Annexes

Annex 1 – Schedule “N” – Survivor Support ConsultationsFootnote 68

This document sets out a proposed consultation approach and schedule. Should circumstances require it, the process, schedule or representatives may be amended or changed by the agreement of the parties to address challenges and facilitate the objective of the consultation.

Consultation Group

- The lead representatives in respect of the consultations will be:

- Department of National Defence (“DND”)/CAF Representatives

- Executive Director, Sexual Misconduct Support and Resource Centre

- Director General, CAF Strategic Response Team – Sexual Misconduct

- One additional designate from one of the following: Canadian Forces Health Services, Canadian Forces Provost Marshall, Judge Advocate General, Chaplain General or other DND/CAF representative with responsibilities related to survivors of Sexual Misconduct, as determined by Canada

- Class Member Representatives

- Within thirty (30) days of the FSA being approved, Class counsel will select three (3) representative plaintiffs or Class Members.

- Department of National Defence (“DND”)/CAF Representatives

Objective

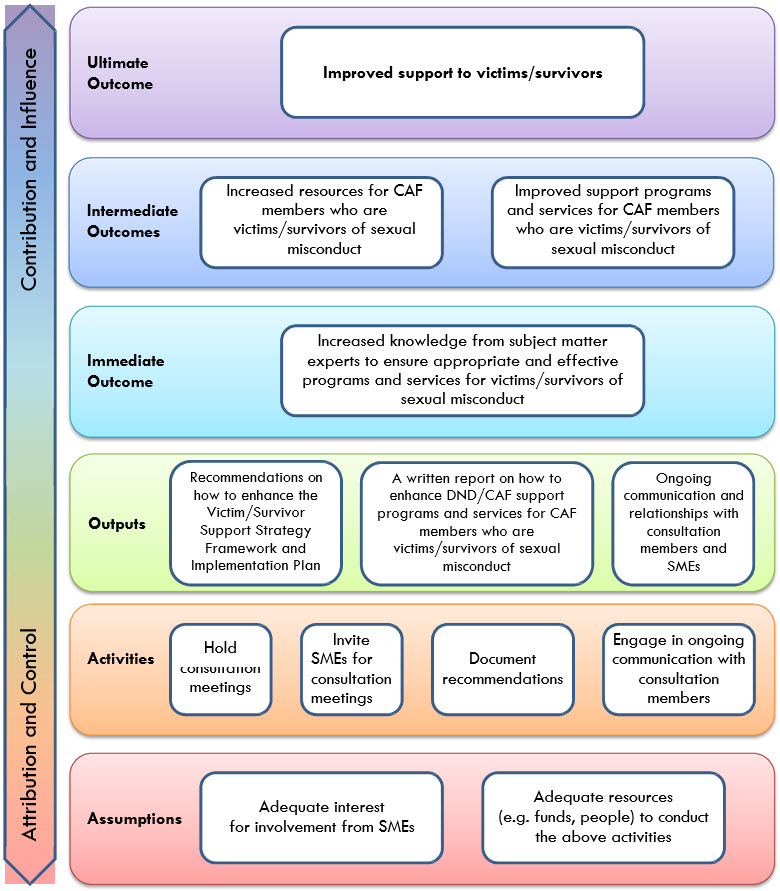

- The objective of the consultations is to obtain input from Class Member Representatives with respect to the DND/CAF efforts towards enhancing its resources and support programs for CAF victims/survivors of Sexual Misconduct. Specifically, the consultations will relate to:

- the National Victim/Survivor Support Strategy Framework and Implementation Plan (“NVSS”);

- Overall DND/CAF plans to enhance services for victims/survivors and efforts to ensure that subject matter expertise is integrated; and

- The DND/CAF strategy and plan for engagement of victim/survivor stakeholders on an ongoing basis.

Process

- Within sixty (60) days of approval of the FSA, the Consultation Group parties will hold one or two initial meetings. The objective of these meetings is to establish an informational foundation and context to understand current DND/CAF services, expertise and initiatives and identify areas where the input of the Class Member Representatives could be best employed. The Consultation Group will agree on:

- scheduling and meeting dates for the remainder of the Process, based on the process set out below;

- any other representation from services and programs within the DND/CAF; and

- any additional subject matter expertise that may be needed to support the work of the Consultation Group.

- Class Member Representatives will not be paid for their time or their advice. Canada shall be responsible for reasonable expenses incurred by the Class Member Representatives in the course of carrying out their obligations under this Schedule. Reasonable expenses may include meals, travel and accommodation in accordance with the Government of Canada National Joint Council Travel Directive. Class Member Representatives may be asked to sign an agreement with DND in order to facilitate the reimbursement of these expenses, in accordance with Government of Canada policies and procedures.

- Administrative support required for the work of the Consultation Group will be provided through the SMRC.

- In order to facilitate the work of the Consultation Group, DND/CAF will, at minimum, share information concerning the following:

- the status and current draft of the NVSS;

- the services and programs available to victims/survivors of sexual misconduct, as well as the planned enhancements;

- the current availability of and allocation of subject matter expertise providing advice on Sexual Misconduct in the CAF, including an update briefing on the SMRC’s mandate to provide such independent expertise and its ongoing efforts to do so. This could include, but is not limited to, providing the Class Member Representatives with the opportunity to meet with members of the External Advisory Council on Sexual Misconduct, as well as with additional SMEs from the DND/CAF, such as SMRC staff and advisors; and

- the structure and creation of ongoing formal mechanisms of consultation with victim/survivors, including the implementation of the SMRC’s Victim/Survivor Stakeholder Engagement Strategy.

- DND/CAF will present a list of no more than five (5) Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) within thirty (30) days of the Initial Meeting(s). From this list, the Consultation Group will jointly select at least one (1), and up to three, (3) SMEs to support these consultations.

- If necessary, DND/CAF will then arrange and establish any needed SME contracts (or other mechanisms) in accordance with government contracting rules and guidelines and Consultation Group objectives.

- Once the SME(s) have been identified, the Consultation Group will hold one or two formal meetings of representatives and SMEs. Further communications or meetings may be scheduled as required.

Reports and Recommendations

- Within one hundred and eighty (180) days following the approval of the FSA, the Consultation Group will prepare an initial summary report of its work for delivery to DND/CAF. If the report contains any formal recommendations, DND/CAF will provide a formal response within thirty (30) days of receipt of those recommendations.

- Within nine (9) months following the approval of the FSA, the Consultation Group will deliver its final report on its work, including any formal recommendations made and the DND/CAF’s response. This report will be provided to the Chief of Defence Staff and the Deputy Minister of National Defence. DND/CAF will translate the report and make it available publically within sixty (60) days of the report’s finalization. DND/CAF may also release a response to the report.

Annex 2 – Draft Sexual Misconduct Support Strategy Framework for Consultation with the SSCG (March 2020)

Vision

A system of support for CAF members affected by sexual misconduct that:

- is seamless and integrated, person-centred, trauma-informed, and evidence-informed

- treats all affected members with dignity and respect

- ensures information about, and access to, support – no matter where one is serving and whether or not an incident has been reported

- provides high quality, competent support, including specialized support for specific populations (e.g. culturally-responsive and gender-sensitive support)

- includes a holistic and comprehensive “menu” of support (e.g. career-related, spiritual, family-related, informational, emotional, practical)

- recognizes the importance of working together and in collaboration

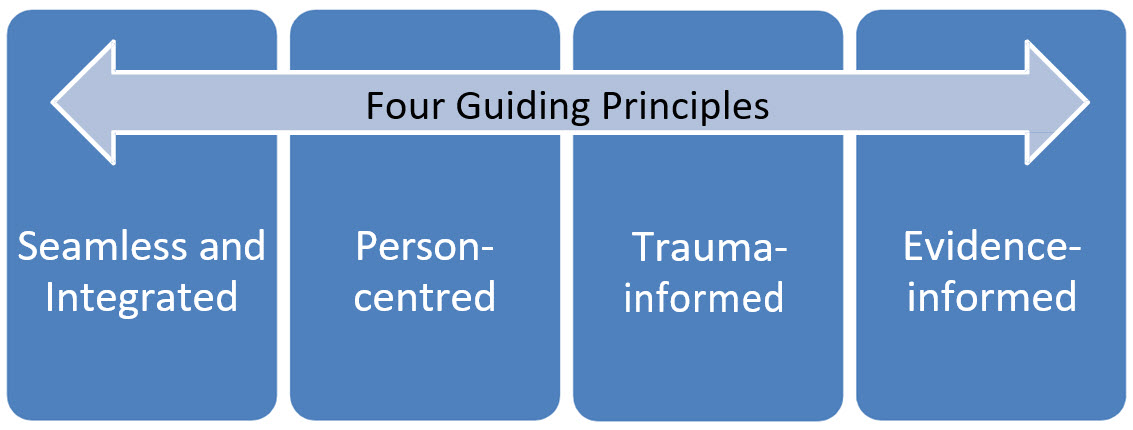

Long description

Four Guiding Principles

- Seamless and Integrated

- Person-centred

- Trauma-informed

- Evidence-informed

Eight Goals

- Establish a seamless and integrated continuum of support

- Reduce stigma and break isolation at all levels (social, institutional, chain of command, unit)

- Increase collaboration, engagement, and commitment

- Improve the quality and accessibility of information

- Embed person-centred and trauma-informed responses

- Enhance support provider capacity and competency

- Form leaders with relational skills

- Continue to build the evidence base

Annex 3 – Initial Questions to Guide the Work of the SSCG

- What do you see as some of the top gaps, challenges, and barriers that the Support Strategy must address?

- What major thematic areas/groupings can we identify in relation to identified support- related gaps, challenges, and barriers?

- Thinking about the support-related gaps, challenges, and barriers, what specific gaps or special topics might external subject matter experts need to help the SSCG with?

- What types of SMEs do we need to involve (external and/or internal to the CAF) to help inform development of the Support Strategy (e.g. specific skills, expertise, or perspectives)?

- What criteria should be used for selecting and agreeing upon SMEs?

- What are your views on the best potential fit for the additional DND/CAF member to form part of the consultation group?

- What presentations would you like to see covered at future meetings, including presentations on specific DND/CAF services or programs?

- What are your overall thoughts on the current working draft of the Strategy? What changes or additions are needed, generally? (e.g. language, tone, structure, content)?

- What are your views on the current vision, guiding principles, and goals? What is missing or should be changed?

- What engagement has been done so far and is being planned?

- How best to engage survivors on the Strategy?

- Who else needs to be brought into the dialogue and how (including any groups you feel have been missing from support-related dialogue up to now)?

Annex 4 – Subject Matter Expert Biographies

Rick Goodwin, MSW, RSW: Clinical Director, Men & Healing: Psychotherapy for Men.

Rick is a clinician and trainer on issues concerning men’s mental health. Much of his work over the past twenty years has focused on male sexual trauma – managing both regional and national initiatives in Canada. He currently directs Men & Healing: Psychotherapy for Men, a collaborative mental health practice in Ottawa, and oversees the online support group programming delivered by Men & Healing. In the US, he is the clinical and training consultant for 1in6, Inc., a non-profit organization that addresses male sexual trauma and recovery. He has been the primary trainer on clinical and first responder issues and has provided training to all branches of service with the US military.

Myrna McCallum: Miyo Pimatisiwin Legal Services

Myrna is a former prosecutor and Indian Residential School adjudicator who encourages other lawyers to become Indigenous inter-generational trauma-informed as their personal act of reconciliation. She educates leaders, lawyers, law schools, legal advocates, and judges on trauma-informed advocacy, cultural humility, vicarious trauma, resilience, and Indigenous inter- generational trauma through keynotes, training sessions, and lunch and learn lectures. She practices in the area of human rights law and conducts workplace investigations into sexual misconduct, human rights, and bullying & harassment complaints while also serving as an advisor to organizational leaders on how to address gender-based violence in the workplace through trauma-informed policies and procedures. Myrna is a former residential school student (Lebret IRS), mother and kokom (grandmother) to three sweet babies. She is from the historical Métis village of Green Lake and Waterhen Lake First Nation in Treaty Six territory.

Dr. Erin Whitmore: Executive Director, Ending Violence Association of Canada (EVA Canada).

Dr. Whitmore is a committed gender-based violence advocate with almost ten years of combined experience in direct service provision to survivors of sexual violence, as well as in research and policy analysis, program development, and stakeholder engagement on issues related to sexual violence. As the Executive Director of EVA Canada, Dr. Whitmore leads a national organization that works to address and respond to all forms of gender-based violence, and to strengthen collaboration among national, provincial, and territorial organizations and advocate at the national level. In addition to her experience working in the anti-violence sector, Dr. Whitmore completed a clinical social work internship at the Veterans Affairs Canada Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinic in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Through working primarily with the family members of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members, Veterans, and RCMP members who were living with an OSI, Dr. Whitmore developed an understanding of the CAF’s institutional structure and culture, including the distinct challenges survivors of sexual violence may face within the CAF.

Annex 5 – Standard Questions Provided to DND/CAF Organizations to Guide Informational Briefings Provided to the SSCG

- What is the mandate of your organization and how does it intersect with CAF members affected by sexual misconduct?

- What specific resources and supports does your organization provide to victims/survivors of sexual misconduct? Does your organization have presence at the regional level? How do victims/survivors access your resources and supports?

- To what extent are those in your organization (including both leaders and front-line personnel) trained on responding in a trauma-informed way to victims/survivors?

- What are some potential areas of vulnerability for experiencing further harm or for "falling through the cracks" for victims/survivors in interacting with your services/programs?

- What protocols or policies are in place in your organization to respond to incidents of sexual misconduct by and/or amongst your own personnel?

- To what extent does your organization employ gender and/or culturally sensitive practices?

- Are specific practices applied in order to meet the needs of any of the specific groups that have been identified as facing distinct barriers to reporting and help-seeking?

- What supports are in place for your own personnel who have a role in responding to incidents (e.g. secondary trauma and burnout prevention)?

- Are there differences in access to services for Regular Force, Primary Reserve or Rangers? What are some potential risk or vulnerability areas for survivors who are Reservists or Rangers, in accessing your services or programs?

- How does your organization work in collaboration with other victim/survivor support services across the DND/CAF? Do you see gaps or areas for improvement?

- Are there currently any additional victim/survivor resources or supports being considered or in development?

Annex 6 – Meeting Agendas – Informational Briefings by DND/CAF Representatives

Agenda – Survivor Support Consultation Group

19 August 2020, 1300 – 1600

| 1300 – 1305 | Participants log on to O365 | |

| 1305 – 1320 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1320 – 1420 | Directorate Professional Military Conduct (DPMC) | |

|

Rear-Admiral Rebecca Patterson | |

| 1420 – 1430 | Health Break | |

| 1430 – 1530 | Sexual Misconduct Response Centre (SMRC) | |

|

Elizabeth Cyr, A/Director | |

| 1530 – 1600 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

2 September 2020, 1300 – 1600

| 1300 – 1305 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1305 – 1320 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1320 – 1420 | Royal Canadian Chaplain Service (RCChS) | |

|

Major General Guy Chapdelaine | |

| 1420 – 1430 | Health Break | |

| 1430 – 1530 | Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) | |

|

Rear-Admiral Rebecca Patterson | |

| 1530 – 1600 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

1 October 2020, 1200 – 1500

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1320 | Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group (CAF TG) | |

|

Colonel Kevin Cameron, Director, Transition Services and Policy | |

| 1320 – 1330 | Health Break | |

| 1330 – 1430 | Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) | |

|

Mitch Freeman, Director General, Service Delivery and Program Management | |

| 1430 – 1500 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

15 October 2020, 1200 – 1500

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1320 | Integrated Conflict and Complaint Management (ICCM) | |

|

Alain Gauthier, Director General, ICCM | |

| 1320 – 1330 | Health Break | |

| 1330 – 1430 | Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA) | |

|

Dr. Stacey Silins, Defence Researcher, DGMPRA | |

| 1430 – 1500 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

29 October 2020, 1200 – 1500

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1300 | Canadian Forces National Investigation Service (CFNIS) and Canadian Forces Military Police Group (CF MP Gp) | |

|

LCol Eric Leblanc & Maj Phillip Casswell | |

| 1300 – 1340 | Directorate of Law/Military Justice Policy | |

|

LCol Marie-Ève Tremblay & Major Roseline Fernet | |

| 1340 – 1350 | Health Break | |

| 1350 – 1430 | Canadian Military Prosecution Service (CMPS) | |

|

LCol Maureen Pecknold | |

| 1430 – 1500 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

12 November 2020, 1200 – 1400

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1300 | Directorate of Human Rights and Diversity (DHRD), Military Personnel Command | |

|

Maj Nicholas Soontiens, DHRD | |

| 1300 – 1340 | Defence Advisory Groups (DAGs) and Networks | |

|

Lieutenant-Colonel Tania Maurice Kirk/Kaiya Hamilton Major André Jean Lisa deWit Chief Warrant Officer Suzanne McAdam Lana Costello Matthew Raniowski All |

|

| 1340 – 1400 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

26 November 2020, 1200 – 1500

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1300 | Indigenous Advisor to the Chaplain General (IACG) | |

|

Master-Warrant-Officer Moogly Tetrault-Hamel | |

| 1300 – 1340 | Advisor to the Chaplain General for LGBTQ2+ Issues | |

|

Major (Padre) Ian Easter | |

| 1340 – 1350 | Health Break | |

| 1350 – 1450 | Open Discussion | |

|

Master-Warrant-Officer Moogly Tetrault-Hamel Major (Padre) Ian Easter All | |

| 1450 – 1500 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

10 December 2020, 1200 – 1500

| 1200 – 1205 | Participants sign on to Zoom | |

| 1205 – 1220 | Welcome, Introductions, and Opening Remarks | |

|

SMRC | |

| 1220 – 1300 | Army Reserve and Canadian Rangers | |

|

Brigadier-General Nic Stanton, Director General, Army Reserve | |

| 1300 – 1340 | Naval Reserve | |

|

Commodore Mike Hopper, Commander, Naval Reserve | |

| 1340 – 1350 | Health Break | |

| 1350 – 1430 | Health Services Reserve | |

|

Colonel Roger Scott, Director, Health Services Reserve | |

| 1430 – 1500 | Wrap Up and Adjournment | |

|

SMRC/All | |

Annex 7 – Standard Questions Provided to Subject Matter Experts to Guide Development of Presentations to the SSCG

Q1 In June 2020, Consultation Group members developed a list of potential priority areas for consideration during the Consultation Group process. Looking at the list (below), are there any other areas that you feel have emerged from the briefings? If so, please explain.

- Continuity of care and support during CAF transitions

- Need for specialized sexual misconduct response teams at the regional level

- Chain of command training on trauma-informed approaches, responding to disclosures and trauma-informed investigations

- Throughout the briefing process, this area of focus has grown to include training not only for the chain of command but for anyone providing support to survivors and all actors in the military justice system; and not only basic training on trauma-informed approaches but also specialized training specific to a person’s role

- Abuse of power by people in positions of trust or authority

- Addressing the needs of specific survivor groups (e.g., male, Indigenous, 2SLGBTQ+ survivors)

Q2 Based on what you have learned in your work, what does “a victim-centred and trauma- informed approach” mean to you?

Q3 What key elements make for an overall good approach to survivor support in order to be meaningful, impactful, and effective?

Q4 “Support” is a broad term and can encompass non-specialist or more ‘generic’ (non- specialist, providing support in relation to many issues beyond sexual misconduct) and specialist services (providing support tailored to survivors of sexual misconduct, specifically). Based on the organizational briefings you have attended so far during this process:

- What would you change about ‘generic’ service provision if you could?

- How could specialist support services be improved in the future?

Q5 Is there a type of support that you would like to see in place but that does not seem to currently exist (e.g. independent legal advice, peer support, other)?

Q6 What are your thoughts on how to balance a desire for regional/local services (including Hub or one stop services) with recommendations for specialist services tailored to diverse client groups and identities?

Q7 Survivor support providers, including those with a justice orientation, often have partnerships and collaborations with communities. What opportunities do you see for CAF-based survivor support providers to collaborate with community-based survivor supports?

Q8 Based on your experience, what are some promising approaches and/or lessons learned about engaging survivors (i.e. engagement processes to include and involve survivors in the design of support initiatives to ensure that they reflect and meet their needs) that could be adapted to the military context?

Q9 Are there any new/emerging conversations that the Support Strategy should be paying close attention to? (e.g. emerging work on coercive control and how coercive control plays a role in survivors’ ability to seek and access support; others?)

Q10 Are there any international promising/best practices that you think are particularly relevant to work to develop a Support Strategy for the CAF?

Annex 8 – SME Reports – Supporting Survivors of Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces: Recommendations to Inform the Development of the Survivor Support Strategy

Submitted to: Survivor Support Consultation Group (SSCG) May 24, 2021

About the Ending Violence Association of Canada

The Ending Violence Association of Canada (EVA Canada) is a national organization that works to address and respond to gender-based violence. EVA Canada strives to strengthen collaboration among national, provincial, and territorial organizations to build understanding about gender- based violence and advocate at the national level.

This report was prepared by Dr. Erin Whitmore, Executive Director, Ending Violence Association of Canada.

The scope of this report

This report has been produced in accordance with the requirements set out in Schedule “N” of the CAF/DND Class Action on Sexual Misconduct Final Settlement Agreement for the Department of National Defense. This report reflects the scope identified by Sexual Misconduct Response Centre (SMRC) to provide recommendations to inform the development of the National Victim/Survivor Support Strategy Framework and Implementation Plan focused on the following areas:

- supporting survivors of sexual misconduct in general

- supporting sexual and gender minority survivors of sexual misconduct

This report is divided into four sections:

- Overview of the Survivor Support Consultation Working Group (SSCG) process

- Context for recommendations

- Recommendations for supporting survivors in general

- Recommendations for supporting sexual and gender minorities

Overview of the Survivor Support Consultation Working Group (SSCG) Process

The recommendations presented in this report respond to information shared through a series of meetings of the Survivor Support Consultation Group (SSCG) between June 2020 and May 2021. These meetings were organized and facilitated by the Sexual Misconduct Response Centre (SMRC) and featured presentations by a variety of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) departments, services, and advisory committees.

As defined in Schedule “N,” the purpose of the SSCG is “to obtain input on CAF/DND efforts towards enhancing its resources and support programs for CAF victims/survivors of sexual misconduct.” The presentations delivered by representatives of various CAF departments, services, and advisory committees provided some preliminary information about the structure of these various entities and their responses to sexual misconduct. However, there are a number of ways that this process could be improved to facilitate a more survivor-centred, comprehensive, and collaborative approach to understanding the needs of CAF survivors of sexual misconduct and the current barriers to services.

These include:

- Creating a process to hear directly from a diverse array of survivors about their experiences, needs, and recommendations for improving support

- Creating a process to facilitate conversation about the experiences of Indigenous and 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members and to discuss the distinct recommendations for support that would best support these members

- Improved dialogue and collaboration with CAF members from a variety of ranks and positions about the sexualized and gendered culture of the CAF, and how they understand this culture to create challenges for addressing sexual misconduct and providing support to survivors

- Less emphasis and focus on explaining the organizational structure of various CAF departments and more focus on explaining the specific challenges and barriers these structures create for survivors seeking services

- Opportunities to meet with CAF representatives for follow-up consultation sessions

- Increased access to information about the specific strategies, protocols, training programs and modalities used by various units and departments to address and respond to sexual misconduct

- Opportunities to engage with diverse external advocates and experts, including Veterans of the CAF, to explore components of the proposed Survivor Support Strategy

In acknowledgment of the limitations of the SSCG process, this report is presented as a starting point for further conversation and collaboration that should include diverse survivors, external advocates, and CAF/DND members and Veterans in identifying strategies for supporting CAF survivors of sexual misconduct. Prior to the submission of the Survivor Support Strategy to the CAF/DND it would be beneficial for the SMRC to undertake additional effort to deepen the level of consultation and review to ensure that this important strategy reflects the true needs of those it is intended to serve.

Context for Recommendations

The stated goal of the draft Survivor Support Strategy presented to the SSCG is to create a “seamless and integrated, person-centred, trauma-informed, and evidence-informed, collaborative, and specialized approach to support” for CAF members affected by sexual misconduct.Footnote A1 Ensuring support is available to individual CAF members and their families is essential. However, approaching the tasks necessary to create and provide support cannot be limited only to improving individual services. Rather, supporting survivors of sexual violence requires concrete action aimed at undoing the power dynamics and mechanisms that allow sexual violence to happen in the first place. This includes developing an analysis and understanding of the gendered and sexualized culture of the CAF, and the way that the beliefs, attitudes, practices, and ways of organizing within that culture perpetuate a rape-supportive culture. It also requires confronting how misogyny, hypermasculinity, homophobia, transphobia, racism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination are historically built into the very structure and values of the CAF.

The recommendations presented in this report reflect the position that the Survivor Support Strategy and the subsequent work of supporting survivors and their families who have experienced sexual misconduct within the CAF must be rooted in actions that work toward systemic and institutional culture change. The call for institutional and culture change has now been widely cited in numerous reports and recommendations, and it is a vital and fundamental first step in creating effective support for survivors both individually and collectively.

In keeping with these previous findings and recommendations, this report approaches the work of supporting survivors through an intersectional, feminist, and structural analysis of the problem of sexual misconduct. In doing so, it formulates actions for support in ways that aim to challenge and resist individualizing or pathologizing survivors or decontextualizing understandings of the causes and impacts of sexual violence from their basis in the CAF’s structure and culture.

In this approach, supporting survivors means not only creating accessible individual services that ensure survivors have their safety, health, emotional, financial, and spiritual needs met in the aftermath of violence. Supporting survivors also involves the ongoing work of positioning sexual misconduct as the inevitable consequence of colonial, patriarchal, ableist, racist, and heteronormative systems that create the conditions within which violence against those with the least power in these systems has been and continues to be ignored, accepted, and in some cases encouraged within the CAF. As such, the mechanisms of support available to address the individual needs of survivors are only so good as the efforts being made to change the system that has created and continues to foster a culture that allows sexual violence to happen in the first place.Footnote A2

The recommendations that follow offer potential routes through which to use the Survivor Support Strategy to reinforce the link between support for survivors at the individual level and support for survivors through institutional and culture change.

Recommendations for survivors in general

The following recommendations relate to survivors in general as this was defined by the SMRC. This means that these recommendations are meant to address strategies for strengthening services and supports within an ongoing institutional change effort that could benefit all survivors of sexual misconduct.

Recommendation 1: Develop and implement an ongoing consultation process that involves and centres the expertise of survivors within the CAF, Veterans, and external sexual violence advocates in all aspects of the development, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of policies and initiatives to support survivors and address sexual misconduct in the CAF. More specifically:

- The SMRC/CAF/DND should review its practices and process for consultation and engagement with survivors and external advocates in collaboration with these groups to ensure a consistent, inclusive, mechanism for collaboration and consultation.

- The SMRC/CAF/DND should ensure that all consultation initiatives include a diverse array of survivors and external advocates representing a variety of backgrounds, identities, and experiences with special attention to groups who have historically and continue to be marginalized within the CAF, including women, Indigenous, 2SLGBTQ+, and male survivors of sexual violence.

- Consultation with survivors and external advocates should be led or co-led by an experienced, external facilitator rather than being designed and facilitated by internal SMRC/CAF/DND staff.

- Any CAF member/survivor who participates in consultation initiatives should be financially compensated for their time and effort above their regular salary. Resources should also be made available to survivors engaged in consultation work should their participation in such consultations trigger the need for additional emotional or other forms of support. Likewise, all external consultants should be financially compensated for their time and effort.

- Consultation and stakeholder engagement should be ongoing and not limited only to the development phase of policies, strategies and other initiatives. Survivor-centred and external advocate consultation must be a key practice incorporated into the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of all efforts to address sexual misconduct and survivor support services within the CAF.

- Prior to its submission to the CAF/DND, the Survivor Support Strategy should undergo a comprehensive review in addition to the review being done by the SSGC. This consultation process should be led by a facilitator external to the SMRC/CAF, and should ensure adequate opportunity for input from survivor-led groups who have expressed interest in being involved in the development of these policies,Footnote A3 as well as a more diverse array of external organizations and advocates with experience in supporting survivors of sexual violence.

Recommendation 2: Establish a framework for understanding and addressing sexual violence in the CAF that is applied consistently across the CAF, including in the provision of individual supports. This framework should reflect an intersectional, systemic analysis and understanding of sexual violence. It should aim to promote trauma-informed, violence-specific responses; honour the strength and resilience of survivors; and be committed to identifying and exploring alternatives that exist external to the chain of the command and the CAF with a focus on enhancing options for survivors.

Recommendation 3: Identify, acknowledge, and address the pervasive problem of reprisals and other forms of secondary victimization experienced by CAF survivors following disclosures of sexual violence by:

- Conducting research and consultation with affected members to document the types of reprisals and secondary victimization experienced by CAF survivors, and the levers through which these occur. This may include but is not limited to further investigation of the various types of reprisals and secondary wounding already identified by CAF survivors: changes in treatment by unit members; job relocation or changes; career interruptions or endings; lack of specialized or trauma-informed responses from those in helping positions; lack of specialized training or trauma-informed responses by investigators or other representatives involved in the investigation and prosecution of sexual violence.

- Conducting research and consultation with affected members to document how reprisals and secondary victimization are embedded in the gendered and sexualized military culture, and how certain groups, including women, 2SLGBTQ+ members, Indigenous members, and male survivors are distinctly impacted.

- Ensuring that support and services for survivors are designed to address the significant psychological, physical, economic, spiritual, and employment impacts of sustained reprisals and secondary victimization as an additional component of military sexual trauma and military sexual misconduct.

- Engaging with external, community-based advocates with expertise in developing and delivering training on secondary victimization to create and deliver education and training focused on raising awareness about secondary victimization, its impacts, and strategies for avoiding it as one part of a broader, comprehensive education and training program on sexual misconduct and violence.

Recommendation 4: Implement mandatory and continuous CAF-wide education and training on preventing sexual violence and responding to disclosures of sexual violence that is developed, facilitated, and evaluated in partnership with external subject matter experts and trainers.

In general, training and education initiatives on sexual violence should:

- be developed and delivered in collaboration with external advocates/experts and in keeping with evidence-based best practices in sexual violence prevention and response training protocols.

- include content on consent, rape supportive attitudes and beliefs, being an effective bystander, understanding the distinct experiences of sexual violence for different groups, the intersection of sexual violence and colonialism, transphobia, racism, sexism and misogyny, and address the distinct ways in which the history and culture of the military create conditions in which sexual violence happens.

- not be limited to a single training but repeated regularly throughout an individual’s career

- engage learners and leaders in meaningful and difficult conversations, and require demonstration of a competent understanding of key concepts and skills introduced in the training.

- be tailored to reflect the distinct responsibilities and roles of different departments and positions. This will require the development and delivery of additional specialized, unit and department-specific training to CAF leadership, health services, Canadian Forces National Investigation Service, Chaplain services, Veteran’s Affairs, SMRC counsellors/staff, and others who occupy distinct roles within the CAF.

- be subject to external monitoring, evaluation, and revision as needed.

Recommendation 5: Continue to develop and strengthen a centralized and integrated process for accessing all forms of support that is responsive to current barriers to services as these are identified by survivors and relevant service providers.

Consideration may be given to the following:

- Further developing CAF-wide understanding about how and where to direct those in need of support related to sexual misconduct

- Enhancing the capacity of the SMRC and other relevant departments to provide information about options for support that are external to the CAF, and to make connections with these external supports and services

- Further developing a sexual misconduct systems navigator position(s) to serve as a consistent, ongoing point of contact as an individual navigates all aspects of seeking support, reporting, and other needs

- Developing easily accessible and clearly articulated information that fairly reflects the process for reporting sexual misconduct; the potential challenges in reporting; the expected length of time for action related to reporting; and any other information deemed important by survivors that is necessary to make an informed decision about reporting sexual misconduct

- Ensuring equal access to services for all CAF survivors regardless of where they are located in Canada, and/or CAF survivors who require support while serving outside of Canada

- Ensuring equal access to services for all CAF members, including Veterans, civilians who interact with the CAF, and other members currently not serving.Footnote A4

Recommendation 6: Ensure timely access to specialized crisis and long-term sexual violence individual and group counselling for all survivors. The following should be considered in the ongoing development, review, and delivery of specialized sexual violence counselling services:

- Ensuring that sexual violence counselling services are provided by individuals with specialized training and understanding of sexual violence who are equipped to offer a variety of approaches and interventions to meet the distinct needs of different survivors

- Recognizing the limitations imposed by what is considered ‘evidence-based’ treatments in the CAF. Provide options for survivors to receive treatment where and how they want that are not limited to medicalized treatments and CBT, PE, and EMDR

- Ensuring that sexual violence counselling services are equipped to provide a broad range of supports to address needs beyond the psychological and mental health impacts of sexual violence. Supports identified as important by members of the SSGC as especially important include those that will provide support related to spiritual well-being

- Reflecting the need for counselling services identified by survivors, such as on-line peer support counselling and inclusion of military sexual trauma at Operational Stress Injury clinics. These services would also be made available in ways that address the distinct needs for crisis and on-going therapeutic support for CAF members based in locations where in-person counselling may not be available or feasible

- Supporting peer-led initiatives by asking them what they need to continue doing their work.Footnote A5

- Including options for counselling services external to the CAF/SMRC that are equipped to provide specialized sexual violence-specific support

Recommendation 7: Identify and implement measures to continue to develop and strengthen options for support external to the CAF/DND/SMRC, such as those offered through the SMRC’s Response and Support Coordination Program, including:

- Engaging in a review and consultation process with participating community-based sexual assault centres (SACs) and other service providers involved in the Coordination Program to date to determine strengths and weaknesses in this program.

- In consultation with participating organizations, adapt the terms and requirements of the Coordination Program in ways that speak to the realities of SACs and other community- based service providers, including strategies that ensure the Coordination Program reflects the ongoing challenges in human and financial resources experienced by these organizations. This includes recognizing that SACs can be rich sources of information, and are also precariously funded, which sets up the possibility that knowledgeable counsellors may need to find time to fit this important collaborative work into their client work. Dedicated space for MST/CAF consultations on counsellor schedules is an important consideration.

- Create opportunities for the provision of specialized training in military sexual trauma, military culture, services, and other forms of professional development to further equip external service providers with information necessary to respond to the distinct needs of CAF survivors.

Recommendation 8: Continue to foster mechanisms for reporting sexual misconduct external to the chain of command, and review and strengthen all aspects of the reporting and investigation process for responding to sexual misconduct. These include:

- Providing safe reporting options outside of the chain of command

- Ensure reports of sexual misconduct are received, investigated and prosecuted by a fully independent, autonomous entity, external to the CAF, and separate from the SMRCFootnote A6

- Increase pathways for reporting, including exploring options for on-line reportingFootnote A7

- Provide the option for survivors of a sexual criminal offence to choose to have their case handled by the civilian justice system

- Improving the reporting and prosecution processes for survivors to feel empowered and to reduce revictimization, including:

- Access to female investigators when requested

- Options for emotional support during the reporting process (i.e. support person/animal)

- Trauma-informed interviewing carried out with empathy and understanding

- Confidentiality policy that ensures anonymity by leaving out the squadron/unit of the survivor

- Reporting options and processes adapted to the unique needs/circumstances of the realities on the ground, for all survivors to have access to the similar levels of options, supports and confidentiality (i.e. in contained or remote spaces such as navy ships, foreign ports, etc.)

- Ensure that all survivors of sexual violence have access to a formal and thorough investigation process no matter their location (and not replaced by informal unit disciplinary investigations)

- Ensure mechanisms in place to ensure the ongoing safety of survivors once they have reported

- Ensure investigators, prosecutors and judges understand interlocking systems of oppression, including sexism, homophobia, gender-based violence, misogyny, ableism and how sexual violence fits into the sexualized and gendered culture context of the CAF

- Ensure that complainants in the military justice system have the same rights and protections as civilian complainantsFootnote A8

Recommendations for supporting sexual and gender minorities who have experienced sexual misconduct in the CAF

Addressing the distinct needs of sexual and gender minority (SGM) survivors of sexual misconduct within the CAF has been identified as a priority by the class action members of the SSGC.Footnote A9

When it comes to addressing the distinct needs of 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members, there appears to be significant gaps in understanding the prevalence and nature of experiences of sexual violence, and limited information available about the steps being taken to ensure that 2SLGBTQ+ survivors of sexual misconduct in the CAF have access to specialized services that respond to their diverse and distinct needs. Data on the prevalence and nature of sexual violence in the Canadian population more broadly show that individuals belonging to a sexual and gender minority experience higher rates of various forms of sexualized violence than cis- gender, heterosexual Canadians. For instance, recent Statistics Canada data shows that excluding violence committed by an intimate partner, sexual minority Canadians were more likely (59%) to have experienced physical or sexual assault both since the age of 15 and in the past 12 months than heterosexual Canadians (37%) and that violence was more likely to result in injuries.Footnote A10 Of particular importance to addressing sexual misconduct within the CAF are findings from Canada-wide data showing the increased exposure to sexualized violence and harm within the workplace experienced by those identifying as a sexual and/or gender minority. For example, Statistics Canada data shows that transgender Canadians were more likely to be the target of unwanted comments about sex, gender, sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation, and also unwanted sexual attention than their cisgender counterparts, and sexual minority Canadians were twice as likely to experience unwanted sexual behaviour at work.A11 Despite the extent of sexual violence, sexual and gender minorities often face additional barriers in accessing support.

Understanding the nature of these barriers within the CAF is important to providing effective services.

Sexual misconduct directed against 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members is rooted in the gendered and sexualized culture that exists within the CAF that upholds and rewards hetero-normative masculinity.A12 Providing individual services and support that reflect the distinct experiences of 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members is one part of ensuring that the CAF addresses sexual misconduct against 2SLGBTQ+ members. Equally important is the need to ensure that efforts directed toward institutional and culture change address the specific ways in which the gendered and sexualized culture of the CAF perpetuates homophobic, biphobic, transphobic, and other forms of structural and systemic violence against 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members.

The following recommendations offer starting points for improving the CAF’s response to sexual misconduct experienced by 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members. Further review of these recommendations should be done in conversation with a diverse group of 2SLGBTQ+ CAF members/survivors and external advocates/organizations specializing in 2SLGBTQ+ issues.

Recommendation 1: Adopt an intersectional, distinctions-based approach to all aspects of the development and implementation of supports for sexual and gender minority survivors that centres their experiences and expertise. Sexual violence effects different CAF members in different ways. Sexual misconduct requires a diversity of responses that reflect an intersectional understanding of experiences of power and oppression within the institutional system and culture of the CAF rather than a one-size fits-all response. An intersectional analysis and orientation to addressing sexual misconduct considers how gender, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, race, language, ability, Indigeneity, and other identity factors intersect with various structures, systems, and forms of discrimination within and outside of the CAF. This requires the CAF to not only address sexism and misogyny but also racism, homophobia/transphobia, ableism, and other forms of discrimination within its efforts to support survivors and address sexual misconduct.

Recommendation 2: As part of its broader efforts at institutional and culture change, the CAF should continue ongoing, meaningful institutional acknowledgement of CAF’s history of structural violence and discrimination against sexual and gender minorities. This process and acknowledgement should be guided by and occur in collaboration with members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community within the CAF.

Recommendation 3: Deepen the evidence-based understanding of the diverse experiences of sexual and gender minorities within the CAF that includes but is not limited to experiences of sexual misconduct. Research should:

- collect disaggregated data on different sexual and gender minority identities and other identity factors

- be developed in collaboration with allied community-based organizations and others with expertise in research focusing on sexual and gender minority experiences

- include an institutional audit to identify the barriers to services that are specific to a sexual and gender minority CAF members

Recommendation 4: Mandatory ongoing training for all CAF members in all positions on sexual and gender minorities specific to sexual violence and trauma response and prevention. This training should:

- Promote an intersectional, distinctions-based analysis of violence

- Include modules on rape-supportive culture and beliefs distinct to sexual and gender minorities

- Be developed in collaboration with allied advocates and/or those with lived experience within the CAF

- Be delivered by advocates or others with expertise specific to the experiences of sexual and gender minorities

- Require in-person participation and engagement (i.e. not an online training that can be taken alone) and demonstration of competent understanding of training content

- Be subject to evaluation, monitoring and reviewed at regular intervals

Recommendation 5: Develop or enhance prevention, education, and awareness campaigns that include and acknowledge specific forms of violence against sexual and gender minorities.

Recommendation 6: Develop and foster sexual and gender minority-specific understandings of and responses to trauma and violence within the SMRC and throughout the CAF including:

- Developing and adopting a trauma-informed framework for supporting survivors that is inclusive of the additional and distinct forms of trauma experienced by sexual and gender minorities that goes beyond sexual misconduct.

- Ensuring that violence-specific supports are built upon recognition of the continuum of sexual and other forms of harm, including verbal and sexual harassment and other types of inappropriate behaviours that disproportionately impact sexual and gender minorities. This should also reflect an understanding of the additional and distinct forms of violence and tactics of power and control used to commit violence against sexual and gender minorities

- Promoting a wrap-around service delivery model capable of responding to the distinct and varied mental health and healthcare needs of sexual and gender minorities

Recommendation 7: Support professional development for counsellors within the SMRC and other relevant programs (i.e. health services) for specialized training in supporting sexual and gender minority survivors of sexual violence.

Recommendation 8: Identify and foster relationships with allied service providers and advocates outside of the CAF with specializations in serving sexual and gender minority survivors and communities.

Recommendation 9: Establish some form of independent oversight and accountability body to monitor and report back on the development and implementation of supports for sexual and gender minority survivors and related recommendations.

Recommendation 10: Foster opportunities for meaningful involvement of sexual and gender minority CAF survivors and allied advocates to provide ongoing input on the development and implementation of the Survivor Support Strategy and other CAF initiatives to address sexual misconduct, improve supports, and foster institutional culture change.

Working Together for a Better Future: Support Strategy for Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Members Affected by Sexual Misconduct (the Support Strategy)

Subject Matter Expert (SME) Report and Recommendations (Indigenous Survivor Focused) by Myrna L. McCallum

This short report intends to provide recommendations and priorities which respond to the questions provided in the SME’s Work Plan Proposal dated September 2, 2020, as follows:

- Report (5 pages max.) on specific barriers that Indigenous victims/survivors of sexual violence face to accessing supports as well as best practices in addressing the needs of and providing support to Indigenous victims/survivors, with a particular focus on:

- How to incorporate culturally responsive considerations more effectively in the draft Working Together for a Better Future: Support Strategy for Canadian Armed Forces Members Affected by Sexual Misconduct (the Support Strategy); and

- Priorities, specific to Indigenous victims/survivors, to consider when developing the accompanying implementation plan for the Support Strategy.

The recommendations in this report are informed by the Briefings provided at the Survivor Support Consultation Group Meetings and an independent review of additional documents related to the CAF, Operation Honour, related research reports, and other survivor support strategies. It is noteworthy that despite the Briefing meetings offered to the SMEs, many questions specific to Indigenous survivor experiences remain unanswered by unit leaders and/or their subordinates.

A Note on Indigenous People: Cultural and Intergenerational Trauma

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was launched, the entire country had the opportunity to learn about the horrific abuses and acts of torture experienced by Indigenous children who were forcibly removed from their communities and placed in Indian Residential Schools. When the schools were established across all provinces and territories, the work of forcibly removing children from their families and communities was undertaken by priests, nuns, Indian Agents and the RCMP. Since the recent discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children at Kamloops Indian Residential School, many Canadians are now recognizing the reality, known by Indigenous people for generations, that these institutions were vehicles of genocide, an intention to exterminate Indigenous people.

Following the slow removal of priests and nuns from the residential school system, when the kidnapping of Indigenous child was no longer supported by law and policy, social workers used child welfare legislation to continue the practice of forced removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities. Some were adopted by white families, while others were placed in these schools. To be clear, these institutions were not schools at all, they were damaging and destructive environments where sexual abuse, physical abuse, torture, and neglect was often the norm.

Given this context, Indigenous people are experiencing a cultural and collective trauma rooted in sexual abuse, violence and exploitation which has been passed down from generation to generation. Many, quite reasonably argue, that the disturbing trend of missing and murdered

Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) began at residential schools. The Canadian government and the Church are to blame for the intergenerational traumas Indigenous people and communities continue to experience, which may present as addiction, mental health issues, high suicide rates and offending behaviours including predatory conduct. As Indigenous Nations and communities contend with the devastating effects of the Indian residential school system, many of their members are returning to their teachings, cultures, and spiritual practices as a source of healing, resilience, and recovery.

Barriers and Best Practices

Based upon the information provided at the Briefing meetings, and further to the points highlighted in my presentation on February 11, 2021, I note a significant lack of Indigenous- specific or culturally responsive services for Indigenous survivors of sexual misconduct. The barriers are identified within the various units, separated below:

Chaplaincy Service / Indigenous Advisor to the Chaplain General

A1. The mission statement of the Chaplaincy commits to offer spiritual care and support to all members of the Defence Community while respecting freedom of conscience and the religion of each person. With respect to Indigenous members, the Chaplaincy Service has developed a document titled, “Direction and Guidance on Support for Indigenous Spiritual Practices”.

R1. The SME Recommends that the Chaplaincy amend their mission statement to include the spiritual cultural practices of the diverse Indigenous people of Canada, many of whom do not practice a religion and are returning to their traditional practices as a pathway to healing the intergenerational traumas which originated with the actions of the Church and government.

R2. The SME recommends that the Chaplaincy develop a reconciliation plan to respond to the Calls to Action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report which replaces their current “Direction and Guidance” document.

R3. The SME recommends that the Chaplaincy review the Calls for Justice in the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry Report which clearly identifies the roots of sexual exploitation and current risk factors for Indigenous women and Two Spirit people and formulate an intersectional response to one or more of those Calls which should then be reflected in any Indigenous-specific training or service delivery.

A2. The Chaplaincy has yet to develop a trauma-informed approach training program for front-line caregivers.

R1. The SME recommends that the Chaplaincy define ‘trauma-informed’, and the definition should be consistent with other units within the CAF.

R2. The SME recommends that the Chaplaincy design and develop a training program for all front-line caregivers which aligns with the trauma-informed principles and practices of the Sexual Misconduct Response Centre.

A3. There is one Indigenous Advisor to the Chaplain General, a position which was created to bring Indigenous people into the Chaplaincy which includes building a network with Indigenous spiritual practitioners. The Advisor was appointed in 2016.

R1. The SME recommends that the Indigenous Advisor role to the Chaplain should be driven by developing a response to one or more Calls for Justice (MMIWG) and one or more Calls to Action (TRC) rather than a general intention to ‘bring Indigenous people’ to the Chaplaincy, since that language alone could be quite triggering and create anxieties for Indigenous members.

R2. The SME recommends that several spiritual Elders, representative of the diverse Indigenous Nations, some of whom should be Two Spirit, must be hired to work in tandem with the Indigenous Advisor to reflect the spiritual and healing practices of Indigenous people, as a complement to the “front-line caregiving” work the Chaplaincy currently offers. Tasking the Advisor with the responsibility to build a network with Indigenous spiritual practitioners is too vague and does not demonstrate a meaningful commitment to recruit, retain and respond to the unique cultural and spiritual needs of Indigenous CAF members.

A4. The “Guidance and Directions” document states that the Chaplaincy is committed to supporting and assisting Indigenous CAF members in celebrating their rich spiritual heritage and practising their ancestral ceremonies, and further itemizes sacred Indigenous items/objects/medicines used by Indigenous people.

R1. THE SME recommends that if the “Guidance and Directions” document shall remain – rather than be replaced by a comprehensive document which reflects a response to the Calls to Action and Calls for Justice, this portion should be removed or amended, to include language which reflects the historical harm the Church has caused Indigenous people and the reasonable expectation that Indigenous people may be less likely to access services from the Chaplaincy due to this historical relationship. Furthermore, there is significant healing – and reconciliation – value in the Chaplaincy offering their own apology for the Church’s role in the Indian Residential School system.

R2. The SME recommends that item 11(e) in the “Directions and Guidance” document which lists and commits to purchasing sacred objects/items/medicines be removed as the entire statement is disrespectful and wholly offensive. Purchasing ‘sacred items’ is not in alignment with any Indigenous cultural practice. Furthermore, not all items listed are sacred or ceremonial but instead further entrench existing stereotypes about Indigenous people and their practices.

Health Services Unit

B1. A single annual workshop is offered each year to members of the Health Services Unit which promotes increased understanding of sexual misconduct and how to respond effectively to incidents of sexual misconduct.

R1. The SME recommends that the Health Services Unit develop and deliver training which is specific to working with Indigenous survivors of sexual misconduct which is rooted in cultural humility. The training program should be created in partnership with Indigenous experts and must

reflect the reality that anti-Indigenous biases, Two Spirit discrimination and systemic racism is prevalent in the health care field which has resulted in low quality care for Indigenous people.

Canadian Forces Military Group

C1. SORT investigators receive in-depth and extensive training on how to interact with victims of sexual misconduct and front- line police officers, who are often the first line of response and the first point of contact for victims, only receive basic generic training on how to respond to calls for service. There is no training on trauma-informed approaches.

R1. The SME recommends that SORT investigators receive in-depth training on trauma-informed interview techniques, implicit bias, cultural humility, victim-blaming and sexual assault myths, and stereotypes. This training should also include a significant intersectional component which focuses on the sexual exploitation of Indigenous women, girls, and Two Spirit people.

Military Prosecutions (MP) & Judge Advocate General (JAG)

D1. SMART consists of specialized and trauma-informed trained prosecutors who prosecute sexual misconduct matters, while the JAG is focusing on Victim’s Rights plus working with a Victim Liaison Officer (VLO) to ensure continuity of care, access to supports and stream-lining support services.

R1. The SME recommends that both the MP and the JAG define “trauma-informed”, “trauma- informed prosecutions”, and “trauma-informed care” because there is no clarity on what these terms mean or what, if any, metric is used to measure the success or lack of success in bringing a trauma-informed approach to a prosecution or trial process which are commonly experienced as traumatic and/or triggering experiences for complainants.

R2. The SME recommends that any training offered for special prosecutors and VLOs include content specific to implicit bias, victim-blaming plus rape myths, and the unique risks and stereotypes targeting people of colour, Indigenous women, and Two Spirit people. This training must include a focus on Indigenous trauma stemming from the pervasive sexual abuse and exploitation of Indigenous children which occurred at residential schools.

R3. The SME recommends that any training developed for special prosecutors and VLOs specific to Black, Indigenous or people of colour (BIPOC) must be delivered by BIPOC and Two Spirit subject matter experts.

R4. The SME recommends that if no BIPOC and Two Spirit judges, prosecutors or VLOs exist in the CAF then their recruitment and retention must be prioritized to offer culturally specific support, re- build credibility in the CAF, and deliver a message of commitment to transformation and safety for complainants who have lost confidence in the MP and JAG offices.

D2. Where there is no reasonable likelihood of conviction or prosecuting a matter is not in the public interest, the prosecutor will instruct the investigator to ask the complainant if they would like a meeting with the prosecutor to discuss their decision to not proceed.

R1. The SME recommends that the prosecutor communicate their decision to not proceed directly to the complainant since direct engagement inspires accountability, credibility, trust, and transparency which is essential to trauma-informed applications because it is not unusual for complainants to decline the offer for a meeting if asked due to their trauma, disappointment and/or their own speculations about why their matter did not proceed.

Integrated Conflict and Complaint Management (ICCM)

R1. The SME recommends that the ICCM must create clear processes and protocols which address when specific ADR applications can be applied to sexual misconduct matters which are led by the complainant, require the complainant’s consent, and pose zero physical or reputational risk to the complainant.

R2. The SME recommends that the ICCM establish clear criteria which excludes certain matters from qualifying for an ADR resolution including but not limited to an actual or perceived power imbalance, incidents involving use of force, rape, and matters where the respondent refuses to take any responsibility.

R3. The SME recommends that the ICCM clearly communicate that mediation is never an option for resolving sexual misconduct matters since sexually offensive or harassing behaviours cannot be compared to a conflict or a dispute between two parties.

Defence Aboriginal Advisory Group (DAAG)

F1. The DAAG represents both military and civilian personnel. Their membership is made up of volunteers, guided by local champions at the base/wing/unit level, led by national military and civilian Co-Chairs, and supported by a CAF/DND “Champion”.

R1. The SME recommends that to be effective, highly regarded, and committed sources of advice, all members of the DAAG should be compensated for their advice to the DND/CAF leadership.

R2. The SME recommends that Indigenous Advisors serving on this group must be diverse and reflect the different regions or Nations in Canada.

R3. The SME recommends that all members of the DAAG be required to meet specific qualifications to serve and be provided a mandate once selected. Moreover, there should be clear expectations and communications about how any advice provided will be shared up the chain of command and reflected in reports or projects designed to support Indigenous CAF members.

Army Reserves

G1. Remote and isolated areas within which the Canadian Rangers operate means that access to physical and mental health resources (both CAF and civilian) is limited and Indigenous people make up a large majority of many Canadian Ranger Patrols.

R1. The SME recommends that CAF members who are selected to serve in isolated locations occupied primarily by Indigenous people must receive training which educates them on the experiences of the Indigenous people whose traditional territories they are going to be working in. Any educational or cultural training should be delivered by recognized Indigenous leaders who are representative of the different regions the Rangers are serving in.

G2. Canadian Forces Member Assistance Program requires sexual misconduct victims/survivors prove that sexual trauma is directly linked to CAF service to access services.

R1. The SME recommends that the direct link include the reasonable likelihood that current experiences of sexual trauma including being a witness to an act of sexual misconduct no matter how minor, may aggravate or spontaneously reveal historical and unrelated experiences of sexual misconduct which could serve as a catalyst for new and significant adverse mental health impacts – all of which should meet the test for eligibility or an established “direct link”.

G3. Part-time and remote nature of reserve work are barriers to both members receiving adequate training about sexual misconduct and members who are victims/survivors accessing services and support, especially for those members under 18 who do not have a parent or guardian’s consent to access support.

R1. The SME recommends that online training should be developed and accessible to all members who are working in remote locations which reflect some Indigenous historical context informed by the TRC and the MMIWG Inquiry. For members under the age of 18, access to training and general support services or information should be created in collaboration with civilian youth agencies who are experts in sexual exploitation or abuse as experienced by youth.

G4. It is unknown how many reservists leave the force because of sexual misconduct.

R1. The SME recommends that the CAF create and maintain surveys, statistical reports or other data collections which reflect the reasons why self-identifying Indigenous members decide to leave the CAF. One of the possible reasons available should cite experiences of sexual harassment, other forms of sexual misconduct and a lack of support or response to sexual misconduct.

Recommendation on Identifying Priorities

The recommendations provided should equally be received as high priority items. However, if the SME is limited to selecting one, two or three priorities which could be emphasized in the Support Strategy then they are identified below.

- It is a priority that the development and delivery of Indigenous-specific content to those who work to serve Indigenous survivors and complainants must be delivered by Indigenous experts and include an emphasis on the following:

- Trauma-informed engagement strategies

- Cultural humility

- Implicit bias awareness and safeguard strategies

- Stereotypes, myth, and stigmas targeting BIPOC and Two Spirit survivors of sexual misconduct; and

- The TRC Calls to Action and the MMIWG Calls for Justice.

- It is a priority that the CAF, namely the Chaplaincy, the JAG and the MP Office recruit and retain self-identifying Indigenous and Two Spirit judges, lawyers, prosecutors, VLOs, Elders and cultural leaders to reflect the diversity among Indigenous people and to communicate a message of transformation, commitment to representation (race, culture, gender identity and values), and to inspire credibility and trust where none currently exists.

- It is a priority that any departments, offices, or leaders developing education, training, implementation, or other strategies to support Indigenous members who experience sexual misconduct in the CAF, first address the realities and failures set out by Anna McAlpine in her thesis, An Intersectional Analysis of Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces: Indigenous Servicewomen, dated April 9, 2021.

Myrna L. McCallum

June 2, 2021

Final Report to the Survivor Support Consultation Group

by Rick Goodwin, MSM, MSW, RSW Subject Matter Expert

May 26, 2021

Preamble:

The following are my final recommendations to the Survivor Support Consultation Group (SSCG). I was brought on as a Subject Matter Expert (SME) given my role as the Founder and Clinical Director of Men & Healing: Psychotherapy for Men – one of Canada’s few mental health clinics that focuses on men’s mental health. As well, over the past 20+ years, I have served as a trainer on clinical and first-responder issues concerning male sexual trauma and recovery in communities across Canada, a variety of international efforts, and specific initiatives within all branches of the U.S. military.

Before outlining my recommendations, it is important to highlight the following limitations of the report:

- This report requires the reader to have a knowledge base of male sexual trauma – a topic that has been seemingly historically unaddressed in CAF. Male sexual victimization is “common, underreported, under-recognized, and undertreated” (Holmes and Slap, 1998). A summary on this topic is attached as an Appendix. This summary was created from my presentation to the SSCG on February 18, 2021 and should be considered required reading.

- The consultation process was truncated. There was insufficient time to gather needed information from all aspects of DND services to fully understand and analyze the mandate set before the SSCG. In almost all cases, there was only one presentation per area of service, which was to serve as both the backgrounder as well as a place for dialogue to delve deeper into analyzing service protocol and limitations.

- The Consultation SMEs were relatively under-resourced for this activity. Given the relative complexity of DND structure and services, the SMEs would have benefitted from a dedicated information broker to help guide the information-seeking process. More time allotted for the review process would have been beneficial, as major aspects of CAF response was insufficiently covered. See Part III as an example of this insufficiency.

- Key language and terminology were not defined in this process. From “trauma-informed” to “gender–based violence,” the lack of clear language distracted from the work of the SSCG. At times, this absence was counter-productive to the work of the group as a whole, as competing definitions could be interpreted at cross-purposes. Without such clarification, it is unclear how some of the recommendations discussed in the SSCG could be clearly understood or acted upon.

- The focus of SSCG discussion vacillated at times from its mandated purpose of “Resources and Supports for Victims/Survivors of Sexual Misconduct” to creating resources for all members who have experienced trauma. The distinction is both necessary (i.e., as a liability which led to the FSA) and arbitrary (i.e., as it pertains to support services, including Health Services). It needs to be stated that the term “sexual misconduct”, or the affiliated term “military sexual trauma” has little utility in terms of psychotherapeutic engagement. As my expertise focuses on issues of support and treatment, I will be emphasizing the latter.

Trauma is a broad term to describe the psychological injury of harm to an individual. There are many categories of trauma to be considered: developmental trauma, shock trauma, relational trauma, community-based traumatic stress, generational/historic trauma, cultural trauma, traumatic embodiment, secondary trauma, vicarious trauma, and ecological grief are all examples. Military sexual misconduct can be identified in many of these subsets.

Just like the Canadian population, it should be assumed that members may carry multiple subsets of trauma (probably more so – See Appendix). To put it another way, “sexual misconduct” represents only a limited portion of what can be defined as the “trauma load” of DND personnel. For a healthy workforce, to ensure “full deployment”, and as a necessary secondary prevention strategy to eliminate sexual misconduct from DND, all aspects of trauma need to be understood and addressed.

This report consists of three sections:

- Considerations for Designing Supports for Male-Identified Survivors

- Addressing Barriers to Help-Seeking and Reporting for Male-Identified Survivors

- Health Services & Male-Identified Survivors

I will utilize the term “survivor” as a preferred term to describe those members who have experienced abuse, assault or other traumatic experiences. However, the word “victim” may at times be more appropriate to the context of conversation. It should be recognized that these terms may not reflect the subjective experience or the language choice to those members so affected.

I. Considerations for Designing Sup$ports for Male-Identified Survivors

To address the institutional barriers to trauma care and engagement of male members will require a multi-pronged effort. A courageous effort to re-think much of what is currently being offered is required to shift the perceived dominant culture of trauma-avoidance and trauma- denial within DND. A broader, more encompassing notion of both the subject of trauma is required in order to engage effectively with those with lived experience. This will benefit all members of the military, regardless of their gender or other identifiers.

Six core recommendations are presented:

1. Expand the area of concern from “sexual misconduct” to all forms of trauma for service members.

A healthy workforce suggests that all health issues be addressed. While there are issues of immediacy, legality, potential criminality and workplace safety when the trauma focus is on sexual misconduct, this narrower lens suggests that the larger, pre-existing proportion of membership that carries unaddressed trauma will not be well attended to.

This narrowed focus of sexual misconduct may address workplace safety, but it does not necessarily address worker well-being. The partitioning of trauma response would be inconceivable in other aspects of health care. For example, suggesting that a service member’s heart disease is attributed (or not) to experiences in the career of said service member would be preposterous to consider. Yet, in mental health care, the organizational response mimics hierarchy in its assessment of who warrants support and engagement. The focused attention to “sexual misconduct” (much like operational stress injuries), seemingly minimizes other traumas within membership, akin to seeing these other traumas as a “pre-existing condition” – a term much used in the insurance industry to deny coverage.