Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic

From: Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers responsible for Seniors Forum

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Participating governments

- Acknowledgments

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Literature review

- 3. What was learned from this review

- 4. Conclusion

- Annexes

- References

Alternate formats

Social Isolation among Older Adults during the Pandemic[PDF - 2.6 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- AFC

- Age-Friendly Cities

- AWIC

- Aging Well in Communities

- BC

- British Columbia

- BH

- Better at Home

- CAA

- Canadian Automobile Association

- CBSS

- Community-based seniors sector

- CFHI

- Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement

- CIHI

- Canadian Institute for Health Information

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CIP

- Community Initiatives Program

- CLSA

- Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

- COVID-19

- Coronavirus

- CTM

- Choose to Move

- DIA

- Dialogues in Action

- ESCC

- Edmonton Seniors Coordinating Council

- ECSF

- Emergency Community Support Fund

- EPIC

- Eldercare Project in Cowichan

- FAF

- Fresh Air Fun

- FPT

- Federal, Provincial and Territorial

- H2O

- Hand over Hand Network

- HIGI

- H2O Intergenerational Group Interactions

- HIMI

- H2O Intergenerational Mentorship Interactions

- HIPI

- H2O Intergenerational Paired Interactions

- INESSS

- Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux

- INSPQ

- Institut National de santé publique du Québec

- LGBTQ2

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit

- LTC

- Long-term care

- MASC

- Manitoba Association of Senior Centres

- NCCIH

- National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health

- NCCMT

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools

- NHSP

- New Horizons for Seniors Program

- NS

- Nova Scotia

- OACAO

- Older Adults’ Centres Association of Ontario

- OCSA

- Ontario Community Support Association

- OWSEP

- Older Winnipeggers Social Engagement Project

- PEGASIS

- Pan Edmonton Group Addressing Social Isolation in Seniors

- PEI

- Prince Edward Island

- PEIANC

- PEI Association for Newcomers to Canada

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PPE

- Personal Protective Equipment

- SAGE

- Student Association for Geriatric Empowerment

- SAIL

- Seniors Abuse and Information Line

- SALC

- Seniors Active Living Centre

- SCWW

- Senior Centre Without Walls

- SSIPP

- Student-Senior Isolation Prevention Partnership

- SSSC

- Safe Seniors, Strong Communities

- TAPS

- Therapeutic Activation Program for Seniors

- TIP-OA

- Telehealth Intervention Program for Older Adults

- UK

- United Kingdom

- US

- United States of America

- UWLM

- United Way of the Lower Mainland

- WHO

- World Health Organization

List of tables

- Table 1: COVID-19 cases and deaths by age group

- Table 2: Loneliness patterns by age and sex, baseline (2011 to 2015), follow-up one (2015 to 2018), and during pandemic (2020), CLSA

- Table 3: Depression patterns by age and sex, baseline (2011 to 2015), follow-up one (2015 to 2018), and during pandemic (2020), CLSA

- Table 4: Befriending programs

- Table 5: Telephone outreach and help or information lines

- Table 6: Health promotion and wellness programs

- Table 7: Practical assistance programs

- Table 8: Technology training and donation programs

- Table 9: Senior Centre Without Walls programs

- Table 10: Other remote programs

- Table 11: Mechanisms to support learning and collaboration

- Table 12: Interventions to address social isolation in long-term care

- Table 13: Governmental grant programs and funding

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Québec*

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

*Québec contributes to the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Québec.

The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

Acknowledgments

Prepared by Andrew V. Wister and Laura Kadowaki, Gerontology Research Centre, Simon Fraser University for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors.

The authors wish to acknowledge that the tabular data in this report were based on the data and biospecimens collected by the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Funding for the CLSA is provided by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant reference: LSA 94473 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. The CLSA data were drawn from prior analyses by the lead author that were part of approved CLSA projects, as well as data drawn from the CLSA COVID-19 Survey Dashboard available on the CLSA web site. The CLSA is led by Drs. Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson and Susan Kirkland.

Executive summary

In this section

Introduction

The new Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease that was discovered near the end of 2019. COVID-19 has been conceptualized as a “gero-pandemic,” defined as a disease that has spread globally with heightened significance and negative consequences for older populations (Wister & Speechley, 2020). Older people are particularly vulnerable to the harmful health impacts of COVID-19, as well as social isolation and loneliness as a result of public health measures to reduce transmission of the disease (for example, physical and social distancing measures, closure of community spaces).

This report investigates how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected older Canadians, focusing on social isolation and loneliness. Social Isolation is defined as “a lack in quantity and quality of social contacts” and “involves few social contacts and few social roles, as well as the absence of mutually rewarding relationships” (Keefe et al., 2006, p.1). Loneliness is “defined as a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010, p.1). While social isolation and loneliness can have both common and unique features, we use the term social isolation in this report to designate both terms except where distinct patterns require attention. To inform the report, a comprehensive search of academic and grey literature was conducted, including promising practices aimed at reducing social isolation. This was supplemented with new data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). The World Health Organization’s Age-Friendly Cities Framework was used as a guiding model for the review.

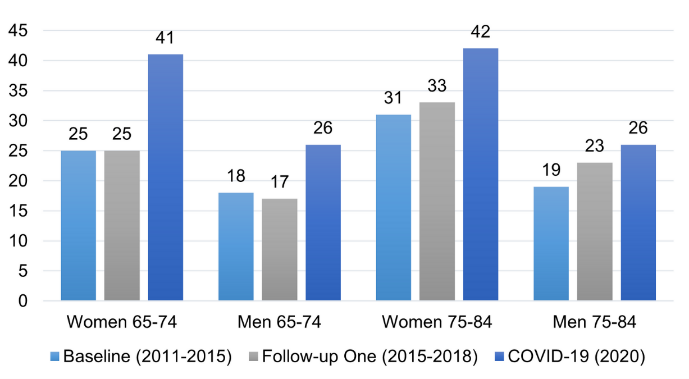

In Canada, data from the CLSA reveals striking increases in feelings of loneliness from the first results of the study (2011 to 2015) to COVID-19 (April to December 2020). It is estimated that there is a 67% increase in loneliness for women aged 65 to 74, and 37% for those aged 75 to 84. Smaller increases are observed for men, where there is a 45% relative rise for men aged 65 to 74 and 33% for the oldest group.

Literature review: challenges faced by older adults during the pandemic related to social isolation

Social isolation and vulnerable sub-populations of older adults

The literature identifies sub-populations of older adults who may be particularly vulnerable to social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, including: rural, remote, and Northern communities; LGBTQ2 older adults; ethnic minority and immigrant older adults; Indigenous peoples; people living with dementia; caregivers; and low-income older adults. The pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing inequities in health, access to health care, employment, and other areas for older Canadians. However, sources of resilience were also identified; for example, some First Nations communities have drawn upon traditional practices and culture to protect their elders (that is encouraging return to the land, governance of community entry).

Social isolation and community-dwelling older adults

Findings on the challenges faced by community-dwelling older adults as well as examples of interventions to address social isolation are organized in the report according to the 8 domains of the Age-Friendly Cities Framework.

- Respect and social inclusion: experts have expressed concerns about the intensifying of ageist views, intergenerational tensions, and aging-related social problems (such as elder abuse) during the pandemic (Ayalon, 2020; Makaroun et al., 2021). Befriending and other intergenerational programs have sought to create connections between older and younger generations

- Housing: older adults living alone and in social housing have been identified as at-risk groups during the pandemic (Emerson, 2020; Pirrie & Agarwal, 2021). Older adults living in non-institutional congregate living settings (such as assisted living, retirement communities) share similar vulnerabilities to long-term care (LTC) residents, but live in a setting guided by social models of care and with higher levels of autonomy (Zimmerman et al., 2020)

- Community support and health services: significant disruptions have occurred to community support and health services. While remote delivery was already being used for some services prior to the pandemic (for example, caregiver support programs), others have transitioned to new models of delivery. With support from government funding, practical assistance programs have been initiated or significantly scaled up in response to high levels of demand. In some jurisdictions, governments have taken a role in coordinating large-scale responses to the pandemic and supporting community agencies

- Transportation: data suggests transit use by older adults has declined during the pandemic (Palm et al., 2020a; 2020b). On the other hand, there has been a scaling up of volunteer driver services and delivery programs in many communities to support isolated older adults. However, some communities have reported shortages of volunteer drivers resulting in gaps in service (such as CBC News, 2021; Weldon, 2020)

- Communication and information: while data suggests over two-thirds of older Canadians use the internet (Davidson & Schimmele, 2019), certain segments of the population (such as low-income older adults; people living in rural, northern, and Indigenous communities; the very old; and older adults with physical disabilities or cognitive impairments) may encounter challenges in access and use. To overcome this “digital divide,” programs that provide training and access to digital technologies are being implemented or expanded across Canada. Telephone help and information lines and telephone outreach programs have also been initiated or enhanced for older adults who prefer low-tech interventions

- Social participation: the pandemic has disrupted the operations of community and recreation organizations, and many have switched to remote delivery of programs. The Senior Centre Without Walls model that offers telephone or virtual programs has been adopted by organizations in many jurisdictions. However, securing adequate funding to support their operations has been a challenge for some non-profit and community organizations (for example, Coordinated Pandemic Response Steering Committee, 2020)

- Civic participation and employment: for some older adults, work and volunteering are important sources of social connection. Older workers in Canada have been negatively impacted by workplace closures and growing unemployment rates during the pandemic (CLSA, 2021; Statistics Canada, 2021). Declining participation of older volunteers has also been observed, with COVID-related health concerns a contributing factor (Volunteer Canada, 2020; CLSA, 2021)

- Outdoor spaces and buildings: outdoor spaces can provide lower-risk locations to safely socialize and engage in physical activities. Strategies are needed to maximize the availability of outdoor community spaces and ensure that they are “COVID-19” age-friendly in design (INSPQ, 2020). Strategies are also needed so older adults can safely return to indoor spaces (such as providing hand sanitizer, smaller groups) (OACAO, 2020)

Social isolation among older adults residing in long-term care facilities

In LTC settings, concerns about social isolation have centred around how to safely facilitate family visits and offer social activities. Methods to support in-person visits during the pandemic have included: window visits, physically distanced outdoor visits, in-person visits in special rooms or containers with barriers in place, and physically distanced in-person visits in residents’ rooms or common areas. Technology (for example, telephone and video calls) can provide safe alternatives for staying connected to family members and friends but cannot replace face-to-face contact. Facilitating resident-family connections (whether they be in-person or virtual) requires a significant amount of time and effort from already overburdened staff. Ickert et al. (2020) estimate that a LTC home with 100 residents would require a minimum of 2 full-time and 1 part-time staff to provide most residents with a once-a-week visit with family for 30 minutes.

What was learned from this review

The following are key takeaway messages based on an analysis of what was learned:

- older Canadians are a heterogeneous population, and programs should be tailored to meet linguistic and cultural needs and delivered via a range of mechanisms (such as in-person, telephone, virtual, letter, etc.)

- a digital divide exists and there are sub-populations at risk of being further excluded during the pandemic as a result. Ensuring all Canadians have access to low-cost home internet and free internet in public spaces should be a priority

- intergenerational programs not only provide social benefits for older adults and younger people, but also have been shown to be effective at reducing ageism

- the development of partnerships that leverage the expertise and resources of stakeholders has contributed to the success of interventions

- government policies on LTC (for example, design of facilities, visitor policies, staffing levels) have a significant impact on the health and social lives of LTC residents. Policies should be reviewed with a focus on how they can balance disease mitigation and social connection needs

- in LTC facilities, adequate staff support is an essential enabler for visitation with families and caregivers (in-person or virtually), social activities, and coordinating with external organizations offering programs

- moving forward, ensuring the sustainability of successful interventions is a key issue. Many of the interventions being offered by community and non-profit organizations are supported by short-term funding, and sustainable funding sources are needed

The findings from this report highlight how federal, provincial, and territorial governments can influence the development of social isolation initiatives through their funding, large-scale coordination, knowledge sharing, and policy-making. Community and non-profit organizations were identified as being at the forefront of outreach and delivering services to vulnerable older adults. Businesses and academic institutions can also add their resources and expertise to interventions to support isolated older adults.

While there were limited formal evaluations of interventions to reduce the social isolation of older adults, anecdotal evidence and pre-pandemic evaluations suggest potential benefits of the following promising practices:

- Befriending programs: a small number of studies and anecdotal evidence suggest participation benefits both older adults and volunteers

- Telephone outreach programs and information lines: one pre-pandemic study has linked telephone outreach and help or information lines to reductions in social isolation. Anecdotal evidence suggests high call volumes during the pandemic

- Health promotion and wellness programs: pre-pandemic there was an emerging body of evidence supporting the provision of online caregiver support programs. Evidence of the effectiveness of other types of health promotion and wellness programs at reducing social isolation has been found, though these effects have been observed based on in-person versions of the programs

- Practical assistance programs: 2 pre-pandemic studies have linked the receipt of practical assistance (meal delivery) with reduced levels of loneliness. Anecdotal evidence suggests high rates of demand for these services

- Technology donation and training programs: anecdotal evidence suggests these programs have been successful at training older adults to use digital technology. A key enabler for their success is providing access to free internet

- Senior Centre Without Walls: to date, there have been 2 small evaluations of the Senior Centre Without Walls (SCWW) model, both of which reported reduced loneliness due to participation. Anecdotal evidence suggests consistent participation by older adults in SCWW and other virtual programs and positive feedback by participants

1. Introduction

In this section

1.1 COVID-19 and Canadian older adults – a “Gero-Pandemic”

The new Coronavirus (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease that was discovered near the end of 2019. COVID-19 has resulted in unprecedented high levels of disease and mortality, especially among vulnerable populations (Liu et al., 2020; Renu et al., 2020). The rapid spread of the disease has produced a global pandemic that has created new challenges for public health, continuing and long-term care (LTC) systems, community support organizations, businesses and the economy, families, and individuals. COVID-19 has been conceptualized as a “gero-pandemic,” defined as a disease that has spread globally with heightened significance and harmful consequences for older populations (Wister & Speechley, 2020).

As of the second week of April 2021, COVID-19 cases surpassed 1 million in Canada and reached almost 135 million cases worldwide. The number of deaths passed the 23,000 mark in Canada and has exceeded 2.9 million globally (Government of Canada, 2020a). One in 5 positive cases are among persons 60 years of age and older, and about 96% of deaths are among this age group (consult table 1). Furthermore, more than two-thirds of all deaths are occurring in LTC facilities or congregate and assisted living environments (Government of Canada, 2020a). Due to the impacts of COVID-19 on LTC facilities, almost 70% of older Canadians have reported their opinion has changed on whether they would place themselves or a loved one in LTC (National Institute on Ageing, 2020). Yet, those living in the community also face risk of infection, and the effects of the pandemic response (Cohen & Tavares, 2020).

| Age group | 0 to 19 | 20 to 29 | 30 to 39 | 40 to 49 | 50 to 59 | 60 to 69 | 70 to 79 | 80 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of COVID-19 cases | 17.7% | 18.8% | 16.1% | 14.7% | 13.3% | 8.4% | 4.7% | 6.3% |

| % of COVID-19 deaths | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 2.8% | 8.0% | 19.4% | 68.3% |

Source: Data from Government of Canada (2020a), current as of April 9, 2021.

To stop the spread of COVID-19, federal, provincial, and territorial governments have implemented various public health measures such as recommendations to engage in physical and social distancing; closure of non-essential businesses and public spaces; implementation of lockdowns and stay at home orders; mask mandates; travel restrictions; and restrictions on visitors to LTC facilities. While these measures have resulted in some successes in reducing transmission of COVID-19, they have also led to significant changes to the lives of Canadians. Concerns have been raised about the potential negative impacts the prolonged periods of physical and social distancing and reduced social interactions will have on Canadians, with specific attention paid to impacts on older adults (for example, Morrow-Howell et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020).

While age has become a major focal point in the pandemic (Morrow-Howell et al. 2020; Shahid et al., 2020), there are also other aspects that result in increased vulnerabilities to COVID-19 and the negative impacts of physical and social distancing policies. There is increased risk when age is coupled with pre-existing vulnerabilities such as:

- mental health conditions or lowered psychological well-being (Alonzi et al., 2020; Barber & Kim, 2020)

- physical health conditions (for example, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) (Mauvais-Jarvis, 2020; Mitra et al., 2020)

- the presence of 2 or more chronic illnesses (Wister, 2021a; 2021b)

- marginalization due to poverty; sexual orientation; race, ethnicity, or culture; immigration status; rural and remote environment; or other vulnerabilities (Wister, 2021a; 2021b)

While much research has focused on vulnerabilities to COVID-19, it is important to also recognize strengths and factors that contribute to individual, family, and community resilience. For example, some Indigenous reserve communities have utilized strong community connections and leadership to support pandemic mitigation strategies even though health care resources tend to be weaker (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools & National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health [NCCMT & NCCIH], 2020). Finally, it is also important to understand the broader social structures and environmental contexts in which these risk factors occur (Morrow-Howell et al., 2020). For example, in LTC settings, policies on visitation and funding for pandemic responses can influence individual level experiences and risks (Andrew et al., 2020). These organizational strengths and weaknesses can also be assessed using system resilience factors, for instance, the preparation, recovery, and adaptation levels of LTC during pandemic adversity (Klasa et al., 2021a; 2021b).

1.2 Purpose of report

The purpose of this report is to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted older Canadians, focusing on impacts related to social isolation. This report a) reviews academic and grey literature on social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic; b) assesses promising policies and programs that are reducing the social isolation of older Canadians during the pandemic; and c) summarizes the lessons learned, promising practices, and potential roles for governmental and non-governmental actors. The focus of the report is social isolation as it relates to aging in community; however, the report also includes a section examining social isolation in LTC settings.

This review summarizes the key literature on the pandemic to date; however, due to the scarcity of COVID-19 literature it was not possible to explore all topics in depth. The literature in this report is current up until the first week of April 2021. Due to the recentness of the pandemic, a range of academic and grey area data and information sources were considered, including lower level anecdotal and non-experimental evidence (such as case reports, news articles, expert opinion articles, program reports), since it was recognized there would be limited higher level experimental and review evidence. When evaluation data on programs and policies were not available, anecdotal evidence was considered as well as relevant pre-pandemic evidence from evaluations of similar style interventions. A data request was also made to the Canadian Longitudinal Study (CLSA) to access their COVID-19 study data pertaining to social isolation and loneliness.Footnote 1

The literature review begins by exploring unique considerations relevant to social isolation and certain sub-populations of older adults that may be particularly vulnerable during the pandemic. Next, the literature on the impacts of the pandemic on community-dwelling older adults is reviewed as it relates to social isolation. Finally, considerations for residents of LTC facilities specific to social isolation are discussed. Annexes 2 to 10 provide Canadian examples of the types of interventions discussed in the literature review. The annexes describe a range of programs that represent the diversity of communities, organizations, and pandemic responses in Canada. It is important to acknowledge that the annexes provide only a sampling of the many valuable programs being implemented to assist older Canadians during the pandemic.

The Age-Friendly Cities (AFC) frameworkFootnote 2 is used as an organizing framework for this report. The AFC framework is an initiative of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2007) that was developed in 2006 based on consultations held in 33 cities around the world (see figure 1 for a visual depiction of the 8 domains of age-friendly cities).Footnote 3

Figure 1 - Text version

The WHO’s Age-Friendly City framework consists of 8 domains:

- respect and social inclusion

- housing

- community support and health services

- transportation

- communication and information

- social participation

- civic participation and employment

- outdoor spaces and buildings

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) describes an age-friendly community as follows:

“in an age-friendly community, the policies, services and structures related to the physical and social environment are designed to help seniors ‘age actively.’ In other words, the community is set up to help seniors live safely, enjoy good health and stay involved”

(PHAC, 2016).

PHAC (2011) states that age-friendly communities support older adults by:

- recognizing the range of capacities and resources of older adults

- respecting the decision-making of older adults

- anticipating and flexibly responding to age-related needs

- supporting vulnerable older adults

- promoting the inclusion of older adults in all areas of community life

1.3 Social isolation and loneliness

1.3.1 Risk factors and consequences of social isolation among older adults

Social isolation is commonly defined as “a lack in quantity and quality of social contacts” and “involves few social contacts and few social roles, as well as the absence of mutually rewarding relationships” (Keefe et al., 2006, p.1). A closely related concept to social isolation is loneliness “defined as a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010, p.1). The key distinction between social isolation and loneliness is that social isolation refers to the objective level of social connections, whereas loneliness reflects the perception of being disconnected from others (Courtin & Knapp, 2015). While these 2 concepts often overlap, there can be unique associations; for instance, some older adults may not feel lonely even if they have low levels of social connectedness, and some people who seemingly have many social contacts feel lonely. For the purpose of this report, the term social isolation is used to refer to both the objective (for example, actual levels of personal connectedness) and subjective (such as feelings of loneliness) experiences of older adults, but where necessary differentiations between social isolation and loneliness are made to reflect distinct dimensions.

Social isolation is a common public health concern among community-dwelling older adults, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the risk of infection, the seriousness of the illness, and mitigation approaches including physical and social distancing (Shahid et al., 2020). Box 1 lists the negative health impacts social isolation is associated with for older adults. Older individuals experiencing social isolation have been shown to have lower access to health care services and lower health care utilization (Newall et al., 2015). Overall, given the wide-ranging impacts of social isolation on mortality, health, and quality of life, social isolation has received increasing attention in public health literature and gerontology literature, amid policy concerns around population ageing (Burholt et al., 2020; Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Fakoya et al., 2020; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017).

Box 1: Negative impacts of social isolation among older adults

- Reduced happiness, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being

- Increased anxiety, distress, and depression

- Poorer physical health

- Reduced engagement in healthy behaviours

- Higher mortality

Sources: Golden et al. (2009); Leigh-Hunt et al. (2017); Wister et al. (2019)

Those who experience various forms of vulnerability and marginalization in society are particularly at risk. Box 2 outlines risk factors and groups associated with social isolation. Taken together, the vulnerabilities experienced by older adults and significant negative impacts of social isolation have led to the development and implementation of many programs and services aimed at reducing social isolation (and loneliness), with many new or retrofitted approaches necessary during the pandemic. The program evaluation literature in this area even pre-pandemic has not been developed to the level required for meta-evaluation or meta-analyses (analyses that combine the results of multiple studies). Evaluation of the success of programs during the pandemic requires assessment of a range of lower-level anecdotal and non-experimental evidence.

Box 2: Risk factors and groups associated with social isolation

- Advanced age

- Living alone

- Low income or poverty

- Lack of affordable housing and shelter and care options

- Widowhood

- Episodic or lifelong physical and mental health issues (including Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias, frailty, sensory loss, or multiple chronic illnesses)

- Loss of sense of community

- Challenges relating to technology use (access to WiFi, costs, literacy, comfort)

- People living in rural or remote areas

- Immigrant or ethnic older adults – especially visible minorities

- Indigenous elders

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender seniors

- Caregivers with a heavy burden

Sources: De Jong Gierveld et al. (2015); Kirkland et al. (2015); National Seniors Council (2014a; 2014b; 2016); Newall et al. (2015); Wister et al. (2018)

1.3.2 The prevalence of social isolation during the pandemic

In order to estimate the increase in social isolation during the pandemic, we use unique data drawn from 3 separate waves of the CLSA: Baseline data (collected 2011 to 2015); Follow-up One data (collected 2015 to 2018); and data from the recent CLSA COVID-19 Study (collected April to December, 2020).Footnote 4 At the Baseline and Follow-up One time periods, feelings of loneliness are almost identical. Based on these data, it is estimated that, pre-pandemic, approximately 20% of older adults experienced loneliness some of the time or greater, and that about 10% experienced chronic or intense levels that are associated with negative health and well-being outcomes (Wister et al., 2018).

Turning to the CLSA COVID-19 Study, the rates increase significantly. Among older women aged 65 to 74 and 75 to 84, rates of loneliness are 41% and 42% respectively. For men, the rates also increased, but are lower than for women. Among men aged 65 to 74 and 75 to 84, 26% feel lonely at least some of the time. The increase in feelings of loneliness between the Baseline and COVID-19 (2020) time periods are striking. There is a 67% increase in loneliness for women aged 65 to 74, and 37% for those aged 75 to 84. Smaller increases are observed for men, where there is a 45% relative rise for men aged 65 to 74 and 33% for the oldest group (see Figure 2). The lower rates of loneliness among men, especially the oldest age group, may be indicative of stronger supports for this group, given that they are more likely to be partnered. Please see figure 3 for additional Canadian findings on the impacts of the pandemic from the CLSA.

Loneliness patterns by age and sex, CLSA

Loneliness Data Source: original analysis of CLSA Baseline, Follow-up one, and COVID-19 study data by authors.

Figure 2 - Text version

The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging surveyed older adults regarding if they felt lonely at least some of the time across 3 different time periods. The results of the CLSA are available in the following table:

| Age cohort | Baseline (2011 to 2015) | Follow-up one (2015 to 2018) | COVID-19 (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women 65 to 74 | 25 | 25 | 41 |

| Men 65 to 74 | 18 | 17 | 26 |

| Women 75 to 84 | 31 | 33 | 42 |

| Men 75 to 84 | 19 | 23 | 26 |

The rate of increase in loneliness over the course of the survey was:

- 67% for women aged 65 to 74

- 45% for men aged 65 to 74

- 37% for women aged 75 to 84

- 33% for men aged 75 to 84

The absolute percentage increase in loneliness among older adults ranged from 6% to 17%.

Note: absolute and rate of increases in loneliness were measured as changes from baseline to COVID-19.

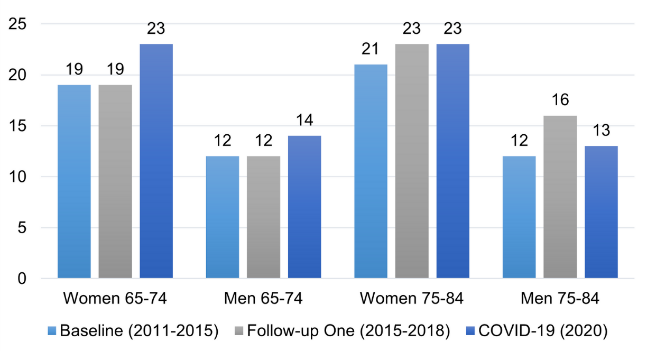

CLSA COVID-19 study findings

Depression Data Source: Original analysis of CLSA Baseline, Follow-up one, and COVID-19 study data by authors.

Source for all other data: CLSA COVID-19 Study Dashboard.

Figure 3 - Text version

The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging report surveyed older adults regarding if they felt depressed. Full results of the CLSA are available in the following table:

| Age cohort | Baseline (2011 to 2015) | Follow-up one (2015 to 2018) | COVID-19 (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women 65 to 74 | 19 | 19 | 23 |

| Men 65 to 74 | 12 | 12 | 14 |

| Women 75 to 84 | 21 | 23 | 23 |

| Men 75 to 84 | 12 | 16 | 13 |

From baseline to COVID-19, relative increases in rates of depression were between 8% and 21% depending on the age group and gender. Depression rose more among the 65 to 74 age group than the 75 to 84 group.

Other CLSA COVID-19 study findings are provided below.

- Caregiving: about 12% of persons aged 50 and over had problems providing caregiving to others

- Anxiety: rates of anxiety (mild, moderate, and severe) ranged from around 8% up to 25%, with higher rates among persons aged 65 to 74, especially women

- Family connection: about two thirds of women over the age of 65 felt separated from their family, compared to slightly over half of the men that age

- Access to supplies: among all age and gender groups, about 13% experienced difficulty obtaining necessary food and supplies

- Income: among all age and gender groups, 17% had a loss of income, with higher rates among older men

- Access to health care: among all age and gender groups, about 22% felt they were unable to access healthcare

Additional survey findings

The results of additional surveys also suggest older Canadians are experiencing high rates of social isolation during the pandemic:

- Gutman et al. (2021) surveyed Canadians aged 55 and up and they found 51% of respondents felt lonely some or most of the time (55% of women and 37% of men) and 57% felt isolated some or most of the time (60% of women and 46% of men). Women were more likely than men to follow social distancing guidelines most of the time, report changes in social support levels, and experience negative emotions

- a survey conducted by the National Institute on Ageing (2020) reported that 40% of Canadians aged 55 and up have experienced a lack of social connections and companionship during the pandemic

- a survey of retired teachers in Ontario (Savage et al., 2021) reported 43% of respondents felt lonely at least some of the time. Gender (female), living alone, being a caregiver, and being in fair or poor health were associated with increased odds of feeling lonely

Findings from the United States (US) also suggest increasing levels of loneliness during the pandemic. Several longitudinal studies have found patterns of increased loneliness experienced by older adults (Kotwal et al., 2020; Krendl & Perry, 2021; Luchetti et al., 2020). Generally, levels of loneliness tended to level off or decrease as the pandemic progressed; however, for some loneliness levels persisted or worsened (Kotwal et al., 2020; Luchetti et al., 2020). Kotwal et al. (2020) note that older adults experiencing worsening loneliness often report a lack of social support, difficulties accessing or using social technology, and challenges coping emotionally. On the other hand, those who experience little negative impact on loneliness report using technology, positive coping strategies, and access to municipal and community services.

Social isolation during the pandemic has been linked to negative outcomes for older adults such as depression (Krendl & Perry, 2021; Robb et al., 2020), sleep problems (Grossman et al., 2021), and anxiety (Robb et al., 2020). Feeling stressed or alone is associated with non-adherence with physical distancing recommendations (Coroiu et al., 2020). Experts have also expressed concern that physical distancing and isolation will lead to increased incidences of suicide among the elderly, and suggest interventions targeting social isolation can play a role in suicide prevention (Sheffler et al., 2021; Wand et al., 2020). Pandemic restrictions have also been associated with increased sedentary behaviour and decreased levels of exercise for older adults (Gutman et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2020).

2. Literature review: challenges faced by older adults during the pandemic related to social isolation

In this section

2.1 Social isolation and vulnerable sub-populations of older adults

2.1.1 People living with dementia

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the vulnerabilities of people living with dementia. Sources of care and social support have been reduced due to lockdown measures (for example, closure of health and community services, diversion of resources and efforts towards the pandemic, restrictions on contact with family and friends) (Alonso-Lana et al., 2020; Roach et al., 2020). People living with dementia may find it difficult to understand and comply with physical distancing and lockdown measures. Increases in neuropsychiatric symptoms (such as agitation, anxiety, depression) have been observed during the pandemic (Manca et al., 2020; Rainero et al., 2021; Roach et al., 2020). For example, an Italian survey of caregivers of people living with dementia found 55% reported declining cognitive functions of care recipients and 52% worsening of behavioural symptoms (Rainero et al., 2021). Furthermore, 69% of residents in LTC have dementia (Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], 2018), and as described previously the majority of COVID-19 deaths have taken place in LTC.

2.1.2 Ethnic minority and immigrant older adults

Analysis of neighbourhood mortality rates by Statistics Canada (2020a) suggests that COVID-19 infection rates are 3 times higher in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods and mortality rates are 2 times higher. Survey data from Statistics Canada (2020a) also suggests minority group members are experiencing higher unemployment rates and greater financial challenges due to COVID-19 compared to the general population. People of Asian visible minority groups have reported experiencing increased harassment and discrimination (Statistics Canada, 2020a). The pandemic has worsened the already existing disparities in health and access to services for ethnic minority and immigrant groups in Canada (Wang et al., 2019). Researchers from the US suggest that the social networks of minority groups are more likely to be disrupted by the pandemic (for example, higher COVID-19 mortality rates, disruptions to religious and cultural activities, less likely to use technology) (Gauthier et al., 2020).

To help ensure equity, it has been suggested that social isolation interventions should be developed with vulnerable and minority groups (Dassieu & Sourial, 2021). For example, participation at places of worship and religious activities are particularly important for some ethnic minority groups and should be incorporated into pandemic interventions (Chatters et al., 2020; Gauthier et al. 2020; Giwa et al., 2020). Religious organizations can work with their community members to offer remote outreach, support, and services to older adults (Chatters et al., 2020).

2.1.3 Rural, remote, and northern communities

Older adults living in rural and remote communities face unique circumstances that present additional pressures during the pandemic: limited access to health care services; housing that is overcrowded, older or of poor quality; communities that are facing economic insecurity; less access to technology and high-speed internet services; and limited infrastructure to assist with daily tasks (for example, grocery shopping, transportation) (Henning-Smith, 2020). These circumstances pose challenges for pandemic responses and also mean these communities may face greater challenges when recovering from the pandemic (Henning-Smith, 2020). Furthermore, activities and services for older adults in rural areas are often offered by small seniors clubs and groups with limited funds and resources. For example, on Prince Edward Island, logistical challenges such as regular meeting spaces being unavailable or too small for social distancing and being unable to afford to heat buildings without fundraising gatherings create challenges for in-person activities, while at the same time lack of access to digital infrastructure make virtual activities impractical in many areas. Some groups have adapted by, for example, decreasing the size of activities and not serving food in order to safely hold activities in-person (personal communication, P.E.I. Senior Citizens' Federation).

However, the more tight-knit nature of rural communities is a strength, and older Canadians living in rural communities report higher levels of social support than urban residents (Frank, 2020). For example, in Clarenville, Newfoundland, the town and local groups and organizations have taken steps to support the community during the pandemic such as: organizing physically distanced hikes, creating an outdoor skating rink and sliding area, offering free grocery delivery, and running a free pancake breakfast each week (with takeout options) (personal communication).

While Northern communities have seen limited cases of COVID-19 for most of the pandemic, the lack of health care infrastructure makes them particularly vulnerable to the impacts of outbreaks if they occur. Older adults living in Northern communities face similar circumstances as those described above for rural and remote communities, but also may face additional concerns such as food insecurity, fragile supply chains, access to water for handwashing and cleaning, housing shortages and overcrowding, and high rates of tuberculosis (Arctic Council, 2020; Fryer & Collier, 2020; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2020).

2.1.4 Indigenous peoples

Pre-existing vulnerabilities such as geographic isolation, lack of access to medical and community care, and high rates of chronic conditions make COVID-19 a disease of particular concern for Indigenous communities in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2020b). In response to the pandemic, many Indigenous people are drawing upon traditional practices and culture and taking steps to protect their elders and communities. For some Indigenous peoples, isolation of the community or family groups is a traditional practice that has been used in the past to safeguard the wellbeing of the community. Rules on community entry, self-isolation trailers, and family groups returning to the land are examples of ways Indigenous peoples have responded to the pandemic (Banning, 2020; NCCMT & NCCIH, 2020).

The pandemic has had a significant impact on cultural activities since it has not been possible to hold large cultural gatherings and elders are not able to participate in regular intergenerational and cultural activities (Assembly of First Nations, 2020). It is important to acknowledge that past bans on Indigenous cultural and spiritual ceremonies were a source of trauma for Indigenous peoples (First Nations Health Authority, 2020). During the pandemic, the First Nations Health Authority (2020) has suggested embracing alternative or adapted cultural activities such as: spending more time on the land; connecting to the Creator; modifying ceremonies or cultural practices so they follow COVID-19 guidelines or holding them with only your household; and providing bagged lunches rather than shared meals at small events. It has also been suggested that sustained COVID-19 funding should be provided to encourage participation in on the land activities and continued connection to culture (Assembly of First Nations, 2020).

As we move into the vaccine phase of the pandemic response, resistance to mainstream health care may pose a challenge in some Indigenous communities due to historical negative experiences (Funnell, 2021). Indigenous communities have been prioritized in the vaccine roll-out, and many communities have relied on key opinion leaders and elders in the community to support vaccine compliance and uptake.

2.1.5 LGBTQ2

Lack of social support and isolation, past traumas and experiences of discrimination, and disparities in health and access to health services contribute to an increased level of vulnerability for LGBTQ2 older adults during the pandemic (Jen et al., 2020). However, past experiences living through the HIV and AIDS pandemic are a potential source of resilience, with lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults reporting feeling prepared and more ready to act during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of their past experiences (Gutman et al., 2021).

Based on survey data collected during the pandemic, Gutman et al. (2021) found no differences in reported levels of loneliness between lesbian, gay, and bisexual and heterosexual Canadians aged 55 and up; however, lesbian, gay, and bisexual Canadians reported worse mental health (such as depression, anxiety, and sadness) than the general population. They also were more likely to have no one to turn to if they needed help, suggesting an increased need for practical help during the pandemic.

2.1.6 Caregivers

The pandemic has increased the pressures being placed on informal caregivers in Canada (for example, providing more hours of care, decreased social support, difficulties accessing health care services) (Anderson & Parmar, 2020; Ontario Caregiver Organization, 2020). A survey of Ontario caregivers found 43% often feel isolated and lonely, while a survey in Alberta found 86% of caregivers have experienced loneliness since the pandemic began (Anderson & Parmar, 2020; Ontario Caregiver Organization, 2020). Analysis of data from a large study in the United Kingdom (UK) found that higher levels of loneliness during the pandemic resulted in a 4 times higher risk of depression for caregivers (Gallagher & Wetherell, 2020).

2.1.7 Low-income older adults

As many services and programs transition to virtual modes of delivery during the pandemic, low-income older adults are particularly at risk of isolation as they may not be able to afford access to digital technology and high-speed internet (Conroy et al., 2020). Data from Statistics Canada shows only a little over half of low-income Canadians use the internet (Davidson & Schimmele, 2019), creating a “digital divide” (a term referring to the divide in uptake and access to digital technology). Low-income older adults also report having less social support available than other older adults (Frank, 2020).

2.2 Social isolation and community-dwelling older adults

2.2.1 Respect and social inclusionFootnote 5

Ageism and the risks of treating older adults as a homogeneous group

During the pandemic, both positive (for example, community initiatives to support older adults, building social connections) and negative (for example, ageism, discrimination in the healthcare system) responses towards older adults emerged (Monahan et al., 2020). Positive responses promote intergenerational solidarity and positive views about aging, while negative responses can cause immediate harm (such as neglect of older adults in LTC) and also have potential long-term impacts on attitudes towards aging (Monahan et al., 2020). Ageism can increase feelings of loneliness and social isolation among older adults and is a risk factor for lower number and quality of social relationships (WHO, 2021). During the pandemic, negative self-perceptions of aging have been associated with loneliness and psychological distress (Losada-Baltar et al., 2021). Ageism has also been associated with higher levels of anxiety during the pandemic (Bergman et al., 2020a).

Experts state that the portrayal of older adults as a homogeneous, vulnerable group during the pandemic has intensified ageist views and intergenerational tensions (for example, Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020; Meisner, 2020; Wister & Speechley, 2020). COVID-19 has been presented as primarily a problem for older adults, rather than a shared societal challenge (Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020). An experiment conducted by Yildirim (2020) highlights the negative effects of such messaging. Participants who viewed a video framing the pandemic as primarily a risk to older adults were more likely to perceive the pandemic as posing little risk to themselves and were more likely to favour saving the economy over human lives.

New forms of age segregation, but intergenerational connections are emerging

The pandemic has also increased age segregation within communities, with few opportunities for older adults to safely interact with younger generations (Burke, 2020). A report from the UK highlights the challenges intergenerational programs are facing during the pandemic: the closure of intergenerational spaces, the digital divide, challenges adapting programs to the digital world, and narratives about conflicts between generations (InCommon & Clarion Futures, 2020).

Intergenerational activities have been recommended as a means to reduce feelings of social isolation (Day et al., 2020; Jopling, 2020). Intergenerational contact and friendships can also protect against ageism (WHO, 2021). As highlighted in the annexes, many programs to reduce social isolation among older adults during the pandemic have intergenerational components. Befriending programs in particular have sought to forge connections between older and younger generations (consult Annex 2). While there has been limited evaluation of the intergenerational programs implemented during the pandemic, recent systematic reviews suggest potential benefits for loneliness and social isolation though the evidence to-date is quite limited (Peters et al., 2021; Zhong et al., 2020). It is also encouraging that there have been many grassroots initiatives and expressions of intergenerational solidarity during the pandemic (Burke, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020; Morrow-Howell, 2020). The pandemic has also motivated families to make greater and more sustained efforts to stay in contact and connect with each other (Hwang et al., 2020; Morrow-Howell, 2020).

Concerns that the pandemic is increasing vulnerabilities to elder abuse

Social isolation is a key risk factor for elder abuse (Pillemer et al., 2016). Experts have expressed concerns that circumstances during the pandemic such as physical distancing, closures of sources of social support, the increased dependency of older adults, pressures on caregivers, financial uncertainty, and escalating ageism will increase the risks of elder abuse (Elman et al., 2020; Han & Mosqueda, 2020; Makaroun et al., 2021). Organizations in the US that support elder abuse victims have adapted to the pandemic by offering remote services and conducting telephone outreach to vulnerable older adults (Elman et al., 2020). D’cruz and Banerjee (2020) have advocated for the development of helplines for elder abuse reporting, information provision, and emotional support. In Canada, helplines and telephone programs provide older adults with a range of information and supports, including information on elder abuse (consult Annex 3).

2.2.2 Housing

Older adults living alone are particularly at risk

Research suggests that older adults living alone are more likely to experience increased loneliness during the pandemic (Emerson, 2020; Savage et al., 2021). Data from Statistics Canada shows older adults living alone are less likely to have social support available (Frank, 2020), suggesting a greater need for practical help. Analysis of survey data by Fingerman et al. (2020) suggests that during the pandemic US older adults living alone primarily have relied on increased contact with friends. While Fingerman et al. (2020) found in-person contact had a positive effect on older adults living alone, speaking on the telephone resulted in negative effects, possibly because it made older adults more aware of their isolation. More research is needed to better understand these patterns.

Risks in social housing settings

Low-income older adults living in social housing (many of whom live alone) have also been identified as a vulnerable group during the pandemic (Archambault et al., 2020; Pirrie & Agarwal, 2021). However, social housing settings provide the opportunity to reach many vulnerable older adults with interventions (consult annexes for examples). Some of the recommendations for supporting older adults in social housing include identifying high-risk buildings and populations; delivering food and essential supplies; developing communication systems to keep residents informed; ensuring safety protocols for common areas; providing safe opportunities for social activities; and ensuring access to the internet (Archambault, 2020; Pirrie & Agarwal, 2021).

Risks in non-institutional congregate living settings

While less policy attention has been paid to non-institutional congregate living settings (for example, assisted living, continuing care retirement communities, independent living communities) than LTC, many of the residents are vulnerable to COVID-19 and there are limited regulations and guidance for their safety (Coe & van Houtven, 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2020). A large British Columbia (BC) survey found that 57% of assisted living residents were confined to their room at some point during the pandemic (Office of the Seniors Advocate British Columbia, 2020) (consult section 2.3.1 for description of the negative impacts of isolation in LTC or assisted living settings). These types of housing operate based on social models of care, and residents are used to high levels of autonomy, regular excursions outside of the facility, and frequent social interactions. As a result, COVID-19 restrictions may be particularly challenging for residents to adapt to (Zimmerman et al., 2020). Experts suggest non-institutional congregate living settings can help residents to stay connected by offering scheduled times to use shared technology, organizing virtual group activities, providing one-on-one support, and involving residents in decision-making about COVID-19 restrictions (Gray-Miceli et al., 2020; Hill et al., 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2020).

2.2.3 Community support and health services

Community support and health services are adjusting to the pandemic

As a result of the pandemic, disruptions have occurred to regular community support and health care services, cutting off older adults from important sources of social support (Meisner et al., 2020; Morrow-Howell, 2020). For example, in a survey of Alberta caregivers 48% reported reductions in publicly subsidized home care services due to the pandemic (Anderson & Parmar, 2020). Home care workers can be an important source of social interaction for older adults, and prior to the pandemic, research has found unmet home care needs are associated with higher levels of loneliness (Kadowaki et al., 2015).

Many community and health organizations have been quick to transition services to virtual and telephone models, though these are not workable alternatives for all older adults. Lam et al. (2020) estimate that in the US 38% of older adults are unready for video-based visits (primarily due to physical disabilities and technological challenges) while 20% are unready for telephone visits (primarily due to physical disabilities). PHAC (2020) recommends both digital and low-tech telephone health care appointments be made available. Some evidence-based health promotion interventions have also transitioned to remote delivery (consult Annex 4). While programs such as Choose to Move and Minds in Motion have not been assessed in the remote format, previous evaluations suggest they positively impact loneliness and mental wellbeing (Franke et al., 2021; Regan et al., 2017). For some older adults, home visits by health professionals may also be appropriate to provide health care services, as well as to initiate health promotion initiatives (Carr et al., 2020; Day et al., 2020).

Social prescribing programs as an emerging practice

In recent years, social prescribing programs where health professionals refer patients to community navigators who assist them to access community supports and services have been an emerging trend to reduce social isolation. In Ontario, a pilot of social prescribing programs at 11 community health centres conducted over 2018 to 2019 found 49% of clients reported decreases in loneliness (Alliance for Healthier Communities, 2020). As described in Annex 4, during the pandemic social prescribing programs have been used to connect vulnerable older adults with needed services and social supports.

Importance of mental health supports during the pandemic

Mental health support for older adults and their caregivers is crucial during the pandemic. In Canada, many mental health and caregiver organizations have been able to move their services online and offer telehealth, online support groups, and peer-based counselling (Flint et al., 2020) (consult Annex 4 for examples). Prior to the pandemic providing caregiver supports online was an emerging practice, and a review of these programs found feeling less alone was a benefit of participation (Armstrong & Alliance, 2019). For some older adults, loneliness may be psychologically-based, in which case one-on-one counselling, meditation, cognitive behavioural interventions, and other psychosocial interventions are needed (Conroy et al., 2020; Van Orden et al., 2020). It also has been suggested that health professionals can assist older adults to develop “Connection Plans” to plan how they can maintain social contact (Van Orden et al., 2020). Mental health is an especially challenging barrier for older adults who have lost a loved one to COVID-19 since it intensifies other problems. Virtual funerals, remote support from hospice workers and volunteers, and peer support or friendly telephone calls are suggested to help older adults to cope with their loss and reduce feelings of loneliness (Carr et al., 2020).

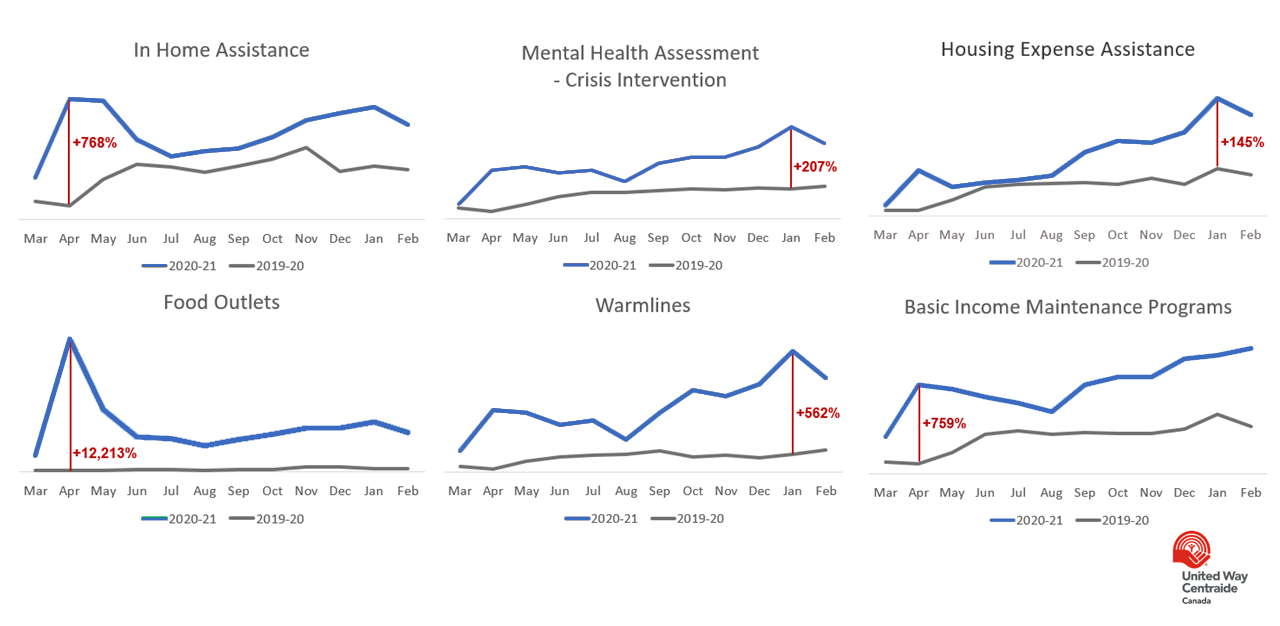

High levels of demand for practical assistance

Practical assistance is an important need for vulnerable older adults, who may feel unsafe going out in the community or be cut off from regular sources of social support. During the pandemic, the New Horizons for Seniors Program (NHSP) and Emergency Community Support Fund (ECSF) have both provided substantial funding to community agencies to provide services to support vulnerable older adults (for example, grocery delivery, outreach to address social isolation) (United Way Centraide Canada, 2020a; 2021). The Province of British Columbia and the City of Edmonton are 2 regions where large-scale coordinated responses were implemented to meet the needs of older adults (consult Annex 5 for more details). In British Columbia, Safe Seniors, Strong Communities provides older adults across the province with access to check-ins, grocery shopping, meal delivery, and prescription delivery (Hannah, 2020). In Edmonton, a coordinated pandemic response focusing on 3 areas (food and transportation, outreach and friendly checks-ins, and psychosocial support) was implemented to identify gaps, develop or expand needed programs, and facilitate referrals between organizations (Coordinated Pandemic Response Steering Committee, 2020).

Programs providing practical assistance often include social components. For example, volunteers delivering meals or groceries can provide friendly conversation and information to isolated older adults. Although the evidence is limited, findings from 2 pre-pandemic US studies suggest that meals on wheel style programs can be effective at reducing loneliness among older adults (Thomas et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2015). Practical assistance programs can also help older adults to care for their pets (for example, buying pet food, walking dogs) who provide an important form of companionship for isolated older adults (Rauktis & Hoy-Gerlach, 2020). Practical assistance programs have made various adaptations to their procedures and operations in order to continue to safely provide services during the pandemic.

2.2.4 Transportation

Declining use of public transportation services during the pandemic

While many activities have moved online during the pandemic, it is still essential that older adults have options available for travelling outside of the home to meet their daily and social needs. However, at advanced ages, many older adults do not drive and public transportation, volunteer driver programs, and ridesharing options all carry a degree of COVID-19 risk (DeLange Martinez et al., 2020).

Surveys conducted in the early months of the pandemic with frequent transit users found 55% of older adult transit users in Toronto and 54% in Vancouver stopped using transit during the pandemic (Palm et al., 2020a; 2020b). Research from the Older Adults’ Centres Association of Ontario (OACAO) suggests only 37% of transit users would feel comfortable using public transportation to travel to an older adult centre during the pandemic (OACAO, 2020).

Municipal and community transportation programs

In the US, some municipalities have implemented shuttle services especially for older adults with enhanced safety measures as an alternative to public transportation (DeLange Martinez et al., 2020). Numerous volunteer driver programs for older adults are continuing to operate in Canada during the pandemic, but some are struggling with volunteer recruitment as they often rely heavily on older adult volunteers (for example, CBC News, 2021; Weldon, 2020). Some transportation programs have also implemented or enhanced grocery and meal delivery programs to assist older adults who are choosing to isolate themselves at home, as described in the previous section (consult Annex 5).

2.2.5 Communication and information

Growing internet and digital technology use by Canadian older adults

Internet use by older Canadians has been steadily increasing over time. Statistics Canada reports that use of the internet by older adults increased from 32% to 68% over 2007 to 2016; however, there is a significant age gradient as less than half of those aged 80 and up use the internet (Davidson & Schimmele, 2019). Data collected during the pandemic suggests older adults are continuing to become more comfortable with digital technology, although an age gradient remains:

- a poll of Canadian older adults found that 88% use the internet daily, 65% own a smartphone, and 72% feel confident using technology. Increases in the use of video calls, social media, online activities, and food delivery services were reported due to the pandemic (AgeWell NCE., 2020a)

- according to CLSA (2021) data, 83% of older adults isolating at home used the telephone to stay in contact during the pandemic, 48% video calls, and 44% social media. Significant age gradients existed for the use of video calls and social media, with those aged 85 and up the least likely to use them (for example, 64% of people 65 to 74 used video calls compared to 31% of those 85 and up)

With the growing use of digital technology by older Canadians, video calls and social media have been incorporated into interventions to reduce social isolation. Video call technologies (for example, Facebook Messenger, Zoom, etc.) can be used both to connect with family and friends, as well as to participate in group meetings and activities (AgeWell NCE., 2020b; Conroy et al., 2020). Social media sites can be used to maintain and build social networks (Conroy et al., 2020). Reviews of the impacts of digital technology use on older adults suggest it has positive impacts on components of social isolation (such as increasing contact with family, intergenerational relationships), but evidence of the impacts on loneliness has been less consistent (Chen & Schulz, 2016; Damant et al., 2017; Ibarra et al., 2020). The associations specifically between social media and social isolation are unclear, as Hajek and König (2020) reviewed the small amount of literature on this topic and found only 1 study reported reductions in social isolation scores for older adults. There are also many resources available on the internet that can help to connect older adults to needed services and supports (for example, the Islanders Helping Islanders Volunteer Services Directory on PEI, Volunteer NS in Nova Scotia).

Barriers and facilitators of digital technology adoption

Benoit-Dubé et al. (2020) and Gorenko et al. (2021) have highlighted potential barriers and facilitators of digital technology adoption for older adults during the pandemic:

- perceived benefits of using the technology

- access to and affordability of the technology

- attitudes, self-confidence, and knowledge about using technology

- whether the technology is suitable for people experiencing physical and cognitive declines

- whether assistance is available from others (for example, family, staff, technical support) to use the technology

In a survey of municipal, community, and health organizations in Ontario, the most common barriers for technology use by older adults that organizations reported were limited access to the internet, lack of knowledge on the use of technology, and the need for assistance with setting up technology (Ontario Age-Friendly Communities Outreach Program, 2021a).

A digital divide continues to exist in Canada

While the majority of older Canadians use digital technology, researchers have identified segments of the population who are less likely to use or have access to high-speed internet and digital technology. These populations include low-income older adults (Conroy et al., 2020; Davidson & Schimmele, 2019); people living in rural, northern, and Indigenous communities (Conroy et al., 2020; Ryerson Leadership Lab, 2021); and older adults with physical disabilities or cognitive impairments that present challenges for using technology (Lam et al., 2020; Lee & Miller, 2020). For people without access to home internet, public spaces such as libraries and community centres are often used to access the internet, but many of these have been closed during the pandemic (Ryerson Leadership Lab, 2021). Furthermore, digital technology options may not be well suited to meet the needs of older adults who are unfamiliar with digital technology, have lower literacy levels, or are from linguistic minority groups (Hebblethwaite et al., 2020).

Digital technology training and access are needed to overcome the digital divide

To overcome the digital divide, there is a need for digital technology education and training programs for older adults, as well as access to low-cost technology and high-speed internet services (Conroy et al., 2020; Day et al., 2020; Science and Technology for Aging Research, 2019; Sixsmith, 2020; Son et al., 2020). In the US, to ensure equity in access to digital technology, some communities have developed digital inclusion plans (for example, offering low-cost internet and affordable devices, providing tech support in multiple languages) (DeLange Martinez et al., 2020). Programs that provide training and access to digital technologies are being implemented or expanded in Canada (consult Annex 6). In Nova Scotia, prior to the pandemic, the government provided funding for internet and digital literacy pilots for community-dwelling older adults, including programs targeting Indigenous and African Nova Scotian communities. An evaluation of a pre-pandemic tablet training program for older adults in Ontario found the program improved attitudes towards technology and use, but no changes for loneliness or social isolation were observed (Neil-Sztramko et al., 2020). However, the results of the study were likely hampered by its small sample size. During the pandemic, a study by Rolandi et al. (2020) in Italy found older adults who had completed a social networking course prior to the pandemic were less likely to report feeling left out, though no differences in loneliness were observed.

With increasing digital technology use, it is vital to ensure that older adults are aware of potential technology-related frauds and scams. In the US, older adults are increasingly being targeted with tech support, text messaging, and internet service scams (Payne, 2020). It is also important to educate older adults about the importance of examining the quality and accuracy of online information since Statistics Canada data shows people aged 55 and up are the most likely to share COVID-19 misinformation online (Garneau & Zossou, 2021).

Low-tech interventions remain important for reaching isolated older adults

For some older adults, low-tech telephone-based interventions may be the most practical and appropriate options (for example, if the older adult prefers not to use computers, lacks access to high-speed internet, etc.) (Conroy et al., 2020). A review of the pre-pandemic literature found social activities, educational sessions, and befriending programs can be successfully conducted over the telephone (Gorenko et al., 2021).

Many telephone help and information lines have received enhanced funding during the pandemic due to high call volumes. For example, funding from the federal government has expanded 211 telephone information and referral services to all jurisdictions in Canada (United Way Centraide Canada., 2020b). Telephone lines and telephone outreach programs can provide friendly conversation and play an essential role in connecting older adults to organizations offering services to reduce social isolation (consult Annex 3). Pre-pandemic, interviews with staff and users of a seniors helpline in the UK revealed that older adults often called the helpline to seek friendly conversation and alleviate loneliness (Preston & Moore, 2019). During the pandemic, reported benefits of telephone outreach programs in the US have included positive emotions and connecting older adults to needed services (Office et al., 2020; Rorai & Perry, 2020). Telephone outreach programs also provide volunteer opportunities for older adults, as they can be trained virtually to become telephone volunteers (Lee et al., 2021). Institut national de santé publique du Québec [INSPQ] (2020) notes that in addition to the telephone, additional creative methods should be employed to reach isolated older adults (for example, providing information in the mail, working with health professionals and essential services to coordinate outreach).

2.2.6 Social participation

There has been a shift to remote modes of social participation

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the operations of senior centres, fitness centres, libraries, restaurants, and many other places older adults go to participate socially. While some of these places have been able to remain open with safety precautions in place, older adults may still feel uncomfortable visiting them. Many organizations have switched to the remote delivery of services and programs (consult Annex 7). Examples of activities that can be offered remotely include book clubs, discussion groups, social games, creative arts, group health promotion initiatives, lectures, and virtual tours and cultural opportunities (Day et al., 2020; Hebblethwaite et al., 2020; INSPQ, 2020; Son et al., 2020).

Evaluations of virtual programs for older adults conducted prior to the pandemic suggest that they can reduce social isolation (Botner, 2018; Gorenko et al., 2021). The OACAO (2020) conducted a province-wide survey of participants at older adult centres and found 35% were now participating in virtual programming. For those who did not participate in virtual programs, the main reasons were lack of interest (52%) and discomfort with using the technology (32%). Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2021) conducted a telephone survey of older Israelis on their participation in Zoom activities during the pandemic. They identified physical activity, social interaction, and relief from boredom and loneliness as the central factors influencing participation. Key factors leading to non-participation included awareness, technological difficulties, and convenience of program times and dates.

Rapid spread of the Senior Centre Without Walls model

Senior Centre Without Walls (SCWW) is a model of offering remote programs (either by telephone or virtually) that has been widely adopted by community and non-profit organizations in Canada during the pandemic (consult Annex 7 for examples). The first SCWW in Canada was launched in Manitoba in 2009 by the organization A & O: Support Services for Older Adults and provided isolated older adults with access to telephone-based social and educational activities. A process evaluation of the program found that it was successful in reaching isolated older adults and participants felt more connected and less lonely (Newall & Menec, 2015). The SCWW at Edmonton Southside Primary Care Network (no date) is another pre-pandemic SCWW, and a pre- and post-evaluation of the program found statistically significant declines in loneliness scores (for high users of the program) and declines in anxiety and depression scores. Over half of participants also reported making new friends due to the program. Prior to the pandemic, the Government of Alberta provided a grant to the Edmonton Southside Primary Care Network to work with other communities to expand the SCWW model in the province. The Government of Ontario has provided $467,500 to the OACAO to disburse as micro-grants to support the development of SCWW programs during the pandemic.

Befriending programs are an emerging trend

Befriending programs have commonly been implemented by community members and non-governmental organizations to reduce the social isolation of older adults during the pandemic (consult Annex 2). In befriending programs, volunteers regularly engage in friendly visits with older adults (most programs have switched to remote visiting). An evaluation of a 6-week program implemented in the US during the pandemic found both students and older adults reported benefits and 66% of pairs continued to stay in contact after the program ended (Joosten-Hagye et al., 2020). Previously, in an evaluation of a UK telephone befriending program older adults reported the alleviation of loneliness and isolation as an outcome of participation (Cattan et al., 2011).

Encouraging physical activity during the pandemic

Due to the evidence linking higher levels of physical activity with better immune system function, reduced opportunities to participate in physical activities during the pandemic is an important concern (Damiot et al., 2020; Scartoni et al., 2020). Gutman et al. (2021) found that 37% of Canadians 55 and up reported declining levels of exercise during the pandemic. While there are various exercise videos available online, recreation staff can also offer online classes to provide opportunities for social connections (Son et al., 2020). Older women particularly would benefit from online classes, since past research suggests they prefer to exercise in social settings (Gutman et al., 2021). It has also been suggested that the feel of community can be created for people participating in individual physical activities, for example, by setting group goals or holding friendly competitions (Son et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2020). Consult Annex 4 for examples of remote and outdoor physical activities during the pandemic.

Community and non-profit organizations are facing challenges adapting to the pandemic