Literature review on the Canadian art market and the socio-economic conditions of the visual arts market

Final report

For Creative Marketplace and Innovation Branch, Department of Canadian Heritage

April 2018

Preface

This literature review on the Canadian visual arts market was carried out at the request of the team at Canadian Heritage's Creative Marketplace and Innovation Branch (CMIB). Focusing on studies published in the last 10 years, the review examines the economic impact of the visual arts market and the socio-economic conditions of cultural workers, including visual artists. All reviewed publications are listed in the appendix.

The purpose of this literature review was to:

- Examine the structure of the art world and the economic impact of the Canadian visual arts market

- Describe the visual arts supply chain and how it has changed, if at all

- Provide an overview of the socio-economic conditions of cultural workers, including visual artists, and segment data on the market's accessibility to ethnocultural communities such as visible minorities, Indigenous people, women, etc.

- Report any other important consideration found in the literature on the Canadian visual arts market

I sincerely hope the information in this report will be useful to those unfamiliar with the art world and allow the CMIB team to carry on its development efforts with an in-depth understanding of the inner workings of the visual arts market.

Christine Blais

Doctoral Candidate in Art History and Market Studies

On this page

- Preface

- List of acronym and abbreviation

- List of figures

- Highlights

- Difficulty of finding data on the visual arts market

- An opaque market

- Growth of private sales

- Challenges of art galleries and dealers

- Impact of digital platforms on direct sales by Inuit artists

- More art collectors, less spending per artwork

- Cultural diversity and gender equality

- Better understanding the practices of Indigenous and minority artists

- Increased presence of Indigenous art in traditional distribution networks

- The socio-economic conditions of cultural workers can be as precarious as those of artists

- Methodology

- Introduction

- Part 1 – Distribution networks

- Part 2 – The visual arts market

- Part 3 – Socio-economic conditions of cultural workers

- Appendix

- Bibliography

List of acronym and abbreviation

- ACE

- Arts Council England

- ADAC

- Art Dealers Association of Canada

- AGAC

- The Contemporary Art Galleries Association

- CALQ

- Conseil des arts et des lettres du Quebec

- CCA

- Canada Council for the Arts

- CENSUS

- Canadian proram to draw a statistical portrait of the country every five years

- CMIB

- Creative Marketplace and Innovation Branch

- CSA

- Culture Sattelite Account

- IAB

- Iqaluit Auction Bids

- MAC

- Montreal Art Council

- MCC

- Ministère de la Culture et des Communications

- NADA

- New Art Dealers Alliance

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NHS

- National Household Survey

- OCCQ

- Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec

- RAAV

- Regroupement des artistes en arts visuels du Québec

- SSHRC

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council

- TCI

- TCI Management Consultants

- TEFAF

- The European Fine Art Fair

List of figures

- Figure 1: Visual arts ecosystem model (McIntyre 2004, 6)

- Figure 2: Artist profiles map (Sagot Duvauroux and Moureau 2012, 51)

- Figure 3: Public museum representation by culture (Maranda 2017)

- Figure 4: Gallery representation by culture (Maranda 2009)

- Figure 5: Gallery representation by gender (Maranda 2014)

Highlights

Difficulty of finding data on the visual arts market

Much research remains to be done on the art market. Unfortunately, because of its opacity, it can be particularly difficult to obtain exact figures measuring the contribution of the visual arts to the Canadian economy. Most surveys use different or incomplete methodologies. Some studies on the visual arts market had to be suspended due to a lack of cooperation from market players (Routhier 2006) or a lack of raw data, in particular as a result of changes to Statistics Canada's "Survey of Household Spending" and the drop in culturally relevant data (Hill Strategies Research 2016).

An opaque market

The opacity of the visual arts market makes it very difficult to obtain data. Because of the anonymous nature of transactions, data obtained from research is often incomplete. As such, a significant amount of extrapolation is required to get usable data. It is very difficult to assess the market value of the visual arts.

Growth of private sales

The "TEFAF Art Market Report 2017" highlights a change in the supply chain of visual arts products at the international level, with transactions shifting from auction houses (public sales) to galleries and other private stakeholders (Pownall 2016). This is due to growing demand from collectors favouring opaque transactions, concerned about global socio-economic developments (Brexit, American politics, etc.) and above all, in search of greater anonymity. Auction houses are also increasingly offering private sales services (Pownall 2016; McAndrew 2017).

Challenges of art galleries and dealers

The gross revenues of art galleries vary widely and most dealers and private galleries post marginal profits of 10% or less (negative) mainly due to high operating expenses to ensure mediation work (physical space, fairs, payroll). As Routhier (2006) points out, income diversification is often necessary and many businesses are forced to rely on other sources of income such as appraisals, framing, publishing, etc.

Impact of digital platforms on direct sales by Inuit artists

While wholesale suppliers and dealers remain important platforms for Inuit art sales across Canada and internationally, direct-to-consumer transactions have soared in recent years owing to digital platforms, which have made selling artworks and handicrafts much more profitable for these artists. This has enhanced their quality of life, especially considering the extremely high cost of living in the North (Big River Analytics 2017).

More art collectors, less spending per artwork

The Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communications' (MCC) quinquennial survey of cultural practices reveals that 7.4% of Quebecers acquired a work of art in 2004, 11.6% in 2009 (Audet et al. 2009), and 26% in 2014 (MCC 2016). However, though this data should be taken with a grain of salt given the methodological framework, the "Survey of Canadian Household Spending from 2012 to 2016"shows that Canadians are spending less and less per work of art (including antiques and decorative items): $100 in 2012, $82 in 2013, $87 in 2014, $75 in 2015 and $78 in 2016.

Cultural diversity and gender equality

Maranda (2017) makes it clear that the cultural industry still has a long way to go with respect to cultural parity and pay equity between men and women. Women working in cultural institutions earn on average 20% less than men despite outnumbering them. According to the researcher, women are also less likely to be in leadership positions. Parity is also lacking in the visual arts distribution industry: while a majority of living artists are women (over 60%), only a small proportion of them are represented by galleries (Delgado 2018; agYU 2014). While the Canadian population is becoming increasingly diverse, cultural institutions have lagged behind, whether regarding staff, independent curators or artists (Maranda 2017).

Better understanding the practices of Indigenous and minority artists

Indigenous and minority artists often face the same problems. These include having difficulty achieving professional status, lacking visibility, not being fairly recognized (Uzel 2017, 9, 51) and feeling discouraged (Uzel 2017, 57–58). Conversely, they differ in other key aspects such as mixed techniques and media, cultural heritage and the notion of "contemporary" (so often opposed to "traditional"). Multimedia practices, which often include traditional techniques, are not always as appreciated by the community as they are by sponsors. Consequently, better peer representation on selection committees and panels is recommended to foster a better understanding of these practices (Uzel 2017).

Increased presence of Indigenous art in traditional distribution networks

Maranda (2009) reveals a substantial improvement in gallery representation (from 16% to 47% in 2012) and level of education among Indigenous artists, which may be connected to growing average incomes and, according to researchers, may also be evidence of a trend.

The socio-economic conditions of cultural workers can be as precarious as those of artists

It is well established that artists have low incomes and that still holds true, though the situation has improved overall. That said, the literature shows that some indicators apply to cultural workers as well (Azoulay & Paradis 2018; Maranda 2017; Hill 2014; AGAC 2016). While a majority of visual arts professionals have post-secondary degrees, they still earn less than the average Canadian worker. Many do not have regular employment, temporary jobs being more common (according to Azoulay and Paradis [2018, 10]; there are now almost three times more cultural workers holding more than one job than there were in 1990).

Methodology

This review was carried out over a period of nine (9) weeks, from February 26 to April 27, 2018. It focused on recent literature, i.e., published in the last decade (with some exceptions), covering both mainstream and specialized media. Three main types of documents were consulted: very recent articles (newspapers, specialized magazines), theoretical works and research and survey reports (e.g., Statistics Canada, the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec (OCCQ), Hill Strategies). References are cited in-text using the author-date system and consulted works are listed in the appended bibliography.

Since the Canadian art market and its economic impact are seldom discussed in academic literature, most of the works consulted were articles from periodicals or reports from cultural or government organizations. Some academic publications are included in the report to address certain fundamental and major theories that help put the data into perspective and make it easier to understand the dynamics of the art market and industry (symbolic economy, fields and spheres of art, etc.).

Some works were recommended to Canadian Heritage in fall 2017 in the context of broader consultations with Canadian cultural professionals. These include "Waging Culture: A Report on the Socio-Economic Status of Canadian Visual Artists", by Michael Maranda (2009), and "Les artistes en arts visuels – Portrait statistique des conditions de pratique au Québec", published by Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec in 2010 (Routhier 2013b). These works appear in the bibliography, preceded by an "(R)" for "recommended."

Throughout the literature review on the Canadian visual arts market, we tried to use sources from across Canada or sources that would allow us to provide a representative analysis of the whole country and/or address specific situations in each province, as the case may be. However, the research communities in Quebec seem to have been particularly productive and proactive in collecting and analyzing data. The Institut de la statistique du Québec's Observatoire de la culture et des communications (OCCQ) has produced various surveys providing valuable information, in particular with respect to the acquisition of artworks by Quebec institutions, businesses and municipalities (Routhier 2015, 2013a, 2011, 2006) and the socio-economic conditions of cultural workers, including artists (Routhier 2013b, 2013c). Also, with all the public consultations being held with a view to updating Quebec's cultural policy (2016), several organizations have released briefs of interest to this study.

Given the paucity of information from Canadian sources, some international studies were used to assess the economic weight of the Canadian art market (for example: McAndrew 2017, 2018; Pownall 2017; Deloitte 2016). Other international studies are also referenced, in particular regarding the cultural products distribution chain (McIntyre 2004; Dalhoff 2017; Belting 2013), the issues facing cultural entrepreneurs (Resch 2016; McAndrew 2018) and academic publications on the fundamental theories of the art world (Moulin 1992, 2002; Moulin & Quemin 1993; Moureau & Sagot-Duvauroux 2012; Benhamou 2011; Hutter & Thorsby 2008), as they provided valuable theoretical and global perspectives.

Given the scope of the review and the short timeframe to carry it out, only the latest and most important works directly related to the mandate were selected for "laymanization." The goal was to provide a broad and detailed analysis of the four priority areas set out by Canadian Heritage (listed in the preface). This literature review is intended to be unbiased and free of professional opinions and personal judgments.

Final report

Literature review: the Canadian art market and the socio-economic conditions of the visual arts market

Introduction

David Heffel, President of Heffel Fine Art, said in a 2016 interview that "the Canadian art market is at a new level. Maturity is a thing that comes to mind, collectors are now thinking about new ways to share their collections with the public and we're also seeing a sophistication develop in our marketplace (Craig 2016)." Local artists across the country seem to be getting more visibility from various audiences, in particular thanks to museum exhibitions, which are trending up, and major investments in public works by businesses and municipalities. Canadian private and corporate collectors are also increasingly active, getting media coverage and making their collections available to the public through private museums or public exhibitions. Canadian artists have also been getting more attention on the international scene in recent years. The same goes for high-profile biennial events and art fairs, where Canadian artists and businesses (galleries and dealers) have been enjoying greater visibility. So how is the Canadian art market doing in this context and what issues and challenges are Canadian artists and workers currently up against?

Very few comprehensive studies have been done on the art market. This review does not aim to offer a new perspective on the matter or to further the research, but rather to provide an in-depth look at the inner workings of the Canadian visual arts industry over the last ten years. Before delving into the review, which is broken down into three parts (distribution networks, the art market and socio-economic conditions), we should start by defining some key concepts that form the theoretical framework of the study.

The art market is often simply divided into "primary" and "secondary" segments that are clumsily associated with contemporary or earlier art. The primary segment refers to artists' initial sales, whereas the secondary segment refers to subsequent sales (resales). In reality, the market should probably be thought of as a set of markets, each representing a type of art or area (when viewed from an international perspective). However, the dynamics of the art market, as discussed in this study, are more complex.

Known for her trailblazing art market research, sociologist Raymonde Moulin (1992) distinguishes three main markets. The "chromos" market, initially defined by Quebec professor Francine Couture in her thesis in the early 1980s. "Chromos" works are generally mechanically produced studio paintings with no real artistic intentions on the part of the artist other than to meet consumer demand for themed artwork. They are usually "good quality but stereotypical decorative items manufactured for a monopolistic competition market with a wide audience and an abundant supply (e.g., artwork sold in big box retail stores and decorative pieces)." Then you have the "classified works" market, i.e., sure-value items that "history has already passed judgment on and have a fixed supply." The third market category, contemporary and current works, has a more fluid supply. Cultural economist Françoise Benhamou specifies that the last two markets are small and have very few stakeholders to distribute and legitimate artwork (i.e., accept it into the market) (Benhamou 2011, 43).

Legitimation network

Economic historian Stefano Baia Curioni has recently determined that the contemporary art appraisal process is governed by a complex and dynamic network of actors (Baia Curioni, Forti & Leone 2015). They are today, more than ever, mobile actors in an international art market (Moulin & Quemin 1993; Baia Curioni, Forti & Leone 2015; Belting 2013), and private galleries play a key social role in these international networks, in particular owing to how important art fairs and major exhibitions are to the art market. In parallel, it is important to understand the role of artwork legitimation networks, i.e., consensus-building stakeholders that recognize current artistic practices. Benhamou refers to these networks as "tastemaker communities," a caricatural term for the art world's legitimation authorities, who hold great sway over the symbolic value and social capital of artwork: dealers, critics, curators, commissioners-curators, the research community, along with some high-end collectors and mega-galleries or "leading galleries" (Moulin 1992), which are highly influential private galleries with hybrid business models, i.e., crosses between commercial galleries and museums.

The concept of symbolic value

In the art world, the value of works cannot be determined from a purely financial or economic perspective. Economics cannot be the only guideline for assessing the value of art. As posited by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu: "all the calculations in the world have no hope of even remotely improving our understanding of what exactly makes a work of art valuable and desirable (Bourdieu 2000, 24)." That is where symbolic value comes in—the symbolic value attributed to works, artists and provenance, for example, can help explain how prices are determined (Velthuis 2007). Bourdieu indicates that "this is clear in areas like the [...] artistic field, where social production mechanisms of non-economic interests—in the strictest sense—are governed by laws unrelated to economics [...] (Bourdieu 2000, 23)." Thus, in the art world, price does not equal value. A 2017 study conducted by art insurance specialist AXA Art made that point clear: a quarter of interviewed European collectors believed that the price of an artwork had no correlation with its value, with most of them feeling that the prominence of the artist and emotional attachment to the artwork were more important factors in the decision-making process than price (Dalhoff 2017, 23).

The art world network is therefore vital to establishing the value of artwork but is not quite the same as the (commercial) visual arts distribution network. The distribution network can be boiled down to a few types of stakeholders, which will be addressed in the following pages, such artist entrepreneurs, commercial galleries and auction houses. The profitability of these businesses and cultural organizations varies (Azoulay & Paradis 2018), and we will try to shed some light on the issues these principal entrepreneurs face. In addition, we will discuss two platforms that have grown considerably in recent years: fairs and digital technology. We will also examine how distributors are changing their business models, in particular with respect to public and private sales.

The second part of the report will analyze studies that have attempted to assess the Canadian art market's economic impact. It should be noted that these studies are greatly limited by the opacity of the art market, which makes finding financial sales data very difficult. Consequently, the figures obtained by the researchers should be taken with a grain of salt, as they were likely arrived at, at least to some extent, through extrapolation. The methodology of each study will be detailed as much as possible so readers can judge for themselves.

The third and final part of the report consolidates recent studies on the socio-economic conditions of cultural workers in the visual arts. Although the issues of non-artist workers are often highlighted, few studies address them. Research is limited in this area, and future studies should be more comprehensive. On the other hand, there is plenty of source material on the socio-economic conditions of visual artists, in particular minority and Indigenous artists, thanks to growing government concerns regarding cultural policies and institutions increasingly emphasizing cultural parity in their programming (Maranda 2017).

Part 1 – Distribution networks

1.1 Supply chain

According to Baia Curloni, the art market is a networked environment where insiders and outsiders meet and supply does not follow demand—rather, supply drives the exchange system (Baia Curioni 2014, 38). The challenge of summarizing the visual arts supply chain is describing it. To quote the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec (OCCQ), the supply chain is not the same for "museum artists as it is for others (Routhier 2013b)."

The term "museum artist" used by the Observatoire (OCCQ) is very appropriate because, as we saw in the introduction of this report, the cultural products supply chain is not only driven by the distribution of products (artwork), but rather by a set of conventions specific to the art world whereby museums legitimate the symbolic value of artists and their work. Many publications have attempted to define the cultural product supply chain, but none has taken into account the theoretical framework specific to the art world network (Rivest 1992; Dalhoff 2017).

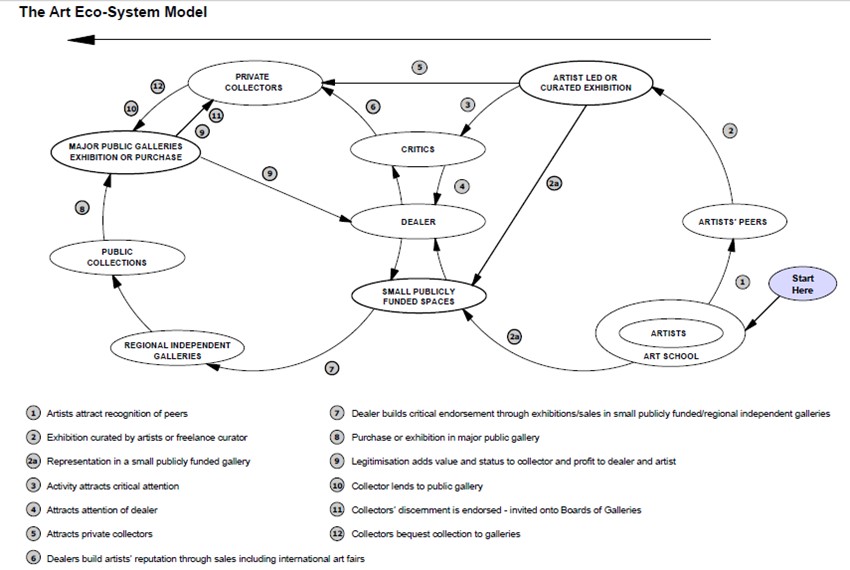

That said, in a study commissioned by Arts Council England, McIntyre (2004) put forward a more than adequate diagram illustrating the visual arts production and distribution network, although it could use an update considering its publication date (Fig. 1). McIntyre's simple model of the professional visual arts ecosystem is perfectly suitable for our purposes.

The proposed ecosystem is structured as follows:

- Artists grow and develop in their academic environment, where they build their peer network

- They then participate in typically curated exhibitions

- This visibility and recognition within the cultural community can provide access to the distribution network, including dealers (galleries, fairs) and publicly funded spaces

- Galleries can generally use their network and business connections to get artists into public and corporate collections

The model shows how the artwork of all artists, whether living, emerging, established or even deceased, contemporary or not, makes its way through legitimation networks. Of course, in the case of resales, works are traded between sellers and buyers. To complete the diagram, another stakeholder would have to be added where the two circles meet: the auction house.

Figure 1: Visual arts ecosystem model (McIntyre 2004, 6) – text version

The visual arts ecosystem model is a graphic representation of the environment visual artists exist in.

The model uses arrows and circles to show how artwork makes its way through legitimation networks.

At the bottom of the model is a numbered list of parts of the network. Those parts are associated in the diagram with corresponding features and outputs.

Part of the Network Corresponding Feature Corresponding output 1 Artists attract recognition of peers Artist and Art school Artists' peers 2 Exhibition curated by artists or freelance curator Artists' peers Artist led or curated exhibition 2a Representation in a Small publically funded gallery Artist led or curated exhibition Small publicly funded spaces Artists and Art school Small publicly funded spaces 3 Activity attracts critical attention Artists led or curated exhibition Critics 4 Attracts the attention of dealer Critics Dealer 5 Attracts private collectors Artists led or curated exhibition Private collectors 6 Dealers build artists' reputation through sales including international art fairs Critics Private collectors 7 Dealer builds critical endorsement/sales in small publicly funded/regional independent gallery Small publicly funded spaces Regional independent galleries and public connections 8 Purchase or exhibition in major public gallery Public connections Major public galleries exhibition or purchase 9 Legitimation adds value and status to collector and profit to dealer and artist Major public galleries exhibition or purchase Private collectors 10 Collector lends to public gallery Private collectors Major public galleries exhibition or purchase 11 Collectors' discernment is endorses – invited onto Boards of Galleries Private collectors Major public galleries exhibition of purchase 12 Collectors bequest collection galleries Private collectors Major public galleries

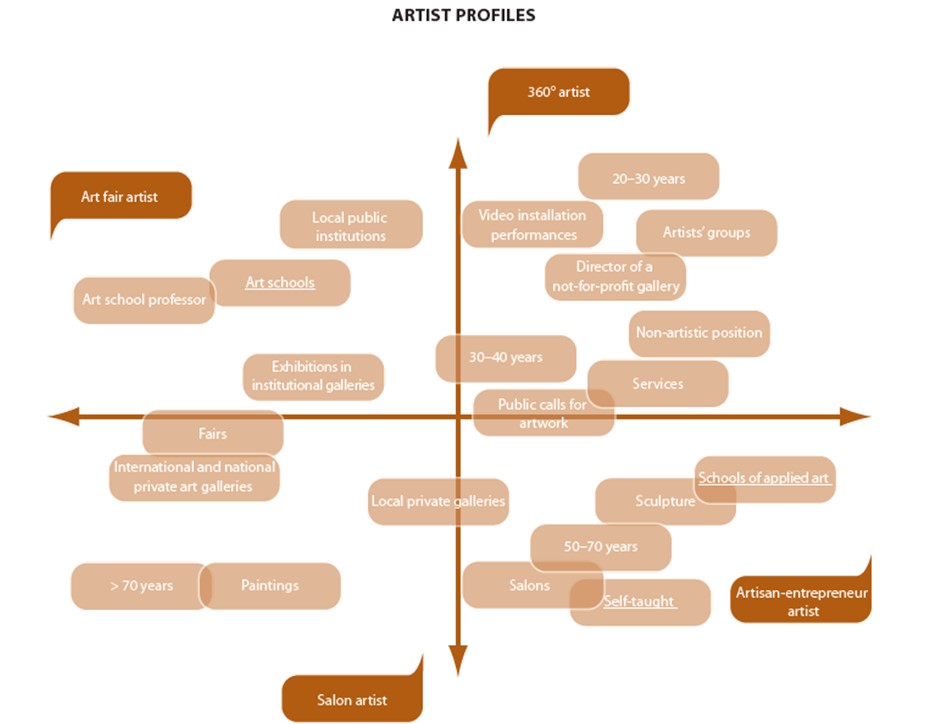

According to Dominique-Sagot Duvauroux and Nathalie Moureau (2010), there are basically four distributor segments, each corresponding to very distinct artist profiles (Fig. 2) providing context for McIntyre's "dealers."Footnote 1 On one hand, you have the mass-produced items the authors call "mass consumer products," which can be likened to the aforementioned "chromos" and can include commercial Indigenous artwork (Big River 2017; Nordicity). This is the market of "artists in the process of legitimation"—typically young artists who have yet to be accepted by traditional legitimation and distribution networks. These artists generally try to build their reputation online and through low-profile artist and exhibition centres. They can be generally targeted by emerging galleries with innovative business models and medium-sized galleries, who take some of them under their wings. Medium-sized galleries are the biggest segment in the commercial ecosystem. Typically run by a manager (often the owner) and a few employees, these galleries seek to showcase a good mix of emerging and more established artists more likely to appeal to collectors. Sagot-Duvauroux and Moureau also distinguish the "high-profile vanguard" market, which includes the relatively few "360o artists" (multidisciplinary and innovative) and "fair artists" (commercially successful with current works responding to demand) with established reputations, access to the institutional market and fairly speculative values. These artists generally start out in mid-level galleries and work their way up to mega galleries, highly commercial establishments providing artists with strong sales and international exposure from participation in various events. These galleries have considerable operating budgets and are often financially supported by patrons. Lastly, Sagot-Duvauroux and Moureau identify an "established talent" market, typically a secondary market for recognized living or dead artists, i.e., for works having entered into history and institutions (Savot-Duvauroux and Moureaux 2010).

-

Figure 2: Artist profiles map (Sagot Duvauroux and Moureau 2012, 51) –text version

This infographic displays profiles of artists through a graph.

In each quadrant are text bubbles with text describing types of artists.

The first quadrant is labeled "360 degree artist". In this quadrant are the following descriptions that reflect these artists:

- 20-30 years

- Video installation performances

- Artists' groups

- Director of a not-for-profit gallery

- 30-40 years

- Non-artistic position

- In the services

- Public calls for artwork

The second quadrant is labeled "art fair artist". In this quadrant are the following are descriptions that reflect these artists:

- A part of local public institutions

- Art school professors

- Involved in Art schools

- Have their exhibition in institutional galleries

In the third quadrant are the "salon artist". In this quadrant are the following descriptions that reflect these artists:

- Involved in fairs, international and national private art galleries and local private galleries

- > 70 years

- Paintings

In the fourth quadrant are the "artisan-entrepreneur artist". In this quadrant are the following descriptions that reflect these artists:

- Self-taught

- Schools of applied art

- Main art form is making sculptures

- Display their work in local private galleries and salons

- 50-70 years

1.1.1 Artist entrepreneurs

In 1992, Rivest defined artists as "creators, designers, etc., and professionals in control of their own work. As such, they are ultimately responsible for the direction their careers and businesses take (Rivest 1992, 5)." Artists nevertheless receive plenty of advice and guidance from stakeholders in the art distribution network, which Rivest calls the "integrated distribution network." This definition of the professional artist still holds true today. However, both artists and the network have become professionalized, as we will discuss in Chapter III on the very high level of education of today's artists.

Unfortunately, very little public information was found on the realities of artist entrepreneurs or their involvement in their own market. Routhier (2013b) pointed out that a large proportion (3/4) of Quebec artists are self-employed and that 31% of them have their own business (Routhier 2013b, 75).

A survey by Big River Analytics (2017) shows that for Inuit art, the link between the artist and the buyer has recently greatly expanded owing to digital platforms. Most sales by Nunavut artists are now made directly to consumers. This has made selling artworks and handicrafts much more profitable for these artists, especially considering the extremely high cost of living in the North.

Artists also have access to many professional platforms where they can market their works themselves, including fairs like The Artist Project (Toronto), La Biennale de Québec, the Saint-Lambert fair, and a project to launch in 2018, the Marché émergent fair, set up by Carrefour jeunesse-emploi du Centre-Ville (Montreal) in collaboration with prominent Montreal cultural organizations.

In addition, members of some artist associations often have access to low-cost training and workshops aimed at developing their business knowledge and skills. Artist centres also showcase their members' work at some of the events they organize, such as fundraising sales and auctions.

1.1.2 Commercial galleries

Art sociologist Nathalie Heinich once said that contemporary art has "expanded the frontiers of art so much that it is now accessible only to those who have managed to enter its well-defined world, which is no longer penetrated through the contemplation of objects [...] but through the stories that surround them, that is, the people who tell them." That is why gallery owners play such an important role—they are not just distributors, but also mediators. Dominique Sagot-Duvauraux and Nathalie Moureau classify gallery owners, the champions of contemporary art, as "promotional galleries," as indicated above.

In 2016, the Contemporary Art Galleries Association (AGAC)Footnote 2 conducted a study highlighting some of the issues encountered by private contemporary art galleries. Their findings on average revenues are consistent with those of other studies, i.e., gross revenues vary greatly from one gallery to another: from $40,000 to nearly $2 million. Correspondingly, Pownall's analysis of NAICSFootnote 3 data covering roughly the same period shows that the vast majority of dealers and private galleries (>1,000) generate less than C$500,000 in revenues and about 300 to 400 businesses generate $500,000 to $1 million (Pownall 2017, Fig. 117). These figures may seem impressive, but keep in mind that these are gross revenues.

The commercial practices of private galleries are fairly similar in the sense that the business models of most of these companies—be they large, medium or small—are governed by certain conventions. Their role of promoting artists and marketing and disseminating their work has traditionally involved maintaining an inventory, covering promotion costs (catalogue, vernissages, etc.) and providing mediation services (employees, premises with fixed opening hours, etc.). International fairs have gotten bigger and bigger since the 1990s, and gallery owners have been investing significant sums to participate in these events and try to develop new markets (Resch 2016; AGAC 2016; Winkelman 2015; Pownall 2017). These conventions are followed by virtually all gallery owners showcasing current, contemporary or older works. Resch (2016) has suggested that the budget items that hurt the profitability of art dealers and galleries the most are location and fairs—both major expenses. AGAC (2016) shares this opinion, and considering all the Canadian galleries that have closed in recent years, the situation seems to be similar across the country.

Art galleries and dealers around the world are mainly concerned about the following issues: finding new customers (71.78%), consigning new works/increasing their inventories (49.5%), fair and exhibition costs (49.01%), financial profitability capacity (46.04%) and maintaining and retaining customers (43.07%) (Pownall 2017, 52–55). While many of the entrepreneurs running many of these more traditional small- and medium-sized businesses are certainly well versed in the visual arts, they often lack management training, which can explain their low profitability (Resch 2016, 49).

It should be noted that when working with living artists, gallery owners and artists agree on the terms of a commission, which is usually 50% (Benhamou 2011, 44; AGAC 2016; Rivest 1992).Footnote 4 Since galleries rarely receive grants (except for certain projects), they rely on this commission to keep their business running and to cover all commercialization costs (including managing the gallery, transporting artwork, marketing and sometimes framing, carried out in whole or in part with the artist). As a result, AGAC (2016) notes that about 35% of galleries were in the red in 2015, an alarming figure that brings into question the viability of these companies. These findings were echoed by Harvard economist and Professor Magnus Resch, who conducted a study which showed that 60% of art galleries in the United States, France and Germany (Resch 2016, 26) had negative or marginal profits of 10% or less.

However, larger businesses, in addition to having elaborate organizational structures and more employees (Routhier 2006; Resch 2016) facilitating daily operations, are putting a fair bit of emphasis on the secondary market. According to Routhier (2006), "reselling is rare among small dealers and is largely exclusive to dealers with average-to-high revenues (Routhier 2006, 10)." Furthermore, AGAC (2016) figures show that contemporary art galleries that sell artwork to secondary markets generally get a substantial share of their revenues from those sales. With so many dealers and galleries seemingly dependent on reselling artwork to survive, maybe these businesses are just not very profitable.

Nevertheless, new business models are starting to emerge that place greater emphasis on entrepreneurship than on art world conventions. As demonstrated by Resch (2016), galleries using these models are generally profitable when managed according to business principles, but do not always benefit from the legitimation of the art world, which is problematic and detrimental for artists. Unfortunately, the literature on these innovations is limited at the moment, so any further analysis will have to wait.

It should also be noted that galleries and dealers involved in the First Nations art trade use a different and, sadly, poorly documented model, limiting the information we can provide in this report. However, we do know that art produced by a living artist must first be traded through a Co-op.

1.1.3 Auction houses

Through their transparency and expert-led research, auction houses provide additional services by revealing appraisals and purchase prices and advancing our knowledge of artwork, resulting in an increasingly informed public (Pownall 2017, 44). New collectors are increasingly better informed, strengthening the private sales sector (Pownall 2017, 46). Now more than ever, auction houses and galleries have mutually beneficial relationships.

Auction houses have traditionally been associated with public sales of secondary market art. However, they are increasingly selling primary market works, in particular since British artist Damien Hirst set the precedent by auctioning his art at Sotheby's in 2008. Closer to home, street art is also sold at some Montreal auction houses. Clearly, strictly categorizing the business models of art market stakeholders based on a primary/secondary market split has become very misleading.

While auction houses have been used as economic health indicators for the art market, the literature cautions against reading too much into public sales. Record sales typically happen when outstanding works are put up for auction (leading to some occasionally ridiculous sales figures) or when extensive media coverage provides exceptional visibility and publicity. For example, the Canadian art market posted some impressive numbers in 2016, but that was mainly due to a Lawren Harris exhibition curated by actor Steve Martin—an event that featured at least one record-setting sale. This kind of success does not necessarily carry over to the next year, as David Heffel pointed out in an interview with the Financial Post: "In fact, national art markets are often subject to the persuasions and tastes that align with what is most coveted at the highest spending brackets (Craig 2016)." Moreover, Heffel Fine Art is particularly interesting, not only because the company is one of the country's leading auction institutions, but also because of how its business model has shifted toward private and online sales in recent years—a prime example of the phenomenon observed by Pownall. This trend is detailed in section 1.2.2.

With respect to Inuit art, Big River Analytics illustrates the full impact of art auction sales by factoring in all elements indirectly associated with them (transportation, photography, maintenance, catalogue production, etc.): "The casual reselling of Inuit arts and crafts does not represent significant new economic activity. However, the large-scale auctioning of many pieces conducted by auction houses does generate an economic impact through the work of curating, photography, design, the production of catalogues, restoration, the building of bases, insurance, marketing and the storing of artistic pieces (Big River Analytics 2017)." Two auction houses dominate the secondary sales of Inuit art in Canada: Walker's Fine Art and Estate Auctions, and Waddington's Auctioneers and Appraisers.

1.1.4 Events such as art fairs

Big events like fairs are becoming a critical platform for the art trade. They allow various stakeholders (galleries, collectors, institutions, commissioners) to help legitimate cultural products (works and artists) that can integrate the sphere of contemporary art, thereby giving these products symbolic value (Baia Curioni 2014). Economic historian Baia Curioni rightly states that:

At any rate, these supply networks define what art is, contribute to producing it, and are an intimate part of its essence. These are not distribution chains that can be disintermediated (for example, by the Internet) without serious consequences. These are mediation chains that transform the meaning of what they mediate… their action is still a necessity, at least in the contemporary system. (Baia Curioni 2014, 38)

At most large fairs, only dealers and galleries are allowed to have exhibits, while some smaller local events will also assign booths to artist-entrepreneurs. Canadian fairs such as the Toronto International Art Fair and Quebec's Foire Papier are key events directly generating millions in benefits and cultivating new audiences at the local level. Conversely, an ever-increasing number of Canadian dealers are participating in international fairs such as NADA (Miami, New York), Los Angeles Contemporary, Material or Zona Mexico, Taxi (Brussels), and Volta (Basel, New York), to name but a few. While artists represented at these high-profile international events can get a massive boost in recognition, it comes at high cost for dealers.

1.2 Supply chain innovation

1.2.1 Private and public sales

The "TEFAF Art Market Report 2017" reveals an interesting supply chain phenomenon. Transactions have recently been shifting from auction houses (public sales) to galleries and other private actors (Pownall 2016). This market trend is one of the report's main themes and makes it even more difficult to get data on the size of the art market because the private sector is more opaque.

As the researchers have highlighted throughout the TEFAF report, buyers want opaque transactions. They are concerned about the rather uncertain global socio-economic context (Brexit, American politics, etc.) and above all, seek anonymity. After all, in public sales, buyers and purchase prices are typically disclosed to the general public, often as part of a big media frenzy.

So private sales are no longer only carried out between private individuals (over-the-counter transactions) or at galleries, but also at auction houses. Traditionally interested in public sales only, auction houses have forced their way into this market segment by developing new business models to meet demand (McAndrew 2017 and 2016; Belting 2013; Pownall 2016). This trend can be observed at some Canadian auction houses, such as Heffel Fine Art, which is very transparent about the diversification of its activities, providing all the details on their website.

1.2.2 Digital technology

Regarding the development of digital platforms, a priority highlighted in an increasing number of cultural policies is starting to take hold: more and more galleries and dealers are selling art on online sales platforms (Pownall 2017, 13, 34–35; ArtTactic 2017; Poper 2017). This is a step forward considering that most of them were resisting the shift to online markets. That said, these online sales platforms will never be able to completely replace physical transactions in the traditional art world. Online platforms are mainly used by artists, galleries and institutions for promotional purposes. Digital technology is above all a vital mediation tool—the public's window into the art world.

As briefly mentioned in Section 1.1.1 on artist entrepreneurs, artists in the Far North are increasingly relying on online sales platforms. According to a Big River Analytics survey (2016), "IAB (Iqaluit Auction Bids) and local buy/sell Facebook pages have created a direct-to-consumer (online) distribution channel at a scale that is new in the Inuit arts economy. Because of the seasonality of sales (higher in winter and lower in summer), this study was unable to measure the impact of Facebook online sales directly; however, statements by participants of the information sessions held across Inuit Nunangat indicate the rise of online sales is driving the increased importance of the direct-to-consumer distribution channel."

Part 2 – The visual arts market

2.1 Overall value of the Canadian art market

The most up-to-date report attempting to quantify Canada's visual arts market is the TEFAF Art Market Report (Pownall 2017). According to the data collected and analyzed, 2016 saw the resurgence of the visual arts economy after a few down years internationally. The Canadian auction market (public sales) was valued at US$586 million in 2016, a 42% increase over 2015 (Pownall 2017, 177). Ontario had the biggest market, followed by British Columbia and Quebec (Pownall 2017, 179), with key hubs located near the U.S. border (Pownall 2017, 178). By extrapolating the data on hand, it was estimated that dealers and galleries had generated US$1.3 billion in 2015. Dealers surveyedFootnote 5 expected their turnover to double in 2016, and Maastricht analysts extrapolated a 20% growth for 2017.

Deloitte (Luxembourg) also released an international report that very briefly addressed the Canadian market, but the methodology they used to evaluate it is unclear. It should be noted, however, that they valued the Canadian market at US$1.3 billion (Deloitte 2017, 20) in 2016, the same comparative year as Pownall (2017). Nevertheless, they highlighted the growth of the Canadian market, in particular the four main hubs of Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and Calgary.

The Contemporary Art Galleries Association's report (AGAC 2016) has a fairly small sample size (only 15 Quebec galleries), but that still represents more than 60% of the organization's Quebec members. Overall, these 15 AGAC-member galleries in Quebec are said to have contributed at least $5.5 million to the art market in 2015, for a total of nearly 1,500 works sold (AGAC 2016, Addendum 1), mainly to Quebec customers. Primary sales of contemporary works accounted for $3.5 million.

According to a report on art dealer sales by the Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec (Routhier 2006Footnote 6), there were approximately 273 original art dealers in Quebec in 2001–2002. They made an estimated $65.5 million in sales that year, including exports (the study does not distinguish between sales to Quebecers, Canadians and international buyers). Quebec art accounted for 65% of all sales by Quebec dealers, with art from the rest of Canada accounting for 17%. The ratios were largely the same for dealers representing artists in museum collections and those who were not. For the sake of clarity and representativeness, dealers were segmented based on the reputation of the artists they represented. While only 25% of dealers represented museum artists, they generated 44% of sales in Quebec (Routhier 2006, 10). Dealers that did not represent museum artists had to rely on other activities to supplement their income. The majority of sales came from the primary market (66%).

2.2 Methodological limitations of these surveys on the visual arts economy

Reported figures for visual arts sales in Canada vary widely from source to source.

One major factor explaining this discrepancy is differences in methodology (AGAC 2016; Pownall 2017; Routhier 2006, 2013; TCI 1999). Even in the study of Statistics Canada and CSA data, the classification of cultural businesses involved in the visual arts trade is inconsistent, which can introduce some bias when reconciling data. Furthermore, some calculations include unique works of craftsmanship (TCI 1999; Routhier 2006) while others do not (AGAC 2016; Pownall 2016; SSHRC 2018). Consequently, it can be difficult to ascertain what is meant by "original works."

The term "dealer" is also inconsistently defined from one study to another. Some include all retail businesses trading original works, while others include big box retail stores (TCI 1999, when using data from Statistics Canada). Then there are those that limit the term to private galleries that are members of a professional organization (AGAC 2016) or to art galleries and antique dealers having participated in one of the 50 international fairs (access to which is fairly limited) and to auction houses as in Pownall (2017). As a result, total sales figures are generally extrapolated and difficult to compare due to a lack of research history; each group mentioned above conducted only one study of the Canadian market and used their own methodology, thereby making any comparison unreliable.

2.3 Specificities of the Indigenous and Inuit art markets

It is important to point out that the art market studies cited above probably did not include Inuit and Indigenous artists given their poor representation in galleries, nor direct sales by artists regardless of cultural origin. In recent years, studies specific to Inuit artists (Nordicity, Big River Analytics) have shown that their distribution network has some unique features not found among Indigenous communities, which use a fairly standard distribution network (Uzel 2017; Maranda).

The Inuit art market

Big River Analytics' study (2017) indicates that the main distribution channels are direct sales to consumers, retailers and wholesalers. The importance of distribution channels generally varies from region to region.

Direct-to-consumer sales, mainly online, are growing steadily in all areas of the Far North. The growth of this distribution channel can be attributed to lower retail and wholesale sales. 67% of the market's direct impact comes from direct-to-consumer sales—that is $22.1 million net of expenses (Big River Analytics). Online sales networks, primarily local Facebook buy/sell groups and the 26,300-member Iqaluit Auction Bids, have increased the importance of direct-to-consumer sales for artists (Big River Analytics 2017).

Nordicity's (2010) study shows that the economic impact of art production and distribution generated $27 million in direct payments to artists in 2010, leading to over $50 million in sales to consumers, including $30 million in sales through distributors across the rest of Canada and around the world. 10% of Nunavut residents earned income from selling art. Opportunities are as diverse as Nunavut's art distribution networks, which range from an artist-created and -operated "wholesale" distribution chain and co-ops (e.g., at Cape Dorset) to third party retailers and direct-to-consumer distribution via a cottage industry (Nordicity 2010, 8). Wholesalers account for less than 35% of artists' sales ($9.6 million), but over 60% of public sales, including about $16 million to retailers (Nordicity 2010, 6, 9–10). Nunavut's largest export market is the rest of Canada, at about $20 million, followed by the United States at $7.5 million and the rest of the world at $4.5 million.

In a more recent study, Big River Analytics (2016) shows that in 2015, Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts for income earned over $33 million net of all costs,Footnote 7 and the inputs they purchased and money they spent generated an additional $12.5 million in spinoffs (Big River Analytics 2016), showing an increase from 2010 to 2016. In addition, Inuit artists producing visual arts and crafts for consumption, through their purchase of materials and other inputs, generated $17 million in economic activity (Big River Analytics 2016). However, these figures must be put into perspective because they cannot be directly compared to estimates from other studies on the Nunavut arts and crafts industry, as no other studies have addressed the indirect impacts of the production of arts and crafts for consumption.

2.4 Consumers of visual arts products

Consumers are the last and most important link in the supply chain. After all, artists do not live off the spirit of the times or charity, and many have to sell their work to maximize their income. That is why it is so hard to get clear data on the economic impact of the visual arts market: the art market is too opaque. Data on art sales and art customers is also hard to find.

Quebec appears to be the main source of data on the growth of visual arts consumption. Purchase data are available, in particular for corporate collections, as are some household spending data, which are also available for the rest of Canada.

The Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communications' quinquennial survey of cultural practices reveals that 7.4% of Quebecers acquired a work of art in 2004 and 11.6% in 2009 (Audet et al. 2009). In 2014, 26% of Quebecers purchased a work of art (and 10% purchased a handicraft product) (MCC 2016, 49). The average purchase amount for artworks and handicrafts was $502 (MCC 2016, 49). Conversely, though these data should be taken with a grain of salt given the methodological framework, the "Survey of Canadian Household Spending from 2012 to 2016" shows that Canadians are spending less and less per work of art (including antiques and decorative items): $100 in 2012, $82 in 2013, $87 in 2014, $75 in 2015 and $78 in 2016 (Statistics Canada 2017).Footnote 8

Corporate collections

The Quebec Observatoire (OCCQ) used to conduct a biannual study assessing visual arts consumption by institutions, corporate collectors (including Crown Corporations) and municipalities in Quebec. The study included purchases made directly from artists (including 1% works). The most recent edition shows that 3/4 of works acquired in 2013–2014 were from artists outside Quebec (23% from Quebec) and that only 30% of total sales in 2013–2014 were from Quebec suppliers (galleries, dealers, consultants) (Routhier 2015). This downward trend continues. For example, in 2010–2011, 73% of purchases were made in Quebec (Routhier 2013b), while in 2008–2009 it was 92% (Routhier 2011).

Part 3 – Socio-economic conditions of cultural workers

There have been numerous studies on the socio-economic conditions of cultural workers, but only a few detailing the circumstances of visual artists and other visual arts workers. While recent surveys have covered the conditions of visual artists relatively well, we still have little information on cultural workers in the visual arts sector, including workers in organizational administration or in the art distribution or legitimation network. This part of the report is divided into two sections, one on non-artistic cultural workers and the other on professional artists, in order to shed light on their respective socio-economic conditions.

There seems to have been significant changes in methodology from the "2006 Census" to the "2011 National Household Survey". As a result, data from some reports cannot be compared with previous ones (in particular Hill 2014). The Canadian "Culture Satellite Account" (CSA) can be an interesting source of raw data if carefully interpreted, but the system it uses to estimate the number of cultural workers is different from those used in many other reports. Hill Strategies, for example, bases its survey on occupations, while CSA report estimates are based on cultural industries and products. In addition to its different methodology, CSC estimates differ in terms of reference year and data sources (Hill 2014).

Nevertheless, the latest literature has identified some key indicators regarding the issues affecting cultural workers. To be specific, these workers have low income, often do not have regular employment, work fewer and fewer paid hours per week and typically have temporary jobs (they are almost three times more likely to have more than one job than in 1990), according to a brief by Coalition La Culture, le Cœur du Québec (Azoulay and Paradis 2018, 10).

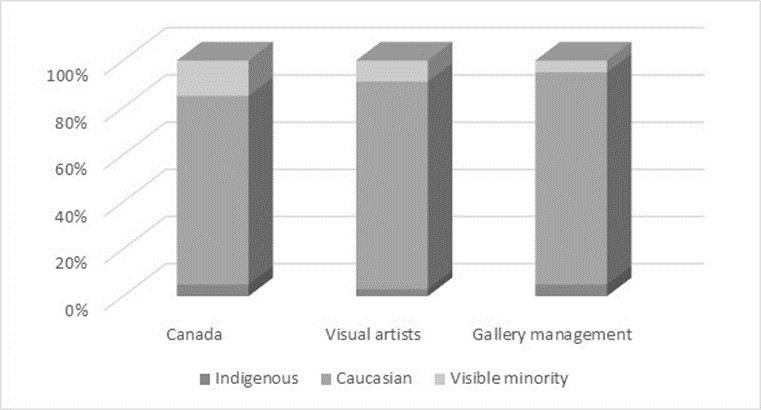

In his study on Indigenous peoples and cultural minorities in Montreal, Professor Jean-Philippe Uzel points out that "arts organizations run by Indigenous people are still the least well-endowed and the least well-supported in the Canadian art world as a whole (Uzel 2017, 36)." In a Canadian Art article, Maranda (2017) also highlights the disparity among artists on display at public institutions and among employees working at these institutions (in connection with the programming). Figure 3 illustrates this disparity.

-

Figure 3: Public museum representation by culture (Maranda 2017) – text version

This bar graph shows the representation, by percentage, of ethno-cultural groups in public museums for three groups: Canada, visual artists and gallery management.

In Canada,

- Indigenous: approximately 0.5%

- Caucasian: approximately 75%

- Visible minority: approximately 24.5%

Visual artists

- Indigenous: approximately 0.2%

- Caucasian: approximately 78%

- Visible minority: approximately 21.8%

Gallery artists

- Indigenous: approximately 0.5%

- Caucasian: approximately 81%

- Visible minority: approximately 18%

While Canada's population has become more and more diverse over the past 20 years, minorities are poorly represented in the visual arts, with proportionately fewer artists, sales and exhibitions. Maranda's conclusion sums it up nicely: "Key Finding: Gallery management is whiter than Canadian artists in particular, and the Canadian public in general [ ...]. The quick conclusion: as a sector, we aren't doing all that well in reflecting the population at large, on either ethnic or gender lines" (Maranda 2017).

3.1 Socio-economic conditions of visual artists

Generally speaking, artists certainly seem to be passionate about their work: while their income is below the Canadian average and they are generally better educated than most Canadians, only 38% of them have considered changing careers (27% for financial reasons); 91.8% of them have positive outlooks, saying that they want to "retire as late as possible" (Routhier 2013b, 82–83). It should be noted that Caucasians are overrepresented among visual artists in all studies (agYU Out There 2014a; Maranda 2014).

Artists are generally well educated. According to Statistics Canada's "2011 National Household Survey" (NHS), 77% of Canadian artists aged 25 and over have a postsecondary degree (Hill 2015, 2010; Uzel 2016, 26–27).

Income

Studies have shown that the average earnings of Canadian visual artists have not gone up much. In 2010, they had an average of $17,176 in earnings (median of $10,358) and $24,672 in income (Hill 2014).Footnote 9 These figures are corroborated by Routhier, who found that in 2010, 57% of Quebec artists had earned less than $29,999, while the average working Quebecer (according to Statistics Canada, which the study used as reference) had a personal income of $35,400 (Routhier 2013b, 8).

Most artists have to engage in other professional activities to secure a decent income: "It would seem that teaching the visual arts at the college or university level is the best financial option; 15% of artists do this and their average personal income is $54,200. Visual arts-related management, organization and facilitation activities are also options, with 16% of artists earning income from them in 2010. (Routhier 2013b, 35)."

Creative income was the main source of income for only 20% of artists. In fact, "the average income from visual arts creation before deducting production expenses is $10,600, but the median income is only $3,300 (Routhier 2013b, 9, 23–24)."Footnote 10

Artists' average earnings are low in all major Canadian population centres, and there are significant gaps between artists and workers in other industries (Hill 2010, 6). "The earnings gap is 36% or 37% in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver but is more than 50 % in Calgary and Ottawa (Hill 2010, 6)."

Median creative income also varies according to type of art. Artists who focus on drawing and printmaking have a lower median creative income ($1,500) than artists who focus on sculpting ($5,000). The Observatoire (OCCQ) study also shows that median creative income tends to go up the more working time artists devote to the visual arts (Routhier 2013b, 38). Creative income includes not only creation, but also royalties, art sales and rentals, etc. The following definition, provided in a report along with two graphs illustrating average income distributions, is particularly enlightening (Routhier 2013b, 40–41). "Artistic work in the visual arts essentially involves designing and producing artworks (sculptures, prints, paintings, installations, photographic works, textile works, etc.) and then ensuring their dissemination. This work generates various types of creative income." In the visual arts, sales are the main source of revenue.

Artist profiles

As a result of its study, the Onservatoire (OCCQ) was able to identify six major profiles for visual artists in Quebec based on characteristics such as income, source of income, amount of time spent on artistic work, education and gender: casual artists (about 21% or 760 people), versatile artists (15% or 550 people), struggling artists (19% or 680 people), prolific artists (28% or 1,020 people), senior artists (12% or 440 people) and master artists (5% or 180 people) (Routhier 2013, 11). Pan-Canadian studies show that this typology is fairly representative of artists across the country.

Researchers described the six artist profiles as follows (Routhier 2013b, 17–22):

- Casual artists (21% of the pool of artists): Spend little working time on their artistic career. Personal income is typically low (average net creative income of $2,310; their expenses exceed this amount). High proportion of women (70%) and young adults (20% under 35). Few CALQ or CCA grant recipients. Two-thirds have income from activities outside the field of visual arts (Routhier 2013b, 18).

- Versatile artists (15%): Spend most of their time on non-creative work. Above average earnings for artists. Typical artist demographics. Two-thirds have a university degree in visual arts (bachelor's, master's or doctorate) and 40% have a second degree in another field. Average net income of $43,600 (including $1,560 in creative income). Few CALQ or CCA grant recipients (Routhier 2013b, 19).

- Struggling artists (19%): Many young adults (20% under 35) and as many men as women. Average personal income under $10,000 (including $1,670 in creative income). Spend on average 2/3 of working time on artistic work (median production: 9 works), but creative expenses exceed creative income (Routhier 2013b, 19).

- Prolific artists (28%): Full-time artists who live off their art. Average income is $10,900 (almost all creative income). As many men as women. Large proportion with no degree in visual arts, but many grant recipients. Half are represented by a gallery or an agent, 10% produced 1% works and more than half sold or exhibited works outside Quebec in 2010 (Routhier 2013b, 20).

- Senior artists (12%): Two-thirds over 55 and as many men as women. 40% have a university degree in a field other than visual arts and a third teach visual arts. Above average personal earnings for artists ($36,700), but little creative income ($2,810). Half are represented by a gallery and the same proportion sold or exhibited works outside Quebec in 2010 (Routhier 2013b, 21).

- Master artists (5%): Mature artists—mostly men living in large cities (60%). Highly educated with well above average incomes for artists ($86,400). Most are grant recipients. Same ratios as prolific artists in terms of representation, sales outside Quebec and 1% works produced. 70% teach visual arts at a college or university (Routhier 2013b, 21).

Age

According to data collected by Michael Maranda's team (agYU Out There 2014a), the average age of artists remained stable at around 43 from 2007 to 2012, but the average age of minority artists decreased from 39 to 37. This either suggests that the number of young artists is growing, which would be representative of the overall labour force, or that visible minority artists are rapidly leaving the profession. Sales, studio time, professional expenses, and gallery representation increase with age, with grants, royalties and creative income peaking around 35–45 (Maranda 2009, 41–49).

Education

Nearly 40% of artists have an undergraduate degree, compared to 16% of the labour force according to Statistics Canada (2006 data). According to Maranda (2009), 44.9% of artists have a graduate degree (compared to 6.9% of the labour force), typically a master's degree, although 4.6% have a doctorate and 5% are doctoral students (Maranda 2009, 14).

Mobility

Overall, 80% of the world's most renowned artists live and work in the countries where they were born, contrary to the assumption that popular artists should be more likely to travel and leave their countries of origin (Quemin 2015, 836). The visual arts scene has really opened up to the outside world (Canadian and international) in the last ten years.

As the research demonstrates, however, this openness to the world does not necessarily entail that local artists—Indigenous, minority or otherwise—are any more likely to have their work exhibited in foreign institutions or to sell more in other provinces (Uzel 2017, 28–29; Routhier 2013b). The data actually shows that corporate and institutional acquisitions are in constant decline (Routhier 2014, 2011, 2009; AGAC 2016). As Uzel explains, the community has opened up to the international scene in the sense that museums and events are now giving foreign artists more visibility (Uzel 2017, 29), apparently for the benefit of Canadian audiences. While this limits the visibility of Canadian visual artists, AGAC stresses that it exposes the public to internationally recognized practices in the art world, which "increases demand for the latest, most rigorous" and high-level practices (AGAC 2016, 15).

Nevertheless, more and more Canadian galleries are participating in international fairs in the United States, Mexico and Europe, and Canadian artists are being put on display in international contexts, which can lead to collaborations outside Canada. The Uzel-led study highlights that while this international shift has allowed many artists of various nationalities to be exhibited in Quebec and the rest of Canada, but few Canadian minority artists are exhibited internationally. The same is true for Indigenous artists who have little presence on the Canadian scene (Uzel 2017, 31–32). There is a correlation between Indigenous and minority artists with an international presence, representation by recognized distributors (dealers and galleries) and level of education: the best educated artists get the most international exhibitions (Uzel 2017, 32).

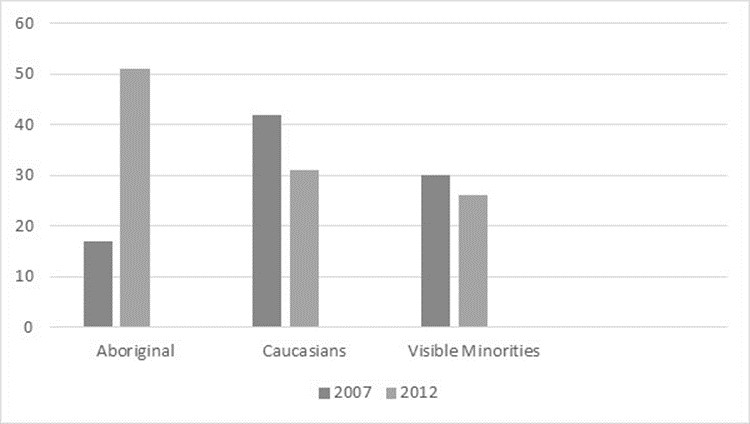

Gallery representation

Caucasian artists were 10% less represented in galleries in 2012 than in 2007, and their sales income has dropped by 35% as a result (agYU Out There 2014a). Their median income, however, has gone up about 10%, from $20,200 to $22,400.

-

Figure 4: Gallery representation by culture (Maranda 2009) – text version

This bar graph shows the percentage of Aboriginal, Caucasian and visual minorities groups represented in galleries in 2007 and 2012.

In 2007,

- Aboriginals: approximately 16%

- Caucasians: approximately 41%

- Visible minorities: approximately 30%

In 2012,

- Aboriginal: approximately 51%

- Caucasians: approximately 43%

- Visible minorities: approximately 25%

Financial support of the practice

Grants are the main source of financial support for artists, but only a fraction of them receive any (18%, see Routhier 2013b, 44). "While men and women are about as likely to receive grants (20% and 17% respectively), the median grant for female recipients ($4,900) is lower than that of male recipients ($10,000). In addition, artists are less and less likely to receive grants as they age (37% of grants are given to the youngest artists and 6% to the oldest) (Routhier 2013b, 44)."

Income security and retirement

"Visual artists have relatively poor access to social assistance and income security plans (Routhier 2013b, 51–52)." Self-employed workers are not covered by employee pension plans, so retirement planning is not as straightforward. However, quite a few artists have paid jobs outside the art world, suggesting that they may benefit from less risky social assistance and retirement plans.

The Observatoire (OCCQ) study shows that only 32% of artists have made contributions to pension plans, though 59% of them have investments. While the study provides no information on retirement income, 92% of artists said they wanted to retire as late as possible. The OCCQ therefore assumes that the vast majority of artists will continue to work well after they turn 65 (Routhier 2013b, 52), which ties into the survey that found artists over 55 to be overrepresented.

3.2 Socio-economic conditions of artists from ethnocultural communities and specific groups

The literature on Canada's ethnocultural communities is quite limited (Nordicity 2010, 2016; Trépanier 2009; Misdrahi 2015; Big River Analytics 2017; Uzel 2017; Anamik 2015; Gauvin and Haentjens 2001). Some books have been published on gender divisions, but most of the information available on the working conditions of women in the visual arts is found in broader studies.

It should be noted that the only recent studies we could find on Indigenous people were from Quebec. However, some provinces like British Columbia and Manitoba have high concentrations of Indigenous artists and groups, suggesting that there may be issues specific to these areas. In that regard, the scope of this study is limited.

A recent study commissioned by the Conseil des arts de Montréal (Uzel 2017) on the professional issues and socio-economic conditions of Indigenous and visible minority artists in Montreal is particularly illuminating. One striking conclusion was that it can be quite difficult for these artists to integrate the cultural community and, especially, to have their work accepted on the same level as that of non-Indigenous and non-minority artists. Indigenous and minority artists often face the same problems. These include having difficulty achieving professional status, lacking visibility, not being fairly recognized (Uzel 2017, 9, 51) and feeling discouraged (Uzel 2017, 57–58). Conversely, they differ in other key aspects such as techniques and media, cultural heritage and the notion of "contemporary" (so often opposed to "traditional").

A survey of arts organizations revealed that some of the issues encountered by Indigenous and minority artists appear to be related not to a lack of integration programs, but rather to programmers, panelists and selection committees (often peers) having a poor understanding of their aesthetic codes (Uzel 2017, 40–42).

Indigenous, non-Caucasian, female and senior artists each face specific issues that will be detailed in the following sections. All aspects of artistic income are roughly the same for both Canadian-born and immigrant artists (Maranda 2009, 53). According to Maranda (2009), immigrants sell more works but also have higher non-artistic income, suggesting that artistic work is not their main source of income. However, arts-related earnings tend to be higher among native-born Canadians. In the end, median earnings are the same for both groups (though average earnings are higher for immigrant artists). Nevertheless, Uzel indicates that "the average annual earnings of Indigenous and minority artists are lower than those of other artists (Uzel 2017, 34)."

Since cultural heritage figures so prominently in the arts, especially among Indigenous and minority artists, "there is some consensus that certain forms of expression do not really fit within conventional categories of visual arts [...] and that conventional visual arts disciplines and mediums (paintings, sculptures, photographs, etc.) do not adequately reflect the reality of Indigenous art and that it is important to consider other forms of cultural expression (Uzel 2017, 48)." "Conversely, other artists and art presenters argue that Indigenous visions of art can be expressed through existing disciplines (theatre, poetry, visual arts), even if it means adapting and transforming them, as in the case of installation art, which is more prominent among Indigenous artists than non-Indigenous artists. This discussion is significant because it impacts the debate on whether the creations of Indigenous artists can truly be judged by their 'peers' (Uzel 2017, 49)." Only a third (1/3) of surveyed Montreal presenters (organizations, groups, artist centres) said that "there are procedures to ensure staff diversity within their organization (Uzel 2017, 42)."

3.2.1 Indigenous artists

Indigenous artists represent 4.6% of the Canadian population, but only 2.2% of visual artists. Visible minorities make up 19% of the Canadian population, but only 9% of visual artists, almost 45% of whom are Canadian-born, suggesting that the disparity in the representation of visible minorities is because so few immigrants are becoming artists, which may just be a generational problem (agYU Out There 2014a). Uzel (2017) points out that Indigenous artists are much more mobile than minority artists.

Income

The median income of Indigenous artists fell from 2007 ($18,600) to 2012 ($15,300), despite their average income improving substantially (agYU Out There 2014a).Footnote 11 This illustrates the income gap among Indigenous artists, which can be due to a range factors including a popular small artist group or an increase in earnings from sources outside the visual arts. The study shows a marked improvement in gallery representation (from 16% to 47% in 2012) and level of education, which may explain the rise in average income and may be indicative of a trend according to researchers.

Exhibition

As demonstrated by art sociology studies, in particular those carried out by Moulin, institutions are key players in the legitimation of art. Researchers have been studying the cause-and-effect relationships influencing the careers of Indigenous and minority artists and have determined that institutions play an important role (Uzel 2017, 24–26). By examining artist resumes, researchers have established a correlation between exhibition venues and professional recognition: "[there is a] correlation between the highly hierarchical categories of Montreal venues and the types of careers Montreal artists have—international, national or regional (Uzel 2017, 26).

An increasing number of institutions, exhibition centres and networks dedicated to the dissemination of Indigenous practices have adopted stricter collection and exhibition policies regarding the proportion of works by Indigenous artists (Uzel 2017, 36). While these organizations have clearly been making efforts to recognize Indigenous practices, parity has not yet been achieved. "Recognizing the place of Indigenous people in modern Canadian culture and society does not mean giving them a 'numerically equitable' presence. Above all, it means recognizing their place at the centre of Canadian culture (Uzel 2017, 39–40)."

3.2.2 Minority artists

As part of his research, Michael Maranda (2009) compared the incomes, working time and gallery representation of Caucasian, visible minority and Indigenous artists in Canada. The study reveals that in 2012, minority visual artists had higher average incomes than Caucasian visual artists, but their median incomes were 28% lower (agYU Out There 2014a; Uzel 2017). This may be explained by the fact that a greater proportion of visible minority artists had a second job.

According to Maranda (2009), immigrants with legal status in Canada tend to have more post-secondary education, so visible minorities have a few more years of education than other groups. Researchers have found that the more educated a person is, the more likely they are to be home owners and live in metropolitan areas. Women are generally more educated than men (Maranda 2009, 14).

Although minorities account for 33% of Montreal's population (Uzel 2017), minority artists account for no more than 12% or 13% of visual artists on display in Montreal's two major art exhibition networks." This figure cannot be corroborated for Canada as a whole.

3.2.3 Women artists

A large majority of visual artists are women (agYU Out There 2014b; Hill 2014; Routhier 2013). Women are more likely to be home owners and live in big cities. They are also typically more educated than men, which is true of the labour force in general. In the arts community, 96% of women have at least an undergraduate degree, compared to 88% of men (agYU Out There 2014b).

In Inuit communities, more women produce visual arts than men, but they earn half as much: "The large differences in male and female art incomes can be explained by examining the types of art that each gender engages in (Big River Analytics 2016)." In a nutshell, women tend to sew and men tend to carve, a traditionally more masculine discipline with a higher market value. The same financial gap can be seen among non-Inuit artists, but to a lesser extent.

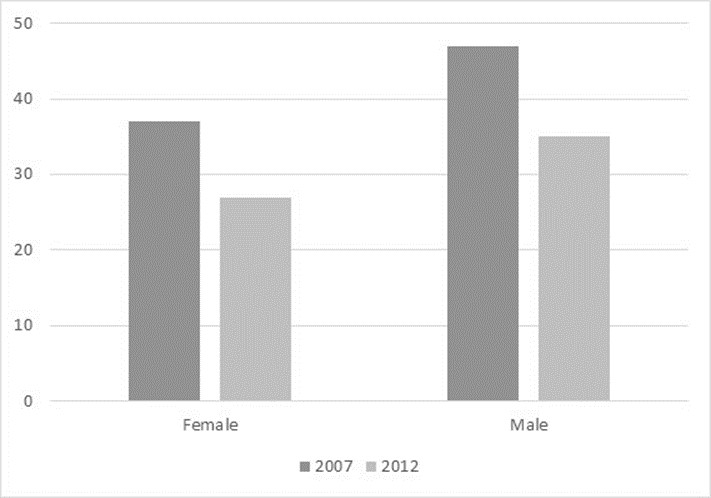

-

Figure 5: Gallery representation by gender (Maranda 2014) – text version

This bar graph shows the percentage of males and females represented in galleries in 2007 and 2012.

In 2007,

- Females: approximately 36%

- Males: approximately 46%

In 2012,

- Females: 28%

- Males: 36%

Maranda (2014) points out that, when taking into account all Canadian artists, gallery representation is lower among women (28%) than men (36%) (Fig. 3). The situation does not seem to have changed, as according to gallery owner Émilie Grandmont-Bérubé, we still have a long way to go: "[Among AGAC members,] only 4 out of 40 galleries have achieved parity, and 4 others have less than 16% women. The average is around 25–35%. And of the 4 gender-balanced galleries, 3 are run by women (Delgado 2018)." There is every reason to believe that this disparity among artists is just as significant within the broader segment of cultural workers and entrepreneurs, on which little to no research seems to have been conducted.

Female artists receive on average 30% of their income from sales and 50% from grants, whereas men are the exact opposite, with 50% from sales and 30% from grants. Women earn 2/3 the artistic income of men. As Michael Maranda highlights: "Turning to the Waging Culture data, for visual artists, the net practice average hourly income wage gap in 2007 was 27%. This gap increased by 2012, however, to a shocking 60%. That bears repeating: for every $1/hr a male artist earns, a female artist earned 40¢. About the only mitigating factor here is that the average hourly wage of artists is so miniscule to being with (agYU Out There 2014b)."

3.2.4 Senior artists