CSC Audit and Evaluation of Structured Intervention Units, June 8, 2025

Official title: Correctional Service of Canada Joint Audit and Evaluation of Structured Intervention Units, June 8, 2025: Internal Audit and Evaluation Sector

Catalogue number: PS84-255/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-78252-2

Alternate format

On this page

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Background

- Structured Intervention Unit model and framework

- Operationalization

- Management of inmates

- Overview of Structured Intervention Unit transfers

- Transfer authorizations

- Transfers out

- Overview of procedural safeguards

- Procedural safeguards

- Overview of conditions of confinement

- Conditions of confinement

- Offers of time outside of cell

- Overview of programming, interventions, services, and leisure

- Effectiveness of programming, interventions, and leisure

- Overview of health care

- Effectiveness of Health Services

- Oversight and performance

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: Structured Intervention Units logic model

- Appendix C: Audit objectives and criteria

- Appendix D: Evaluation questions

- Appendix E: Evaluation questions and audit criteria based on logic model components

- Appendix F: Scope and approach

- Appendix G: Legislation and policy framework

- Appendix H: Statement of conformance

- Footnotes

List of acronyms and abbreviations

Acronyms and abbreviations

- A4D

- Assessment for Decision

- ADCCO

- Assistant Deputy Commissioner, Correctional Operations

- AWI

- Assistant Warden, Interventions

- AWO

- Assistant Warden, Operations

- BSC

- Behavioural Skills Coach

- CCRA

- Corrections and Conditional Release Act

- CCRR

- Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations

- CD

- Commissioner’s Directive

- CM

- Correctional Manager

- CPO

- Correctional Programs Officer

- CPU

- Correctional Plan Update

- CO

- Correctional Officer

- DBT

- Dialectical Behaviour Therapy

- DW

- Deputy Warden

- EMRS

- Electronic Medical Record System

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GBA

- Plus Gender-based Analysis

- HARS

- Health Accreditation Reporting System

- HRMS

- Human Resource Management System

- IAES

- Internal Audit and Evaluation Sector

- IEDM

- Independent External Decision Maker

- IH

- Institutional Head

- IIS

- Intensive Interventions Strategy

- ILO

- Indigenous Liaison Officer

- ISH

- Indigenous Social History

- LTE-SIU

- Long-Term Evolution-Structured Intervention Unit

- MAP

- Management Action Plan

- MHNS

- Mental Health Needs Scale

- MIIS

- Manager, Intensive Intervention Strategy

- MM-SIU

- Motivational Module - Structured Intervention Unit

- MM-SIU-I

- Motivational Module - Structured Intervention Unit - Indigenous

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- OMS

- Offender Management System

- PD

- Performance Direct

- PO

- Parole Officer

- PPA

- Personal Portable Alarm

- RBAEP

- Risk-based Audit and Evaluation Plan

- RHQ

- Regional Headquarters

- RM

- Restricted Movement

- RSPO

- Regional Senior Project Officer

- SDS

- Scheduling and Deployment System

- SIU

- Structured Intervention Unit

- SIU-CIB/IDT

- Structured Intervention Unit Correctional Intervention Board/Interdisciplinary Team

- SIU-CPU

- Structured Intervention Unit - Correctional Plan Update

- SIURC

- Structured Intervention Unit Review Committee

- SPO

- Social Programs Officer

- TRA

- Threat Risk Assessment

- WHMIS

- Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System

Further definitions can be found in Appendix A.

List of figures on this page

List of figures

- Figure 1: Percentage of inmates with complex needs and risks: year-end snapshots from April 2020 to March 2023

- Figure 2: Race distribution in the SIU versus general population: year end snapshots from April 2020 to March 2023

- Figure 3: SIU comparison between planned funding and actual expenditures (in millions)

- Figure 4: Infrastructure planned funding and actual expenditures (in millions)

- Figure 5: Turnover rate in the SIU

- Figure 6: Vacancy rate in the SIU

- Figure 7: Rate of assaults on staff by inmates (per 1,000 inmates)

- Figure 8: Rate of assaults on inmates by inmates (per 1,000 inmates)

- Figure 9: Rates of use of force incidents (per 1,000 inmates)

- Figure 10: Rate of transfer in per 1,000 inmates

- Figure 11: Rate of transfer out per 1,000 inmates

- Figure 12: Average number of days between IH decision to actual transfer

- Figure 13: Average number of days between IH decision to actual transfer out for inmates who did not refuse transferring out

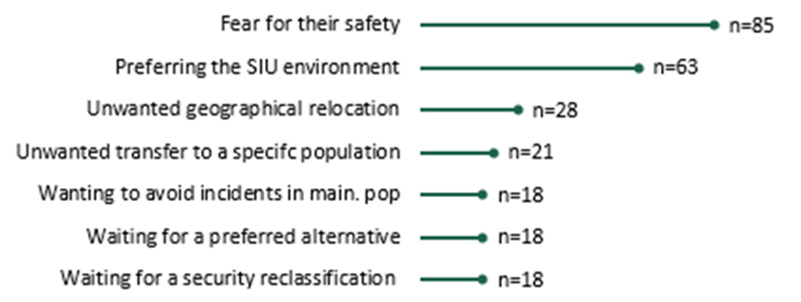

- Figure 14: Most cited reasons for inmate refusals (n= number of respondants)

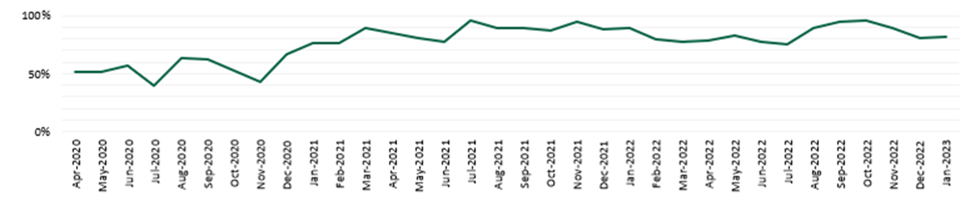

- Figure 15: Percentage of days when time outside of cell was offered versus accepted

- Figure 16: Percentage of days when interaction time was offered versus accepted

- Figure 17: Percentage of TRAs by completeness of information

- Figure 18: Percentage of SIU-CPUs with missing considerations by type

- Figure 19: Percentage of MM-SIU and MM-SIU-I program reports with missing information by type

- Figure 20: Timelines or program access upon authorization to an SIU

- Figure 21: Percentage of inmates assigned to programs

- Figure 22: Percentage of files in which the module (M) was selected

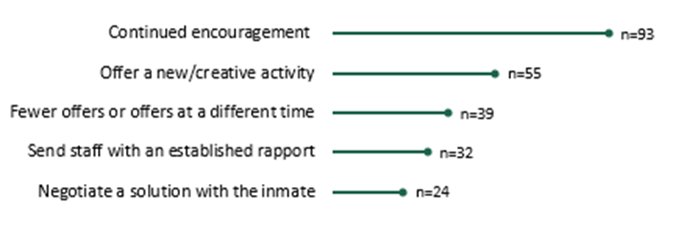

- Figure 23: Most cited strategies to encourage inmates to avail themselves for activities (n= number of respondents)

- Figure 24: Percentage of inmates with a negative change in mental health

- Figure 25: Percentage of cases where inmates in the SIU received appropriate levels of care

- Figure 26: Percentage of inmates who received treatment based on level of need, sex, and racial group

- Figure 27: Percentage of inmates who refused to participate in health assessments by race

- Figure 28: Percentage of successful transfers out of SIUs (CSC’s target range: 61.9% to 70%)

- Figure 29: Average and median length of stay in the SIUs (CSC’s median target range: 15.1 to 24.9)

- Figure 30: Structured Intervention Units logic model [in Appendix B]

- Figure 31: Evaluation questions and audit criteria based on logic model components [in Appendix E]

List of tables on this page

List of tables

- Table 1: Management action plan for recommendation 1

- Table 2: Management action plan for recommendation 2

- Table 3: Management action plan for recommendation 3

- Table 4: Management action plan for recommendation 4

- Table 5: Management action plan for recommendation 5

- Table 6: Structured Intervention Units logic model

- Table 7: Evaluation questions and audit criteria based on logic model components

Background

About the Joint Audit and Evaluation

Objectives

The Joint Audit and Evaluation of Structured Intervention Units (SIUs) was conducted as part of Correctional Service of Canada’s (CSC) 2022 to 2027 Risk-based Audit and Evaluation Plan (RBAEP).

This engagement built upon CSC’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Sector (IAES) review of the SIU implementation (2019) as well as the SIU Audit Readiness Engagement (2022).

Key areas were selected for exploration.

- Compliance: provide assurance that CSC is complying with relevant legislation and policies related to SIUs

- Effectiveness/Performance: assess the achievement of expected outcomes and Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) differences

- Efficiency: assess the efficiency of the SIU model

- Management Framework: provide assurance that a management framework is in place to support SIUs

- Relevance: assess the continued need for SIUs and alignment with departmental and federal government priorities and responsibilities

Scope and approach

Evidence was collected at 9 men’s institutions and 5 women’s institutions using a mixed-methods approach.

- Interviews were conducted with over 240 participants from May 2023 to November 2023, which included staff at the national, regional, and institutional levels, as well as inmates

- Observation of various SIU processes and procedures were conducted by the engagement team for over 70 hours throughout multiple points of the day and evening across the institutions visited between May 2023 and July 2023

- Document and literature review of scholarly articles, internal and external reports, and other documents

- Administrative data analysis covering the period from April 2016 to April 2024 from internal databases, including:

- Electronic Medical Record System (EMRS)

- Health Accreditation Reporting System (HARS)

- Human Resource Management System (HRMS)

- Offender Management System (OMS)

- Performance Direct (PD)

- Scheduling and Deployment System (SDS); and

- Long-Term Evolution-Structured Intervention Unit (LTE-SIU)

- File review and testing of over 1,400 inmate-related files and data records covering the period from October 2021 to November 2023

It is acknowledged that the COVID-19 global pandemic had a significant impact on the operations of CSC. It is understood that certain aspects of the implementation and operation of the SIUs during the scope period of the joint audit and evaluation may have been affected.

Additional details about the Joint Audit and Evaluation can be found in Appendix B to F.

About Structured Intervention Units

The SIUs were introduced by Bill C-83 - An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA)Footnote 1 , that received Royal Assent on June 21, 2019. The purpose of the bill was to strengthen the federal correctional system. This included the elimination of administrative and disciplinary segregation and the establishment of the SIU correctional model.

There are 15 SIUs across all regions of the country. They are located within 10 men’s institutions and 5 women’s institutions.

Legislative and policy requirements guide the operationalization of SIUs and the management of inmates in SIUs. Key legislative requirements for the SIUs are included within sections of the CCRA and the Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations (CCRR).

CSC also developed SIU policy instruments, such as Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 711 and its associated guidelines.

Pursuant to CCRA section 34(1) and CD 711, a staff member may authorize the transfer of an inmate into an SIU if the staff member is satisfied that there is no reasonable alternative to the inmate’s confinement in an SIU and the staff member believes on reasonable grounds that the inmate has acted, has attempted to act or intends to act in a manner that jeopardizes the safety of any person or the security of a penitentiary and allowing the inmate to be in the mainstream inmate population would jeopardize the safety of any person or the security of the penitentiary, the inmate’s safety, or would interfere with an investigation.

The LTE-SIU application was developed to support the management of inmates in SIUs. The tool records the interventions and activities offered to inmates. It also records additional information regarding the interactions that are taking place.

In alignment with CCRA and CD 711 requirements, an infographic available on CSC’s intranet provides an overview, as outlined below, of how SIUs differ from segregation.

- structured interventions are tailored to address inmates’ specific needs

- inmates have the opportunity to spend a minimum of 4 hours a day outside of their cell, including 2 hours a day of meaningful human contact

- more rigorous and regular reviews, including by someone external to CSC (such as, Independent External Decision Makers [IEDMFootnote 2 ])

- inmates are to be seen daily by a healthcare professional

- individualized approach focused on skills-based interventions and activities

- the goal is to provide inmates with the tools they need to return to a mainstream inmate population as soon as possible, and to prevent a return to an SIU

A full list of institutions with an SIU can be found in Appendix F.

Additional details about the SIUs regulatory framework can be found in Appendix G.

Structured Intervention Unit model and framework

Examples of staff perceptions about Structured Intervention Unit

Staff perceive and experience the SIU environment in different ways due to various reasons and factors.

Staff expressed the following sentiments about their experiences in the SIU:

Vision and objectives

"We push them to transfer too quickly. Inmates are hot potatoes - get them out fast. [We should] take the time with inmates to work with them… but we don't take the time and we're more concerned about the 2 [hours of interaction with others] and [hours of time out of cell]."

Policy

"[It is] Clear to me but know some line staff struggle with wordiness of policies. SIU policy is long winded when compared to other policies. It's hard for COs [correctional officers] to find simple answers in policy."

"The SIU policy doesn't account for offenders that do not want to engage."

Multidisciplinary approach

"Our site is good at the interdisciplinary team. We share a lot of info. People have said we really work well together here. The SIURC [SIU Review Committee] has a lot of staff come in, everyone is involved."

Human resources

"Some folks struggle with the type of inmates here. You deal with a lot and can experience burnout."

"No extra incentive to work in the SIU. The workload is way more compared to any other post."

Transfer authorizations

"There is a lot of pressure not to transfer inmates to the SIU."

Effectiveness of programming, interventions, and leisure

"There are some offenders that just can't get along with anybody (staff and inmates) and cycle through institutions. Those who just want solitary confinement. Gang members who have burned their bridges everywhere. We take our turns with these inmates. They are the real seg[regation] guys."

"The inmates live well in the SIU. They like it here… We can't get them out."

"Program not actually designed to address what's going on. Doesn't talk about when you're the victim… Also, the program is not designed for people who don't want to go out with anyone. Have to do the program the way it's designed but model doesn't work for everyone."

"It's hard for staff to understand as they get more services than gen[eral] pop[ulation]. Think we privilege this little group at the detriment of gen pop… It's hard to access interventions, but SIU has daily access. Warden visits every day. There's an imbalance."

Measuring performance

"Say we have a guy who historically was in seg for years and got them to mainstream population and lasted 2 weeks, that's a success, then maybe next time they last 3 weeks. Anytime [we’re] assisting [the] offender to get to better place, think it's a success."

Disclaimer: The staff quotes used above, as well as any other staff quotes used throughout the report, were based on interview notes that were taken by the audit and evaluation team during institutional visits. Quotes may have been adapted for clarity and readability.

Examples of inmate perceptions about the Structured Intervention Unit

Inmates perceive and experience the SIU environment in different ways due to various reasons and factors.

SIU inmates expressed the following sentiments about their experiences in the SIU:

Safety and security

"It’s prison, you don’t know until you get there. Security and safety is always a risk."

Infrastructure

"This place should not be an SIU. The infrastructure needs to be changed. It has old bones and they threw lipstick on it."

Conditions of confinement

"Wish seg still existed, more than happy to be left alone. Enjoy being by myself, I'm not a people person. I want peace and quiet. We weren't pushed back then like today to get out."

Transfer out of the Structured Intervention Unit

"I wanted to leave the SIU by choice through getting my medium security. I didn't want to transfer out to another region."

"[I have] concerns for my safety in gen pop."

Effectiveness of programming, interventions, and leisure

"It would be more beneficial if we could continue to follow our correctional plan in the SIU. Can't have someone come in and complete a [mainstream] program. SIU is dead time and not working towards correctional plan other than school. It delays me from progressing."

"There are pros and cons to both… Seg is not better for services, no one could argue there's more services in the SIU. But for a set routine seg was different… Seg had a set routine as opposed to the SIU. Get what you get whenever they want to give it to you."

"Before I accepted more, now I refuse. It doesn't help you reintegrate now. It doesn't address the issue; it doesn't lower your security level."

"They're good here, they ask often… Just to hear offers are nice, they ask often over the day."

"There's no difference in segregation and SIU, but at least here you can get out in groups."

"The difference in the SIU is that you get out of cell a lot more. You can't compare women's and men's SIU, in men's there's so many offenders but it can be very lonely in women's."

Disclaimer: The inmate quotes used above, as well as any other inmate quotes used throughout the report, were based on interview notes that were taken by the audit and evaluation team during institutional visits. Quotes may have been adapted for clarity and readability.

Structured Intervention Unit inmate profile

Length of stay

For the SIU population at large, the median number of days spent in an SIU was 21.

Administrative data from April 2020 to March 2023 revealed that:

- the median number of days spent was higher for Indigenous inmates (26 days) and lower for women (6 days); and

- inmates who had a previously identified mental health need spent slightly more time in the SIU than those who did not

Comparison with general population

Compared to the general population, inmates in the SIUs more frequently had complex needs and risks.

Text equivalent for Figure 1.

The image shows the percentage of inmates with complex needs and risks. This is based on year-end snapshots from April 2020 to March 2023. The needs and risks display the following:

- dynamic needs level of high (73% general population, 97% SIU)

- low reintegration potential (50% general population, 90% SIU)

- violent index offence (79% general population, 85% SIU)

- security level maximum (13% general population, 84% SIU)

- low motivation (17% general population, 57% SIU)

- high substance use needs (35% general population, 56% SIU)

- affiliated with a security threat group (13% general population, 37% SIU)

- mental health need (20% general population, 34% SIU)

- currently at risk for self-harm (1% general population, 5% SIU)

Demographic characteristics

The SIU population is more likely to be men, younger, Indigenous, or Black.

A year-end snapshot analysis comprising of multiple years (April 2020 to March 2023) revealed that 1% of all inmates were transferred at least once to an SIU. Of those:

- 98% were men (versus 95% in the general population)

- 95% were under 50 years old (versus 74% in the general population); and

- 22.5% were visible minorities (versus 17% in the general population)

Black and Indigenous inmates were overrepresented.

Text equivalent for Figure 2.

The image shows the race distribution in the SIUs versus the general population. This is based on year-end snapshots from April 2020 to March 2023. The data in the graph is as follows:

- Indigenous (44% SIU, 32% general population)

- white (32% SIU, 48% general population)

- Black (14% SIU, 9% general population)

- other (10% SIU, 11% general population)

Indigenous women were overrepresented in the SIUs (86%, 6 out of 7) versus in the general population (47%, 861 out of 1,844).

Further definitions can be found in Appendix A.

Structured Intervention Unit vision and objectives

The general vision, objectives and expectations for SIUs have been identified through various mechanisms and align with federal and corporate priorities. Although institutional management considered that a clear vision and objectives for the SIUs had been established or in part established, it was found that the vision and objectives were contradictory and may not be attainable due to operational realities.

Identifying and communicating the vision and objectives

The general vision, objectives and expectations for SIUs are identified in:

- legislation, regulations, and various CSC policy instruments (CDs, guidelines, memos, interim policy bulletins); and

- monitoring mechanisms such as national dashboards and performance indicators

The vision and objectives for the SIUs were further communicated through staff training when SIUs were first established and top-down messaging.

- this has contributed to a common understanding of the vision, objectives, priorities, and envisioned outcomes for the SIU

SIU objectives are aligned with CSC’s mandate, policies, and corporate priorities, and lessons learned from the previous segregation model.

SIU objectives further complement broader federal priorities of public safety and humane treatment.

Implementing the vision and objectives

While institutional management generally perceived the vision and objectives for SIUs as clear, operational realities and experiences suggest that clarity diminishes in practice.

Challenges with operationalizing the SIU vision and objectives are due to the contradiction between providing programming, interventions, and services that respond to an inmate’s specific needs and risks and the expectation that inmates be transferred out of the SIU as soon as possible. Staff indicated that the focus is more on transferring inmates out of the SIU at the earliest opportunity instead of ensuring an effective correctional planning process that responds to an inmate’s specific needs.

As a result, inmates are not always getting the programming, interventions, and services they need before being transferred out of the SIU, which does not support CSC’s mandate, strategic priorities, and the intended vision and objectives for SIUs.

Structured Intervention Unit vision and objectives

As per CCRA section 32, “The SIUs were designed to provide an appropriate living environment for an inmate who cannot be maintained in the mainstream population for security or other reasons; and provide the inmate with opportunities for meaningful human contact and participation in programs, and to have access to services that respond to the inmate’s specific needs and risks.”

As per CCRA section 33, “An inmate’s confinement in a structured intervention unit is to end as soon as possible.”

CSC’s mandate

Contribute to public safety by actively encouraging and assisting offenders to become law-abiding citizens, while exercising reasonable, safe, secure, and humane control.

CSC’s corporate priorities

- Safe management and supervision of offenders during their transition from the institution to the community

- Safety and security of the public, victims, staff and offenders in institutions and the community

- Effective, culturally appropriate interventions and reintegration support for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit offenders

- Effective and timely interventions in addressing mental health needs of offenders

- Efficient and effective management practices that reflect values-based leadership in a changing environment

- Productive relationships with diverse partners, stakeholders, victims' groups, and others involved in support of public safety

Policy

Policy development

The SIU policy was developed and promulgated before all operational realities of the SIUs could be understood. In the interim, guidance was disseminated and made accessible through various methods. This created challenges in ensuring that all staff were referring to the most up-to-date requirements and guidance.

- when the SIU policy was first introduced it was based on a theoretical model which had not been operationally tested

- the current policy was promulgated in November 2019 and, apart from interim policy bulletins and memorandums, has not been updated since the inception of the SIU. The SIU policy suite is currently under review and is expected to be updated by Spring 2025

- additional guidance was created (memos, interim policy bulletins, email communications, etc.) to support the operations of the SIUs (for example, clarification of roles and responsibilities and specification of some operational requirements)

- however, not all SIU policy instruments were found in 1 easy to navigate repository. CSC’s intranet, “the Hub”, contained some of the revised guidance but not all information was on the same webpage

- staff expressed that this has created issues when applying policy and guidance. Some documentation superseded previous guidance but there was no indication in the previous documentation that new guidance had been issued. As a result, policy and associated guidance may not be applied as intended

Clarity of policy

SIU policy instruments include areas that are unclear or where gaps exist.

- the role of health care and mental health within the SIU (for example, with respect to health care assessments, medication delivery, open door policy for daily health care visits)

- terminology used (for example, “authorized” versus “approved”, “working day” versus “calendar day”)

- addressing the needs of complex inmates (including those who refuse to transfer out of the SIU)

- SIU infrastructure requirements

- the scope of activities and interventions provided in the SIU

- what constitutes conditions of confinement

- what is considered a meaningful interaction

Gaps or lack of clarity in SIU policy instruments have resulted in lack of awareness and oversight, which have resulted in non-compliance with associated legal requirements, such as:

- meeting the requirements for time out of cell and interaction with others

- meeting health care requirements

- meeting institutional requirements

- ensuring an inmate’s transfer to an SIU is for the shortest time possible

SIU policy instruments have also been interpreted differently by staff in institutions or across institutions, which has resulted in inconsistent application and potential differences in the operation of the SIUs.

"There is a lot of policy around the SIUs. The SIU is complex, but this is still too much policy. A lot of the policy is driven by emails and word of mouth. It's changing and evolving. People struggle to follow it because there is so much."

Additional details about the SIUs policy framework can be found in Appendix G.

Governance

Governance structure

A governance structure is in place across all levels of the organization that is generally clear and supports the SIU. However, some concerns were noted.

Various institutional management are involved with the SIU while also having responsibilities in other areas of the institution. These positions include:

- Institutional Head (IH)

- Deputy Warden (DW)

- Assistant Warden, Interventions (AWI); and

- Assistant Warden, Operations (AWO)

The implementation of SIUs has resulted in increased workload for these positions given the differences in managing inmates in the SIU when compared to the former segregation model.

The SIU governance model establishes different roles and accountabilities for institutional management depending on circumstances or based on a decision that must be taken. There is no one position working directly within the SIU on a full-time basis that has overarching responsibility for the day-to-day operations of the SIU.

Indirect reporting relationships exist which can result in inconsistent or conflicting direction being provided. For instance, health care staff and some interventions staff (for example, teachers, Elders, Indigenous Liaison Officers [ILOs]) directly report to individuals outside the SIU but have informal relationships with SIU-specific managers.

Unclear and inconsistent reporting structures exist. For example, it is not consistent from region to region who certain positions report to, and for certain positions it is not clear if they report to individuals at the institutional level or the regional level.

Some management and staff at all levels of the organization feel it is not always clear who to contact at National Headquarters (NHQ) when they have SIU-related questions, as some issues are both operational and “corporate“ in nature.

Decision-making within the SIU is challenging at times, especially when there are different opinions on expectations between different groups (operations, interventions, health care).

There is usually an attempt to resolve matters at the working level first, prior to escalating to management/senior management. However, with the current structure, security often takes priority despite the various groups’ different objectives. This has resulted in friction amongst staff at times.

Institutional management has suggested that the identification or addition of a specific position in charge of the SIU at the AWI or DW level would be beneficial for decision-making and due to the workload associated with SIU operations.

Information sharing

Formal and informal sharing mechanisms are in place at the national, regional, and institutional levels for the purposes of regular information sharing and direction setting. Institutional management receives support from management at other institutions, Regional Headquarters (RHQ), and NHQ regarding the SIU. However, some institutional management feel that improvements could be made at the national level.

At the institutional and regional levels:

- institutional level staff involved with the SIU typically have discussions with each other on a bi-weekly basis

- many institutional management are in regular contact with the Regional Senior Project Officer(s) (RSPO)Footnote 3 ; and

- institutional staff communicate with staff at other institutions to share information and best practices and discuss reintegration options for inmates

At the national level:

- NHQ has established meetings with various SIU-related stakeholders at all levels of the organization; and

- expectations are reviewed, continually revisited, and clarified during these meetings for the institutions and regions

Some institutional management feel that support at the national level could be improved. It was mentioned that the focus at the national level tends to be more on compliance and oversight (for example, reviewing data quality, overseeing the number of inmates who have been authorized to the SIU, verifying whether inmates were offered 4 hours of time out of cell and 2 hours of interaction with others each day) instead of providing support directly to the institutions.

Formal information sharing mechanisms (for example, updates to SIU-related policy and guidance documentation such as interim policy bulletins, memos, and other electronic communications) support a common understanding of expectations and contribute to ensuring that key decisions and relevant information are effectively communicated.

Informal mechanisms (for example, SIU-related meetings, discussions, and other correspondence) contribute to providing management and staff at various levels with a support system to regularly obtain information on topics such as:

- SIU case information (including complex cases)

- SIU policy and process-related requirements, concerns, and updates

- SIU human resources updates

- LTE-SIU application updates

- good practices

- monthly reporting; and

- infrastructure

Some staff occupying newly introduced positions such as Behavioural Skills Coaches (BSCs) and SIU Data and Activity Coordinators, or positions that differ in terms of their context in the SIU such as social programs officers (SPOs), have supported their peers at other institutions by sharing ideas and practices to better understand their role in the SIU.

Roles and responsibilities

Understanding of roles and responsibilities

Management and staff generally understand their roles and responsibilities related to the SIU. However, some duties are not documented, resulting in ambiguity and uncertainty.

It is not always clear how SIU positions and associated roles should work within the context of the SIU versus how they work in the mainstream population (for example, teacher, SPOs, mental and physical health).

- a document review confirmed that standardized job descriptions were often being used and did not always include SIU-specific roles and responsibilities

CD 711 and its associated guidelines outline additional SIU-related roles and responsibilities of some staff working in and supporting SIUs. However, not all staff with SIU-related roles and responsibilities are referenced within the CD and guidelines (for example, BSCs and SIU Data and Activity Coordinators), and some expectations are not clearly identified (for example, expectations of the SIU parole officer (PO) versus the inmate’s PO from general population versus the PO at the institution where the inmate is being transferred to).

Some staff in newly created positions (for example, BSCs and SIU Data and Activity Coordinators) felt their role was not fully defined, which was further confirmed through a document review of their job descriptions.

CD 711 indicates that the approving authority for an inmate’s authorization to transfer to an SIU is the AWI. Most of the time, regions are requiring ADCCO consultation and/or agreement before an inmate SIU transfer. This direction was not found within CSC’s policy instruments and some AWIs expressed concerns with this process, as it risks impacting the impartiality of the AWI in the authorization process.

Structured Interventions Unit-related training

Although CSC is currently in the process of developing SIU-specific training, staff often cited that they received little to no preparation or training prior to working in the SIU and mostly learned on the job. Not all staff fully understand the roles of other positions within the SIU.

Staff expressed a desire for further training on mental health, crisis intervention, the LTE-SIU application, and the vision and objectives for the SIU.

While training provided to staff was most often on the LTE-SIU application, some staff who did not receive this training expressed a desire to receive it.

Some staff expressed a lack of understanding of the roles and responsibilities of other positions that work in the SIU, as well as a lack of understanding of how their position differed from other positions that work in the SIU.

Inadequate training may increase the risk to staff and inmate safety. Not fully understanding others’ roles and responsibilities within the SIU causes frustration for staff because they do not know why certain positions are working in a certain manner.

It was mentioned that informal training or information sessions would be beneficial to understand the role of each position working in the SIU.

Operationalization

Multidisciplinary approach

Coordination of work among Structured Interventions Unit staff

Positions from various disciplines were added to institutions and assigned specifically to the SIU.

Examples of positions added to the SIUs include:

- SPOs

- POs

- Correctional Program Officers (CPOs)

- COs

- Elders

A multidisciplinary approach is taken in the SIU. Staff were observed working together. This helps improve the operations and functioning of the SIU and supports a holistic and coordinated approach to managing inmates in the SIU.

78% of the staff interviewed felt that the SIU team was taking a multidisciplinary approach to working with inmates.

72% of the staff interviewed felt that they were part of the multidisciplinary team.

At the institutions, the staff were discussing specific inmate’s cases and their planned approach.

- Document review and interviews also indicated that most institutions are having SIU Correctional Intervention Board or Interdisciplinary Team (SIU-CIB/IDT) meetings on a regular basis to discuss SIU inmates, as outlined in CD 711.

- The meetings include representatives from operations, interventions, and health care

Having staff assigned specifically to work in the SIU contributes to ensuring a consistent approach and better coordination of activities through the rapport built between staff.

Challenges with multidisciplinary approach

Some positions do not feel part of the SIU team. At times, staff were found to be working in silos and not sharing information between disciplines.

Certain positions amongst the intervention staff reported that they did not feel like they were part of the multidisciplinary team.

Some issues were identified during observations and interviews.

- for example, in the SIU some COs were observed not communicating with intervention and case management staff about the timing of inmates’ movement or why movement was not taking place. Staff appeared to become frustrated during these interactions

- some correctional staff still holding what was expressed as the “segregation” mentality

- at times, Elders were not respected when requesting assistance

Some institutional management and staff identified concerns regarding staff not taking a multidisciplinary approach. For example, correctional staff did not always respect interventions or health care staff (for example, not supporting proposed plans for inmate interactions, ignoring or not making them feel welcomed when entering the range, etc.) and a culture change was still required to move away from what was expressed as the “segregation” mindset.

Based on file reviews and interviews, although each discipline (interventions, operations, health care) is consulted as part of the decision-making process, some positions within those disciplines are not always consulted. For example, some COs and Elders indicated that they were not consulted. Although policy indicates that all staff must actively explore and consider all reasonable alternatives to confinement in an SIU, the COs explained that it was often left to the managers.

A definition for SIU-CIB/IDT can be found in Appendix A.

Financial information

Structured Interventions Unit funding

The implementation and ongoing operation of the SIUs has cost more than anticipated in the planned funding requestFootnote 4 .

Over the 4 years analyzed, SIU expendituresFootnote 5 have consistently exceeded the forecasted spending for SIU activities. Expenditure in excess of forecasts fluctuated between approximately $1.0 million and $9.5 million over the 4 yearsFootnote 6 . However, as CSC had authority to redistribute funds as appropriate, CSC has managed the creation of SIUs without exceeding the total funding received for the Transforming Federal Corrections initiative (Bill C-83).

Text equivalent for Figure 3.

The image shows the SIU comparison between planned funding and actual expenditures (in millions) between fiscal year 2019 to 2020 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The years display the following:

- 2019 to 2020 ($16.6 planned, $23.7 expenditure)

- 2020 to 2021 ($31.1 planned, $39.7 expenditure)

- 2021 to 2022 ($31.8 planned, $41.3 expenditure)

- 2022 to 2023 ($43.0 planned, $44.0 expenditure)

There was no planned operations and maintenance (O&M)Footnote 7 budget for infrastructure. However, significant expenditures were incurred for this purpose.

Construction projects were undertaken at some institutions prior to the SIUs becoming operational, and there are still changes being made. This has included adding:

- common rooms

- program rooms

- Indigenous specific rooms

- barrier rooms

- interview rooms

- yards

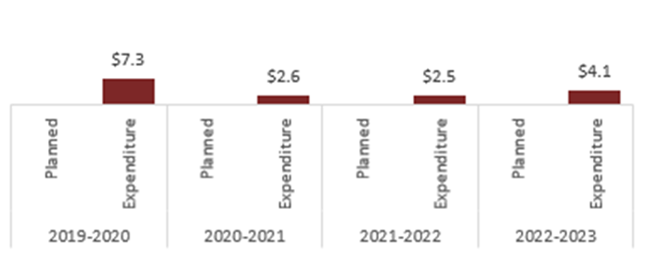

Text equivalent for Figure 4.

The image shows the planned funding and actual expenditures (in millions) for infrastructure between fiscal year 2019 to 2020 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The years display the following:

- 2019 to 2020 ($0 planned, $7.3 expenditure)

- 2020 to 2021 ($0.0 planned, $2.6 expenditure)

- 2021 to 2022 ($0.0 planned, $2.5 expenditure)

- 2022 to 2023 ($0.0 planned, $4.1 expenditure)

Note about years identified in graphs:

- 2019 to 2020 is April 2019 to March 2020

- 2020 to 2021 is April 2020 to March 2021

- 2021 to 2022 is April 2021 to March 2022

- 2022 to 2023 is April 2022 to March 2023

Human resources

Funding additional resources

Since inception, additional funded positions have been added to the SIUs. There is enough funding for all positions identified in the SIU model; however, institutions are adding positions in surplus of the SIU model and as a result, institutions are having to use funds which were identified for other areas of the institution for these additional positions.

As a result of a CSC needs analysis, additional human resources costing over $16 million have been added to the SIU beyond the initial funding.

Positions added include:

- BSCs

- CPO

- POs

- SIU managers

- SIU Data and Activity CoordinatorsFootnote 8

Administrative positions were also added at the regional and national levels.

There have been additional management, correctional and interventions staff added at some institutions which are funded internally to help relieve SIU-related workload pressures and are not covered by funding allocated for SIUs.

- based on interviews and requests made to institutions to identify positions which are funded internally, many institutions will add additional staff to the SIU when the number of inmates approaches maximum SIU capacity. This results in less resources being available for non-SIU inmates

- for interventions positions such as POs, SPOs, and CPOs, some are added on a temporary basis, while others are added on a permanent basis

- for COs, this additional coverage in the SIU is provided through extra duty posts or operational enhanced security. At times, due to the fluid nature of the SIU population, these additional CO positions working in the SIU are not captured as SIU-specific positions in the SDS; therefore, it is difficult for CSC to determine the full number of CO positions required to operate the SIU on a daily basis

The full cost of human resources allocated to SIUs is not known. This impacts CSC’s ability to accurately track and assess staffing needs and financial expenditures. Additionally, there are financial and operational impacts on other areas of the institutions.

An SIU environmental scan completed in June 2023 identified that SIU positions are not currently coded to differentiate them from the overall positions within the institution where they are located, which restricts the availability of data specific to SIU positions.

- not having all SIU positions identified and differentiated from the overall positions within the institution also limits the ability to properly assess workloads of SIU staff and allocate additional funding for these positions

- some institutions become dependent on these additional positions, which cannot be guaranteed without permanent funding. This leaves CSC vulnerable to not meeting its legislative obligations and fulfilling its mission and objectives should challenges continue due to various factors (for example, fiscal climate or increased number of SIU transfers)

As well, operationally, institutions are adjusting staffing levels within other areas of the institution and reassigning those staff to the SIU. This reduces the ability for other areas of the institution to function as intended or increases the risk of security-related incidents occurring.

Staff vacancies and turnover

Staff vacancies and turnover exist within the SIUs. This impacts the overall functioning of the SIUs, leads to inconsistency and instability within the SIU team, and increases workloads for staff.

Although additional CO coverage has been provided in SIUs at some institutions, correctional staff in the SIU had higher turnoverFootnote 9 and vacancy rates, compared to non-correctional staff in the SIU.

Text equivalent for Figure 5.

The image shows the turnover rate in the SIU for correctional and non-correctional staff. Correctional staff are 32% and non-correctional staff are 14%.

Text equivalent for Figure 6.

The image shows the vacancy rate in the SIU for correctional and non-correctional staff. Correctional staff are 18% and non-correctional staff are 7%.

Correctional Manager (CM) positions had the highest turnover rate for correctional staff in the SIUs (43%).

ILOs experienced the highest turnover rate for interventions positions in the SIUs (40%). Both Indigenous Correctional Program Officers and ILOs have the highest vacancy rate amongst the intervention staff in the SIUs (16%).

Interviewees noted repeated turnover for intervention positions such as SIU managers, SPOs, CPOs, and POs.

Over a quarter (28%) of institutional staff interviewed reported wanting to leave the SIU in the next 2 years, as the SIU is considered to be a more demanding posting than others in the institution.

Staff vacancies and turnover results in instability within the SIU team, which can also increase the risk of errors or negatively affect the ability to build a consistent rapport between inmates and staff.

Interviewees noted frustration among inmates in the mainstream population related to the perception that resources are being taken away from them to support the SIUs in meeting legislative requirements.

Staff interviewed also expressed feelings of frustration, discouragement, stress, and lack of motivation to fulfill their roles and responsibilities because of a heavy workload, busy schedule, and inmates being disengaged or refusing to avail themselves of the opportunity to spend time out of cell.

Most commonly, it was mentioned by staff interviewed that more interventions staff are needed, which included CPOs, POs, Indigenous Interventions staff, and SPOs. For example, there is a need for more Elders and staff supporting Indigenous inmates as these staff carry high caseloads.

Additionally, some staff would like to see scheduling changes for some interventions staff to allow for additional support and coverage during evenings and weekends.

Although there are several challenges for staff working in the SIU, approximately half of staff interviewed (51%) liked working there.

The following reasons were cited:

- challenging work environment

- valuable learning experience

- great staff to work with

- feeling of being a role model; and

- meaningful work

Safety and security

Prevalence of assaults and incidents among populations

Inmates who had been authorized to transfer to an SIU demonstrated higher rates of involvement in assaults when compared to the mainstream population and the previous segregation model.

Prior to the implementation of SIUs a risk was identified that CSC will not be able to maintain required levels of operational safety and security in institutions with the elimination of segregation.

The rates of assault on staff by inmates, and on inmates by inmates (with the exception of 2022 to 2023), were higher for inmates who had been authorized to transfer to an SIU compared to the general population and the previous segregation model. The surge in assaults against staff was mainly driven by assaults involving fluids or waste.

The rate of use of force incidents was also higher for inmates who had been authorized to transfer to an SIU. Most use of force incidents are related to incident types “Behaviour Related” (for example, disruptive behaviours) or “Assault Related” (for example, inmate fight). Rates were higher at women’s institutions than at men’s institutions.

This increase in rates of assaults and incidents is further substantiated by interview responses referencing a changing inmate profile (such as, younger, more violent or having more complex needs), particularly at women’s institutions.

Text equivalent for Figure 7.

The image shows the rate of assaults on staff by inmates (per 1,000 inmates) between fiscal year 2016 to 2017 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The years display the following:

- 2016 to 2017 (20 segregation model, 8 general population)

- 2017 to 2018 (27 segregation model, 11 general population)

- 2018 to 2019 (31 segregation model, 12 general population)

- 2020 to 2021 (19 general population, 92 SIU)

- 2021 to 2022 (24 general population, 114 SIU)

- 2022 to 2023 (24 general population, 97 SIU)

The data for fiscal year 2019 to 2020 was not applicable.

Text equivalent for Figure 8.

The image shows the rate of assaults on inmates by inmates (per 1,000 inmates) between fiscal year 2016 to 2017 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The years display the following:

- 2016 to 2017 (101 segregation model, 61 general population)

- 2017 to 2018 (103 segregation model, 69 general population)

- 2018 to 2019 (96 segregation model, 85 general population)

- 2020 to 2021 (111 general population, 140 SIU)

- 2021 to 2022 (129 general population, 159 SIU)

- 2022 to 2023 (152 general population, 120 SIU)

The data for fiscal year 2019 to 2020 was not applicable.

Text equivalent for Figure 9.

The image shows the rate of use of force incidents (per 1,000 inmates) between fiscal year 2016 to 2017 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The years display the following:

- 2016 to 2017 (123 segregation model, 46 general population)

- 2017 to 2018 (116 segregation model, 54 general population)

- 2018 to 2019 (132 segregation model, 59 general population)

- 2020 to 2021 (106 general population, 308 SIU)

- 2021 to 2022 (107 general population, 332 SIU)

- 2022 to 2023 (112 general population, 271 SIU)

The data for fiscal year 2019 to 2020 was not applicable.

Note about incident data: An incident occurred if 1 of the participants in the incident (no limitations on role and/or involvement) had an active SIU authorization for transfer on the incident date. Therefore, the data includes inmates who met any of the 3 SIU authorization criteria.

Note about years identified in graphs:

- 2016 to 2017 is April 2016 to March 2017

- 2017 to 2018 is April 2017 to March 2018

- 2018 to 2019 is April 2018 to March 2019

- 2019 to 2020 is April 2019 to March 2020

- 2020 to 2021 is April 2020 to March 2021

- 2021 to 2022 is April 2021 to March 2022

- 2022 to 2023 is April 2022 to March 2023

Safety and security concerns

Concerns regarding safety and security in the SIU were prevalent amongst staff and inmates.

Some staff that experienced threats or assaults from inmates, expressed concerns with unpredictable behaviour and the volatility of some inmates.

Interventions staff shared concerns with not being properly escorted or monitored. Some recalled incidents of being alone or locked in program rooms with inmates for an extended time.

Some staff also expressed their concern for themselves or for others, particularly women working in men’s institutions. A review of Threat Risk Assessments (TRAs) as well as on-site observations confirmed that some inmates have male-only protocols in place due to the nature of their behaviours towards women.

45% of inmates interviewed reported not feeling safe in the SIU as they feel other inmates can be hostile and violent.

Both inmates and staff expressed that incidents have occurred where incompatibles crossed paths, resulting in physical altercations.

Addressing concerns

Overall, the safety and security of staff and inmates in the SIU are taken seriously with procedures put in place when deemed necessary.

Management reported addressing staff safety concerns by adapting operations and procedures as needed; for instance, requiring the use of barriers during inmate interactions when it is supported by a TRA.

Some staff expressed concerns regarding insufficient communication of TRAs and the need to use barriers, as well as the pressure to remove barrier restrictions early or feeling a reluctance to use them.

Staff interviewed explained that inmates’ safety and security concerns are reported to correctional staff and appropriate measures are taken; for instance, by strategically changing how an inmate is grouped with others.

Infrastructure

There are concerns related to institutional safety and security due to inadequate infrastructure.

Observations and staff interviews identified many infrastructure issues that led to safety and security concerns. They include:

- lack of cuff slots to facilitate handcuffing an inmate

- insufficient number of cameras

- program areas out of sight

- availability and use of Personal Portable Alarms (PPA) and portable radios

- furniture or equipment not bolted down

Infrastructure and equipment

Inconsistent infrastructure

CSC has not established minimum standards for infrastructure in the SIU. This has resulted in significant variations across SIUs in terms of the number, size, and locations of areas available for inmates to utilize.

SIUs were placed into pre-existing locations within the institutions; thus, there were limitations to the design of the units. For instance, non-SIU inmates reside on ranges within the same buildings as the SIU, and the location of many of the spaces such as rooms and yards were already established. This means that at some institutions, non-SIU inmates are within visual and/or physical proximity of the SIU and in some cases, time spent in rooms and yards is split between SIU and non-SIU inmates.

A review of the number of spaces available for inmates to spend time out of cell revealed significant variances across institutions. When comparing the institutions visited, it was found that some SIU inmates are not able to be out of cell with other inmates or can only do so in small groups (2 to 3 inmates); therefore, if all inmates wanted access to a yard or room, or the SIU was at full capacity, it would not be possible for all inmates to be out of their cell.

Impacts of infrastructure

CSC has not established minimum standards for infrastructure in the SIU. This has resulted in significant variations across SIUs in terms of the number, size, and locations of areas available for inmates to utilize.

In addition to the safety and security concerns previously identified (refer to "Safety and Security" section for additional information), 90% of institutional staff and management have concerns with the existing infrastructure at their SIU location they most frequently cited the need for more inmate spaces.

Through interviews and observations, it was noted that at some institutions, there were not enough areas (for example, yards and rooms) available for inmates, or it took a significant length of time to move an inmate from their cell to the designated area. For example:

- due to the layout of the SIU, inmates could often not be moved out of their cell while other inmates were moving, which often delayed the start of an inmate’s time out of cell; and

- at times, inmates would be willing to accept an offer to come out of their cell, but there were no rooms available

As noted through interviews and observations, due to the unavailability of barrier-free spaces, some interactions took place through barriers when there was no need to have them in place.

"Have to consider the infrastructure. We can barely get by with what we have now."

Equipment for inmates

Minimum standards for equipment available to inmates in the SIU have not been established by CSC, resulting in significant variances in availability.

National minimum standards have not been established for the equipment available for inmate use in the SIUs, such as workout equipment, phones, kitchen appliances (for example, fridge, microwave), washers and dryers. This has resulted in significant variances in the amenities available for inmates to utilize while out of their cells.

It was noted during interviews and observations that equipment availability for inmate use is important to encourage inmates to come out of their cells. For example, having an insufficient number of phones available impacts an inmate’s ability to remain in contact with those outside the institution, including family and community ties.

There are a number of additional items that inmates and staff would like to see added to SIUs, including:

- basketball nets and yard benches

- better or more gym equipment

- microwaves

- computers

- additional phones

- televisions

Staff expressed concerns that inmates are often breaking the available equipment and that they are not able to protect it. Having to constantly replace the equipment that inmates are breaking results in additional costs to CSC.

Some additional equipment and infrastructure changes have taken place or are planned (for example, adding gym equipment into the outdoor yards). These changes will address some of the need for additional items.

Management of inmates

Overview of Structured Interventions Unit transfers

An overview of the procedures related to transfers is presented below.

- pursuant to CCRA section 34(1), an inmate may be authorized to transfer into an SIU based on 1 or more of the following criteria: the inmate jeopardizes the safety and security of the institution, the inmate’s safety would be jeopardized if they were to remain in the mainstream population, or the inmate remaining in the mainstream population would interfere with an ongoing investigation

- pursuant to CD 711, the AWI, during regular business hours, or the CM in charge of the institution outside of regular business hours, is responsible for authorizing an inmate’s transfer to the SIU. This authorization will be cancelled within 5 working days if a reasonable alternative is identified

- pursuant to CD 711, inmates are transferred to an SIU once all reasonable alternatives have been explored and if the SIU is determined to be the least restrictive measure available

- pursuant to CSC Guidelines 081-1, an inmate can file a grievance when they believe that a decision for or against a transfer to an SIU was unfair or improperly made, or when they want to get into or out of an SIU. This includes grievances on the procedures pertaining to a transfer to an SIU; right of recourse to the services of legal counsel at the time of transfer; any subsequent reviews and recommendations; and the rationale for remaining in an SIU. Decisions made by IEDMs cannot be grieved

Transfer authorizations

Rate of transfer authorization

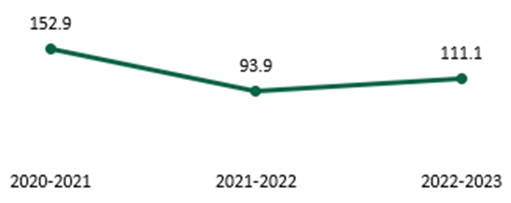

Rates of transfer authorizations to the SIU have varied over the years.

National transfer authorization rates significantly decreased from 2020 to 2021, to 2021 to 2022 but increased in 2022 to 2023.

Text equivalent for Figure 10.

The image shows the rate of transfer in per 1,000 inmates between fiscal year 2020 to 2021 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The points are labelled as

- 152.9 (2020 to 2021)

- 93.9 (2021 to 2022)

- 111.1 (2022 to 2023)

Men consistently had higher transfer authorization rates than women.

Indigenous inmates had higher transfer authorization rates than non-Indigenous inmates.

Note about years identified in graph:

- 2020 to 2021 is April 2020 to March 2021

- 2021 to 2022 is April 2021 to March 2022

- 2022 to 2023 is April 2022 to March 2023

Reasons for transfer authorization

The profile of inmates transferred to the SIU has changed over the years.

Initially, most inmates were transferred to the SIU for jeopardizing the safety and security of the institution (58.3% in 2020 to 2021). However, over time, the most common reason for transfer was for the inmate’s own safety (49.8% in 2021 to 2022 and 50.4% in 2022 to 2023).

Interviewees explained that some institutions have felt pressured to accept inmates with more challenging profiles. When these inmates impose their influence on the population, this results in an increased risk for victimization.

Documentation for transfer authorization

In accordance with policy, all SIU authorizations analyzed were completed within the required timeframes and were either completed directly by the AWI or confirmed or cancelled the next working day by the AWI. However, some forms did not include documented evidence of consultation with the inmate’s Case Management Team.

100% (75/75) of SIU authorization forms analyzed included the incident description or circumstances for transfer.

71% (53/75) of SIU authorization forms analyzed included evidence of consultation with the Case Management Team. The 29% (22/75) of SIU authorization forms analyzed that were missing this evidence took place after hours (such as, evenings and weekends). Documenting evidence of consultation with the inmate’s Case Management Team supports CSC’s ability to demonstrate that all reasonable and viable alternatives to a transfer to an SIU have been explored, as required by CD 711.

Although the criteria for authorizing an inmate transfer to the SIU were clear and understood, 54% (36/67) of institutional management interviewees mentioned that they have challenges applying them.

For instance, some inmates may satisfy multiple authorization criteria (which cannot be entered into the LTE-SIU), and there can be uncertainty around the appropriate recording of authorizations for inmates who resist to integrate into a non-SIU population (as this is a scenario not covered in legislation and policy).

Regional staff review SIU authorization forms to confirm whether the legislative criteria was met to authorize an inmate transfer to the SIU. However, the risk remains that staff authorized a transfer when it should not have been authorized, thus resulting in non-compliance with legislation.

Factors influencing transfer authorizations

There are various contextual factors that influence a decision-maker’s judgement in the consideration to transfer an inmate to the SIU.

The main contextual factors identified by interviewees included:

- reluctance or hesitancy to use the SIU (for example, pressure to keep the number of transfer authorizations low)

- insufficient time to investigate the incident or the inmate prior to authorizing a transfer to the SIU; and

- availability of alternatives, particularly when they are all perceived to have been exhausted

As referenced by some staff and observed during institutional visits, in response to pressure to keep SIU numbers low, inmates who otherwise would have been authorized for a transfer to the SIU based on meeting the legal criteria are sometimes housed in other ranges in the institution.

Interviews and file review of SIU authorization forms confirmed that institutions are working to ensure that various factors and alternatives are considered prior to a transfer to the SIU. Examples include:

- institutional or inmate safety

- inmate comments/statements

- informal conflict resolution

- needs or risks of inmate

- cultural interventions

- suitability of another institution; and

- security reclassification

Indigenous Social History considerations on transfer authorizations

In accordance with legislative and policy requirements, documentation exists to demonstrate that ISH is considered as part of the SIU authorization process. However, there are challenges when considering the ISH in the context of the authorization.

Some institutional management feel that it was not clear how ISH factors apply to the transfer authorization and that ISH does not impact the decision to authorize the inmate into the SIU if the inmate’s risk in the institution supersedes the factors.

Interviewees also noted challenges in finding culturally appropriate alternatives for Indigenous inmates when a transfer to the SIU is being considered.

Alternatives to Structured Interventions Unit at women’s institutions

There is a lower number of transfers to the SIU at women’s institutions. This is largely due to the availability of alternative options and the interdisciplinary team approach to the Intensive Interventions Strategy (IIS) at women’s institutions.

Staff at women’s institutions credited their low number of SIU transfers to:

- availability of options specific to women’s institutions (for example, Structured Living Environment Units and Enhanced Support Houses)

- effective programming, activities, or interventions

- lower number of inmates overall

- characteristics of women (for example, women are generally less violent, prefer building relationships, and less likely to misdirect anger towards others when compared with men); and

- effective interdisciplinary approach

However, infrequent use of the SIU presented challenges for staff, who often needed to refamiliarize themselves with SIU policy each time a woman was authorized to the SIU.

At some women’s institutions, unused SIU cells were repurposed for other uses (for example, medical isolation or observation). At times, this impacted opportunities for time out of cell or interaction time for SIU inmates (for example, due to disruptions on the SIU range or not being able to use the range to facilitate activities).

Transfers out

Rates of transfers out

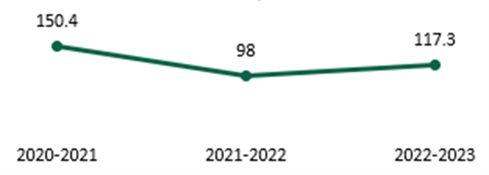

Rates of transfers out of the SIU have varied over the years.

The goal of SIUs is to return the inmate to mainstream population as soon as safely possible. National transfer out rates significantly decreased between 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 but increased in 2022 to 2023.

Of the fiscal years (FYs) analyzed, 2020 to 2021 was the only FY where the transfer out rate was lower compared to those that were transferred in (refer to “Transfer Authorizations” section for trend data).

Text equivalent for Figure 11.

The image shows the rate of transfer out per 1,000 inmates between fiscal year 2020 to 2021 to fiscal year 2022 to 2023. The points are labelled as:

- 150.4 (2020 to 2021)

- 98 (2021 to 2022)

- 117.3 (2022 to 2023)

Men had consistently higher transfer out rates than women.

Indigenous inmates had higher transfer out rates than non-Indigenous inmates.

Note about years identified in graph:

- 2020 to 2021 is April 2020 to March 2021

- 2021 to 2022 is April 2021 to March 2022

- 2022 to 2023 is April 2022 to March 2023

Transferring to a new institution

There is consultation with, and support from, receiving institutions for intra-regional and inter-regional transfers. However, there are challenges with transfer documentation.

File review data noted that institutions are being consulted prior to transfer and that receiving institutions are typically supportive; however, some interviewees noted that at times the receiving institutions are not in agreement with the transfer that is being proposed making it more of a challenge to find a suitable population to transfer the inmate to.

Gaps were noted with regards to information that was included within Assessments for Decisions (A4Ds), as a review of A4Ds found that 38% (8/21) did not reference any previous SIU transfers and 29% (6/21) did not provide a summary and analysis for previous SIU transfers.

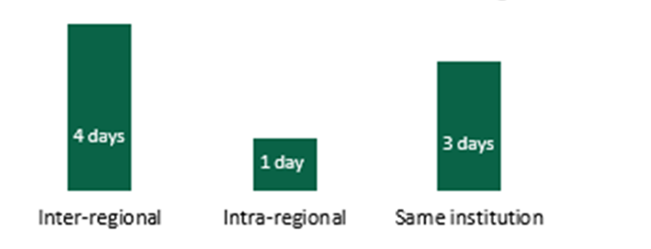

Transfer times

Transfer times did not reflect the actual amount of time required to arrange a transfer, the strains on staff and resources, and the infrequency of ground transportation and flights.

An analysis of transfer time subsequent to an IH decision to transfer an inmate out of the SIU suggested that the actual amount of time to arrange a complete transfer was not being captured.

- the median transfer times were less than a day

- the average varied from 8 to 17 days

Text equivalent for Figure 12.

The image shows the average number of days between IH decision to actual transfer for inter-regional, intra-regional, and the same institution. Inter-regional, intra-regional, and same institution transfers are 17, 8, and 12 days, respectively.

Longer wait times for transfers within the same institution may have occurred when a decision had been rendered to transfer the inmate out of the SIU but after this decision was made, the inmate’s behaviour suggested that they may still pose a risk to their own safety, to others or to the security of the institution. As a result, the inmate was not immediately transferred out.

Inmates are prioritized for flights depending on their specific circumstances, but due to the infrequency of intra-regional ground transportation and inter-regional flights, inmates have at times been required to remain in the SIU at their current institution for longer than necessary. This issue is compounded at women’s institutions as inter-regional transfers are often the only choice.

Other challenges with transfers out included inmates needing to remain in the SIU while awaiting court, the transfer of inmate property, and limited population options to transfer inmates due to incompatibles. These challenges complicated the ability to facilitate the transfer of some inmates following an approved transfer decision and placed additional strains on resources.

Readiness for transfer out

The objective to transfer an inmate out as soon as possible has raised questions as to whether an inmate was ready to transfer out of the SIU.

Staff mentioned that in some cases they did not think an inmate was ready to be transferred out, mainly due to the inmates’ needs or risks not having been addressed, or continued safety and security concerns.

In these circumstances, staff reported that they would try to minimize the risks posed by these transfers by developing a risk management plan.

For example, taking preventative measures or finding a suitable alternative for the inmate.

Inmates’ refusal to transfer out

There are inmates who refuse to transfer out of the SIU, impacting average wait times for transfers.

A major factor impacting the amount of time between the decision to transfer out and the actual transfer was an inmate’s resistance to leave the SIU.

Based on the administrative data analyzed, close to 1 in 5 (18%) inmates refused to transfer out after an IH decision. In addition, refusals were more commonly cited by staff working at men’s institutions.

Average wait times substantially decreased when refusals were factored out of the calculation.

Text equivalent for Figure 13.

The image shows the average number of days between IH decision to actual transfer out for inmates who did not refuse transferring out. This is for inter-regional, intra-regional, and the same institution transfers. The Inter-regional, intra-regional, and same institution transfers are 4, 1, and 3 days, respectively.

Reasons for refusals

Reasons for inmate refusals to transfer out of the SIU were mainly due to safety concerns or preference for the SIU environment.

Staff interviewees identified several reasons for an inmate’s refusal to transfer out of the SIU.

Text equivalent for Figure 14.

The image shows the most cited reasons for inmate refusals (n= number of respondents). The most cited reasons include:

- fear for their safety (n=85)

- preferring the SIU environment (n=63)

- unwanted geographical relocation (n=28)

- unwanted transfer to a specific population (n=21)

- wanting to avoid incidents in the main population (n=18)

- waiting for a preferred alternative (n=18)

- waiting for a security reclassification (n=18)

Many inmates interviewed noted that while they wanted to transfer out of the SIU, they were waiting on a preferred option. For example, they wanted:

- security reclassification

- transfer to a specific population or institution; and

- transfer somewhere they would feel safe

In response to these challenges, efforts were made to encourage inmates to transfer out of the SIU.

Staff shared strategies used to get inmates to transfer out of the SIU. They include:

- encouraging and negotiating with inmates or addressing their concerns

- collaborating with other staff

- waiting until the inmate accepts a voluntary transfer; and

- involuntarily transferring the inmate (for example, using negotiators or the Emergency Response Team)

Staff also used creative strategies to ease inmates’ reintegration to a mainstream population, such as range visits or doing a gradual return to the range.

Overview of procedural safeguards

An overview of procedural safeguards is presented below.

- as outlined in CD 711, inmates are subject to various internal reviews and decisions throughout their time in the SIU. Internal reviewers and decision-makers include the SIU Review Committee (SIURC), the Institutional Head, the ADCCO, and the Senior Deputy Commissioner (SDC)

- pursuant to CD 711, after an inmate is approved for transfer to an SIU, the SIURC (normally chaired by the Deputy Warden and includes members of the inmate’s Case Management Team as applicable) will review each case pursuant to the required timeframes and provide recommendations to designated decision-makers. Following a review of the inmate’s case, the SIURC chairperson will meet with the inmate to advise them of the SIURC’s recommendation

- pursuant to CD 711, the Institutional Head is required to meet with the inmate prior to the Institutional Head reviews, which take place within 5 working days of the SIU authorization and within 30 calendar days from the date of the SIU authorization to transfer

- as outlined in CD 711, after a review or decision is rendered by a decision-maker, inmates are to be verbally advised within 1 working day and/or provided a written copy within 2 working days from the date of the review or decision

- pursuant to CD 711 and CSC Guideline 711-1, once a designated decision-maker has determined that an inmate no longer meets the legislative criteria to remain in the SIU, a decision is rendered to transfer the inmate out of the SIU and into the mainstream population as soon as possible

Further information regarding CSC SIU review timeframes can be found in CD 711.

Procedural safeguards

Comprehensiveness of Structured Intervention Unit Review Committee recommendations and Institutional Head reviews

When recommending whether an inmate should remain in the SIU, SIURCs were considering various alternatives and assessing the associated risks.

29% (499/1,724) of SIURC recommendations examined between April 2021 and March 2023 that were made prior to the IH 30-day SIU transfer decision recommended that the inmate be transferred out of the SIU.

78% (1,686/2,163) of inmates transferred out of the SIU after an SIURC recommendation to transfer out were successfulFootnote 10 in not returning to the SIU, a much higher percentage than that for SIU inmates overall. This suggests that their approach to considering alternatives and assessing risks when making recommendations is effective.

Most interviewees spoke to an efficient SIURC process with minimal delays, as decision-makers receive timely recommendations within the 20-day review deadline and generally regard this timeframe as appropriate. File review confirmed that SIURCs took place within the required timeframes for the sample selected.

IH reviews determining whether an inmate should remain in the SIU generally took place at the required interval and were completed by the appropriate authority. However, some information required by CSC Guidelines 711-1 was missing within the review documentation.

79% (53/67) of the IH 5-working day SIU transfer decisions analyzed did not have all required sections completed. Sections most commonly missing information included inmate representations including legal counsel/assistant, inmate engagement in opportunities for interaction with others, and inmate personal representation.

62.5% (30/48) of the IH 30-day SIU transfer decisions analyzed did not have all required sections completed. Sections most commonly missing information included inmate representations including legal counsel/assistant and gender identity/expression factors.

Outcome of Institutional Head reviews

In some instances, decision-makers believed that the legislative criteria was no longer met for an inmate to remain in the SIU.

The decision-maker believed that the legislative criteria was no longer met for the inmate to remain in the SIU:

- 27% (18/67) of the time for the IH 5-working day SIU transfer decisions reviewed

- 52% (25/48) of the time for the IH 30-day transfer decisions reviewed

- 40% (20/50) for the regional reviews reviewed

- 10% (3/31) of the time for the SDC decisions reviewed

- 31% (13/42) of the time for the non-ad-hoc SIURC recommendations reviewed