Evaluation of the Creative Export Strategy 2018-19 to 2020-21

Evaluation Services Directorate

Janaury 20, 2023

On this page

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Creative Export Strategy profile

- 3. Approach and methodology

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations, management response and action plan

- Annex A: CEF’s expected outcomes, performance indicator(s) and target(s)

- Annex B: evaluation framework

- Annex C: creative sectors and sub-sectors

- Annex D: bibliography

List of tables

- Table 1: creative Export Strategy activities and planned 5-year expenditures by pillar

- Table 2: expected outcomes of the Creative Export Fund

- Table 3: creative Export Fund spending, 2018-19 to 2020-21 ($ actual)

- Table 4: evaluation questions by core issue

- Table 5: evaluation limitations and mitigation strategies

- Table 6: representation of creative sectors among CEC recipients and TM participants, 2018-19 to 2020-21

- Table 7: representation of creative sectors among CEC funded recipients, 2018-19 to 2020-21

- Table 8: actual and projected benefit cost ratio of CEC funded projects, 2018-19 to 2020-21

- Table 9: financial value of B2B meetings during 3 trade missions excluding China TM

- Table 10: potential commercial agreements resulting from sample international amplification events

- Table 11: potential commercial agreements resulting from sample domestic amplification events

- Table 12: planned CEF expenditures ($ millions), 2018-19 to 2020-21

- Table 13: actual CEF expenditures ($ millions), 2018-19 to 2020-21

- Table 14: satisfaction with sample ITO amplification events for international amplification events

- Table 15: satisfaction with sample ITO amplification events for domestic amplification events

- Table 16: recommendation 1 – action plan

- Table 17: recommendation 2 – action plan

List of figures

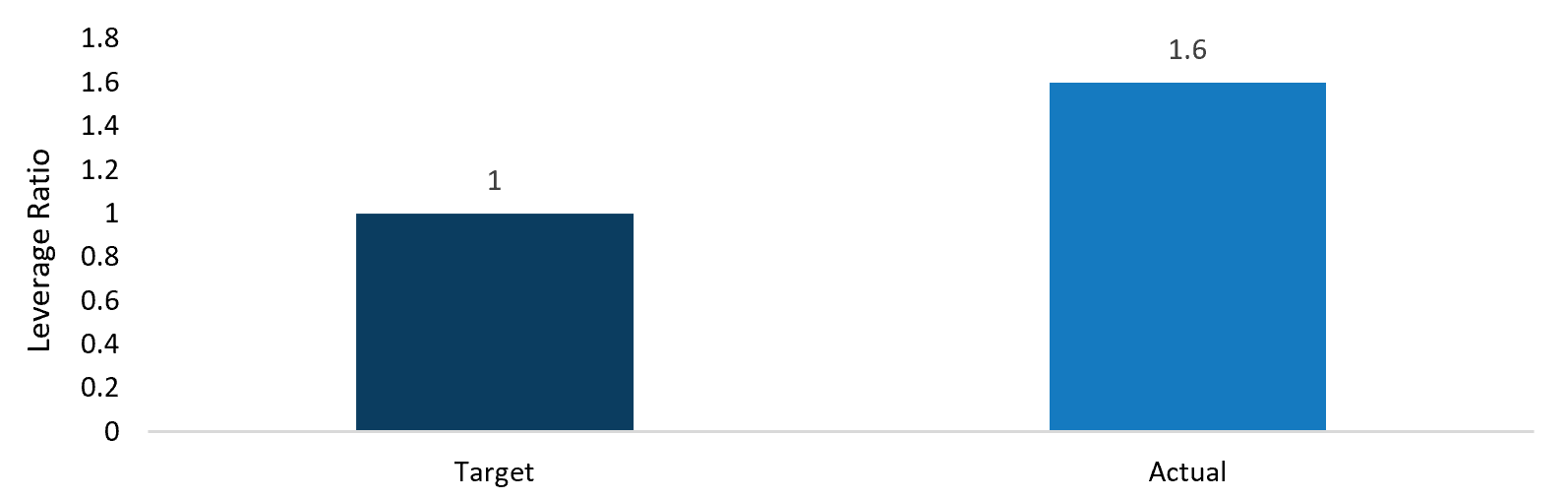

- Figure 1: leverage ratio of funding committed by CEC funding recipients, 2018-19 to 2021-21

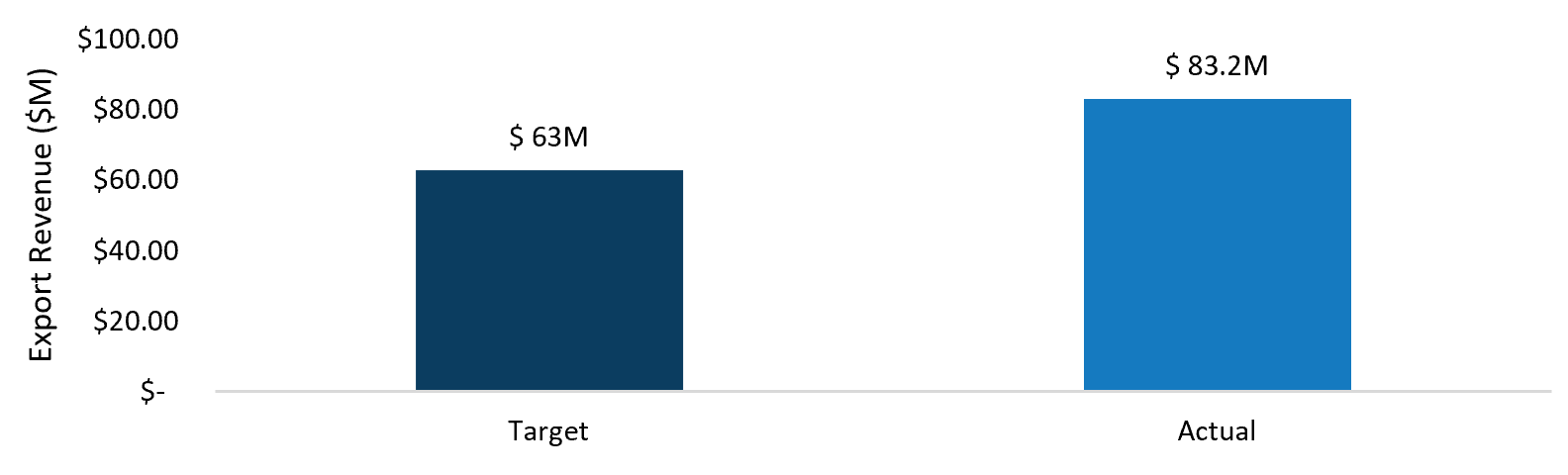

- Figure 2: actual versus target export revenues of CEC funded projects, 2018-19 to 2020-21

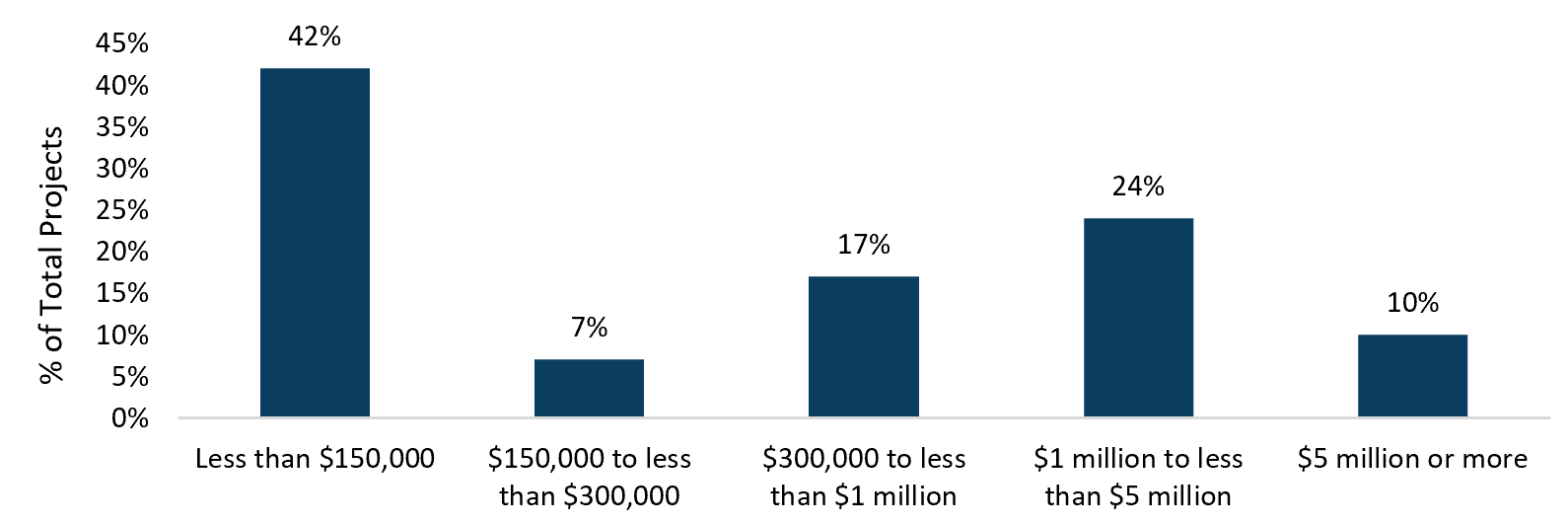

- Figure 3: analysis of actual export revenues of CEC funded projects, 2018-19 to 2020-21

Alternate format

Evaluation of the Creative Export Strategy 2018-19 to 2020-21 [PDF version - 1 MB]

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- B2B

- Business to business

- CEC

- Creative Export Canada

- CEF

- Creative Export Fund

- CES

- Creative Export Strategy

- EBP

- Operating and Employment Benefit Plan

- ESD

- Evaluation Services Directorate

- F/P/T

- Federal, provincial, and territorial

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GCIMS

- Grants and Contributions Information Management System

- GFK

- Growth from Knowledge

- Gs&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- HUB

- Resource Management Services (internally named the HUB)

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- IT

- International trade

- ITO

- International trade operations

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- PCH

- Canadian Heritage

- PIP

- Performance Information Profile

- PSPC

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- ROI

- Return on investment

- TC

- Trade Commissioners

- TCS

- Trade Commissioner Services

- TM

- Trade mission

Executive Summary

Program description

The evaluation focused on Creative Export Canada (CEC) and International Trade Operation (ITO) activities which are components of the Creative Export Fund (CEF) and are part of the overall Creative Export Strategy. The goal of the CEC is to fund a limited number of projects undertaken by for-profit and non-profit organizations in the creative sector that have the potential to generate significant export revenues. ITO activities are geared to facilitate business deals and generate export revenues by the Canadian creative sector through undertaking trade missions (TMs), amplification events, export seminars, and partnerships with other government counterparts.

Evaluation approach and methodology

The evaluation used a mixed-methods approach including a document and administrative data review, literature review, interviews, and case studies. 31 interviews were conducted with PCH officials and CEC funded and unfunded applicants. The 2 TMs selected for case studies were the in-person Latin America TM (2019) and the virtual Germany TM (2021). As part of the case studies, interviews were conducted with 3 trade commissioners (TC) from Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and 10 TM participants.

Findings

Relevance

There is an ongoing need for the CEF. The evaluation finds that the CEF is relevant because exports are critical to the continued growth of the creative sector. Government support is needed to assist the sector in increasing its export activities due to difficulties in accessing international marketplaces and the lack of resources to develop and implement export marketing strategies. While the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant negative impact on the creative sector, the CEF has responded by adapting its delivery to changing needs, including those related to the pandemic.

The CEF aligns with federal and departmental priorities, particularly regarding the promotion of international trade (IT) and promotion of the creative sector. While the CEF considers federal government commitments related to equity communities, the evaluation finds that there are opportunities to improve data related to equity communities to better support decision-making and reporting.

Although there are a variety of other federal, provincial, and territorial programs that address similar needs, efforts have been made to avoid duplication and ensure that CEC and ITO activities each meet distinct needs.

Effectiveness

The CEF had made progress in achieving its intended short-term outcomes to increase export activities.

CEC provided funding of $22.2 million to 48 for-profit and non-profit organizations to undertake export projects. ITO increased international promotion of the sector through a variety of activities and engagement activities including 4 TMs, 3 exploratory TMs, 36 amplification events, 9 export seminars and the establishment of 1 formal partnership.

The CEF has made considerable progress in achieving its intended medium-term outcomes related to increasing export revenues but there exist opportunities for improvement. The export revenues generated to date by CEC funded applicants are $83.2 million, which is higher than targeted. However, most of this amount is due to only 3 projects and the export revenues are less than the project costs for two thirds of CEC funded projects, which suggest opportunities to better align the funding decision process with CES objectives and priorities to further increase export revenues. The 4 ITO TMs contributed to 88 potential business deals/commercial agreements. There were 54 commercial agreements signed or in advanced negotiations from a sample of 7 amplification events. CEC met its target for overall funding ratio with a ratio of $1: $1.6.

Canada ranked in 5th position for the Growth from Knowledge (GFK) Nation Branding Exports Index in 2021 which is the same ranking achieved in 2018. For the GFK Nation Branding Cultural Index, Canada was ranked in 10th position in 2021 which is higher than the 12th position ranking in 2018.

Performance Measurement

The evaluation finds that the performance measurement information is useful for decision-making to some extent. There is a performance strategy in place and results data are being collected. A number of gaps were identified, notably:

- short timelines for data collection do not allow the achievement of all immediate and medium-term outcomes, especially since export revenues take longer to achieve;

- performance data is not consistently collected, compiled, and reported including data related to equity communities; and

- definitions as well as limitations in the performance measures are not always clear to stakeholders.

Efficiency

While there is evidence of good management practices in the delivery of CEC and ITO activities, the evaluation notes some challenges. There is an opportunity to improve program delivery by reducing the time required to make CEC funding decisions, as the PCH service standard of 26 weeks was achieved only 34% of the time and by providing more clarity on funding priorities and eligibility criteria.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The evaluation recommends that the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Cultural Affairs review and update the CEF logic model and performance measurement indicators, to support consistent data collection and reporting, as well as to better capture intermediate and long-term economic impacts and to improve data on equity communities.

Recommendation 2

The evaluation recommends that the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Cultural Affairs, should implement measures to streamline and enhance the CEC funding decision process.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of PCH’s Creative Export Strategy (CES). The evaluation was carried out as indicated in the Department of Canadian Heritage (PCH) Evaluation Plan, 2018-19 to 2022-23, and conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016), the Directive on Results (2016) and the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation of the CES covers the three-year period from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2021. It addresses issues relating to relevance, efficiency, and effectiveness. It focuses on the Creative Export Fund (CEF), which is the third pillar of the CES.Footnote 1

2. Creative Export Strategy profile

Canada committed $35 million over 2 years in its 2016 budget to support Canadian artists and the creative sector in the expansion of their markets internationally. From 2016-17 to 2017-18, PCH, GAC and Telefilm CanadaFootnote 2 used this funding to support activities that promoted Canadian artists and the creative sector abroad and helped Canadian missions promote Canadian culture and creativity on the world stage. Part of the funding was used to develop, launch and implement the CES.

The CES was launched in June 2018 with an investment of $125 million over 5 years (2018-19 to 2022-23). The aim of the CES is to provide businesses and entrepreneurs in the creative sectorFootnote 3 with the resources needed to expand in foreign markets and maximize their export potential. As shown in Table 1, the CES has 3 pillars of activities. The CEF forms the third pillar of the CES and is supported by $70 million in funding over a period of 5 years.

| Pillar | Planned Expenditures | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1st pillar | $25M | Boosting export funding in existing PCH programs (Canada Arts Presentation Fund, Canada Book Fund, Canada Music Fund, Canada Periodical Fund) and Telefilm Canada to position the creative sector for exports in foreign markets. |

| 2nd pillar | $30M | Increasing and strengthening the presence of the Canadian creative sector abroad with investments made by GAC. |

| 3rd pillar- CEF | $70M | Growing creative sector by:

|

Source: CES original documentation

2.1. Creative Export Fund expected outcomes and activities

2.1.1. Expected outcomes

Table 2 below describes the short, medium, and long-term outcomes of the CEF.Footnote 4 More details related to the indicators and targets for each expected outcomes can be found in Annex A.

| Timeframe | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Short-term |

|

| Medium-term |

|

| Long-term |

|

Source: CES original documentation

2.1.2. Activities

Creative Export Canada

The CEC is a grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) program that aims to grow the creative sector through export. It is designed around 3 key principles:

- Performance: The program funds projects that have a high ROI potential.

- Flexibility: The program is intended to be neutral, meaning that it does not discriminate against any creative sector, it does not have a funding envelope allocated to any particular sector, and is open to all companies working in the Canadian creative sector.

- Complementarity: Given the many programs that support Canadian export activities, the program consults with existing programs to ensure that there is no duplication of funding.

To achieve the best possible ROI, CEC is designed to fund a limited number of high-potential projects (approximately 20 projects per year). To be eligible for CEC funding, applicants must: be a for-profit or not-for-profit organization; have a maximum of $500 million in annual revenues; have a minimum of one full-time employee; and be Canadian-owned and controlled.

For the period covered by this evaluation, eligible projects had to:

- expect to generate new export revenues;

- have a minimum total cost of $300,000Footnote 5;

- be export-ready, meaning content is ready to be marketed and that the export research or plan is fully developed;

- hold the intellectual property rights for content; and

- have a direct impact on at least one of the following creative sectors: audio-visual and interactive media, sound recording, live performance, publishing (books and periodicals), as well as visual and applied arts (exhibit, fashion, product, public art and urban).

CEC is delivered through a competitive funding process. Two calls for proposals were undertaken in 2018-19 and one per fiscal year was issued in the following years. Applicants are required to complete an application form that includes a description of the expected outcomes, and the impact of the project on the Canadian creative sector. CEC uses a scoring grid to determine whether a project will be recommended for funding. CEC also consults with internal and external partners, including GAC, other PCH funding programs and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) to determine, for example, the feasibility of a project, potential issues, and the capacity to provide support abroad.

A maximum of 2 years of funding is offered to support larger-scale projects/multi-year projects.

International Trade Operations

ITO is responsible for the following 4 activities: TMs, amplification events, export seminars, and partnerships with international government counterparts. These activities are funded by operations and maintenance (O&M) expenditures. ITO counts on partnerships and collaboration with GAC’s Trade Commissioner Service (TCS) to assist in the planning and/or the delivery of the international activities such as TMs and international amplification events.

Trade Missions

ITO is responsible for the planning, coordination, and delivery of multi-sectoral TMs for Canada’s creative sector. The TMs consist of 2 parts: the first part is a governmental program where bilateral meetings are organized with governmental counterparts of the country where the TM is taking place; and the second part is a commercial program where bilateral meetings are organized with a delegation of Canadian companies from the creative sector to meet potential buyers of the country where the TM is taking place.

The delivery of the bilateral meetings with governmental counterparts advances the “partnerships” portion of ITO’s mandate, in addition to allowing for the discussion/advancement of priority files for PCH at the international level as well as discussing the challenges and risks the Canadian creative sector may face in various markets.

As for the commercial program, once a TM is selected, a call for applications is launched approximately 4 to 5 months prior to the mission. Potential TM participants must apply through a competitive process. The application is evaluated on a scoring grid based first and foremost on its export-ready status. Should the applicant meet this requirement, diversity and inclusion factors are also considered in the evaluation process (e.g., Indigenous-led or focus, diversity-equity-inclusivity, or women-led or focus). The TM costs covered by ITO include fees related to all components of the business programFootnote 6, where applicable. TM participants are responsible for their travel costs and expenses. No registration fee is required.

Amplification Events

Amplification events include B2B meetings and networking opportunities at sector-specific international or domestic events, conferences, trade shows and trade fairs with an international trade focus.Footnote 7 ITO’s role regarding the amplification events varies from one event to another and can include:

- providing funding to event organizers, consultants or the Trade Commissioners (TC) to cover costs related to the organization of B2B meetings between Canadian participants and potential international buyers or partners;

- participating in the planning of the program elements, including advising on the type of activities to be conducted, requesting a post-event report on results, and ensuring the conduct of a post-participation survey;

- participating and /or providing in-person support during B2B activities; and

- coordinating the recruitment of Canadian participants who will benefit from the business program supported during the selected international events.

Export Seminars

ITO plans and delivers export seminars for creative sector businesses across Canada to promote the CES programs and activities and build export capacity and readiness by inviting and presenting other federal, provincial or territorial (F/P/T) government departments and non-governmental organizations activities and funding programs.

Partnerships

ITO is responsible for establishing partnerships with international government counterparts to facilitate and enhance bilateral trade and collaboration in the creative sector. This includes government-to-government exchanges with counterparts in other countries and providing input on high-level bilateral discussions on trade in the creative sector.

Frankfurt Book Fair Initiative

This initiative was responsible for leading the preparation for Canada’s Guest of Honor presence at the Frankfurt Book Fair that took place virtually in 2020 and in person in 2021. It focused on:

- ensuring a strong presence for Canada as Guest of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair;

- creating trade opportunities for the creative sector; and

- establishing a cultural exchange network between Canada and German-speaking countries by showcasing and raising awareness of Canadian expertise in several creative sub-sectors.

2.2. Program management and governance

The IT Branch, within PCH’s Cultural Affairs sector, is responsible for the delivery of the CEF. The IT Branch is dedicated to advance the interests of Canada’s creative sector internationally through CEC and ITO’s activities. The responsibilities of the IT Branch include:

- overall policy coordination and cohesion of the CES;

- market research and data analysis to ensure effective implementation of the CEF;

- coordination of TM, amplification events, and international partnerships;

- administration of CEC contributions program; and

- collecting existing data and reporting on the results achieved by the CES initiatives by working with GAC, other PCH program areas, and Telefilm Canada.

A PCH-GAC director general committee is established to exchange information on results, discuss planning documents and align funding activities. Committee meetings are held at least once a year.

2.3. Program resources

As outlined in Table 3, actual spending on the CEF was approximately $40.6 million including salaries, operating and Employment Benefit Plan (EBP) costs, O&M expenditures, and Gs&Cs expenditures from 2018-19 to 2020-21. During this three-year period, Gs&Cs expenditures totalled $22.5 million, or 55% of total spending.

| Expenditures ($) | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salaries | 2,189,865 | 2,637,856 | 2,861,516 | 7,689,237 |

| Operating and Employment Benefit Plan (EBP) | 437,973 | 712,221 | 772,609 | 1,922,803 |

| Operating and maintenance (O&M) | 2,196,977 | 3,595,579 | 2,691,785 | 8,484,341 |

| Grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) | 7,788,750 | 7,170,955 | 7,500,000 | 22,459,705 |

| Total | 12,613,565 | 14,116,611 | 13,825,910 | 40,556,086 |

Source: PCH Financial Management Branch

3. Approach and methodology

The evaluation was led by PCH’s Evaluation Services Directorate (ESD), with consultant support. This section outlines the evaluation approach and methodology including scope, timelines, calibration, evaluation questions, data collection methods, limitations, and mitigating strategies.

3.1. Scope, timeline, and quality control

As the current CES expires in March 2023 and is in the process of being renewed, the evaluation focused on the CEF activities during the three-year period from April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2021 as established in the CES original documentation, with specific attention paid to CEC, ITO, and IT policy activities related to the CES performance data. The evaluation does not include the CEF activities related to preparations for Canada’s Guest of Honour virtual presence at the Frankfurt Book Fair or the CES Pillar 1 or 2 activities.Footnote 9

The scope and questions for this evaluation were identified through consideration of policy requirements and senior management needs. Scoping interviews held during the planning stage with program representatives identified the following information needs:

- CEF successes and areas of improvements;

- continued need for the CEF;

- alignment with federal government priorities and PCH objectives;

- efficiency and usefulness of performance data; and

- possible program improvements.

In addition to these areas of program interest and as outlined in its 5-year Evaluation Plan, 2021-22 to 2025-26, PCH is also committed to examining horizontal questions related to equity-deserving groups (hereafter referred to equity communities), as well as those related to the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on program delivery.

ESD conducted the work in a neutral manner and with integrity in its relationships with stakeholders. The following quality assurance measures were undertaken during the evaluation:

- A combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods was used to provide a deeper understanding of CEF results.

- Multiple sources of primary and secondary data were used to ensure that findings are reliable.

- A triangulation session was held to validate the findings across the different data collection methods, and by evaluation questions. The results of the triangulation guided the conclusions and the evaluation recommendations.

3.2. Calibration

Given CES renewal, this evaluation was undertaken on an accelerated process to provide useful information for their renewal. Therefore, calibration was considered in the following areas:

- The data collection was collected in a short timeframe.

- A reduced number of evaluation questions was employed, and effort was focused on the key needs identified by the program’s senior management.

- As much as possible, the evaluation team leveraged existing data sources, such as program performance data and documents, and literature.

- A sample of documentation was reviewed and reported for amplification events, as overall performance data was not compiled by fiscal year.

- Targeted data collection was undertaken to address key information gaps. The lines of evidence were chosen to target specific areas of inquiry, to cross-reference questions, and validate any findings during triangulation.

- The format of the report was streamlined.

3.3. Evaluation questions

The evaluation questions are shown in Table 4. These questions guided the evaluation, including the development of data collection instruments and the analyses. More details related to the indicators, data sources and data collection methods can be found in the Evaluation Framework (Annex B).

| Core issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance |

|

| Effectiveness |

|

| Efficiency |

|

3.4. Data collection methods

The evaluation’s data collection took place from October 2021 to July 2022. The methodology involved a mixed-methods approach and relied on both primary and secondary sources of information. The data collection included a document and administrative data review, a literature review, interviews, and case studies. The following sub-sections describe each of the data collection methods in greater detail.

3.4.1. Document and administrative data review

The ESD reviewed more than 400 documents including: PCH and federal government documentation; the CES documentation, decks, research and analyses conducted by the IT policy team; CEF documentation including consultations with the creative sector; CEC documentation including guidelines, application forms, dashboards and decks; and ITO documentation including post-participation survey results, decks and reports on TMs, sampling of amplification events and creative export seminars.

The administrative data review consisted of an examination of the administrative files and financial information provided by the program and by PCH Financial Management Branch to address related evaluation questions and indicators. This included an examination of Grants and Contributions Information Management System (GCIMS) data to obtain information related to the CEC applications received, and projects funded.

3.4.2. Literature review

The literature review included academic and grey literature, news media, reports, and government and organization web content related to current creative sector and export issues. A targeted search was conducted to address each relevant evaluation question and indicator.

3.4.3. Interviews with program representatives and CEC applicants

31 virtual interviews were conducted with PCH officials and CEC funded and unfunded applicants.

- 9 PCH CEF representatives interviewed were with CEC, ITO, IT Policy and senior management.

- 4 PCH representatives interviewed were from the following first pillar programs: Canada Arts Presentation Fund, Canada Book Fund, Canada Music Fund and Canada Periodical Fund.

- 18 CEC applicants were interviewed, which included 10 funded applicants, 5 unfunded applicants and 3 applicants that received funding for at least one application as well as being denied funding for other applications. Different criteria were considered while selecting CEC applicants including: the fiscal year of the application, the creative sector, one year and multi-year funding requests and the range of funding requested.

3.4.4. Case studies

Case studies were conducted to analyze the activities and outcomes of 2 creative sector TMs: the in-person Latin America TM (February 10-19, 2019) and the virtual Germany TM (March 23-25, 2021).

As part of the case studies, virtual interviews were conducted with 3 Trade Commissioners from GAC due to the important role they played in the mission planning and delivery and 10 participants from Canadian organizations that participated in these TMs. The TM participants were from a variety of sectors. As part of the case studies, documents were also reviewed including:

- event summary presentations and reports;

- delegation lists and applicant information;

- mission overview materials, briefs, and planning documentation; and

- TM post-participation survey data and results.

3.4.5. Reporting scale

The following legend was used throughout the report to indicate the proportion of individuals interviewed or survey respondents that responded in the same manner:

- Few: findings reflect less than 25% of the observations.

- Some/several: findings reflect at least 25% but less than 50% of the observations.

- Half: findings reflect 50% of the observations.

- Majority: findings reflect more than 50% and less than 75% of the observations.

- Most: finding reflect 75% but less than 90% of the observations.

- All/almost all: findings reflect 90% or more of the observations.

3.5. Limitations and mitigation strategies

The key limitations of the evaluation as well as the corresponding mitigation strategies employed by the evaluation team are described in Table 5.

| Limitations | Mitigation strategies |

|---|---|

| The CEC applicants interviewed did not represent all creative sectors and sub-sectors, as the interviews were accepted on a volunteer basis. A high proportion of respondents who accepted participating in the interviews were from the performing arts sub-sector. | Other sources of data including interviews with program representatives along with the document and administrative data review encompassed all creative sectors and sub-sectors. |

| Due to the short timeframe of the evaluation, the evaluation team did not interview creative sector organizations participating in the amplification events and it only reviewed a sample of domestic and international amplifications events documents. | Other sources of data including interviews with PCH and GAC representatives involved in the amplification events, a document and data review as well as a literature review were employed to address this constraint. |

| Challenges were encountered with ITO’s TM post-participation survey data, including low or inconsistent response rate and changes to survey questions from year to year. | Where possible, relevant survey findings were summarized, including specifications of the changes in questions over time. Survey findings were validated using other lines of evidence, including interviews. |

| Some F/P/T or municipal government programs with objectives related to creative export may not have been included in the assessment of complementarity and duplication if information was not publicly available. | The literature review cast a broad net, and multiple search methods were utilized to identify related programs. The number of comparative programs found was deemed sufficient for assessing complementarity and duplication, and the evaluation findings regarding this topic were developed in consideration of other lines of evidence, including interviews with program representatives and CEC applicants. |

| Given that the CEF was created in 2018-19, the evaluation had limited access to impact measures associated with long-term economic outcomes. | The evaluation focused on the CEF short- and medium-term results. |

4. Findings

4.1. Relevance

This section presents a summary of findings regarding the evaluation questions related to relevance.

4.1.1. Relevance: ongoing need for the program

Evaluation question: To what extent did the CEF address continued and changing needs?

Key findings:

- There is an ongoing need for the CEF activities.

- The creative sector is a growing economic driver and export is critical to continued growth. Government support is needed to assist the sector in increasing export. The demand for the CEF activities outweighs available supports. There is a variation in the extent to which CEC applicants and TM participants represent different regions, creative sectors and organization types.

- The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant negative impact on the creative sector. Nevertheless, the CEF demonstrated abilities to adapt its delivery to changing needs, including those related to the pandemic.

The creative sector is a growing economic driver and there exists a need for the CEF activities

Between 2010 and 2020, the Canadian culture sector grew at an average annual rate of about 2%. By 2020, it had generated $55.5 billion in direct gross domestic product (GDP), which was 2.7% of Canada's total GDP.Footnote 10

Government support for exporting is important to support sector growth

The Canadian creative sector must export to grow. CEC applicants and TM case study participants stated it is critical for the Canadian creative sector to undertake export activities to grow because of the small size of the Canadian market relative to global markets. Furthermore, CEC applicants and TM case study participants stated that the need for CEF support will increase in the future because of the importance of globalization and an increased reliance on global partnerships and worldwide audiences.

Almost all CEC applicants and TM case study participants interviewed indicated that government support for exporting was required to a “very great extent” or to a “great extent”. The most frequent reasons noted the following rationale for government support:

- Lack of resources or capacity (financial and human) to develop and implement export marketing strategies.

- Difficulty in accessing international marketplaces.

- Government support brings a degree of credibility to Canadian businesses in international and national markets.

- Need for market intelligence/navigation.

The literature review indicated that there is a need for 2 main types of government support to realize export growth opportunities and address barriers experienced by Canadian creative organizations: financing initiatives, such as Gs&Cs or loans; and activities to facilitate networking with international buyers and increase visibility.Footnote 11, Footnote 12, Footnote 13, Footnote 14

There is a high demand for the CEF activities

The CEF is not able to meet all application requests. CEC received 435 applications during the evaluation period, of which only 48 export projects (12%) were funded and, TM received 458 applications of which 148 were accepted (32%).

The CEF support is distributed among regions, creative sectors, and organization types

Funded CEC applicants and TM participants are primarily concentrated in 3 regions: Quebec (52% CEC, 27% TM), Ontario (31% CEC, 38% TM) and British Columbia (8% CEC, 16% TM). Some literatureFootnote 15,Footnote 16 suggests that rural communities/regions may face heightened support needs due to factors including restricted access to markets and skilled labour. As indicated in Table 6, certain creative sectors are more represented among CEC funded applicants and TM participants. Live performance, audiovisual and interactive media and multi-sector for CEC are the most frequently represented sectors while the visual and applied arts, sound recording, and written and published works are the least frequently represented sectors. Footnote 17

| Creative sector | % of CEC funded recipients | % of TM participants |

|---|---|---|

| Live performance | 33% | 29% |

| Audiovisual and interactive media | 19% | 27% |

| Visual and applied arts | 8% | 6% |

| Sound recording | 6% | 8% |

| Written and published works | 6% | 12% |

| Multi-sectoral | 28% | - |

| OtherFootnote 18 | - | 18% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

Sources: Administrative data (program compilation), ESD- ITO compilation list and data in TABLEAU (database used by CEF)

As indicated in Table 7, representation of certain creative sectors among CEC funded applicants changed over the 3 years evaluated. The audiovisual and interactive media sector experienced the most growth, multi-sectoral projects grew over time, whereas the funding provided to the live performance and sound recording sectors declined. However, trends in program demand over time have likely been impacted by the pandemic as detailed further in this section.

| Creative sector | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live performanceFootnote 19 | 45% | 59% | 0% | 33% |

| Audiovisual and interactive media | 10% | 17% | 31% | 19% |

| Visual and applied arts | 5% | 8% | 13% | 8% |

| Sound recording | 10% | 8% | 0% | 6% |

| Written and published works | 10% | 0% | 6% | 6% |

| Multi-sectoral | 20% | 8% | 50% | 28% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: Administrative data (program compilation)

Some CEC applicants interviewed stated that the need for financial support is less for some sectors (e.g., audiovisual and interactive media such as multi-media, gaming, special effects, cinema, TV companies) because they are subsidized while the greatest need for support exists among sectors such as the live performance and visual and applied arts sectors which lack access to funding or support.

Most CEC funded applicants consisted of for-profit organizations while the remainder consisted of non-profit or charitable organizations. The provision of most of the funding to for-profit organizations is reflective of the limited mandate and lack of capacity of most non-profit organizations to raise financing and lack of retained earnings to participate in export-ready projects.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant negative impact on the creative sector

The pandemic resulted in the delay or modification of many CEC funded projects. Most funded applicants reported disruptions to their operations and workflow, due to changing personnel needs and shifting to digital delivery and distribution. Almost one half of CEC applicants indicated they curtailed or reduced their exporting activity because there were fewer opportunities to meet international buyers in a face-to-face setting. Cancellation of in-person events resulted in a shift to digital delivery and adjustment to revenue models, particularly for venue and performance-based sectors and sub-sectors, while the audiovisual and interactive media sub-sectors benefited from restrictions related to the pandemic.

The CEF deployed strategies to address changing needs and realities due to COVID-19 pandemic

Most PCH officials interviewed felt that the CEF responded to changing needs related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The program did this by allowing for flexibility and by shifting activities to virtual environments. This included providing CEC applicants with the opportunity to revise their application to account for pandemic developments, and 60% re-submitted their application. ITO’s activities (such as TMs and seminars) shifted to virtual delivery. Almost all post-participation survey respondents who attended a virtual TM felt that virtual delivery was a valuable alternative to in-person events.

Increased demand for digital content, such as streaming services, was the emerging trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic most frequently noted by CEC applicants. A few respondents stated that some organizations, particularly those in the live performance sector, were experiencing difficulties in adapting to the trend towards digital production. Other trends noted include higher costs related to supply chains, shipping and travel, human resources challenges and less demand for touring due to sensibilities related to climate change.

4.1.2. Relevance: harmonization with government priorities and PCH core responsibilities

Evaluation question: To what extent does the CEF align with federal government and PCH priorities, roles and responsibilities?

Key findings:

- Overall, the CEF aligns with federal and departmental priorities, particularly regarding the promotion of international trade and promotion of the creative sector.

- To some extent, the CEF considers federal government commitments related to equity communities. There are gaps in data related to equity communities that could be used to better support decision-making and reporting.

The CEF aligns with federal and departmental priorities

PCH Departmental Plans for 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21 state that the CEF contributes to PCH’s Core Responsibility #1: Creativity, arts, and culture by ensuring that the creative sector is successful in global markets resulting in an increase in the value of creative exports. Also, the Prime Minister of Canada’s mandate letter to the Minister of Canadian Heritage on August 28, 2018, reinforces this priority. It states that “Our cultural sector is an enormous source of strength to the Canadian economy. I will expect you to work with your colleagues and through established legislative, regulatory, and Cabinet processes to deliver on your top priorities such as lead in the delivery of the Creative Export Strategy with the support of the Minister of Small Business and Export Promotion.”

The CEF considers federal government commitments to equity communities

In recognition of government priorities, the CEF took measures to ensure supports for equity communities through application review processes. For example, since 2020-21, additional points are given to projects where diversity and inclusion considerations are identified in CEC and ITO applications. This could include CEC applications from organizations that are Indigenous or women-led or focused. Prior to that time, for projects with the same scoring, projects having equity communities’ considerations were more likely to be approved. This rationale is also used to assess TM applications.

However, some PCH officials indicated that while efforts have been made to address the needs of equity communities, progress has been limited. For example, the CEF does not systematically compile data on participation by equity communities, limiting ability for strategic planning and reporting. The evaluation notes that more recent efforts, outside the scope of this evaluation, have been made to provide better access to equity communities. For example, ITO’s funding for the Hot DocsFootnote 20 amplification event in 2022, supported the participation of underrepresented filmmakers and producers by covering the cost of 10 passes, thus removing financial barriers for these emerging filmmakers/producers.

4.1.3. Relevance: duplication or complementarity with other programs

Evaluation question: To what extent did the CEF duplicate or complement other programs delivered through PCH, other government departments (F/P/T), non-governmental or the private sector?

Key findings:

- The CEF complements other government programs.

- While there are a variety of other F/P/T programs that address similar needs, efforts have been made to avoid duplication and ensure that CEC and ITO activities each meet distinct needs.

Efforts have been made to avoid duplication

A review of the CEF landscape found over 40 programs offered by F/P/T governments as well as other organizations that address somewhat similar needs. These other programs vary in scope and eligibility and differ across provinces and territories and creative sectors. The most common outputs include the following: financial assistance; guidance/advisory services; and networking and promotion support.

Duplication with other programming was not evident, mostly due to strong collaboration and communication. Most CEC applicants and PCH officials stated the CEC program is complementary to other programs including those offered by other F/P/T and municipal governments. The literature review indicated that the other programs that provide support for international promotion, networking, and relationship building are delivered primarily by the federal government, specifically by GAC, PCH, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). Some PCH officials indicated that the CEF works jointly with GAC and other PCH programs and consults with subject matter experts to understand the CEF landscape and minimize duplication.

The CEC meets distinct needs

The CEC differs from other programming in several ways. Most CEC applicants interviewed stated that, compared to other programs, the CEC provides a larger amount of contribution funding per project for export-ready organizations rather than small awards and loans. They also stated that the CEC has broader eligibility criteria. These factors result in a greater impact in terms of visibility in international markets, securing sales, and accessing new networks. Compared to other PCH programs assessed for complementarity or duplication, the CEC program allows PCH to reach new clients from sub-sectors that were not previously eligible through other PCH programs to apply for funding, such as design and interactive media. According to the literature review, PCH programs as well as Ontario programsFootnote 21 tend to reflect greater consideration of equity communities compared to other programs.

The ITO also meets distinct needs

The cross-sectoral approach employed by TMs is perceived as unique and has resulted in synergies between creative sectors. For example, with multi-sectoral TM participants, some projects overlapping multiple sectors could be initiated, such as adaptations of books to TV series or movies, and music for movies. Most TM participants and government officials indicated the government-led approach to the PCH-led TMs also legitimizes and enhances the credibility of the participant organizations. As well, most TM participants emphasized that having opportunities for dialogue and relationship building with government counterparts is a unique and valuable aspect of the PCH-led TMs. A few PCH officials indicated the ITO amplification activities do not overlap with other government programs and activities because funding is used to amplifying or enhancing export opportunities through B2B interactions during events that host international participants (domestically and abroad).

4.2. Effectiveness

This section presents a summary of findings regarding the evaluation questions related to effectiveness.

4.2.1. Effectiveness: achievement of short-term expected outcomes

Evaluation question: To what extent did the CEF achieve the intended short-term outcomes?

Key findings:

- The CEF is on track to achieving its 2 intended short-term outcomes.

- CEC increased the creative export activities by providing $22.2 million of funding to 48 for-profit and non-profit organizations to undertake export projects.

- ITO increased international promotion of the sector through a variety of activities and engagement activities including 4 TMs, 3 exploratory TMs, 36 amplification events, 9 export seminars and the establishment of 1 formal partnership.

CEC provided direct support to Canadian creative sector for export-ready projects

CEC provided funding of $22.2 million for 48 projects from 2018-19 to 2020-21. The total amount of CEC funding provided for these 48 projects is slightly greater than the budgeted amount of $21 million. 80 % of CEC funded applicants interviewed indicated that CEC funding enabled them to increase their opportunities internationally to a “very great extent”. Footnote 22 The rationale provided for the reported impact of the program is that funding resulted in increased export revenues, identification of new project opportunities and the building of international relationships.

ITO activities increased international promotion of creative sector

From 2018-19 to 2020-21, ITO activities included 4 TMs, 3 exploratory TMs, 36 amplification events and 9 export seminars. One formal partnership with Mexico was created and similar partnerships and collaboration mechanisms were explored in Colombia and Argentina after the Latin America TM. High-level bilateral engagement with Germany and the Netherlands occurred through 2 virtual TMs, with the potential to lead to formalized partnerships. Other ITO activities included strengthened partnerships and collaboration with GAC’s Trade Commissioner Service and the delivery of 8 projects through GAC’s North American Platform Program that supported programming in the creative sector. 4 other projects were cancelled due to COVID-19.

Most of TM participants interviewed for the case studies felt that the TMs supported international promotion and engagement activitiesFootnote 23 “to a very great extent” or “a great extent”. The rationale for the high ratings included support for relationship building and visibility, and government support enhanced reputation or credibility. Of the few TM participants that rated TM achievement as “to a moderate extent” or “to some extent”, the key factors impacting their rating were inability to secure buyers/clients and too few B2B meetings facilitated.

4.2.2. Effectiveness: achievement of medium-term expected outcomes

Evaluation question: To what extent did the CEF achieve the intended medium-term outcomes?

Key findings:

- The CEF has made considerable progress in achieving its 3 intended medium-term outcomes.

- CEC surpassed its target for overall funding ratio with a ratio of $1: $1.6.

- The export revenues generated by CEC funded applicants were $83.2 million, which is higher than targeted. However, most of these export revenues are from only 3 projects and the benefit-cost ratio is less than 1 for two thirds of the CEC funded projects which suggest opportunities to better align the funding decision process with CES objectives and priorities to further increase export revenues.

- The 4 ITO TMs undertaken during this period contributed to 88 potential business deals/commercial agreements. There were 54 commercial agreements signed or in advanced negotiations from a sample of 7 amplification events.

- Canada ranked in 5th position for the GFK Nation Branding Exports Index in 2021 which is the same ranking achieved in 2018. For the GFK Nation Branding Cultural Index, Canada was ranked in 10th position in 2021 which is higher than the 12th position ranking in 2018.

Proportion of project funding committed by CEC funded applicants is greater than anticipated

An analysis of the final reports for 36 CEC completed projects indicates the amount of funding committed by CEC project funded applicants is $27.7 million while the amount of government funding provided to these projects is $17.3 million. Consequently, the actual leverage ratio of government funding to amount spent by funded applicants is 1:1.6 which is greater than the targeted leverage ratio of 1:1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: leverage ratio of funding committed by CEC funding recipients, 2018-19 to 2021-21 – text version

| - | Leverage ratio |

|---|---|

| Target | 1 |

| Actual | 1.6 |

| Source: Administrative data (GCIMS) | |

Export revenues generated by CEC funded applicants are higher than anticipated

The CEC annual target for export revenues is calculated to be $21 million and the target for the first 3 years, therefore, is $63 million. This calculation is based on CEC planned funding of $7 million per year for export-ready projects, multiplied by a targeted ratio of 3:1 for export revenues compared to government funding. As indicated in Figure 2, this three-year target of $63 million has been exceeded as total export revenues were $83.2 million for 29 of the total 48 projects with available revenue data. Of the remaining 19 CEC projects, revenue data was not available for 7 completed projects and there were 12 projects that were still ongoing.

Figure 2: actual versus target export revenues of CEC funded projects, 2018-19 to 2020-21– text version

| - | Export revenue ($M) |

|---|---|

| Target | 63 |

| Actual | 83.2 |

Source: Administrative data (GCIMS)

Revenues and benefit-cost ratio are relatively low for most CEC projects

Most of the export revenues generated by CEC funded projects are due to a small number of projects since 3 projects accounted for 80% of the total export revenues of $83.2 million. Based on reported data available from about half of all CEC funded projects (14 of 29 or 49%, Figure 3), the export revenues generated per project was less than the minimal project cost threshold of $300,000 set by the program. These projects accounted for less than 2% of total export revenues ($1.42 million of the total export revenues of $83.2 million).

Figure 3: analysis of actual export revenues of CEC funded projects, 2018-19 to 2020-21– text version

| Project Export Revenues | % of Total Projects |

|---|---|

| Less than $150,000 | 42% |

| $150,000 to less than $300,000 | 7% |

| "$300,000 to less than $1 million" | 17% |

| $1 million to less than $5 million | 24% |

| $5 million or more | 10% |

Source: Administrative data (GCIMS)

The average benefit-cost ratio (i.e., actual export revenues divided by total project costs) for the 28 projects for which data is available is 1.8 which is lower than the program target of 3. The benefit-cost ratio is less than 1 for two thirds of the projects and is 2 or more for only about one quarter of the projects for which data is available as shown in Table 8.

| Benefit cost ratio | Projected benefit cost ratio % of projects | Actual benefit cost ratio % of projects |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 | 29% | 66% |

| 1 to less than 2 | 13% | 10% |

| 2 to less than 5 | 29% | 17% |

| 5 or more | 29% | 7% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

Source: Administrative data (GCIMS)

It is not clear if all funded projects align with CES objectives and priorities. At the time of project approval, the projected benefit-cost ratio (i.e., projected export revenues divided by total project costs) was less than 1 for 29% of the projects for which data is available. These findings suggest opportunities to improve the funding decision processFootnote 26 as several funded projects did not align with the stated goal of the CEC program, which is to fund a limited number of high-potential projects to achieve the best possible ROI.

Perceived return on investment is high for CEC funded projects

Most of CEC funded applicants interviewed stated that the ROI from the projects funded by CEC was “great” or “moderate” and that projects resulted in increased revenues from export markets. Some respondents also mentioned other results of projects such as jobs created, increased profitability, cultural diplomacy and building a network or business relationships. However, it is important to note that none of the respondents used the conventional definition of ROI, which is ROI = Net income / Cost of investment x 100. Also, some CEC funded applicants could not report their ROI explaining that it would take a few years for benefits to materialize.

Business deals and export revenues resulted from ITO trade missions

Data shows that participation in the 4 TMs undertaken from 2018-19 to 2020-21 contributed to a total of 88 potential business deals/commercial agreements: China (45), Germany (18), Netherlands (14) and Latin America (11). The reported potential financial valueFootnote 27 resulting from the B2B meetings held during 3 of these TMs (all but China), was $50,000 or greater for approximately 45% of the 43 TM participants surveyed; the financial value was less than $50,000 for approximately 35% of respondents (Table 9).

| Financial value | Number of survey respondents | % of survey respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Less than $10,000 | 5 | 12% |

| $10,000 to $24,999 | 6 | 14% |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 4 | 9% |

| $50,000 and more | 4 | 9% |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 7 | 16% |

| $100,000 or more | 8 | 19% |

| Don’t know | 9 | 21% |

| Total | 43 | 100% |

Sources: Compilation of TM’s post-participation surveys results

Based on immediate, one-year post mission surveys and follow-ups with TM participants, the total financial value resulting from China TM was estimated to be $125 million, and $1.5 million for the Latin America TM. The financial value of the Germany virtual TM is estimated to range between $2.3 million and $2.6 million while the financial value of the Netherlands virtual TM is estimated to range between $605,000 and $825,000. The majority (69%) of Germany virtual TM participants that responded to the post-participation survey (n=26) reported that their participation in the TM would “very likely” (31%) or “somewhat likely” (39%) result in a deal or relationship that will benefit their business.Footnote 29 Most (88%) Netherlands virtual TM participants indicated that it is very likely or somewhat likely that their participation in this mission will result in a deal or relationships that will benefit their business.

Post-participation survey data indicates that most TM participants met their objectives. As an illustration, most (79%) of Latin America TM participants reported achieving their objectives while 21% said their objectives were partially achieved. Similarly, most (81%) of Germany TM participants reported that the virtual TM assisted them in meeting their objectivesFootnote 30 to a “great” (35%) or “moderate” (46%) extent while 8% reported “to a small extent”. Eighty one percent (81%) of China TM participants rate their level of satisfactionFootnote 31 with the TM as “excellent” (42%) or “very good” (39%) while the remaining respondents indicated their satisfaction as “good” (19%).

The majority of TM participants interviewed as part of the case studies rated their ROIFootnote 32 as “great” or “good”, whereas a few respondents considered their ROI as “moderate”. The few participants that reported a moderate ROI stated limiting factors that included too few and mismatched B2B meetings. During the interviews, a few TM participants indicated that not enough time has elapsed to determine the ROI of their project.

Consistent with CEC funded applicants, the definition of “return on investment” varied considerably among TM participants and GAC officials. Most key informant respondents interpreted ROI to be an increase in export revenues and did not use the actual definition (i.e., ROI = Net income/cost of investment x 100). Some respondents included relationship building in describing their ROI because in their view the building of relationships in foreign markets is the first step to increasing export revenues. A few TM participants and GAC officials emphasized the importance of the social benefits of the TMs, such as cultural diplomacy.

Amplification events generate deals and appear to be cost effective

Amplification events seem to be effective as they contributed to a total of 54 potential commercial agreements. There were 27 potential commercial agreements signed or in advanced negotiation for a sample of 5 international amplification events and the same number for the 2 domestic events sampled (Tables 10 and 11). Administrative data indicates that the average cost (allocated funding) per amplification event from 2018-19 to 2020-21 was only $17,125.

| Event | Canadian participants | Potential commercial agreementsFootnote 34 |

|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh Fringe and Television Festival, 2018 | 23 | 13 |

| Edinburgh Fringe Festival, 2019 | 23 | 8 |

| Guadalajara International Book Fair, 2018 | 16 | 2 |

| Market, Industry, Film and Audio-visual, 2018 | 8 | n/a |

| Miami Kidscreen, 2020 | 100 | 4 |

| Total | 170 | 27 |

Sources: Compilation of post-participation surveys results and post-amplification event report

| Event | Participants | Potential commercial agreementsFootnote 36 |

|---|---|---|

| Canada Games Online, 2020 | 108 | 5 |

| Content Canada, 2020 | 80Footnote 37 | 22 |

| Total | 188 | 27 |

Sources: Compilation of post-participation surveys results and post-amplification event report

Canada creative sector has achieved international recognition

According to data calculated by an independent organization (Ipsos), Canada ranked in 5th position for the Exports Index in the 2021 Ipsos report, the same ranking achieved in 2018. For the Cultural Index, Canada was ranked in 10th position in 2021, which is higher than the 12th position ranking in 2018. The 2021 Ipsos report elaborated that “Canada has a strong Exports reputation: Though Canada ranks behind the U.S. on all attributes of the Exports Index, it still ranks within the Top 10 on all attributes – noticeably ahead of Australia and France. Canada’s top asset in the Exports Index is its reputation for being a creative place.” The evaluation acknowledges that Cultural Index and Export indices reported by Ipsos cannot be solely attributed to the CEF.

4.2.3. Effectiveness: extent to which performance measures are used to guide decision-making

Evaluation questions: To what extent does the performance measurement for the CEF gather the data required to inform decision-making and reporting? Are there opportunities for improvement?

Key findings:

- The performance measurement information is useful for decision-making to some extent.

- There are gaps and opportunities to improve performance measurement data related to the following issues: lack of finalized logic model; inconsistent data collection, compilation and reporting; lack of longer-term survey data from CEC projects; involvement of equity communities; response rate of post-participation surveys; confusion of recipients on some expected outcomes and performance indicators.

Performance measurement data is useful for decision-making, but some gaps exist

The CEF expected results, indicators, targets, and data sources are clearly presented in the CES original documentation. Most PCH officials interviewed indicated that the existing performance data is useful and accurate for decision-making and accountability since there is a performance strategy in place and results data are being collected. However, key informants and program document review identified challenges with the existing CEF performance measurement data. While draft logic models have been developed, they have not been approved by senior management and included in the PIP.

The short timeline for data collection does not capture all expected outcomes

A longer-term perspective is required to achieve some results, particularly related to export revenues. The document review indicated that for CEC recipients, PCH reporting requirements are for up to 3 months following project completion. The program follows up with recipients one year after project completion for an update on results, but it is not mandatory for recipients to provide this info. For TMs participants, a post-participation survey is sent 6 months and 1 year after the end of TMs.

Some key informants interviewed highlighted that it takes time to obtain an accurate assessment of the CEF impacts such as the benefits of CEC funded projects and ITO supported activities. A few PCH officials and CEC funded applicants indicated that a follow-up survey at least 1 or 2 years after completion of CEC projects would provide a more accurate assessment of export revenues generated on a sustained basis. Some TM participants also indicated that a longer-term perspective is needed to accurately assess the increase in export revenues as partnerships and contractual agreements take time to develop.

Given the time required to achieve export revenue results, some PCH officials indicated a need for some additional interim performance measures to be established, such as the number of relationships developed in export markets. While such a performance measure would provide an indication of the extent of activity, it is not sufficient as a stand-alone outcome measure because it does not indicate the benefits derived from the relationships established.

The performance data is not consistently collected, compiled, and reported

The documents reviewed demonstrated that the CEF does not report on all its expected outcomes. For example, the 2019-20 CES Results Deck does not provide consistent and compiled information on export revenues generated and ROI. While CEC funded applicants are requested to report on the actual export revenues achieved by their projects in their final reports, some funded applicants did not do so after project completion. It was difficult to obtain results from the TMs and amplification events. Post-participation and 1 year follow-up surveys of TM participants and amplification event participants are also intended to be conducted to obtain information on export revenues generated and the number of potential business deals/commercial agreements signed. However, the document review pointed out, that follow-up surveys were not always conducted or available during the evaluation period.

The low participant response rates to post-participation surveys

In addition to the one-year follow-up survey of TM participants, post-participation surveys of participants are usually undertaken upon completion of TMs and amplification events. Some PCH and GAC officials expressed difficulties in obtaining high response rates to the post-participation surveys for TMs and amplification events. The evaluation noted that TM participants are under no obligation to report on their commercial deals, endeavors or export revenues generated by ITO activities. The document review noted that the average post-participation survey response rate for the 4 TMs was 52% and ranged from 27% to 63%. The lack of standardized survey questions and breakdowns makes it difficult to aggregate the survey results.

A lack of data regarding program involvement with equity communities

The evaluation noted that the program does not collect sufficient information related to its reach or impact on equity communities. One half of the CEF PCH officials interviewed stated that the CES performance measurement strategy does not collect accurate and reliable data on equity communities. However, the evaluation noted that efforts were being made by the program to determine how and what data should be collected regarding the CEF participation by equity communities. The literature review indicated that some similar programs enable the identification of applicants’ part of equity communities to determine if they are eligible for special consideration.

Limitations in the measures and definitions

Three areas were identified by the evaluation as not being clear to all stakeholders: ROI, financial value, and social versus economic expected impacts of the programming.

The definition of ROI is not clear in program documentation including its performance strategy. The term ROI is most used by business in a financial sense, and is expressed as a percentage, calculated as follows: ROI = Net income / cost of investment x 100. The evaluation made a number of observations:

- As shown in the Evaluation Framework in Annex B, the term “return on investment” or “ROI” is not defined for the following medium-term intended outcome “The CES generates ROI in the Canadian creative sector”. Here, it does not appear that the term ROI is intended as a financial term, but that it is meant to refer to “an increase in export revenues”, as an indicator of a medium-term outcome.

- When the CEF PCH officials, GAC officials, CEC funded applicants and ITO TM participants were asked to indicate the ROI of the CEF activities, most respondents referred to the impact of the CEF in increasing export revenues while others also referred to other benefits such as relationship and networking building, job creation, increase in profitability, cultural diplomacy, and other social outcomes.

- A few CEC applicants interviewed noted difficulties in measuring the economic ROI of their projects.

Another term that has resulted in varied interpretations is the post-participation surveys that ask TM participants to indicate the “financial value” that might result from their B2B meetings during the TM. The term “financial value” is not commonly used by businesses and this term appears to have been interpreted as an “increase in export revenues” by post-participation survey respondents.

There may be some confusion related to economic versus social expected results of the program. Some PCH officials, GAC TC and TM participants interviewed stated there is some ambiguity regarding whether program objectives and performance measures should include social outcomes, such as cultural diplomacy. A 2019 Senate report cited former ambassador Cynthia P. Schneider, defining cultural diplomacy as “the exchange of ideas, information, art and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples to foster mutual understanding.” This definition does not refer to any economic outcomes. The CEF does not have social objectives recognizing the existence of other programming. Some program officials underlined that the inclusion of outcomes and performance measures related to social outcomes such as cultural diplomacy would reduce the effectiveness of the CEF in accomplishing its stated focus to maximize export revenues of the Canadian creative sector.

4.3. Efficiency: demonstration of efficiency

Evaluation question: To what extent was the CEF delivered efficiently?

Key findings:

- Overall, the CEF was delivered efficiently with opportunities for improvement.

- Good management practices have been employed in the delivery of the CEC and ITO activities.

- There are gaps and risks related to efficiency in 2 key areas: the extended time required to make CEC funding decisions, as PCH service standard of 26 weeks was achieved only 34% of the time; and the lack of clarity on funding priorities and eligibility criteria.

CEF actual expenditures slightly exceeded the planned expenditures

From 2018-19 to 2020-21, total CEF expenditures were $40.6 million, or 2% higher than planned spending of $39.8 million (Tables 12 and 13). The higher spending was mostly due to Gs&Cs that exceeded the budget by $1.5 million. Slightly higher than planned expenditures were also incurred for salaries & EBP. Lower O&M expenditures could partially be explained as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and a lower-cost virtual TMFootnote 38 rather than an in-person event in 2020-21. Also, there were difficulties estimating TM costs in general, with costs varying depending on the destination country and on the number of TM participants.

| Fiscal Year | Salaries & EBP | O&M | Gs&Cs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 13.4 |

| 2019-20 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 13.2 |

| 2020-21 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 13.2 |

| Total | 8.3 | 10.5 | 21.0 | 39.8 |

Source: PCH Financial Management Branch

| Fiscal Year | Salaries & EBP | O&M | Gs&Cs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 7.8 | 12.6 |

| 2019-20 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 7.2 | 14.2 |

| 2020-21 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 13.8 |

| Total | 9.6 | 8.5 | 22.5 | 40.6 |

Source: PCH Financial Management Branch

Time required to review CEC applications exceeded the service standard in most instances

While the service standard for acknowledging receipt of applications within 2 weeks and the one for issuing payments within 4 weeks were met respectively at 95% and 89%, the standard of 26 weeks to provide a funding decision was met only 34% of the time.Footnote 41 In particular, longer approval times occurred for Gs&Cs funding amounts greater than $100,000. The factors contributing to the longer than anticipated time for funding decision include the time required for consulting with internal and external creative sector experts to determine the feasibility of a project and the large number of applications assessed by intake.

In addition, PSPC conducts a review of the financial capacity to undertake the proposed project of each recommended applicant. The financial assessment has several components:

- Financial criteria including ratio analysis to assess liquidity, debt management and profitability and a review of recent operating results.

- Assessment based on non-financial criteria (i.e., credit report).

- Financial capability summary and opinion.

- Funding necessity assessment.

- Project viability assessment.

The financial assessment does not include an assessment of the export marketing plan or the extent to which the export revenue projections in the application are based on market research and are likely to be achieved.

The above activities demonstrate good management practices but increase the time required to make funding decisions. About one half of CEC applicants interviewed stated that it took too long to receive a funding decision. The negative impacts of late funding decisions mentioned by a few applicants are:

- Fewer accomplishments than anticipated due to reduced time to deliver the project.

- Inability to capitalize on some opportunities.

- Difficulties securing additional funding.

- Needs that changed which made their project less useful than anticipated.

Other aspects of the CEC operational processes

The majority of CEC applicants interviewed felt that program staff were accessible and helpful. Most funded applicants did not express concerns with the program’s reporting requirements while a few applicants indicated that it was difficult and costly to obtain audited financial reports within the time frame requested by the program.

Some applicants noted ambiguity in the eligibility criteria and stated the criteria are too broad. Applicants from non-profit organizations indicated that the application form is not adapted to arts organizations and includes unfamiliar business language terms, such as business plan, export plan and strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. This suggests that there may be a misunderstanding of the economic nature of the program.

The document review showed that the application and assessment tools are not well aligned with the expected outcomes of the program. Indeed, these documents do not refer to high ROI, but rather the reference to export revenue without indicating that projects must generate high revenues to be potentially funded. This may explain why some unfunded applicants interviewed considered themselves eligible even though their project does not meet the program’s outcomes.

Delivery of ITO’s activities has worked well

Good management practices have been demonstrated in the delivery of ITO activities including the TMs, amplification events and seminars. For example, ITO established partnerships with third parties such as GAC and foreign consultants, to assist with the planning and conduct of TMs and the identification of amplification events. ITO also demonstrated flexibility and capability to adapt activities to changing needs and contexts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including shifting to virtual delivery for TMs and amplification events.

TM participants are satisfied with ITO trade missions, particularly the B2B meetings

Most of China and Latin America TM participants that responded to the post-participation surveys rated their level of satisfaction in the TM as “excellent” and “very good”.Footnote 42 The majority of TM participants and GAC officials interviewed as part of the case studies reported that the B2Bs were well coordinated and sufficiently timed. The majority of TM participants and GAC officials stated that in-person B2B meetings were more impactful than virtual meetings; however, most agreed that virtual and in-person meetings can complement one another, particularly if offered sequentially, such as developing kickstart relationships virtually and then following-up in person.

The case studies found that the in-person Latin America TM activities rated as most valuable are as follows (with most valuable mentioned first): B2B meetings, networking with local Latin American stakeholders, and market briefings, while the least valued activity was the site visits. For the virtual Germany TM, the activities rated as most valuable were the B2B meetings and the matchmaking consultant while the least valued was the panel discussions.

There are opportunities to enhance the ITO trade missions

While the majority of TM participants and GAC officials interviewed expressed satisfaction with the TMs, suggestions for improvement were noted:

- Some TM participants indicated that the benefit of the cross-sectoral approach employed for TMs resulted in opportunities for collaboration and synergies between companies in different creative sub-sectors, through meeting Canadian artists and organizations in other sub-sectors (e.g., adaptations of books and music to TV series and movies). The main challenge noted with multi-sector TMs is that it is difficult to cater to all TM participants’ needs and organize meetings with buyers/clients for all sub-sectors represented in the delegation.

- Some TM participants and GAC officials interviewed noted that the B2B meetings were not always relevant to the TM participants and that there are opportunities to improve the matchmaking.

- A few GAC officials indicated a need for more coordinated planning between delivery partners (PCH, GAC and matchmaking consultants) and greater effort to ensure that the most appropriate companies are selected to participate in the TMs, accordingly to the country where the TM is taking place.

Most participants surveyed are satisfied with the ITO amplification events

Post-participation surveys of sample amplification events indicates that most participants were satisfied, particularly with the B2B meetings and networking opportunities (Tables 14 and 15).

| Event | Canadian participants | Number of survey Respondents | Canadian participant satisfaction with amplification eventFootnote 43 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh Fringe and Television Festival, 2018 | 23 | 5 | 80% (4 out of 5) were satisfied with B2B and networking opportunities. |

| Edinburgh Fringe Festival, 2019 | 23 | 15 | 66% (10 out of 15) found the Pitch my Piece event to be better than expected. |

| Guadalajara International Book Fair, 2018 | 16 | 6 | 100% (n=6) were satisfied with B2B and networking opportunities; 80% expected that these would generate business outcomes. |

| Market, Industry, Film and Audio-visual, 2018 | 8 | 8 | 50% (4 out of 8) found the B2B meetings and networking opportunities to be good, very good or excellent. |

| Miami Kidscreen, 2020 | 100 | 73 | 84% (61 out of 73) found the networking reception valuable; 90% of Canadian participants found the “meet and greet” helpful. |

Source: Compilation of post-participation surveys results and post-amplification event report

| Event | Participants | Number of survey respondents | Participant satisfaction with amplification eventFootnote 44 |

|---|---|---|---|