Planting the right tree in the right place for a better tomorrow

The 2 Billion Trees (2BT) program supports organizations in planting trees to tackle the dual crises of biodiversity loss and climate change. A biodiverse forest refers to the variety of all life living within it, including the species of trees, plants, animals, and microorganisms in the soil. Biodiversity also refers to other elements of the forest such as the genetic variety within a certain speciesFootnote 1, the mixture of trees of different ages, and differences in the ecosystems they inhabit.

The State of Canada’s Forests Annual Report provides additional details on the biodiversity of Canada’s forests. It demonstrates that biodiversity improves a forest’s resilience to climate change and helps ensure that forests remain healthy for future generationsFootnote 2.

Canada’s 369 million hectares of forest is home to about 140 native tree species, as well as a vast variety of plants, insects, fungi, birds, mosses, lichens, and more. Of the over 400 bird species that breed in Canada, about one third depend on forests to survive.

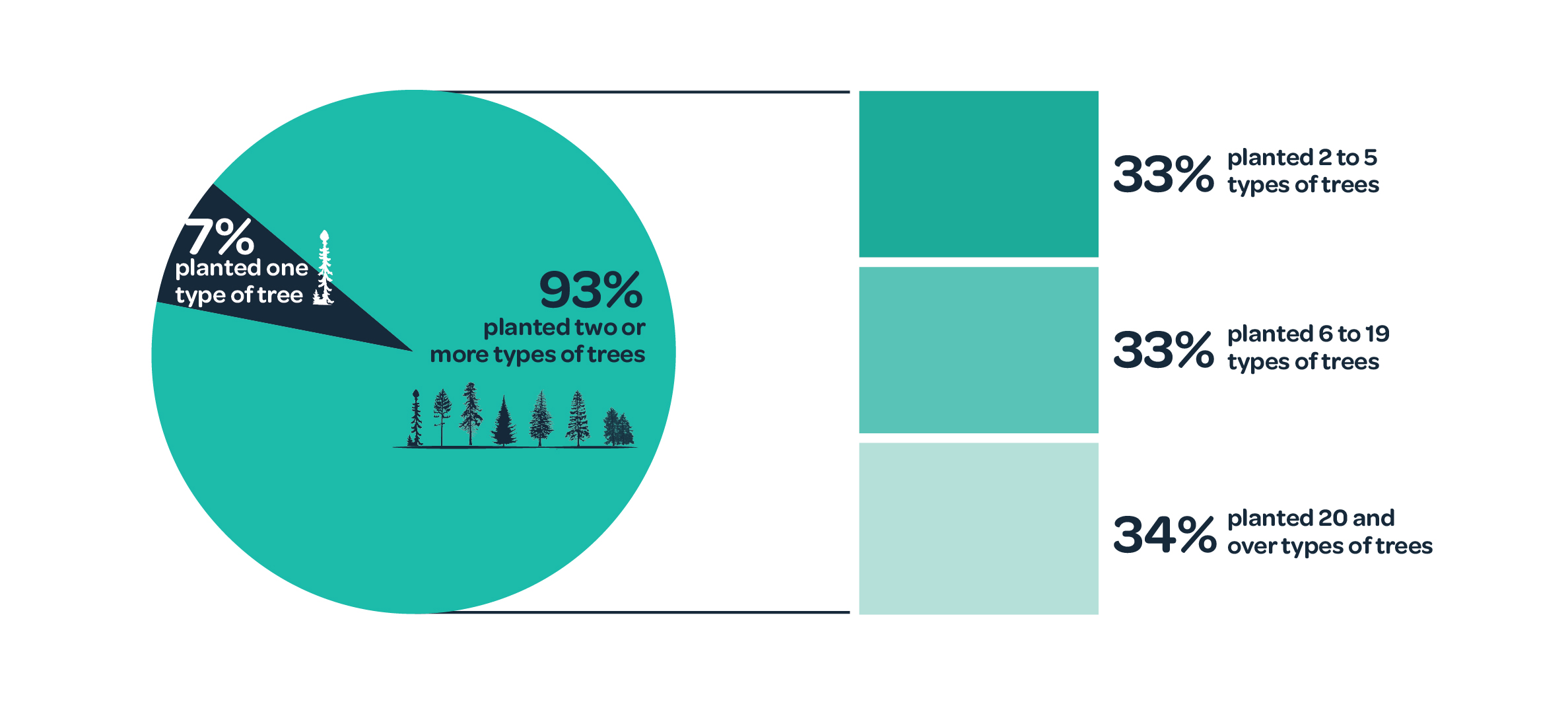

Since 2021, 2BT-funded projects have planted over 300 species at more than 8,200 sites across Canada. 93% of these projects planted more than 2 types of trees (see image below).

Types of trees planted by 2BT-funded projects

The graph is based on 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024 tree planting activities data received and compiled by May 2025.

Text version

The pie chart represents the diversity of trees planted by 2BT funded projects. 7% of projects planted only one type of tree, and 93% of projects planted 2 or more types of trees. A vertical stacked bar chart displays more detail about the projects that planted 2 or more types of trees. Of the 93% of projects that planted 2 or more types of trees, 33% planted 2 to 5 types of trees, 33% planted 6 to 19 types of trees, and 34% planted 20 or more types of trees.

How shrubs support our forests

To plant trees with biodiversity in mind, it is often considered best practice to ensure that a mixture of shrubs, trees and plants are included. While shrubs planted as part of a 2BT funded project are not counted towards the two billion trees goal, the program supports planting them as they provide a number of benefits for our forests, including:

- supporting tree survival and health

- increasing forest resilience by preventing the establishment or re-establishment of invasive species

- preventing soil erosion

- providing habitat and food sources for wildlife

- enhancing urban wildlife corridors

- capturing and storing carbon and pollution

- providing human co-benefits such as visual and sound buffers and cleaner air

Trees and shrubs are both woody plants, plants that produce wood and have a hard stem. There is no standard reference that all experts use to distinguish trees from shrubs. Classifying them as a tree or a shrub can vary depending on their location and different growing conditions.

Natural Resources Canada uses science-based data and sources to differentiate between shrubs and trees when totalling trees planted under the program. The 2BT program has adopted the following definitionsFootnote 3:

- A shrub is shorter than 4.5 metres and normally has several small stems that may stand upright or lay close to the ground

- A tree is taller than 4.5 metres and is typically any woody plant

Text version

The 2 photographs are examples of how shrubs support trees to grow stronger and provide a more biodiverse ecosystem. The first image shows grasses, shrubs and trees growing together. The second image shows a forest with a variety of species in varying states of changing leaf colours in autumn.

Due to the benefits that shrubs provide trees, the 2BT program supports costs for planting shrubs, provided that the shrubs do not outnumber the trees planted. For shrubs to be eligible for project funding, experts that assess the 2BT projects evaluate whether the shrubs:

- support the survival and health of the trees planted by the applicant, and/or

- are native species and an essential component of habitat restoration objectives

Forests in constant change

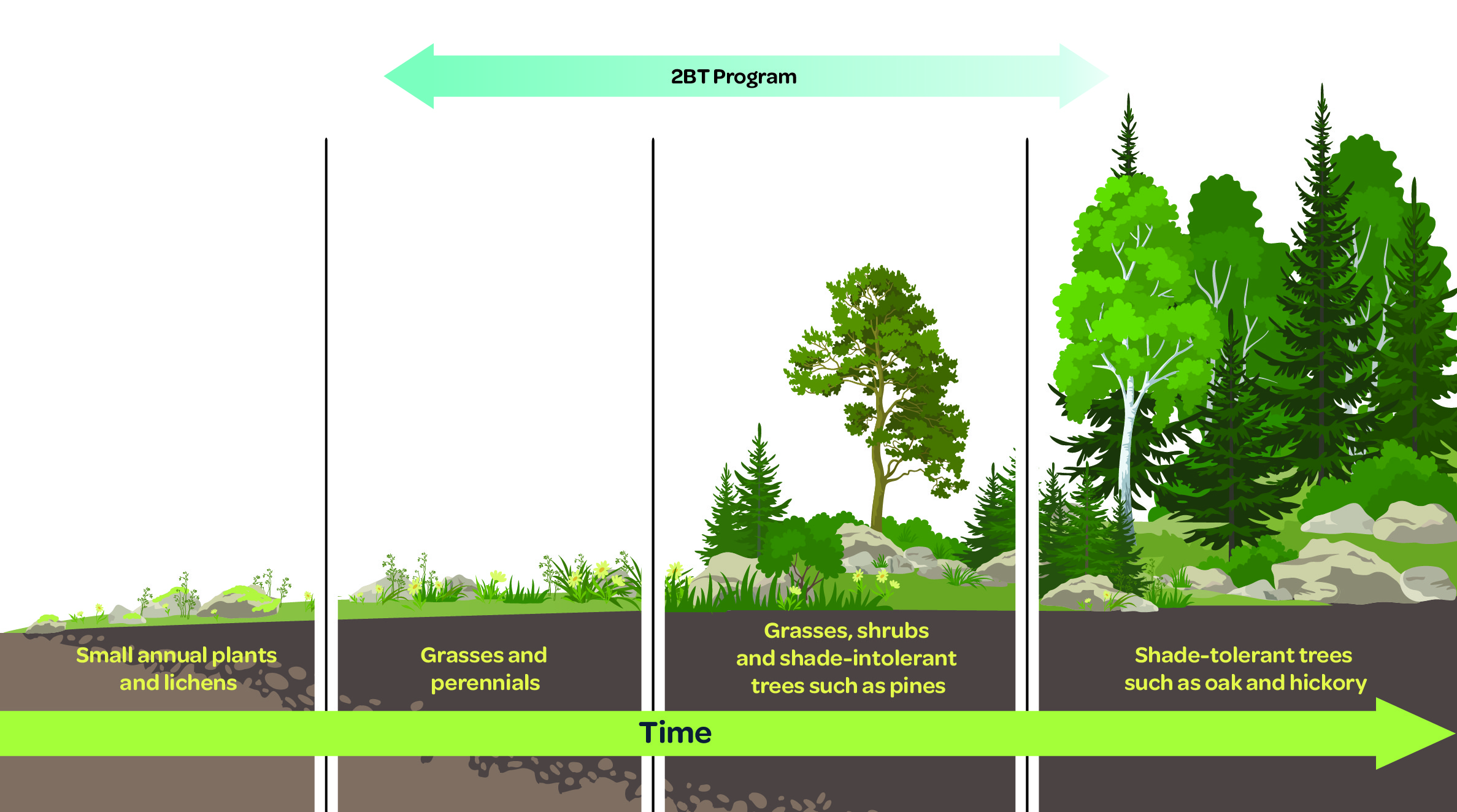

Forest succession is the gradual transition of one community of plants to another, or a predictable, sequential change of forest tree species over time due to changing environmental conditions.

A forest growth cycle follows several stages, going from a young forest to a mature forest, and then to an old growth forest. Not every forest reaches the final stage of old growth. Natural disturbances, such as fire or insects, often disrupt the cycle, resulting in a new cycle beginning before the old one is complete.

Planting trees today for the forest of tomorrow

Text version

The image illustrates how the succession process can change an ecosystem over time. It shows the same place changing from small annual plants and lichens to grasses and perennials. The next transition is to grasses, shrubs, and shade-intolerant trees such as pines, which is followed by shade-tolerant trees such as oak and hickory. A double-ended arrow at the top shows that the 2BT program largely supports planting in the grasses, shrubs, and shade-intolerant trees stage, but does include some projects in the grasses and perennials stage, and also extends slightly into the shade-tolerant trees stage.

Good forest management requires an understanding of:

- the environmental requirements of each tree species to survive, grow, and reproduce (for example, climate, soil, terrain)

- which plants could be placed near each other to grow well together

- the fact that “natural seedlings” will join the planted trees

Different advantages for different species

When forests are left undisturbed, they can expand on their own and mature over time, restoring natural diversity.

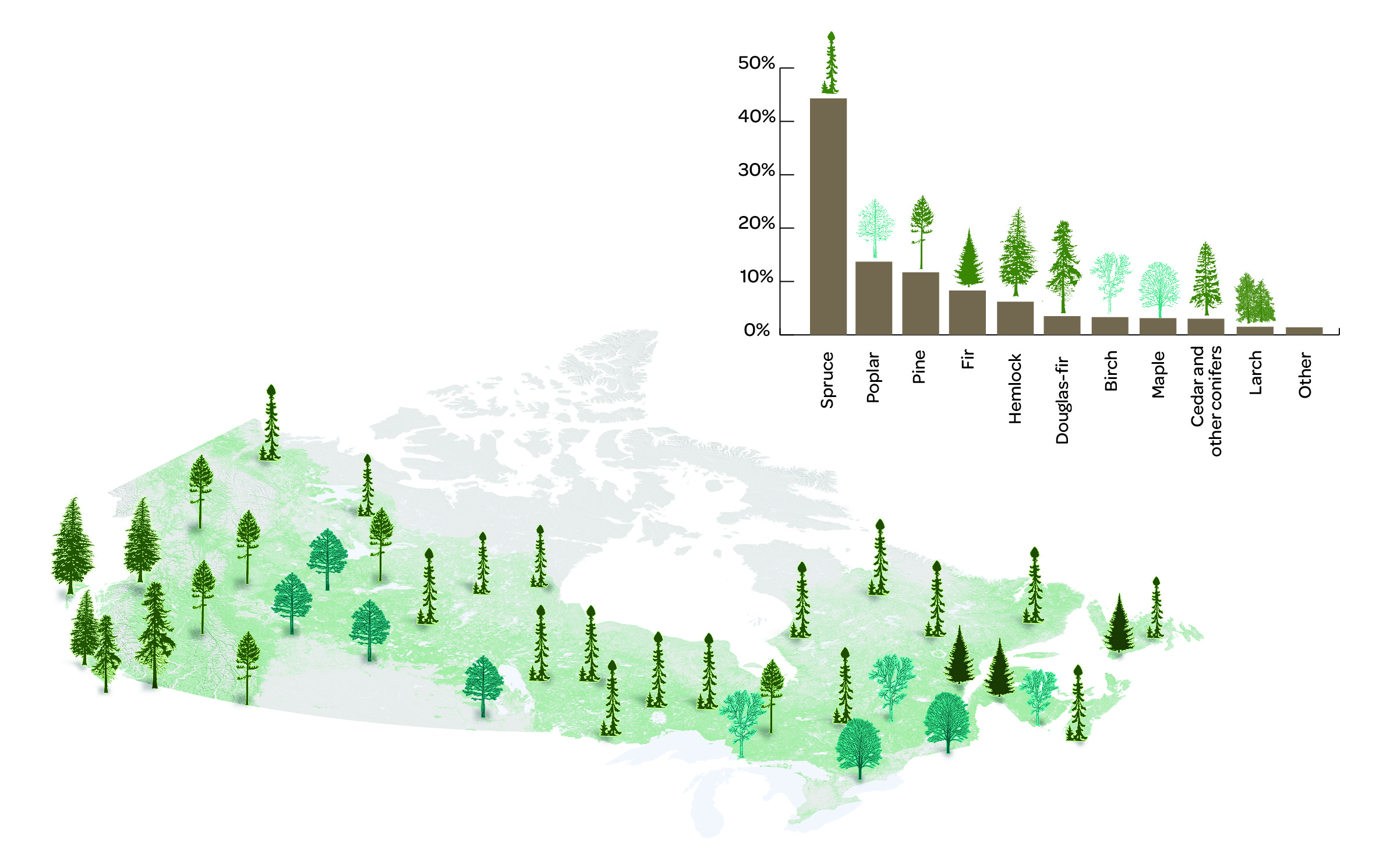

Natural monocultures, where one major species is naturally predominant, are common in nature. Overall, Canada’s forests, while diverse on a large scale, are dominated by 10 species, many of which occur in smaller natural monoculture forest stands. Given Canada’s cold climate, it is not surprising that spruce trees—adapted for drought tolerance and growth in extreme conditions —make up nearly half of all trees in Canada.

Canada’s forests by species

Text version

The image is a map of Canada and a graph of the volume of tree species in Canada beside it. The graph shows the following species volumes:

- Spruce: 44.3%

- Poplar: 13.7%

- Pine: 11.7%

- Fir: 8.3%

- Hemlock: 6.2%

- Douglas-fir: 3.5%

- Birch: 3.3%

- Maple: 3.1%

- Cedar and other conifers: 3%

- Larch: 1.5%

- Others: 1.4%

The map shows the distribution of trees across Canada with the matching tree symbols from the graph. Conifer trees are shown in green and hardwood trees are shown in blue. This shows the most common tree in each region, demonstrating the wide range of spruce and the distribution of conifer and hardwood tree species.

A forest has many ecosystems that provide different conditions for different species of trees to grow. Although Canada’s boreal forests have relatively low tree species diversity, these species naturally thrive and are highly adaptable due to factors such as genetic diversity and large population sizes.

Sometimes, forests need a little help to maintain their diversity. Assisted migration is when humans help a species move to a more suited environment or habitat. Humans transfer the seeds from one location to another outside the species’ usual habitat. Assisted migration is used for conservation goals (for example, to save a species) and to maintain the health and growth of forests.

Good forest management takes current and future growing conditions into account to ensure healthy forests in the future. Planting multiple tree species to achieve high biodiversity is not always a good practice if those trees are not appropriate for that particular region. The experts who assess 2BT program projects consider this important criterion when evaluating the species planted in a project.

In doing so, the “right” species will lead to the development of the “right” forest, as they encourage advantageous conditions for the growth of other plants and wildlife over time.

Forests for Canadians

Another goal of the 2BT program is to achieve human well-being benefits through tree planting. The psychological benefits linked to trees and nature are well established:

- reduction of anxiety, depression, and negative emotionsFootnote 4,Footnote 5,Footnote 6

- relaxationFootnote 7

- enhanced social relationshipsFootnote 8,Footnote 9

- sense of communityFootnote 10,Footnote 11

- and well-beingFootnote 12

Treed green spaces, including forests, provide aesthetic, environmental, recreational, social, and health benefits. In terms of direct experience with natural settings, even a brief interaction with a forest ecosystem increases well-beingFootnote 13. By supporting tree planting initiatives, the 2BT program is helping to increase the well-being of Canadians across the country.