Inclusive Official Languages Regulations: A New Approach to Serving Canadians in English and French

On this page

Background

English and French are Canada’s two official languages. They are deeply rooted in our history and at the heart of our identity. In addition, the fact that Canada has two official languages provides a range of individual and shared opportunities for social, economic and cultural advancement.

The Official Languages Act (the Act) gives equal status to English and French in the Government of Canada. The Act sets out obligations for about 200 federal institutions.Footnote 1 In November 2015, the government committed to ensuring that “all federal services are delivered in full compliance with the Act.” In March 2018, as part of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023: Investing in Our Future, the government committed to “rethinking [the] government's offer of services to communities.” The review of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations (the Regulations) is directly aligned with the government’s commitment to official languages.

The road travelled

The British North America Act was adopted in 1867. In section 133 of that act, English and French are established as the official languages of Canada. In 1969, the Act instituted official bilingualism throughout the federal government. The Act required that federal institutions ensure that, under certain conditions, “members of the public can obtain available services from and can communicate with [federal institutions] in both official languages.”

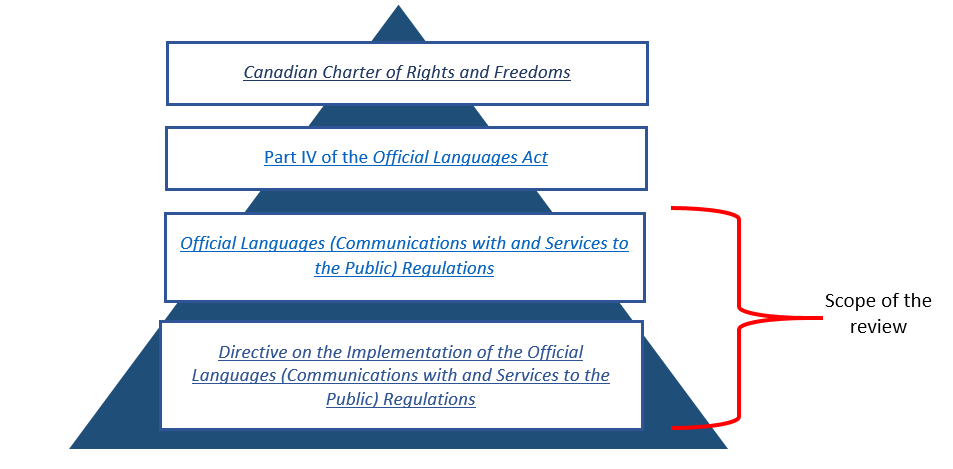

The 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter) and Part IV of the 1988 Act, which has a quasi-constitutional status that has been recognized by Canadian courts, provide more specifically that the public has the right to communicate with federal institutions and to receive services from them in the official language of their choice when the nature of the office justifies it or where there is a significant demand for communications and services in that language.

The Regulations were issued in December 1991 and then progressively came into force from 1992 to 1994. The Regulations gave substance to Part IV of the Act by specifying the circumstances under which the offices of federal institutions have the duty to provide services and communicate in both official languages. The Regulations are a tool to concretely and thoroughly apply certain concepts of the Charter and certain provisions of Part IV of the Act. The regulations specify and define the concepts of significant demand and nature of the office.

The scope of the Regulations

The Regulations apply to all organizations that are subject to the Act. They include federal institutions that are frequently used by Canadians, such as Service Canada centres, post offices and border checkpoints as well as privatized organizations, such as Air CanadaFootnote 2 and airport authorities.Footnote 3 Some 11,300 federal offices and points of service are subject to the Act and the Regulations.

The concept of “office” is broad and refers to any location or means of providing services or information to the public by federal institutions. It includes toll-free telephone numbers, RCMP detachments, train routes or commemorative plaques. It should be noted that not all federal offices must communicate with members of the public and provide them with services in both official languages.

Part IV of the Act stipulates that members of the public in Canada have the right to use English or French when they communicate with:

- the head office or headquarters of federal institutions

- offices located in the National Capital Region

- the offices of an institution that reports directly to Parliament (for example, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada, the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer and the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages)

The regulations set out which of the 11,300 federal offices and points of service in Canada and abroad are required to provide services in both official languages. They are:

- offices located in areas where there is significant demand

- offices whose nature justifies providing bilingual services (for example, embassies and consulates)

- offices that provide services to travellers

25 years of the Regulations

The various provisions of the Regulations ensure that the vast majority of Canadians can receive services from federal institutions in the official language of their choice. The rules are complex because they need to be sensitive to the distribution of official language minority communities across the country and the networks of federal offices. Guided by the Regulations, Canada’s approach to designating the language of service for federal offices is realistic, reasonable and practical. Canada’s approach makes it possible to provide a wide and balanced range of bilingual federal services throughout the country and abroad in a number of areas: employment insurance, pensions, social insurance, taxes, passports, transportation, immigration, border services, postal services and consular services.

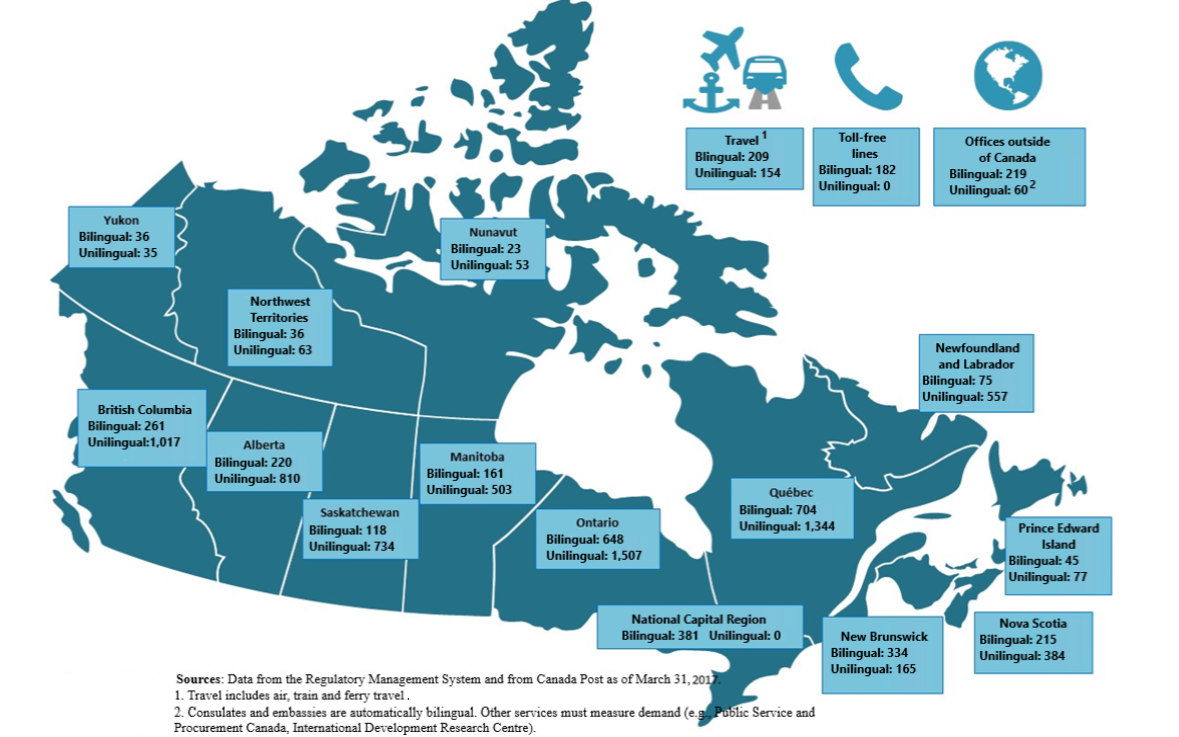

On March 31, 2017, 3,867 of the 11,300 federal offices located in Canada and abroad were required to communicate with and provide services to the public in both official languages. This means that 34% of federal offices were designated bilingual. Federal services in both languages are available in every province and territory, as well as abroad (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Text version

British Columbia: 261 bilingual offices, 1,017 unilingual; Alberta: 220 bilingual offices, 810 unilingual; Saskatchewan: 118 bilingual offices, 734 unilingual; Manitoba: 161 bilingual offices, 503 unilingual; Ontario: 648 bilingual offices, 1,507 unilingual; National Capital Region: 381 bilingual offices, none unilingual; Quebec: 704 bilingual offices, 1,344 unilingual; New Brunswick: 334 bilingual offices, 165 unilingual; Prince Edward Island: 45 bilingual offices, 77 unilingual; Nova Scotia: 215 bilingual offices, 384 unilingual; Newfoundland and Labrador: 75 bilingual offices, 557 unilingual; Yukon: 36 bilingual offices, 35 unilingual; Northwest Territories: 36 bilingual offices, 63 unilingual; Nunavut: 23 bilingual offices, 53 unilingual; Offices outside Canada: 219 bilingual, 60 unilingual (Consulates and embassies are automatically bilingual. Other offices must measure the demand (for example, Public Services and Procurement Canada, International Development Research Centre)); 182 bilingual toll free lines, none are unilingual; Routes: 209 bilingual, 154 unilingual (include air, train and ferry routes). Sources: Data from the Regulatory Management System and from Canada Post as of March 31, 2017.

A timely regulatory review

Since the Regulations were enacted in 1991, they have been amended only once. In 2006, an order from the Federal Court in the Doucet v. Canada case required the government to review part of the Regulations, so that the needs of the travelling public who use a section of the Trans-Canada Highway could be properly considered.

Apart from this amendment, no substantive review of the Regulations had ever been conducted in 25 years of implementation. However, many changes have taken place since the Regulations took effect, including:

- an increase in the demographic and linguistic diversity of Canadian society

- significant changes to how services are delivered by federal institutions (field officers, self-service kiosks, services provided online)

- technological advances with the advent of the Internet and mobile devices

Many stakeholders in Canadian society, including official language minority communities, parliamentarians and the Commissioner of Official Languages, have asked the government to review the Regulations. Parliamentarians introduced billsFootnote 4 to amend Part IV the Act in order to affect the application of the Regulations. For many years, the Commissioner of Official Languages had expressed their wish to see the Regulations amended. In May 2018, the Commissioner tabled a special reportFootnote 5 in Parliament to influence the review of the Regulations.

Statistics Canada’s Language Projections for Canada, 2011 to 2036, which was published in January 2017, notes that, despite an upward trend in the number of speakers, the percentage of the population able to speak French could decrease from 2011 to 2036 and so could the proportion of Francophones outside Quebec. Under the calculation method set out in the 1991 Regulations, certain areas that have minority language populations that may experience relative demographic decline could be at risk of losing access to federal services in both official languages.

Review of the Regulations announced by ministers Scott Brison and Mélanie Joly

On November 17, 2016, the Honourable Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board, and the Honourable Mélanie Joly, Minister of Canadian Heritage, jointly announced that the Government of Canada would initiate a review of the Regulations. The main objective of this review was to modernize the Regulations in order to take into account the current socio-demographic and technological context, correct certain irregularities that had occurred over time, and adjust the Regulations to foreseeable social, demographic and technological trends. The announcement of the review was well received by most stakeholders.

Figure 2 - Text version

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Part IV of the Official Languages Act

Scope of the review

Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations

Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations

A moratorium to protect the bilingual designation of offices during the review

When the review was announced in November 2016, the language designation of some 250 bilingual offices was in the process of being reassessed,Footnote 6 and there was a risk that they might be designated unilingual. The bilingual designation of those offices was protected through a moratorium established by the President of the Treasury Board.

The moratorium was established by adding subsection 6.2.3 to the Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations on November 20, 2016. Subsection 6.2.3 provides for those offices to continue to communicate with members of the public in both official languages during the regulatory review.

The moratorium was well received by many stakeholders as it ensured that official language minority communities would continue to have access to services in their language during the regulatory review.

Extensive consultations across Canada

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) began country-wide consultations as soon as the review was announced. In total, TBS met 150 stakeholders representing some 60 organizations and interest groups in all 10 provinces and three territories. Various consultation mechanisms were used to ensure that a broad range of stakeholders and the general public had opportunities to contribute to the review. These mechanisms are presented in the following paragraphs.

- Starting in November 2016, working groups were created, so that regular briefings and discussions could take place with the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN), the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne (FCFA), the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages and key federal institutions that have a particular role in implementing the Regulations.

- From May 2017 to April 2018, TBS also conducted regional consultations with over 100 key stakeholders in all provinces and territories, including:

- representatives from official language minority organizations

- representatives from organizations that promote Canada’s linguistic duality

- representatives responsible for official language issues in provincial and territorial governments

- regional representatives of the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- various interested parties and experts (academics, legal experts and experts on official languages issues)

In most cases, consultations were conducted on site. They allowed TBS to appreciate the impact of the Regulations in regions and communities, and to take stock of shortcomings and best practices. Appendix B of this report lists the organizations that were consulted.

- In June 2017, the President of the Treasury Board created the Experts’ Advisory Group (EAG). The group provided the President with additional external input and recommendations on the review. The EAG was composed of Senator Raymonde Gagné, former Senator Claudette Tardif, former Commissioner of Official Languages Graham Fraser and Dialogue New Brunswick co-chair Mirelle Cyr. TBS met with the EAG four times: in June and November 2017, and in February and May 2018. The information sessions with the EAG were open to all parliamentarians. During two of the information sessions, representatives from Canadian Heritage and Statistics Canada participated in the discussions.

- From April 30 to July 8, 2018, the general public was invited to contribute to the regulatory review through an online consultation on Canada.ca. Canadians were asked to send their experiences with and suggestions for the Regulations to TBS. More than 1,500 people made their voices heard.

- On October 24, 2018, the Government of Canada tabled draft Regulations Amending the Official Languages Regulations in Parliament. Following the tabling, a press conference, briefings and additional meetings were held with key stakeholders and federal institutions.

Finally, a period of publication of the draft amended Regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I began on January 12, 2019 and closed on May 30, 2019. This allowed for further feedback on the Regulations to be gathered.

TBS thanks all those who participated in the consultations.

Regulatory issues and proposals

-

In this section

- Key points

- I. Increasing the offer of federal services in both official languages for all Canadians

- II. Reviewing and extending federal services in both official languages

- Tabling of the amended Regulations in Parliament and publication in the Canada Gazette, Part I

- III. A beginning rather than an end

Key points

A wealth of diverse opinions and comments were expressed during the consultations. Participants were able to identify issues and challenges that they felt were key to the review of the Regulations. Repeatedly, they expressed a desire for a more inclusive definition of significant demand. In addition, they emphasized the importance of considering the vitality of communities and asked that qualitative criteria be included when determining the language designation of federal offices. Other concerns included the concept of key services and placing points of service closer to communities. Participants were also concerned about maintaining bilingual services in places where the demographic weight of the minority community may be declining relative to the majority community, even though the community’s size in absolute terms is growing or remains stable.

Twelve key themes were raised during the consultations. While most themes are being addressed in the proposed regulatory changes, some require further exploration or non-regulatory initiatives.

I. Increasing the offer of federal services in both official languages for all Canadians

Theme 1: better anticipating the language preferences of Canadians

Anticipating official language preference when people visit federal offices is not a simple task. The consultations conducted by TBS showed that some Canadians, particularly those who are part of a minority community, believe that by using the “first official language spoken” (FOLS) variable, the federal government underestimates the number of citizens who wish to receive services in the minority official language.

For many, the method of determining significant demand must be more inclusive. As an Atlantic Canadian said, “My spouse’s mother tongue is English, but he is bilingual and usually speaks French at home and in public. But the government’s calculations do not take this into account.” TBS worked with Statistics Canada on an approach that would reflect new realities, such as mixed English-French households, the increasing number of allophone immigrants and the popularity of French immersion schooling, in order to better anticipate demand for services in the minority official language.

Under the new Regulations, if the minority official language is your mother tongue or if you use the minority official language mainly or regularly at home, then you are counted as part of the anticipated demand for that minority official language at federal offices (see Appendix A).

| Number of people who may demand federal services in English in Quebec | Number of people who may demand federal services in French outside Quebec | |

|---|---|---|

| Past method (FOLS) | 1,058,250 | 1,007,565 |

| New method | 1,479,535 | 1,371,590 |

| Change | + 421,285 | + 364,025 |

Theme 2: taking into consideration the vitality of communities

According to the 1991 Regulations, TBS does not need to take into account the vitality of Anglophone and Francophone minority communities when designating points of service as bilingual. Only quantitative characteristics are considered when determining access to services in the minority language.

A large number of people consulted by TBS consider this approach to be outdated. A participant from British Columbia pointed out, “Why is the Service Canada centre in my area designated unilingual English when there is a French-language school nearby?” Based on all available information, TBS and Canadian Heritage determined that the presence of a minority language school is the best indicator of the vitality of an official language minority community (see Table 2). The inclusion of vitality and the use of the school criterion to gauge vitality mean that federal offices that have a minority-language school in their service area must offer bilingual services.

| Proportion of official language minority community populations residing within 25 km of… | Anglophones in Quebec | Francophones outside Quebec |

|---|---|---|

| a minority language school | 97.3% | 96.0% |

| a minority community development organization | 90.3% | 81.7% |

| a minority community cultural organization | 93.9% | 84.9% |

Theme 3: demographic protection for official language minority communities

The language designation of federal offices is based, in many cases, on the relative demographic weight of the official language minority communities that these offices serve. For example, the Regulations provide that a federal institution must offer bilingual services to the public when the official language minority community of the province, territory or region where this institution has points of service represents a certain percentage (generally 5%) of the total population of the province, territory or region.

Many stakeholders pointed out that this rule may have adverse effects on minority communities because some of these communities are growing at a lower rate than the official language majority population around them. For example, by 2036, the overall proportion of people outside Quebec who speak French as their first official language could decrease slightly, from 3.9% to 3.6%.Footnote 8

During the consultations, the FCFA proposed that a decrease in the proportion of Francophones below the 5% threshold in a given area should not have an impact on the language designation of federal offices, given that, in many cases, the number of Francophones is staying the same or increasing. For its part, the QCGN also proposed that an official language minority community whose relative weight is decreasing, but whose population is stable or increasing in absolute numbers, should continue to have access to bilingual services. Such an approach, they argued, would ensure that communities are not unduly affected by the growth of majority populations.

The new Regulations will be sensitive to situations like these. A federal office will remain bilingual when the official language minority population that it serves has remained the same or has increased, even if its proportion of the general population has declined.

Theme 4: modernizing and expanding the list of key services

Under the Regulations, certain services are referred to as “key services” and are more readily provided in both official languages because they are particularly important. The majority of participants in the consultations indicated that the concept of key services should be maintained, but that the list of services is outdated and too short. For example, they felt that passport services should be included.

Participants noted that “the use of names from a quarter of a century ago makes it difficult to understand the list of key services that are currently provided to the public. For example, the 1991 Regulations set out that the services of an office of the Secretary of State must be provided in both languages, but this institution ceased to exist in 1993.”

To meet the needs of Canadians, the list of key services has now been modernized and significantly expanded to include new key services. For example, all services currently provided by Service Canada offices, including passport application services, will become key services. To promote the economic and social development of official language minority communities, services provided by the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) and by the various regional economic development agencies (RDAs) will also be designated as key services. People who visit the offices of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA), the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor), the Canada Economic Development Agency for Quebec Regions (CED), the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario (FedDev Ontario), the Federal Economic Development Initiative for Northern Ontario (FedNor) and Western Economic Diversification Canada (WD) will be served in the language of their choice at a greater number of offices.

| Key Services in the 2019 Regulations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Key services listed in the 1991 Regulations | Updated names of all key services listed in the 1991 Regulations | New key services added to the list (2019) |

| Services related to the income security programs that fall under the jurisdiction of the Department of National Health and Welfare | Services related to income and employment security provided by a Service Canada access centre (which falls under Employment and Social Development Canada) | All services provided by Service Canada as well as all passport offices |

| Services provided by an employment centre under Employment and Immigration Canada | ||

| Services provided by a post office | Services provided by a post office | |

| Services provided by an office of the Department of National Revenue (Taxation) | Services provided by an office of the Canada Revenue Agency | Services provided by a regional economic development agency (ACOA, CED, CanNor, FedDev Ontario, FedNor, WD) |

| Services provided by an office of the Department of the Secretary of State of Canada | Services provided by an office of Canadian Heritage | |

| Services provided by an office of the Public Service Commission | Services provided by an office of the Public Service Commission | Services provided by the Business Development Bank of Canada |

| Services provided by a detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police | Services provided by a detachment of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police | |

II. Reviewing and extending federal services in both official languages

Theme 5: linguistic duality nationally and internationally

Under the modified Regulations, all airports and train stations located in provincial or territorial capitals will be designated bilingual, including any federal offices located inside those airports and train stations. As a result, the Charlottetown airport, and the points of service operated by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority at that airport, will be designated bilingual.Footnote 9

In addition, the approximately 60 offices of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada located in embassies and consulates will be designated bilingual in the new Regulations. This designation enhances the image that Canada projects around the world to those who wish to live, study or do business here.

Theme 6: consulting communities on the location of bilingual offices

In cities and regions where there is a significant minority language population and where a federal institution has several offices that provide the same service, some of those offices are designated bilingual. The proportion of bilingual points of service depends on the demographic weight of the minority community. For example, when minority language speakers account for 25% of the population in a given area, a quarter of the offices that provide the same service must be bilingual. Under the Regulations, this is called the “proportionality rule.”

Once the number of bilingual offices in a city or region has been determined, the federal institution must choose which ones will be designated bilingual. The 1991 Regulations required the institution to consider the distribution of the minority population. The Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations added a requirement for institutions to consult the minority population on the location of bilingual offices. Because the requirement to consult is contained in the directive and not in the Regulations, some participants felt that the requirement did not have the desired impact. In the words of a participant from Manitoba, “Nobody really knows why a department that is required to provide bilingual services in a particular service area chose to have its bilingual office on the other side of the river, far from the area where Francophones are located and where they never go.”

In order to improve on this situation, the modified Regulations will require that the input of minority language communities be considered by federal institutions when they determine the location of bilingual offices under the proportionality rule.

Theme 7: using technology without sacrificing in-person services

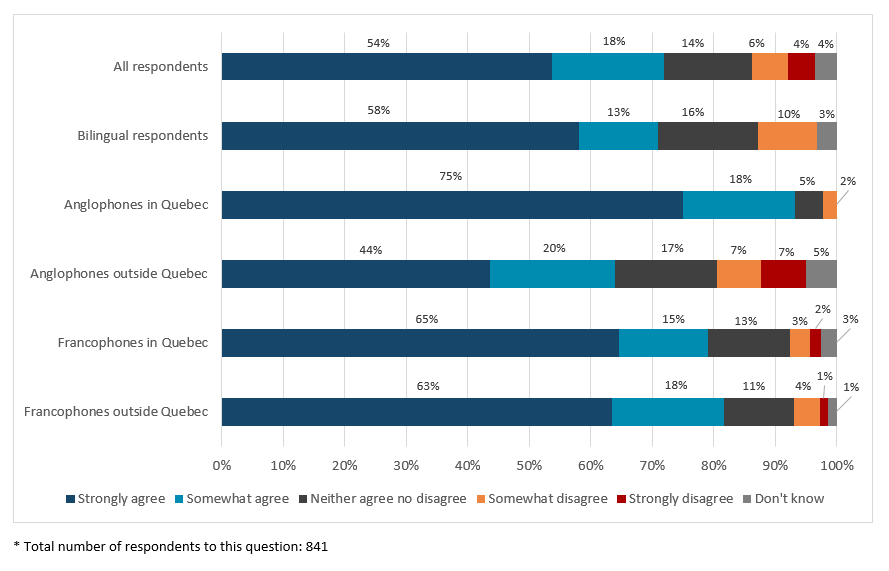

The use of information and communication technologies was viewed positively by participants, as long as it was understood that such use would not lead to the removal of services that minority communities currently receive in person. TBS’s online survey showed that respondents who are part of an official language minority community do support greater use of digital technology by the Government of Canada. 93% of respondents to the survey who indicated they were English-speaking in Quebec and 81% of respondents who indicated they were Francophones outside of Quebec support the idea of federal institutions using information and communication technologies to provide more services in both official languages (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text version

All respondents: 54%: strongly agree; 18%: somewhat agree; 14%: neither agree nor disagree; 6%: somewhat disagree; 4%: strongly disagree; 4%: don’t know.

Bilingual respondents: 58%: strongly agree; 13%: somewhat agree; 16%: neither agree nor disagree; 10% somewhat disagree; 0%: strongly disagree; 3%: don’t know.

Anglophones in Quebec: 75%: strongly agree; 18%: somewhat agree; 5%: neither agree nor disagree; 2 %: somewhat disagree; 0 %: strongly disagree; 0%: don’t know.

Anglophones outside Quebec: 44%: strongly agree; 20%: somewhat agree; 17%: neither agree nor disagree; 7%: somewhat disagree; 7%: strongly disagree; 5%: don’t know.

Francophones in Quebec: 65%: strongly agree; 15%: somewhat agree; 13%: neither agree nor disagree; 3%: somewhat disagree; 2%: strongly disagree; 3%: don’t know.

Francophones outside Quebec: 63 %: strongly agree; 18%: somewhat agree; 11%: neither agree nor disagree; 4%: somewhat disagree; 1%: strongly disagree; 1%: don’t know.

* Total number of respondents to this question: 841

Following the example of toll-free telephone lines, which have been designated bilingual since the 1990s, the modified Regulations will ensure that services provided by videoconferencing are also automatically designated bilingual. In addition, the Government of Canada will use digital technology to enhance the delivery of federal services in English and French (see theme 12).

Theme 8: an analysis of the Regulations every 10 years

The world is changing, and it is important for the Regulations to change with it. Many stakeholders, including representatives from the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages and official language minority communities, were adamant that the Regulations must be reviewed more frequently than every 25 years. That is why a new provision has been added to the Regulations. The provision requires that the Regulations be analyzed every 10 years and that the results be tabled in Parliament.

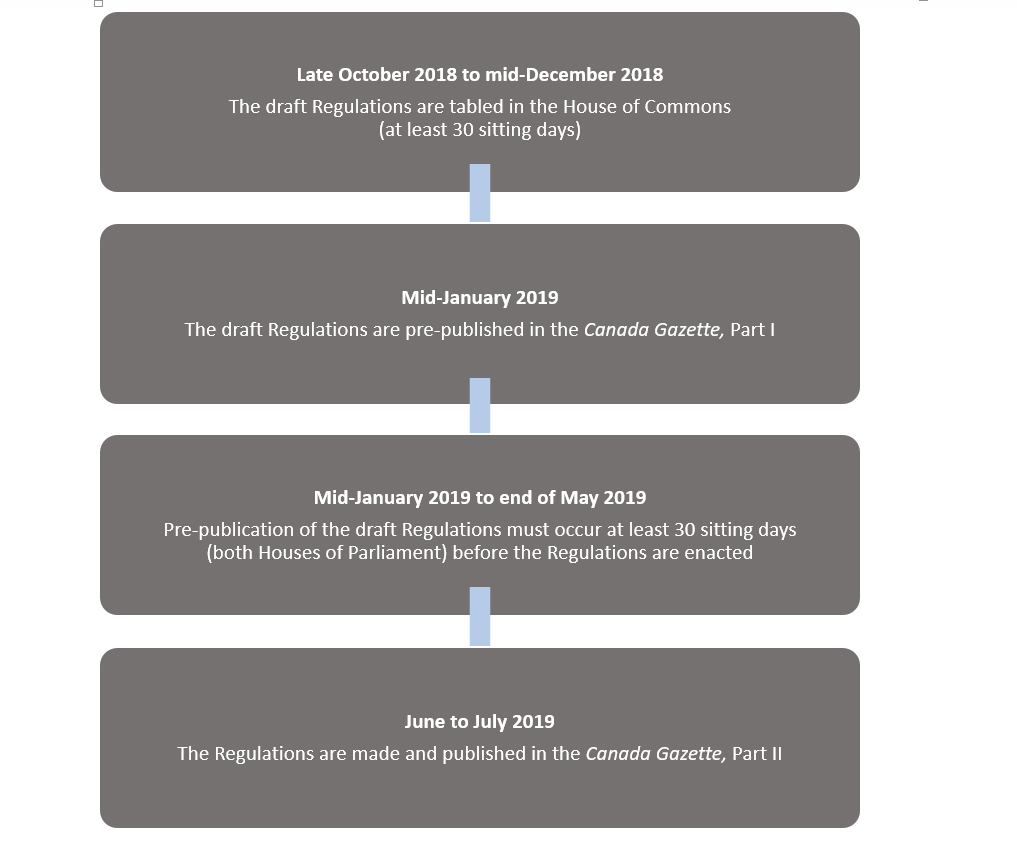

Tabling of the amended Regulations in Parliament and publication in the Canada Gazette, Part I

On October 24, 2018, the government of Canada tabled in Parliament the draft amended Regulations and on January 12, 2019, they were published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, for review and comment. The proposed regulatory amendments offered responses and solutions to the eight previously mentioned themes. Stakeholders and the public had also the opportunity to provide further comments and submissions on the proposed amendments to the Regulations between January 12 and May 30, 2019. During this period, TBS received half a dozen briefs and memoirs and had the chance to exchange orally or in writing with many stakeholders and interested persons. Further adjustments to the Regulations were then made.

Theme 9: protecting and improving access to services regardless of community size

Some stakeholders, such as the Commissioner of Official Languages, cited the importance of further improving the demographic protection of bilingual offices in census metropolitan areas. The scope of the demographic protection set out in the Regulations will be expanded to apply to all linguistic communities, regardless of their size, whether they are in rural or urban areas. Stakeholders also noted the importance of services for smaller and remote communities. A rule was added to improve access to bilingual services, notably for key services, in small communities that have a high proportion of minority language speakers.

Theme 10: regularizing certain implementation issues

Stakeholders showed that the Regulations occasionally, in specific cases, resulted in application issues. The review of the Regulations will resolve some of these issues. For example, for certain federal offices providing services to the public, the provisions of the Regulations require the office to measure the demand in both official languages (this is the case notably for border crossings, airports, train stations). This could lead to abnormal results: recently 2 offices were designated unilingual in English in Quebec and one office unilingual in French in New Brunswick. An amendment to the Regulations will now ensure that federal services to the public be always available, at a minimum, in French in Quebec and in English in other Canadian provinces.

Another example of these anomalies seen over time is that of Entry Island in Quebec. Respondents noted that 90% of the population of the island are English-speaking, but the only post office on the island is required to provide unilingual services in French only. A rule was added to the Regulations so that such cases be resolved in the future.

III. A beginning rather than an end

Federal institutions will need time to prepare for the new provisions in the Regulations. As such, the new provisions will take effect progressively. Most of the new provisions will be implemented in 2022, after Statistics Canada publishes the results of the “languages” component of the 2021 Census.

The review of the Regulations will also serve as a springboard for adopting complementary measures to increase and improve bilingual services. Priority will be given to defining and testing more effective ways to encourage the public to exercise their right to request federal services in the official language of their choice. The Act requires that institutions ensure systematic “active offer” of their services. For example, employees must always remind citizens, through a verbal greeting such as “Hello, bonjour,” that they can use English or French at a particular point of service.

The consultations revealed that quite often Canadians who are part of an official language minority community do not insist on being served in their preferred official language. They may not insist because:

- they do not know that service in their preferred language is available

- they fear they will be a burden

- they do not want to be the odd one out

- because they instinctively speak the language of the majority when they go to federal offices

Finally, some issues were raised that could not be addressed through the new Regulations despite their importance. That is the case for themes 11 and 12. However, as the regulatory review is a beginning rather than an end in itself, these themes are explored below.

Theme 11: collaboration between all levels of government to improve bilingual services

During the consultations, TBS met with representatives of provincial and territorial governments to discuss challenges, best practices and possible improvements to the delivery of government services in both official languages. In July 2018, TBS was invited to engage with provincial and territorial governments at a meeting of the Intergovernmental Network on the Canadian Francophonie in Whitehorse during the annual Ministerial Conference on the Canadian Francophonie.

The consultations clearly showed that citizens expect greater collaboration between governments and wish to see more bilingual service centres where people can pay municipal taxes, obtain a provincial driver’s licence and apply for a passport in their preferred official language. To make these centres a reality, governments were encouraged to work toward new partnerships and projects to better provide bilingual services.

Theme 12: taking advantage of digital technology

Digital government may enable citizens, including members of official language minority communities, to obtain services faster and more easily. In March 2018, Canadian Heritage and TBS organized a hackathon in Moncton to promote the development of applications that provide information about activities, services and jobs that are available in the minority official language in a given area. Other digital tools, such as an online application to help Canadians learn English and French, are also planned. Promising technologies, such as artificial intelligence, and more traditional approaches, such as online social networks, can help reinforce Canada’s linguistic duality by offering more services in both official languages. However, the consultations revealed that for many Canadians in rural areas or for those who are less comfortable with new technologies, the use of new technologies can also be a source of concern. Some indicated that they feared losing in-person, citizen-centred services if the government moves too quickly toward delivering services electronically.

Conclusion

In 2016, the Government of Canada committed to modernizing the official languages Regulations to better reflect the realities of contemporary Canadian society. To achieve this, broad consultations were held and key proposals were considered and are now an integral part of the new regulatory framework. Over time, over 700 federal offices will become bilingual and the inclusion of a vitality criterion will mean that 97% of Canadians who live in an official language minority community have access to federal services in their preferred official language. These proposed enhancements are proof that Canada’s linguistic duality continues as a strong foundation and as a source of inspiration. Canada’s regulatory framework for communicating with and serving Canadians in both official languages is being renewed so that it is aligned with the needs of Canadians in the 21st century.

Figure 4 - Text version

Late October 2018 to mid-December 2018

The draft Regulations are tabled in the House of Commons (at least 30 sitting days)

Mid-January 2019

The draft Regulations are pre-published in the Canada Gazette, Part I

Mid-January 2019 to end of May 2019

Pre-publication of the draft Regulations must occur at least 30 sitting days (both Houses of Parliament) before the Regulations are enacted

June to July 2019

The Regulations are made and published in the Canada Gazette, Part II

| Phase | Coming into force | Provision |

|---|---|---|

| I | Registration of the Regulations (Summer 2019) |

|

| II | One year after the registration of the Regulations (June 2020) |

|

| III | Publication of the 2021 Census data (anticipated: summer/ fall 2022) |

|

| IV | One year after the publication of the 2021 Census data (anticipated: fall 2023 – winter 2024) |

|

Appendix A: new calculation method to estimate demand for services in the minority language

Table A1: the new calculation method to estimate demand for service in the minority language

The example in the table below uses English as the minority official language.

| Census Question | Response and impact on the estimate of demand for a minority official language |

|---|---|

| Question 1: What is your mother tongue? | If English is indicated, then English is counted as a part of the estimated demand for service in English. |

| Question 2: What is the main language that you speak at home? | If English is indicated, then English is counted as a part of the estimated demand for service in English. |

| Question 3: What is the language that you regularly used at home? | If English is indicated, then English is counted as a part of the estimated demand for service in English. |

| If English is not indicated in the response of any of these questions, the person is not included in the estimated potential demand for English. | |

Table A2: the number of peopletable A2 note * included in the 2019 calculation method compared to the number of people included in the 1991 method

| 1991 method (FOLS) | New method (2019) | Difference | Percentage increase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 1,058,250 | 1,479,535 | 421,285 | 40% |

| Canada outside Quebec | 1,007,565 | 1,371,590 | 364,025 | 36% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2,095 | 5,865 | 3,770 | 180% |

| Prince Edward Island | 4,810 | 7,690 | 2,880 | 60% |

| Nova Scotia | 30,330 | 45,765 | 15,435 | 51% |

| New Brunswick | 235,700 | 260,785 | 25,085 | 11% |

| Ontario | 542,385 | 743,880 | 201,495 | 37% |

| Manitoba | 41,365 | 60,705 | 19,340 | 47% |

| Saskatchewan | 14,285 | 25,910 | 11,625 | 81% |

| Alberta | 71,365 | 110,975 | 39,610 | 56% |

| British Columbia | 62,195 | 105,515 | 43,320 | 70% |

| Yukon | 1,485 | 2,145 | 660 | 44% |

| Northwest Territories | 1,075 | 1,695 | 620 | 58% |

| Nunavut | 475 | 660 | 185 | 39% |

| Total Canada | 2,065,815 | 2,851,125 | 785,310 | 38% |

Table A2 Notes

|

||||

Appendix B: list of organizations consulted

-

In this section

- Anglophone minority organizations in Quebec

- Francophone minority organizations outside Quebec

- Groups and organizations that promote linguistic duality

- The Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Organizations and federal institutions

- Representatives of provincial and territorial governments

- Other organizations

Anglophone minority organizations in Quebec

- Coasters Association

- Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation (CEDEC)

- Community Health and Social Services Network (CHSSN)

- English Community Organization of Lanaudière

- Heritage Lower Saint Lawrence

- Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN)

- Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN)

- Townshippers’ Association

- Voice of English-Speaking Quebec (VEQ)

Francophone minority organizations outside Quebec

- Assemblée communautaire fransaskoise (ACF)

- Assemblée de la francophonie de l’Ontario (AFO)

- Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta (ACFA)

- Association des francophones du Nunavut (AFN)

- Association franco-yukonnaise (AFY)

- Conseil jeunesse provincial de la Nouvelle-Écosse (CJPNE)

- Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FANE)

- Fédération de la jeunesse canadienne française (FJCF)

- Fédération des associations de juristes d’expression française de common law inc. (FAJEF)

- Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (FCFA)

- Fédération des francophones de la Colombie-Britannique (FFCB)

- Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et Labrador (FFTNL)

- Fédération des jeunes francophones du Nouveau-Brunswick (FJFNB)

- Fédération des parents francophones de la Colombie-Britannique (FPFCB)

- Fédération franco-ténoise (FFT)

- Fondation franco-albertaine (FFA)

- Jeunesse Acadienne et Francophone de l’ïle-du-Prince-Édouard (JAFLIPE)

- Mairie de Petit-Rocher (New Brunswick)

- Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité Canada (RDÉE)

- Société de développement économique de la Colombie-Britannique (SDECB)

- Société de l’Acadie du Nouveau-Brunswick (SANB)

- Société de la francophonie manitobaine (SFM)

- Société francophone de Maillardville (British Columbia)

- Société nationale de l’Acadie (SNA)

- Société Saint-Thomas-d’Aquin (SSTA)

Groups and organizations that promote linguistic duality

- Association canadienne des professionnels de l’immersion (ACPI)

- Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers (CASLT)

- Canadian Parents for French (CPF)

- French for the Future

- The University of Ottawa’s Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute (OLBI)

The Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories and Yukon region

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Atlantic region

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Head office

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Manitoba and Saskatchewan

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Ontario region

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages: Quebec and Nunavut region

Organizations and federal institutions

- Air Canada

- Business Development Bank of Canada

- Canada Post

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Canadian Border Services Agency

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Canadian Heritage

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Correctional Service Canada

- Department of Justice Canada

- Employment and Social Development Canada (including Service Canada)

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Farm Credit Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Marine Atlantic Inc.

- National Defence

- NAV CANADA

- Parks Canada

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- Regina Airport Authority

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Transport Canada

- VIA Rail Canada Inc.

Representatives of provincial and territorial governments

- Government of Alberta: Francophone Secretariat

- Government of British Columbia: Francophone Affairs Program

- Government of Manitoba: Francophone Affairs Secretariat

- Government of New Brunswick: Canadian Francophonie and Official Languages

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador: Office of French Services

- Government of Nova Scotia: Acadian Affairs and Francophonie

- Government of Nunavut: Culture and Heritage

- Government of Ontario: Office of Francophone Affairs

- Government of Prince Edward Island: Acadian and Francophone Affairs Secretariat

- Government of Quebec: Secretariat for relations with English-speaking Quebecers

- Government of Saskatchewan: Francophone Affairs

- Government of the Northwest Territories: Francophone Affairs Secretariat

- Government of the Yukon: French Language Services Directorate

Other organizations

- Canadian Bar Association – French Speaking Common Law Members Section

- Centre canadien de recherche sur les francophonies en milieu minoritaire, Cité universitaire francophone, University of Regina

- Centre francophone de Toronto

- Institut canadien de recherche sur les minorités linguistiques (ICRML), Université de Moncton

- International Observatory on Language Rights

- La Cité universitaire francophone, University of Regina

- Office of Francophone and Francophile Affairs (OFFA), Simon Fraser University

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages for New Brunswick

- Office of the French Language Services Commissioner of Ontario

- Université de Saint-Boniface