Chapter 8 - Offline propaganda by ISIL

In addition to issuing online propaganda designed to recruit foreign fighters and encourage jihadist attacks abroad, ISIL has a sophisticated offline communications capability designed to achieve total information control within its territory. To ensure absolute communications domination, access to the Internet is being removed, outside radio signals are jammed and satellite dishes are banned. The population is given a picture of an idealised, benevolent but also vengeful caliphate. The propaganda subjugation of the population may make it impossible to completely destroy ISIL. Those within its territory will have an alternate view of reality which has its only modern parallel in North Korea.

Since the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) seized control of Mosul in the summer of 2014, the group has persistently been at the forefront of mainstream media, commanding headline news and driving the international security agenda. Abu Bakr al‑Baghdadi's iteration of the Islamic caliphate poses a unique security threat to its varied adversaries. In the space of five years, it has attracted tens of thousands of supporters to join its ranks from as many as 86 statesFootnote 65 . Beyond that, it has been able to inspire “self‑starter” terrorist attacks far more effectively than Al-Qaeda ever didFootnote 66 . ISIL’s propaganda machine has played a critical role in generating and sustaining its ability to project power. Indeed, propaganda is an essential pillar of its overarching strategyFootnote 67 . While audiovisual media alone does not cause radicalisation or recruitment, it is an important catalyst to the process as a way to reinforce the beliefs of sympathisers, to provide “evidence” for the claims made by its recruiters, and to inspire global—sometimes violent—activism in its nameFootnote 68 .

Meaningfully countering ISIL’s political messaging has long been a central objective of the international coalition that was formed to destroy the group in 2014Footnote 69 . Indeed, the topic of propaganda has featured in most key speeches made by Western leaders about the group since late summer 2014, when Mohammed Emwazi's string of beheading videos beganFootnote 70 . However, while there is no denying that the group’s media efforts require a response, the focus on the phenomenon as it appears online has served as something of a red herring. Coalition governments have been overly preoccupied with how ISIL propaganda’s Internet presence endangers their national security, in comparison to how it is being applied offlinein the so‑called caliphate itself.

Indeed, rarely is it recognised that the thousands of photo reports, videos, audio messages, magazines and anashid (religious songs) that the group’s official media offices produce are not intended merely for Internet consumption abroad. Rather, this content is aimed at a domestic audience—the people over whom ISIL rules. In a manner that is typical of totalitarian regimes, as pointed out by political scientists Carl Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski, communications are being used as a mechanism to consolidate the group’s existence, exert political control and preserve its longevityFootnote 71 . While its offline application may pose a less immediate menace than the threat of foreign fighters and self-starters, this aspect of its propaganda is being ignored at the peril of the coalition. Unless it is recognised and mitigated, it may become impossible to truly degrade and destroy ISIL insurgency.

The infrastructure

For political messaging to enjoy maximum success, a state or proto-state must exert full control—or something close to it—over mass mediaFootnote 72 . In the digital communications age, there are few places on Earth where such complete control is possible, as it necessitates the rare ability to limit all other channels of information. The Democratic Republic of North Korea is one such example; ISIL’s heartlands in Syria and Iraq are anotherFootnote 73 .

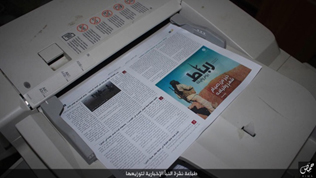

For years, ISIL has proactively wrested control over the information space in the territories it controls. When it enjoys full control of an area, one of its first actions after solidifying its provision of governance and judicial structures and bedecking the streets with its flag, is to establish nuqat i'lamiyya (literally, ‘media points’)Footnote 74 . These makeshift propaganda offices are often nothing more than shipping containers or mobile homes equipped with projectors, printers and plastic chairs [Figures 1‑2]Footnote 75 . Sometimes, they are mobile [Figure 3]Footnote 76 . As well as serving as open-air cinemas for any of ISIL’s 40 official video‑producing media outlets, these points are satellite publishing houses for its written propagandaFootnote 77 . Each week, for example, ISIL’s 16-page news publication, al-Naba’, is electronically disseminated across the 39 provinces of the caliphateFootnote 78 . At media points, it is downloaded and printed before supporters embark on their weekly newspaper round, which falls on a Saturday [Figures 4‑6]Footnote 79 . Media points are also the places in which the group’s electronic magazine, al-Maysara, is burned onto compact disks, and al-Himma Library dawa materials are printed and bound [Figures 7‑8]Footnote 80 .

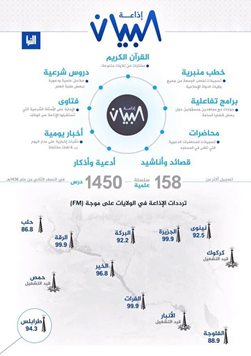

ISIL’s information infrastructure extends to the airwaves, too. Its official daily bulletins, which are broadcast over social media in five languages, are more than online phenomenaFootnote 81 . They are disseminated in analogue format throughout the ‘caliphate’, alongside 'on-the-air fatawa', revisionist history programs on 'the kafir Baath Party', and call-in medical clinics—all of which are aired daily by al-Bayan Radio, ISIL’s own FM station which operates from Tripoli Province in Libya to Nineveh Province in Iraq [Figures 9‑10]Footnote 82 .

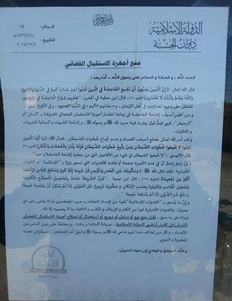

Substantial as it may be, the actual efficacy of this infrastructure would be far less consequential were it not for the group’s stranglehold on the free passage of outside information into its borders. If ISIL is to sustain its totalitarian state-building project, outside channels of media that run against the party line pose a long-term destabilising threat. Recognising this, the group has worked to remove free access to the Internet, jam FM radio signals and ban satellite dishes, which it refers to as 'adu min al-dakhil (an enemy within) in official publications [Figures 11-12]Footnote 83 . Everywhere in the ‘caliphate’ heartlands, public access Internet cafes must now be monitored and licensed by the group's Public Security OfficeFootnote 84 . In several provinces, private access has been entirely banned, regardless of whether it is for local soldiers, foreign fighters or civilians; in others, it is in the process of being shut down Footnote 85 .

The sum of all this is a situation in which news that runs contrary to ISIL’s rigorously dictated line is hard to come by for those living under it. Whether one is in Iraq or Syria, credible reports about the global coalition’s efforts is scarce indeed, and the few tidbits that do get through become instantaneously obscured by the overwhelming quantity of ISIL-produced disinformation. Conspiracy theories run amok and confusion as to the coalition's real aims is rife, such that the caliphal narrative is the only constant.

The message

As previous research empirically demonstrates, the body of official ISIL propaganda circulated online is more complex than mainstream media coverage would suggestFootnote 86 . Far more prominent than the instances of ultraviolence for which Islamic State is infamous are representations of the utopian caliphate “state”, be they photos of wildlife and waterfalls or videos showing street cleaners and maternity wards.Footnote 87

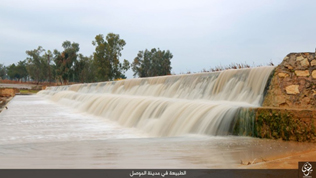

The same can be said of the propaganda that is circulated in the real world—ISIL brands itself offline as the benevolent, as well as vengeful, ‘caliphate’. The 25 photo essays and three video features it publishes each day are designed to distract from reality and generate a rally-around-the-flag effectFootnote 88 . On a given day, civilians in any one part of Islamic State’s territories may be force-fed images of waterfalls in Nineveh Province, vegetable agriculture in Salahuddin Province, electricity engineers in Barakah Province and military advances in Damascus Province—and that is not to mention content emerging from ISIL’s overseas provinces [Figures 13-16]Footnote 89 . Images of bustling markets in Libya, cannabis plants being burned in Afghanistan, religious sermons in Nigeria and ambushesin Egypt are equally ubiquitousFootnote 90 . There is a constant, unrelenting stream of high-definition "evidence" of divinely-driven statecraft and military momentum. Furthermore, its utopian expansionism aside, the group’s adversaries are bundled—and condemned—together, regardless of whether they are allies or enemies, as dead children and old people are paraded before the propagandists' camerasFootnote 91 .

Conspiracy theories run amok and confusion as to the coalition's real aims is rife, such that the caliphal narrative is the only constant.

Morale is buoyed among supporters, and despair entrenched for potential dissenters: civilian sympathisers are able to distract themselves from the iniquities of ISIL rule by looking on at the seemingly stable, fruitful lives of their brethren elsewhere; soldiers losing ground on one front can find inspiration from victories allegedly won hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles away; and potential dissenters are deterred as the perception of generalised risk is compounded by gruesome films in which like-minded individuals are burned, drowned or dismembered to deathFootnote 92 .

Conclusion

In ISIL’s heartlands, propaganda is total. It stretches from the morning news to lunchtime listening and evening recreation. Ultraviolence is routinised, juxtaposed with visceral scenes of beauty and vivid, euphoric depictions of prayer. Crucially, and in stark contrast to when it is disseminated online, its offline delivery is mono-directional and, as things stand, uncontestable. As such, its offline consumers are subjected to what Paul Kecskemeti, writing in 1950 about Nazi and Soviet propaganda, termed the "suggestive effect"—as a substitute for certainty, the official, ubiquitous ISIL narrative "is the only thing that can be acceptedFootnote 93 ". Kecskemeti continues: "every part of [this narrative] is designed to enhance respect for the totalitarian government, to generate approval of its policies, and to silence doubts as to the power, benevolence, wisdom, and cohesion of the ruling cliqueFootnote 94 ".

As part of an exacting, rigorously designed communications strategy, ISIL is doing more than projecting its power. Through its voluminous media output and efforts to secure a monopoly on information, the organisation is systematically working to consolidate political power in its territorial heartlands, curtail the possibility of local dissent and entrench a conspiratorial, jihadist understanding of the world. The global anti-ISIL coalition has been active in challenging the group’s propaganda. Questions of efficacy aside, however, the parameters for success in its information war are, at present, exclusively focused on countering the group’s online influence. Tactics are thus devised based on their ability to undermine the organisation’s recruitment of new members and inspiration of attacks in its name. This is to the detriment of the coalition's strategic goal of eliminating the group, as it has served to distract from this less obvious—but more insidious—offline application of ISIL media.

Figure 1: "Establishing a media point in Zawba'a", Janub Province Media Office, 29 October 2015.

Figure 2: "Opening a media point in the city of Sirte", Tripoli Province Media Office, 31 August 2015.

Figure 3: "A mobile media point's tour in the eastern sector", Khayr Province Media Office, 9 September 2015.

Figure 4: "Distributing al-Naba' magazine in the Samarra' Peninsula to ordinary Muslims, Salahuddin Province Media Office, 26 November 2015.

Figure 5: "Distributing al-Naba' and da'wa books and pamphlets to soldiers of the caliphate", Diyala Province Media Office, 3 December 2015.

Figure 6: "Printing and distributing the al-Naba' news publication", Homs Province Media Office, 24 December 2015.

Figure 7: "Burning and distributing al-Maysara electronic magazine to ordinary Muslims in the eastern region", Khayr Province Media Office, 28 August 2015.

Figure 8: "Opening a media point in the city of Sabikhan", Khayr Province Media Office, 26 July 2015.

Figure 9: "Wait, we are also waiting", al-Naba' XI, 29 December 2015, 16.

Figure 10: "al-Bayan Radio Infographic", al-Naba', 29 November 2015.

Figure 11: "The banning of satellite receivers", Department of Hisba, 2 December 2015.

Figure 12: " al-Bayan Radio Infographic", al-Naba', 29 November 2015.

Figure 13: "Nature in the city of Mosul", Nineveh Province Media Office, 21 January 2016.

Figure 14: "One of the onion producers in the province", Salahuddin Province Media Office, 21 anuary 2016.

Figure 15: "Aspect of the work of the Services Department: repairing powerlines in the city of al-Shadadi", Barakah Province Media Office, 21 January 2016.

Figure 16: "Targeting the positions of the Nusayri army in the environs of Liwaa' 128 in eastern al-Qalamun", Damascus Province Media Office, 21 January 2016.