The Mobile Labs of the Canadian Conservation Institute

By Tyler C. Cantwell and Danika McDonald

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. 126575-0001

Figure 1. Some of the conservators who worked on the mobile laboratories in the early 1980s.

If you’ve ever taken a road trip across this vast country, you are aware of the awe-inspiring beauty and breathtaking magnitude of Canada. For a lucky group of Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) staff members in the early 1980s, an extended road trip was a normal part of the job. Conservators and interns spent weeks touring the country in one of five Chevrolet vans dubbed the “CCI mobile labs.”

The idea of the CCI mobile conservation laboratory came about in 1979, seven years after CCI was founded. Back in 1972, the government envisioned central headquarters for CCI in Ottawa that would work in tandem with five regional service centres. Unfortunately, this ambitious dream was never fully realized. By 1979, only the headquarters remained, and it had limited capacity to serve museums, archives and galleries beyond the borders of Quebec and the Atlantic provinces. So how would CCI meet its mandate of serving over 2500 heritage institutions in every region of Canada?

It was in response to this challenge that the mobile lab was born. If regional centres were not feasible, then CCI staff would hit the road to bring their expertise directly to clients.

Brian Arthur, CCI Director at the time, advocated for the idea of the mobile lab and became personally involved in its success. “For the first few trips, I went out with the senior conservator, which was fun, and we had wonderful press,” he reminisced in an episode of the podcast CCI and CHIN: In Our Words. “I made sure that the advisory council told all the television stations, all the newspapers, everything: ‘The feds are coming to town…and they are going to help us!’”

In the first year, the concept was developed and tested. The purpose of the mobile lab was to provide services to smaller community museums and to treat objects on-site if they required only minor treatment. This enabled the central lab in Ottawa to remain available for lengthy, extensive and specialized projects. The objectives of the mobile laboratory program were twofold:

- to provide conservation advice and related information to museums, galleries and other cultural institutions on such things as handling, transportation, storage, display and care of objects; and

- to provide on-site conservation treatments.

“I’d seen some [mobile laboratories] in my travels around the world, so we bought these vans and Lynn [the former head of the Atlantic centre] designed them as a laboratory,” Arthur explained. “The idea was that the lab would go out via the advisory council… and they would tell us which little museums it would really help.”

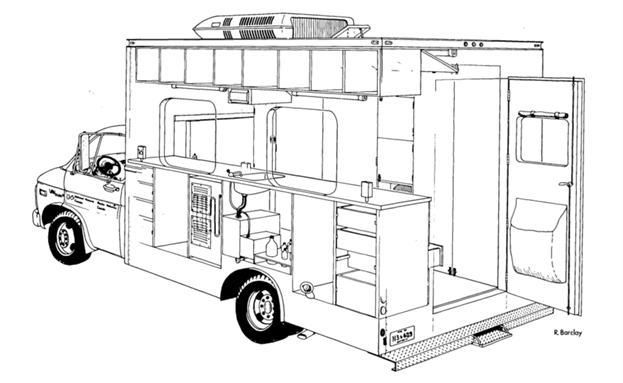

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute.

Figure 2. A schematic of the mobile conservation laboratory, featured in the article by McCawley and Stone (1983).

CCI faced a monumental task and rose to the occasion with creative problem solving in the form of a humble brown van. A small contingent of staff completed a pilot tour of 23 organizations over a 10-week period (National Museum of Canada et al. 1979). They rotated the equipment in the van to allow for diverse conservation specialties, and they were able to accomplish the same output as a more significant laboratory using the 10,000 lb. vehicle.

The success of this tour spawned a fleet of five Chevrolet vans that had stainless steel sinks, cupboard storage for the appropriate chemicals, windows fitted with curtains to darken the lab as needed, heating and air conditioning as well as specialty materials (McCawley and Stone 1983). Staff members took each of the vans out on three mobile conservation tours between 1980 and 1982.

Due to the compact nature of the vans, staffing was minimal. One conservator travelled in a van on a three-week shift with one intern, who worked on a five-week rotation. Staff had to rely on their experience and knowledge to treat a wide variety of objects and materials. In one tour, they treated objects ranging from textiles to pottery to chainsaws. It is admirable that a small team of two, in an unassuming van, set out to preserve a vast wealth of diverse heritage.

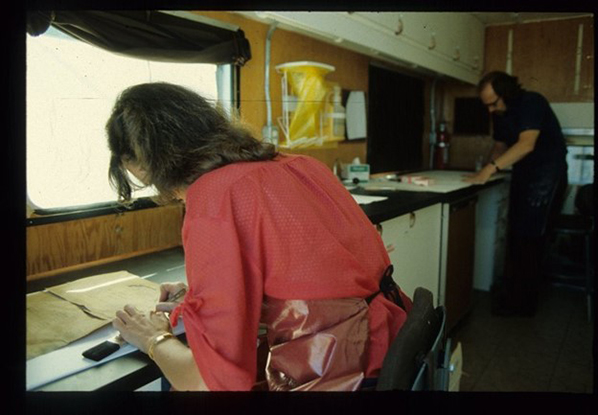

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. 126575-0002

Figure 3. Interior of the mobile laboratory.

The staggered staffing rotation had the added benefit of providing one-on-one training for the interns on top of hands-on instruction for museum staff. Furthermore, the conservators themselves found the mobile labs to be beneficial to the culture of conservation.

Ela Keyserlingk, a retired textile conservator who worked at CCI between 1976 and 1997, remembered the mobile labs fondly in her episode of the CCI and CHIN: In Our Words podcast: “The mobile lab was a wonderful thing. It was very good for us as conservators because it was a real reality check. I mean, we were sitting here a little bit in an ivory tower…”

All road trips must end, and the same was true for the CCI mobile labs. The last tour took place in 1983, and the program ended in 1987. During their travels, the conservators and interns served at least 544 institutions and treated some 4000 objects (Stone 1984).

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. 126575-0003

Figure 4. Tom Stone at work in the mobile laboratory.

Facing a monumental task, a tight budget and a vast landscape, the work of the CCI conservators cannot be understated. It is important to recall that what is preserved through conservation is not simply an object, but the past itself. The information these objects provide tells us about the culture, values and history of those who made them. It tells us about where we come from, who we are and where we might be going next. Furthermore, new analytical technology is always being introduced and new information is continually being recovered from even the oldest heritage objects. Thus, it is not just important to preserve these objects for us but for future generations as well.

What’s more, the mobile labs provided cherished memories for those involved. Keyserlingk remembered, “I always was sent up to the Yukon… and I absolutely fell in love with the Yukon.”

Happy memories of travelling across Canada and pride in the work CCI did to provide conservation services across this great land are apparent in all that is said and written about that time in CCI’s history. It may seem romantic to look back at the mobile labs and imagine road-tripping across Canada in the early 1980s to provide conservation services, but to many small institutions, the tours were admirable and, often, essential.

For more information, consult the video “The Mobile Labs of the Canadian Conservation Institute.”

Bibliography

Inch, J.E. “Canadian Conservation Institute: Serving Our Clients … Preserving Canada’s Heritage.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 9,3 (2013), pp. 283–298. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/155019061300900304

McCawley, J.C., and T.G. Stone. “A Mobile Conservation Laboratory Service.” Studies in Conservation 28,3 (August 1983), pp. 97–106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/1506111

National Museum of Canada and Canadian Conservation Institute. Evaluation of the Mobile Conservation Laboratory / Évaluation du laboratoire itinérant de restauration. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1979.

Stone, T.G. “A Mobile Conservation Laboratory Service.” AICCM Bulletin 10,2 (1984), pp. 49–56.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute, 2023

Cat. No.: CH57-4/68-2023E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-49170-7