Evaluation of the Work-Sharing Program

List of tables

- Table 1 - Changes in Work-Sharing Programs in selected countries during the 2008-2009 recession

- Table 2 - Participation and benefits paid to Work-Sharing participants

- Table 3 - Average work reductions, weekly benefits, and duration of Work-Sharing claims

- Table 4 - Distribution of Work-Sharing claim durations, by fiscal year in which the claim started

- Table 5 - Estimated layoffs averted and postponed by the Work-Sharing Program

- Table 6 - Layoff within 6 months of the Work-Sharing Agreement termination, by the year the claim started

Executive summary

Program objective

Work-Sharing is an adjustment program designed to help employers and workers avoid layoffs when there is a temporary reduction in the normal level of business activity that is beyond the control of the employer. Layoffs are avoided by offering Employment Insurance Part I income support to workers willing to work a temporarily reduced work week while their company recovers. The goal is for all participating employees to return to normal working hours by the end of the term of the Work-Sharing agreement.

The program helps employers retain skilled employees and avoid the costs of recruiting and training new employees when business returns to normal levels. It also helps employees maintain their skills and jobs while supplementing their wages with EI benefits for the days they are not working. While the Work-Sharing program primarily responds to temporary economic recessions, the program also has special measures which can be used to assist employers affected by a disaster or state of emergency.

In response to the high level of uncertainty faced by many businesses during the 2008-2009 recession which was both rapid and steep, the Work-Sharing program introduced a number of temporary changes to help firms remain viable during the agreement period. The current evaluation places particular emphasis on the assessment of recent program changes, both temporary and permanent, implemented in response to the economic recession Footnote 1 .

Evaluation key findings

Overall, the evaluation found that the changes introduced during the 2008-2009 recession were effective as they allowed a large number of employers to avoid unnecessary layoffs when faced with a temporary downturn in business that was beyond their control, thereby meeting the objective of the program. That said, the changes did not prevent structural adjustments that may occur during and after a recession (i.e., affecting the likelihood of a firm completely shutting down or workers being laid off after the termination of a Work-Sharing agreement).

Program participation is highly counter cyclical. That is, the number of Work-Sharing claims increase during economic recessions and decline during periods of recovery and economic growth. During the last recession, participation and program expenditures went from a low of just over 10,000 claims and $11 million to a high of about 139,000 claims and $235 million. While, at peak participation, Work-Sharing as a share of total employment accounted for 0.83% of total employment, it is important to note that the program offered a form of job stability and financial security to a large number of employees which can have a multiplier effect on communities.

Averted layoffs

Many participating employers attributed Work-Sharing with helping their company avoid temporary layoffs and returning to normal levels of production. However, obtaining a precise estimate of layoffs averted can be challenging and the best estimates typically involve a number of assumptions based on observed work reductions. The evaluation found that a large percentage of layoffs were averted. This evaluation estimates that a layoff has been averted when it has remained averted for at least 6 months following the agreement termination.

- On average between the years 2000-01 and 2010-11, 60% of layoffs averted during the agreement, remained averted for at least 6 months, resulting in an estimated net effect of 11,189 and 24,385 layoffs averted during the years 2008-09 and 2009-10 respectively. This was an improvement over the estimated 49% of layoffs averted for 6 months during the 1990-91 to 2001-02 period, as documented by the 2004 Work-Sharing evaluation

- The temporary measures which extended the maximum agreement length during the 2008-2009 recession, were found to have no influence on the likelihood of workers being laid off in the six months following the expiry of the Work-Sharing agreement. Rather, the layoff rates followed a counter cyclical pattern regardless of the whether or not agreement extensions were available

- The likelihood of a firm completely shutting down after the termination of an agreement was found to be very low for firms with over 5 employees on Work-Sharing, and virtually nil for firms with over 25 employees on Work-Sharing

- More than 75% of employers said that the costs of lay-offs in terms of subsequent recruiting and training would have been very substantial and that avoiding this was the principal benefit of applying to the program

Other key findings

- The evaluation did not find any evidence to suggest that the program’s take-up, in terms of volume of participants, increased beyond what could be expected from its typical counter cyclicality. However, the average agreement size increased during the recent recession, both in terms of employees claiming Work-Sharing per employer, and in terms of the average claim duration

- It was found that Work-Sharing has positive impacts on communities and employees. Work-Sharing supports communities by averting a number of layoffs and allowing employees to retain their jobs, maintain non-salary benefits, reduce their stress and increase their economic security

- Due to the relatively small scale of the program when compared to the size of the total labour force, the ability of the program to act as an automatic stabilizer during a recession is limited

- Service delivery and policy implementation varied between regions but overall, employers were satisfied with the services provided by the program

- The program was successful in responding to the large increase in the number of applications and enquiries. On the employee (recipient) side, however, some raised the issue of delays in the delivery of initial benefits, as well as to their own lack of knowledge regarding program benefits, criteria and the associated implications of their participation

- Prior to the 2008-2009 recession, there were limited resources directed towards creating awareness of the Work-Sharing program. Increased media attention received courtesy of references in the Budget 2009, raised the program’s profile to both the public and employers alike

- Larger companies who had the resources and business expertise to develop comprehensive plans were better able to anticipate the recovery process in their plans. Comparatively, smaller firms or those whose issues were related to overall economic conditions and unforeseen circumstances had more difficulty in predicting full recovery

- Employers used the additional weeks of benefits to apply for longer agreements during the recession. The evaluation also found evidence that a portion of claimants were laid off after the termination of their agreements, and that the longer agreement lengths did not have any impact at reducing the rate of these layoffs

Recommendations

Based on the key findings, the evaluation makes the following nine recommendations:

- explore ways to improve the speed of the delivery of benefits to employees

- explore ways to improve reporting processes for smaller companies

- examine the multiple signing authorities and how the process can be streamlined

- ensure greater consistency in program delivery across the country

- improve the efficiency of program delivery by learning from the region’s best practices

- draw upon lessons learned from the implementation of temporary measures during the 2008-2009 economic recession to assess whether similar measures should be considered during future recessions (e.g. examine the continued relevance of the recovery plan or alternate ways to further streamline the application for employers)

- increase outreach activities to employers. Ensure that potential beneficiaries of the program are aware of it

- increase outreach activities to employees. Provide greater clarity on the programs benefits, criteria and all the associated implications to their participation

- review the application process and explore how the program might be more widely used by the non-manufacturing sectors

Management response

Introduction

The Skills and Employment Branch (SEB) and Program Operations Branch (POB) would like to thank those who participated in conducting the evaluation of the Work-Sharing program. In particular, SEB and POB acknowledge the contributions of all key informants who participated in interviews during the course of this evaluation, including employees, employers, and program officers. Additionally, SEB and POB extend sincere appreciation to departmental colleagues from various operational and policy units who contributed to the development of the Management Response.

Work-Sharing is an adjustment program designed to help employers and workers avoid layoffs when there is a temporary reduction in the normal level of business activity that is beyond the control of the employer. Layoffs are avoided by offering Employment Insurance (EI) Part I income support to workers willing to work a reduced work week while their company recovers. The goal is for all participating employees to return to normal working hours by the end of the term of the Work-Sharing agreement. The program helps employers retain skilled employees and avoid the costs of recruiting and training new employees when business recovers. It also helps employees maintain their skills and jobs while supplementing their wages with EI benefits for the days they are not working. While the Work-Sharing program has largely responded to temporary economic recessions, the program can also be used to assist employers affected by a disaster or state of emergency.

Recognizing the high level of uncertainty faced by businesses caused by the 2008-2009 economic recession, the Government of Canada put in place a stimulus package among the G-7 countries—the Economic Action Plan. With regards to Work-Sharing, temporary policy measures were implemented quickly in Budgets 2009, 2010, and 2011 and Fiscal Update 2011 to help businesses remain viable during the recession.

Significant increases in both the number of Work-Sharing enquiries and applications required scaling up of regional expertise from a service delivery, policy and processing perspective. Resources were mobilized quickly and effectively to ensure a timely response. In that context, the temporary measures were critical, giving the economy time to rebound and offering financial security to a large number of employers, employees and communities. Permanent policy adjustments were subsequently made in 2011 to make the program more flexible and efficient.

SEB and POB agree with the evaluation findings, and propose the following Management Response, in collaboration with Processing and Payment Services Branch (PPSB) and the Citizen Service Branch (CSB).

Key evaluation findings

Overall, the findings of the Work-Sharing evaluation are positive and demonstrate that there is a continued need for the program, particularly during times of economic downturn. The evaluation found that the program is achieving its expected outcomes and contributing to both monetary (e.g. financial security) and non-monetary benefits for employers, employees and communities (e.g. positive impacts to employee morale, improvements in employee/firm relations). Moreover, both employees and employers are reportedly satisfied with the service provided by the program with employers being especially positive about the degree of government support they received.

Most importantly, the evaluation found that the program was particularly effective during the economic downturn. The evaluation found that overwhelmingly firms which participated in Work-Sharing were unlikely to completely shut-down after the termination of their Work-Sharing agreement. This suggests that the program is not delaying closure of failing businesses, but rather supporting companies who are facing work-shortages due to temporary business downturns. Interestingly, by this measure the program effectiveness actually increased when the program was scaled up in the downturn. Furthermore, evidence from the evaluation’s review of program files confirms that 74% of the 226 approved agreement files reviewed returned to normal levels of business by the end of the agreement. These findings are important because they demonstrate that the program is working as it should – helping employers avoid unnecessary lay-offs when they are experiencing a temporary downturn in business that is beyond their control.

The evaluation also found that:

- layoffs averted were estimated at 11,189 in 2008-09 and 24,385 in 2009-10

- program participation continues to be counter cyclical and largely used by the manufacturing industry

- average claim duration increased during the recent recession, as employers used the temporary measures allowing for longer maximum agreement length

- there are opportunities to enhance program/service delivery models, streamline the application/approval process, and increase outreach activities to increase program participation in sectors that have made limited use of the program (i.e. Service Industry, retail, real estate, professional companies, financial industry and not-for-profit sector)

Recommendations and follow-up actions

The Work-Sharing Evaluation outlined two areas (i.e. Program Delivery and Program Participation) for follow-up action.

Program delivery

Follow-up action 1: Improve on the speed of the delivery model, especially regarding the delivery of initial benefits to employees.

The program area agrees that the timely delivery of benefits is an important factor in providing efficient and responsive service delivery. As noted, given the large increases in both the number of Work-Sharing enquiries and applications received during the economic downturn, the department rapidly mobilized expertise from a service delivery, policy, and processing perspective to ensure a timely response.

In efforts to further enhance the service delivery model, processing of Work-Sharing claims was automated in 2009. In addition an Inventory Reduction Strategy was recently implemented to bring outstanding work to sustainable levels of EI claims by October 2016. Further to the Inventory Reduction Strategy, the Department is developing a more agile funding model to ensure the necessary mechanisms are in place to respond to increased EI claim volumes and meet the needs of Canadians.

PPSB conducted a study of benefit processing times for the program to determine areas for improvement in order to ensure the speed of pay targets were met. This study indicated that 87% were paid within 28 days, 9% had a delay attributable to the employer or employee and 3% had a delay attributable to Service Canada.

In addition, the Department has reminded the Insurance Payment Operations Centres (IPOCs) of the need to process the utilization reports within the speed of service targets. The Department will monitor this on an ongoing basis.

Further, the results of this study will be shared with departmental stakeholders in order for them to ensure that communications with employers and employees regarding their WS agreements/benefits reiterate the message that all documentation must be provided in a timely manner for payments to be issued within the prescribed timelines.

Follow-up action 2: Improve reporting processes for smaller companies.

It is recognized that smaller companies do not always have the capacity, tools and/or resources required to participate in the electronic reporting system. The Department has recently posted new electronic Utilization Reports that use 60-70% less disk space and may reduce challenges for companies with less robust systems. Although the data gateway system facilitates timely and efficient reporting for employers, it is not the only reporting option available and employers are not obligated to use it. At their discretion, employers may elect to submit paper-based reports via mail or through regional service sites. The reporting mechanisms chosen by the employer must respect applicable privacy and security protocols pertaining to information management. Program officers will continue to work with employers to identify their preferred approach.

Follow-up action 3: Examine the multiple signing authorities and how the process can be streamlined.

The program area agrees that it is important to continually assess program delivery processes to identify potential opportunities for enhancement. In this regard, while multiple signing authorities may present challenges in facilitating timely approval of agreements, the program area has taken steps to ensure that all applications are processed as expeditiously as possible.

As per program guidelines WS agreements over $600,000 as well as special measures or policy changes currently require approval of the Canadian Employment Insurance Commission (CEIC). However, this does not prove to be time consuming as applications, upon submission to National Headquarters, only require eight processing days which is within the service delivery standard.

Furthermore, it is important to note that in 2014 only 1.3% of WS agreements were over $600,000 and therefore processed by NHQ.

Follow-up action 4: Ensure greater consistency in program delivery across the country.

The program area agrees that it is important for regional staff to have timely access to policy advice and necessary program tools in order to promote consistency in program delivery across the country.

In this regard, a policy guide and various operational directives were formulated by the program area and disseminated to key stakeholders to promote standardization. The program area will undertake a complete assessment and update of internal and external documents and tools (e.g. Work-Sharing Operational Directives, Applicant Guide, Qs and As, and CSGC Desk Aid), in consultation with regional business expertise advisors. This update will ensure greater consistency and cohesiveness in program delivery across the country.

In addition, the program area has developed an online, national Work-Sharing Training package available through the Online Learning Campus (OLC), which contains five modules aimed at providing program officers with a comprehensive overview of the program. Moving forward, the program area will update the online training package to include a sixth module on the use of the Common System for Grants and Contributions (CSGC) in the delivery of the Work-Sharing program.

The program area will also continue to collaborate with the regions to equip staff with the necessary tools and guidelines to operationalize the program (i.e. Online Training Modules, Operational Directives, regional conference calls).

Furthermore, the program area will evaluate its current Channel Management Strategy for both the 1-800/1-866 call lines and the Service Canada Internet site, to ensure that the department is providing consistent, seamless, responsive and accessible multi-channel service to both employers and employees inquiring about the Work-Sharing program. The program area will continue to ensure that employers/employees across the country have access to up-to-date information through a variety of channels that better meet their needs.

Follow-up action 5: Improve the efficiency of program delivery by learning from the region’s best practices.

The program area acknowledges that some variations in service delivery models across the country are to be expected given differences in regional labour markets and operational structures. However, the Department recently centralized program service delivery within the regions to promote greater information sharing and consistency in program delivery.

Moreover, as part of its ongoing management practices, the program area takes stock of program delivery issues/opportunities across jurisdictions and aims to facilitate information sharing between NHQ and the regions in a variety of ways throughout the year (e.g. monthly conference calls, site visits). Moving forward, the program area will continue to identify best practices in program delivery from both a Canadian and/or international perspective and will share this information among regional partners to help inform potential program/policy enhancements. Furthermore, the program area has undertaken process mapping in each of the regions in order to validate current processes, identify best practices and areas for improvement, and ensure greater standardization of business practices. Best practices will be disseminated to each of the regions in order to optimize operational efficiencies. Linkages between other departmental programs are also being considered to better consolidate intelligence on labour market demand.

Follow-up action 6: Draw upon lessons learned from the implementation of temporary measures during the 2008-2009 economic downturn to assess whether similar measures should be considered during future downturns (e.g. examine the continued relevance of the recovery plan or alternate ways to further streamline the application for employers).

The program area regularly monitors and assesses the economic environment, including labour market conditions across the country to determine the appropriate policy response in the event of an economic downturn. During the 2008-2010 economic downturn, resources were mobilized quickly and effectively under the Economic Action Plan (EAP) to ensure a timely response to assist employers facing layoff situations.

As recovery took hold, the Department undertook a comprehensive review of Work-Sharing in summer-fall of 2010 to prepare for the EAP exit. Key insights/lessons learned from the review, consistent with the findings of the evaluation, indicated that:

- employers were strongly supportive and appreciative of the program

- temporary measures were an appropriate response

- opportunities for administrative adjustments and simplified applications should be considered

- distinguishing between temporary and permanent shock/predicting recovery is challenging; and

- increasing awareness of program is important so that more sectors can use the program

As a result of lessons learned from EAP, a new Work-Sharing program policy was adopted by the Canada Employment Insurance Commission as of April 3, 2011. Permanent changes included a modified Recovery Plan and new utilization rules providing for a minimum 10% work reduction, allowing more flexibility for participating employers to adjust to work fluctuations during the Work-Sharing period.

Given the positive findings of the evaluation, the program area agrees that a similar program response would be considered in the future, should there be another shock to the economy which could include elimination of the recovery plan and potentially longer agreement durations and extensions without the cooling-off period. These are all elements that, when implemented, contribute to the success of the program. In addition, all program partners (i.e. POB, SEB, PPSB and CSB) are reviewing procedures and roles and responsibilities to ensure departmental readiness of various scenarios, should they occur.

Program participation

Follow-up action 7: Increase outreach activities to employers. Ensure that all potential beneficiaries of the program are aware of it.

and

Follow-up action 8: Increase outreach activities to employees. Provide greater clarity on the programs benefits, criteria and all the associated implications to their participation.

The program area agrees that increasing outreach activities to employers and employees is a valuable option to help increase awareness of the program. Departmental service delivery personnel are well equipped to provide detailed program information to both employers and employees through existing service delivery channels. The Department also maintains detailed information about the Work-Sharing program on its website and works to reinforce with regional staff the importance of promoting the program when appropriate.

To that end, the program area will continue to work with the regional staff as well as provincial/territorial governments where appropriate, to inform a variety of sectors about the program. For example, discussions have begun with the Province of Alberta on potential ways to support communications to employers about the availability of the Work-Sharing program as well as in the development of recovery plans, with a particular focus on the required labour market information.

Given the recent downturn in the oil and gas sector, the Department targeted outreach to promote the program to representatives in this sector. The E.I. Commissioner for Employers has played a key role in identifying further opportunities for outreach activities (e.g. employer consultations/information sessions, electronic bulletins to employer groups).

CSB will continue to organize mobile outreach presentations to employers and employees when warranted and explore potential opportunities to include Work-Sharing presentations in other employment related sessions. Mobile Outreach Service offers information services related to Work-Sharing in the form of two decks (one for employees, and one for employers), and provides an information pamphlet to employees which describes the procedure for applying for related EI benefits.

The program area will also work with key internal stakeholders to review existing Work-Sharing information products for workers to determine if any adjustments will be required. Currently, the Department is undertaking a renewal of the Mobile Outreach Service Delivery Strategy to ensure efficient and effective services that support clients in order to increase their access to programs and services and encouraging their usage of digital self-service. Through this renewal effort, CSB will continue exploring means of strengthening the impact and reach of outreach activities related to work-sharing.

Follow-up action 9: Review the application process so that the program might be more widely used by the non-manufacturing sectors.

Historically, the manufacturing industry has accounted for the largest proportion of all WS agreements and small/medium-sized firms are most likely to participate in Work-Sharing. Employers in Ontario and Quebec represent the largest share of users.

The program area reviews the application process periodically to ensure continued relevancy for employers from a broad range of industries and sectors. To help inform future policy options for consideration, the program area will encourage the sharing of best practices amongst regions particularly with regards to the application process and efforts to support program usage by a variety of sectors.

The program area will also continue to explore what other countries do to reach more non-traditional sectors (i.e. sectors outside of manufacturing), and will focus on outreach activities to various sectors/industries when appropriate. The program area will use regional and sectoral labour market information to inform outreach activities in order to ensure alignment with labour market trends.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The 2004 Work-Sharing evaluation found the program worked as intended. The goal of the current 2015 evaluation is to place particular emphasis on the evaluation of recent program changes, both temporary and permanent, introduced in response to the recent economic recession. A detailed description of the nine lines of evidence is provided in Appendix I and a matrix linking the lines of evidence to the evaluation questions is presented in Appendix II. The next section provides a description of the program. Section 3 presents the key findings, and section 4 concludes.

1.2 Background

The Work-Sharing program came into existence under Bill C-27 in 1977, which permitted the use of Unemployment Insurance (UI) funds for a number of “developmental uses.” In the fall of 1977, the program was implemented on a pilot basis. An evaluation of this pilot program found it to be significantly more expensive for the UI Account than the layoff alternative, and the program was discontinued.

In 1981, however, due to a severe economic recession, the federal government reintroduced the Work-Sharing program with some rule changes to remedy the high cost problems found in the pilot phase evaluation. These rule changes made Work-Sharing benefits equivalent to regular UI benefits, and limits were imposed on the Work-Sharing agreement duration. The program was made permanent in 1985. It has been a component of the UI and then the EI program ever since, with little fundamental change in its design or rules until 2009.

1.3 Objective

Work-Sharing is an adjustment program designed to help employers and workers avoid layoffs when there is a temporary reduction in the normal level of business activity that is beyond the control of the employer. Layoffs are avoided by offering Employment Insurance Part I income support to workers willing to work a reduced work week while their company recovers. The goal is for all participating employees to return to normal working hours by the end of the term of the Work-Sharing agreement. The program helps employers retain skilled employees and avoid the costs of recruiting and training new employees when business returns to normal levels. It also helps employees maintain their skills and jobs while supplementing their wages with EI benefits for the days they are not working. While the Work-Sharing program has largely responded to temporary economic recessions, the program has also been used on numerous occasions to assist employers affected by a disaster or state of emergency.

To illustrate how the program works, consider a firm with 100 identical workers, and is considering a temporary layoff of 20 of these workers. If the 20 workers were laid off, they would collect regular EI benefits during their unemployment at a rate of 55% of their insurable earnings. Work-Sharing allows all 100 of the firm’s employees to share the costs of the downturn. Rather than laying off the 20 workers, the firm could reduce the work week by 20% (e.g. work a four-day week) for all 100 workers. All of the workers would collect Work-Sharing benefits for 1 day per week (at the same rate of 55% of their insurable earnings).

1.4 Eligibility

In order for employers to qualify for the Work-Sharing program, they must satisfy the basic eligibility criteria:

- the firm must have been in business in Canada for at least two years

- there must be a minimum of two employees in the work unit Footnote 2

- the shortage of work must be beyond the control of the employer

- the shortage of work must not be due to seasonal factors

- the employer must have the consent of the employees’ union, or if there is no union, of all the employees in the work unit

The employer must submit a recovery plan which demonstrates how the business will return to normal levels upon completion of the agreement. Work-sharing agreements must include a reduction in work activity consisting of between 10 and 60% of the employees’ regular work schedule (i.e., one-half to three days a week). The minimum expected reduction was previously 20%, but Budget 2011 permanently reduced it to 10%. Work-Sharing agreements are signed for a minimum of 6 consecutive weeks up to 26 weeks. Employers may subsequently request an extension of up to 12 weeks, resulting in an overall maximum agreement duration of 38 weeks. Employers are subject to a “cooling-off” period (i.e. number of weeks equal to the duration of the previous agreement) before entering into a new agreement with the same group of employees.

For an individual employee to be qualified for benefits under the Work-Sharing program, he/she must be qualified to receive regular EI benefits. Unlike with regular EI, participants are not required to serve a two-week waiting period prior to drawing benefits. However, if workers are laid off subsequent to the Work-Sharing program, they are fully entitled to regular EI benefits. In such cases, the employees must then serve the two-week waiting period before collecting EI benefits. The amount of time that they are entitled to EI benefits is not affected by their prior use of the Work-Sharing program.

1.5 Delivery

The application process begins with the employer completing a Work-Sharing application. The application can be submitted to a regional, district, or local Service Canada Center. Service Canada staff can help employers in completing their applications to ensure that the eligibility criteria to participate in the Work-Sharing program are met. Service Canada officers review the application and produce a Recommendation Report as to whether the application should be accepted or rejected. If the Recommendation Report is favorable, it can be approved by the local office, regional office, or National Headquarters, all depending on the dollar value of the agreement. Specifically, agreements over $600,000 require approval from the Canadian Employment Commission (CEIC).

Once approved, a legal document, or “Work-Sharing Agreement”, is developed by Service Canada. The document becomes legally binding once it has been signed by the authorized employer representative, employee representatives and Service Canada representatives.

After a Work-Sharing agreement has been activated, Service Canada staff will ensure that the agreements are being carried out in compliance with regulations. When necessary, this will involve on-site visits to ensure that regulations and agreements are being complied with. The extent and nature of this monitoring activity varies depending upon the circumstances involved, and may be limited by available resources and staff workloads.

The Work-Sharing agreement details the terms and conditions for participation in the program, such as the duration of the agreement and the workers who will participate as the ‘unit’. Both the size and composition of the Work-Sharing unit, as well as the duration of the agreement may be amended by the employer by completing the appropriate Work-Sharing documentation.

Extension of a Work-Sharing Agreement can occur but it is not automatic. All requests for an extension must be submitted by the employer at least 30 days prior to the end date of their Work-Sharing agreement, and subsequently assessed and approved by Service Canada. The request for an extension must provide reasons why recovery was not achieved and must demonstrate a continued reduction in business activity that would result in the layoff of one or more employees. The employer must provide an updated recovery plan outlining the progress to date, with a list of activities that will take place during the extension period that will lead to normal working hours by the end of the agreement.

Upon completion of the Work-Sharing agreement, the Program Officer completes a close-out report summarizing the key outcomes.

1.6 Temporary measures

Recognizing the level of uncertainty employers and workers faced during the 2008-2009 recession, the Government introduced temporary changes to the Work-Sharing program to mitigate the effects of the recession on workers and employers.

Specifically, Budget 2009 introduced temporary measures which included extending the duration of agreements by 14 weeks to a maximum of 52 weeks, increasing access to the program through greater flexibility in the qualifying criteria and streamlining processes for employers. This included eliminating the requirement for employers to outline specific steps, including time lines and benchmarks, which would be taken during the life of the agreement to increase business and alleviate the work shortage. Rather, the focus for the employer was to provide steps they would take to remain viable during the timeframe of the agreement in order that recovery would be achieved as the economy strengthened, and employers were permitted to enter into new Work-Sharing agreements involving the same group of employees immediately after the end of a preceding Work-Sharing agreement instead of having to wait for a “cooling-off” period equal to the total length of time the previous Work-Sharing agreement was in place before re-applying. Budget 2009 temporary changes were in effect from February 1, 2009, to April 3, 2010.

In recognition of continuing economic uncertainty, Budget 2010 extended the temporary measures introduced in Budget 2009 by allowing employers with existing or recently terminated agreements to extend their Work-Sharing agreements up to an additional 26 weeks, to a maximum duration of 78 weeks. Previously, firms would have had to wait for the length of time of their original agreement before entering into a new one. The greater flexibility in qualifying criteria also remained in place for new Work-Sharing agreements. The Budget 2010 temporary changes were in effect until April 2, 2011.

To assist employers who continued to face challenges, Budget 2011 announced an additional extension of up to 16 weeks to employers with active or recently terminated Work-Sharing agreements. This temporary measure ended on October 29, 2011. In addition to these temporary measures, Budget 2011 introduced new permanent policy adjustments to make Work-Sharing more flexible and efficient to employers. Changes included a simplified recovery plan that no longer required employer’s business history, a detailed comparison of the company’s sales and production costs over the past two years, specific information on the cause of the work shortage specific to the business and the economic recession, and a description of any measures taken by the employer before applying for the program to remain viable during the recession. Also, where a significant community impact is relevant, greater consideration of local labour market conditions is given in the assessment of the application.

Other permanent policy changes included more flexible utilization rules, such as reducing the minimum expected work reduction criteria from 20% to 10%, technical amendments to program administration, and special measures for streamline approval processes when responding to disasters and states of emergency.

Reflecting slower than anticipated global growth during the first half of 2011, the November 2011 Economic and Fiscal Update announced an additional temporary extension of 16 weeks for employers in active, recently terminated or new agreements who still needed support. This temporary measure ended on October 27, 2012.

There were also changes to the dollar value of agreements and their associated level of approval. National Headquarter is responsible for reviewing applications or extensions for Canadian Employment Commission (CEIC) approval when they are estimated to exceed the following amounts, depending on submission dates:

- over $600,000, before February 1, 2009

- over $900,000, February 1, 2009 to April 2, 2011

- over $600,000, as of April 3, 2011

Regional offices are responsible for approval of applications or extensions when they are estimated to exceed $300,000 ($450,000 between March 3, 2009 and April 2nd 2011) but are below the amounts specified above. Otherwise, local offices are responsible for full administration, including approval of agreements below $300,000. Directors at Service Canada Centers have approval authority up to $300,000, and managers at Local Offices have approval authority up to $150,000.

2. Key findings

2.1 Continued need for the program

2.1.1 Need for the Work-Sharing Program

The Work-Sharing Program is generally seen as responding to employers’ and employees’ needs. Surveyed Work-Sharing employee representatives indicated that the program enables firms to adapt to economic recessions or sector based fluctuations, and this in turn, enables them to retain their employees.

Similarly, most firm representatives interviewed believed there is a need for the program, saying that regular layoffs would have occurred in the absence of the program. They explained that work reductions caused by business downturns from the recession triggers a need for the program. They also identified sector specific factors reducing demand, and supply-side shifts temporarily interrupting the availability of inputs, as creating a demand for the program. They also explained that work reductions leading to the loss of skilled employees was their primary reason for applying.

Case file information reviewed supports employer statements that the Work-Sharing program is used for periods of cyclical slowdowns in business. Economic recession was the most frequently cited reason for applying to the program. Twenty percent of applicants indicated a decline in business activity of 10-19%, and 67% indicated a decline of 20% or more, highlighting the impact the recession had on their business activity.

From the program delivery aspect, program officers acknowledge that the program is responsive to employer’s needs, working to reduce and avoid potential layoffs and assist companies in retaining skilled workers who would be costly to replace.

Review of international policies shows that work-sharing programs are often grouped in the broad category of Short-term Compensation (STC) programs. STC programs are present in Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Hungary, Switzerland, and the United States as part of their state run UI program.

Internationally, the rationale for a work-sharing program is to reduce the number of lay-offs, thus reducing the number of workers who may become unemployed when firms face temporary downturns. When facing a decline in normal level of business activity, firms may more likely lay off workers if they are eligible to receive unemployment insurance benefits rather than engage in other workplace practices such as adjusting their employees’ working schedules. Work-sharing help mitigate the risk of lay-offs and helps employers retain workers by leveraging benefits under the EI program.

Policy comparisons between the aforementioned countries reveal many similarities, but also many differences. To highlight just a few, in Canada, work reductions must be beyond the control of the employer. But in France, there are other circumstances where their program can be used. Circumstances include firms having difficulties finding adequate supplies in energy or other raw material, and firms preforming a transformation or restructuring of the enterprise. Furthermore, in France, and many other countries, direct subsidies are provided to employers who adopt Work-Sharing policies.

Some countries also offer flexibility in the way hours of work can be reduced. Reductions in working hours need not be uniform across the participating unit, and the way hours of work are reduced can vary: workers can work fewer days during each week, fewer hours per day, or they can rotate weeks of lay-off.

STC payments in the United States reduce workers’ entitlement to UI benefits dollar-for dollar if they are subsequently laid off, and employers from whose employees’ receipt of benefits exceed premiums paid are charged higher premiums for the use of the STC program, which differs from Canada’s Work-Sharing program. The literature review referenced in Appendix I provides greater detail on the international comparison of Canada’s Work-Sharing policies.

2.1.2 Need for Work-Sharing adjustments during the 2008-2009 recession

The Work-Sharing program is designed to temporarily help employees and employers adjust to economic recessions. If the economy slows down for an extended period of time, then most firm representatives agreed that in this context, the longer benefit periods made sense. From an employee standpoint, all respondents considered that the program modifications in response to the 2008-2009 recession were a good idea and the majority felt these changes helped keep people employed.

Program officers interviewed acknowledged that without the easing of the requirements and the extended length of support, many companies would not have survived. This would have caused a greater strain on EI benefits and further reduced any future potential for jobs and local economic growth. From the international evidence, most countries similarly made changes to their Work-sharing programs in response to the financial crisis. For many, similar to Canada, this included extending the maximum duration of the benefits and easing the admission requirements. Table 1 summarizes the changes for selected countries during the 2008-2009 recession.

| Countries | Relaxed admission requirements | Extension of benefit period | Increased replacement rate | Increased subsidies to employers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | yes | yes | no | no |

| Belgium | no | yes | yes | no |

| Canada | no | yes | no | no |

| France | no | yes | yes | no |

| Germany | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Japan | yes | no | no | yes |

| Republic of Korea | yes | no | no | yes |

| Netherlands | no | no | no | yes |

| Switzerland | no | yes | no | yes |

Sources Footnote 3 Vroman and Brusentsev (2009) and European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2009).

2.2 Alignment with government priorities

Temporary changes to the Work-Sharing program were first introduced in 2009. In the 2009 Budget Plan Footnote 4 , the Government’s objective was “strengthening benefits for Canadian workers (…) so more Canadians can continue working.” This was accomplished by extending the maximum length of time workers can receive benefits and by temporarily increasing access to the program through greater flexibility in the qualifying criteria and streamlining the process for employers. In doing so, the program kept more Canadians actively participating in the labour market.

Budgets 2009, 2010 and 2011 were created to support Canadians affected by the recent short-term economic recession. In a similar regard, the Work-Sharing program is designed to assist employees and employers temporarily, by providing them short-term assistance while the economy recovers. The temporary changes to the Work-Sharing program and the awareness the program received from the Budget Plans allowed for more Canadians to receive assistance during the difficult economic times.

2.3 Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities

The Government of Canada is responsible for Part I of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act. The provision of EI benefits under Part I of the EI Act support ESDC’s Strategic Outcome of: A skilled, adaptable and inclusive labour force and an efficient labour market.

Part I of the EI program provides temporary financial assistance to workers who have lost their job through no fault of their own while they look for work or upgrade their skills. Work-Sharing provides income support in the form of employment insurance benefits to eligible workers who work a temporarily reduced work-week while their employer recovers. The goal is for all the participating employees to return to normal working hours by the end of the term of the Work-Sharing agreement. During economic recovery, the Work-Sharing program creates an efficient labour market transition, as the program allows companies to retain their skilled employees so that they can quickly ramp up production when business levels return to normal.

2.4 Achievement of expected outcomes

2.4.1 Participation in the Work-Sharing program

The Work-Sharing program is highly counter cyclical. Program participation is high when economic growth is low, and as shown in Figure 1, when unemployment rises, so does the number of Work-Sharing claims.

Textual description of figure 1 - Number of Work-Sharing claims and change in unemployment

From fiscal year 2000 to 2013, figure 1 displays from the left axis, the number of Work-Sharing claims displayed as a histogram, and from the right axis, the percentage change in unemployment over time.

The figure shows the counter cyclicality of program usage. The number of Work-Sharing claims increased in years when there was an increase in the percentage change in unemployment, and similarly decreased in years when there was a decrease in the percentage change in unemployment.

The number of claims peaked in 2009-10 with close to 140,000 claims, at the same time, the percentage change in unemployment was over 25%. In contrast, since 2012–13, the number of claims each year has been below 20,000, and the percentage change in unemployment has been below 5%.

The counter cyclical use of Work-Sharing can also be seen in Table 2 which presents program participation and expenditures by fiscal year. Participation and expenditures peaked in 2009-10 following the economic recession when new Work-Sharing claims were at a high of about 139,000 and expenditures amounted to $235 million (2007-08 dollars). Footnote 5 Alternatively, participation and expenditures were lowest in mid-2000s, with little more than 10,000 new claims and $11 million in expenditures (2007- 08 dollars).

| Fiscal year | New Work-Sharing claims | Employment ('000) | Work-Sharing claims % of employment | Work-Sharing benefits paid (Nominal dollars) | Work-Sharing benefits paid (2007-2008 dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | 17,270 | 14,819 | 0.12 | $17,603,128 | $20,152,408 |

| 2001-02 | 47,835 | 14,985 | 0.32 | $50,199,252 | $56,387,812 |

| 2002–03 | 16,791 | 15,426 | 0.11 | $14,759,298 | $16,165,715 |

| 2003–04 | 31,248 | 15,723 | 0.20 | $24,955,856 | $26,870,370 |

| 2004–05 | 11,932 | 15,971 | 0.07 | $10,812,629 | $11,438,909 |

| 2005–06 | 11,368 | 16,188 | 0.07 | $11,183,319 | $11,556,000 |

| 2006–07 | 10,452 | 16,513 | 0.06 | $11,534,991 | $11,716,599 |

| 2007–08 | 14,735 | 16,896 | 0.09 | $20,535,544 | $20,458,824 |

| 2008-09 | 77,220 | 17,038 | 0.45 | $173,185,968 | $169,085,632 |

| 2009-10 | 138,935 | 16,828 | 0.83 | $243,384,608 | $235,438,560 |

| 2010-11 | 22,743 | 17,121 | 0.13 | $29,117,222 | $27,737,292 |

| 2011–12 | 25,539 | 17,344 | 0.15 | $31,723,844 | $29,476,278 |

| 2012–13 | 15,479 | 17,579 | 0.09 | $20,720,738 | $8,962,012 |

Table 2 also shows Work-Sharing take up as a percentage of employment. Work-Sharing participation has been consistently low, never accounting for more than one percent of employment. But its trend still conveys the programs counter cyclicality. Work-Sharing claims as a percentage of employment reached a maximum of 0.83% in fiscal year 2009-10, and participation was lowest in 2006-07, accounting for 0.06% of employment.

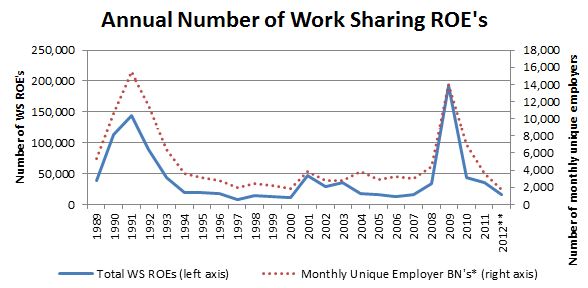

Similarly, Figure 2 provides the annual number of Records of Employment (ROEs) issued for the purpose of Work-Sharing during the period of 1989 to 2011. Again, program participation was highly counter-cyclical. Work-Sharing ROEs peaked during the recessions of 1990-1991 and 2009-2010, and, to a much lesser degree, in 2001. Between those periods, annual participation was consistently low.

Textual description of figure 2 - Annual number of Work-Sharing records of employment (ROEs)

From fiscal year 1989 to 2012, figure 2 displays from the left axis, the annual number of Work-Sharing Records of Employment represented as a solid line, and from the right axis the number of monthly unique employer’s represented as a dotted line.

Over time, the number of Work-Sharing Records of employment follows a similar pattern to the number of monthly unique employers, both peaking during the economic downturns of 1990-1991 and 2008-2009. In 1990-1991, close to 150 thousand records of employment were issued for work-sharing, and in 2008-2009, close to 200 thousand records of employment were issued for the purpose of Work-Sharing. However, in 1990-1991, over 14,000 unique employers were identified per month, compared to less than 14,000 unique employers per month in 2008/2009. This suggests that the average size of Work-Sharing agreements increased per participating employer following the 2008-2009 recession.

There is no evidence to suggest that the program’s take-up, in terms of the number of employees claiming Work-Sharing, increased beyond what could be expected from its typical counter cyclicality. However, during the 2008-2009 recession, the number of employees per agreement increased. The dotted line of Figure 2 provides the monthly number of unique employers, summed for each year. The number of unique employers follows a similar pattern to the total number of employees. However, the number of employees was higher relative to the number of employers during the 2009-2010 peak as compared to the 1990-1991 peak, suggesting an increase in the average agreement size.

2.4.2 Characteristics of Work-Sharing participants

Analysis of the EI administrative data shows that, in all years, men made up the majority of the Work-Sharing program participation, accounting for around 69% of claims since the year 2000. Women’s participation never reached above 38% of claims and was at its lowest point in 2008 and 2009, when Work-Sharing participation was at its highest.

In terms of age, the vast majority of Work-Sharing participants are in the working age category, between 25 and 54. This age group remained relatively constant at around 79%. Workers aged 55 and older made up an increasingly larger share of the users while youth participation declined, but both remained relatively small compared to the prime working age category. In terms of percentage of claims, Ontario has consistently been the largest user of the Work-Sharing program. In 2008-09, it accounted for more than half of all new claims. Quebec has consistently been the second biggest user, and when comparing regional participation relative to the employment level, since the year 2000, Quebec is the only province to be systematically higher than the Canadian average.

During the 2008-2009 recession, participation in British Columbia also increased above the Canadian average. Additional statistical analysis found that during the recession, for a given employee requiring assistance from the EI program, firms in Ontario and British Columbia were the most likely to have employees claiming Work-Sharing benefits over regular EI benefits.

In the industrial sector, the manufacturing industry has consistently been the largest user of the Work-Sharing program, typically accounting for two thirds to three quarters of the programs use. The service sector has been the second biggest user of the program, but seldom accounts for more than one fifth of new yearly claims.

The majority of program officers indicated that the Work-Sharing program has traditionally been a good fit in supporting manufacturing companies. They identified the characteristics of manufacturing companies as large and medium-sized organizations, with multiple people completing similar tasks and job responsibilities. They also explained that these companies typically have clear cut and repetitive production schedules, producing goods with easily quantifiable inputs and outputs, and workers that are primarily trained on the job.

Similarly, evidence from the file review suggested that manufacturing employees were often listed as doing jobs very similar in nature from one another, and therefore, hours of labour are easily substituted between employees, making them a good fit for the Work-Sharing program. However, a large proportion of the workforce is now employed in non-manufacturing type jobs. Based on Statistics Canada labour force data and ESDC’s records on Work-Sharing applications, the manufacturing sector accounts for 80% of Work-Sharing applicants but only 10% of Canada’s total labour force. This disconnect between program usage and the size of the manufacturing sector in the economy suggests that there may be missed opportunities in supporting non-manufacturing sectors.

Outside of the industrial sector, most programs officers questioned the continued relevance of Work-Sharing in an economy that includes a growing number of information and service based industries. They identified the service industry, including retail, real estate, professional companies (lawyers, architects), the financial industry, and the non-profit sector as underutilizing the program. Smaller firms, those with specialized and varied job descriptions and those which are not able to have employees ‘share’ responsibilities were all identified as not generally using the program to a significant degree.

The officers indicated that the biggest barrier to the program uptake by these sectors is the application guidelines favored towards firms with simple production processes and where production inputs and outputs can be easily identified for the purpose of applying to the program. They explained that firms in the underutilized sectors are not as able to identify specific production targets or recruitment-based activities that are required to meet the current guidelines.

However, employment may be more cyclical in the manufacturing sector compared to other industries. There was also evidence from the files reviewed that firms were frequently engaged in work-sharing practices and/or planning to engage in work-sharing practices, regardless of receiving assistance through the Work-Sharing program. In approximately one fifth of the case files reviewed that contained a recovery plan, employers indicated they had already begun work-sharing arrangements prior to applying to the program. When looking only at manufacturing firms, this number jumps to over 68%. This suggests that work-sharing practices are perhaps more natural in the manufacturing sector, and is not something that can be easily encouraged in other industries by altering program requirements.

2.4.3 Program utilization

Analysis of EI administrative data shows that the average work reduction per fiscal year has been relatively consistent throughout the years, averaging approximately 28%. Not surprisingly, the average weekly benefits paid have been consistent as well. But, the average length of claims rose significantly during the 2008-2009 recession. Table 3 shows that the average duration of claims have typically been around 17.5 weeks, but increased to 39.4 and 35.6 in 2008-09 and 2009-10 respectively. This coincides with the 2008-2009 recession but also the period in which the maximum agreement lengths were temporarily increased. This suggests that employers made use of the temporary Work-Sharing measures during the recession.

| Fiscal year | Average work reduction (%) | Average duration (weeks) | Average weekly benefits (Nominal $) | Average weekly benefits (2007–08 $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | 29.2 | 17.1 | 59.6 | 68.2 |

| 2001-02 | 26.8 | 18.9 | 55.7 | 62.5 |

| 2002–03 | 27.6 | 16.2 | 54.2 | 59.4 |

| 2003–04 | 26.9 | 16.3 | 49.0 | 52.7 |

| 2004–05 | 28.5 | 15.8 | 57.4 | 60.7 |

| 2005–06 | 28.0 | 16.6 | 59.2 | 61.1 |

| 2006–07 | 29.0 | 18.4 | 59.9 | 60.8 |

| 2007–08 | 28.4 | 21.3 | 65.5 | 65.2 |

| 2008-09 | 28.6 | 39.4 | 57.0 | 55.6 |

| 2009-10 | 25.5 | 35.6 | 49.2 | 47.6 |

| 2010-11 | 27.1 | 21.9 | 58.5 | 55.8 |

| 2011–12 | 27.0 | 21.1 | 58.9 | 54.7 |

| 2012–13 | 27.6 | 21.1 | 63.4 | 58.1 |

Additional statistical analysis looked at the distribution of Work-Sharing claim durations. Table 4 provides the distribution of Work-Sharing claim durations, by fiscal year in which the claim started

| Fiscal year | 0-20 weeks | 21-26 weeks | 27-38 weeks | 39-60 weeks | 60-78 weeks | 79-104 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989–90 | 71% | 14% | 15% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1990-91 | 59% | 25% | 14% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1991–92 | 63% | 24% | 12% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1992–93 | 64% | 24% | 12% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1993–94 | 71% | 21% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1994–95 | 69% | 18% | 11% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1995–96 | 70% | 19% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1996–97 | 71% | 19% | 9% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1997–98 | 68% | 20% | 11% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1998–99 | 61% | 21% | 16% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 1999–00 | 76% | 15% | 9% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2000-01 | 63% | 22% | 13% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 2001-02 | 57% | 25% | 18% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 2002–03 | 70% | 21% | 8% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| 2003–04 | 66% | 23% | 11% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2004–05 | 71% | 19% | 9% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2005–06 | 68% | 22% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2006–07 | 61% | 22% | 15% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| 2007–08 | 57% | 19% | 16% | 3% | 4% | 1% |

| 2008-09 | 28% | 17% | 10% | 23% | 14% | 8% |

| 2009-10 | 27% | 13% | 19% | 27% | 13% | 0% |

| 2010-11 | 50% | 25% | 14% | 10% | 1% | 0% |

| 2011–12 | 57% | 25% | 14% | 4% | 0% | 0% |

Notes: Percentages rounded to nearest whole number

Table 4 shows that from 1989-90 to 2005-06, the distribution of Work-Sharing claims by weeks was fairly stable and there was only a small increase in the average duration in the years with an economic recession. During the 1990-1991 recession, around 60% of claims lasted 20 weeks or less, and around 85% lasted 26 weeks or less. So, in spite of the economic recession, most claims during 1990-1991 recession were potentially not constrained by the official maximum of 38 weeks. Although no two economic recessions are perfectly comparable, as they can each differ in their length and severity, as well as in the particular industries they impact, it is still noteworthy that 45% of claims starting in 2008 lasted longer than 38 weeks. The analysis suggests that the shift in the distribution of claim durations is likely greater than can be explained by the economic recession alone, and can be at least partially attributable to the temporary program measures introduced in 2009 to allow employers to extend their Work-Sharing agreements in order to have more time to work towards recovery.

Regarding the new provision allowing for laid-off workers to be called back to employment as part of a Work-Sharing agreement, the evaluation found that the delivery of the new provision varied between officers from different regions. Some indicated they proactively discussed with the firm the possibility of calling back laid-off workers while others assumed it was done only if it was part of the recovery plan, such that the firm needed the skills of the laid-off employee to recover. One region indicated they worked with employers prior to the onset of the final approval to ensure that the names of employees who could be potentially called back would be included in the agreement, thus giving the employer the flexibility to meet production demands without delay.

According to most program officers interviewed, hiring of new employees does occur during the period of Work-Sharing agreements: two interviewees said it happens rarely, and two others indicated that it happens regularly. The reason provided for hiring new employees was to introduce a skill level necessary for the recovery plan that was not available from within the affected works listed in the agreement. Respondents explained that some employers had to hire new employees to increase production demands as the recovery plan was implemented and others had to replace affected workers who left for employment in more stable organizations.

Overall, it was felt that employers were using the provision in an appropriate manner. Additional evidence from the files reviewed confirmed that new employees were being hired while companies had active Work-Sharing agreements but this was not a frequent occurrence: 8.2% of the files approved contained evidence of employers bringing on additional resources during an agreement period. Similarly, the justification provided was that new employees were brought on to support recovery efforts such as opening new sales territories and selling new products.

2.5 Impacts

2.5.1 Averted layoffs

More than 75% of firm representatives said that the costs of lay-offs in terms of subsequent recruitment and training would have been substantial and that avoiding this was the principal benefit of applying to the program. However, estimating the number of layoffs averted is not an easy task. The best estimates are based on a number of assumptions and often only consider layoffs averted during the period of agreement. If layoffs occur after the termination of the agreement, these layoffs are postponed. As this is a key issue to determine the success of the program, the department continues its analysis through studies produced for the annual EI Monitoring and Assessment Report.

The ensuing discussion will cover the methods, and their limitations, used to estimate the number of layoffs averted by the program, followed by the results of a statistical analysis which considers the share of work sharing agreements that can only be considered as postponements of layoffs (i.e., the number of layoffs occurring within six months of agreement terminations (for more details see the peer reviewed technical studies referenced in Appendix I)). Some additional evidence and discussion regarding the impact the Work-Sharing program had on averting layoffs, and the effects of the temporary Work-Sharing measures then proceeds.

While important limitations and alternative measures will be discussed further below, the simplest and most common method used to estimate the impact of Work-Sharing on lay-offs is one that assumes a perfect substitution between one hour of work reduction through Work-Sharing and one hour of work reduction through lay-offs. In other words, if employers reduced employee hours by 30% under Work-Sharing, it is assumed that they would have laid off 30% of the work unit if Work-Sharing were not available. With this method, we assume the average work reduction would be equal to the average labour force reduction.

Multiplying the average work reduction by the number of Work-Sharing claims provides an estimate of the number of layoffs averted and postponed by the program. The results are summarized in table 5 below. Since 2000-01, the number of layoffs averted and postponed by the Work-Sharing Program ranged from a low of 3,000 in 2006-07 to a high of 35,500 in 2009-10 during a recessionary period. Clearly, just as program participation is counter cyclical, so are the layoffs averted and postponed by the program. This is largely attributed to the consistency of the average work reduction over the years, averaging 28%.

| Fiscal year | Number of Work-Sharing claims | Percentage of average work reduction | Estimated layoffs averted and postponed1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | 17,270 | 29.2% | 5,000 |

| 2001-02 | 47,835 | 26.8% | 13,000 |

| 2002–03 | 16,791 | 27.6% | 4,500 |

| 2003–04 | 31,248 | 26.9% | 8,500 |

| 2004–05 | 11,932 | 28.5% | 3,500 |

| 2005–06 | 11,368 | 28.0% | 3,000 |

| 2006–07 | 10,452 | 29.0% | 3,000 |

| 2007–08 | 14,735 | 28.4% | 4,000 |

| 2008-09 | 77,220 | 28.6% | 22,000 |

| 2009-10 | 138,935 | 25.5% | 35,500 |

| 2010-11 | 22,743 | 27.1% | 6,000 |

| 2011–12 | 25,539 | 27.0% | 7,000 |

| 2012–13 | 15,479 | 27.6% | 4,500 |

1Estimated layoffs averted or postponed are rounded to the nearest 500

As indicated above, there are limitations with this methodology. For one, the assumption of perfect substitution between methods of work reduction can be incorrect. For example, if each individual’s average productivity increases with the number of hours they work, the production of two workers working 50% of their hours would be lower than one worker working full-time. Under this scenario, the reported number of layoffs averted above would also be overstated. On the other hand, if two workers are complementary factors in a production process, the production of two workers working half of their full-time hours would be greater than one worker working full-time. Under this scenario, the reported number of layoffs averted above would be understated.

Either way, the number of jobs saved is always less than the number of participants in the program, and therefore as Boeri (2011) points out, this implies a deadweight cost. Footnote 6 Similarly, to avoid layoffs, some employers will maintain full staff when faced by work shortages, even in the absence of a Work-Sharing program. This would suggest the estimates above are overstated and represent another form of deadweight cost. Hijzen and Venn (2011) estimate that this deadweight could have been as high as one-third of participants, on average for countries they studied during the 2008-2009 recession. Footnote 7 Furthermore, the methodology above does not consider possible displacement effects. If the program preserves jobs that are not viable and delays rather than averts layoffs, then this could represent a barrier to job creation by firms with the potential to grow.

For these reasons, the OECD suggests considering additional steps to mitigate deadweight and displacement costs by ensuring that only firms experiencing temporary shortages of work participate, and making firms bear a part of the wage costs for the hours not worked, or requiring firms to repay all or part of the subsidy if the employee is laid off after the program ends Footnote 8 .

However, it is important to note that these suggestions would likely have an adverse impact on program take-up, and considering program participation is already very low in Canada, the benefit to the programs overall cost-effectiveness would be minimal. Also, as previously noted, although it is true that labour markets should be sufficiently flexible in the presence of structural adjustments, excessive mobility in response to temporary shifts in the demand for labour is inefficient, because the cost of replacing experienced employees can be substantial. When a firm’s normal production levels return and laid-off workers have sought employment elsewhere, the costs and delays of training and recruiting new employees can negatively impact a company’s competitiveness and put them at risk of an unsuccessful recovery, and potentially the firm’s closure.

For the employee, there are also significant costs involved with being unemployed that must be considered. Not only can the loss of income be substantial, but the employees overall wellbeing is at stake as the negative psychological impacts associated with being laid-off are well documented Footnote 9 . Furthermore, as employees search for new jobs during a period of reduced business activity, finding new employment can be difficult and can take additional time. The longer employees remain out of work, the more their skills deteriorate, and the more they risk becoming long-term unemployed. This could be a significant added cost to the EI account, especially when compared to the Work-Sharing alternative, which represents a relatively small share of total EI expenditures. Reid (1983) Footnote 10 further argues that work sharing can be an effective transitional mechanism for employees searching a new job. He explains that it can be advantageous for workers to be employed while searching for work as it removes the stigma of unemployment which might influence prospective employers. Furthermore, Work-Sharing would provide a higher level of income during the job search process and reduce the negative psychological impacts of unemployment, which he explains can sometimes be more tragic than the economic consequences.

The program file review used another method to estimate the number of layoffs averted. In the program files are estimates, provided by employers at the time of application, on the number of layoffs that would occur if their application were to be refused. Also contained in the files is the actual number of layoffs that occurred during the agreement. The difference between these two numbers provides another estimate of layoffs averted.

Based on 226 approved Work-Sharing files reviewed, it is estimated that 50% of claimants averted layoffs for a total of about 1,800. However, because employers tend to overstate the number of layoffs that would occur if their application were to be refused at the time of application, estimates using this methodology are likely to be overstated. During interviews, employers recognized that it is challenging to calculate the precise number of layoffs averted by Work-Sharing, because their economic circumstances change during the life of the agreement.

When considering the period after the agreement, statistical analysis was conducted using EI administrative data on Work-Sharing claims and layoffs 6 months after the claim termination. Table 6 shows that the number of employees on a Work-Sharing agreement, laid off within 6 months of their agreement follows a counter-cyclical pattern. Approximately 1,300 layoffs occurred following agreement terminations in the years 2004-05, 2005-06 and 2006-07, whereas in 2008-09 and 2009-10, approximately 11,000 workers were laid-off following agreement terminations.

| Fiscal year | Number of Work-Sharing claims | Estimated layoffs averted and postponed | Percent of layoffs observed | Number of layoffs observed | Estimated net layoffs averted | Proportion of net layoffs averted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-01 | 17,270 | 5,000 | 19% | 3,281 | 1,719 | 34% |

| 2001-02 | 47,835 | 13,000 | 9% | 4,305 | 8,695 | 67% |

| 2002–03 | 16,791 | 4,500 | 11% | 1,847 | 2,653 | 59% |

| 2003–04 | 31,248 | 8,500 | 8% | 2,500 | 6,000 | 71% |

| 2004–05 | 11,932 | 3,500 | 11% | 1,313 | 2,187 | 62% |

| 2005–06 | 11,368 | 3,000 | 11% | 1,250 | 1,750 | 58% |

| 2006–07 | 10,452 | 3,000 | 13% | 1,359 | 1,641 | 55% |

| 2007–08 | 14,735 | 4,000 | 20% | 2,947 | 1,053 | 26% |

| 2008-09 | 77,220 | 22,000 | 14% | 10,811 | 11,189 | 51% |

| 2009-10 | 138,935 | 35,500 | 8% | 11,115 | 24,385 | 69% |

| 2010-11 | 22,743 | 6,000 | 9% | 2,047 | 3,953 | 66% |

| 2000-01 2010-111 |

36,412 | 9,818 | 11% | 3,889 | 5,930 | 60% |

1Percentages are weighted averages

Table 6 also provides an estimate of the net layoffs averted by subtracting from the initial estimate of layoffs averted and postponed, the observed number of layoffs that occurred following agreement terminations. If we take the ratio of this estimate with the estimated layoffs averted and postponed, we find that from 2000-01 to 2010-11, using a weighted average, 60% of layoffs initially avoided during the agreement were avoided for at least 6 months following the agreement termination. Both methodology and the estimates of layoffs averted are consistent with the 2004 evaluation of the Work-Sharing Program Footnote 11 . In comparison, the 2004 evaluation found that on average from 1990-91 to 2001-02, 49% of lay-offs initially avoided during the agreement, were further avoided for at least 26 weeks following the agreement termination Footnote 12 .

If one considers the normal rate of attrition and turnover that occurs naturally, business cycle aside, this would explain some of the layoffs that occur after the termination of a Work-Sharing agreement. Furthermore, if layoffs do occur after the termination of a Work-Sharing agreement, Reid (1982, 1983) argues that this does not necessarily represent a misuse of the program. He explains that Work-Sharing still provides firms with a mechanism to immediately reduce working hours, and with time, working hours can gradually be increased as the workforce shrinks with normal attrition, saving the firm the costs of hiring and training that would have been associated with normal turnover. He also argues that Work-Sharing is not intended to affect the overall hours of employment in the economy, the overall amount of leisure, or the overall amount of EI benefits paid. It is intended to affect the distributions of these factors Footnote 13

The review of program files also provided evidence as to the likelihood of a firm completely shutting down after the termination of a Work-Sharing agreement. The evaluation found that this happened rarely for firms of over five employees on a Work-Sharing agreement and virtually never for firms with over 25 employees on a Work-Sharing agreement. This suggests that the program is not delaying closure of failing businesses, but rather supporting companies who are facing work-shortages due to temporary business downturns.

During employer interviews, most said they did return to normal levels of business after the termination of their agreement. There were also a few that stated they returned to full production before the agreement expired. Further evidence from the review of program files confirms that 74% of the 226 approved agreement files reviewed reported returning to normal levels of business by the end of the agreement.

When employers were asked about what contributing factors led to the recovery, most referred to normal level of business being regained as a result of the return for the demand of their products. But had the Work-Sharing program not been available, employers noted they would have been concerned about permanently losing laid-off workers. Some did therefore attribute the program with helping them transition back to normal production volumes while avoiding the costs and delays from hiring and training.

Finally, to test for the effect of the budget changes on the likelihood of being laid off, a statistical analysis used the two short periods between Budgets 2010 and 2011 where the program reverted back to its 38 week agreement maximum. Although it is true that three successive budgets and an economic update allowed for extensions to the maximum agreement lengths, the program reverted back to its 38 week agreement maximum between the expiry of the temporary measures under Budget 2010 on April 2, 2011 and the approval of Budget 2011 on May 29, 2011. Similarly, the Work-Sharing temporary measures of Budget 2011 expired on October 29, 2011, and the temporary measures under the 2011 Economic Update were not approved until December 23, 2011.