The Pen goes to War

Let's Talk > Read our stories > The Pen goes to War

The Pen goes to War

November 10, 2023

By: Cameron Willis, Curatorial Assistant, Canada's Penitentiary Museum

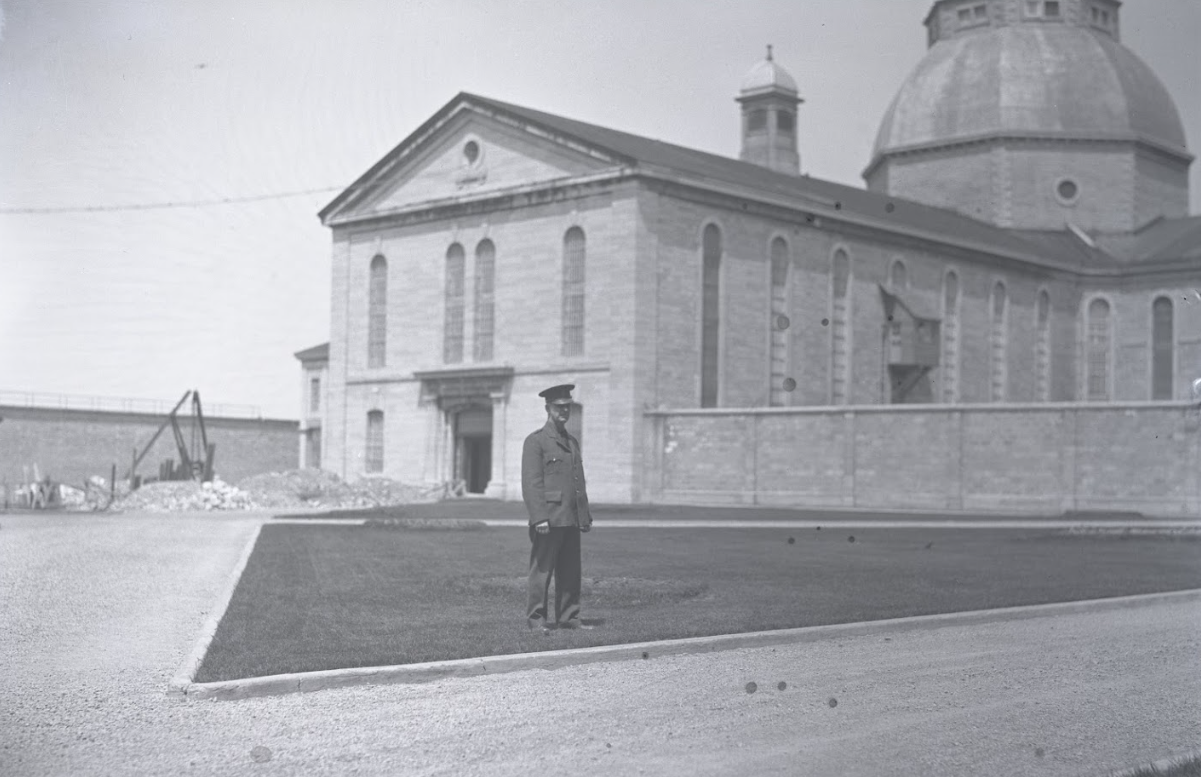

In the summer of 1943, the press reported on “the world behind the grey stone walls.” For the first time in a decade, journalists and photographers from major Canadian newspapers were allowed to visit three Dominion penitentiaries to find out what prisons were doing to assist the war effort.

The resulting newspaper coverage of activities in St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Laval, Quebec; Kingston Penitentiary in Kingston, Ontario: and the British Columbia Penitentiary in New Westminster, B.C., are an illuminating snapshot of a little-known part of the home front during World War II.

The newspaper coverage focussed on inmate production of supplies for military use or for other industries connected to the war. In the 1930s and 1940s, work was the primary method of rehabilitation. Anyone serving a sentence in a federal penitentiary was expected to do labour. Manufacturing in the penitentiaries was for internal use or for federal government departments. Mailbags, for instance, were manufactured or repaired for Canada Post by inmates.

When war broke out in 1939, guards (now called correctional officers) and instructors began to enlist to serve their country.

Production of supplies needed for the military increased. In 1941 and 1942, the Department of Defence and the Department of Supplies and Munitions awarded numerous contracts for war work to the penitentiaries.

Across Canada, inmates began making a variety of goods for military use. Prison farms increased their yields to provide pork, beef, eggs, and vegetables to domestic and overseas bases. When the journalists visited the penitentiaries in mid-1943, they observed the institutions in full swing in support of the Canadian war effort.

Mass production of military goods

James Dyer and Dave Bachan of the Vancouver Sun visited British Columbia Penitentiary in New Westminster in late June 1943. Their story, “Prisoners in B.C. Penitentiary Playing Large Part in War Work” appeared on July 3. Warden William Meighen was their prison tour guide. The reporters toured the prison workshops where inmates were repairing the metal frames of damaged army cots and hammering back together broken oilcans. A notable feature was a tailor shop, equipped with new electric sewing machines, making tens of thousands of pillowcases for the army. The reporters also noted a team of inmates was harvesting stray lumber from the Fraser River, left from logging drives. These old logs were chopped into firewood for Vancouver’s needy or repurposed for manufacturing.

Ernest Pallascio-Morin of the Montreal Photo-Journal and his photographer visited St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in Laval in early July. Their story, “L'aide précieuse des ‘hommes punis’,” appeared on July 15. They found the largest penitentiary in Canada abuzz with activity as inmates and staff worked towards “our national goal of defeating the Axis.” The reporter admired the “perfect order” and “impeccable organization” of the penitentiary, witnessing shift changes, lunchtime, and the exercise period firsthand.

The machine shop inmates were producing slings for Bren guns and aiming posts, while the carpentry shop turned out everything from folding tables to clipboards for military field use. The most unique workshop, according to Pallascio-Morin, was producing camouflage nets for the army. Fifty inmates made the nets under the supervision of a staff instructor and a corporal seconded from the Department of Defence. Between 1941 and 1943, the workshop turned out tens of thousands of nets destined for battlefields in Europe.

Valuable war work

The Montreal journalists concluded that this war work was valuable. It provided supplies directly to the military. It also provided practical training and skills for released inmates likely to seek employment in war industries.

The article concluded ironically that without the work of men behind bars, “our country cannot be free.”

Reporters from the Toronto Star visited Kingston Penitentiary that August. In his story, “The Pen Goes to War,” journalist Ross Harkness commented on the volume of war production. Inmates were making huge quantities of brooms, navy hammocks, military cots, tents, and leather coats for the merchant marine. Carpenters also built furniture for the families of Royal Canadian Air Force crews stationed in the Kingston area. Thousands of mailbags were made to help with the increase in mail being sent overseas and to replace bags lost aboard ships sunk by the enemy.

Warden R. M. Allan felt that the chief benefit of the penitentiaries during World War II was that their smaller, more generalist workshops could pivot into production items that other firms found too limited in scale or too costly. The Kingston Pen machinist instructor, Ernest Dunford, told Harkness he believed his electric welding course was a valuable contribution. It taught welding skills to short term inmates who, once released, went to work in shipyards and other production plants. Harkness noted the inmates he spoke to were generally pleased about helping the war cause.

Other institutions, not featured in the press, also made major contributions to the war effort. At Collin’s Bay Penitentiary in Ontario, inmates operated a dyeing plant that converted old military coats into uniforms for prisoner of war camps across Canada. Dorchester Penitentiary employed almost a third of its inmates making or repairing military boots for Canada’s allies. Similar war work was going on at the Saskatchewan and Manitoba Penitentiaries.

The Star, the Ottawa Journal, and Kingston Whig-Standard all reported on the monthly Red Cross blood drives. Half of the prisoners at Kingston Pen (400 out of 775) gave blood to meet battlefield and emergency needs. By late 1942, younger incarcerated men could enroll in correspondence courses on aviation and machine mechanics in preparation for their release.

There were definite challenges during the war, though. Guards interviewed by the reporters noted that some of the skills being taught, like welding, were very useful not just in securing jobs but in committing crimes. A keeper at Kingston Penitentiary told the Ottawa Journal on July 24, 1943, that not all inmates were enthusiastic about their contributions. After all, he said, “nobody invited them to work here!”

Demands of war work

All penitentiaries experienced serious staffing shortages as the war went on. Many officers enlisted to serve overseas, and replacements were hard to find. As a result, there was an increase in escapes, or attempted escapes, and even small inmate disturbances occurred in some of the penitentiaries.

The pressing need for military supplies meant that both staff and inmates were working long hours, doing double shifts, and had less time off. At St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary, the prison surgeon implemented a strict eight-hour shift in 1943 to preserve guard health. Inmates could not collect overtime pay, so a number of institutions introduced extra tobacco rations, radio broadcasts, and brought in bands as rewards.

The Dominion Penitentiaries made a valuable contribution to the war effort. Acting Superintendent of Penitentiaries G. L. Sauvant reported in March 1945 that more than 1,446,000 articles were manufactured.

For the first time, the Dominion Penitentiaries had operated a national industrial program. This paved the way for future industrial and training programs operating today in Correctional Service Canada’s Institutions.

The veterans who returned and rejoined or signed up for penitentiary service would form the core group of officers who would guide the federal penitentiaries through great changes in the 1950s and 1960s.

Canada’s Penitentiary Museum is an award-winning museum in Kingston, Ontario. It is dedicated solely to the preservation and interpretation of the history of our federal penitentiaries.

Page details

- Date modified: