Results of the System-Wide Staffing Audit: Final report

Integrity of the federal public service staffing system

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Summary of findings on compliance: organizational staffing systems and appointments

- Summary of findings on the staffing environment

- Summary of recommendations

- Organizational staffing systems

- Appointments

- Areas for improvement

- Conclusion

- Moving forward

- About the audit

- Annex A: Audit findings and supplementary exhibits

- Annex B: List of departments and agencies included in the System-Wide Staffing Audit

Introduction

Mandate and authority

The Public Service Commission (the agency) is responsible for promoting and safeguarding a merit-based, representative and non-partisan public service in collaboration with its stakeholders.

Under the Public Service Employment Act, the agency has exclusive authority to make appointments to and within the public service. The agency delegates appointment authorities to deputy heads through the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument.

Oversight of the federal public service staffing system, as a model of shared accountability between the agency and deputy heads, is further emphasized in the act’s preamble. The agency may conduct audits on any matter within its jurisdiction and on deputy heads’ exercise of their delegated authorities.

Interim System-Wide Staffing Audit reports

The agency published interim reports on the results of a questionnaire administered to sub-delegated persons and staffing advisors in March 2018, and on the results of our review of organizational staffing systems in September 2018.

See “About the audit” at the end this report for more information about how the audit was conducted.

As part of the New Direction in Staffing, the Public Service Commission reviewed its approach to oversight. In line with our accountability to Parliament for the integrity of the staffing system, we transitioned our oversight towards the whole of the system instead of cyclical organizational audits.Footnote 1

The renewed oversight model consists of a variety of tools, such as the System-Wide Staffing Audit, horizontal risk-based audits, and the Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey, which serve to strengthen our accountability to Parliament.

These tools measure the overall compliance and performance of the federal public service staffing system against legislative, regulatory, and policy requirements, as well as the intended outcomes of the Public Service Employment Act.

This audit represents our first comprehensive review of system-wide compliance in staffing. In all, 25 departments and agencies participated in the audit, providing a sample of 386 appointments.

The audit had 3 objectives:

- to determine compliance with respect to organizational staffing system requirements

- to determine compliance with respect to requirements during the appointment process and for appointments

- to gauge stakeholder awareness and understanding of requirements, and of their roles and responsibilities

Results of the audit are organized accordingly, starting with compliance on organizational staffing systems, followed by compliance on the appointment processes and on the appointments, culminating in our questionnaire findings on stakeholders’ awareness and understanding of requirements and of their roles and responsibilities.

Summary of findings on compliance: organizational staffing systems and appointments

Overall findings indicate full compliance with staffing system requirements, with all 25 participating departments and agencies having made the changes to their staffing systems as required by the New Direction in Staffing. With regard to appointments, we found high levels of compliance with legislative, regulatory and policy requirements with respect to merit, consideration of persons with a priority entitlement, and appointment related authorities (Attestation Form and Oath/Solemn Affirmation). The audit also points to some areas for improvement, however, particularly related to official languages obligations and the application of the order of preference.

Exchanges with participating departments and agencies suggest that a lack of awareness and understanding is the primary cause of non-compliance in applying the order of preference. As for official languages, many of the discrepancies identified between the English and French versions of key staffing documents (assessment tools) point to a lack of quality control on the part of delegated departments and agencies.

Finally, some appointments were not supported with sufficient information. Although departments and agencies were subsequently able to provide the required information for a majority of appointments, in some cases, the required information could not be provided, and as a result compliance could not be determined.

Refer to Annex A for supplementary information on requirements and related compliance findings. For certain observations, exhibits are included to provide illustrative examples of non-compliance.

Summary of findings on the staffing environment

A questionnaire was administered to staffing advisors and hiring managers associated with the sample of appointments covered by the audit to gauge their awareness and understanding of their organizational appointment framework. Our results revealed general awareness and understanding of their framework’s requirements, but only a modest indication of staffing culture change at the time of the audit.

Summary of recommendations

Establishment of direction and requirements for organizational staffing systems

Recommendation 1: The Public Service Commission should clarify in the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument that the authority to establish the direction and requirements is to be retained by the deputy head. It should also determine whether newly appointed deputy heads are expected to review any pre-existing direction and requirements to ensure they continue to meet the organization’s needs and the strategic direction with regard to staffing intended by the new deputy head.Footnote 2

Greater awareness and understanding of staffing requirements

Recommendation 2: The Public Service Commission should support departments and agencies to ensure greater awareness and understanding of legislative, regulatory and policy requirements, particularly with respect to Section 39 of the Public Service Employment Act relating to the order of preference.

Quality control of staffing documents in relation to official languages

Recommendation 3: The Public Service Commission should support departments and agencies to ensure that official languages obligations are respected throughout the appointment process.

Sufficient documentation to explain appointment decisions

Recommendation 4: The Public Service Commission should clarify its expectations regarding information required to explain appointment decisions.

Organizational staffing systems

At the organizational level, we found that all 25 participating departments and agencies had established the New Direction in Staffing framework requirements. Specifically, as of April 2016, deputy heads were required to:

- establish direction, through policy, planning, or other means, on the use of advertised and non-advertised appointment processes

- establish requirements for sub-delegated persons to articulate their selection decision in writing

- have an attestation form signed by sub-delegated persons that includes, at a minimum, the statements found in Annex C of the revised Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument

The New Direction in Staffing highlighted the discretion in staffing that allows departments and agencies to adapt their resourcing strategies to their needs and operating context. By requiring deputy heads to establish direction and requirements, the Public Service Commission’s intent is for deputy heads, who are accountable for staffing in their organization, to set the strategic direction and clarify their expectations with respect to how such discretion is to be exercised within their organization.

As conveyed in our interim report Results of the System-Wide Staffing Audit: Organizational Staffing Systems,Footnote 3 one organization opted to sub-delegate these authorities. Upon our review of the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument, we determined that it was open to interpretation regarding the possible sub-delegation of these authorities. As a result, the organization’s approach was understandable. This led to our first recommendation, which we reproduce in this report for the reader’s convenience.

Appointments

The audit examined 386 randomly selected appointments to determine compliance with legislative, regulatory and policy requirements including:

- consideration of persons with a priority entitlement

- official languages obligations

- merit

- order of preferenceFootnote 4

- other appointment related authorities

For some requirements, information required to support appointment decisions was not available. In some cases, a lack of supporting documentation precluded determination of compliance. This was particularly so for the application of the order of preference (14.3% of appointment processes) and official languages equivalency in assessment tools (13.5% of appointment processes). Given these observations, proper documentation of appointment processes and related decisions will be the subject of our fourth recommendation.

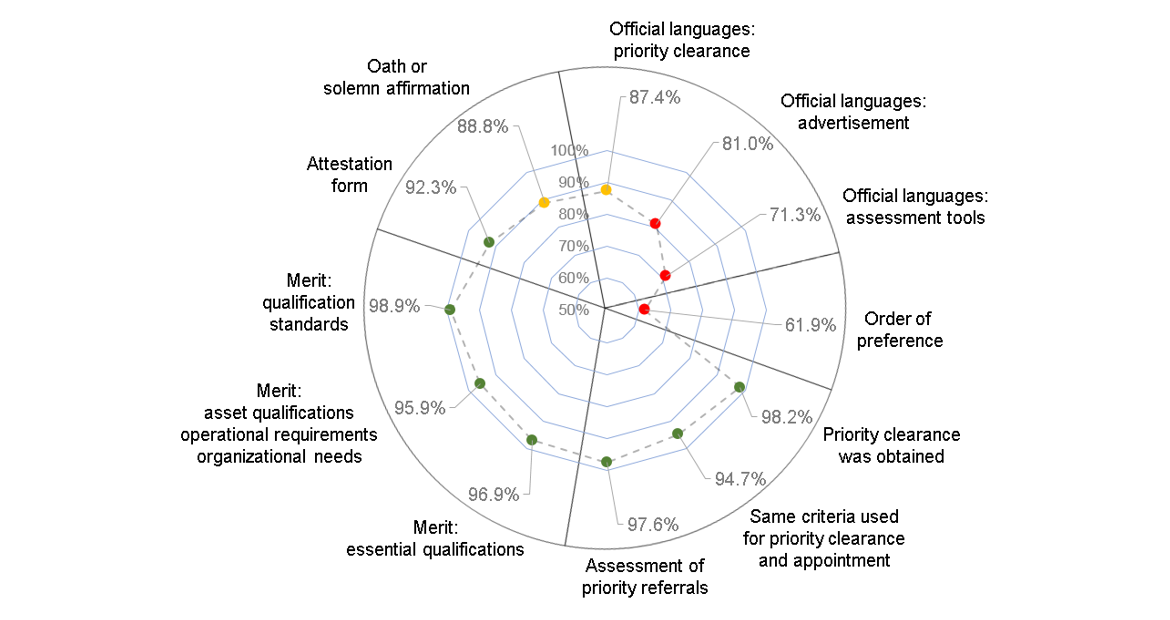

Figure 1 indicates that overall compliance on staffing requirements is generally high with respect to proper consideration of persons with a priority entitlement, merit and other appointment related authorities.

Figure 1: Compliance rates by requirement

Text Alternative

Areas of higher compliance:

- Priority Considerations

- Merit

- Appointment Authorities

Areas for Improvement:

- Official Languages Obligations

- Order of Preference

Rates:

- Official languages: priority clearance 87.4%

- Official languages: advertisement 81.0%

- Official languages: assessment tools 71.3

- Order of preference 61.9%

- Priority clearance was obtained 98.2%

- Same criteria used for priority clearance and appointment 94.7%

- Assessment of priority referrals 97.6%

- Merit: Essential qualifications 96.9%

- Merit: Asset qualifications operational requirements organizational needs 95.9%

- Merit: Qualification standards 98.9%

- Attestation form 92.3%

- Oath or solemn affirmation 88.8%

For example, compliance on merit was in excess of 95% for all requirements. Similarly, priority clearance was obtained for nearly all appointments where clearance was required (98.2%). Also, where persons with a priority entitlement were referred for consideration, we found that persons referred were assessed, as required, in nearly all the appointment processes (97.6%).

Despite these positive results, the audit also revealed areas for improvement. As shown in Figure 1, official languages requirements, with compliance rates ranging between 71.3% and 87.4%, as well as requirements relating to order of preference (61.9% compliance) are 2 areas where improvement is needed.

These compliance findings, combined with the results of the audit questionnaire, as well as our exchanges with participating departments and agencies, suggest that action is required in the following areas:

- awareness and understanding of staffing requirements

- quality control of staffing documents in relation to official languages

- documentation to explain appointment decisions

In the following sections, we will explore each of these areas for improvement and action and provide examples of how they contribute to lower compliance.

Areas for improvement

Awareness and understanding of staffing requirements

What we found

- The order of preference was not respected in 5 external advertised appointment processes (23.8%), meaning that another qualified candidate was appointed ahead of an eligible veteran or Canadian citizen.

- In 20 appointments, the oath or solemn affirmation was not taken on or before the date of the appointment as identified in letters of offer.

Throughout the audit, discussions with participating departments and agencies provided some insight into the causes of non-compliance across requirements. Based on our review of compliance and discussions with organizational representatives, we noted that non-compliance was often due to a lack of understanding with respect to staffing requirements. For example, this was the case with the requirement for hiring managers to demonstrate that appointees meet asset qualifications applied in an appointment decision. Another example was the requirement for new public servants to subscribe to the oath or solemn affirmation on or before the date of the appointment.

Lack of awareness and understanding of requirements was also observed with regard to the order of preference, where 38% of external appointment processes were either non-compliant (23.8%) or lacked adequately supporting documentation to determine compliance (14.3%). Recent changes to the public service staffing system regarding preference were intended to provide employment opportunities for veterans and to provide hiring managers with greater access to this pool of qualified candidates. Non-compliance with respect to preference requirements can deprive veterans and Canadian citizens of job opportunities for which they may be eligible.

This leads to our second recommendation:

Quality control of staffing documents in relation to official languages

What we found

In 45 advertised appointments processes (19%), we found differences between the French and English versions of the advertisement.

Exhibit

In the advertisement for an external advertised appointment process to fill a junior position providing telecommunications services, the English version included the following essential experience qualification: “Recent experience supporting at least one or more of the following telecom systems…” whereas the French version of the advertisement indicated “Expérience récente du soutien à l'égard d'au moins 2 des systèmes de télécommunications suivants…”.

Differences between the French and English versions of documents at key stages of the appointment process, such as job advertisements or assessment tools, can have an impact on applicants’ access to federal public jobs, as well as on the outcome of appointment processes.

The lack of effective quality control within departments and agencies to ensure accuracy and completeness of staffing information is an enduring issue that has been identified in previous audits. Over the years, the Public Service Commission has issued recommendations to a number of deputy heads to pay greater attention to the linguistic equivalence of key staffing documents in relation to both official languages. Reported compliance rates for official languages requirements in this audit confirm that these problems persist.

This leads to our third recommendation:

Sufficient documentation to explain appointment decisions

Exhibits

- In an internal advertised appointment process to fill senior management level positions, the organization was unable to provide assessment and results information to demonstrate how one of the persons appointed met the experience, education, knowledge or competencies of the position.

- In an external non-advertised appointment process, the narrative assessment was incomplete as it did not assess any of the 6 personal suitability qualifications identified for the position, including creativity and attention to detail.

According to the 2018 Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey, 87.9% of managers reported that the administrative process to staff positions within their department or agency were burdensome to a moderate or great extent.

For accountability purposes, persons with sub-delegated staffing authorities must ensure that decisions at key stages of the staffing process are well documented. As discussed in previous sections, some staffing requirements were not sufficiently documented to allow a determination of compliance. This points to another area where improvement is needed.

The need for staffing to focus on outcomes, including quality of hire, and less on process served as the impetus for the New Direction in Staffing. Reduced policy requirements introduced through New Direction in Staffing were designed to provide greater discretion in staffing and to ease some of the burdens associated with staffing. This includes a reduction in required documentation associated with streamlined policy requirements.

As noted in our recent Survey of Staffing and Non-Partisanship, 87.9% of hiring managers still feel that the administrative process to staff positions is burdensome. We are mindful of the need for a responsive staffing system. For this reason, it is important to note that documentation does not need to be overly burdensome if focussed on the information needed to demonstrate how requirements are met.

During our review, departments and agencies frequently noted a lack of clarity as to how information requirements outlined in Annex B of the Public Service Commission’s Appointment Policy are to be interpreted and applied.

This leads to our fourth recommendation:

Staffing environment under the New Direction in Staffing

The 2018 Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey found that 93% of staffing advisors indicated being well-informed about the New Direction in Staffing, compared with 61% of managers.

Although not directly comparable to the audit questionnaire results, 46% of managers reported that, to a moderate or great extent, the New Direction in Staffing has made staffing simpler within their department or agency.

As part of the audit, we administered a questionnaire to sub-delegated persons and staffing advisors who participated in our review of sampled appointments. The questionnaire, along with discussions with participating departments and agencies, were instrumental in providing insights into potential causes of non-compliance. It also provided an opportunity to explore stakeholder awareness and understanding of the New Direction in Staffing.

The majority of stakeholders were aware of the New Direction in Staffing, with staffing advisors reporting a higher rate of full understanding than sub-delegated persons. For example, 74% of staffing advisors indicated having a full understanding of the requirement for deputy heads to establish direction on the choice of appointment process, compared with 58% of sub-delegated persons.

These results are echoed in our recent Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey where 93% of staffing advisors reported being well informed about the New Direction in Staffing, compared with 61% of hiring managers. Although caution should be exercised when comparing responses across the audit questionnaire and the Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey, both sources indicate that hiring managers were less aware of the New Direction in Staffing than staffing advisors.

Lower awareness of the New Direction in Staffing on the part of hiring managers is not in keeping with the notion that sub-delegated managers are accountable for their staffing decisions. The preamble of the Public Service Employment Act emphasizes that the delegation of staffing authorities — and thus accountability for staffing — be to “as low a level of possible.”

The audit questionnaire also sought stakeholder views regarding staffing culture change since the implementation of the New Direction in Staffing in April 2016, including:

- transition towards a simplified staffing approach (for example, reduction of administrative burden)

- latitude for sub-delegated persons to apply their judgement when staffing

- increased focus on outcomes (finding the right person) and less on process

- greater ability on the part of hiring managers to customize approach in a given staffing situation

Staffing advisors were generally more likely than sub-delegated persons to perceive cultural change in staffing. And although sub-delegated persons indicated having more room to apply judgement when staffing, only 16% reported perceiving a shift towards simplified staffing. More encouragingly, the more recent Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey results indicate that nearly 46% of managers reported that the New Direction in Staffing had simplified staffing within their organization.

Hiring managers’ improved view of the simplified approach to staffing suggests that the New Direction in Staffing may have allowed for some progress. Whether progress will be sustained over the coming years will be the subject of future system-wide staffing audits and our second Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey in 2019-20.

Achieving the goals set out by the New Direction in Staffing requires cultural change. This change requires that the individuals who are sub-delegated staffing authorities take greater accountability and responsibility for staffing decisions — with human resource professionals playing a strategic and supporting role.Footnote 5

Conclusion

Overall, the audit found that all 25 participating departments and agencies had implemented required changes to their appointment framework. With respect to appointments, we observed high levels of compliance for requirements regarding consideration of persons with a priority entitlement, merit and other appointment related authorities. However, the audit did identify areas for improvement. It concludes that efforts should focus on improving system-wide awareness and understanding of staffing requirements; improved quality control of documents in relation to official languages; and having sufficient documentation to explain appointment decisions.

The recommendations included in this report are intended to support system-wide improvements in staffing across the federal public service. We invite all deputy heads to consider our audit findings and recommendations to identify areas within their own organizational staffing systems that may require further monitoring or action. In keeping with the principle of shared accountability for the integrity of staffing, deputy heads may wish to pay special attention to our recommendation on official languages obligations throughout the appointment process.

Moving forward

To address the findings of the System-Wide Staffing Audit, the Public Service Commission will implement a number of measures. We will start by amending the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument to clearly define delegated and sub-delegated authorities, and to refine documentation requirements in the Appointment Policy.

We recognize the need for a common understanding and application of staffing-related legislative and policy requirements, including documentation requirements. As such, we will work with the Canada School of Public Service to ensure issues raised in the audit are thoroughly covered in the staffing-related training programs for HR assistants, HR advisors and hiring managers. We will also continue to work with departments and agencies through our staffing support advisors and regional offices. In particular, we will reach out to the managers’ community to help them understand the importance of legislative and policy requirements, such as the order of preference and the oath. Through this collaboration, we will also reinforce a culture change that contributes to establishing more agile staffing processes.

Supporting veterans in finding employment in the public service continues to be an area of focus for the Public Service Commission. We will consider building additional functionality as we transform the GC Jobs platform to facilitate the application of the order of preference in the appointment process. Information could potentially be captured on a real-time basis, ensuring that veterans are always provided the preference they are entitled.

Our current system of advertising to persons with a priority entitlement separately can result in inconsistencies between the essential qualifications and conditions of employment that apply to them, and those that apply to other candidates. The Public Service Commission continues to work towards a single-tier hiring process where persons with a priority entitlement self-refer. We hope this approach will reduce opportunities for discrepancies, to ensure all candidates, including those with a priority entitlement, are provided with the same information and are assessed using the same criteria regarding a job vacancy.

The lack of progress in consistency between the official languages in the staffing process thus far signals that we need to seek alternative approaches. We have partnered with the National Research Council of Canada to examine the feasibility of developing innovative solutions to assess the equivalency between the English and French versions of statements of merit criteria in job postings.

However, fully addressing this issue will require broader support from across the public service. We will need cooperation and engagement from all departments and agencies to build control measures into their staffing processes. We will explore conducting real-time reviews of job advertisements and report the results directly to deputy heads. If no noticeable progress is made following these efforts, we will ask departments and agencies to monitor and report on language equivalency in a more structured way.

The Public Service Commission will establish a work plan to achieve progress, providing regular updates to departments and agencies as we advance on these actions, and continuing to engage with stakeholders to integrate their views into solutions.

About the audit

Audit objectives

The objectives of the System-Wide Staffing Audit were:

- to determine progress on implementing the New Direction in Staffing requirements

- to assess adherence to the Public Service Employment Act and other applicable statutes, the Appointment Policy, and the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument

- to gauge stakeholders’ awareness and understanding of New Direction in Staffing requirements as well as their roles and responsibilities

Scope and methodology

The audit covered the period of April 1, 2016, to November 30, 2016.

The audit methodology included the following:

- review and analysis of organizational documentation relating to implementing New Direction in Staffing changes

- review of a representative sample of appointments and appointment processes from across the staffing system

- administration of a questionnaire to sub-delegated managers and staffing advisors from participating departments and agencies involved in the appointments and appointment processes examined

Sampling approach

The audit included the review of indeterminate and term appointments made during the audit scope period, and included external and internal appointments from both advertised and non-advertised appointment processes.

A total of 386 appointments were randomly selected from across 25 large, medium and small departments and agencies. The number of appointments reviewed depended on the size of the organization. For large departments and agencies, a total of up to 20 appointments; medium: between 2 and 7 appointments; small: up to 2 appointments.

Most large departments and agencies were selected because they make the vast majority of in-scope public service appointments, regardless of the fiscal year. Conversely, the sampling approach yielded no very small (“micro”) organizations, due to the low number of appointments they make in a given year.Annex A: Audit findings and supplementary exhibits

Implementation of the New Direction in Staffing in departments and agencies

What we expected

As per the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument, deputy heads are required to establish the following:

- direction, through policy, planning, or other means, on the use of advertised and non-advertised appointment processes

- requirements for sub-delegated persons to articulate their selection decision in writing

- an attestation form for sub-delegated persons that includes, at a minimum, the statements found in Annex C of the revised Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument

What we found

- All 25 departments and agencies had implemented the changes stemming from the New Direction in Staffing.

- In many cases, deputy heads had adapted these requirements to better reflect their organizational context.

Merit-based staffing

What we expected

The Public Service Employment Act requires that appointments to and within the public service be based on merit. Section 30 (2) of the act sets out the matters to be considered in determining merit, which include essential qualifications for the work to be performed and, if applicable, any asset qualifications, operational requirements and/or organizational needs identified by the deputy head.

As per the Public Service Commission’s Appointment Policy, deputy heads must ensure that information related to the appointment, such as the assessment and results of all candidates, is accessible electronically or through other means for a period of 5 years.

What we found

Compliance on merit was in excess of 95%, as follows:

- essential qualifications, including education and official languages proficiency: 96.9%

- asset qualifications, operational requirements and organizational needs: 95.9%

Exhibit

In one external advertised appointment process to fill a bilingual position responsible for providing training and for evaluating continuous learning programs, the person appointed was assessed for second language proficiency in English, which was in fact the person’s first official language. The person’s second official language was actually French, which had already been assessed in the past and for which the appointee had obtained levels below the linguistic requirements of the position. It was therefore determined that merit was not met.

Considering persons with a priority entitlement

What we expected

The Public Service Employment Act and the Public Service Employment Regulations provide an entitlement for certain persons who meet specific conditions to be appointed in priority to others. According to the Public Service Commission (the agency)’s Appointment Policy, deputy heads must assess persons with a priority entitlement and must respect requirements to administer priority entitlements as set out in the Priority Administration Directive, including obtaining priority clearance from the agency before proceeding with an appointment process or an appointment.

What we found

- A priority clearance was required for nearly all appointments audited (384). In 377 (98.2%) of these, a priority clearance was obtained from the agency before the appointment was made.

- Among appointments where persons with a priority entitlement were referred for consideration, in 97.6% of audited appointments, persons with a priority entitlement were assessed.

- In 56 audited appointments (14.7%), we found differences among the essential qualifications and/or conditions of employment identified in the request for priority clearance and those applied in the appointment process and decision, which may have prevented persons with a priority entitlement from being fairly considered.

- In more than half of these cases, differences were identified in the essential qualifications.

- In 21 audited appointments (5.5%), we found differences with respect to appointment tenure (full-time versus part-time and seasonal, geographic location, and occupational group and level) and/or the appointment process type (advertised versus non-advertised, and internal versus external), which may not have allowed the proper consideration of persons with a priority entitlement.

- These differences were equally distributed among appointment tenure and appointment process types.

Exhibits

- In one external non-advertised appointment process for a position responsible for analyzing and making recommendations related to harassment grievances and complaints, several knowledge qualifications related to laws, directives, programs and procedures with respect to harassment were used to consider persons with a priority entitlement, but were not applied to assess the person appointed. In this case, persons with a priority entitlement may have chosen not to self-refer to the process, given the specific knowledge qualifications.

- In an internal advertised appointment process for a senior analyst position in the policy branch of a line department, nearly all essential criteria used in the priority clearance request were different than those applied in the appointment. In this case, the hiring manager may have screened out persons with a priority entitlement from further consideration if they did not have this experience.

Official languages obligations

What we expected

According to the Public Service Commission’s Appointment Policy, deputy heads must respect official languages obligations throughout the appointment process, such as providing complete and accurate information concerning the appointment process in both official languages. This requirement also reinforces the commitment set out in the Official Languages Act to ensure that the Government of Canada provide English- and French-speaking Canadians with equal employment and advancement opportunities in federal institutions.

What we found

- Priority clearance requests: In the appointments audited where a priority clearance request was required and obtained, we found differences between the French and the English versions in 48 appointments (12.6%).

- Job advertisements: In the 237 advertised appointment processes audited, we found differences between the French and English versions of the advertisement in 45 instances (19%). Most of these differences were identified in the wording of the merit criteria for the position.

- Assessment tools: We found differences between the French and the English versions of the assessment tools for 26 appointment processes (15.2%). In addition, for 23 appointment processes (13.5%), the organization was unable to provide all the assessment tools necessary to complete our analysis.

Exhibits

- Priority clearance requests: In the priority clearance request for an external non-advertised appointment process to fill an entry-level position providing administrative support in human resources, the English version of an essential experience qualification indicated “Experience in providing administrative support services,” whereas the French version indicated “Expérience de la prestation de services de soutien en dotation administrative.” This difference in the priority clearance request could have had an impact on persons with a priority entitlement who were French-speaking and their eligibility and decision to apply, given that they had to possess administrative experience specifically in staffing.

- Assessment tools: In reference checks for an internal advertised appointment process to fill a position in the operational services occupational group, the English version included the following question: “Overall, please describe how the candidate demonstrates discretion,” whereas the French version of the reference check template included, “Veuillez décrire la façon dont la personne fait preuve d’initiative dans l’ensemble.”

- Assessment tools: In written reference checks for an external advertised appointment process to fill a position in the field of program administration, the French version of the reference check template included 3 categories of answers: “very good,” “good” and “poor,” whereas the English version included a fourth category, “not applicable.” This category was for candidates who did not have an opportunity to demonstrate this behaviour. The English version also instructed referees to provide a description for behaviours categorized as “poor” or “not applicable,” whereas the French version required this description for the “poor” category only. This difference could have had an impact on the outcome for candidates assessed with the French template of the reference check, as there was no option to indicate if the behaviour was “not applicable.”

Preference to veterans and Canadian citizens

What we expected

In accordance with Section 39 (1) of the Public Service Employment Act, in an advertised external appointment process, any of the following who meet the essential qualifications referred shall be appointed ahead of other candidates, in the following order: a person who is in receipt of a pension by reason of war service, a veteran or a survivor of a veteran, and a Canadian citizen, within the meaning of the Citizenship Act, in any case where a person who is not a Canadian citizen is also a candidate.

What we found

- The order of preference applied in 18 external advertised appointment processes for which, in addition to Canadian citizens, there were veterans, and/or non-Canadians who met the essential qualifications.

- Of these, the order of preference was respected in 13 appointment processes (61.9%) but was not respected in 5 appointment processes (23.8%), meaning that another qualified candidate was appointed ahead of an eligible veteran or Canadian citizen.

Attestation form

What we expected

As per the Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument, sub-delegated persons must have signed the attestation form prior to making the offer of appointment.

What we found

- In 92.3% of audited appointments, the person who made the offer of appointment had signed the attestation form prior to making the offer.

- In the remaining instances, the attestation form was signed by the sub-delegated person from between a few days to over a year following the time the offer of appointment was made.

Oath or solemn affirmation

What we expected

As per Section 54 of the Public Service Employment Act, the oath or solemn affirmation is a condition of appointment for appointments that are made from outside the public service. The oath or solemn affirmation states: “I,…, swear (or solemnly affirm) that I will faithfully and honestly fulfill the duties that devolve on me by reason of my employment in the public service of Canada and that I will not, without due authority, disclose or make known any matter that comes to my knowledge by reason of such employment.”

The effective date of appointment for a person being newly appointed to the public service is the later of either the date agreed to in writing by the sub-delegated manager and the appointee, or the date on which the appointee takes the oath or solemn affirmation.

What we found

- The requirement was met in most instances.

- In 20 appointments (9.7%), the oath or solemn affirmation was not taken on or before the date of the appointment identified in the offer of appointment. In many of these instances, however, the oath or solemn affirmation was taken within a few days of the appointment date.

Annex B: List of departments and agencies included in the System-Wide Staffing Audit

- Administrative Tribunals Support Services of Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Correctional Service Canada

- Courts Administration Service

- Department of Justice Canada

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Global Affairs Canada

- Health Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- National Defence

- Natural Resources Canada

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Service Commission of Canada

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Shared Services Canada

- Statistics Canada

- Transport Canada

- Veterans Affairs Canada