Hope behind the wire: Why Keagan Cockerill shows up every day

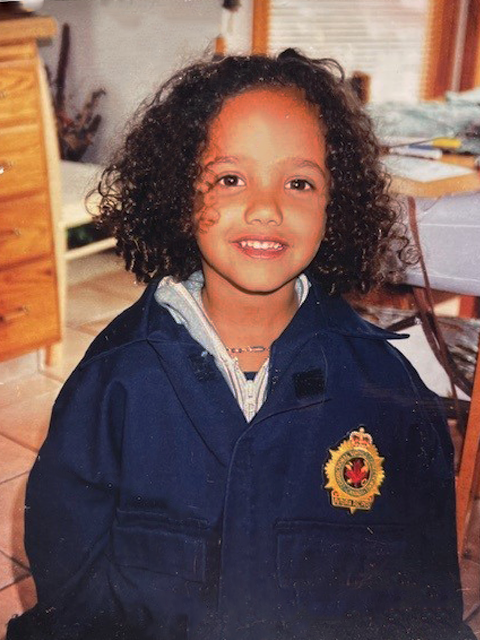

As a little girl growing up in Saskatoon, Keagan Cockerill would sit at the kitchen table while her mother studied for criminology exams. “I was only four years old, but I would quiz her on the terms, and I picked up words most kids my age wouldn’t know,” she says with a laugh. “We’ve always been so close. My mom has always been my biggest inspiration.”

As her mother began her career as a correctional officer, she would often remind Keagan that behind the walls and wire were human beings who are flawed, complicated, and still capable of kindness. “There’s such a misconception that federally sentenced people are nothing like us,” Keagan reflects. “But my mom would share stories of offenders who would look out for her or quietly warn her if something felt off. That humanity stuck with me.”

It also planted the seed for what she would discover was her calling as a parole officer. At university, Keagan immersed herself in sociology, psychology, and criminology, seeking out practicums that took her into healing lodges and psychiatric centres. Her passion was advocacy, particularly for those who had been overlooked or misunderstood.

At just 22, she became a residential caseworker at the John Howard Society of Saskatchewan, working with male youth at risk. Many were only a few years younger than her. “I was like a den mother, but also a big sister,” she remembers. “We had dinner on the table every night. I showed up to parent, teacher meetings. I took them to sport events, and I created a non-judgmental space for them to talk.”

Those years taught her the transformative power of trust, consistency, and compassion. It also showed her how, as a Black woman, lived experience matters.

“I definitely always operate with a culturally competent lens,” she says. “Representation matters, and it makes a difference when someone doesn’t have to explain who they are and what their cultural expression is before being understood.”

Today, Keagan is a parole officer with the Toronto Women’s Supervision Unit, where she currently supervises 19 women on conditional release. Her work is dynamic, sometimes meeting in the office, at a client’s home or workplace, and other times sharing coffee and conversation on a park bench. “One of my clients joked that our check-ins felt like therapy,” Keagan says with a smile. “And in a way, sometimes they do.”

The success of her clients’ journeys is relative. It might look like a woman who stays sober for a month after years of relapse. Or a client who, against all odds, begins rebuilding a life with her family, shopping for chicken at the supermarket and making dinner at home. “It’s about meeting them where they’re at,” she says. “You can’t hold everyone to the same measuring stick.”

Some of the most moving moments have come when clients express their gratitude. A woman finishing her sentence might hand her a letter, thanking her for believing in her when no one else did. Another may drop by the office months later, just to say hi. “Those are the tear-jerker moments,” Keagan admits. “Those are the moments that remind you why this work matters.”

She’s also helping to create new traditions of hope. Her unit recently launched a Star of the Month program, recognizing women for milestones like sobriety, employment, or volunteering. While the laminated certificates they hand out may be simple, the impact isn’t. “Many of these women have gone their whole lives without being recognized for their accomplishments,” she says. “To see them cry tears of joy or proudly hang their certificate in their living room is so powerful.”

Keagan dreams big, too. A lifelong dancer, she envisions one day creating a hip hop dance program for federally sentenced women. “Dance was always an outlet for me, it builds resilience, confidence, self, expression,” she says. “I know it could be the same for them.” She’s already tested the waters by performing at an ethnocultural day inside an institution.

“I can’t say that performing a dance solo in front of several women I’ve supervised wasn’t nerve wracking, but their unwavering cheering, support, and genuine appreciation made it all worth it,” she says. “It was a moment of unity, no barriers, just people connecting.”

But for all her vision and drive, Keagan never forgets the heart of the work: walking alongside people, not above them. It’s that balance, firm but fair, compassionate yet accountable, that guides her.

“You empower, you hold accountable, you walk with them for a time, and then you let them go,” she says. “The hope is that they carry the tools to stop harming themselves and others.”

She also makes sure to practice what she preaches. “Self-care is everything,” she notes. “I love fitness classes, and I’ve learned to tell my friends, ‘I don’t have the bandwidth today,’ if I’ve had a really heavy week. You can’t show up for others if you don’t take care of yourself.”

For Keagan, parole work isn’t about control or authority; it’s about humanity, possibility, and the quiet victories that ripple out far beyond what anyone can see. “I absolutely love coming to work every day,” she says. “Even on the hard days, there are always glimmers of progress. And that’s enough to keep me going.”