently, provincial and territorial stakeholders were not able to provide data to support performance measurement efforts. In light of this, it is not possible to provide an accurate account of placements made through this campaign using stakeholder data. In addition, some provincial interviewees indicated that the first time they became aware of the campaign was when they received a list of referred volunteers. To mitigate this risk in the future, consideration should be given to establishing a single point of contact for each external stakeholder and construct a mailing list to include these individuals to facilitate the dissemination of accurate and consistent information.

41. Internal stakeholders expressed the importance of managing this campaign well to mitigate potential reputational risks regarding recruitment excellence. It was recognized that an applicants’ negative experiences during one recruitment initiative could affect their trust in the effectiveness of future recruitment initiatives.

42. Unfortunately, the number of placements made by provinces and territories from the inventory was not available at the time this report was written, which limits the assessment of the overall success of the campaign. However, anecdotal information provides some indication of placements. For example, internal and external stakeholders emphasized that the ability to report on the number of volunteers placed was impacted by Canada’s decentralized public health sector. Challenges concerning placement data are discussed in more detail in section 2.4 (Use of the volunteer inventory) of this report.

Lesson learned: For future similar initiatives, it would be important to consider exploring options up front with all stakeholders on how to best track and report on performance data (i.e. number of placements).

2.3 Application and referral process

Provincial and territorial needs

43. On April 1 and April 2, the PSC’s National Recruitment Directorate worked with internal stakeholders and Health Canada project team members to develop the campaign poster. The poster launched on April 2, 2020 and identified the following needs: case tracking and contact tracing; health system surge capacity; and case data collection and reporting. The poster acknowledged that some provinces and territories had developed their own volunteer recruitment initiatives; therefore, applicants were asked not to apply to the campaign if they had previously registered as a volunteer in a provincial or territorial inventory.

44. Interviewees remarked that needs identified in the poster were developed, in a rapidly evolving period, based on the best available information at the time, particularly as it related to the importance placed on contact tracing to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to flatten the curve. As such, the poster was developed through an open approach. The poster did not ask for specific skillsets or experiences from potential volunteers; rather, it focused on recruiting volunteers with diverse backgrounds, expertise, experience, spoken language and flexibility in work hours. The review was informed that at the time of the poster’s launch, some awareness existed regarding what provinces and territories already had in place in terms of response strategies or measures. In addition, several interviewees mentioned that there could have been more consultations to further determine needs; however, the sense of urgency surrounding the campaign’s development made this difficult.

45. Subsequent to the launch of the campaign poster, it was recognized that some of the needs originally identified could not be performed by volunteers due to security and policy related challenges. Over time, the project team became aware that for some of the tasks, such as contact tracing, volunteers would require security clearances and access to government computer systems. While this precluded the use of volunteers without security clearances to perform this work, it is also a demonstration of the adaptability of the approach – once the need for security clearance was identified, the team managed to screen candidates who met the requirement.

46. External interviewees noted that while many candidates met the qualifications for specialized experience/expertise to work in “hot spots” or “red zones” (i.e. long-term care facilities), further consultation with institutions could have highlighted logistical challenges in the ability to place volunteers. For example, the Canadian Red Cross required volunteers to have proof of provincial healthcare prior to deployment. This resulted in an inability to place candidates despite them being successfully screened-in to the inventory. This is also despite the fact that the campaign’s poster did not list any further requirements beyond being a resident of Canada.

47. Additionally, some external interviewees highlighted that while the campaign led to the creation of a useful inventory of volunteers to help with pandemic response efforts, earlier stages of the pandemic response required public health organizations to prioritize unionized employees into front line positions such as, but not limited to, long-term care homes. One provincial / territorial representative acknowledged that their province / territory did not access the campaign inventory at first because their focus was on re-deploying public servants exclusively to assist in their pandemic response.

48. While recognizing that decisions were made with a sense of urgency, due to the evolving needs and scope of the campaign, having a greater precision of provincial and territorial requirements was identified as an area for improvement.

Lesson learned: For future similar campaigns, it would be beneficial to take more time to consult on needs and requirements to ensure that the created inventory can be used effectively.

49. Another provincial interviewee stated that in preparation of the anticipated second wave, and with the return to regular work for staff health care employees, the campaign inventory could serve as a valuable resource to help with further general pandemic response needs.

50. For future similar initiatives, internal and external stakeholders noted that having campaign posters that reflect both the general requirements and specific qualifications needed to cover the varying needs of provinces and territories should be included. Further clarity regarding provincial and territorial requirements for volunteers to be hired or placed to help with the pandemic response should be given in order for volunteers to clearly understand the requirements and responsibilities expected of them.

51. To do this, future large-scale volunteer recruitment efforts could look to adopting a volunteer management strategy to increase effectiveness and efficiency as they help to organize and coordinate the efforts of many volunteers. Using such a strategy could help support stronger alignment of volunteer inventories to needs and requirements.

52. As an example, the Generate, Educate, Mobilize and Sustain (GEMS) model is one approach that is used by volunteer organizations to administer volunteer programs. The model is acknowledged by the Council for Certification in Volunteer Administration as being consistent with widely held and highly effective practices by the broader volunteer administration community. Furthermore, the model has been developed to “assist extension professionals and volunteer coordinators to effectively administer volunteer programs without delivering the program themselves”. Due to the large-scale recruitment numbers that were generated by the campaign, and the inevitable coordination challenges amongst the various levels of government that were addressing urgent needs in a new, unpredictable operating environment, use of this model could support future volunteer campaign delivery.

Poster development and posting

53. The development and launch of the campaign poster was done in a 24-48 hour timeframe. Several interviewees identified this timeframe as a “record” for the creation of an application process. Collaboration, agility, and employee adaptability were identified as key success factors.

Good practice: Collaboration, agility, and employee adaptability were key success factors in the development and launch of a job poster that was created in 2 days and led to the creation of an inventory of over 53,000 volunteers within 22 days.

54. In addition, being able to expedite governance approvals and have increased access to decision-makers (i.e. Directors General and Vice-Presidents) allowed for progress throughout the poster’s development to be fast-tracked. This was acknowledged by several internal stakeholders as being critical to the timely development and launch of the poster.

55. While developing and placing the campaign poster on GC Jobs in 2 days was a highlight of the campaign; the short time line, as a result, limited the ability for consultations to occur with key internal stakeholders. Several PSC officials acknowledged that if they had been involved earlier in the process, the poster could have better facilitated the collection and reporting of data from applications. For example, the use of open text boxes to gather data from applicants created multiple lines of unstructured text that was difficult to work with. A solution presented was for future campaigns to use dropdown menus to gather data and facilitate the easy gathering of data that would allow for accurate data analysis and reporting. Consulting with data and information specialists early on could have limited the amount of re-work related to data and information management once the campaign poster closed on April 24, 2020.

Lesson learned: While the campaign job poster was launched in record time, it could have been better developed by including relevant internal stakeholders during the design phase to allow for better capturing of information and data and facilitate information analysis, management and reporting.

Applicants’ perspective

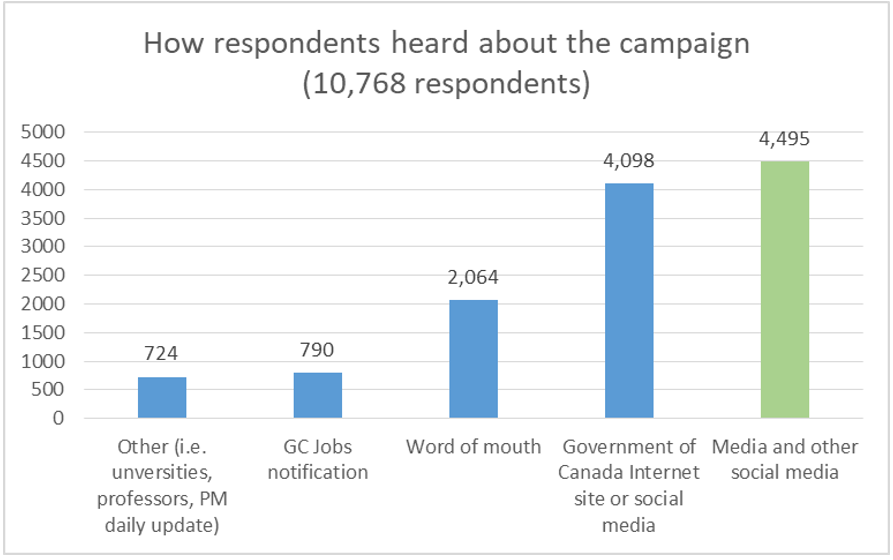

56. In general, survey respondents indicated that they heard about the campaign through media, social media, Government of Canada websites, and through word of mouth. In addition, the Prime Minister’s reference to the campaign at a daily public briefing in mid-April was also viewed as a key source of information on the campaign (See Figure B for details). It is also interesting to note that 68% of the 10,768 respondents did not have a GC Jobs account prior to submitting their application.

Text Alternative

| Response | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Other (i.e. unversities, professors, PM daily update) | 724 |

| GC Jobs notification | 790 |

| Word of mouth | 2,064 |

| Government of Canada Internet site or social media | 4,098 |

| Media and other social media | 4,495 |

57. Overall, 80 of survey respondents indicated they were moderately to greatly satisfied with the application process. This is a very positive response rate when considering the campaign poster was developed in such a short time on a system that over 2/3 of respondents had never used (See Figure C).

58. Survey respondents satisfied with the application process also shared positive views on communications they received. Specifically, respondents identified the use of e-mail and video conferencing tools as being effective and practical. Additionally, the use of video conferencing tools to facilitate face-to-face training allowed respondents the opportunity to understand their roles in the campaign. Furthermore, respondents described the people that interviewed them as being effective and detailed in their approach. Finally, respondents highlighted that once initial contact had been made via email, things moved quickly thereafter.

Text Alternative

| Overall satisfaction with application process |

Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Great extent | 28% | 3,046 |

| Moderate extent | 52% | 5,578 |

| Minimal extent | 16% | 1,718 |

| Not at all | 4% | 426 |

59. For the 20% of respondents that agreed to a minimal extent or not at all, the main explanations for their ratings related to:

- the time it took to apply;

- the requirement to provide personal information;

- challenges figuring out where information should be placed in the text boxes and updating information once submitted; and,

- the lack of communication received after submitting their applications.

60. The rapid creation of the campaign poster and lack of user experience with GC Jobs did not seem to affect applicant satisfaction with the process as it relates to the clarity of information on the campaign poster (see Figure D). Furthermore, applicants found the system to be user-friendly (see Figure E). Finally, the majority of respondents that had questions during the application process were satisfied with the responses they received (see Figure F).

Text Alternative

| Clarity of information on the job poster | Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Great extent | 30% | 3,200 |

| Moderate extent | 47% | 5,048 |

| Minimal extent | 13% | 1,354 |

| Not at all | 3% | 263 |

| Not applicable | 7% | 793 |

Text Alternative

| GC Jobs was user-friendly | Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Great extent | 31% | 3,339 |

| Moderate extent | 51% | 5,445 |

| Minimal extent | 12% | 1,263 |

| Not at all | 3% | 269 |

| Not applicable | 3% | 339 |

Text Alternative

| Responses to inquiries | Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Great extent | 14% | 1,447 |

| Moderate extent | 21% | 2,186 |

| Minimal extent | 11% | 1,151 |

| Not at all | 5% | 578 |

| Not applicable | 49% | 5,165 |

61. A majority of respondents indicated that the application process was clear, intuitive and satisfactory. Highlights of the application process that were identified are clarity of information on the poster and use of the GC Jobs recruitment platform. Although a majority of respondents indicated they did not have a GC Jobs account prior to applying to the Campaign, survey results displayed a majority of respondents found the recruitment platform to be user-friendly.

62. Those that responded to a minimal extent or not at all identified the following opportunities for improvement:

63. Timeliness of communications sent to applicants. Survey data analysis identified the primary contributor to applicant dissatisfaction was lack of communications. Many of those who received correspondence after submitting their application stated that it was not timely enough and that personal situations had changed from the time they applied to the campaign. Many volunteers stated they would have liked to have the opportunity to follow-up with the campaign to inquire on the status of their application. Specifically, whether or not they should continue to wait for a placement or, seek alternative ways to contribute to Canada’s response to the pandemic.

64. The Campaign did not feel like an “open call for volunteers”. Some volunteers felt that the campaign was biased towards individuals with university degrees in medically related fields. This resulted in some volunteers feeling as if their time spent applying was “wasted” as the poster had expressed a need for volunteers with diverse backgrounds and skillsets.

65. Difficulty in determining how they fit into the campaign. Perhaps a result of the previous observation, some volunteers stated that they had difficulty describing their skillsets in the context of an emerging pandemic. One comment acknowledged that determining if they “were an expert” was difficult to do. For example, one respondent stated that they were a dental hygienist with a skillset in infection control; however, in the context of COVID-19, they did not feel they should report themselves as such. This comment was explored during an interview with an external stakeholder who acknowledged, during additional screening processes, referrals from the campaign were identified as being able to contribute to provincial and territorial responses in more ways than they were able to convey in the national campaign’s application process.

66. One particular comment stated that they found it difficult to include their credentials from institutions from outside of Canada, and thus, it was difficult to provide correct information as the list only allowed for Canadian education institutions.

67. These opportunities for improvement are consistent with what we heard during interviews with internal stakeholders who stated that certain aspects of the poster were developed in ways that did not promote an efficient gathering of data relating to applicants (i.e. using open textboxes rather than pre-established dropdown boxes). As mentioned previously in this report, earlier involvement of data and information management staff might have mitigated these challenges.

Lesson learned: Keeping volunteers in the inventory informed of the status of the campaign is important to let them know how the inventory is being used and to communicate that their participation is valued. The lack of communications with applicants throughout the campaign was an area identified for improvement for future similar initiatives.

Communications related to placement opportunities

68. Literature on volunteer administration acknowledges that communication is key to ensuring ongoing engagement with volunteers. Failing to keep volunteers “in-the-loop” can lead to frustration and confusion, which ultimately leads to disengaged volunteers. In order to encourage strong communication with volunteers, having a communication strategy in place is important.

69. Communications sent out to volunteers should be engaging as well as meaningful. To this effect, organizations should rely on social media to facilitate communications with their volunteer base. Also important is ensuring that communications sent are necessary and relevant to keep volunteers engaged as opposed to providing volunteers with an abundance of unnecessary or irrelevant communications.

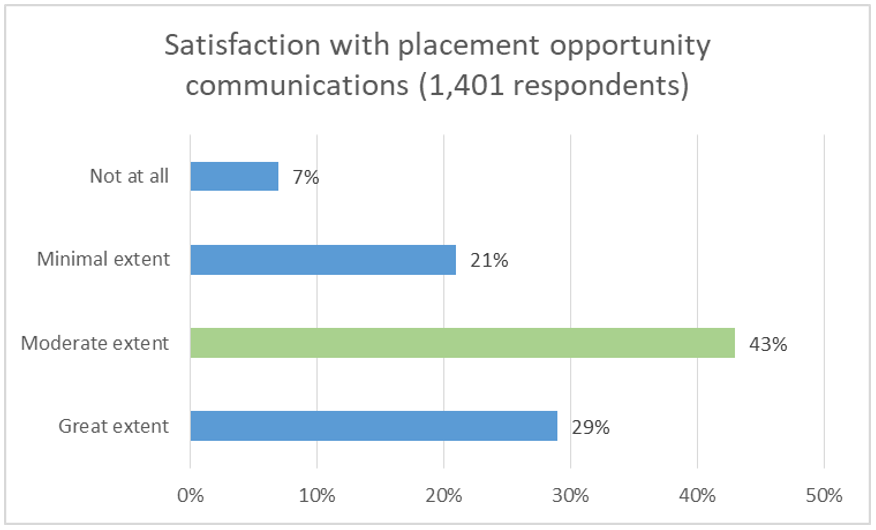

70. Internal stakeholders informed us that a generic response template was developed as questions / needs were identified by applicants. This was done to ensure the provision of consistent messaging to applicants – many of whom had the same types of questions throughout the campaign. As a result, a majority of survey respondents were satisfied with communications they received relating to potential placement opportunities (See Figure G).

Text Alternative

| Satisfcation with placement opportunity communications | Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Great extent | 29% | 412 |

| Moderate extent | 43% | 606 |

| Minimal extent | 21% | 290 |

| Not at all | 7% | 93 |

71. Respondents who indicated they were “not at all” satisfied with communications provided similar comments to those documented above and represented individuals who had not received communications directly from the campaign once they submitted their applications.

72. External interviewees found the level of communication from the Health Canada Project Team and PSC to be adequate and very helpful. These stakeholders commended the ability of Government of Canada officials to provide lists of referrals from the campaign in a timely fashion. However, they also mentioned that, from a provincial and territorial perspective, it was challenging to maintain communications due to increasing demands to maintain service delivery within their provincial and territorial contexts.

73. Provincial interviewees also acknowledged their inability to spend the time necessary to review lists of referrals, as well as, a limited ability to liaise with organizations within their province, and communicate with potential volunteers from the inventory who had been referred to them.

Lesson learned: For future similar initiatives, consideration could be given towards identifying ways to make referral lists sent to provinces and territories more intuitive and user-friendly. This could help to facilitate quick assessments of qualifications against requirements.

74. In planning for future waves of the pandemic or similar initiatives, focus could be placed on developing established lines of communication to keep provincial and territorial officials, as well as volunteers in the inventory engaged throughout the campaign in general, and referral processes in particular. Some respondents proposed a user-interface or application to display the progression of the campaign to the public. This suggestion aligns with additional comments made by survey respondents who stated that receiving the invitation to complete the survey (which included information on the campaign’s progress to date) was a welcomed update.

Lesson learned: Maintaining a volunteer recruitment web page that includes a status update on the campaign and provides a FAQ-type document would enhance communications with volunteers. Perhaps including a link on the job poster so that all candidates have access from the time they apply would be a good practice to follow.

Referral process

75. Based on data collected and maintained by the project team, the top requests for referrals by degree type were for nursing and / or medicine, nursing, medicine, all Footnote 1. The top requests by experience were for public health, personal support work and / or physician, personal support work, and all Footnote 2. This demonstrates that the first priority of provinces and territories that sought referrals was for individuals with public health, nursing, and medical experience.

76. Internal and external stakeholders stated that the PSC was able to provide candidates to provinces and territories in a timely fashion. In addition, the ability to align lists of candidates to the needs and qualifications of provinces and territories were also considered when sending lists of potential volunteers. However, as noted earlier, provinces and territories still experienced challenges in finding the time necessary to sift through the referral lists. The ability to leverage existing capacity and expertise within the PSC was considered by internal stakeholders to be a key success factor during the development and launch of the campaign, as was confirmed in responses received from provincial, territorial and Canadian Red Cross representatives.

77. According to the GEMS model, strong volunteer referral programs begin with targeted recruitment and identification. Volunteer identification involves developing a list of qualified candidates to be contacted based on organizational needs. Once it is determined how volunteers will fit into the organization, the GEMS model recommends determining what the organization expects from the volunteers. This action not only permits volunteers to enter pre-determined roles within the organization, but also determines what types of volunteers are required to fill roles.

78. Applicants who were successfully screened-in to the inventory would be identified by PSC officials using the Volunteer Screening Tool and then referred to provinces and territories based on identified external stakeholder requirements. Additional hands-on screening was offered to avoid having provinces and territories do this work. One external interviewee acknowledged that as beneficial as they believed the list of referrals were; they simply did not have enough time to dedicate to identifying specific candidates from the lists in order to refer them to local organizations seeking volunteers. They expanded on this by stating an orientation on how to effectively use/search the referral lists (sent as Excel files) could have allowed them to utilize the referral lists more effectively.

Lesson learned: For similar future initiatives, consideration could be given to hosting an orientation session early on, and periodically, as needed, with provincial, territorial, and other stakeholders to provide information on the list of volunteers and how referrals would be made, as well as on how the applications and tools developed could be easily or best used.

79. This proposed approach aligns with the literature on referral processes to promote effective recruitment of employees (or volunteers) in a timely manner. In addition, a majority of internal interviewees acknowledged that the ability to refer the amount of volunteers they did to provinces and territories in a timely manner was a success for the campaign; however, there are opportunities for improvements in future similar initiatives.

80. All external stakeholders interviewed noted they were very satisfied with the quality of volunteers referred to their organization.

2.4 Use of the volunteer inventory

Volunteer referrals and placements

81. The ultimate objective of creating the volunteer inventory was to place volunteers to support provincial and territorial pandemic response efforts. As mentioned earlier, official data on placements made by provincial and territorial authorities from the inventory are not available. Obtaining this data was not possible as local public health authorities made placements and existing systems did not allow for collection and reporting of the data. This resulted in an unstructured way to obtain data from stakeholders on placements. This review attempted to obtain further data than what was available through the administration of a survey to volunteers screened-in to the inventory.

82. Table 4 provides an overview of results from the August 2020 official campaign dashboard. Overall, a maximum of 24,717 individuals were referred from the inventory to provinces and territories, and 1,957 were referred to the Canadian Red Cross. While placement data from provincial and territorial public health authorities are not available, data received from a section of the Canadian Red Cross operating in Quebec, indicates that 93 placements from the inventory were made by the organization.

|

Collaboration with |

Collaboration with |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Volunteer Inventory |

24,717 individuals referred* |

11,025 individuals contacted |

|

Student Inventory |

Not applicable |

16,743 individuals contacted |

|

Post-secondary Inventories and Pools |

Not applicable |

141 individuals contacted |

|

|

Total |

|

|

Total of individuals contacted |

27,909 |

NA |

27,909 |

Total of individuals referred* |

27,800 |

24,717 |

3,083 |

* Referred numbers do not represent unique volunteers. Volunteers may have identified multiple skills and experience, as well as being willing to work in different locations, which also might result in them being referred multiple times prior to being placed.

83. In addition to the Canadian Red Cross placement numbers received, we asked survey respondents (n= 10,768) about their current status relating to the inventory. This led to the identification of 137 individuals who were placed as a result of the campaign and 690 volunteers who were awaiting placement results (see figure H). A further 574 individuals were contacted for placement opportunities but were no longer available. We can see in figure I that respondents were placed in nine provinces.

Text Alternative

| Current status of respondents | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Placed as a result of the campaign | 137 | 1% |

| Contacted but was no longer available | 574 | 6% |

| Contacted and awaiting placement results | 690 | 6% |

| Not contacted and no longer available | 1,403 | 13% |

| Not contacted and still interested | 7,964 | 74% |

Text Alternative

| Location | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 |

| New Brunswick | 3 |

| Manitoba | 3 |

| Alberta | 6 |

| Nova Scotia | 6 |

| British Columbia | 7 |

| Saskatchewan | 8 |

| National Capital Region | 17 |

| Ontario (outside the National Capital Region) | 31 |

| Quebec (outside the National Capital Region) | 53 |

84. Despite the fact that there have been some barriers in reporting on the status of volunteers, our survey results show that 690 volunteers from across most of the provinces had been contacted and were awaiting placement results as of September 14, 2020 (see figure J).

Text Alternative

| Location | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Prefer not to answer | 6 |

| New Brunswick | 6 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 7 |

| Nova Scotia | 10 |

| Saskatchewan | 19 |

| Manitoba | 20 |

| Alberta | 54 |

| Quebec (outside the National Capital Region) | 57 |

| National Capital Region | 71 |

| British Columbia | 109 |

| Ontario (outside the National Capital Region) | 316 |

85. As of September, 7,964 respondents indicated that they had not yet been contacted, but were still interested in volunteering. This is a positive indicator of the willingness of volunteers to participate in the campaign, and to lend their support to provinces and territories for future waves of the pandemic.

86. As part of the Gender-Based Analysis (GBA+) performed based on the survey results, we were able to identify the breakdown of volunteers that were placed by employment equity group, age group, gender, and first official language. This provides further insights into those that were placed to support pandemic response efforts across Canada.

87. As shown in table 5, the survey indicates representation from all 4 employment equity groups. Of the survey respondents, women and visible minorities made up a majority of the employment equity groups in both responses to the campaign as well as placements resulting from the campaign.

| Employment Equity groups | % Respondents | Number of respondents | % placements | Number of placements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 56% | 6,007 | 39% | 54 |

| Visible minority | 26% | 2,741 | 45% | 62 |

| Person with a disability | 5% | 555 | 4% | 6 |

| Aboriginal | 1% | 151 | 4% | 5 |

88. The age of respondents were evenly distributed for the most part, with the majority identifying as “60 and over” (see table 6). This is in contrast to literature published by Statistics Canada in 2015 on volunteerism in Canada that identifies individuals between the ages of 15 and 24 as being most likely to seek volunteer opportunities. It should be noted that respondents “24 and under” represented the second largest group of respondents.

89. A key takeaway is the willingness of Canadians to contribute to the pandemic response regardless of age group.

| Age | Placed | % of Placed | Respondents | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 and under | 18 | 13% | 1,516 | 14% |

| 25 to 29 | 17 | 13% | 1,157 | 11% |

| 30 to 34 | 18 | 13% | 1,113 | 10% |

| 35 to 39 | 26 | 19% | 1,037 | 10% |

| 40 to 44 | 19 | 14% | 812 | 8% |

| 45 to 49 | 13 | 9% | 864 | 8% |

| 50 to 54 | 10 | 7% | 891 | 8% |

| 55 to 59 | 7 | 5% | 977 | 9% |

| 60 and over | 9 | 7% | 2,401 | 22% |

| Total | 137 | 100% | 10,768 | 100% |

90. In terms of gender groups, females made up the majority of respondents (64%) placed into roles because of the campaign (see table 7). These percentages are representative when compared to the make-up of the inventory that was 62% female, 37% male and less than 1% other. This data aligns with multiple academic papers published on gender diversity in volunteering.

| Gender | Placed | % Placed | Respondents | % Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 77 | 56% | 6,907 | 64% |

| Male | 58 | 42% | 3,638 | 34% |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 1% | 176 | 1.60% |

| Other | 1 | 1% | 47 | 0.40% |

91. Table 8 illustrates the distribution of respondents by official language, where English-speaking respondents made up the vast majority of respondents. These numbers are also reflected in the make-up of the inventory as a whole (95% English speaking and 5% French speaking). However, this data reflects first official language only and not individuals who identified as bilingual.

| First official language | Placed | % Placed | Respondents | % Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 90 | 66% | 10,279 | 95% |

| French | 47 | 34% | 489 | 5% |

92. The data generated by the survey responses will be added to the data collected by the Health Canada Project Team and PSC officials to get a better understanding of the applicants’ profile for this and any future campaign.

93. Survey respondents placed due to the campaign expressed high levels of satisfaction regarding their placements. Specifically, respondents highlighted that the campaign has provided an opportunity to engage in challenging and dynamic work, while using previously acquired skills. In addition, respondents expressed that the campaign provided opportunities to gain valuable professional experience while contributing to provincial and territorial emergency response efforts. Respondents mentioned that they wanted to continue participating in pandemic response efforts even after their initial placement ends. Finally, one respondent highlighted that because of their placement, they now realize this line of work is very interesting to them.

Volunteers for future similar initiatives?

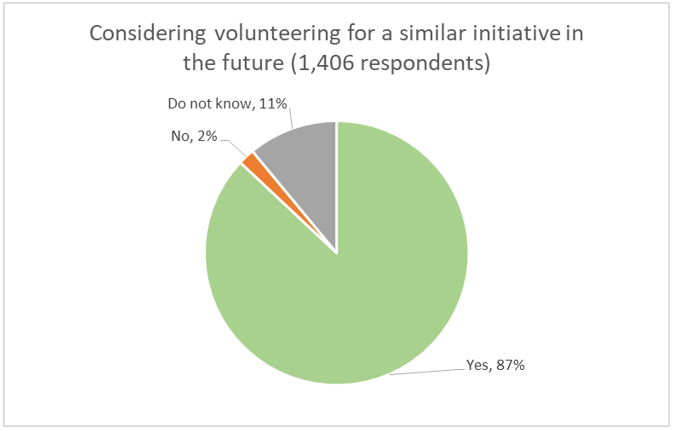

94. When survey respondents were asked if they would consider volunteering to contribute to similar future initiatives – 87% stated that they would (See Figure K). This is a positive indicator that volunteers currently in the inventory are willing to contribute to support provincial and territorial pandemic response efforts.

95. This is also positive because the external stakeholders that were interviewed for this review mentioned that volunteers are still needed. Provincial stakeholders interviewed noted that moving into the next stages of their pandemic response; they still consider the campaign inventory as a great resource of volunteers who could help with general volunteer needs and services.

Text Alternative

| Response | Percentage | Number of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 87% | 1,219 |

| No | 2% | 27 |

| Do not know | 11% | 160 |

How can the PSC apply some of the tools developed during the campaign?

96. When asked whether replicating the campaign volunteer inventory model was possible for other large scale recruitment campaigns, internal stakeholders explained that under specific conditions the ability to screen, refer and track individuals hired and placed from inventories using the same methods as the volunteer campaign was possible. Internal stakeholders explained that with an additional few weeks spent on re-situating aspects of the application and tool functionality, they could help with the management of inventories currently established by the Federal Student Work Experience Program and the Post-Secondary Recruitment campaigns. However, the effectiveness of using these tools and applications to support these established campaign inventories would depend on the nature of the campaign poster, among other things.

97. Also noted during internal stakeholder interviews, one issue that would have to be addressed for the PSC to benefit from the innovative practices employed during the campaign is the allocation of resources to further develop the tools and applications through the Information Management and Information Technology Plan prioritization.

98. Internal stakeholders noted that Information Technology Services Directorate capacity during the pandemic response focused on keeping PSC operations running and supporting the temporary measures put in place to support government-wide staffing. This made it difficult for the Directorate to allocate scarce resources to adapt the referral tool to other initiatives. Furthermore, during the campaign, there was insufficient time for the Directorate to fix bugs that appeared during application development process and, as a result, the Health Canada Project Team had to revert to using manual methods to collect data for reporting purposes.

99. Multiple internal stakeholders informed the review team that the experience of working on the campaign has proven that the PSC has the ability and expertise to conduct large-scale recruitment campaigns in a timely and efficient manner. It was also noted that the tools and expertise used could be transferred to other large-scale campaign campaign posters and staffing processes administered by the PSC. One Internal stakeholder acknowledged that the sense of urgency surrounding the campaign helped to fast track certain innovations that had been in development for other staffing campaigns and awaiting decision. For example, adding the status of applications within a specific inventory was built into the campaign and could now be integrated into other large-scale, national recruitment campaigns.

Conclusion

100. The COVID-19 National Volunteer Recruitment Campaign has been described as an innovative solution to a complex and unprecedented situation. Both internal and external stakeholders have credited the campaign as being an excellent initiative to support provinces and territories in their pandemic response. Furthermore, the campaign has highlighted the abilities of Health Canada and the PSC to quickly shift focus and mobilize efforts towards a common goal.

101. The ability to develop and launch a campaign poster in 2 days that led to the creation of an inventory of over 53,000 volunteers within 24 days that included a cross-section of individuals from across the country with relevant skills and experience has been highlighted by all stakeholders as a significant accomplishment.

102. In both Health Canada and the PSC, governance structures adapted swiftly to accommodate the rapid development, administration and delivery of the campaign by speeding up approval processes and procedures to facilitate efficient decision-making. While at the same time maintaining good records of meeting notes that documented risks, mitigation strategies, and approvals in a timely manner.

103. While we know through the survey responses that the inventory led to placements of volunteers in 9 provinces; the total number of placements made from the inventory by provincial and territorial authorities is not available. Local authorities made placements; however, the existing system did not allow for collection of the data at the provincial or territorial level. This limits the ability of this review to fully assess the success of the campaign. Overall, internal and external stakeholders were satisfied with the efficiency, timeliness and administration of the campaign, as well as with the quality of the candidates in the inventory and those referred to support provinces and territories in their pandemic response. Moreover, the survey responses revealed that the positions in which volunteers were placed were dynamic and challenging, while providing valuable professional experience for those placed into roles.

104. Furthermore, of the 10,768 respondents to our survey, we were informed that 137 individuals had been placed in nine provinces, 574 had been contacted to volunteer but were no longer available, and 690 had been contacted and were awaiting placement information. We also know that a section of the Canadian Red Cross operating in Quebec made 93 placements from the inventory as of August 2020. Interview data from external stakeholders indicated that individuals from the inventory have made a difference across the country in supporting pandemic response efforts.

105. This report identified good practices and lessons learned from administering the volunteer recruitment campaign during the first wave of the pandemic response. Based on the information gathered, it has been expressed that the campaign was successful in developing an inventory of almost 54,000 Canadians, which has led to some placements across the country to support overall efforts. The observations made in this report will assist planners and service delivery individuals in developing solutions to help provinces and territories in responding to subsequent waves of the pandemic.

Annex 1 – Campaign poster

Reference number: PSC20J-017558-000696

Selection process number:

RecrutementNational-COVID19-NationalRecruitment

Volunteer Recruitment

Various locations across Canada

Non remunerated as this is for volunteers

Closing date: 24 April 2020 - 23:59, Pacific Time

Who can apply: Persons residing in Canada.

Important messages

National COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign - We need you!

The Government of Canada is working with provincial and territorial governments to respond to COVID-19. We are seeking volunteers to help in the following areas:

- 1. Case tracking and contact tracing;

- 2. Health system surge capacity;

- 3. Case data collection and reporting.

We are building an inventory of volunteers from which provincial and territorial governments can draw upon as needed. We welcome ALL volunteers as we are looking for a wide variety of experiences and expertise. Please note that we have included a list of Yes/No questions that you will be asked to answer to so we can better match the volunteer work to be assigned.

Should you be interested in volunteering, here is some key information for you:

- Most of the work can and will be performed remotely from your home;

- Hours of work are flexible and schedules will be established based on needs and availabilities provided.

We thank you in advance for helping protect the health of Canadians.

Note: Some jurisdictions have already asked for applications to cover surge capacity. If you have already applied directly to a call-out from your province, please do not apply to this national process. This will help to cut down on processing applications more than once.

Positions to be filled: Number to be determined

In order to be considered, your application must clearly explain how you meet the following (essential qualifications)

Please complete the questionnaire in your application in order to be considered.

The following will be applied / assessed at a later date (essential for the job)

Various language requirements

Information on language requirements

Other information

The Public Service Commission will collect your personal information for the purposes of recruiting volunteers for provincial and territorial public services to assist the COVID-19 response. We urge you to take note of the Privacy Notice Statement of the GC Jobs website. By providing your application to become a volunteer, you consent to the collection, use and disclosure of your information with the provincial and territorial authorities solely for the purpose of their needs of recruiting volunteers for the COVID-19 response.

It is to be noted that the use of the GC Jobs website for this posting is for the recruitment of volunteers in provincial and territorial public services and not for employee or volunteer positions within the Government of Canada.

Please note that the preference mentioned below applies to federal public service positions only. It does not apply to this volunteer recruitment campaign.

Preference

Preference will be given to veterans and to Canadian citizens, in that order, with the exception of a job located in Nunavut, where Nunavut Inuit will be appointed first.

Information on the preference to veterans

We thank all those who apply. Only those selected for further consideration will be contacted.

For questions about the COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign

cfp.recrutement-covid-19-recruitment.psc@cfp-psc.gc.ca

Text Alternative

Referral process workflow

Provincial and territorial recruitment needs are forwarded to the PSC's COVID-19 Recruitment Operations Center.

The PSC regional portfolio lead communicates with the provinces and territories.

The PSC searches the national inventory for volunteers and then establishes a list of potential volunteers.

Health Canada screens and selects volunteers and then contacts the selected volunteers.

Health Canada provides confirmation of the selected volunteers and establishes teams. Health Canada provides training and onboarding.

An Interchange agreement is signed, as applicable.

Text Alternative

The inputs of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- Information technology

- Tools

- Funding

- Personnel

The activities of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- Develop and publish a job poster

- Establish an inventory of qualified candidates

- Promote the inventory of qualified candidates

- Manage requests for referrals

- Make referrals

The outputs of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- Job poster

- Communication and social media products (Twitter, LinkedIn)

- Candidate inventory

- Outreach activities

- Communication products

- Requests for referrals

- Referrals

- Dashboard to track referrals and candidate inventory

The immediate outcomes of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- Candidates are referred to governmental and non-governmental organizations

The intermediate outcomes of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- Volunteers are appointed by governmental and non-governmental organizations to work in case tracing and contact tracing

- Volunteers are appointed in governmental and non-governmental organizations to work in case data collection and reporting

- Volunteers are appointed in governmental and non-governmental organizations to work in health system surge capacity

The final outcomes of the COVID-19 national volunteer recruitment campaign are:

- The federal government supports governmental and non-governmental organizations building capacity to the COVID-19 pandemic

Assumption: The National COVID-19 Volunteer Recruitment Campaign was developed and administered as a result of needs for volunteers identified and expressed by provinces, territories and non-governmental organizations across Canada.

Annex 4 - Review matrix

| Questions | Indicators | Methods |

|---|---|---|

1. To what extent does the campaign poster reflect provincial and territorial needs at the time it was developed? |

1.1 Extent to which the provinces and territories were consulted in the development of the campaign poster. 1.2 Extent to which the campaign poster was developed based on the anticipated needs of the provinces and territories. |

|

2. To what extent was the campaign poster developed and posted in a timely fashion? |

2.1 Extent to which the campaign poster was developed in a timely fashion. 2.2 Extent to which the campaign poster was posted in a timely manner. |

|

3. To what extent were volunteers satisfied with the application process? |

3.1 Degree of satisfaction of volunteers with the application process. |

|

4. To what extent were volunteers satisfied with communications they received related to potential placement opportunities? |

4.1 Degree of satisfaction of volunteers with the communications they received related to potential placement opportunities |

|

5. To what extent is the Public Service Commission satisfied with the delivery (i.e., the development and posting of the of the campaign poster; the administration of the application and referral processes; and the use of the inventory) of the recruitment campaign? |

5.1 Degree of satisfaction of the Public Service Commission with the delivery of the recruitment campaign. |

|

6. To what extent is Health Canada satisfied with the delivery of the recruitment campaign, as well as with the student inventory provided? |

6.1 Degree of satisfaction of Health Canada with the delivery of the recruitment campaign. 6.2 Degree of satisfaction of Health Canada with the student inventory provided. |

|

7. To what extent have the Public Service Commission and Health Canada been able to provide referrals to stakeholders in a timely fashion? |

7.1 Extent to which the Public Service Commission and Health Canada has been able to provide referrals to key stakeholders. 7.2 Extent to which the Public Service Commission and Health Canada has been able to provide referrals in a timely fashion. |

|

8 To what extent has the volunteer inventory been used across Canada? |

8.1 Number of placements as a result of the campaign. 8.2. Barriers to the actual use of the volunteer inventory

|

|

9. To what extent are the appropriate governance structures and processes in place and working as intended to support the delivery of the campaign? |

9.1 Degree of appropriateness of governance structures and processes in place to support the delivery of the campaign. 9.2 Extent to which the governance structures and processes in place are working as intended to support the delivery of the campaign. |

|

10. To what extent have the design and administration of the campaign led to innovations that could be applied for other large scale recruitment campaigns? |

10.1 Extent to which the campaign design helped respond to the need for volunteers who could support pandemic response efforts across Canada. 10.2 Evidence that the design and administration of the campaign have led to innovations that could be applied for other large scale recruitment campaigns. |

|

Annex 5 - Information on the individuals in the inventory

| Studying or have a degree in: | Individuals |

|---|---|

Computer Science, Information Management and Information Technology |

8,071 |

Mathematics and Statistics |

6,117 |

Laboratory (Viral, Bacteria, etc.) |

4,707 |

Community Health |

4,650 |

Public Health |

4,383 |

Medicine |

4,325 |

Nursing |

3,322 |

Epidemiology |

2,871 |

Infectious Disease |

2,454 |

Community Medicine |

1,863 |

Emergency Management |

1,465 |

Surveillance |

1,114 |

Public Health Inspection |

762 |

Veterinary Medicine |

549 |

| Job Category | Initial Available Volunteers** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Experience | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 6,082 | 4,448 | 0 | 10,530 | |

| Community Health | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 2,939 | 1,708 | 0 | 4,647 | |

| Health Administration and Management | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 15,192 | 9,775 | 4 | 24,971 | |

| Medicine | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 3,063 | 2,342 | 0 | 5405 | |

| Nursing | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 1,584 | 1,737 | 1 | 3,322 | |

| Personal Support | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 3,477 | 2,639 | 1 | 6,117 | |

| Science and Research | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 6,950 | 3,422 | 0 | 10,372 | |

| Skills Outside of Health Sector | Bilingual | English Only | French Only | Total |

| 23,048 | 15,574 | 2 | 38,624 | |

** Please note that these numbers do not represent unique volunteers. Volunteers may have identified multiple skills and experiences, as well as being willing to work in different locations, which also might result in them being referred multiple times prior to being placed.