Best practices in administrative decision-making: viewing the Copyright Board of Canada in a comparative light

A report prepared for Canadian Heritage and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

Paul Daly, University of Montreal

This is an independent expert report produced by Paul Daly as commissioned by the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Department of Innovation, Science, Economic Development. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Paul Daly, 2016

CH44-161/2016E-PDF

978-0-660-06010-1

Best practices in administrative decision-making: viewing the Copyright Board of Canada in a comparative light

- Introduction and executive summary

- Overview

- Summary of recommendations

- I. General background

- II. Functions and functioning of the Copyright Board

- III. General principles of administrative law

- IV. Comparable federal administrative tribunals

- V. Civil justice reform

- VI. Culture change

- VII. Summary and recommendations

- VIII. Biographical information

Introduction and executive summary

This report focuses on the decision-making process used by the Copyright Board of Canada for tariff setting. Previous reports have identified delays in tariff setting as a problem to be resolved. Drawing on the decision-making processes of comparable federal administrative tribunals and recent civil justice reforms in Canada, this report makes several recommendations as to how the Copyright Board could improve its tariff-setting process so as to bring the process into line with best practices in administrative decision-making. The general principles of administrative law, which provide the overarching legal framework in which any changes will be implemented, are also laid out.

This report takes as given the current role of the Copyright Board and the resource constraints under which it operates, proceeding on the basis that additional funding will not be made available to the Copyright Board in the near future. Accordingly, the goal of this report is to provide the Copyright Board with additional tools that it can use to improve the efficiency of its decision-making processes. In this regard, this report notes that tariff-setting delays might be due at least in part to the attitudes and expectations of those who participate in the process, in which case the additional tools could usefully be used to effect a culture change in Copyright Board proceedings.

Overview

|

Section I |

General Background |

|---|---|

|

Section II |

Functions and Functioning of the Copyright Board |

|

Section III |

General Principles of Administrative Law |

|

Section IV |

Comparable Federal Administrative Tribunals |

|

Section V |

Civil Justice Reform |

|

Section VI |

Culture Change |

|

Section VII |

Summary and Recommendations |

In Section I, general background is provided about this report, which explains why the report was commissioned and lays out the context in which the report was prepared.

In Section II, the role of the Copyright Board is explained, in order to better understand its current decision-making framework and the challenging environment within which it operates.

In Section III, the general principles of administrative are laid out, with a view to explaining the framework in which the recommendations of this report can be implemented by the Copyright Board.

In Section IV, the decision-making processes of comparable federal administrative tribunals (the selection of which is, in addition, justified) are laid out alongside the tariff-setting process of the Copyright Board.

In Section V, the literature on Canadian civil justice reform, which aims at making court processes more efficient, is examined, with a view to formulating best practice recommendations for administrative tribunals.

In Section VI, a general framework to guide the reform of administrative procedures is proposed, with particular reference to the need to give administrative decision-makers such as the Copyright Board the tools to effect culture change where attitudes and expectations of actors may cause inefficiency in the decision-making process.

Sections IV, V and VI also form a coherent whole, starting with administrative processes in Section IV (with a view to ascertaining how the Copyright Board is placed relative to peer federal administrative tribunals) and moving to civil justice reform in Section V (with a view to drawing inspiration in the administrative context from judicial reforms), before finishing in Section VI with a discussion of the importance of culture (with a view to bringing the lessons learned in Sections IV and V into a theoretical best-administrative-practice framework).

In Section VII, recommendations are made as to the procedural reforms that have the potential to reduce the time the Copyright Board takes to render tariff-setting decisions.

Summary of recommendations

|

Recommendation 1 |

Legislation to give Copyright Board power to award costs |

|---|---|

|

Recommendation 2 |

Regulations to provide for various steps in Copyright Board’s tariff-setting process |

|

Recommendation 3 |

Retention and further development of current Model Directive on Procedure |

|

Recommendation 4 |

Effecting culture change |

|

Recommendation 5 |

Further study of federal administrative decision-makers |

Recommendation 1: Parliament should legislate to provide the Copyright Board with the ability to award costs.

Recommendation 2: the Copyright Board should propose to adopt, with the approval of the Governor in Council, formal rules that provide for various mandatory steps in the tariff-setting process.

Recommendation 3: the Copyright Board should retain its current Model Directive on Procedure, with a view to providing more detail about the mandatory steps in the tariff-setting process.

Recommendation 4: the Copyright Board should continue to attempt to effect culture change through all available means – including ‘Best Practices’ manuals.

Recommendation 5: the legislative and executive branches of the federal government should undertake a comparative analysis of the decision-making efficacy of selected federal administrative decision-makers, taking account of the resource constraints under which these decision-makers operate, and the complexity of their tasks, with a view to developing a metric which would propose benchmarks for the time periods within which regulatory decisions ought to be rendered.

I. General background

Section 92 of the Copyright Act provides that every five years “a committee of the Senate, of the House of Commons or of both Houses of Parliament is to be designated or established for the purpose of reviewing this Act”. Footnote 1 In this context, I was asked by Canadian Heritage and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada to prepare the present study on the Copyright Board of Canada.

Parliament has held public hearings which culminated in a Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, Review of the Canadian Music Industry. Footnote 2 The Committee held fourteen meetings, hearing from eighty-two witnesses and receiving fifteen written briefs. Though the Committee’s Report ranged widely over a variety of issues touching Canada’s music sector, it furnished a recommendation relating to the Copyright Board:

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada examine the time that it takes for decisions to be rendered by the Copyright Board of Canada ahead of the upcoming review of the Copyright Act so that any changes could be considered by the Copyright Board of Canada as soon as possible. Footnote 3

This recommendation was apparently based on “the most common suggestion made by witnesses” in relation to the “launching of new services”: “to provide the Copyright Board of Canada with the resources it needs to speed up its decision-making process”. Footnote 4 It should be noted, however, that a Complementary Report by the Liberal Party of Canada prepared by Mr. Stéphane Dion, took issue with this recommendation because “it ignores the main issue raised by many intervenors: an apparent lack of resources”:

The Copyright Board of Canada seems overwhelmed by the number and complexity of the cases it must address. The Board must face a huge workload and constantly analyze complex and massive expert reports dealing with legal, economic and technical issues. Although this is not only a resource issue and the Board’s modus operandi must also be scrutinized, it is clear that a serious study of the means presently available to the Board must also be included in the Standing Committee’s recommendation. Footnote 5

Subsequently, Professor Jeremy de Beer of the University of Ottawa prepared a report, Canada’s Copyright Tariff Setting Process: An Empirical Review, Footnote 6 which responds in part to the recommendation of the Committee. As Professor de Beer explained, “the aims of the study were to review the existing literature, map the tariff-setting process, develop methods for empirical analysis, and begin to collect and analyze data”. Footnote 7 The executive summary neatly lays out the key findings of Professor de Beer’s analysis of the tariff-setting process:

The certified tariffs took an average of 3.5 years to certify after filing. The average pending tariff has been outstanding for 5.3 years since filing as of March 31, 2015. On average, tariffs are certified 2.2 years after the beginning of the year in which they become applicable, which is in effect a period of retroactivity. The standard deviation in the time from proposal filing to tariff certification is 2 years. A hearing was held in 28% of tariff proceedings. The average time from proposal filing to a hearing in those proceedings was just over 3 years. The average time from a hearing to tariff certification was almost 1.3 years. Footnote 8

Between the publication of Professor de Beer’s report and the publication of the present study, the Supreme Court of Canada has commented unfavourably on the fact that some of the Copyright Board’s decisions “have, in recent years, taken on an increasingly retroactive character”. Footnote 9

Noting that his study laid the “groundwork for future analysis”, Professor de Beer suggested a fruitful next step would be “to analyse the copyright tariff-setting process with other administrative processes”. Footnote 10

At the same time, work has been conducted on (to use Mr. Dion’s terms) “the means presently available to the Board”. The Copyright Board formed a Working Committee on the Operations, Procedures and Processes of the Copyright Board, which produced a Discussion Paper on Two Procedural Issues: Identification and Disclosure of Issues to be Addressed During a Tariff Proceeding and Interrogatory Process. Footnote 11 The terms of reference provided by the Copyright Board asked the Working Committee “to review the various steps of proceedings before the Board so as to determine how they can be made more efficient and productive, and to propose how these new, more efficient approaches should be implemented and communicated”. Footnote 12

The Working Committee furnished forty-three recommendations. Some, such as the means of publicizing proposed tariffs, relate more to the treatment of matters falling within the Copyright Board’s jurisdiction than to the streamlining of its procedures. Many recommendations do, however, respond to concerns about the length of the Copyright Board’s decision-making processes.

In particular, the Working Committee made several procedural recommendations in relation to the identification and disclosure of issues to be addressed during a tariff proceeding. For instance, tariffs proposed for the first time by a collective society should be accompanied by a non-binding statement containing “information about the content of a tariff of first impression and of the nature, purpose and ambit of any proposed material change to an existing tariff”. Footnote 13 Similarly, those objecting to a tariff “should be required to state in their objection the reasons therefor, either in their notice of objection or as soon as possible thereafter”. Footnote 14 In addition, the Working Committee made many recommendations in respect of interrogatories, including the convening by the Board of “a preparatory meeting between the parties and the Board after the collective has replied to objections and before interrogatories are exchanged”. Footnote 15 These recommendations respond, no doubt, to a “concern” about “the sheer number of interrogatories posed” in contemporary Copyright Board proceedings. Footnote 16

The present study takes the resource constraints and legislative objectives of the Copyright Board as givens, focusing like the Working Committee on procedural reforms the Copyright Board might implement to respond to concerns about delays in its tariff-setting process. Accordingly, the goal of the present study is to compare features of the Copyright Board with other Canadian regulatory bodies (judicial and administrative) to gain contextualized insight on the Copyright Board’s processes and identify best practices that could potentially be implemented to improve the functioning of the Board. Given that the Working Committee’s work is ongoing, the present study takes an approach that is more general in nature, focusing on the general principles of administrative law and efficient administrative decision-making, with a view to providing an overall framework that will assist the Working Committee, the Board and other relevant actors in identifying and implementing helpful reforms.

II. Functions and functioning of the Copyright Board

Role

The Copyright Board is established by section 66(1) of the Copyright Act. It is “an independent administrative tribunal [that] consists of not more than five members, appointed by the government for a set term of up to five years [supported by] a small permanent staff that includes a Secretary General, a General Counsel and a Director of Research and Analysis”. Footnote 17 In its own words:

The Board is an economic regulatory body empowered to establish, either mandatorily or at the request of an interested party, the royalties to be paid for the use of copyrighted works, when the administration of such copyright is entrusted to a collective-administration society. Footnote 18

The Board oversees several copyright regimes, the formation of which stems “in part from historical evolution” yet also reflects “policy choices”. Footnote 19 The administrative structure is marked out in particular by the key players in Canadian copyright: collective societies, Footnote 20 which propose tariffs for the use of copyrighted material, and users, who must pay the tariffs. Collective societies and users are generally the highest-profile actors in Copyright Board tariff setting. Indeed, the Copyright Board’s function is to “regulate the balance of market power between copyright owners and users”. Footnote 21

In general:

[T]he Board has no explicit policy-making and legislative powers, but performs its functions on a case-by-case basis. Nonetheless, its function is highly specialized and its subject-matter is of a technical nature. The Board’s statutory mandate requires it to set the rates of remuneration payable to the collective societies that represent various copyright holders, and to determine what terms and conditions, if any, should be attached to the royalties. In exercising this broad rate-setting discretion, the Board must balance the competing interests of copyright holders, service providers and the public. Footnote 22

Procedures

It is difficult to generalize about the procedures employed to discharge this function. The Copyright Board “prefers to formulate specific rules of procedure appropriate to a particular hearing, which are usually formulated after consultation with the parties”. Footnote 23 For instance, it has “made full use of its ability to control its own proceedings to allow interventions from persons or groups who are not directly interested but who are likely to provide a useful point of view”. Footnote 24 The Board has a Model Directive on Procedure, Footnote 25 itself drawn in very broad terms Footnote 26 and providing, moreover, that “[t]he Board may dispense with or vary any of the provisions of this directive”.

The Copyright Board has a significant degree of discretion in approving tariffs. For instance, the Copyright Act provides in respect of one regime that “the Board… may take into account any factor that it considers appropriate”; Footnote 27 having considered these and the specific statutory considerations it is obliged to take into account, Footnote 28 the Board “shall certify the tariffs as approved, with such alterations to the royalties and to the terms and conditions related thereto as the Board considers necessary…” Footnote 29 Indeed, “[t]he Board is allowed to develop a tariff structure that is completely different from the one proposed by the collective or the users…” Footnote 30

To some extent, proceedings are controlled by the provisions of the Copyright Act.Collective societies file proposed tariffs on or before March 31, in order that the tariff can come into effect the following year. Footnote 31 Once a tariff has been approved, it comes into effect at the beginning of the year following the year in which the tariff was proposed – the current delays in the tariff-setting process mean that tariffs that are not approved between March 31 and December 31 of the year in which they are proposed will have retroactive effect. Footnote 32

It has been said that “[a] typical hearing schedule will include the following steps”:

- the interrogatory process;

- the filing of the statement of cases (i.e. summary of evidence and arguments) by the collective societies);

- the filing of the statement of cases by the objectors to the proposed tariff;

- the hearing. Footnote 33

Schedules are not necessarily skeletal and may go into significant detail about the process to be followed. Footnote 34 Having adopted a schedule that has been approved by the Board, Footnote 35 parties exchange interrogatories at an agreed date. These are not sent to the Board but rather are exchanged between the parties. Written objections may then be exchanged, again between the parties, who may in addition wish to reply to particular objections. Once the objections and replies have been exchanged, the parties attempt to negotiate a way forward. Only at this point does the Board become involved to resolve, on a formal basis, any outstanding disagreements. Once this step has been completed, responses to interrogatories are exchanged. Again, the Board becomes involved only if a party requests a formal ruling on a response it considers unsatisfactory. With information received from interrogatories to hand, the parties file their respective statements of case, at which point the Board can proceed to a full hearing.

The Board has, through a long series of decisions, “adopted a more nuanced approach to the amount of information which must be provided to the other side during the interrogatory process”: Footnote 36

Participants are reminded of recent statements of the Board relating to what constitutes an acceptable burden of discovery. Counsel representing the participants in these proceedings have often appeared before the Board. They are asked to help their clients show restraint in the amount of information that they will seek from other participants in these proceedings. Footnote 37

Several considerations factor into the Board’s formal rulings during the interrogatory process, for instance: “[t]he amount of information requested”; “[t]he generation of new documents” (which should be kept to a minimum); and whether information “is protected by litigation privilege”. Footnote 38 In addition, the Copyright Board is sometimes at one remove from those who hold relevant materials, “[b]ecause the interrogatories asked by the various collectives are invariably addressed to the association’s underlying members, the association has the thankless task of encouraging compliance by its members with the Board’s interrogatory process”. Footnote 39

Powers

It is important to note that the Copyright Board has “with respect to the attendance, swearing and examination of witnesses, the production and inspection of documents, the enforcement of its decisions and other matters necessary or proper for the due exercise of its jurisdiction, all such powers, rights and privileges as are vested in a superior court of record”. Footnote 40 Yet it has generally refrained from using the full extent of these powers, preferring to rely on reminding participants that it could invoke its powers to ensure compliance. In one difficult case involving a tariff for works used by commercial radio stations, the Board explained its position as follows:

…many of the targeted stations engaged in what was from all appearances systematic obstruction coupled with inappropriate consultations amongst themselves in preparing answers. Despite the many orders that were issued, some of the respondents still refused to the end to answer the questions addressed to them. The Board has means of compelling reluctant respondents to comply with its requests. It chose not to use those means in this case. It would be unwise to assume that the Board will display as much patience in the future. Footnote 41

However, “contrary to most Commonwealth copyright tribunals, the Board does not have the power to award costs”, Footnote 42 although it has been remarked that “…it is also clear that the inability of the Board to award costs has sometimes resulted in it having to deal with matters that could have been addressed more expeditiously”. Footnote 43

Contemporary challenges

Questions about the management of the tariff-setting process must be addressed against the backdrop of the important contemporary challenges faced by the Copyright Board. Though the Board’s work of approving tariffs is primarily of “technical complexity”, Footnote 44 its decisions also have “polycentric policy aspects” Footnote 45 that “can have enormous consequences for widespread industry practices and major copyright law and policy problems”. Footnote 46 The Copyright Board itself has noted that it may consider “public policy” in discharging its mandate, not simply technical matters; Footnote 47 its role “greatly exceeds finding the right ‘number’ for a given tariff…” Footnote 48

Modern copyright law features a high degree of fragmentation. Users may need permissions from several different rights-holders in respect of several different rights in respect of the same copyrighted material. In particular, the rise of the Internet has increased the complexity of copyright law: “Right fragments such as ‘reproduction’ or ‘public performance’ are complex and increasingly a source of frustration for users because they no longer map out discrete uses, especially on the Internet”. Footnote 49 Indeed, “even when reasonably efficient systems are available, rights clearance may prove a difficult task”. Footnote 50 This is an important factor to bear in mind when assessing the efficiency of the Copyright Board’s procedures. Added to this is the significant role the Copyright Board must play in tracing the legal contours of copyright protection: Footnote 51 in order to perform its tariff-setting function, the Copyright Board must determine whether a particular action triggers its jurisdiction in the first place, a time-consuming task that typically ends before the courts many years later. Footnote 52

III. General principles of administrative law

Judicial oversight

Decisions of the Copyright Board that affect individuals’ “rights, privileges or interests” Footnote 53 are subject to judicial review. Ordinarily, judicial review remedies are available from the provincial superior courts, but the Copyright Board is a “federal board, commission or other tribunal” subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Appeal. Footnote 54 In this section, I explain the practical implications of this superintending jurisdiction for any proposed reforms to the Copyright Board’s procedures.

Judicial review is concerned with the legality, reasonableness and procedural fairness of administrative decision-making. Footnote 55 The principles of legality and reasonableness apply to the substantive matters addressed by the Copyright Board, such as the scope of copyright protection Footnote 56 and the calculation of tariffs, Footnote 57 whereas the principle of procedural fairness applies to its decision-making processes. Footnote 58 On substantive matters, Canadian judges generally defer to expert agencies. In the case of the Copyright Board Canadian courts have in recent years exercised close control over strictly legal questions addressed by the Copyright Board Footnote 59 whilst according it a greater margin of appreciation on matters of mixed fact and law, policy and discretion. Footnote 60 On procedural matters, on which I will focus, the state of the law is similarly nuanced. Footnote 61

Fairness and deference

There exists in Canadian administrative law a “a general right to procedural fairness, autonomous of the operation of any statute…” Footnote 62 What will be required by way of procedure in any given case depends on the interplay of several contextual factors set out by the Supreme Court of Canada. Footnote 63 In general, however, as long as an interested party has not been deprived altogether of a procedural right – such as notice or making submissions – courts will be slow to intervene to correct a decision-maker’s choice as to the appropriate process to follow.

Administrative decision-makers such as the Copyright Board do not need to employ trial-type procedures in the exercise of their functions. Footnote 64 As has been said, the principles of fairness in administrative law are not “engraved on tablets of stone”: Footnote 65 “Although the duty of fairness applies to all administrative bodies, the extent of that duty will depend upon the nature and the function of the particular tribunal”. Footnote 66 Fairness is “eminently variable and its content is to be decided in the specific context of each case” Footnote 67 and, in the context of economic regulatory bodies such as the Copyright Board, does not require them to copy the processes used by the courts: “Court procedures are not necessarily the gold standard…” for administrative decision-makers. Footnote 68

Canadian courts long have adopted a deferential posture in respect of administrators’ procedural policy choices. While the courts retain the final word on whether administrative procedures comply with the duty of fairness, they must “take into account and respect the choices of procedure made by the agency itself”: Footnote 69 “The determination of the scope and content of a duty to act fairly is circumstance-specific, and may well depend on factors within the expertise and knowledge of the tribunal, including the nature of the statutory scheme and the expectations and practices of the [relevant] constituencies”. Footnote 70 Indeed, “a degree of deference to an administrator’s procedural choice may be particularly important when the procedural model of the agency under review differs significantly from the judicial model with which courts are most familiar”. Footnote 71 For instance, in respect of procedural choices made during proceedings – for instance, whether to merge several tariff proposals – deference will be due. Footnote 72 A recent decision of the Federal Court of Appeal with respect to the National Energy Board is instructive, as that body was accorded “a significant margin of appreciation” in respect of its own process, because it “is master of its own procedure” with “considerable experience and expertise in conducting its own hearings and determining who should not participate, who should participate, and how and to what extent…[and] in ensuring that its hearings deal with the issues mandated by [law] in a timely and efficient way”. Footnote 73

So-called “soft law” permits administrative decision-makers to regulate by means of “nonlegislative instruments such as policy guidelines, technical manuals, rules, codes, operational memoranda, training materials, interpretive bulletins, or, more informally, through oral directive or simply as a matter of ingrained administrative culture”. Footnote 74 Administrative decision-makers may adopt soft law instruments even in the absence of a statutory provision expressly permitting them to do so. Footnote 75 Such instruments “can assist members of the public to predict how an agency is likely to exercise its statutory discretion and to arrange their affairs accordingly, and enable an agency to deal with a problem comprehensively and proactively, rather than incrementally and reactively on a case-by-case basis”. Footnote 76 Care must be taken in drafting such instruments, however, as they may not be used to fetter a discretionary power Footnote 77 and may, in some circumstances, create enforceable legitimate expectations that have the practical effect of binding the decision-maker. Footnote 78

Overall, “the Board has the general authority, consistent with its statutory role, to provide for its own procedures”. Footnote 79 Accordingly, modifications to the Copyright Board’s procedures are likely to be treated deferentially on judicial review. Recent jurisprudence, especially from the Federal Court of Appeal, Footnote 80 indicates that the Copyright Board will have a significant margin of appreciation in which it can reformulate its procedures to better achieve its policy goals.

There are some pitfalls for the unwary, however, that must be avoided. For instance, courts are unlikely to look kindly on sub-delegation of authority Footnote 81 or the accumulation of functions in a single officer (which is liable to raise a perception of bias, in its administrative law sense). Footnote 82 As a matter of common law such arrangements are likely to be viewed as unlawful. However, where they are authorized by positive law, the courts will not interfere. Footnote 83 Finally, a power to award costs would have to be provided for expressly in the Copyright Act, Footnote 84 consistent with the general proposition that “no pecuniary burden can be imposed upon the subjects of this country, by whatever name it may be called, whether tax, due, rate or toll, except upon clear and distinct legal authority”. Footnote 85

Reforming judicial review?

More generally, while it might be theoretically possible to oust judicial review of the Copyright Board altogether, Footnote 86 thereby eliminating any delays caused by judicial proceedings, it is highly unlikely that any such effort would be successful. The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized that judicial review of administrative action is constitutionally guaranteed as a matter of interpretation of s. 96 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Footnote 87 Accordingly, the courts would either circumvent (by permitting the superior courts to assume jurisdiction Footnote 88 ) or disregard (by holding to be unconstitutional Footnote 89 ) any such attempt to insulate the Copyright Board from judicial oversight.

Even a legislative attempt to ensure a higher level of deference to decisions of the Copyright Board on matters of law is unlikely to have an appreciable impact on the length of time it takes to complete the tariff-setting process. This sort of attempt would specify a deferential standard of review by inserting a clause in the Copyright Act to the effect that “the standard of review of decisions of the Copyright Board is reasonableness”. Footnote 90 While a change in the standard of review might act as a disincentive against launching proceedings in the Federal Court of Appeal, it bears noting that reasonableness review “is not unduly deferential” and “does not take anything away from reviewing courts’ responsibility to enforce the minimum standards required by the rule of law”. Footnote 91 In particular, the “range” of reasonable outcomes Footnote 92 “can be narrow, moderate or wide according to the circumstances”, Footnote 93 depending on a variety of contextual factors. Footnote 94 The practical effect of specifying in legislation that reasonableness is the standard of review of decisions of the Copyright Board would most likely be that appellants would focus their efforts on arguing that the Copyright Board’s decisions fell outside a narrow range of reasonable outcomes. Turning the clock back to an era in which the Copyright Board’s predecessor “enjoyed a considerable degree of deference” would be very difficult in current conditions. Footnote 95

IV. Comparable federal administrative tribunals

The spectrum of the administrative state

One can perceive the various organisms of the modern administrative state as lying along a spectrum: Footnote 96

The categories of administrative bodies involved range from administrative tribunals whose adjudicative functions are very similar to those of the courts, such as grievance arbitrators in labour law, to bodies that perform multiple tasks and whose adjudicative functions are merely one aspect of broad duties and powers that sometimes include regulation‑making power. The notion of administrative decision‑maker also includes administrative managers such as ministers or officials who perform policy‑making discretionary functions within the apparatus of government. Footnote 97

Federal administrative agencies form a “heterogeneous group” and are therefore difficult to categorize. Footnote 98 For instance, in its Working Paper 25: Independent Administrative Agencies, the Law Reform Commission distinguished between different types of economic decision-maker: “regulatory agencies” like the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission and the National Energy Board, designed to “regulate private firms in a given sector of the economy” (in contradistinction to “regulative agencies” like the Competition Tribunal, asked to “further the interests of the state in regulating commercial or industrial undertakings in general as opposed to regulating a particular economic sector”); “Crown enterprises” charged with “promoting commercial and industrial endeavours”; “labour relations board[s]”; “administrative tribunals” which “adjudicate questions regarding commercial or industrial matters”; and the Tax Review Board, which seems to have been considered sui generis. Footnote 99 Plainly, however, these are not watertight compartments and many agencies draw their characteristics from several of the Law Reform Commission’s ideal types.

Benchmarking the Copyright Board’s procedures

For the purposes of the present study, it is necessary to make a choice based on the overall goal of benchmarking the Copyright Board’s procedures against similarly situated bodies. Of interest are what might be described as economic regulatory bodies marked by the following characteristics:

- their decisions are made after an evidence-gathering process (though not necessarily one with the trappings of a trial);

- many parties may participate in the decision-making process, with varying levels of enthusiasm, expertise and procedural protections;

- their decisions are based on consideration of expert evidence;

- their decisions take into account economic and social factors to a larger extent than judicial tribunals that are concerned solely with the application of objective legal standards to established facts; Footnote 100 and

- their decisions are often “polycentric” in nature, designed to “strike[] a reasonable balance among…competing interests”. Footnote 101

At the federal level in Canada, the Competition Tribunal, the National Energy Board, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) meet these criteria, as bodies that are “more…economic or commercial…than…legal” Footnote 102 , marked out by their “independence, permanent nature, the legal and other expertise available to [them], [their] participatory procedures and the broad discretion conferred on [them]…” Footnote 103

For instance, of the CRTC it has been said that it has a “broad mandate of implementing…various different policy objectives, both cultural and economic” found in the broadcasting and telecommunications legislation. Footnote 104 Of the Competition Tribunal, which adjudicates matters arising under the Competition Act, the Supreme Court of Canada has written:

The aims of the Act are more “economic” than they are strictly “legal”. The “efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy” and the relationships among Canadian companies and their foreign competitors are matters that business women and men and economists are better able to understand than is a typical judge. Perhaps recognizing this, Parliament created a specialized Competition Tribunal and invested it with responsibility for the administration of the civil part of the Competition Act. Footnote 105

However, the Tribunal “is different from multi-functional administrative agencies, such as securities commissions” because “policy-making, investigative and enforcement functions” are vested in the Competition Bureau, while the Tribunal “performs the adjudicative functions”. Footnote 106 Nonetheless, its adjudicative role “requires it to project into the future various events in order to ascertain their potential economic and commercial impacts. The role of the Tribunal is thus to identify and remedy market problems that have not yet occurred. This is a daunting exercise steeped in economic theory and requiring a deep understanding of the economic and commercial factors at issue”. Footnote 107 These functions go well beyond simply resolving disputes inter partes by applying rules to facts. Of the National Energy Board, it has been said, “the Board has a large policy-based role and makes polycentric decisions on a variety of different energy issues”. Footnote 108 Finally, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board has a “consumer protection purpose”, Footnote 109 which enables it to modify “technical commercial law definition[s]” Footnote 110 so as to better achieve its mandate, which “includes balancing the monopoly power held by the patentee of a medicine, with the interests of purchasers of those medicines”. Footnote 111

X = yes

|

Evidence-gathering Process |

Broad Participation |

Reliance on Expert Evidence |

Economic and Social Factors |

Polycentric Decisions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Competition Tribunal |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

CRTC |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

PMPRB |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

National Energy Board |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Copyright Board |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Competition Tribunal

The Competition Tribunal is established by section 3 of the Competition Tribunal Act, Footnote 112 which also sets out its jurisdiction Footnote 113 and provides that it may, with the approval of the Governor in Council, adopt rules “regulating the practice and procedure of the Tribunal and for carrying out the work of the Tribunal and the management of its internal affairs”. Footnote 114 The Competition Tribunal has the authority of a superior court of record as to “to the attendance, swearing and examination of witnesses, the production and inspection of documents, the enforcement of its orders and other matters necessary or proper for the due exercise of its jurisdiction” Footnote 115 and it also has the power to award costs. Footnote 116

Pursuant to its rule-making authority, the Competition Tribunal has adopted the Competition Tribunal Rules. Footnote 117 These make detailed provision for discovery of documents, Footnote 118 pre-hearing management, Footnote 119 interventions, Footnote 120 expert evidence, Footnote 121 and service and filing of documents. Footnote 122 Notably, discovery is limited to “relevant” documents, Footnote 123 which must be produced by both parties unless the Tribunal orders otherwise, Footnote 124 a schedule is to be finalized approximately a month after affidavits of documents have been filed, Footnote 125 and significant details as to the management of the process may be set out in the pre-hearing conference:

-

any pending motions or requests for leave to intervene;

-

the clarification and simplification of the issues;

-

the possibility of obtaining admissions of particular facts or documents;

-

the desirability of examination for discovery of particular persons or documents and the desirability of preparing a plan for the completion of such discovery;

-

(d.1) in the case of applications referred to in subsection 2.1(2) and if warranted by the circumstances, the matters referred to in paragraph (d);

-

-

any witnesses to be called at the hearing and the official language in which each witness will testify;

-

a timetable for the exchange of summaries of the testimony that will be presented at the hearing;

-

the procedure to be followed at the hearing and its expected duration; and

-

such other matters as may aid in the disposition of the application. Footnote 126

These rules are, however, subject to the overriding consideration that “[a]ll proceedings before the Tribunal shall be dealt with as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and considerations of fairness permit”. Footnote 127

National Energy Board

The National Energy Board is established by the National Energy Board Act. Footnote 128 Its general powers are similar to those of the Competition Tribunal, with the rider that “all applications and proceedings before the Board are to be dealt with as expeditiously as the circumstances and considerations of fairness permit…” Footnote 129 One interesting difference is that there is express provision for sub-delegation of authority by the National Energy Board to one or more of its members, Footnote 130 in which case the power, duty or function in question “is considered to have been exercised or performed by the Board”. Footnote 131 Pursuant to its statutory authority to do so, Footnote 132 the National Energy Board has adopted detailed procedural rules, Footnote 133 relating to such matters as service and filing of documents and affidavits, Footnote 134 production of documents, Footnote 135 the formulation of issues to be considered (including provision for a conference of the parties), Footnote 136 interventions, Footnote 137 and the conduct of hearings. Footnote 138 These are augmented by soft law instruments such as detailed application forms which must be filled out by interested parties. Footnote 139 Procedural rules may be dispensed with “where considerations of public interest and fairness so require”. Footnote 140 Indeed, in general the rules of the National Energy Board are more skeletal than those adopted by the Competition Tribunal and provide more scope for the National Energy Board to elaborate on them incrementally over time. Information about the National Energy Board’s procedures is accessible via its website, parts of which are evidently geared towards non-expert members of the public who may wish to participate in a matter.

Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board draws its authority from the Patent Act. Footnote 141 It has “with respect to the attendance, swearing and examination of witnesses, the production and inspection of documents, the enforcement of its orders and other matters necessary or proper for the due exercise of its jurisdiction, all such powers, rights and privileges as are vested in a superior court” Footnote 142 and, again, may, with the approval of the Governor in Council, make rules “regulating [its] practice and procedure…” Footnote 143 It may also issue non-binding guidelines. Footnote 144 As with the National Energy Board, all proceedings “shall be dealt with as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and considerations of fairness permit”. Footnote 145 Interestingly, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board has chosen to regulate its procedures by way of soft law, Footnote 146 in the form of guidelines that speak to filing requirements, confidentiality and the Board’s review processes. Footnote 147

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

Finally, the CRTC is established by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act; Footnote 148 it is responsible for the administration of several pieces of legislation, Footnote 149 which also empower it to adopt rules of procedure. Footnote 150 These are set out in the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Rules of Practice and Procedure. Footnote 151 The CRTC may “dispense with or vary” the Rules where it “is of the opinion that considerations of public interest or fairness permit” Footnote 152 and may in addition “provide for any matter of practice and procedure not provided for in these Rules by analogy to these Rules or by reference to the Federal Courts Rules and the rules of other tribunals to which the subject matter of the proceeding most closely relates”. Footnote 153 Nonetheless, the Rules are comprehensive, providing for filing and service of documents, Footnote 154 applications, Footnote 155 interventions, Footnote 156 disclosure of documents, Footnote 157 public hearings, Footnote 158 and pre-hearing conferences. Footnote 159 The CRTC may also award costs, according to fixed criteria. Footnote 160 Interestingly, the evidence at the hearing is circumscribed: “Only evidence submitted in support of statements contained in an application, answer, intervention or reply, or in documents or supporting material filed with the Commission, is admissible at a public hearing”. Footnote 161 These official documents are supplemented by readily accessible information about the CRTC available on its website and social media.

Summary of benchmarking exercise

Some general comments can be made on administrative best practice based on the commonalities in the procedural frameworks surveyed:

- First, flexibility is prioritized. Even those procedural rules adopted by regulation (and with the approval of the federal cabinet) may be dispensed with where it would be efficient to do so. This obviates the need to seek approval for ad hoc modifications to procedural rules. The CRTC’s model, which permits the decision-maker to look to analogous regulatory regimes where necessary, structures this flexibility in a novel way. Moreover, in several regimes, a loose requirement of proportionality has been introduced, with a view to tailoring procedures to the matter at hand.

- Second, detailed procedures usually provide for the management of the decision-making process from the very beginning to the very end. They highlight key stages, such as discovery (which generally seems to follow the filing of a document setting out the key issues) and pre-hearing conferences, which may turn into bottlenecks if not properly managed. Setting out detailed procedures, it ought to be noted, does not compromise flexibility: as long as the rules are understood as a baseline, the decision-maker may depart from them in appropriate circumstances, especially where it would be in the interests of efficiency to do so.

- Third, where there are limits on the disclosure of documents, these are generally couched in terms of relevance to the subject matter of the proceeding, with some decision-makers providing for a more stringent test of necessity.

The Copyright Board’s Model Directive on Procedure Footnote 162 describes the entirety of its decision-making process, from the filing and service of documents, Footnote 163 to the distribution of a final decision “to all participants”. Footnote 164 At some points the Directive is cast in very broad terms. For instance, as to comments: “Anyone may comment in writing on any aspect of the proceedings”; as to interventions: “The Board may allow anyone to intervene in the proceedings”; and as to pre-hearing conferences: “If required, the Board will hold a pre-hearing conference if it may help to simplify or accelerate the presentation of the evidence and the conduct of the proceedings”. But at other points, the Directive delves into the details. The criteria for interventions are laid out at length, Footnote 165 as are the instructions for the filing of cases. Footnote 166 However, although significant detail is given on the discovery process, Footnote 167 there is no obvious sign in the Copyright Act, the Model Directive, or any individual official document prepared by the Copyright Board of any limiting principle of relevance. Footnote 168 Moreover, the discovery process precedes the filing of a statement of case; on this point, the Copyright Board is out of line with comparable bodies. Footnote 169

In general, however, viewed from a comparative perspective, the Copyright Board’s choice of ‘soft law’ rather than regulations to regulate its decision-making process is defensible; its preference for procedural flexibility is widely shared, even by those bodies that set out their procedures in binding regulations; and its Directive is as comprehensive in its breadth as the instruments used by comparable agencies. However, the Directive is not as deep in several potentially critical areas – such as disclosure and case management.

It is worth noting that the Copyright Board is the only one of the bodies surveyed subject to time constraints directly imposed in its parent legislation. The provisions of the Copyright Act requiring tariffs to be filed on or before the March 31 preceding the proposed effective date do not have equivalents in the regulatory regimes surveyed. Although these provisions doubtless produce some salutary benefits in terms of agenda-setting, they also limit the Copyright Board’s ability to set priorities based on its view of how best to achieve its statutory objectives.

X = yes

|

Competition Tribunal |

PMPRB |

CRTC |

National Energy Board |

Copyright Board | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Procedural rules adopted |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Informal procedural rules only |

X |

X |

|||

|

Ability to waive procedural requirements |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Powers of compulsion |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Costs |

X |

X |

|||

|

Formal limits on discovery |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Provision for sub-delegation |

X |

||||

|

Proportionality requirement |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Best practices manuals |

X |

X |

X |

Coda

I should like to add here a final comment about the primarily paper-based analysis undertaken in this section and throughout the present study. Such an analysis may not necessarily capture important differences between regulatory bodies. In particular, different bodies may be faced by different levels of complexity in different fields of regulation. A comprehensive comparative analysis would benefit from a metric developed to differentiate complexity. Such a metric would also take account of resource constraints. Otherwise, one tribunal might complain that oranges are not being compared with oranges – that the complexity of its work is so much greater than that of its nominal peers that comparisons simply cannot be drawn – and outsiders would not be able to judge whether the complaints were justifiable or not.

Halting steps are being taken towards quantifying complexity in the legal world, Footnote 170 but these methods, still in an early stage of their development, Footnote 171 would have been difficult to apply fruitfully in the present study. A comparative study of the resources available to the various administrative tribunals surveyed in this section would, in my view, add little of substance to the analysis without a metric for considering complexity. Further work could certainly usefully be undertaken to develop metrics for administrative-tribunal-benchmarking exercises that take complexity and resource constraints into account in calculating appropriate time periods for decision-making. This work might also assist in identifying decision-makers that are comparatively under-resourced.

Nonetheless, the conclusions of this section and the present study more generally develop a strong prima facie case about administrative best practice. The choice of comparators, explained in detail above, is robust enough to withstand both sustained scrutiny and complaints – if any – about relative complexity and resource constraints. Put simply, the burden is on those whose decision-making processes are subject to important delays to demonstrate cogently why they should not bring their procedures into line with those of their peers.

V. Civil justice reform

What emerges from the recent Canadian literature on reform of the judicialprocess is that providing greater detail about points in the process liable to turn into bottlenecks, allied to close supervision by the responsible decision-maker, has the potential to improve the efficacy of decision-making.

Civil justice reform has been a preoccupation for the Canadian legal community since at least the early 2000s. Footnote 172 The general goal has been to design “a civil justice system that assists citizens in obtaining just solutions to legal problems quickly and affordably”, Footnote 173 with proportionality generally the dominant criterion; “the idea that we should match the extent and scope of pre-trial process, and the trial itself, to the magnitude of the dispute”. Footnote 174 In Ontario, for instance, the Rules of Civil Procedure Footnote 175 “received an extensive overhaul in response to concerns about the inadequacies of the litigation system in Ontario, including inefficient procedure, excessive cost, lack of civility among advocates, long delays and a backlogged, insufficiently resourced judiciary”. Footnote 176 Some of these reforms have met with great success. Footnote 177

These reforms should be of interest to administrative decision-makers. As explained in Section III, administrative tribunals need not ape judicial procedures: flexibility is prioritized in the administrative context, not as an end in itself, but to permit front-line decision-makers to make judgement calls about the types of procedure that would best facilitate the achievement of their statutory objectives. It is notable in this regard that the point of recent civil justice reform initiatives has been to increase the flexibility of the court process. The Supreme Court of Canada has accepted the need for a “culture shift” which “entails simplifying pre-trial procedures and moving the emphasis away from the conventional trial in favour of proportional procedures tailored to the needs of the particular case”. Footnote 178 Administrative decision-makers, with their ability to use flexible procedures to better achieve their statutory objectives, can usefully draw on the reform literature.

An overarching theme of civil justice reform has been “litigation culture”, as the Consultation Paper prepared by Ontario’s Civil Justice Reform Project put it: “Numerous studies in Canada and abroad have identified the adversarial nature of litigation as a key factor contributing to cost and delay in the civil justice system…This emphasis on adversarialism results in demands for more disclosure, more experts, more discovery, more interlocutory motions, and longer trials”. Footnote 179 That “many problems…arise from a culture of litigation that rule amendments would not be able to remedy” Footnote 180 makes it necessary to “shift…ingrained cultural beliefs and practices”. Footnote 181 Of course, “rule changes must be accompanied by strong, consistent and long-term leadership” if they are to succeed in “stimulat[ing] a cultural shift”. Footnote 182

The reform literature targets several areas, beginning with the adoption of simplified procedures, which give parties “the ability to bring motions without filing full motion records and affidavits, a relaxed summary judgment test and early disclosure of documents and witness names”. Footnote 183 However, “the creation of multiple procedural tiers for different kinds of actions increases the complexity of the rules and often fosters confusion” Footnote 184 and is unlikely to be of great utility in the administrative context (where the courts prefer for the whole process to have concluded before adjudicating preliminary or interlocutory issues Footnote 185 ).

More promising for administrative decision-makers are reforms relating to case management, expert evidence, discovery and costs.

Case management

This is “the systematic management process by which a court supervises the progress of its cases from beginning to end”, Footnote 186 perhaps involving “telephone or in-person case conference[s] or a simplified process for motions to be made in writing with or without affidavits…” Footnote 187 It has been noted, however, that “[i]n those cases where counsel can effectively move the case forward, case management adds layers of cost that some convincingly say are unnecessary”. Footnote 188 Some flexibility should ideally be baked into case management, Footnote 189 but an “initial case management conference” designed to set out a road map for progress in the underlying matter would typically include discussion of:

- settlement possibilities and processes

- narrowing of the issues

- directions for discovery and experts

- milestones to be accomplished

- deadlines to be met, and

- setting of the date and length of trial. Footnote 190

Discovery

Ontario’s Task Force on Discovery outlined the concept of “Discovery management”, which has two key features: “discovery planning”, where there is a meeting “early in the case to map out the discovery process”, and “judicial intervention” where there is no “consensus” between the parties, both of which seek to “promote cooperation, ensure complete, timely, and orderly production of documents, clarify the scope of discovery and reduce the potential for protracted disputes”. Footnote 191 This concept of discovery management maps onto two trends in discovery reforms: “The most common trend…is the adoption of rules which place time limits on discovery and even prohibit discovery outright for simplified procedure cases”. Footnote 192 Another trend “involves the statement of a principle encouraging judges to intervene with discovery if it appears to be ‘abusive, vexatious or futile’”. Footnote 193

As to discovery planning, the creation of a discovery plan, usually pursuant to an initial case conference, can “reduce or eliminate discovery-related problems by encouraging parties to reach an understanding early in the litigation process, on their own or with the assistance of the court if needed, on all aspects of discovery”. Footnote 194 A general “Practice Direction” can also be adopted:

It would state that the court may refuse to grant discovery relief or may make appropriate cost awards on a discovery motion where parties have failed to produce a written discovery plan addressing the most expeditious and cost-effective means to complete the discovery process proportionate to the needs of the case… Footnote 195

More generally, the old “semblance of relevance” test, traceable to a late 19th century English decision known as Peruvian Guano, Footnote 196 and which subjects a broad range of documents to discovery, has been supplanted by “a stricter test of relevance”, with a view to providing “a clear signal to the profession that restraint should be exercised in the discovery process…” Footnote 197 Generous discovery rules appropriate to a bygone era are no longer apposite: “‘trial by ambush,’ the original concern, has been replaced by ‘trial by avalanche’”. Footnote 198 Accordingly, the parties have a general duty to ensure that the discovery process is proportionate, Footnote 199 a duty potentially backed up by costs sanctions. Footnote 200 This could in part be achieved by the adoption of a best practices manual. Footnote 201

Expert evidence

The increasing complexity of litigation has made reliance on experts commonplace. With the proliferation of expert reports, however, come challenges for the smooth functioning of judicial decision-making processes:

A commonly adopted expert evidence reform is the stipulation of time limits for the submission of expert reports. The purpose of such reforms is to give parties sufficient time before trial to examine and respond to expert evidence. Furthermore, to increase efficiency, many jurisdictions have standardized the format of expert reports. Reports are also increasingly acceptable at trial in lieu of oral testimony... Footnote 202

As for joint expert reports, the “trend has been to not automatically mandate joint experts, but instead, grand the parties or the court discretion to use a joint expert if desired”. Footnote 203

Pre-hearing conference

Pre-hearing conferences generally involve the preparation of “a detailed trial brief that includes”:

- a summary of the issues

- a list of witnesses and the summary of each witness’s evidence

- copies of the expert reports to be relied on at trial, and

- a list of documents to be introduced at trial. Footnote 204

At the conference, a presiding judge ought to be present Footnote 205 and “may make orders to enhance the fairness and efficiency of the trial process, including”:

- orders limiting time for direct or cross-examination of a witness, opening statements, and final submissions; and

- orders requiring that the direct evidence of certain witnesses be presented by affidavit. Footnote 206

Costs

These provisions for the smooth unfolding of litigation have to be backed by sanctions: “costs rules should be amended to clearly direct courts to consider, in awarding costs at the conclusion of a proceeding, not only what time and expense may be involved in the proceeding but also what time and expense were justified, given the circumstances of the case”. Footnote 207 Efficient case management would be much more difficult to achieve if no means existed of punishing non-complaint parties.

Alternative dispute resolution

I have not considered the recent move towards Alternative Dispute Resolution in the present study. Footnote 208 In my view, caution needs to be exercised with measures such as arbitration, mediation and negotiation, especially where organs of the state are involved. Where public power is being exercised, its exercise ought in principle to be public and open to scrutiny by politicians, lawyers, the media, civil society and members of the community: “open justice is a fundamental aspect of a democratic society”. Footnote 209 Regulatory power ought to be exercised in a way that is justifiable, intelligible and transparent. Footnote 210 It is also worth bearing in mind the comments of the Supreme Court of Canada, regarding the need for more supple judicial procedures, that private dispute resolution procedures are not a panacea, for “without an accessible public forum for the adjudication of disputes, the rule of law is threatened and the development of the common law undermined”. Footnote 211 Accordingly, there is good reason for significant caution in extending alternative dispute resolution procedures to the administrative setting. It is notable in this regard that the Competition Tribunal’s consent orders regime is public Footnote 212 and that agreements of the parties may not simply be rubber-stamped by the Tribunal. Footnote 213 If administrative tribunals are to take steps to foster alternative dispute resolution, these steps should be taken publicly, subjected to informed debate and carefully scrutinized by members of the legal and wider communities.

Summary

Civil justice reform is of interest to the present study for two reasons:

- First, the reforms discussed above represent a relaxation of traditional methods of management of the judicial process; inasmuch as administrative decision-makers prioritize flexibility, they should take note of judicial moves away from tradition and towards more innovative approaches.

- Second, the reforms provide templates that administrative decision-makers can build upon, giving further guidance to those charged with managing various stages of a decision-making process.

In terms of setting out a guide to administrative best practice, administrative decision-makers in general (and the Copyright Board in particular) should provide for the following steps in their decision-making processes:

- Case management: Administrative decision-makers should make generous provision for comprehensive case management processes, especially an initial conference at which the issues in dispute could be narrowed and agreement sought on how best to move through the discovery process. A person could be assigned to case manage a matter as soon as it has been commenced. Care would have to be taken in the administrative context to avoid the common law prohibitions on sub-delegation of power to and accumulation of functions in one single decision-maker, but as long as case management is expressly provided for in statute or regulation, this sort of internal administrative arrangement is unlikely to be undone by the courts.

- Discovery: Administrative decision-makers should restrict the scope of discovery to documents that are necessary to the exercise of their functions, Footnote 214 to ensure that discovery takes place after the filing of a document that sets out the issues to be decided and to develop a best practices manual that would guide parties in their requests for disclosure.

- Expert evidence:Administrative decision-makers should provide expressly for written rather than oral reports, for the possibility of joint experts being appointed by the parties and for timelines within which expert reports should be filed.

- Pre-hearing conference: Administrative decision-makers should hold a pre-hearing conference to attempt to narrow the issues in dispute and develop a timetable for the presentation of evidence and arguments.

- Costs: Administrative decision-makers should have the power to award costs against those who abuse their procedures or otherwise unjustifiably slow down the administrative process. Footnote 215

In my view, such reforms could be implemented with existing resources, though these may have to be reallocated.

VI. Culture change

The importance of culture

Sections IV and V of the present study are useful in identifying benchmarks, first in terms of the stages in decision-making processes and second in terms of the tools available to decision-makers who wish to speed up their processes. In this section, I put these benchmarks in a broader theoretical context, explaining how they might be deployed and to what ends.

Beyond particular reforms which may be of utility to administrative decision-makers, the civil justice reform literature repeatedly emphasizes the importance of culture which may, beyond the formal processes provided for in regulations or ‘soft law’ instruments, explain why some decision-making processes are more effective than others. In short, it may be necessary to find ways of changing the culture of participants. This too is an aspect of administrative best practice.

In general, it is doubtful that there is a magic formula for efficient decision-making, at least as far as procedural rules are concerned. If there are relevant differences in how efficiently equivalent federal tribunals discharge their respective mandates, it is unlikely that these differences are to be found in procedural rules alone. Indeed, my review of the literature on civil justice reform leads me to conclude that culture is critical. That is, where there are bottlenecks in decision-making processes, these may well be caused by the prevailing attitudes of key actors about what is acceptable and what is not. For instance, lengthy periods may be spent in discovery of documents because the parties to a particular matter have a very broad view of what might legitimately be disclosed in advance of a hearing. The task, then, is to equip the Copyright Board with the tools to effect a culture change and give some guidance on how to use them. Footnote 216

I propose that the Copyright Board, Parliament and the Governor in Council expand the range of procedural tools at the Board’s disposal, tools that the Copyright Board can use to craft more effective procedures and shift the prevailing attitudes of the actors that are involved in its decision-making process. Footnote 217

Responsiveness

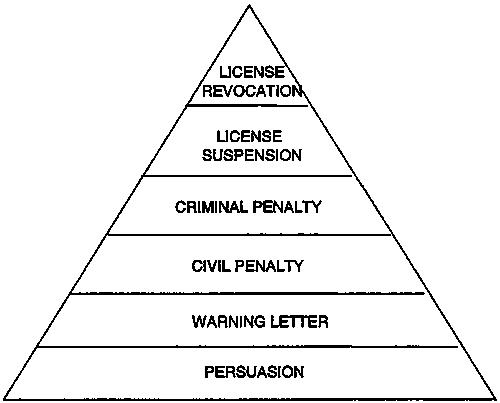

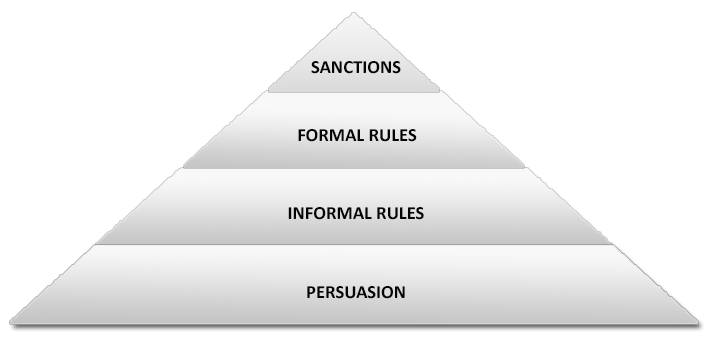

Relevant here is the notion of “responsive regulation”, Footnote 218 in particular the notion of an “enforcement pyramid”: Footnote 219

The point here is that a regulator can try to punish (top of the pyramid) or to persuade (bottom of the pyramid) or use methods in between these extremes to cause actors to change their attitudes and actions. Punishment, however, is a more expensive option, because the procedures required to impose a punishment are generally more onerous and because there is a risk that ready resort to punishment will alienate the actor in question. Persuasion, by contrast, is relatively cheap but, on its own, may not prompt the culture shift sought by the regulator. Accordingly, a responsive approach, with the regulator able to move up and down the enforcement pyramid as circumstances require, is a better means of changing attitudes.

Adapted to an administrative decision-maker’s procedural choices, an enforcement pyramid might look like this:

- At the bottom level, an administrative decision-maker can attempt to improve the efficacy of its procedures by means of persuasion: it could make statements in decisions, for instance, about best practices in the discovery process or what factors individual decision-makers will look to in setting schedules in the context of case management, or it could exhort actors to conduct themselves in a particular way by using its decisions to communicate its expectations;

- Moving up to informal rules, administrative decision-makers can adopt, in the form of ‘soft law’, general frameworks for their decision-making processes, or best practices manuals; these would usually serve as baselines or starting points onto which details of individual cases could be built; indeed, it would be possible to adopt several frameworks, each of which would be adapted to the different types of decision to be taken;

- Moving further up to formal rules, administrative decision-makers could decide to set certain aspects of their procedures in stone; it would be possible for these to function as baselines or starting points, but the general idea would be that certain procedures have to be rigorously respected, with severe consequences – such as inability to proceed any further in the process – following from a failure to comply, unless procedural steps are waived in the interests of efficiency;

- Finally, sanctions, such as costs awards, can be used to punish those who do not comply with the administrative decision-maker’s expectations about culture and conduct. Footnote 220

X = yes

|

Persuasion |

Informal rules |

Formal rules |

Costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Competition Tribunal |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

PMPRB |

X |

X |

||

|

CRTC |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

National Energy Board |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Copyright Board |

X |

X |

Based on my comparative analysis, all the decision-makers studied in Section IV are able to use persuasion and informal rules (though some have had greater recourse to them than others), most of them have adopted formal rules setting out their decision-making processes, and some of them have the ability to award costs. This suggests that administrative best practice would be to permit decision-makers to range all the way up and down the pyramid.

The Copyright Board cannot currently do so. It has no authority to award costs against actors that contribute to inefficient decision-making processes. It has not yet adopted formal rules governing its procedures. It can rely only on its informal rules and its general ability of persuasion – which it has exercised in several of the decisions mentioned in Section II – to improve the efficacy of its decision-making. The Copyright Board’s current efforts, through its Working Committee, reflect the resources currently available to it: acting to change the culture in which it operates, possibly by formulating recommendations for revisions to its informal rules. In my view, expanding the range of tools to formal rules and costs sanctions would better equip the Copyright Board to reduce the tariff-setting delays documented by Professor de Beer.

VII. Summary and recommendations

Summary

Parliament often grants significant decision-making authority to administrative bodies because of the flexibility these bodies have relative to courts and legislatures. Footnote 221 However, flexibility in administrative decision-making is not an end in itself: it is a device which permits administrative decision-makers to better achieve their statutory objectives in an efficient and effective manner.

All of the bodies surveyed in Section IV have provided for some sort of structured decision-making process, usually ranging from an initial statement of case, through discovery of relevant information, Footnote 222 to a final hearing and decision. What emerges is that the procedural flexibility of the bodies studied is bounded, in the sense that a general structure is provided for, along with a power to waive requirements and, sometimes, a duty to tailor the procedures employed to the complexity and stakes of the matter at hand.

The utility of a general structure that emphasizes the importance of managing a matter at various points in a decision-making process is underscored by the discussion of civil justice reform in Section V; in civil procedure, the recent focus has been on providing judges with tools to manage matters efficiently and effectively. The discussion in Section VI emphasizes the importance of equipping decision-makers with a variety of tools that allow them to modify prevailing attitudes. Providing a variety of tools, in a structured yet flexible framework, is an excellent means of capitalizing on the ability of front-line decision-makers to make procedural choices that help them to achieve their objectives in a timely fashion.

Administrative best practice, based on the insights gained from Sections IV, V and VI, requires the adoption of procedural reforms that first, set out various milestones in the tariff-setting process (running from an initial statement of case and case management to a pre-hearing conference and hearing) but that also, second allow for the Copyright Board to modify those procedures where it would be appropriate and efficient to do so would marry the best of (a) common practice among the Copyright Board’s peers and (b) innovations in civil justice reform with (c) the flexibility that characterizes administrative decision-making. Put simply, it would provide a detailed yet flexible structure, within which the Copyright Board could use all available tools, ranging from persuasion to formal sanctions, to reduce delays in tariff setting.

Beyond the recommendations of the present study, it would also be helpful if the legislative and executive branches of the federal government were to commission studies which aimed to develop metrics, sensitive to complexity and resource constraints, to measure the performance of federal administrative tribunals. With such metrics in hand, it would in principle be possible to determine whether providing additional resources would assist in reducing the time taken to render decisions. I am nonetheless confident that the recommendations made in the present study are sound and would decrease the time period for the Copyright Board’s tariff-setting decisions.

Recommendations

First,Parliament should legislate to provide the Copyright Board with a broadly drawn discretion to award costs, along the lines of the provision contained in the Competition Tribunal Act. Footnote 223

Second, the Copyright Board should propose to adopt, with the approval of the Governor in Council, formal rules that provide for various mandatory steps in the tariff-setting process:

- Filing of Proposed Tariff;

- An initial Case Management Conference;

- Exchange of Statements of Case; Footnote 224

- The elaboration of a Discovery Plan (accompanied by a restriction on the scope of discovery);

- Discovery of Documents/Interrogatories;

- A further Case Management Conference post-discovery to determine whether expert evidence is necessary and the means through which this evidence should be received;

- A Pre-Hearing Conference to identify the issues to be determined at the hearing.

It would be prudent to ensure that the Copyright Board has some flexibility to depart from this model where appropriate (especially because transitioning immediately from a flexible process to a tariff-setting process with fixed steps might be difficult to accomplish). Here, the example of the Competition Tribunal, with its power to “dispense with, vary or supplement the application of any of [its] Rules in a particular case in order to deal with all matters as informally and expeditiously as the circumstances and considerations of fairness permit”, Footnote 225 is instructive. It would also be prudent to make express provision for sub-delegation to permit a member – or perhaps even officers and employees – to act in an official capacity in the management of a tariff-setting proceeding. Footnote 226