Restorative Opportunities Victim-Offender Mediation Services Correctional Results Report 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024

On this page

Alternative format

List of acronyms

List of acronyms

- CJI

-

Community Justice Initiatives

- CSC

-

Correctional Service Canada

- FY

-

Fiscal year

- IPC

-

Infection prevention and control

- OMS

-

Offender Management System

- POs

-

Parole Officers

- RJ

-

Restorative justice

- RO

-

Restorative Opportunities

- VOM

-

Victim-offender mediation

Background

The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) began providing victim-offender mediation (VOM) in a limited capacity, with service delivery mainly in the Pacific region and on an adhoc basis in the Ontario region, beginning in fiscal year (FY) 1991 to 1992. With its long-held belief in the benefits of the restorative justice (RJ) approach and its values/principles, CSC continued to expand its RJ footprint by establishing the Restorative Justice Division in 1996. In 2004, it launched the Restorative Opportunities (RO) program nationally.

The RO program provides people harmed/victimized by a federal offence(s) the opportunity to communicate with the offender that caused the harm, using facilitated dialogue (also known as victim-offender mediation), to address the long-term impacts and needs created in the aftermath of crime. Participants have a say in how they would like to proceed, based on their individual needs, that are discussed with an experienced mediator/facilitator. Participation is voluntary throughout the process. RO strives to meet the specific, individualised needs of all participants, while exploring participants’ questions, expectations, hopes, and fears. It also strives to contribute to public safety, the prevention of future harm, the restoration of participants’ well-being, and the ability to affect forward movement in their lives.

VOM contributes to CSC’s mandate to safely reintegrate offenders into society by ensuring that offenders understand the human cost of their crime, are given the chance to address the harms with those most affected, to take meaningful accountability for the harms caused, and explore options to try to repair the harm caused, where possible. For victims, it provides the opportunity to explain the crime’s physical, emotional and financial impact on their lives, to be heard, to ask questions, and have some of their needs met through communication with those directly involved.

Methdology

This report has been published annually since 2010 to present the cumulative number of referrals over the years, as well as the cumulative results of participating in a face-to-face VOM meeting. The 2022 to 2023 Correctional Results Report was not produced due to challenges relating to the implementation of a new database. Data for fiscal year 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024 are included in this report.

This document provides information about the requests for VOM services; the services delivered through the RO program; and the correctional results of 317 offenders who completed a face-to-face VOM meeting from 1992 to March 31, 2024. An analysis of the data provided, in correlation with data extracted from CSC’s Offender Management System (OMS), was used to verify offender status and offence history post-VOM (face-to-face processes exclusively).

For additional background information, see Annex A: Research and evaluation.

Referral statistics

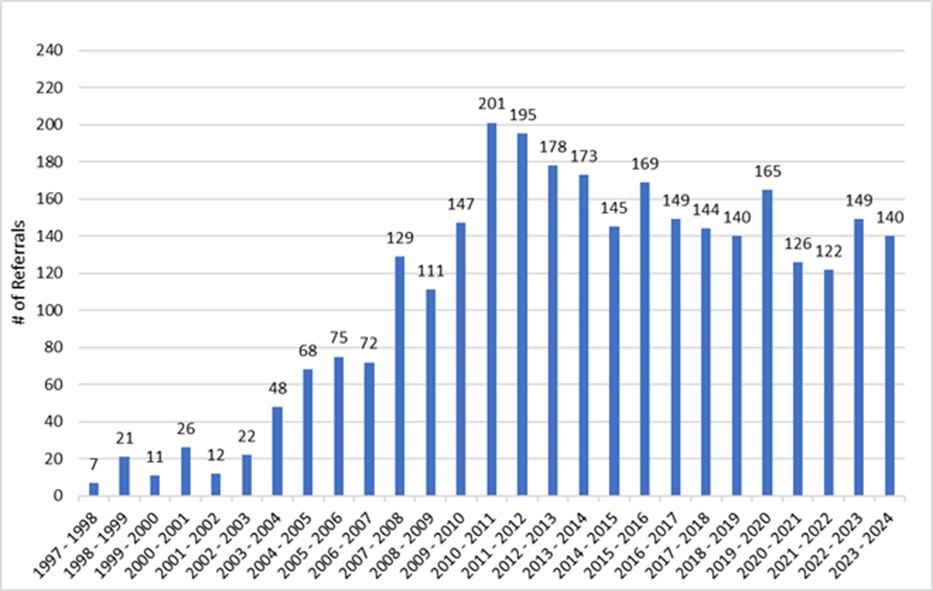

Annual referral trends 1998 to 2024

This graph includes referrals received since January 1998. The RO program started receiving its first referrals from victims, victim representatives, and offenders in 1992. However, from 1992 to 1997, data collection for incoming referrals was not standardized and requests for VOM services were not recorded before 1998.

Text version

Vertical bar chart showing the number of annual referrals received for the Restorative Opportunities program, by fiscal year (FY). The first reporting period was shorter because data collection began in January 1998.

- FY 1997 to1998: 7 referrals

- FY 1998 to 1999: 21 referrals

- FY 1999 to 2000: 11 referrals

- FY 2000 to 2001: 26 referrals

- FY 2001 to 2002: 12 referrals

- FY 2002 to 2003: 22 referrals

- FY 2003 to 2004: 48 referrals

- FY 2004 to 2005: 68 referrals

- FY 2005 to 2006: 75 referrals

- FY 2006 to 2007: 72 referrals

- FY 2007 to 2008: 129 referrals

- FY 2008 to 2009: 111 referrals

- FY 2009 to 2010: 147 referrals

- FY 2010 to 2011: 201 referrals

- FY 2011 to 2012: 195 referrals

- FY 2012 to 2013: 178 referrals

- FY 2013 to 2014: 173 referrals

- FY 2014 to 2015: 145 referrals

- FY 2015 to 2016: 169 referrals

- FY 2016 to 2017: 149 referrals

- FY 2017 to 2018: 144 referrals

- FY 2018 to 2019: 140 referrals

- FY 2019 to 2020: 165 referrals

- FY 2020 to 2021: 126 referrals

- FY 2021 to 2022: 122 referrals

- FY 2022 to 2023: 149 referrals

- FY 2023 to 2024: 140 referrals

The average number of annual referrals over the last 5 years is 140. The total number of referrals received during the fiscal year (FY) 2010 to 2011 remains the largest number received since the beginning of the RO Program, likely due to the higher volume of outreach and presentations in 2007 to 2008 and 2010 to 2011. The increase in 2015 to 2016 may be due to communications about the coming into force of the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, which provides victims with a right to information about restorative justice programs.

In FY 2022 to 2023, there was a 22% increase of annual referrals compared to the previous FY, while victim referrals remained constant. The number of institutional referrals was impacted significantly by the infection prevention and control measures of the COVID-19 pandemic as the process in the correctional environment requires in-person interaction between staff (such as, the referral agent) and the offender. This increase could be due to the participants' increased need to pursue communication, following the pandemic. The 2022 to 2023 period also coincides with a reduction in infection prevention and control restrictions for COVID-19, thus facilitating in-person RO service delivery.

Although the number of annual referrals for FY 2023 to 2024 remained similar to the previous year, the number of victim-initiated referrals decreased by 26%, while the number of institution-initiated referrals increased by 9%. The number of victim referrals was at its lowest level (n=7) during the third quarter of FY 2023 to 2024 and institutional referrals reached its highest level during the fourth quarter. In the past 5 years (2019 to 2020 to 2023 to 2024) this situation has only occurred once, in the second quarter of fiscal 2020 to 2021.

Referral origin 1992 to 2024

|

Victim-initiated referrals |

1074 |

34% |

|

Institution-initiated referrals |

1914 |

60% |

|

Other / UnknownFootnote 1 |

187 |

6% |

|

Total |

3175 |

100% |

Victim-initiated referrals include referrals from victims registered to receive information from CSC, victim representatives, and non-registered victims. 60% of victim-initiated referrals are submitted through Victim Services Footnote 2 and 21% of requests for RO services are made directly by victims themselves.

Institution-initiated referrals consist of referrals from offenders who are currently serving a federal sentence in an institution or in the community and are supported by a referral agent (for example, Parole Officer, Chaplain/Spiritual Leader, Psychologist, et cetera). The majority of institutional referral agents are either Parole Officers (POs) (65%) or Chaplains/Spiritual Leaders (27%).

By raising awareness of RO services and referring offenders, referral agents play an important role in the program’s operation. In addition to referring offenders, POs provide support to RO staff and mediators when determining the suitability of the offender to participate and whether there are any concerns. In victim-initiated cases, POs provide valuable information into the offender's progress and level of motivation, as well as the likelihood that the offender will be open to communication with the victim(s).

The number of institution-initiated referrals exceeds the number of victim-initiated referrals, which is likely due to more exposure to information about the RO program in institutions through POs, Chaplains/Spiritual Leaders, and community-based restorative justice groups.

The RJ Division and CSC’s Victim Services continue to share information about the program through outreach activities in support of victims’ right to information about the services available to them. Information is also made available on the internet, through Canada.ca and the Victims Portal, in order to increase communication to victims and the services available to them. Despite ongoing efforts in this direction, the proportion of victim-initiated referrals tends to remain stable.

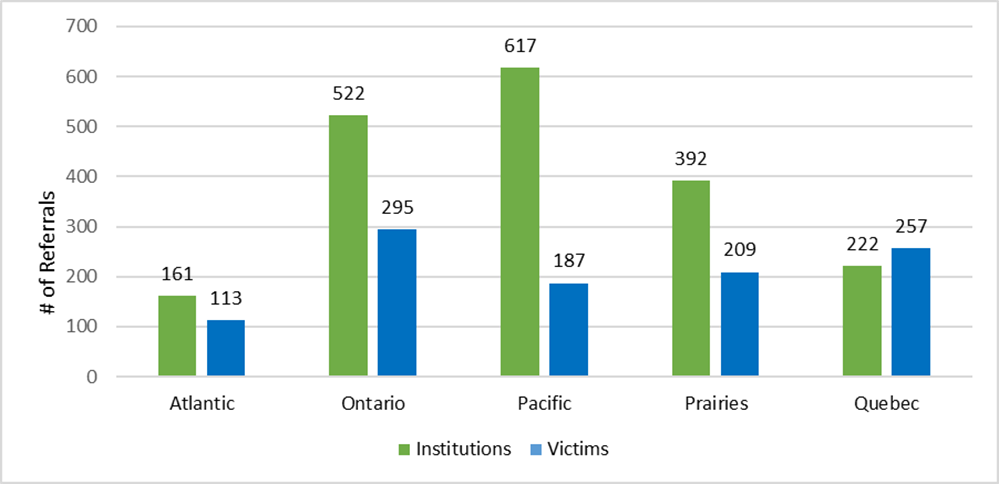

Referral origin by region 1992 to 2024

Text version

Vertical bar chart comparing the number of referrals received, from 1992 to 2024, and their origin (institution or victim) for each of the 5 regions of Canada.

- In the Atlantic region, 161 referrals were from institutions, while 113 were victim-initiated.

- In the Ontario region, 522 referrals were from institutions, while 295 were victim-initiated.

- In the Pacific region, 617 referrals were from institutions, while 187 were victim-initiated.

- In the Prairie Region, 392 referrals were from institutions, while 209 were victim-initiated.

- In the Quebec Region, 222 referrals were from institutions, while 257 were victim-initiated.

Since January 1998, the Quebec Region is the only region that has had and still maintains higher victim-initiated referrals versus institution-initiated referrals. This difference is likely due to the interwoven social services with the criminal justice system in Quebec compared to other provinces and territories, which increases and strengthens the Quebec’s Regional Victim Services Unit’s connections with other victim-serving organizations and social services in the province. The Pacific Region has the highest proportion of institution-initiated referrals since the services have been delivered in the region for longer than any other.

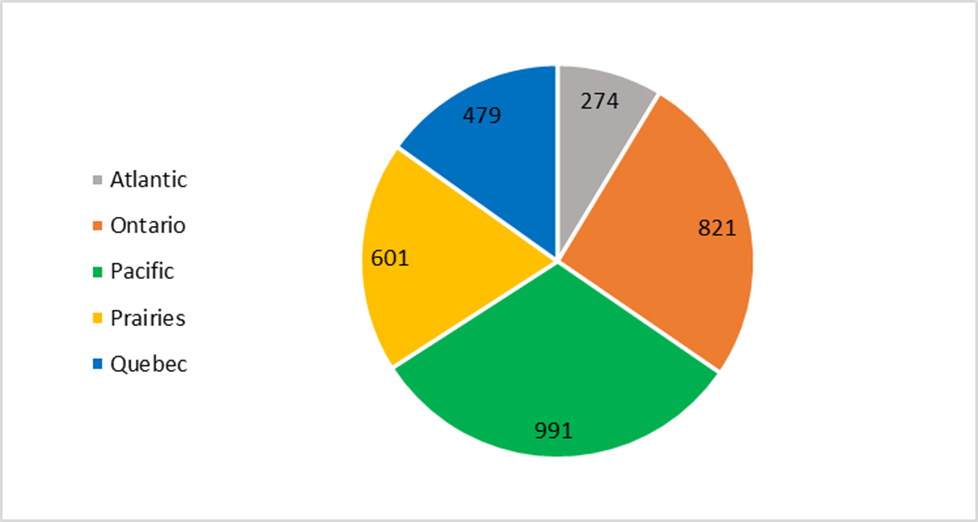

Regional referral snapshot

Text version

Pie chart divided into 5 sections. Graph is divided by region, based on total number of referrals received between 1992 and 2024.

- Ontario: 821 referrals

- Pacific: 991 referrals

- Prairies: 601 referrals

- Quebec: 479 referrals

- Atlantic: 274 referrals

The number of referrals is highest in Pacific Region due to the fact that the program was initially piloted there and has been offered longer in Pacific Region than any other region in Canada Footnote 3. While Ontario started providing services in the 1990’s, it was only on an ad hoc basis. The program was expanded nationally in 2004.

Victim-offender mediation services

RO is dedicated to facilitating safe and constructive communication without causing further harm. All requests for service are carefully assessed to determine the appropriateness of the intervention and the readiness of the participants to proceed with communication. In some cases, requests may not proceed if the other party is inaccessible, is not ready, chooses not to participate, or if motivations are deemed inappropriate for participation in the program. To this end, preparation is key for all primary participants, as well as support persons, accompanying victims and offenders. It can take many months or years for participants to be well prepared and ready to communicate safely. Delays may occur if further preparation is required. Due to the extent of preparation required and participants’ readiness to move forward, a smaller number of processes are delivered annually in comparison to the number of referrals to the program.

CSC offers various means of facilitated dialogue depending on the participants’ needs. While victim-offender face-to-face dialogues take a lot of time to prepare for, letter exchanges may be completed more quickly. While the majority of referrals request a face-to-face VOM, other facilitated dialogues can be used as an interim process, on the way towards a face-to-face meeting. Virtual service delivery options also allow participants to have multiple options to choose from when deciding which means of communication best fits their needs. All types of facilitated dialogues are reported in the tables below.

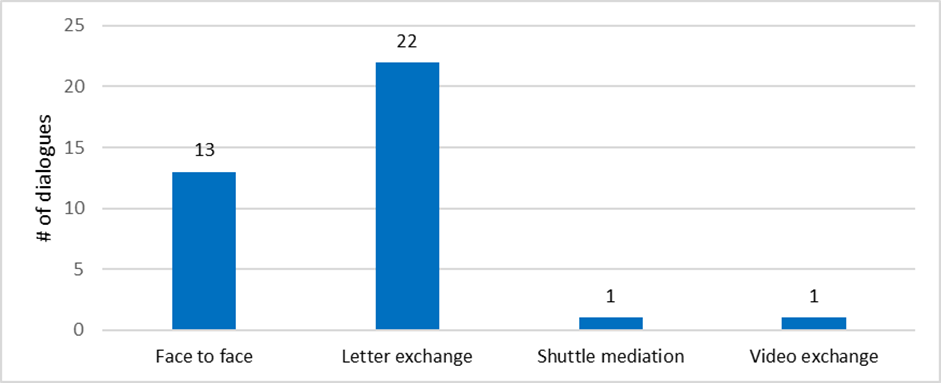

Types of facilitated dialogue in fiscal year 2022 to 2023

Text version

Vertical bar chart showing the number of dialogues conducted for each of the types of communication used by participants during fiscal year 2022 to 2023.

- 13 face-to-face dialogues

- 22 letter exchanges

- 1 shuttle mediation

- 1 video exchange

The RO program provides VOM services that include a number of RJ processes or types of facilitated dialogue. For example, participants can meet face-to-face (includes in-person or by videoconference), correspond in writing, have a circle process and/or exchange video messages. The mediator can also relay messages back and forth between participants (referred to as “shuttle mediation”). The needs of participants help guide the type(s) of dialogue used.

Four types of dialogues were used in FY 2022 to 2023, namely face-to-face, letter exchange, shuttle mediation and video exchange. For the second FY in a row, there has been an increase in the use of letter exchanges to communicate between parties. There is a 38% increase from FY 2021 to 2022 (n=16) to FY 2022 to 2023 (n=22). This may be residual effects from the pandemic years where letter exchanges were favoured. However, it may also be because some participants are not ready to meet face-to-face and may use the letter exchange process as a starting point.

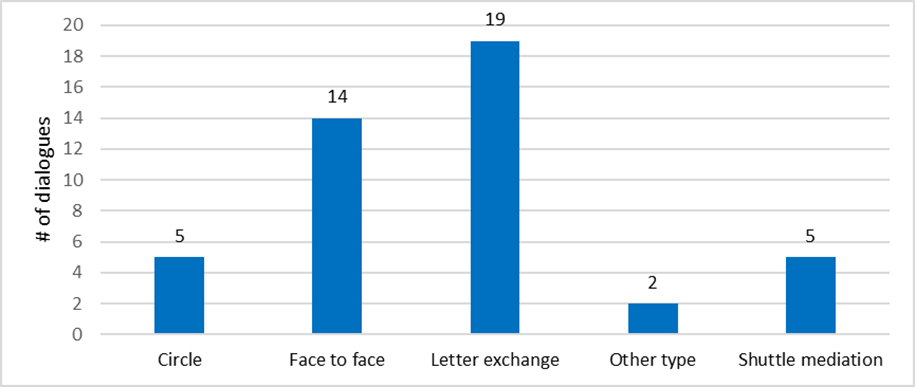

Types of facilitated dialogue in fiscal year 2023 to 2024

Text version

Vertical bar chart showing the number of dialogues conducted for each of the types of communication used by participants during fiscal year 2023 to 2024.

- 5 circles

- 14 face-to-face dialogues

- 19 letter exchanges

- 2 other types

- 5 shuttle mediations

Types of facilitated dialogues used by RO participants during FY 2023 to 2024 were circle, face-to-face, letter exchange, shuttle mediation and other type, which included using teleconference calls. Letter exchanges continued to outnumber other types of dialogue. This may be a form of communication participants preferred during the pandemic years given the infection prevention and control measures that limited the option of in-person communication within carceral settings.

It is worth noting that in FY 2023 to 2024, the use of face-to-face dialogues (n=14) increased by 40% compared to FY 2021 to 2022 (n=10), most likely due to the gradual removal of restrictions on infection prevention and control measures during this period, which allowed for the resumption of direct contact under certain conditions.

The average number of each type of facilitated dialogue over the last 5 years (2018 to 2023), totaling an average of 36 processes annually, is as follows:

- Circle: 1

- Face-to-face: 14

- Letter exchange: 17

- Other: 2

- Shuttle mediation: 2

Fiscal year 2023 to 2024 saw a 25% increase in the total number of facilitated dialogues (n=45) as compared to the total annual average since 2018 (n=36). However, the number for each type of facilitated dialogue in FY 2023 to 2024 is not back to the pre-pandemic levels. The results for FY 2022 to 2024 suggest that we are gradually returning to these levels.

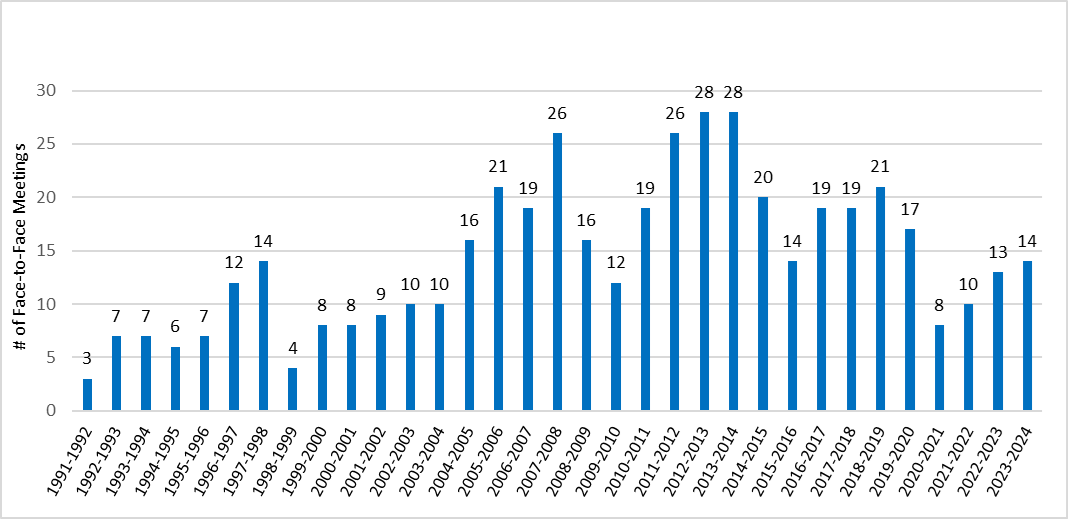

Face-to-face dialogues 1992 to 2024

The RO program has been committed to facilitating face-to-face dialogues since the inception of the program. In-person meetings are often requested because they provide the most meaningful form of communication, allowing for verbal and non-verbal communication. Meetings can often take many hours, if not days, which is not feasible on a videoconferencing platform. Often, ceremony might be a component of the face-to-face dialogue. For these reasons, meetings are prioritized. They also incur the most cost out of all methods of facilitating dialogue, which is why CSC reports on them specifically.

While videoconferencing remains a valid alternative to in-person meetings, in-person meetings continue to be the preferred method of communication for the delivery of VOM services. The program is using videoconferencing in certain situations, such as when the participants do not want to meet in person or there are logistical challenges that prevent them from doing so. That said, VOM services are only offered virtually if they are accessible to all participants, without placing an unmanageable financial or administrative burden on victims, offenders or CSC.

Face-to-face meetings per year

Between 1992 and 2024, 317 offenders participated in 503 face-to-face dialogues.

Text version

Vertical bar chart showing the number of face-to-face dialogues held between victims and offenders, by fiscal year (FY).

- FY 1991 to 1992: there were 3 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1992 to 1993: there were 7 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1993 to 1994: there were 7 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1994 to 1995: there were 6 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1995 to 1996: there were 7 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1996 to 1997: there were 12 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1997 to 1998: there were 14 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1998 to 1999: there were 4 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 1999 to 2000: there were 8 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2000 to 2001: there were 8 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2001 to 2002: there were 9 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2002 to 2003: there were 10 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2003 to 2004: there were 10 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2004 to 2005: there were 16 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2005 to 2006: there were 16 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2006 to 2007: there were 21 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2007 to 2008: there were 19 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2008 to 2009: there were 26 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2009 to 2010: there were 16 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2010 to 2011: there were 12 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2011 to 2012: there were 26 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2012 to 2013: there were 28 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2013 to 2014: there were 28 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2014 to 2015: there were 20 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2015 to 2016: there were 14 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2016 to 2017: there were 19 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2017 to 2018: there were 19 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2018 to 2019: there were 21 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2019 to 2020: there were 17 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2020 to 2021: there were 8 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2021 to 2022: there were 10 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2022 to 2023: there were 13 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

- FY 2023 to 2024: there were 14 face-to-face meetings between victims and offenders

A multitude of factors can cause the number of dialogues to fluctuate per year. Prior to 2004, the program was being provided by the Community Justice Initiatives (CJI) in the Pacific region alone. As of FY 2004 to 2005, there was a significant increase in face-to-face meetings likely due to VOM services being provided nationally. Any other variances are likely due to varying number of referrals year to year, readiness of participants, and other variables beyond the program’s control.

In FY 2023 to 2024, the number of face-to-face meetings (n=14) increased by 75% compared to FY 2020 to 2021 (n=8), when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Videoconferencing was used in a limited number of cases, while in-person face-to-face dialogues were carried out in accordance with CSC’s infection prevention and control (IPC) measures (for example: masks, physical distancing, et cetera).

Number of face-to-face meetings per offender

Due to the serious nature of the offences addressed by the RO program, and because participants’ needs may evolve throughout the process, VOM services are flexible and emphasize the importance of preparation and tailoring processes to the participants’ specific and individual needs. The program operates on the principle that a one-size-fits-all approach and prescribed timelines can cause greater harm.

Some cases may require more than one face-to-face meeting. Participants are offered choices and have a say throughout the process. To date, 70% (n=225) of cases have resulted in at least one in-person meeting.

The table below shows the total number of face-to-face meetings held since 1992 for the 317 offenders who participated in one or more VOM facilitated dialogues. In over two thirds of the cases, a single meeting was sufficient to meet the needs of the participants.

|

1 Meeting |

2 Meetings |

3 Meetings |

4 Meetings |

5 Meetings |

6 + Meetings |

|

225 (70%) |

61 (19%) |

17 (5%) |

8 (3%) |

4 (1%) |

6 (2%) |

Offender participant snapshot

Age

At the time of their offence, the age of the 317 offenders ranged from 15 to 77, with an average age of 33. Their age at the time of their first VOM face-to-face meeting ranged from 18 to 85, with an average of 42.

Gender

Of the 317 offenders, 298 (94%) identify as male, and 19 (6%) identify as female. These ratios are the same as those for the general federally sentenced offender population:

|

Federal offender status |

Women |

% |

Men |

% |

Total |

|

Incarcerated and on release |

1231 |

6 |

19,576 |

94 |

20,807 Footnote 4 |

Religious affiliation

Out of the 317 offenders who participated in face-to-face dialogues, 236 (74%) identified as practicing a religion or as having a spiritual belief. Of those 236, 15 offenders (6%) declared to be practicing some form of Indigenous spirituality. The remaining offenders did not identify as practicing a religion or identified as Atheist.

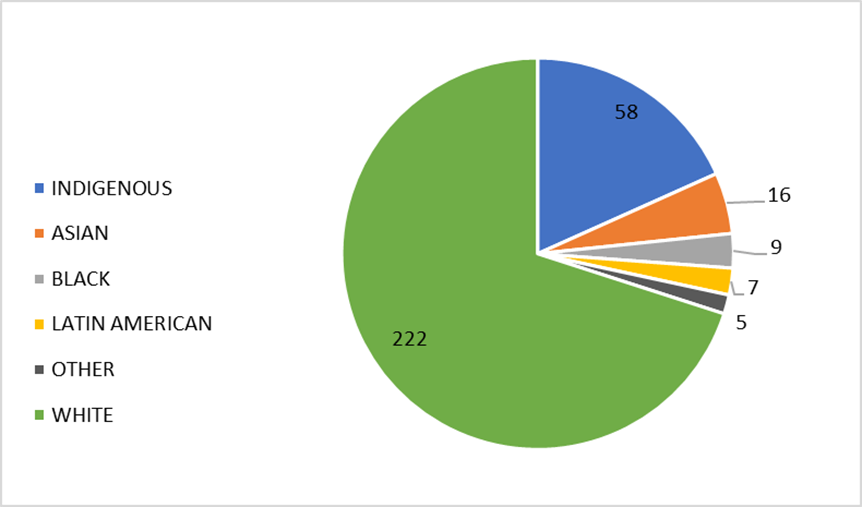

Racial identity

Of the 317 offenders who participated in face-to-face dialogues, the majority identified themselves as White (n=222 or 70%), which exceeds the proportion of the CSC offender population who self-reported as White (51.8%) Footnote 5.

18% (n=58) of participants self-identified as Indigenous. FY 2021 to 2022 was marked by a 1% increase over the previous year in the number of participants who self-identified as Indigenous. Since then, this ratio has remained unchanged. While this is higher than the percentage of Indigenous Peoples who self-identified as an Indigenous person in Canada's 2021 Census of Population (5%) Footnote 6, it is below the Indigenous representation in the total federally sentenced and incarcerated offender population (28.1%) Footnote 7.

5% (n=16) self-identified as Asian Footnote 8, 3% (n=9) self-identified as Black, and 2% (n=7) self-identified as Latin American.

Text version

Pie chart divided into 6 sections of different sizes that illustrates which racial identity offenders who participated in a face-to-face meeting identified with, from 1992 to 2024.

- Indigenous: 58

- Asian: 16

- Black: 9

- Latino American: 7

- Other: 5

- White: 222

Risk and needs

Of the 317 offenders who participated in face-to-face dialogues, 276 were assessed at the time of intake, and after their admission into custody, and remained consistent prior to their participation in the RO program. The majority were rated as having a high risk of recidivism and moderate needs for intervention, such as, correctional programming.

As per the risk and needs assessment done following the completed VOM face-to-face dialogue, the 276 offender participants who were assessed as high risk at the time of intake showed a decrease in their risk to reoffend by 14% (n=37) following the face-to-face. They also displayed lower levels of need for interventions by 26% (n=71).

|

Risk level |

Prior to face-to-face |

Following face-to-face |

|

High |

51% |

32% |

|

Medium |

38% |

37% |

|

Low |

11% |

29% |

|

Needs level |

Prior face-to-face |

Following face-to-face |

|

High |

32% |

31% |

|

Medium |

37% |

40% |

|

Low |

29% |

30% |

Many factors can positively influence an offender's progress during their sentence. It would be reductive to assume that the above-mentioned results are directly related to participation in a face-to-face meeting. Nevertheless, those who participate in a face-to-face process are generally ready and open to engage in, or continue, a transformative journey. RJ processes acknowledge and address the factors that may have contributed to their criminal offending, with the people harmed by the crime(s). This may create a deepened sense of offender accountability, understanding, remorse, and the will to embrace prosocial attitudes, behaviors, and address criminogenic factors.

Index offences

Offence types

For the 317 offenders, the offences for which a VOM face-to-face meeting was sought include:

- murder, manslaughter or attempted murder (50%)

- sexual offences (28%)

- robberies or break and enter (6%)

- driving offences causing death or bodily harm (6%)

- assaults (4%)

- death by criminal negligence (3%)

- kidnapping and forcible confinement (1%)

- threat and criminal harassment (1%)

- other (1%)

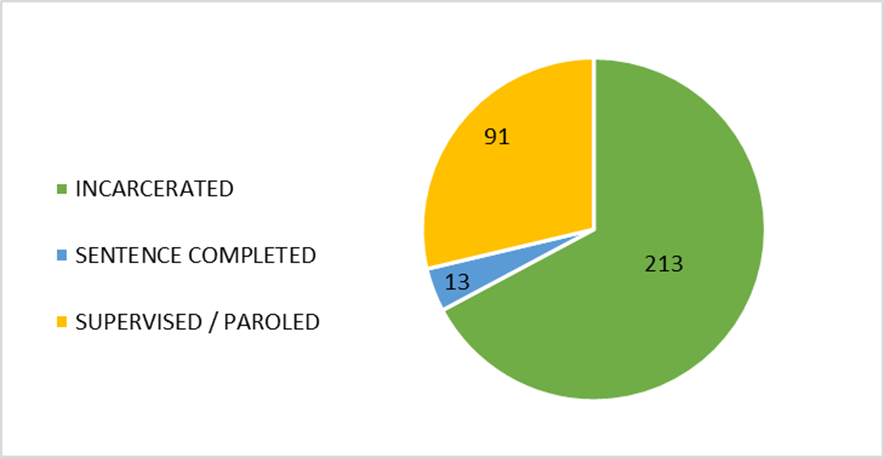

Conditional release success statistics

Text version

Pie chart that contains three sections of different sizes that illustrate the status of offenders at the time of the face-to-face meeting:

- Incarcerated: 213

- Sentence completed: 13

- Supervised / Paroled: 91

Offender participants’ current status

Of the 317 offenders, 51 are presently incarcerated; 242 have either reached warrant expiry or are on release; 3 are temporarily detained following a suspension of their conditional release; 17 are deceased; and 4 were deported.

|

Sentence completed |

Incarcerated |

Supervised |

Deceased |

Deported |

Suspended/ Temporary detention |

|

165 (52%) |

51 (16%) |

77 (25%) |

17 (5%) |

4 (1%) |

3 (1%) |

Re-offending following VOM face-to-face

Recidivism

Of the 267 offenders who were either on release when they participated in a VOM face-to-face meeting or who were subsequently released:

- 98% had not re-offended within 1 year of their face-to-face meeting

- 91% had not re-offended within 5 years of their face-to-face meeting

- 90% had not re-offended by year 10

The 267 offenders who had participated in a face-to-face meeting were less likely to re-offend than other offenders who had also finished their sentence between FY 1991 to 1992 and FY 2023 to 2024 Footnote 9. When comparing re-offending rates after 5 years, 84% of offenders who had not participated in a face-to-face meeting had not re-offended. Therefore, there was 6% less recidivism after 5 years from offenders who had participated in a face-to-face VOM dialogue with the person they harmed.

Various factors may influence an offender’s success post-release. A recent study Footnote 10 shows that offenders successful on release, particularly those with lower levels of need at intake, were more likely to have participated in institutional programs that fostered acceptance of responsibility for one’s criminal behaviour and adoption of prosocial attitudes. While it cannot be concluded that participation in a face-to-face meeting has a causal relationship with success upon release, the RO program does encourage meaningful accountability and recognition of harm. In addition, the sample size of the comparison group is far greater than the number of offenders who participated in a face-to-face meeting. Nevertheless, those that do participate in a face-to-face process tend to do well when released.

Offences committed post-VOM

Of the 317 offenders involved in face-to-face meetings (this includes all offenders who were on release at the time of their face-to-face meeting, subsequently released, and incarcerated at the time of this report:

- 287 offenders (91%) had not committed a new offence

- 30 offenders (9%) had committed a new offence

Types of offences that occurred post-VOM

Of the 30 offenders convicted of a new offence post-VOM, offences included:

- robbery as their major offence (n=6)

- assault (n=3)

- sexual assault as their major offence (n=2)

- criminal harassment (n=2)

- possession of substance for trafficking (n=3)

- dangerous operation of a motor vehicle (n=2)

- break, enter and commit (n=2)

- breach of long-term supervision order (n=2)

- escape lawful custody or being at large without excuse (n=2)

- possession of weapons contrary to prohibition order (n=1)

- under a provincial statute (n=1)

- kidnapping (n=1)

- indecent act with intent to insult (n=1)

- attempt all other indictable offences (n=1)

- failure to comply with condition of under recognizance (n=1)

25 (83%) of the new charges are for lesser offences than those for which the face-to-face VOM dialogue was sought.

Qualitative feedback

Although CSC regularly receives positive feedback from participants about the RO program and their experience, it does not systematically collect information about the impact of the program due to the highly personal nature of their experience and particiants’ need for confidentiality.

However, in FY 2024 to 2025, the RO program will celebrate it’s 20th anniversary as a national program. In preparation, CSC’s Restorative Justice Division conducted a series of interviews with mediators, victims and offenders to illustrate the impact of the RO program and its VOM facilitated dialogues from diverse perspectives. These interviews allow us to share a glimpse into their stories, as well as some personal reflections. Below are two quotes from these interviews: namely the perspectives of a mediator, and of a victim. The third one is from an offender, who shared his thoughts in his own written words, to include in the journal article of the American Parole and Probation Association, Perspectives, published in 2021.

Mediator’s perspective:

“Through the Restorative Opportunities program, there is room for all experiences in the work that we do. It’s about making space for people to feel seen, heard, and understood and meet people where they are at.”Footnote 11

Victim’s perspective:

“[…] it was probably one of the most spiritual moments. […] it reminds me daily that I'm a force to be reckoned with and I can do hard things, […] and it just puts me in a headspace of how no matter what happens, something can bring two people together and can bring understanding in an impossible situation. […] I knew that this wasn't my journey. This wasn't the offender’s journey. It was me finishing my brother's journey. And that made me very proud.”Footnote 12

Offender’s perspective:

“It was very difficult coming to terms with the extent of harm I was responsible for. It really was so much worse than it had ever occurred to me. That comprehension was also the most potent catalyst for change. Footnote 13

There can be nothing as viscerally real and elucidating as the victim-offender mediation process; consequently, there can be no greater opportunity for true insight and healing.” Footnote 14

Observations and conclusion

From FY 2020 to 2021 up to 2022 to 2023, CSC’s RO program was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic that required adherence to infection prevention and control measures to avoid and reduce the risk of transmission. With the gradual reduction of these measures, FY 2023 to 2024 saw a greater return to normal for services provided by the RO program within correctional environments. The number of new referrals (n=140) was on par with the average number of referrals received over the last 5 years and the numbers of all types of facilitated dialogues were higher than in previous years.

The program relies on the ability for mediators to travel and meet with participants of the program, in order to have face-to-face meetings, complete preparation, and deliver a process that meets the participants’ needs. The RO program continues to maximize available resources to provide in-person service delivery to participants, complemented with other forms of communications, such as virtual meetings, teleconferencing, and telephone calls.

Annex A: Research and evaluation

A qualitative evaluation (Roberts, 1995) demonstrated high levels of satisfaction for both victims and offenders. For victims, they reported having greater control over their safety and their lives, and that the process offered them a measure of closure. For offenders, in addition to personal growth, they reported having a greater commitment to addressing their criminogenic needs. Staff interviewed confirmed a higher commitment on the part of those offenders to participate actively in their correctional plan.

In addition, Rugge (2006) examined the effects on participant’s physical and psychological health. Both victims and offenders exhibited positive changes over the course of the program in relation to the pre-post Physical Health Checklist and to the pre-post Psychological Health Checklist. There was a significant positive difference between participants who experienced a victim-offender meeting and those who did not.

Victim and offender participants of the RO program have also provided feedback on their experience participating in the program to CSC’s RJ Division. Overall, participants show great satisfaction, finding strong support from the RO mediators and highlighting their level of professionalism, honesty, and dedication. Victims expressed their expectations being met and, in some cases, surpassed. Many offenders expressed an increased level of empathy toward the victim and appreciation for the compassion the mediators provided them.

In May 2013, a Preliminary Analysis of the Impact of the Restorative Opportunities Program was conducted by CSC’s Research Branch. The preliminary examination indicated that the program shows promise in reducing recidivism. The trend suggested that after one year of release, offenders involved in a face-to-face had fewer returns to custody despite lower reintegration potential and motivation ratings.

Following the Preliminary Analysis the Research Branch conducted, in 2015 an Analysis of the Impact of the Restorative Opportunities Program on Rates of Revocation was published. The findings from the study provide support for RO program participation, particularly when meetings were offered in the community. The results also suggested that taking part in RO while in the institutions may reduce revocation rates over time.

In 2018, The Impact of Participation in Victim-Offender Mediation Sessions on Recidivism of Serious Crime, was published in the International Journal of Offender Treatment and Comparative Criminology, Volume 62, Issue 12, pp.3910 to 3927.

Lastly, in 2021, the article, Transforming lives: Demonstrating the power of victim-offender mediation for those who have experienced serious crime in Canada, was published in Perspectives, The Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association, Volume 45(2), pp. 36 to 43.

For more information visit: Restorative justice - Canada.ca