Evaluation of Canada 150 2015-16 to 2017-18

Evaluation Services Directorate

August 20, 2020

On this page

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program overview

- 3. Approach and methodology

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Lessons Learned and best practices

- Annex A: evaluation framework

- Annex B: bibliography

Alternate format

Evaluation of Canada 150 2015-16 to 2017-18 [PDF version - 1.83 MB]

List of tables

- Table 1: evaluation questions by core issue

- Table 2: distribution of key informant category

- Table 3: sources of evidence, by case study

- Table 4: celebrate Canada events attendance and TV viewers in 2017

- Table 5: Canada 150 event funding: number of applications (for all activities)

- Table 6: community-driven and Signature approved projects by priority area

- Table 7: CFC’S Community Fund for Canada's 150th

- Table 8: public opinion of Government involvement in Canada 150: % of respondents who strongly or somewhat agreed to the statements

- Table 9: number of major, Signature and Community-driven projects/events funded by the Canada 150 Fund per region from 2015-16 to 2017-18

- Table 10: volunteer participation by event type

- Table 11: percentage of residents indicating they have participated in or volunteered for at least one Canada 150 event, activity, or initiative

- Table 12: television and social media viewership for selected large-scale Canada 150 celebrations and commemorations

- Table 13: approximate number of people who participated in funded projects (as reported in survey of funding recipients, question 14)

- Table 14: how funded projects contributed to a sustained sense of pride in Canada

- Table 15: number of non-resident travellers entering Canada, annually

- Table 16: type of tangible legacy your project led or contributed to (from funding recipient survey, Q26)

- Table 17: nature of unanticipated impacts (funding recipient survey, Q24)

- Table 18: how projects brought Canadians together (from funding recipient survey, Q11)

- Table 19: overtime for 2015-16 to 2017-18

- Table 20: paid overtime for 2015-16 to 2017-18

- Table 21: budgeted versus actual spending for Canada 150 FS, fiscal years 2014-15 to 2018-19

- Table 22: Community-driven project funding (including Skating Day): requested versus recommended and approved ($ 000)

- Table 23: Signature initiatives: requested versus recommended and approved ($ 000)

- Table 24: Major project funding (including Acadian Day): requested versus recommended and approved ($ 000)

- Table 25: Canada 150 Vote 5 allocated and approved project funds, 2015-16 to 2017-18 ($ 000)

List of figures

- Figure 1: Canada 150 Governance

- Figure 2: “to what extent do you believe that the Canada 150 activities have promoted integrating Canada’s linguistic duality in events?” number and percentage of respondents

- Figure 3: "to what extent did your project focus on environmental stewardship?” number and percentage of respondents

- Figure 4: "to what extent did your project focus on bringing Canadians together to mark and celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation?" number and percentage of respondents

- Figure 5: number of major, Signature and Community-driven projects/events funded by the Canada 150 Fund per region from 2015-16 to 2017-18

- Figure 6: POR results on awareness and communications from June 2016 to July 2017

- Figure 7: contribution of Canada 150 to sense of pride in Canada

- Figure 8: trend in employment generated by tourism and tourism expend

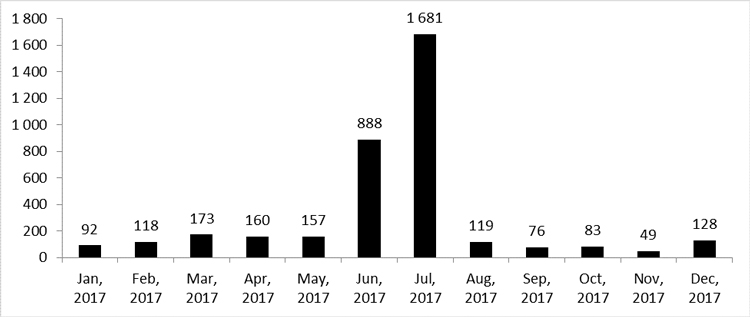

- Figure 9: monthly social media reach of Canada 150 (in millions)

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- C3

- Canada Coast to Coast to Coast

- CCP

- Celebrations and Commemoration Program

- CFC

- Community Foundations of Canada

- CIOB

- Chief Information Officer Branch

- CIP

- Community Infrastructure Program

- DM

- Deputy Minister

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Reports

- DP

- Departmental Plans

- DRR

- Departmental Results Reports

- FCM

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities

- FPT

- Federal, Provincial, and Territorial

- FS

- Federal Secretariat

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- GCIMS

- Grants and Contributions Information Management System

- ICC

- Interdepartmental Committee on Commemoration

- INAC

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- MECCE

- Major Event, Commemoration and Capital Experience

- NCR

- National Capital Region

- OCOL

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- OGD

- Other Government Departments

- OLMC

- Official Language Minority Community

- PCH

- Canadian Heritage

- PNR

- Prairie and Northern Region

- POR

- Public Opinion Research

- RPP

- Reports on Plans and Priorities

- RVNQ

- Rendez-vous naval de Québec

- TIAC

- Tourism Industry Association of Canada

- TRC

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Executive summary

Program description

In 2017, the Government of Canada marked the 150th anniversary of Confederation with a year-long celebration from coast to coast to coast. As the lead of this horizontal initiative, Canadian Heritage (PCH) was responsible for coordinating the efforts of Canada 150 for the federal government, as well as for engaging federal agencies and institutions, and the private and not-for-profit sectors to foster strategic partnerships and manage branding. PCH housed the Federal Secretariat (FS), which served as the official authoritative source for national Canada 150-related information and celebrations, and also served as the primary coordinating body of the initiative with the support of other PCH programs. A networked governance model, with horizontal decision-making and accountability structures, was used to interact with the large number of stakeholders. The Special Projects Team of the Celebration and Commemoration Program (CCP), and regional offices, were responsible for the administration of the Canada 150 Fund, including approving the three types of projects supported (Signature initiatives, Major Events and Community-driven projects) and managing contribution agreements. The four priority areas of the Fund were: diversity and inclusion; supporting efforts toward national reconciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians; engaging and inspiring youth; and our environment.

Evaluation approach and methodology

The scope of the evaluation included the approximately $210 million in investments through the Canada 150 initiative, and a review of the activities and funding of the FS (approximately $10 million). It covered the duration of the initiative from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2018.

Multiple lines of evidence were used to address the evaluation questions, including a document and administrative data review, key informant interviews, a survey of partners and funding recipients, three case studies, and an analysis of media coverage.

Evaluation findings and conclusions

Relevance

It was considered appropriate for the federal government to recognize and support Canada’s sesquicentennial, and the initiative was clearly aligned with departmental outcomes and federal government priorities, roles, and responsibilities. With a few exceptions, PCH Canada 150 activities were relevant to Canadians.

Most of Canada 150 activities and events were delivered in an inclusive way, and aligned with the four government policy priority areas. All four priorities were addressed, with “diversity” being the most prevalent and “our environment” being the least prevalent among PCH funding recipients. Recipients of the Community Foundations of Canada’s (CFC) Community Fund for Canada’s 150th targeted youth and cultural diversity most frequently.

Canada 150 projects and events sought to bring Canadians together. PCH officials and funding recipients focused heavily on this objective. By January 2018, 70% of respondents to a public opinion survey indicated that they had participated in Canada 150 activities, and levels of volunteering were also high. However, there were some gaps in the data on attendance at certain events, which makes it difficult to estimate total participation.

Effectiveness – Achievement of expected outcomes

A variety of projects of different sizes and foci were offered to Canadians in hundreds of communities across all provinces and territories. This includes 720 projects funded through the Canada 150 Fund, in addition to projects funded through the CFC’s Community Fund for Canada’s 150th, and the micro-granting portion of Skating Day.

Interest in the Canada 150 Fund was high, and activities deemed worthwhile by Fund recipients, including for creating or strengthening partnerships. Among the unexpected outcomes that were associated with Canada 150: the development of new partnerships; and the development of capacity in various organizations — both funding recipients, and micro-granting organizations. Along with many successful projects promoting reconciliation, some Indigenous people and others focused on the branding of Canada 150 mostly as a celebration, considering Canada’s difficult history.

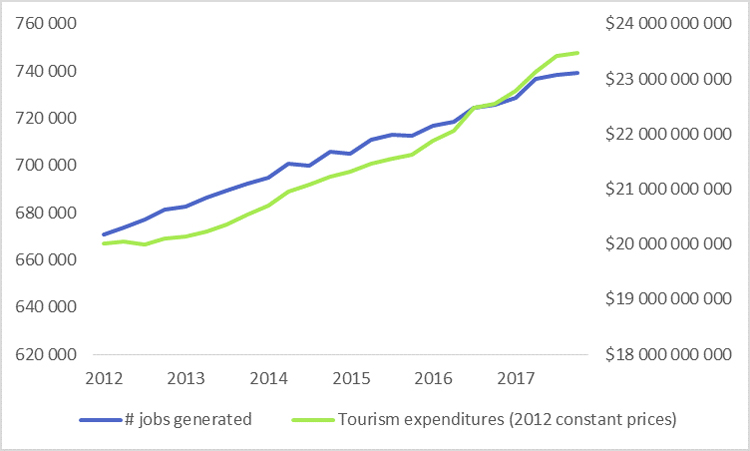

There is evidence to suggest that Canada 150 contributed to the increase in tourism in Canada in 2017 particularly as Canada was named as a top vacation destination for 2017 in The New York Times, Lonely Planet, Travel & Leisure, Condé Nast Traveler, and National Geographic Traveler. Additionally, Canada 150 investment in arts and culture, and in infrastructure projects likely provided some measure of positive economic impact. As recipients of funding did not have to undertake economic impact studies on their individual projects, evidence is limited, and the relative size of Canada 150’s economic impact cannot be measured.

Many projects included a legacy component, though they were overall smaller and fewer than anticipated due to delays. The largest lasting impacts were public infrastructure projects,Footnote 1 though cultural legacy projects were the most common.

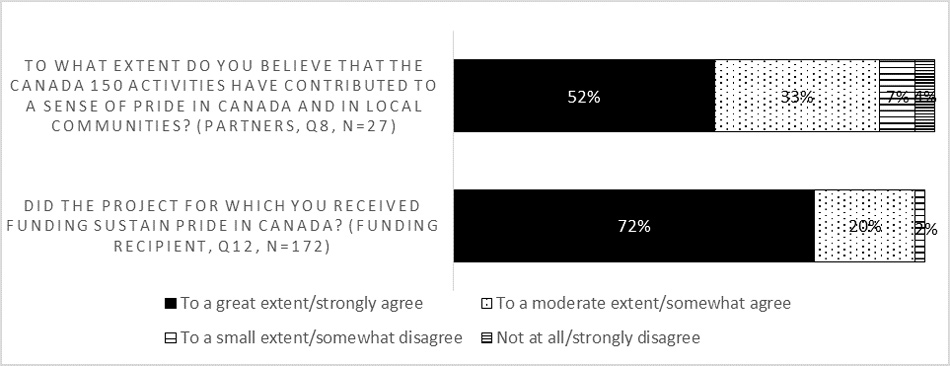

Most evidence demonstrated that the initiative contributed to a sustained sense of pride. For example, 85% of respondents to the partner survey and 92% of respondents to the funding recipient survey reported that Canada 150 activities contributed to a sense of pride.

Efficiency

Total actual spending for the initiative was lower than planned, and senior managers and officials within PCH indicated that the initiative was very cost-effective. The participation of federal departments and agencies from their existing resources, and the requirement for cost-sharing of Canada 150 Fund projects (multiple funders), were both aspects that were considered cost-effective. Partners and stakeholders agree that the Canada 150 initiative was well planned and efficiently delivered, and that the FS was efficient and responsive, but there could conceivably have been more coordination with provinces, territories, and other potential partners across the country.

Internally, earlier planning would have facilitated delivery. Additional resources within PCH would have helped manage the workload and reduce overtime for staff, and a better distribution of workload between headquarters and regional offices would likely have even further improved efficiency.

Effectiveness of design and delivery

The level of adherence to service standards was very high for the timely processing of applications relative to the Canada 150 Fund. On average, 86% of notifications of funding decisions were received within the service standard, although only 74.5% of applications received notice of the funding decision within the standard in 2015-16, largely due to the pause occasioned by the federal election. As for satisfaction with delivery, satisfaction was high at both ends — for PCH senior managers and recipients.

The Canada 150 launch date may have compressed the demand, which included a high number of first-time applicants who needed support and had an effect on the resources for the Federal Secretariat. A longer timeline, from planning to implementation, would have also likely improved delivery.

The application and review process with regard to community-driven projects could have been more streamlined, including by delegating Ministerial authority to Directors General and Regional Executive Directors for decision on smaller grants and contributions (under $75,000 for most programs in 2016). Regional PCH officials indicated they occasionally struggled with program delivery. They reported a lack of support and communication from PCH headquarters, and insufficient resources to adequately deal with the volume of applications and projects.

The Communications Strategy led to significant partnerships and, along with paid advertising, resulting in a social media outreach of nearly four billion people. However, the Canada 150 delivery model for communications services was identified as an issue.

Effectiveness of Federal Secretariat oversight and coordination

Documents indicated extensive and ongoing coordination, strategic planning, information sharing, and dialogue between the FS or PCH programs and external partners and stakeholders, and partners and stakeholders expressed satisfaction with the collaboration and communication. In addition, PCH officials, partners, and stakeholders were largely satisfied with the types of tools that were provided to them.

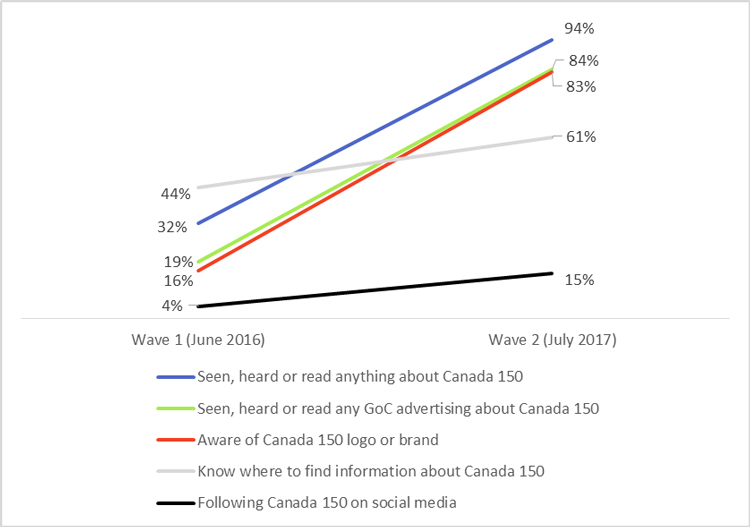

The marketing strategy was multi-pronged, and included a presence at high visibility events and locations; partnerships with large, high visibility organizations; and orchestrating several visual media campaigns, mainly for the Web and social media. The branding strategy achieved high visibility. By January 2018, three out of four Canadians surveyed reported having seen the Canada 150 logo or brand. There was a high level of agreement among key informants that these marketing and outreach activities of PCH and the FS were effective.

The various governance bodies were largely found to support efficient program delivery and the achievement of intended outcomes. The Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) committee was cited as the most useful; unfortunately, the federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) Working Group struggled to generate engagement from the provinces and territories. The national review committee process for applications was perceived as very efficient, a large volume of applications for community-driven projects were reviewed in a short period of time. Regional office intelligence and relationships were important in identifying key proponents and projects, and ensuring an appropriate distribution of funding.

Conclusions: best Practices and Lessons Learned

The following are best practices and lessons learned from the Canada 150 initiative that could be useful to future large, one-time, cultural, commemorative, or sporting events.

Governance

Due to mixed views on the organizational structure, future senior decision-makers need to be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of the various ways to structure and staff a special secretariat or other coordinating body to achieve the desired impact.

Delegation of Ministerial authority to Directors General and Regional Executive Directors for decisions on smaller special event grants and contributions (under $75,000 for most programs in 2016) can contribute to a more efficient process.

Partnership

Collaboration between the private sector, other government departments (OGDs), partners, stakeholders, and delivery organizations was highlighted as a key contribution to the success of the initiative. Enabling such cross-sector relationships should be a central feature of any future similar initiatives.

An ADM-level committee can be very effective in engaging OGDs in a large-scale horizontal initiative.

The approach of organizations connected to the community awarding the individual grants allowed for an alignment of the projects funded with the needs of each community. Using these local actors with knowledge of community priorities, and allowing them the flexibility to design and implement projects, while coordinating the initiative at the national level, was successful in supporting projects that were important to Canadians. The leveraging of both community foundation and government funding through a matching formula was considered a best practice.

Objectives, Planning and Reporting

To support reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians and to improve engagement in future large-scale events, PCH should continue to support a broad eligibility for funding that enriches our understanding of Canadian history with many interpretations of the meaning of the past.

In the case of an event with significant funding, legacy projects are seen as having high value.

Should economic objectives be assigned to an event, a pre-established methodology and systematic data collection are needed to assess economic impact.

With regard to reporting, more accurate participation and attendance estimates need to be developed and used consistently across the country to allow for a better analysis of impact.

Industry Day demonstrated some of the benefits of ensuring there are occasions to meet other recipients and existing partners. That said, there should be careful measurement of corporate engagement and increased private sector funding attributable to such an event.

Design and Delivery

For a large, pan-Canadian grants and contributions fund, a national review committee process can be very efficient. Regional offices’ expertise, strategic intelligence, and delivery capacity should be fully engaged.

Consideration should be given to developing an application process where the level of effort involved in application and payment is proportionate to the size of the amount being awarded.

Small and micro-grants

In the case of small or micro-grants, an easy and short online application form can increase interest and participation at the grassroots level and reduce the administrative burden on PCH.

The use of artificial intelligence was only a first step toward what is possible; the process of developing an algorithm to automate the distribution of micro-grants can be repeated and adapted for many funding models. Additional opportunities to apply algorithms and other artificial intelligence solutions could also be explored.

Evaluation of applications for small and micro-grants should be tailored, since the capacity of charitable or less formal organizations varies.

1. Introduction

As per the 2018-19 to 2022-23 Departmental Evaluation Plan, Canadian Heritage (PCH) conducted an evaluation of the relevance and effectiveness of the Canada 150 Fund, the Canada 150 Federal Secretariat (FS), and the activities undertaken as a result of PCH’s incremental funding toward the achievement of Canada 150 expected outcomes. The evaluation covers the duration of the initiative from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2018 (fiscal years 2015-16 to 2017-18).

Section 2 provides an overview of the Canada 150 initiative. Section 3 describes the approach and methodology used to conduct the evaluation. The report also provides a detailed synthesis of the findings in Section 4, for each of the evaluation questions. Sections 5 and 6 respectively present conclusions as well as lessons learned for the future.

2. Program overview

In 2017, the Government of Canada marked the 150th anniversary of Confederation with a year-long celebration from coast to coast to coast. Canada 150 provided an opportunity for Canadians to “Celebrate, Participate, and Explore” what it means to be Canadian. The joint shared outcome among federal departments was: “Canadians are engaged in vibrant communities, have a sense of pride and attachment to Canada and to local communities, and benefit from economic impacts and lasting legacies.” Federal institutions were to invest in support of one of four Canada 150 Key Objectives to achieve the joint shared outcome: PCH supported Bringing Canadians together.

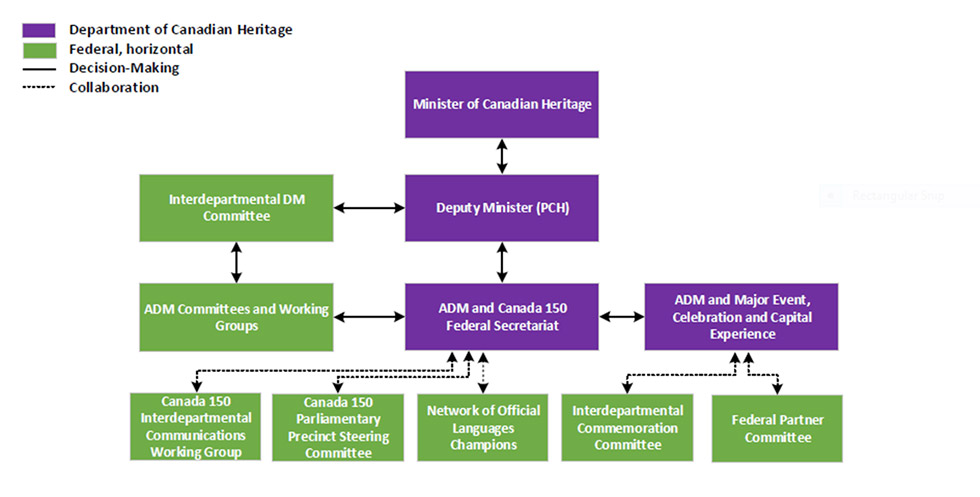

As the lead of this horizontal initiative, PCH was responsible for coordinating the efforts of Canada 150 for the federal government, as well as for engaging federal, provincial and municipal agencies and institutions, and the private and not-for-profit sectors to foster strategic partnershipsFootnote 2 and manage branding. A networked governance model, with horizontal decision-making and accountability structures, was used to interact with the large number of stakeholders.

Source: (Canada 150 Federal Secretariat, 2016, p. 8).

Figure 1: Canada 150 Governance – text version

This pyramid figure illustrates the governance of the Canada 150 initiative inside the hierarchical structure of the Department of Canadian Heritage, and the collaboration provided by various committees which included other federal players. Using purple boxes, it shows clearly that two ADMs and their branches had decision-making authority and reported to the Deputy Minister, who reported to the Minister, the top purple box in the figure. The Deputy Minister was supported by an Interdepartmental DM Committee which had decision-making powers, and itself collaborated with various ADM-level committees, shown in lime green boxes. The ADM and the Federal Secretariat collaborated with these ADM-level committees as well as: shown in a row of lime-green boxes along the bottom of the figure, Canada 150 Interdepartmental Communications Working Group, Canada 150 Parliamentary Precinct Steering Committee, and a Network of Official Languages Champions. The ADM and Major Event, Celebration and Capital Experience Branch collaborated with the Interdepartmental Commemoration Committee and Federal Partners Committees, both shown in green boxes along the bottom of the figure.

PCH housed the Federal Secretariat (FS), reporting directly to the Deputy Minister, which served as the official authoritative source for national Canada 150-related information and celebrations, and also served as the primary coordinating body of the initiative with the support of other PCH programs. The FS relied on the programs of various federal institutions to deliver projects or to manage grants and contributions. The PCH-managed Canada 150 Fund supported three types of projects:

- Signature initiatives, which were large in scale and pan-Canadian in scope;

- Major events in 19 major Canadian cities which aimed to celebrate key milestones of 2017, including launch events on New Year’s Eve and events during Celebrate Canada Week; and

- Community-driven projects in communities across the country.

From June 2016 onward, following the change in government, the four priority areas for funding were:

- Diversity and inclusion;

- Supporting efforts toward national reconciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians;

- Engaging and inspiring youth; and

- Our environment.

The total overall planned funding from fiscal year 2015-16 to fiscal year 2018-19 was $210 million (excluding existing funds). This included $28 million of operating expenditures, and $182 million of transfer payments. Private and not-for-profit organizations and municipalities were eligible for funding.

The Special Projects Team of the Celebration and Commemoration Program (CCP) and regional offices, were responsible for the administration of the Canada 150 Fund, including approving projects, secretariat services for the selection committee and managing contribution agreements. The FS also coordinated with Signature initiatives as well as some of the larger community-driven recipients, such as the Community Foundations of Canada (CFC). The FS engaged more than one hundred well-known Canadians to serve as Ambassadors for Canada 150 throughout the year. In collaboration with the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM), the program engaged 800 community leaders across the country to help increase the visibility of Canada 150 and served as a voice of the community in the celebrations.

Similarly, the Communications Branch of PCH supported the FS and led the Canada 150-related communications and marketing activities. Planning, coordination and implementation of Canada 150 among federal departments occurred through a series of committees and working groups, all but one (the Interdepartmental Commemoration Committee) set up for that purpose. They were: Deputy Minister (DM) Coordinating Committee on Canada 150, the Assistant Deputy Ministers (ADM) Committee and Sub-Committees, the Interdepartmental Communications Working Group, and the Interdepartmental Commemorations Committee.

3. Approach and methodology

This section provides an overview of the methodology used to evaluate the various components of Canada 150. It defines the scope of the evaluation, as well as the range of methods used to gather relevant data and information that addressed the evaluation questions.

The evaluation included a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods that allowed for triangulation of findings.

3.1. Scope and timeline

The scope of this evaluation included the approximately $210 million in investments through the Canada 150 initiative, and a review of the activities and funding of the FS (approximately $10 million). This evaluation covered three fiscal years, from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2018.

3.2. Evaluation questions

The evaluation addressed the following questions:

Table 1: evaluation questions by core issue

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Assessment of the extent to which Canada 150 addressed a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians |

|

| Alignment of the linkages between program objectives and federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes |

|

| Assessment of the role and responsibilities for the federal government in delivering the program |

|

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Achievement of expected outcomes |

|

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes |

|

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of the design and delivery |

|

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of the Federal Secretariat’s oversight and coordination of the Canada 150 initiative |

|

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Lessons learned |

|

The complete evaluation matrix, including indicators and associated data sources, can be found in Appendix A.

3.3. Data collection methods

Multiple lines of evidence were used to address the evaluation questions, including a document and administrative data review, key informant interviews, a survey of partners and funding recipients, three case studies, and an analysis of media coverage.

3.3.1. Document and data review

The document and data review were guided by the evaluation matrix (Appendix A). It relied primarily on documentation provided by PCH or accessed through the PCH website, and in a few instances, information available through the Statistics Canada portal and other data sources. While the FS provided significant amounts of documentation, some of the intended evaluation questions and indicators were not fully addressed by this line of evidence (e.g., the public’s awareness of legacy projects). While not all final reports were received by PCH by the time the document and data review concluded in 2018, data generated from the departmental grants and contributions management system (GCIMS), was cleaned and verified by ESD in July 2019.

Documents reviewed include the following:

- FS internal database (a set of worksheets)

- FS Operational Dashboards

- Canada 150 branding strategy

- Communications framework

- Governance framework

- Public Opinion Research (POR) surveys

- Strategic analysis and advice documents

- Documents containing the program description, objectives, requirements, such as Terms and Conditions, and Contribution Guidelines

- Departmental Plans (formerly known as Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPP)) and Departmental Results Reports (formerly known as Departmental Performance Reports (DPR))

- Government of Canada Budgets, Speeches from the Throne, Memoranda to Cabinet, and Treasury Board submissions

- Print media articles captured in the departmental database (MediaScope)

3.3.2. Interviews with key informants

A total of 48 interviews (with 49 individuals) were conducted with key informants in order to collect in-depth information regarding specific evaluation questions. The key informants were selected in collaboration with the Evaluation Working Group (including representatives from ESD, the FS, and programs such as the CCP). The interviews discussed in this report were conducted between July 11, 2018, and September 20, 2018. The table below provides the distribution of completed interviews by respondent category.

| Key informant group | # of interviews | # of interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| PCH management and staff | 14 | 14 |

| Members of the DM and ADM Interdepartmental Committees | 4 | 4 |

| National and regional stakeholders | 6 | 6 |

| Partner organizations | 13Table 2 note * | 14 |

| Recipient organizations | 11 | 11 |

| Total | 48 | 49 |

Table 2 notes

- Table 2 note *

-

10 interviews were conducted and 3 key informants submitted written answers.

Throughout the report, the relative frequency of the qualitative findings from key informant interviews is reported using the following scale:

- “almost all” – findings reflect the views and opinions of 90% or more of key informants;

- “large majority” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 75% but fewer than 90% of key informants;

- “majority” or “most” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 50% but fewer than 75% of key informants;

- “some” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 25% but fewer than 50% of key informants; and

- “a few” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least two key informants but fewer than 25% of key informants.

3.3.3. Surveys of recipients and partners

Two online survey questionnaires were developed; one for partners and one for recipients of the Canada 150 Fund. There were 27 valid responses to the survey of partners, and 172 valid responses to the survey of recipients. The response rate was 6.4% for the survey of partners (see also Section 3.4 Constraints, limits and mitigation strategies) and 25.7% for the survey of recipients.

The partner survey was fielded from August 15 to September 14, 2018. A total of 405 email invitations were sent, as well as two reminders. The funding recipient survey was fielded from August 15 to September 13, 2018. A total of 673 email invitations were sent, as well as two reminders. Reminders for both surveys were sent on August 22 and 29, 2018. Participation in the survey was voluntary.

3.3.4. Case studies

Case studies were intended to address specific evaluation questions with regard to experiments undertaken by the Department (see evaluation matrix in Appendix A). The selected cases were: the Community Fund for Canada’s 150th, Skating Day, and Industry Day. The case studies relied on documents provided by PCH, key organizations, or accessed online; as well as interviews with program representatives and external stakeholders. The type of documentation and number of interviews varied by case study. This is summarized in Table 3.

| Case | Documents reviewed | Number of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Community Fund for Canada’s 150th | Comprehensive project reports from the Community Foundations of Canada, and PCH | 7 (with representatives from CFC individual Community Foundations; and PCH) |

| Skating Day | Comprehensive lessons learned report by the Chief Information Officer Branch (CIOB) of PCH; final project report by the Prairie and Northern Region (PNR) office; the micro-grant recipient survey results; the departmental report on experimentation with micro-grants | 7 (with representatives from the FS, CIOB, PNR, the Financial Management Branch and the Centre of Expertise in Grants and Contributions within PCH, as well as with Skate Canada) |

| Industry Day | Documents on activities leading up to and occurring during the Industry Day event; post-mortem report by the FS | 5 (representatives from the FS, Signature initiatives proponents, industry participants who sponsored projects) |

3.3.5. Media coverage analysis

This line of evidence involved a quantitative and qualitative analysis of media coverage of the Canada 150 initiative from April 1, 2015, to March 31, 2018. This analysis was composed of two parts. In the first, an analysis of the social media coverage of the initiative was conducted to assess the reach and impact of PCH messaging via social media accounts. The social media analysis was done, in part, by analyzing reports prepared by the FS for each of its social media accounts. In the second, PCH conducted a media coverage analysis, which included French and English print and broadcast media on topics relating to Canada 150 captured in the PCH MediaScope database, in order to study specific issues of relevance, impacts and benefits of the Canada 150 activities, as identified in the evaluation matrix. Taken together, these analyses were designed to complement or fill gaps relative to other lines of evidence, and illustrate themes that were particularly amenable to media coverage.

Short technical reports were prepared, by evaluation theme, notably: impact of Canada 150 priority areas, evidence of economic benefits and impacts generated by Canada 150 projects, and awareness and media coverage.

3.4. Constraints, limits and mitigation strategies

Stakeholders have a vested interest in the program

Most key informants and survey respondents had a vested interest in Canada 150, which could have led to positive bias in responses. No unsuccessful applicants were contacted. Where possible, this limitation was mitigated by triangulating several lines of evidence.

Ability to find stakeholders to participate in the evaluation

It was challenging to interview staff, partners, stakeholders, and recipients, as a considerable amount of time had elapsed since their involvement. It was difficult, in certain cases, for them to recall details, and many staff who had been on assignment for Canada 150 have since transferred back to a previous position or elsewhere. The challenge of finding appropriate stakeholders to interview arose in the case studies as well.

There was also a high number of incomplete responses and a relatively low response rate for both surveys. There were only 27 valid responses and a response rate of 6.4% for the survey of partners, and 172 valid responses and response rate of 25.7% for the survey of recipients.Footnote 3 Due to the extremely low response from partners, there was an additional follow-up with 15 partner organizations by telephone in an attempt to increase the response rate and also to recruit for additional key informant interviews. This process yielded additional responses (included in the response rate indicated above).

Interviews with major sponsors or any of the high-profile ambassadors did not take place, despite attempts made.

4. Findings

4.1. Relevance

4.1.1. Assessment of the extent to which Canada 150 addressed a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians

Evaluation questions: to what extent were PCH Canada 150 (Canada 150 Fund) activities relevant to Canadians?

How supportive were Canadians of Canada 150 activities?

Was supporting Canada 150 activities worthwhile?

Key finding: PCH Canada 150 activities were relevant to many Canadians, including to those who participated in Canada 150 events, organizations who applied for funding, and the general public. Interest in the Canada 150 Fund was high, and activities were deemed worthwhile by Fund recipients, including those activities that created or strengthened partnerships.

Level of participation

Participation in Canada 150 activities was significant, and was higher than anticipated in the public opinion research (POR) Wave I. Part of the rationale for developing the Canada 150 initiative was based on POR Wave I (conducted in June 2016) results, which stated that the majority of those surveyed (65%) indicated that they would participate in the celebrations. When the final POR survey was conducted in January 2018, 70% of respondents indicated that they had participated in Canada 150 activities. Participation included: watching a Canada 150 event on television or on the Internet (37%); visiting a national park, national historic site, or waterway (35%); attending a Canada 150 event outside of their community (19%); and volunteering for a Canada 150 event, activity, or initiative (5%).

The reported participation in the five Celebrate Canada Week events is indicated in Table 4 below.

| Event | Attendance | TV viewers |

|---|---|---|

| Canada Day | 2,556,000 | 15.00 million |

| National Indigenous Day | 120,600 | 1.20 million |

| Canadian Multiculturalism Day | 24,000 | - |

| Saint-Jean-Baptiste DayFootnote 4 | 13,400 | - |

| Royal Tour of the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall | - | - |

Source: (Canadian Heritage, 2017f, 2018a, 2018f, n.d.-c).

Survey results provided additional insights into the level of participation in Celebrate Canada Week activities. The POR Wave II (conducted in July 2017) found that 60% of respondents who visited official sites in the National Capital Region (NCR) during Canada Day (Major’s Hill Park, Parliament Hill, and the grounds of the Canadian Museum of History) did not live in the Capital Region. Of those, 92% lived elsewhere in Canada, and the rest were residents of other countries.

Applications and funded projects

The large number of applications made to the Canada 150 Fund for funding also indicates that there was a substantial interest in developing and participating in Canada 150 events. The document review highlighted that, as early as 2016, there were 387 expressions of interest for Signature initiatives and Community-driven projects. Table 5 indicates how many applications for all types of events were received between fiscal years 2015-16 and 2017-18.

| Region | # of applications | % of applications | # funded | % funded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | 876 | 22% | 147 | 20.4% |

| Prairies and North | 381 | 10% | 69 | 9.6% |

| Ontario | 1,527 | 38% | 181 | 25% |

| Québec | 647 | 16% | 107 | 15% |

| Atlantic | 578 | 14% | 216 | 30% |

| All regions | 4,009 | 100% | 720 | 100% |

Source: (Canadian Heritage, 2019a).

Importance and worthiness of celebrating Canada 150 activities

Key informants and survey respondents noted that PCH Canada 150 activities were relevant and important to Canadians, and that their participation was worthwhile. There was consensus among key informants that it is important to recognize national milestones, reflect on our history, and remind Canadians of who they are. These evaluation findings are also supported by survey results; 95% of funding recipients considered their investments of time and effort in Canada 150 to be worthwhile. One of the most commonly cited benefits was that Canada 150 activities created or strengthened partnerships. Interviews found evidence of new or improved partnerships between community organizations, private companies, municipal and provincial legislative bodies, PCH, and international partners. From a tourism perspective, Canada 150 put Canada in the global spotlight and gave the country a high level of visibility it would otherwise not have received. Interviews further suggest that Canada 150 activities were worthwhile for the following reasons:

- They provided Canadians with a platform to discuss reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

- They promoted great things about Canada (e.g., culture, natural beauty) to Canadians and the world, thus leading to a sense of pride in Canada.

- They brought communities together and helped to build a sense of identity within them.

- They allowed local and not-for-profit organizations to become more visible in their communities; reach out to new audiences; improve their capacity, experience, and credibility; and develop new networks of partners.

- They reached high levels of participation and engagement.

- They created tangible legacies.

Notwithstanding the positive feedback, some key informants had mixed views on whether Canada 150 activities were worthwhile. This is further discussed in Section 4.1.2.

Finally, evaluation findings suggest that the ability to bring Canadians together varied by type of event, by geographic location, as well as by demographics. For example, Community-driven events had the most lasting impacts, allowed for positive spinoffs, had large numbers of participants, and were generally the most consistently positively cited by key informants. Further, funding to community-based organizations allowed them to build capacity, become better known in their communities, and develop partnerships with other actors that will benefit their communities in the future. Major Events and Signature initiatives, meanwhile, were seen to be relevant for celebrating the sesquicentennial, though some key informants noted that they were not always well delivered or worth the cost to taxpayers.Footnote 5 Interview findings suggest that the relevance of Canada 150 activities also depended on the province or territory in question. As many Canada 150 events were held in the NCR or in large urban centres, Canadians living outside of those areas may not have been able to attend them very often. Their relevance in ranking them depended in large part on their proximity to those events. The importance of Canada 150 events was also lower in regions that had recently celebrated a significant anniversary (e.g. P.E.I. in 2014), or were celebrating another anniversary concurrently (e.g. Montréal 375 or Ontario 150), or were not among the original provinces at the creation of the confederation in 1867 (e.g., Saskatchewan).

4.1.2. Alignment of the linkages between program objectives and federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes

Evaluation question: how did Canada 150 activities align with the four policy priority areas?

Key finding: most Canada 150 activities and events were delivered in an inclusive way and aligned with one or more of the four government policy priority areas. All four priorities were addressed, with “diversity” being the most prevalent and “our environment” being the least.

Until mid-2015, the overarching theme planned for the initiative was “Canada: Strong, Proud and Free,” with three sub-themes: Giving Back to Canada (legacy building and giving gifts to Canada); Honouring the Exceptional (providing role models); and Celebrating and Bringing Canadians Together (building an understanding of what it means to be Canadian).

In January 2016, the federal government identified the four following policy priority areas for Canada 150 activities:

- Diversity and inclusion (which includes incorporation of linguistic duality in events);

- Supporting efforts toward national reconciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians;

- Engaging and inspiring youth; and

- Our environment.

The change in the policy priority areas in January 2016 presented challenges; this may explain why some policy priority areas were less targeted by funding recipients.

Findings from multiple lines of evidence speak to PCH’s efforts to align Canada 150 activities with the priority areas. The FS monthly Operational Dashboards identified approved Signature and community-driven projects according to themes under the four 2016 priority areas. As of December 2017, there were 749 themes identified in the 674 Signature and community-driven projects. There were more themes adhered to than projects because a project could support more than one of the four priority areas and be related to more than one theme. Table 6 below shows the number of themes identified for the Signature and community-driven projects. Just over half (56%) of the community-driven projects and Signature initiatives involved a diversity-related theme, and just over one quarter (27%) involved a youth-related theme. This confirms that Canada 150 Signature and community-driven projects included events that covered all four of the government priority areas, with the diversity theme being the most prevalent.

| Priority area | n | % of projectsTable 6 note * |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity | 378 | 56% |

| Youth | 185 | 27% |

| Environment | 96 | 14% |

| Reconciliation | 90 | 13% |

| Total count of priority areas | 749 | 111% |

| Total Community and Signature initiatives | 674 | - |

Source: (Canadian Heritage, 2017f).

Table 6 notes

- Table 6 note *

-

Percentages total more than 100% due to multiple priority areas for some projects.

With very similar goals, Canada 150 partnered with the Community Foundations of Canada to administer and deliver funding in communities. CFC provided funding to match their Canada 150 grant, for a total of $16 million distributed among 627 communities. Consistent with PCH goals, CFC goals to mark the 150th were to:

- encourage participation in community activities and events to mark Canada’s 150th anniversary of Confederation.

- inspire a deeper understanding about the people, places and events that have shaped and continue to shape our country and our communities.

- build vibrant and healthy communities with the broadest possible engagement of all Canadians, including Indigenous Peoples: groups that reflect our cultural diversity; youth; and official language minorities.

The CFC’s Community Fund for Canada’s 150th reported on the priority areas served.

| Youth | Culturally diverse | Indigenous Peoples | Official language minorities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved | 85% | 79% | 55% | 41% |

| Led projects | 34% | 51% | 24% | 16% |

Interview and survey findings also highlight efforts to align Canada 150 activities with the priority areas. Almost all recipients and stakeholders agreed that many Canada 150 projects were delivered in a way that was inclusive and promoted these areas.

Diversity and inclusion

The Tourism Industry Association of Canada, the Canada 150 Diversity Award

A successful project that championed the diversity of Canadian society occurred when the FS and the Tourism Industry Association of Canada (TIAC) partnered to create the Canada 150 Diversity Award, which celebrated organizations that “have helped to shape Canada as a modern, innovative, and welcoming destination” (Travel Industry Association of Canada, 2017). Organizations were rated on the extent to which they celebrated diversity in all its forms; had a positive social/cultural impact on the host community(ies) or on Canada; demonstrated innovation in the service or product offered or created; stimulated economic and tourism activity in the host community(ies); and attracted an international audience and/or the attention of the international community. The award was won by SESQUI Inc., a revolutionary 360-degree cinematic experience that also featured virtual reality storytelling, interactive games, and learning resources created by local artists and creators.

Findings from multiple lines of evidence indicate that there was a strong alignment with the diversity and inclusion priority, which included such things as official language minority communities (OLMC), Indigenous people, ethnocultural and racialized groups, and youth. The document and data review highlights that Canada 150 activities, such as the December 31, 2016, launch events in Ottawa and 18 other Canadian urban centres, and Winterlude in February 2017, offered content that highlighted and promoted Canada’s cultural and regional diversity and linguistic duality. Similarly, PCH supported a wide range of diversity-themed national celebrations, including Black History Month, National Aboriginal Day, and Canadian Multiculturalism Day. Most of the diversity or inclusion-themed projects were linked to PCH’s strategic outcome of “Canadians share, express and appreciate their Canadian identity.”

The extent to which Canadian diversity and inclusion was promoted by Canada 150 activities is further supported by survey results. A total of 91% of funding recipients reported that their project focused on the diversity of Canadian society to a moderate or great extent. The media analysis reveals that the inclusion of diverse cultures was positively viewed in Canada 150 events, particularly with Community-driven and Major Events during the Celebrate Canada period.

While key informants noted that Canada 150 events promoted diversity and inclusion, few were able to provide tangible examples beyond stating that their event was open to anyone who wanted to attend.

Linguistic duality and Official Language Minority Communities

A key objective of the diversity and inclusion priority was to focus on and promote linguistic dualityFootnote 6 and OLMCs. PCH’s RPP for 2016-17 indicated that the Canada 150 initiative would support the promotion of OLMCs, and PCH’s DRR for 2016-2017 identifies that the Canada 150 initiative’s Major Events and celebrations provided activities that highlighted and encouraged, among other things, Canada’s linguistic duality. Findings from the document and data review confirm that there was a significant level of promotion of linguistic duality that occurred for the Canada 150 projects directly supported by PCH. Notably, the Museums Assistance Program supported three travelling exhibitions that promoted linguistic duality: Through the Eyes of the Community, A Story of Canada, and 1867 – Rebellion and Confederation.

Findings from interviews indicate that internal key informants, partners, stakeholders, and funding recipients supported Canada’s linguistic duality. For example, stakeholders and internal key informants noted that PCH did a good job of promoting and celebrating Canada’s linguistic duality through funded activities; this was especially true for larger events. Internal key informants outlined several measures the Department took to ensure that projects were sufficiently bilingual, including providing significant official languages support for all projects that received over $300,000 in funding. In particular, interview findings suggest that Signature initiatives included online materials, exhibits, and translation for live events were fully delivered in both official languages. Internal key informants noted that the FS arranged for a representative from the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL) to do targeted outreach with non-OLMCs to ensure that they were meeting the minimum level of French or English necessary, to answer questions recipient organizations had, and to refer them to other organizations that could support their language efforts.

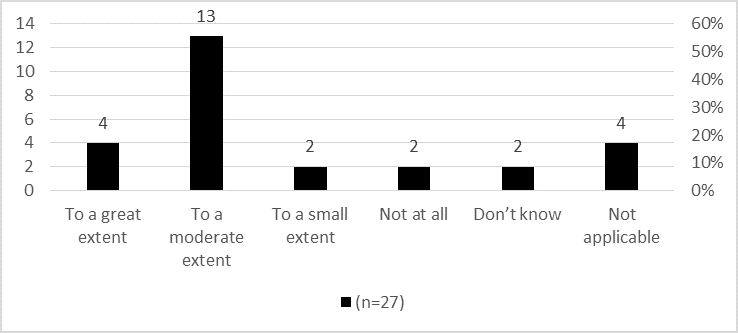

Similarly, funding recipients noted that their projects recognized and supported Canada’s linguistic duality by having: bilingual signage, communication and promotion materials; bilingual masters of ceremonies; artists and performers representing both official language groups; and a bilingual presentation or ceremony that recognized the funding they received from the Canada 150 Fund. In certain instances, events also occurred in their community’s respective Indigenous language. Survey results further suggest that Canada 150 activities promoted the integration of Canada’s linguistic duality in events. As indicated in Figure 2 below, of partners surveyed (n=27), 63% responded that the activities promoted the integration of duality to a moderate or great extent. Fifteen percent of the respondents indicated that it did not apply.

Figure 2: “to what extent do you believe that the Canada 150 activities have promoted integrating Canada’s linguistic duality in events?” number and percentage of respondents – text version

| - | (n=27) | (%)Figure 2 table note * |

|---|---|---|

| To a great extent | 4 | 15% |

| To a moderate extent | 13 | 48% |

| To a small extent | 2 | 7% |

| Not at all | 2 | 7% |

| Don’t know | 2 | 7% |

| Not applicable | 4 | 15% |

| Total | 27 | 99% |

Figure 2 table notes

- Figure 2 table note *

-

Column may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Finally, in their annual report, OCOL devoted a chapter to Canada 150. Four complaints were made against PCH-funded projects. Three complaints dealt with activities taking place on the Canada 150 Skating Rink, which were all quickly and satisfactorily addressed by the project recipient. One complaint led to a separate recommendation: to ensure that PCH meets its obligations under the Official Languages Act, it should establish a monitoring and accountability mechanism to ensure compliance with the languages clauses included in contribution agreements with third parties.

Engaging and inspiring youth

The Students on Ice Foundation, Canada C3 Expedition

One particularly successful project was the Canada C3 expedition organized by the Students on Ice Foundation to commemorate the centennial of the Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913-1916). Youth aged 14 to 18 participated in annual sea and land-based expeditions from 2013 through 2016. Each journey included about 85 students and a team of 45 world-class scientists, historians, Elders, artists, explorers, educators, innovators, and polar experts. To celebrate the sesquicentennial in 2017, the Foundation received slightly more than $7 million from PCH, and addressed the themes of youth and our environment. Findings from the media coverage analysis indicated that the C3 expedition received broad coverage, most of it positive.

Findings from several lines of evidence indicate that many of the Canada 150 events supported a youth theme and engaged a significant number of youth across the country. As mentioned previously, the operational Dashboard data identified that 185 (27%) of the Community and Signature projects involved a youth theme. Further, almost all articles reviewed in the media coverage analysis were positive about the Canada 150 projects that focused on youth. Funding recipients and partners noted that youth were a target audience for their events more than they were a theme to be addressed. Key informants highlighted that the significant social media and online presence of Canada 150 (e.g. videos, Twitter hashtags, Web chats) made Canada 150 more accessible and appealing to youth.

National reconciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians

Vancouver, “City of Reconciliation”

In response to the TRC Calls to Action and in partnership with the three Host Nations of Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh, Vancouver engaged its citizens under the title, "Strengthening Our Relations. Each Nation had a representative on the city’s Canada 150+ Working Committee. With a primary purpose of Indigenous employment, Canada 150+ delivered vibrant and interactive Indigenous and cross-cultural events and experiences throughout 2017, allowing residents and visitors to see unexpected public places and spaces in Vancouver activated and reimagined. Results included: 7 of 8 apprentices having jobs or job offers in their area of training; 149,000 people attended the Drum is Calling Festival and 82% of respondents to a subsequent survey agreed that “this event helps Indigenous and non-Indigenous people move forward together." City staff recommended: that the Indigenous apprenticeship model continue to be used to create pathways to employment; the creation of a Reserve fund for Cultural Reconciliation projects; and five other quick starts to support recurring and new Indigenous-led activities that carry forward the Canada 150+ legacy and spirit of reconciliation.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s (TRC) Call to Action 68 recommended that the 150th anniversary be marked with funding for commemorative projects on the theme of national reconciliation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians:

“We call upon the federal government, in collaboration with Aboriginal people, and the Canadian Museums Association to mark the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation in 2017 by establishing a dedicated national funding program for commemoration projects on the theme of reconciliation” Footnote 7

The document and data review indicates that 13% of Signature projects (5 projects, totalling $3.6 million) focused on reconciliation (e.g. Reconciliation Canada, Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum). Thirty-nine percent (248 projects) of Community-driven projects contributed to celebrating Indigenous communities (161 projects), reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians (10 projects), or both (77 projects); for a total investment of $28.6 million. In addition, interviews and the media coverage analysis suggest that reconciliation featured in many Canada 150 activities without necessarily being the primary theme. For example, some Canada 150 activities did not have a reconciliation lens but did acknowledge that the event was being held on the traditional and unceded territory of First Nations.

The media analysis revealed positive and frequent articles on Canada 150-funded projects undertaken in a spirit of reconciliation by the Canadian professional arts sector. Among them were the New Constellations music tour featuring Indigenous and non-indigenous musicians, and Stratford Festival’s “The Breathing Hole,” a play workshopped with Indigenous people and hiring Indigenous actors. Kent Monkman’s travelling “Shame and Prejudice; A Story of Resilience” was referred to as “most talked-about” art show of the anniversary and internationally reviewed.

The Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada

The Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, the Royal Geographic Society of Canada’s reconciliation project, was intended to be a story told by Indigenous people. The 4-volume book, giant educational floor maps and companion app were produced in partnership with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the Assembly of First Nations, the Métis National Council, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Indspire. The Atlas was the #1 bestselling Young Adult Non-Fiction print book in 2018, due partially to the purchase by the Alberta government of 1,600 copies to place in schools. Currently it rates 4.5 stars out of 5 among reviews by Amazon.ca verified customers.

The media analysis suggests that some Indigenous Canadians found the term “celebration” appeared to exclude pre-Confederation history and unsolved treaty and Indian Act issues. The Government of Canada acknowledged this sentiment in June 2017, stating that “we have to recognize that not everyone is going to be celebrating the same way and the past 150 years for Indigenous Peoples has not been as positive; recognizing that thereʾs a lot more that we need to do together, in respect, is an important part of this recognition.”

The University of Manitoba’s Reconciliation Circles

This community project was designed to bring Indigenous and non-Indigenous people together to discuss issues relating to Indigenous culture and beliefs. The university intended it to lead to a greater understanding by the general public of the issues that Indigenous Peoples face, and to foster respectful relationships between these two groups. Despite the grant for this project having ended, the university continues to get regular requests from communities, companies, and organizations across the country to organize circles in their area.

Interviews and media sources also reveal worries that the respect for reconciliation expressed through Canada 150 might not lead to action on recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Though articles on this subject were published throughout Canada, there was more interest in the link between Canada 150 and reconciliation in the English-language press.

Our environment

Six Signature projects (16%, totalling $11.7 million) focused on the environmental theme, such as the Canadian Wildlife Federation’s “bioblitzes” to document species across the country, and 89 Community-driven projects (14%, or $9.6 million which sought to connect Canadians with nature and were designed to raise environmental stewardship. Other examples include Tree Canada’s national campaign to restore local parks, recreation areas or school grounds through the planting and caring for trees, and many projects at the local level led by conservancy or stewardship societies.Footnote 8

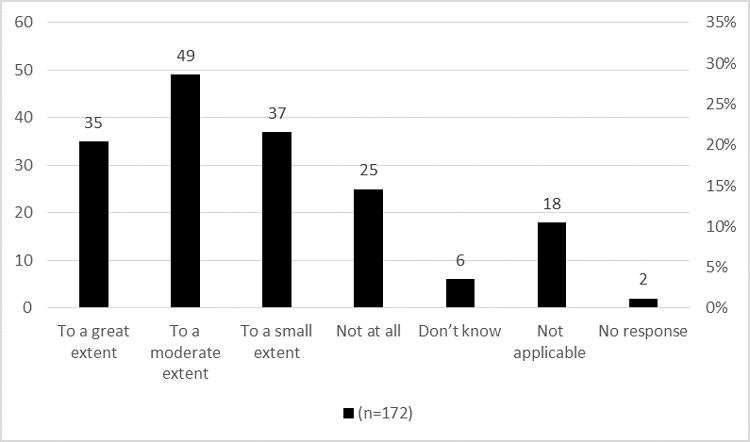

Interviews further suggest that funding recipients worked with their delivery partners (e.g., food trucks) to encourage sustainable food practices and to minimize the use of one-off materials (e.g. brochures). Survey results further support the idea that, while respect for the environment was often not the primary theme of an event, funding recipients did take it into consideration. For example, funding recipients were asked to what extent their projects focused on environmental stewardship. Their responses are summarized in Figure 3. While 49% indicated that their projects focused to a moderate or a great extent on environmental stewardship, 22% indicated their projects focused on this area to a small extent, 15% indicated their projects did not focus on that at all, and another 10% indicated it did not apply.

Figure 3: "to what extent did your project focus on environmental stewardship?” number and percentage of respondents – text version

| - | (n=172) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| To a great extent | 35 | 20% |

| To a moderate extent | 49 | 29% |

| To a small extent | 37 | 22% |

| Not at all | 25 | 15% |

| Don’t know | 6 | 4% |

| Not applicable | 18 | 10% |

| No response | 2 | 1% |

Tree Canada’s Tree to our nature

This Community-driven project by Tree Canada supported community greening initiatives by inviting community organizations to restore a local park, recreation area or school ground in need, through the planting and care of trees to help mark Canada’s 150th. Communities planted native and historically significant trees including the maple (Canada’s Arboreal Emblem), the relevant Provincial/Territorial Arboreal Emblems as well as a White Pine and/or Western Red Cedar (significant to First Nations communities as a symbol of peace and reconciliation). This project provided an opportunity for thousands of Canadians to build environmentally sustainable communities and leave a lasting legacy of Canada 150 for future generations to enjoy. Activities included inviting 150 community organizations to restore a local park, recreation area or school ground in need, through the planting and care of trees; targeting applications from communities from coast to coast including those inclusive of new Canadians, visible minority groups, and First Nations communities; and installing commemorative plaques in the park / community space to commemorate Canada's 150th anniversary of confederation.

Evaluation question: how did Canada 150 activities align with the PCH objectives of Canada 150 (Bringing Canadians Together)?

Key finding: Canada 150 projects and events sought to bring Canadians together. PCH officials and funding recipients focused heavily on this objective.

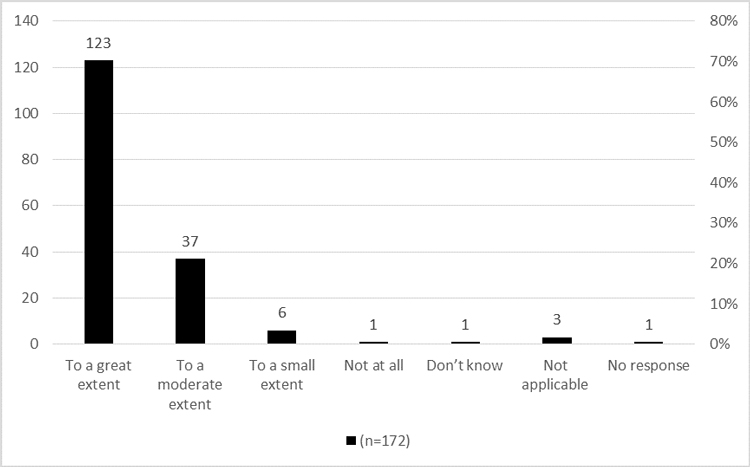

Numerous Canada 150 activities sought to align with the PCH objective of bringing Canadians together. Survey results indicate that this objective was a priority for funding recipients. As indicated in Figure 4, 93% of funding recipients reported that their projects focused on this to a moderate or great extent, 4% reported that they focused on this to a small extent, and 1% reported no focus on this.

Figure 4: "to what extent did your project focus on bringing Canadians together to mark and celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation?" number and percentage of respondents – text version

| To a great extent | 123 | 72% |

|---|---|---|

| To a moderate extent | 37 | 22% |

| To a small extent | 6 | 4% |

| Not at all | 1 | 1% |

| Don’t know | 1 | 1% |

| Not applicable | 3 | 2% |

| No response | 1 | 1% |

Evaluation question: how did Canada 150 activities contribute to departmental priorities and outcomes?

Key finding: the initiative was aligned with departmental outcomes and federal government priorities, roles, and responsibilities.

The evaluation found evidence of alignment between Canada 150 activities and departmental priorities as identified between 2015-16 and 2017-18. Strategic Outcomes for the Department include the following:

- Canadian artistic expressions and cultural content are created and accessible at home and abroad;

- Canadians share, express, and appreciate their Canadian identity; and

- Canadians participate and excel in sport.

The Canada 150 activities, as identified in the Canada 150 Operational Dashboards, show a significant proportion of federal initiatives classified by themes such as History and Heritage, Arts and Culture, Sports and Active Living. This indicates that Canada 150 activities aligned with the three strategic outcomes of the Department.

Canada 150 was mentioned as a government priority in the Speech from the Throne of April 2015, in the 2015 Economic Action Plan, the Federal Budget of March 2016, and the Federal Budget of March 2017. As well, the four policy priority areas themselves figure prominently among the government’s overarching priorities and, as such, are mentioned in federal Budgets and Throne Speeches throughout 2015, 2016, and 2017.

4.1.3. Assessment of the role and responsibilities of the federal government in delivering the program

Evaluation question: was delivering Canada 150 recognized as an appropriate federal government role and responsibility?

Key finding: it was appropriate for the federal government to recognize and support Canada’s sesquicentennial.

Delivering Canada 150 was recognized as an appropriate role and responsibility for the federal government to undertake. This is supported by findings from POR and interviews. As Table 8 indicates, most Canadians surveyed (83-89%) agreed that the federal government should recognize and support Canada 150 celebrations. In addition, between two thirds and three quarters (67-73%) agreed that they were satisfied with the way the federal government delivered Canada 150. Further, the majority also agreed that participating in Canada 150 would make them feel part of something important (56-72%) and that Canada 150 would leave a lasting legacy for Canada (58-67%), and a positive impact on their local community (58-63%). By January 2018, slightly less than half of Canadians (47%) thought Canada 150 would leave a lasting impact on their community. Generally, the Canadian public supported the Government of Canada’s efforts in regard to its Canada 150 initiative (though this support decreased over time), and Canada 150 was perceived as having a positive impact.

| Statement | June 2016 | July 2017 | January 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Government of Canada should provide financial support for Canada 150 celebrations. | 83% | N/A | N/A |

| The Government of Canada is/was right to recognize and celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation. | N/A | 89% | 88% |

| I am satisfied with the way the Government of Canada is delivering/delivered Canada 150. | N/A | 73% | 67% |

| Participating in Canada 150 will make/made me feel part of something important. | 72% | 67% | 56% |

| Canada 150 will leave a lasting legacy for Canada. | N/A | 67% | 58% |

| Canada 150 is having/had a positive impact on my local community. | N/A | 63% | 58% |

| Canada 150 will leave a lasting legacy in my community. | N/A | 55% | 47% |

Source: (Canadian Heritage, 2016b, 2017a; Quorus Consulting Group Inc., 2018a).

Similar findings emerged from interviews. Stakeholders and partners indicated that the federal government should celebrate this important national milestone and use it as an opportunity to bring Canadians together, increase pride in the country, and celebrate the nation’s history. Other key informants highlighted how Canada 150 activities complemented wider government priorities including stimulating local economies and innovation, and promoting Canada internationally.

4.2. Effectiveness - Achievement of expected outcomes

Evaluation question: what opportunities did Canada 150 provide to Canadians to participate in activities and events?

Key finding: a variety of projects of different sizes and foci were offered to Canadians in hundreds of communities, across all provinces and territories.

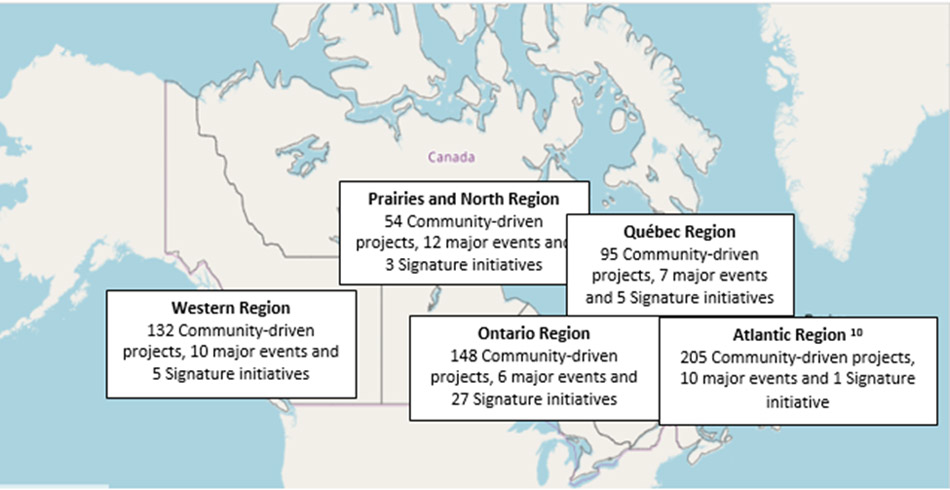

Canada 150 offered Canadians a variety of opportunities, across the country, to participate in activities and events, through the 720 projects that received funding through the Canada 150 Fund.Footnote 10 This included 38 Signature initiatives (delivered by 41 funding recipients), 634 community-driven projects, and 45 major events. Events and projects took place in Ontario (181), Atlantic Region (216), Western Region (147), Québec (107), and Prairies and Northern Region (69). The distribution of Major Events, Signature initiatives and Community-driven projects, by province, is presented in the table below.

Source: Internal Database GCIMS, July 2019.

Figure 5: number of major, Signature and Community-driven projects/events funded by the Canada 150 Fund per region from 2015-16 to 2017-18 – text version

The number of each of three different types of projects appears in a box for each of the PCH five administrative regions, superimposed on a map of Canada. The numbers go as follows:

Western Region

- 132 Community-driven projects

- 10 major events

- 5 Signature initiatives

Ontario Region

- 148 Community-driven projects

- 6 major events

- 27 Signature initiatives

Quebec Region

- 95 Community-driven projects

- 7 major events

- 5 Signature initiatives

Atlantic Region

- 205 Community-driven projects

- 10 major events

- 1 Signature initiative

Prairies and North Region

- 54 Community-driven projects

- 12 major events

- 3 Signature initiatives

| Region | Community driven projects (including Acadian Day) | Major events | Signature initiatives | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | 132 | 10 | 5 | 147 |

| Prairies and Northern | 54 | 12 | 3 | 69 |

| Ontario | 148 | 6 | 27 | 181 |

| Quebec | 95 | 7 | 5 | 107 |

| Atlantic | 205 | 10 | 1 | 216 |

Source: Internal Database GCIMS, July 2019.

In addition to the projects presented in the table above, other projects were funded through an innovative partnering with a philanthropic network, and micro-granting initiatives, as explored in case studies. The CFC’s Community Fund for Canada’s 150th received funding from the Canada 150 Fund to provide grants to 2,124 projects in 627 communities across Canada; and the micro-granting component of the Skating Day initiative provided 200 grants to community initiativesFootnote 11. Therefore, the total number of communities who benefitted from funded projects is definitely greater than the number stated in the map above, though it cannot be calculated, as the location of projects directly funded by the Canada 150 Fund and those funded via the CFC’s Community Fund for Canada’s 150th may overlap.

Community Fund for Canada’s 150th

Community Foundations of Canada (CFC) received approximately $7.9 million from the Canada 150 Fund to implement the Community Fund for Canada’s 150th. The funding was distributed to 176 community foundations across Canada, who matched the funds and awarded micro-grants (of up to $2,000) to community organizations to implement projects aligned with the government’s objectives for Canada 150 and their community needs. The Fund sought to encourage participation; build deeper understanding of our history; and build communities including youth, ethnocultural and racialized communities, Indigenous Peoples, and official language minority communities.

Evaluation question: to what extent did Canada 150 projects engage Canadians and contribute to vibrant Canadian communities?

Key finding: based on available data on partnerships, volunteerism, and participation rates, there was a high level of engagement among Canadians in Canada 150 events. Similarly, the Canada 150 activities were generally considered to contribute, though to varying extents and through different mechanisms (including community engagement), to vibrant communities.

Engagement

Engagement in Canada 150 events was estimated using three primary metrics: volunteerism (number of volunteers and hours); partnerships (including financial and in-kind support); and participation in events.

Volunteerism

There was a high level of volunteer engagement in projects funded through the Canada 150 Fund. Based on the GCIMS internal database, which includes records for 570Footnote 12 Signature projects, Major Events, and Community-driven projects which reported on this measure, over 158,000 volunteers contributed over 5.3 million volunteer hours to 570 projects. However, the number of volunteers varied substantially by project, from 0 to over 30,000. Table 10 summarizes available GCIMS volunteer participation data, by type of event. In addition, 6% of Wave III POR respondents indicated that they had volunteered for a Canada 150 community event, activity, or initiative. This high level of volunteerismFootnote 13 suggests a high level of engagement of Canadians with Canada 150 celebrations.

| Type of event | # of events reporting | # of volunteers | # of volunteer hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signature | 41 | 87,606 | 4,713,175 |

| Major/Anchor | 41 | 4,495 | 60,874 |

| Community-driven | 489 | 66,099 | 599,326 |

| Total | 571 | 158,200 | 5,373,375 |

Source: GCIMS, November 27, 2018 and January 30, 2019.

Volunteers supported a variety of activities, including celebratory or commemorative activities, community-building activities and events, large-scale artwork projects, and theatrical or musical performances, productions, and/or compositions.

Similarly, the survey of funding recipients demonstrates that considerable support of Canada 150-funded projects was provided by volunteers.Footnote 14 A higher maximum number of volunteer hours associated with projects without Canada 150 funding could suggest that organizations were able to offer more paid hours of work as a result of this funding.Footnote 15

Furthermore, the projects funded through the CFC’s Community Fund for Canada’s 150th had large numbers of volunteers. Based on project reporting, over 100,000 volunteers were engaged in the 2,124 projects that received grants (95% of which included a volunteer component).Footnote 16

In contrast, key informants differed in their estimations of the extent to which Canada 150 activities encouraged volunteerism and indicated that volunteerism varied widely between funding recipients. While data on the number of volunteers and their contribution was required in project final reports, some funding recipients did not track that information throughout the year. For those who commented on volunteerism, the primary findings are summarized below.

- Larger projects reported having record numbers of volunteers that were integral to the success of the event (e.g., SESQUI, Rendez-vous naval de Québec [RVNQ], Tree to our Nature, Winnipeg Art Gallery). Some smaller projects (e.g., museums or education-oriented organizations) noted fewer volunteers.

- A few recipient organizations indicated that the additional funding provided by Canada 150 allowed them to organize events to thank volunteers for their support (e.g., hosting a movie and pizza night).

Partnerships

The projects receiving funds through the Canada 150 Fund often included a partnership component. Based on GCIMS data, most of the projects had partnerships or collaborative arrangements with stakeholders who provided financial and/or in-kind support. These partners included foundations (e.g. the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, the Terry Fox Foundation), chambers of commerce and business councils, banks and insurance companies (e.g. Manulife, TD Bank), media outlets (e.g. Sun FM radio, Journal Le Tartan), academic institutions, private businesses (e.g. Bell Canada, Dulux Paints), and artist guilds. Data on the amount of partners’ financial contributions was provided for 174 projects, including:

- 25 Signature initiatives out of 41 (received $29,616,309);

- 28 Major events out of 45 (received $2,951,825); and

- 121 Community-driven projects out of 635Footnote 17 (received $28,059,666).

In addition, 289 out of 635 community events and 25 out of 41 Signature projects indicated they had received in-kind support. This support primarily included:

- advertising and promotion;

- content development;

- staff and logistical support for planning and running events;

- facilities;

- food and hospitality;

- audio, visual, and information technology support; and

- performer and artist time.