Summative Evaluation : Canada Student Loans Program, June 2011

Official Title: Summative Evaluation of the Canada Student Loans Program - June 2011

List of Abbreviations

- ASETS - Access and Support to Education and Training Survey

- CAG - Canada Access Grants

- CESP - Canada Education Savings Program

- CMSF - Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation

- CSFAA - Canada Student Financial Assistance Act

- CSG - Canada Study Grants

- CSL - Canada Student Loans

- CSLA - Canada Student Loans Act

- CSLP - Canada Student Loans Program

- DARS - Default and Recovery System

- DPR - Departmental Performance Report

- DRR - Debt Reduction in Repayment

- EIR - Extended Interest Relief

- HRSDC - Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

- ICCSFA - Intergovernmental Consultative Committee on Student Financial Assistance

- LAD - Longitudinal Administrative Database

- LFS - Labour Force Survey

- NARS - Need Assessment Reports

- OECD - Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OSFI - Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

- OSAP - Ontario Student Assistance Program

- PCP - Pre-Consolidation Program

- PSE - Post-secondary education

- RAP - Repayment Assistance Plan

- RAP-PD - Repayment Assistance Plan for Borrowers with a Permanent Disability

- RESP - Registered Education Savings Plan

- RMAF - Results-based Management and Accountability Framework

- SFA - Student Financial Aid

- SHS - Survey of Household Spending

- YITS-A - Youth in Transition Survey, cohort A

Executive Summary

The Summative Evaluation of the Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP) has been undertaken over the 2006 to 2010 period using an approach of conducting a set of small studies during each year of the evaluation. This report provides a summary of the results of 32 studies conducted for the summative evaluation. The studies used a variety of methods including literature reviews, international comparisons, surveys, focus groups, key informant interviews, administrative data analyses and econometric analyses. As well, other external studies were used to complement the 32 studies completed specifically for this evaluation.

Evaluation Findings

Program Rationale

The rationale for the CSLP is still valid because the benefits to society of having an educated population go beyond the economic costs and because financial barriers would otherwise exist for many more students without the program, especially those from low-income families. Students are often unable to borrow from the private sector for their post-secondary education (PSE) due to the lack of collateral, as well as the inability of financial institutions to assess future income. The literature review and the international comparison provided evidence that the credit constraints are sufficient to warrant government action. As well, key informants were unanimous on the need for a program in some form.

The two main arguments for action by the federal government in this area are equality of access across the country and historical precedent. However, the rationale for some detailed features of the CSLP requires a re-examination, specifically the loan system for part-time students.

Needs Assessment

Although the needs assessment used for the CSLP is complex, most key informants and focus group participants agreed that those who need a loan get a loan. Analysis conducted for the evaluation demonstrated that the current allowances for student expenses are adequate in terms of meeting average monthly total student expenditures for the majority of students (66%). However, a number of areas were identified for improvement: 1) although some changes have been made to the parental contribution rules, further adjustments appear to be needed; 2) consider ways to improve student comprehension of the needs assessment process; and 3) improving the quality of the needs assessment data files.

Post-Secondary Education (PSE) Access

According to the 2007-2008 CSLP Annual Report the mandate of the CSLP is to "promote access to post-secondary education through the provision of financial assistance in the form of loans and/or grants to qualified students based on financial need, regardless of province or territory of residence." The program appears to be achieving this objective. The literature review, key informants and empirical studies demonstrated that the program is reducing financial constraints. Five studies provided estimates of the impact of the CSLP on PSE access. Overall, the estimates showed that each $1,000 increase in student loans limits increases the enrolment of low-income students by 0.4 to 1 percentage points. Non financial barriers continue to play a key role in explaining PSE access issues.

Debt Repayment

The average student loan debt at consolidation time was $9,348 in 1998-1999, increased slightly to $9,655 in 2000-2001, and increased further to $12,881 by 2007-2008. Accounting for inflation (which averaged 2.4% over this period) this represents an increase in average student loan debt of about $1,030. Although the majority of student borrowers are able to repay their loans with or without government assistance, approximately 16% of borrowers defaulted in 2007-2008 (i.e. were behind on their loan repayment by 3 or more months following the loan consolidation date). This was down by more than ten percentage points from the earlier part of the decade. The literature review and analysis of CSLP administrative data indicated that many factors influence the default rate such as scholastic results, graduation rates, employment income, unemployment rates, debt levels, gender, age, and institution characteristics.

The changes to the Interest Relief and Debt Reduction in Repayment provisions in 1997, 1998 and 2003 generally helped to reduce the default rate. Although key informant interviews and focus groups indicated that these two provisions (subsequently replaced by the Repayment Assistance Plan in 2009) helped lowered lower the default rate, the use of a more pro-active pre-consolidation counselling approach could be further explored by the department to help borrowers understand debt management measures and to further reduce the default rate.

Management Response

Introduction

The benefits associated with high rates of post-secondary education (PSE) are well established. PSE provides Canadians with access to better job prospects and opportunities for personal growth. Canadians understand the importance of post-secondary education in today's competitive world; in fact, Canada leads all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in the proportion of the population with a college or university education.

This impressive achievement is, in part, the result of the Government of Canada's commitment through the Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP) to ensure that Canadians are able to access PSE. The CSLP provides government funded loans and grants to eligible Canadians pursuing a post-secondary degree, diploma or certificate program at a designated educational institution. The main clients are low- and middle-income Canadians, students with disabilities, and students with dependents. The CSLP also provides assistance to borrowers who are having difficulties repaying their student loans.

Since the inception of the CSLP in 1964, the Government of Canada has provided close to $32 billion in student loans to more than 4.3 million students. According to the Office of the Chief Actuary Footnote1 , approximately 36% of all full-time PSE students in the nine provinces and one territory that participate in the CSLP Footnote2 received a Canada Student Loan in the 2008-2009 loan year.

A summative evaluation of the CSLP was conducted between 2006 and 2011 and focussed on the loan period from 2000 to 2008. Since this evaluation period, there have been a number of significant initiatives announced by the Government of Canada to enhance student financial assistance. In Budget 2008, the Government of Canada announced a series of wide-ranging measures, which have subsequently been implemented:

- The Canada Student Grants Program that provides low- and middle-income students with consistent and up-front funding to help pay for PSE;

- The Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) that assists borrowers who are having difficulty repaying their loans by making it easier to manage their debt by paying back what they can reasonably afford. RAP replaced the Interest Relief and Debt Reduction in Repayment programs, and under this new plan, thousands of additional borrowers will qualify for assistance each year; and

- The Repayment Assistance Plan for Borrowers with a Permanent Disability (RAP-PD) is available to borrowers with a permanent disability having difficulty meeting their loan repayment obligations. Like RAP, RAP-PD makes it easier for eligible student loan borrowers to manage their debt by paying back what they can reasonably afford.

In addition to these initiatives, the Government of Canada has also introduced changes to increase support to full-time students in certain circumstances. In the past, full-time students received interest subsidies provided that they remained in school and were eligible to defer payments on their loans until six months after they completed their studies. However, in cases where students exceeded the maximum allowable number of weeks of student financial assistance, the student would be required to begin making payments on their student loans before they finished their studies. As part of Budget 2008, full-time student borrowers that reach their the maximum weeks of assistance are now able to continue their studies without having to begin repaying their loans until six months after they finish school.

With respect to part-time students, Budget 2008 included significant enhancements by more than doubling the maximum lifetime loan amount and improving the terms of repayment of student loans. Like full-time students, part-time students are now able to defer payment on their loan principal and accumulated interest until six months after their studies are complete. (Prior to this change, part-time students were responsible for making interest payments on their loans while in study.)

Given that these significant changes to student financial assistance occurred after the timeframe of this summative evaluation (2000 to 2008), a supplementary evaluation plan is being developed to capture the impact of these new initiatives.

In addition, the CSLP continues to work in collaboration with provincial and territorial partners to implement a number of initiatives to modernize the delivery of student financial assistance. These initiatives include a master student financial assistance agreement, electronic confirmation of enrolment, and a single on-line application for repayment assistance, all of which are designed to significantly simplify the process for the borrower throughout the student loan lifecycle.

Key Findings

Overall, the evaluation found that the rationale for the CSLP was valid and that there continues to be a clear need for the financial assistance it provides to students. The evaluation further concluded that the Program was achieving its objectives by reducing financial barriers, improving access to PSE, and addressing the financial needs of students by increasing loan limits and developing policies to support them in repayment.

We agree with these key findings and are pleased to present the following management response to the specific recommendations in the report. The CSLP Directorate within the Learning Branch of HRSDC has responsibility for proposed actions. The recommendations essentially pertain to four broad areas:

- Eligibility for Student Financial Assistance;

- Student Financial Assistance for Part-Time Study;

- Repayment following completion of PSE, and

- Default Management.

For purposes of clarity, HRSDC's responses to the recommendations outlined in the summative evaluation have been categorized using these four broad areas.

Recommendations

Eligibility for Student Financial Assistance

To qualify for a Canada Student Loan, a student must satisfy the criteria prescribed by the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act and Regulations, and demonstrate a financial need. This needs assessment process is undertaken on behalf of the Government of Canada by participating provincial and territorial student financial assistance programs. Among the elements that are considered during the needs assessment process are the student's category (single or married, dependent or independent), the student's PSE expenses (including tuition, fees, books, and living expenses) and their financial resources (including a student's income, savings and assets, parental or spousal contributions). Based on these criteria, a student's eligibility as well as the amount of student financial assistance is determined.

Recommendations 1, 5, and 6 of the evaluation report address specific issues with respect to needs assessment:

Recommendation #1: That CSLP look for ways to simplify the needs assessment process in order to help students better understand the process.

We agree with this recommendation. In collaboration with provincial and territorial partners, via the Intergovernmental Consultative Committee on Student Financial Assistance (ICCSFA), the needs assessment process is periodically reviewed to identify ways to further improve and simplify the process. ICCSFA is a federal-provincial body that meets regularly to examine policy and programming elements relating to student financial assistance in Canada.

Part of this collaboration centers around developing a series of communication tools for students to help them better understand the needs assessment process. For example, on-line calculators have been developed to assist students to estimate the amount of funding they can expect to receive so that they can plan for their education and the associated costs prior to submitting a student loan application. On-line application processes are also available to students to help them navigate though the application process. Financial aid offices at PSE institutions and provincial/territorial student financial assistance offices have the capacity to respond to student inquiries related to needs assessment.

Communication and outreach activities are undertaken to encourage students with financial need to apply for student assistance under the CSLP. Given the importance of understanding what obstacles may exist to prevent students from applying for support, HRSDC is currently conducting an experiment in fifty high schools in British Columbia with low secondary-to-post-secondary transition rates, to examine the impact of providing students with hands-on counseling on PSE options. Counseling includes support in completing applications for PSE admission and for student financial assistance. A final report on the results of this initiative is expected in 2012 and will enable the CSLP to examine the application process to ensure it is meeting the needs of applicants.

Recommendation #5: Although the needs assessment system seems to work well, the provincial uniform cost-of-living allowances should be rethought because some expenses (especially shelter) can vary significantly from the average provincial expenses, depending on whether students live in large urban centres, small urban centres, or rural communities.

We agree that the needs assessment system works well. In collaboration with our provincial and territorial student financial assistance partners, needs assessment criteria are reviewed by the Government of Canada on a regular basis so that adjustments may be considered to reflect increases in student costs over time.

The current CSLP methodology for calculating cost of living allowances within a province is based on the largest (most expensive) urban centre in each province. As noted in the evaluation report, this approach can result in students from low-cost regions of the province receiving cost of living allowances that exceed their actual needs. However, in our view, the administrative complexity and associated costs of introducing variable cost of living allowances within a province would more than offset any benefits.

Recommendation #6: Parental contributions were identified as an issue in the 1997 evaluation and in studies since that time. Although HRSDC has modified some rules related to parental contributions, evidence collected for the current evaluation indicates that some further adjustments should be made to the parental contribution rules.

We agree with this recommendation. Given that parental contributions are a key component in determining entitlement to student financial assistance, examination of issues in this area is undertaken on an ongoing basis as part of the work of ICCSFA.

Parental contributions have been adjusted several times in recent years. In 2004 and 2006, expected parental contributions were lowered in relation to family income and province of residence, thereby making thousands more students from middle-income families eligible to benefit from Canada Student Loans.

For applicants who dispute the assessment of their financial situation, including their expected parental contribution, an appeal process is in place to allow for a reconsideration of their assessment by provincial/territorial student aid authorities. This appeal mechanism seeks to maintain a balance between ensuring that program funds are issued on the basis of financial need and that students with demonstrated financial need are not denied access to support required to pursue PSE study.

Student Financial Assistance for Part-Time Study

While students in full-time study are the main beneficiaries of the CSLP, the Program does offer support to those whose circumstances are such that they participate in PSE on a part-time basis.

Recommendation 4 addresses the participation rate in the CSLP for students in part-time study:

Recommendation #4: There is a need to improve the understanding of the part-time loans program and possibly make changes because the coverage is quite limited (e.g. the number of participants has declined by 50% since 2000). For example, the rationale is not very clear and does not seem to respond to the current part-time student situation.

We agree with this recommendation. A number of measures were announced by the Government of Canada in Budget 2008 to enhance student financial assistance for part-time students. These measures include:

- An increase in the lifetime maximum part-time loan amount from $4,000 to $10,000;

- Elimination of the requirement to make payments on part-time loans while in school; and

- Deferral of repayment until six months following completion of studies.

These recent enhancements, implemented in 2009, significantly improve the support to part-time students. Since these changes were implemented, the number of part-time students who have benefited from the Program has increased by 94% for loans and 22% for grants. The CSLP will continue to monitor the impact of these changes. The Program will also analyze data and results of Statistics Canada's Access and Support to Education and Training Survey (ASETS) to assess the extent to which the needs of part-time students are aligned with the current support available under the part-time program.

Repayment Following Completion of PSE

The Government of Canada is committed to helping students throughout the lifecycle of their student loans. Following completion of study programs, Canada Student Loan borrowers are required to enter into consolidation agreements to repay their loans. For the majority of borrowers, this is their first experience with loan management. As such, a concerted effort is made by the Government of Canada to communicate with borrowers prior to consolidation of their loans to ensure that they are fully aware of their responsibilities as well as the repayment options that are available to them, including repayment assistance programs.

To better assist borrowers experiencing difficulty in repayment, in 2009, the Government of Canada replaced the Interest Relief and Debt Reduction in Repayment programs with the new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP). The underlying principle of the RAP is that borrowers should not be required to make a student loan payment above an affordable level and that the repayment period should not exceed fifteen years. Following the calculation of an affordable payment, which takes into account family income, family size, and the amount of loan balance, borrowers may receive support under the RAP if their monthly student loan payment exceeds an affordable payment level. For borrowers who qualify, the Government of Canada assumes portions of their interest and/or principal and they are required to make reduced or no payments on their loans during approved periods.

During the 2009-2010 loan year, more than 155,000 borrowers benefited from RAP, of which approximately 90% were not required to make any payments on their student loan. In comparison, during the 2008-09 loan year, approximately 130,000 borrowers received Interest Relief (IR) and approximately 2,500 benefited from Debt Reduction in Repayment (DRR).

In addition to RAP, the Government of Canada has also introduced the Repayment Assistance Plan for Borrowers with a Permanent Disability (RAP-PD). Like RAP, RAP-PD makes it easier for student loan borrowers to manage their debt by paying back what they can reasonably afford. Under RAP-PD, eligible borrowers make loan payments based on income and ability to pay, including consideration of disability accommodation costs.

A variety of key communication channels, including student financial assistance offices at PSE institutions, are used to disseminate information about the repayment options available to students, including support under RAP and RAP-PD. In 2008-2009, the redesign of the CanLearn.ca site provided for clear messaging about repayment options and support measures.

The evaluation draws attention, under Recommendations 2 and 3, to the awareness level of CSLP recipients upon entering into the repayment phase:

Recommendation #2: That the program improve student awareness of the support available to them at loan consolidation time.

We agree with this recommendation. Given that a student loan is often a borrower's first experience with loan management, the Government of Canada works on an ongoing basis to improve communication with borrowers at the time of consolidation.

In collaboration with student financial assistance partners, the CSLP undertakes regular outreach activities to disseminate information about repayment options and repayment support. These activities include exhibits, campaigns, online resources, toolkits, publications, as well as repayment seminars at educational institutions.

Each year, the CSLP, via the Service Provider Footnote3 , pro-actively contacts over 180,000 student borrowers who are approaching repayment to discuss repayment options and support. In addition, counselling sessions are targeted to address borrowers with a high statistical probability of encountering repayment difficulties, including those who have withdrawn early from their programs of study and have not continued their post-secondary education. The CSLP has also developed two online modules to inform borrowers about student loan repayment. These modules provide information to borrowers who are about to take their first Canada Student Loan and those who are about to begin repayment of their Canada Student Loan.

These initiatives, among others, have resulted in positive outcomes in terms of borrower awareness. According to the most recent CSLP Client Satisfaction Survey, in 2009-2010, 83% of borrowers found their repayment options to be clear.

Recommendation #3: That CSLP explore the idea of changing the name of the grace period, because the use of this term often leads to confusion for students about whether interest accrues during this six month period.

We agree that the term "grace period" may be confusing to some borrowers, and will continue to work with our provincial/territorial partners to explore a more effective way to communicate how the student loan program works. The "grace period" refers to the fact that borrowers are entitled to defer their student loan payments for six months following the completion of PSE studies, but that interest on Canada Student Loans will continue to accrue during this period. However, the confusion on the part of some borrowers may stem from the fact that some provinces do not require interest to accrue on provincial student loans during this six-month period. To mitigate any confusion, the CSLP undertakes to effectively communicate this term in all appropriate communication to borrowers, including student loan documents, on the CanLearn website, and through the Service Provider call centre.

Default Management

Given the negative consequences of loan default for both students and government, the CSLP seeks to improve repayment rates as part of a comprehensive approach to the effective management of the student loan portfolio.

CSLP's strategy with respect to default prevention includes: the provision of non-repayable grants, which reduces debt balances; effective and targeted communication with borrowers prior to their completion of PSE; repayment assistance for borrowers experiencing difficulty in repayment; and a performance-based contract with the Service Provider which provide incentives for improved student loan repayment rates.

To receive Canada Student Loans, students must be enrolled in PSE institutions which have been designated as eligible by provincial/territorial governments. Designation criteria are an important tool in pursuing objectives to reduce loan default rates and ensure that PSE investments are protected.

Recommendation 7 addresses the importance of continuing to undertake research and analysis of the student loan default rate, including the impacts of repayment support measures:

Recommendation #7: A policy research study should be conducted on the optimal default rate that takes into account the costs of repayment assistance programs. For example, the research should examine whether it is always beneficial to the government to increase assistance through repayment assistance programs in order to reduce student loan default rates. Similarly, a more pro-active pre-consolidation counselling approach could be further explored by the department to help borrowers understand debt management measures and reduce the default rate.

We agree with this recommendation and are continuing to use the latest research and analysis to build on our understanding of repayment assistance programs and their relationship to default rates.

The CSLP constantly monitors the student loan repayment portfolio to ensure that loans are being repaid, and not entering default. The vast majority of student borrowers repay their loans on-time and in full. In it most recent report (as of July 31, 2009) the Office of the Chief Actuary reported that more than 87% of loans disbursed are repaid.

The CSLP uses a 3-year cohort default rate as a main indicator of the portfolio's performance. Since the Government of Canada took over the lending of student loans in 2000, the default rate fell significantly between 2001-2002 and 2008-2009, from 38% to 14%. This decline was observed across all institution types, and was most significant for borrowers at private institutions (a decline of 28%).

The CSLP has developed a comprehensive Portfolio Management Strategy aimed at improving the management of the Canada Student Loan Portfolio as a whole. The Strategy is designed to improve repayment rates, increase the amount collected from defaulted loans, and reduce overall costs to the Program. There are initiatives in place which focus on each of the four phases of the loan life-cycle: application and disbursement, in-study account management, repayment and debt management, and collections. This includes a number of initiatives targeted at reducing risk to the Direct Loans portfolio. For example, the CSLP uses its service provider to contact borrowers who are statistically more likely to default to offer them loan counselling before their first scheduled payment.

There are additional integrity and performance improvement measures which include: oversight tools such as audits and risk assessments; fraud or abuse investigations which focus on situations that have been flagged for additional scrutiny; and a pan-Canadian designation policy framework which supports governments in working with educational institutions to improve the performance of the student loans portfolio.

Conclusion

HRSDC is committed to ensuring that the CSLP is fully responsive to the needs of Canada's post-secondary students, and will continue to explore ways to improve and enhance the design and delivery of the Program in collaboration with partners and stakeholders. The findings and recommendations of this evaluation will inform and support that work and contribute to a more effective and efficient Program for the future.

1. Introduction

This report presents a summary of the findings and conclusions of the summative evaluation of the Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP). The CSLP is intended to promote access to post-secondary education (PSE) for students with demonstrated financial need.

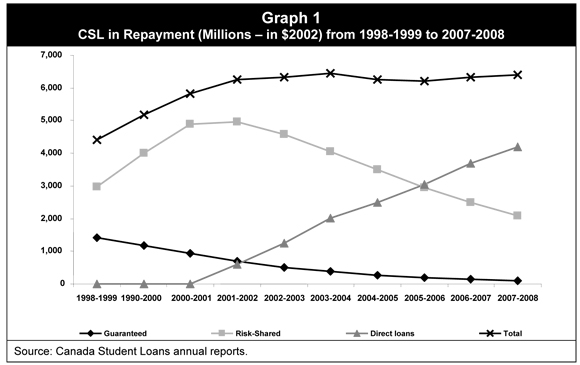

The last summative evaluation of the CSLP was completed in 1997. Since then, the CSLP has undergone significant changes such as the replacement of the risk-shared loan regime with the direct loan regime in 2000. A formative evaluation of the direct loan regime was completed in 2004. The formative evaluation was focused on examining issues of program relevance, design and delivery, but did not assess the impact of the CSLP on access to PSE.

1.1 Methodology and Limitations

Given the size and complexity of the CSLP, the evaluation framework developed for the summative evaluation proposed a series of smaller studies over a five-year period, rather than the more standard one large evaluation over the course of two years. As well, as stipulated in the evaluation framework, each year was focused on and addressed a specific theme Footnote4 . The intention was to build up a body of knowledge and encourage a year-to-year exchange with the program area. Conducting the evaluation over a five-year period also gave more flexibility to adjust the evaluation Footnote5 .

The evaluative activities were organized around a set of evaluation questions that included questions regarding program rationale, program objective and achievement, impacts and effects, cost-effectiveness, and program delivery issues and communications. The full list of evaluation questions can be found in Appendix 1 (which also indicates where each question is answered in the report and the lines of evidence used).

A total of 32 studies were conducted to address the evaluation questions. The range of methods used in addition to the literature reviews and international comparisons included:

- Surveys – a survey of 1,582 student loan decliners and an examination of existing surveys (the 2007 CSLP Client Satisfaction survey and the 2007 Omnibus survey).

- Focus Groups – a total of 16 two-hour focus groups in four cities (Halifax, Toronto, Calgary and Vancouver) with (i) borrowers in study or recent graduates; (ii) borrowers who have consolidated their loans and never used debt management measures nor defaulted; (iii) borrowers who were on or had received Interest Relief (IR); and (iv) borrowers who defaulted on their loan. The key issues addressed in the focus group sessions were whether the need assessment accurately reflects a student's financial needs, whether repayment structures and income limits for extended IR are reasonable, the extent to which students make use of other sources of funding, and the existence of program delivery and communications issues.

- Key informant interviews – a total of 45 key informant interviews with respondents from academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, student associations, provincial and territorial government employees, and federal government employees. The purpose of the interviews was to investigate the ongoing relevance of the CSLP, the perceived effectiveness of the program in meeting its objectives, the perceived short- and mid-range impacts and effects of the program, areas where the program has been successful, and areas where the program can be improved.

- Administrative data analyses and econometric analyses of a linked database consisting of CSLP administrative data and the Longitudinal Administrative Database (LAD) from Statistics Canada.

A summary of the 32 studies is provided in Appendix 3 Footnote6 . In addition, other academic studies were used to complement the work done for this evaluation.

The summative evaluation was focused on the direct loan period from 2000 to 2008 (a period containing more accurate administrative data), although references to the last years of the risk-shared regime (1998 and 1999) are included for comparison purposes. As well, the evaluation was focused on the nine provinces and one territoryand one territory that participate in the CSLP Footnote7 . Readers should also note that all amounts presented in this report are expressed in nominal terms except where otherwise indicated and that all amounts reported represent the federal portion only.

There are a few limitations with the summative evaluation:

- The evaluation focused more on the student loans aspect of the CSLP and devoted less attention to examining student grants, as loans comprise the bulk of CSLP annual expenditures. Similarly, there is more analysis of full-time PSE students than part-time PSE students.

- Findings related to the impact of loan repayment assistance measures on student loan default rates should be interpreted with caution due to a lack of multiple robust lines of evidence.

- Due to insufficient reliable evidence for some evaluation questions, 8 of the 71 questions have been left unanswered (see Appendix 1 for more detail).

1.2 Organization of Document

Section 2 of this report examines the program's rationale, objective and various activities. Section 3 examines the extent to which the program achieves its objectives of reducing financial barriers and improving PSE access. Section 4 examines program costs including cost-effectiveness. Section 5 examines the indirect impacts of the CSLP, such as its macroeconomic impacts, interactions with other programs, and repayment issues. Section 6 focuses on some program delivery issues. The last section summarizes the overall conclusions and identifies the recommendations arising from the evaluation.

2. Background

This section begins with a short history of the CSLP, and then examines the program's rationale, objectives and various activities (such as the provision of student loans and grants, and loan repayment assistance).

The history of the CSLP can be divided into three main periods:

- The guaranteed loan regime;

- The risk-shared loan regime; and

- The direct loan regime.

The initial period of the CSLP is often referred to as the guaranteed loan regime. The CSLP was created in 1964 under the Canada Student Loans Act (CSG) to promote access to PSE. Under the CSLA , the CSLP provided 100% government-guaranteed loans through banks and credit unions to students with demonstrated financial need. The participating provincial and territorial governments Footnote8 assumed the general administration of the program.

The period between 1995 and 2000 is often referred to as the risk-shared loan regime. In 1994, the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act (CSFAA) was introduced. It replaced the guaranteed loan regime with a risk-shared loan system starting in 1995/96. Under the risk-shared system, participating financial institutions were paid a risk premium for loans going into repayment each year. The CSFAA also established Canada Study Grants (CSGs), which provide non-repayable financial assistance to PSE students with particularly high levels of need and to women enrolled in doctoral programs.

The current period of the CSLP is referred to as the direct loan regime. When the majority of financial institutions opted out of participating in a proposed new agreement on the delivery of the CSLP, the Government of Canada announced on August 1, 2000 that it would assume the full responsibility for financing and administering the program. The responsibility was transferred to the Government of Canada through a corresponding amendment to the CSFAA. Since then, student loans have been provided directly by the federal government with a 60/40 federal/provincial cost-sharing arrangement with participating provinces Footnote9 . It should be noted that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) is still managing borrower files from previous regimes and will do so until 2028 Footnote10 .

2.1 Program Rationale

The mandate of the CSLP is "to promote accessibility to post-secondary education for students with demonstrated financial need. The CSLP lowers financial barriers through the provision of loans and grants which help ensure that Canadians have an opportunity to develop their knowledge and skills to participate in the economy and in society." Footnote11

The CSLP seeks to promote PSE access for students with demonstrated financial need by:

- Providing loans and grants to eligible individuals;

- Developing and implementing policies that balance requirements for accountability, integrity and responsiveness to the changing needs of students and society;

- Providing information to help students and their families make informed choices;

- Enhancing and improving the delivery of services, resulting in high client satisfaction;

- Ensuring the development and renewal of a valued, knowledgeable, motivated workforce within the CSLP; and

- Building on and improving collaborative partnerships with federal, provincial and territorial partners, stakeholders and student organizations.

The Government of Canada has also highlighted the importance of PSE. For example, the 2008 Speech from the Throne stated "Our Government will strengthen Canada's workforce for the future by continuing to support student financial assistance and taking measures to encourage skilled trades and apprenticeships. Footnote12 "

The discussion that follows looks at the rationale of the CSLP by examining:

- The need for governments to facilitate access to PSE;

- The need for a student loan program; and

- Reasons for the involvement of the federal government in student loans.

2.1.1 A Need for Government Intervention in PSE

The main arguments for government support for PSE can be described as increasing access to PSE, generating positive social benefits that go beyond the economic benefits to the individual and promoting a more equitable society. There is evidence regarding the continued value of PSE because, for example, educated individuals usually earn more as a result of their education.

The basic economic rationale for government intervention to facilitate access to PSE is that the benefits to society from having an educated population go beyond the economic benefits to the individual. For example, Riddell (2006) describes some of the potential social benefits of having an educated workforce. These benefits include an increased overall level of knowledge, improved knowledge creation (e.g. more ideas will be generated), better lifestyle choices (better health), reduced criminal activity and increased civic participation.

Government intervention to facilitate access to PSE in the case of students with demonstrated financial need can also promote a more equitable society and ensure that individuals can choose their optimal level of education. Some students are more likely than others to face financial barriers, particularly students from low-income families. Student financial assistance programs can be designed to reduce the financial burden for those with credit constraints (tuition and living expenses) and concerns about debt.

2.1.2 Why Student Loans?

The argument for providing a student loan program to facilitate access to PSE is that students are often unable to borrow from the private sector to pay for their PSE due to a lack of collateral as well as the inability of financial institutions to assess future income Footnote13 . Key informants were unanimous on the need for some form of government program. They were convinced that a significant number of students would not be able to attend PSE if the CSLP did not exist. As well, the literature review showed that all of the reviewed countries have at least some form of student loan or grant regime. This indicates a general consensus that the credit constraints are sufficient to warrant government action.

The literature review suggests there is also a consensus that multiple forms of student assistance increase PSE enrolment levels. For example, Singell (2001) found that needs-based grants, subsidized loans, and work study programs encouraged enrolment in a large public university. Nevertheless, there is less evidence that loans have a positive impact on overall PSE enrolment (perhaps with the exception of the Dynarski (2003) study). For example, the review suggested that if an existing student aid program switches from providing primarily loans to providing primarily grants or a combination of loans and grants, then there appears to be no statistically significant enrolment response except for low-income students.

It should also be noted that studies have found both positive and no enrolment effects associated with federal grant programs in the U.S. (Section 3.4.3 provides a further discussion of efforts to measure the impact of student loans and grants on access to PSE).

2.1.3 Involvement of the Federal Government

In most provinces and territories, the student loan regime is a shared responsibility of the federal and provincial governments. In the case of a non-participating province or territory, the federal government transfers funds so that the non-participating jurisdiction can operate its own program Footnote14 . The main arguments for the involvement of the federal government in student loans to facilitate PSE are equality of access across the country and historical precedent, as discussed below.

Key informants unanimously agreed that there was a need for a federal program designed to help key targetdifferent groups access PSE. In general, there was a strong consensus that the federal government should play some role in student loans, although there were differences of opinion on what the optimal split of responsibility should be. Some key informants suggested that the current 60/40 federal/provincial cost-sharing arrangement with participating provinces could be adjusted depending on the needs of each jurisdiction. However, student groups and institutions had no problem with the current split.

From a historical perspective, the literature review described how the federal government has played a role in providing student loans since the late 1930s, when student loans were seen as a way to help students deal with the economic hardships of the Depression. The literature review noted that all of the provinces had joined the Dominion-Provincial Student Aid Program by 1944 which, along with the Veterans Rehabilitation Act (1945), were the precursors to the CSLP (established in 1964).

International comparisons showed that there are several other countries where loans are issued by the central government, such as the Federal Stafford Loans in the United States and Germany's student loan program.

2.2 Description of the Program

Since 1964, the activities of the CSLP have evolved considerably. For instance, the government announced many changes to the CSLP under the 1998 Canadian Opportunities Strategy, which included the creation of new grants (CSGs) for full-time students with dependants, the creation of the Debt Reduction in Repayment (DRR) provision, as well as enhancements to the Interest Relief (IR) provision.

Since the shift to the direct loan regime (in 2000), more changes have been incorporated into the CSLP such as a new CSG for high-needs students with permanent disabilities (2002), changes to in-study exemptions (2003), and new amendments to the IR and DRR provisions (2003).

Some additional changes were announced in the 2004 Budget (which came into effect on August 1, 2005). These changes included increasing the loan limits and the allowances for computer-related costs, reducing expected parental contributions, increasing the income threshold for IR eligibility, increasing the amount of DRR, and implementing new grants (Canada Access Grants).

In the 2005 Budget, it was announced that eligibility for loan forgiveness for direct loans would be extended in the event of death or permanent disability. The 2006 Budget announced that parental contributions would be further reduced starting on August 1, 2007. Further changes were announced in the 2008 Budget, but those changes are beyond the scope of this evaluation.

The current evaluation is focused on examining CSLP activities under the following structure:

- Canada Student Loans (CSLs);

- Canada Study Grants (CSGs) and Canada Access Grants (CAGs); and

- Loan repayment assistance.

2.2.1 Canada Student Loans (CSL)

Under the current legislation, the CSLP provides financial assistance in the form of direct loans to students with demonstrated financial need Footnote15 . These loans are available to students enrolled in full-time or part-time studies at a designated PSE institution Footnote16 .

In order to receive financial assistance in the form of a CSL, students must satisfy initial eligibility criteria Footnote17 . Upon establishing eligibility, a needs assessment is conducted to determine the amount of each student's financial need. The needs assessment process is designed to take into account provincial differences and the additional needs of certain groups (e.g. students with dependents, students living away from home, students who relocated to pursue PSE).

Provincial and territorial government partners determine both eligibility and level of need using federal criteria. From 1995 to 2004, the maximum weekly federal loan limit that could be received by a student was $165. The federal loan limit was increased to $210 per week at the start of the 2005-2006 loan year.

While a student borrower is pursuing full-time studies, the federal government (through the CSLP) the federal government (through the CSLP) subsidizes the interest that would otherwise accumulate on the loan principal. The borrower is required to begin repayment of the loan within six months after ceasing full-time studies. However, the interest subsidy does not apply to the six month post-study period. This six-month period is called the "grace period". Students studying part-time might be eligible for the part-time student loans program. The conditions for these loans differ from the full-time student loans program.

2.2.2 Canada Study Grants (CSGs) and Canada Access Grants (CAGs)

Up until 2008, the CSLP provided non-repayable financial assistance in the form of CSGs and CAGs to PSE students with particularly high levels of need who qualified for loans (these two grant programs were discontinued and replaced by the Canada Student Grants Program in 2009).

- CSGs assisted students with permanent disabilities, high-need students with permanent disabilities, high-need part-time students, students with dependants, students from low-income families and female students in doctoral programs in which women are traditionally under-represented.

- CAGs assisted first-year students from low-income families and students with permanent disabilities.

Eligibility for the grants was determined by provincial and territorial partners using federal criteria.

Key informants generally agreed that most of the targeted groups should receive grants because the need of these groups was high (due to a variety of circumstances). However, some argued that it was difficult to find an explicit rationale for the grant for female students in doctoral programs in non-traditional fields. Key informants felt that since females now make up a greater percentage of university students than males, it is likely that any disparity in the numbers of doctoral students will resolve itself. Their views are supported by available data which show that the 17-to-29 year-old full-time participation rate was 15.3% for females compared to 11.4% for males in 2005-2006 Footnote18 . As well, a Canadian Education Statistics Council study showed that the doctorate graduate rate for males was 1.1% in 1994 and in 2005, while the doctorate graduate rate for females increased from 0.5% to 0.9% during the same period Footnote19 . Additional information from the Statistics Canada Survey of Earned Doctorates indicates that the proportion of women graduating from Canadian doctoral programs was just over 50% in 2004-2005. In addition, given that many Canadian universities now offer guaranteed funding to doctoral students, it seems unlikely that this group is facing particularly high financial needs.

2.2.3 Loan Repayment Assistance

In addition to providing assistance for access to PSE in the form of loans and grants, the CSLP provides a variety of assistance to student loan borrowers who are having difficulties meeting their repayment obligations. Although IR and loan forgiveness existed prior to 1998, some loan repayment assistance measures were introduced in the 1998 Budget, and most were extended in the 2003 and 2004 Budgets (the Repayment Assistance Plan introduced in 2009 replaced the existing loan repayment assistance provisions).

- Borrowers experiencing financial hardship in repaying their loans could bewere eligible for up to 30 months of IR during the lifetime of their loans. Under IR, the government paidys the interest on the loan and the borrower wasis not required to make any payments on the principal or interest.

- Following 30 months of IR and during the first five years after leaving school, borrowers continuing to experience financial hardship could an apply for an additional 24 months of Extended Interest Relief (EIR). This would bring the total to 54 months during which no payment of interest or principal wasis required.

- Borrowers experiencing financial hardship in repaying their loans couldan ask for a revision of the terms of repayment.

- Borrowers still experiencing financial difficulties after five years of leaving full-time or part-time study, and who hadve exhausted IR and EIR, could apply to have their loan principal reduced through DRR. Currently, an individual couldan receive up to three reductions on their loan principal during their lifetime, for a total of up to $26,000 (depending on their financial circumstances).

- A borrower with a permanent disability couldmay request that their loans be forgiven should were they be unable to repay the loan without exceptional hardship due to their disability. Loan forgiveness couldmay also occur in the case of death.

Key informants had a positive view towards debt management measures such as IR and DRR. They believed that these measures reduced the likelihood of complete default by the borrower. Key informants also believed that borrowers present a high short-term risk while they are looking for employment after PSE, but present a much lower long-run risk. Therefore, measures that help the borrower get over this initial hurdle will ultimately lead to higher loan repayment overall. Indeed, most studies confirmed that default occurred within three years after loan consolidation.

3. Achievement of Program Objectives

As noted in Section 2.1, the objective of the CSLP is to "promote accessibility to post-secondary education for students with demonstrated financial need. The CSLP lowers financial barriers through the provision of loans and grants which help ensure that Canadians have an opportunity to develop their knowledge and skills to participate in the economy and in society."

An estimate of the potential PSE population for the 2005-2006 academic year (based on the October 2005 Labour Force Survey) indicates that there were about 2,229,600 potential university, community college, CEGEP Footnote20 and other PSE students in Canada, or approximately 7% of Canada's population (this includes Quebec). However, the CSLP program does not target every potential PSE student (i.e. is not a universal program), but focuses on students with demonstrated financial needs. As well, full-time PSE students and part-time PSE students face different CSLP rules (as noted in Section 2.2.1). Therefore, to assess whether the CSLP achieved its objective, this section examines:

- The coverage of the program and the characteristics of program participants in the case of full-time PSE enrolment and part-time PSE enrolment; Footnote21

- The needs assessment approach used by the CLSP; and

- Access to PSE under the CSLP.

3.1 Full-Time PSE Enrolment

The actuarial reports of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions provide an estimate of the full-time PSE enrolment population each year, which is also used in the CSLP annual reports. These reports indicated that the full-time PSE enrolment population was about one million students in 2007-2008, an increase of 243.6% since 2000-2001 Footnote22 .

Table 1 shows the number of PSE students enrolled full-time (using both actuarial reports from the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Labour Force Survey) and the number of full-time student borrowers to whom loans were disbursed by the CSLP since the 2000-2001 loan year. This information shows that the number of borrowers was relatively stable over the period (with an overall increase of 2.7% between 2000-2001 and 2007-2008), while the CSLP coverage of full-time PSE students declined between 2000-2001 and 2007-2008 (from 41.82.4% to 34.4%5.2%). This reduction in coverage may be partially explained by a change in the socio-economic status of PSE students. The Canadian Education Statistics Council study showed that 50% of university graduates (40% of public college graduates) borrowed from a government student loan program in 2005, a proportion that has been fairly stable since 2000 Footnote23 .

Table 1 also shows the average loan size since the 2000-2001 loan year. It is worth noting that the average loan size increased by about $800 in 2005-2006, as a result of an increase in the loan limit (as mentioned in Section 2.2.1). Nevertheless, a study done by The Brondesbury Group indicated that the amount of federal disbursement has declined in constant (i.e. inflation-adjusted) dollar terms over the period.

| Loan Year | Number of PSE Students Enrolled Full-Time (OSFI) | Number of PSE Students Enrolled Full-Time (LFS) Reference ** is located after the table | Number of CSLP Borrowers | % of CSLP Participants (% of OFSI) | Average Loan Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-2001 | 822,040 | 914,068 | 343,588 | 41.80% | $4,554 |

| 2001-2002 | 865,452 | 945,137 | 328,674 | 37.98% | $4,586 |

| 2002-2003 | 904,763 | 996,768 | 328,991 | 36.36% | $4,695 |

| 2003-2004 | 981,425 | 1,053,795 | 340,203 | 34.66% | $4,830 |

| 2004-2005 | 998,61 | 1,087,688 | 337,256 | 33.77% | $4,829 |

| 2005-2006 | 1,003,841 | 1,103,925 | 343,638 | 34.23% | $5,631 |

| 2006-2007 | 1,001,676 | 1,112,731 | 343,261 | 33.93% | $5,614 |

| 2007-2008 | 1,024,182 | 1,108,300 | 352,708 | 34.44% | $5,706 |

-

Source from the above table Source: OSFI Actuarial Reports, CSLP Annual Reports, Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey.

Note: Reference ** from the above table LFS figures for 2000/01 loan year reflect the average of 2001 in-school months (January to April and September to December), figures for 2001-2002 loan year reflect the average of 2002 in-school months, etc.

3.1.1 Gender

A trend analysis study conducted for this summative evaluation showed that PSE enrolment has increased slightly for both genders, although the increase in the enrolment rate for females was greater Footnote24 . Another study showed that, compared to males, young females had a higher full-time PSE participation rate (by 8 percentage points) and a higher CSLP take-up rate (by 5 percentage points) in 2000 Footnote25 . This situation continued in 2007-2008, with females comprising 54.6% of all PSE students and close to 60% of all CSLP recipients.

The CSLP annual data showed that the increase in the number of CSLP participants from 1998-1999 to 2007-2008 has been entirely due to an increase in female participants (which increased by 12%), while the number of male participants decreased by 5.3%. The study done by The Brondesbury Group corroborated this finding, showing that there have been slightly more female CSLP participants than male participants since 1993.

3.1.2 Provinces

Kapsalis (2006) reported that, in 2000, the average PSE enrolment rate (approximately 30%) was similar in most Canadian regions. The exception was Ontario (36%). The study indicated that the Atlantic region had the highest CSLP take-up rate (45%) compared to the other regions (between 28% and 31%). Since 1998-1999, most of the provinces show minor changes in the number of CSLP participants, with the exception of a major decline (-51%) in Newfoundland, as well as declines in Saskatchewan (-20.7%) and Manitoba (-17.5%) Footnote26 . The number of Ontario CSLP participants has increased by more than 60,000 since 2001-2002.

The trend analysis study provides a partial explanation for these provincial changes in CSLP take-up rates, especially in Newfoundland and Ontario. It showed that the number of full-time PSE students decreased by 18% between 1998 and 2006 in Newfoundland (according to the Labour Force Survey), while the number of PSE students in Ontario increased by 17% over the same period. Other factors that may help to explain the large decline in the number of CSLP participants in Newfoundland is a drop in tuition fees of $1,174 over the 1998-1999 to 2006-2007 period and a 30% increase in the median income (12 percentage points higher than all of Canada). This issue is examined further in Section 3.3.2.

3.1.3 Age and Marital Status

Data from the 2005 Labour Force Survey indicated that the majority (86.0%) of the full-time PSE population in Canada is less than 30 years old. A review of the annual CSLP reports showed that most participants (about 80%) are below the age of 25. As well, the proportion of participants 30 years of age and older declined significantly (from 15% to 10%) from 1998-1999 to 2007-2008. The trend analysis study conducted for this evaluation corroborated this finding and indicated that "the age of borrowers seems to have slightly decreased between 1998 and 2005."

The Brondesbury Group study reported that the younger age group (18 to 22 year olds) was less likely to take student loans than the older group (23 to 26 year olds). It is possible that the younger age group is more likely to rely on their family as a source of financing, while the older group has workforce experience and is more likely to be making independent financing decisions. Evidence in the study indicated that those who collected Employment Insurance benefits during the preceding year were more likely to apply for student loans. Since Employment Insurance is only available to those with workforce experience, it may support the explanation above.

In 2005, the proportion of single PSE students was 71%, married or common law couples 26%, and all others 3% (based on the Labour Force Survey). The review of CSLP annual reports shows that since 2002-2003, the number of single participants has increased by 13.3%, while married or other types of students have both decreased by more than 20%.

As well, the non-singles groups accounted for a declining proportion of all CSLP participants. Between 2002-2003 and 2007-2008, their shares of CSLP participants dropped from 10% to 7.3% and from 6.7% to 4.7% respectively, while the single student proportion rose from 83.3% to 87.9%. The assessment of the needs for couples (married or in a common law relationship) might explain the difference between their proportion of the PSE population and their proportion of all CSLP participants.

3.1.4 Type of Institution

The trend analysis study showed that college enrolment between 1998 and 2006 declined slightly, while the full-time enrolment rate in university increased over this period Footnote27 . The population of CSLP participants also changed in terms of the type of institution. Over the decade, participants studying in university increased by 18.2% (the share of CSLP participants studying in university increased by 6.7 percentage points), while the proportion of participants studying in college remained constant. Those studying in private institutions fell by 27.6%. In 2007-2008, 59.3% of all university students were CSLP recipients, compared to 53% of all PSE students.

A possible explanation for the increased enrolment in university compared to college might be related to expected earnings. For example, in Drewes (2006) it was noted that "Past studies...have found real earnings of college graduates... from the 1985 cohort through to the 1995 cohort...to be in the order of 78% to 82% of university graduates". Similar results were found in the trend analysis study, which showed that the earning premium for university graduates over college graduates increased from 19% to 26% for males and from 27.6% to 34.9% for females between 1992 and 2002. As the earnings difference increased during the period, it is possible that students made an adjustment in favour of universities.

There were also changes in the proportion of CSLP recipients by study level. For instance, those studying at the undergraduate level and at the Masters level increased by 21.4% and 19.9% respectively over the 2000-2001 to 2007-2008 period, while those studying at the non-degree level (i.e. completing degree level courses for professional or personal interest) decreased by 18%. Those studying at the Doctorate level declined slightly over the period.

3.1.5 Those in Financial Need

The first objective of the CSLP is to lower the financial barriers to PSE for students with demonstrated financial need. Evidence from the trend analysis study, other studies and key informants confirmed that the CSLP appears to be is properly targeted towardslowering financial barriers for students from low-income families.

Some previous studies have indicated that full-time PSE enrolments are sensitive to parental income and parental education (Drolet 2005; Lambert et al. 2004). Similarly, the Labour Force Survey shows that, in general, PSE enrolment rates increase with the income level of the parents, especially in the case of university enrolment.

As expected, there is a negative relationship between parental income and CSLP take-up and the average loan received. For instance, 60% of students with parental income of less than $40,000 were CSLP recipients in 2000. The percentages decline significantly as parental income increases, rising from 51% for students from families with parental income between $40,000 and $60,000, to 5.5% for students with parental income of more than $100,000. The average loan for CSLP participants with parental income under $60,000 was fairly constant at around $4,000 per year. Overall, the trend analysis study concluded: "While participation in post-secondary education was found to increase with parental income, CSL eligibility was found to decrease with parental income. The CSLP seems, therefore, consistent with its goal of improving equity in post-secondary access."

In the case of independent students Footnote28 , student loans are not conditional on the income of parents. Therefore, the average loan received by independent students was constant across all parental income groups Footnote29 . As well, among independent students, the incidence of receiving loans was constant for low- and middle-income students (close to 40% for those with parental income under $60,000). At the $60,000 parental income threshold, however, the use of the CSLP among independent students started to decline, perhaps reflecting a correlation between student and parent resources.

Kapsalis (2006) provided corroborating evidence that the CSLP is well-targeted towardssucceeds in lowering financial barriers for students from lower-income families, especially in the case of dependent students. Participation in the program falls off dramatically as family income rises. Many key informants also corroborated this finding, indicating that the program is effective for low-income students. Nevertheless, some key informants felt that dependent students from middle-income families were underserved by the program. In particular, these key informants felt that the expected parental contributions from middle-income parents are too high, implying that some students from middle-income families whose parents don't contribute are denied the required student loan funding (the issues of parental contributions is discussed further in Section 3.3.3).

3.2 Part-Time PSE Enrolment and Part-Time Programs

Although there is no reference to an estimate of the part-time PSE population in the actuarial reports, a report developed for this evaluation using the Labour Force Survey estimated that the part-time PSE population was 460,000 in 2005 Footnote30 . As well, the estimated part-time PSE population has been fairly constant since 2000. Similarly, the fourth edition of the Price of Knowledge estimated part-time PSE enrolment to be 410,000 in 2005, excluding students enrolled in private career colleges Footnote31 .

Part-time CSLP loan recipients are a small percentage of the estimated total part-time PSE population (less than 0.5%), as shown in Table 2. This means that the part-time group also accounts for a small percentage of all CSLP loan recipients, as well as a small proportion of total program disbursements. Looking at the part-time group over time indicates that the number of part-time CSLP recipients decreased by more than 50% (from 2,980 to 1,436) between 2000-2001 and 2007-2008, while the average loan size remained fairly stable, even though loan limits increased in 2005-2006.

| Loan Year | Number of Borrowers | Average Loan Size |

|---|---|---|

| 2000-2001 | 2,980 | $1,812 |

| 2001-2002 | 2,867 | $1,717 |

| 2002-2003 | 2,772 | $1,649 |

| 2003-2004 | 2,779 | $1,680 |

| 2004-2005 | 2,572 | $1,798 |

| 2005-2006 | 2,127 | $1,795 |

| 2006-2007 | 1,863 | $1,880 |

| 2007-2008 | 1,436 | $1,948 |

- Source from the above table Source: CSLP Annual Reports.

The low level of CSLP participation among part-time PSE students may raise some uncertainty about the rationale and the achievement of CSLP objectives for part-time PSE students. Some could argue that the rationale for providing loans and grants for part-time students is weaker than for full-time students because part-time students might have more resources. However, it is possible that some of these students may not have enough collateral to get a private loan for studying.

Many key informants questioned the rationale behind having separate policy approaches for part-time and full-time students. They pointed out that part-time students were not as well served as full-time students by the part-time program and that the program is not meeting the objective of promoting "accessibility to post-secondary education for students with demonstrated financial need". As well, many key informants suggested that the part-time program should be thoroughly evaluated because the profile of part-time students has changed significantly since the inception of the program. They said that in today's environment, many students are often studying part-time because of other obligations such as family and work. They also said that these students should be encouraged to attend PSE, for the benefit of the students and for the benefit of society, and that any policy approach fostering part-time enrolment in PSE should be explored.

Key informants also felt that part-time students should not be charged interest during their studies. They were also generally opposed to the idea of changing the program so that it would reward students with a higher academic standing. They felt that there were already enough incentives in the system to encourage students to have high marks, and that the CSLP was not an appropriate vehicle to do this. However, a vast majority of key informants did support the idea of financial incentives for students to complete their studies.

It should be noted that the 2008 Budget implemented some changes in order to make loans more attractive to part-time students, but these changes are beyond the scope of this evaluation. Overall, the evidence presented above suggests that further work is needed to assess the rationale and effectiveness of the part-time program in greater detail.

3.3 Needs Assessment Approach Used by the CSLP

The CSLP operates on the basic principle that the cost of PSE is a shared responsibility between students, parents or spouses, and the government. Students and their families are expected to contribute based on their ability to pay, while government assistance is supplemental and based on the student's needs. Full-time loans are therefore provided on a needs-tested basis that takes into account both the student's available resources and the costs of PSE attendance. This needs assessment process is performed by provincial and territorial levels of government who apply the CSLP criteria with some variations. Many countries providing non-universal loans are using a similar system of needs-based assessments.

Needs assessments are highly individualized, because a large number of factors are involved in the determination of needs (e.g. the level of tuition fees, cost of living, marital status, living arrangements, student income, parental and spousal resources and family size). While this complexity has the advantage of providing more fairness in the determination of needs, some provincial officials interviewed during the 2004 formative evaluation found the needs assessment process to be complicated, especially from the students' perspective.

A needs assessment is performed for every eligible full-time PSE student who applies for the CSLP in any participating jurisdiction. The needs assessment process consists of four main steps:

- Identifying the student's category: single dependent, single independent, married or common-law, and single parent, and permanently disabled;

- Assessing the student's costs of PSE;

- Determining the resources available to the student; and

- Calculating the student's needs.

The focus group analysis indicated that, overall, the needs assessment process for loans was reasonably clear to the focus group participants. For example, there was recognition that financial need drives program eligibility and that the program uses multiple criteria to determine the amount of the student loan. Focus group participants had mixed views on the fairness of the needs assessment process, however. They felt that the overall categories of expenses and resources that are taken into consideration in the needs assessment process were generally acceptable, but they were less willing to accept the assumption of parental contributions.

Key informants generally held the view that, because the program is needs-tested, most of those who need a loan get a loan. They added that there will always be some gap between intended and actual beneficiaries and that the system can never be perfect. They indicated that the program generally does a good job and that overall the funding is well targeted.

The maximum loan limit was identified as an issue by some key informants and focus groups. Some of the key informants said that many student needs were unmet because many loans were capped at a certain amount. Given the capping of loans, even though students were assessed as needing more aid, they did not get it because of loan limits. Similarly, some in the focus groups felt that the borrowing limit could be increased to enable students to achieve a better balance between their work and school commitments. However, many of these focus group participants were uncertain whether they would have borrowed more even if the opportunity had been available to them, given their experience with repayment responsibilities and the costs of borrowing.

As mentioned earlier (in Section 2.2.1), the maximum loan limit was increased from $165 per week to $210 per week at the start of the 2005-2006 loan year. The actuarial reports showed that the percentage of students receiving the maximum loan was 42.6% in 2000-2001, increased to 52.9% in 2004-2005, and then fell to around 35% after the maximum limits were increased. These results suggest that the maximum limit was revised on time and probably addressed the issue raised by key informants and focus group participants. As evidence, a report completed for this evaluation showed that the percentage of borrowers with unmet needs declined after the increase in the loan limit. The loan limit might also partially explain the stable average loan amount for dependent students with parental income under $60,000 (as reported in Section 3.1.5). If so, then that situation could also have changed following the revision of the maximum loan limit Footnote32 .

3.3.1 Assessing the Cost of PSE

Student costs are assessed for the entire academic year in which the student is enrolled (number of assessed weeks) and include tuition and fees, books and supplies, living allowances (accommodation, food, transportation, and miscellaneous expenses), return transportation, and child care costs. As well, discretionary allowances can apply to any student who faces special circumstances.

The student expenses study conducted for this evaluation compared the student allowances with the associated student expenses in order to measure their adequacy. Overall, the study indicated that student allowances were roughly in-line with student expenses. Looking at different expenses, the report provided the following findings.

- Accommodation: The allowances seem to suit the needs of most students. However, single students in Alberta spent more than the allowable limit by about $61 each month – only students in Nova Scotia also spent more than the monthly allowance (by less than $5). In addition, some students pay rent to their parents, although it is not included in the loan calculation.

- Food: On average, each type of student in every province spent less than the allowance.

- Transportation: Given that the allowance is meant to cover only the costs of public transportation and that 36% of students (up to 50% in Alberta and Saskatchewan) own or lease a car, many students spent much more on transportation than the allowance. It should be noted, however, that students without a car spent less than the allowance. Public transportation might not be an option for students who attend school in more rural communities. However, car expenses may be included in the calculation of other allowances in the cases of students living at home who do not have access to public transportation and must drive a car to school (CSLP policy procedure).

- Miscellaneous expenses: Footnote33 When compared with the CSLP allowance, on average, loan recipients and all students spent below their allowance by an average of $15 and $33, respectively, without any major difference by province or type of student.

- Childcare: There was no significant difference between the allowance and the average spending on childcare.

- Books and supplies: Most students spent within the maximum allowance. In fact, only 6.7% of all students reported expenses that exceeded the maximum allowance.

The student expenses study also examined expenses that are not recognized by the CSLP but that could be seen as being a current expense for students. Examples of these types of expenses include meals in restaurants, entertainment expenses and other living expenses that are not captured in any other category. The "unrecognized" expenses category is relatively consistent across provinces and student types, amounting to approximately $170 per month. Many key informants and focus group participants felt that some student expenses were not properly covered, such as computers, internet access, books and other supplies (which are often more expensive than originally estimated).

Although student focus group participants generally did not feel that student loans are sufficient in light of the real costs associated with PSE, the student expenses study indicated that the current allowances are adequate in terms of meeting average monthly total student expenditures for the majority of students (66%). The allowances were, on average, approximately $85 per month higher than the average total expenditures.

The analysis by category of students revealed that the allowances for single students were slightly lower than their monthly expenditures by a range of $13 to $40 per month. Married students (with and without children) and single parents had a significantly lower level of expenditures than their living allowances.

3.3.2 Provincial Differences

Among Provinces

The living allowance provided through the CSLP is adjusted based on a provincial/territorial average cost associated with shelter, local transportation, food and miscellaneous personal expenses. Consequently, there are wide variations in the cost of living and the corresponding allowances among the provinces.