Beyond Hate: Vigilantism and the Modern Far Right

Right-wing democratic radicals and authoritarian extremists can be further subdivided into overlapping categories that share the belief that a country belongs to its traditional inhabitants, and not foreigners. The motivations and intensity of the exclusionary agendas ranges from firm to violent. This agenda can be advanced if immigrants are successfully portrayed as criminals and the authorities as negligent. It is hindered if immigrants are accepted as unthreatening, and authorities are trusted and firmly reject vigilante violence.

The Far-Right Landscape

A discussion of the far right requires a modern conceptual clarification of what is meant by such terms as far right, radical right or extreme right. Although they are often used interchangeably, these terms should be applied in a more precise way. The terms left and right, stemming from the French revolution, continue to represent their original meanings: leftists generally support policies designed to reduce social inequality, whereas rightists regard social inequality—and corresponding social hierarchies—as inevitable, natural or even desirable. One can also distinguish between radical and extreme versions of both the far left and far right, where the radical movements work for change within the framework of democracy whereas the extremists reject democracy and are willing to use violence to achieve their goals.

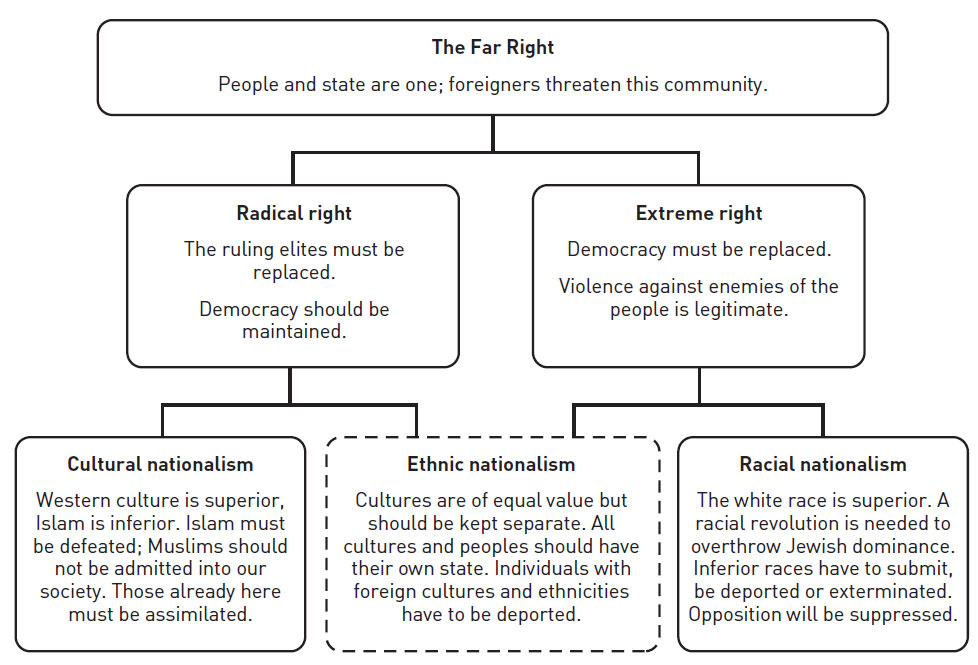

An attempt to construct a ‘family tree’ of the far right would yield the following modern representationFootnote 1 :

Figure 1 Long Description

This figure describes the groups and subgroups that compose the modern Far Right, an overarching term that describes those who feel that the people and state is one, and that foreigners threaten this community. The far right is composed of two primary groups: the radical right and the extreme right. The radical right feels that the ruling elites must be replaced, but that democracy should be maintained. The extreme right feels that democracy must be replaced, and that violence against enemies of the people is legitimate. The radical and extreme right can be further broken down into three subgroups: cultural nationalism, ethnic nationalism, and racial nationalism. These are described in more detail in the text that follows.

The lower level of this family tree illustrates, in the present political context, the three main ‘families’ of far right movements: cultural nationalists, racial nationalists and ethno-nationalists.

Cultural nationalists

Typically represented by right-wing populist parties and movements against immigration and Islam, these parties and movements generally operate within a democratic framework and do not promote violence, although they may differ in their respective degree of radicalism. These movements are usually not preoccupied with racial differences but focus on cultural ones, claiming that Islam is incompatible with Western culture and society. However, they may accept that individuals of a different ethnic and cultural origin may be assimilated into their culture and become one of them. In recent years, some of these movements have embraced liberal values such as women’s liberation and gay rights—values they claim are threatened by Islam’s ‘invasion’ of Europe and North America.

Racial nationalists

On the other extreme, these groups are fighting for a society based on racial and totalitarian principles, like National Socialism, fascism, Christian Identity or varieties of white supremacy. Their world-view is typically based on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, claiming that the Jews promote racial mixing to destroy the white race. These movements oppose democracy and notions of universal human rights and consider violence necessary and legitimate to achieve their goals. They expect that a racial war will eventually come, and that ‘racial traitors’ and people of the wrong race will be exterminated, or at least expelled.

Ethno-nationalists

Between these two extremes, ethno-nationalists are exemplified by the Identitarian movement in Europe and the Alt-Right movement in the US. The European versions in particular prefer to avoid the term ‘race’ and speak instead about ‘ethnic identity’. They claim that all ethnicities are of equal value but should be kept separate in order to maintain their valuable characteristics (ethnic pluralism). Cultural mixing and assimilation is considered to be harmful. In contrast to many cultural nationalists, Identitarians tend to distance themselves from some core liberal values like gender equality and gay rights, instead promoting conservative views on gender roles. The Alt-Right movement may be considered as the US version of ethno-nationalism. They are less hesitant to talk about race, often presenting themselves as ‘white nationalists’. In their rhetoric, alt-right proponents often try to present themselves as a mirror image of the Citizens’ Right movement, talking about white rights rather than black rights. Ethno-nationalist groups generally distance themselves from the use of violence (although some activists do not), but these movements’ views clash with basic values on human rights, equality and democracy to the extent that they border on extremism. Other varieties present themselves in such moderate terms that they are closer to right-wing populists or cultural nationalists.

The distinctions between these three main types of right-wing movements are not sharp. Although a specific group or organisation may be placed within one of these categories, there might be wings or individuals that lean towards one of the other types. There may also be links and collaboration between groups and activists from different ideological camps.

Vigilantism Against Migrants and Minorities

While the popular understanding of vigilantism is ‘to take the law into one’s own hands’, the term refers to organised civilians acting in a policing role without any legal authorisation, using or displaying a capacity for violence, and/or claiming that the police (or other security agencies) are either unable or unwilling to handle a perceived criminal problemFootnote 2 . This is a phenomenon closely associated with the far right, and activists from all three ideological camps described above can be involved in vigilante activities in an effort to re-establish a certain social or moral order they claim is threatened by minorities and migrants. Four types of contemporary vigilante activities have been identified: vigilante terrorism, pogroms and lynching; paramilitary militia movements; border patrols; and street patrols.

Vigilante terrorism, pogroms and lynching

The classic case of vigilante terrorism is the Ku Klux Klan lynching of blacks and other minorities, usually accused of having committed crimes or breaking the ‘moral order’ of white supremacy. Similar processes took place in Russia, with a murderous campaign against migrants and homosexuals from 2006 to 2010, during which time vigilante terrorism and violence continued as the police ignored the (mostly) skinhead gangs that killed hundreds and injured thousands. Another extreme case of vigilante terrorism was the murder of Roma people in Hungary in 2008 and 2009. A killer commando of four perpetrators killed 10 people (including a child) and wounded six more when they attacked Roma villages with guns. They justified their actions by claiming that they intended to take revenge for ‘Gypsy crimes’ and provoke violent reactions from the Roma to trigger an ethnic civil war. In reality, the victims were selected randomly and had no particular relation to ‘Gypsy crime’.

Paramilitary militia movements

What distinguishes these militias from other forms of vigilante groups is that they are modelled on a military style and form of organisation. They usually wear military-like uniforms, perform parades and marches, and have a structured chain of command and training in military skills and/or firearms. In Central and Eastern Europe, there are long traditions of paramilitary militias, often affiliated with parties on the extreme right. In recent years, the most significant initiative was the establishment of the Hungarian Guard in 2007, as a militia wing of the right-wing extremist Jobbik party. The Hungarian Guard was tasked with protecting Hungarian citizens against ‘Gypsy crime’, sometimes marching through Roma villages and neighbourhoods to intimidate the inhabitants. Although banned the year after its establishment, it inspired similar movements in other Central and Eastern European countries, such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland.

In the US, there are also long historical traditions of vigilantism as well as citizen militias. For example, anti-government militias prepared to resist or even fight against alleged repression from the federal government (often identified as the Zionist Occupation Government, or ZOG), and the Minutemen patrolled the US-Mexican border. Although participants—mostly military veterans—tend to share far-right views, they see their mission as helping the government patrol the border in order to stop illegal migrants from entering the US.

Border patrols

Times of heavy refugee influx or of undocumented migrants crossing national borders (coupled with extensive political or media coverage) have frequently seen an elevated vigilante response. Claiming that the governmental border agencies are unable to fulfill their tasks of controlling the borders due to lack of capacity or determination, some activists have volunteered to ‘help’ in protecting the borders. In Bulgaria, vigilante border patrols affiliated with far-right political parties have patrolled the border to Turkey and even arrested undocumented migrants. A rather sophisticated attempt to demonstrate the capability to control sea borders against migrants in the Mediterranean is connected with the Identitarian group Defend Europe attempting to crowd-fund a ship. While the sea patrols did not achieve their official goals, they won huge media attention and popularised the Identitarian movement amongst a sector of the European public with anti-immigrant attitudes. The Storm Alliance in Canada has also conducted media stunts on the US-Canada border, although is not engaged in any serious patrolling of the border.

A common feature of all these vigilante border patrols is that they rarely or never detect or apprehend any undocumented migrants crossing the borders (with the exception of the Bulgarian case). Their activities appear to be completely symbolic, demonstrating the willingness of vigilantes to protect their ‘own country’ in the face of increased migration flows. Their efforts amount to a media strategy to affect the public support for ideas which vigilantes represent, including undermining the legitimacy of the political regime.

Street patrols

The most common type of vigilante activities against migrants and minorities, street patrols are composed of organised groups who walk together in the streets or near particular places with the stated goal of providing protection against people who might constitute a ‘criminal risk’, typically migrants and Roma people. Claiming that their presence will deter criminals and provide a sense of safety to the good and vulnerable citizens (and to women in particular), such patrolling activities typically start in the aftermath of criminal events which cause fear and anger in the community, especially when migrants or minorities have been involved as (alleged) perpetrators. Sometimes radical right organisations seize the opportunity to organise vigilante patrols to promote their group under the auspices of providing safety to the community.

Alternatively, such patrols may be organised spontaneously by concerned (or angry) citizens without any particular political sponsorship. Some of these groups maintain that they will only observe and report incidences to the police whereas other groups take a more active stance by intending to deter and even intervene against acts of crime. A more aggressive form of vigilantism is to patrol outside asylum centres, homes for refugees, schools for minorities or even inside villages inhabited by Roma people or other minorities. The intention—or the outcome—might be to prevent the people living there from going outdoors, or to leave their homes entirely.

Although some vigilante groups make extensive use of violence, most do not actually carry out acts of violence. However, they customarily display a violent capacity through the performance of force, whether they parade as a paramilitary militia (with or without weapons), or patrol the streets in groups dressed in group symbols or uniforms. Their display of force is obviously intended to have an intimidating and deterring impact on their designated target groups as well as political opponents.

Influential Factors: The Emergence and Decline of the Far Right

Several factors come together to encourage the emergence and spread of far-right and vigilante ideas:

- A widespread perception of crisis and threat to their society and life style—real or imagined—which is magnified by extensive media coverage and far-right rhetoric;

- The identification of criminality with specific groups (the recent focus is on migrants), who then become objects of hatred and fear;

- The occurrence of specific shocking events, such as the New Year’s Eve 2016 celebrations in Cologne, where local women were sexually harassed and abused by men of mainly North-African and Middle-Eastern origin, which caused a moral panic;

- The perception that the police and other authorities are either unable or unwilling to protect the citizens from threats to their safety;

- A lack of trust in governmental institutions in general, and the police in particular;

- Liberal and permissive legal frameworks for gun ownership and armed self-defence;

- A historical tradition characterised by frontier justice, lynching and a popular culture where street justice and revenge are glorified;

- The tacit acceptance or active support of this kind of violence by police and other authorities; and

- A base of support among the public or among political parties.

Obviously, the absence, reduction or reversal of the facilitating conditions described above may also serve as impeding factors. However, there also exist additional conditions that may play a role in reducing the appeal of far-right movements and vigilantism:

- When the perceived threat is reduced or appears less acute;

- When the police and other authorities are able to demonstrate that they are in control of a situation;

- When there is a level of trust and respect in the police and other authorities;

- When the police and other authorities strike down hard on vigilante violence and hate crime, and legislation exists to support such enforcement; and

- When the inherent inclination towards internal conflict in extreme-right movements leads to a dissolution of their activities.

Right-wing and vigilante groups and their activities tend to emerge and flourish in settings where there is a convergence of several facilitating conditions and an absence of impeding or repressive factors. They fail and decline when the facilitating conditions are reduced and repressive measured are implemented against them.