The Role of Regional Actors

Afghanistan’s neighbours support many different groups within that country, and justify their interference by their own geopolitical, economic or religious interests. Peace would bring down much of the war economy and disadvantage many who have grown rich from it. Nevertheless, neighbours support the peace process for its potential to end regional instability, and all but India want the US to leave without establishing a permanent regional presence. None want a precipitous US withdrawal, which would provoke a new civil war.

This chapter summarises the role of regional actors in the Afghan conflict, seeking to identify the most significant ways that major players around the war-torn zone become involved. Such an exercise will always be vulnerable to oversimplification, and experts will disagree about elements of the analysis, in part because many actors disagree about their roles. Still, there is a broad consensus that most of Afghanistan’s neighbours want to prevent the US from maintaining a long-term military foothold in their backyard. There also exists some level of regional agreement about the need to prevent the spread of instability. Disagreements are numerous and the neighbours are likely to continue supporting rival proxies. Still, some regional actors are also seeking to facilitate peace negotiations, in part to curb the escalating violence on their doorstep and secure a stake in an eventual political settlement.

A two-sided war

The war in Afghanistan involves many domestic and international parties, both state- and non-state. Not all of the details of these parties are equally relevant, however. The June 2018 ceasefire supported the idea of a simple, two-sided model of conflict: the Taliban fighting the US-backed government. Public declarations of a pause in hostilities from the Afghan government and the US military, followed by Taliban reciprocation, resulted in a cessation of violence for three days across most of Afghanistan’s territoryFootnote 3 . “It was a controlled experiment”, said President Ashraf Ghani. “It speaks about a discipline. You have an interlocutor [the Taliban] you need to take seriouslyFootnote 4 ”. The Taliban are primarily a domestic actor, and most insurgents fight near their own home. The Taliban also govern locally on issues such as education, healthcare, justice and taxationFootnote 5 . Among the thousands of battles waged each year, nearly all of them involve pro-government forces fighting the Taliban. Conflict between these two sides accounted for more than 95 per cent of violent incidents in Afghanistan, making other militant groups a negligible factor on the battlefieldFootnote 6 .

Many secondary parties

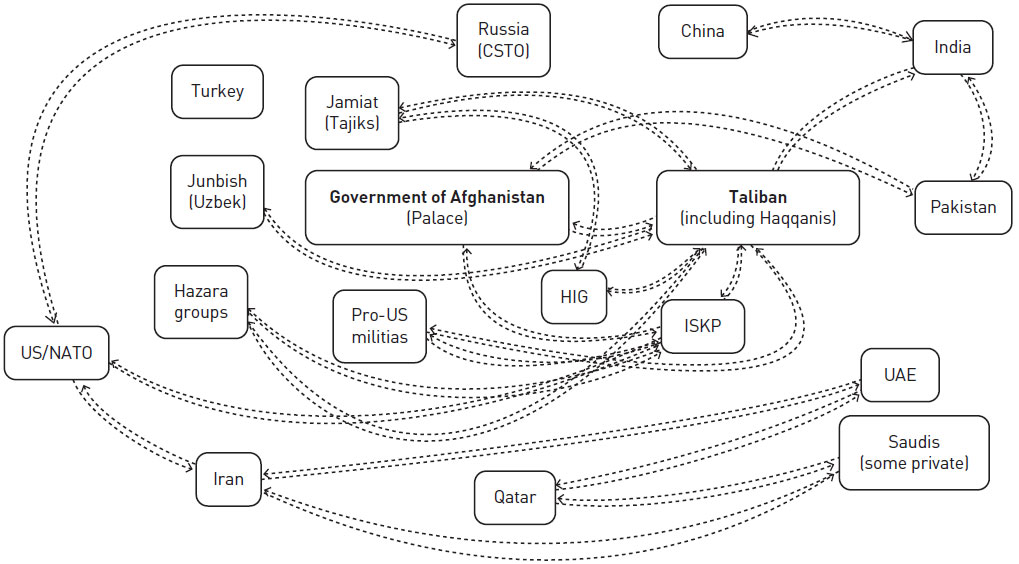

The role of secondary parties cannot be ignored. None of them individually have sufficient influence to control the war or dictate the terms of an eventual peace settlement, but their cumulative effect is substantial. Regional sources of support for the Taliban and other non-state actors have become clear in recent years with the growing scale of the insurgency and the increasing levels of direct assistance to the Taliban from nearby countries. Such assistance sometimes results from hedging strategies as regional powers seek local allies—Taliban, warlords, militia leaders—who can protect their interests within AfghanistanFootnote 7 . This results in some regional actors giving calibrated support to both sides of the conflict, and sometimes to competing factions within each. Figure 1 maps these overlapping lines of assistance, but should be considered illustrative and not exhaustive.

Figure 1 Long Description

At the centre of the image are two text boxes representing the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban. Several text boxes surround the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban which represent state and non-state actors within the region. Connecting arrows demonstrate the support given to each entity at the centre of the image. Turkey supports Jamiat (Tajik), the Government of Afghanistan and Junbish (Uzbek). Russia supports Jamiat (Tajik), the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban (including the Haqqanis). China supports the Government of Afghanistan and Pakistan. India supports the Government of Afghanistan. Pakistan supports the Taliban (including the Haqqanis) the HIG, and the ISKP. UAE supports Pakistan. The Saudis (with some private donors) support Pakistan, the ISKP and the HIG. Qatar supports the Taliban (including the Haqqanis) and Iran. The HIG supports the Government of Afghanistan. Iran supports the Taliban (including the Haqqanis), the Government of Afghanistan and Hazara Groups and finally, the US/NATO supports the Government of Afghanistan and Pro-US militias.

Starting at the right of Figure 1 and moving clockwise: Pakistan and India play out their rivalry through their Afghanistan policies, with Pakistan seeking to preserve its regional influence by supporting the Taliban. Pakistan also backs a variety of militant groups such as the Islamic State- Khorasan (IS-K) and, formerly, Hizb-e Islami Gulbuddin (HIG), to maintain asymmetric threats against India and the US-backed government in Afghanistan. India cultivates strong relations with the Afghan government to unsettle Pakistan, including through ties to anti-Pakistan politicians and elements of the Afghan security forces. Donors in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries serve as a fundraising base for the Taliban, but also support the Taliban’s rivals, the IS-K and HIG. Qatar serves as a diplomatic outpost for the Taliban, while supporting Iran’s policy in the region against its rivals in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia. Iran backs the Afghan government but also provides limited support to the Taliban, for example against the IS-K groups near the Iranian border. Iran also recruits from Hazara groups for Shiite militias operating in Syria and Iraq. Turkey safeguards the Turkic peoples of the north via strongmen such as Rashid Dostum of the Uzbek-dominated Junbish Party, and, to a lesser extent, through figures such as Atta Muhammad Noor of the Jamiat Party. Russia and other members of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) pursue a buffer strategy, supporting the Kabul-based government while building relationships with armed groups. Russia has also recently cultivated relations with the Taliban, seeking to embarrass the US and hasten the departure of its troops. China maintains warm relationships with both Afghanistan and Pakistan, while pursuing a narrow counter-terrorism effort against ethnic Uighurs with cooperation from many actors, including the TalibanFootnote 8 .

The United States and its allies

The actors on the left side of Figure 1, the US and its allies, have had the most important influence on the conflict since 2001. Western powers shaped the war from the original decision at the Bonn conference to include representatives from many armed factions, but exclude the TalibanFootnote 9 . The government that emerged from the Bonn process was dominated by leading figures who had fought the Taliban in previous decades. Some of the most prominent anti-Taliban figures were promoted to senior positions. Support for the Afghan government and security forces insulated the government from considerations about peace, and generated incentives to extend the conflictFootnote 10 . The US and its allies have also pursued a counter-terrorism campaign in Afghanistan since 2001, and maintaining this effort remains the primary US rationale for a continued military presenceFootnote 11 . The international community also pursues a normative agenda in Afghanistan, seeking to promote human rights—including women’s rights—and liberal democratic valuesFootnote 12 . This alienates actors inside and outside of Afghanistan who disagree with Western norms and provokes resistance among regional actors opposed to the US. Washington also continues to support militias independently from the Afghan forces, complicating further the political situationFootnote 13 .

Regional tensions

Another way of picturing the regional role would be to re-examine the actors listed in Figure 1 through a lens of conflict rather than support. Figure 2 seeks to portray the major lines of tension between the primary and secondary parties to the conflict. This diagram omits some patterns of conflict that are short-lived or remain latent: for example, the rivalries between Junbish, Jamiat, HIG and Hazara groups and the Presidential Palace, which may shift during the anticipated election season of 2019. No lines are drawn between Iran and HIG because it is now unclear whether the historical tensions between Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Tehran have been resolved; similarly between HIG and Russia. Arrows are depicted in both directions between Pakistan and Afghanistan, even though Islamabad claims that no hostilities exist between the two countries. In fact, skirmishing along the Durand Line and Pakistan’s sheltering of Taliban leaders indicate tensions.

Figure 2 Long Description

At the centre of the image are two text boxes representing the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban (including Haqqanis). Several text boxes surround the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban (including Haqqanis) which represent state and non-state actors within the region. Connecting arrows demonstrate the tensions which exist in and among each text box representing an entity. These entities are comprised of neighbouring and stakeholder countries which include: Qatar, Iran, UAE, Pakistan, India, China, Russia (CSTO), Turkey, Saudis (with some private) and US/NATO. The non-government entities include: Jamiat (Tajiks), Junbish (Uzbek), HIG, ISKP, Hazara Groups and Pro-US militias.

Business interests

The actors depicted in Figures 1 and 2 can be sub-divided into factions, with the most notable cross-cutting issue being the war economy. Senior figures on all sides have profited handsomely from the war: among government officials, political opposition groups, the Taliban, regional governments and regional security forces. The war economy provides incentives for maintaining the status quo, or minor jockeying to improve commercial standing, and disincentives for major changes such as a peace agreement. In May 2016, when a drone strike killed then-Taliban leader Akhtar Mansur in Pakistan, feuds emerged among senior insurgents about the USD 900 million that reportedly went missing from his bank accounts. On the opposite side of the war, some well-known figures among the Afghan elite are reportedly billionaires. Such fortunes often reflect involvement with Afghanistan’s opium industry, which has grown significantly since 2001 and now dominates the world marketFootnote 14 . Opium thrives in zones of lawlessness, along with other illicit businesses such as the weapons trade, timber smuggling and illegal miningFootnote 15 . Legal businesses associated with the conflict also represent the largest non-agricultural employer, either directly with security forces or indirectly with trucking, logistics, construction, fuel supply, private security and other industriesFootnote 16 . This poses a challenge to any future peace process: successful peace negotiations may shrink the war economy, endangering livelihoods.

Conclusion

The overriding suspicion in the region has been that the US wants permanent military bases in South Asia. A lingering US troop presence of the kind in South Korea is unacceptable to Iran, Pakistan, Russia and China. India on the other hand seeks a long-term US commitment. That makes the news of a potential US drawdown reason for cautious optimism among most major regional actors. The neighbours may be less inclined to disrupt US policy if they believe that Washington will eventually give up its strategic foothold on their doorstep. But just because the neighbours want a US exit does not mean they seek an abrupt withdrawal. All sides recognise that a precipitous pull-out could spark a new civil war that would destabilise the region. The neighbours do not enjoy surprises, and uncertain signals from the White House cause anxiety.

To some extent, this anxiety could provoke constructive thinking. Regional powers with a stake in Afghanistan now face hard decisions about how to shape the post-US future. They could assist with peace talks to calm their neighbourhood. They could reinforce their backing of Afghan proxies that fuel civil war or, more likely, they could pursue both tracks. Public statements from regional diplomats will not reveal much about their plans; a better indicator would be the flow of weapons and support for proxy forces. Hopeful signals emerged in 2018 as the regional powers positioned themselves as facilitators of peace talks, sometimes in cooperation with the US. It remains to be seen whether these diplomatic interventions will prove constructive in 2019. Regional policy on Afghanistan stands at a crossroads.