Evaluation of the Open Government Program

On this page

- Introduction

- Results at a glance

- Program profile

- Roles and responsibilities

- Stakeholders

- Expected outcomes

- Evaluation methodology and scope

- Limitations of the evaluation

- Relevance

- Performance

- Economy

- Recommendations

- Appendix A: logic model

- Appendix B: evaluation methodology

- Appendix C: Management Response and Action Plan

Introduction

This document presents the results of an evaluation of the open government program, which is administered by the Office of the Chief Information Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS).

The evaluation was carried out by the TBS Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau, with the assistance of Goss Gilroy Inc., and was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results. The evaluation assessed the relevance and effectiveness of the program. It was a formative evaluation and therefore covered immediate outcomes only. It covered fiscal years 2016–17 to 2018–19. Documents were reviewed for all years since 2011, when the program started.

Results at a glance

The open government program’s continued communication efforts have increased stakeholder awareness and engagement. Improved use of strategic communications with underrepresented groups, such as Indigenous peoples and youth, could further strengthen program relevance.

Provincial representatives expressed that they would like to see greater alignment between the federal government’s open government initiatives and its digital strategy. Making open government part of a broader digital strategy has, in the opinion of provinces that have done so, improved their open government programs.

The program has made progress on commitments made and milestones set under the National Action Plan (NAP) since 2012. Although TBS is the lead department, it holds a disproportionate degree of accountability for many of these commitments and milestones. A culture of open government would need broader distribution of open government activities across the federal departments and agencies.

The program’s open data and open information portal at www.open.canada.ca gives the public increased access to government information; however, the current version of the portal has technical limitations.

The program has improved public servants’ understanding of open government principles and practices to some extent. The improvement is most evident among open government coordinators and in departments that have empowered those coordinators to establish a culture of open government.

The Government of Canada needs to develop a strong vision of open government. Evaluation participants described how greater recognition of the open government coordinator role and increased engagement of senior public service executives could improve open government practices enterprise‑wide.

Program profile

Background

The Access to Information Act is an early example of increasing government transparency, a key principle of the Open Government program. The federal government has been making government information available to the public through the Access to Information Act since 1982. The act gives any Canadian citizen the right to request and receive information from federal institutions. The purpose of the act is:

Nova Scotia has had access to information legislation since 1977, and Quebec passed its legislation in the same year the federal legislation was passed. Most other provinces and territories passed their own laws soon after the federal legislation was enacted.

In May 2010, the federal government launched an online consultation website as part of the Digital Canada 150 initiative. This initiative invited Canadian citizens to submit proposals to an online ideas forum. Forum participants then commented and voted on the proposals. The proposal selected was for an open data initiative governed by open government principles. In March 2011, the Government of Canada launched the first version of its open data portal, at www.data.gc.ca.

On the international stage, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) was founded in 2011, when government leaders and civil society advocates came together to promote accountable, responsive and inclusive governance. Canada signed on to the OGP in April 2012.

OGP members, which consist of representatives of 78 countries, 20 local governments, and many civil society organizations, represent more than 2 billion people.

The OGP’s vision is that greater government transparency, accountability and responsiveness to citizens will improve the quality of governance and services provided to citizens.

To join the OGP, a country must:

- submit a letter of intent ratifying the Open Government Declaration of September 2011

- exhibit a demonstrated commitment to open government in four critical areasFootnote 2

- pass the OGP values checkFootnote 3

Once the country has been accepted as a member, every 2 years it must develop a NAP that complies with the principles, standards and timelines set by the OGP. It must also establish a multi‑stakeholder forum. The country must then submit periodic self‑assessment reports and be evaluated every year through an independent reporting mechanism.

Canada co‑chaired the OGP between 2018 and 2019, with Nathaniel Heller, executive vice president of integrated strategies at Results for Development, as the lead civil society co‑chair. In his new co‑chair statement, Mr. Heller expressed the OGP’s vision as follows:

Canada’s vision of open government, both as a member and as OGP co‑chair for 2018–19, is consistent with the principles identified in paragraph 2(1)(a) of the Access to Information Act:

Work on the open government program has caused these original principles to evolve in the context of an increasingly digital environment.

Citizens no longer expect government to simply respond to access to information requests (in other words, to be reactive). They expect it to make data open and to disclose information upfront (in other words, to be proactive). Meeting these expectations “will require a shift in norms and culture to ensure genuine dialogue and collaboration between governments and civil society.”Footnote 5 For Canada’s open government initiatives to succeed, this shift must happen throughout the federal public service.

Roles and responsibilities

The President of the Treasury Board and the Minister of Digital Government are responsible for coordinating Canada's open government initiativesFootnote 6 and are Canada’s ministerial representatives in the OGP.

TBS’s role in open government is twofold:

- As a leader, it encourages and models excellence in public sector practices

- As an enabler, it helps federal departments and agencies improve management performance and program results.

TBS developed the Policy on Information Management and the Directive on Open Government. As the official holder of the government’s open government licence, it oversees federal open government websites and services; and makes sure that departments comply with the technical formatting rules to meet their open government requirements.

The Office of the Chief Information Officer of Canada, which is part of TBS, develops and oversees the activities needed to effectively fulfill open government commitments.

Eighty‑nine departments and agencies that are listed in section II of Schedules I, I.1, and II of the Financial Administration Act (with some exceptions) have committed to supporting and implementing the Treasury Board Directive on Open Government. The objective of the directive is:

Departments and agencies (and at times, other levels of government) provide data on open.canada.ca, the Government of Canada’s open government portal, which is a building block for longer‑term goals of the program.

Stakeholders

The following stakeholders are not only beneficiaries of open government; they also help shape program activities.

Civil societyFootnote 7 serves as a liaison between the federal government and segments of Canadian society represented by elected members of the multi-stakeholder forum. The forum provides perspective on the development of the NAPs.

The Indigenous community plays a role in reducing barriers to accessing information and in rebuilding trust in relation to the use of data affecting Indigenous people.

Academics identify challenges and suggest ways in which the program could improve its intended outcomes. Some academics work exclusively on open government. The OGP Independent Reporting MechanismFootnote 8 is fulfilled by an academic who has expertise in open government.

Other governments, both domestic and international, contribute to evolving open government.

Canadian citizens, as the end users of government information, are the motivation for open government program activities. The program seeks to build citizens’ trust in government by increasing transparency, engagement and data sharing.

Expected outcomes

-

In this section

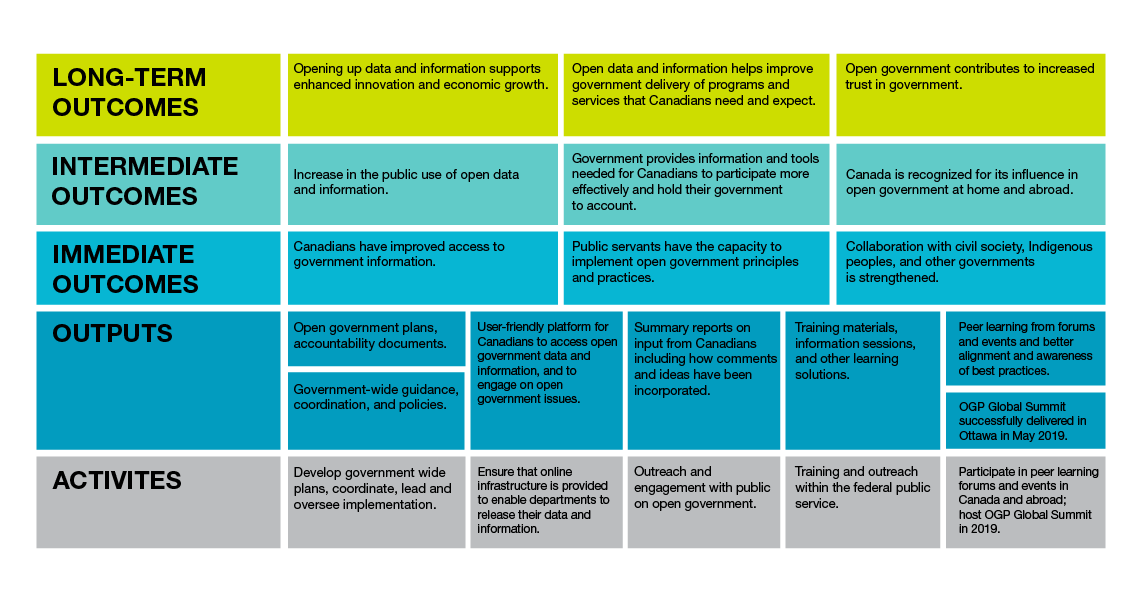

The expected outcomes of the program, as shown in the logic model in Appendix A, are as follows.

Immediate

- Canadians have improved access to information

- Public servants have the capacity to implement open government principles and practices

- Collaboration with civil society, Indigenous peoples and other governments is strengthened

Intermediate

- Increase in the public use of open data and information

- Government provides information and tools needed for Canadians to participate more effectively and hold their government to account

- Canada is recognized for its influence in open government at home and abroad

Long-term

- Opening up data and information supports enhanced innovation and economic growth

- Open data and information helps improve government delivery of programs and services that Canadians need and expect

- Open government contributes to increased trust in government

Evaluation methodology and scope

The evaluation assessed the program’s relevance and performance (effectiveness and economy) by using multiple lines of evidence, in proportion to the program’s risk and materiality. A logic model (see Appendix A) clarifies the expected outcomes and the assumptions or considerations needed for the desired results to occur.

The evaluation assessed the achievement of immediate outcomes only. Because the program had only been receiving direct funding since 2016–17, intermediate and long‑term outcomes could not be assessed.

Appendix B provides a detailed description of the methodology. The lines of evidence were:

- a program data and document review

- a literature review

- jurisdictional study

- 28 key informant interviews

- 7 focus groups

Limitations of the evaluation

Evaluators had planned to interview more Indigenous people and youth in the evaluation. Because of logistics, some of these groups could not participate directly. Evaluators therefore used other means to collect information on the experiences of members of these groups with open government. For example, they consulted public servants and members of civil society who work with Indigenous people and youth about the issues faced by members of those groups. They also conducted two interviews with representatives of Indigenous organizations who work in the open government space.

In addition, during the 2019 Open Government Summit, evaluators attended multiple sessions on the experiences of diverse groups including youth and Indigenous people.

Relevance

Ongoing need for the program

Conclusion

The open government program continues to meet Canadians’ need for greater access to government information.

Clearer and more strategic communication with underrepresented groups could improve the identification of, and response to, their specific needs and could increase their participation.

Findings

Ongoing need for the program is expressed by increasing levels of public participation in program activities. The program has responded to the demand by:

- continuing to involve domestic partners and Canadians in creating the NAP

- responding to stakeholder groups’ evolving requests and needs

Canada’s NAP:

- details the government’s commitments for the next 2 years

- specifies which departments and agencies are responsible for fulfilling the commitments

- sets milestones for progress on the commitments

The NAP is developed in consultation with the public, civil society organizations and other levels of government.

Reports on the consultation process indicate that public participation in the process increased significantly between 2012 and 2019 (from 260 participants to over 10,000). Engagement approaches now include questionnaires, as well as in‑person and online consultations.

This increased participation demonstrates not only stakeholders’ growing interest in the NAP process, but also their ongoing need to be involved. The increased participation is partly a result of better communications.

The improved communications were evidenced by the program’s response to comments from the public. Previously, the program provided little feedback; it now responds to every comment. Each response consists of:

- an interpretation of the comment

- an explanation of how the program has chosen to respond when applicable, an explanation of why no action can be taken

Responding to individual comments strengthens communication with the public and improves the relationship between the government and the public.

Direct response to public comments was also provided in the 2018 “What We Heard” report. The report addresses comments received during consultations on the 2018–20 NAP. These consultations informed the program’s subsequent engagement efforts, which enhanced its value to partners and stakeholders alike. The report lists a number of lessons, which the program incorporated into its future work. Two of these lessons were as follows:

- Consistent, sustained dialogue with stakeholders is more valuable and meaningful for both parties than are one‑off conversations at the beginning of the NAP consultation process

- Community partnerships are important when hosting events across Canada. They provide direct contact with the public and civil society organizations. They also provide opportunities to showcase open government initiatives and build new relationships

The results presented in the “What We Heard” report informed the decision to use the following four strategies to improve engagement and awareness in developing the 2018–20 NAP:

- Partner with and support community‑based organizations and neutral third parties to serve as intermediaries between government and under-served populations

- Support communities in navigating government complexity, with the objectives of building sustained relationships, providing a venue for communities to identify issues for discussion, and improving two‑way communications

- Improve the capacities of departments and agencies to engage with under‑served communities, especially to identify how upcoming policy decisions, data collection strategies and access to information requests may impact specific populations

- Develop standards for data‑handling, reporting and communication that take into account context and the needs of under-served communities, such as privacy, accessibility and context

By applying the lessons learned that are listed in the “What We Heard” report to the NAP, the open government team responded to the expectations and needs of program stakeholders. This responsiveness shows that the team understands that improving public awareness of open government initiatives increases the opportunity for the public to be involved in these initiatives. Based on the evidence from the document review conducted as part of this evaluation, increased engagement and participation demonstrates an underlying public need for the program’s activities.

Including awareness and engagement activities in the NAP as identified above shows a commitment to continued improvement in these areas, which also strengthens the program’s relevance more broadly. Although communication and engagement efforts have increased since 2012, the program could further improve in some areas.

The document review indicated a lack of strategic communication, which may have limited stakeholders’ understanding of how the program can benefit individual Canadians. Focus group participants noted a need to clarify what open government really means for Canadians.

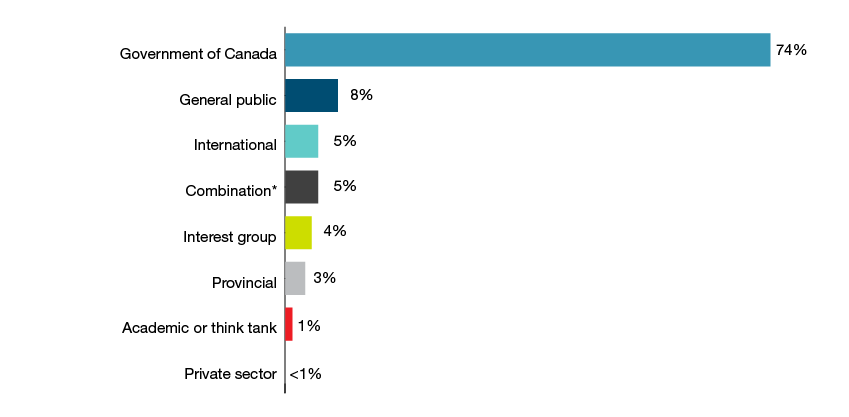

All interviewees felt that the open government program was overly focused on consulting with public servants and not enough on consulting with the general public, particularly in the early years of the program. Public servants who participated in the evaluation indicated that among their respective stakeholder groups, those who could benefit from open government initiatives did not always know about them. An examination of learning events that have taken place since 2016 shows that most of them continue to be directed at federal public servants. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of learning event participants over 2 years.

Participants in interviews and focus groups conducted for this evaluation indicated that although the program has recently increased engagement with the public, it still has work to do to fully engage underrepresented groups such as Indigenous communities, youth, seniors, and people living in rural communities. By continuing to apply the lessons learned in 2018–2020, by fulfilling commitments similar to those made in the 2018–2020 NAP, and by making concerted efforts to involve under-represented groups the program may help increase their engagement.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 is a bar chart showing the breakdown of participants in learning events from 2016 to 2018, by audience type.

- 74% were from the Government of Canada

- 8% were from the general public

- 5% were international

- 5% were from a combination of all other categories

- 4% were from interest groups

- 3% were from provincial governments

- 1% were from academic institutions or think tanks

- Less than 1% were from the private sector

*Combination is distinct and not represented in other categories.

Clarity in roles and responsibilities between federal and provincial and territorial government

Conclusion

The evidence did not demonstrate any issues with roles and responsibilities.

Findings

At the time of publication, 8 provinces and 1 territory had open government programsFootnote 9. The program coordinates the Canada Open Government Working Group a federal, provincial, territorial body. This working group aims to create a multi-jurisdictional framework on open government and to find overlap and commonalities.

The working group’s efforts have yielded positive results for open government initiatives across the country. The document review conducted for this evaluation shows that the working group has advanced the following:

- adoption of an open data charter

- standardization of high‑value datasets

- federation of open data search capabilities between the federal government and the government of Alberta

- building data literacy and associated technical skills among public servants

- establishing a coordinated mechanism for public dialogue and engagement across Canada

Evidence gathered from both the interviews and the focus groups reveals widespread agreement that the federal government has played an important role in creating a baseline for open government activities in all provinces and territories that have open government programs. Ontario has achieved progress by joining the OGP; Saskatchewan is working to formalize its open government activities; and other provinces are continuing to launch open government programs. All provincial representatives indicated that they are well served by the skills and direction the federal open government program provides.

Provincial representatives stated that their relationship with the program has room to mature. They would like to see open data evolve to include open information and open source code development initiativesFootnote 10.They would also like to see greater alignment between open government and the Government of Canada’s digital strategy. According to the provinces that have done so, making open government part of a broader digital strategy has improved their open government programs.

Performance

-

In this section

- Differences in design and implementation

- Immediate outcome 1: Canadians have improved access to government information

- Immediate outcome 2: Public servants have the capacity to implement open government principles and practices

- Immediate outcome 3: Collaboration with civil society, Indigenous peoples and other governments is strengthened

Differences in design and implementation

Conclusion

Since 2012, the open government program has made progress on the commitments and milestones that are set out in the NAP and that have served as the program design frame. The program also aligns to some extent with the open government principles of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Findings

The evaluation found no specific documentation that describes the design of the program. It therefore assessed the implementation of the program against the OECD’s open government principles and against the commitments and milestones set out in the NAP as the design frame.

OECD principles as design frame

Research by the OECD into how countries are implementing open government practices identified 8 elements that enable an open government initiative to thrive:

- executive (political) and business (public administration) sponsors, and good communication between them

- strong central leadership that provides clear strategy and focus

- a clear plan and a practical way to carry it out

- implementation of the plan in collaboration with members of civil society who share the same vision

- inclusion of open government principles in competency and accountability frameworks, as well as in performance agreements, to change culture and behaviour

- re-examination of information management measures, including access to information measures

- a well-defined legal framework as the basis for reform

- focus on citizen-driven approaches to service design and delivery

According to interviewees, the federal program meets these 8 elements to some extent. They indicated that:

- Canada’s NAP could be more ambitious

- more buy-in is needed at the senior management level

- legislative and policy frameworks related to official languages and accessibility cause lags in publishing open information and data. Legal issues related to data ownership can also inhibit open publication

- access to information legislation must be strengthened

National Action Plan as design frame

The NAP, a requirement under Canada’s membership in the OGP, outlines open government initiatives that the Government of Canada commits to achieving in a 2‑year period. Led and coordinated by the TBS open government team, the NAPs to date (2012–2014 to 2018–2020) have been developed through widespread discussions with various stakeholder communities in Canada and take place in a number of phases:

- planning and priority-setting

- gathering ideas for commitments

- commenting on, debating, and refining ideas for commitments

- drafting potential commitments

- publicly reviewing draft commitments

- finalizing the plan

An examination of all of Canada’s NAPs to date shows that open government in this country has matured significantly, as evidenced by the increases in the following:

- the number of federal departments and agencies carrying out open government activities

- the quantity and quality of feedback on ideas for each new action plan, and feedback during the drafting of each plan

- the degree to which civil society’s role in designing and implementing open government activities is appreciated

- the transparency of the plans (there are clearer responsibilities attached to each commitment; there is an explanation of what success looks like and how to measure it; and there are more robust implementation measures because of broader engagement with communities)

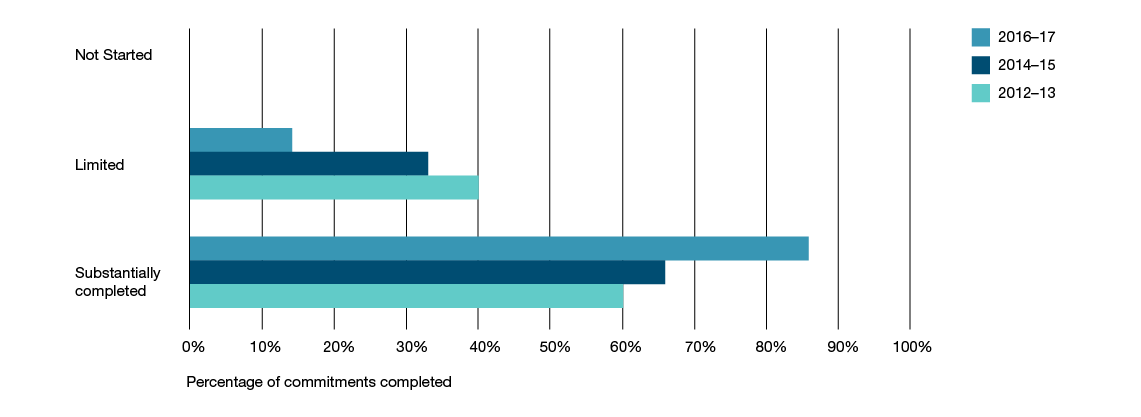

The document review showed that the proportion of substantially completed NAP commitments increased from 60% in 2012–13 to 86% in 2016–17Footnote 11. Figure 2 shows the completion status of NAP commitments.

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 is a bar chart showing the completion status of National Action Plan milestone commitments.

| Completion status | Year | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Not started | 2012–13 | 0 |

| 2014–15 | 0 | |

| 2016–17 | 0 | |

| Limited completion | 2012–13 | 40 |

| 2014–15 | 33 | |

| 2016–17 | 14 | |

| Substantial completion | 2012–13 | 60 |

| 2014–15 | 66 | |

| 2016–17 | 86 |

The long-term goal of the program is for open government to be the norm in the federal government. An increase in the number of departments and agencies that have NAP commitments, as well as the devolution of commitments from TBS to departments and agencies would indicate increased support for open government objectives.

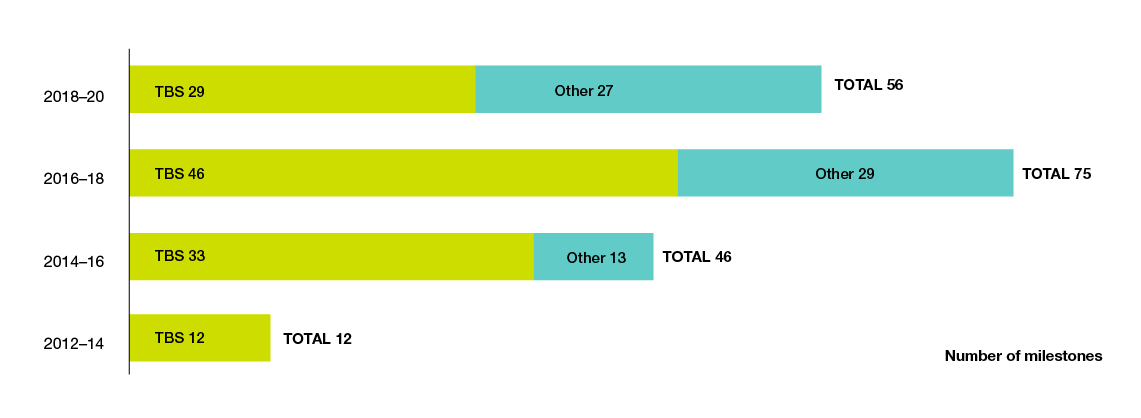

Figure 3 shows, for each NAP cycle, the total number of milestones for which the federal government had commitments and the breakdown of these milestones between TBS and other departmentsFootnote 12.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure 3 is a bar chart showing, for each NAP cycle, the total number of milestones for which the federal government had commitments and the breakdown of these milestones between TBS and other departments.

| Plan cycle | TBS | Other departments | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–14 | 29 | 27 | 56 |

| 2014–16 | 46 | 29 | 75 |

| 2016–18 | 33 | 13 | 46 |

| 2018–20 | 12 | 0 | 12 |

The number of departments and agencies with commitments has grown since Canada’s first NAP. In 2012–2014, a total of 12 departments and agencies committed to a milestone. This number grew to 46 in the 2014–2016 NAP, 75 in the 2016–2018 NAP, and 56 in the 2018–2020 NAP.

| Department name | Count |

|---|---|

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat joint with another department | 70 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 50 |

| Joint responsibility of departments other than Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 21 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 9 |

| Canadian Heritage | 7 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 6 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 4 |

| International Development Research Centre | 4 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 3 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 3 |

| Women and Gender Equality Canada | 3 |

| Statistics Canada | 2 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 1 |

| Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario | 1 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 1 |

| Privy Council Office | 1 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 1 |

| National Research Council Canada | 1 |

Table 1 shows the number of milestone commitments assigned to each department, either in isolation or in partnership with another department across all NAP cyclesFootnote 13. Only 17 departments and agencies have at least 1 NAP commitment in at least 1 NAP, and only 10 of these have had more than 1 milestone commitment for which they are solely accountable in all 4 NAPs to date.

Although not every open government activity in the federal government is identified in Canada’s NAP, this plan represents the highest level of documented accountability for such activities. The NAP process sets expectations for addressing milestone commitments created with citizens, civil society, private industry, provinces, territories, and international partners.

Figure 3 and Table 1 clearly show that TBS is at least partially accountable for most NAP milestone commitments. The evaluation found that part of the reason for this is TBS’s role as coordinator of Government of Canada open government activities. Given the concentration of so much accountability at TBS and further findings detailed in the Economy section of this report, there are concerns about whether the open government program will be able to continue to deliver on all its commitments.

Immediate outcome 1: Canadians have improved access to government information

Conclusion

The program has increased public access to government data and information by requiring departments and agencies to publish their data and information on the open government portalFootnote 14. The portal’s potential is limited, however, due to technical challenges.

Findings

The open government portal was created to provide Canadians with greater access to government information and data of business value. It is the main mechanism for accessing open data and open information.

In 2012–13, responsibility for the portal was transferred from Environment Canada to Statistics Canada. In 2017–18 the portal became the sole responsibility of TBS. New features were then added, such as proactive disclosure, geospatial maps and searchable summaries of access to information requests.

With the introduction of the Directive on Open Government in 2014, the 89 departments and agencies that fall under this instrument were required to create inventories of their datasets. According to interviewees, although the process of creating the inventories was difficult for organizations, it was a good start for introducing open data concepts more widely. These inventories also supported departments in releasing datasetsFootnote 15 to the open government portal. For example, the total number of non‑geospatial datasets made available between 2016–17 and 2018–19, grew by 1,108, for a total of 11,340 available on www.open.canada.ca.

Interviewees from TBS and Statistics Canada noted that the best way to get a detailed understanding of use is to develop sophisticated user profiles.

Interviewees stated that the program is now focusing on examining how such data and information related to user experience can be used to improve the portal. The program has invested in developing:

- a technical solution that checks on the timing of new entries, downtime, broken links, spelling errors, and so on

- an exercise to understand how users interact with the portal (for example, how people click to move through the website)

According to interviewees and focus group participants, despite the program’s success in “opening up” information and data by providing access to it through the open government portal, challenges remain:

- The portal is neither flexible nor user-friendly, and it is difficult to find the information sought.

- The portal lacks a strategic plan that gives priority to enhancing the portal and that provides structure for the portal team’s operational plan

- The portal team has limited budget and limited skills (for example, only one person is assigned to maintaining Drupal, the operating system used for the portal)

- When federal organizations are brought on to the portal, the portal team must provide extensive support to, for example, manage uneven metadata and provide advice on how to publish data

- The new amendments to the Access to Information Act that received royal assent on June 21, 2019, are expected to increase workload

- Requirements relating to accessibility and official languages limit efficiency when new material is added to the portal

- More discussions are needed among lead data departments regarding adaptive and inclusive data sharing, data stewardship, and the roles of departments and of TBS. Such discussions could help reduce silos in these areas

Immediate outcome 2: Public servants have the capacity to implement open government principles and practices

Conclusion

Public servants understand and are equipped to implement open government principles and practices to some extent. Further implementation of these principles requires a clear vision, strategic communications, and a strengthened role for open government coordinators.

Findings

In 2018, program staff developed an Open Government Guidebook, in collaboration with 25 departments and agencies. The guidebook contains best practices and tools for putting in place open government processes. It also provides guidance for implementing the Directive on Open Government to help ensure consistency in open data and information practices across government. Interviewees noted that the guide is a good educational tool for staff in departments and agencies, especially for open government coordinatorsFootnote 16.

The open government program has also launched a learning hub on the Canada School of Public Service website and has held a series of learning events. These events, which include talks for executives and armchair discussions for a broad audience, aim to increase understanding and awareness of open government.

Interviewees indicated that program staff are inundated with requests from departments for stakeholder engagement. However, for culture change to happen, departments need to take on this responsibility. The program team recognizes that equipping departments in this way would require more education and support in departments.

Recently, program staff drafted a training strategy for open government coordinators. The strategy consists of four different public service skills development packages for open government coordinators to use when facilitating training sessions in their department or agency.

Interviewees agree that culture change requires hard work, time and an understanding of many areas relating to open government. “Open by default,”Footnote 17 for example, depends on changing public servants’ behaviour so that they work more in the open. Getting people to change their behaviour can be challenging.

Focus group participants felt that for public service culture to become more open, TBS and departments and agencies need to provide more direction, support and guidance to staff. This means having sufficient resources for more full‑time open government coordinators, and for others who fulfill this role as part of their regular jobs. Interviewees also felt the program needs to put more emphasis on enabling departments and agencies to engage their respective stakeholders.

Addressing the issues of culture and resourcing falls outside of the program’s mandate. Direct authorities for resourcing and external engagement fall within the purview of departments and agencies. The program can, however, work with departments to address the underlying issues of the open government coordinator role.

Open government coordinators and program staff explained to evaluators that even when the role is filled, it is often poorly defined, informal and under‑resourced. Participants in the coordinator focus group indicated that that they do their open government work on top of their regular duties, which makes it difficult to respond to requests effectively. Interviewees also explained that they have difficulty obtaining senior management support for open government if their organization has no milestone commitments in the NAP.

Focus group participants and key informants highlighted two departments’ good open government practices:

- executive sponsorship for the open government function means that the function has the necessary visibility and formality to develop in the organization; executive sponsorship could be from an executive committee, a specific ADM in the organization, or the minister

- creation of a governance committee to oversee progress on their organization’s open government activities

- moving beyond mere compliance to true stakeholder engagement in order to implement a change agenda in their organizations (actions include surveying staff and management to find out what support they need and why, designing and implementing a series of clear communication products, working with sectors to create open government plans, and training sector coordinators on data quality).

The two departments were asked to outline what they believe worked well and what else they needed from the TBS open government program.

They stated that the following worked well:

- the clarity of the documentation on eligibility and prioritization of data

- the requirement for the department or agency’s chief information officer to sign off on datasets ensures that senior management is engaged

- the requirement that an indicator in the Management Accountability Framework be devoted to open government ensures that senior management remains engaged

- TBS’s growing role in helping departments and agencies that are already following best practices to connect with other departments and agencies to increase learning

They stated that they needed the following from TBS to continue to implement open government effectively:

- a maturity model for open government and more guidance on how to launch open government, including how to sustain momentum on open government when the organization has no milestone commitment in the NAP

- a plan for training employees who are not involved in open government in their day‑to‑day work

- inclusion of a commitment to open government in all executive performance management agreements

- more engagement with senior managers

Immediate outcome 3: Collaboration with civil society, Indigenous peoples and other governments is strengthened

Conclusion

Open government has strengthened partnerships with civil society, Indigenous groups and other governments, particularly through the multi‑stakeholder forum. However, more continues to be needed in underrepresented groups.

Findings

Under Canada’s commitment to the OGP, the program must have a multi‑stakeholder forum. Canada’s multi‑stakeholder forum was officially launched on January 24, 2018 and has 12 members. The criteria for the composition of the forum are as follows:

- 8 members must come from outside of government, and at least 6 of these members must be from not-for-profit organizations registered in Canada

- 4 must be representatives for the Government of Canada

Through a consultative, consensus-building process, the multi-stakeholder forum promotes dialogue between government and stakeholders on open government policies, with a focus on the development, implementation and assessment of the NAP. The forum also serves as the interlocutor between government and civil society.

Both focus group participants and interviewees believe the multi‑stakeholder forum has been effective, although they agreed that it took some time for TBS and the members of the forum to figure out how best to work together.

The program strengthened its relationship with the multi‑stakeholder forum as a result of two key actions:

- The program invited all federal organizations that had a NAP commitment to meet face-to-face with forum members and to report on their progress to date.

- The Assistant Deputy Minister responsible for the program attended the entire session, which demonstrated to members the importance of building a relationship between government and civil society.

Focus group participants and interviewees felt that the multi‑stakeholder forum is at a turning point because of four factors:

- the uncertainty of where open government fits in the priorities of the new government mandate

- the need to define the role of the forum beyond the NAP process to address institutional elements, such as policy (a need faced by all OGP member countries)

- the need to review forum membership to ensure that it reflects Canada’s diversity

- the difficulty recruiting representatives from civil society organizations because of the time commitment

Focus group participants and interviewees felt that Canada has strong partnerships, both domestically and internationally. Many of them mentioned Canada’s hosting of the 2019 OGP Global Summit as an example of these partnerships.

Based on the document review, the program has engaged various Indigenous organizations since 2017. All program staff have participated in training provided by Reconciliation Canada.

Evaluation participants frequently raised the need to build trust with Indigenous partners regarding data use and ownership. Interviewees noted that there is positive engagement between Indigenous groups and the program team but that there is frustration with TBS, which is seen as slow‑moving. Some interviewees expressed frustration with other departments and agencies for not taking advantage of the many opportunities to join together to engage Indigenous groups.

Economy

-

In this section

Conclusion

The open government program is not functioning as economically as it could. A medium‑ and long‑term strategic plan that would include a more stable set of pre‑determined priorities could make the program more economical.

Findings

At the time of data collection, both the document review and key informants indicated that the program uses a large number of term and contract employees and employees on secondment, staffing scenarios that are associated with high staff turnover.

The high turnover increases the time spent on staffing, decreases productivity and leads to the loss of corporate knowledge, all of which increases costs. Based on interviews and program data, the evaluation found that this issue was not limited to the period leading up to the OGP Global Summit, which Canada hosted in May 2019.

In addition, interviewees stated that the absence of a strategic plan for the program makes it difficult to feel confident about its sustainability. They explained that the program is young (funding for it began in 2016–17). With its focus on program implementation and then on coordinating a global summit, little attention has been given to strategic planning.

Interview and focus group participants feel that the 2‑year NAP cycle is too short to identify strategic program goals and to plan effectively for the future. Many interviewees indicated that ad hoc requests and changing priorities limit the medium‑ and long‑term impacts the program could otherwise have. Nevertheless, with the conclusion of the OGP Global Summit, the program can now prioritize strategic planning.

Participants in federal government employee focus groups noted both duplication and under‑use of open government activities across the federal government, partly as a result of the tendency to work in silos. According to them, better coordination and more engagement among departments would make open government activities more efficient at an enterprise level.

As mentioned earlier, TBS plays a disproportionately large role in implementing open government activities. Greater participation by departments, independent of TBS, would demonstrate a broader culture change. According to interviewees, one of the concrete ways TBS can support enterprise‑level approaches to open government is by working with departments to formalize the role of front‑line open government coordinators.

Recommendations

- It is recommended that the open government program develop a strategic plan and vision commensurate with its resources. This would help set priorities and frame strategic communications with senior management across government. Special attention should be paid to the open government portal, which is the program’s core component.

- It is recommended that the program, with the support of departments, more effectively implement open government priorities and activities across the Government of Canada by formalizing the open government coordinator role.

- It is recommended that the program develop and implement a plan to more actively engage and partner with underrepresented groups. Particular focus should be paid to ensuring that the multi‑stakeholder forum includes diverse voices and that issues important to Indigenous peoples, such as data sovereignty and meaningful consultation, are addressed.

Appendix A: logic model

Figure 4 - Text version

The figure in Appendix A depicts the logic model used for the Centralized Language Training Program.

The main components of the Centralized Language Training Program are:

- activities

- outputs

- immediate outcomes

- intermediate outcomes

- long-term outcome

The program activities are:

- Develop government wide plans, coordinate, lead and oversee implementation.

- Ensure that online infrastructure is provided to enable departments to release their data and information

- Outreach and engagement with public on open government.

- Training and outreach within the federal public service.

- Participate in peer learning forums and events in Canada and abroad; host OGP Global Summit in 2019.

The program outputs are:

- Government-wide guidance, coordination, and policies.

- Open government plans, accountability documents

- User-friendly platform for Canadians to access open government data and information, and to engage on open government issues.

- Summary reports on input from Canadians including how comments and ideas have been incorporated.

- Training materials, information sessions, and other learning solutions.

- OGP Global Summit successfully delivered in Ottawa in May2019

- Peer learning from forums and events and better alignment and awareness of best practices

The immediate program outcomes are:

- Canadians have improved access to government information.

- Public servants have the capacity to implement open government principles and practices.

- Collaboration with civil society, Indigenous peoples, and other governments is strengthened

The intermediate program outcomes are:

- Increase in the public use of open data and information.

- Government provides information and tools needed for Canadians to participate more effectively and hold their government to account.

- Canada is recognized for its influence in open government at home and abroad.

The long-term program outcomes are:

- Opening up data and information supports enhanced innovation and economic growth.

- Open data and information helps improve government delivery of programs and services that Canadians need and expect.

- Open data and information helps improve government delivery of programs and services that Canadians need and expect.

Appendix B: evaluation methodology

The evaluation was guided by an approved evaluation framework, which was a detailed plan of the evaluation activities, questions and indicators.

Evaluation questions

Relevance

- Does open government respond to the needs of Canadians using the most optimal design and delivery mechanisms? Are there impediments to access?

- Are there differences between open government design and implementation?

- What are the roles and responsibilities of the federal government versus those of the provinces and territories in delivering open government?

Effectiveness

- Do Canadians have increasing access to government information?

- Who should understand and be equipped to implement open government principles and practices versus who currently understands and is equipped?

- What has open government done to strengthen partnerships with civil society? Indigenous peoples? Other governments?

Economy

- Were all of the inputs, such as human resources, goods and services needed? Were any resources used for the program redundant, duplicated, under-utilized or otherwise unnecessary?

Logic model and performance measurement

- What improvements, if any, can be made to the current logic model and performance measurement strategy?

Methodology

Consistent with best practices, the evaluation of open government included multiple lines of evidence to ensure that reliable and sufficient information, both quantitative and qualitative, was produced.

The evaluation consisted of the following methods, which are summarized in the pages that follow:

- a program data and document review

- a literature review

- benchmarking (in other words, jurisdictional review)

- focus groups (n=7, composed of approximately 60 people)

- interviews (n=28)

All methods were triangulated using a grid and then organized by evaluation questions and indicators. The responses were analyzed to formulate the findings, draw conclusions and then make recommendations.

Program data and document review

The documentation and data available on the open government portal formed the foundation of all of the evaluation questions. The document review consisted of a variety of documents, including:

- National Action Plans (NAPs)

- independent review mechanism materials

- “What’s Been Heard” reports

- communications and engagement strategy documents

- terms of references

- working group materials

The data review included a number of datasets, learning events, NAP commitments, and so on. Other documentation from the Open Government Partnership, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and other departments were also examined to further understand context.

Literature review

Open government is part of a collection of new government programming that is being referred to collectively as “open-by-default programming,”. The literature review outlined the epistemological base for an open-by-default program and examined the mechanisms and constructs in program design and delivery. A selection of peer‑reviewed journal articles, books, newspapers and published papers from recognized organizations (for example, the OECD) on open government design and delivery was reviewed and analyzed.

Benchmarking (jurisdictional review)

The benchmarking exercise examined differences in program design and delivery in order to inform the ideal program design for open government. The exercise compared Canada’s design and delivery with that of Australia, Finland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. These countries were selected based on a variety of factors that fall into two categories:

- how much Canada can learn based on the maturity of other open government programs

- the availability of information that is both relatable and context-rich

Focus groups

Although open government is led by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, many of the activities are undertaken by other federal departments and agencies. To assess effectiveness and efficiency, 7 focus groups were formed:

- a sample of directors general from departments and agencies that are responsible for implementing open government activities under the Directive on Open Government (1 focus group)

- a sample of open government coordinators in departments and agencies that have a current NAP commitment and that are implementing open government activities under the Directive on Open Government (1 focus group)

- a sample of open government coordinators in departments and agencies that do not have a current NAP commitment but that are implementing open government activities under the Directive on Open Government (2 focus groups)

- a sample of civil society organizations that have been involved in open government activities (1 focus group)

- a sample of civil society organizations that have not been involved in open government activities (1 focus group)

- a sample of members of the Canada Open Government Working Group (a federal, provincial, territorial working group) (1 focus group)

Interviews

A total of 28 interviews were conducted for the evaluation. These interviews were a qualitative component of the evaluation and addressed most of the evaluation issues and questions. They gathered views and facts from key informants selected from within the federal government and from other organizations (for example, universities). Interviewees were in the following categories:

- program managers and employees from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- staff in best‑practice departments that operating open government programs

- academics who have published research or who are recognized specialists in open government

- members of Indigenous organizations

- representatives from the OECD and the Open Government Partnership

Appendix C: Management Response and Action Plan

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Open Government program has reviewed the evaluation and provided the following comments regarding the report’s recommendations.

| Recommendations | Proposed Action | Start Date | Targeted Completion Date | Office of Primary Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Recommendation 1 |

Management response: Proposed action:

|

|

|

Open Government and Portals |

Recommendation 2 |

Management response: Proposed action:

Considerations will also be given towards leveraging the Policy on Service and Digital and the existing responsibilities of CIOs as well as the various existing communities and governing bodies around open government, data and enterprise architecture. |

|

|

Open Government and Portals |

Recommendation 3 |

Management response: Proposed action:

|

|

|

Open Government and Portals |

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2021,

ISSN: 978-0-660-39004-8