Summative Evaluation Of The Canadian Forces Health Services Response To The Covid-19 Emergency

Acknowledgements

The Directorate of Health Services Quality and Performance would like to thank the Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) Evaluation Steering Committee for their timely input and support throughout the process. Many partners in CFHS headquarters and in the field contributed, and we would especially thank those who hosted the field visit and facilitated data gathering. We also extend our gratitude to all the Defence Team members who took the time to provide their input and share their experiences.

Wildfires in Long Term Care

Small fires

Jumping

Spreading

Everywhere.

Despite best efforts

Best practices

And battened down hatches

It gets in.

Undeterred

Persistent

Invisible

Wreaking havoc.

Swab levels upped

Staff on alert, on edge

All hands-on deck

But there is no perimeter

Death's door

Sadly everywhere

Everyone helping

Everyone praying

That the rains will come

Swiftly, and bucket down

And suffocate the wildfires

That are COVID19.

Make it visible

Clean, test and find it

Protect and reinforce the troops

Rinse and repeat

We cherish our fallen

Throughout

With hope renewed

For a world where seniors can live freely again.

Dr. Heather Galbraith, Family Physician

Royal Canadian Navy, 1 May 2020

Table of Contents

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- 1.0 Executive Summary

- 2.0 Context

- 3.0 Key Findings

- 3.1 Cluster I Institutional health services support of CAF operational capabilities

- 3.2 Cluster II Logistics of the response

- 3.2.1 Effectiveness: Epidemiological surveillance

- 3.2.2 Effectiveness: Lessons Learned

- 3.2.3 Effectiveness: Communications

- 3.2.4 Efficiency: Epidemiological Surveillance

- 3.2.5 Efficiency: Lessons Leaned

- 3.2.6 Efficiency: Communications

- 3.2.7 Governance: Epidemiological Surveillance

- 3.2.8 Governance: Lessons Learned

- 3.2.9 Governance: Communications

- 3.3 Cluster III Institutional health support of civilian health system through RFAs

- 3.4 Cross-cutting issues: Gender, diversity & inclusion

- 4.0 Conclusions

- 5.0 Summary of Recommendations

- Annexes

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- ADM (PA)

- Assistant Deputy Minister Public Affair

- AFU

- Air Filtration Unit

- ARA

- Authority Responsibility Accountability

- ADM (RS)

- Assistant Deputy Minister Review Services

- BCP

- Business Continuity Plan

- BRP

- Business Resumption Plan

- B/WSurg

- Base/Wing Surgeon

- CAF

- Canadian Armed Forces

- CDS

- Chief of the Defence Staff

- CE

- Construction Engineering

- CF H Svcs Gp

- Canadian Forces Health Service Group

- CFHS

- Canadian Forces Health Services

- CFB

- Canadian Force Base

- CFHIS

- Canadian Forces Health Information System

- CDS

- Chief of the Defence Staff

- CDO

- Chief Dental Officer

- CDU

- Care Delivery Unit

- CFB

- Canadian Forces Base

- CFTPO

- Canadian Forces Task Planning and Operation

- CFJP

- Canadian Forces Joint Publication

- CMED

- Central Medical Equipment Depot

- CMP

- Chief of Military Personnel

- CO

- Commanding Officer

- CONPLAN

- Contingency Plan

- CoC

- Chain of Command

- C2

- Command and Control

- COM

- Commander Canada Command

- CJAT

- Commander's Joint Assessment Team

- CJOC

- Canadian Joint Operations Command

- CGP

- Canadian General Population

- CSM

- Clinic Service Manager

- CT

- Contact Tracing

- DAOD

- Defence Administrative Orders and Directives

- DentIS

- Dental Information System

- DDC

- Dental Detachment Commander

- DFHP

- Directorate of Force Health Protection

- DGHS

- Director General Health Services

- DND

- Department of National Defence

- DLLS

- Defence Lessons Learned System

- DLLP

- Defence Lessons Learned Program

- D HS Q&P

- Directorate of Health Services Quality and Performance

- DHSO

- Directorate Health Services Operations

- DSG

- Deputy Surgeon General

- GBA+

- Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- GDMO

- General Duty Medical Officer

- GMH

- General Mental Health

- HHR

- Health Human Resources

- HSS

- Health Service Support

- HS

- Health Services

- HQ

- Headquarters

- IPAC

- Infection Prevention and Control

- IT

- Information Technology

- JTF

- Joint task forces

- LTCF

- Long Term Care Facility

- MHCP

- Mental Health Care Provider

- MMAT

- Multipurpose Medical Assistance Teams

- MPC

- Military Personnel Command

- NATO

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- Op

- Operation

- PCSM

- Primary Care Services Manager

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PHM

- Public Health Measures

- PI

- Pandemic Influenza

- PLRD

- Programme des leçons retenues de la Défense

- PML

- Preferred Manning Levels

- PSS

- Psycho-Social Services

- PM

- Program Manager

- PSU

- Primary Sampling Unit

- QC

- Quality Council

- RFA

- Request for Federal Assistance

- RSurg

- Regional Surgeon

- SG

- Surgeon General

- SME

- Subject Matter Expert

- SOODO

- Standing Operations Order for Domestic Operations

- TBS

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- TOR

- Terms of Reference

- WO

- Warrant Officer

- WW

- World War

1.0 Executive Summary

1.1 Background

On March 2, 2020 the Chief of the Defence Staff of the Canadian Armed Forces activated the pre-existing, multi-phased Contingency Plan (CONPLAN) LASERFootnote 1 in response to a global pandemic of COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virusFootnote 2.Operation LASER (Op LASER) provided the basis for a coordinated Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) effort to maintain operational capability and support civil authorities. Due to the health-centric nature of the emergency, Op LASER was predominantly designed to protect the health of the force and, therefore, significantly implicated the Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS), the organization ordinarily responsible for the provision of health care to CAF members both in-garrison in Canada and abroad on operationsFootnote 3 as well as force health protection.

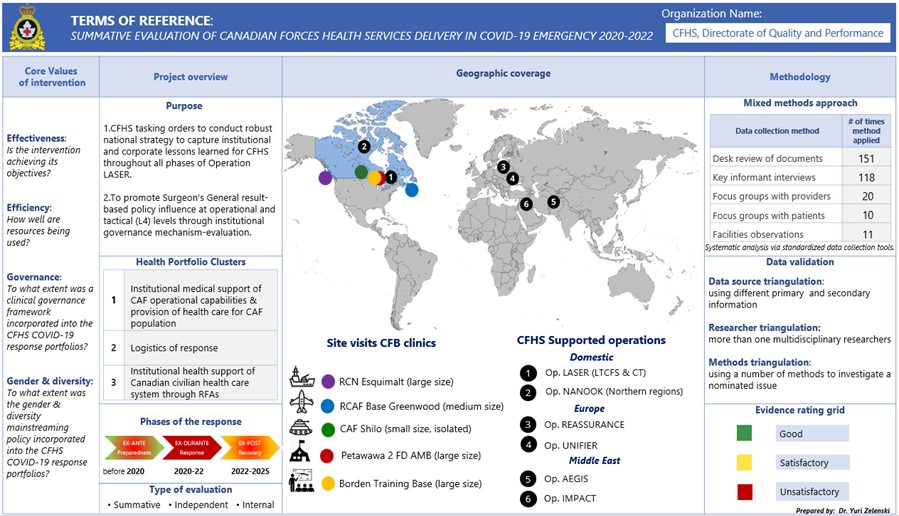

As a part of the CFHS response, the Directorate of Health Services Quality and Performance (D HS Q & P) was taskedFootnote 4,Footnote 5 to implement a robust national strategy to capture institutional lessons learned (LL) for CFHS throughout all phases of Op LASER. Given the unprecedented scope and complexity of the efforts required of CFHS in response to COVID-19, it was determined that the LL activity could only achieve the necessary level of quality, objectivity and comprehensiveness if executed under the auspices of the CFHS Evaluation Program as a structured Summative Evaluation of the Canadian Forces Health Services Response to the COVID-19 Emergency.

1.2 Purpose

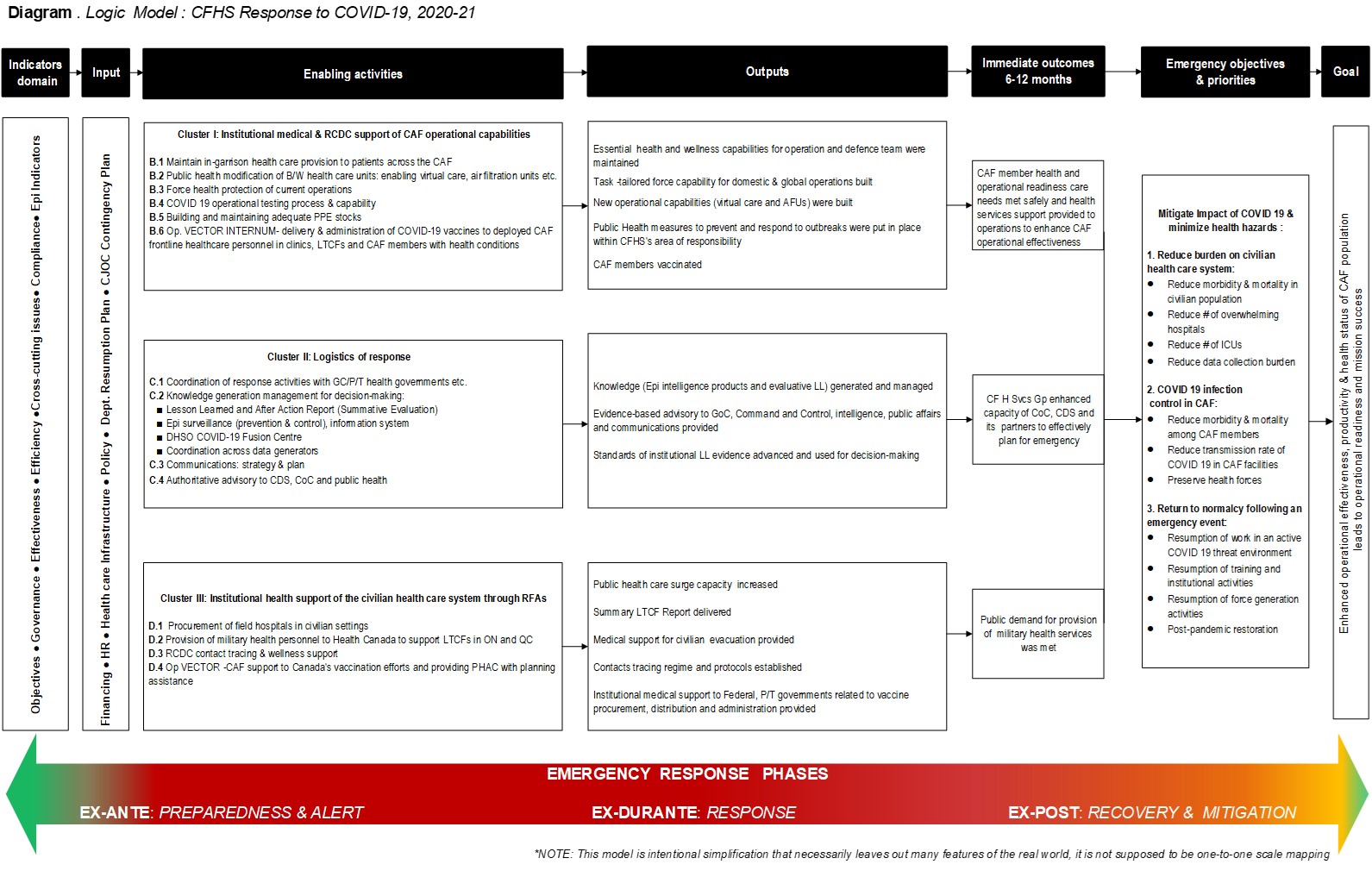

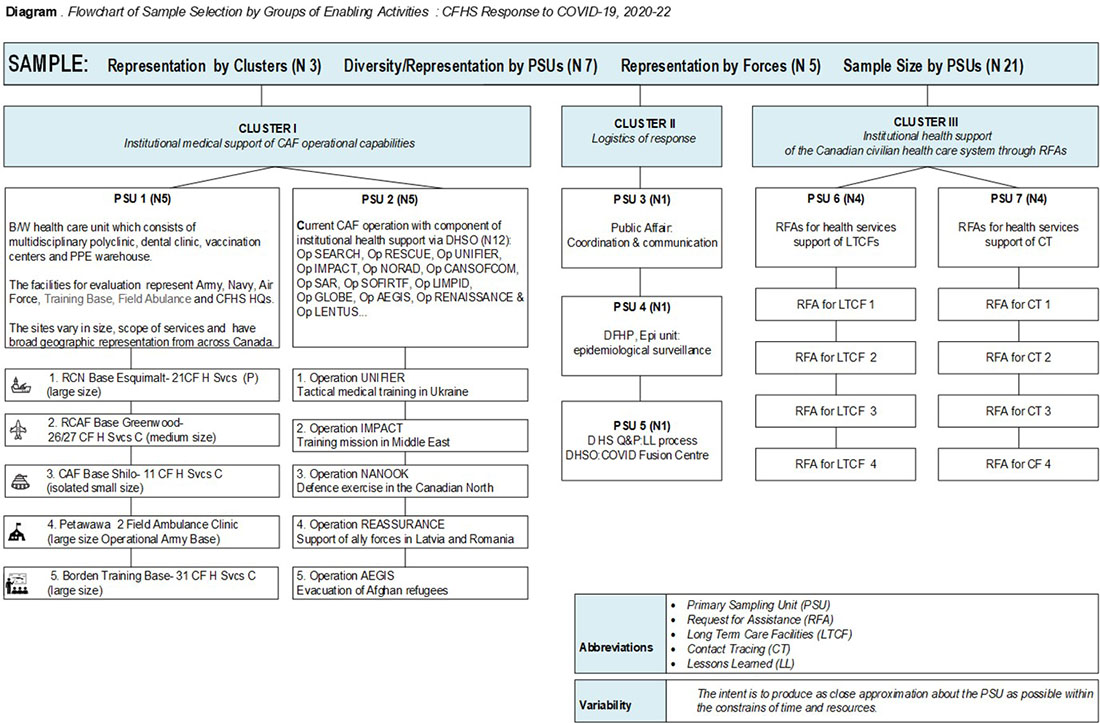

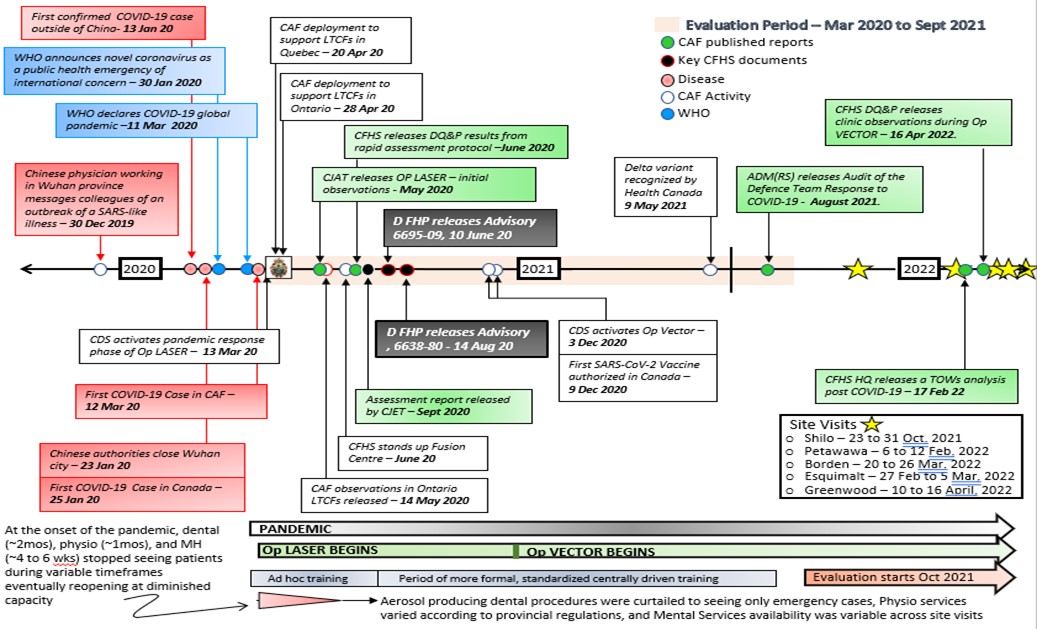

The Evaluation covers the period from March 2020 to September 2021 (see Term of Reference in Annex A) and focuses on key evaluation questions derived from the perspectives of CFHS executive members via a broad organisational scoping exercise. The exercise shaped a shared vision of a summative mapping design of the array of complex, phased, and clustered emergency activities that depict how the CFHS contributed to achieving CONPLAN/Op LASER strategic objectives (see Logic Model in Annex B).

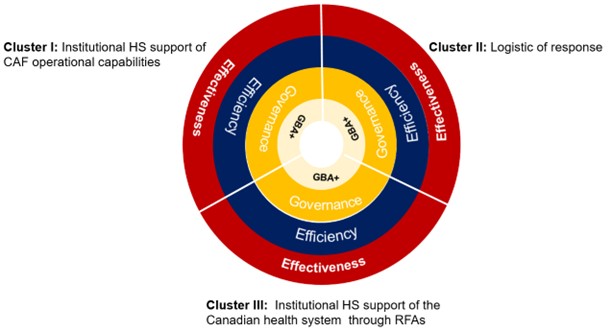

The mapping exercise conceptualized CFHS's activities as falling into three main Clusters: (I) institutional health services support of CAF operational capabilities; (II) logistics of response and; (III) institutional health support of Canadian civilian health care system through Requests for Federal Assistance (RFAs). Performance in each of these Clusters was examined through the lenses of effectiveness, efficiency, governance (particularly clinical governance), and Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+).

This report presents the findings and recommendations produced to address the key evaluation questions within each of the three Clusters of CFHS activity. It is intended to produce insights into what worked well and what can be improved in CFHS's response to COVID-19 with the anticipation that CFHS senior decision-makers can use these insights to improve the organization's ability to plan for and respond effectively and efficiently to future health emergencies.

1.3 Methods

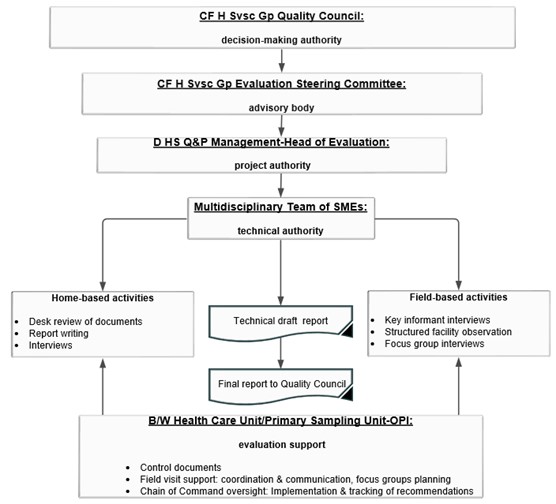

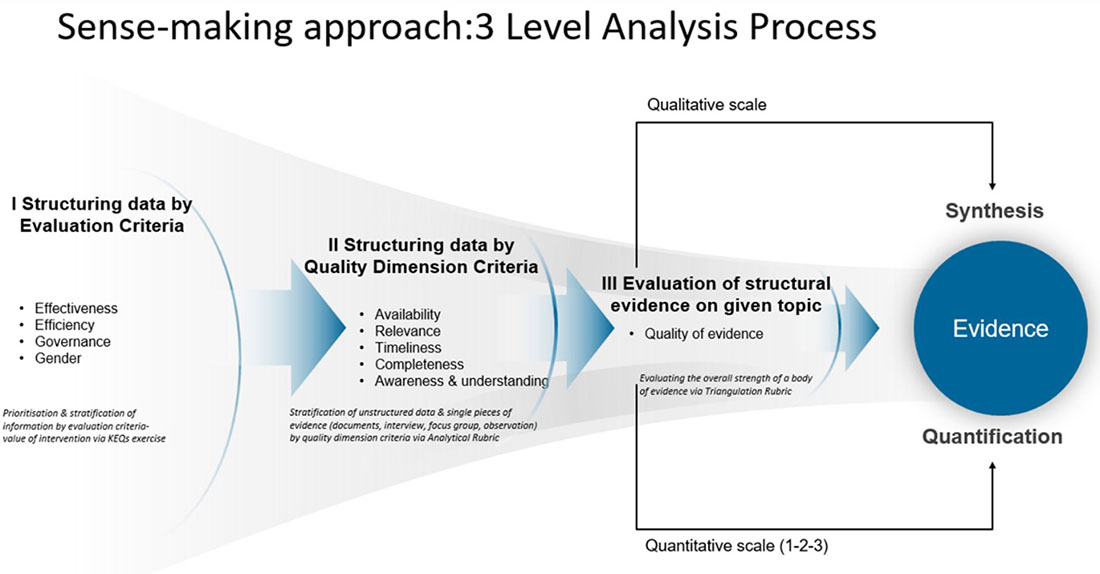

This evaluation used a mixed method approach and techniques of data collection, driven by the specific needs for information linked to the key evaluation questions. Data was collected from a variety of primary (e.g. interviews, observation and focus groups) and secondary data sources (document and literature review as well as Canadian Forces Health Information System (CFHIS), Dental Information System (DentIS) and DND reports and publications databases). Detailed methodology can be found in Annex C. Collected data from multiple sources and lines of evidence were analysed, interpreted and triangulated by the evaluation team:

| Name | Organization |

Professional Designation |

Role |

|---|---|---|---|

Dr. Yuri Zelenskiy |

CFHS DHS Q&P |

MD, MPH, MPHI |

Head of Evaluation Principal Investigator |

Dr. J.G.(Jim) Kile |

CFHS DHSO |

OMM, CD, MSc, MD, CCFP(EM), Col (retired) |

Subject Matter Expert |

Joanne Kile |

CFHS |

CD, RN, BScN, Lt(N) (retired) |

Principal Investigator |

Dr. Marcie Lorenzen |

CFHS |

MD, LCol (retired) |

Subject Matter Expert |

1.4 Findings

From the value criteria point of view of health interventions, the CFHS strategic objectives assigned within Op LASER such as maintaining the operational effectiveness of CAF, provision of health care to CAF members and support of the Government of Canada were achieved. Moreover, the CFHS retained the core operational capability to support all CAF missions – including pre-existing operations as well as those associated with Op LASER. While the extent to which the objectives were achieved does vary among the Clusters, no evidence of systematic failure was identified (see Figure 1). The CFHS was able to deliver on its mandate during all phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Cluster | Activities |

Effectiveness |

Efficiency |

Governance |

Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I |

Institutional health services support of CAF operational capabilities |

Good |

Satisfactory |

Good |

Good |

II |

Logistics of response |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Good |

III |

Institutional health services support of the civilian health system through RFAs |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

Satisfactory |

However, as indicated by the value criteria, the CFHS performed less well in terms of efficiency of the response, which imposed additional potentially avoidable burdens on a health system already stressed by pre-existing shortages of health care personnel (the CAF has less than 50% of required physicians available to deploy along with 75% of nurses and 65% of medical technicians). In short, the scores achieved do not reflect the heavy toll exacted from the personnel within the CFHS who made the extensive and sustained response possible despite the myriad of challenges and inefficiencies.

1.5 Conclusion

Based on the evidence examined during the Evaluation, CFHS uninterruptedly provided essential mission-critical health services, medical and dental direction and expert advice in support of public health protection and supplied health services forces to Joint Task Forces (JTFs) engaged in current operations in Canada and abroad. The personal health and safety of CAF personnel were effectively protected, allowing the CAF to maintain operational effectiveness, and readiness for missions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In-garrison health services and units rapidly implemented public health measures for infection control and ensured the safe continuity of care provision. Increased demand on the military health care system to ramp up a number of internal functions, such as epidemiological surveillance, as well as force generate an unprecedented number of personnel for RFAs was managed.

However, the Evaluation identified several factors that impacted the efficiency of the CFHS response to COVID-19, many of these adding to the organizational effort required for CFHS to achieve the successes it did. These included important gaps in planning and preparedness, most particularly the lack of a detailed and up to date medical CONPLAN and pre-existing human and other resource challenges. Similarly, there were findings related to pre-existing governance structures and processes that impeded CFHS's ability to execute required tasks in the context of the pandemic.

Notwithstanding these handicaps at the outset, the Evaluation also found CFHS personnel at all levels were able to develop and rapidly institute a number of innovations and adaptations to meet the multiple challenges and demands they faced. While largely effective, these measures were not without significant cost to the CFHS – particularly at the tactical level. As a result, CFHS should expect substantial challenges recovering from this extended surge posture.

2.0 Context

2.1 Historical Perspective

"The fear of influenza was constantly in minds [of the military healthcare providers during WWII] as a result of an experience in the First World War." When the Canadian Army was preparing for deployment, it was estimated that roughly 266,000 soldiers lost over a million training days per annum due to respiratory illnessFootnote 6. Later, when the 1957 influenza pandemic (caused by an H2N2 variant) began, CFHS leadership and their civilian counterparts "pondered the best approach to mitigate the disease's potential ravagesFootnote 7. As with the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, when Op LASER was first set in motion, the CDS activated CONPLAN LASER immediately after the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic, giving rise to the second activation of Op LASER.

2.2 Contingency Plan LASER

The CONPLAN LASER, which exists as an Appendix to Annex A of the CAF's Standing Operations Orders for Domestic Operations (SOODO), provides the "basis for a coordinated CF effort to maintain operational capability and support to civil authorities as directed by the CDSFootnote 8 ". It was a phased plan specifically developed to address a pandemic caused by influenza and served as the starting point for all activities and orders issued under Op LASER.

In accordance with the CONPLAN, the CAF's steady state is Phase I, which requires the CAF to maintain a perpetual state of pandemic readiness. A detailed summary of the aspects of the CONPLAN's design relevant to the matters examined in this Evaluation, along with a comparative analysis of the features of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic – upon which the current CONPLAN was based - is contained at Annex D.

2.3 Mounting Pressure

With the promulgation of the COVID-19-related Op LASER, CFHS experienced unprecedented pressures from several fronts. Firstly, an already depleted workforce was being directly (i.e. getting sick) or indirectly (e.g. death of a family member or loved one) impacted negatively by the virus, further reducing the available workforce. Secondly, while the demand for in-garrison health services decreased in some respects as CAF training wound down (e.g., physiotherapy consult,), it remained stable or increased in others (e.g., primary care, mental health). Thirdly, compounding an already distressed workforce, CFHS was required to rapidly force-generate drawing from institutional healthcare providers as a secondary source to augment force-generating unit efforts. Lastly, CFHS was required to maintain the current levels of integral medical and dental support to operations with the added responsibilities of controlling the spread and protecting the safety of mission troops and associated allies.

2.4 Command and Control

CFHS exists as a Level 2 organization within the CAF, with all other major force elements existing as Level 1 organizations. With few exceptions (such as the Disaster Assistance Response Team), health services elements are deployed to support these other elements. Planning for health services support under normal circumstances can be inefficient due to the need to work through a higher-level L1 organization that does not have the capacity or expertise to contribute to such specialized aspects of operations. However, this is generally mitigated through CFHS's ability to rely on doctrine, experience, and having time to absorb the extra steps of working through the L1. CONPLAN LASER, and the ensuing Op LASER, departed from normal operations in having health and its preservation as the overarching mandate, yet simultaneously reflected traditional domestic operational doctrine, which injected additional layers of non-health services command and control in a time-compressed setting. As will be explained in the Evaluation's findings, this configuration had a negative impact on CFHS's response to COVID-19.

2.5 Ongoing Modernization of Governance in the CFHS

The 2018 ADM(RS) Evaluation of Military HealthcareFootnote 9 recognized the need for CFHS to strengthen its clinical governance, including clarifying the Surgeon General's and Chief Dental Officer's (CDO) accountabilities, responsibilities, and authorities (ARAs) for respective medical and dental professional technical matters within the CAF. This includes acting as the CAF's Chief Medical Officer of Health, providing definitive public health advice. CFHS efforts to action ADM (RS) recommendations to firmly establish SG and CDO ARAs as the core of an updated and integrated governance framework were still very much in process when the COVID-19 pandemic was declared. As a result, CFHS was subjected to a sudden and unprecedented surge in demands for public health advice, which created heavy burdens on the Force Health Protection functions and professional-technical networks that inform and distribute that advice. For CFHS, meeting this demand was further complicated by continually evolving knowledge about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the need to align public health advice with multiple host jurisdictions within Canada and abroad.

2.6 Requests for Assistance

Throughout the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the CAF maintained critical operations while responding to the Government of Canada (GoC) Requests for Assistance (RFAs). These RFAs were launched under OP LASER, reflecting CONPLAN LASER's anticipation of the need for the CAF to provide forces to assist civilian authorities with the provision of essential public services impacted by a pandemic. From 19 February 2020 to 28 March 2021, the CAF supported 111 RFAs that varied in nature and complexity and included the repatriation of Canadians from abroad, support to identified Long Term Care Facilities (LTCFs) in Ontario and Quebec, as well as providing personnel to support the contact tracing efforts of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Throughout the RFA process, CFHS was the predominant CAF force generator for specialized positions responding to a high-profile, politically sensitive, startling situation in LTCFs impacted by the global pandemic whose effect and severity was changing rapidly.These missions comprised an unusual population and context for healthcare providers trained to support more typical military operations and were also complicated by important health regulatory jurisdictional considerations.

In sum, and in addition to the need to sustain essential healthcare in-garrison, Op LASER saw the largest number of health services personnel deployed concurrently in recent memory, requiring the CFHS to reach into clinics and lean heavily on Reserve Force members to fill the tasking.

3.0 Key Findings

3.1 Cluster I Institutional health services support of CAF operational capabilities

Description: Maintaining essential health services for CAF personnel is one of three explicit strategic objectives of CONPLAN LASER, translated in the 02 March 2020 Op LASER CDS Tasking Order into a tasking for CFHS to "continue to deliver (the) health mission to the CAF…". While many of the CAF's training and sustainment activities ground to a near halt with the imposition of strict public health measures on 13 March 2020, CFHS medical and dental clinics within Canada and abroad had to rapidly adapt their service delivery to be able to continue to provide essential healthcare to CAF members in a way that was safe for patients and staff alike. In addition, CFHS personnel and installations in support of extant deployed operations across the globe were required to take similar measures to protect their forces, with the usual logistical and contextual difficulties of deployment made even more challenging by the varied and evolving impact of the pandemic in different parts of the world. Cluster I examines how well CFHS maintained essential health services through its in-garrison and deployed health services establishments.

3.1.1 Effectiveness: Is the intervention achieving its objectives?

Finding: Public Health Measures (PHMs) instituted within the CFHS were generally effective in controlling the risk of transmission of COVID-19.

A virtual audit of the implementation of recommended infection prevention and control measures conducted in June 2020 across CFHS clinics indicated a high degree of compliance with most PHMs in the majority of locations. This was confirmed in more detail through on-site visits of the sampled clinics during the Evaluation.

The CAF achieved infection rates lower than background Canadian population ratesFootnote 10. In terms of outbreaks originating in CFHS clinics, these were limited and involved staff-to-staff transmission, indicating Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) measures and the Chief Dental Officer's Interim Clinical Directive: Dental treatment during the COVID-19 Pandemic at the patient interface were effective despite the inherent increased risk of exposure in the patient care setting. As the pandemic continued and the nature of the virus became better understood, CFHS implemented service delivery design adaptations and engineering controls that permitted increases in in-person healthcare delivery without increased risk of COVID-19 transmission.

The response to COVID-19 hastened the CFHS's development of IPAC-relevant capacities and innovations, such as: enhanced ability to perform contact tracing; improved engineering controls (such as Air Filtration Units for dental procedures); evidence-based decision-making aids; and a rapidly deployable communicable disease testing capability. As the pandemic continued, these service delivery adaptations and innovations permitted increases in healthcare delivery in-garrison and effective Health Services Support (HSS) in deployed settings without a significant increased risk of COVID-19 transmission.

Finding: Overall, CFHS was able to sustain essential in-garrison and deployed health services during the initial phases of the response to COVID-19. There is, however, evidence that the CFHS will struggle to meet both deferred and, in the case of mental health, growing healthcare demand while also providing support to increasing in-garrison operations over an extended CAF recovery and reconstitution period.

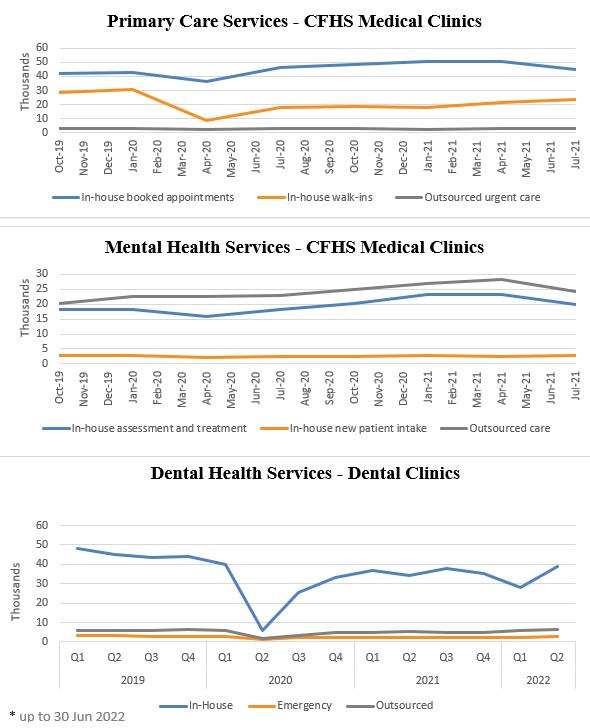

The institution of PHMs and the requirement for enhanced IPAC measures in the clinics significantly decreased their ability to provide in-person health services, particularly in the initial weeks of the response. Data collected from the CFHIS and DentIS indicate significant dips across all categories of health services delivered (see Fig 2). This was most marked for dental and physiotherapy services due to the higher infectious disease transmission risk and/or the lack of suitable alternatives to in-person service delivery to meet care needs.

Figure 2 CFHS health care services utilisation

Caption

Month |

In-house booked appointments (000s) |

In-house walk-ins (000s) |

Outsourced urgent care (000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

October 2019 |

40 |

30 |

8 |

November 2019 |

42 |

29 |

8 |

December 2019 |

43 |

28 |

9 |

January 2020 |

45 |

27 |

9 |

February 2020 |

45 |

25 |

9 |

March 2020 |

35 |

15 |

10 |

April 2020 |

30 |

10 |

10 |

May 2020 |

32 |

12 |

10 |

June 2020 |

33 |

13 |

9 |

July 2020 |

36 |

15 |

9 |

August 2020 |

38 |

17 |

8 |

September 2020 |

39 |

18 |

8 |

October 2020 |

40 |

20 |

8 |

November 2020 |

41 |

22 |

8 |

December 2020 |

42 |

23 |

8 |

January 2021 |

43 |

24 |

8 |

February 2021 |

45 |

25 |

8 |

March 2021 |

48 |

26 |

8 |

April 2021 |

48 |

27 |

8 |

May 2021 |

49 |

28 |

8 |

June 2021 |

50 |

28 |

8 |

July 2021 |

50 |

29 |

8 |

Month |

In-house assessment & treatment (000s) |

New patient intake (000s) |

Outsourced care (000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

October 2019 |

20 |

2.0 |

15.0 |

November 2019 |

21 |

2.0 |

15.5 |

December 2019 |

21 |

2.0 |

16.0 |

January 2020 |

22 |

2.0 |

16.5 |

February 2020 |

22 |

2.0 |

17.0 |

March 2020 |

20 |

1.5 |

17.5 |

April 2020 |

18 |

1.2 |

17.8 |

May 2020 |

19 |

1.3 |

18.0 |

June 2020 |

20 |

1.5 |

18.3 |

July 2020 |

21 |

1.6 |

18.5 |

August 2020 |

21 |

1.7 |

18.8 |

September 2020 |

21 |

1.8 |

19.0 |

October 2020 |

21 |

2.0 |

19.2 |

November 2020 |

22 |

2.0 |

19.5 |

December 2020 |

22 |

2.0 |

19.7 |

January 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

February 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

March 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

April 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

May 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

June 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

July 2021 |

22 |

2.0 |

20.0 |

Quarter |

In-house (000s) |

Emergency (000s) |

Outsourced (000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

Q1 2019 |

50 |

6 |

2 |

Q2 2019 |

52 |

6 |

2 |

Q3 2019 |

53 |

6 |

2 |

Q4 2019 |

54 |

6 |

2 |

Q1 2020 |

50 |

6 |

2 |

Q2 2020 |

10 |

7 |

2 |

Q3 2020 |

25 |

6 |

2 |

Q4 2020 |

30 |

6 |

2 |

Q1 2021 |

45 |

6 |

2 |

Q2 2021 |

43 |

6 |

2 |

Q3 2021 |

40 |

6 |

2 |

Q4 2021 |

38 |

6 |

2 |

Q1 2022 |

37 |

6 |

2 |

Q2 2022 |

35 |

6 |

2 |

COVID-19 similarly disrupted ongoing deployed operations and a large proportion of the standard HSS plans and support processes had to be adapted to accommodate pandemic conditions, creating significant challenges early on. CFHS was able to adapt and continue to provide effective HSS to deployed operations (including communicable disease control support), largely due to the clear priority of filling additional taskings and providing other forms of support to these missions over other competing activities.

Clinics prioritized the care provided to ensure that urgent requirements were met while adaptations to service delivery design that would permit increased care delivery were being planned and implemented. Patients and Health Care Providers (HCPs) who were interviewed generally understood the requirement to scale down services and felt essential needs were met. Data for externally accessed primary care services (see Fig. 2) does show a decline in utilization during the first quarter after the pandemic was declared, suggesting that overall CAF member demand for healthcare – whether delivered directly by CFHS or externally in a civilian setting - was restrained due to limited accessibility of health care. This would be consistent with the trend in Canada in general due to curtailed levels of individual activity, lower incidences of other infectious illnesses during lock-downs, and fear of contracting COVID-19 from exposure to other patients in a healthcare setting.

The in-garrison demand for essential patient care being significantly higher in medical care than in dental services afforded medical clinics less time and capacity than their dental counterparts to respond to pandemic-related requirements and changes.

It was suggested by some patients and HCPs that PHMs were overly conservative in some situations, particularly where there was low community prevalence of COVID-19. Decisions to curtail in-person services in favor of no or virtually-delivered care in these situations may have conferred greater overall health risk than was offset by the decrease in risk of patients or staff contracting COVID-19 through in-person healthcare activities.

During the latter part of the evaluation period, data from CFHIS shows trends across most health services for higher levels of demand than existed pre-pandemic, with trajectories that were continuing to rise. While some of this was likely due to pent up demand for services that had been deferred earlier in the pandemic, there is evidence that the pandemic has resulted in increased incidences of mental health issues in the general population. Early indications are that this phenomenon might also apply to CAF members, which will further strain CFHS primary care mental health care capacity.

Recommendation #1: CFHS should continue efforts to implement value-based healthcare related initiatives to support its reconstitution by better balancing healthcare demand and capacity.

3.1.2 Efficiency: How well are resources being used?

Finding: CONPLAN LASER was largely ineffective in supporting an efficient CFHS in-garrison response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONPLAN LASER (October 2012) was outdated, untried, and contained insufficient detail and scope to inform the efficient mobilization of a system-level health services response to a pandemic. The complementary medical response plan referred to in Appendix 4, Annex A of the CONPLAN as a Phase I requirementFootnote 11 does not appear to have been developed, or, if developed, was not finalized, exercised and available to medical planners. Two of the three strategic objectives of the CONPLAN (to maintain essential health services for CAF personnel and to provide assistance to civil authorities), from the CFHS perspective, operate in direct competition with one another given that support to RFAs in the event of a health crisis should reasonably have been expected to divert finite health human resources from the ongoing tasks of force protection, delivery of essential care to CAF members, and preservation of HSS to ongoing operations. While this level of surge across multiple lines of CFHS operation may have been a feasible strategy during the brief influenza driven Phase III envisioned in the CONPLAN, it was not a realistic expectation for the sustained COVID-19 pandemic.

While the exigencies of an in-garrison care response to a pandemic were not contemplated in any detail within the CONPLAN, nor did they appear to be covered to any useful extent within most Business Continuity Plans (BCPs) that generally apply to base/wing level operations. This created an important planning gap and confusion when clinic "operations" became an explicit component of Op LASER. Clinic BCPs, where they existed, varied in quality and utility of health services-specific content. Further, they relied on the availability of resources, such as IT, that proved insufficient for the magnitude of the emergency.

Most evaluation informants were unaware of how to access the CONPLAN LASER and, therefore, unfamiliar with the specifics of its contents, even at the headquarters level. This, combined with the gaps between the CONPLAN and existing BCPs, led to a significant level of potentially avoidable effort expended in the planning and executing of the CFHS response while the emergency was unfolding.

Recommendation #2: CFHS should work with CJOC and other applicable organizations to ensure all pandemic related contingency plans (LASER, its subordinate health and Business Continuity Plans) are updated, incorporating improvements identified through this Evaluation and other LL activities and ensuring the plans are flexible enough to accommodate a spectrum of infectious disease pandemics. Innovative approaches and tools that proved valuable in responding to the pandemic and can be adapted to other contingencies should also be preserved through codifying them in the plans.

Finding: CFHS rapidly instituted adaptations to services to permit continued provision of high priority care in a pandemic environment, but not without some cost to productivity. The safety and quality of some of the adaptations and the risk of deferred services have yet to be assessed.

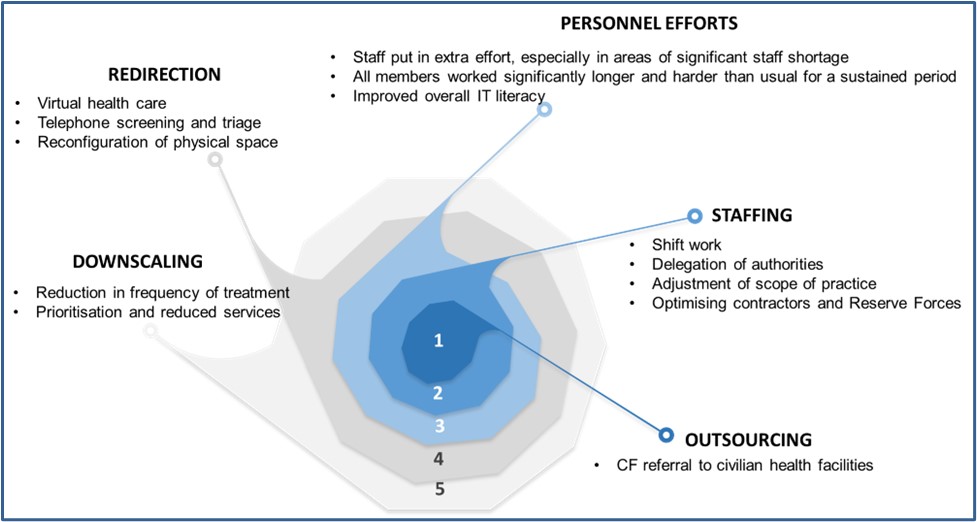

A number of adaptations were identified through interviews and site visits conducted as part of the evaluation process and are displayed in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 Mechanisms of sustainability of health care provision

Caption

The spiral diagram illustrates the key adaptations implemented to sustain health care provision in CAF clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Outsourcing:

- CF referral to civilian health facilities

- Staffing:

- Shift work

- Delegation of authorities

- Adjustment of scope of practice

- Optimising contractors and Reserve Forces

- Personnel Efforts:

- Staff put in extra effort, especially in areas of significant staff shortage

- All members worked significantly longer and harder than usual for a sustained period.

- Improved overall IT literacy

- Redirection:

- Virtual health care

- Telephone screening and triage

- Reconfiguration of physical space

- Downscaling:

- Reduction in frequency of treatment

- Prioritisation and reduced services

These adaptations were crucial in maintaining health care services amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic, ensuring that CAF clinics could continue to meet the needs of their patients.

Overall, it was found that efforts to reduce the demand for care, redirect patients to other sources of care, outsource operations where possible, optimize capacity given available staff, and increase staff effort combined to make health care provision more sustainable both in-garrison and in deployed settings.

Guidance was provided from higher headquarters on prioritization of care, although this was clearer and timelier for dental than medical care. The ability to triage patients into categories of priority with confidence and consistency (e.g. dental or physiotherapy services) and the nature of the service lending itself to safe deferral of significant numbers of non-urgent patients were also factors.

Virtual Care (VC) – Significant and enduring advances in the use of VC to augment provision of healthcare in the CFHS resulted from necessity due to pandemic restrictions. Data collected through the evaluation period demonstrated a strong acceleration of VC use even when PHMs were eased and in-person care became safer. This rapid institution of VC - notwithstanding its use outside of CFHS for some time – resulted in varying staff comfort levels. Considerable variation was found in how well VC was leveraged at the tactical level to support continuity of services. In one location, where the mental health staff moved quickly to adopt VC, wait times for services steadily decreased from pre-pandemic levels without increasing reliance on referred-out services. In contrast the converse was true in locations where staff were more reluctant or not as well equipped and supported in their adoption of VC.

Some issues were identified with the rapid shift to VC in the CFHS context, where the inability to integrate VC software into the extant CFHIS and the logistics of its use in clinics without WiFi capability posed significant challenges. These included a shifting of administrative burden for the management of patient encounters from clerical staff to HCPs, and the need to extend appointment lengths to deal with this as well as unreliable technology. Additionally, team-based care was not easily coordinated in the absence of mature IT enabled VC business processes. Some concerns were also raised about the clinical appropriateness of VC use to such a significant degree, highlighted by reports of patient safety incidents in which VC use was identified a causal factor; however, investigating this is outside the scope of this evaluation.

Recommendation #3: CFHS should evaluate the safety, quality and integration of virtual care use by its healthcare providers with the objective of identifying and standardizing best practices for clinically appropriate and efficient use of virtual care across the health system.

Human Resources – At several sites, particularly early in the pandemic, most onsite healthcare professionals were Calian©contractors as their contracts precluded their working outside of the clinic. Having a high proportion of contracted HCPs on staff pre-pandemic was, therefore, seen as facilitating efficiency in preserving health services. Some adaptations to HCP scopes of practice to optimize use of more available health care providers were developed and authorized by the Surgeon General centrally. In other cases, adaptations to clinical roles and scopes of practice were local. Most often, local adaptation saw the re-assignment of personnel whose primary functions diminished due to overall reductions in some health-related services (e.g., dental hygiene procedures that were deemed non-essential and highly restricted, dental personnel offering support to vaccination clinics as assistant immunizer or for immunization data entry). There was also a shift seen from in-person triage and screening by clinicians to telephone screening of patients performed by clerical staff to manage healthcare access. Any training and protocols to support the safe execution of this new duty were generated locally and Quality Assurance to monitor compliance with standards not evident. Some clerks were uncomfortable with this new responsibility.

Other Factors - Strong support from the Directorate of Force Health Protection (DFHP) personnel helped build communicable disease control and IPAC capability in local and regional CFHS staff and support clinics and the CAF in responding effectively and efficiently to the pandemic. This support took the form of epidemiological data, scientific knowledge products (such as the Fusion Centre Reports), IPAC guidance, risk stratified decision-making frameworks, and regular teleconferences to provide updates and answer questions from professional-technical authorities across the CFHS.

The joint DFHP / D Dent Svcs / RCDC COVID-19 Intervention Team study related to efficacy of air filtration units is another example of a scientific knowledge product as well as joint collaboration.

A number of training products were developed centrally to better prepare staff to work safely in a pandemic environment (e.g. PPE use instruction). These were well received; however, would have better contributed to system efficiency if they had been available before clinic leaders were required to develop training locally to meet the immediate needs.

Recommendation #4: CFHS should consider routinely creating in advance any training materials necessary to instruct personnel in the use of any product stockpiled for contingencies.

The rapidity of the changes required to provide care in a pandemic environment as well as the relative immaturity of CFHS's Quality Improvement (QI) and Performance Measurement programming, however, meant that many pandemic related adaptations, particularly for medical services, occurred without the benefit of structured QI methods. Such methods would have enabled CFHS to better assess and refine the changes, systematically identify risks to the quality and safety of the healthcare provided, and approach scale and spread with deliberation to facilitate efficient standardization of good practices and minimize duplication of effort.

Recommendation #5: CFHS should continue to develop and implement its Quality Improvement (QI) program. Ensuring all personnel are able to apply QI-based methods when making changes to services will help ensure quality and safety are sustained or improved when circumstances force adaptations to service delivery design.

Finding: CFHS's ability to respond efficiently to the pandemic was impeded by the lack of several important resources and enablers.

The demands of Op LASER exacerbated pre-pandemic system-wide and/or local challenges. Several factors were found to have impeded the efficiency of the clinics' response including:

- Pre-existing personnel shortages or issues

- Insufficient IT equipment and supports to implement BCPs at baseline and slow augmentation at most locations

- Pre-existing infrastructure limitations

- Lack of pre-existing platforms and capacities to facilitate efficient passage of information, both command and control and professional-technical

- Limited or delayed guidance and training supports from headquarters

- Limited IPAC program capacity

- Limited structures for consistent and effective collaboration between medical and dental services

Human Resources – Pre-pandemic shortfalls of health care personnel eroded the robustness, efficiency, and sustainability of the response to COVID-19. CFHS was well below Preferred Manning Levels (PML) in key health services trades and was actively staffing public service vacancies and working with Calian to fill open contractor positions before the declaration of the pandemic. Data from the last quarter of FY 19/20 indicates seven (7) of the 16 health services occupations were below PML, with Medical Officers at the Captain (working) rank at 55 % of PML. There was no surge capacity to accommodate additional work or compensate for diminished productivity and loss of staff needing to attend to pandemic-related social impacts. Senior Medical Authorities, already working at capacity, had significant workload added to their plates as linchpin public health advisors for their clinics and supported bases and units.

Attrition – always a risk for highly employable health services personnel – was cited by some as increasing during the pandemic, with its impact further exacerbated by an inability to move public service staffing processes forward in the context of overarching DND business continuity challenges.

Finally, it must be noted that some clinics also contributed personnel to both new pandemic-driven and ongoing operational taskings, regardless of CFHS efforts to minimize pulling personnel from clinics.

Efficient mitigations for personnel challenges were complicated by the asymmetrical impact of the pandemic across different healthcare service areas and across different categories of worker within CFHS's blended workforce. Contract HCPs were not able to be accommodated with paid leave or part-time remote work in the same way as other team members and were heavily relied on by medical clinics to sustain services. Conversely, in some dental clinics, contracted HCPs were placed in abeyance or their hours reduced. Unequal access to COVID-19 vaccination was also a significant concern for contractors. In short, there were perceptions of significant unfairness stemming from differences in how Defence Team members were managed during the pandemic. This perception, combined with the weight of overwork and personnel concerns associated with COVID-19 as a personal health threat, has negatively impacted team cohesion and diminished morale.

Recommendation #6: CFHS should continue efforts to conduct a comprehensive and realistic review of its health human resource needs, ensuring resourcing is sufficient to provide a reasonable degree of surge capacity if required.

Information Technology –IT resource constraints significantly exacerbated the human resources challenges described above. Questionnaires, interviews and site visits revealed a variable range of information technology available to support health services, which directly impacted the clinics' ability to provide and sustain essential services efficiently. For example, clinic business continuity plans modified for the COVID-19 crisis relied heavily on IT support. With the sudden shift to teleworking (IAW CDS direction) by CAF/DND, the demand for proper C2 capability overwhelmed the IT and IM resources. Some organizations had laptops and priority DWAN access, while others did not. Only one clinic reported being fully equipped by the supporting base to facilitate healthcare business continuity as a priority. The short and mid-term IT shortages resulted in workarounds, some of which were sanctioned while others were not. Some resorted to using unsecured freeware, cross-platform, centralized instant messaging (IM) and voice-over-IP (VoIP) technology such as WHAT's App©and personal devices to maintain a modicum of communication.

Information management was also challenging. Pre-pandemic, there was no comprehensive, nationally accessible, and consistently used Information Management platform solidly in place for CFHS. Much of how the high volume of information important to coordinate the CFHS response to COVID-19 was collected, disseminated, and stored was created 'on the fly'. Tactical units found there was an overwhelming amount of information, at times, that needed to be sorted through to determine actions to be taken. Medical clinics needed to individually integrate information from a variety of sources early in the pandemic, resulting in a response tailored to local conditions but also diminishing efficiency. Similarly, they were largely on their own to interpret more general information and provide detailed guidance to their staff, often in the form of Standard Operating Procedures developed by each clinic in parallel.

The requirement to provide numerous ad hoc reports and returns up to headquarters in the absence of pre-existing databases also detracted from efficiency.

Recommendation #7: CFHS should continue efforts to develop and implement an effective Information Management capability, leveraging the upcoming roll-out of D365.

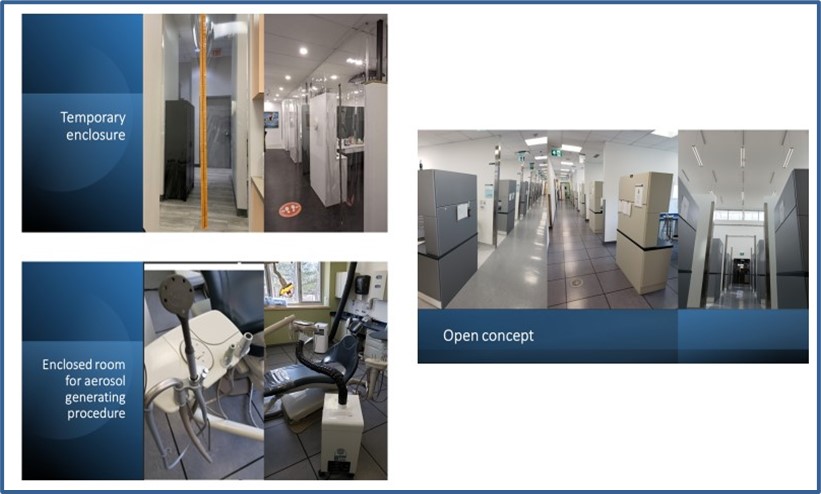

Infrastructure – The rapid and consistent institution of public health measures within CFHS spaces so that services could be safely sustained was also challenged by variations in clinic infrastructure, particularly in older establishments awaiting recapitalization. Infrastructure and base Construction Engineering support figured significantly as an attenuator or amplifier of SARS-CoV-2 spread in different CFHS settings. Differences in operatory room design (open vs. closed) across dental clinics impacted the ability of these clinics to institute required IPAC measures and, in turn, their ability to sustain or resume service delivery (see Figure 4). For medical clinics, each had differing capacity to adapt patient flow in ways that would minimize risk of transmission of infection based on the physical spaces they had to work with (see Figure 5).

Figure 4 Operatory rooms design

Caption

The photo collage illustrates the differences between open and closed operatory room designs in CAF dental clinics, highlighting their impact on Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) measures and service continuity. These design variations underscore the importance of infrastructure in maintaining effective IPAC measures and ensuring the continuity of dental services during the pandemic.

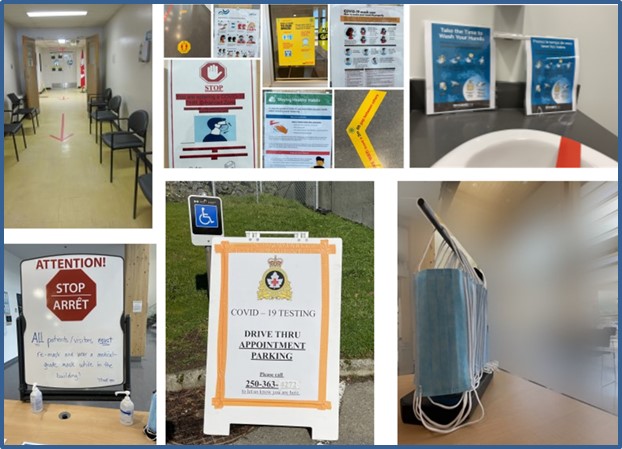

Figure 5 Pre-existing variations in clinic infrastructure

Caption

The collage highlights variations in CAF clinic infrastructure, influencing infection control measures, patient flow adaptations, and service delivery, underscoring the importance of infrastructure in maintaining effective infection prevention and control measures and ensuring the continuity of services in CAF clinics.

Recommendation #8: CFHS should continue to pursue recapitalization of old infrastructure with particular attention to facilities currently posing health and safety risk (including IPAC risk).

IPAC capacity – System-wide availability of IPAC expertise was significantly limited but of critical importance in the CFHS response to COVID-19. IPAC was not formally recognized and established as a program at CFHS headquarters (HQ) and there was only one IPAC certified Nursing Officer within CFHS who functioned as an IPAC advisor when needed prior to 2020. Further, IPAC functions in the clinics had generally been a secondary duty and not consistently performed. Of the clinics that were sampled, there was a correlation noted between having had on-site IPAC trained staff prior to the onset of the pandemic, and the effectiveness and efficiency of response (see Figure 6). Numerous informers credited their ability to access IPAC expertise as critical to being able to respond to COVID-19 and expressed concern that CFHS's capacity is only "one deep" given the importance of IPAC in delivering safe healthcare every day and not just in the setting of a pandemic. On the other hand, the CDO's Interim Clinical Directive was developed, evolved, and was implemented across Dental clinics to enable a safe clinical operating environment, while accounting for local conditions. These directives facilitated both patient and occupational safety.

Figure 6 Example of implemented IPAC measures in CFB clinics

Caption

The collage presents infection control measures in CFB clinics, including distancing markers, entrance screening, mandatory masks, sanitization stations, and directional signage, which are crucial for maintaining a safe environment and preventing the spread of infections.

Other - Dental clinics had some pre-existing capabilities and resources that contributed to a generally more efficient response than their medical counterparts. These consisted primarily of a database providing information about dental service operations, a high degree of pre-existing familiarity with use of PPE among their staff, and an operational level HQ that streamlined information flow and developed and promulgated common COVID-19 related Standard Operating Procedures for clinics via a pre-existing and well-established national SharePoint platform.

It was noted that medical and dental services worked in silos at tactical levels, with few structures and processes in place to facilitate sharing of information and coordination of effort. This was a barrier to potential efficiencies – such as leveraging dental personnel's familiarity with PPE to assist in training medical staff.

Recommendation #9: CFHS should establish and implement a formal and adequately resourced IPAC program.

Finding: CFHS overcame insufficient pre-existing inventory, an inefficient inventory management system and global supply chain disruptions and was able to sustain the supply of necessary medical PPE reasonably well to effectively meet COVID-19 response requirements.

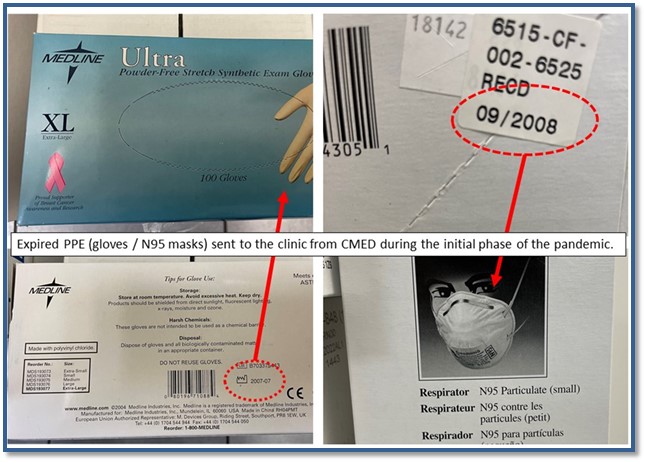

Centralized pandemic stockpiles of PPE were not at target levels in amount or quality prior to the pandemic. Unavailability / unpredictability of funds prior to the start of the pandemic precluded having "hard" contracts in place to keep the stockpile up to date as well as continue the supply through the pandemic. Holdings at the Central Medical Equipment Depot (CMED) included expired products as there was insufficient up to date stock to replace it (see Figure 7). Best possible use of the PPE stockpile was, however, achieved through certifying expired stock for safe use, careful monitoring of PPE holdings and 'burn rates', having clinics take advantage of local supply arrangements, and reserving central stock for augmentation of clinic supplies only as required.

Figure 7

Caption

The photo collage illustrates expired PPE, including masks and gloves, issued to CFB clinics by the Central Medical Equipment Depot due to pandemic shortages and stockpile limitations. It highlights the challenges faced by CFB clinics in maintaining adequate supplies of PPE, including expired masks and gloves distributed to clinics, shortages that led to the use of expired PPE, and stockpile limitations necessitating the distribution of expired PPE during the pandemic.

Some quality issues were due to disconnects between points of responsibility within CFHS for setting clinical standards for PPE and for its procurement.

At the tactical level, PPE supply was one of several factors limiting healthcare provision early in the pandemic. Perceptions of PPE sufficiency were varied: some medical clinics reported early shortages, while dental commentary from the same locations tended to be that supply was adequate but that this was due to judicious PPE management more than generous amounts of stock or a low burn rate. Overall, whether PPE supply was deemed adequate or not correlated with a clinic's ability to adapt services to decrease demand, leverage local supply arrangements, and/or access IPAC expertise to make optimal use of the stock that they did have and minimize wastage. Overall, there was no evidence of negative outcomes pertaining to the health or safety of CAF members or CFHS personnel due to lack of medical PPE, although worries about PPE adequacy, parameters for safe use, and availability were a stressor and contributor (in some cases) to mental health issues.

Pre-existing supply arrangements proved ineffective for procuring PPE on a large scale due to global supply chain disruption. The efficiency of the PPE supply chain was further decreased by an initial lack of coordination amongst federal organizations competing independently for limited contracts. This was resolved, but some contracts did not deliver PPE that met the expected level of quality. There also appeared to be a lack of coordination between medical and dental clinic supply chains, which may have lessened opportunities to optimize supply management.

Inconsistent N95 fit testing status of CFHS personnel and the stockpiling of different brands of masks with different fit profiles also detracted from the efficient supply of N95 masks to personnel. Another factor impeding efficiency of the response was the use of outmoded inventory management software that was not accessible at the tactical level, requiring ad hoc reports of PPE use in clinics to be generated at each clinic, transmitted, collated centrally and then reconciled with the centralized system.

Recommendation #10: CFHS should continue efforts to update its approach to the establishment, lifecycling, and management of PPE stockpiles.

3.1.3 Governance: To what extent was an effective governance framework well incorporated into the CFHS COVID-19 response portfolios?

Finding: Clinical governance within the CAF and CFHS was strengthened through the CAF's need to respond effectively to COVID-19.

The necessity of a whole of Defence Team response to COVID-19 as a health emergency solidified the role of the Surgeon General as the CAF's advisor on health. The Surgeon General was afforded increased direct access to high level CAF decision makers and was able to provide timely and relevant advice (supported by CFHS SMEs providing relevant decision support products such as epidemiology data and Fusion Centre reports). Similarly, the Director of Health Services Operations (DHSO) became more closely integrated into the Senior Joint Staff (SJS) to provide timely and unfiltered medical advice to strategic level decision-makers.

The approach taken by DFHP to provide verbal information to all operational, regional, and tactical clinical authorities concurrently on a frequent and regular basis, supplemented by published guidance as it became available, was effective and efficient. Most medical leadership teams indicated these regular teleconferences were one of their most important sources of HQ guidance.

On the other hand, Dental provided/received their own briefings (which included fusion slides) at the regional and tactical levels. This was supplemented by the RCDC COVID-19 Monitoring tool and CDO's Interim Clinical Directives.

Base/Wing Surgeons (B/WSurgs) played a critical role in integrating information from CFHS headquarters Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and various civilian national, provincial and local public health and health regulatory organizations. While this process lacked the efficiency of the more standardized approach taken across dental clinics, it allowed more responsiveness to different local levels of COVID-19 risk.

Of the clinics sampled, a correlation was seen between an efficient and effective response and a strong integration of the local command/management and clinical governance functions (i.e. a high functioning B/WSurg and CO team in a medical clinic, or the combination Dental Detachment Commander role in a dental clinic), supported by pre-existing and well defined structures and processes for collaboration between service areas (e.g., primary care and mental health/psychosocial services). Clinics where one or the other of these two factors was less well established had more difficulty navigating the challenges of the pandemic.

Clinical governance of HSS on deployed operations worked well for the majority of missions sampled. Effectiveness and efficiency of the response was facilitated by a clear and straightforward clinical governance framework outlined through Op Orders and Med Plans, even if the mission pre-dated the pandemic's onset. The Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC) Surgeon and supporting health services planners were seen as effective in supporting CFHS's response to COVID-19 in deployed settings.

Finding: A strong operational level HQ overseeing a single line of effort across all tactical locations was a factor that contributed to consistency, synchronization, and efficiency in responding to COVID-19.

Although official designated a unit, 1 Dental Unit functions as an operational level organization exercising both command and clinical authority over all CFHS in-garrison dental clinics. Its headquarters is structured and equipped to take strategic HQ guidance and transform it into implementable direction and support for its subordinate clinics. This arrangement significantly facilitated a dental services response to the pandemic that was consistent, synchronized, and efficient.

In contrast, operational level command and control of CFHS medical clinics is split between two regional Health Services Groups (HSGs), except for the Ottawa clinic which stands alone as a National Level Unit reporting directly to the strategic level (and later Division) headquarters. The HSGs are also charged with significant force generation responsibilities, overseeing the Regular and Reserve Force Field Ambulances in their regions. Further, the organization and establishment of the HSGs were initially provided limited resources for the operational level oversight of in-garrison care program delivery. HSG limitations included a de-linking between command and clinical authorities at that level, with SMAs distributed regionally as Regional Surgeons without a single "Group Surgeon" integrated directly into the HSG command suites.

Overall, the design (including capacity and capability) of the operational level governance structure impeded the efficiency, timeliness, and consistency of the response of in-garrison medical clinics to the pandemic, when compared to the single and much more in-garrison care focused 1 Dental Unit HQ, the design of which facilitated a more consistent and efficient approach across the dental clinics.

The introduction of the CFHS Division concept a few months into the pandemic clarified the distribution of responsibility between strategic and operational levels of CFHS. Further consolidation of this concept may mitigate the fragmentation of the medical clinic command and control, as well as facilitate collaboration across medical and dental lines of operation to realize system level efficiencies.

Recommendation #11: CFHS should continue to strengthen its operational level organizational structures and capacity and consider prioritizing the establishment of functional formations (HSGs) in lieu of existing regional formations as outlined in its existing plans for health system modernization.

3.2 Cluster II Logistics of the response

Description: For the purpose of this evaluation, the Logistics of the response can be categorised into three sectors: 1. Epidemiological surveillance of COVID-19 in CAF, provided by the Directorate of Force Health Protection; 2. Institutional Lessons Learned as outlined in the Defence Lessons Learned ProgramFootnote 12 and provided through a number of different functions within CFHS; and 3. Emergency Communications provided by CFHS Public Affairs and the Directorate of Health Services Operation via the Fusion Center. Each sector had its own process, purpose, and time-bound deliverables.

3.2.1 Effectiveness: Epidemiological surveillance

Finding: CFHS effectively produced the epidemiological information required by the CAF to inform its response to COVID-19.

Epidemiology reports started sluggishly evolving to provide valuable and up-to-date information for decision-makers and clinical advisors. In addition, the sections within DFHP collaborated to develop new policies, provide evidence-based guidance and advice, and liaise with civilian counterparts at the national, territorial, provincial, and regional levels. Ever-increasing demands for reporting (e.g., daily reports of cases, outbreak investigations, advisories and situation updates on particular outbreaks), at times, exceeded capacity. However, no discernable public health harm resulted as additional or more timely information would not likely have changed recommended management.

Several (N15) different epidemiology reports were reviewed. The contents of the documents were relevant and provided end-users with information assisting the chain of command and professional technical personnel in COVID-19 decision-making and the passage of correct information. The array of documents in the cross-sectional sample contained surveillance reports, case counts, outbreak summaries, critical advisories, background information, and SARS-CoV-2 spread population modelling.

3.2.2 Effectiveness: Lessons Learned

Note: Lessons learned" (LL) terminology was used extensively by interviewees, found in many key documents reviewed, and referenced or described in published works. However, the term or definition was poorly understood and often used interchangeably to describe other constructs related to organizational learning. Such imprecise and inconsistent use of the term does not reliably convey whether the lesson was observed, transmitted, recorded, shared, or implemented. Instead, the term "lessons learned" is often used to explain the positive and negative outcomes of the organizational response to an incident and does not fulfill the expectations that a lesson was actually learned. For example, when Canada experienced an outbreak of Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), a series of recommendations described as lessons learned to mitigate the "traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workersFootnote 13" were not applied to COVID-19 stress-related challenges. In other words, they were not lessons learned, but rather, lessons observed or recommendations not actioned.

Finding: While activities were undertaken by CFHS to support organizational learning from the COVID-19 experience, a coherent, comprehensive, collaborative, and current lessons learned program tying these activities together and ensuring optimal effectiveness of the full LL function was lacking.

DOAD 8010-0, Lessons Learned (updated 22 July 2016), provided the most current published direction on Lessons Learned relevant to the Evaluation period. The DAOD, in conjunction with Canadian Forces Joint Publication (CFJP) A2, provides a well-defined and customizable framework supported by "how to" guidance on the proper application of the program's core principles. The evaluation team found, however, that although the Defence LL Program(DLLP) was technically implemented, CAF/DND did not have a coherent Joint LL function at the Level 0 (L0) to coordinate, standardise, and provide oversight and training for the L1 LL community [CJOC, CJAT and LL Branch Op LASER Initial Observations]. Due to its operational focus, the CJAT and the processes that support it are not designed to provide nuanced and contextual observations, best practices, and recommendations for most health services activities, including those of CJOC-generated areas of interest.

Despite the lack of a fully implemented DLLP, CFHS direction to conduct LL activities were inserted into official orders from the chain of command from the L0 level and down through cascading orders to the responsive directorates and clinics. Currently nascent and residing in D HS Q&P, the LL program had begun to develop a health services-grounded organizational learning framework serving operational, domestic and in-garrison health services-related activities. How the traditional military LL forms and processes would integrate into these broader organizational learning functions in place within D HS Q & P was still a work in progress.

As the pandemic progressed, health services personnel gathered information oft described as lessons learned, but were more properly categorized as lessons observed (after-action reports, reports and returns, and the result of SME (and sometimes not) opinion). Health services personnel reported receiving little guidance or training on correctly collecting field observations, let alone their subsequent incorporation into a structured lessons-learned framework. Perhaps the most published and scrutinized LL related documents generated by health services personnel were the raw observations from collective and individual experiences in the Long Term LTCFs. Meaningful direction, understanding and training on writing medical observations may have prevented the inclusion in the reports of content described as reflecting significant behavioural biases (such as mind-reading, emotionally charged hyperbole, reporting innuendo as fact) and unsubstantiated allegations lacking important evidenced-based data (e.g., stating that a resident had died of neglect, dehydration or malnutrition without a coroner's inquest or reportFootnote 14).

Notwithstanding the above, CFHS did undertake a number of activities under the auspices of other programs that contribute to organizational learning as conceptualized in DLLP doctrine. These included the reporting, analysis (e.g., the Rapid Assessment Protocole) and implementation of recommendations stemming from patient safety incidents related to COVID-19 adaptations, the application of Quality Improvement processes to the rapid roll-out of virtual care, and the active solicitation of observations related to mass vaccination administration which were fed directly into planning for Op VECTOR and captured in a published report. Finally, this Evaluation represents a robust and comprehensive approach to organizational learning from the COVID-19 experience.

Recommendation #12: CFHS should examine its current organizational learning structures and processes in relation to CAF LL program requirements, then develop and implement programming necessary to close any gaps identified. This should include an analysis of how the new DLLS tools can best be integrated into the overall organizational learning framework.

Recommendation #13: CFHS should consider articulating in health emergency CONPLANs the framework of lessons learned tools and approaches to be used to ensure short-, medium- and long-term organizational learning from emergencies is optimized.

3.2.3 Effectiveness: Communications

Description: Public Affairs (PA). As outlined in CONPLAN LASER, the CF PA plan for response to a PI was expected to be active internally and passive externally as coordinated by ADM (PA) with Public Safety/Public Health Agency (PHAC) of Canada in order to maintain consonance with the overall federal government's message. Regional Joint Task Force HQs were to prepare PA plans IA W guidance provided at Annex X of the SOODO. [para 3 – coordinating instructions CONPLAN LASER]

Finding: CFHS PA was effective in collecting, contributing, co-ordinating, verifying, and publishing information internally.

CONPLAN LASER directs Public Affairs to take internal active and external passive roles during pandemic influenza. Given the high profile and political sensitivity of OP LASER, media content approval authority for Op LASER-related events rested with the Deputy Minister of Defence while the CFHS public affairs office adopted a passive posture, ensuring that approved PA products were communicated through the most appropriate outlet (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, main media outlets, CAF App, and CAF webpages). In addition, the office appeared to be COVID-19 current - collaborating with the offices of the SG, DSG, DFHP, and DHSO to be pandemic prepared passively. This passive posture negated, for the most, the need for a complex PA strategic and framework.

Evidence of effective internal communication can be seen in the multiple and timely social media posts. CFHS PA had multiple collaborative relations with other departments and directorates, ensuring that published information was positive, informative, and accurate. There were no noted corrections required following publications. It was not entirely clear if some of the ideas were initiated by CFHS PA or if it was suggested to CFHS PA, or if they were made aware of items that would be good to pursue. No data submitted reflected any changes in posture brought on by the pandemic.

Multiple mechanisms and types of communication platforms such as the Defence COVID Management Committee for rapid flow of information, social media platforms to CAF, Townhall communication and feedback, and Surgeon General Messages, appeared to be effective. They appeared to catalyse high vaccination rates in CAF members. The high efficacy of the mRNA vaccines and the high vaccination rate contributed to reduced morbidity and mortality among CAF members and civilian personnel, impeded transmission of COVID-19 in CAF facilities and sustained operational readiness of the force.

Finally, it is noteworthy that knowledge gathering, analysis and sharing improved dramatically with forming of the Fusion Centre within D HSO. Fusion Centre products facilitated informed decision-making both internal to CFHS and within the larger CAF.

Finding: CFHS PA's limitation to a passive media role with little authority for engaging external media likely resulted in some missed opportunities to highlight CFHS contributions to mitigating the impact of COVID-19 in a timelier way.

Given the high profile and political sensitivity of OP LASER, media content approval authority for Op LASER-related events rested with the Deputy Minister of Defence. With high-level strategic staff applying significant control at the tactical level, the CJAT assessment of Op LASER noted that "media engagement and connection with the public was infrequent and out-of-date information was sometimes reported when communications were issued at the higher level." For example, Public Affairs took a passive approach to publicizing CAF assistance to LTCFs and may have missed opportunities to foster more positive relations with the civilian population.

3.2.4 Efficiency: Epidemiological Surveillance

Finding: The dynamic nature of the pandemic, combined with the constant demands from multiple sources for epidemiology expertise (i.e., reports, advice and information), resulted in excessive demands on components of DFHP.

Universally reported by key interviewees was the incessant demand for epidemiology products and information. The exigences were often repetitive and redundant, with requests for data coming from all directions. To the staff within CFHS responsible for generating epidemiological data and products, it seemed that demands were not mitigated or filtered by senior leadership.

The epidemiology section within D FHP entered the pandemic incompletely staffed and all core business within DFHP needed to be stopped to meet the pandemic-related demands. Personnel fatigue (described as bordering on burnout) and resultant increased attrition exacerbated the impact of the pre-pandemic human resource shortages. They perpetuated the challenge of responding to the constant calls for epidemiology products.

The ever-increasing demands for epidemiological products (e.g., daily reports and updates, sitreps, outbreak reports, advisories, etc.) stretched the capability of staff. However, due to limited staff (e.g. secondment, burn-out, vacancies), the demands were not always fulfilled. Still, there was no evidence of public health harm as unmet information requests would not likely have changed recommended management. From the site visits, it was evident that health authorities were proactive and creative in using epidemiological data to its fullest.

Recommendation #14: CFHS should continue to pursue modernizing its electronic health records system as a matter of priority, ensuring its functionality as an epidemiological database and its ability to capture GBA+ relevant data.

3.2.5 Efficiency: Lessons Leaned

Finding: The lack of a systematic analytical framework for the management of LL observations impeded the efficiency of the LL function within CFHS.

As described in section 3.2.2 above, the CFHS lacked an overarching framework for LL activities and had not implemented several essential elements including LL training. This likely had a negative impact on the speed and efficiency of organizational learning related to COVID-19.

3.2.6 Efficiency: Communications

Finding: Both the CFHS PA function and the Fusion Centre were found to be efficient in the performance of their mandates.

Despite the limited resources, time constraints, and direction to adopt a passive external communication posture, the CFHS PA cell was able to use efficiently established communication channels to inform CAF members, external partners and the general public. To this end, essential up-to-date and refined information were provided to inform decision-making and policy.

3.2.7 Governance: Epidemiological Surveillance

Finding: Communication between DFHP experts, the professional technical network, and the chain of command was clear and effective.

Directorate of Force Health Protection (DFHP) Advisories 6695-09 and 6636-80 represented key documents for senior medical authorities and CoC, particularly at the tactical (i.e., clinic) level. The advisories were referenced consistently in clinic BCPs / BRPs. In addition, weekly DFHP-sponsored prof-tech teleconferences and voluminous email exchanges from prof tech net authorities and CoC provided meaningful opportunities for further DFHP input while providing feedback from target audiences. Lastly, DFHP used positional mailboxes monitored daily; guidance and policy SARS-CoV-2-related documentation was posted on a DFHP SharePoint and in OneNote.

The immense dis-coordinated daily demand for epi products created undue pressure on those responsible for responding to these demands. A common theme among respondents was the frustration with these demands that seemly came from "all directions" with little filtering from DFHP CoC. However, despite the pressures, the content of the epidemiology products was, for the most part, scientifically accurate, clear, complete, and concise.

Recommendation #15: CFHS should re-evaluate its operational model for epidemiology services to ensure capacity is adequate and can be efficiently and effectively directed toward organizational priorities.

3.2.8 Governance: Lessons Learned

Finding: A foundation for effective governance of the LL process within CFHS is in place at the strategic level but is not yet mature.

CFHS had made strides in implementing an Integrated Governance Framework, including establishing Quality Council, the terms of reference for which contain responsibilities that contribute to the DLLP process. However, the different processes supporting the collection and analysis of data relevant to organization learning are not all consistently in place and producing findings and recommendations for QC review and referral for action. Further, structures and processes to integrate QC functions with similar functions to support governance of LL at the operational and tactical levels are not yet in place.

Specific to LL through the evaluation process, evaluation program ARAs are well integrated. All governing bodies such as Evaluation Steering Committee (ESC) and Quality Council (QC) are in place, operationalised and provide guidance for the D HS Q&P to perform its function under the Directorate's evaluation mandate. This clear governance structure will support the completion of mandated COVID-19 LL through the evaluative process.

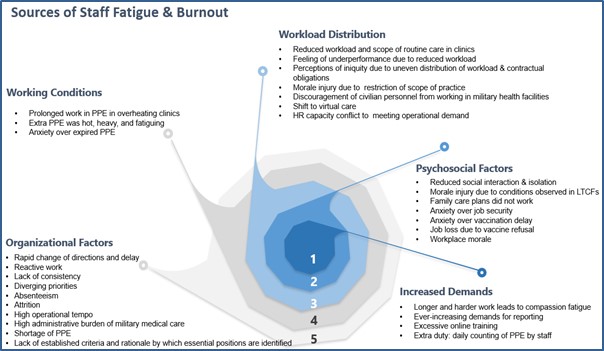

3.2.9 Governance: Communications