Archived - Balancing Oversight and Innovation in the Ways We Pay: A Consultation Paper

This consultation paper seeks views from all Canadians on the oversight of national payment systems. Core clearing and settlement systems are currently subject to regulation and oversight for safety, soundness and efficiency purposes. However, this oversight does not fully extend to national retail payment systems. As a result, these systems are not currently subject to comprehensive and consistent rules that protect consumers and ensure public confidence in the use of electronic payment methods.

Respondents are encouraged to respond to the questions highlighted in this consultation paper. Views gained from this consultation process will be used in developing policies on the oversight of retail payment systems.

Comments should be received by June 19, 2015. Please note that the initial deadline of June 5, 2015 has been extended by an additional two weeks to provide more time for respondents to submit their comments.

We encourage readers to send comments electronically to paymentsconsult@fin.gc.ca.

Written comments can be submitted to:

Lisa Pezzack

Financial Sector Policy Branch

Department of Finance Canada

90 Elgin Street, 13th Floor

Ottawa, ON K1A 0G5

By submitting a response to this consultation you consent that all or part of your response may become public and may be posted on the Department of Finance Canada website, unless otherwise stated. This is to add to the transparency and interactivity of the consultation process. Where necessary, submissions may be revised or redacted to remove sensitive information. Should you post all or part of your response on your website, you consent that the Department of Finance Canada may post either all or part of your response on its website, or provide a link directly to your website.

As the Department of Finance Canada may wish to quote from or summarize submissions in its public documents and post all or part of them on its website, we ask persons making submissions to clearly indicate whether they wish us to keep all or part of their submission or their identity confidential. If you make a submission, please clearly indicate if you would like the Department of Finance Canada to:

- Withhold your identity when posting, summarizing or quoting from your submission; or

- Withhold all or part of your submission from its public documents.

If you wish for all or part of your submission to remain confidential, you must expressly and clearly indicate this when submitting your document. However, persons making submissions should be aware that once submissions are received by the Department of Finance Canada, all will be subject to the Access to Information Act and may be disclosed in accordance with its provisions.

The current oversight of payment systems in Canada is focused on the core national payment clearing and settlement systems and, to a lesser extent, on retail payment systems supported by regulated financial service providers such as debit and credit card networks. This leaves other non-bank retail payment service providers without specific regulation or oversight, resulting in an inconsistent approach for addressing similar risks posed by the activities of different payment service providers. It can also create confusion for payment users, including consumers and businesses, who may expect similar levels of user protections irrespective of the payment method or service that they use. These issues were highlighted in the comprehensive review of the payments system conducted by the Task Force for the Payments System Review.[1]

This paper presents an overview of the Canadian payments landscape and risks, the Government's proposed oversight framework for the payments system, and key concepts for the oversight of national retail payment systems. It seeks views on the scope and nature of oversight of national retail payment systems.

Every year, Canadians make roughly 24 billion payments, worth more than $44 trillion. The movement of this money is vital to Canadian economic activity and Canada's prosperity.

Advances in information and communications technology are rapidly changing the way Canadians pay for goods and services.[2] Traditional paper-based instruments such as cash and cheques are increasingly being replaced by a variety of electronic payment methods such as electronic fund transfers, debit, credit and prepaid payment cards, and digital/electronic wallets.

The following charts show the trend in the use of cash, debit and credit cards at the point-of-sale in Canada between 1992 and 2012. Both the volume and value of transactions for each of those payment instruments are shown as a percentage of the total volume and value of cash, debit and credit card transactions.

Shares of point-of-sale transactions

[Shares of point-of-sale transactions - Text version]

Payments can also be initiated on-line, by means of telephone banking or via Automated Teller Machines. For example, utility bills are commonly paid using pre-authorized debits from the payer's bank account to the utility company's account. Both the volume and value of pre-authorized debits have increased steadily over the last decade. Direct deposits, which are widely used by businesses and government for payroll and social benefit transfers to individuals, are also increasing at a similar pace.

Technological advancements, along with increased demand by consumers and businesses for "anytime and anywhere payments" has led to the development of new ways to pay, including digital/electronic wallets that can be used for online and mobile payments. While these new methods of payment represent a relatively small share of total retail payments, their use is increasing rapidly. For example, the Canadian Payments Association has estimated that there were 24 million e-wallet/person-to-person transactions in 2011, worth nearly $10 billion, up from $3 billion in 2008.[3] The annual growth rate of these types of payments, in terms of volume, has averaged close to 40 percent over the same period. The use of virtual currencies as a means of payment has also been increasing in recent years.[4]

Technology is facilitating the entry of new players in payments. The prominence of traditional providers of payment services, such as banks and debit and credit card networks, is being challenged by non-traditional providers of payment services such as telecom operators, social networks and information processors. These payment service providers work together as part of a complex system of processes and infrastructure to deliver retail payment services. See Annex 1 for examples of retail payment methods, associated functions and services, and service providers.

In Canada, the federal government has responsibilities with respect to the oversight and regulation of payment systems that are national or substantially national in scope, or systems that play a major role in supporting transactions in Canadian financial markets or the Canadian economy.[5] Most retail payment systems used by Canadians, such as debit and credit card networks, fall within these parameters.

Given the importance of payment systems to the economy, the Government oversees their operation through stated policy objectives of safety and soundness, efficiency and consideration of user interests. Through these objectives, the Government seeks to have a payments system that responds to the needs of Canadian consumers and business in support of a vibrant economy. A policy framework that elaborates on the Government's objectives is outlined in Annex 3.

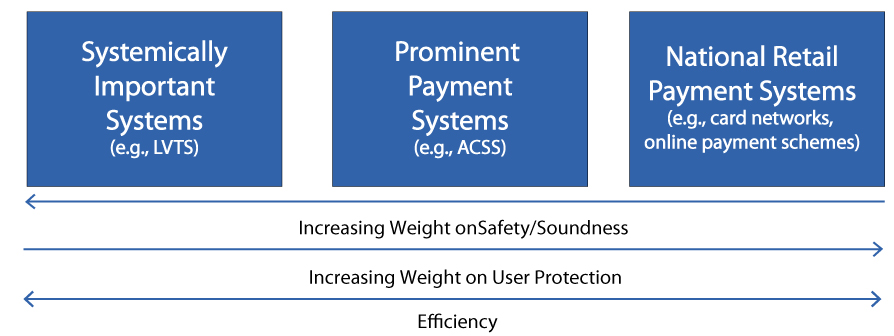

The Government has developed an oversight framework in which each system is assigned a place along a continuum according to the overall level of risk it poses to the economy. Figure 1 below illustrates this continuum.

Moving from the right to left on the continuum, the relative importance of the risks associated with a system changes from those related to user protection to risks of a potentially systemic nature. The balance of public policy objectives also changes accordingly. For instance, payment systems located to the right on the continuum would include smaller value, substitutable systems used to process retail payments where risks are primarily to consumer protection. At this end of the spectrum, the Government would emphasize the public policy objectives of users' interests and efficiency. Moving towards the left along the continuum, the severity of risks would increase, with potential impacts on the economy. At the far left are systemically important systems, which include the Large Value Transfer System. Safety and soundness would therefore be emphasized. The public policy principle of efficiency would apply across the spectrum.

The nature of the payment system categories and approach to oversight is explained in more detail below.

Systemically Important Systems

To date, oversight has focused on those systems where a disruption or failure has the potential to pose the greatest risks to Canadian financial stability and economic activity. This includes systemically important systems overseen by the Bank of Canada under the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act. The Department of Finance also has a role in the regulation of systemically important systems owned and operated by the Canadian Payments Association.

Prominent Payment Systems

Economic Action Plan 2014 announced the Government's proposal to amend the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act to expand the Bank of Canada's oversight to "prominent payment systems" (middle column of Figure 1), disruptions or failures of which have the potential to pose risks to Canadian economic activity and affect general confidence in the payments system. Initial analysis indicates that the Canadian Payments Association's Automated Clearing and Settlement System (ACSS), which is used in the clearing and settlement of various payment instruments such as cheques, debit card payments and automated fund transfers, has the potential to pose such risks. In 2012, the ACSS cleared over 6.5 billion payment items with a value of almost $5.8 trillion, which is much higher than the value cleared through retail payment systems such as the credit card networks. In addition, there are no substitute systems to the ACSS.

National Retail Payment Systems

In contrast, national retail payment systems (right hand side of Figure 1) process lower transaction values and because they have some redundancy, a shock or disruption in a single system would have a limited impact on individuals and businesses, and would be unlikely to affect the Canadian financial system and economy. For this category of systems, the cost of a disruption is largely born by the direct users. As such, oversight in this category should be focused on addressing risks to end-users through measures that mitigate potential harm to their interests as a result of system failures or questionable market conduct.

Another characteristic of national retail payment systems is that they operate within a sector that is generally more competitive, which is an important driver of innovation and is reflected in the various retail payment options that are available to consumers to pay for goods and services. While competition and innovation often result in greater efficiency, some market dynamics in the retail payments sector can lead to inefficiency. For example, market concentration by a small number of payment service providers may generate economies of scale but it can also create barriers to entry for new providers and lead to higher costs for payment users. By promoting balance between various payment service providers in the retail payments sector, oversight can play an important role in achieving greater efficiency.

The Government is seeking views on how to define the category of national retail payment systems (right hand side column of diagram) for the purpose of oversight. Notably, the Government is seeking input on the types of risk that should be addressed by oversight measures, and the payment systems and payment service providers that would fall within the scope (i.e., perimeter) of oversight. Once these issues are clearly defined, consideration then needs to be given to the nature of oversight and how it would be implemented. These elements are explored in more detail below.

Effective oversight of retail payment systems can help mitigate the principal risks to users of retail payments. These risks can be classified under three broad categories: risks related to the operation of the systems, risks related to market conduct and risks to efficiency.

Operational Risk

Operational risk results from inadequate or failed internal processes, system failure, human errors or external events related to the activities of a payment service provider. It often arises due to weak governance and risk-management practices and can affect the availability, reliability and security of payment services. The sources of operational risk are wide-ranging and can include the lack of system redundancy (e.g., back-ups), poor data security, inadequate policies and standards with respect to user privacy, and, in some cases, financial risk to users when funds held on their behalf are not properly held or safeguarded.

Market Conduct Risk

The behaviour of payment service providers with respect to the markets they serve can be another important source of risk for users of retail payments. A key example is the information about a system's operation that is provided to users when they sign up for a new service or during subsequent use. The level and quality of transparency and disclosure is generally decided by each payment service provider, which can leave payment users with incomplete or convoluted information about basic elements such as terms and conditions, fees, and error correction and dispute settlement procedures.

Other market conduct risks concern business practices that may not be fully understood by many payment users but can have important implications for them, such as procedures for unauthorized or mistaken payments and "on-us" transactions. "On us" transactions include payments made between clients of the same financial institution, which are not subject to protections afforded by rules of the Canadian Payments Association.

When disputes arise between payment users and service providers, it is important to have effective dispute resolution and redress mechanisms in place. While many payment service providers offer some form of dispute resolution mechanism to their customers, there are no minimum standards to ensure that these mechanisms are well designed and offer effective and timely redress to payment users. This poses risks to users and can have a negative impact on confidence in the use of retail payment systems in general.

Efficiency Risks

There is generally meaningful competition in the retail payment sector and while competition usually supports efficiency, certain market dynamics are at play that can create inefficient outcomes for users. One example is network effects which can potentially lead to considerable market concentration and anti-competitive behaviour. In turn, this can result in higher costs for payment users and barriers to entry for other payment service providers.

While the Canadian retail payments landscape is marked by many instances of innovation, oversight measures designed to protect users of the payment system, as well as the integrity of the system, could strengthen the conditions for an innovative and competitive payments sector. By enhancing confidence in the system, oversight can support greater usage of efficient electronic payments and have a positive impact on innovation.

The following table summarizes the main types of risk that can be present in retail payment systems and provides examples of oversight measures that are used to mitigate these types of risk. The list of measures is non-exhaustive and is meant to provide examples of different elements that could be included in an oversight vehicle or arrangement in order to address various types of risk.

Key Risks in Retail Payment Systems

| Policy Objective | Types of Risk | Examples of Oversight Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Safety and soundness | Operational |

|

| Efficiency | Lack of competition, barriers to entry and high service costs |

|

| End-User Interests | Market Conduct |

|

Are the identified risks posed by "national retail payment systems" comprehensive. Should other risks be included?

Are there other measures that should be considered to address these risks?

How should the Government balance the need to mitigate risks with the objectives to promote innovation and competition in the payments sector?

To ensure that customers making payments within a single financial institution benefit from the same protections provided to payments between institutions, should the application of CPA rules that protect customers be extended to "on-us" payments?

The current oversight of payment systems is partly based on an institutional approach where certain organizations, such as banks and card networks, are subject to rules that do not apply to other organizations, even those which may perform similar activities. This can create imbalance in the market and pose risks to payment users as some organizations are left outside the scope of oversight.

The Task Force for the Payments System Review recommended a functional approach to oversight, such that risks related to particular payment instruments or functions would be treated similarly regardless of what type of organization provides the payment activity. This approach has been adopted in other jurisdictions. For example, Australia has put in place an ePayments Code that focuses on non-business electronic transactions and incorporates a list of several payment instruments (e.g., debit cards, prepaid cards, mobile devices) and payment methods (e.g., point-of-sale, telephone, online) to define its scope. The US Electronic Fund Transfer Act – Regulation E focuses on electronic fund transfers from a consumer's asset account initiated through different methods, including electronic terminals (e.g., point of sale and ATMs), telephone or computer. The Electronic Fund Transfer Act contains various exceptions, including with respect to intra-institutional transfers, wire transfers and funds used in the purchase or sale of securities. In the EU Directive on Payment Services, the focus is on the type of payment services offered. The Directive uses a list to exclude certain services from coverage (e.g., payments between settlement agents, money exchange businesses and technical services).

Should oversight be based on a functional approach, where risks are assessed by payment activity and treated similarly regardless of the provider?

What payment functions or instruments should be brought within the scope of oversight?

Once the risks to address and the perimeter of the national retail payment systems category are established, the nature of oversight and how to implement it needs to be addressed. Different arrangements have been employed to implement the oversight of payment systems. For example, the core national clearing and settlement infrastructure, such as the Large Value Transfer System, is subject to legislation and regulations under the Canadian Payments Act and the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act. Other payment systems, such as credit and debit card networks, voluntarily abide by codes of conduct. The Canadian Code of Practice for Consumer Debit Card Services and the Code of Conduct for the Credit and Debit Card Industry in Canada are examples of codes that apply to retail payment systems and have been effective in addressing market conduct and consumer protection issues. However, sometimes voluntary codes need to be supported by legislation to strengthen adherence and compliance.

While there are different arrangements that can be used, some arrangements may be more appropriate than others to address retail payment system risks. For example, codes of conduct may be better tools for addressing market conduct risk, as they are more flexible than legislation and can be adapted more easily to evolving user needs and fast-paced technological innovations, such as those seen in the retail payments sector. Generally, codes of conduct also benefit from more industry collaboration and favour the spirit of the rules, as opposed to the letter of the law.

Other risks, such as operational and financial risk, may require stronger measures to ensure that industry abides by rules or standards. For example, measures to protect the funds of individuals that are held by payment service providers may require legislation to prevent any ambiguity as to the way funds should be secured. Legislation, with complementary regulation, is a strong tool that has the advantage of enforceability and transparency. It can, however, be rigid and relatively difficult to amend in light of market developments; for example, the Bills of Exchange Act, which applies to paper-based payment methods (e.g., cheques), is an example of legislation that has not kept apace with the shift towards electronic payments.

If the legislation of certain measures was to be pursued, the mandatory registration or licensing of payment service providers could also be considered, as it allows for closer monitoring of the industry, supports compliance and removes legal ambiguity as to which providers would be subject to the legislation.

Depending on the perimeter of oversight, and the risks that it seeks to address, it is conceivable that a combination of different arrangements could offer a superior outcome than could be achievable under a single arrangement.

What should be the key priority areas in developing oversight for retail payment systems?

Through what form of arrangement(s) should oversight be implemented (e.g., legislation, code of conduct)?

The evolving nature and complexity of retail payment systems requires dialogue between the Government and stakeholders to ensure the development of efficient policies that meet the expectations of Canadians. As part of these consultations, the Government intends to leverage existing stakeholder advisory mechanisms, including the Finance Canada Payments Consultative Committee (FinPay), but is also seeking broader views outside of this committee to allow the opportunity for everyone to provide input on the future of the Canadian payments system.

The Government invites all stakeholders to participate in these consultations. By working together we can ensure that the Canadian payments system responds to the needs of consumers and businesses and evolves to support the competitiveness of the Canadian economy.

Examples of Retail Payment Methods, Functions and Service Providers

| Payment Method | Examples of Functions/Services | Examples of Service Providers |

|---|---|---|

| Payment Cards (debit, credit and prepaid) |

|

|

| Digital Wallets |

|

|

| Electronic Fund Transfers |

|

|

| Virtual/Crypto Currencies |

|

|

The general legal framework for the Canadian payments system involves both public law and private law. Public laws are statutes that have compulsory application and are designed to promote the public interest. These include the Canadian Payments Act, the Payment Clearing and Settlement Act, the Bank Act, the Bills of Exchange Act, provincial securities laws and federal and provincial consumer protection laws. Other laws of broad application applicable to payments include the Competition Act,the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act.

Private law establishes the legal framework of voluntary arrangements and has been created to define and promote individual responsibilities and rights. This law includes property law, commercial law and contract law. It relates to, among other things, the autonomy of contracting parties, the liability for contractual commitments and good faith in mutual relations. Since many issues pertaining to retail payments are not addressed in public law, there is significant reliance on contractual agreements between payment users and service providers.

The following are some of the most relevant legislation and voluntary standards that apply to payments in Canada.

Canadian Payments Act

The Canadian Payments Act (CP Act) establishes the role of the Canadian Payments Association (CPA) and the Minister of Finance in the Canadian payments system. The CP Act specifies that the CPA's mandate is to establish and operate national systems for the clearing and settlement of payments, facilitate interaction between its clearing and settlement systems and other systems, and facilitate the development of new payment methods and technologies. The CP Act also authorizes the CPA to set rules that govern the daily operations of participants in its national clearing and settlement systems.

The CP Act provides certain oversight powers to the Minister of Finance with respect to payments systems and the CPA. These include approval and directive powers regarding by-laws, rules and standards set out by the CPA and any other payment system designated for such oversight under the Act.

Payment Clearing and Settlement Act

The PCSA gives the Bank of Canada responsibility for the oversight of payment clearing and settlement systems in Canada for the purpose of controlling systemic risk. In doing so, the Bank of Canada applies standards, including the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures to systemically important payment systems.[7] The Bank of Canada's oversight is focused on ensuring risk is managed in systemically important systems in order to control risk to the Canadian financial system and promote its stability and efficiency. The Large Value Transfer System, which is used to settle large-value and time-critical Canadian-dollar payments, is a payment system currently subject to Bank of Canada oversight.

Bills of Exchange Act

The Bills of Exchange Act sets out the statutory framework governing cheques, promissory notes and other bills of exchange. This Act deals with matters such as what constitutes a valid bill of exchange and the rights and obligations of various parties to a bill, including provisions establishing liability in the event of fraud or forgery and liabilities in the event of the loss of an instrument.

Federal and Provincial Financial Institutions Statutes

The federal financial institutions statutes (the Bank Act, Trust and Loan Companies Act, Cooperative Credit Associations Act and Insurance Companies Act), coupled with legislation governing provincially-incorporated financial institutions, provide the statutory underpinnings of the Canadian financial system. These statutes regulate such matters as corporate ownership and business powers, and define many aspects of the relationships between financial institutions and their customers, the government and some government agencies. There are certain payments-related provisions that apply to the financial institutions subject to these statutes. For example, the Bank Act contains regulations with respect to credit conditions, disclosure and certain liabilities for credit cards.[8]

Payment Card Networks Act

The Payment Card Networks Act is the primary legislation governing all payment card networks in Canada. There are no regulations currently in force under this Act.

Canadian Code of Practice for Consumer Debit Card Services

The Canadian Code of Practice for Consumer Debit Card Services is an industry-led initiative that establishes minimum levels of consumer protection in debit card arrangements. This Code was developed and revised through consultation among consumer groups, financial institutions, retailers and government. It is voluntary and not legally binding on organisations that endorse the Code. The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada monitors compliance with the Code.

Code of Conduct for the Credit and Debit Card Industry in Canada

The Code of Conduct for the Credit and Debit Card Industry in Canada addresses issues related to the costs and conditions of accepting credit and debit cards. It also addresses the presence of competing domestic network applications on the same card and the issuance of premium credit cards.

The purpose of this Code is to ensure that merchants who accept credit and debit cards are fully aware of their payment card processing costs, have more pricing flexibility and can freely choose which payment options they accept. The Code, which is voluntary, applies to credit and debit card networks, issuers and acquirers. Compliance with the Code is monitored by the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada.

Policy Framework for the Canadian Payments System

Vision: The payments system responds to the needs of consumers and businesses in support of a vibrant economy.

| Objective | Principles | Targeted Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Safety and Soundness | ||

| With regards to payment systems, safety and soundness refers to how payment systems measure, manage and control risks appropriately, taking into account legal risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, and business risk. Safety and soundness are essential conditions to achieve a stable financial system and a well- functioning economy. Given the potential to transmit negative shocks, payment systems must be operated with appropriate regard to safety and soundness. |

Risks should be identified and managed to preserve and promote financial and economic stability. Public sector oversight should contribute to public confidence in payment systems. Payment systems should be subject to oversight that is tailored to the risks they pose to the economy. |

All material risks to safety and soundness (e.g., legal, credit, liquidity, operational and business risks) are identified, measured and managed appropriately through governance arrangements and risk management. Emerging risks from new systems and providers are identified, monitored and subject to oversight when appropriate. Principles and best practices of governance support the development and operation of national payment systems. Canadians have confidence in payment systems. |

| 2. Efficiency | ||

| Payment services are delivered through a complex network of processes and infrastructure, supported by a number of intermediaries. Efficiency in payment systems includes how effectively the payment, clearing and settlement processes are carried out to meet end-users' needs, as well as ensuring the efficient allocation of resources to deliver the service. | Government policies should foster competitive market conditions and help remove barriers to entry. Market forces and competition drive cost reductions and innovation. In the presence of network effects authorities should foster a balance between competition and cooperation among participants and service providers. |

The evolution of the national payment infrastructure is responsive to the needs of Canadians. Access to the core national payment clearing and settlement infrastructure is based on objective requirements. No network or participant abuses market power. Technical standards are established and adopted to facilitate inter-operability of domestic and international payments systems and services and help reduce cost. |

| 3. Meeting the needs of Canadians[9] and protecting their interests | ||

| Payment systems must be designed and operated to meet the needs of Canadians and protect end-user interests which include convenience and ease of use, price, safety, privacy and effective redress mechanisms. Disclosure of price, risks and performance standards is important to enable Canadians to make informed choices. End-user interests are not homogeneous and are reflective of a wide range of needs and customer profiles. | Payment systems should operate to the benefit of end-users and foster economic growth. End-user protection should be adequate and consistent across all payment systems. |

Canadians have access to a range of convenient and affordable alternatives to effect timely payments. Disclosure and transparency in pricing and performance standards allows users to make informed choices. There are no undue barriers to end-users switching between providers. Consumers have access to effective redress mechanisms. Personal and transactional information is protected. End users have an effective channel to participate in the development of payment systems. |

[1] Task force for the Payments System Review

[2] While there is no standard definition for retail payment systems, they are used for the majority of payments to and from individuals and between individuals, businesses and public authorities. There are several retail payment instruments (e.g., cash, cheques, debit and credit cards, electronic fund transfers) and one instrument can often be used to substitute for another. Retail payments are also associated with higher volumes and lower average values than payments processed through the Large Value Transfer System.

[3] Canadian Payments Association, Examining Canadian Payment Methods and Trends, October 2012 - [PDF 667 Kb]

[4] Virtual currencies are a form of unregulated digital money not issued or guaranteed by a central authority, which can act as a means of payment. They are usually accepted as a means of exchange among the members of a specific group or community (i.e., acceptance is generally limited). While they began as a means to pay for digital goods (e.g., online games), they are now increasingly being used to pay for goods and services at physical retail outlets, restaurants and entertainment venues. The most advanced type of virtual currencies use cryptographic techniques to issue and identify currency (e.g., Bitcoin), and to verify transactions in order to prevent forgery. Unlike traditional electronic payment instruments, virtual currencies are not directly linked to a bank account that keeps a record of the owner's identity.

[5] Canadian Payments Act, section 37.

[6] Adapted from the Bank for International Settlements, Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems in the CPSS Countries, 2011.

[7] In 2012, the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems and the International Organization of Securities Commissions introduced the PFMIs which are new and more rigorous standards for payment clearing and settlement systems. See Principles for financial market infrastructures - [PDF 1.07 Mb]

[8] Bank Act, Cost of Borrowing (Banks) Regulations

[9] Includes consumers, businesses and governments, as well as participants and entities operating a payments system in their capacity as a business.