Creators’ remuneration, livelihood strategies, and use of copyright

Prepared by

Cameron D. Norman PhD MDes CE

Principal, CENSE Research + Design

May 28, 2017

On this page

- Introduction

- 1. Environmental scan

- 2. Primary data collection

- 3. Personas

- 4. Final steps

- The Experimentalist

- The Opportunist

- The Scaler

- The Supporter

- The Adapters

- Creator system map

- Design criteria

- Experiment / evaluation framework

- Ethnography focused on creators’ remuneration, livelihood strategies, and use of copyright: leading to “Creator Personas”

- Appendix

Table of figures

- Figure 1: The Experimentalist

- Figure 2: The Opportunist

- Figure 3: The Scaler

- Figure 4: The Supporter

- Figure 5: The Adapters

- Figure 6: Creator content production system map-Version 2.0

Introduction

This initiative is designed to develop a series of tools that can support stakeholder engagement on issues related to creator support, protection, and copyright issues. As part of the project, a series of personas have been developed based on research undertaken as part of the consultation study on creators’ remuneration, livelihood strategies, and use of copyright.

The project involved a series of steps to collect data and explore the cultural, social, and economic context in which creators operate and how that is influenced by copyright along with exploration into what issues creators have with copyright. Data collection involved an environmental scan, which encompassed reviewing documents from news reports, parliamentary reports, commentaries, and other sources in the public domain where creator issues were discussed, debated, and presented. From that, potential questions were developed to help guide the primary data collection and inform the answers to the questions outlined in the Appendix.

1. Environmental scan

A variety of publicly available sources were reviewed to explore issues related to creator business models, distribution systems, remuneration, and direct the development of the interview guide and sampling strategy.

From that environmental review a few issues or ‘cases’ were identified that helped frame the issue of creators and copyright in 2017. These signature cases underscore some of the key issues that creators face in their navigation of the copyright landscape and examples where creators point to ways to generate a livelihood through new business models.

1.1 Issues with copyright

- Jay Isaac is a Toronto-based artist who created an art project via Instagram under the name “National Gallery of Canada”. The institution by the same name took legal action and had sought to have the experiment terminated. Mr. Isaac has maintained a small section of his website devoted to the project even though its original medium is not available.

- Jody Edwards discovered to her surprise that someone had taken her visual art and transposed it onto clothing for sale at Nordstrom. In a world of global commerce, media, and production, her case illustrates how a creator’s work can be taken and used without permission as well as the difficulties in seeking changes or restitution.

- Nova Scotia musician Maxime Cormier found out that his music was for sale without his consent. The case illustrates the complicated nature of how music is distributed and sold in a digital context, and how creators are often unaware of the ways in which content is shared and sold.

All three creators were approached to speak to the investigator as part of this study and all three declined for different reasons.

1.2 Changing business model

Some creators have commented that the business models they had used in the past would no longer be effective today, while others have leveraged the new media or social landscape to achieve success.

- Singer Matt Good outlines the current state of the music industry in Canada, highlighting the challenges with finding locations to perform and the issues with transparency related to streaming services and remuneration. His message is that he would have a very difficult time making his hit album “Beautiful Midnight” and be successful in the current climate if he was to do it over again.

- Canadian performer Drake released a playlist rather than a song or album to widespread interest. The most streamed artist ever has shown how the new business model of music is connected not to albums, but music more generally. Drake’s collaborations, experimentation, and irregular approach to production and releasing music keeps his audience engaged and interested.

- Canadian-based creator Lily Singh has an international following through her YouTube channel of more than 11.2 million subscribers worldwide. She now has a book deal showing how online, ‘newer’ media like YouTube is creating demand for ‘older’ media like books. Singh’s work illustrates the use of a cross-platform approach to promoting the creator-as-brand as much as the content the creator creates.

These three creators are at the forefront of the Canadian creative industry, illustrating that the previously established business models are becoming more challenging to follow (Matt Good), how existing business models are being adapted (Drake), and how new business models are being created (Lily Singh).

2. Primary data collection

Data collection began in early February drawing on the contents of the environmental scan and helped frame the initial sampling strategy. The original sampling strategy was to interview creators from across a wide spectrum of creative fields and disciplines, stages of career, as well as account for other issues such as sex, regional variation, and language.

2.1 Sample

An initial list of creator-related issues and articles were provided to the consultant who used those to provide an initial set of potential participants. Prospective participants were contacted through various means depending on the material that was publicly available. Additional prospects were identified through social networks and referrals as part of a snowball sampling strategy.

Email, Facebook, and other social media provided the means to reach out to creators. These proved to have varying levels of success.

Creators were identified through the public accounts of their work available through Internet searches that included reviews of social media, other media reports, and reputational examples from mentions in other sources. The focus was on data collected from at least 20 different creators. All creators were interviewed in person, or using the phone or Skype, and the interviews were recorded along with notes taken by the consultant.

The initial pool of potential respondents did not yield a sufficient number of ‘hits’ relative to expectations and therefore some changes in the recruitment strategy was proposed in discussion with the team at Canadian Heritage. The initial sample of respondents were those who were affiliated with relatively newer business models, rather than established artists. These newer business models included things such as extensive use of social media, use of new music streaming technologies, and embracing unconventional forms of public engagement. As a result, the strategy was shifted to focus on early or mid-career creators who are using new or emerging methods of engagement and distribution. This yielded substantially higher response rates for the rest of the study.

2.2 Findings

The interviewees’ responses were remarkably consistent across practice discipline, geography, sex, and other factors. Indeed, the main findings from this project are that there are some very consistent, near universal issues that creators are facing in their attempts to generate an income and to engage with their audiences. Although there were some common threads across all of the creator interviews, there were also distinctions that separated certain practices and profiles out enough that a number of personas were able to be created from the data without difficulty.

The strong findings were a surprise in that it was assumed prior to the data collection that there would be more variation between the different disciplines, forms of creation, roles, and experiences. None of these provided a source of considerable variation from each other and data saturation was achieved early to suggest that there is indeed a creator culture that has robust, shared qualities associated with it. This allowed for the creation of personas that should have strong possible applicability and relevance as accurate reflections of Canadian creators.

The personas reflect some of the major themes that came across in the data. These themes include:

- The challenge of balancing creative work with generating an income. Some of the creators interviewed were doing their creative work full-time; however they were in the minority. Many creators were developing their work as part of a larger set of activities that they were using to generate an income. Sometimes this was done by choice, other times it was done because there was not enough of a market or enough knowledge of the market to fully proceed into that space on a full-time basis. With some exceptions, most creators who were working on their creation part-time did so because they did not have another viable option to do the work full-time. Some creators were also using their work as an opportunity to do something part-time to generate additional income or just as creative opportunities without having to commit to a full-time position.

- This shift in the role of creative work from full-time to part-time, or part-time to casual, reflects a number of factors related not only to the potential to earn income, but also to the technologies available to make creating on a part-time or casual basis possible, yet while doing so at a level of quality and excellence that makes the work appear to be authored by a full-time worker. For example, the consultant interviewed multiple creators who were developing product lines based on their creative work while operating full-time or substantial part time businesses on the side. These businesses however, have a front-facing business model that appears to suggest they are a professional, full-time operation to their audience even if that is not the case.

- On the topic of copyright, most of the creators agreed that it was an issue. However there was some concern over the degree to which individual creators have the ability to ensure that their creative rights were upheld and protected from somebody who had used their work without permission. In nearly every case cited where the creators confronted those individuals, the person who used the material without permission did not know that he or she was taking the work out right. The consistent narrative is that the public is ignorant of what copyright means and what the rules are for using content found online. A recommendation from the creators was to have some means of educating the public to ensure that they know what they can and cannot use online and the means in which to cite, credit, or request the use of content from a creator.

Social media has become an absolutely critical means of engaging with audiences across different creative content areas. As social media are an efficient tool to promote and distribute their work, and engage with and communicate to their audiences, participants from a wide spectrum of cultural industries (fashion, photography, music, visual arts, and writing) highlighted their importance. In some cases social media tools like Instagram provided more than 80% of the traffic and resource revenue for creators.

Certain business models rely almost exclusively on Instagram. In other instances, tools like Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram all played supporting roles in driving traffic to a creator’s website or web store to help them increase visibility and sales of their products. In some cases creators mentioned that without social media they did not see a way to maintain their business. One of the challenges with this approach is that many creators are using or relying on social media properties that they do not own, requiring them to give up certain rights to their content, and making them unable to control the distribution mechanisms through that particular channel. Creators are at the whim of social media algorithms.

- Most creators rely not only on social media, but on a creative community of peers and some form of related social network. In certain cases, there were organizations that served as a brokering or supportive role that was considered to be highly useful to the creator. For example, the “Food Bloggers of Canada” are a group that supports those who are writing in the area of food, recipes, and restaurant reviews. Multiple creators who were interviewed identified this group as a supportive mechanism that allowed them to produce better creative material. The “Food Bloggers of Canada” were interviewed as well along with another creator of a similar role who supports the music industry. It was found that these individuals and organizations provided substantial back- and front-end support to creators enabling them to focus more on creating and less on having to understand the market mechanisms and its dynamics on their own.

2.3 Insights, trends and other patterns

One of the insights that emerged from the data was an understanding of the interplay between creators, their craft, their social community, and geography. This was demonstrated in the mass connections between many creators of different disciplines who operated within the geography surrounding Toronto, from Cobourg to Niagara, shared common interests including the use of social media, and were interconnected through social networks – online and offline. Most of these creators did not know each other when they started their creative work, yet became co-supporters through a shared desire to make and distribute creative content in Canada.

Thus, there was a small, but vibrant community of creators connected to a much larger set of followers and fans who began interconnecting with each other. This created shared value markets where someone who might be a fan of a particular clothing line connects with someone producing home goods, who is connected to a photographer, who might be linked with a blogger. This value chain is tied together by similar aesthetic qualities, but largely by geography. For this reason the potential for expanding the market for these products and ideas, as defined by social connections at least, might be limited.

Geography cannot only be local, but provincial, national, and even international. One creator spoke of the power that his provincial craft guild had to promote work in his province, and provide support for linking creators from the same and different disciplines together in physical spaces (shows) and online. These ‘backbone’ organizations and supporter groups were seen in different contexts, providing another creator space where creators are creating community supports as products. Two interviewees represented these communities.

The main lesson is that these communities are not just assets to creators, but may be vital to their success. Creators spoke highly of the need for opportunities and engagements with peers in spaces where they can relate, often through geography, but also as peers in the same or related industries. This was a space where creators could learn about how to navigate the rather uncertain and rapidly changing ‘seas’ of the market, audience relations, and seek creative inspiration and technical knowledge to support their craft.

On issues of Copyright, most creators had some account of having their content being used without permission. However, the common narrative was that, when those who used copyrighted material without permission were confronted, they expressed unawareness of the rules and laws. Copyright violations were most commonly done out of ignorance of the law, as people thought that because the content was on the Internet, it could be used without needing to do anything.

Creators also spoke with some resignation about not having the energy to try and pursue those using their content without permission. In most cases, creators were resigned to the fact that their material might be taken without attribution or consent, that it was most often done out of ignorance of the rules, and that it was of better use to spend time creating and engaging with audiences genuinely rather than ‘policing the Internet’ for violators.

At times, creators also spoke of some confusion to the practical limitations of pursuing violators related to legal costs, uncertainty of what was a valid claim, and lack of complete understanding of the rules and laws. A related issue, although one that was not as prominent, was the international character of content violations and how some of the violators were based in another country, which would make pursuit of them more difficult.

Another prominent copyright related issue pertained to the creators’ use of copyright themselves and the transparency related to sourcing material. One respondent spoke to the issue around using social media and the need for creators to know the rules, laws, and conventions around promotional content. For writers, many of them had ‘sponsored content’, which were paid promotions from companies and there is a convention that this is fully disclosed. Of those creators interviewed, this was all clear and well-known, but some expressed concern that new entrants to the market were not aware of this and didn’t fully disclose when a piece was informed by or influenced by sponsorships.

Some creators wished they had a better space to learn about their rights and responsibilities as creators. This suggestion was reinforced by the call from many creators to have some copyright resources for them and the public to learn from.

Creators expressed few serious concerns with the current system, resigning themselves to accept certain violations that might take place as noted above without any real suggestion for how the federal government could realistically change this outside of helping educate the public more about creators and their livelihoods.

Creators were generally satisfied with the ways in which the government protected them as much as they felt was reasonable. One thing that they did see for government and policy to play a role in was supporting the advancement of Canadian creators within the market of creative works. One example that was held up was Quebec and their ‘Star Academie’ approach with news shows, talent contests, and high-profile media coverage of Quebec creators that informed audiences about the work being done in the province. The rest of Canada was not seen as supportive through media with an absence of talk shows, media outlets, and promotional ‘spaces’.

Creators mentioned how there were few structural means to promote Canadian content. One suggestion was a ‘Made in Canada’ label that certified products that were designed and manufactured in Canada. Another comment was the absence of small grants to allow Canadian storytelling and promotional work to get off the ground that did not have to rely solely on market tools such as sponsorships, advertising revenue, or sales to support. Many creators wanted to advance a Made in Canada approach and took pride in connecting to the Canadian experience by making unique, Canadian content (products, services, and art).

One creator was grateful for having some initial support provided by a provincial grant that allowed her to explore possible business models as she sought to understand how she could transform her creations into a viable business model and distribute it reasonably to audiences. A major opportunity for the government is to provide a means of promoting and supporting creators in their efforts to develop Canadian products.

2.4 Notable issues: data collection

Some notable issues in the data collection process were identified that influenced the findings:

- Reaching creators was more challenging than expected, particularly those who are in the visual arts who often lack a public facing method of communication that is not tied to something like Facebook. Some creators have a well-articulated public facing website or promotional page, however this was not considered to be universal. This did make communication somewhat complicated because certain channels were better suited to things such as communicating the purpose and intent of the study in sufficient depth.

- One area that has been problematic has been the recruitment of French language creators. The consultants enlisted a colleague who was based in Montréal and had connections with in the arts community in Ontario and Québec. This French language associate reached out through her networks to recruit potential participants. In addition, French language creators were identified through the same mechanisms used for the other participants and messages were sent either by the consultant, translated into French, or the consultant’s associate based in Montréal. A further list of potential sources for French language creators was provided by Canadian Heritage and that list was followed up, including connecting with organizations that support creators in Québec. None of these methods manage to yield a respondent who would agree to participate. It is unclear exactly why this strategy did not yield sufficient representation. It may be that the use of language was not sufficient to provide the appropriate introductory text and dialogue with those creators to engage them enough to entice them to participate. Further research may require different strategies to engage the creator community in Québec, at least the French language community. This also includes the French language community in other parts of Canada.

- As the project unfolded it was expanded to attract First Nations artists as well into the sample. Attempts were made using the same strategy as with the other groups to reach out to First Nations artists where they were identified. As part of the sampling strategy, a number of emails and messages were sent out to those creators with First Nations backgrounds and perspectives, as well as those using new business models. However the consultant was unsuccessful at recruiting a First Nations identified creator to the project. While there were responses, there was not availability to meet with the consultant.

- Another potential limitation to this project was the time compression in which this study was executed and the related tie to the evolving nature of the project. A positive aspect of the project was that there was an openness to modify certain criteria to ensure a sufficiently appropriate sample size that matched the level of depth and variation in the sample. This is a positive byproduct of choosing to focus on emerging creators and newer business models. However, this also may have limited the sample pool for populations like French language creators and First Nations creators who may not be as quick to adapt to these new business models. It is not clear whether that is the case, more research would be needed to verify whether that is true.

3. Personas

Personas represent a data-based ‘fiction’ or caricature construction of a creator to allow an audience to better understand and relate to than something impersonal. Personas are tools to enable people who may be unfamiliar or disconnected from a particular population group to connect to them through a narrative that allows these imaginary, data-based fictional people to be relatable, and reflect real issues and situations. It provides a more accessible means of presenting different aspects of a group compared with other forms of data presentation.

The personas were generated from themes that emerged in data from multiple participants and highlight certain characteristics, which makes up the specific qualities of the ‘character’. The personas were generated from the themes found in the data and used as means to illustrate some of those themes as embodiments within fictional creators. The data from the creators is represented in multiple personas, even if a particular persona might better embody a particular creator based on a set of circumstances. Given the consistency in the data and the dominance of the major themes that was shared across multiple creators this was not a difficult task to do (i.e., generate qualities in a persona).

4. Final steps

The remaining aspects of the data collection are going to focus more intently on the music industry. There are particular qualities related to music and the remuneration as well a livelihood aspect to the domain of the music industry that were identified by Canadian Heritage as being of particular interest. Included in this specific focus on music is going to be interviews with more established creators to gain some better context of what has changed as well as understand their perspective on the current set of circumstances.

The Experimentalist

“I have the freedom to try new things out because my livelihood isn't dependent on being successful at it all. Still, I'd love to see where I can take my ideas and love it when others get exposed to my work.”

Luc's Story: Luc is a 22-year old creator who has been doing artistic work blending graphic design, printing, and art since his early teens. Luc would occasionally be asked to do things like posters, invitations, and even sketch out a friend’s idea for a tattoo. With every project came more referrals. Soon Luc, who is a university student, started to consider that maybe he could make a living from his creative works.

Luc isn’t sure whether he wishes to pursue his creative work for a living, but is currently taking on projects to earn extra money through school. Because his livelihood is not fully dependent on his creative work, he is free to experiment with different media forms, communication tools, and methods of distribution.

He tries out new social media platforms, different live events and is quick to adapt his methods of engagement because his overall investment in each method is mostly in learning. He's also doing his craft part-time to reduce the risk of alienating any particular audience.

Business model: Adaptive. Luc has a website and many social media tools. Many avenues earn little income. His approach is to see what draws the most attention and then seek ways to monetize that. As a full-time student, his income from his creations is a much-welcomed supplement, but not a necessary means of support.

Audience: Emerging. Luc is willing to try new things out to find his audience and has no pre-defined target.

Media: He has tried most of the major social media platforms as well as some newer, emergent platforms. His work is highly visual and lends itself well to tools like Instagram and YouTube. He's also working established channels, too such as face-to-face, shows, and web sales.

Challenges: Luc devotes between 10 and 30 hours per week to his craft, depending on the time of year. His challenge is divided loyalties and commitments with school and his craft. He's not yet sure whether he wishes to pursue his craft full- time, part-time or how he will integrate his career with his creative work.

The Opportunist

“It's amazing to see how simple it is to build a business to develop your creations; the tools are all there. What's harder is finding the way to make it possible to spend the time you want on your creations and still make a living.”

Kirk's story: Kirk (26) is a recent architecture graduate who works independently with clients to help them design their homes and plan renovations. His side passion has always been interior design and he found himself wondering why there were so few products that were designed for his demographic available on the market. He decided to work with some suppliers to design an entire line of home decor products based on his ideas and that are exclusively 'made in Canada'.

Kirk saw an opportunity in the market, a chance to bring his creations to life, and do something he loves as much as his regular job. He's now developed his home decor line into a job that takes about 20 hours a week over and above his regular job as an architect.

Because his regular work is contract- based, the time he has available to work on his home decor business is highly variable, however he doesn't mind as it is, in his words, 'a labour of love'. Still, he would like to spend more time working on his creations and is wondering whether there is an opportunity to take his architecture work down to part-time. His sales keep growing and his ideas for product lines continue to flourish. He's now wondering what kind of creator he wants to be as he continues to fill a demand for the public.

Business model: Kirk capitalized on the use of social media by his peers (millennials) and employed Instagram as a key tool. This allows him to showcase his products visually and promote and sell them through the medium

Audience: Young professionals who are looking to develop their own space and buy a Canadian-made product developed by their peers.

Media: Instagram is responsible for 80% of his sales. He has a website that runs a popular sales tool and he frequently engages in cross-promotions with other creators working in the same space who create complementary products.

Challenges: Kirk is enjoying the ability to interact with others operating in the creative space and sought guidance from a growing number of creatives working in the same city and region as him that are also using Instagram and similar tools. They have established a tight circle of supporters who follow and purchase from this network.

The challenge is that, while this is an active and engaged community, the limits to the growth of it seem tied to geography and focus. If Kirk wishes to devote more time to his creative work, he will need to earn more income from it and that requires a bigger audience.

The Scaler

“I still can hardly believe that this thing I did as a hobby is now generating 1/3 of my family's income and taking up half of my life. I love it, but it is a lot more work than I ever imagined.”

Ana's story: Ana (31) has always been a food lover: a home chef, gardener, and avid restaurant fan. She started a food blog that chronicled this love of food for her friends and family and soon found they wanted more content and kept referring their friends to it. This led Ana to create a Facebook page and branch out into social media. Before long she had an audience that was in the hundreds, then thousands, and now is well into ten thousands of followers, readers, and visitors.

Her blog has since transformed into a full - service website that features reviews, recipes, photographs, and will soon feature videos as well -- all written and produced by Ana. She has had to learn computer programming, photography, and video editing along the way and has enjoyed it.

What started as a hobby is now turning into a small business. Restaurants, food services, and well-known brands have started approaching her to develop sponsored content. She is now working with an agency to help her broker deals that are allowing her to continue to work on creating material. She is now doing this half-time and considering the move to make this her full-time source of income.

Business model: Eyeballs equal monetary potential. Advertisements that run on her blog plus sponsored posts from brands has helped generate enough income that she can work comfortably half-time.

Audience: Consistent, loyal, and growing. Ana's audience is hungry for her food writing, images, and videos.

Media: As desire for more content comes from her audience, Ana's been deliberate about choosing the media forms that best amplify her message quickly: Instagram, YouTube, and Pinterest. She continues to use tools that are likely to reach a larger audience quickly.

Challenges: Ana is pushed by demand from her audience, but uncertainty about whether or not such scaling is proportionately attractive to her message. She finds herself spending an increasingly large amount of time working with different tools and platforms to make more content and wondering how much longer she can continue on her own, whether she needs staff, and what kinds of capital costs.

Her family's income is generated partly from her husband's employment and now she's considering whether she can do this full-time as well.

The Supporter

“You can't make a living in this business the way I did when I was young. Things are changing so fast. What's needed are spaces where people can connect, co-mentor, and learn from each other.”

Andre's story: As a mainstay of the local music scene for more than 30 years, Andre (54) has seen it all. He's been a 'roadie', an active musician having recorded five albums with his band, and toured across Canada. He's part owner of a record store and has managed different artists over the past 15 years, been a concert promoter and also spent three years as a record industry executive.

This perspective has allowed Andre to see new opportunities in a rapidly changing music landscape where music is streamed rather than bought with the exception of vinyl records. He sees the role that merchandising, social media, and licensing all play in shaping the livelihoods for artists today. Andre wants to make sure there is a vibrant Canadian music scene and leverages his extensive connections within that scene and understanding of business to work with artists and new technology developers.

He has created a network that brings together artists, promoters, record companies, technology leaders, and other music supporters to find and develop solutions to preserve and protect music, help musicians adapt to new business models, and make the right connections within the industry to allow musicians to develop.

Business model: Andre's creation is the network platform. This draws attention, sponsorships, membership fees, and enough people to hold training events to earn an income.

Audience: Artists and supporters in the industry who have few other means to connect in an organized manner.

Media: A website and email list are the main tools. Generating artist-relevant content is the main mechanism for communication. A yearly conference and online training events are part of the offerings delivered.

Challenges: Andre plays a number of roles as the host and conveyor of his creator support network. In order to attract interest he needs to create content and connections for the artists, but also for himself, putting him in a conflict at times.

The lower barrier to entry for people into the music business has been an opportunity and limitation. It has meant many more people are joining the network and looking for places to play and showcase their work, however it also means that the quality of the field is more variable and the means to connect the right people to each other is becoming more difficult.

The Adapters

“We realize we only have so many shots at living out our dream of being professional musicians, but it's hard when you have to pay bills and want to build a family at the same time.”

Sameeda and Sandeep's story (S&S): Playing music since they first met in college, Sameeda (28) and Sandeep (30) (S&S as their band name) stayed together, got married and continued to practice the graphic design work that they studied in school. Even though they built their business from scratch, they've always wanted to spend more time on their music.

Last year they recorded their first album, had one of their songs reach regular rotation on the local radio station, and have grown their fan base on social media steadily to more than 4,000 followers. They regularly sell out the small clubs they play in within their region, yet they dream of playing something bigger. Still, the changing music market means they will not make much from their music sales, but need to tour, sell merchandise, and use other means to make a living unlike their musical idols did a generation ago.

Sameeda & Sandeep (S&S) know that if they wish to pursue their craft to the fullest extent, they will need to find ways to generate income from the work beyond just sales. They are exploring teaching music to others, online sales, crowdfunding, and doing increasing amounts of contract commercial work to generate contracts and potential licensing fees as a means to avoid having to do relentless touring, which will take them away from home, particularly at a time when they are considering starting a family.

Business model: Small amounts from radio play and streaming services provide a meagre income. Ticket sales from events, t-shirts, and their creative 'online auctions' for private concerts have all proven to be better sources of revenue.

Audience: Sameeda & Sandeep (S&S) have a strong, loyal following that is growing thanks to their last album. Most of the audience is located within 500 km of where they live and they wish to gain a more national presence.

Media: Like many musicians, Sameeda & Sandeep (S&S) distribute music through all major streaming platforms, radio, YouTube, and connect with a Facebook Page and Instagram account.

Challenges: Sameeda & Sandeep (S&S) are struggling to adapt to a rapidly changing market where record labels, other musicians, and fans are continuously changing their consumption patterns, payment structures, and desires around engagement. The entire industry is being upended by the advent of new means of accessing music and fans desire to access the artists behind the music.

Yet, much of the work required to promote the product takes time and yields no direct income. The result is that Sameeda & Sandeep (S&S) appears to be an emerging band, yet Sandeep and Sameeda find themselves having to continue to pursue graphic design clients to pay bills while they figure out how to make a living as a creator.

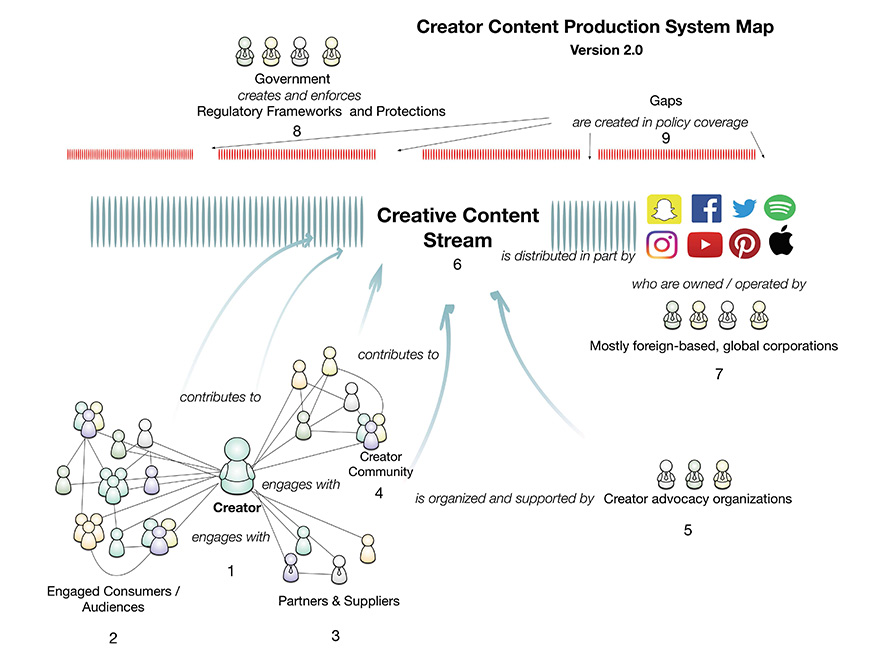

Creator system map

The creator system map is designed to provide a representation of the ecosystem of creators in Canada. The data is based on the ethnographic study of creators from multiple disciplines across Canada who were using new or emerging business models to distribute their work, earn a living, or promote their products.

The data on creators provided a very clear picture of a pattern that is consistent across all of the creator domains, in what might be considered almost an archetype. Creators in 2017 rely heavily on high levels of engagement with a variety of networks that are all collectively engaged in creating content related to the creators’ material. Indeed, there were no obvious variations based on discipline (with some exception for music), region of the country, or size of operation or audience.

This is manifest in something called a “content stream”, which is a mix of digital and non- digital, social and traditional media forms and formats. These new creators rely heavily on social media as a means of promotion and distribution. Every creator uses social media channels of some type to promote and distribute their work.

This map does not represent the creative process, rather the creator’s system of influence and distribution. The key actors and processes in the map are described below with corresponding numbers associated with each one.

- The creator: Is at the centre of production and distribution connected to three primary networks: 1) Their audience, which includes engaged consumers; 2) partners and suppliers; and 3) a creator community of peers. This is the central character in the system and the primary contributor to the creative content stream.

- Engaged consumers and audiences: Are the main groups that the creator is generating products for. These are the fans, the customers, the critics, and the potential audiences who are connected to each other as individuals, as part of small groups and clusters, and provide the primary source of income and the main focus for the creators’ work.

- Partners and suppliers: Is a loosely connected, sometimes disconnected array of individuals and groups that provide the raw materials, networking support, management, and advocacy for the creator. This group assists in ensuring the products are visible, available, and distributed to the various audiences.

- Creator community: Is the peer group of creators working in either the same space or a complementary, or adjacent space and are allies, supporters, collaborators, co-creators, and sometimes competitors. This is very often a community of practice, where creators share insights, cross-promote, connect, and inspire each other.

- Creator advocacy organizations: Are akin to ‘backbone’ organizations that provide support for the field or craft domain, including such things as public advocacy, fundraising, training, network development, and professional development for creators.

- Creative content stream: Is where all of the content generated by the creator and their associated communities related to the creator’s work is shared, exchanged, remixed, and distributed to other outlets. Increasingly, social media platforms are a way for this stream to be carried. Even analog products are distributed partly through social media through taking digital photographs and sharing them online. Music and photography are now largely distributed digitally without a physical correlate of significant value.

- Media outlets: Social media, music streaming services, and online brokerage or hosting services all play a critical role in distribution, audience relations, promotion, and network development. These channels provide a source of revenue, however their control is held by corporations, not the artists.

- Federal government: Helps create conditions that facilitate creator protection and promotion, including shaping the regulatory environment.

- Policy spaces: As time passes and technology and social behavior changes around creators and creative products gaps emerge in the regulatory frameworks that no longer cover all the areas of the content stream. These gaps are where there are uncertainties, confusions, and an absence of appropriate policies and programs to provide support and protection.

Creator content production system map-Version 2.0

Figure 6: Creator content production system map-Version 2.0 – text version

This infographic explains the process of how a creator’s content is produced and shared. The model uses character icons, arrows and numbers for each icon to describe the position in the content production process depicts each person or group.

(1) Creator engages with (2) engaged with consumers/audience and (3) partners and supplies.

The (1) creator engages with the (4) creator community which is organized and supported by (5) creator advocacy organizations.

The (1) creator, (2) engaged consumers/audiences, (3) partners and suppliers, (4) creator community, and (5) the creator advocacy organizations contribute to the (6) the creative content stream. The creative content stream is distributed in part by Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, Spotify, Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest and Apple Music.

Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, Spotify, Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest and Apple Music are owned/operated by mostly foreign-based, global corporations.

(8) Government “creates” and “enforces” Regulatory frameworks and protections for the content.

Gaps are created in policy coverage between the point in which the content moves into the (6) creative content stream and the (1) creator, (2) engaged consumers/audiences, (3) partners and suppliers, (4) creator community and (5) creator advocacy organizations.

Design criteria

This initiative is designed to develop a series of tools that can support stakeholder engagement on issues related to creator support, protection, and copyright issues. As part of the project, a series of personas have been developed based on research undertaken as part of the consultation study on creators’ remuneration, livelihood strategies, and use of copyright.

For Canadian Heritage to develop challenge briefs to support this initiative a few design considerations need to be taken into account. This document outlines some of the criteria that can be used to shape engagement strategies to support co-creative products and solution sets for policy and programs aimed at supporting creators.

A challenge brief can be thought of as a co-design initiative aimed at engaging multiple stakeholder groups in surfacing a problem, framing it in a manner that allows for new thinking to take place on the issue, setting forth a series of steps to generate ideas on how to potentially address the problem, and setting forth suggestions for how the best ideas can be converted into actionable steps to address the problem through a program, policy, or product design.

The aim is to maximize the opportunity for cognitive diversity and focus as well as achieve workable prototypes. A prototype may not necessarily be a finished product, but an actionable plan or product that can be deployed and evaluated in its use to gain insight into areas where improvements or adaptations can be made. These improvements are then re- integrated into the next prototype and the process is repeated until a satisfactory outcome is achieved.

For this current initiative, the brief needs to consider regional differences across Canada, differences in creative discipline, type of business model(s) under consideration, as well as ensuring social diversity (e.g., gender, ethnocultural, language, status).

The design criteria include some general principles as well as a few specific recommendations. A design challenge may include recommendations for specific tools to use (e.g., design media, evidence, resources), which will be determined largely by the scope of the project and the resources available, as well as those participants who agree to respond to the challenge.

The design criteria for the challenge briefs should include:

Principles: Clear statements on the principles of the challenge. These may include, but not be limited to:

- Emphasis on solutions that involve co-design, collaboration, and participation

- Community involvement and public engagement

- Use of evidence (where available)

- Accessibility (ensuring broad accessibility to data, findings, and participation)

Openness: This criteria implies that the solutions generated must not be proprietary, must be accessible to those in the creator community and government, and are amenable to modification and adaptation over time.

Trust: Parties involved must develop trust in each other and the process to participate. Activities that can orient participants to the process, the topic itself, and each other must be included at the start of any challenge.

Transparency: Access to information, resources, and motivations are required to ensure that all parties are aware of what is expected of them and to encourage them to report and share on what they do as part of the challenge, largely so that other teams and Canadian Heritage can learn from what is created.

Diversity: This includes diversity of representation from throughout the system (i.e., the problem domain from creators to policy makers to consumers / audiences). Challenge teams are required to ensure that different perspectives are represented, however the choice to privilege certain perspectives over others can be made on a case-by-case basis. For example, a project with a focus on female creators might have far greater representation of women than men.

Scope: The challenge needs to articulate the boundaries of what is acceptable in terms of focus, resourcing, and other key constraints to ensure that solutions proposed are appropriate, feasible, yet also provide sufficient room for creative possibility.

Space: This criteria is relevant if challenges are to be held at a site-specific location. The available space and related resources is a critical factor in shaping the level of participation.

Team composition: The size and shape of the challenge teams should suit the scope and complexity of the challenge brief. In most cases, it is recommended that the core team be no more than 8-10 members. Note that team composition is not the same as participation, where many more people may be involved in the project throughout the life cycle, just not on the core team responsible for management and implementation of the project. Any additional criteria based on technical, disciplinary (e.g., creator sector), gender, age, regional representation, or other issues can be imposed on team composition.

Experiment / evaluation framework

Introduction

This document provides an outline of a proposed ‘experiment’ that might be used to test assumptions about the use of personas in supporting ‘perspective-taking’ in stakeholder engagement and co-design initiatives.

Personas provide the opportunity to engage different bodies in discussion about issues related to creators and enable different audiences to see what it might be like to be a creator from different perspectives. Drawing on research with creators, the themes generated from observations, interviews, and other data are used to create sample creator ‘models’ that are shared with audiences in a manner that elicits feedback and stakeholder engagement.

Personas are useful as a tool in that they:

- Inform audiences (e.g. policymakers, the public, suppliers) about what creators do and how they live;

- Generate empathy for creators from audiences;

- Build solidarity and support for creators;

- Provide a means of testing assumptions about creators through eliciting feedback on the models provided;

- Explore any gaps in knowledge about creators by eliciting feedback from those in the creative / creator community and generate further questions for research.

This evaluation framework is intended to provide a suggested means of assessing the ability for the personas created by Canadian Heritage to realize the goals above.

Assumption: A program / project / initiative is established to provide a means of re- creating the personas generated from this current research into high-quality, human-scale persona boards that can be publicly displayed and recreated in various other forms (e.g., digital).

Design

Personas are best suited as conversation starters, thus one area for exploration is to create a means of starting conversations by walking a group of stakeholders (e.g., 6-8) through the personas and asking a series of questions of the stakeholders before and after the event.

Groups can be recruited to be intentionally diverse (different stakeholders), homogeneous (focus on a specific sub-group of stakeholders), or done by chance (e.g., convenience sampling) at an event in a distinct space.

Step 1: Administer a pre-test survey individually to participants to determine the current state of knowledge and awareness of creators’ needs and issues. The survey could be done orally, in an informal manner to allow participants to add further details on their responses. Questions may focus on things such as:

- Knowledge of creators’ remuneration amounts and sources of revenue (e.g., estimates of how much creators make, how much time is spent creating, the means in which various creators earn an income).

- Exploration of knowledge and ideas about ‘who is a creator’?

- Engage in myth-busting on such issues as “the starving artist”, “the rock star”, and “the creative genius” through questions that look at what level of agreement there is that they represent the attitudes and beliefs of participants related to how much the personas represent the lives of creators.

- Current activities related to creative product consumption (e.g., art, music, fashion) and co-creation.

Step 2: Walk the group through the personas. This may be all or a sub-set and can be adjusted based on the group that is convened. Show the personas to the participants and have them read through each. Follow-up with a facilitated discussion that allows the participants to ask questions and discuss their experience with the personas. This provides a point to introduce additional information such as details on creators’ remuneration, income sources, business models, and work practices.

Step 3: Conduct a post-discussion interview or survey with participants and explore whether any attitudes or knowledge may have changed. Compare what differences there is when questions are asked. These questions will include:

- Knowledge of creators’ remuneration and sources of revenue (has anything changed?)

- Exploration related to ‘who is a creator’ (what preconceptions were challenged?)

- What myths were supported or challenged?

- How has your understanding of the creator changed? (Alternate: What surprised you?)

- What issues stand out for you as ones that Canadian Heritage should pay attention to?

Data can be compared pre- to post- and also on its own as a qualitative exploration of key ideas and themes.

Ethnography focused on creators’ remuneration, livelihood strategies, and use of copyright: leading to “Creator Personas”

Evaluation and study metrics

The following list of potential metrics were developed to assist Canadian Heritage in developing policy research tools to collect data and monitor the creator space to assist in supporting the work and workers engaged in this space.

1. Revenue, remuneration, and livelihood

These metrics are designed to explore the sources of revenue for creators. These are metrics designed to identify the sources of revenue and the types of arrangements that creators might engage in to derive that revenue from the products of creation.

- Sources of creative distribution (e.g., social media, streaming services, licensing through others, sponsorship)

- Sources of creative revenue (direct) (e.g., streaming / syndication services, direct-to- consumer (digital), direct-to-consumer (physical/retail))

- Sources of indirect revenue (linked) (e.g., partnerships, referrals, certain third-party royalties)

- Alternative sources of revenue (not tied to creator work) (e.g., employment, alternative entrepreneurship arrangements)

- Number and types of business-related partnership arrangements

- Number and types of non-business-related partnership arrangements (may include employment, teaching)

2. Social (media) network and professional connection metrics

Social media was determined to be a primary vehicle for engagement for nearly every creator interviewed as part of the project. Understanding the use of various social media platforms is critical to understanding how creators engage with their audiences, peers, and distribute their work. These metrics are drawn from social network theory and existing research on social media use as well as from the data itself.

Process use

- # of posts / social media channel, including regularity, timing, and consistency

- # acknowledgements and reactions (e.g., Likes, Shares, Comments)

- Amount of time spent / percentage of creative time used in managing social network and related promotional content or interactions

Network influence measures

- Number of peer-related social influencers in network

- Number of consumer-related social influencers in network

- # of direct and indirect connections made through social media tools

- Types of media engaged and networks used

3. Engagement with professional peers

Creators reported reliance on creative peers as a key source of support, co-promotion, inspiration, and knowledge. These metrics explore the activities that creators might engage in with their professional peers, including supporting organizations.

- Co-creation (# and type of products generated)

- Co-promotion (activities done to cross-promote or endorse peers or related products and services for mutual benefit)

- Social referral and co-branding (strategic partnerships based on joint ventures, shared interests, and co-creation activity)

- Engagement with or presence of professional support or advocacy groups within the specific creative sector (work with a backbone supporting organization or other professional groups who support, endorse, or promote creators within a specific sector or region).

4. Copyright

These metrics look at attitudes, beliefs, and experiences related to copyright use.

- Involved in a legal issue (including formal complaint process) regarding copyright as a complainant (Y/N) + Type of complaint

- Involved in a legal issue (including formal complaint process) regarding copyright as a defendant (Y/N) + Type of accusation

- Positive areas of protection and support notes

- Knowledge of copyright protections and services to support creators (e.g., do creators know their rights and can they locate the services and information required related to copyright issues)

- Areas of creative impediments, distribution, revenue generation, and production limited by Copyright

- Areas for potential protection and enhancement with current copyright system

- Areas for future consideration

- Satisfaction with methods of engagement with copyright (e.g., office of copyright, legal protection)

5. Business model issues

These questions look at the revenue streams and associated levels of control creators have over their content.

- What percentage of your total household income are derived from your creative work?

- What percentage of your weekly work hours is devoted to your creative work? (work as defined as time devoted to the creation, distribution, and promotion of your creative products or in an employment or entrepreneurial capacity)

- What profit (if any) is made from your creative work? (Income – expenses related to creative work)

- What control do you have over the distribution channels for your work and the content distributed through them? (e.g., social media)

- What level of ownership do you have over your content? Are you the rights holder for your creations?

- How are you paid through the various distribution channels? How frequently is payment made?

Appendix

Key informant survey

The survey questions listed below are intended to provide a means of collecting data from creators and support an engagement with them on matters of livelihood, creative output, and copyright. This is a sample survey designed to provide guidance on engaging with creators.

This survey has been prepared for Canadian Heritage with the aim of understanding creators’ livelihood strategies, forms of remuneration, and their experience with copyright. All answers will be held in confidence.

For the purposes of this survey, a creator is defined as someone who engages in intentional, creative work that generates art, designed objects, products, and services that are defined by the creators’ interests and market conditions. Creative work is defined as time devoted to the creation, distribution, and promotion of your creative products or in an employment or entrepreneurial capacity.

The term “audiences” or “customers” are used to refer to those that are seeking, receiving, or could potentially be seeking or receiving your creative products, however engaged.

Section 1: Creative work

The following section relates to your creative work and the products that come from it.

1.1 Please describe the creative work that you do.

1.2 What are your sources of revenue from your creative work? (Choose all that apply.)

- Direct sales (e.g. product purchases from audiences or customers)

- Licensing agreements

- Sponsorships and endorsements

- Grants

- Performance fees

- Royalties

- Patent Fees

- Donations

- Other

1.3 What alternate sources of income do you have? Choose all that apply.

- Employment

- Investment or trust income

- Family gifts

- Personal savings (drawing on savings)

- Partner or spouse

- Donations

- Other

1.4 What percentage of your total work time each week is spent on your creative work?

1.5 What percentage of your annual income is derived from your creative work?

1.6 Please indicate the number and type of business-related partnership agreements in place or arrangements you are engaged in. Choose all that apply.

- Manager

- Promoter

- Partner (equal)

- Partner (majority)

- Partner (minority)

- Investor-investee

- Donor / donor recipient

- Client

- Other

Section 2: Product distribution and promotion

The following section relates to your audiences or customers and how your product is delivered and promoted to them.

2.1 Please describe the audiences or customers for your creative work.

2.2 What means do you use to distribute your creative products to audiences or customers? Choose all that apply.

- Direct face-to-face sales / performance

- Catalogue sales

- Distributor or wholesaler

- A website you own

- Another website

- Licensing agreements with other distributors

- Other

2.3 What methods do you use to engage with your audiences or customers? (Choose all that apply.)

- Face-to-face direct engagement

- Shows or events

- Your own website

- Another website

- Snapchat

- YouTube / Vimeo

- Skype / Google Hangouts

- Telephone

- Other

2.4 Please outline the amount of activity among the various media forms used for public engagement that you engage in as part of the promotion and support of your creative work. If a media form is not applicable, leave that line blank.

| Media | # Posts / Week (as applicable) | # Reactions / Week (as applicable) | # Followers / Subscribers / Visits (as applicable) | Avg. time spent per week (hours) | Perceived value to your work (1 – 5 with 1 as the lowest and 5 the highest) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

| YouTube / Vimeo | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Snapchat | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Other social media | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2.5 Please outline the relative percentage that you use each of the various media forms to engage the three different audiences or customers associated with your creative work. If any media is not applicable, leave that line blank. For example, answer how much of your website is used to influence peer social influences vs. how much is aimed at customers vs. partners and suppliers.

| Media | % Peer social influencers | % Audience or customers (including potential audience members) | % Partners and Suppliers (incl. management) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Website | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

– |

– |

– |

|

– |

– |

– |

|

| YouTube / Vimeo | – |

– |

– |

| Snapchat | – |

– |

– |

| Other social media | – |

– |

– |

2.6 In what activities do you regularly engage your professional peers? Choose all that apply.

- Co-creation

- Co-promotion

- Social referral

- Co-branding

- Advocacy

- Other support

- Other

Section 3: Copyright

The following section explores issues related to Canada’s copyright protection system.

3.1 Have you been involved in a legal issue (including formal complaint process) regarding copyright as a complainant in the last 5 years?

- No

- Yes (please explain)

3.2 Have you been involved in a legal issue (including formal complaint process) regarding copyright as a defendant in the last 5 years?

- No

- Yes (please explain)

3.3 On a scale of one to ten, with ten being the highest score, how satisfied are you with the methods of engagement with copyright currently available (e.g., office of copyright, legal protection)?

3.4 Where is the copyright system, as it is now, supportive of your creative work and livelihood?

3.5 Where is the copyright system, as it is now, producing creative impediments or negatively influencing distribution, revenue generation, and production of your creative work and livelihood?

3.6 How can the protection and enhancement of creators be improved through the copyright system?

Section 4: Business model issues

4.1 What percentage of your total household income is derived from your creative work?

4.2 What percentage of your weekly work hours are devoted to your creative work? (Work as defined as time devoted to the creation, distribution, and promotion of your creative products or in an employment or entrepreneurial capacity)

4.3 What profit (if any) is made from your creative work? (Income – expenses related to creative work)

4.4 What obstacles and barriers exist to doing your creative work?

4.5 What facilitates your ability to engage in your creative work?

Section 5: Creator characteristics

Your age today:

Sex:

- Female

- Male

- Transgender

- Prefer not to respond

Years working as a creator in your current domain of practice:

Postal code:

Which of the following groups do you identify (choose all that apply):

- First Nations / Aboriginal

- Francophonie

- Immigrant

- Refugee

- Person with a disability