Chapter 11 - Towards free-market reforms in Iran?

Since his election in July 2013, President Hassan Rouhani has stressed his commitment to implementing free-market reforms that would liberalise Iran’s economy. This ambition has been expressed through numerous statements about his intention to develop the private sector, reduce the regulatory burden and the size of government, put an end to public monopolies and promote competition, and attract foreign investment. Iranian authorities have also shown a clear interest in reopening talks to join the World Trade Organization (WTO). It was difficult for authorities to implement this policy before the sanctions related to the nuclear program were lifted. Now that the deal is officially in place and the sanctions are gradually beginning to be lifted, Iranian authorities are expected to focus on these objectives.

It is worth noting that the economy is a major political issue for Rouhani. Iran’s economy is still in crisis. Growth was virtually nil in 2015. With the end of international sanctions, economic growth should reach 4 to 5 per cent this year, but this result may be short-lived. The reforms are intended to place Iran’s economy on the path to high annual growth of 8 per cent. Only strong, steady growth will enable Iran to reduce its unemployment rate, which currently hovers around 18 per cent, with young graduates making up a large proportion of the jobless. Furthermore, in an economy heavily dominated (80 per cent) by the public sector, only the private sector will be able to create the necessary jobs and develop non-oil-related exports. The ultimate goal of these reforms is to reinforce Iran’s clout in the region and on the international stage by positioning Iran as a new emerging economy. This will be a tremendous challenge, since past results in terms of growth have been disappointing in comparison with those of other emerging economies. The purpose of this note is to assess whether this program of economic openness will actually be implemented. First, a list of facilitating-factors conducive to the implementation of this program, will be presented. Barriers to implementation will then be examined.

Facilitating factors of economic openness

Shifting attitudes

The factor that is most favourable to the planned free-market reforms is undoubtedly the fact that, in a way, Iranian society is ready for the change. There is no need to revisit the sustained modernisation trend in Iranian civil society since the Islamic Revolution (Table 1). However, it is worth highlighting a few factors related to the opening up Iran’s economy. A number of sources have noted the rise of individualism and a growing acceptance of the concept of competition in Iranian society, a trend that should naturally favour a program of economic opennessFootnote 23. Furthermore, a survey conducted in the private sector has confirmed the modernity of the Iranian middle class, which cherishes such values as competency, competition, equality between men and women, and power-sharing between parents and children in family businesses. Certain politicians have also been affected by these shifting attitudes. Many key figures now acknowledge that the nationalisations that occurred shortly after the Revolution were a mistake. There is also a certain degree of political consensus on the need to reduce the size of government (to fight corruption), foster private sector developmentFootnote 24, and counter the rentier nature of the economy and its dependence on oil.

| Esfahan | 48.5 |

| Tehran | 45.9 |

| Khorasan-Razavi | 47.6 |

| Kerman | 49.2 |

| Sistan & Baluchistan | 46.8 |

| Kordestan | 49.1 |

| Khuzestan | 51.4 |

source: Statistical Centre of Iran

Existence of a non-oil-related industrial base

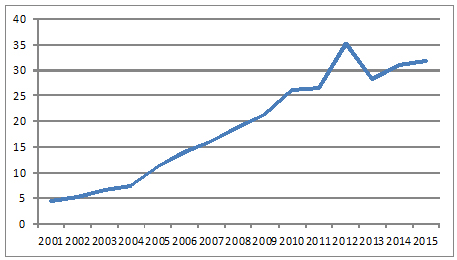

Iran is not merely an oil-based economy; it also has an industrial base and a genuine private sector (which controls close to 20 per cent of the economy). A revealing figure is the surge in non-oil-related exports over the past few years (Figure 1). In 2014, non-oil-related exports accounted for close to 35 per cent of Iran’s total exports, in contrast to 10 per cent in Saudi Arabia. In addition, Iran’s main clients are now located in the surrounding region or in Asia (Table 2). The growth in Iran’s exports to Asia is undoubtedly due to the sanctions, because it was easier to secure payment from clients in that region. During the sanctions, Iranian businesses realised that the most accessible markets (similar culture, competitiveness of Iranian products) were those in the immediate region. Furthermore, many of Iran’s private-sector businesses are headed by true entrepreneurs, who have drive and resilience. This is not to say that Iran has no rentier entrepreneurs. Rent seekers are inevitable in a country where the state plays a dominant role and where it is sometimes difficult to distinguish good relations with the state from clientelism. At the same time, however, a widespread attitude has emerged in the private sector (and even across society at large) that distinguishes the genuine entrepreneurs from the rosulati, businesses that appear to be private but actually belong to the public or parapublic sector.

Figure 1 – Non-oil-related exports (billions of USD)

Source: IMF

China |

21 |

Iraq |

18 |

UAE |

16 |

Afghanistan |

8 |

India |

8 |

Turkey |

4 |

Italy |

3 |

Pakistan |

2 |

Turkmenistan |

2 |

Egypt |

1 |

Other |

17 |

Source: Iran Customs

Parliamentary support

Another facilitating factor is the fact that Iran’s parliament is likely to support free-market reforms. Following recent elections, “moderates” control a relative majority in parliament (close to 40 per cent of elected members). A number of the conservative members, who may be considered pragmatists, are also expected to support free-market reforms. The election of conservative Ali Larijani as Speaker of Parliament thanks to support from the moderate faction bears out this assessment. Larijani’s proximity to the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, could also lessen the Guardian Council’s opposition to legislation promoting economic openness.

Challenges to be overcome

Private sector distrust of the Iranian state

The government will have to overcome many challenges in order to implement the planned reforms. The first challenge concerns the need to regain the trust of Iran’s private sector. Although the private sector is generally favourable to the Rouhani government, a fundamental distrust of the state lingers. The private sector was traumatised by the nationalisations imposed after the 1979 Revolution. Furthermore, Iranians in the private sector often say that the rules of the economic game are rigged in favour of those close to the regime. Many entrepreneurs have no faith in the impartiality the justice or banking system. This distrust explains why private-sector businesses are often family-run (“God has no partners”) and small (to avoid drawing attention). It is clear that no development will occur in the private sector until its trust in the Iranian state and in public institutions is rebuilt.

Reluctance of foreign investors

It is clear that there is also distrust among foreign investors. This is a problem because attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) is vital to the success of the economic reforms in Iran. Rouhani hopes to secure USD 50 billion of FDI per year in order to meet the 8 per cent growth target. Furthermore, it is difficult to see how Iranian authorities will be able to open up their economy to foreign competition without benefiting from strengthening the competitiveness of their economy through technology transfers related to foreign investment (eg, in the automotive sector). In addition, giving foreign investors a larger role could foster the development (and trust) of the private sectorFootnote 26. Iran has a long way to go, since annual FDI flows in recent years have been in the range of only USD 3 billion. Many major international groups are now convinced of the potential of the Iranian market. The main issue that continues to trouble them is the sanctions. Some businesses are worried about entering into partnerships with companies connected to the Pasdaran or to other groups that are still under US sanctions, particularly in the energy and telecommunications sectors. The major oil companies are waiting for the legal environment surrounding oil contracts to become clearer, and these multinationals often have to deal with banks, particularly in Europe, that still balk at working with Iran for various reasons: consternation at the penalty levied against BNP Paribas; inability to work in US dollars with Iran; fear of falling under US sanctions. Overall, these major groups are expected to gradually undertake some FDI in the energy and automotive sectors, for example. However, FDI flows of USD 50 billion per year seem unlikely to materialise until foreign investors can be persuaded that Iran’s foreign policy is being “normalised”, particularly with regard to Iran–US relations. Major breakthroughs in this area are certainly not to be expected while Iran’s ultra‑conservative faction continues to treat such a rapprochement as a line in the sand. The recent US Supreme Court decision to seize USD 2 billion of Iranian assets may also limit opportunities for economic rapprochement between these two nations, at least in the short term. The creation of a more appealing business environment would, of course, help Iran attract more foreign investorsFootnote 27. In any event, the government seems to be partially staking its credibility, particularly domestically, on its ability to attract foreign investment, which in Iran is often seen as a logical consequence of the nuclear deal. The Iranian government may also harden politically if it feels that the US economic sanctions pose too much of an obstacle to foreign investmentFootnote 28.

Need to “normalise” foreign policy

A “normalisation” of Iran’s foreign policy could also play a positive role in these reforms if Iran succeeds in alleviating regional tensions by political means. More specifically, stronger ties with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arab monarchies could enable Iran to increase its non-oil-related exports to those markets. Recent years have shown that Iran’s “natural” markets are in the region (Table 2). Strengthening ties with India could also lead to increased trade and exports with that countryFootnote 29. Greater stability in Iran’s regional environment could help Iran become a regional trade centre, potentially leading to a significant increase in revenues from re-exports or transit trade.

Managing the social cost of economic openness

Another challenge for the government, particularly in the short term, will be to manage the social cost of free-market reforms. Unemployment in Iran currently hovers around 18 per cent and affects many young graduatesFootnote 30. Moreover, the most deprived social classes have become even poorer, and some official estimates suggest that close to one third of the population lives in poverty or borderline poverty. In this context, the privatisation of state-owned corporations, which would increase unemployment, could be a political minefield for authorities. Job creation opportunities would have to offset the jobs lost. It would therefore be preferable to wait until growth resumes before initiating privatisation efforts.

Managing political opposition to economic openness

The potential social cost of free-market reforms leads us to the subject of political opposition to this policy. The hardliners, which is against the nuclear deal, is clearly committed to total opposition to Rouhani’s policies and criticises them using any and all means. They faction sometimes asserts that this “neoliberalism” runs counter to the policies of the resistance economy because it favours imports, neglects national production, and grants too many benefits to foreign corporationsFootnote 31. At other times, the economic reforms are described as imposing a Western lifestyle on Iran. Ultra‑conservatives do not want economic openness to include normalising economic ties with the United States. In addition, strong criticisms have been voiced by groups further to the left of the political spectrum, who believe that the members of Rouhani’s government are above all businesspeople and exploiting their proximity to power for their own personal gainFootnote 32. This opposition could be surmounted, particularly if the desired economic results materialise. Larijani (the new Speaker of Parliament) and “pragmatic” conservatives could play a decisive role in helping Rouhani overcome opposition.

Opposition is also expected from the Pasdaran and bonyads (foundations), which have formed major economic groups by exploiting the fuzzy boundary between Iran’s public and private sectors. These groups may oppose the development of foreign investment if it goes against their interests. The Pasdaran in particular resent the return of foreign investors, especially in the energy sector, because their construction company, Khatam, secured many oil field development contracts after the international oil companies were forced out by the sanctions. The economic activities of the Pasdaran and bonyads limit private sector development because of the unfair competition they present. These groups can take advantage of privatisation to buy back state-owned corporations, as they have done in the past. They can also incite the most radical political figures, with whom they are close, to oppose the government’s economic reformsFootnote 33. In any event, the struggle for influence between the government and the Pasdaran has already begun. Certain developments suggest that the government is attempting to curtail the activities of the Pasdaran, particularly in the energy sector. However, the pragmatism of these groups should not be underestimated, as they are equally capable of adapting to a more open economic environmentFootnote 34.

Lastly, internal opposition within the state bureaucracy itself, particularly to a policy of privatisation, must not be overlooked. The Iranian press has reported resistance to privatisation among a number of ministers and senior officials. Some feel that there is a gap between the arguments for privatisation advanced by Rouhani and his cabinet leader, Mohammad Nahavandian, and the actual measures taken within the ministries, which may be refusing to cede their political power to the private sector. With that in mind, it is worth noting that SHASTA, the pension fund of the Social Security Organisation, is among the largest holdings in IranFootnote 35.

In conclusion, the policy of economic openness promised by President Rouhani will have many obstacles to overcome. The modernisation of Iranian society is a decisive factor that should gradually lead to the opening up of the economy. That factor is undoubtedly a strength for Iran, giving it a comparative advantage in its regional competition with Saudi Arabia. Moreover, compromises on free-market reforms may be reached between the various political factions. The political ramifications of economic openness are clear. A more powerful private sector would palpably change the relationships between the various political forces in Iran. The magnitude of this change will largely hinge on the ability of the private sector to operate autonomously from the state and on how much private-sector autonomy the dominant political forces are willing to tolerateFootnote 36.