Briefing book for the President of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada - 2019

[ * ] An asterisk appears where sensitive information has been removed in accordance with the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act.

Text version - Democratic institutions landscape

State of democracy in Canada

- Strengths:

- strong legislative electoral framework;

- reputable and independent election administration bodies;

- constitutionally-protected democratic rights.

- Areas for improvement:

- citizen participation;

- foreign interference;

- disinformation.

Domestic partners

- Federal: Minister of National Defence; Minister of Justice and Attorney General; Minister of Foreign Affairs; Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development; Minister of Canadian Heritage; National Security Agencies.

- The House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, and the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

- Provinces and territories.

Hot issues

- Protecting Democracy: Assessment of the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol by an external independent reviewer. Copies to PM, NSICOP and the public.

- Response to Leaders’ Debate Commission: report on its findings and advice following the 2019 general election, to be provided by March 2020. Tabled in Parliament.

- Chief Electoral Officer Reports: Report on the 43rd general election expected by early 2020; Recommendations report expected in Autumn 2020.

Ministerial responsibilities and priorities

- Canada Elections Act;

- Referendum Act;

- Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act;

- Senate Reform;

- The Plan to Protect Canada’s Democracy;

- Leaders’ Debates Commission.

- Electoral Framework: The Canada Elections Act (the Act) – which is amended periodically to respond to emerging issues – regulates federal elections, including through limits on contributions to political actors, limits on how much political actors can spend during an election period, transparency and disclosure rules, and enforcement and compliance mechanisms.

- Redistribution of Federal Electoral Districts: Review of the process for redistributing federal electoral districts, including amendments to the electoral Boundaries Readjustments Act and the seat allocation formula set out in the Constitution Act, 1867, ahead of the 2022 redistribution process.

- The Senate: 25 projected vacancies from November 2019 to December 2023: 5 in 2019; 7 in 2020; 4 in 2020; and, 5 in 2023. Support the Senate’s evolution to an independent, non-partisan institution. Engage provinces and territories on potential IABSA members.

- Protecting Democracy: Evaluate initiatives: Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections Task Force, Critical Election Incident Public Protocol and Digital Citizen Initiative. Engage P/T governments and political parties to foster protection from foreign election interference.

- Leaders’ Debates Commission: whether to act on the Commissioner’s recommendations (March 2020).

International environment

- Canada’s approach to counter foreign interference in its democratic institutions has been lauded by international partners.

- UK, US and Singapore have all noted the well-considered and comprehensive work accomplished.

- Foreign interference in DI now a standing item within G7 and among Five Eyes partners.

- Canada leading G7 Rapid Response Mechanism international information-sharing mechanism.

- Engagement with digital and social media companies in for a like the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace.

43rd general election - A few important pieces

- 40 day campaign and 1st election with a legislated pre-electoral period.

- 97 (28.7%) elected women MPs, compared to 88 (26%) in 2015 and 77 (25% of 308 ridings) in 2011.

- 10 (2.96) elected Indigenous MPs, which is the same as 2015.

- 2,146 candidates in 338 ridings.

- 65.95% turnout, which is 2.35% lower than 2015 but 4.55% higher than 2011.

- 119 vote on campus stations (111,300 voters) compared to 39 vote on campus stations (70,000 voters) in 2015.

- 29% increase in advance polling turnout.

- 34,324 special ballots received from international voters compared to 11,000 in 2015.

- Management of significant disruption in Manitoba due to severe weather.

Key partners

- Elections Canada: administers federal elections and referenda:

- Chief Electoral Officer: Stéphane Perrault, since 2018, on a 10 year term.

- Commissioner of Canada Elections: investigate offences against the CEA.

- Commissioner: Yves Côté, since 2012, on a 10 year term.

- Departmental Support:

- 12 FTEs supporting the Minister

- Leverages support from across PCO

- Key Domestic Stakeholders: Samara Centre for Democracy; CIVIX; MediaSmarts; Apathy is Boring; Equal Voice; Centre for International Governance and Innovation.

- Academic think tanks: Public Policy Forum; Institute for Research on Public Policy; Press Progress; Centre for the Study of Democracy and Diversity; Freedom House;

- Internet Companies: Facebook (& Instagram); Twitter; Google (& YouTube); Microsoft.

Timeline - November 2019 to February 2024

- November 2019 - Swearing in of new government

- November 2019 - Five new senate vacancies for 2019

- February 2020 - Expectation of CEO post-election report

- March 2020 - Expectation of Debates Commissioner report

- September 2020 - Expectation of CEO recommendations report

- November 2020 - Seven new senate vacancies for 2020

- July 2021 - Four new senate vacancies for 2021

- October/November 2021 - CEO and Minister of DI receive population estimates from the Chief Statistician

- February 2022 - 2021 Decennial Census data sent to CEO and Minister – start of boundary review by Commissions

- Spring 2022 - Last possible time to amend CEA

- June 2022 - Four new Senate vacancies for 2022

- July/August 2022 - Appointment of new Commissioner for Canada Elections

- February 2023 - Latest possible date for Commissions to submit their redistribution reports to the House of Commons

- October 2023 - 44th general election

- December 2023 - Five new senate vacancies for 2023

- February 2024 - New federal election districts come into effect.

- As the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you are the designated Minister responsible for the following statutes:

- the Canada Elections Act;

- the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act; and

- the Referendum Act.

- You also:

- play a leadership role in advancing efforts to protect Canada’s democracy from threats of foreign interference;

- have a role in determining the way forward for the Leaders’ Debates Commission;

- are responsible for policy initiatives in relation to the Senate; and

- are the instructing client for court cases related to democratic reform.

- While you are the Minister responsible for Elections Canada, this does not include a direct oversight function. Elections Canada, under the Chief Electoral Officer as an independent officer of Parliament, is the independent agency responsible for day-to-day administration of electoral legislation, the conduct of elections, and supporting the readjustment of electoral boundaries.

- The Privy Council Office provides you with public service support related to your policy and legislative responsibilities. The Democratic Institutions Secretariat is the lead policy group for matters related to the reform of democratic institutions and processes.

Legislative and policy responsibilities

Canada Elections Act

The legislative framework governing federal elections in Canada is primarily set out in the Canada Elections Act (CEA). The CEA sets out the rules governing the overall administration of a federal election and the activities of political entities (candidates, political parties, electoral district associations, nomination contestants, and leadership contestants). These rules include limits on contributions to political parties and election candidates, spending limits for political actors during an election campaign, transparency and disclosure rules, and enforcement mechanisms designed to enhance compliance.

The CEA is amended periodically (e.g. 2003, 2006, 2014, and 2018) to address emerging issues and adapt to the evolving electoral environment. Amendments are informed by recommendations made by the Chief Electoral Officer following each general election. The most recent comprehensive amendment of the CEA was in 2018 through the Elections Modernization Act.

As the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you are responsible for the CEA. This would include introducing any proposed amendments in the House of Commons. Further information on the CEA, including potential amendments for your consideration, is included at tab 2A. [ * ]

Protecting Canada’s democracy

In advance of the October 2019 federal election, the Government of Canada put in place a range of measures to address threats of foreign interference. The Canadian plan drew on the experiences of like-minded countries in their own elections as well as key findings from the Communications Security Establishment’s 2017 report on Cyber Threats to Canada’s Democratic Processes.

The Minister of Democratic Institutions provided leadership for this cross-government effort. A post-election evaluation of remaining gaps in the Canadian posture will support decision-making with respect to what initiatives should be formalized, and which ones need to be improved. Further information on this initiative is included at tab 2C.

Leaders’ Debate Commission

The Leaders’ Debate Commission was established in 2018 with a mandate to organize two leaders’ debates, one in each official language, for the October 2019 federal election.

Following the election, the Commission is required to produce a report outlining its findings and providing advice for the potential creation of a permanent Commission. The report is to be provided to you by March 21, 2020 for tabling in the House of Commons. Further information on the reporting process and potential next steps is included at tab 2E.

Senate

As the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you could be responsible for policy initiatives in relation to the Senate and Senate reform. Where such initiatives impact the Parliament of Canada Act, collaboration would be required with the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons who has responsibility for this statute. Further information on the Senate, including potential reform initiatives for your consideration, is included at tab 2F.

Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act

Canada’s Constitution requires that federal electoral districts be reviewed after each decennial (10 year) census and adjusted (or redistributed) to reflect changes and movements in Canada’s population.

The Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act (EBRA) sets out the roles and responsibilities, process, and criteria for redistribution, and establishes the independent commissions tasked with making final decisions with respect to changes to the electoral districts in each of the provinces. The 18- to 20-month process for establishing electoral boundaries is highly prescriptive, and enshrined in law to minimize opportunities for partisan politicization of the exercise or gerrymandering. To promote neutrality, timelines and activities are pre-established and transparent, and the 10-year cycle for re-evaluation limits the potential for parties to change boundaries to gain political advantage.

Since the next fixed-date election is scheduled to take place before the redistribution process is completed, the new electoral map will only apply to the 45th General Election. [ * ] Should the next General Election be called early, it could mean that the redistribution process would begin shortly after the election and as result it could be completed within a single mandate.

[ * ]

The latest amendments to the EBRA and the seat allocation rule in the Constitution were made in 2011 and included altering the formula used to calculate the number of seats in the House of Commons, as well as shortening considerably the boundary readjustment process.

As the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you are responsible for the EBRA. This would include introducing any proposed amendments in the House of Commons. Further information on the EBRA, including potential amendments for your consideration, is included at tab 2G.

Referendum Act

The Referendum Act (RA) provides the general statutory framework for holding a referendum, which is initiated at the discretion of the Governor in Council. The RA does not include the basic operational framework for holding a referendum. Instead, it delegates to the Chief Electoral Officer the authority to make regulations by adapting the CEA for the purpose of a referendum.

The RA was enacted in 1992 to consult Canadians on the Charlottetown Accord. The RA has not been used since the Charlottetown Accord, and there have been no substantial updates since its enactment. [ * ]

As the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you are responsible for the RA. This would include introducing any proposed amendments in the House of Commons. [ * ]

Litigation

The Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions is the instructing client for court cases related to democratic reform, in particular with respect to Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms challenges to electoral laws and constitutional challenges concerning the Senate.

The Privy Council Office (PCO), in coordination with the Department of Justice and your Office, provides support and instructions on what positions the Attorney General of Canada should take in court on democratic reform matters. [ * ]

Elections administration responsibilities

The Prime Minister, supported by PCO, plays a key role in the calling of general elections or by-elections by setting the dates for the issue of the writs and polling day, which is done through proclamation or order-in-council, respectively.

Elections Canada is the independent agency responsible for the day-to-day administration of electoral legislation and the conduct of elections. To preserve its independence, the Chief Electoral Officer has statutory authority under the Canada Elections Act to draw directly from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for most of its election-related activities, other than the salaries of permanent staff, which are funded by parliamentary appropriation.

While the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions is the minister responsible for Elections Canada, the Minister has no direct oversight function. The Minister submits Elections Canada’s Main and Supplementary Estimates, Departmental Plans, and Departmental Results Reports annually to Parliament, as well as submits Elections Canada’s Treasury Board submissions when the agency requires access to funding that is not covered by their statutory spending authority. We anticipate that Elections Canada will provide you further information on its role and operations under separate cover.

The Commissioner of Canada Elections is responsible for enforcement of the Canada Elections Act. The Commissioner conducts investigations into potential offences under the Act and, where he or she believes on reasonable grounds that an offence has been committed, decides whether to initiate a prosecution.

Public Service support

The Privy Council Office’s Democratic Institutions Secretariat (PCO-DI) supports the Government in the development and implementation of its democratic reform agenda. This includes providing policy analysis, departmental support, and advice to the Prime Minister, and the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions on matters related to the reform of Canada’s electoral processes and democratic institutions.

In particular, PCO-DI supports the policy and legislative responsibilities of the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions by:

- providing policy analysis and advice on democratic reform issues, consulting with the Department of Justice, Elections Canada, and other departments;

- drafting Memoranda to Cabinet, Cabinet presentations, and briefing notes;

- directing the drafting of democratic reform legislation;

- providing support during the parliamentary process for democratic reform bills, including drafting speeches, appearing before parliamentary committees, and preparing amendments to legislation as necessary; and

- drafting communications material, ministerial correspondence, answers to parliamentary questions and petitions, and other material.

The Deputy Minister responsible for PCO-DI is Ian McCowan, Deputy Secretary to Cabinet (Governance) and the responsible Assistant Secretary is Al Sutherland, Assistant Secretary to Cabinet (Machinery of Government and Democratic Institutions). PCO-DI currently includes a team of nine analysts, an administrative assistant, a Director of Special Projects, and is led by Sarah Stinson, Director of Operations.

PCO Communications provides you with communications support and support for any consultation activities you may wish to undertake.

Issue

A number of issues relating to your mandate may require action in the first few months following your appointment.

Critical Election Incident Public Protocol

Through a Cabinet Directive, the former Government tasked a panel of five senior public servants (the Panel) with informing Canadians of any incidents or threats to the October 2019 general election that were deemed to be severe enough to undermine the integrity of the election.

The Cabinet Directive requires an independent assessment of the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (the Protocol) following the election to help inform a decision about whether to make the Panel permanent for future elections and, if so, whether to make any improvements or adjustments. The full report will be sent to the Prime Minister and to the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, and a public version will be made available. Your office would receive a copy of the report at the same time as the Prime Minister.

It is possible that other bodies or agencies, most notably the National Security Intelligence Review Agency or the National Security Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians, will also examine the Protocol, either as a focal point, or as part of a larger review. These bodies have the mandate to look at anything related to national security.

[ * ]

Leaders’ Debates Commission report to Parliament

Following the October 2019 general election, the Leaders’ Debates Commission is required to produce a report outlining its findings and providing advice for the potential creation of a permanent Commission. The report is to be provided to you by March 21, 2020 for tabling in the House of Commons. The House may refer the report to the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (PROC). [ * ]

[ * ]

Chief Electoral Officer reports to Parliament

Following the October 2019 general election, Canada’s Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) is required to submit to the House of Commons, through the Speaker, several reports of interest - including a narrative report on the conduct of the election and a report with recommendations on potential amendments to the Canada Elections Act.

Based on past practice, it is anticipated that the narrative report will be submitted by early 2020, with the recommendations report to follow in early fall 2020. [ * ]

[ * ]

Overview

Purpose

- To provide an overview of the state of Canadian democracy and identify opportunities to enhance democratic institutions

Outline

- International context: democracy in decline

- Canada: strong foundations

- Indices

- Trust in government

- Challenges facing Canadian democracy

- Opportunities for action

Challenging times for democracy internationally

- Trust levels in government internationally remain low

- Increasing divergence between better and under-informed populations

- Populist impulses sometimes seen as taking a hostile stance against democratic institutions (e.g., free press)

- Diminished confidence in democracy and political institutions

- Increased participation of women in past decade strongest advancement

- Concerns of a steady decline in basic freedoms internationally and roll-back of post-Cold War democratization

- Some suggestions that a wholly negative picture could be misleading

- Gains and downturns in individual countries may balance each other out at the global level

- Political participation increased (e.g., voting, protests) in some countries in response to domestic and international events

- Important to disentangle popularity of Government from support of democratic institutions

- Canada is not immune to these concerns and pressures

Canada perceived as a strong democracy…

- Freedom House Freedom in the World Report (2019) - Canada recognized as one of the most free countries

- Scores 99/100 and ranks among freest nations even as global freedom declines for 13th consecutive year

- International IDEA Global State of Democracy Indices (2018) - Canada remains relatively stable over four decades

- Scores well across indicators such as fundamental rights, representative democracy and impartial administration

- Economist Democracy Index (2018) - Canada continues to occupy sixth place globally

- Driven by high scores in civil liberties, effective functioning of government and electoral process integrity

The Economist Democracy Index (2018) Rank Country Overall score 1 Norway 9.87 2 Iceland 9.58 3 Sweden 9.39 4 New Zealand 9.26 5 Denmark 9.22 6 Canada 9.15 7 Ireland 9.15 8 Finland 9.14 9 Australia 9.09 10 Switzerland 9.03

…built on a sound foundation

- Strong legislative electoral framework

- Reputable and independent election administration bodies

- Constitutionally-protected democratic rights

- Free media

- Good governance

- Independent judicial system

Three out of four (75%) Canadians are “fairly” or “very” satisfied with the way democracy works in Canada.

Source: Samara Center for Democracy, 2019

Trust in government: critical to health of democracy

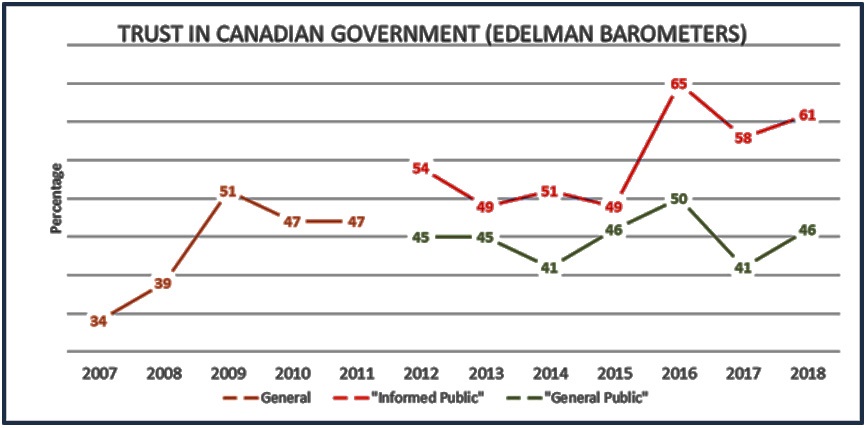

- Trust in government has increased since the early 2000s

- Internationally, Canada scores as “neutral”, indicating neither high levels of trust nor distrust in government

- Edelman has identified a gap in trust between those identified as “well-informed” and the overall population

Text version - Trust in canadian government (Edelman Barometers)

Year General Informed public General public 2007 34 2008 39 2009 51 2010 47 2011 47 2012 54 45 2013 49 45 2014 51 41 2015 49 46 2016 65 50 2017 58 41 2018 61 46

Warning signs: challenges facing Canadian democracy

- Citizen participation: Relatively low voter turnout and small percentage of Canadians involved in traditional political activities

- Foreign interference: Canada, like the majority of Western democracies, is a target of foreign state efforts to interfere with or damage our democratic processes (cyber and non-cyber interference activities)

- Disinformation: Canadians are exposed to increasingly sophisticated attempts to influence them from both international and domestic actors

- Social cohesion: Growing wedges in social cohesion can lead to increased distrust and a dampening of civic participation, exacerbated by social media

- Diversity: Parliament not a representative microcosm of society (e.g. women compromise slightly more than 50% of the population and 29% of the House of Commons)

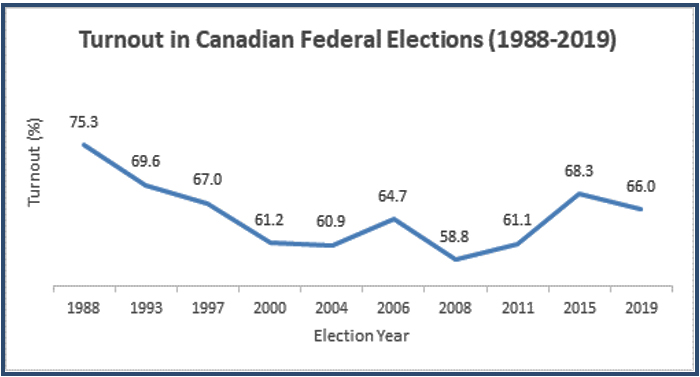

Voter turnout in Canada’s federal elections

- Voter turnout relatively low compared to other leading democracies

- Steady decline since early the 1990s

- Averaging 61.4% between 2004 and 2011

- Increase in 2015 to 68.3%

- Decline in 2019 to 66%

Text version - Turnout in Canadian Federal Elections (1988-2019)

Election year Turnout (%) 1988 75.3 1993 69.6 1997 67.0 2000 61.2 2004 60.9 2006 64.7 2008 58.8 2011 61.1 2015 68.3 2019 66.0 Turnout of top 10 in The Economist Index Country Voter turnout Norway 78.2 Iceland 79.2 Sweden 87.2 New Zealand 79.8 Denmark 84.6 Canada 68.3 Ireland 65.1 Finland 68.8 Autralia 91.0 Switzerland 48.5 - Factors for not voting:

- Decrease in voter turnout linked to lower levels of participation among youth and lack of re-engagement

- Everyday life issues (e.g., family obligations, conflicts)

- Negative public attitudes towards politicians and institutions (e.g. belief that voting is not a civic duty, lack of political interest)

- Illness or disability

Lessons from the 2019 election campaign

- All major parties took advantage of PBO platform costing; broadly seen as having increased quality of information available to voters

- First debates held under independent Leaders’ Debates Commissioner provided opportunity for experimentation and lessons learned

- [ * ]

Opportunities for action

- As Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, there are opportunities to positively impact Canada’s democracy, including by:

- [ * ]

Issue

Whether to amend the Canada Elections Act to address outstanding issues and respond to upcoming recommendations of the Chief Electoral Officer.

Context

The legislative framework governing federal elections in Canada is primarily set out in the Canada Elections Act (CEA). The CEA includes limits on donations to political parties and election candidates, spending limits for political actors during an election campaign, transparency and disclosure rules, and enforcement mechanisms designed to enhance compliance. It also sets out the rules governing the activities of political entities, as well as the overall administration of a federal election.

Since it first came into force in 19521, the CEA has been amended on a number of occasions to address emerging issues and to adapt to the evolving electoral environment. More specifically, the CEA was significantly amended in 2003, 2006, 2014, and 2018. These amendments are often informed by recommendations made by the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) following each general election. Recommendations following the 43rd General Election are anticipated for September 2020.

Bill C-76, the Elections Modernization Act, which was adopted in December 2018 and fully came into force on June 13, 2019, constitutes the most recent comprehensive amendment to the CEA. Among other things, the legislation included the creation of a pre-election period and additional regulations for third parties.

Bill C-76 represented a significant undertaking. In total, two years elapsed between the CEO recommendations report and Royal Assent. This included a study of the CEO’s report initiated by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (PROC) (October 2016 – June 2017), policy development and legislative drafting (March 2017 – April 2018), and parliamentary consideration (April 2018 – December 2018). As part of the latter, PROC considered about 150 proposed amendments, of which 50 were accepted.

Even though Bill C-76 addressed more than 85 percent of the recommendations from the CEO, there continues to be areas for improvement. In particular, stakeholders, academics, and some parliamentarians have raised concerns on two issues.

Privacy protection

While federal political parties hold significant amounts of personal information on Canadians, they are not covered by the federal privacy protection regime, which is comprised of two main frameworks: the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronics Document Act (PIPEDA).

The CEA requires that Elections Canada (EC) share its lists of electors, and states how, when and to whom the lists are to be shared, and how the lists are to be used by the recipients. The CEA does not provide additional rules about personal information collected from sources other than the lists of electors. With the 2018 amendments, the CEA now requires political parties to have a publically available privacy policy as a condition of their registration.

A more detailed analysis of this issue can be found at tab 2B.

Political broadcasting

The CEA includes a broadcasting regime that regulates the allocation of free and paid broadcasting time to registered political parties. The regime is administered by a Broadcasting Arbitrator appointed by the CEO.

Despite multiple recommendations by the CEO following previous general elections, along with significant changes that broadcasting has seen over the years (e.g., the role of social media), the regime has remained substantially unchanged since it was introduced in the CEA in 1974.

Policy assessment

Privacy protection

While the 2018 amendments represented a first step in acknowledging the need for political parties to consider privacy responsibilities in their activities, academics, stakeholders, the CEO, the Commissioner of Canada Elections, and the Privacy Commissioner have all indicated that these requirements for a privacy policy fail to address the lack of privacy laws governing political parties.

[ * ]

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics December 2018 report argued that PIPEDA should be extended to political parties, third parties and political activities, and that the Privacy Commissioner should be given the power to make orders, conduct audits, seize documents, and impose administrative monetary penalties for non-compliance.

In late-August 2019, the BC Information and Privacy Commissioner determined that, in his view, federal political parties are covered by BC’s privacy legislation. While this only means that the office’s investigation into two federal parties will continue, because of the potential wide-ranging repercussions, PCO-DI continues to closely monitor this investigation.

[ * ]

Political broadcasting

Despite recommendations included in past reports of the CEO (following the 37th, 38th, and 42nd general elections), the relevant sections of the CEA have not been amended since it was enacted in 1974. The field of broadcasting has dramatically changed since then, with a decline in traditional television viewership and a drastic rise in the use of the Internet for cultural programming and political advertising. The broadcasting regime has not evolved in parallel and is no longer adapted to the current environment.

In particular, the CEO has consistently emphasized three main concerns throughout his recommendations: that the political broadcasting section is unnecessarily complex; that it imposes the free broadcasting time on only a few actors; and that it favours parties that have been the most successful in the past.

The political broadcasting regime is intended to ensure equity among political actors. The purchasable time assures that broadcasting time cannot be monopolized by one party, and the free broadcasting time helps ensure that the communication of political ideas to Canadians is not solely dependent on financial resources.

Successive governments have indicated that their decision to not proceed with amendments to this part of the CEA were due to the need for extensive consultations on this complex issue. Following the 42nd election, PROC, in studying the CEO’s recommendations, noted that the “Committee [was] of the view that to give adequate study to a recommendation of such breadth and complexity necessitates a greater time period for information gathering and deliberation than the Committee currently has at its disposal.” [ * ]

Any changes to the political broadcasting section will need to be considered in light of the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review Panel, which will release its final report at the end of January 2020. Changes to the Broadcasting Act may have ramifications for the CEA’s political broadcasting regime.

Implementation

There are important timing considerations with respect to introducing amendments to the CEA. Because the recommendation report of the CEO is not expected before the fall of 2020, [ * ]

In addition, the CEA provides that no amendments apply in an election for which the writ is issued within six months after the passing of the amendment, unless the CEO certifies that the necessary adoption has been made. Elections Canada requires time to implement any changes prior to the conduct of an election.

[ * ]

In addition to privacy protection and the broadcasting regime, other issues have emerged that could be addressed if amendments were proposed to the CEA, as described in Annex A.

Recommendation

[ * ]

Annex A: Additional issues

The following issues have been raised during the 2019 pre-election and election periods, or have been highlighted by academics, researchers, and other stakeholders. As such, some of the issues may be raised in the CEO’s recommendations report.

- Third party regime: The third party regime set out in the CEA regulates the activities of third parties (individuals, corporations, unions, etc.) during the pre-election and election periods. The 2018 amendments to the CEA increased requirements for third parties. Stakeholders have suggested additional measures to regulate third parties further (e.g. establishing a contribution limit to third parties, increasing the length of pre-election period). [ * ]

- Foreign funding and influence: Parliamentarians studying the 2018 amendments and other key stakeholders raised foreign funding as an issue, including the potential of foreign funds being used to influence public opinion around contentious issues (e.g., pipelines and energy). [ * ]

- Financial incentive for IT security: Because political parties’ information systems are not protected by national security agencies, they are more at risk of being victims of cyberattacks. [ * ]

- Social media: While recent CEA amendments, among other governmental initiatives, have sought to engage social media platforms with respect to democracy and elections, a number of issues may need to be further addressed, as described in tab 2D.

- Unsolicited mass text messages: Prior to, and during the 2019 pre-election and election periods, political parties and third parties have sent mass text messages to millions of randomly generated phone numbers. Political parties are exempted from the anti-spam legislation and the Do-Not-Call list because of the need for political parties to engage with Canadians. [ * ]

- Election date: This past summer, two Jewish individuals, including a candidate, sought judicial review of the Chief Electoral Officer’s (CEO) refusal to recommend that the date for the federal general election be moved on the basis that it interfered with a Jewish holiday. While the Federal Court found that the CEO failed to evidence adequate consideration of the Applicants’ Charter rights, the CEO subsequently confirmed his decision to maintain the original date. The issue generated significant media coverage and criticism. [ * ]

- Nomination and leadership contests: Political parties establish their own rules for nominating candidates, as well as for leadership contests. Stakeholders have raised concerns that these rules can create barriers for prospective candidates, or that such contests could be used as a point of entry for foreign interference. Currently, the CEA only regulates certain financial aspects in each of these areas. [ * ]

- Definition of a leadership contestant: According to the CEA, an individual remains a leadership contestant until they file the required financial reports with Elections Canada, even if the contest has long ended or the individual has withdrawn from the contest. In August 2019, it was reported that January 2019 fundraising events attended by former CPC leadership contestants were deemed to be regulated events subject to the reporting regime introduced through Bill C-50, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act (political financing). As a result, both Members of Parliament refunded all donations associated with the event. [ * ]

- Election signs: Some municipalities have enacted by-laws that prohibit election signs (and other signs) anywhere on public property because they argue the signs often end up in the trash, and come with significant enforcement and clean-up costs. While the CEA includes one provision that prohibits people from interfering with signs on public property, municipalities are able to remove signs if they do not respect their by-laws. [ * ]

- Timing to call a by-election: According to the Parliament of Canada Act (POCA), a by-election must be called within 180 days of the CEO being officially notified of a vacancy. Critics argue that this limit should be decreased because it is unfair to constituents to be without representation for an extended. [ * ]

- By-election and fixed-date election: The POCA also states that if a seat is vacated within nine months of the fixed-date general election, then no by-election can be called. In the event that the general election is set for a date beyond the fixed-date set in the CEA, the Act is silent on whether the by-election in the particular district should be called. [ * ]

Issue

Whether the application of privacy protection principles should be extended to political parties.

Context

The Canada Elections Act (CEA) defines a political party as “an organization one of whose fundamental purposes is to participate in public affairs by endorsing one or more of its members as candidates and supporting their election”, which, once formed, may apply to be registered to be formally recognized and regulated.

In the course of their activities, political parties collect or are provided by Elections Canada with a significant amount and variety of information on Canadians. The information they collect includes the lists of electors they receive from Elections Canada; party contributors; voter attitudes which can be captured in a number of ways (e.g., public petitions, telephone polling); information on prospective candidates, as well as volunteers and staff; and consumers purchasing party items and other commercial activities.

There has been a steady rise of cases involving data breaches and the harvesting of personal information in recent years, which has spurred concerns in many countries over issues such as privacy and the protection of personal information. The most high-profile case to date has been the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica incident, which was revealed in 2018 as a massive breach of personal information used for the purposes of political advertising. It sparked a number of investigations and studies worldwide, including ones by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC), as well as the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics (ETHI).

In its December 2018 Report entitled Democracy Under Threat, ETHI recommended that privacy legislation be extended to political parties, political third parties and political activities. Similar recommendations have also been made by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO), who made such recommendations in 2011 and again in 2013.

In recognition that the operating environment for political parties has changed significantly, measures were introduced as part of the Elections Modernization Act (2018) to ensure that political parties take greater responsibility for the protection of personal information they preserve on the Canadian electorate. Political parties are now required to have a publicly available, easily understandable policy for the protection of personal information. Political parties are also required to submit their privacy policy when registering with Elections Canada, maintain it, and make it publicly available on their website. Failure to comply would result in refusal of registration or in deregistration. Most expert analyses were critical of this area of reform, judging it to be insufficient.

Despite these new measures, federal political parties continue to fall outside of the statutory frameworks that comprise Canada’s privacy protection regime. This regime includes the Privacy Act, which governs government institutions and agencies, and the Personal Information Protection and Electronics Document Act (PIPEDA), which governs federally-regulated organizations that engage in commercial activities.

At the international level, modernized privacy frameworks have been adopted in several other jurisdictions, the most notable of which has been the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. In Canada, while most provinces have privacy legislation similar to the Privacy Act, only Quebec, British Columbia (BC) and Alberta have privacy legislation in place that is similar to PIPEDA. Of those three provinces, only BC applies its privacy laws – the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) – to political parties, where recent developments have continued to draw attention to this issue.

In the course of an investigation, on August 28, 2019, the BC Information and Privacy Commissioner issued an Order that examined whether the PIPA was validly-enacted provincial legislation and whether the PIPA was applicable to political parties registered under the CEA because federal legislation (e.g., the CEA, PIPEDA) was paramount. The Commissioner determined that the PIPA was validly enacted legislation and did not conflict with existing applicable federal legislation. It follows that federal political parties registered under the CEA must comply with all applicable regimes, be they federal or provincial. The Commissioner has yet to consider the merits of the complaint, the findings of which are expected to be released in the coming months as the investigation is completed.

Policy assessment

Political parties and their operations currently fall outside Canada’s privacy protection frameworks. While private actors for the most part, political parties play an important public function in the electoral process through the ongoing engagement of the Canadian electorate. At the same time, political parties collect a significant amount of information about the Canadian population in the course of their activities, each party has the discretion to establish its own controls on the information it maintains.

Political parties are also vulnerable, either inadvertently from an unauthorized disclosure or from threats or attacks from malicious actors. The 2019 Report from the Communications Security Establishment, entitled “Cyber Threats to Canada’s Democratic Process,” stated that political parties are among the most vulnerable actors in the electoral system to cyber threats and other influence operations. A data breach of these organizations could significantly undermine the public’s trust, damaging Canada’s democratic processes and institutions in the process.

[ * ]

In addition, the BC case outlined above and the potential implications for federal parties will continue to serve as an impetus for change. Absent a federal framework that applies to all political parties, federal political parties will be required to adhere to privacy laws in BC, but may not have to elsewhere in Canada. [ * ]

Privacy Protection Framework options

There are several approaches that could be considered to regulate the protection of elector’s personal information by political parties.

[ * ]

Implementation

Should the Government wish to proceed with setting political parties under a privacy framework, the appropriate framework would need to be determined, as well as a number of important considerations, [ * ]

The impact of establishing or applying a privacy framework for political parties, including cost to the parties, legal risks and the time required to implement new requirements, has not yet been fully examined. [ * ]

As mentioned above, political parties are vulnerable to threats or attacks and their current privacy practices put them at risk for a major privacy breach. [ * ]

[ * ]

Recommendation

[ * ]

Issue

How to continue to build on the efforts already underway to protect Canada’s democracy and safeguard its electoral and democratic processes.

Context

In light of actual and suspected foreign interference in the democratic processes among Canada’s key international allies, the Ministers of Democratic Institutions, Public Safety and National Defence put in place a suite of measures to bolster Canada’s defences against electoral interference for the 2019 General Election. The Canadian plan draws on the experiences of like-minded countries as well as key findings from the Communications Security Establishment’s (CSE) 2017 Cyber Threats to Canada’s Democratic Processes report and other intelligence assessments.

[ * ]

Canada’s democracy is a target for foreign interference for a number of reasons, including that it is a key contributor to the world economy, an important member of the global peace and security infrastructure, and a vibrant multicultural liberal democracy. Foreign adversaries and competitors are increasingly targeting Canada in order to advance their own economic and national security interests and priorities.

The Government’s plan addressed pressing vulnerabilities to the 2019 General Election under four areas of action:

- enhancing citizen preparedness, by putting in place initiatives to improve the critical thinking and digital literacy skills of Canadians;

- improving organizational readiness, by ensuring effective coordination within the security and intelligence community in identifying and responding to threats, and minimizing system vulnerabilities, including those within political parties;

- combatting foreign interference, by sharing best practices with other jurisdictions; and

- expecting social media platforms to act, by establishing voluntary commitments from key digital and social media platforms to improve transparency, authenticity and integrity on their systems.

Some of the key new initiatives established as part of this plan include the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol, which sets out the mechanism through which Canadians would be informed of serious attempts to interfere with their ability to have a free and fair election. Another signature initiative is the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force, which ensures coordination and comprehensive situational awareness among national security and intelligence agencies. The security and intelligence agencies also provided classified briefings to security-cleared representatives of the political parties represented in the House of Commons, to ensure a broad awareness of the threat and to encourage mitigation activities internally within their organizations.

Funding for this initiative came from a number of different sources. Many activities were delivered within existing funding. In addition, [ * ] $7 million was provided to Canadian Heritage to deliver civic, digital and media literacy programming in partnership with civil society organizations.

Budget 2019 also earmarked $48 million for the Protecting Democracy initiative to: fund the revitalization of the counter intelligence program at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) ($23M); ensure cyber security advice and guidance is provided to political parties and elections administrators by CSE ($4.2M); support research and policy development by Canadian Heritage on online disinformation in the Canadian context through the Digital Citizen Initiative and its Digital Citizen Contribution Program ($19.4M); and strengthen cooperation and information sharing with G7 partners through Global Affairs Canada’s Rapid Response Mechanism ($2.1M). [ * ]

Following the January 2019 announcement of the Protecting Democracy initiative, whole-of-government efforts focused on implementation. The SITE Task Force and members of the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol Panel met regularly to ensure smooth coordination and coherence in their roles and responsibilities; the security and intelligence community provided several threat briefings to political parties; tabletop exercises were run within the Government of Canada and with Elections Canada; and Government of Canada officials provided information to Canadians through technical briefings.

Given the pressing timeline of the 2019 General Election, the Protecting Democracy initiative focused exclusively on preparation for the election, leaving broader issues of countering interference in Canada’s democratic institutions – i.e. public servants and government, politicians and political parties, media, the judiciary and others – aside. Interference in democratic institutions beyond the electoral cycle will require focused attention.

Policy assessment

As has been noted several times publicly, the 2019 General Election provided a live test of the suite of preparations to counter interference in Canada’s democratic processes. The focus of these measures was the 2019 election, [ * ] A post-election evaluation of remaining gaps in the Canadian posture will support decision-making with respect to what initiatives should be formalized, and which ones need to be improved.

Some potential gaps in Canada’s response have already been identified. [ * ]

[ * ] To date, the Canadian democratic ecosystem has so far shown itself able to self-correct through fact-checking and the application of traditional journalistic ethics practices. Several instances of misinformation were quickly debunked, corrected, or gained little public traction. This is an early test for the resilience of Canadian system. While these efforts have been sufficient up to this point, a more fractured and divided Canada could make countering misinformation and disinformation more difficult. [ * ]

[ * ]

[ * ] In March 2019, the RCMP hosted a foreign actor interference workshop with the domestic law enforcement community to discuss, share experiences and lessons learned, and look towards developing a plan of action to counter this threat.

[ * ]

Allied countries have adopted varied approaches to preventing interference in their elections. [ * ]

Recommendations

[ * ]

Issue

How to advance engagement with social media platforms (SMPs) to protect and strengthen Canadian democracy.

Whether and how to intervene in a quickly changing technological environment, including how to apply timeless democratic principles (e.g., freedom of expression) in this environment.

Context

Canada Declaration on Electoral Integrity Online

On January 30, 2019, the Ministers of Democratic Institutions, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and National Defence announced the Government of Canada’s plan to defend the electoral system against cyber-enabled and other threats. One pillar of the Government’s Protecting Democracy plan was “expecting social media platforms to act.”

The Government of Canada engaged with representatives from the SMPs between January and May 2019 with the objective of securing voluntary commitments from the SMPs to take concrete actions to increase the transparency, authenticity, and integrity of their systems.

On May 27, 2019, the Government of Canada announced the Canada Declaration on Electoral Integrity Online (See Annex A). The Declaration enumerates a series of joint and individual voluntary commitments by the Government and the platforms. It was endorsed by Microsoft, Facebook, Google and Twitter. The Declaration did not create any legal obligations for the SMPs or the Government.

Social media platforms and election advertising

The 2018 amendments to the Canada Elections Act (CEA) also set out new obligations for the SMPs. This included new transparency and reporting requirements for political advertising, as well as establishing spending limits for political and third parties’ partisan advertising during the pre-writ and writ periods.

The changes to the CEA also included a requirement for digital platforms to maintain a public registry of partisan and election advertising published during the pre-writ and writ periods.

Interdepartmental Team on Platform Governance

In addition to the work undertaken with SMPs as part of the Protecting Democracy plan, the Privy Council Office (PCO) Interdepartmental Team on Platform Governance was also established in November 2018 with a mandate to develop advice for a new government with respect to: online hate, violent extremism and disinformation; platform use of Canadians’ data; and the regulation of online platforms. This Interdepartmental Team’s mandate ends in January 2020.

While the Interdepartmental Team works on issues related to your mandate, it provides advice on issues that cut across government and operates outside your direction.

Policy assessment

Canada Declaration on Electoral Integrity Online

A key question is whether and how to continue forward momentum on the Declaration following the 2019 election.

While all four SMPs that signed the Declaration have taken actions consistent with their commitments under the Declaration, [ * ]

[ * ]

Social Media Platforms and Election Advertising

Fairness is a core value of Canada’s electoral model. It helps ensure that there is an equal opportunity for those running for election to present their case to voters and for voters to have a reasonable opportunity to hear the competing views.

The core elements of this model are well-established:

- legislated spending and contribution limits;

- transparency and disclosure rules; and

- enforcement mechanisms as a means of incentivizing compliance.

The social media environment, including political advertising practices on SMPs, continues to evolve rapidly (e.g., Twitter’s decision to eliminate political and issue advertising on its platform).

A number of developments are creating pressure on, and may undermine, both the ability of parties to have an equal opportunity to have their message heard and citizens’ ability to be informed.

Ambiguity with respect to what constitutes advertising

[ * ]

It should be noted that there are considerable sensitivities with respect to the intersection of self-expression and promotion during campaigns.

Lack of transparency with respect to price and reach

SMPs employ a variety of pricing practices (e.g. auctions), where cost and reach of ad buys is less transparent.

Further, the role of algorithms in promoting or curtailing content also makes the reach of advertising purchases less transparent.

[ * ]

Micro-targeting

Advances in artificial intelligence, the wealth of data that platforms collect about individuals, and the low cost of advertising on SMPs allow candidates and parties to tailor their messaging to small groups or individuals by creating multiple ads on a particular issue or range of issues.

While responsiveness to individual voters can be positive, micro-targeting is often undertaken without informed consent, and can be used to spread polarizing and manipulative content where the volume of messages can erode voters’ capacity to cast their vote in an informed manner.

The clearest example of this, to date, was seen in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, with tens of thousands of iterations of ads on the same issue being run (and tested for effectiveness) on any given day.

While the advertising registry introduced in the Canada Elections Act will add transparency and provide some data on actual advertising practices, [ * ]

Move towards private communications

As the platforms move towards private/encrypted conversations as the foundation of how they work, concerns have been raised about the capacity of the tools used for private communications to potentially undermine CEA provisions, or to facilitate the potential for voter coercion or foreign interference.

This will introduce difficult considerations, such as the trade-offs between respecting the privacy of private communications and protecting the integrity of the electoral regulatory regime. There will, additionally, be significant challenges for enforcement.

[ * ]

Implementation

[ * ]

Interdepartmental Team on Platform Governance Advice

The Interdepartmental Team is recommending that the Government of Canada:

[ * ]

Recommendation

The following actions are recommended:

[ * ]

Annex A – Canada Declaration on Electoral Integrity Online

Social media and other online platforms play a meaningful role in promoting a healthy and resilient democracy. They provide a forum for sharing ideas, encouraging innovation, enabling Canadians to engage in dialogue about important issues and facilitating economic opportunity and civic engagement. However, these platforms have also been used to spread disinformation in an attempt to undermine free and fair elections and core democratic institutions and aggravate existing societal tensions.

Social media and other online platforms and the Government of Canada recognize their respective responsibilities to help safeguard this fall’s election and to support healthy political discourse, open public debate and the importance of working together to address these challenges head-on.

To this end, we commit to working together in the lead-up to the October 2019 federal election to ensure integrity, transparency and authenticity, subject to Canadian laws and consistent with other legal obligations.

Integrity

Platforms will:

- Intensify efforts to combat disinformation to promote transparency and understanding and inform Canadians about efforts to safeguard the Internet ecosystem.

- Apply their latest advancements and most effective tools from around the world for the protection of democratic processes and institutions in Canada, as appropriate.

- Promote safeguards that effectively help address cybersecurity incidents and promote cybersecurity, protect against misrepresentation of candidates, parties and other key electoral officials and ensure privacy protection.

The Government of Canada will:

- Ensure that the platforms have clear Government of Canada points-of-contact for election-related matters for both the pre-election and election periods.

Transparency

Platforms will:

- Ensure transparency for regulated political advertising, including helping users understand when and why they are seeing political advertising.

- Ensure their terms and conditions are easily accessible, communicated in a manner that is easy to understand, and enforced in a fair, consistent and transparent manner.

The Government of Canada will:

- Implement the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol to ensure public communications on cyber incidents are clear and impartial.

- Promote, where possible, lawful information sharing that may assist in detection, identification, or enforcement against malicious actors using the platforms’ products and services.

Authenticity

Platforms will:

- Work to remove fake accounts and inauthentic content on their platforms.

- Work to assist users to better understand the sources of information they are seeing and block and remove malicious bots.

Platforms and the Government of Canada will:

- Work with civil society, educational institutions and/or other institutions to support efforts aimed at improving critical thinking, digital literacy and cybersecurity practices to promote digital resilience across society.

- Facilitate the sharing of information on emerging developments and practices that could help protect Canadian democracy within relevant legal mandates.

Annex B – Platform updates with regard to the declaration

- Facebook has implemented a number of new policies and initiatives designed to comply with the Declaration. These include: a political ads database; numerous partnerships with Canadian organizations; and disclosures on advertisements.

- Many of these initiatives were expanded to Canada from other jurisdictions, and occasionally piloted first in Canada before being expanded globally (i.e., the “View Ads” initiative, now subsumed by the ad archive).

- Google has implemented a number of new policies and initiatives designed to comply with the Declaration. These include: partnerships with Elections Canada and civil society organizations, and the creation of products to help campaigns defend against cyberattacks.

- In late-September 2019, the Head of Government Relations at Google Canada published a blog post outlining all of the ways the company was supporting the general election.

- Twitter has implemented a number of policies and initiatives designed to comply with the Declaration. These include: new user tools (such as author moderated replies, which was piloted in Canada); expanding an advertising transparency centre to Canada; removing fake accounts; working with Canadian civil society organizations; and fostering information-sharing relationships with governmental actors (such as Elections Canada and the Commissioner of Canada Elections).

- Some of the details of these initiatives were provided to PCO in a private briefing.

- In late-September 2019, representatives from Twitter made public announcements that they had not yet detected any insidious influence in the general election on their platform.

Issue

To determine the way forward for leaders’ debates in Canada; whether to repeat the 2019 experiment in future elections, enshrine the Leaders’ Debates Commission (the Commission) in statute, or discontinue the Commission.

Context

Until the 2015 election, leaders’ debates were organized by a consortium of Canada’s five major broadcast networks. Prior to each debate, the consortium negotiated key elements directly with political parties, such as the debate format and the leaders that would be invited to participate.

The closed door nature of the organization of debates became part of the story of the 2015 election. There was significant interest expressed in how debates are organized, how participation criteria are determined, how formats and themes are chosen, and how greater access could be achieved through new means of transmission and outreach.

In 2015, the Government committed to bring forward options to establish an independent commissioner to organize debates during future election campaigns. To inform the way forward, the Government consulted with Canadians, stakeholders and academia. These consultations revealed broad support for, and value in, the creation of a leaders’ debates commission. Moreover, many argued that such a commission should be guided by the public interest, and underpinned by openness and transparency in terms of the organization of debates and their participation criteria.

Design and implementation

The Government pursued a non-legislative phased approach, putting an entity in place in time for the 2019 election, while allowing for its initial experience to inform the potential creation of a permanent entity that could be put in place post-2019. To this end, the Governor in Council issued two Orders in Council (OIC), one that created the commission and set its mandate, and a second that appointed the Right Honourable David Johnston to the position of debates commissioner on the recommendation of the Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions.

Mandate

The core mandate of the commission was to organize two leaders’ debates, one in each official language, for the 2019 federal general election and to subsequently present a report to parliament on lessons learned with recommendations for future election cycles.

Participation criteria: In creating the commission, the Government established criteria for participation by political party leaders. To take part in the debates organized by the Commission, leaders of political parties had to meet two of the following criteria: (1) have a Member of Parliament, elected as a member of that party, in the House of Commons at the time the election is called; (2) intend to run candidates in at least 90% of electoral districts; and (3) either obtained 4% of the vote in the previous election, or have a legitimate chance to win seats in the upcoming election based on recent political history, current public opinion polls and previous election results.

Report on 2019 leaders’ debates: Following the 2019 general election, the commission is required to produce a report outlining its findings and providing advice regarding various models, including both legislative and non-legislative, for the potential creation of a permanent debates commission. The report is to be submitted to you no later than March 21, 2020, although it is anticipated it will be completed before this date.

Legislative and policy considerations

Parliamentary environment

On March 19, 2018, after hearing the testimony of over then 30 witnesses, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (PROC) tabled its final report entitled: The Creation of an Independent Commissioner responsible for Leaders’ Debates. While the mandate of the debates commission aligned with most of PROC’s recommendations, opposition members of the committee strongly criticized the non-legislative approach that was taken. While all parties praised the nomination of the Right Honourable David Johnston as Debates Commissioner, the lack of consultation in the appointment process was also highly criticized.

PROC will likely study the commission’s final report and provide recommendations to the government to inform the way forward. A Government Response may be requested from the Committee.

Broadcasting considerations

In setting the mandate of the Commission, [ * ]

[ * ] Additionally, early reporting demonstrates a significant increase in viewership on a variety of platforms.

Resilience [ * ]

[ * ]

Other considerations

The final report of the Commission will likely include additional policy and legislation considerations that may be taken into account in informing the future of leaders’ debates in Canada. [ * ]

On August 12, 2019, the Debates Commissioner extended invitations to participate in the debates to five out of six Canada’s main political parties. The Commissioner noted that while the People’s Party of Canada (PPC) did not yet meet two out of three of the participation criteria, it invited the party to submit a list of three to five ridings where it believed it would be most likely to elect a candidate. Following further analysis undertaken by the Commission—that examined party membership, fundraising and capacity, riding level polls, and media presence—the Commissioner extended the invitation to the leader of the PPC. The decision to extend an invitation to the leader of the PPC generated significant controversy across the country. While some argued that Mr. Bernier’s views incited hatred and intolerance, others felt that the Commission should stand by the principle of free speech.

Implementation

As the Commission has been established as a temporary entity, its mandate will end with the tabling of its final report to parliament. [ * ]

[ * ]

Issue

Consistent with the previous mandate, the Liberal Party of Canada election platform committed to moving forward with the new, non-partisan and merit-based Senate appointment process, and will update the Parliament of Canada Act to reflect the Senate’s new, non-partisan role.

Context

Power to appoint Senators

The power to appoint individuals to the Senate is vested in the Governor General. By convention, the Governor General summons individuals to the Senate on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The Constitution Act, 1867 sets out minimum qualification requirements that must be met by an individual being considered for a Senate appointment, whereby a Senator must:

- be appointed in respect of a province and, in the case of Quebec, an electoral division;

- be at least 30 years of age, and be less than 75 years of age;

- be a subject of the Queen;

- own real property of a net value of $4,000 in the province for which he or she is appointed;

- have an overall net worth of $4,000 in real and personal property;

- be resident in the province for which he or she is appointed; and

- in the case of a Senator appointed to represent one of the 24 electoral divisions in Quebec, own his or her real property, or be resident, in that electoral division.

Responsibilities for the Senate

Responsibilities for the Senate are shared; these areas are briefly highlighted below:

- As mentioned above, the Prime Minister provides advice to the Governor General on individuals to be appointed to the Senate.

- As Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you are the policy lead for the Senate, including, particularly in relation to the independent appointments process.

- The Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, is responsible for managing the overall legislative agenda of the Government and also maintains legislative authority for the Parliament of Canada Act. The Act provides the overall framework for the operation of Canada’s Senate and House of Commons, including the privileges, immunities and powers of the Senate and House of Commons, as well as the remuneration of Senators and Members of Parliament.

- The Government Representative in the Senate (formerly the Government Leader in the Senate) represents the Government to the Senate and the Senate to the Government. Appointed by the Prime Minister, the Government Representative in the Senate attends Cabinet meetings as appropriate to discuss the legislative agenda and Senate renewal.

- The Senate is the master of its own proceedings, subject to the limitations of the Constitution and the law, and consequently can amend its rulings and proceedings to reflect evolving circumstances and needs.

Current composition of the Senate

On December 3, 2015, the Government announced the establishment of a new, non-partisan, merit-based process for Senate appointments. Under the new process, the Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments (IABSA) was established to provide advice to the Prime Minister on candidates for the Senate.

The introduction of the independent appointments process brought significant changes to the composition of the Senate during the 42nd Parliament, with independent Senators constituting the majority of its members for the first time in its history. Since January 2016, 50 senators have been appointed to the Senate through the advisory board process. All but one2 of these Senators initially joined the new Independent Senators Group (ISG), which formed in March 2016 to provide a vehicle for non-partisan senators to advocate for funding and committee memberships.

On November 4, 2019, 11 Senators – nine from the ISG and two from the Conservatives – announced that they are forming a new group in the Senate, called the Canadian Senators Group (CSG). In a press release announcing its formation, the CSG describes itself as a caucus of “like-minded senators who are determined to maintain a high standard for the review of legislation and committee studies.” The CSG has also said they will cap membership at 25 to ensure a less cumbersome operation.

On November 14, 2019, the Senate Liberals caucus announced it was disbanding to form a new entity called the Progressive Senate Group. According to interim leader Senator Joseph Day, the only requirement for seeking membership is that members must support progressive politics and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and are committed to advancing reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. The new group stated that it was hoping to attract new members before it drops below the requirement for recognized groups, which was expected to be early in 2020.

Following these events, however, on November 18, 2019, it was announced that two additional senators – Senator Jean-Guy Dagenais from Quebec and Senator Percy Downe from Prince Edward Island – have joined the Canadian Senators Group. With Senator Downe’s change in membership to the Canadian Senators Group, the Progressive Senate Group is no longer a recognized group in the Senate. As such, members of the new Progressive Senate Group have been marked as non-affiliated and are expected to lose funding and committee seats when Parliament resumes, unless new members are recruited to this group.

With 105 members in total, as of November 19, 2019, the Senate is comprised of 51 ISG senators, 24 Conservative senators, 13 CSG senators, and 12 non-affiliated senators. There are also five vacancies, including one in British Columbia, one in Saskatchewan, one in New Brunswick and two in Quebec.

Further details on the projected Senate vacancies – based on mandatory retirements – that will take place from 2019 to 2023 are provided in Annex A. Additional vacancies could also result from time to time should a Senator wish to resign from the Senate before the mandatory retirement age of 75.

Considerations

Amending the Parliament of Canada Act

The Government committed during the last parliamentary session and in the 2019 Liberal Party of Canada election platform to updating the Parliament of Canada Act to reflect the Senate’s new, non-partisan role. [ * ]

Responsibility for the Parliament of Canada Act lies with the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, [ * ]

It can be expected the ISG will continue to press for legislative action in the upcoming parliamentary session, which was an important issue for the ISG at the close of the 42nd Parliament. Their position was reiterated in an August 2019 editorial, whereby ISG facilitator, Senator Yuen Pau Woo, and deputy facilitator, Senator Raymonde Saint-Germain, argued that further reform efforts must include changes to the Parliament of Canada Act to recognize groups other than the government and the opposition.

Non-legislative options to strengthen the Senate’s independence

As Minister responsible for Democratic Institutions, you could play a facilitating role in a number of non-legislative changes that could be introduced to reinforce the Senate’s transition towards a less partisan chamber.

[ * ]

Senators have also called for a non-legislative Senate Speaker election process, one that is within the current constitutional framework. Given its appointed nature, the Speaker of the Senate has been criticized as a partisan position. Proponents of an elected Speaker have argued that an elected Speaker would be more independent of the Government, and would make the Senate a more democratic institution.

Further, the Government Representative Office in the Senate has proposed the introduction of a business committee. The purpose of this committee would be to manage and streamline the parliamentary process, including the debating and voting schedule for bills.

Impact on the parliamentary process

The Government’s reforms had a considerable impact on the parliamentary process in the 42nd Parliament. The first two years of the previous mandate were one of transition – with a significant cohort of newly appointed senators learning and adapting to their new legislative responsibilities within a new environment of independence, as well as the creation of the ISG and the subsequent changing of rules and procedures to allocate resources to this new group.

As the mandate advanced, Senators began to show a strong willingness to study, debate and propose amendments to legislation. Overall, more than 400 amendments covering 34 government bills were proposed by the Senate in the 42nd Parliament, with more than 60 per cent accepted by the House of Commons. The exception to this changing approach to legislative review has been Conservative Senators, who continue to sit as members of the Conservative caucus and have continued to use partisan tactics in reviewing and amending legislation.

[ * ]

Federal-provincial-territorial issues

One of the Senate’s fundamental roles is to serve as a chamber for the representation of regional interests and as such, provinces and territories have historically given careful consideration to the Senate, particularly to proposals or attempts to reform the institution. [ * ] An outline of provincial and territorial engagement efforts to date, as well as an update on memberships for the IABSA, has been provided in Annex B.

Implementation

The Government had previously indicated its intent to work collaboratively with the Senate on any initiative that would support the Senate’s evolution to a non-partisan chamber. [ * ]

Annex A: Projected Senate vacancies

As of November 19, 2019, the composition of the Senate is as follows:

- Independent Senators Group: 51

- Conservatives: 24

- Canadian Senators Group: 13

- Non-affiliated: 12

- Vacancies: 5 (one in British Columbia, one in Saskatchewan, one in New Brunswick and two in Quebec)

The following table outlines the projected annual and cumulative Senate vacancies through 2023, assuming vacancies arise only from mandatory retirements. All provinces will have at least one vacant seat over the next four years and Nunavut will have one vacancy in 2023. The exception to this will be Yukon and the Northwest Territories, which will have no vacancies.

| Province | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Neufeld (C) | 0 | 0 | 0 | Campbell (CSG) |

| Alberta | 0 | 0 | McCoy (CSG) | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | Andreychuk (C) | Tkachuk (C) Dyck (N-A) |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| Manitoba | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bovey (ISG) |

| Ontario | 0 | Eaton (C) | Munson (Lib) | Ngo (C) Weston (ISG) |

0 |

| Quebec | Demers (ISG) Pratte (ISG) |

Joyal (N-A) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Brunswick | McIntyre (C) | Day (N-A) | Olsen (C) | 0 | Lovelace-Nicholas (N-A) |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | McInnis (ISG) | 0 | Mercer (N-A) | 0 |