Horizontal Fixed Asset Review – Executive Summary of the Final Report

On this page

Introduction

Federal real estate is at the heart of everything that the government does – from delivering programs and services to Canadians, to building the economy, to realizing broader government objectives. With 32,000 buildings, 23 million square metres (m2) of floor space, approximately 20,000 engineering assets, and 39 million hectares of land, the Government of Canada owns and manages the largest fixed asset portfolio in Canada. The government spends approximately $10 billion annually to administer this portfolio, the replacement value of which is estimated in the order of $100 billion. Approximately 10,525 employees (4% of the federal public service) carry out a variety of real property functions across the government.Footnote 1 Recognizing the value of real estate as a key enabler of program delivery, and the challenges facing this portfolio, the government announced a horizontal review of federal fixed assets in Budget 2017. Led by the President of the Treasury Board with the support of the Comptroller General of Canada, the goal of the Horizontal Fixed Asset Review (the Review) was to identify ways to improve the management of federal real property to generate greater value from government assets.

The Review conducted the most extensive study of the federal real property program in over 35 years and developed detailed observations and a comprehensive suite of recommendations. Highlighting that the status quo is not sustainable, the Review recommends that the government transform how it does business (that is, management of real property) and what it delivers (that is, a modernized portfolio). This transformation will achieve a more proactive and innovative approach that shifts the perception of real property from a cost-driver and source of liability to a strategic platform, positioning Canada for the 21st century and beyond. The benefits of this transformation will be significant given that the reach of the federal real property portfolio extends from densely populated urban centres and northern, rural and remote communities to capital cities around the world. By going beyond the traditional way of managing real property, this portfolio can be leveraged to realize government priorities (for example, fighting climate change and creating jobs), while also increasing efficiencies, unlocking value, and expanding the portfolio’s benefits to Canadians.

Although the Review was launched three years ago, it has never been timelier than now to deliver this comprehensive report on real property management given the significant changes that the novel COVID‑19 pandemic has unleashed in Canada and around the world. These changes have raised questions in all jurisdictions about real estate. From office environments to warehousing, the judiciary, laboratories, prisons and border crossings, what will the built environment look like as the impact of technology accelerates and the long-lasting effects of the pandemic unfold? In a context where we are searching for responses to such questions, the observations of the Review have become more relevant than ever and the implementation of its recommendations even more urgent. The Review has been calling for an integrated, phased transformation that will facilitate a shift from the legacy portfolio and traditional management practices to a modern, agile, right-sized and sustainable portfolio, managed with a forward-looking, strategic and citizen-centric perspective. The current context provides a generational opportunity to turn this vision into reality.

The Review has been a critical starting point for the government’s real property transformation, but it cannot be the journey’s end. The change management that has been initiated by the Review needs to be maintained with a clear mandate, and be accompanied by targeted and intentional actions, with agility, a sense of urgency and speed. This Final Report is the culmination of three years of extensive investigation and analysis. It presents the Review’s observations, recommendations and proposed actions, which aim to facilitate genuine transformational change to create a modern, agile, and financially and environmentally sustainable government real estate that benefits everyone in the 21st century and beyond – government real estate in service of Canadians.

Background

Figure 1: Union Bridge between Ottawa and Gatineau, National Capital Region (circa 1870)

Real property assets acquired or built by the Department of Public Works before and after Confederation attest to the close relationship between the built environment and the socio-economic success of Canada. Between 1867 and 1881, post offices, customs houses, penitentiaries, armouries and immigration ports were constructed, laying the foundation for government programs for the next century. Similarly, federal infrastructure, invoking images of the utilities, bridges, dams, roads and other early symbols of engineering achievements, “changed the face of Canada and helped to propel the country into a new era of prosperity and opportunity.”Footnote 2 For example, federal investments in the transcontinental railway supported western development and economic prosperity, while investments in water and wastewater treatment systems combatted disease and promoted public health. The real property portfolio grew exponentially between 1953 and 1967. During this period, changes to the role and breadth of government programs, including federal developments in northern Canada, penitentiary system reform, the bolstering of Royal Canadian Mounted Police facilities, and the construction of new research laboratories, spurred growth within the federal public service and drove the expansion of the fixed asset portfolio.

Figure 2: Peggy’s Cove, St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia

The federal government’s real estate is still the foundation upon which the provision of federal public services rests. Therefore, it is important to understand how the relationship between real property, evolving government priorities and specific departmental requirements manifests, especially in a context where the landscape of work and the provision of government services are changing significantly due to digital disruption as well as socio-economic and environmental conditions. The management of the federal real property portfolio is currently distributed across 16 departments, 11 agencies and 38 Crown corporations. Deputy heads of custodial organizationsFootnote 3 are accountable for their respective portfolio and must adhere to the legislation and policy frameworks that govern the management of federal real property, such as the Financial Administration Act, the Federal Real Property and Federal Immovables Act, the Treasury Board Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments, and the Treasury Board Policy on Management of Real Property.

Figure 3: Canadian National Vimy Memorial, Givenchy-en-Gohelle, France

Over the years, several reviews have been conducted on the delivery of government programs and the management of federal assets; however, a comprehensive review of real property management has not been undertaken in over 35 years. In 1960, the Royal Commission on Government Organization (also known as Glassco Commission) investigated the structure and methods of operation by federal government departments. Identifying real property as a critical input to program delivery, the Glassco Commission recommended changes to real property management to improve efficiencies.Footnote 4 The 1984 Auditor General’s Report to the House of Commons examined several government-wide activities, including real property. This report identified a “lack of concern with economy and efficiency” in the management of federal fixed assets, which was evidenced by the “failure to manage real property in a way that recognizes its value; failure to comply with policies [as well as] install and use effective monitoring and control systems.”Footnote 5

In 1985, the Ministerial Task Force on Program Review produced a report titled Management of Government: Real Property (known as the Nielsen Report). The recommendations of this report led to the establishment of the real property management model that is still in place today. The Nielsen Report confirmed the decentralized custody model that was in place and recommended the establishment of the Bureau of Real Property Management at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat) to provide central leadership, coordination and oversight functions. The Nielsen Report also recommended the transfer of responsibilities related to the management of general-purpose space (that is, office accommodation) and the provision of real property common services (that is, maintenance, architectural and engineering contracting services) to Public Works Canada.Footnote 6

Figure 4: Nahanni National Park Reserve, Fort Simpson, Northwest Territories

A 1994 Auditor General’s Report to the Parliament noted that while the federal government had implemented a variety of legislative and policy changes since the Nielsen Report, there was still significant room to improve the management of federal real property. This report identified “several constraints to the businesslike management of real property, noting … an urgent need for government to strengthen the central oversight of the management of real property, including improved monitoring practices, and to make changes that will reduce constraints, to ensure that these valuable assets are managed more economically and efficiently”.Footnote 7 The 1994 Auditor General’s Report also recommended that custodians work toward balancing program needs with real property requirements, attend to growing deferred maintenance costs, improve real property accounting practices, pay more attention to real property policy requirements, and establish a centralized data system that links financial information to federal real property assets.

Figure 5: Canadian Coast Guard Search and Rescue Station, Goderich, Ontario

In the 2000s, other reviews, with more limited scope, were conducted, including the Capital Asset Review by the Secretariat (2004), the Capital Asset Management Review by Deloitte (2011), and the Report on Surplus Properties by CBRE (2013). Similar to the 1994 Auditor General’s Report, these reviews highlighted the lack of central leadership, oversight and strategic approach to federal fixed asset management. They also highlighted the absence of an enterprise view of the portfolio, resulting in lost opportunities, inefficient business processes, concerns about the accessibility and quality of real property information, and increasing deferred maintenance costs, with an emphasis on growing operational and asset integrity issues.

Despite these challenges, investments continued to be made in major real property projects (for example, Parliamentary Precinct renovations), individual custodians continued to receive program integrity funding to address rust-out and deferred maintenance issues, and new real property acquisitions continued to take place – the lights have stayed on and government programs and services have been delivered more or less uninterrupted. Yet, these investments have been made in the absence of an integrated, whole-of government perspective, and on a case-by-case basis without a broader context. Moreover, the government made significant investments in federal infrastructure through Canada’s Economic Action Plan in 2009, and, more recently, the Federal Infrastructure Initiative I in 2014 and the Federal Infrastructure Initiative II in 2016. Further, in Budget 2017, the government announced the development of the federal science infrastructure strategy to provide a more integrated approach to future investments in science infrastructure, and in Budget 2018, invested $2.8 billion over five years for the renewal of federal laboratories. Although these funding infusions have helped stabilize the real property portfolio in the short term, there is still a significant need for a long-term solution.

Figure 6: real property beyond the bricks

Did you know…?

- 16 million people visited Canada’s national parks in 2018–19

- 3,584 science facilities support modern science and innovation in Canada

- 25,000 people, namely, soldiers and their families, live in National Defence’s housing units

- The Esquimalt Graving Dock (British Columbia) contributes $183 million annually to the local economy

- 260,000 federal public servants work in the federal office buildings

- 70,000 cars cross the Macdonald-Cartier Bridge (National Capital Region) every day

- 43 correctional institutions across Canada serve increasingly diverse populations and provide spaces for spirituality (for example, healing lodges) and program areas

- 700 RCMP police detachments provide policing services in 150 communities

- 27.3 million cars were processed at 107 land ports of entry in 2017–18

Review framework and methodology

To realize a Budget 2017 commitment, the Secretariat has undertaken a horizontal review of federal fixed assets. Twenty-seven custodial departments and agencies were scoped into the Review (Crown corporations were not in scope). The Review was mandated to assess the federal real property portfolio through an asset class lens, as well as examine horizontal issues trending across the portfolio. The assessment of 4 key and 11 minor asset classes was staged in four phases:

- Phase I: science and technology

- Phase II: office and other (housing, warehousing, commercial and retail, education and training, legislative, judicial and diplomatic)

- Phase III: engineering and other (parks and recreation, assembly and cultural, and managed land)

- Phase IV: security and safety and other (health, medical and dental)

The Review analyzed the federal real property portfolio and asset classes, as well as framed its recommendations through six horizontal themes, outlined in Figure 7.

Figure 7: review assessment framework

Governance

Assess the current governance model (that is, custody, management, oversight) and professional capability in the real property community. Provide recommendations on optimal business model

Leveraging

Explore opportunities to leverage the real property portfolio to achieve broader government objectives (for example, greening, affordable housing, reconciliation, heritage and social purpose) and enhance the value of real property assets for Canadians.

Portfolio management

Assess the state of the real property portfolio (for example, age, condition, utilization) and the maturity of demand and supply integration. Provide advice on the most effective portfolio management practices.

Divestiture

Assess the current state of the surplus property inventory, and provide advice on innovating and streamlining the business processes to accelerate disposals and maximize value.

Funding sustainability

Assess the current financial management environment (for example, expenditures, trends, deferred maintenance, revenues, accounting protocols) and levels of funding to provide advice on long-term funding sustainability.

Information and information management

Assess the current state of real property data and information management systems. Provide advice on how to improve data quality and information management in support of evidence-based decision-making.

Adapting an enterprise transformation methodology, the Review took stock of the federal real property inventory (including extensive qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis), framed a desired state (on the basis of jurisdictional and industry review with a focus on the latest trends and best practice, and consultations with custodians and other stakeholders), identified the gap between the current and desired state, conducted an options analysis, and developed a comprehensive suite of recommendations, along with a roadmap for action. The Review’s research demonstrated that there is no perfect solution that can be readily applied in the Canadian context. Instead, innovative ideas and strategies present in other jurisdictions could be adapted to the Canadian context to formulate effective, made-in-Canada solutions.

Review findings and observations

Profile of the federal real property portfolio

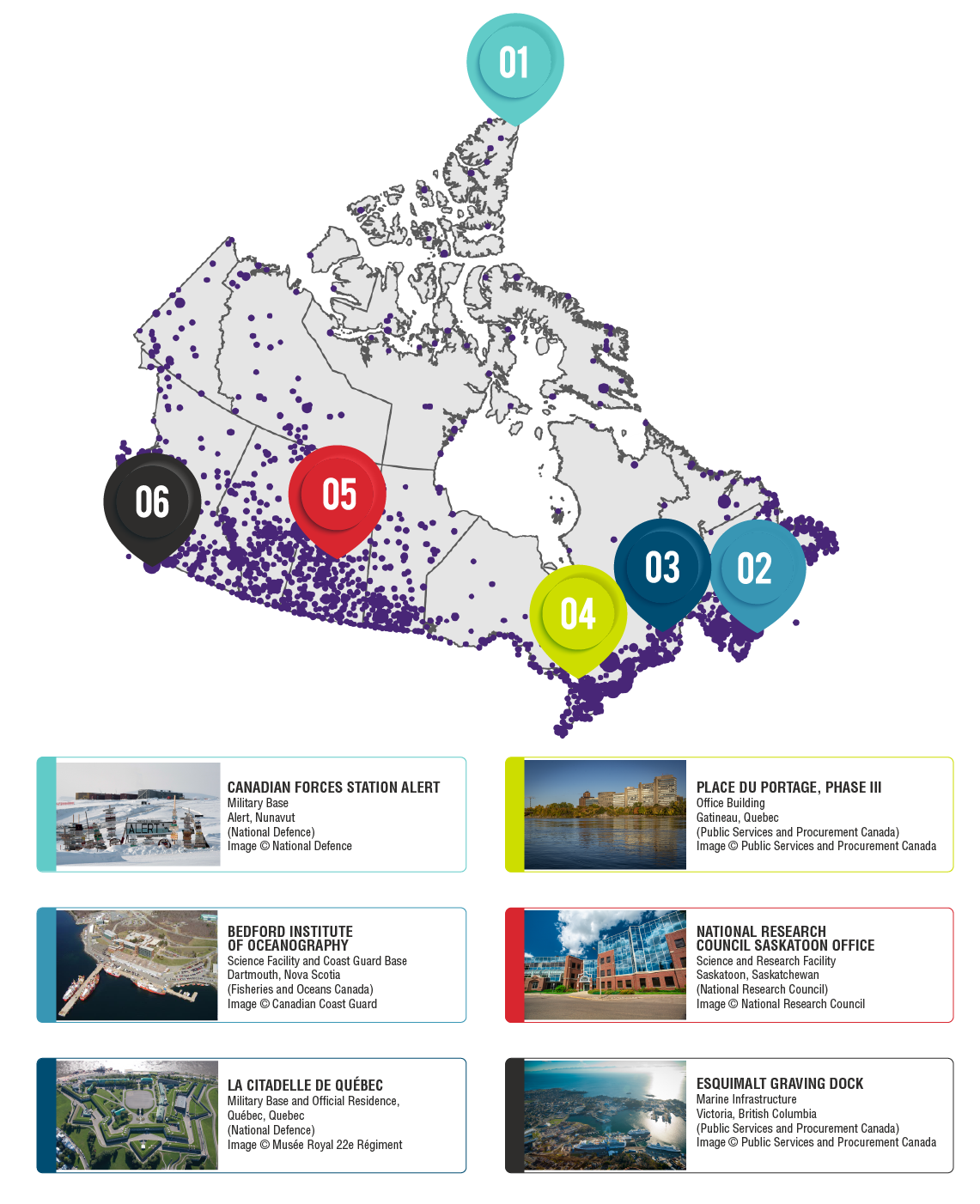

The Government of Canada owns and manages the largest and most diverse real property portfolio in the country, with 32,000 buildings, 23 million m2 of floor space, approximately 20,000 engineering assets, and 39 million hectares of land. This portfolio is distributed across densely populated urban centres and northern, rural and remote communities in Canada as well as capital cities around the world. Ninety-seven per cent of the Government of Canada’s total floor area is located within Canada, and 3% is outside of Canada. Inside Canada, the top five regions that represent the largest percentage of the government’s floor area are the National Capital Region (22%), Ontario (18%, excluding Ottawa), Quebec (13%, excluding Gatineau), Alberta (10%), and British Columbia (9%) (see Figure 8). Map 1 provides examples of the Government of Canada’s real property assets across the country and illustrates the vast geographic distribution and diversity of the assets.

Map 1 - Text version

This map shows a number of locations across Canada, each represented by a dot that is one of four sizes. The smallest dots represent areas where there are one to five Government of Canada buildings within 25 kilometres of a particular location. The largest dots indicate areas where there are 101 to 1,388 such buildings within 25 kilometres of a particular location.

1. Canadian Forces Station Alert

Military Base

Alert, Nunavut

(National Defence)

Image © National Defence

2. Bedford Institute of Oceanography

Science Facility and Coast Guard Base

Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

(Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

Image © Fisheries and Oceans Canada

3. La Citadelle de Québec

Military Base and Official Residence, Québec, Quebec

(National Defence)

Image © Musée Royal 22e Régiment

4. Place du Portage, Phase III

Office Building

Gatineau, Quebec

(Public Services and Procurement Canada)

Image © Public Services and Procurement Canada

5. National Research Council Saskatoon Office

Science and Research Facility

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

(National Research Council)

Image © National Research Council

6. Esquimalt Graving Dock

Marine Infrastructure

Victoria, British Columbia

(Public Services and Procurement Canada)

Image © Public Services and Procurement Canada

| Region | Percentage of floor area |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 10% |

| British Columbia | 9% |

| Manitoba | 5% |

| National Capital Region | 22% |

| New Brunswick | 5% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3% |

| Northwest Territories | 1% |

| Nova Scotia | 6% |

| Nunavut | 1% |

| Ontario | 18% |

| Prince Edward Island | 1% |

| Quebec | 13% |

| Saskatchewan | 3% |

| Yukon | < 1% |

| International | 3% |

The federal real property portfolio is predominantly Crown-owned (90% of the buildings and 80% of the floor area).Footnote 8 Much of the Crown-owned portfolio is special-purpose in nature, ranging from science and technology (for example, laboratories, wind tunnels, hatcheries, observatories) and engineering assets (for example, bridges, roads and highways, wharves, canals, central heating and cooling plants) to security and safety (for example, military bases, armouries, correctional institutions, ports of entry) and parks and heritage assets (for example, national parks, monuments, parliamentary and judicial buildings). Within the federal office portfolio, however, there is a relatively equal distribution between Crown-owned and leased assets – 48% of the floor area is Crown-owned, and 52% is leased.Footnote 9

| National Defence | Public Services and Procurement Canada | Correctional Service Canada | Royal Canadian Mounted Police | Global Affairs Canada | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39% | 31% | 6% | 5% | 3% | 16% |

The five largest custodians of federal real property assets by floor area (m2) are National Defence (DND) (39%), Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) (31%), Correctional Service Canada (CSC) (6%), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) (5%), and Global Affairs Canada (GAC) (3%) (see Figure 9). In total, these five custodians own and manage 84% of the government’s real property portfolio, representing 19 million m2 of the total floor area.

Among the 15 asset classes the Review examined, the security and safety asset class has the largest portfolio, with 38% of the total Government of Canada floor area. This portfolio is followed by the office (28%), housing (12%), and science and technology (11%) asset class portfolios. The Government of Canada also has a sizable engineering asset class portfolio, which includes approximately 20,000 engineering assets (for example, runways, breakwaters, graving docks, seawalls, canals, irrigation systems, and electrical power generation and distribution systems). The engineering asset class portfolio represents nearly 40% of the overall Government of Canada real property portfolio, with an estimated replacement value of $39 billion. Many of these engineering assets are public-facing and of significant importance to the Canadians who use them on a regular basis. The Government of Canada’s portfolio also includes various minor asset classes, including housing, warehousing, commercial and retail, education and training, legislative, judicial, diplomatic, parks and recreation, assembly and cultural, managed land, and health, medical and dental. Despite their relatively small size, these asset classes support the delivery of valuable federal programs (such as representing Canada in the international arena, supporting annual celebrations of Canadian heritage, carrying out Canadian democracy, upholding the rule of law, and delivering critical health care services to Indigenous communities). The 10 minor asset classes, excluding managed land, account for 24.3% of the overall Government of Canada portfolio by floor area.

State of the federal real property portfolio

Federal buildings

Generally, four key performance measures are used in assessing the performance of a real property asset or portfolio: functionality, utilization, physical performance and financial performance.Footnote 10 Using the information collected from custodians on age, condition and deferred maintenance, the Review assessed physical performance of the Government of Canada’s building portfolio. This analysis also provided insight into the functionality of the portfolio, given that as an asset ages and its condition deteriorates, the asset’s ability to support program delivery declines.

| Prior to 1900s | 1900s | 1910s | 1920s | 1930s | 1940s | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000 to present | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over 50 years old | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 6% | 28% | 11% | 11% | - | - | - |

| 25 to 49 years old | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11% | 13% | - |

| Less than 25 years old | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 12% |

The average age of Crown-owned assets is 49 years. Research shows that there are definitive points in the life cycle of a building when the asset’s base systems, envelope and interior space begin to require considerable interventions.Footnote 11 Typically, buildings that are less than 25 years old are associated with low to medium risks of failure of building structure and/or systems. Buildings that are 25 to 49 years old are considered to pose higher risks because many major building components may be reaching the end of their useful life. The highest liability for health and safety risks arising from issues such as system failures, building closures, or interruption to the delivery of programs and services are commonly associated with buildings that are 50 years of age and older.

| Good | Fair | Poor | Critical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of number of buildings | 28% | 54% | 16% | 2% |

| Percentage of floor area | 31% | 46% | 20% | 3% |

For portfolios where assets have been well maintained and have had life-cycle building component upgrades, the age of the asset alone is not a reason for concern. However, in the context of the federal real property portfolio, age becomes an important indicator of condition given the substantial amount of deferred maintenance that has accumulated. Currently, 52% of the Government of Canada’s Crown-owned buildings are 50 years of age or older, meaning that they are in the highest risk category, while 28% are between 25 and 49 years of age, signalling that if necessary investments are not made, these assets will deteriorate prematurely (see Figure 10).

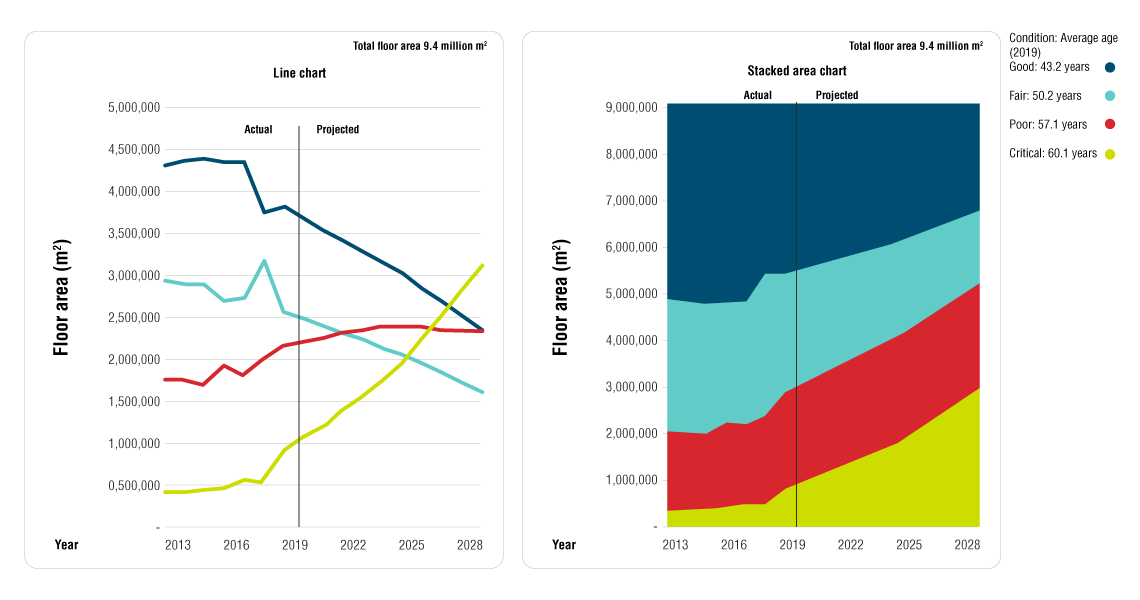

The analysis of the currently available data on the federal real property portfolio shows that there is an inverse relationship between age and condition – as an asset gets older, its condition worsens, resulting in the compounding and accelerated accumulation of deferred maintenance. The analysis of the condition projections developed by the Review shows that, in the next 10 years, more than 50% of the total Government of Canada floor area will deteriorate to poor or critical condition, and the floor area in critical condition will surpass the floor area for each of the other condition categories (see Figure 12).Footnote 12 Such deterioration will significantly erode the ability of these assets to support government programs and will lead to a considerable increase in costs.

Figure 12 - Text version

Figure 12 consists of two graphs: a line graph and a stacked area graph. Both graphs illustrate the data set out in the following table:

| Actual floor area | Projected floor area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2016 | 2019 | 2022 | 2025 | 2028 | |

| Good | 4,361,844 | 4,420,832 | 3,834,961 | 3,447,828 | 3,043,179 | 2,530,846 |

| Fair | 2,951,215 | 2,698,798 | 2,580,226 | 2,327,893 | 2,061,204 | 1,720,149 |

| Poor | 1,755,193 | 1,895,970 | 2,156,928 | 2,297,215 | 2,394,187 | 2,358,770 |

| Critical | 367,269 | 419,921 | 863,406 | 1,362,585 | 1,936,952 | 2,825,756 |

|

Notes |

||||||

As shown in Figure 13, the cost to address deferred maintenance increases significantly for real property assets that are in critical condition – the cost is 12 times higher for science facilities and 5.6 times higher for office buildings – highlighting that it is more expensive to maintain and repair older, inefficient building systems. Based on the models and projections developed by the Review, in collaboration with Statistics Canada, the deferred maintenance of the government’s real property portfolio is estimated to be $20 billion (excluding engineering assets). Given the status quo, this amount is expected to grow by approximately $2 billion per year.Footnote 13

Figure 13: cost to address deferred maintenance

| Good | Fair | Poor | Critical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred maintenance cost per square metre by condition category | 277 | 676 | 906 | 3,211 |

| Good | Fair | Poor | Critical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred maintenance cost per square metre by condition category | 169 | 491 | 472 | 953 |

Federal engineering assets

The current state of the engineering asset class portfolio is similar to the building portfolio, but the information for this asset class is more limited. The Government of Canada did not have an enterprise view of its engineering assets, as this information is currently not captured in the Directory of Federal Real Property. Therefore, the Review developed the first high-level inventory of federal engineering assets.Footnote 14 To facilitate the Review’s analysis, these engineering assets were grouped under five major categories (that is, transportation land, transportation marine, transportation air, waterways, and utilities and services). This grouping was based on other jurisdictional and industry best practice, as well as the unique characteristics of the assets.

Figure 14: Alaska Highway, British Columbia

Like the building portfolio, age is used as an indicator of asset condition or replacement need for engineering assets. However, it is difficult to draw accurate conclusions about the current state of the overall engineering asset portfolio based on the available data on age. Different engineering asset types have different design (expected) lives. For instance, highway bridges, rock breakwaters and large dams have design lives in the range of 75–100 years, whereas the design life of floating wharves is 20–25 years. Design lives can be extended with diligent ongoing maintenance and repair or be shortened by neglect or climate change impacts. Custodians reported that age is a major concern, as aging assets can compromise the integrity of their portfolios in terms of safety and performance.

Condition information was reported for 65% of the reported assets. Custodians cited various reasons for not providing condition information on the rest of the engineering portfolio, such as the information not being collected, information being collected at the local level but not available in a central system, or information being too old to be reliable. The limited level of reporting for condition information is concerning as this information is foundational for identifying needs and prioritizing investments to mitigate risks, such as mission failure. As an industry best practice, the condition assessment of engineering assets is generally done using five condition categories, rather than the four used in building condition assessments. The information collected shows that 9% of the reported assets are in very good condition, 34% are in good condition and 39% are in fair condition, while 13% are in poor condition and 5% are in very poor condition. Although the available data suggests that the overall condition of this asset class is fair to good, the lack of data for 35% of reported engineering assets and the lack of standardized condition assessment processes across the Government of Canada portfolio raise concerns about the integrity of the reported condition data.

Figure 15: Canada Place Building, Edmonton, Alberta

Functionality is critical to understanding how engineering assets are meeting their defined program and service requirements and whether they are delivering value for money. Functionality is generally determined by factors such as how well the custodian adheres to accepted engineering standards; risk and performance reports/criteria; and defined priorities, timelines and reliability requirements. Most custodians routinely measure functionality, although they may not use a formal performance management framework or a centralized system to capture this information. Horizontal assessment of functionality cannot be undertaken given the absence of common performance indicators for functionality across custodians.

Figure 16: St. Andrews Lock and Dam, Lockport, Manitoba

Engineering assets, like buildings, deteriorate over time. The Review developed a model to estimate projected capital and maintenance investment needs for engineering assets over the next 50 years, using the age, condition and replacement cost information reported, as well as typical asset deterioration curves and service lives by asset type. According to this model, in the next 10 years, there will be an investment requirement of approximately $10 billion in maintenance and $8 billion in capital, highlighting a funding pressure of approximately $18 billion for engineering assets.

To conclude, the federal real property portfolio (both buildings and engineering assets) is aging, deferred maintenance costs are increasing, and the condition and functionality of the assets are declining. If no action is taken, the federal real property portfolio will continue to deteriorate progressively. This accelerating deterioration will increase operational, financial, legal and reputational risks and liabilities, and compromise the portfolio’s ability to support federal programs and services and achieve broader government objectives.

Figure 17: Kluane National Park and Reserve, Kluane, Yukon

Root cause analysis

The Review undertook a root cause analysis to understand the underlying causes that have led to the current state of the portfolio. The Review examined the portfolio through an asset class lens and assessed horizontal issues that cut across all the asset classes. The findings show that a number of interconnected, systemic and complex causes have led to the current state, including a lack of profile, leadership and oversight at the enterprise and departmental level; absence of strategic portfolio management; transactional rather than strategic focus in the workforce; volatile and unsustainable funding; unreliable and inconsistent data and unintegrated legacy systems; siloed management practices; and inefficient business processes. Most of the custodians reported an erosion of their real property budgets over time due to increases in operating costs, the general absence of protection against inflation, program growth, and the effects of policy premiums (for example, greening, accessibility). Figure 18 provides a synopsis of the Review’s high-level findings and observations against the backdrop of the horizontal lenses that guided the analysis.

Figure 18: strategic and operational insights

Governance

- Low profile, lack of leadership and oversight at the enterprise and departmental level

- Absence of enterprise-wide view: custodians are managing their portfolios in silos and consider only vertical accountabilities, which means that there is no horizontal integration

- Real property activities are more transactional than strategic

Portfolio management

- Lack of strategic portfolio management, which results in investment decisions being made on a project-by-project basis without contextualization within a broader strategy

- Lack of effective long-term portfolio planning, which leads to challenges in achieving funding sustainability

- Absence of systematic and disciplined asset management practice

Funding sustainability

- Volatile and unsustainable funding; erosion of real property budgets due to inflation and policy premiums

- Increasing deferred maintenance, which is estimated to be $20 billion and is expected to grow by approximately $2 billion annually (excluding engineering assets) given the status quo

- Funding pressure for the engineering assets is estimated to be approximately $18 billion in the next 10 years

Divestiture

- Assets for disposal remain surplus for an average of nine years (923 sites and 23,453 hectares of land are currently surplus)

- A cumbersome disposal process and a lack of enterprise-wide coordination, visibility and planning

- Disposal expertise is unevenly distributed among custodians

Information and information management

- Inconsistent and unreliable data and legacy systems that are not integrated

- No whole-of-government inventory for the federal engineering assets (the data collected shows that engineering assets represent approximately 40% of the overall Government of Canada portfolio, with an estimated replacement value of $39 billion)

- Lack of consistency in measuring and reporting on the performance of the real property portfolio

The Review observed common challenges in a number of other jurisdictions, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, the Province of Ontario and the City of Toronto. These jurisdictions are also struggling with aging and deteriorating portfolios that have significant deferred maintenance backlogs, and are facing challenges in ensuring sustainability of their portfolios, implementing strategic portfolio management, achieving data integrity and enhanced use of data analytics, disposing of their surplus assets, and creating a workforce that is well aligned with the needs of the portfolio. Most of these jurisdictions have initiated transformational change to address the systemic legacy issues of their real property portfolios, and to transform their approach to real property management from an opportunistic savings realization approach to a more proactive approach that considers property as a strategic platform to deliver government’s wider objectives.

Shared path forward: real property transformation

Consistent with other jurisdictional best practice, at the macro level, the Review recommends that the Government of Canada transform the management of its real property, and modernize, right-size and green its real property portfolio to position Canada for the 21st century and beyond. Given the scope and scale of the challenges that the government’s real estate holdings face, the Review recommends undertaking immediate, integrated and systematic actions on multiple fronts to ensure a successful transition from the legacy portfolio and traditional management practice to a modern, right-sized, agile, and financially and environmentally sustainable portfolio, managed with a forward-looking, strategic and citizen-centred perspective. Figure 19 outlines the high-level recommendations of the Review.

Figure 19: high-level review recommendations

Governance

Establish a robust governance and oversight structure to raise the profile of real property, provide leadership, and enhance professional capability

Leveraging

Create an environment in which real property is recognized as a strategic enabler that advances broader socio-economic objectives, becomes a platform for innovation, and is a valued resource for citizens

Portfolio management

Embrace and commit to the implementation of a disciplined and systematic portfolio management regime as a priority

Divestiture

Adopt a new and innovative approach to divestiture by streamlining business processes and consolidating expertise to accelerate disposals and maximize value

Funding sustainability

Develop a new approach to funding sustainability to ensure an affordable and sustainable portfolio in support of program delivery

Information and information management

Real property asset classes

Place data and systems improvement at the forefront, and make business intelligence and data analytics the backbone of real property management

Advance targeted recommendations for each asset class

Given the interdependencies between the multiple causes that led to the current state of the portfolio (for example, aging and deteriorating portfolio, and increasing deferred maintenance backlog in the face of rapidly evolving programs and a changing environment), the government needs to adopt a holistic, phased and multi-faceted approach that will facilitate intentional and mindful actions on a number of fronts. This approach will require sustained commitment, continued leadership and careful execution of a well-thought-out plan, which would be reassessed and adjusted as needed throughout the implementation process. Figure 20 outlines the phases and the expected outcomes of the real property transformation.

As illustrated in Figure 20, the Review has initiated the change management process and has already delivered tangible results. Building on this momentum, the Review’s comprehensive suite of recommendations should be endorsed and implemented with agility, a sense of urgency and speed. Given the significant changes that have been unleashed by the COVID‑19 pandemic, the current context provides a generational opportunity to transform and modernize the federal real property portfolio in the light of future-oriented program direction. It is an opportunity to create a flexible, agile, green and right-sized portfolio for the future, and to re-envision the Government of Canada’s real property portfolio as a strategic platform to achieve broader government objectives (for example, demonstrate government leadership by creating a climate-resilient, accessible and inclusive portfolio that can be leveraged to attract and retain talent, build communities and partnerships, protect the environment, and stimulate the economy).

| Review phase (completed) (2017–20) | Transition phase (2021–23) | Sustainable portfolio (ongoing) |

|---|---|---|

Results achieved:

|

Expected results:

|

Expected results:

|

Immediate foundational actions

-

In this section

- Governance: establish a robust governance and oversight structure and enhance professional capability

- Portfolio management: commit to implementing a disciplined and systematic portfolio management regime

- Funding sustainability: develop a new approach to funding sustainability

- Leveraging: create an environment in which real property is recognized as a strategic enabler

- Divestiture: adopt an innovative and streamlined approach to divestiture

- Information and information management: place data and systems improvement at the forefront, and make business intelligence and data analytics the backbone of real property management

Governance: establish a robust governance and oversight structure and enhance professional capability

The Review’s root cause analysis demonstrates that the decentralized custody model is a contributing factor, but not a primary cause, for the current state of the portfolio. As such, and considering that changes to machinery of government and the resulting resource transfers would require significant investment of time and energy, and could detract from addressing the pressing issues affecting the government’s real property portfolio, the Review does not propose fundamental changes to the custody model at this time. However, to balance the unintended consequences of the decentralized custody model (such as siloed management practices, which result in loss of opportunities for economies of scale and expertise) and to address the lack of central leadership and oversight, the Review recommends the establishment of a robust governance and oversight structure, enhanced accountabilities, and improving the professional capacity of the federal real property workforce.

Key recommendations

- Establish and fund a Real Property Management and Transformation Office as the government’s centre of expertise for real property management as a dedicated, impartial entity to:

- drive real property transformation

- monitor, track and measure the performance of custodians

- facilitate horizontal integration and collaboration

- provide advice to the government on matters related to real property.

- Develop and implement an enhanced accountability framework that includes the following to ensure that accountabilities are effectively discharged: strengthened policy and guidance; enhanced monitoring and reporting; financial incentives and disincentives; and performance evaluation.

- Develop and implement a comprehensive and holistic approach to community‑building, with a view to a “hire-to-retire” employee life-cycle process, to strengthen the federal real property community and enhance its professional capability and strategic capacity.

- As a first step, focus on succession planning for the executive cadre to equip the next generation of strategic real property leaders with market-leading skills and knowledge.

Portfolio management: commit to implementing a disciplined and systematic portfolio management regime

Portfolio management has emerged as the discipline of administering real property throughout its life cycle (that is, planning, acquisition, operations and maintenance, and divestiture), with a view to long-term portfolio sustainability by creating and maintaining a flexible and diverse portfolio and maximizing value across the enterprise. The discipline of portfolio management, also known as mature corporate real estate management, has been adopted as best practice across leading peer jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom, the United States, and New Zealand. It ensures that real property assets are proactively and intentionally managed as strategic resources, taking into consideration the long-term needs of programs and enterprise priorities. Doing so allows for horizontal integration at the enterprise level and overcomes silos across locations, sectors and disciplines, and ultimately leads to an optimized footprint, increased efficiencies, enhanced flexibility and portfolio sustainability.

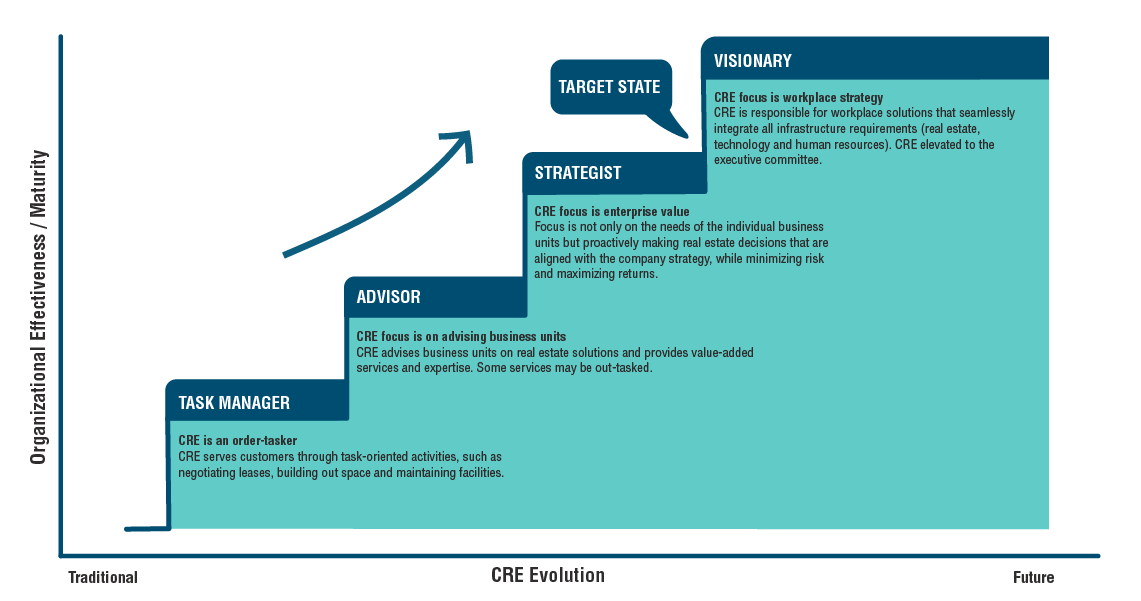

Figure 21: Corporate Real Estate (CRE) Maturity Model

Figure 21 - Text version

Figure 21: Corporate Real Estate (CRE) Maturity Model

Figure 21 illustrates the four stages of organizational effectiveness and maturity for corporate real estate (CRE) organizations. This image has a note that indicates that it is extracted from Deloitte Consulting LLP, Corporate Real Estate Perspectives [PowerPoint slides], p. 6.

The figure shows the stages of task manager, advisor, strategist and visionary as four steps, ascending from left to right, with “task manager” as the bottom step and “visionary” as the highest step. Below this depiction is a scale labelled “CRE evolution,” with “task manager” at the traditional side of the scale (the lowest step, at the left) and “visionary” at the future side of the scale (the highest step, at the right).

Each step is labelled as one of the four stages (task manager, advisor, strategist or visionary). Each step has a short description:

- Task manager (first step): CRE is an order-taker. CRE serves customers through task-oriented activities, such as negotiating leases, building out space and maintaining facilities.

- Advisor (second step): CRE focus on advising business units. CRE advises business units on real estate solutions and provides value-added services and expertise. Some services may be out-tasked.

- Strategist (third step): CRE focus is enterprise value. Focus is not only on the needs of the individual business units but proactively making real estate decisions that are aligned with the company strategy, while minimizing risk and maximizing returns.

- Visionary (fourth step): CRE focus is workplace strategy. CRE is responsible for workplace solutions that seamlessly integrate all infrastructure requirements (real estate, technology and human resources). CRE elevated to the executive committee.

Between the “strategist” and “visionary” steps is a label that reads “target state.”

The Review findings show that strategic portfolio management is not implemented consistently and methodically across custodians, which means that custodians manage their respective portfolios on a transactional or operational basis rather than on the basis of a strategic, integrated and long-term portfolio perspective, leading to short-sighted and inefficient management results. Therefore, implementing a disciplined and systematic portfolio management regime, with embedded monitoring, tracking, measuring and reporting, is a “must do” to improve the management of federal real property.

Figure 22: Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge, Nekaneet First Nation Reserve, Saskatchewan

Key recommendations

- Custodians must develop real property portfolio strategies for their respective departments and agencies, along with implementation plans, and bring these strategies forward for Treasury Board approval. Informed by future program requirements, a changing environment and corporate priorities, the strategy would:

- assess the “as‑is” state and describe the desired state

- identify gaps in resources and finances

- present options to maintain a sustainable and affordable portfolio with an optimized footprint that can support current and future program requirements.

- Develop the first Government of Canada Real Property Portfolio Strategy to provide direction, identify priorities and set performance targets for managing federal real property.

- Develop and implement an asset management framework to enhance life-cycle management.

- Obtain and maintain up-to-date information on asset condition in support of evidence‑based decision‑making.

- Obtain appraisals from the Chief Appraiser of Canada for all federal real property assets to update the replacement value of the federal fixed asset portfolio, as this information is critical for determining the appropriate level of investment in order to achieve a sustainable portfolio.

Funding sustainability: develop a new approach to funding sustainability

Funding sustainability for real property signifies having sufficient funding to operate and maintain an asset or portfolio of assets throughout its life cycle (from acquisition to maintenance to disposal) in a way that its functionality and value are preserved. The custodians identified a lack of sustainable funding and ongoing pressures on operating and maintenance as well as capital budgets as their primary challenge to ensuring portfolio sustainability. The Review findings also show an erosion of real property budgets over time due to increases in operating costs against shrinking reference levels and impacts of policy premiums, the general absence of protection against inflation and program growth, and significant increases in the accumulation of deferred maintenance. Progressive erosion of the federal real property portfolio, the growing deferred maintenance backlog and the current pressures on custodial budgets highlight the need for a new approach to real property funding that will ensure sustainability and affordability of the federal real property portfolio.

Figure 23: Kent Institution, Agassiz, British Columbia

Although an ultimate goal, funding sustainability cannot be achieved quickly and effortlessly under the current conditions, as it requires a certain degree of maturity and strategic management capability on the side of custodians and strengthened governance and oversight structure by the central agencies, both of which are currently lacking. Moreover, despite all efforts, the Review was not able to accurately identify the funding gap for the Government of Canada’s real property portfolio for three main reasons: (1) the absence of departmental portfolio strategies informed by future-oriented program planning, which rendered it difficult to determine what the right-sized real property footprint is for each custodian; (2) lack of a consistent approach to financial reporting, which made it more difficult to accurately identify real property expenditures; and (3) inconsistent and out-of-date asset condition information, which made it challenging to assess the state of the portfolio more accurately. As such, to pave the way to funding sustainability, several fundamental actions need to be taken on other fronts (for example, governance and portfolio management, as outlined above) simultaneously. While the foundation is being built, the Review recommends developing a new approach to funding sustainability.

Key recommendations

- To achieve funding sustainability, adopt a two‑phased approach.

In the first phase, include critical investments in real property over the short term to

- address health and safety issues

- reduce accumulating deferred maintenance

- develop departmental portfolio strategies that align with net-zero and climate-resilient portfolio plans

- support “invest to divest” and greening projects

In the second phase:

- accurately identify the funding gap based on the results of departmental portfolio strategies

- develop and implement a management action plan to achieve a sustainable and affordable portfolio by using various methods, for example:

- identifying customized footprint reduction targets for custodians

- freezing building footprints

- modernizing and right‑sizing the portfolio

- adopting a proactive and accelerated approach to disposal

- achieving net-zero-carbon operations by 2050

- advancing other Greening Government Strategy objectives

- Develop accounting protocols for real property in order to gain accurate information on expenditures at the custodian and enterprise level. Create a unique identifier for each asset to enable linkages between financial and real property information systems.

- Consider the life‑cycle funding requirements of assets as part of any funding for new builds.

Leveraging: create an environment in which real property is recognized as a strategic enabler

The Government of Canada real property portfolio provides a vital network of assets across the country, which, when managed proactively with a citizen-centric view, could become one of the most valuable resources for achieving broader government objectives, as illustrated in Figure 24.

Figure 24: reimagining real property as a strategic platform

Become a platform to fight climate change

Buildings account for 50% of the Government of Canada’s targeted emissions:

- Prioritize investments to achieve net-zero-carbon government operations by 2050

- Prioritize investments in climate resiliency

- Leverage buildings and engineering assets to innovate

- Support clean technology

Build a stronger and sustainable economy

- Contribute to economic growth and create middle-class jobs by investing in Canada’s infrastructure (every $1 billion invested in infrastructure creates 15,000 jobs and contributes $1.6 billion to the economy)

- Leverage the real property portfolio to support regional employment

- Promote small and medium-sized enterprises, Indigenous businesses, and the green economy by modernizing the real property portfolio

Build communities and partnerships

- Explore innovative programming opportunities to allow communities to use federal buildings (for example, open science facilities to communities and schoolchildren)

- Create Wi-Fi hubs in government buildings located in rural, northern and remote communities in order to help these communities access high-speed Internet

- Collaborate with provinces and municipalities to deliver better, faster and more convenient services to citizens

- Unlock land and surplus or underused buildings to support affordable housing and community use

Support modern digital government

- Transform the real property platform to support the digital economy and e government

- Support citizen-centric, accessible and convenient public services

- Provide modern, flexible, barrier-free and smart workplaces to attract and retain talent in the public service

- Enhance real property professionalization and ensure diversity and inclusion in the real property community

Figure 25: Saoyú-ʔehdacho National Historic Site, Northwest Territories

Parks Canada is currently working with over 300 Indigenous groups across the country to strengthen Indigenous connections with traditionally used lands and waters and is collaboratively managing 19 natural and cultural heritage places in its custody with Indigenous communities.

A notable priority area for the Government of Canada is the fight against climate change. Recent years have seen increased recognition of the impacts of climate change, such as extreme weather events and prolonged heat waves in Canada and around the world. These impacts are compounded by the fact that the average land temperature in Canada has increased at a rate twice that of the global average since the mid-20th century. To respond to these challenges, the government has announced an ambitious emissions reduction target – to be net zero by 2050.

The Government of Canada’s environmental footprint is related mainly to its operations. In 2017, the Centre for Greening Government developed and has been leading the implementation of the Greening Government Strategy, which was updated in 2020. Analysis conducted by the Centre for Greening Government indicates that in the 2019–20 fiscal year, federal real property assets generated 50% of the Government of Canada’s targeted greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, the government is in an optimal position to leverage its real property portfolio to demonstrate leadership in climate action both domestically and internationally, and advance its greening agenda by achieving net-zero emissions from federal buildings. The COVID‑19 pandemic has also provided a unique leveraging opportunity for expanding the benefits of a green economic recovery to Canadians. This context presents an opportunity to facilitate strategic green portfolio planning and investment management that simultaneously achieves net-zero emissions and climate resilience in government operations and delivers large-scale, national economic and employment opportunities in support of a green recovery.

Key recommendations

- Use the federal real property portfolio as a strategic enabler to advance corporate priorities (for example, further Indigenous reconciliation, achieve net-zero carbon operations, support climate resilience and sustainable development, ensure accessibility, and drive digital transformation) and expand the portfolio’s benefits to Canadians. Launch projects to showcase the Government of Canada’s leadership by using the federal real property portfolio as a strategic platform.

- Comply with the requirements of the Greening Government Strategy and embed net-zero-carbon and climate-resilience targets in the departmental real property portfolio strategy.

- Produce and maintain a net-zero and climate-resilient real property portfolio plan to determine the most cost-effective way to achieve net-zero and climate-resilient real property operations by 2050.

Divestiture: adopt an innovative and streamlined approach to divestiture

Figure 26: Pleasantville, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador

In 2006, Canada Lands Company acquired the Pleasantville property in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. The 25.9-hectare site is a former American and Canadian military base that was built during the Second World War. The current development concept calls for a primarily residential development, with a mix of housing types, open space, local commercial and recreational opportunities, and a stormwater management system. Phase 1 (the eastern portion of the site) has had new services and roads installed, and several development blocks have been constructed, including an affordable housing project that created 45 units.

Divestiture is one of the key functions of effective asset life-cycle management. The Review findings show that disposal of surplus real property has been a chronic issue due to cumbersome business processes, limited marketability of some of the surplus assets, required investments to remediate properties and address environmental liabilities, and specialized expertise required to effectively conduct stakeholder consultations. There are currently 923 federal sites and 23,453 hectares of land that have been declared surplus. Typically, assets for disposal remain surplus for an average of nine years. Although the residual market value of these surplus assets might be nominal, the cost to maintain them is estimated to be at least $78.1 million annually. The Review highlights that the greatest potential for value realization resides in the active portfolio, as there are underutilized, poorly performing and vacant assets that are not yet declared surplus. Timely and systematic identification of these assets for disposal would provide a significant opportunity to generate greater value from government assets.

Key recommendations

- As a priority action and with urgency, expedite the disposal of surplus properties through a sustained and coordinated program of action, and adopt an innovative approach to the disposal of surplus assets by streamlining business processes and consolidating disposal expertise to accelerate cycle time and maximize value. Canada Lands Company Limited and Public Services and Procurement Canada should explore options to streamline and accelerate disposal processes.

- Recognizing the complexity of the duty to consult, and the need for specialized expertise to undertake such consultations, identify a centre of expertise within the Government of Canada that can provide advice and assistance to custodians in fulfilling their duty to consult.

- Develop and maintain a centralized list of surplus properties that has key performance information, and explore the creation of a publicly accessible web portal to support the surplus property circulation process and become an information centre for underutilized federal real properties and properties that are for sale.

Information and information management: place data and systems improvement at the forefront, and make business intelligence and data analytics the backbone of real property management

Having reliable, up-to-date and accurate information on real property assets, as well as an information management system that facilitates the analysis of this information, is one of the foundational elements of effective portfolio and life-cycle management. Effective information management relies heavily on a central system that is capable of end-to-end asset life-cycle management and tracking, which is subsequently populated by complete and accurate real property information at the enterprise level. Quality information and effective information management is also critical to effective performance measurement and the ability to measure the achievement of strategic goals using defined metrics (for example, key performance indicators).

Figure 27: Edward Drake Building, Ottawa, Ontario

The Directory of Federal Real Property is the federal government’s only central real property information management system, which serves as the touchstone centre of information for custodians and the public. The Review findings demonstrate that there are issues regarding the integrity and consistency of real property data, as the frequency of gathering asset-level information, the leveraging of tracking tools and the quality of information vary considerably across custodians. The analysis of the information reported to the Review demonstrates that custodians use a wide variety of systems to manage real property information. These systems range from the most basic tools to more sophisticated “commercial off-the-shelf” asset management information tools and geographic information systems. These information management systems perform different functions, such as the coordination and management of service delivery, the tracking of maintenance work and leased space, collecting and storing basic real property information, and geospatial analysis. Most custodians use more than one information management system; however, these systems are often not integrated, which means that the use of data often cannot be reconciled or optimized to provide seamless information on the full asset management life cycle, which complicates usability and reporting. It also limits the ability to aggregate information of a common quality and perform cross-organizational comparisons.

Key recommendations

- Improve data integrity and comparability at the enterprise level by:

- developing common definitions and standards for the management of real property information

- having custodians regularly review their real property information in the Directory of Federal Real Property (DFRP) and having the annual DFRP certification exercise signed off at the deputy minister or assistant deputy minister level

- Enhance the information technology infrastructure of the Directory of Federal Real Property to reinforce systems, address urgent risks and ensure sustainability, and potentially include information that is not currently available, such as financials, environmental indicators and engineering assets, as part of reporting requirements.

- Focus on utilizing existing data better by applying new and innovative methods and tools (for example, business intelligence tools) to provide timely and evidence-based information for decision-making. Initiate a process to understand the needs of the real property business to enable longer-term solutions for the management of real property information.

- Develop a real property and performance management strategy that includes horizontal key performance indicators that must be measured by all custodians, and data and performance metrics on the achievement of corporate priorities.

Figure 28: Library and Archives Canada Preservation Centre, Gatineau, Quebec

Conclusion

Figure 29: Daniel J MacDonald Building, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

The Government of Canada owns the largest and most complex real property portfolio in Canada, with 32,000 buildings, 20,000 engineering assets and millions of hectares of land spread from coast to coast to coast, supporting the delivery of invaluable federal programs and services to Canadians. Recognizing the value of real estate as a key enabler of program delivery and the challenges facing this portfolio, the government announced a horizontal review of federal fixed assets in Budget 2017. The Review undertook the most extensive study of the management of federal real property in over 35 years and assessed the portfolio through an asset class lens, while also examining horizontal issues trending across the portfolio.

The Review’s analysis clearly demonstrated that the Government of Canada’s real property portfolio is aging, deferred maintenance costs are increasing, and the condition and functionality of the assets are declining at an accelerated rate. The result is an accelerating decline in the portfolio’s ability to support rapidly evolving program requirements within the context of technological innovation and socio-economic, environmental and demographic changes. If no action is taken, this accelerating deterioration will increase the operational, financial, legal and reputational risks and liabilities of the Government of Canada and compromise the portfolio’s ability to support the delivery of federal programs and services. Thus, the Review highlights that the status quo is no longer an option as it is no longer sustainable. The Review therefore recommends that the government transform how it does business and what it delivers. Recognizing that several interconnected, systemic and complex causes have led to the current state of the portfolio, the Review recommends undertaking immediate, integrated and systematic actions on multiple fronts to achieve a successful transition from the legacy portfolio and traditional management practice to a modern, right-sized, agile and financially and environmentally sustainable portfolio, managed with a forward-looking, strategic and citizen-centred perspective.

Although the Review was launched three years ago, it has never been timelier than now to deliver this comprehensive report on real property management, given the significant changes that the novel COVID‑19 pandemic has unleashed in Canada and around the world, leaving no sector untouched and resulting in the critical task of envisioning a new economy in its wake. The Government of Canada has a generational opportunity to transform real property management and modernize, right-size and green its real property portfolio for current and future generations. There is a new sense of urgency underlying the Review’s recommendations, which can be the catalyst to respond to the reformulation of the government’s priorities, showcase world-class leadership in climate action, deliver large-scale economic and employment opportunities, and navigate the accelerated impacts on the future of work, the workplace, and how government delivers programs and services. The built environment, whether it comprises police detachments, prisons, laboratories, office buildings or other assets, is undergoing a fundamental shift. In this context, agile and strategic long-term planning for the government’s real property portfolio is more crucial than ever. The Review has already initiated the change management process within the federal real property community. With the government’s agreement and commitment to real property transformation and implementation of the Review’s recommendations, the momentum generated by the Review can be further cultivated, and a genuine transformational change can be launched to create a modern, agile, and financially and environmentally sustainable government real estate that benefits all citizens in the 21st century and beyond – government real estate in service of Canadians.

Figure 30: Carleton Martello Tower National Historic Site, Saint John, New Brunswick

For more information about the Horizontal Fixed Asset Review, or to obtain the full report and/or one of the supplementary (asset class) reports, please contact us at: ASAS-SSAA@tbs-sct.gc.ca.

Page details

- Date modified: