SFAC recommendations to the Government of Canada on removing barriers to increase private capital to net-zero and resilience solutions (2024)

January 31, 2024

Honourable Chrystia Freeland, PC, MP

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance

Honourable Steven Guilbeault, PC, MP

Minister of Environment and Climate Change

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Process Leading to Recommendations

Priority Areas of Focus

Challenges and Opportunities

Consolidated Takeaways, Recommendations and Next Steps

Conclusion

Dear Deputy Prime Minister Freeland and Minister Guilbeault:

Executive Summary

For Canada to achieve a net-zero and climate resilient economy by 2050, the Government of Canada estimates that $125–$140 billion of investment will be required annually.Footnote 1,Footnote 2 Federal, provincial, and municipal governments have each committed significant capital to decarbonization and adaptation policy objectives. More investment will be needed to achieve policy goals.

In May 2021, the Sustainable Finance Action Council (SFAC) was mandated to provide advice and recommendations to Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, and the Minister of Environment and Climate Change on, among other topics, strategies for aligning private sector capital with the transition to net zero. The SFAC subsequently convened a Net-Zero Capital Allocation Working Group (hereinafter referred to as the “Working Group”) to harness the expertise needed to deliver on this part of its mandate.

This report provides the SFAC’s recommendations to the Government of Canada t o better understand and thus remove barriers to increasing the flow of private capital to net zero and resilience solutions. To develop the recommendations, an initial assessment was conducted of decarbonization priorities to achieve a net-zero and climate resilient economy in Canada. This process identified five priority sectors to focus on : power, buildings, transportation, heavy industry, and agriculture, with an underlying focus on climate resilience across the economy. Barriers and opportunities related to increasing private sector financing of net-zero aligned decarbonization and resilience in these priority sectors were assessed. The i dentified barriers to investment generally derive from policy, revenue and/or cost uncertainty, resulting in investment opportunities being assessed as too risky or unable to generate sufficient returns. There are several mechanisms by which targeted action by the government could provide greater certainty, mitigate some risks, and increase investment returns to promote greater deployment of private capital.

As will be discussed further below, the SFAC recommends that steps be taken to:

- Evaluate and overcome awareness, data collection, and coordination challenges on environmental and social benefits and impacts of investment;

- Identify opportunities to bundle or aggregate net-zero or climate resilience-aligned projects, facilitating identification of investment opportunities and creating opportunities for sustainable finance;

- Contribute to carbon pricing certainty for emerging technologies;

- Accelerate the design and implementation of blended finance, including concessional capital and risk guarantees, in partnership with private sector investors, to identify and fund net-zero aligned investments; and,

- Promote and incentivize Indigenous participation in project development and ownership.

Introduction

The SFAC is composed of the twenty-five largest financial institutions (FIs) and pension funds in Canada, which together represent more than $10 trillion in assets. The Council was created to advise the Government of Canada on how to attract and scale sustainable finance. Council members recognize the imperative of the climate transition and are motivated to support the government’s effort to transition to a net-zero and climate resilient economy through, among other actions, increasing their lending and investments in support of these objectives. SFAC members seek to enable net-zero and climate resilience-aligned investment that will grow our economy, support innovative companies, bring good jobs to Canada, and lessen the physical risks of climate change while increasing our climate resilience and ability to adapt.

The Working Group was established in 2022 under the SFAC, with its primary goal to provide recommendations on how to mobilize private capital to support decarbonization and climate-related resilience in the Canadian economy. This work is intended to support the pursuit of a Net Zero by 2050 objective aligned with the Paris Agreement and Canada’s Climate Action Plans. The Working Group is governed by SFAC Chair, Kathy Bardswick, and Steering Committee Co-Chairs Dan Barclay (CEO, BMO Capital Markets) and Evan Siddall (CEO, Alberta Investment Management Corporation). To realize its mandate, the Working Group also collaborated closely with the First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC), Canadian Climate Institute (CCI), and Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) and sought input from groups such as the Net Zero Advisory Body (NZAB).

The analysis in this report focuses on how best to mobilize private capital to support decarbonization and climate resilience in the Canadian economy.Footnote 3 Central to this analysis is the recognition that private sector investment will accelerate to the levels required when the risk and return criteria of capital providers are met. As such, mobilizing private capital towards net-zero and climate resilience-aligned policy goals requires the creation of conditions where risk and return on investment are competitive and suited to the goals of capital providers.

In developing this report and its recommendations, climate resilience was assessed as a cross-cutting theme across all net-zero analysis. It was found that further work is required on defining mechanisms to direct private capital to financing climate resilience. As a result, this report focuses on financing the transition to a net zero economy.

The process for developing these recommendations, which have been informed by analysis done at the sector level, are found below. It is beyond the scope of this analysis to opine on how much additional government funding is needed to achieve a net zero and climate-resilient economy. The analysis takes into consideration the various programs developed by the Government of Canada to date. It also takes an agnostic approach to net-zero aligned pathways, relying on existing models to identify priority topics of investment.

We welcome the Ministers’ response to these recommendations and are available to provide further support and ideas for their implementation.

Process Leading to Recommendations

The Working Group executed its work in three phases. In Phase 1, the Working Group analyzed three reputable net-zero pathways to identify the emissions reductions and capital required to achieve net zero by 2050. In Phase 2, the Working Group analyzed investment case studies to identify the types of opportunities and challenges that exist for private sector investment in decarbonization and climate-related resilience. In Phase 3, the Working Group focused on consolidating learnings and developing recommendations to increase private sector investment.

The SFAC acknowledges that, to achieve net zero in Canada, substantial private sector investments are needed in all sectors of the economy. In Phase 1, the Working Group attempted to summarize each of the economic activities, key technologies and sector-agnostic enablers that would require investment. In Phase 2, the group prioritized a strategic approach over exhaustive coverage. This led to a decision to empower case study leads, allowing them to focus their work on specific and impactful case studies within their respective areas of expertise. While this approach naturally introduced variability between the case studies, it also allowed for more depth and precision in addressing the most pressing issues within our scope. The results are two-fold: first, the scope of the case studies differs from each other and, second, that further analysis would be necessary for a comprehensive assessment of net-zero investment needs.

Priority Areas of Focus

Leveraging existing research, the Working Group assessed an initial baseline landscape in Phase 1 that prioritized decarbonization approaches to achieve a net-zero and climate resilient economy in Canada.

For this work, the initial landscape review leveraged three generally accepted and existing net-zero pathways for Canada: The Government of Canada’s Long-Term Strategy (GoC LTS),Footnote 4 Trottier Institute (TI),Footnote 5 and the Canadian Climate Institute (CCI).Footnote 6 The full list of reports used for landscaping purposes is provided in Appendix 2.

All three pathways assume greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions from high levels of electrification, high use of renewable and zero-carbon alternative fuels, and potential use of nature-based or engineered CO2 removal technologies and sequestration to achieve negative emissions.

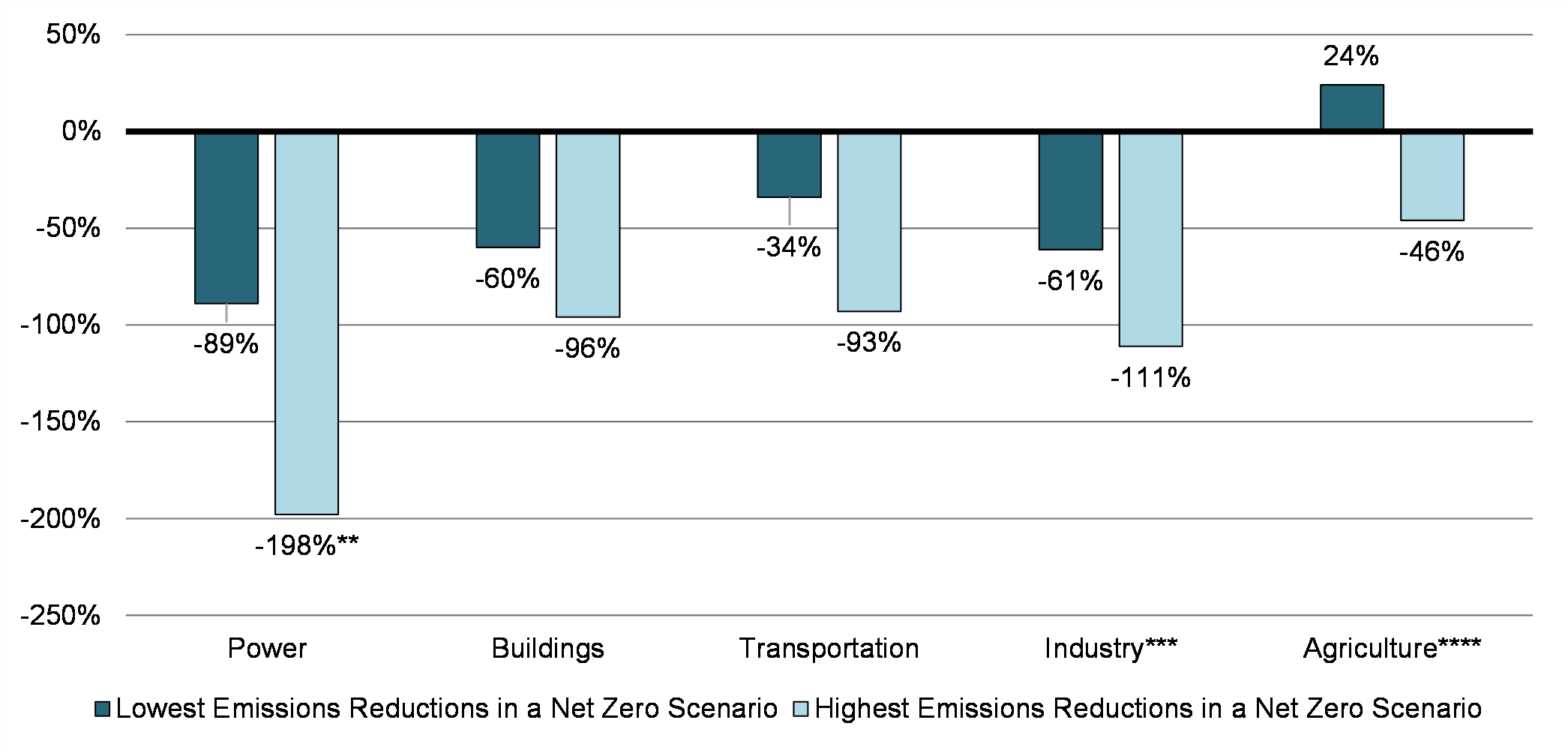

The level of GHG emissions reductions assumed in each pathway are summarized by sector in Exhibit 1 below.

Exhibit 1: Emissions Reductions Range in Canada by 2050 for Key Sectors

Compared to a 2020 Baseline

This review led the Working Group to focus on power, buildings, transportation, heavy industry, and agriculture as priority sectors.Footnote 7 These sectors accounted for 91.7% of GHGs in Canada in 2021 and will have the greatest impact on decarbonization, considering the technological readiness and economic viability of solutions for the sector.Footnote 8,Footnote 9

The Government of Canada’s Budget 2022 projected the investment needed to achieve Canada’s net-zero goals to be $125–$140B annually through to 2050 (target for all of Canada, including businesses, households, government action, etc.).Footnote 10 These and other analyses reviewed likely understate the annual investment needed, based on limited data or scope of the assessment. For example, in some calculations, the estimated transportation investment needs only include costs related to subsidies for zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs) and biofuels, but exclude transformation costs related to innovation, infrastructure, and behavioral change.Footnote 11

Based on this landscape review, the Working Group turned its attention to understanding the barriers and opportunities related to private sector financing of net-zero aligned decarbonization and climate resilience in the Canadian economy.

Challenges and Opportunities

The Working Group split into distinct workstreams to study each of the priority sectors and identify and review “case studies” to illustrate investment challenges and opportunities. Case studies were not intended to be comprehensive, but rather indicative of issues that would need to be addressed to promote more private sector investment. One limitation of this approach is that case study leads agreed to focus on a particular sub-sector within a larger sector and did not analyze or make recommendations on all the potential levers available within the broader sector.

Each workstream reviewed the emissions profiles, decarbonization pathways, technologically feasible investment opportunities, and potential policy-driven enablers and financing approaches for their respective sectors. While not the focus of the analysis, the Working Group further analyzed sector-agnostic decarbonization enablers such as the supply of critical minerals, battery production, the role of hydrogen, and the role of carbon capture and storage. Additionally, a carbon markets working group considered opportunities to utilize carbon markets and carbon pricing to incentivize decarbonization investment.

The topic of resilience was also examined, including priority areas for investment, existing policy enablers, current investment strategy, the outlook for physical climate risk, as well as barriers and challenges to investment.

A summary of the case studies for each of the priority sectors is outlined below:

Power

All net-zero aligned scenarios assume GHG reductions will be achieved from a high level of electrification of the economy. This will require increased supply of clean electricity. Renewable energy technology is relatively mature and many projects are commercially ready. As such, investment in the power sector, particularly clean power,Footnote 12 is a priority area for net-zero aligned investment.

Barriers to investment include high upfront costs with longer payback periods, lack of revenue certainty, and scarce transmission capacity. Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) were identified as essential to overcoming these barriers. PPAs provide revenue certainty for the developer of renewable power, provide cost certainty for buyers of renewable power, and allow projects to access low-cost debt and equity financing.

PPAs can be attractive to provincial utilities since the cost of power from these renewable energy projects can be lower than current legacy electricity generation costs in many provinces. However, procuring PPAs at the speed required to meet net-zero targets is a challenge for utilities. Other large commercial and industrial power users that would look to reduce their energy costs and Scope 2 emissions are unable to access clean power via PPAs due to balance sheet challenges and logistical constraints. Participation of the federal government in the PPA market as an active purchaser can bridge these challenges. Utilizing its procurement expertise and scale while respecting provincial jurisdiction, the Government of Canada can collaborate with utilities and other electricity buyers to support grid decarbonization while minimizing costs borne by ratepayers. The Government of Canada is uniquely positioned to begin a virtuous cycle that accelerates grid decarbonization, PPA demand, and clean energy investment from private investors.

SFAC recognizes that energy is largely under provincial jurisdiction and that the Government of Canada’s ability to support PPAs will vary across different provinces. SFAC suggests that the Government of Canada utilize its procurement expertise and scale to collaborate with utilities at every step of the procurement process. Further, SFAC conceives that this unique federal government role to be time-bound and focused on dovetailing with existing power systems. This would support generation activities so that utilities can focus on transmission, distribution, resilience, and a myriad of other priorities. The costs borne by ratepayers must also be comparable to costs they would otherwise be paying under a ‘business as usual’ scenario.

There are other barriers and challenges to a clean electrical grid beyond the generation of substantially more renewable energy. Upgrades of existing transmission lines and substations and the addition of new grid infrastructure, including battery storage and long-distance transmission, are needed to increase integration of clean energy into power grids. Increased renewable energy from projects procured by the federal government under PPAs provide clear visibility to utilities and regulators of upcoming transmission capacity requirements and enable increased investment into electricity grids by utilities.

Lower voltage distribution grids will also require investment by utilities to support increased electrification. Along with transmission and distribution investments, utilities must also be encouraged and incentivized to expand demand-side management strategies. Demand-side management creates a more efficient and reliable electricity grid and can reduce the need to build expensive new electricity generation capacity, thus reducing the market price of electricity for customers and freeing up financial resources for utilities to allocate to other investments. Analysis of these issues was beyond the scope of the case studies considered but should be the basis of study by utilities and government, with the goal of building cost-efficient resilient power systems.

Other challenges, such as lengthy delays in project approvals, could be addressed with more efficient permitting processes.

Buildings

Buildings currently account for 13% of Canada’s GHG emissions.Footnote 14 Modernizing existing assets and constructing new buildings consistent with net-zero standards is critical to meeting Canada’s climate change goals.

Research shows that the abatement potential of buildings is high, and much of the emission reductions needed to decarbonize the sector is possible with existing technologies.Footnote 15 Despite the commercial availability of technology to implement retrofits, several barriers are limiting the uptake of retrofits at the scale needed. These barriers include high upfront cost of capital with longer payback periods, a lack of standardized financing and execution models , as well as loss of tenant income for tenanted buildings during retrofit projects.

Blended finance has been successfully applied to the financing of retrofits, but not at the scale needed.Footnote 16 Under a blended finance model, low-carbon retrofits that qualify for certification under an approved framework (i.e., the Canada Green Building Council’s Investor Ready Energy Efficiency (IREE) or Zero Carbon Building standards (ZCB)) will have access to concessional finance. The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) is one of the most significant players in this space. Through their Building Retrofits Initiative (BRI), building owners or aggregators can access retrofit loans at below market rates. To access this capital, certain GHG emission reductions per dollar loaned is written into the lending documents.

One limitation with the BRI is that there is a minimum loan size of $50 million (previously $25 million), which makes it challenging for some building owners to meet the prerequisites. This is where CIB is leading by example in creating a retrofit financing partnership with a large Canadian bank, where participating building owners who, on their own, would not typically qualify for loans from the CIB can access the financing needed to accelerate green building upgrades. Another option under the BRI is CIB’s willingness to work with aggregators and energy service companies (ESCOs) who can aggregate smaller projects, blend private investment with CIB debt and create turnkey retrofit solutions. Such investments help finance upfront capital costs of retrofits, which will be repaid through the sharing of energy savings over a period of 15–20 years.

The solutions illustrated above all require higher quality building-specific data than is currently held by the federal government, provincial governments, and utilities. Building retrofit projects include measurement and verification to be evidenced by building energy consumption data and, in some cases, building certification. This was reinforced in the SFAC recommendations to the Government of Canada on climate-related data issues. The report, which was submitted in December 2023, identifies the building sector as having critical data gaps, which is limiting private sector investment. Further, improved data also supports increased resilience of the building stock in terms of climate adaptation and mitigation. Opportunity exists for government at the federal and provincial level to play a coordinating role in developing and aggregating asset-level data on energy efficiency. This could be accelerated with alignment between the federal and provincial governments developing open and standardized data on building energy efficiency standards.

Decarbonization and resilience of residential real estate is the subject of grant programs. Scaling up private sector investment is a challenge, with bundling and aggregation of many smaller investment opportunities being necessary to create sustainable finance opportunities for larger investors. Retrofit programs that combine energy (e.g., heat pumps) and resilience (e.g., hail/fire-resistant shingles) could help scale the required investment more rapidly.

Transportation

Transportation contributes nearly 22% of Canada’s GHG emissionsFootnote 17 and is expected to become the largest source of emissions by 2030.Footnote 18 Research shows that the transition of passenger and light-duty vehicles to ZEVs alone can reduce >50% of emissions from the sector.Footnote 19 Policy and regulatory support and technological maturity of ZEVs are considered high; policy experts observe that some aspects of the transportation sector in Canada are already on a net zero by 2050 pathway, such as passenger/light-duty vehicles.Footnote 20

Despite rebates and other federal support, the most significant implementation barriers for ZEVs are the high upfront costs relative to internal combustion engine vehicles (ICE), demand uncertainty, materials supply constraints, the cost and supply of charging infrastructure, and electricity supply.

Blended finance in the transportation sector, including for commercial fleets, is one tool that can be leveraged to help accelerate the uptake of ZEVs and has been successful in some markets. For example, the Australian Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) has executed a Credit Intermediated Asset Finance Facility (CIAF Facility) structure that incentivizes customers of FIs to adopt more energy efficient and/or lower emissions technologies. In the case of transportation, the CIAF Facility has been applied to fully or partially fund discounted loan products that lenders can offer to customers for battery electric passenger and light-duty vehicles. The pre-agreed discount is then rebated to the lender by the CEFC. To minimize risk, the CEFC purchases a tranche of the lender’s bond under an existing bond program and funds the discounted rebate following receipt of bond coupon payment.Footnote 21 Lenders are encouraged to also provide their own discount to customers, on top of what CEFC delivers.

The CIAF Facility structure is considered to have a high degree of execution certainty, with no obvious barriers to lenders passing loan discounts through to customers to finance passenger and light-duty ZEVs. A similar blended finance model could be introduced in Canada. Given the Canada Growth Fund (CGF) and CIB mandates to offer concessional financing to support decarbonizing the transportation sector, opportunity exists for the government to collaborate with co-financiers to lower the cost of capital, particularly for commercial fleets and charging infrastructure. The CGF and/or CIB could purchase sustainable bonds of lenders and use interest earned to partially fund lending discounts. This supports the growth of sustainable debt markets while partially recouping the government funding.

There is a role for private sector capital to participate in co-financing using these approaches. While concessional lending can help accelerate consumer adoption of ZEVs and incentivize the deployment of private capital, it is important to recognize that enabling infrastructure and market conditions, including competitive upfront costs, supply chain certainty and reliable charging infrastructure, are critical in supporting consumer demand. Concessional lending could also be applied to accelerate the transition of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles to zero-emissions models once technological advances address the existing operational barriers.

Heavy Industry

The heavy industry sector consists of emissions from oil and gas, mining, smelting and refining, pulp and paper, iron and steel, cement, lime and gypsum, and chemicals and fertilizers, accounting for nearly 40% of Canada’s emissions.Footnote 22

Some heavy industry sectors are well advanced in electrifying their processes (e.g., iron and steel, mining). Other low-carbon technologies like carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) are less widely adopted but offer substantial decarbonization. In cases where the carbon price is either too low or too uncertain to provide a sound basis for investment decision-making, a reliable, stable, and ambitious (e.g., >$100/tonne) carbon price and market is crucial.

Challenges for decarbonization of heavy industry using CCUS include the absence of a revenue stream or lack of revenue certainty, uncertain return on investment, limited lending value due to variable carbon credit cash flow, as well as high upfront capital costs. There are also concerns related to lengthy delays in regulatory and permitting processes around transport and storage infrastructure.

Greater certainty could be provided through fixed pricing per-tonne investment tax credits on carbon capture and/or production tax credits, offsetting some of the investment risks. Given the long construction and payback period of these initiatives, projects would greatly benefit from an increase in the timeframe of the realized credits and/or the extension of the timeframe to qualify for the credit. Carbon contracts for difference (CCfDs), as introduced in the Canada Growth Fund, can also mitigate some of this risk. Additionally, more efficient streamlining of federal and regional permitting approvals will be key.

Certain heavy industry projects, along with power projects, have been identified as viable potential opportunities for financial partnerships with Indigenous communities. As part of the NZCAWG’s work, the First Nations Major Projects Coalition was engaged to better understand the opportunities and barriers for Indigenous groups to participate in both decarbonization and adaptation projects, including through equity ownership of projects, or parts thereof. The main opportunity that was identified was a national loan guarantee program. SFAC recognizes that the Government of Canada announced in the 2023 Fall Economic Statement that it plans to advance such a program with additional details to be shared in Budget 2024.Footnote 23 Despite this announcement, significant barriers exist for Indigenous communities in accessing capital for equity partnerships in major heavy industry projects. There is an opportunity to find solutions that advance economic reconciliation through participation and ownership in net-zero projects.

Agriculture

The agriculture sector was the fifth largest source of GHG emissions in Canada, accounting for 10% of national emissions in 2021.Footnote 24 Key technologies and management solutions that can reduce emissions in agriculture include agroforestry, feed additives, anaerobic digestors, and climate smart practices (e.g., cover-cropping, nitrogen-efficient crops, no-till/reduced-tillage, and fertilizer optimization). By engaging these technological and management solutions, and mobilizing finance and policy support to farmers, Canada could reduce up to 40% of potential 2050 emissions.Footnote 25 For example, cover cropping has the potential to mitigate 9.6MT of emissions, while biochar, which converts agricultural waste into a soil enhancer that can hold carbon, could cut 6.8MT of emissions.Footnote 26

Many Canadian farms are subject to volatility in commodity and input prices, which make the cost of transition investment challenging. Further, the investment in sustainable farming practices and equipment presents yield risk and is often too expensive for small- or medium-sized farms to obtain. Financing of on-farm emissions reductions, whether with public or private capital, also requires diligent measurements and auditable data collection, such as soil testing, which is currently a challenge for small farmers. Emissions data is a key enabler to help direct private capital in support of the decarbonization of agriculture. Due to the lack of agriculture data, lenders are currently not able to quantify their financed emissions and set targets for this sector. This hinders the ability of lenders to allocate capital to decarbonization initiatives in this sector. This challenge was also identified in SFAC’s recent recommendations to the Government of Canada on climate-related data gaps submitted in December 2023.

Educational and awareness-building initiatives play a crucial role in highlighting available government programs and lowering barriers to accessibility. Amplifying the promotion of such programs and making them more accessible, as well as supporting open and standardized data collection and measurement, would be beneficial.

Beyond existing government programs, potential approaches to support on-farm decarbonization and economic resilience include new funding to reduce interest rates for equipment purchases, loan guarantees, or tax credits that can encourage private capital to co-lend or co-invest. Expanding the Canadian Agriculture Partnerships crop insurance program to cover climate smart agriculture is also critical for the adoption of climate smart agriculture and would offset some of the risk related to yields, which could further facilitate private sector lending.

A well-functioning and credible carbon market could also increase climate smart agriculture uptake, with the generation of credits as a source of revenue for farmers and FIs. Barriers to this include the cost associated with generating credits, existence of relevant standards, and volatility and uncertainty of carbon credit pricing.

Resilience

It is projected that climate impacts could cost the Canadian economy $25 billion in 2025 alone, and $78 billion annually by mid-century, even in a low-emissions scenario.Footnote 27 Despite this, climate adaptation is relatively underfunded in Canada, amounting to only $6.5 billion in investment since 2015.Footnote 28 Scaling up resilience investments for adaptation will require a combination of both public and private sources of capital.

A key barrier for private finance is the challenges associated with quantifying, aggregating, and monetizing the benefits of adaptation infrastructure—for example, a seawall, river dikes or wetland—in a way that creates cash flows required for private sector investment.

It is evident that monetizing the benefits of resilience (e.g., through recognition of avoided costs, including reduced insurance premiums and claims, or fees directly or indirectly tied to usage or benefit) could incentivize more investment. Research suggests that every dollar invested in adaptation produces $13-15 in avoided direct and indirect costs.Footnote 29 While a large body of existing research focuses on the importance of transitioning to net-zero, it is imperative that practitioners continue to mobilize private capital specifically for adaptation projects. This includes quantifying, aggregating, and monetizing the benefits of adaptation infrastructure.

De-risking investment can be done with concessional capital and risk guarantees, which can be deployed from existing government programs. Additionally, government-led aggregation, bundling, and awareness-raising about the impacts of a changing climate on physical assets can create the critical mass necessary to attract larger scale private sector finance.

Carbon Markets

Businesses can participate in the carbon markets as sellers of carbon credits to monetize emission reduction projects and increase the availability of upfront capital for such projects. Many low-carbon projects rely on selling their carbon credits on the market as a revenue source to achieve economic feasibility.

Policy uncertainty, especially in the industrial sectors that expect to be both large purchasers and generators of carbon credits, presents a barrier to the stability of Canada’s carbon markets. Changes in government policy or regulations could significantly impact the market, in terms of the future carbon prices, the value of credits and overall trust in the market. This can be problematic for investments with longer payback periods. There is also a risk of pricing distortions in the market from the potential oversupply of offsets resulting from large decarbonization investments. To grow the carbon market effectively, it is important to focus on increasing the size and the ease with which different carbon credits can be exchanged. This can be achieved by connecting the carbon trading systems of different provinces and working with provincial governments and regulators to introduce new rules that allow for carbon credits to be shared more easily across the country.

I nternational carbon agreements (e.g., Article 6 of the Paris Agreement) could also be beneficial to encourage credible carbon markets. For Canada to meet its climate goals, businesses should be encouraged to buy carbon credits that are part of a fair international system. For example, if companies are purchasing internationally sourced offsets that do not come with a corresponding adjustment, then emissions reductions will not be accurately reflected. One option that could be considered is to have a rule that requires companies to buy carbon credits created within North America, though such an approach would have to be examined carefully (such analysis being beyond the scope of this report).

Consolidated Takeaways, Recommendations and Next Steps

Increased private sector investment requires competitive returns for the level and types of risk of the investment. As such, mobilizing private capital towards net-zero aligned policy goals, including climate resilience, requires the creation of conditions where risk and return for investment are competitive and suited to the goals of capital providers.

While new regulatory requirements could impact investment decisions, it was beyond the scope of this analysis to suggest or anticipate new regulation that could lead to greater investment.

The SFAC’s analysis has revealed that barriers to investment are often derived from uncertainty in terms of policy, revenue and/or cost, resulting in investment opportunities being assessed as too risky or unable to generate sufficient return. There are several mechanisms by which targeted action by government, including the Government of Canada, could provide greater certainty, mitigate some risks, and increase investment returns to promote greater deployment of private capital. Several opportunities are identified in the following sections.

Improved data collection and awareness on environmental and social benefits and impacts

Recommendation #1: Evaluate and overcome awareness, data collection, and coordination challenges on environmental and social benefits and impacts of investment.

Some decarbonization or resilience investments require information on baseline performance, plus tracking of impact during and following investment. For example, any investment in residential or commercial building decarbonization retrofits for net zero requires pre-retrofit and post-retrofit energy assessments, as would similar programs focused on reducing risk and bundling resilience. Investments in decarbonizing or increasing resilience of farms and agricultural operations would benefit from understanding the geolocation of farms and geospatial monitoring as well as expanding accessibility and affordability of soil testing. Decarbonization of heavy industry similarly requires an understanding of scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions of the industrial operation, both before and after investment. Labelled sustainable finance investment or financing typically requires this type of data, to support the tracking and reporting of emissions, in a way that helps meet market expectations and international standards.

Any effort to reduce the complexity, cost, and administrative burden of gathering and utilizing data would be conducive to private sector investment. As laid out in a December 2023 SFAC submission to the federal government on climate-related data issues,Footnote 30 the government can play a significant role in establishing standards and rules for measuring and quantifying environmental and social benefits, obtaining aggregated data from utilities providers or other sources, consolidating data sets, and making data available to potential investors and financiers.

The government and private sector must work together to adopt business case approaches that incorporate a variety of factors like regulations, incentives, ancillary benefits, and other external factors. A more detailed economic cost/benefit analysis should also be undertaken with respect to decarbonization and climate resilience. These types of activities can help overcome coordination challenges that impede sustainable finance flows into Canada’s net-zero transition.

Another area where the establishment of a common understanding would bring value is with regards to the Taxonomy Roadmap Report.Footnote 31 Promotion of an official green and transition taxonomy would establish a common baseline around the labelling of projects and would help specify what data is needed for entities or activities to be considered green or transition.

Government can, in partnership with the private sector, take more steps to raise awareness of not only the frequency and security of climate-related risks and associated damages, but also the investment opportunities, existing programs, and financing options to mitigate such risks. Doing so would provide greater alignment between asset owners, insurers, investors, the financial sector, and government agencies on the resilience impact of investment. Improved data is necessary to help all asset owners implement resilience measures. Communication and program delivery could be coordinated with FIs in relation to their clients, increasing awareness and ideally reducing administrative hurdles to accessibility of available financing programs. For example, within the agriculture sector, there is an opportunity to increase farmers’ access to information about the known benefits of climate smart agriculture and opportunities to generate carbon credits. For the buildings sector, a centralized communications hub explaining financing options could allow for a “one stop” information hub.

Lastly, there is an opportunity to more efficiently streamline federal and regional regulations related to permitting processes for infrastructure projects to accelerate projects in alignment with 2030 and 2050 timelines.

These recommendations are aligned and supportive of the SFAC’s Data TEG recommendations, particularly as it relates to recommendations A, B and D.Footnote 32

Bundling and aggregation of investment opportunities

Recommendation #2 – Identify opportunities to bundle or aggregate net-zero or climate resilience-aligned projects, facilitating identification of investment opportunities and creating opportunities for sustainable finance.

Many decarbonization or resilience investment opportunities are, individually, too small to attract substantial private sector capital. Whether it is the retrofitting of millions of homes and buildings, investing in flood defenses to protect Canadian communities of varied sizes, or accelerating the adoption of zero emissions vehicles and infrastructure for personal or commercial purposes, a resilient net-zero transition will require investments both big and small.

Programs like the Government of Canada’s Greener Homes Grant/Loan offer precedent for coordinated evaluation and verification of smaller scale green investments. Beyond housing, similar programs exist at the provincial level for ZEVs. This type of program can increase the efficiency of data collection and environmental attribute verification.

Leveraging experience developed through existing programs, as well as the expertise of crown corporations, such as the CIB, who actively develop offerings with the private sector, the SFAC recommends the Government of Canada proactively engage with the finance sector on how to bundle and aggregate decarbonization and resilience projects.

Green or sustainability bonds or other types of sustainable financing products could be used to mobilize investment capital to support such programs and spread the cost of investment over a longer time horizon. Such financing approaches require the types of data being collected by these government programs. Data could be used for reporting and impact measurement purposes and standardization could be used to help classify important data that institutional investors need to know, demonstrating net-zero and climate resilience-aligned outcomes. Improving data transparency on other co-benefits of climate mitigation, such as climate resilience or benefits to Indigenous communities, would likely drive further investment interest into these projects.

Additionally, the government should identify new opportunities to utilize its own procurement decisions to incorporate net-zero and climate resilience-aligned considerations. While there is some work underway,Footnote 33 existing efforts remain fragmented and the government should look to use its spending power to guide collective movement in this area. Doing so would put the government’s position as one of Canada’s largest buyers towards the support of net-zero and climate resilience-aligned products and services, de-risking the commercial activities of suppliers and encouraging greater investment. This could include the procurement of zero-emissions vehicle fleets, government building retrofits for decarbonization and resilience, and renewable energy procurement (including through PPAs), in addition to stricter disclosure requirements for federal suppliers. To ensure continued investments and accountability in this area, the government should consider linking its procurement efforts to national climate targets.

Promoting cost and price certainty in the carbon markets

Recommendation #3 – Contribute to carbon pricing certainty for emerging technologies.

Several large-scale investments in emission reduction projects, for example carbon capture and storage, requires the value of future carbon credits to be guaranteed. Uncertainty of carbon credit pricing has been identified as a key impediment to investment in low carbon activities.

Carbon pricing risk can be due to the risk of changing government policy approaches, uncertainty in the voluntary carbon market, and potential future oversupply of offsets resulting from large decarbonization investments.

Government can continue to expand its efforts for guaranteeing carbon prices in various ways, including by adopting contracts for difference, as introduced in the CGF, between private sector actors and government to compensate the private sector party to the contract if carbon credits lose market value. Expansion of efforts includes the additional layer of support through a carbon floor price, since credits are traded on the secondary market and price signals from the carbon tax do not necessarily reflect the value that a credit will be sold at. Price certainty for environmental attributes of net-zero and climate resilience-aligned investment can manage risks, create a stronger investment case, and ultimately help bring to market innovative projects in hard-to-abate sectors.

Price guarantees for carbon credits are particularly meaningful for investments such as carbon capture and storage for heavy industry, or the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices on farms. Such investment is often tied to financial modelling considering avoided regulatory costs or the value of carbon credits generated. Price and cost stability provides more certainty for financial decision making.

Blended finance to lower cost of capital

Recommendation #4 – Accelerate the design and implementation of blended finance, including concessional capital and risk guarantees, in partnership with private sector investors, to identify and fund net-zero and resilience-aligned investments.

One of the most promising opportunities for encouraging greater private sector investment is blended and concessional finance, by which we mean finance that strategically uses capital from public sources specifically to increase private sector investment. In practice, private sector capital providers identify investment opportunities, then blend their capital with government financing, so that they can provide a lower cost of capital to the borrower. Government may also backstop the risk of the financing by providing guarantees or other recourse to the private sector investors. This is in contrast with non-repayable financial programs that the government offers (e.g., grants), which play an important role for earlier stage technologies but have lower investment multiplier effects.

The private sector has the capability to reach clients and can access capital at the volumes required to finance energy transition and climate adaptation for the right risk and return profiles. In turn, the government can provide lower cost of capital than the private sector. Concessional and/or blended finance opportunities can encourage co-financing and risk-sharing in a way that can increase overall investment.

In the context of net-zero and climate resilience-aligned investment, government funding can be conditioned on measurement/quantification and monitoring/reporting of decarbonization or resilience impact by the borrower. Cost of capital could be designed to reflect savings related to energy efficiency savings or other financial benefits to the borrower, making the investment cost neutral. These approaches are already being taken by organizations like CIB in the buildings sector.

This approach allows government to better target the deployment of public funds to investment opportunities vetted by professional private sector financial partners. It also allows public capital to be magnified by private co-investment alongside public capital. Private sector partners can provide clients with lower capital costs to achieve sustainability and resilience goals, incentivize the measurement and quantification of environmental impact, and reduce risks associated with net-zero and climate resilience-aligned investment. Borrowers benefit from lower cost of capital, more certainty on financial benefits of net-zero and climate resilience-aligned investment, cost neutrality in some cases, and opportunities to track and report the environmental benefits of their investment with funding partners.

To design blended and concessional finance to leverage the most private sector capital, SFAC recommends the government engage with FIs on program design that can work across multiple sectors. SFAC believes that key principles to success are largely already known, for example through various blended finance programs offered by CIB and CGF. It would also be beneficial to quantify the estimated ratio of public to private financing needed to inform and allocate future concessional financing programs. Further, existing funding programs can be restructured as concessional finance as an alternative to originating new funding. Now is the critical time to expand concessional finance to bring more private sector investment to net-zero solutions in the key sectors identified in this report.

Supporting Indigenous participation and investment towards net-zero policy goals

Recommendation #5 – The Government of Canada should promote and incentivize Indigenous participation in project development and ownership.

Indigenous communities have faced challenges in accessing capital for participation in major infrastructure projects necessary for achieving net-zero aligned policy goals and decarbonizing remote communities across Canada. In addition, they are often the most impacted by physical climate risks.Footnote 34 Increasing their access to and qualification for competitively priced capital would support both reconciliation and net-zero policy objectives. It could also create opportunities to encourage Indigenous participation for the extraction and processing of critical minerals on Indigenous lands, where Indigenous People are stewards of the land and protectors of the environment, as part of the net-zero value chain.

SFAC supports the Government of Canada’s continued development of programs targeting Indigenous ownership of, and participation in, net zero projects which also offer economic and social opportunities. The commitment to establish an Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program in the 2023 Fall Economic Statement marks a significant advancement.Footnote 35 Similarly, the 2023 Budget’s announcement that the CIB will provide loans to Indigenous communities to acquire equity stakes in CIB-funded infrastructure projects is another positive development.Footnote 36 SFAC encourages the Government of Canada’s 2024 Budget to provide the details and direction necessary to establish the Indigenous Loan Guarantee program to help overcome the financing barriers still faced by Indigenous communities.

Indigenous communities should be consulted on other opportunities to increase their participation in Canada’s transition towards a more resilient and net-zero economy.

Conclusion

This report is intended to provide insights into opportunities and challenges for mobilizing capital to support decarbonization and climate resilience, as viewed by SFAC members in January 2024. It is evident that the government’s continued advancement and engagement in catalyzing private sector investment is vital for a successful net-zero transition. The community of financial institutions is notably aligned with this goal, well-positioned to help accelerate these conversations and willing to support the government in its forthcoming steps. Proactive and strategic partnerships will allow these ambitions to translate into tangible realities and it is recommended that the government continue to utilize the alignment and support of FIs.

Suggested next steps for the Government of Canada include continued engagement with public and private capital providers to design and implement the most effective support to bring in private capital and close the funding gap that exists for meeting Canada’s net-zero targets and resilience goals. This should include further quantification of the funding needed to achieve net-zero goals, by region and sector. Pilot projects should be utilized, which, if successful, can be broadened to scale.

The members of the Working Group and the SFAC thank the Government of Canada for requesting and receiving our views on ways to mobilize private capital for decarbonization and resilience towards the policy objective of net zero by 2050.

We trust the foregoing provides some insights into opportunities and challenges that can be the basis for further initiatives and collaboration between the private and public sectors. We look forward to continued engagement with the Government of Canada on this topic and welcome the opportunity to collaborate on implementation plans.

Signed,

The Sustainable Finance Action Council

Appendix 1 – Budget 2022 – A Plan to Grow our Economy and Make Life More Affordable

The Sustainable Finance Action Council will develop and report on strategies for aligning private sector capital with the transition to net zero, with support from the Canadian Climate Institute and in consultation with the Net-Zero Advisory Body

Source: Archived - Budget 2022: A Plan to Grow Our Economy and Make Life More Affordable (canada.ca)

Appendix 2 – Net-Zero Pathway Research

- A Roadmap for Canada’s Battery Value Chain (Transition Accelerator)

- Achieving Net-Zero Emissions by 2050 in Canada (Navius’ technical report for CCI’s Net-Zero Future Report)

- Barriers to Innovation in the Canadian Electricity Sector and Available Policy Responses (Canadian Climate Institute)

- Canada’s Clean Energy Economy to 2030 (Navius, prepared for Clean Energy Canada)

- Canada’s Electrification Advantage in the Race to Net Zero (Electrifying Canada)

- Canada’s Future in a Net-Zero World (Transition Accelerator, SPI)

- Capital Mobilization Plan for a Canadian Low-Carbon Economy (Institute for Sustainable Finance)

- Deep Decarbonization from a Global Perspective (Transition Accelerator, SPI)

- Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance – Final Report

- Green Retrofit Economy Study (Canada Green Building Council and Delphi Group)

- Improving Integration and Coordination of Provincially-Managed Electricity Systems (Canadian Climate Institute)

- Indigenous Opportunities in a Net-Zero Conference Primer (FNMPC)

- Indigenous Sustainable Investment & ESG Conference Primer (FNMPC)

- Net-Zero Opportunities: A Provincial Perspective (Canadian Climate Institute)

- Pathways to Net Zero: A Decision Support Tool (Transition Accelerator)

- Same Game, New Rules (Energy Futures Lab)

- Sink or Swim (Canadian Climate Institute)

- Taking a Strategic Approach to Industrial Transition (Transition Accelerator, SPI)

- The Big Switch (Canadian Climate Institute)

- The Only Road to Net Zero Runs Through Indigenous Lands post-conference report (FNMPC)