Getting to Work: Accessible Employment in Canada – Report from the Chief Accessibility Officer, 2024

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- Message from the Chief Accessibility Officer

- Report summary

- Introduction

- Progress under the Accessible Canada Act: employment

- Progress towards a barrier-free Canada

- Systemic issues in Canada

- Emerging issues

- Beyond the Accessible Canada Act

- Chief Accessibility Officer Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Glossary

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- AC

- Accessibility Commissioner

- ACA

- Accessible Canada Act

- ACD

- Accessible Canada Directorate

- ACR

- Accessible Canada Regulations

- ASC

- Accessibility Standards Canada

- AP

- Accessibility Plan (required under the Accessible Canada Regulation)

- CAO

- Chief Accessibility Officer

- CHRC

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- CRTC

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- CTA

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FRE

- Federally Regulated Entity

- PR

- Progress Report (required under the Accessible Canada Regulations)

- PwD

- Person with a Disability

- PwoD

- Person without a Disability

Message from the Chief Accessibility Officer

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Message from the Chief Accessibility Officer (no audio)

English content

Far too many people in Canada are highly qualified and eager to work, but they can't. They are prevented from getting the chance to do so because they live with disabilities. The systems we live with are hesitant to adapt.

It's frustrating. We know the reasons behind this and the intent to change is growing. But change needs to happen faster or our progress towards a barrier-free Canada will be stalled. We won't get there unless employment opportunities for people with disabilities increase and accessibility becomes a core business value.

Over the past two years, I've met with hundreds of professionals, disability advocates, and corporations. Among those professionals were people with sight loss, who were Deaf, neurodivergent, or who had disabilities related to mobility. This report features several of these professionals: Anu Pala, a keynote speaker, consultant, coach, and podcaster who lives with sight loss; Dr. Harinder Dhaliwal, a neurologist and wheelchair user; and Lorin MacDonald, a Deaf human rights lawyer and law professor at Toronto Metropolitan University.

If it surprises you that people with disabilities have followed these career paths, that's part of the problem. It still surprises far too many people. Ableist attitudes still prevail. Assumptions are made about what kind of work people with disabilities can do. The truth is, with the right accommodations and inclusive work cultures, the possibilities are endless. People with disabilities can be baristas, hospitality specialists, maintenance professionals, writers, curators, scientists, teachers, and they can be your co-worker. They belong at all levels of organisations, from front line staff to the C-Suite. But barriers persist, even now, five years after the Accessible Canada Act (ACA) was first passed. We still have a lot of work to do in raising awareness about the ACA and in dispelling myths about disability. We must act faster to improve recruitment, hiring, and retention.

The good news is that many people with disabilities are working. But I've said many times that far too much potential is being lost due to barriers to employment. We know that more than 850,000 Canadians with disabilities are ready and able to work but barriers prevent them from doing so. I know a job seeker who speaks 3 languages and has a business degree and a Human Resources certificate. They should be at work helping a company become a more accessible employer. I know a writer with a literature degree who should be adding value in a communications role. But they are overlooked time and again.

Hiring people with disabilities is the right thing to do. The business case for it is irrefutable. So, what's stopping progress? Many hiring systems, including those of government, are too rigid. There are structures in place that prevent accommodations from being made. Beyond this, employers lack the knowledge they need about how to attract and retain disabled talent. This lack of knowledge is part and parcel of a culture that is quick to medicalize disability instead of thinking about it more broadly. It is also a culture that is quick to deny and distrust, where biases can all too easily hold sway. Where minds can remain closed. Collectively, employers are too quick to make excuses, to write accessibility off as too expensive and leave it out of their budgets. We urgently need goalposts: voluntary standards to help guide employers and regulations requiring employers to make changes.

There is no shortage of talent. There are excellent models in Canada and in other countries to look to as examples of how to do it. Organizations like the Presidents Group, Valuable 500, and Disability:IN, along with their members, are leading the way. Every year, the Untapped Workplace Inclusion Awards, held by the Open Door Group, recognizes examples of workforce inclusion. Companies and organisations are placing greater emphasis on doing the work.

Attracting labour and top talent has never been more challenging. But doing so is critical if Canada is going to remain competitive in the global marketplace. We can solve the problem of excluding skilled people. We just have to move from words to actions.

We need government programs to fund accommodations and a revamp of disability supports. We need to broaden our definition of "reasonable" in the context of accommodations. Not all job seekers or employers are the same, so we need targeted and varied supports. Above all, we need to have higher expectations. We need to recognize that PwDs are vastly, diversely talented and stop limiting our assumptions about what they are capable of and what kind of work they can do.

We need to push for firm commitments and action. Everyone deserves the chance to contribute to their fullest potential. We need to get to work.

Report summary

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Report summary (no audio)

English content

The Accessible Canada Act (ACA) came into effect in 2019. It aims to make Canada barrier-free by 2040. It will do this by making federally regulated entities (FREs) responsible for the full participation of persons with disabilities (PwDs) in society. Five years in, are we moving in the right direction? To start answering that question, my team and I took a closer look at the state of employment for people with disabilities in Canada. What is happening around employment reflects a lot of what is happening in other priority areas. This report also comments on the overall state of progress under the ACA.

In general, employment is not more accessible to PwDs since the ACA came into force.

National surveys show that, despite minor improvements, many equity gaps remain. For example, PwDs are still less likely to be employed, to have a full-time job, and to have an income higher than $80,000.

To prepare this report, my team and I analyzed employment information in the accessibility plans (APs) and progress reports (PRs) of 117 FREs. We found that most FREs identify a few barriers, most often related to PwDs' recruitment, accommodations, and training. Half of the initiatives planned to address these barriers were completed or routine practice after a year. But from the perspective of PwDs, it is generally unclear if these initiatives are effective.

We also met with diverse organizations active in disability inclusion. They helped us identify examples of promising initiatives to make employment more accessible. These discussions helped uncover some systemic issues that create barriers for PwDs. These include: job requirements that make it difficult to get a first job; rules that may cause PwDs to lose their disability benefits when they get a job; and lengthy processes that delay responses to accommodation requests.

Overall progress under the ACA is slow and uneven.

The only current requirements for FREs under the ACA are to prepare and publish APs and PRs, in consultation with PwDs, and to have a feedback process. Compliance is generally high among public sector FREs but low among private FREs. Beyond these requirements there is a lack of specific directives, which means the way FREs report on barrier identification, removal, and prevention is inconsistent.

National standards can be used to create new regulations, which come with specific legal requirements. So far, Canada has 4 finalized accessibility standards that cover 2 ACA priority areas (built environment and information and communication technologies). But federal standards do not necessarily align with those of provincial, territorial, and First Nations' governments. Delays in making regulations limits more specific actions required of FREs. It also limits people's ability to make complaints, and the ability to hold FREs accountable. More efforts are needed to create regulations faster and coordinate accessibility initiatives across levels of government to reach the goal of a barrier-free Canada.

Canada is taking steps in the right direction, but widespread lack of awareness about the ACA is slowing our progress in becoming barrier-free, as is lack of reliable accessibility data.

The federal government published a Disability Inclusion Action Plan in 2022, but its Performance Indicator Framework for Accessibility Data is not fully developed. Meanwhile, few Canadians are aware of the ACA. Disability remains the basis for half of human rights complaints processed by the Canadian Human Rights Commission. And latest evaluations by the United Nations show that Canada still has significant issues in disability inclusion, in employment and other areas. Delays in analyzing meaningful data limits the capacity to assess the results of investments made in disability inclusion, and to course correct before 2040.

Will Canada be barrier-free by 2040?

There is a lot of work happening in Canada to advance accessibility in employment and in other ACA priority areas. But significant issues are persisting and slowing progress toward our barrier-free goal. To tackle them, I recommend:

- creating a centralized centre of excellence to raise awareness, provide supports, and help build capacity for FREs and the public

- updating the existing ACA regulations to help standardize FRE accessibility plans and progress reports

- aligning accessibility-related definitions in all federal laws

- developing diverse national-level supports, to improve disability inclusion

Introduction

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Introduction (no audio)

English content

"Unconscious bias creates barriers for people with disabilities in all aspects of life, and it is often difficult for people without disabilities to understand. For example, I'm an artist and actor. I am blind, and when I go to the theatre I am often met with surprise, curiosity, and even skepticism. Though unintended, these small moments reflect a lack of awareness and unconscious bias that overlooks the layers of theatre that transcend vision-storytelling, dialogue, music, soundscapes, and the collective energy that fills the space. People with disabilities encounter assumptions like these in all sorts of workplaces. Real progress won't happen until this mindset changes. In theatre, as in any environment, accessibility features like audio description, tactile tours, and seating accommodations, elevate everyone's experience. So much more is possible. So much more is possible." - Amy Amantea, Actor, Artist, Accessibility Consultant

There's no doubt that accessibility makes sense. It is both the right thing to do and the smart thing to do. We all benefit most from accessibility when people with disabilities get the chance to work. Many of us, including those in the workforce, will experience a condition that affects our mental, cognitive, and/or physical functions at some point in our lives. Economically, it makes sense to tap into PwDs, to seek their contributions both as taxpayers and as employees, because organizations with diverse workforces are more productive and innovative. Moreover, since more than 1 in 4 Canadians are PwDs, they represent a large market for businesses developing and offering adaptive products and services. Accessibility, including in employment, is simply everyone's business.

This year, my report examines the progress being made on employment, which is one of the 7 priority areas for action under the ACA. Progress on employment reflects progress overall, because when organizations get this right, and are inclusive of PwDs, they benefit from the perspectives these employees bring and are more likely to prevent barriers in other areas being built in the first place. The lack of PwDs' perspective in the workforce costs us all. This is underscored by the fact that, in consultations with Canadians when developing the ACA, 39% of them said that the federal government should make employment a top priority in tackling barriers to disability inclusion. This includes fair hiring practices, access to a first job, workplace adjustments, promotion into leadership positions, and more. Access to meaningful employment is part of living with dignity and purpose and contributes to overall quality of life.

I have observed both promising efforts and persistent gaps in making workplaces more inclusive. While there is some accessibility data in Canada, it is clear to me that the quality and limited availability of existing data make it hard to measure progress. It can be challenging to determine if a data source can be trusted, as it may lack transparency about how it was collected or be subject to conflicts of interest. All data have some kind of limitation, whether that be missing information or not being made publicly available. To offset some of these issues, my team and I looked at diverse sources for data and information. We reviewed the work of other federal organisations with responsibilities under the ACA. We also continued to engage with PwDs, their allies, federally regulated entities (FREs), and other stakeholders involved in disability inclusion efforts. In addition, we reviewed public reports and resources, including national surveys as well as FREs' accessibility plans (APs) and progress reports (PRs).

Our research

Review of accessibility plan and progress report content about employment

My team and I have read dozens of APs and PRs to try to define a meaningful way to measure their work under the ACA. These exploratory readings helped us identify a set of indicators that FREs report using to measure progress in the identification, removal, and prevention of barriers in employment. Within this set, there are indicators to measure progress in certain areas that I have previously recommended for action (i.e., mandatory training, data, and dedicated funding). We randomly sampled 117 FREs from a group of those who had published both an accessibility plan (AP) and a progress report (PR) by June 2024. These included 55 public FREs and 62 large private FREs. This review is important to determine overall trends but is limited to what FREs chose to report.

Stakeholder interviews about accessible employment

My team and I held 45 targeted interviews to systematically collect information specific to accessible employment. We met a variety of organisations, including disability service providers, post-secondary institutions, international experts, FREs in the public and private sectors, provincial and territorial government departments, disability experts/advocates, and representatives from employees with disabilities networks across the federal public service. During these meetings, we discussed attitudes, experiences, and perspectives of barriers in employment. My team pulled out common messages from these discussions about barriers, initiatives to address barriers, and systemic and emerging issues. These interviews helped us gather information that may not have been reported in FREs' APs and PRs, and validated what we were seeing in them.

The following sections summarize Canada's progress towards a barrier-free status, with a focus on employment, and provide comment on the contributions of the ACA to that progress. Based on these observations, the report identifies key systemic issues in employment and beyond, with examples of promising initiatives. The report also discusses a few accessibility issues that emerged in 2023, as well as accessibility issues beyond the ACA and beyond Canada. Finally, I make a few recommendations to help keep us on track to make Canada barrier-free by 2040.

Progress under the Accessible Canada Act: employment

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Progress under the Accessible Canada Act: employment (no audio)

English content

" Accessibility is only the entry point - it is not the end goal. We must meaningfully include people with disabilities at all levels of impact in the workplace. In all sectors. In all aspects of society, so we have an opportunity to feel a sense of belonging, and feel valued, celebrated, recognized, and respected. Disability inclusion recognizes that if the world's population includes us, our organizations and institutions must do the same. " - Prasanna Ranganathan, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging (DEIB) Advisor and Consultant

The Accessible Canada Act (ACA) makes it the responsibility of FREs to identify, remove and prevent barriers for persons with disabilities (PwDs). In this section, I look at the current impact of the ACA on advancing disability inclusion, particularly in employment.

Awareness of ACA-related matters

Progress under the ACA is slowed by very low awareness of the Act in Canada. The Accessible Canada Directorate (ACD) at Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) has been monitoring awareness of disabilities in general, and of the Act more specifically. According to the results of public opinion surveys of Canadians that they conducted in 2019 and in 2022:

- in 2019, 72% of people without disabilities (PwoDs) surveyed reported understanding what a disability is, though only 47% said they understood well the types of barriers PwDs may face

- in 2019, only 15% of PwoDs surveyed were aware of the ACA, and in 2022 only 21% were aware

- very few PwoDs were aware that employment was a priority area under the Act (4% in 2019 and 3% in 2022)

In his 2023 annual report, the Accessibility Commissioner suggested that low awareness of the ACA may have contributed to the low level of compliance with obligations under the Act that he observed. Specifically, he noted that compliance with the Accessible Canada Regulations (ACRs) among large private FREs was "disappointingly low," as only 22% of large FREs in the private sector had notified him of their APs' publication by the prescribed deadline of June 1, 2023 (although that did increase to 40% by March 31, 2024).

My office and I heard from stakeholders in interviews that many FREs want to hire PwDs. They want to be inclusive. But they don't know how to identify, prevent, and remove barriers. Smaller FREs tend to have fewer resources and may struggle more to find guidance to comply with ACRs. FREs expect this challenge will only increase as more ACA regulations roll out. We also heard that awareness of the ACA definition of disabilities varies across organisations. This is especially true for non-visible, temporary, and episodic disabilities.

The ACA has been in effect for more than 5 years. If FREs are not aware of their responsibilities under this law, and Canadians are not familiar with what they can expect and demand, this will significantly slow our progress towards a barrier-free Canada. We must run communications campaigns now to raise not just awareness, but understanding. This will prevent bigger problems as more complex regulations come in the future.

Some FREs are increasing their efforts to promote awareness around non-visible disabilities

For example, BNP Paribas in Canada bank partners with several community-based organisations (like Autisme Sans Limites and Auticon) on their Neurodiversity in Employment program. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission has started mandatory accessibility-specific training in 2023, and hosted awareness sessions on autism, bipolar disorder, neurodiversity, and Deaf culture.

Legal obligations and accountabilities

"Accessibility is the key that unlocks potential in both employees with disabilities and organizations, to the benefit of everyone with whom they interact. Regulatory requirements around accessibility serve as this key, as they create standardized expectations that help organizations recognize and unlock this mutual benefit rather than viewing accessibility as optional."

- Lorin MacDonald, Founder & Principal, HearVue Inc., Course Creator and Instructor, Disability Law, Lincoln Alexander School of Law, Toronto Metropolitan University

Awareness, compassion, empathy and allyship, guidelines, and voluntary standards are important to achieve disability inclusion. But they are not enough. If they were, we wouldn't need the ACA. Significant progress will not speed up without legal obligations to act.

In the ACA context, regulations are essential but there are too few to compel action.

Regulations specify what FREs must do to remove and prevent barriers. More regulations would also clarify how FREs will be legally compliant and provide the basis on which PwDs can make a complaint under the ACA. This allows federal regulators to apply warnings, fines, or other consequences, to keep FREs accountable.

There are currently no employment-specific accessibility regulations at the federal level. For example, there is no regulation regarding timelines to implement accommodations, or safeguards to ensure fair performance assessment of employees with disabilities. This means that FREs are figuring it out on their own, or not at all. The absence of regulations increases the risk of inconsistent and inadequate approaches to disability inclusion in workplaces across Canada and makes it difficult to measure progress.

Under existing regulations, FREs must only include headings in their APs and PRs for ACA areas. There are no rules on what information to include or what action a FRE must take in priority areas, like employment. This lack of precision has caused inconsistency in the content and quality of APs and PRs.

Not all FREs realize they must follow ACA regulations enforced by different federal authorities.

FREs in the transportation and broadcasting and telecommunications sectors have to comply with multiple regulations. The Accessibility Commissioner (AC) enforces the Accessible Canada Regulations (ACRs) for all ACA priority areas for most organizations. But when it comes to FREs in the federal transportation and broadcasting and telecommunications sectors, the AC is only responsible for enforcing compliance in certain areas, such as employment. The Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA) and Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) enforce accessibility regulations under the Act for the latter two sectors, except in areas that the AC enforces compliance. This means that FREs in these sectors must respond to separate federal authorities when complying with ACA obligations. This split of enforcement responsibilities is creating confusion among FREs and the public and may be contributing to lower rates of compliance.

A standard on accessible employment may lead to a new regulation.

I am pleased to see that Accessibility Standards Canada (ASC) is developing an accessibility standard for employment. The standard will provide requirements and recommendations on how to improve accessibility in all aspects of employment. The full employment standard is expected to be published in 2025. Standards are voluntary but could become the basis for new regulations in employment under the ACA. All FREs should consult these standards and act now to meet and exceed them.

Federally regulated entity actions to address employment barriers

“Barriers to employment exist for people with disabilities because recruiting systems were designed by people who didn't experience barriers themselves. By understanding the reasons behind and methods for inclusive hiring we can dismantle the systemic barriers. That's why training and awareness are essential.”

- Susan Bains, Accessibility Advocate & Educator

Accessibility plans (APs) and progress reports (PRs) provide public data on FREs' initiatives to address barriers. These publications are an important source of information to assess FREs' contributions to the goal of making Canada barrier-free.

Several organisations, within and beyond the federal government, including my office, have reviewed the contents of APs and PRs. We all found that the contents varied a lot in length, clarity, level of detail, and meaningfulness. This makes it challenging to compare FREs and to assess them as a group. We also found it difficult to compare progress from an AP to a PR of any given FRE, as formats didn't always match, and information wasn't consistent from one document to another. This makes it incredibly difficult to assess progress. If we can't assess how well FREs identify, remove, and prevent barriers, then we can't tell if the ACA is working.

With these limitations in mind, preliminary findings from my team's research offer a general idea of progress being reported in the area of employment, from FREs' APs and PRs.

There is some progress in identifying barriers, but there are gaps in information and how it may be collected:

- among the 117 FREs reviewed, 109 identified at least 1 barrier, and 4 barriers on average were identified by all sampled FREs, relating to employment

- barriers identified in the APs and PRs cover several employment stages, from hiring to retirement or other permanent separation, but most relate to recruitment, accommodation/well-being, and career development/promotion

- only 14.4% of reported barriers were identified from feedback received or through consultation, suggesting that many FREs may not rely on PwDs' input to identify barriers

There are initiatives underway to remove and prevent barriers. Key supports for their success (accountability and progress measures, training, dedicated funding) require more attention:

- 50.9% of the initiatives had been completed or had become routine practice (some of these initiatives were implemented between the AP publication and the PR, reflecting recent progress, but some initiatives existed before the AP publication, which shows that some FREs have been working on accessibility issues for a long time, in some cases before the federal government issued the ACRs)

- among initiatives to address barriers, 37.7% had a timeline for implementation, which is important to help ensure accountability and follow-up

- only 11.3% of initiatives had identified a responsible lead, increasing the risk that no one will be held accountable if action plans are not adequately completed or implemented

- only 8.7% of initiatives were drawn from feedback or consultations, so it is unclear if implemented solutions met PwDs' needs

- less than 4.5% of initiatives involved mandatory training, which limits opportunities to raise awareness and help organizations understand their responsibilities under the ACA

- only 1.2% of initiatives mentioned dedicated funding, which may affect the quality and sustainability of efforts to remove barriers

- only 12.8% of FREs reported an initiative that had a measure to assess progress

Mandatory training can help strengthen leadership

Bell Canada Enterprises (BCE) now has two kinds of mandatory training for their employees. BCE representatives shared with me that their People Leaders have been completing mandatory mental health training through Queen's University's Certified Workplace Mental Health Leadership program since 2015. This program was co-developed by both organisations. In May of 2023, BCE implemented additional accessibility training that is mandatory for all BCE employees, including leadership.

Dedicated resources for accessibility are a must

I was pleased to see that the Office of Public Service Accessibility (OPSA) received renewed funding for two more years, in the 2024 federal budget. OPSA is an organisation that provides support and resources to the federal public service to help them identify, remove, and prevent barriers for employees with disabilities. Having a centralized organisation like OPSA, with dedicated funding, helps ensure accessibility continues to be a priority in the federal public service.

Accommodations are key to creating inclusive workplaces

I've learned about examples that show some organizations recognize the importance of workplace accommodations and the need to invest in them long term. Fiji Airways has created a centralised accessibility and accommodations fund. The Department of Canadian Heritage has a one-stop-shop for return to workplace accommodations (the Bob Fern Centre), with a centralized accommodation fund.

"As a South Asian woman with a non-apparent disability, my employment experience has been deeply influenced by both visible and invisible workplace barriers. For me, accessibility is about fostering workplaces that accommodate mental health needs, support open dialogue, and embrace diverse perspectives. These steps are crucial for creating an environment where individuals with non-apparent disabilities can fully engage and contribute their talents without fear of stigma or misunderstanding."

- Lizna Husnani-Puchta, Senior Manager, Equity, Diversity & Inclusion and Accessibility Lead Communications, Public Affairs & EDI, Coast Capital

What gets measured can be managed more effectively

The Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency set an objective to exceed their workforce availability representation by at least 13% for Indigenous employees, racialized/Black employees and PwDs and they ended up exceeding this benchmark by 25%. At the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the number of Talent Management Plans (TMPs) for PwDs increased from 14 to 35 between 2021 and 2022. TMPs are a tool government uses to help develop employees with potential.

I've learned through engagement over the past two years that accessibility plans and progress reports only tell part of the story for FREs. Here are some of the common themes I've observed coming out of these discussions:

Intersection of ACA areas

We heard that employment cannot be addressed in isolation from other ACA priority areas. For example, some PwDs can't work if there are no accessible transportation options to reach a place of employment, and no virtual work option. Job postings or the application process (information and communication technologies) may also be inaccessible, making it difficult for PwDs to apply for jobs. In other instances, the job requirements may list criteria that are not essential to the job, but that might pose challenges for some PwDs. We also heard that assumptions are still made by organisations about the cost or difficulty of providing accommodations. For instance, it is assumed that upgrades to the built environment will be expensive or that procuring accessible technology will be challenging. Finally, stigma and misconceptions about what PwDs can do still exist in the workforce.

Education

Education is a key part of entering the workforce, with post-secondary education increasingly becoming a requirement for entry level positions, whether that is university, college, or apprenticeships. We heard during our interviews that this step towards employment is not an easy one for many PwDs. We heard from universities that students with disabilities face challenges such as inaccessible built environments in aging campus buildings, lack of accessible technology, and stigma. We also heard that university students with disabilities often don't get the same opportunities to build work experience through internships or work-study programs due to a variety of barriers. They also sometimes need help navigating the job market, particularly when deciding whether to disclose their disabilities and risk discrimination.

Impact of income supports and medical benefits restrictions on employment

We heard during interviews with service providers that some PwDs hesitate to enter the workforce because of the potential impacts on their existing financial supports or disability benefits. For some PwDs, income supports and/or medical benefits from government are a necessity. PwDs in receipt of these supports face barriers to employment due to the structure and rules around them. For example, restrictions around the maximum number of hours of work or maximum earnings allowed before triggering reductions (claw backs) or full loss of all supports/benefits can become a disincentive to seek employment. While it is understood that these programs must have requirements and rules to ensure they are of maximum benefit to those who rely on them, they must also be structured to help enable entry into the workforce rather than act as a barrier. It is important to bear in mind that many people with disabilities have extraordinary expenses for adaptive or specialized equipment, transportation, medical or personal supports, and more.

Accommodations continue to be a challenge in many Canadian workplaces

In the context of disability inclusion, accommodations are adjustments that aim to facilitate or improve PwDs' participation. However, many employers still demand medical justifications that are unnecessary or that they may not have expertise to interpret before they'll consider providing accommodations. Many fail to understand that the ACA is based on the premise that it is the barriers in society (e.g., ableist attitudes, discrimination, the built environment) that prevent the inclusion of PwDs, not the disabilities. Many are also unaware that the ACA puts the onus directly on employers to remove barriers, not on employees with disabilities. Such practices and misconceptions among employers perpetuate historical discrimination against PwDs and create unsafe spaces that slow down progress towards a barrier-free Canada.

Sometimes, PwDs need to be provided with adjustments, such as to their workspace or work equipment, to allow them to do their job successfully. But some employers claim that accommodations are too costly to provide. This mindset creates and perpetuates barriers. Accommodations can have direct benefits, like better employee retention, increased productivity, and reduction in employee sick time and compensation costs. They can even have indirect benefits, like improved morale within the organization, building a reputation as an equitable employer, and attracting more talent.

"People tend to make assumptions about what I can do or can't because they aren't familiar with speech impairments. In reality, I can easily be accommodated in the workforce with adjustments that have no costs. For example, I can be delegated tasks for which I can communicate via email or text instead of by phone or in virtual meetings. I can engage using the chat or messaging feature to contribute to discussions with ease."

- Ekamjit Ghuman, Bachelor of Business Administration graduate, job seeker

The benefits of accommodations outweigh the costs

A 2018 study by the Mental Health Commission of Canada found that providing mental health accommodations to employees resulted in economic benefits worth 2 to 7 times the cost of accommodating the worker. In the United States, the Job Accommodation Network (JAN) which is funded by the Department of Labor, supports employers with job accommodations and collects related information. Between 2019 and 2023 JAN collected information related to accommodation costs from over 1,000 employers that used their services. They found that 56% of accommodations reported cost nothing to implement. When accommodations did cost money, 37% were one time only, with a median cost of $300 USD. Only 7% of accommodations resulted in ongoing costs for employers with a median annual cost of $1,925 USD.

Retention

We heard from stakeholders across sectors that retention of employees with disabilities needs more attention. It is not enough to hire employees with disabilities. There must be a culture and resources in place to retain and promote PwDs, and this must extend to employees who may acquire disabilities during their career. If an organisation is unable to retain PwDs after hiring, this can indicate a problem with the culture. When PwDs choose to leave because an employer is not inclusive, that employer's reputation may suffer, and become less attractive for job seekers and clients alike.

Understanding why PwDs leave their jobs

Justice Canada shared with me that they are trying to determine the reasons why employees with disabilities leave their workplace. To help do this, they give employees options in their departure form to self-identify as a PwD and to complete an anonymous exit interview with Justice Canada's Ombudsperson's office. This can help identify and better understand the reasons why the employee is leaving the organisation, including possible barriers to inclusion. This kind of initiative creates opportunities to identify new or persisting barriers that need to be addressed .

FRE size and structure can influence progress

My team and I also heard that FREs' ability to address barriers varies greatly across organisations. While large corporations may have a whole team dedicated to accessibility, small and medium organisations may have a single person or no dedicated resource at all. According to a 2023 study by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, small and medium-sized organisations make up the largest percentage of companies in Canada. They have enormous potential to make change for disability inclusion. At the same time, we've heard that implementing change in larger organisations can be challenging due to their size and complexity. Smaller organisations can be more nimble. They often have to be. It's important to take these differences into consideration to ensure the best supports are designed for each type of employer. There is no one size fits all solution.

Figure 1 - text description

This illustration displays key findings from a research project by the Office of the Chief Accessibility Officer. It is based on the review of 117 federally regulated entities (FREs) that published information under a heading about employment, in their accessibility plan or progress report. Altogether, these 117 FREs reported 515 barriers related to employment, within their scope of activities.

The left side of the illustration shows 4 right arrows lined up and representing 4 stages of the employment cycle, with the breakdown percentage of corresponding barriers. Among the 515 employment barriers: 35.1% were about recruitment, hiring or onboarding; 33.6% were about accommodations or wellbeing; 26.0% were about career development and promotion; and 2.1% were about retention or separation.

The right side of the illustration shows a circle divided into a small piece and a large piece that represent the percentages of barriers that FREs had addressed or not addressed. Among the 515 barriers: 78.9% were linked to an initiative to remove or prevent them and 21.1% were not linked with such an initiative.

Other federal government commitments

"Accessibility means everybody having equal opportunity to be a part of their community. I like working with a kind and patient team because I get to be my best self. I really enjoy the regular customers. They are very friendly and I feel appreciated."

- Krista Milne, Hostess

Accessibility is important so that people aren't isolated. People can do the same activities as anybody else, just a bit differently. I love my job, where I've been for 10 years, because I get to be outdoors and active. The people I work with are great, and I feel like a valued member of the team.''

- Weston Bosma, City of Surrey Cemetery Services

Canada has had a Disability Inclusion Action Plan (DIAP) since 2022. This plan outlines the federal government's approach to disability inclusion. One of its objectives is to achieve the ACA goal of a barrier-free Canada by 2040. Building on past achievements and existing programs, it identifies key areas requiring investments to drive change in financial security, employment, accessible and inclusive communities, and a modern approach to disability. The plan clearly explains the importance of employment in disability inclusion. According to the DIAP, PwDs still experience serious equity gaps in employment. The Plan is supported by dedicated funding, but it is unclear how its outcomes will be evaluated.

Canada recently launched an Employment Strategy for Canadians with Disabilities (July 2024). This strategy flows from the DIAP's Employment pillar. The objective of the Strategy is to close the equity gap between PwDs and PwoDs by 2040, by helping PwDs, people and organizations that support disability inclusion in employment, and employers. The strategy is supported by millions in dedicated funds and several agreements with provinces to share accessibility costs. However, progress measurement is based only on the gap in employment rates between PwDs and PwoDs. This is certainly a meaningful measure, but on its own it isn't enough to conclude that Canada is barrier-free around employment. There are many aspects to consider when determining if and where there is progress being made in equitable employment, such as promotion, retention, and accessible equipment to carry out job duties.

Canada put a strategy in place to measure progress in 2022, the Federal Data and Measurement Strategy for Accessibility, which flows from the DIAP's Accessible and inclusive communities pillar. To implement the strategy, a Performance Indicator Framework for Accessibility Data is being developed. This framework:

- aims to define ways that the federal government will measure "progress in the removal of barriers to accessibility over time"

- includes a list of 32 indicators that cover different aspects of employment, with 11 existing data sources

- relies upon national surveys for most sources, which can help measure progress towards a barrier-free Canada

Progress measured by the framework will reflect combined efforts at all levels of government and will not directly measure the impact of what FREs do under the Accessible Canada Regulations (ACR), which is limited to specific sectors. Only 1 indicator is specific to the ACRs' impact: "18. Proportion of accessibility plans that include references to specific barriers to accessibility in federally regulated workplaces." This proportion should be high because FREs have a legal obligation to identify barriers and to publish APs, but it remains unclear what progress this indicator will measure.

These important federal accessibility initiatives are meant to help reach the goal of barrier-free Canada by 2040. Yet they don't all seem to be aligned, for example the Employment Strategy for Canadian with Disabilities does not mention the Performance Indicator Framework. And while each are somewhat different in scope, I encourage aligning the development of progress measures where possible to maximize our capacity to create and collect meaningful and reliable accessibility data to measure and evaluate progress towards a barrier-free Canada.

I'm pleased to note the progress on other federal commitments to break down employment barriers. For example, in February 2024, the Clerk of Privy Council's Annual Report to the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada confirmed that the Government had achieved 80% of its target to hire 5,000 new employees with disabilities by 2025. The Government's commitment to work in close collaboration with employees with disabilities also remains evident for example through the Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee, led at the Deputy Minister level. The committee supports public service employment equity objectives, by serving as a forum for networking and sharing of best practices on disability inclusion and accessibility among departments and agencies.

Progress towards a barrier-free Canada

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Progress towards a barrier-free Canada (no audio)

English content

Unfortunately, not all national policies and initiatives are designed with accessibility in mind. It is often only an after-thought. However, the federal government has been promoting disability inclusion even before the Accessible Canada Act was made law. More national studies are now regularly measuring some meaningful indicators of accessibility. In this section we'll look at progress at a national level, that is not specific to the Act. This section summarizes and discusses national-level data measuring changes in recent years in accessibility, both in employment and more broadly.

National progress in employment

"Accessibility goes beyond accommodations - it's a strategic advantage that drives innovation, productivity, and long-term business success. When we prioritize inclusion, everyone is empowered to bring their whole selves into every space, building stronger teams, tighter bonds, and a better future for everyone."

- Yat Li, Associate Director, Accessible Employers

Statistics Canada has been conducting the Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) since 1986. The last one was conducted in 2022. This survey focuses on issues affecting PwDs, including around employment. My team and I looked at the CSD survey results. We also identified additional studies of national scope that provide reliable and meaningful data to help assess equity gaps related to disability in Canada. Based on reviews of the CSD and these other studies, I have identified and summarized a number of persistent issues at several stages of the employment cycle. The cumulative effect of these problems is wasting the economic potential of 850,000 Canadians with disabilities who are ready and able, but face barriers in getting to work.

School to work transition: Among students with disabilities requiring devices, support services or modifications to their environment, nearly half still have unmet needs. This has not changed much between 2017 (46.1% of school, college, CEGEP or university students with unmet accessibility needs) and 2022 (46.3% of students). Education is a major path to getting a job. If PwDs are disadvantaged at the education stage, it creates barriers to employment.

Entry into labour force: PwDs remain much less likely to be in the labour force, despite a small reduction in the equity gap. In 2017, PwDs were 20.1% less likely to be in the labour force compared to persons without disabilities (PwoDs), but only 14.6% less likely in 2022. Statistics Canada defines the labour force as "persons who contribute or are available to contribute to the production of goods and services." This includes people who may be employed or not.

Work experience: Among PwDs who have no job, more than half continue to find that their lack of work experience is a barrier to employment. This has increased a little between 2017 (53.8%) and 2022 (55.1%). This persistent problem might contribute to a vicious cycle. If PwDs don't get a chance to work, they can't acquire work experience, which increases the risk of them taking a job below their qualifications or below their potential, remaining jobless, or even opting out of the labour force entirely.

Employment status: PwDs also remain much less likely to be employed, despite small improvements. The Government of Canada highlighted in its 2024 Employment Strategy for Canadians with Disabilities, that the equity gap in employment has decreased recently. In 2017, PwDs were 20.8% less likely to be employed compared to PwoDs, and only 16% less likely in 2022. However, an equity gap of 16% is still significant.

Discrimination in employment: PwDs who are employed still endure discrimination at work. A 2022 Survey on Employment and Skills (PDF format) report indicated that: "One in four employees with disabilities experiences discrimination in the workplace because they have a disability." Statistics Canada's labour market analyses found that the equity gap affecting PwDs in employment has been consistent through the years, which is partially due to "unmet workplace accommodation needs and workplace discrimination."

Full-time employment: PwDs are still less likely to have a full-time job, in comparison to working Canadians overall. In 2017, 77.1% of employed PwDs had a full-time job, compared to 80.7% of employed PwoDs (3.6% difference). Similarly, in 2022, 78.9% of employed PwDs had a full-time job, compared to 82% of employed PwoDs (3.1% difference). While some PwDs may choose or even prefer to work part-time, full-time status may affect economic power and stability. This is particularly important for PwDs who often have additional medical expenses, as well as expenses for adaptive products and personal supports which are necessary to ensure dignity, autonomy, and full participation in society.

Low income: PwDs are still more likely to earn a low income. Between 2017 and 2022, the proportion of PwDs earning $30,000 per year or less (after tax) went from 55.6% to 40.6% (15% decrease). In the same period, the proportion of PwoDs in this income category went from 38.1% to 29.1% (9.0% decrease). It is encouraging to see a decrease in this equity gap (17.5% in 2017 to 11.5% in 2022). Efforts need to continue to maintain and accelerate this trend.

High income: PwDs are still less likely to have a high income, despite a small increase. Between 2017 and 2022, the proportion of PwDs earning $80,000 or more per year (after tax) went from 5.7% to 8.8% (3.1% increase). In the same period, the proportion of PwoDs in this income category went from 10.5% to 14.5% (4% increase).

Retention: PwDs still may leave their job due to disabilities. Among people who left their job in 2019, 10.3% did so because of their "own illness or disability" That proportion was still at 9.5% in 2023. This suggests that 1 in 10 PwDs feel that they cannot be productive because of a pre-existing or new disability. Given known discrimination against PwDs, it is likely that this number is underestimated. There doesn't seem to be public data on how many PwDs lose their job (layoff, dismissal, or such) due to disabilities.

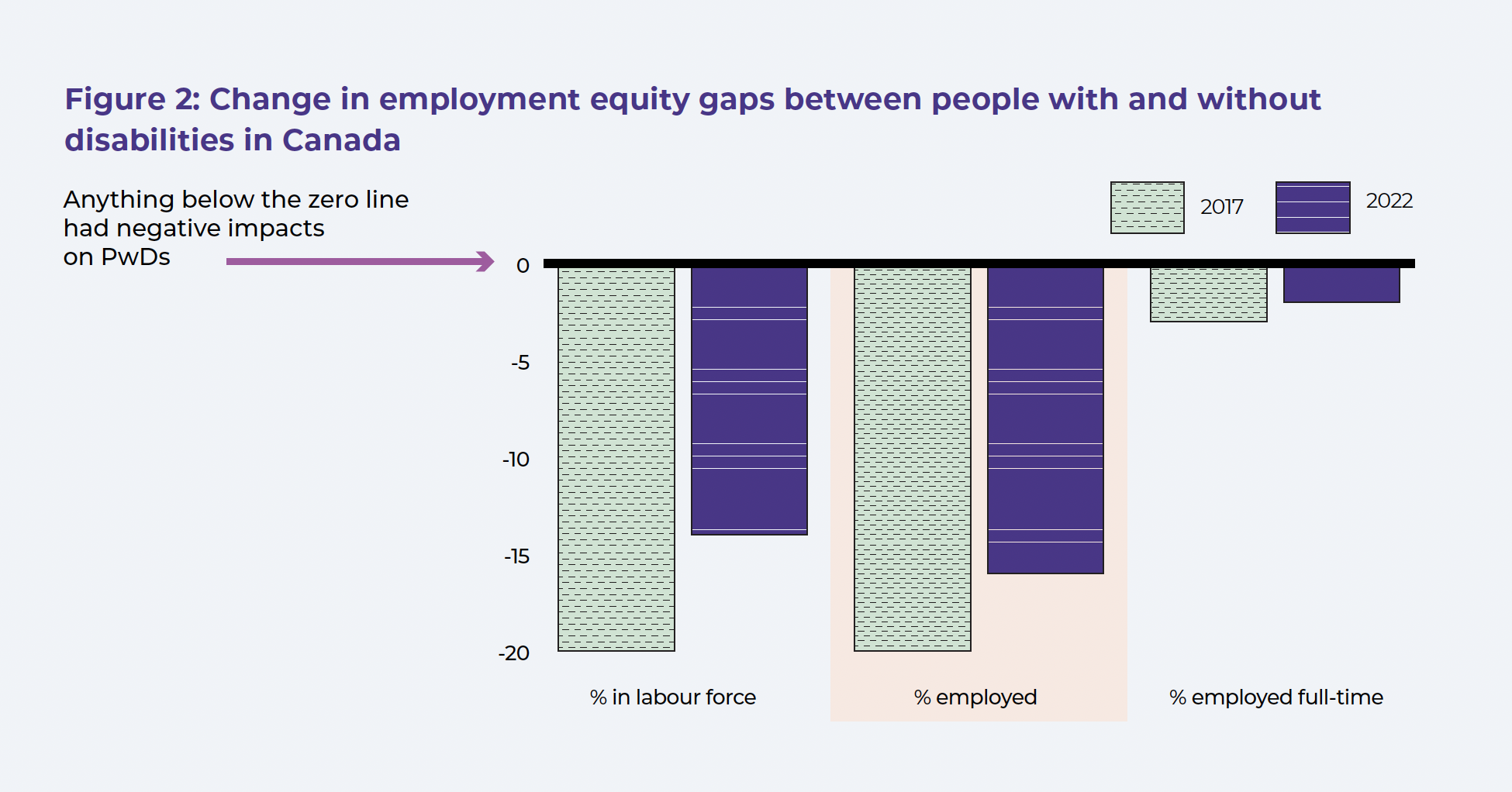

Figure 2 - text description

This illustration displays a vertical bar chart comparing people with disabilities and people without disabilities in Canada, using published data from the Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD). The comparisons are based on 3 indicators: percentage of people in the labour force; percentage of people employed; and percentage of people employed full-time.

Each bar represents an equity gap, that is the percentage among PwDs minus the percentage among PwoDs. The zero line represents equity for either indicator. Bars below that line have negative value, indicating an equity gap with a negative impact on PwDs. Each indicator has two bars: one for 2017 data and one for 2022 data. A shorter 2022 bar indicates progress towards the ACA's goal of having zero barriers in employment.

According to CSD data, between 2017 and 2022: the gap for people in the labour force went from -20% to ‑14.6%; the gap for people employed went from -20.8% to -16%; and the gap for people employed full-time went from -3.6% to -3.1%.

This means that there was improvement in all 3 indicators. It also means that the improvement is slow and there's still a long way to reach equity in employment.

National progress on wider commitments to disability inclusion

In my first report, I highlighted the need for action in 4 key areas to make progress towards achieving the goals of the ACA: mandatory training, regulations, dedicated accessibility funding, and data. Here is what I've observed in the last year since calling for action on these issues.

Mandatory training

As discussed in this report, there is a lack of awareness both in the general population and among FREs about the ACA, despite public information available online. We need training and education campaigns to promote awareness. My office's review of APs and PRs showed that less than 4.5% of initiatives identified by FREs involved mandatory training for employees. We also need more targeted education for Canadians about disabilities, barriers, and accessibility. The large-scale culture shift we need to see requires efforts on both fronts.

Regulations

The Accessible Canada Directorate (ACD) at Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), is currently working on Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) accessibility regulations. These regulations will set mandatory accessibility requirements for digital technology and applications including websites, software, mobile applications, and hardware. ACD's work has been informed by consultations with diverse groups, including PwDs, and it refers to existing international standards. One of those standards, the European Standard EN 301 549 was recently adopted by ASC as a National Standard of Canada (CAN/ASC - EN 301 549:2024). This will be the first regulation specific to one of the 7 ACA priority areas that must be covered by organisational accessibility plans.

| ACA Priority Area | Standards | Regulations |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | In progress | 0 |

| Built Environment | 3 | 0 |

| Information and communication technologies | 1 | In progress |

| Communication, other than information and communication technologies | 0 | 0 |

| Procurement of goods, services and facilities | 0 | 0 |

| Design and delivery of programs and services | 0 | 0 |

| Transportation (airlines, as well as rail, road and marine transportation providers that cross provincial or international borders) | 0 | 0 |

| Overarching ACA regulations for plans, progress reports, and feedback mechanisms | 0 | 3 |

All the existing standards are available publicly, online, for free. There are three ACA regulations requiring FREs to publish an accessibility plan, a feedback process, and progress reports, in consultation with PwDs for FREs in general, FREs in the transportation industry, and FREs in the broadcasting and telecommunications industry. The 3 built environment standards (accessible dwellings, accessible design for the built environment, and accessible design for self-service interactive devices including automated banking machines) were published jointly by ASC with the Canadian Standards Association. As mentioned above, an ICT standard was recently adopted by ASC as a National Standard of Canada. In addition, ASC has work underway at various stages on 16 additional possible standards in all of the ACA priority areas.

Dedicated accessibility funding

Since 2019, federal budgets have provided funding related to disability inclusion. These are important investments but there are few dedicated funding streams to support organizations in implementing their obligations under the ACA. Many organisations still consider accessibility to be optional, rather than the necessity it is. Because of this, they cite the costs of accommodations, improvements to buildings and premises, and even the costs of hiring PwDs as reasons not to act. Organizations need to make permanent commitments to accessibility in their budgets.

Data

As mentioned, the federal government has been developing a Performance Indicator Framework for Accessibility Data. This framework reflects the Government of Canada's approach to measuring progress in accessibility. Currently, there are indicators for only 3 of the 7 ACA areas: employment; transportation; and ICT, and it is unclear when indicators will be built for the remaining 4 areas. The framework is a critical tool for setting a baseline and measuring progress, but the ACA has now been in place for over five years. Progress on this front is far too slow. We have limited data reflecting overall national progress, and by the time this framework is complete, there may be little time left to course correct.

Disability remains a top reason for human rights complaints in Canada

In the absence of a finalized national framework to measure accessibility progress, we can look at related data to have an idea of trends in disability inclusion at the national level. For example, the 2023 Canadian Human Rights Commission's annual report (PDF format) says that, among the 663 complaints they accepted in 2023, almost half (49%) related to disability. The 5 previous years (2019 through 2023) reported an average of 52% of accepted complaints related to disability. Of course, these numbers do not account for the PwDs who experience discrimination or harassment and do not file formal complaints, complaints accepted by provincial and territorial authorities, and complaints that don't get processed. There is still a long way for Canada to go before becoming barrier-free.

FREs can learn from others

"The creation of disability employee resource groups within organizations have also provided a safe space for employees with disabilities to discuss their challenges, identify gaps within the organization, find solutions, and advocate for their needs. In the past, employees with disabilities were often isolated, or existed within silos, but these resource groups have created a safe space for open dialogue."

- Anu Pala, Accessibility Consultant, Professional Speaker, Podcast Producer

The British Columbia Presidents Group aims to make British Columbia the province with the best PwD employment rate. In 2021, they launched the Pledge to Measure, to encourage leaders and organizations in small and medium-sized businesses to create safe and inclusive workplaces for people with disabilities through transparent reporting and accountability. Businesses that register for the Pledge get access to resources and guidance to support their efforts. Participation in the Pledge is a form of commitment that the public can follow up on in progress reports published by participants. Outcome measures include the current number of employees with disabilities and the number of leaders with a disability.

I've also found good practices in the federal public service. Among these are the vast and active networks of employees with disabilities across departments and agencies for sharing information and best practices. There is the Government of Canada Workplace Accessibility Passport which records agreements between employees with disabilities and their managers about the tools and measures needed to support the employees' success. The passports should remove the need to renegotiate supports when the employee changes managers or organisations. I'll also be following the work of the Canadian Business Disability Inclusion Network, launched in December 2023, in helping its member business organizations improve the accessibility of their respective workplaces and encourage other FREs to do the same. I know that many employers are committed to inclusive employment but need support in delivering on that commitment. Initiatives like these, that support needs of both PwDs and employers, are important to get to a barrier-free Canada.

Support for employers

Workplaces are complex environments with many demands from many people, and increased requirements for accessibility may seem too much to handle. Accessibility efforts require support for PwDs, but also for other people involved, including current and potential employers. Some employers are aware of the importance of accessibility and have found ways to address this in their environment. For employers who are getting started on accessibility, there are numerous resources available, from specialized employment services and agencies, consultants, conferences, and more. For example, the Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work (CCRW) is a national not-for-profit organization that offers incentives to employers, as well as disability training, accommodation assessments, and other services from hiring to retention. In addition, the CCRW holds annual conferences on themes relevant to PwDs, including employment, and bringing together business, government, and disability communities.

Systemic issues in Canada

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Systemic issues in Canada (no audio)

English content

"I completed a neurology residency and fellowship as a paraplegic. It's been both challenging and rewarding. Fortunately, I had incredible mentors and allies who advocated for accessibility on my behalf. This kind of support and allyship has been essential in creating lasting change."

- Dr. Harinder Dhaliwal

This section describes widespread impediments to disability inclusion in employment for people with disabilities, that relate to all parts of any organization.

Ableist culture and unconscious biases

Decision-makers and other leaders continue to make assumptions about what PwDs can do and cannot do, which contributes to persisting discrimination. They bring these longstanding biases to the workplace, attaching stigma to disability and upholding barriers to inclusion as a result. This affects the way leaders in the workplace set workplace rules, how they analyse inclusion issues, and how they make decisions. In addition, despite efforts to raise awareness and calls for empathy, there are still negative attitudes among leaders and employees. This affects how they interact with PwDs, and how PwDs feel and fare in the workplace. These issues have been well-known and widespread through Canadian history, despite laws forbidding them.

Shifting the culture

While there is still a long way to go in breaking down attitudinal barriers, stigma and discrimination, there are pockets of progress towards a culture of inclusion. During my engagements, I heard from those within the federal public service and employment support providers that the culture is starting to shift in the right direction. While progress is uneven, those noticing a shift in culture point to an increase in accommodation centres within the public service and an increase in some managers seeing the value of hiring PwDs and wanting to get it right when hiring them. Others have pointed out the increase in disability networks within FREs as a positive sign. Our AP/PR analysis found that some companies have created disability resource groups, networks, or committees including Cargill Ltd., Cisco Systems Canada, Farm Credit Canada, Fairchild Radio Group Ltd (AM1430), Greater Toronto Airport Authority, Infrastructure Canada, and National Research Council Canada. These networks and committees have the potential to strongly advocate for people with disabilities and push internally for change and more inclusiveness. From my own observations, interest in disability and inclusion has never been at the forefront of so many conversations. I hope this means we are at a tipping point with culture change.

Discrimination in employment

In 2020, a Statistics Canada survey found that more than half (51%) of PwDs had experienced discrimination at work, compared to only 34% among persons without disabilities. According to a 2024 Rick Hansen Foundation survey (PDF format), the most frequent barriers or challenges with employment in Canada include lack of awareness and unfavorable attitudes. The same finding came from a qualitative study by the Office of Public Service Accessibility (PDF format) based on interviews with 53 federal government employees with disabilities. These employees shared that, in the workplace, harassment usually occurs when they request accommodations.

Inconsistent definitions of disability in federal laws

Disability language across federal laws is not consistent. For example, the Employment Equity Act of 1995 uses a different definition of disability than the ACA; it uses a more restrictive definition that relies on the medical model. One of the recommendations in the 2023 Report of the Employment Equity Act Review Task Force is to update the definition of disability, to match the ACA definition which focuses on the barriers in society (e.g., attitudes, systems) that exclude PwDs, and not individual conditions. This update is certainly overdue. All laws in Canada should use consistent wording to avoid contradictions and ensure that PwDs' rights are respected. As of September 2024, the Task Force's recommendations are only proposed changes. The Minister would need to formally table them in Parliament to turn them into legal requirements.

Lack of ownership for all ACA priority areas

During consultations that led to the ACA, most participants expressed that all areas of accessibility were interconnected and equally important; no one area was a priority over another. For practical purposes, the Act was written in a way that separated out 7 priority areas. However, I'm seeing that this inadvertently encourages FREs to think about disability inclusion in silos. As noted earlier, we heard that some PwDs have difficulty getting to work because there are no or limited accessible transportation options. And yet I was surprised to see, in the accessibility plans that I read, that many FREs chose not to address transportation in their plans. FREs need to take responsibility for all 7 ACA areas when identifying, removing, and preventing barriers related to employment.

The importance of intersectionality

We also know that PwDs are found across all demographics. Lived experience in one equity-seeking group can impact and compound the way in which a PwD experience barriers. This is often referred to as intersectionality. It is important to consider PwDs' other social identities (age, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, income, and education) when removing barriers to accessibility. When this intersectionality is not addressed in accessibility planning it excludes an important piece of an organization's inclusiveness, both for employees and the clients they serve.

Intersectionality and Nova Scotia's 2017 accessibility law

We can learn from provinces' reviews of their accessibility laws. For example, in 2023 Nova Scotia published their first Independent review of the Nova Scotia Act on Respecting Accessibility. The review found a lack of consideration for intersectionality. For example, Indigenous people with disabilities experience inequalities, like lower incomes and discrimination, related to their Indigenous identities in addition to barriers to accessibility. This results in unique accessibility barriers that will differ from non-Indigenous PwDs. This is an important lesson for all levels of government as they build legislation and regulations to ensure support for the most vulnerable and marginalized PwDs.

Lack of dedicated resources for disability inclusion

I mentioned this in my 2023 report and I've mentioned it in this one too. But it is worth repeating: we cannot achieve a barrier-free Canada without adequate, dedicated resources. To promote awareness of the Act and disability inclusion, FREs need to have the resources to learn about and understand disability barriers in their workplace and how to remove them. FREs also need financial means to remove and prevent these barriers, and access to qualified people to get that work done. Monitoring change and enforcing accountabilities also takes resources. If there are not adequate financial and human resources to inspect, evaluate, and enforce compliance with the ACA, FREs may remain unchecked, there will be no consequences for inaction, and this will slow down or halt progress.

The AODA experience: lessons learned

In 2023, Ontario released the Fourth independent review of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) of 2005. The report concluded that Ontario would not meet its target of a barrier-free Ontario by 2025. Reasons for this included poor enforcement of its accompanying regulations and a lack of resources. Low enforcement has led to low compliance and, as a result, accessibility has not emerged as a priority, despite the Act having been in place for 19 years. This is a valuable lesson about the importance of adequate enforcement and resources for all accessibility legislation.

Complexity of Canada's government structure

In Canada, federal, provincial, and territorial governments have different areas of responsibilities. The ACA calls for intergovernmental collaboration on accessibility matters, which is critical to shift the culture across all regions in Canada. I am aware of large-scale initiatives to coordinate such efforts, some led by federal organisations. But it is still unclear how the federal government will ensure country-wide alignment in accessibility practices.

The 2023 Accessibility Commissioner's Report indicates that some FREs were not aware that they have legal obligations for accessibility at different levels of government. They thought that they didn't have to publish an AP under the ACA if they already had a plan under a provincial accessibility law. This can create serious equity gaps in the accessibility of the products and services offered by these organisations.

Misalignment of accessibility standards and regulations across Canada

Standards and regulations that involve disability or impact disability can be quite different depending on where someone lives in Canada. While differences in regulations and standards may serve to adapt to local conditions, it can also make it more difficult to remove and prevent barriers consistently across Canada. Consequently, PwDs in Canada may have differing expectations and experiences of barriers region to region, which can result in unequal participation in society. While I certainly respect the different jurisdictions and their independence (as well as the value of friendly competition), choosing to harmonise our efforts whenever possible will reflect our collective commitment to make all of Canada barrier-free. In addition, by working collaboratively and sharing experiences and best practices, all jurisdictions stand to benefit.

Canadian North

When visiting the Northwest Territories (NWT) in the summer 2024, I learned about the diversity of culture and the people who live there. For example, the NWT has over a dozen official languages, representing the diversity of Indigenous cultures. The last residential school closed in NWT in 1997 and the legacy of residential schools continues to affect Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous people with disabilities often must leave their communities to access supports. It is vitally important to consider the intersection between Indigenous experiences and disability. Cultural experiences of disability need to be widely understood and considered as barriers to accessibility are removed.

Emerging issues

American Sign Language (ASL) version of Emerging issues (no audio)

English content

Beyond the systemic issues identified above, my team and I noted some accessibility themes in 2023 that have received significant public attention.

Emerging issues in employment

Transition from education to employment

Education credentials are essential to many job opportunities., but students with disabilities face many barriers. These barriers involve the access to mainstream training, and getting the accommodations needed to study in terms of material formats, communication media, and physical space. Education is beyond the scope of the ACA, as it falls under provincial and territorial governments' responsibility. This is a key area where different levels of government need to collaborate and coordinate efforts to remove and prevent barriers. As part of this collaboration, it's important to understand how government policies influence different labour market needs in Canada and to use this information to make sure that education and skills training, including for students with disabilities, are well matched with local job markets.

Return to office

The remote working options that became the norm for many during the pandemic, provided new opportunities for employment for some people with disabilities. In May 2023, the World Health Organisation declared that COVID-19 was no longer a health emergency. Since then, more and more employers have decided that they want their staff to return to work in employer-provided workplaces. There are diverse opinions on this issue among PwDs. For example, some employees with disabilities find working remotely most accessible, while others feel it segregates them from their workplace and team. Ideally, employers should understand that telework can be an essential accommodation. PwDs also need to respect that some jobs are less conducive to remote work. Where employers require employees onsite, efforts must be made to ensure accessible workplaces.

Remote work and PwDs

PwDs' have diverse perspectives about returning to work from the office. For employees with disabilities, finding meaningful employment isn't always as simple as accepting a job offer. Depending on their type of disability, PwDs may not have access to reliable and/or accessible transportation to commute to work; they may not be able to physically get into their office building; there might not be an accessible bathroom on site or a sign language interpreter; they may have to work in an office that doesn't meet their ergonomic needs or is too over-stimulating. Some PwDs report higher rates of discrimination when working in the office. The option to work from home can help remove these barriers. .

Digitisation of services

Over recent decades, newer technologies have been transforming the way we access services. This affects many daily activities such as: buying bus tickets, borrowing library books, ordering food, and withdrawing cash. Digitisation is the process of converting information into computer-readable formats. This can improve information sharing, transaction speed, and even equity when accessibility features are integrated by design, or when new tools can be adapted to PwDs' needs. However, digitisation may also generate new costs and learning curves, or create new barriers for some PwDs. For example, removing the option to use the phone creates a barrier for some PwDs. For this reason, it is important to offer services through multiple options, digital and non-digital, so that nobody is left out.

New technology is not progress if it creates barriers

In a 2023 study by the University of Waterloo and the Canadian Standards Association, PwDs shared that most self-serve devices have few or no accessibility features. As a result, PwDs often need to seek someone else's help to use service kiosks, automated teller machines (ATMS), and similar devices. This can affect their privacy, and their security. There are some initiatives to address this issue, including in the banking sector. For example, the website of the Royal Bank of Canada indicates that, as of December 2010, all their banking machines were voice guidance activated (for clients with vision loss) and each branch has at least one dedicated wheelchair accessible ATM.

Emerging issues beyond employment

Housing

Finding and keeping adequate housing has become a top concern for many Canadians, especially PwDs. Canada's 2017 National Housing Strategy recognizes housing as a human right. The Strategy cites PwDs as a priority group, but as of March 2024, new and renovated accessible units are still only at the commitment stage. PwDs are four times more likely than persons without disabilities to end up homeless when they do not have access to suitable housing. They are also at risk of being removed from their community and placed in long-term care homes or hospitals when accessible options are not available. Because accessible and adaptable homes are rare, it reduces work mobility options for PwDs who can't take a job in another location if there isn't an accessible home available for them. Accessible housing is everyone's business. Universal designs, adaptable housing, and accessible dwellings are a necessity, not a "nice-to-have" feature because anyone can acquire a new disability at any point in life. I join the Federal Housing Advocate and others in highlighting persisting equity gaps and systemic issues affecting PwDs in housing.

Transportation

PwDs may face barriers while going about their daily activities or while traveling for business or pleasure. Accessibility complaints can affect transportation companies' reputation and can lead to legal penalties. While all forms of transportation need to be accessible, accessibility in the air transportation sector has been a long-standing issue that has been receiving significant attention since 2023. Numerous media stories highlighted equity gaps in air travel that affect client dignity, safety, and service quality. These stories prompted parliamentary committee proceedings as well as a National Air Accessibility Summit in May 2024. During the latter event, the federal government and the air travel industry re-committed to doing better. As I said in my public statement, we need meaningful action now.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial Intelligence (AI), the use of computers and machines to reason, learn and act like human intelligence, has become a popular method for processing information quickly. Examples include virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, chatbots for online customer service, and platforms that generate content like ChatGPT. It is increasingly being used in the employment sector for recruitment, for example using algorithms to screen job applications.