Chapter Two: The Canadian Military Justice System: Structure and Statistics

This chapter describes the structure of the Canadian military justice system and analyzes key statistical information in the administration of military justice over the course of the reporting period. 1

Canada’s Military Justice System

Canada’s military justice system is a separate and parallel system of justice that forms an integral part of the Canadian legal mosaic. It shares many of the same underlying principles with the civilian criminal justice system, and it is subject to the same constitutional framework including the Charter. On more than one occasion, the Supreme Court of Canada has directly addressed the importance of a separate, distinct military justice system to meet the specific needs of the CAF. 2

The military justice system differs from its civilian counterpart in respect of some of its objectives. In addition to ensuring that justice is administered fairly and with respect for the rule of law, the military justice system is also designed to promote the operational effectiveness of the CAF by contributing to the maintenance of discipline, efficiency, and morale. These objectives give rise to many of the substantive and procedural differences that properly distinguish the military justice system from the civilian justice system.

The ability of the CAF to operate effectively depends on the ability of its leadership to instill and maintain discipline. This particular need for discipline in the CAF is a key part of the raison d’être of the military justice system. Indeed, while training and leadership are central to the maintenance of discipline, the chain of command must also have a legal mechanism that it can employ to investigate and sanction disciplinary breaches that require a formal, fair, and prompt response. As the Supreme Court of Canada observed in R. v. Généreux, “breaches of military discipline must be dealt with speedily and, frequently, punished more severely than would be the case if a civilian engaged in such conduct. [...] There is thus a need for separate tribunals to enforce special disciplinary standards in the military.

” The military justice system is designed to meet those unique requirements articulated by Canada’s highest court and recently reiterated in R. v. Moriarity.

The Structure of the Military Justice System

The Code of Service Discipline

The Code of Service Discipline, Part III of the NDA, is the foundation of the Canadian military justice system. It sets out disciplinary jurisdiction and provides for service offences that are essential to the maintenance of discipline and the operational effectiveness of the CAF. It also sets out punishments and powers of arrest, along with the organization and procedures of service tribunals, appeals, and post-trial review.

The term "service offence" is defined in the NDA as “an offence under this Act, the Criminal Code, or any other Act of Parliament, committed by a person while subject to the Code of Service Discipline.

” Thus, service offences include many disciplinary offences that are unique to the profession of arms, such as disobedience of a lawful command, absence without leave, and conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline, in addition to more conventional offences that are created by the Criminal Code and other Acts of Parliament. The diverse scope of service offences that fall within the Code of Service Discipline permits the military justice system to foster discipline, efficiency and morale, while ensuring fair justice within the CAF.

Members of the Regular Force of the CAF are subject to the Code of Service Discipline everywhere and at all times, whereas members of the Reserve Force are subject to the Code of Service Discipline only in the circumstances specified in the NDA. Civilians may be subject to the Code of Service Discipline in limited circumstances, such as when accompanying a unit or other element of the CAF during an operation.

Investigations and Charge Laying Process

If there are reasons to believe that a service offence has been committed, then an investigation is conducted to determine whether there may be sufficient grounds to lay a charge. If the complaint is of a serious or sensitive nature, then the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service will examine the complaint and investigate as appropriate. Otherwise, investigations are conducted either by Military Police or, where the matter is minor in nature, at the unit level.

The authorities and powers vested in Military Police members, such as those of a peace officer, are conferred by the NDA, the Criminal Code and the QR&O. Amongst other duties, Military Police members conduct investigations and report on service offences that were committed, or alleged to have been committed by persons subject to the Code of Service Discipline. Military Police members are professionally independent in carrying out policing duties and, as such, are not influenced by the chain of command in order to preserve and ensure the integrity of all investigations.

If a charge is to be laid, then an officer or noncommissioned member having authority to lay a charge is required to obtain legal advice before laying a charge in those circumstances set out in article 107.03 of the QR&O. Those circumstances where pre-charge legal advice is required are where an offence that is not authorized to be tried by summary trial, is alleged to have been committed by an officer or a non-commissioned member above the rank of sergeant or, if a charge were laid, it would give rise to a right to elect to be tried by court martial. The legal advice must address the sufficiency of the evidence, whether or not in the circumstances a charge should be laid and, where a charge should be laid, the appropriate charge.

The Two Tiers of the Military Justice System

The military justice system has a tiered tribunal structure comprised of two types of service tribunals: summary trials and courts martial. The QR&O outline procedures for the disposal of a charge by each type of service tribunal.

Summary Trials

The summary trial is the most common form of service tribunal. It allows for less serious service offences to be tried and disposed of quickly at the unit level. Summary trials are presided over by members of the chain of command, who are trained and certified by the JAG as qualified to perform their duties as presiding officers in the administration of the Code of Service Discipline. All accused members are entitled to an assisting officer who is appointed under the authority of a commanding officer to assist the accused in the preparation of his or her case and during the summary trial.

After a charge is laid by an authorized charge layer, if it is determined that the accused can be tried by summary trial then, except in certain circumstances, an accused person has a right to be offered an election to be tried by court martial. 3 The election process was designed to provide the accused with the opportunity to make an informed choice regarding the type of trial to be held, bearing in mind that an accused who elects not to be tried by court martial is, in effect, waiving the right to be tried by that form of trial with full knowledge of the implications.

There are many differences between summary trials and courts martial. Courts martial are more formal and provide the accused more procedural safeguards than those available at summary trial, such as the right to be represented by legal counsel. The election process was designed to provide the accused with a reasonable opportunity to be informed about both types of tribunals in order to decide whether to exercise the right to be tried by court martial and to communicate and record their choice.

The jurisdiction of a summary trial is limited by factors such as the rank of the accused, the type of offence the accused is charged with and whether the accused has elected to be tried by court martial. In those cases that cannot be dealt with by summary trial, the matter is referred to the DMP, who determines whether the matter will be disposed of by court martial.

The disposition of charges by summary trial is meant to occur expeditiously. Accordingly, other than for two civil offences for which the limitation period is six-months 4, a presiding officer may not try an accused person by summary trial unless the trial commences within one year after the day on which the service offence is alleged to have been committed.

The procedures at summary trial are straightforward and the powers of punishment are limited. This limitation reflects both the less serious nature of the offences involved, and the intent that the punishments be primarily corrective in nature.

Review of a Finding Made and/or Sentence Imposed at Summary Trial

All offenders convicted at summary trial have the right to apply to a review authority for a review of the findings, the punishment imposed, or both. The findings and/or punishment imposed at summary trial may also be reviewed on the independent initiative of a review authority. A review authority is a more senior officer in the chain of command of the officer who presided over the summary trial, as designated by the QR&O. A review authority may quash any findings made at summary trial, substitute any finding or punishment or may mitigate, commute or remit any punishment awarded at summary trial. Before making any determination, a review authority must obtain legal advice.

Courts Martial

The court martial – a formal military court presided over by a military judge – is designed to deal with more serious offences. Courts martial are conducted in accordance with rules and procedures similar to those of civilian criminal courts and have the same rights, powers and privileges as a superior court of criminal jurisdiction with respect to all “matters necessary or proper for the due exercise of [their] jurisdiction.

” 5

The NDA provides for two types of court martial: General and Standing. These courts martial can be convened anywhere, in Canada and abroad. The General Court Martial is composed of a military judge and a panel of five CAF members. The panel is selected randomly by the Court Martial Administrator and is governed by rules that reinforce its military character. At a General Court Martial, the panel serves as the trier of fact while the military judge makes all legal rulings and imposes the sentence. Panels must reach unanimous decisions on any finding of guilt. At a Standing Court Martial, the military judge sits alone, makes any of the required findings and, if the accused person is convicted, imposes the sentence.

At a court martial, the prosecution is conducted by a military prosecutor under the authority of the DMP. The accused is entitled to be represented by defence counsel from the Directorate of Defence Counsel Services at no cost, or by civilian counsel at his or her own expense. The accused can also choose not to be represented by a lawyer.

Appeal of a Court Martial Decision

Decisions made at courts martial may be appealed by the person subject to the Code of Service Discipline or by the Minister or counsel instructed by the Minister to the Court Martial Appeal Court. 6 The Court Martial Appeal Court is composed of civilian judges who are designated from the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal, or appointed from the Superior Courts and Courts of Appeal of the provinces and territories.

Court Martial Appeal Court decisions may be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada on any question of law on which a judge of the Court Martial Appeal Court dissents, or on any question of law if leave to appeal is granted by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Statistics 7

Summary Trials

Number of Summary Trials

Summary trials continue to be the most widely used form of service tribunal in the CAF to deal with service offences under the Code of Service Discipline. During this reporting period there were 553 summary trials in comparison to 56 courts martial. The overall percentage of all cases disposed of at summary trial this reporting period was approximately 91 percent. Figure 2-1 shows the number of summary trials and courts martial for the last two reporting periods as well as the corresponding percentage of cases tried by each type of service tribunal and Figure 2-2 shows the total number of summary trials by reporting period since 2012/13.

Figure 2-1: Distribution of Service Tribunals

| 2015-2016* | 2016-2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Number of courts martial | 47 | 5.93 | 56 | 9.20 |

| Number of summary trials | 745 | 94.07 | 553 | 90.80 |

| Total | 792 | 100 | 609 | 100 |

* All summary trial statistics from the 2015/16 reporting period and which are reported in this report may differ from those statistics reported in the 2015/16 Annual Report of the Judge Advocate General as a result of late reporting by various units across the CAF.

Figure 2-2: Number of Summary Trials

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Summary Trials | 1248 | 1162 | 857 | 745 | 553 |

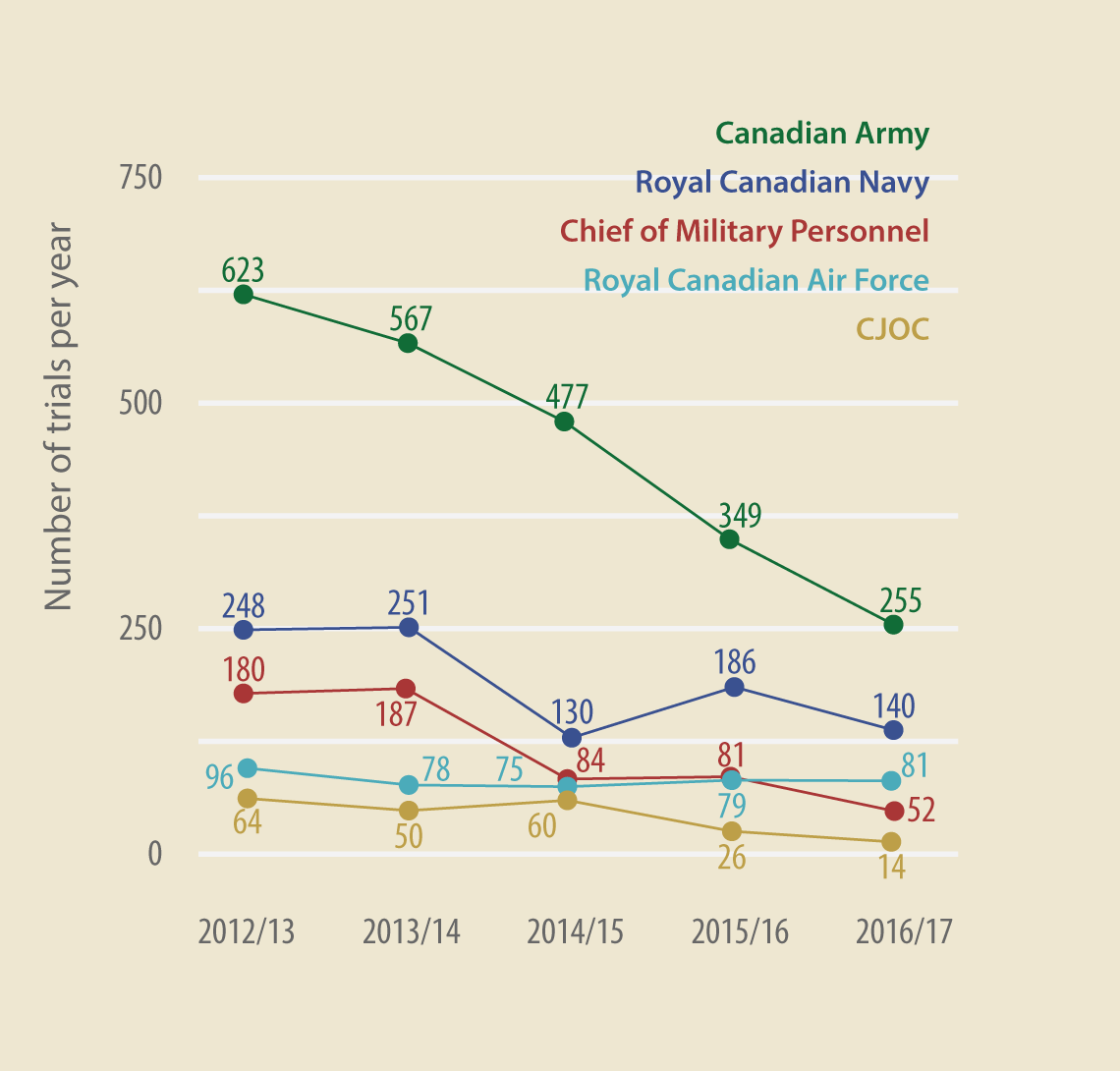

Figure 2-3 shows the total number of summary trials for all commands for the last two reporting periods and Figure 2-4 illustrates the number of summary trials specifically for the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Chief of Military Personnel, the Canadian Joint Operations Command and the Royal Canadian Air Force from 2012/13.

Figure 2-3: Number of Summary Trials by Command

| Commands | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Canadian Army | 349 | 46.85 | 255 | 46.11 |

| Royal Canadian Navy | 186 | 24.97 | 140 | 25.32 |

| Chief of Military Personnel | 81 | 10.87 | 52 | 9.40 |

| Royal Canadian Air Force | 79 | 10.60 | 81 | 14.65 |

| Canada Joint Operations Command | 26 | 3.49 | 14 | 2.53 |

| Canada Special Operations Forces Command | 7 | 0.94 | 4 | 0.72 |

| Vice Chief of the Defence Staff | 6 | 0.81 | 4 | 0.72 |

| Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management) | 6 | 0.81 | 1 | 0.18 |

| Canadian Forces Intelligence Command (CFINTCOM/CDI) | 2 | 0.27 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Assistant Deputy Minister (Material) | 1 | 0.13 | 2 | 0.37 |

| Assistant Deputy Minister (Public Affairs) | 1 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Assistant Deputy Minister (Infrastructure and Environment) | 1 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 745 | 100 | 553 | 100 |

Figure 2-4: Number of Summary Trials for the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Chief of Military Personnel, the Canadian Joint Operations Command and the Royal Canadian Air Force.

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canaidan Army | 623 | 567 | 477 | 349 | 255 |

| Royal Canadian Navy | 248 | 251 | 130 | 186 | 140 |

| Chief of Military Personnel | 180 | 187 | 84 | 81 | 52 |

| Royal Canadian Air Force | 96 | 78 | 75 | 79 | 81 |

| CJOC | 64 | 50 | 60 | 26 | 14 |

For the Canadian Army, in this reporting period there were a total of 255 summary trials as opposed to 349 for the previous reporting period. That is a decrease of 94 summary trials which represents a decrease of approximately 27 percent in comparison to the previous reporting period.

When these numbers are examined at the unit level, it can be seen that there are fewer summary trials at various army training centers. For example, the number of summary trials at the Artillery School, located at Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, has decreased over the past four reporting periods going from 20 summary trials in the 2013/14 reporting period to only four in the current reporting period. Similarly, the Infantry School, also located at Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown has had a decrease from 35 summary trials in the 2013/14 reporting period to three in the 2016/2017 reporting period. A significant portion of this decrease can be attributed to a reduction in the number of charges for unauthorized discharges pursuant to s.129 of the NDA. 8 In the 2012/13 reporting period there were 26 such charges tried at the Infantry School. In the current reporting period there were no charges for unauthorized discharges.

Several other units within the Canadian Army have also had decreases in the number of summary trials over the past several reporting periods. For example, the Royal Canadian Dragoons located at Garrison Petawawa reported four summary trials in the current reporting period compared to 16 in the 2015/16 reporting period. Similarly, the 4 Engineer Support Regiment, located at Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, reported three summary trials this reporting period compared to 13 for the previous reporting period.

The decrease in the total number of summary trials for the Royal Canadian Navy and the Chief of Military Personnel has been less prominent. For the Royal Canadian Navy, the total number of summary trials has fluctuated over the past ten reporting periods.

For the Chief of Military Personnel there is also a decrease in the total number of summary trials over the past several reporting periods. In the 2008/09 reporting period, the Chief of Military Personnel reported a high of 492 summary trials and that number has declined over the past nine years to the current reporting period when the Chief of Military Personnel reported only 52 summary trials.

Finally, for Canadian Joint Operations Command a decrease in the total number of summary trials is apparent from the 2010/11 reporting period through to the 2012/13 reporting period where the number of summary trials went from 247 to 64. This decrease coincides with the close out of the CAF mission in Afghanistan.

Number of Charges Disposed by Summary Trial

In this reporting period, there were a total of 817 charges disposed of at summary trial compared to 1118 charges disposed of at summary trial during the 2015/16 reporting period. Figure 2-5 shows the total number of charges disposed of at summary trial since 2012/13.

The two most common types of offences which account for approximately 65 percent of all charges in the summary trial system are absence without leave and conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline.9

In the current reporting period the total number of charges reported for absence without leave is 395. This is a decrease when compared to previous reporting periods where there was a high of 788 charges for absence without leave in the 2007/08 reporting period.

For the offence of conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline, this reporting period there were a total of 124 charges. This is a decrease compared to previous reporting periods where there was a high of 1403 charges for conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline in the 2007/08 reporting period. Figure 2-6 shows the number of charges for absence without leave and conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline from 2012/13.

Figure 2-5: Number of Charges Disposed of at Summary Trial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Charges Disposed of at Summary Trial |

1734 | 1806 | 1225 | 1118 | 817 |

Figure 2-6: Number of charges for Absence without Leave and Conduct or Neglect to the Prejudice of Good Order or Discipline

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prejudice to Good Order and Discipline | 700 | 711 | 404 | 312 | 124 |

| Absence without Leave | 607 | 667 | 475 | 464 | 395 |

When examining the various sub-categories for charges of conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline a decrease can be seen for alcohol and drug offences as well as inappropriate relationships. Additionally, over the past several reporting periods there has also been a decrease in the number of charges for unauthorized discharges pursuant to section 129 of the NDA. The number of charges for unauthorized discharges decreased from 213 in the 2013/14 reporting period to 107 in the following reporting period and those numbers continue to decline as in the current reporting period there were only seven charges for unauthorized discharges throughout the entire CAF.

These decreases in the number of summary trials as well as the number of charges disposed of at summary trial are of concern. Therefore, the Office of the JAG continues to investigate this decrease in the total number of summary trials as well as the number of charges disposed of by summary trial in order to determine the cause and whether any action may be appropriate moving forward.

In this regard, in last year’s report, the JAG announced the creation of a team to develop a process for conducting military justice audits to assist in this analysis. As explained in further detail in Chapter Three, the initial step to conducting such audits has been to work towards the creation of a military justice case management tool and database which will facilitate the collection of objective and measurable data at the unit level. Once complete, this case management tool and database will provide the Office of the JAG with key objective and measurable data that will aid in the audit of all CAF units. Moreover, this case management tool and database will provide timely information that will better enhance the JAG’s ability to conduct detailed analysis into military justice statistics.

In addition, as will also be discussed in Chapter Three, during the previous reporting period the JAG coordinated the establishment of two working groups comprised of commanding officers and senior non-commissioned members to develop and consider options for the renewal of the summary trial system. The purpose of these working groups was to provide a command perspective on the administration of military justice at the unit level to ensure that the summary trial system remains responsive to the disciplinary needs of the CAF. The feedback from the working groups will provide useful insight moving forward by assessing the effectiveness of the current summary trial system and also for ensuring that the military justice system remains a viable tool for commanders in the maintenance of discipline, efficiency and morale within their units.

Number of Elections to be Tried by Court Martial

Pursuant to QR&O article 108.17, an accused person has the right to elect to be tried by court martial rather than summary trial except where the accused: (1) has been charged with one of five minor service offences; and (2) the circumstances surrounding the commission of the offence are sufficiently minor in nature that the officer exercising summary trial jurisdiction over the accused concludes that a punishment of detention, reduction in rank or a fine in excess of 25 percent of the accused’s monthly basic pay would not be warranted if the accused were found guilty of the offence.

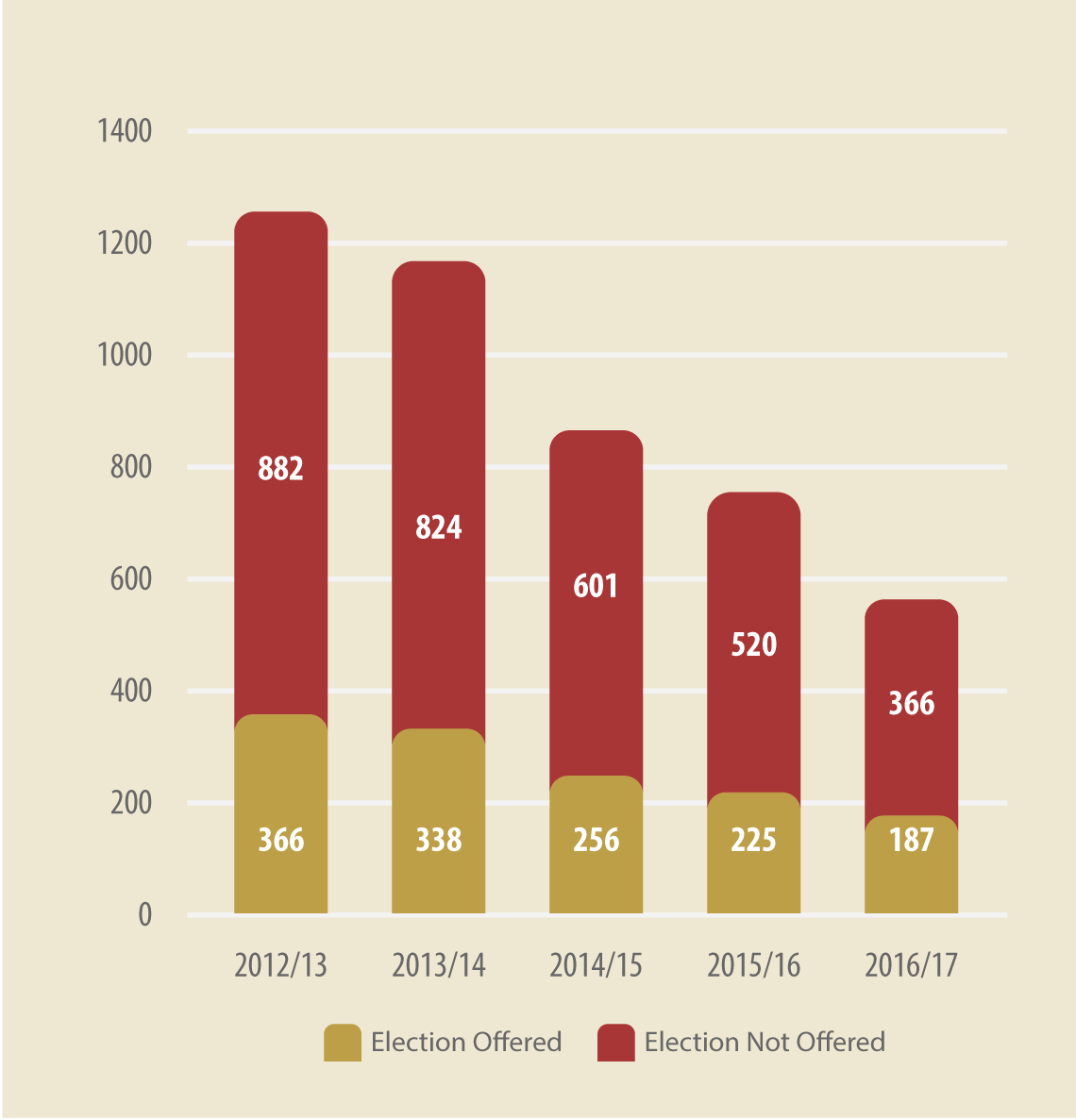

The five minor offences are: (1) insubordinate behaviour, (2) quarrelling, (3) absence without leave, (4) drunkenness, and (5) conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline where the offence relates to military training, maintenance of personal equipment, quarters or work space, or dress and deportment.10 Figure 2-7 shows the number of summary trials for the past five reporting periods in which the accused person was offered an election as well as the number of cases in which no election was offered. Figure 2-8 shows the percentage of cases where an accused was offered an election.

Figure 2-7: Number of Cases where Election Offered and Not Offered

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election Offered | 366 | 338 | 256 | 225 | 187 |

| Election Not Offered | 882 | 824 | 601 | 520 | 366 |

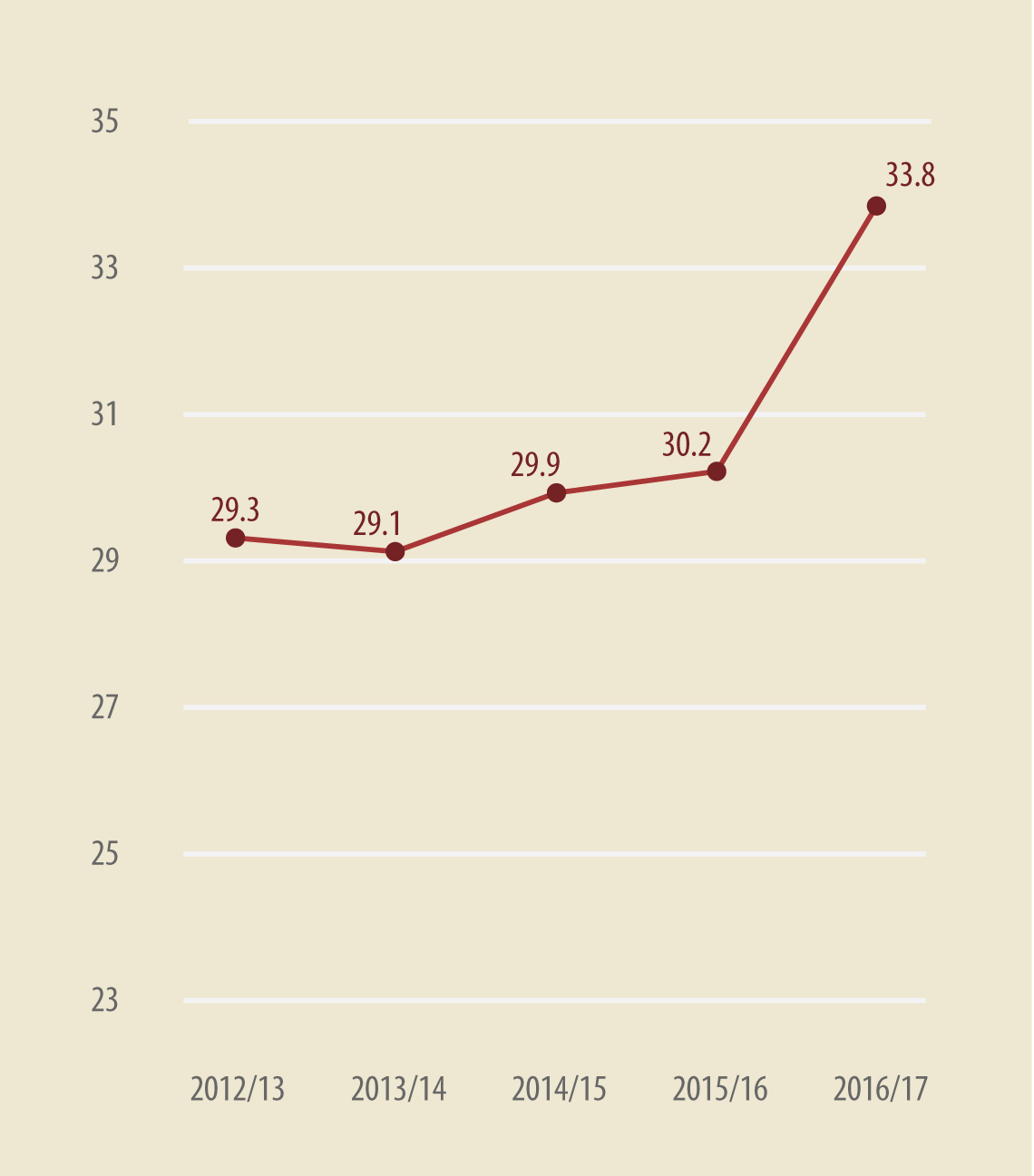

Figure 2-8: Percentage of Accused Offered an Election

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Accused Offered an Election | 29.3 | 29.1 | 29.9 | 30.2 | 33.8 |

During this reporting period, accused members elected to be tried by summary trial 141 times out of the 187 cases in which an election was offered, representing approximately 75 percent of accused members offered an election. That amounts to 46 members electing trial by court martial in the current reporting period.

There has been an increase in the percentage of accused members electing to be tried by court martial when an election is offered over the past several reporting periods. Figure 2-9 shows the percentage of accused persons electing court martial when an election was offered by reporting period since 2012/13.

Figure 2-9: Percentage of Accused Electing Court Martial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Accused Electing Court Martial | 9.63 | 16.34 | 21.48 | 23.47 | 24.6 |

Findings by Charge at Summary Trial

The percentages of all findings by charge has remained relatively constant on a year by year basis. For example, the percentage of guilty findings has remained relatively constant at approximately 87 percent compared to the previous reporting period. Similarly, the percentage of not guilty findings has remained relatively constant at approximately nine percent. A complete breakdown of the total number of findings by charge and the corresponding percentage for the last two reporting periods can be found at Figure 2-10.

Figure 2-10: Findings by Charge

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Guilty | 976 | 87.30 | 707 | 86.54 |

| Guilty – Special Finding | 6 | 0.54 | 8 | 0.98 |

| Not guilty | 96 | 8.59 | 80 | 9.79 |

| Charge stayed | 34 | 3.04 | 20 | 2.4 |

| Charge not proceeded with | 6 | 0.54 | 2 | 0.24 |

| Total | 1118 | 100 | 817 | 100 |

Punishments at Summary Trial

This reporting period there were a total of 723 punishments awarded at summary trial.11 Compared to the previous reporting period, there has been a decrease of 276 punishments as there were 999 punishments awarded in the previous reporting period.

Of those possible punishments which can be awarded at summary trial, fines and confinement to ship or barracks continue to be the most used punishments. Figure 2-11 shows the total number of punishments for the last two reporting periods as well as the corresponding percentage of each punishment over that same period.

Figure 2-11: Punishments at Summary Trial

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Detention | 24 | 2.40 | 9 | 1.24 |

| Reduction in rank | 7 | 0.70 | 6 | 0.83 |

| Severe reprimand | 6 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.14 |

| Reprimand | 51 | 5.11 | 36 | 4.98 |

| Fine | 548 | 54.85 | 401 | 55.46 |

| Confinement to ship or barracks | 258 | 25.83 | 192 | 26.56 |

| Extra work and drill | 69 | 6.91 | 47 | 6.5 |

| Stoppage of leave | 17 | 1.70 | 13 | 1.80 |

| Caution | 19 | 1.90 | 18 | 2.49 |

| Total | 999 | 100 | 723 | 100 |

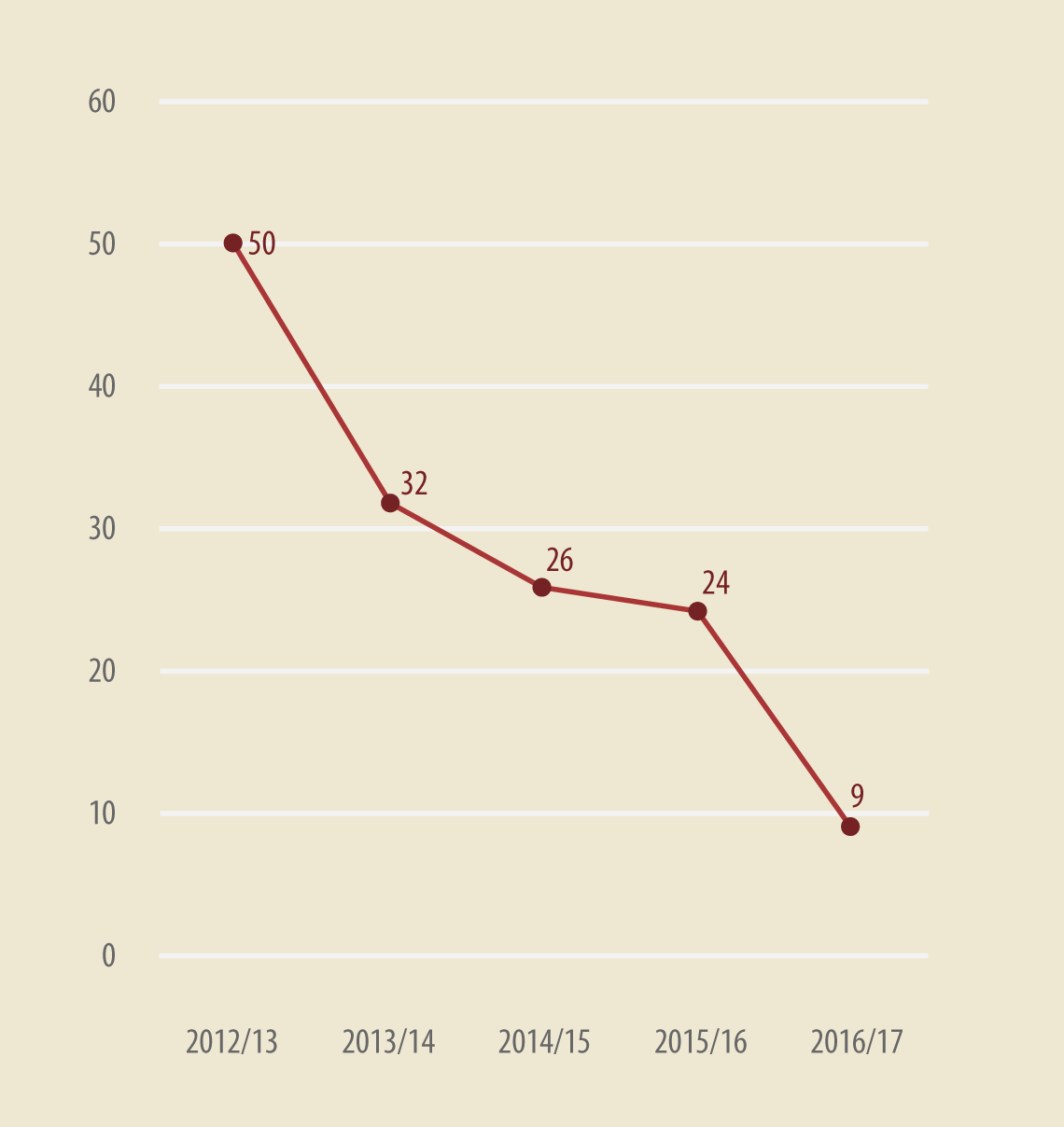

In this reporting period the punishment of detention was awarded nine times when compared to the 2012/13 reporting period where the punishment of detention was awarded 50 times. An overview of the number of times the punishment of detention was awarded over the past five years can be found in Figure 2-12.

Figure 2-12: Total Punishments of Detention

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Punishments of Detention | 50 | 32 | 26 | 24 | 9 |

Summary Trial Reviews

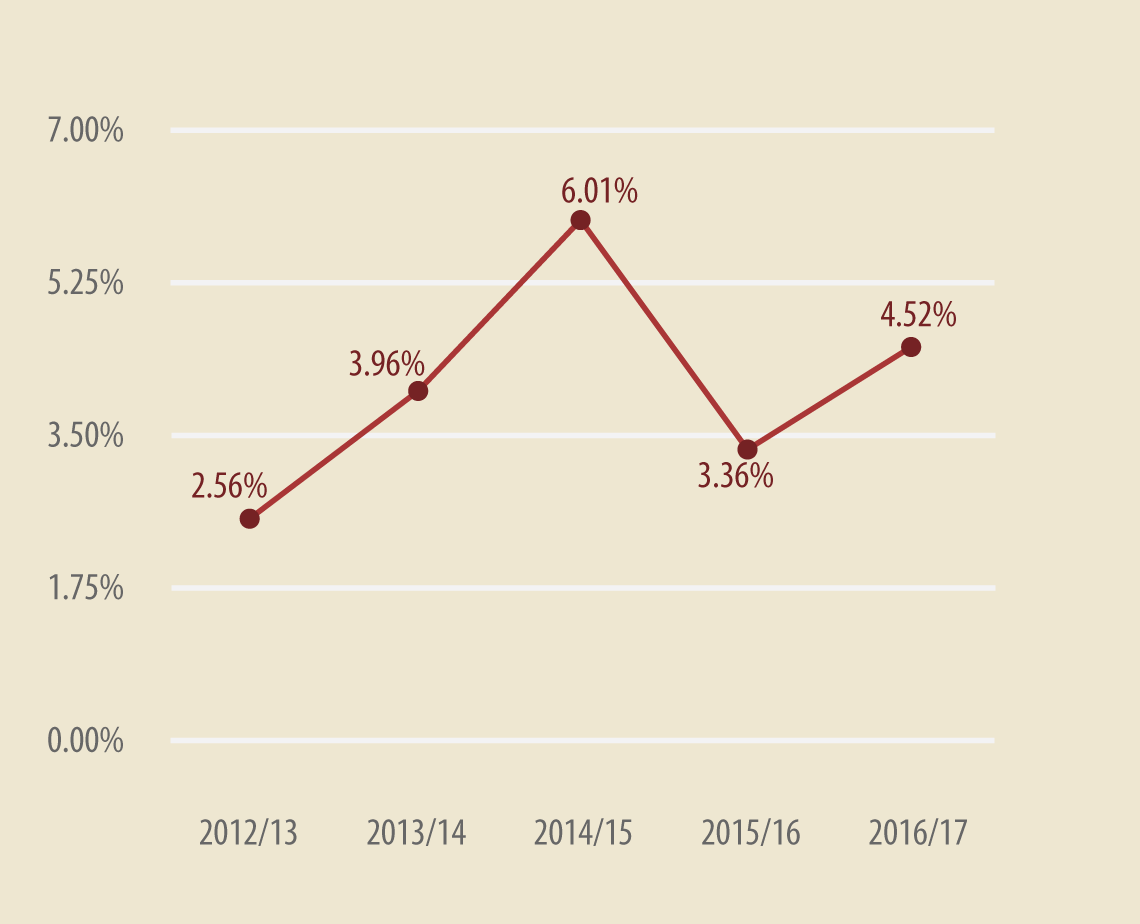

In the current reporting period, a total of 25 summary trials were reviewed based on requests by members found guilty at summary trial or on a review authority’s own initiative. Of those reviews, 12 were based on finding, nine on sentence, and four were based on both finding and sentence. As there was a total of 553 summary trials, the percentage of cases that were subject to a review was approximately 4.52 percent. This percentage is consistent with that of the previous reporting period when approximately 3.36 percent of cases were reviewed. Figure 2-13 shows the percentage of cases reviewed since 2012/13.

Figure 2-13: Percentage of Summary Trials Reviewed

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Summary Trials Reviewed | 2.56 | 3.96 | 6.01 | 3.36 | 4.52 |

Based on the nature of the request for review, a review authority has several options available to him or her to deal with the matter including upholding the decision of the presiding officer, quashing the finding, and substituting the finding or punishment. In approximately 38 percent of all decisions a review authority quashed the decision of the presiding officer. In approximately another 38 percent of all decisions a review authority upheld the decision of the presiding officer. In the previous reporting period approximately 42 percent of decisions by the review authority were to uphold the findings. A complete breakdown of all decisions of a review authority and the corresponding percentage of each decision for the past two reporting periods can be found at Figure 2-14.

Figure 2-14: Decisions of Review Authority

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Upholds decision | 13 | 41.94 | 10 | 38.46 |

| Quashes findings | 7 | 22.58 | 10 | 38.46 |

| Substitutes findings | 4 | 12.90 | 2 | 7.69 |

| Substitutes punishment | 3 | 9.8 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Mitigates / commutes / remits punishment | 4 | 12.90 | 4 | 15.39 |

| Total | 31* | 100 | 26** | 100 |

* In the 2015/16 reporting period there were 29 requests for review and 31 review decisions as review authorities may take multiple decisions in each case depending on the request for review. In one case the review authority upheld the finding one charge, substituted a finding on a second charge and mitigated the punishment awarded at summary trial. In another review, the review authority upheld the finding on one charge and also mitigated the sentence.

** In one case the review authority took two separate decisions in one request for review. The review authority reviewed requests to both the finding and punishment at the request of an accused.

Inappropriate Sexual Behaviour

Prior to the 2015/16 reporting period charges for inappropriate sexual behaviour were not subject to a separate reporting and analysis due to the nature by which these charges were captured by the summary trial database. However, improvements to the summary trial database now allow better tracking and reporting of such offences. Those charges for inappropriate sexual behaviour tried at the summary trial level are sexual harassment and inappropriate personal relationships.12 In both cases, these offences are charged pursuant to s.129 of the NDA.

In the current reporting period there were a total of 23 charges for sexual harassment and two charges of inappropriate relationships tried by summary trial.13 There were 21 charges for sexual harassment in the previous reporting period. For those 23 charges of sexual harassment pursuant to s.129 of the NDA for the current reporting period, there were three charges for inappropriate touching, four charges for inappropriate acts or gestures, 13 charges for inappropriate sexual comments or jokes and three charges related to intimate images.14

The number of charges for inappropriate relationships has decreased. In the previous reporting period there were 15 charges pursuant to s.129 for inappropriate relationships as compared to two for the current reporting period.

Although there were a total of 25 charges for inappropriate sexual behaviour there were only eight separate accused members. The majority of members were non-commissioned members ranging in rank from private to warrant officer with only two commissioned officers at the rank of captain tried for such offences. Of those 23 charges for sexual harassment, there were 19 guilty findings, two not guilty findings and two charges were stayed by the presiding officer. Both charges for inappropriate relationships resulted in a guilty finding.

In terms of sentence, for those summary trials for sexual harassment there were a total of ten fines ranging in amounts from $200 to $2500, two punishments of confinement to barracks for a period of seven days, two reprimands, one sentence of detention for a period of six days, one caution, and one reduction in rank. For those summary trials for inappropriate personal relationships, the two accused were sentenced to a fine in the amounts of $600 and $1000.15

Language of Summary Trials

As an accused may choose to have his or her summary trial conducted in either official language, the presiding officer must be able to understand the language in which the proceedings are to be conducted without the assistance of an interpreter. Where the presiding officer lacks the required language ability, he or she should refer the case to another presiding officer to try the case.

This reporting period, approximately 87 percent of summary trials were conducted in English and 13 percent were conducted in French. These percentages are consistent when compared to previous reporting periods. Figure 2-15 shows the number of summary trials conducted in both English and French for the past two reporting periods.

Figure 2-15: Language of Summary Trials

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| English | 667 | 89.53 | 479 | 86.62 |

| French | 78 | 10.47 | 74 | 13.38 |

| Total | 745 | 100 | 553 | 100 |

In this reporting period, there were three cases where there was a discrepancy between the language of the particulars of the charge on the Record of Disciplinary Proceedings and the choice of language for the proceedings selected by the accused. In two of these cases the accused was offered to have the charges re-drafted in his or her language of choice but the accused declined, as in both cases the accused were bilingual and had the ability to understand the charges against them. However, the summary trial in both instances proceeded in the language selected by the accused.

In the one remaining case, the particulars of the charges were not drafted in the choice of language of the accused. However, the summary trial was conducted in the language as chosen by the accused. A review was conducted by the chain of command and it was determined that the accused did not suffer any prejudice as a result.

Timelines for Summary Trials

The purpose of the summary trial system is to provide prompt but fair justice in respect of minor service offences and as such, these trials are required to begin within one year of the date on which the offence is alleged to have been committed.16

This reporting period there were 553 summary trials and the average number of days from the date of the alleged offence to the start date of the summary trial was approximately 95 days. Of those 553 summary trials, 340 were disposed of within 90 days of the alleged incident, representing approximately 61 percent of all summary trials for the reporting period. Further, approximately 82 percent of all summary trials were commenced within 180 days of the alleged incident. Figure 2-16 shows a breakdown of the number of days from the date of the alleged offence to the commencement of the summary trial.

Once a charge has been laid by the appropriate authority and is referred to a presiding officer, the presiding officer is required to seek pre-trial legal advice before commencing the summary trial. Once that advice has been received from the unit legal advisor, the presiding officer may commence the summary trial.

Over the past five years, the number of days between the time of charge to the start of the summary trial has increased from an average of just under 17 days in the previous reporting period to an average of just under 20 days in the current reporting period. Figure 2-17 shows the average number of days from charge laid to the start of the summary trial over the last five reporting periods.

Figure 2-16: Number of Days from Alleged Offence to the Start of the Summary Trial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 0-30 days | 31-90 days | 91-180 days | 181-36 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases | 146 | 194 | 112 | 101 |

Figure 2-17: Number of Days from Charge Laid to Summary Trial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Days | 16.8 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 17.4 | 19.8 |

Courts Martial

Number of Courts Martial

During this reporting period, there were a total of 56 courts martial completed - 52 Standing Courts Martial (SCM) and four General Courts Martial (GCM) - representing just over ten percent of all service tribunals. Figure 2-18 shows the number of courts martial by year since 2012/13.

Figure 2-18: Number of Courts Martial by Year

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing Courts Martial | 60 | 60 | 60 | 40 | 52 |

| General Courts Martial | 4 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 4 |

Findings by Case at Court Martial

Of the 56 courts martial held during this reporting period, 46 of 56 accused persons were either found guilty or pleaded guilty to at least one charge and eight were found not guilty of all charges. One accused had all charges against him stayed, and in one case a mistrial was declared by the military judge. Figure 2-19 shows disposition by case over the past two reporting periods.

Figure 2-19: Disposition by Case

| Disposition | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage | Amount | Percentage | |

| Found Guilty of at least one charge | 5 | 10.63 | 7 | 12.50 |

| Pleaded Guilty to all charges | 36 | 76.59 | 39 | 69.64 |

| Not Guilty of all charges | 6 | 12.77 | 8 | 14.29 |

| Stay of all charges | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.79 |

| Withdrawal of all charges | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Mistrial | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.79 |

| Total | 47 | 100 | 56 | 100 |

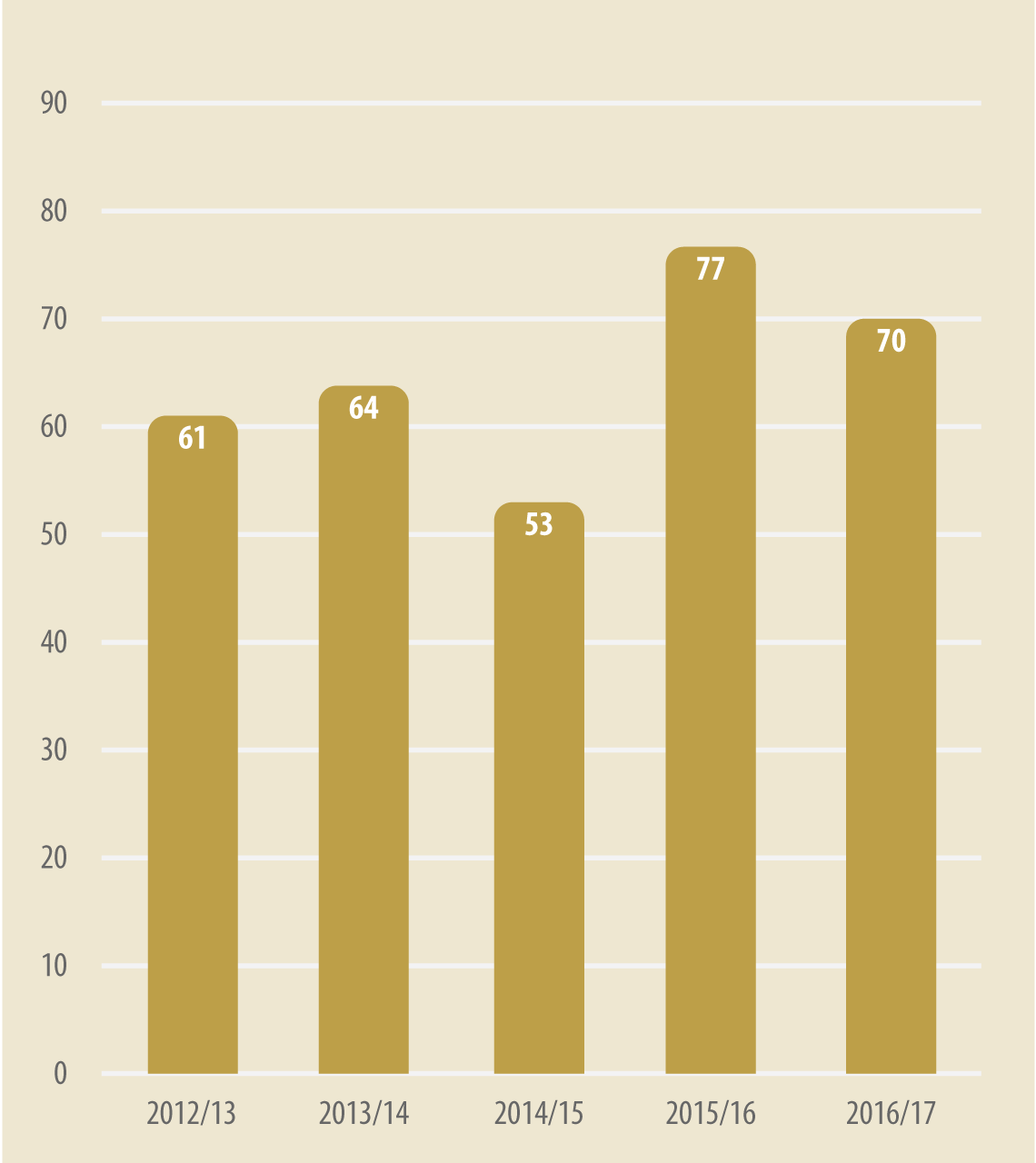

This reporting period, there were 39 guilty pleas, representing nearly 70 percent of all cases.17 As shown in Figure 2-20, the percentage of cases where the accused has pleaded guilty in such cases has fluctuated over the past five reporting periods between approximately 53 to 77 percent. The average number of guilty pleas in such cases for the current reporting period is higher than the five year average of 65 percent.

In the current reporting period, counsel for the prosecution and defence made joint submissions on sentence in 29 of those 39 courts martial where the accused pleaded guilty.18 Figure 2-21 shows a breakdown of the total number of courts martial where the accused pleaded guilty to all charges between those cases that proceeded by a joint submission and those cases where the sentencing hearing was contested.

Figure 2-20: Percentage of Guilty Pleas of all Courts Martial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Guilty Pleas of all Courts Martial | 61 | 64 | 53 | 77 | 70 |

Figure 2-21: Sentencing Hearings Following Guilty Plea

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Submissions on Sentence | 33 | 34 | 29 | 28 | 29 |

| Contested Sentencing Hearings | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

DMP Case Management

Referrals

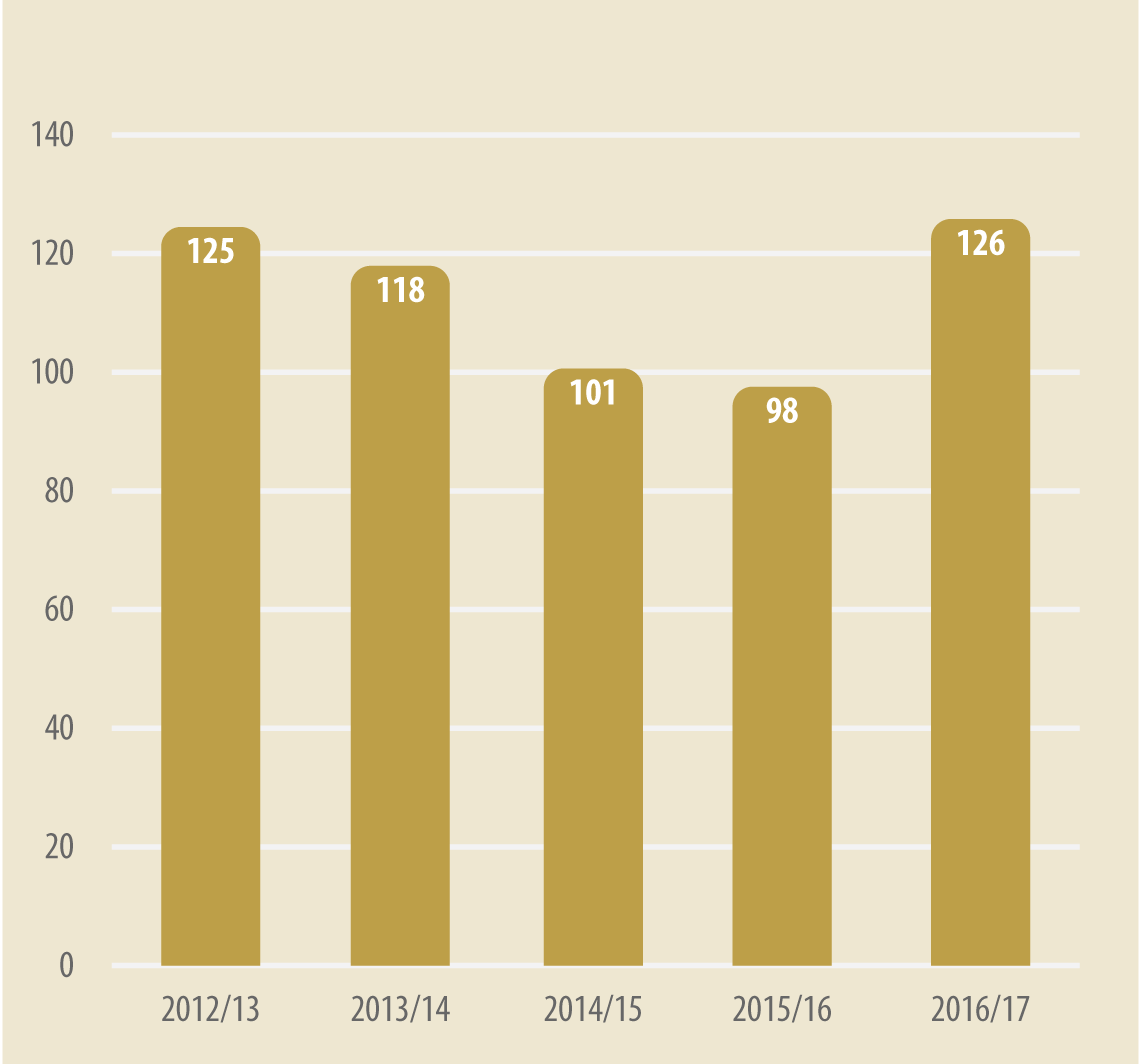

This reporting period there were 126 files that were referred to the DMP which represents an increase of 29 percent compared to the previous reporting period where there were only 98 files referred to the DMP.19 Figure 2-22 shows the number of referrals made to the DMP over the last five years.

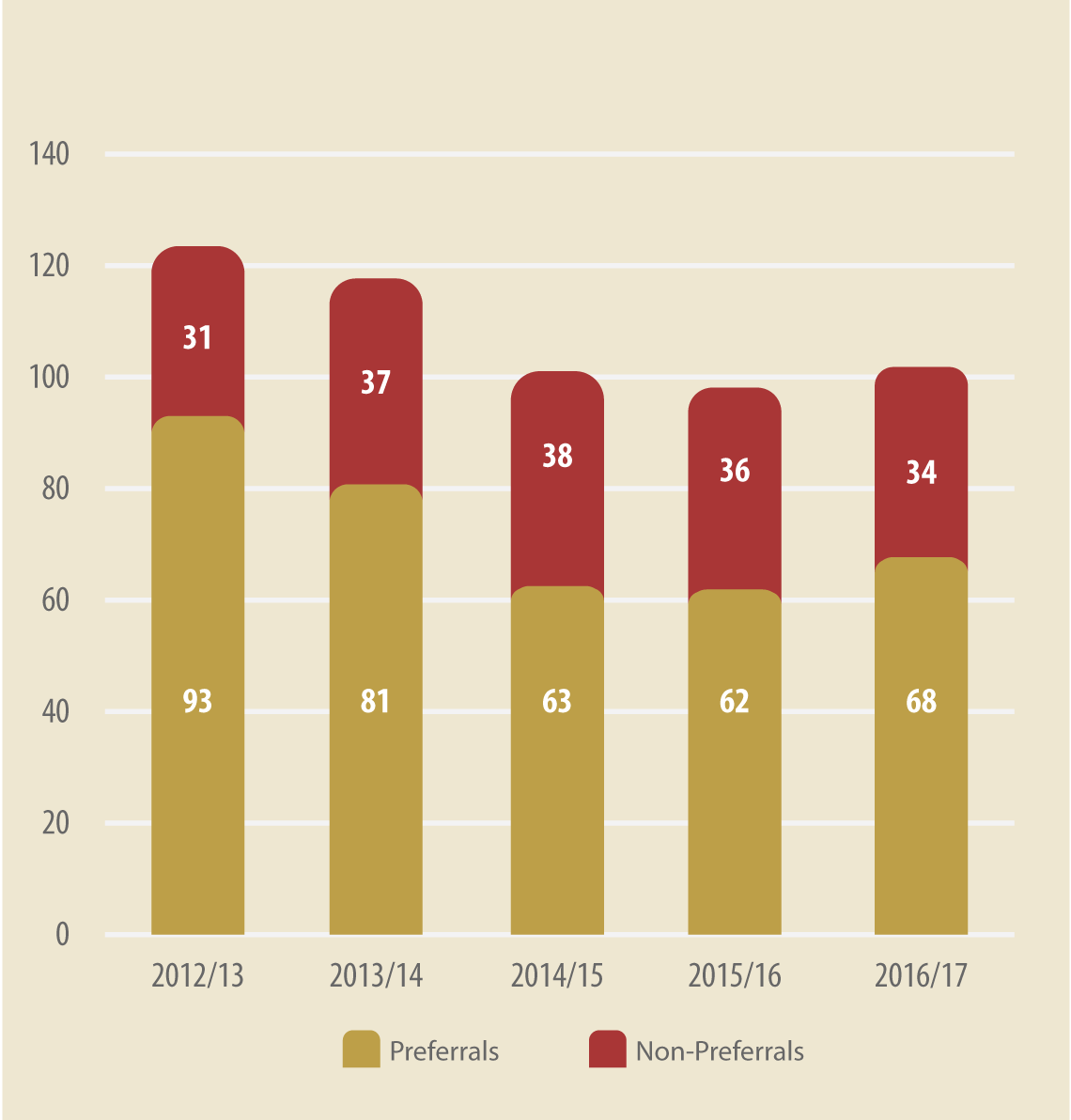

Preferrals and Non-Preferrals

This reporting period there were 68 files preferred for trial by court martial and 34 cases in which no charges were preferred.20 Of those 68 preferrals, 29 were referred to the DMP as a result of an accused electing to be tried by court martial and 39 were referred to the DMP as a result of a direct referral.21

The percentage of cases preferred for trial by court martial for this reporting period was approximately 67 percent.22 This is consistent with the past five reporting periods where the rate of preferrals has fluctuated from a high of 75 percent in 2012/13 to a low of 62 percent in 2014/15.

Figure 2-23 illustrates the number of files preferred by the DMP and the number of files where no charges were preferred over the past five reporting periods.23

Figure 2-22: Number of Referrals to the DMP

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Referrals to the DMP | 125 | 118 | 101 | 98 | 126 |

Figure 2-23: Preferrals and Non-Preferrals

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferrals | 93 | 81 | 63 | 62 | 68 |

| Non-Preferrals | 31 | 37 | 38 | 36 | 34 |

DDCS Representation

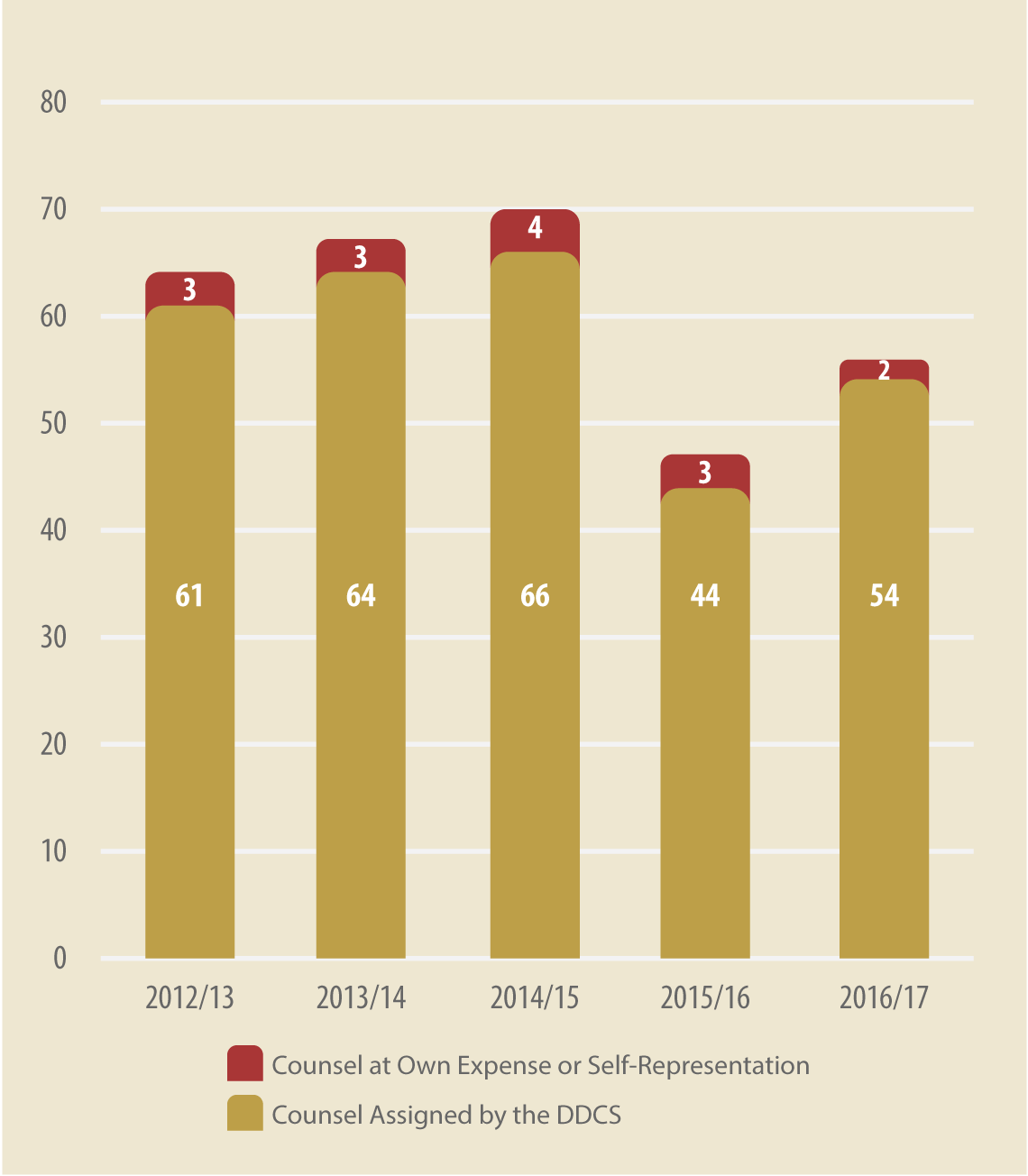

When facing trial by court martial, accused persons have the right to be represented by counsel assigned by the DDCS at public expense or they may retain civilian counsel at their own expense or choose not to be represented. This past reporting period, accused persons were represented by counsel assigned by the DDCS in 54 of 56 courts martial representing approximately 96 percent of all courts martial.24 This high percentage of accused persons represented by counsel assigned by DDCS has remained consistent over the past five reporting periods. Figure 2-24 shows the number of courts martial where an accused was represented by counsel assigned by the DDCS for the past five reporting periods.

Court Martial Sitting Days

The total number of days all courts martial sat in this reporting period was 213 days for an average of 3.80 days per court martial. Over the past five reporting periods, the average number of sitting days has ranged from a high of 3.92 days per court martial to a low of 2.91 with the five year average being 3.52 sitting days per court martial. Figure 2-25 shows the total number of court martial sitting days over the past 5 years.

Figure 2-24: Representation at Courts Martial by Counsel Assigned by the DDCS

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counsel at Own Expense or Self-Representation | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Counsel Assigned by the DDCS | 61 | 64 | 66 | 44 | 54 |

Figure 2-25: Court Martial Sitting Days

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Court Martial Sitting Days | 251 | 222 | 204 | 180 | 213 |

Timelines

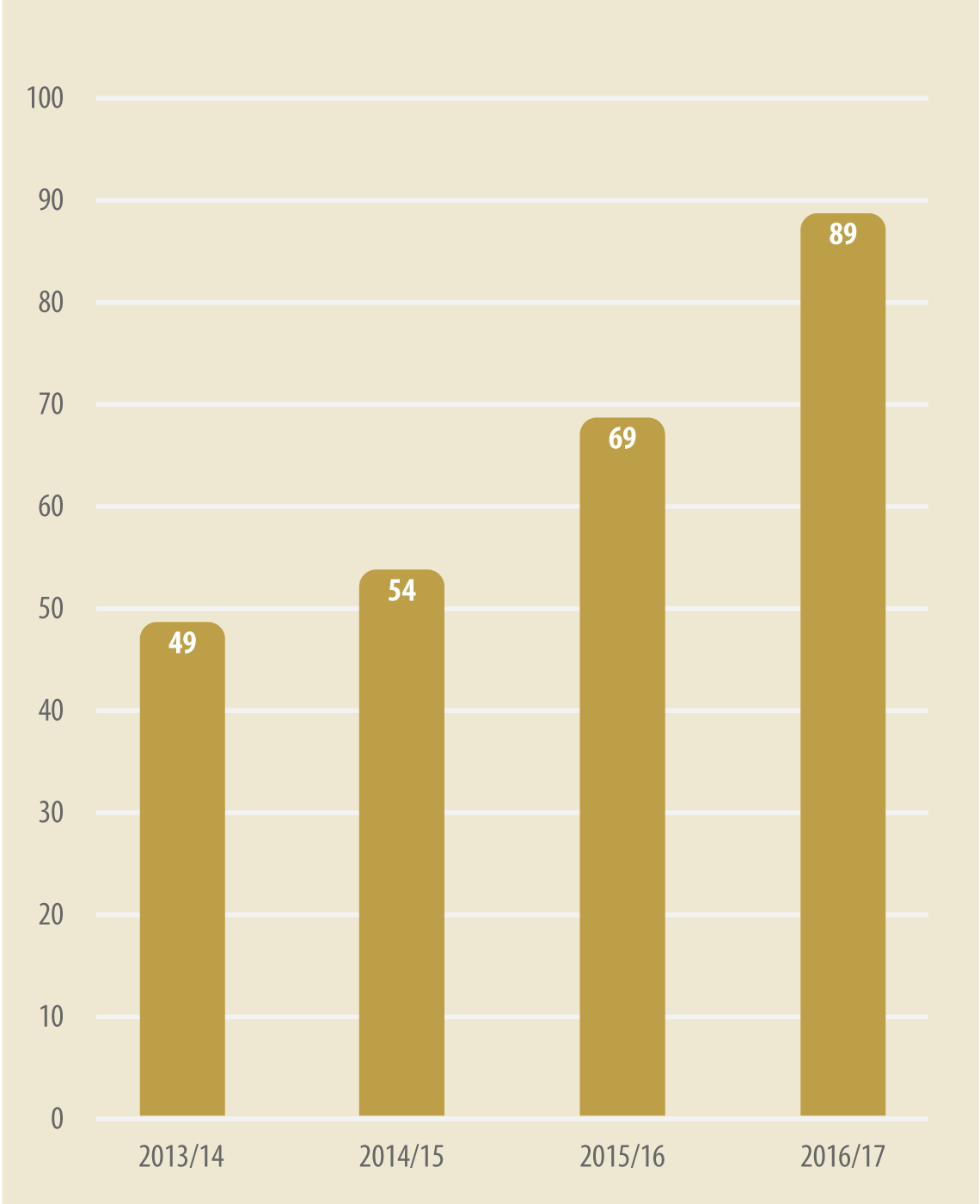

During this reporting period the average number of days from referral of a matter to the DMP until charges against an accused were preferred was approximately 89 days. This represents a 17 percent increase in comparison to the 2015/16 reporting period where the average number of days it took to prefer charges once a file was referred to the DMP was approximately 69 days. The average number of days that it took to prefer a charge once a referral has been received by the DMP has increased over each of the past four reporting periods.25 In the 2013/14 reporting period the average number of days was 49 and that number has nearly doubled to 89 days in the current reporting period. Figure 2-26 illustrates the average number of days from referral to preferral for the past four reporting periods.

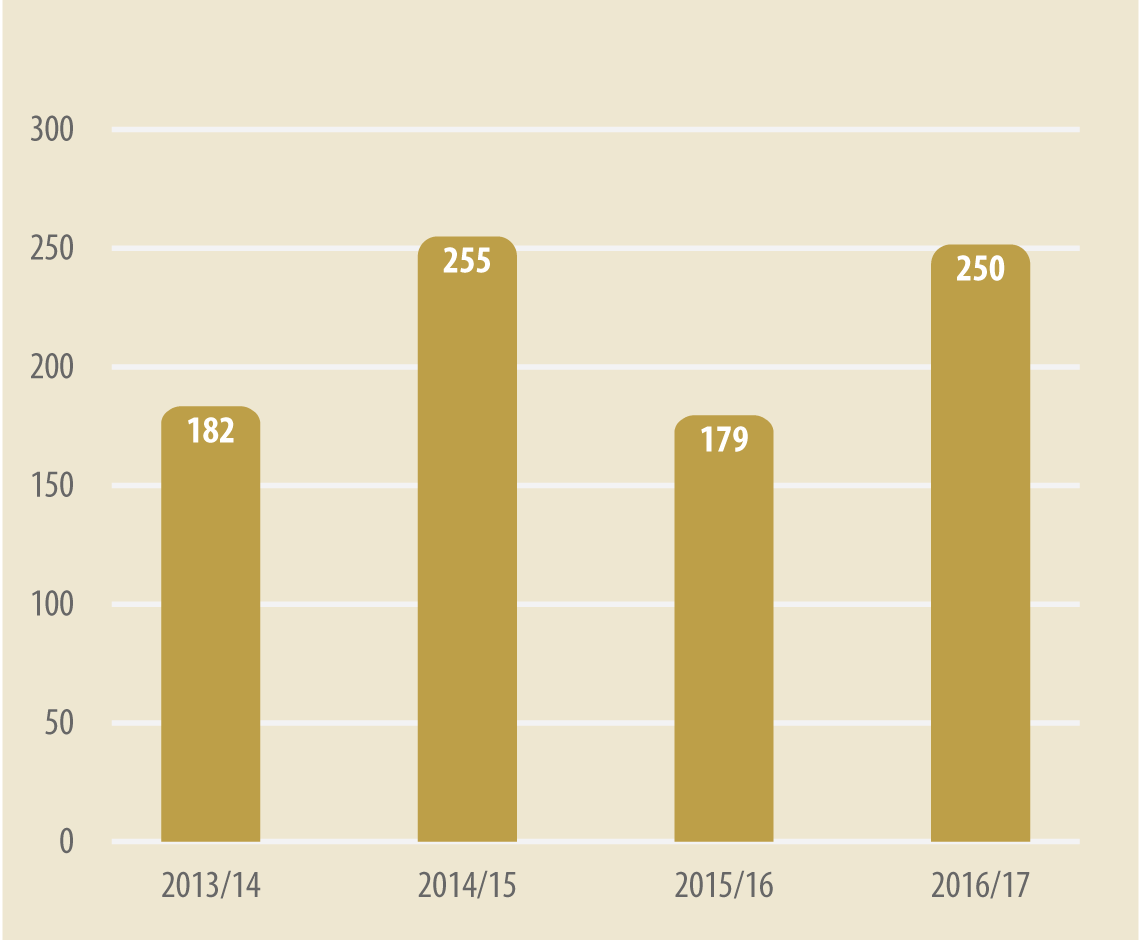

The average length of time that it took for a court martial to commence once charges against an accused were preferred also increased during the reporting period. In this reporting period the average number of days that it took for a court martial to commence once charges were preferred was 250 days. In the previous reporting period, the number of days between the preferral of charges and the start of court martial was 179 days. Therefore the average number of days that it took for a court martial to commence once charges were preferred increased by approximately 28 percent. Figure 2-27 shows the average length of time for a court martial to commence once charges against an accused were preferred for the last four reporting periods.

Figure 2-26: Number of Days from Referral of File to DMP to Preferral of Charges

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Days | 49 | 54 | 69 | 89 |

Figure 2-27: Number of Days from Preferral of Charges to Beginning of Court Martial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Days | 182 | 255 | 179 | 250 |

Early in the reporting period the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision in the case of R. v. Jordan26 which dealt with the right of an accused to be tried within a reasonable time. That decision created presumptive ceilings beyond which delay (measured from the time of charge to the actual or anticipated end of trial) is presumed to be unreasonable, unless exceptional circumstances exist. The court established a presumptive ceiling of 18 months where the delay is not attributable to an accused for cases tried in provincial court and 30 months for cases tried in the superior court. In the military justice system, the presumptive ceiling that applies has been held to be 18 months from the time of charge to the actual or anticipated end of trial.27

For this reporting period the average number of days from time of charge to the completion of court martial was 434 days, or just over 14 months. Figure 2-28 shows the average number of days from the time of charge to the completion of the court martial for the past four reporting periods broken down by various timeframes.28

Figure 2-28: Average Number of Days from Charge to Completion of Court Martial

See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Court Martial | 13 | 5 | 34 | 26 |

| Preferral to Court Martial | 182 | 255 | 179 | 250 |

| Referral to Preferral | 49 | 54 | 69 | 89 |

| Charge to Referral | 91 | 75 | 76 | 69 |

| Total | 355 | 389 | 358 | 434 |

It can be seen that over the past four reporting periods, the average time that it takes for a file to move through the referral process once a charge has been laid has decreased from an average of 91 days to 69 days. In addition, in the current reporting period, there was an average of 89 days from the time of referral to preferral and an additional 250 days, or just over eight months, between the preferral of charges and the beginning of the court martial. Therefore, the Office of the JAG is examining possible options to reduce overall delay in the court martial process.

Punishments at Court Martial

While only one sentence may be passed on an offender at a court martial, a sentence may involve more than one punishment. The 46 sentences pronounced by courts martial during the reporting period involved 80 punishments. A fine was the most common punishment, with a fine being imposed in 39 cases. Four punishments of imprisonment and four punishments of detention were also imposed by courts martial. Of those eight custodial punishments, two were suspended. In the context of the Code of Service Discipline, this means that the offender does not have to serve out the sentence of imprisonment or detention as long as he or she remains of good behaviour during the period of the sentence. Figure 2-29 breaks down sentences at courts martial for the past two reporting periods.

Figure 2-29: Punishments at Courts Martial

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dismissal | 2 | 1 | |

| Imprisonment | 5* | 4 | |

| Detention | 4 | 4** | |

| Reduction in Rank | 3 | 9 | |

| Forfeiture of Seniority | 0 | 0 | |

| Severe Reprimand | 10 | 6 | |

| Reprimand | 13 | 17 | |

| Fine | 32 | 39 | |

| Minor Punishments: Confinement to Ship or Barracks | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 69 | 80 | |

* Two of these punishments of imprisonment were suspended by the Military Judge.

** One of these punishments was suspended by the Military Judge.

Appeals to the Court Martial Appeal Court

During this reporting period, four new notices of appeal were filed with the Court Martial Appeal Court. Of those notices, two were initiated by the accused and two by the prosecution. This reporting period, the Court Martial Appeal Court rendered three decisions, one appeal on the merits in R. v. Royes and two motions for judicial interim release. The case of R. v. Royes is discussed in detail in Chapter Three.

Appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada

This reporting period there was one application for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court by the accused in the case of R. v. Royes, however the application was dismissed.

Inappropriate Sexual Behaviour

There are a number of offences under the NDA and the Criminal Code which may be used to try an accused for inappropriate sexual behaviour at courts martial. These include, but are not limited to, sexual assault, assault, accessing or possessing child pornography, disgraceful conduct, prejudice to good order and discipline, and ill-treatment of subordinates. In most instances it will be clear based on the specific charge whether the alleged conduct constitutes an allegation of inappropriate sexual behaviour. However, in some cases, it may not be as clear whether a particular charge constitutes an allegation of inappropriate sexual behaviour. Such a determination must be made taking into consideration all the relevant circumstances at the time.

In the current reporting period, there were 12 courts martial for inappropriate sexual behaviour. In those 12 trials, there were 24 different charges of inappropriate sexual behaviour including ten sexual assault charges, two charges of assault, four charges of prejudice to good order and discipline, seven charges of behaving in a disgraceful manner, and one charge of abuse of subordinates.29 This is in comparison to the previous reporting period where there were seven courts martial involving 23 charges of inappropriate sexual behaviour.

During this reporting period, four of the courts martial for inappropriate sexual behavior were contested, resulting in two accused being found guilty and two acquittals. In R. v. Beaudry, the accused was found guilty of sexual assault and sentenced to imprisonment for 42 months and dismissal with disgrace from the CAF. In R. v. Laferrière, the accused was found guilty of assault, ill-treatment of a person who by reason of rank was subordinate to him, and drunkenness, and was sentenced to a severe reprimand and a fine of $2500. The case of R. v. Beaudry is discussed in further detail in Chapter Three of this report.

In the remaining eight courts martial for inappropriate sexual behavior, the accused pleaded guilty to all charges on which evidence was brought by the prosecution. In seven of these eight courts martial, a joint submission on sentence was submitted by the prosecution and defence. All seven joint submissions were accepted by the military judge. Punishments in these cases included a reprimand, reduction in rank, and fines ranging from $500 to $5000.

Also, in five of the 12 courts martial for inappropriate sexual behaviour, seven charges of sexual assault or assault were either withdrawn by the prosecution or stayed by the military judge. In all of those five cases, the accused pleaded guilty to a lesser offence. A complete breakdown of all courts martial for inappropriate sexual behaviour can be found in Annex C.

Footnotes

1 The statistics reported and discussed in this report are current as of 6 June 2017.

2 R. v. Généreux, [1992] 1 S.C.R. 259; Mackay v. R., [1980] 2 S.C.R. 370 at 399; R. v. Moriarity, [2015] 3 S.C.R. 485.

3 An accused does not have the right to elect his or her mode of trial in two instances. First, where the accused has been charged with one of five minor service offences and the circumstances surrounding the commission of the offence are sufficiently minor in nature that the officer exercising summary trial jurisdiction over the accused concludes that a punishment of detention, reduction in rank or a fine in excess of 25 percent of monthly basic pay would not be warranted if the accused were found guilty of the offence. Second, where the charges are more serious in nature and require a direct referral to court martial.

4 See Note (B) to article 108.05 of the QR&O.

5 See section 179 of the NDA.

6 The Minister has instructed the DMP to act on his behalf for appeals to the Court Martial Appeal Court and the SCC.

7 All statistics contained in this Chapter were subject to a GBA+ analysis and no significant trends or findings were noted.

8 Following the court martial decisions in R. v. Nauss, 2013 CM 3008 and R. v. Brideau, 2014 CM 1005, the number of charges for unauthorized discharges pursuant to section 129 of the NDA decreased significantly in subsequent reporting periods. For further information on those decisions please refer to the 2012/13 and 2013/14 Annual Reports of the Judge Advocate General, respectively.

9 For the purposes of tabulating results, the offences of conduct or neglect to the prejudice of good order and discipline have been sub-divided into a number of categories including negligent discharges, sexual harassment, inappropriate relationships, alcohol offences, drug offences and other. For a detailed breakdown of the number of charges in each sub-category please refer to Annex A.

10 An accused will also not have the right to choose between summary trial and court martial in those circumstances where the charges require a direct referral to court martial.

11 More than one type of punishment may be awarded at a summary trial.

12 An inappropriate relationship is defined as an unreported adverse personal relationship.

13 The two charges for inappropriate personal relationships stemmed from one incident where both members failed to report their personal relationship as required by Defence Administrative Order and Directive 5019-1: Personal Relationships and Fraternization.

14 In one instance two CAF members asked a subordinate to show them intimate pictures of a female CAF member without her knowledge. The junior member showed the images to the two senior members. All three individuals were charged pursuant to s.129. Two were charged for making the request and one was charged for making the images available.

15 The two members were of different ranks with the senior member receiving the higher amount.

16 See sections 163(1.1) and 164(1.1) of the NDA.

17 A guilty plea is defined as a court martial where the accused pleaded guilty to all charges where evidence was introduced by the prosecution. It does not include those cases where an accused pleaded guilty to some charges and yet other charges were contested.

18 It has been stated by the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of R. v. Anthony-Cook (2016 SCC 43) that joint submissions play a vital role in contributing to the administration of justice by providing certainty and saving the system time and resources. For further information please refer to R. v. Ledoux (2016 CM 1019) in Chapter Three.

19 A referral to the DMP is where a matter has been referred to the DMP for trial by court martial for any one of a variety of reasons including an election by an accused to be tried by court martial or in those situations where the presiding officer does not have the jurisdiction to try the accused.

20 At the end of the reporting period there were still 24 cases awaiting a post-charge decision.

21 A direct referral means that the accused did not elect trial by court martial but had the charges referred to the DMP based on the nature of the charges, a determination by the presiding officer that he or she had insufficient powers of punishment to deal with the matter at summary trial, the rank of the accused or that the presiding officer had reasonable grounds to believe that the accused is unfit to stand trial or was suffering from a mental disorder at the time of the commission of the alleged offence.

22 This does not include those cases in which a decision had yet to be taken by the end of the reporting period.

23 In the 2012/13 reporting period one file that was referred to the DMP resulted in the member re-electing to be tried by summary trial, Therefore, this case is counted neither as a preferral nor as a non-preferral.

24 Counsel assigned by the DDCS may be uniformed members of the CAF or pursuant to s.249.21(2) of the NDA, the DDCS may engage the services of civilian counsel to represent accused persons.

25 Statistics on the number of days from referral of a file to the DMP to the preferral of charges have only been tracked for the past four reporting periods.

26 2016 SCC 27.

27 See R. v. Thiele, 2016 CM 4015. This case is discussed in detail in Chapter Three.

28 Statistics on the number of days from charge to completion of court martial have only been tracked for the past four reporting periods.

29 A complete summary of all charges tried at court martial can be found in Annex B.