Prevention strategies from the CF Expert Panel on Suicide Prevention

A. Education and Awareness Programs

This section deals with suicide education and awareness programs that target CF members (i.e., the rank-and-file), CF gatekeepers, and CF clinicians.

Education of CF Members

Many CF members have received basic suicide awareness training, and a significant number have received more advanced (e.g., multi-day) training (see ANNEX H). Suicide awareness has been commonly incorporated into CF mental health education, but until recently, this programming was fragmented and inconsistent. For this reason, the CF has stood up a Mental Health Education Advisory Committee (MHEAC), which is tasked with providing high-level guidance for the development, implementation, and evaluation of a comprehensive mental health education program. In addition, it has enhanced and expanded its Joint Speakers Bureau (JSB); the JSB provides intensive training to its presenters to assure consistency and quality of the educational programming.

The vision for the CF’s mental health education program is that members will get ongoing education about mental health issues at multiple points in their career and deployment cycle. Education will begin as early as possible in the member’s career. Training content will change to reflect where the member is in their career/deployment cycle, with the right content being delivered at the right time.

Using guidance provided by the MHEAC (and priorities provided by senior leaders), the CF has already developed a series of modules for the Primary Leadership Qualification (PLQ) course and another series for pre-deployment training. The next modules developed will be for the post-deployment period. Additional modules for earlier and later in the career cycle will follow over the next year or two. Suicide awareness training is being integrated into each of the modules as appropriate.

The CF has also developed a half-day suicide awareness and prevention program as part of the Strengthening the Forces (StF) Program; information on this and other StF mental health and wellbeing programs is found in ANNEX H. The module is grounded in the US Army’s “ACE” program [20], which targets specific skills for recognizing suicidality and intervening effectively. The ACE program teaches members to:

- Ask about suicidal thoughts;

- Care for those who express them; and

- Escort suicidal patients to care.

Suicide awareness training also targets mental health literacy, including helping individuals recognize the need for mental health care in themselves. Indeed, in both the CF [21;22] and the Canadian general population [23] the leading barrier to mental health care (seen in at least 80% of those surveyed) is that individuals with mental disorders do not appear to realize that they have a problem for which help is available. There is also evidence that public education campaigns can be associated with improvement in mental health literacy and treatment-seeking. Disappointingly, patients with depression with suicidal ideation benefited far less than others [24].

Still, suicide awareness education as a single intervention has never been shown to be effective at reducing suicidal behaviour [6]. Nevertheless, all community-based suicide prevention programs that have some evidence of efficacy have involved at least some mass education. Unfortunately, effective programs have also included other elements, so it is not possible to attribute their apparent benefits to the educational aspect. If education is effective, then the right “dose” is not known—there is some suggestion of efficacy with both brief programs and longer programs [18;19].

The CF’s required mental health education program is delivered pre-deployment, post-deployment, and during career courses. Even though not all members will have an immediate opportunity to take part in these training sessions, the Panel chose not to mandate immediate training for all members. Its rationale was as follows:

- Suicide in the CF is an important public health problem, but it is not a public health crisis.

- Suicide education is only one small part of the CF’s comprehensive prevention program.

- The independent contribution of suicide awareness and education remains uncertain.

- Members have complex educational needs for many different types of essential (and even lifesaving) training, and the Panel was reluctant to declare suicide prevention to be the top priority. Instead, it felt that those responsible for managing the training for a given group (their supervisor, commanding officer, or MOSID advisor) were in a better position to determine overall training priorities.

- Stand-alone suicide prevention training is available through Strengthening the Forces for those for whom this is felt to be urgent or essential.

The Panel applied this same logic to education for gatekeepers and clinicians (see below).

- Recommendation 1: The CF should continue to leverage its existing mechanisms for developing, implementing, and evaluating mental health training, specifically the MHEAC and the JSB.

- Recommendation 2: Routine suicide awareness and prevention training should be incorporated into the rest of the regular, coordinated mental health training that will occur across each member’s career and deployment cycle.

- Recommendation 3: The US Army’s “ACE” program targets the key competencies for suicide prevention and should be strongly considered for the CF’s mental health education efforts.

- Recommendation 4: The development of suicide awareness and prevention training should follow sound principles of curriculum development and adult education. Specifically, such training should incorporate opportunities for learners to practice suicide-specific skills, such as asking a friend about suicidal thoughts.

- Recommendation 5: The fate of the StF module on suicide prevention should be decided by the Mental Health Education Advisory Committee. Until such time as the full mental health training program has been implemented, the StF suicide prevention program should continue to be available as a training option, particularly for those in gatekeeper roles.

- Recommendation 6: For mass education, shorter programs should be favoured over longer ones until such time as there is evidence that longer programs lead to superior outcomes.

- Recommendation 7: The Panel does not see the need to mandate that all members receive suicide prevention training by a certain date.

Gatekeeper Education

CF members in certain roles can serve as “gatekeepers” for suicidal individuals. These gatekeepers include chaplains, military police, personnel selection officers, and others. Military leaders are also important gatekeepers to mental health care in that their approval is often sought by members needing care during work hours.

Beyond this formal gatekeeping role, there is a sound rationale for benefits of good leadership as a suicide prevention strategy: Leaders have a special role in monitoring and attending to the health and wellbeing of their subordinates. The climate that they set with respect to attitudes towards mental health care can influence care-seeking for mental health problems [25]. Work stress is a contributing factor in some military suicides, and leader behaviour can mitigate work-related stress and strain [26;27]. Leaders who know their subordinates well may have additional opportunities to help them through personal or family problems as well.

While the above rationale creates a logical link between good leadership and suicide prevention, there is as yet no firm evidence that this potential benefit is indeed realized. Nevertheless, good leadership will obviously provide many other tangible benefits to the CF and to CF members.

Disciplinary action and legal difficulties are common suicide triggers, with more shameful transgressions (e.g., paedophilia) presumably being particularly risky. In addition, those with mental health problems are plausibly at increased risk for disciplinary infractions. Hence, an opportunity exists to manage disciplinary actions in a way that mitigates suicide risk.

There is no firm evidence that specific suicide training of leaders or other gatekeepers prevents suicides [6]. However, several prevention programs for which reasonable evidence of efficacy exists [19;28-30] included such training as part of a whole suite of different interventions. There is also evidence that gatekeeper education can improve knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy about suicide and mental health [31].

While the Panel felt that that there was a good enough rationale for requiring at least some specific suicide prevention training, it felt strongly that this training should not eclipse the likely greater importance of general good leadership skills as a suicide prevention tool.

- Recommendation 8: The linkage between good leadership, work-related stress, and mental health problems should be covered in the CF’s routine mental health education program, as should the leader’s role in overcoming barriers to mental health care.

- Recommendation 9: General leadership skills that form the backbone of leadership training in the CF are probably more important for suicide prevention than specific suicide prevention skills. However, there is enough evidence of potential benefit of suicide prevention training that it should be incorporated into the CF’s mental health education program across a leader’s career cycle. Stand-alone suicide prevention training may be considered for leaders who will not be receiving suicide prevention training as part of a career course (or other training) over the new few years, but such training should not be considered mandatory. Instead, leaders should prioritize the need for suicide prevention training against other unit and individual training needs.

- Recommendation 10: Educational programming for leaders should specifically address ways of managing the disciplinary process in ways that mitigate suicide risk.

- Recommendation 11: Those who manage the ongoing education of CF trades that have an increased likelihood of encountering patients at suicide risk (such as MP’s) should consider the need for specific suicide prevention training for their occupational group. The priority of this training should be weighed against the many other educational needs of a given occupational group.

Education of Clinicians

All CF clinicians will have had education on suicide as part of their professional training; they will also have had the opportunity to develop suicide-specific skills. Recently-trained primary care clinicians will also have had training in the recognition and management of depression. However, the strength of the training and experience will vary substantially from individual to individual [32]. Medics and other front-line personnel are likely to have had less training and experience in assessment of suicidality. Nevertheless, the Panel felt that the ability to establish trust and rapport with the patient was the most central skill for suicide assessment: Without such a foundation, effective assessment of suicidality cannot occur.

There is evidence that education of primary care clinicians on recognition and treatment of depression may decrease suicidal behaviour [6;31]. However, the study showing the clearest benefit was done long ago [33], when knowledge of depression and its treatment were not common in primary care providers. More recent studies have shown apparent benefits in other countries [34;35], but the culture and medical care system are different enough that the apparent benefits may not apply in Canada. Systematic efforts to enhance the quality of care often require an educational component (though in general, clinician education alone tends to have little or no sustained effect [36]).

- Recommendation 12: Those managing the educational programming for CF health professionals should consider offering educational programming on depression and suicide as part of their regular educational activities (e.g., occupation-specific training at CFB Borden). These individuals should weigh the priority of such training against the many other educational needs of their occupational group.

- Recommendation 13: The ability to establish trust and rapport with a potentially suicidal patient is fundamental to the assessment of suicidality. As such, evaluating and, if needed, enhancing these skills should be a focus of suicide prevention education for clinicians.

- Recommendation 14: Those supervising clinicians should consider the need to provide targeted education or training on depression and suicide as part of the clinician’s Personal Learning Plan. Again, this needs to be prioritized on an individual basis based on the totality of the individual’s educational needs.

B. Screening and Assessment

Currently, the CF screens members for suicidal ideation both during the Periodic Health Assessment (PHA), which takes place for all Regular Force members every 2 – 5 years, and during the Enhanced Post-deployment Screening that is required 3 to 6 months after return from deployments of longer than 60 days, duration. Members also complete a screening questionnaire as they are preparing for a deployment. In all of these cases, the patient questionnaire includes a single question on suicidal thoughts. These instruments also contain screening questions on depression, PTSD, and alcohol use disorders, which are known risk factors for suicidal behaviour.

Consensus panels have concluded that there is no evidence that routine screening for suicide in primary care prevents suicide [37]. Nor, however, has harm been demonstrated, and data collected during screening programs can have surveillance value.

Nearly all suicide victims have evidence of a mental disorder, with depression predominating [6]. However, many patients with depression go unrecognized and untreated in primary care settings [38]. Effective care for depression is available, and it attenuates suicide risk. 1 This provides a sound theoretical rationale for screening for depression.

There is good evidence that routinely screening for depression in primary care can be superior to usual care, provided that certain additional conditions are met (such as having a systematic way of assuring follow-up of depressed patients [39;40]). Different consensus groups reviewing the more or less the same evidence base have recommended screening with varying levels of enthusiasm. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force (UPSTF) recommended “screening adults for depression in clinical practices that have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up,

” summarizing the evidence thusly:

“The USPSTF found good evidence that screening improves the accurate identification of depressed patients in primary care settings and that treatment of depressed adults identified in primary care settings decreases clinical morbidity. Trials that have directly evaluated the effect of screening on clinical outcomes have shown mixed results. Small benefits have been observed in studies that simply feed back screening results to clinicians. Larger benefits have been observed in studies in which the communication of screening results is coordinated with effective follow-up and treatment. The USPSTF concluded the benefits of screening are likely to outweigh any potential harms.” [39]

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care concluded that:

“…there is fair evidence to recommend screening adults in the general population for depression in primary care settings that have integrated programs for feedback to patients and access to case management or mental health care.” [40]

In contrast, the Cochrane Collaborative found:

“There is substantial evidence that routinely administered case finding/screening questionnaires for depression have minimal impact on the detection, management or outcome of depression by clinicians. Practice guidelines and recommendations to adopt this strategy, in isolation, in order to improve the quality of health care should be resisted. The longer term benefits and costs of routine screening/case finding for depression have not been evaluated. A two stage procedure for screening/case finding may be effective, but this needs to be evaluated in a large scale cluster randomised trial, with a prospective economic evaluation.” [41]

The likely reason for Cochrane’s different conclusion is that that group is reluctant to do post-hoc analysis of studies that show differential effects. This justifiably conservative position minimizes the chance of recommending something that is valueless or harmful. On the other hand, this approach does increase the risk of depriving people of effective interventions before the most definitive proof of efficacy is available.

The ideal frequency of depression screening is unknown, but the rationale for increasing the frequency of screening in the CF is as follows:

- Depressive symptoms fluctuate over time (sometimes quite rapidly).

- Depression has important consequences on well being and functioning, so truncating the period of suffering offers real benefits to the patient (and to the CF).

- Suicidal thoughts and intent also come and go in a somewhat unpredictable fashion in depressed patients. Suicidality can develop relatively rapidly after onset of depression, and suicidal behaviour commonly occurs after a very brief period of suicidal intent: One study showed that the period between the first current thought of suicide and the actual attempt lasted 10 minutes or less in almost half of those who attempted suicide [42].

- Most convincingly, comprehensive, systems-based quality improvement initiatives have shown significantly benefits in depression identification and treatment [43], 2 and many of these systems have involved more frequent screening for depression, with some using screening atevery primary care visit [44].

Screening for PTSD has attracted interest in military organizations, particularly in the US where high rates of this condition are being seen as a consequence of the conflicts in SW Asia [7;45]. Military organizations obviously have a special obligation to mitigate PTSD, given that it is not infrequently service-related [46]. In the context of suicide prevention in the CF, the rationale for screening is as follows: As with depression, PTSD is a risk factor for suicidality [47-50], and it often causes significant functional impairments [51;52]. PTSD is also reasonably prevalent in the CF: In 2002, the 12-month prevalence in the Regular Forces was 2.8% [53], 3 and approximately 4% of CF members returning from deployment in support of the mission in Afghanistan identify significant symptoms suggestive of PTSD 4 on their post-deployment screening [54]. Effective treatments are available, but less that half of PTSD sufferers are in care [55]. The primary reason for failing to seek care appears to be that the sufferer does not appear to realize they have a problem for which effective help is available [21;56]. Even for CF members who do seek care, there is often a substantial delay between onset of symptoms and first care [55]. 5 However, while there is a sound theoretical rationale for mass screening for PTSD, data demonstrating clear benefits from doing so is limited and equivocal [45], and there is hence even more uncertainty about the optimal frequency of screening. However, the issue of the benefits and risks of screening for PTSD is being actively researched, so additional data to inform screening practices will be emerging over the coming years. For example, the US military is currently evaluating a primary care initiative that includes routine screening for PTSD [57].

- Recommendation 15: Additional mass screening for suicidal ideation in the CF is not recommended, though existing screening during the Periodic Health Assessment and pre- and post-deployment screening may continue as this practice provides useful surveillance data and harm is unlikely.

- Recommendation 16: Depression screening during the Periodic Health Assessment and the pre- and post-deployment screening should continue.

- Recommendation 17: The CF should consider increasing the frequency of depression screening, but only if it forms part of a systematic approach to primary care management of depression.

- Recommendation 18: The CF should follow the emerging literature on the benefits of more frequent PTSD screening in primary care and implement such screening if and when there is sufficient evidence of benefit.

Assessment of Suicidality

Optimal treatment of suicidality cannot occur without a strong assessment of both the underlying mental disorder(s) and of the suicidality itself. The American Psychiatric Association has published guidelines for the assessment and treatment of suicidality [58]. These guidelines delineate risk factors and warning signs for suicide and indicate when and how to assess suicidality. While these guidelines date from 2003, the Panel judged them to be a sound approach for the CF.

While a long list of suicide risk factors have been identified [58], these are poor predictors of suicide in any individual patient. Overemphasis on suicide risk factors is problematic if those perceived to be alow risk do not get the assessment or treatment they need. Thus, the clinical suicide assessment (rather than a series of socio-demographic risk factors) needs to be the primary tool for risk assessment. Risk factor assessment may however have other value in terms of surveillance, performance measurement, and treatment planning.

Some have suggested that suicidality is a “vital sign” in mental health care that should assessed by their clinician at each and every visit [59]. Panel members believed that this is unnecessary and that it might result in the trivialization of the assessment process. For many low risk patients who have never had suicidality and are doing well in care, repetitive inquiry about suicidality can send the message that the therapist really doesn’t understand their situation. However, the Panel felt that this disadvantage might not apply to computerized questionnaires that have been shown to enhance the quality of care delivered [60;61].

Quality assurance reviews of suicide victims have consistently identified deficiencies in the clinical suicide assessment [4;62;63], suggesting that increased attention to this essential aspect of care is needed in clinical quality assurance activities.

- Recommendation 19: The CF should adopt and disseminate the APA guidelines on assessment of suicidality.

- Recommendation 20: Assessment of suicidality should of course occur at the first encounter for evaluation of patients with symptoms of mental health problems in both mental health and primary care settings. Suicidality should be reassessed during care for patients who have deteriorated, have developed new symptoms or co-morbidities, have failed to improve as expected, or are experiencing a crisis or significant new stressors. Assessment of suicidality at each and every mental health encounter is not required and in fact may be counterproductive. However, this last finding may not apply to computerized mental health outcomes management systems.

- Recommendation 21: In its educational programming on suicide, the CF should emphasize the limited value of risk factors for predicting suicide on a case-by-case basis. Instead, suicide risk assessment hinges on the precise content of an individual’s suicide ideation and plan.

- Recommendation 22: Given its central role in suicide prevention, the assessment of suicidality should be a target for quality assurance audits.

Treatment of Suicidality

The most important decision in the treatment of suicidal patients is the setting of care (e.g., inpatient vs. outpatient). The American Psychiatric Association guidelines on this [58] were judged to be broadly applicable to the CF context.

The most important limitation in these guidelines is that they assume that inpatient psychiatric beds are always available for treatment of suicidal patients. In Canada, the reality is otherwise: The CF no longer has its own inpatient beds, and the inpatient system is seriously strained to the point that many high-risk patients cannot be accommodated for as long as their treating clinicians would like. Thus, the reality is that members with significant suicidal risk will need to be managed as outpatients.

Assuring the safety of a suicidal patient outside of the hospital is always a challenge, but the CF has several additional challenges: First, members may have been removed from their family of origin or other primary sources of social support as a consequence of their military duties. Second, members living in barracks do not have the same level of privacy as civilians usually enjoy. Finally, many CF members need to have access to firearms in order to do their jobs, but restricting access to these is an essential part of a harm reduction strategy for suicidal individuals.

These constraints have led to the use of a unit “buddy watch,” in which others in the unit are charged with assuring the safety of a suicidal individual [64;65]. This approach is well-intentioned but problematic: It necessitates a large-scale breach of confidentiality to execute the watch, during a time at which such confidentiality is most essential: The suicide attempt is stigmatizing in and of itself; many patients are ashamed at having attempted, and some are even embarrassed at having failed. In addition, those performing the “buddy watch” will have no experience in the management of suicidal patients, so the watch may not effectively control suicide risk. They may nevertheless feel responsible when tragedy supervenes. Finally, the period of significantly increased suicide risk lasts weeks to months, making a “buddy watch” difficult to sustain. All of that understood, the Panel agreed that under unusual circumstances (e.g., in a forward area on deployment) a “buddy watch” may be an essential and lifesaving intervention.

- Recommendation 23: The CF should empanel a separate group to develop best practices for outpatient management of individuals at high risk for suicidal behaviour (such as those discharged from an inpatient facility following a serious suicide attempt). The group should specifically address the issue of when a unit “buddy watch” is indicated as well as how precisely the watch is to be carried out. Because resources are likely to vary from region to region, a mixture of both national and regional solutions will be required.

- Recommendation 24: A unit “buddy watch” should be reserved for short-term use in truly exceptional circumstances, such as a serious suicide attempt at a remote Forward Operating Base.

C. Pharmacotherapy

Drug therapy is a cornerstone of treatment for the mental disorders that are most closely associated with suicidal behaviour, namely psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, and depression. These medications reverse many of the primary symptoms of the condition, improve well being, and enhance functioning. Clozapine and lithium have been shown to significantly decrease the risk of completed suicide in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, respectively [6]. However,these benefits are likely to be limited for the CF because more severe mental disorders are generally incompatible with military service.

Abundant evidence shows that antidepressants significantly decrease suicidal thoughts in depressed patients, on average [66;67]. Demonstrating ironclad evidence that medication prevents suicides is difficult for a series of methodological reasons. Nevertheless, the Panel and most experts believed that the balance of evidence strongly suggests that antidepressants do indeed decrease the risk of suicidal behaviour in adults. However, there does appear to be a paradoxical increase in the risk of suicidal behaviour in the weeks to months after initiating (or increasing the dose of) antidepressants in a small but important minority of patients [68].

There are conventional guidelines for the use of antidepressants and other psychiatric medications in abroad range of common disorders, such as depression, PTSD, and panic disorder. In addition, there are guidelines for the use of medications in suicidal patients in particular [58].

CF Regular Force members currently enjoy excellent access to whatever psychiatric medications they need at no out-of-pocket expense. Civilians have much more uneven insurance coverage of medications, which are usually not covered by the provincial insurance plans. Even when covered though private insurance, there are almost always co-pays and deductibles that can result in significant out of pocket costs. The CF has about twice as many psychiatrists per capita as the rest of Canada, which means that waiting times for specialist consultation on psychiatric medications are shorter than those seen in the provincial system.

- Recommendation 25: The CF should follow conventional, evidence-based guidelines for the drug treatment of mental disorders.

- Recommendation 26: The CF should follow the guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association with respect to drug therapy for suicidal patients. These guidelines provide instruction on how to mitigate the increased risk of suicidal behaviour that can occur in the first weeks to months after the initiation of antidepressants.

D. Psychotherapy

Evidence-based psychotherapies are available for a broad range of common mental disorders that increase the risk of suicide, such as depression, panic disorder, borderline personality disorder, PTSD, and others. For many disorders, there is evidence that psychotherapy offers additional benefits over drug therapy alone.

Cognitive-behavioural approaches have been the best studied and hence have the best evidence of efficacy behind them. For this reason, the CF has recently completed a nationwide CBT training program for its mental health providers. However, other approaches such as interpersonal therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-oriented therapy have also shown benefit.

Cognitive therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) have been shown in high quality studies to decrease the risk of suicidal behaviour in very high risk patients, such as those recently hospitalized for a serious suicide attempt or having a history of parasuicidal behaviour [6]. The three key targets of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) for high-risk patients are impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and hopelessness/pessimism [6;69].

Problem-solving therapy, interpersonal therapy, and even insight-oriented approaches have also been shown to be effective [6]. No high-quality studies have explored which of all of these approaches is best for suicidal patients, much less how to match individual patients to the treatment that is best for them personally.

What these therapies have in common is that they target suicidality (or the interpersonal problems driving it) as an independent problem needing specific care as opposed to simply being just a symptom of the underlying disorder. While the benefit of these approaches has been most convincingly demonstrated in patients with a history of suicidal behaviour, the Panel thought that other high-risk patients would also likely benefit from them.

As with medications, access to quality psychotherapy is much stronger in the CF than it is in the civilian sector in Canada. The CF will shortly have about twice as many psychologists and social workers per capita, compared to the Canadian provincial system. In addition, Regular Forces members have access to as much psychotherapy as they need at no out-of-pocket cost. As with medications, psychotherapy is poorly covered through the provincial health insurance plans, and private insurance generally has co-pays, deductibles, and benefit limits.

- Recommendation 27: Suicidality should be identified and addressed as a separate problem in mental health patients. Patients with suicidal ideation, intent, or behaviour should receive evidence-based psychotherapy specifically targeting the suicidality and the interpersonal problems that are driving it.

- Recommendation 28: Cognitive-behavioural approaches targeting impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and hopelessness/pessimism are particularly appealing for psychotherapy of suicidality because of their strong evidence base and the broad familiarity with CBT among CF clinicians.

- Recommendation 29: The decision to augment (or replace) suicidality-specific CBT with interpersonal therapy, purely cognitive therapy, problem-solving therapy, and insight-oriented approaches should be made by the treating clinician, in consideration of the totality of the clinical circumstances.

- Recommendation 30: Where clinically appropriate, using manualized approaches of proven benefit should be strongly considered (given that these have the best evidence of efficacy behind them).

E. Follow-up Care for Suicide Attempters/High-risk Patients

The first weeks and months after a suicide attempt are a period of markedly higher risk for repetition of suicidal behaviour [70-72]. This period should thus be characterized by intensive efforts to optimize medications, engage in diagnosis- and suicidality-specific psychotherapy, enhance social support, reinforce coping skills, resolve interpersonal conflicts, etc. These interventions will only work if the patient consistently shows up for care. Not surprisingly, failure to keep follow-up appointments is common in patients who go on to commit suicide.

Patients fail to follow-up for many reasons, including ambivalence about receiving care, limited or slow improvement, chaotic social circumstances, competing demands for their time and energy, treatment side-effects, and so on. Their primary diagnosis or certain character traits may interfere with their ability to connect with the therapist and do the hard work that effective psychotherapy requires. Anxiety or avoidance may also serve as a barrier. For these reasons, simply holding the patient responsible for ensuring their own follow-up is not a viable option.

Instead, systematic efforts on the part of the treatment facility to ensure follow-up are needed [6]. These improve outcomes for mental disorders in general [43] and for suicidal behaviour in particular [6]. In the primary care setting at least, more intensive methods of follow-up (e.g., using a nurse care manager who follows-up proactively with patients) are better than less intensive measures (e.g., simply sending the patient a note in the mail telling them to reschedule their appointment) [43]. CF members with complex mental and/or physical health problems are eligible for its Case Management Program. CF case managers are registered nurses who provide monitoring, coordination of care, coordination of benefits, etc.

In the CF, each clinic has its own approach to ensuring follow-up. While there is no reason to suspect that these processes are systematically deficient, some are likely stronger than others.

Recommendation 31: The CF should consider developing and implementing a single, system-wide process for assuring follow-up for patients receiving care for mental disorders in both primary care and specialty mental health care settings.

Recommendation 32: The CF’s existing Case Management Program can be used as a mechanism to improve follow-up for higher-risk mental health patients.

F. Restriction of Access to Lethal Means (“Means Reduction”)

Suicide research largely focuses on the question of why people commit suicide, with the assumption being that understanding this is the key to suicide prevention. However, there is an increasing focus on how people commit suicide, that is, what specific means they use [73].

It had long been assumed that the means of suicide were not particularly important—if people were denied access to a particular means (e.g., handguns) they would simply switch to another method of equal lethality (e.g., jumping from a bridge). While this “means displacement” does occur, there is strong evidence that means reduction can work [73]. One of the best examples is the change in the composition of household cooking gas in the United Kingdom starting the early 1960’s. Prior to that, the UK produced essentially all of its household gas through coal gasification. Coal gas has a high concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) as an impurity, and CO is highly toxic. As a result, CO poisoning using household gas was a preferred method of suicide in the UK [74].

During the 1960’s, a larger and larger proportion of household gas was produced using different methods, resulting in a drop from about 12% CO in 1960 to about 2% in 1970 [73]. Perhaps not surprisingly, suicides due to CO declined dramatically, from about 6 to 2 per 100,000 people per year [73]. Astonishingly, the rate of suicide due to other methods did not change in men and increased only slightly in women, with the end result being that the total suicide rate decreased significantly in both men and women [73]. Further analysis of this same data showed that this change was not likely due to other factors [75]. Subsequently, this means reduction phenomenon has been seen in other nations that changed the composition of household gas [76-78].

There is also evidence that other forms of means reduction can decrease the overall suicide rate; these include: [6]

- Gun control;

- Changes in access to and packaging of high-risk drugs;

- Use of catalytic converters in automobiles;

- and Installation of bridge barriers to prevent jumping deaths.

Data for some interventions is stronger than others, but taken as a whole the Panel (and most suicide prevention experts) believe that means reduction can significantly reduce suicide rates. In fact, the evidence behind means reduction is far stronger than that behind mass education. All of these means reduction approaches target the larger community as opposed to a specific subgroup such as military personnel. Many of the potential targets for means reduction in the CF have already occurred (e.g., strict control of access to service firearms) or are outside of the purview of the CF (e.g., erection of a bridge barrier).

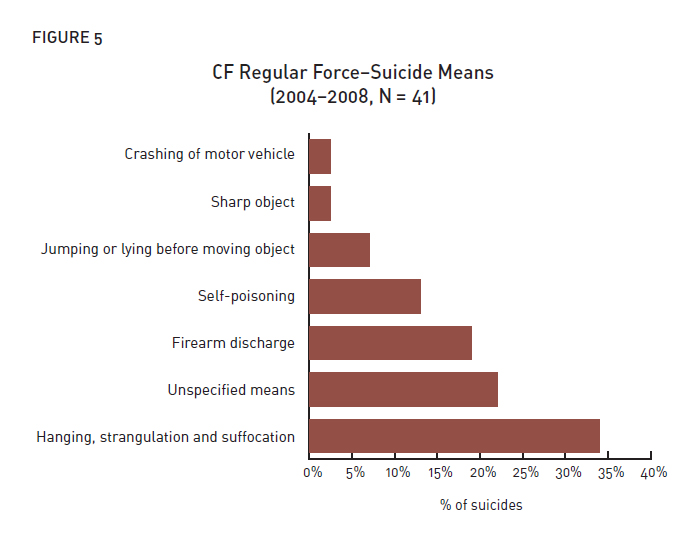

Means reduction needs to be driven by knowledge of the methods used in suicidal behaviour in the population at risk; this been captured since 2004 as part of the CF suicide surveillance system. As shown in Figure 5, the leading method has been hanging, strangling, or suffocation, for which means reduction is nearly impossible. In 22% of suicides, the means of suicide was not available to the epidemiologists responsible for suicide surveillance. Firearms were the next leading cause after “unknown,” but the source of the weapon (service weapon vs. personal weapon) was not always known. In addition, the extent to which access control procedures were followed for service firearm suicides is not captured. While self-poisoning accounted for relatively few suicides, it does represent a potential opportunity for means reduction because the CF controls its formulary and dispenses both prescription and over-the-counter medications; changes in these practices might decrease the risk of suicide.

Figure 5: CF Regular Force - Suicide Means (2004-2008, N=41)

Figure 5: CF Regular Force - Suicide Means (2004-2008, N=41) (Text equivalent)

| Suicide Means | % of suicides |

|---|---|

| Crashing of motor vehicle | 2% |

| Sharp object | 2% |

| Jumping or lying before moving object | 7% |

| Self-poisoning | 12% |

| Firearm discharge | 20% |

| Unspecified means | 22% |

| Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 34% |

In light of this data, the Panel identified only two potential areas for means prevention in the CF, namely optimizing restriction of access to service firearms and changing the drug dispensing/packaging of high-risk medications.

Further restriction of access to service firearms would be beneficial only if:

- These accounted for a significant fraction of member suicides;

- A significant number of suicides occurred due to breeches in existing firearm access controlmeasures; and

- Additional restrictions would not interfere with operational effectiveness. Firearms are essential work tools for many CF members, particularly while deployed.

Similarly, gains from changes in pharmacy practices would be realistic only if:

- Overdoses involved a limited number of high-risk drugs; and

- Drugs used in overdoses were largely procured from CF sources.

Means reduction is also essential at the level of the individual suicidal patient. For example, guns should be removed from the home and lethal medications disposed of.

- Recommendation 33: The CF should ensure that suicide surveillance data captures the source of the firearm involved (service vs. personal), as well as enough information to determine whether policies and procedures for firearm access were followed. This surveillance data should inform any needed changes in firearm control policies.

- Recommendation 34: The CF should also ensure that suicide surveillance data specifically addresses the agent used in drug suicides, as well as the source of the agent (CF pharmacy, civilian pharmacy using CF Blue Cross card, other), if known. The CF should review existing dispensing/packaging practices for high-risk drugs, with an eye towards identifying any additional opportunities for means reduction.

- Recommendation 35: Restriction of access to lethal means at the individual level should be part of the plan for management of suicidal patients in the outpatient setting.

G. Media Engagement

There is evidence that reporting of suicides in the media can trigger suicidal behaviour in susceptible individuals [6]. For this reasons, there are guidelines for responsible media reporting about suicides[79;80]. Only suicides that are “newsworthy” are to be reported; these include suicides of prominent public figures (whose death would have newsworthy regardless of the manner of death). In theory at least, thoughtful reporting of suicides might also offer public benefits by increasing awareness, publicising community resources, motivating improvements in care systems, etc.

CF member suicides are often judged by the media to be newsworthy, particularly when there is a perceived connection with a deployment. The general theme of such coverage tends to be that the CF created a mental health problem by deploying someone and then failed to provide adequate care, leading directly to the suicide. The media likely believes that it is serving the public interest by bringing these tragic cases to light, so that the alleged deficiencies in the care system may be fixed. Of course, the facts behind these cases are often more complex than portrayed in the media, but the CF cannot respond because of privacy restrictions. Overly negative or unbalanced reporting threatens to create or sustain barriers to care by eroding the much needed trust CF members must have in their system if they are to come forward for help.

If the media were to come to believe that CF members actually have excellent access to high-qualitymental health care and that member suicides are seldom a direct consequence of deployment, their interest in reporting member suicides would presumably be less.

- Recommendation 36: The CF should explore opportunities to proactively engage with the local, regional, and national media in order to educate them on suicide and mental health in the CF, with the goal being to encourage responsible reporting of CF member suicides and enhance the confidence that CF members and the public have in the CF’s mental health care.

H. Organizational Interventions Intended to Mitigate Work Stress and Strain

Work-related stress is a common contributor to mental disorders, especially depression [81]. In addition, PTSD and other traumatic stress disorders can be triggered by work-related traumatic events, particularly in occupations where exposure to such events is common. Workplace stress and conflict have been identified as common triggers for suicidal behaviour in service members. Thus, mitigation of work stress and strain though organization interventions such as training, policies, and programs might have suicide prevention effects.

Earlier, the Panel argued that ordinary good leadership skills were likely to be far a more potent suicide prevention tool than specific suicide prevention skills. This general principle applies when it comes to organizational policies: Those that effectively mitigate work stress are likely to be more powerful tools than suicide prevention policies per se. It should go without saying that preventing workplace stress and strain (e.g., through prevention of harassment) makes far more sense than helping employees cope with its consequences. And as was pointed out earlier, mitigation of workstress and strain will also offer innumerable benefits beyond suicide prevention.

Over the past decade in particular, the CF has implemented a number of policies and programs that target enhancement of quality of life and/or mitigation of work stress. These include its PERSTEMPO policy, screening and reintegration policy, dispute resolution policy, harassment prevention policy, and many others. Other policies and programs aim to support CF families, which should decrease family stress and, it is hoped, the failure of intimate relationships. The latter of course is an important trigger for suicidal behaviour [82].

The Panel mentioned earlier that educating leaders about managing the disciplinary process in ways that mitigate suicide risk offered some promise, at least in theory. The same is true for organizational policies and procedures relative to disciplinary procedures. For example, the US Air Force 6 has implemented what it calls a “hands-off” policy for airmen and airwomen under investigation[28]. 7 This requires that the interviewer “hand-off” the member being investigated to his or her chain of command immediately after the interview. Leaders are then supposed to assess coping and intervene as needed.

- Recommendation 37: The CF should continue to develop, implement, and evaluate policies and programs designed to mitigate stress and strain in the workplace, with the expectation that these may advance the CF’s suicide prevention agenda, while at the same time offering many other advantages to the organization.

- Recommendation 38: Disciplinary and investigative policies and procedures should be reviewed with an eye towards identifying any additional opportunities for changes that will mitigate stress and lower suicidal risk. Consideration should be given to implementing a version of the US Air Force’s “hands-off” policy for members under investigation. In order to be effective, such a policy would need to be supported by training and development of tools and resources for leaders, investigators, and the rank-and-file.

I. Selection, Resilience Training, and Risk Factor Modification

The CF’s model of potential targets for suicide prevention emphasizes that prevention strategies play out against a backdrop of individual risk and resilience factors, such as early childhood adversity, genetic predispositions, and personality. These and other factors mediate and/or moderate the effectiveness of suicide countermeasures. For example, some genetic factors likely influence the efficacy of antidepressants, and some personality traits or disorders (e.g. borderline) lessen the effectiveness of conventional psychotherapies.

These mediators/modifiers are thus potential targets for suicide prevention. The Panel identified three avenues that might have at least some potential, namely 1) selection; 2) resilience training; and 3) risk factor modification.

Screening and Selection

The CF typically screens out a limited number of potential recruits who have a history of serious mental disorders such as schizophrenia, recurrent severe depression, and bipolar disorder. These conditions typically result in impairments that are incompatible with military service and are also associated with a significantly increased risk of suicide.

Members preparing for deployment undergo both medical and psychosocial screening to be certain that they are fit for their deployment; questions on depression, PTSD, alcohol use disorders, and suicidal ideation are completed as a part of this process.

Screening out those who merely have risk factors for mental disorders (hence suicidality) is as difficult as it is ethically troubling. The problems with screening surround three fundamental issues:

- The prevalence of the outcome of interest (serious, chronic, and poorly treatable mental disorders) is low in epidemiological terms;

- The predictive value of existing screening/assessment tools is relatively low; and

- The screening/assessment tools can be faked to a significant degree. That is, motivated candidates can readily identify the “right” answers to screening questions.

These three factors conspire to see to it that any such screening/selection tool will be poorly predictive at the individual level under real-world circumstances.

While screening out people who are merely at risk for future mental disorders is not feasible, selection on the basis of performance is possible. That is, those who cannot stand the rigours of military training end up being selected out. The fact that nearly everyone the CF deploys performs adequately suggests that this selection process is working as it should. However, while this selection process works well for identifying those who will perform well while deployed, it does not guarantee that those selected will enjoy good long-term mental health after their return.

While screening and selection might in theory be viewed as a suicide prevention strategy for military organizations, these interventions do not prevent suicide for the population as whole—they simply displace a suicide-prone population from the military into the civilian sector.

For all of these reasons, the Panel did not see any current opportunities to prevent suicide through screening or selection of members.

- Recommendation 39: For the purposes of suicide prevention, the Panel does not recommendany additional screening or selection measures be implemented for either potential recruits or members preparing for deployment.

Resilience Training

Psychological resilience has been defined as “…the sum-total of psychological processes that permit individuals to maintain or return to previous levels of well being and functioning in response to adversity

”[83]. Training to enhance resiliency has strong common-sense appeal: Service members will face significant adversity, particularly when deployed on a difficult operation. There are psychological traits (notably neuroticism) that are associated with a significantly elevated risk of mental disorders. In psychotherapy, these traits can be moderated using cognitive-behavioural and other psychotherapeutic techniques. Applying such techniques to those with low-level depressive symptoms can decrease the odds of developing a full-blown major depression [84]. Stress inoculation therapy (SIT) can decrease anxiety and improve performance if undertaken prior to an upcoming anxiety-provoking event (such as parachuting) [85].

The high rate of serious mental health problems in personnel returning from the conflicts in SW Asia [7] and the operational requirement that many return for additional tours has kindled interest in resilience training in military organizations. However, there are no programs that have been shown to decrease the risk of mental disorders among service members. That understood, there are programs that show potential promise, such as the US Army’s BATTLEMIND Training Program [25;86;87]. None of these programs have been shown to decrease suicidal behaviour, though they can modestly improve well being [86], which in turn may have suicide-preventive effects.

The CF has recently completed a 10-hour pre-deployment mental health training program that includes several modules that include aspects of resilience training. Other resilience-oriented modules will be included in the full mental health curriculum. As of yet, however, evaluation of these resilience training approaches in the CF is limited.

- Recommendation 40: The CF should continue to evaluate the resilience training aspects of its mental health training program.

- Recommendation 41: The CF should continue to monitor the scientific literature in the area of resilience training, modifying its own programming to reflect best practices.

Risk Factor Modification

In addition to the universal mental health education program coordinated by the Mental Health Education Advisory Committee, the CF routinely offers other evidence-based programs through the mental health and wellbeing program of “Strengthening the Forces”. These include Managing Angry Moments, Basic Relationship Training, and Stress: Take Charge. None of these programs have been shown to prevent suicidal behaviour, but there is sound reason to believe that they might help. For example, failed intimate relationships are a common trigger for suicide, and Basic Relationship Training is designed to prevent or resolve relationship conflicts, enhance intimacy, and improve communication, hopefully preventing the failure of some relationships. Even if these programs do not prevent suicidal behaviour, they offer other concrete benefits to the CF, its members, and their families.

Alcohol misuse is a common risk factor and trigger for suicidal behaviour [6;88], and the CF has an active alcohol abuse prevention strategy. The CF also offers evidence-based treatment for alcohol use disorders through its Base Addictions Counsellors. Different programs target those with and without full-blown addiction.

Members seeking alcohol abuse treatment services have strong confidentiality protections: The only information that may be divulged to the member’s chain of command without the member’s permission is their medical employment limitations. There is no indication that this policy has jeopardized safety or operational effectiveness.

- Recommendation 42: The CF’s Strengthening the Forces programs on anger management, stress management, and healthy relationships likely improve member and family wellbeing and mitigate primary risk factors for suicidal behaviour. For these reasons, they should continue to be offered.

J. Systematic Efforts to Overcome Barriers to Mental Health Care

As mentioned earlier, nearly all suicide victims have an apparent mental health problem at the time oftheir death, but many are not receiving care [89-92]. Because effective care can reduce suicidal risk, overcoming barriers to care must be an essential part of any suicide prevention program.

The principal strategy used in most suicide prevention programs to overcome barriers to care is mass education, with the goals being improved mental health literacy, stronger suicide intervention skills, and destigmatization of mental health problems. These address some but not all of the potential barriers to mental health care. For example, they do not touch structural barriers such as limited access to mental health providers, difficulty getting time off work, problems with transportation, linguistic barriers, etc.

For this reason, the CF’s Rx2000 Mental Health Project has included a broad range of initiatives to overcome barriers to care, including:

- Offering very strong confidentiality and career protection for those who seek care;

- Offering up to 10 sessions of confidential mental health care from a non-CF provider through the Canadian Forces Member Assistance Program (CFMAP). CFMAP also offers a 24 hour toll-free telephone line for individuals in crisis;

- Increasing the numbers of mental health providers—the CF will shortly have about twice as many mental health providers per capita as the average Canadian;

- Developing an innovative peer support program for those with Operational Stress Injuries (the OSISS program), which serves as an important bridge to care for members who are reluctant to seek it;

- Developing mental health training that targets stigma and other attitudinal barriers to care;

- Developing a high-profile public awareness campaign on mental disorders (“Be the Difference”); and

- Developing and implementing screening for common mental disorders during Periodic Health Assessments and post-deployment screening.

Much has been made of the special barriers that military personnel may face, such as stigma. Stigma is however only one barrier of many, and it may not be a greater problem in the CF than in the general population [21;23;56]. Furthermore, even if military personnel have special barriers to care, they also have special access to care: They receive any needed treatment at absolutely no cost during workhours, and services are available in both official languages nationwide. Transportation is provided (or reimbursed) for off-site services.

Even as far back as 2002 (that is, before most of the mental health initiatives had taken effect), CF members with mental health problems were significantly more likely to have sought mental health care than their general population counterparts [53]. Data collected since then shows that these initiatives are working: CF members now hold largely forward-thinking attitudes towards mental health care. 8 In addition, more than half of those who reported symptoms of PTSD or depression at the time of post-deployment screening were already in care at the time of their screening, which took place on average 5 months after their return [54]. Finally, data from one garrison showed that approximately 32% of personnel returning from deployment in support of the mission in Afghanistan sought mental health care in the first year after their return [93].

While these data are encouraging, the best data on barriers to care in the CF dates from 2002 [56]. The barriers under the current system are likely different—as one barrier is addressed, others become more prominent. In order to better understand barriers to care, the CF now includes detailed questions on barriers to mental health care in its biennial Health and Lifestyle Information Survey(HLIS). Results from the 2008/2009 survey will be available within a few months.

All available data on barriers to care in the CF pertain to care in garrison as opposed to in deployed settings, where barriers may be different. The CF now deploys several mental health providers on its major operations, but the extent of unmet need on deployment is unknown. Access to lethal means (i.e. handguns) is far easier on deployment, and there are occasional suicides on operations. For these reasons, the CF is in the process of planning an in-theatre mental health needs assessment modelled after the US’s Mental Health Assessment Team [25] approach.

The representatives on the Panel from the UK, US, and Australia indicated that their policies require that the chain of command be informed of suicidality in high-risk patients. They saw this as important for two reasons: First, the chain of command is fundamentally responsible for the member’s wellbeing and for the safety and success of the unit’s mission. Second, they felt that those in the chain of command could provide much needed support to a member of their unit who was struggling.

In contrast, CF representatives felt that strong confidentiality protections are essential if members are to feel safe in disclosing suicidal ideation. At the same time, though, CF representatives acknowledged that this should not preclude meaningful dialogue about medical employment limitations with the chain of command. Finally, voluntary disclosure by the member was acknowledged as often being helpful for their recovery.

Wait times are known to be a potential barrier to mental health care in Canadian civilians [23]. Wait times for mental health services in the CF are largely similar to or better than those experienced by Canadian civilians. Individuals are usually ambivalent about seeking mental health care—they recognize at some level that they are suffering but have concerns about whether care will work for them, what the consequences of care seeking will be, and so on. This ambivalence manifests itself in fluctuating levels of commitment to get care. Such fluctuation may be particularly prominent in those with personality traits that are known to predispose to suicidal behaviour, such as borderline traits and impulsivity.

Even for those who firmly commit to getting help for a longstanding problem will remain at risk for suicide (and for functional impairment) until they receive definitive care. Rapid triage evaluation of suicidality in such patients can only provide so much reassurance: Disclosing suicidal thoughts may require a stronger relationship with the therapist than can be established during a triage visit. Finally,even where wait times are not harmful, no one likes to wait more than they have to for any service. For all of these reasons, the Panel saw a potential opportunity to further improve satisfaction (and perhaps mitigate suicide risk) by shortening wait times further, even for “routine” cases.

- Recommendation 43: The CF should continue to identify the remaining barriers to mental health care (both in garrison and on deployment) and to make any needed changes to address these.

- Recommendation 44: Confidentiality with respect to suicidal thoughts and behaviour offers both advantages and disadvantages. CF mental health specialists believe that the effects of the CF’s policy of strong confidentiality protections surrounding suicidality are, in the balance, far more positive than negative. Nevertheless, CF clinicians should engage in meaningful dialogue about medical employment limitations with the operational chain of command. In addition, clinicians should encourage members to disclose details about their mental health problems when doing so can contribute to their recovery.

- Recommendation 45: The CF should continue to drive down wait times for mental health services to as low as is feasible.

K. Systematic Clinical Quality Improvement Efforts

The Panel alluded earlier to the “quality chasm” in mental health care. Data from other settings shows that relatively few mental health patients are receiving what experts would consider optimal care. For example, only 55% of Canadians receiving care for depression were judged to have received minimally adequate care [94]; multiple other studies from the US [95-97] and Canada [98;99] show similar or even more disappointing results. Guideline-consistent depression care in primary care settings has been shown to be as low as 8% for depressed patients in Canada [98] and as low as 13% in the US[100]. Data from disorders other than depression paints a similarly disturbing picture [101-106]. Tragically, care for those who attempt or complete suicide is, on average, particularly poor [107;108].

There is, however, evidence that guideline adherence is significantly better in specialty mental health vs. primary care settings, though there is substantial room for improvement there as well [100;109-113].

The causes of this “quality chasm” are complex and poorly understood. What is clear, though, is that simply having well-educated, well-trained, well-equipped professionals is not enough. These elements are necessary but not sufficient for the delivery of quality mental health care. Simply disseminating clinical practice guidelines or exhorting clinicians to try harder is expected to have little or no effect on performance or on patient outcomes. Thus, the Panel realizes that without additional effort, its recommendations on the optimal clinical management of suicidality will have little or no impact.

The data cited above comes from settings other than the CF, so it is possible that the well-resourced CF mental health care system 9 is performing better. Certainly the CF has built a system that should be capable of delivering high-quality care, but it has no way of proving that it is actually delivering it. Likewise, it cannot document the outcomes of care for those who seek it [114].

The CF’s mental health clinic model includes one Quality Improvement Coordinator at each of its 20 largest clinics. These individuals largely work at the local level to address clinic-specific issues. A limited number of headquarters staff are also involved in quality improvement in mental health care.

While these efforts are laudable, what is needed is a more systematic, national approach to quality improvement in mental health services. This requires detailed information on:

- Who sought care;

- The baseline characteristics of care seekers 10;

- When they sought care;

- How much care they received;

- Where they sought care;

- Which diagnoses were made;

- What precise types of care was delivered;

- and What sorts of outcomes were realized by the end of treatment.

Information needs to be captured in near real time and stored in an electronic data repository. Without rich electronic data, quality improvement efforts are hard to initiate and harder still to sustain. Epidemiological expertise is needed to be able to manipulate, analyze, report, and interpret the data.

Currently, usable system-wide data for quality assurance is limited. Planned enhancements to the Canadian Forces Health Information System (CFHIS) will help, but there will still be important blind spots (notably, detailed enough information on the process and outcomes of mental health care to support quality improvement).

This lack of an infrastructure to support quality improvement activities in mental health care is not unique to the CF. In 2006, the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science, and Technology noted:

“Canada currently has no national picture of the status of mental health across the country. Collecting quality data will provide better information for policy and decision-makers inside and outside of government, as well as service providers and consumer groups.” [115]

The US Institute of Medicine made similar observations in its study, Improving the Quality of Mental Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions [116].

Systematic efforts to improve the quality of mental health care can be effective. Such efforts generally involve “re-engineering” of the system of care rather than simply educating clinicians. For primary care settings, implementation of “collaborative care” models has been shown to dramatically increase the quality of care delivered to depressed patients [117]. One of the better known of these approaches is the RESPECT model [44;118], which has three main components:

- A “prepared practice”—this involves education on the program and on depression, as well as implementing regular screening for depression;

- A nurse “care manager,” who contacts patients by telephone regularly throughout their care, assessing residual symptom burden, medication compliance, side effects, etc.; and

- Enhanced access to specialty mental health services for patients (for formal consultation, ideally on-site in the primary care clinics) and for primary care providers and care managers (for informal consultation).

An adaptation of this model that targets both depression and PTSD is showing very promising results in the US Army [57].

- Recommendation 46: The CF must reinforce its capabilities in clinical quality improvementin mental health care. It must capture enough data on the processes and outcomes of care to permit identification of potential problem areas and to evaluate the effect of any countermeasures.

Post-suicide investigations represent a potentially powerful quality assurance tool. Current CF policy[119] requires that all member suicides be investigated by a Board of Inquiry (BOI). While BOI’s perform a very thorough investigation, the Panel felt that this was a weak and inefficient tool for suicide prevention, particularly for the CF Health Services Group. 11 A number of factors limit theusefulness of the BOI:

- The process may take more than a year to reach firm conclusions, constraining the value of any useful intelligence provided. By the time the report has been finalized, an additional 10 or more CF members may have committed suicide;

- By the time the BOI is empanelled and witnesses are called, important events may be many months in the past. This makes accurate assessment of key facts more difficult;

- While the investigations are painfully detailed in some areas, key information required for suicide prevention is sometimes missing;

- BOI members are dedicated and experienced service members, but they have little or no training or experience doing suicide investigations;

- The medical advisor on the BOI and witnesses provided by Health Services are taken away from other important duties;

- The investigation can be intrusive to friends and family members, particularly when it fails to provide the answer they were seeking;

- There is little corporate memory about the findings and recommendations of previous suicide BOI’s. Hence, similar recommendations get made time after time; and

- Having a BOI for all suicides may send the message that all CF suicides are preventable or the CF’s “fault.” After all, there is no requirement for a BOI when a member dies in an accident in their own vehicle, nor is there a requirement when a member dies of a heart attack while on duty.

Because of these limitations, the Panel felt that a rapid clinical suicide investigation immediately after a suicide would be far more valuable than the BOI for medical quality assurance purposes.

Psychological autopsies are not a typical part of suicide investigations in the CF, and the Panel felt that their value as a routine tool is questionable. In the US, these are reserved for cases in which the cause of death or the intent of the victim is in doubt, e.g. homicide vs. suicide, intentional vs. accidental overdose, etc.

- Recommendation 47: After each suicide, a clinical suicide investigation should take place as soon as possible:

- The primary purpose of this investigation should be to explore any opportunities for improved suicide prevention or care in the future, with a focus on health care and communication/collaboration between health professionals and the chain of command;

- A secondary purpose should be to feed useful epidemiological data into the CF’s suicide surveillance system;

- The investigation should be performed by one or more health professional(s) with special training/experience in suicide investigation;

- Investigators should be drawn from a limited pool of qualified investigators for whom performing such investigations would be one of their primary duties;

- The investigation should follow a standard protocol—the US’s Department of Defense Suicide Event Report would serve as a useful template;

- Psychological autopsy should be reserved for cases in which there is significant uncertainty about the cause of death (e.g., suicide vs. homicide). Those responsible for doing psychological autopsies should have specific training and experience in their execution.

- The CF should seek legal counsel to determine the extent to which the information in the clinical suicide investigation can be protected as a quality assurance activity; and

- The clinical suicide investigation (or some extract thereof) can serve as a useful reference document for BOI’s.

Surveillance is an essential component of any prevention program. Since 2004, the CF has implemented a suicide surveillance program, which is described in detail in ANNEX I. While this represents a significant advance over the previous system, key information for evaluation of prevention efforts is often missing. For example, documentation available to staff involved in suicide surveillance may not indicate the source of the weapon (personal vs. CF) for firearm suicides.

The CF has no mechanism for capturing information about suicides in Reservists, for whom the CF has much more limited potential for suicide prevention. Class A Reservists (who form the bulk of the CF Primary Reserve personnel) spend only a few hours per week in their military workplace and receive almost all of their health care through the provincial system.

Until recently, there was no ongoing surveillance mechanism within the CF or within Veterans Affairs Canada for suicide in veterans (that is, after separation from military service). This is an important blind spot because of evidence that service members may be at increased risk for suicide only after they release [12;120]; risk appears to be highest in the first few years after release [120;121].

To address this, the CF and Veterans Affairs Canada are working with Statistics Canada to develop the capacity to look at cancer incidence and mortality (including suicide-related mortality) in members and in veterans (including Reservists) who served since 1972. 12 This will involve linking CF personnel records with the national death and cancer registries on a periodic basis. 13 The CF has other effective surveillance mechanisms for suicide-related information, including suicidal ideation, self-reported suicide attempts, symptoms of mental health problems, and barriers to mental health care. Data from elsewhere suggests that military suicide attempts are largely similar to completed suicides, with the exception of the use of less lethal means. Serious suicide attempts likely outnumber completed suicides by about a factor of five, providing additional statistical power for evaluation of suicide prevention programs.

- Recommendation 48: The CF should review the information required for its suicide surveillance activities, making sure that it has a reliable mechanism for capturing the information that is most likely to be helpful for quality assurance. In particular, more detailis required on:

- Means;

- Triggers;

- Mental health care; and

- Communication/collaboration with the chain of command

- Recommendation 49: The US Department of Defense Suicide Event Report may serve as a useful template for suicide surveillance data.

- Recommendation 50: The clinical suicide investigation should be used to capture the data needed for suicide surveillance; investigators should be trained in the use of the suicide event report.

- Recommendation 51: For the present, the CF should focus on completed suicides as it fine-tunes its suicide surveillance system. However, in the future, the CF should look towards finding ways of capturing similar information on serious suicide attempts as well.

- Recommendation 52: The CF should continue to monitor suicide risk factors (including barriers to mental health care) using its periodic Health and Lifestyle Information Survey.

- Recommendation 53: The CF should specifically look at suicide rates in currently serving and former members in its planned cancer and mortality linkage study.

- Recommendation 54: The CF should develop a set of performance measures (and ways to capture these) for its suicide prevention program. The completed suicide rate will have limited value as a performance measure because the numbers are expected to be low enough that detecting important changes will be difficult. Thus, other performance measures will be needed (such as the fraction of those with mental health problems who are in care, the prevalence of suicidal ideation, the fraction of mental health patients with a complete suicidality assessment documented in their medical record, etc.).

1 This will be discussed in detail in the following two sections.

2 These systems will be discussed in detail later in this report.

3 The current prevalence is unknown, but results from the 2008 Health and Lifestyle Information Survey will shortly provide a more current PTSD point prevalence estimate for the CF population as a whole.

4 That is, they ahve a score of 50 or greater on the PTSD Checklist, Civilian Version (PCL-C)

5 The median delay for treatment seeking for service-related PTSD in the CF was on the order of 5.5 years in 2002, but more recent data suggests that the delay to first care is far shorter currently.

6 The USAF's suicide prevention program will be reviewed in detail in a later section.

7 The USAF's choice of terminology here is unfortunate: In this context, "hands off" does not mean lack of leader or investigator involvement in the psychological well being of the member. Quite the contrary, the intent of the policy is to enhance such involvement.

8 Data collected from more than 10,000 CF members returning for deployment in Afghanistan showed that only about 5% indicated that they would think less of a team member who was receiving mental health counselling.

9 The CF spends approximately six times as much per capita on mental health care as does Canada as a whole.

10 Data on baseline characteristics that influence prognosis are important because these are required to perform valid comparisons.

11 Suicide BOI's may, of course, serve other purposes.

12 1972 was selected because is the first year in which reliable electronic personnel data are available in the CF.

13 Such linkage studies have been performed in Gulf War veterans from a number of countries, and no increased risk of suicide has been demonstrated relative to veterans of the same era wo did not deploy in that conflict.