Restorative Justice in the Canadian Criminal Justice Sector

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Key Findings

- 3.0 Data Analysis

- 3.1 Types of RJ Programs and Services

- 3.2 Types of RJ Models Used

- 3.3 Number of Criminal Cases Referred

- 3.4 Information Collected by FPT Ministries about RJ

- 3.5 Challenges with Data Collection

- 3.6 Priorities for Research and Evaluation

- 3.7 Training

- 3.8 Procedures, Policies or Protocols on the Use of RJ

- 3.9 Other RJ Activities

- 3.10 Other Comments

- 4.0 Final Thoughts

- References

Charts and Graphics

- Graphic 1: A Continuum of Restorative Responses

- Chart 1: Number of Programs Funded or Supported by FPT Ministries

- Chart 2: Number and Type of Referrals in 2009/10

- Chart 3: Definitions and Understandings of Key Terms

- Chart 4: Types of RJ Research Conducted by FPT Ministries, 2000-2010

- Chart 5: Percentage of Topics that Received a Top 3 Rating

- Chart 6: Average Rating of Research Priorities

April 27, 2016

Executive Summary

This report presents a "snapshot" of restorative justice (RJ) in programs that are funded, supported or provided by federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) governments in the criminal justice sector. It is intended to help RJ practitioners, volunteers, academics, policy makers, criminal justice officials, and others understand the extent to which RJ is being used across Canada.

Before preparing this report, the FPT Working Group on Restorative Justice took a major step toward measuring the use of RJ by achieving consensus about a definition of RJ in the criminal justice sector, which is, "An approach to justice that focuses on addressing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for his or her actions, by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by crime - victim(s), offender and community - to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime." RJ supports healing, reintegration, the prevention of future harm, and reparation, if possible.Footnote 1

The Working Group developed a survey that focused on RJ programs funded, supported or provided by FPT ministries responsible for justice and public safety, using 2009/10 as the baseline year. The resulting data includes information from 19 ministries in 12 FPT jurisdictions. Two jurisdictions, Québec and Prince Edward Island, chose to opt out of the survey. While the resulting data is not completely comprehensive, this report is helpful in understanding the use of RJ in much of Canada at a particular point in time.

Some key findings are outlined below. The number of responses varied, as not every FPT ministry chose to answer every question.

- There was great variety regarding the kinds of RJ programs funded, supported or provided by FPT jurisdictions in the criminal justice sector. Thirteen ministries indicated that they funded or supported Aboriginal justice/community justice programs; four funded or supported community justice committees/youth justice committees that fell under the definition of RJ used in the survey; nine funded or supported community-based non-profit organizations in the criminal justice sector that are involved in RJ; and three supported other kinds of community-based organizations or service delivery models related to RJ. Additionally, five ministries indicated that government employees provided direct RJ services such as facilitation and victim-offender mediation.

- Thirteen ministries funded or supported over 400 RJ programs in the criminal justice sector in 2009/10. This included 170 Aboriginal justice/community justice programs; 117 community justice/youth justice committees; and 116 community-based non-profit organizations. Additionally, eight other RJ programs or services were funded or supported, for a total of 411.

- In 2009/10, about 34,000 adult and youth criminal matters were facilitated with RJ in Canada. This includes at least 21,500 youth referrals and 12,200 adult referrals. These figures include pre-charge, post-charge and post-sentencing referrals, but exclude Québec and Prince Edward Island.

- Conferences, victim-offender mediation and circles were the most commonly used RJ models. Most of the FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey (94% of respondents) indicated that RJ programs used these kinds of models.

- About four-fifths of FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey collected some kind of data on RJ. This data primarily regarded matters such as the number of cases or referrals, characteristics of the offence and the outcome of the restorative process. There was a fair amount of variability regarding definitions of terms such as "case" or "referral".

- Just over half of FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey had conducted research or evaluation on RJ between 2000 and 2010. FPT ministries were also asked what topics would be their priorities for research and evaluation if resources were available. Four-fifths of respondents who answered this question indicated that the impact of RJ on victims, offenders, and communities would be a top priority.

- Most ministries that participated in the survey had policies, procedures or protocols regarding matters such as referring and facilitating cases and the structure and administration of RJ programs.

- Virtually all of the ministries that participated in the survey had offered some kind of training related to RJ, but not many provided this training on an ongoing basis. Existing training covered a wide range of topics such as basic concepts of RJ; how the criminal justice system works; the practice of RJ; government policies, procedures and legislation; and operating RJ programs.

The results suggest that there is a need for additional data collection and evaluation about RJ in the Canadian criminal justice sector. While coming to consensus about a definition of RJ was a major step forward, it would be necessary to continue working on common definitions, data indicators and collection methods. Most of the FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey indicated that they would be interested in discussing some kind of future data collection exercise, and the FPT Working Group on RJ is considering updating this report to determine how the use of RJ in the criminal justice sector has changed since 2009/10. In the meantime, this information is helpful in beginning to understand the extent to which RJ is used in Canada.

1.0 Introduction

This report presents a "snapshot" of restorative justice (RJ) in programs that are funded, supported or provided by federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) governments in the criminal justice sector. It is intended to help RJ practitioners, volunteers, academics, policy makers, criminal justice officials, and others understand the extent to which RJ is being used across Canada.

Restorative justice (RJ) in the criminal justice sector is, "An approach to justice that focuses on addressing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for his or her actions, by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by crime - victim(s), offender and community - to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime." It supports healing, reintegration, the prevention of future harm, and reparation, if possible.Footnote 2

This report presents data gathered by the FPT Working Group on RJ, which is comprised of officials from FPT ministries and departments that are responsible for justice and public safety. The Working Group's mandate is to consider and coordinate discussion on administrative, policy and evaluation issues that emerge from the implementation of RJ and related alternative criminal justice programs. The Working Group enables criminal justice policy makers and program administrators to discuss RJ policy and share information about procedural issues, policy issues and program implementation.

The Working Group developed and circulated a survey on RJ programs funded, supported or provided by FPT ministries in the criminal justice sector. The survey was completed in 2012, and used 2009/10 data for matters such as the number of RJ programs and referrals.

The resulting data includes information from 19 ministries in 12 jurisdictions. Two FPT jurisdictions, Québec and Prince Edward Island, chose to opt out of the survey. While the resulting data is not completely comprehensive, this report is helpful in understanding the use of RJ in much of Canada at a particular point in time. Future surveys and reports may enable the Working Group to determine how RJ has changed in the Canadian criminal justice sector since 2009/10.

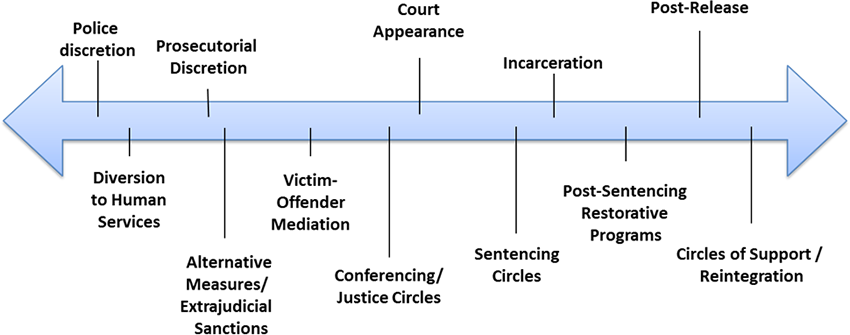

The use of RJ has been growing rapidly over the past four decades and there is some RJ activity in every jurisdiction, although it is not necessarily funded by FPT governments.Footnote 3 The vast majority of criminal matters that are facilitated with RJ processes in Canada are referred at the pre-charge and post-charge stage through adult alternative measures and youth extrajudicial sanctions.Footnote 4 There are also some RJ programs that handle serious violent offences at the pre-sentencing, post-sentencing and reintegration phases. Graphic 1 depicts how RJ can be used across the entire justice continuum from the point at which a crime becomes known to the police to the time that an offender is released into the community:

Graphic 1: A Continuum of Restorative Responses

Justice System Processes

Justice System Processes

This graphic depicts how RJ can be used in different formats at different points across the entire criminal justice process from diversion to human services by police at the pre-charge stage to the use of circles of support at post-release.

Restorative Justice Opportunities

FPT jurisdictions that support RJ in the criminal justice sector usually do so by providing funding to community-based agencies, Indigenous organizations, or other groups. As will be further discussed, some FPT jurisdictions also have government employees who provide direct RJ services, and many provide other kinds of support to RJ programs.

While this document is intended to provide a "snapshot" of RJ programs that were funded, supported or provided by FPT jurisdictions at a particular point in time, it does not attempt to reflect the entire picture of RJ in Canada. Many RJ programs are offered by groups or organizations that do not receive FPT funding, and the use of RJ is growing in areas outside the criminal justice system such as education, child protection, human rights and environmental or regulatory matters.Footnote 5 There is a need for research about the extent to which RJ is occurring in these areas.

1.1 Background

FPT jurisdictions have been interested in collecting data about RJ for many years. In 2002, the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (CCJS) attempted to determine whether it would be feasible to undertake a study on RJ in the criminal justice sector. CCJS gathered information from FPT jurisdictions about their definitions of RJ and other matters, and concluded it would be difficult to undertake a national study until there was more agreement on a definition.

In 2007, the Working Group decided to see whether enough progress could be made on definitions to make data collection possible. The Working Group reviewed national and international literature and considered the benefits and limitations of various definitions. While it was challenging to develop a definition that reflected the various ways RJ is understood and practiced across the country, by 2009 the Working Group achieved consensus on the following, which is adapted from Robert Cormier's 2002 report, "Restorative Justice: Directions and Principles - Developments in Canada":

Restorative justice is an approach to justice that focuses on addressing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for his or her actions, by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by crime - victim(s), offender and community - to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime.Footnote 6

Coming to consensus about the definition was a significant step toward being able to measure the use of RJ in the criminal justice sector by enabling the Working Group to develop a survey and gather data from FPT jurisdictions. For more information about the survey and data analysis, please see the Methodology section of this report.

1.2 Rationale for the Survey

Members of the FPT Working Group periodically receive requests for information from RJ practitioners, academics, members of the public, and the media, but there are few sources of information about the extent to which RJ is used in Canada. For example, Umbreit et al. published an article in 1995 about mediation in four provinces, the Church Council on Justice and Corrections produced a compendium of RJ programs in 1996, and the Correctional Service of Canada has produced inventories of RJ programs for National RJ Week, but there is currently no comprehensive way to identify the number of RJ programs across the country or the number of cases being facilitated with RJ.

Progress on data collection is vital to:

- Develop benchmarks for program evaluation. While there have been some important studies about RJ as well as evaluations of individual programs, this is the first effort by FPT jurisdictions to collect this kind of data systematically, and the resulting information could help develop benchmarks for program evaluation.

- Document promising practices. There is increasing attention nationally and internationally to the development of evidence-based RJ practices. Research and evaluation will be required to test the "promising practices" suggested by RJ agencies.

- Respond to requests from practitioners, the public, academics, the media, policy makers and criminal justice officials for information about the use of RJ.

- Determine whether it might be possible to have a national data collection exercise in the future.

1.3 Methodology

After the Working Group came to consensus about a definition of RJ in the Canadian criminal justice sector, the CCJS assisted with developing a survey to gather baseline information about the number of RJ programs funded or provided by FPT jurisdictions, the number of criminal cases facilitated with RJ, and other matters.

A draft of the survey was circulated to FPT jurisdictions and revised to reflect their feedback. When the survey was finalized, it was sent to FPT ministries or departments responsible for justice and public safety. Throughout this report, the terms "ministries" and "departments" are used interchangeably.

FPT departments were asked to provide information about RJ programs or services they funded, directly provided through the work of their employees, or supported in other ways, such as in-kind assistance or advice to RJ programs.

The data was compiled and analyzed by Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice with the help of a subcommittee that included officials from Alberta, CCJS, Correctional Service of Canada, Justice Canada - Policy Centre for Victim Issues, Nova Scotia, Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Saskatchewan and Yukon. The Working Group thanks all of the subcommittee members for their help and advice.

By July 2012, responses were received from 19 ministries or departments in 12 FPT jurisdictions. This includes responses from the following ministries or departments (as they were called at that time):

- Alberta Solicitor General and Public Security

- British Columbia Attorney General

- British Columbia Public Safety and Solicitor General

- British Columbia Children and Family Development

- Manitoba Justice

- New Brunswick Public Safety

- Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Justice

- Northwest Territories Department of Justice

- Nova Scotia Department of Justice

- Nunavut Department of Justice

- Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services

- Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice and Attorney General

- Saskatchewan Corrections, Public Safety and Policing

- Yukon Health and Social Services

- Yukon Justice

- Federal: Correctional Service of Canada

- Federal: Justice Canada

- Federal: Policy Centre for Victim Issues

- Federal: Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Prince Edward Island decided to opt out of the survey, due to a lack of ministry capacity to participate. Provincial officials noted that the province supports the Mi'Kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island's Aboriginal Justice Program, which is a comprehensive, province-wide approach co-funded under the federal Aboriginal Justice Strategy. Québec chose to opt out because the ministry that supports RJ programs is not a member of the FPT Working Group on RJ.

1.4 Challenges in Developing and Implementing this Survey

FPT ministries were asked to self-identify whether the programs and services they funded, supported or provided fell under the definition of RJ agreed to by the Working Group. This approach reflects the flexible nature of RJ and the variation that exists in how it is understood and practiced. The challenge with this approach is that it does not reflect all RJ activity. Instead, this report presents a "snapshot" of RJ in much of Canada at a particular point in time.

While the Working Group was interested in gathering wide-ranging data on all aspects of RJ, limitations on the amount of staff time that could be devoted to this project made it necessary to focus on a smaller, more manageable amount of data. For this reason, the Working Group agreed that this initial effort would focus on RJ in the criminal justice sector. In the longer term, the Working Group is interested in gathering more extensive data about RJ in communities and other sectors such as the education, child protection and regulatory systems.

2.0 Key Findings

The survey resulted in the following key findings. For additional information about each topic, please see section 3. It should be noted that the number of responses varied, as not every ministry chose to answer every question in the survey.

- There was great variety regarding the kinds of RJ programs funded, supported or provided by FPT jurisdictions in the criminal justice sector. Thirteen ministries indicated that that they funded Aboriginal justice/community justice programs; four funded or supported community justice committees/youth justice committees that fell under the definition of RJ used in the surveyFootnote 7; nine funded or supported community-based non-profit organizations that were involved in RJ in the criminal justice sector; and three supported other kinds of community-based organizations or other service delivery models. Additionally, five ministries indicated that government employees provided direct RJ services such as facilitation, victim-offender mediation and youth centres that focused on RJ principles.

- Thirteen ministries funded or supported over 400 RJ programs in the criminal justice sector in 2009/10. FPT ministries were asked how many community-based programs, organizations or groups they funded or supported that were involved in RJ. The 13 ministries that responded to this question funded or supported 411 RJ programs in the criminal justice sector. This included 170 Aboriginal justice/community justice programs; 117 community justice/youth justice committees that fell under the definition of RJ used in the survey; and 116 community-based non-profit organizations involved in RJ work. Additionally, there were eight other RJ programs or services funded or supported, for a total of 411.

- In 2009/10, about 34,000 adult and youth criminal matters were facilitated with RJ in Canada. This included at least 21,500 youth referrals and 12,200 adult referrals. Ministries were asked how many criminal referrals or cases were facilitated in 2009/10 by the RJ programs they funded, supported or provided. The answers provided a limited amount of data that gives a rough approximation of the number of referrals and cases. The available data suggests that there were at least 21,504 youth referrals and 12,277 adult referrals, for a total of 33,781. These figures include pre-charge, post-charge and post-sentencing referrals, but exclude Québec and Prince Edward Island.

- Conferences, victim-offender mediation, and circles were the most commonly used RJ services. Most of the jurisdictions that participated in the survey (94% of respondents) indicated that RJ programs use various kinds of conferences, including family group conferences, community justice conferences, and community justice forums; victim-offender mediation; various kinds of circles, particularly healing circles; and accountability conferences. The next most commonly provided services (at 78% each) included training and alternative measures/extrajudicial sanctions programs that operate with RJ principles or processes. For more information about these terms and the extent to which they are used, please see section 3 of this report.

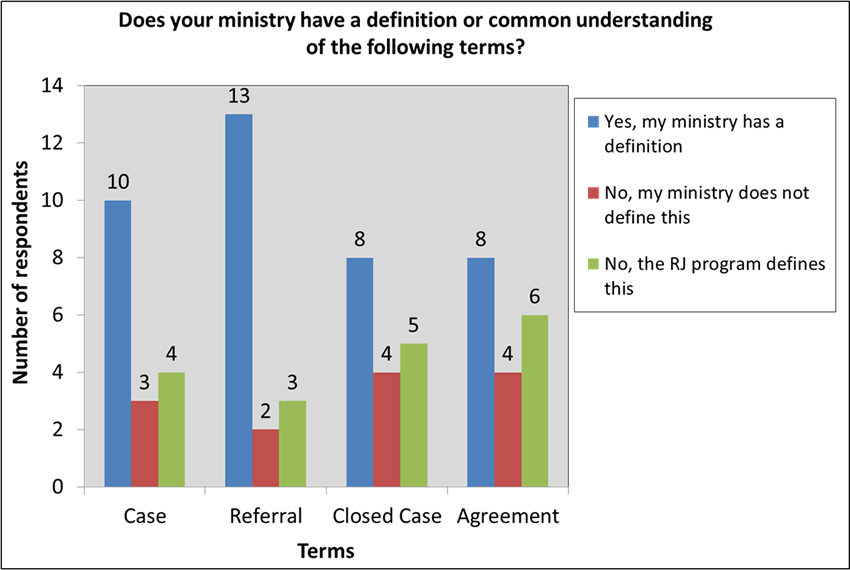

- About four-fifths of FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey collected some kind of data on RJ. For example, about 80% collected information on the number of RJ cases or referrals. There was a significant amount of variation in regards to the other kinds of data collected, with around 70% of respondents saying their jurisdiction collected information about matters such as the characteristics of the offence and the outcome of the restorative process. The data also indicated that there was a fair amount of variability regarding definitions of terms such as "case" or "referral".

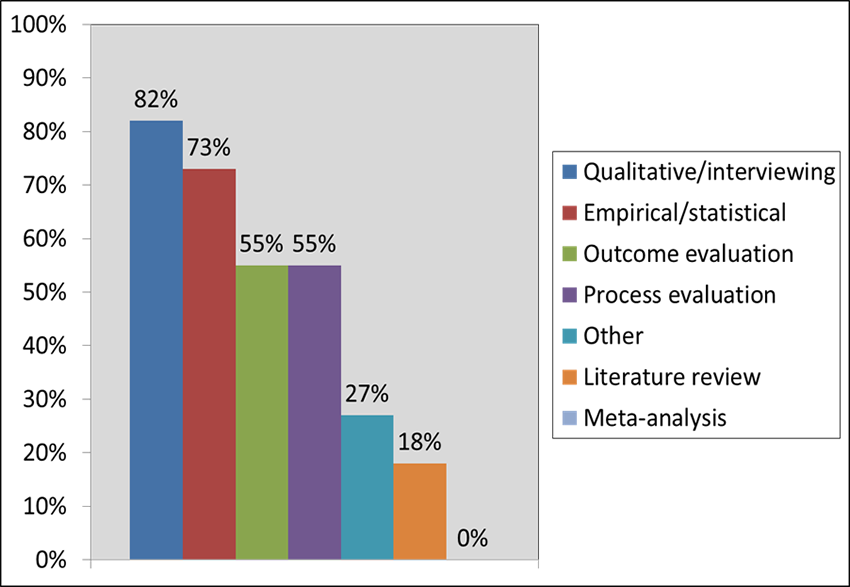

Sixty-five percent (65%) of the ministries that responded had a database to record information about RJ. Several respondents indicated that the lack of ministry capacity to collect and analyze the data was the biggest challenge they faced regarding data collection. Other commonly mentioned challenges included lack of community capacity to provide the data, technological issues regarding data collection, and concerns about privacy. - Just over half of FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey had conducted research or evaluation on RJ between 2000 and 2010. Ten of the 18 respondents (56%) who answered this question said that their ministries had done so. Most of the research or evaluation that was conducted involved empirical/statistical methods (73%) and qualitative/interviewing methods (82%).

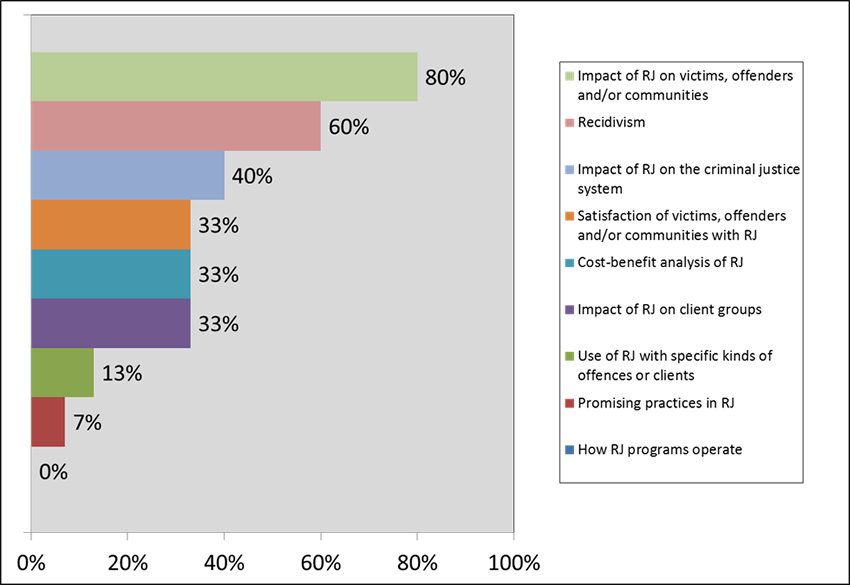

Ministries were also asked what topics would be their priorities for research and evaluation on RJ if resources were available. Four-fifths of respondents who answered this question (80%) indicated that the impact of RJ on victims, offenders, and communities would be the top priority. Topics such as cost-benefits analysis; the impact of RJ on the criminal justice system; the satisfaction of victims, offenders and community members with RJ; and the impact of RJ on recidivism also received high ratings as priorities for research and evaluation. - Most ministries that participated in the survey had procedures, policies or protocols for matters such as referring and facilitating cases and the structure and administration of RJ programs.

- Virtually all of the ministries that participated in the survey had offered some kind of training related to RJ, but not many provided this training on an ongoing basis. Existing training covered a wide range of topics such as basic concepts of RJ; information about how the criminal justice system works; the practice of RJ; government policies, procedures and legislation; and managing and operating RJ programs. Depending on the jurisdiction and the topic, the training was offered to community-based RJ practitioners and volunteers, justice officials such as police and Crown prosecutors, government employees and others.

3.0 Data Analysis

This section analyzes the data and provides additional information about questions in the survey and how FPT departments responded.

3.1 Types of RJ Programs and Services

As previously discussed, FPT ministries were asked to provide information about the number of RJ programs they funded, supported or provided in the criminal justice sector. The results indicated that:

- Thirteen ministries funded, supported or provided Aboriginal justice/community justice programs.

- Four ministries funded, supported or provided community justice committees or youth justice committees that fell under the definition of RJ provided for this survey.

- Nine ministries funded or supported community-based non-profit organizations that were involved in RJ work in the criminal justice sector.

- Three ministries supported other kinds of community-based organizations, groups or service delivery models, such as a RJ centre and a centre for comparative criminology.

- Eight ministries had programs that were co-funded by other FPT ministries and governments.

Additionally, five ministries indicated that they provided direct RJ services such as having employees facilitate cases, conduct victim-offender mediations or conferences, and operate youth centres that focused on RJ principles and processes.

Ministries were asked how many community-based RJ programs in the criminal justice sector they funded or supported between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2010. Chart 1 indicates that there were 411 RJ programs funded or supported by the 13 ministries which responded to the question.

Chart 1: Number of Programs Funded or Supported by FPT Ministries

| Type of Community-based Program, Organization or Group: | Total Number of Programs Funded or Supported: |

|---|---|

| Aboriginal justice program/community justice program | 170 |

| Community justice committee/youth justice committee that fell under the definition of RJ used in the survey | 117 |

| Community-based non-profit organization | 116 |

| Other kind of community-based organization, group, or service delivery model | 8 |

| Total | 411 |

When asked what kinds of RJ services were funded, supported or provided, most respondents (94%) indicated that the RJ programs used the models described in section 3.2. The next most commonly provided services (at 78% each) included training and alternative measures/extrajudicial sanctions programs that operated with restorative principles or processes. Many RJ programs also offered referrals to other kinds of services; conducted public education on RJ, Aboriginal justice, or other topics; and provided crime prevention services (at 72% each). Additionally, a few respondents indicated that RJ programs in their jurisdiction offered other services such as fine option programs, community service work, traditional Aboriginal activities, special school programs, senior safety programs and facilitation for groups experiencing conflict.

3.2 Types of RJ Models Used

Just as there is variation in how RJ is understood and practiced across Canada, there are differences in how terms such as "conferences", "victim-offender mediation" and "circles" are understood and implemented. With this caution in mind, the information provided for this survey suggested that conferences are the most commonly used model within RJ programs that are funded, supported or provided by FPT ministries in the criminal justice sector. All of the 17 respondents who answered this question indicated that RJ programs in their jurisdiction used various kinds of conferences, such as community justice forums (a model that may be facilitated by a police officer and often involves a script), community justice conferences with adults, and family group conferences with children, youth, family members or other supportive adults.

Victim-offender mediation was the next most commonly used model (88%), followed by healing circles (76%), in which the victim and his or her friends, families, professionals and others meet to discuss the impact of the crime on the victim, how to support the victim and address the harm caused to the extent possible. Other kinds of circles were used less frequently. These included sentencing circles, which provide advice to a judge about an appropriate sentence; Circles of Support and Accountability, in which community members provide assistance to offenders who have been released following a term of incarceration while holding the offender accountable for living peacefully and safely in the community; and peacemaking circles that involve the victim, the offender, their friends and families, community members and others in resolving crime and conflict.

The next most commonly used model was accountability conferences (71%), in which the RJ facilitator meets with the offender to discuss the causes and impact of the offender's behavior and what he or she can do to make amends.

Three respondents indicated that RJ programs used other models such as "on the land programs." The respondent did not provide any information about what an "on the land program" is.

3.3 Number of Criminal Cases Referred

Ministries were asked how many criminal referrals or cases were handled in 2009/10 by RJ programs they funded, supported or provided. Some jurisdictions did not have the capacity to record RJ-related statistics and others used different terms or methods for collecting this information, which makes it difficult to compare data. As five respondents did not answer this question or commented that the information was unavailable, the responses provide a limited amount of data that give a rough approximation of the number of criminal referrals and cases across much of Canada.

With these cautions in mind, Chart 2 shows the type and number of referrals that were facilitated with RJ in 2009/10. The number in the brackets indicates the number of ministries that answered this question. Two respondents could only provide a total number of cases or referrals for youth and adults as an aggregated sum and were unable to break it down in terms of the number of pre-charge, post-charge or post-sentence matters, and there were other cases or referrals in which the respondents were unsure of the stage at which the matter was referred. Therefore, the pre-charge, post-charge and post-sentence categories do not add up to the total number of referrals/cases.

Chart 2: Number and Type of Referrals in 2009/10

| Pre-charge | Post-charge | Post-sentence | Subtotal - Point of Referral Known | Point of Referral UnknownFootnote 8 | Total Number of Referrals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | 2,447(5) | 643(3) | 23 (2) | 3,113 (10) | 18,391 | 21,504 |

| Adult | 3,792 (4) | 2,102 (3) | 345 (2) | 6,239 (9) | 6,038 | 12,277 |

3.4 Information Collected by FPT Ministries about RJ

Fifty-nine percent (59%) of respondents indicated that their ministries had reporting forms to collect information about various aspects of RJ, and 65% said they had a database to gather this information.

About 80% of jurisdictions collected information on the number of RJ cases or referrals. There was a significant amount of variation in regards to the other kinds of data collected, with around 65% of respondents saying their jurisdiction collected information about matters such as characteristics of the offender and the type of RJ model used. About 70% collected information on the characteristics of the offence and outcome of the referral or case, such as whether an agreement was reached between the victim and the offender, whether the agreement was fulfilled, and the steps taken by the offender to repair the harm done to the extent possible. Thirty-seven percent (37%) of respondents said their jurisdiction collected information about the characteristics of the victim, and three respondents commented that their jurisdictions did not collect any information about RJ programs.

As illustrated in Chart 3 below, there was a fair amount of variability in regards to defining terms such as "case", "referral", "closed case", and the "agreement" about how to resolve the referral or case. For example, about half of the 18 respondents indicated that their ministry had a definition or common understanding about the term "case", while three indicated that their ministry did not and the remaining respondents indicated that they left it up to restorative programs to self-define these terms. Some of the definitions that were provided for a "case" included:

A case is an offender, charge(s) and a victim. If there is more than one victim, that is more than one case.

A case is a referral that is made to an agency. It may be more than one set of charges.

One ministry indicated that they do not use "case" as a definition and that the statistics they record are "based upon people referred". Another ministry reported that they have three different types of referrals.

Chart 3: Definitions and Understandings of Key Terms

Chart 3: Definitions and Understandings of Key Terms

This bar chart shows how many ministries define the following terms: case, referral, closed case, and agreement. Most ministries do define these terms. In some cases, it is the RJ program that defines the term. In each case, there are only 4 or less jurisdictions where these terms are not defined.

Survey participants were also asked if there were any other definitions their ministry used to identify or measure RJ activities. Responses included: restorative justice, victim-offender mediation, conference, accountability conference, victim offender resolution conference, community justice forum, community justice conference, family group conference and non-diversion activities.

3.5 Challenges with Data Collection

Respondents indicated that many challenges affected their ministries' ability to collect data on government-funded RJ programs in the criminal justice sector. The most common response was lack of ministry capacity to collect and analyze the data (67% of respondents who answered this question cited this as a challenge). Lack of community capacity to provide the data was mentioned by 44% of respondents. Technological issues (39%), privacy issues (22%) and other issues (39%) were also mentioned.

Technological issues included uncertainty about the quality of data provided by community-based RJ agencies and challenges related to having multiple data systems, old systems that needed to be updated, or difficulties with collecting or entering historic data. One respondent commented that his or her data management system was designed to collect information about clients rather than to capture information specifically about RJ.

All of the respondents who reported that their ministries experienced privacy issues regarding RJ said that the challenges related to legislation and policies about protection of personal information and the circumstances under which personal information could be disclosed.

Some of the other challenges mentioned included consistency in data collection and data entry, the need for training regarding data collection, and lack of infrastructure within communities to gather data. For example, one respondent wrote:

Using the community-based model for service delivery makes collecting consistent data a challenge. It is important to have common definitions and educate the programs about the importance of reliable, valid data to their program.

Additionally, one survey respondent suggested that there were many RJ activities that were not captured by current data systems in his or her jurisdiction.

3.6 Priorities for Research and Evaluation

The Working Group wanted to get a sense of how much research, evaluation and data collection regarding RJ had been undertaken by FPT ministries in the criminal justice sector. Just over half of the 18 respondents who answered this question (n=10, or 56%) indicated that their ministries had conducted, funded or supported this kind of research, evaluation or data collection between 2000 and 2010. About one quarter of respondents indicated that their ministry had not done so, and 17% were uncertain.

Of those respondents who indicated that their ministry had undertaken, funded or supported research or evaluation on RJ, 11 described the type of research or evaluation conducted. Most of the research or evaluation involved qualitative/interviewing methods (82%) or empirical/statistical methods (73%). Process evaluations and outcome evaluations were fairly common (55% each). Only two respondents (18%) indicated that their ministries had conducted literature reviews, and three (27%) mentioned other kinds of research or evaluation, such as collecting anecdotal stories, distributing questionnaires, and conducting site visits to RJ programs. Additionally, many respondents indicated that they had used multiple methodologies. The meta-analysis conducted by Justice Canada in 2001 was not reported, possibly because the respondent who completed the survey was unaware of it.

Chart 4: Types of RJ Research Conducted by FPT Ministries, 2000-2010

Chart 4: Types of RJ Research Conducted by FPT Ministries, 2000-2010

This bar chart shows the type of RJ research or evaluation conducted FPT ministries. The four most common types of research/evaluation conducted, in decreasing order, are: qualitative/interview (82%), empirical/statistical (73%), outcome evaluation (55%), and process evaluation (55%).

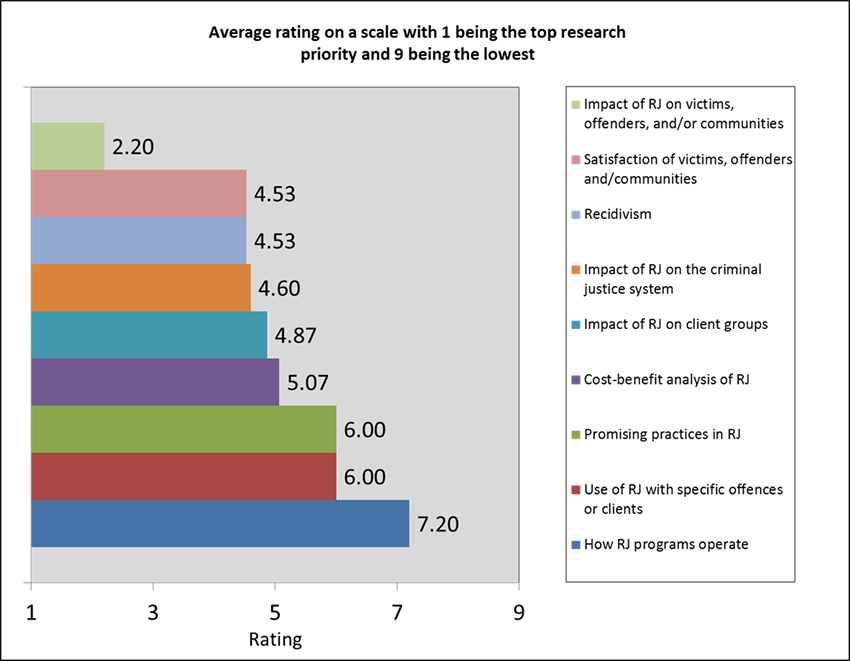

The Working Group was also interested in what kinds of research or evaluation topics regarding RJ in the criminal justice system would be priorities for FPT jurisdictions, assuming that resources were available to conduct the research. There did not appear to be consensus on this matter. Respondents were provided with nine options for potential research and evaluation topics and were asked to rate them on a scale from 1 to 9, with 1 being their top research priority and 9 being their lowest. As Chart 5 illustrates, research about the impact of RJ on victims, offenders and communities was viewed as the top priority, since 80% of the 15 respondents who replied to this question rated it as one of their top three choices. The impact of RJ on recidivism received a rating of 60%, making it the second highest priority for research and evaluation. Chart 6 indicates that the impact of RJ on victims, offenders and communities received by far the highest rating, with an average rating of 2.2. The satisfaction of victims, offenders and/or communities, recidivism, the impact of RJ on the criminal justice system, the impact of RJ on client groups, and cost-benefits analysis were also priorities, although respondents varied on the rating they assigned to these topics.

The area regarded as the lowest priority for research and evaluation was how RJ programs operate, followed by promising practices and using RJ with specific kinds of offences or clients. However, there was a great deal of variation in the rankings of potential topics, and one should be careful about drawing conclusions given the small number of responses.

Some respondents suggested that there is interest in continued research and a national data collection exercise. For example, one person wrote:

Resources could be dedicated to undertaking research and evaluation of restorative justice in the criminal justice sector. A national survey on restorative justice would be very informative if the definitional concerns could be addressed. Additionally, it might be a good time to consider another meta-analysis on restorative justice programs in Canada as a follow-up to the work undertaken in the early 2000s by Jeff Latimer and others in the Department of Justice [Latimer, Dowden, & Muise, 2001].

Chart 5: Percentage of Topics that Received a Top 3 Rating

Chart 5: Percentage of Topics that Received a Top 3 Rating

This bar chart shows the priority given to RJ research topics by the percentage of times it was given a top 3 rating by ministries. Research on the impact of RJ on victims, offenders and/or communities was given a top 3 rating by 80% of ministries and research on recidivism by 60% whereas promising practices in RJ was only chosen 7% of the time.

Chart 6: Average Rating of Research Priorities

Chart 6: Average Rating of Research Priorities

: This bar chart shows the average rating given to different RJ research topics by FPT ministries (1 being top priority). Research on the impact of RJ on victims, offenders and/or communities received the highest average rating at 2.2. Research on how RJ program operation received the lowest average rating at 7.2. All other topics received an average rating between 4.5 and 6.

3.7 Training

Nineteen respondents answered a question about whether their ministry funded, supported or provided training on RJ. Virtually all (n=17, or 89%) indicated that their ministry had provided training, although not necessarily on an ongoing basis. Depending on the jurisdiction and topic, the training was offered to community-based practitioners and volunteers, justice officials such as police and Crown prosecutors, government employees, and others, and it covered topics such as:

- Basic concepts RJ.

- How the criminal justice system works.

- The practice of RJ, such as the facilitator's role, types of restorative models, steps for facilitating cases, and how to facilitate specific models such as victim-offender mediation.

- Specialized training on matters such as victim needs; cultural sensitivity; using RJ with serious violent crimes; dealing with trauma; working with clients who have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder; crime prevention; and offender reintegration.

- Government policies, procedures and legislation related to RJ programs.

- Managing and operating RJ programs, such as reporting, program administration and evaluation.

- The role of volunteers in RJ.

3.8 Procedures, Policies or Protocols on the Use of RJ

Most respondents (89%) indicated that their ministry had procedures, policies or protocols related to the use of RJ in the criminal justice sector. These documents included items such as:

- The referral and facilitation of cases.

- The structure and administration of RJ programs.

- Expectations or guidelines to assist community-based RJ programs with developing local policies and procedures.

- Guidelines or standards covering topics such as referrals; victim participation; program delivery; monitoring and reporting; agreements resulting from conferences facilitated under the Youth Criminal Justice Act; and matters related to protection and disclosure of personal information, particularly for young persons.

- A directive that clarified responsibilities regarding requests for victim-offender mediation or any form of contact between the victim and offender.

3.9 Other RJ Activities

The survey provided an option for respondents to describe other kinds of activities related to RJ in the criminal justice sector that their ministries funded, supported or provided. Five out of 19 respondents (26%) indicated that their ministries were involved in other kinds of activities such as:

- Preliminary research and exploration of other approaches to criminal justice, wellness and community development.

- Developing resources, disseminating information, promoting RJ and organizing and participating in conferences.

- RJ coalitions, networks or associations.

- Discussion groups asking offenders to reflect on RJ principles and concepts.

- Restorative programs that enable offenders to undertake projects to make amends with the community.

- Using restorative approaches with cases of elder abuse.

- A pilot program working in partnership with police and university to use restorative approaches to address criminal behaviour by students.

- Crime prevention programs that use RJ approaches.

- Working with schools and school boards for restorative practices in schools.

The fact that most respondents did not indicate other activities suggests that the survey was successful in regards to including questions related to the most common types of RJ activities in the criminal justice sector.

3.10 Other Comments

Respondents also had an opportunity to provide other comments about data collection, evaluation or research in regards to RJ in the criminal justice sector. Several respondents chose to provide additional comments that expressed challenges and difficulties in these areas. In particular, they indicated that these challenges often result from having different collection methods and definitions. Here are three examples of comments from various respondents:

[It is] challenging to agree on terminology, to share information across agencies and governments with different privacy regimes, to maintain continuity as partners change, etc.

It is difficult to capture quantitative results using standard measurement tools in order to capture benefits of RJ beyond satisfaction and recidivism (ex. development of victim empathy, accountability, etc.) It is also difficult to compare one RJ program to another as they may use different methods, definitions, targets, etc. Furthermore, many programs have not yet implemented formal evaluation processes due to consent issues, confidentiality concerns, length of process, and clients and practitioners feeling uncomfortable with the evaluation process.

I see immense challenges related to the diversity of RJ programs in terms of who delivers the program, at what stage of proceedings RJ is practiced, whether it is a dedicated/stand-alone RJ service or a practice incorporated into a larger service, what the intended outcomes are (i.e. reduction in recidivism vs. victim satisfaction)...But probably the most challenging is how to establish a true "control group" for comparison.

4.0 Final Thoughts

This report presents data gathered by the FPT Working Group on Restorative Justice to provide a "snapshot" about the use of RJ in the Canadian criminal justice sector. It includes data from 19 ministries or departments in 12 FPT jurisdictions. While the amount of information collected was less comprehensive than hoped, this report is a step toward understanding the use of RJ, potential priorities for research and evaluation, and challenges regarding data collection.

The data indicates that there was wide variation regarding the kinds of RJ programs funded, supported or provided by the FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey. As of 2009/10, 13 ministries funded or supported 411 programs that fell under the definition of RJ provided for the survey, and there were at least 21,504 youth referrals and 12,277 adult referrals. These figures include pre-charge, post-charge and post-sentencing referrals, but exclude Québec and Prince Edward Island.

The survey also identified the kinds of RJ models used. Various types of conferences (such as family group conferences, community justice conferences, and community justice forums) were the most common, followed by victim-offender mediation.

Additionally, the survey provided information about the topics covered during RJ training, and confirms that most FPT jurisdictions have policies, procedures or protocols about matters such as referrals, procedures for facilitating cases, and the structure and administration of RJ programs.

The results suggest that there is a need for additional data collection and evaluation about RJ in the Canadian criminal justice sector. While coming to consensus about a definition of RJ was a major step forward, it would be necessary to continue working on common definitions, data indicators and collection methods. Most of the FPT jurisdictions that participated in the survey indicated that they would be interested in discussing some kind of future data collection exercise, and the FPT Working Group on RJ is considering updating this report to determine how the use of RJ in the Canadian criminal justice sector has changed since 2009/10. In the meantime, this information is helpful in beginning to understand the extent to which RJ is used in Canada.

References

Church Council on Justice and Corrections. (1996). Satisfying Justice: Safe Community Options that Attempt to Repair Harm from Crime and Reduce the Use or Length of Imprisonment. Church Council on Justice and Corrections.

Cormier, Robert. (2002). "Restorative Justice: Directions and Principles - Developments in Canada." Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group on Restorative Justice. (December 22, 2009). "Key Messages on Restorative Justice." Online: key-messages-restorative-justice.html

Latimer, Jeff, Dowden, Craig, & Muise, Danielle. (2001). "The Effectiveness of Restorative Justice Practices: A Meta-Analysis". Research and Statistics Division, Justice Canada.

Tomporowski, Barbara. (2014). "Restorative Justice and Community Justice in Canada." Restorative Justice: An International Journal 2 (2): 218-224.

Tomporowski, Barbara, Buck, Manon, Bargen, Catherine, & Binder, Valarie. (2011). "Reflections on the Past, Present and Future of Restorative Justice in Canada." Alberta Law Review 48 (4): 815-830.

Umbreit, M., Coates, R., Kalanj, B., Lipkin, R., & Petros, G. (1995). Mediation of Criminal Conflict: An Assessment of Programs in Four Canadian Provinces — Executive Summary Report. Center for Restorative Justice & Mediation, School of Social Work, University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Return to footnote 1 Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group on Restorative Justice. (December 22, 2009). "Key Messages on Restorative Justice." Online: key-messages-restorative-justice.html. This definition has been adapted from Cormier, 2002.

- Footnote 2

-

Return to footnote 2 Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group on Restorative Justice. (December 22, 2009). "Key Messages on Restorative Justice." Online: key-messages-restorative-justice.html

- Footnote 3

-

Return to footnote 3 Tomporowski, Barbara. (2014). "Restorative justice and community justice in Canada". Restorative Justice: An International Journal 2 (2): 218-224.

- Footnote 4

-

Return to footnote 4 Tomporowski, Barbara, Buck, Manon, Bargen, Catherine, & Binder, Valarie. (2011.) "Reflections on the Past, Present and Future of Restorative Justice in Canada." Alberta Law Review 48 (4): 815-830.

- Footnote 5

-

Return to footnote 5 Supra.

- Footnote 6

-

Return to footnote 6 Supra.

- Footnote 7

-

Return to footnote 7 Community justice committees are groups of local citizens who are interested in being involved in justice issues. Depending on the location and the community's needs, they undertake a range of activities from crime prevention to RJ. Youth justice committees, which are established under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, do not necessarily incorporate RJ processes or principles in their work. This report includes only those community justice committees or youth justice committees that fall under the definition of RJ used in the survey.

- Footnote 8

-

Return to footnote 8 Number of youth and adult cases where it is unknown whether they were referred at the pre-charge, post-charge, or post-sentence point of the criminal justice process.