Preventing and responding to the mistreatment of older adults: Gaps and challenges exposed during the pandemic

From: Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors Forum

Alternate formats

Preventing and responding to the mistreatment of older adults: Gaps and challenges exposed during the pandemic [PDF - 648 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQI+:

- Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and additional terminologies

- AQRP:

- Association québécoise des retraité(e)s des secteurs public et parapublic

- CASI:

- Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing

- CINAHL:

- Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- COVID-19:

- Corona Virus Disease of 2019

- CSBE:

- Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être

- CSQ-FSQ:

- Fédération de la santé du Québec

- FPT:

- Federal, Provincial, Territorial

- ID:

- Identity Document

- IT:

- Information Technology

- LTC:

- Long-Term Care

- MOA:

- Mistreatment of older adults

- N/A:

- Not Applicable

- PPE:

- Personal Protective Equipment

- PSW:

- Personal Support Worker

- WHO:

- World Health Organization

List of figures

- Figure 1: Overall, it has been challenging to prevent at-risk older adults from experiencing MOA throughout the pandemic

- Figure 2: Service workers (healthcare, social service) have had difficulty reaching out to or connecting with at-risk older adults throughout the pandemic, including periods of stay-at-home or self-isolation mandates

- Figure 3: Overall, the process of identifying or detecting older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA throughout the pandemic has been a challenge

- Figure 4: Use of remote or virtual forms of live interpersonal service delivery such as telephone or video-conferencing platforms throughout the pandemic have made it challenging to identify and detect older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA

- Figure 5: Older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA have faced greater difficulties help-seeking or reaching out to services throughout the pandemic

- Figure 6: Overall, the system of response in the community for addressing and supporting cases of MOA throughout the pandemic has been challenged

- Figure 7: Social distancing requirements and restrictions to in-person services (for example, medical, social services, legal) throughout pandemic have made it challenging to effectively respond to and support older adults experiencing MOA

- Figure 8: Maintaining collaborative and coordinated efforts with community partners and networks toward responding to or supporting older adults experiencing MOA has been a challenge throughout the pandemic

- Figure 9: Overall, gaps have existed at systemic or structural levels as it relates to addressing or preventing MOA throughout the pandemic

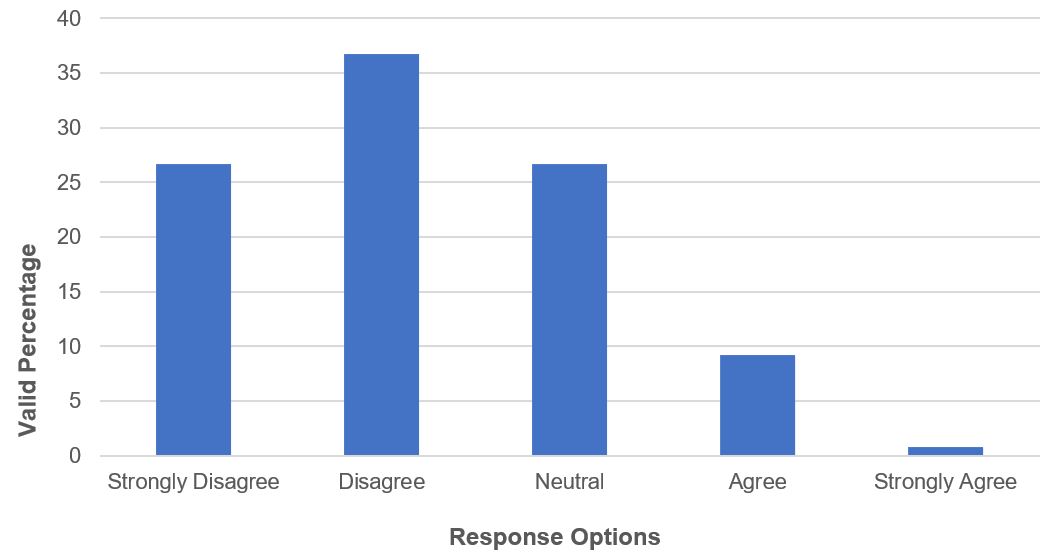

- Figure 10: Older adults from diverse communities, social locations, socio-economic statuses, and geographic areas have been able to access remote forms of communication and service delivery throughout the pandemic

List of tables

- Table 1: Descriptive sample characteristics

- Table 2: Survey responses on items related to primary prevention

- Table 3: Survey responses on items related to MOA identification and detection

- Table 4: Survey responses on items related to MOA response and support intervention

- Table 5: Survey responses on items related to centralized or systemic support

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

*Québec contributes to the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Québec.

Acknowledgements

Prepared by:

- David Burnes, PhD, Canada Research Chair in Older Adult Mistreatment Prevention; Associate Professor, University of Toronto, Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work; Affiliate Scientist, Baycrest, Rotman Research Institute; and

- Professeure Marie Beaulieu, Ph.D., MSRC/FRSC; Co-Director, WHO Collaborative Centre, Age Friendly Communities/Elder Abuse; Retired Professor and Associate, Université de Sherbrooke, School of Social Work; Associate Researcher, Research Centre on Aging, CIUSSS Estrie-CHUS;

- for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors.

The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

Executive summary

People who have fought pandemics know it: things never go perfectly. In the turmoil, successes are unnoticed and the losses leave scars.

There are those who will be looking for villains—politicians, care home operators, workers who walked off the job. But the real villain in this tragedy is society’s profound and long-standing neglect of elders. A reckoning is in order.

Mistreatment of older adults (MOA) is a pervasive issue in our society that carries serious consequences. Approximately 1 out of every 10 Canadian older adults living in the community experiences some form of MOA each year. The scope of this problem is increasing in accordance with older adult population growth. MOA victimization is associated with detrimental individual consequences, such as:

- premature mortality

- physical or mental health morbidities

- financial hardship

It is also associated with societal costs such as increased rates of healthcare utilization.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the issue of MOA, as well as efforts to prevent and respond to MOA. The pandemic triggered a set of circumstances that magnified known MOA risk factors, such as social isolation and dependency on others. In turn, both the prevalence and severity of MOA increased substantially during the pandemic. The elevated rates and intensified levels of MOA during the pandemic highlighted a need to identify the gaps and challenges that exist in our systems of MOA prevention and intervention response. An understanding of these gaps and challenges will inform future work that is focused on the development of effective prevention and response strategies.

The objective of this project was to identify gaps and challenges in preventing and responding to MOA in Canada, more specifically, gaps and challenges that were exposed or exacerbated during the pandemic. This project undertook the following 2 strategies to meet this objective:

- a comprehensive review of the literature focusing on MOA prevention and response during the pandemic

- a survey of stakeholders across Canada directly involved in MOA prevention or response throughout the pandemic

The comprehensive literature review examined peer-reviewed articles from several databases and grey literature sources such as government and non-governmental organizational reports. The review was conducted in both English and French. Informed by literature review findings, the stakeholder survey followed a mixed-methods, computer-assisted self-interviewing approach with a final analytic sample of 249 stakeholders across provinces and territories in Canada. In both the comprehensive literature review and stakeholder survey, findings about gaps and challenges were organized according to the following categories that represent key phases or considerations in MOA prevention and response:

- primary prevention (preventing the initial occurrence of MOA)

- identification and detection (identifying older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA)

- response and support intervention (direct response intervention designed to support older adults experiencing MOA)

- centralized systemic or structural supports

Based on the comprehensive literature review and stakeholder survey, a summary of key gaps and challenges related to MOA prevention and response exposed during the pandemic (detailed throughout the report) are as follows:

- MOA awareness-raising efforts targeted toward the general public or professionals who work with older adults were insufficient throughout the pandemic. This includes training to recognize signs of MOA. Awareness-raising initiatives would have benefited from a more tailored approach that accounted for the varying needs and experiences of older adults from diverse communities

- older adults experienced levels of social isolation above and beyond the social distancing requirements affecting the entire population. This substantially elevated their risk of mistreatment. Older adults experienced these heightened levels of social isolation and MOA risk while simultaneously facing barriers in accessing protective connections with informal supports in their:

- social networks

- community social gatherings

- formal support services (for example, social services, healthcare services)

- MOA perpetrators throughout the pandemic could more easily:

- mistreat older adults

- leverage social distancing protocols to exert a heightened level of power and control over victims

- obstruct attempts by informal supporters or formal service providers to detect and support victims

- the availability of frontline MOA response programs was severely lacking in communities across Canada. This left many older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA without appropriate forms of formal support. Considerable attention is needed around the development of community-based MOA response systems across Canada, including:

- coordinated referral pathways

- specialized response programs

- identification and scaling of evidence-based practices

- social distancing requirements and restrictions to in-person services made it challenging to connect with, identify and detect, or respond to and support older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA during the pandemic. Our current understanding of service delivery through remote or virtual forms of interaction (for example, video-conferencing, telephone, email, chat) was not a fully adequate replacement for in-person interactions in terms of effectively identifying and detecting or providing responsive support for older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA

- dependence on remote or virtual mediums of interaction for social connection or to receive formal service delivery represented an inequitable new standard for many older adults who:

- lacked access to the necessary technology or internet connectivity

- lacked sufficient digital literacy to navigate technology

- were living with physical (for example, vision, hearing), functional or cognitive challenges that impeded their capacity to use such technology

Internet and technology access barriers were exacerbated for older adults from communities who experienced disadvantage on the basis of their social-cultural identity, socio-economic status, or geographic location

- community-based MOA networks experienced challenges maintaining a collaborative and coordinated effort among partner agencies and organizations throughout the pandemic in order to provide supports at the local level

- organizations responsible for the prevention, identification and detection, and response and support of at-risk older adults experienced workforce instability, shortages in personnel, and resource constraints. These factors impeded their capacity to effectively implement MOA prevention and response objectives

- knowledge of and mechanisms to disseminate and share best practices about MOA prevention and response during the pandemic were underdeveloped. This inhibited organizational capacity to pivot and effectively adapt service delivery

Based on the findings synthesized across the comprehensive literature review and stakeholder survey, a set of recommended future directions are provided. These future direction recommendations represent key opportunities and actionable steps to address the identified gaps and challenges in preventing and responding to MOA that were exposed during the pandemic.

Introduction

The mistreatment of older adults (MOA) is recognized by policymakers, researchers, and clinicians as a pervasive issue affecting an aging population with major individual and community consequences. The World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted MOA as a key issue affecting older adults in its World Report on Ageing and Health and as a part of its recent Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021 to 2030) initiative (WHO, 2022). The current report on MOA is guided by the WHO definition:

“a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person”

Consistent with the WHO approach and other authoritative definitions, MOA comprises several subtypes, including:

- financial abuse or exploitation

- emotional or psychological abuse

- physical abuse

- sexual abuse

- neglect by others (Beaulieu and St-Martin, 2022; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016; National Research Council, 2003; Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin, and Lachs, 2016)

However, MOA is defined differently across jurisdictions in Canada and in some cases comprises additional subtypes. For example, across jurisdictions in Canada, MOA also includes:

- mental cruelty

- irresponsible medication practices (overmedication, withholding medication)

- humiliation

- intimidation

- censoring

- invasion of privacy

- denial of access to visitors

- violation of human or civil rights

- self-neglect

- spiritual, religious or cultural forms of abuse (Beaulieu and St-Martin, 2022)

The issue itself is also referred to by different terms. These terms include elder abuse, elder mistreatment, elder maltreatment, and senior abuse. The term used in this report, MOA, includes the word “mistreatment” which accurately captures both abuse and neglect subtypes without confusion. MOA also uses the word “older adult,” which avoids terms associated with discriminatory or negative stereotypes (Gerontological Society of America, 2022) or language that carries culturally specific meaning, for example, in Indigenous communities.

Recent population-based MOA studies in Canada have highlighted the pervasive scope of this issue. Based on large, random samples of older adults across Canada, Burnes and others (2022) and McDonald and others (2018) found one-year MOA prevalence rates ranging between 8.2% and 10% among older adults living in the community. Therefore, each year, approximately 1 out of every 10 community-dwelling older adults experience some form of MOA. These prevalence rates likely under-estimate true population prevalence since studies have excluded particularly vulnerable sub-groups of older adults living with cognitive impairment or in institutional settings. Barring the development of effective prevention strategies, the absolute number of MOA cases is expected to increase substantially over the next 2 decades in proportion with projected older adult population growth. MOA victimization is associated with serious physical, mental, financial and social consequences such as premature mortality, poor physical and mental health, diminished quality of life, and increased rates of emergency services use, hospitalization, and nursing home placement (Beaulieu and others, 2021a; Yunus and others, 2019).

Natural disasters and times of crisis have a profound impact on family violence and the efforts designed to prevent these dynamic interpersonal issues (Parkinson and Zara, 2013). Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic was a global eye-opener on the issue of MOA (Mikton and others, 2022). The pandemic magnified a set of conditions among older adults, including:

- heightened levels of social isolation

- poor health

- loneliness

- depression

- dependency on others

which represent known MOA risk factors (Burnes and others, 2022; Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin, and Lachs, 2016). Different measures taken to limit the spreading of the virus, such as lockdown and restriction in visitors, were associated with MOA from a violation of rights’ perspective (Rebourg and Renard, 2022, Vignon-Barrault, 2022). Under pandemic circumstances, some mistreated older adults were confined to the home with their perpetrator. These perpetrators could leverage stay-at-home, self-isolation, and social distancing protocols to exert a heightened level of power and control. Within this context of the pandemic, in the USA, evidence suggests that the prevalence of MOA almost doubled (Chang and Levy, 2021) and that the severity of mistreatment experiences increased (Weissberger and others, 2022). Also in the USA, COVID-19 disproportionately affected older adults identifying with marginalized communities in relation to:

- race

- socio-economic status

- level of ability (Abedi and others, 2021)

Therefore, our understanding of associations between MOA and COVID-19 must be viewed through an intersectional lens that is sensitive to the varying experiences of older adults identifying with different sociocultural identities. Overall, the heightened levels of MOA during the pandemic highlighted a need to identify the gaps and challenges that exist in various systems of MOA prevention and intervention response. An understanding of these gaps and challenges will inform future work focused on the development of effective prevention and response strategies.

Objectives

The purpose of this project was to identify gaps and challenges in preventing and responding to MOA in Canada that were exposed or exacerbated during the height of the pandemic. This project undertook the following methodologies to identify these gaps and challenges:

- a comprehensive literature review

- a survey with service providers and stakeholders

Comprehensive literature review

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was conducted as one source of information to identify gaps and challenges in preventing and responding to MOA that were exacerbated or exposed during the pandemic. The literature review drew from multiple sources, including peer-reviewed literature; government reports at federal, provincial, and territorial levels; as well as reports from relevant stakeholder organizations in the MOA sector.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible records for the literature review included:

- peer-reviewed papers from academic journals

- grey literature reports, blog entries, and testimony to standing committees

- government (federal, provincial, territorial) reports and commissions of inquiry

- ombudsman reports

- reports generated from non-profit or non-governmental organizations and networks that were directly involved in MOA policy, advocacy, research, or service

Eligible records also met the following criteria:

- focus on MOA in the context of the pandemic

- focus on one or more of the following MOA subtypes: financial, physical, emotional or psychological, or sexual abuse, or neglect by others

- published from year 2020 onward

- English or French language

- peer-reviewed literature from anywhere in the world

- government or non-profit/governmental reports from Canada; and

- a focus on MOA occurring in either community or institutional settings

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from January 2020 onwards:

- Cairns

- Erudit

- PubMed

- Medline

- PsycINFO

- Social Work Abstracts

- CINAHL

- AgeLine

- greynet.org

- open grey

The search strategies were translated using each database platform’s command language, controlled vocabulary, and appropriate search fields for concepts related to MOA and COVID-19. Relevant government and non-profit/governmental reports were identified through internet searches, consultations with the Project Authority, and feedback from the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Seniors Forum working group or other FPT officials.

Data charting

Reviewers extracted the following study- or report-level data from each eligible record using a common Excel data collection tool:

- source reference

- location

- type of record (peer-reviewed, report, other)

- MOA subtypes

- context (community, institution)

- gap or challenge in addressing or preventing MOA during pandemic

- category of gap or challenge in addressing or preventing MOA

- lessons learned

The following broad categories were used to organize findings related to gaps and challenges that represent key phases in preventing or responding to MOA:

- primary prevention (preventing the initial occurrence of MOA)

- identification and detection (identifying older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA)

- response and support intervention (direct response intervention designed to support older adults experiencing MOA)

Beyond these sequential phases of prevention and response intervention, it was necessary to include a broader systemic or structural category. This would capture gaps and challenges that occur at more centralized systemic or structural levels requiring coordination across jurisdictions, systems, or sectors. Within these broad categories, gaps and challenges identified in the literature were further organized into themes. These themes provided a more specified level of organization to group and understand the findings. For example, a gap or challenge from a record related to difficulties engaging older adult victims of MOA within a response intervention using remote or virtual forms of communication was assigned to the broad category Response and Support Intervention and a theme of Remote or Virtual Forms of Service Support.

Results

Primary prevention: preventing initial occurrence of MOA

Primary prevention refers to preventing MOA before it happens in the first place. Several gaps and challenges related to primary MOA prevention throughout the pandemic were identified in the literature review and organized under the following themes:

- ageism

- informal caregiver burden and availability

- homecare availability

- social isolation

- healthcare service access

- mental health challenges

Ageism

Ageism against older adults was highlighted throughout the pandemic (FPT, 2022; Fraser and others, 2020; Perks, 2021; Sutter and others, 2022). According to the World Health Organization, ageism is defined as:

“stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) toward others or oneself based on age”

Poor quality care and disproportionate rates of COVID-19-related deaths in long-term care settings highlighted a lack of attention and resources in addressing older adult needs. In the community, measures intended as protection resulted in older adults experiencing heightened levels of social exclusion and isolation in their homes without equivalent measures to provide connection (Rouleau, 2022). The proliferation of and reliance on internet-based platforms to facilitate such social connections carried ageist assumptions. It required a certain level of digital literacy and functional and cognitive capacity that some older adults did not have. In turn, it led to difficulties accessing informal and formal social supports. Use of such internet-based technology became an accepted norm throughout the pandemic, without acknowledging a digital divide across age groups or addressing issues of digital literacy and access to technology among older adults.

Ageist discourses related to older adults as burdens to society were magnified during the pandemic along with resentment toward older adults. These included views that older adults should sacrifice themselves for the good of younger people (Barrett and others, 2021; FPT, 2022; Lagacé, and others, 2022). Older adults experienced intimidating looks, as well as derogatory or aggressive comments (Thivierge and Guay, 2020). Healthcare protocols that prioritized younger age groups and served to devalue the health and well-being of older adults emerged as institutionally based ageist practices throughout the pandemic (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2020). There is a need to develop care models and support services based around the needs of older people (Abdi and others, 2019). Since long-term care settings across Canada are underfunded, they were not ready to face the pandemic (Meloche, 2022).

Using an intersectional lens, ageism did not operate in isolation from, but rather interacted with, other socio-cultural processes that contribute to unequal social arrangements. That is, processes related to:

- gender

- race or ethnicity

- socio-economic status

- level of ability

- sexual orientation

- other systems of inequality

An older adult’s intersection with other social identities and systems of inequality influenced the level of ageism experienced and, in turn, the extent to which ageism contributed to MOA (Pillemer and others, 2021).

Overall, ageism throughout the pandemic increased vulnerability to and provided justification for MOA and represents a critical target for primary prevention efforts (CSQ-FSQ, 2020; Pillemer, Burnes, and MacNeil, 2020).

Informal caregiver burden and availability

Older adults living with day-to-day functional impairments or physical health issues requiring daily care and assistance are disproportionately affected by MOA (Burnes and others, 2021b; Burnes and others, 2022b). Therefore, mechanisms to support informal caregivers providing such care to older adults represent an important form of primary MOA prevention.

Informal caregivers (family, friends) providing day-to-day care for older adults experienced elevated levels of stress and burden throughout the pandemic (Liu er al., 2021; Makaroun and others, 2021). Supplemental caregivers (for example, other informal caregivers, formal homecare providers) who would normally be available to help primary caregivers with care responsibilities were less available or unable to access the home (Chin-Tung and others, 2021). This placed a greater load on individual primary caregivers. Informal caregivers did not have access to the same levels of respite support or other forms of support (for example, support groups) to alleviate stress and burden during the pandemic. Some of them were also dealing with competing demands, such as supporting school-aged children doing online learning at home or increased levels of financial hardship (Makaroun and others, 2020). Similarly, community programs for older adult care recipients that would normally provide a break for caregivers were shut down or restricted at various times throughout the pandemic (Poulin and others, 2021). In sum, informal caregivers did not have access to the same resources or sources of support and respite throughout the pandemic which, in turn, resulted in elevated levels of stress and burden, which can translate into a higher propensity to mistreat.

Homecare availability

Related to the challenges experienced by informal caregivers was the availability of formal homecare supports throughout the pandemic. The number of homecare assessments, for example, declined substantially by 44% in April 2020. It remained lowered over subsequent months of reporting (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). The availability of formal homecare to meet the day-to-day needs of older adults living with functional, cognitive, or physical impairments is an important form of primary MOA prevention. Without homecare support, basic care needs are unmet and older adults are put in a vulnerable position to depend on others. Throughout the pandemic, some homecare workers were unable to continue caring for older adults due to illness, agency policy, or social distancing restrictions. Other workers were unwilling to provide care due to fear of contracting or spreading COVID-19, either in traveling to or from the older adult’s home or in providing care. In some scenarios, families chose to cease homecare to reduce potential virus exposure. Reduced homecare also placed greater strain on informal caregivers (as mentioned above), who were already suffering from increased levels of burden and stress (Liu and others, 2021).

Social isolation

Older adults in particular experienced increased levels of social isolation throughout the pandemic. Social isolation represents a strong risk factor for MOA (Burnes and others, 2022a; FPT, 2021; Perks, 2021). With heightened vulnerability to the negative health consequences of COVID-19, older adults were encouraged and socialized throughout the pandemic to remain cautiously homebound, above and beyond the social distancing requirements and widespread stay-at-home mandates affecting the entire population. As a result, older adults were disconnected from informal and formal social support structures in their lives that represented important sources of protection against MOA (Han and Mosqueda, 2021). Interaction with peers and participation in activities outside of the home are important mechanisms to build social capital, which buffers against social isolation and mistreatment. Specifically, many older adults were socially disconnected (or experienced substantially lower levels of connection) from:

- family and friends

- community activities (for example, senior centres, day programs, faith-based gatherings)

- health and social services that were shut down or restricted

Older adults also experienced barriers to leaving the home to access important supplies, such as food and medications (Liu and others, 2021). For reasons detailed throughout this report, some older adults did not use the internet as a substitute to connect with social supports via telecommunication or video-conferencing platforms (Liu and others, 2021).

Certain subgroups of older adults were disproportionately impacted by social isolation, including 2SLGBTQI+-identified older adults. These older adults may have been disconnected from their communities of support or chosen families. In jail settings, the lockdown in cells for 24 hours per day was considered a serious violation of rights and magnified the stress of older inmates. They were not only isolated from other inmates but also from visitors who were suspended from making visits. They were also often denied the possibility of out-of-jail permissions (Aubut and others, 2022). In congregate housing facilities (apartment building for older adults), new forms of resident-to-resident aggression occurred out of the restrictions (Falardeau and others, 2021).

Healthcare service access

Due to a focus on COVID-19 cases and emergency care in the healthcare system throughout the pandemic, access to health services was restricted (Benhow and others, 2021). Further, a reduced availability of informal supports provided by family and friends elevated the strain placed on the formal healthcare system (Beaulieu and others, 2021a). Poor physical health represents a strong MOA risk factor (Burnes and others, 2021b; Burnes and others, 2022a). Older adults experienced restrictions and barriers accessing important health services throughout the pandemic. In some cases, confusion existed as to which services were available. Some older adults were also reluctant to engage with health services, believing that such interactions would increase their risk of contracting COVID-19. These service restrictions and barriers limited older adults from addressing new or worsening health needs and, in turn, elevated their risk of MOA (Benhow and others, 2021). As indicated above, older adults also faced heightened difficulties accessing medications to help manage their health issues.

The Canadian Armed Forces report on long-term care (LTC) settings in Québec and Ontario highlighted several issues during the pandemic. Some facilities were severely understaffed, new employees lacked proper training and orientation, and staff were overworked, exhausted or had poor overall morale (Canadian Armed Forces, 2020a, 2020b). General physicians were also overworked, had a lack of training in psychiatric gerontology, and lacked coordination with other mental health specialists. Psychiatrists were unavailable because of growing demand. In addition, access to psychotherapy was limited because of sanitary restriction measures. With lower access to psychotherapeutic methods, the solution was to compensate with medication therapy. However, medical reassessment and surveillance was limited because of the sanitary restriction measures in effect. Therefore, medication therapy treatments were less safe or personalised (Loussaief, 2022).

The pandemic exacerbated many difficulties already present in LTC settings. The lack of resources and institutional culture of efficiency makes it so employees of LTC facilities can only do the minimum to ensure the safety and survival of residents, to the detriment of their well-being (Lord, Drolet, Vicogliosi, Ruest and Pinard, 2022). To compensate for the staff shortage made worse by the pandemic, provincial governments established an accelerated training program for new workers. However, in some instances, this training omitted adequate training on MOA. This lack of MOA training can lead to MOA, an absence of mistreatment case reporting, and a lack of MOA prevention (Beaulieu, and Cadieux Genesse, 2021).

Mental health challenges

Poor mental health also represents a strong MOA risk factor (Burnes and others, 2022a; Perks, 2021). Poor mental health contributes to lower levels of self-worth or issues of denial, self-blame, and isolation that, in turn, increase susceptibility to MOA and may also serve to reduce a person’s capacity to protect themselves. A higher proportion of older adults reported feelings of sadness, loneliness, and being overwhelmed throughout the pandemic compared to beforehand (Liu and others, 2021; Thivierge and Guay, 2020). Some older adults experienced elevated levels of anxiety around leaving the home to avoid COVID-19 (also contributing to social isolation). A study in France found that social distancing increased the risk of depression and anxiety, and hospitalizations due to suicide attempts (Loussaief, 2022). Mental health challenges among older adults were exacerbated by restricted access to medications and psychotherapy, as indicated above (Liu and others, 2021).

Beyond older adults, mental health risk factors linked to potential perpetrators of MOA were also exacerbated during the pandemic, such as:

- mental health issues

- substance abuse

- stress or burden linked to being a caregiver (Laforest and Tourigny, 2021)

The implemented COVID-19 measures prioritized physical health over mental health. This can lead to the exacerbation of psychological mistreatment of older adults (Beaulieu and Cadieux Genesse, 2021).

Identification and detection: identifying older adults at risk of experiencing MOA

An important initial phase within the process of addressing MOA is to identify or detect older adults who are at-risk of or experiencing MOA. Gaps and challenges related to identifying and detecting MOA throughout the pandemic were organized under the following themes:

- social isolation

- perpetrator control tactics

- surveillance by informal concerned others

- homecare availability

- remote or virtual services

Social isolation

Social distancing and stay-at-home mandates throughout the pandemic removed or substantially reduced contacts with:

- informal concerned other social supports (that is, family members, friends, or neighbours in a victim’s social network who provide them with support)

- formal social service, law enforcement, and healthcare providers

- social, recreational, and religious activities in the community

- other social support structures

This social isolation has resulted in fewer opportunities to detect MOA or for older adults to disclose the problem themselves. Agencies involved in preventing and responding to MOA were concerned about the loss of contact with older adults. They were also concerned about the lack of possibilities for them to be heard in public spaces (Bachelet and Broché. 2022). Social isolation is a central, recurrent theme throughout this report that is closely tied to other themes.

Perpetrator control tactics

MOA identification through older adult self-referral or help-seeking was more challenging throughout the pandemic, especially during periods of stay-at-home, self-isolation or quarantine mandates. It was particularly difficult for older adults who lived with their perpetrator. In these shared living scenarios, older adults could not as easily leave the home or find personal space to make phone calls. A perpetrator could use social distancing and stay-at-home mandates as leverage to further limit social interactions with friends and family. This limited opportunities for third-party detection. Detection was also a challenge during remote or virtual-based healthcare and social service sessions. It was not possible to know whether an older adult was alone or in the presence and under the influence of their perpetrator. Power and control dynamics embedded within the victim-perpetrator relationship were heightened for recently immigrated older adults under the influence of a family member (perpetrator) sponsor. The sponsor could use the threat of deportation and financial dependency over the older adult. Recently immigrated older adults also experience language barriers in accessing formal supports outside of the home (Gill, 2022).

The prevention measures linked to COVID-19 increased the use of technology to obtain services and maintain contacts. Yet, older adults who are less skilled in the safe use of technology had more trouble understanding fraud attempts and financial abuse. These tactics were widespread by perpetrators (Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau and others, 2020).

Surveillance by informal concerned others

Informal concerned other supporters in the older adult’s life (family, friends, neighbours) were less available to visit or make contacts with older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA. This limited the availability of these important third-party informal groups to become suspicious of and detect MOA. Concerned others who would typically check on older adults were reluctant to visit given the risk of exposure to the virus, both for themselves and the older adult. This caused further isolation. Similarly, limits on in-person contact also limited opportunities for informal caregivers (who would normally have eyes on the situation) to detect MOA. Informal places of gathering, such as senior centers and faith-based ceremonies, were closed or restricted throughout the pandemic, resulting in:

- less access to informal concerned others in the community

- increased social isolation

- fewer opportunities for informal surveillance, detection, and reporting

Informal concerned other supports play a critical role in the lives of older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA in both detecting the problem and enabling help-seeking (Burnes and others, 2019).

Homecare availability

As outlined above, the availability of homecare workers throughout the pandemic was limited due to illness, agency policy, and fears of contracting COVID-19 from the perspectives of both workers and families. A reduction of homecare workers decreased the possibility of detecting or witnessing potentially abusive or neglectful behavior.

Remote or virtual services

Social distancing mandates throughout the pandemic elevated the threshold required to justify in-person evaluations from social service, healthcare, and law enforcement professionals. This lowered the likelihood of identifying MOA. In parallel, there was a greater reliance on remote or virtual forms of assessment. However, remote or virtual forms of assessment did not afford practitioners with the same scope of opportunities and information to observe for signs of MOA. Specifically, practitioners could not as easily pick up on or attune to specific psycho-emotional or behavioral responses exhibited by an older adult. They could not observe certain physical indications of MOA over telephone or video-conference platforms. Remote or virtual forms of assessment did not adequately substitute for in-person assessment interactions as they related to detecting MOA.

Response and support intervention: direct response intervention to support older adults experiencing MOA

Another important phase within the process of addressing MOA is responding to and supporting older adults who are experiencing MOA (Burnes, 2017). Gaps and challenges related to responding to and supporting older adults experiencing MOA throughout the pandemic were organized under the following themes:

- availability of supportive response services

- safety planning

- perpetrator control tactics

- remote or virtual forms of service support

- responder safety

- supporting diverse communities

- age-friendly shelters or other alternative living arrangements

- organizational capacity

Availability of supportive response services

As an overarching theme, program interventions designed to respond to and support MOA cases are substantially lacking in general. The pandemic circumstances exacerbated this existing service systems gap. Access to services was limited by:

- social distancing measures

- restrictions to in-person services

- personnel shortages

- shutdowns, in some cases

The pandemic created a particularly vulnerable set of circumstances in which many older adult victims of MOA experienced heightened levels of social isolation without adequate access to responsive support services.

Safety planning

Safety planning is a critical form of crisis intervention to escape or receive help in the face of mistreatment. However, escaping a mistreatment situation was difficult throughout the pandemic for older adults who were cautioned not to leave their home. Finding escape was challenging with restricted access to informal and formal supports due to social distancing measures. Safety planning was particularly difficult for older adults who lived with and were isolated in their home with a perpetrator who had a heightened level of control over their whereabouts. In these scenarios, older adults could not as easily leave the home as a part of their safety plan. They could not contact others outside of the home without personal space to make phone calls.

Perpetrator control tactics

The COVID-19 virus and associated social distancing restrictions provided new opportunities for perpetrators to exercise power and control tactics. Perpetrators could provide misinformation to older adults about how the virus spread to promote unnecessary levels of isolation above and beyond those recommended by authorities. Especially in shared living scenarios, perpetrators could impose or convince older adults to endorse unnecessary social restrictions that prevented others from accessing the home. This could include, for example, informal concerned other supporters, cleaning services or homecare.

In turn, older adults could refuse services and deny access to others who would otherwise provide them with support or serve as third-party monitors holding perpetrators accountable. Deprivation of social interaction and physical contact with support structures made it easier for perpetrators to control, manipulate and mistreat older adult victims. Diverse subgroups of older adults experienced control tactics differently. For example, 2SLGBTQI+-identified older adults may have been housed and isolated with a perpetrator that used outing (for example, “I will tell your children if you don’t…”) or created barriers in accessing necessary healthcare (for example, hormone medication) as mechanisms of control.

Remote or virtual forms of service support

Several challenges were identified in using remote or virtual forms of service support to MOA victims throughout the pandemic. It may not be safe for victims to speak over remote telephone or video-conferencing platforms if they reside with their perpetrator. The perpetrator may be in the same home or room during a virtual meeting. This threatens the older adult’s safety and the integrity of the support provided. The perpetrator may even prevent the older adult from having access to this technology. In addition, some older adults had limited ability to communicate through remote technology due to cognitive or physical (for example, hearing, visual) impairments or did not have the digital literacy or access to the technology necessary to navigate these virtual mediums. Important aspects of the work were undermined through remote forms of service delivery, such as limitations building relationships and trust with clients. These are central components to working with MOA victims and doing work to heal trauma. In some cases, the limitations of remote services were perceived to be potentially harmful. The practitioner was unable to pick up on visual clues or the client’s body language as easily.

Responder safety

MOA responders are accustomed to certain worker safety concerns such as:

- unfriendly or hostile perpetrators and witnesses

- aggressive animals

- infectious pests

- dangerous household hazards

However, the pandemic highlighted additional safety concerns to the workforce. Practitioners had concerns about being infected by COVID-19, infecting clients, or infecting other staff members and family members as a result of in-person interactions. With a reduced availability of informal concerned other supporters in the lives of victims, MOA responders had a particularly critical role in meeting the needs of vulnerable older adults. The unpredictable access to and supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as high-quality masks, hazmat suits and gloves, compounded COVID-19-related safety concerns and impeded responders from engaging in in-person sessions. In some cases, clients did not have proper PPE themselves. Responders needed to have a sufficient supply for their clients as well. Finally, many MOA responders lacked sufficient training and knowledge around combatting infectious diseases.

Supporting diverse communities

Older adult immigrants or those from linguistic minority communities may find information about COVID-19 and MOA inaccessible due to language barriers. Immigrant and refugee older adults can be reluctant to access formal support services or receive information about COVID-19 from government-sanctioned entities. They may have had negative experiences with law and government in their home country. Culturally sensitive services and first-language supports are important to ensure that services offered are inclusive, received positively, and that clients fully understand the information shared and can communicate their needs. The way older adults experience the convergence of COVID-19 and MOA varies according to their intersection with different socio-cultural identities. This impacts how they are willing to engage with support services. The potential for bias within the system throughout the pandemic in using health status as a mechanism to discriminate against older adults from marginalized communities must also be recognized and guarded against.

Informal supporters and concerned others

Some victims of MOA access support from informal concerned others in their social network (for example, friends, family, neighbours), rather than working with formal services (Burnes and others, 2019). These concerned others were less available throughout the pandemic to make home visits or support older adults. Older adults also experienced restrictions in their ability to reach out to these informal concerned other supporters.

Age-friendly shelters or other alternative living arrangements

There are very few age-friendly shelters geared toward the needs of MOA victims. Out of a total 500 emergency and transitional shelters in Canada, only 13 (2.5%, in 5 provinces) are focused on older adults. Among the 13 shelters for older adults, only 8 shelters offer full or partial accessibility for people living with functional impairments (CNPEA, 2022). Older adults may need to access alternative shelter models due to age-associated vulnerabilities. Alternative living settings often lack the capacity to support age-associated vulnerabilities, including physical, health and cognitive needs. They also often contain infrastructure that favors younger ages (for example, stairs, cots that are difficult to enter/exit) and program policies that are unrealistic for older adults (for example, requiring residents to leave the shelter all day) (MacNeil and Burnes, 2022). Without suitable age-friendly shelter options or open doors within their social network throughout the pandemic (due to social distancing restrictions), it was challenging to leave abusive scenarios at home.

Organizational capacity

Programs serving MOA victims and their families experienced several challenges at an organizational level. These challenges were related to service capacity throughout the pandemic. MOA responders and program staff who became ill or presented with COVID-19-related symptoms were encouraged to stay home or not work to prevent transmitting the infection to others. There was also a loss of employees due to voluntary layoff. These circumstances contributed to instability (for example, staff turnover, inconsistent schedules) or shortages in personnel (Protecteur du citoyen, 2022). In turn, some programs lacked organization personnel capacity to effectively respond to and support older adults experiencing MOA.

Personnel also experienced strain and mental health challenges as they transitioned to virtual modes of delivery (Montesanti and others, 2022). Many practitioners experienced the mental exertion known as “Zoom fatigue.” This caused them to feel more drained after multiple online sessions. For some providers, it took time to adjust to using virtual video-conferencing platforms. Shifting to virtual delivery considerably altered the way they provided services to clients. Many workers also had to navigate the challenges of technology as a part of their daily services. They had little idea as to how to troubleshoot or fix tech-related problems.

From a resource perspective, the shift to remote work was a serious challenge for many organizations responding to MOA. Throughout the pandemic, organizations incurred additional expenses associated with the adoption of online service delivery, such as:

- purchasing online platforms and equipment to support employees to work from home and conduct remote services

- updating existing technological infrastructure to serve online clients at a larger volume

- strengthening secure servers

- training service providers and clients on how to use virtual platforms

- accommodating clients who had difficulty accessing technology (Montesanti and others, 2022)

The shift to remote work required a substantial amount of information technology (IT) support to negotiate the issuance and maintenance of tablets, smart phones, and computers.

For many years, the Association québécoise des retraité(e)s des secteurs public et parapublic has claimed more investment in homecare to better prevent MOA at home (knowing that the majority of older adults live at home). This plea was renewed during the pandemic (AQRP, 2021). LTC settings also experienced capacity issues with an influx of older adults in facilities. This was the result of a lack of homecare services to meet their needs in the community (Meloche, 2022).

Centralized systemic support: issues requiring coordination across jurisdictions, systems, or sectors

Beyond the various phases of MOA prevention and intervention, it is also important to understand gaps and challenges that exist at centralized systemic or structural levels that involve coordination across jurisdictions, systems, or sectors. Gaps and challenges in this category were organized under the following themes:

- changing COVID-19 guidelines

- internet access

- systems capacity

- organizational resources and sustainability

- sharing lessons learned

Changing COVID-19 guidelines

Although changes in social distancing guidelines throughout the pandemic were an inevitable and reasonable reality in response to a virus with various strains affecting different numbers of people over time, these guideline changes presented a challenge to organizations involved in MOA prevention and intervention. As guidelines changed, many organizational leaders found themselves building and rebuilding protocols to optimally and safely serve older adults. They did so while preventing exposure to workers. When COVID-19-related guidelines or mandates were introduced or modified throughout the pandemic, the implications of how this changing information affected organizational protocols and operations were not always clear. Program response interventions, for example, needed to clearly understand how changes in COVID-19-related restrictions impacted the way services were delivered. Without this clarity, organizations scrambled to figure out how to deliver services and conduct operations most effectively.

Internet access

Access to the internet became a fundamental need throughout the pandemic (CSQ-FSQ, 2020). As described throughout this report, remote communication was necessary for older adults to maintain social contact with informal supports. It was also necessary to engage with formal healthcare and MOA social services. These connections were critical to both the prevention and response and support for MOA. Internet access was also critical to conduct certain instrumental activities of daily living. These activities included banking and shopping for food or other supplies. Despite the importance of accessing reliable internet throughout the pandemic, some older adults faced access barriers. These included the cost of purchasing computer equipment and adequate internet data plans or having adequate digital literacy around navigating technology and the internet. Access barriers were exacerbated for older adults from marginalized communities who experienced disadvantage on the basis of their social-cultural identity, socio-economic status, or geographic location. Certain rural, remote or Indigenous communities lacked the tele-communications infrastructure to access reliable internet.

Systems capacity

“Many preventable deaths occurred in nursing homes under COVID-19. Some deaths were from lack of timely care, water, food or basic hygiene, not from COVID-19 infection. This underscores the frail and highly vulnerable condition of older adults in nursing homes. It epitomizes our failure. Many are not mobile or cannot vocalize their needs. This was more than a communicable disease crisis.”

Leaders adopted a “hospital-centric” model to manage the pandemic (Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau and others, 2020; Protecteur du citoyen, 2022; CSBE, 2022b). There was an offloading of beds from hospitals to LTC settings. LTC facilities were not all prepared with additional measures or means to adequately face outbreaks that happened after these changes. Thus, many older adults were infected. The management of these outbreaks was affected by many elements. LTC facilities have a dual purpose that is misunderstood by authorities. They are both a place to live and a place to receive complex care. This misunderstanding has maintained LTC facilities low on the priority list for preparation of a crisis since they are not hospitals (Protecteur du citoyen, 2022; CSBE, 2022b).

The absence of an onsite manager in many living environments led to the disorganization of services. It also rendered impossible the implementation of many sanitary guidelines and changing directives. Risk management was carried out by leadership without the necessary expertise to do it well. A lack of consultation and coordination prevented the implementation of directives in a timely manner. Moreover, infection prevention and control practices and knowledge were not implemented in LTC settings. Outdated information technology also meant LTC facilities lacked information that affected the management of the pandemic. The authorities could not count on updated data to support their daily decision making (Protecteur du citoyen, 2022; CSBE, 2022b). All of these factors created a lack of fluidity in the implementation of guidelines and important negative impacts on the organization of services. In some cases, this contributed to cases of resident neglect. With the outbreak of the virus, many older adults died (Protecteur du citoyen, 2022).

The healthcare system was overwhelmed during the pandemic in response to high numbers of COVID-19 cases. However, interaction with the health system represents a key opportunity to identify and detect older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA. With restricted capacity and access to healthcare encounters in the community and hospital settings, these opportunities were missed. Older adult victims were more likely to remain hidden. The constrained hospital capacity during the pandemic meant that at-risk older adults who interacted with hospitals without a threshold medical need for admission were sometimes sent back home to a potentially unsafe environment. This was because the capacity for hospitals to admit and manage these complex social situations was reduced.

Organizational resources and sustainability

Availability of emergency COVID-19 funding was necessary to support the rapid adoption and implementation of virtual services and interventions among community-based organizations involved in family violence prevention (Montesanti and others, 2022). Some organizations had no funding to support the transition to virtual delivery. Before organizations could apply for emergency COVID-19 funding, many organizations had already incurred costs. This was due to the rapid and urgent need to adapt services and programs to virtual or remote-based delivery. Compounding this financial situation, the re-direction of resources and effort toward pivoting online at the onset of the pandemic meant that usual fundraising activities were put on hold. The unanticipated costs related to transitioning online and a reduction of fundraising revenue resulted in an unstable financial position for some organizations that affected the ability to operate at full capacity toward the prevention and response to MOA.

Sharing lessons learned

As the pandemic unfolded over time, service providers had to pivot and adapt their approaches in accordance with restrictions. Service providers involved in MOA prevention and intervention adapted to social distancing restrictions and the needs of older adults in different ways throughout the pandemic. Further coordination was required to capture and share emerging adaptive practices and lessons learned among service providers across Canada (FPT, 2021). Relatedly, mechanisms and pathways to exchange this knowledge among MOA stakeholders were required to strengthen the system of MOA response.

Survey with service providers and stakeholders

Methods

A survey with MOA service providers and stakeholders was conducted as a second source of information to identify gaps and challenges in addressing and preventing MOA during the pandemic. The survey provided an opportunity to contextualize and understand gaps and challenges within the Canadian context specifically and to expand upon the gaps and challenges identified in the literature review. The survey followed a mixed-methods data collection approach that included both quantitative Likert scale fixed-response questions, as well as open-ended qualitative text questions. The open-ended, qualitative questions were designed to elicit more in-depth, unanticipated insights around gaps and challenges in MOA prevention throughout the pandemic. Specifically, they were designed to elicit information from stakeholders about lessons learned and promising practices in adapting to the pandemic. Questions in the survey were informed by the themes identified in the comprehensive literature review, as well as input from the project authority and FPT working group members. The survey was administered in both English and French. The overall purpose of the survey was to identify gaps, challenges and lessons learned in preventing or addressing MOA across jurisdictions in Canada exposed or exacerbated during the pandemic.

The survey was organized around the following 4 sections that parallel the organizational framework of the comprehensive literature review and that reflect the major phases involved in preventing or responding to MOA:

- primary prevention (preventing the initial occurrence of MOA)

- identification and detection (identifying older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA)

- response and support intervention (direct response intervention designed to support older adults experiencing MOA)

- centralized systemic or structural supports

The full survey can be found in Appendix B.

Participant recruitment

The survey was intended for MOA stakeholders with direct knowledge or involvement in MOA prevention or response intervention efforts, including:

- individuals from non-profit MOA organizations, networks, and associations

- healthcare and social service programs

- governments at federal, provincial and territorial levels

An initial list of prospective survey respondents was generated based on the following sources:

- input from members of the FPT working group who represent each of the provinces and territories across Canada

- input from the project leads who are involved with several MOA networks in Canada

- extensive internet searching to find new MOA stakeholders in each province and territory across Canada

The final list of prospective survey respondents included 240 MOA stakeholders with representation from each province and territory across Canada. To broaden the reach of the survey, established MOA organizations in Canada with extensive networks of MOA stakeholders (for example, Canadian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario) were invited to distribute the survey throughout their networks. Finally, using a snowball sampling approach, individual stakeholders on the list were invited to share the survey with relevant individuals in the field. In the end, a comprehensive and robust outreach strategy was used to reach as many stakeholders as possible with representation across each province and territory.

Data collection

The survey was administered through computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) using a secure online platform, Qualtrics. Survey respondents followed a single, anonymous link. They were assigned a random ID number that could not be traced back to their identity. A computerized survey approach offered several advantages to respondents, such as:

- a reduction in survey burden (for example, using automatic branching and skip rules)

- a heightened sense of autonomy and confidentiality

- convenience/flexibility around when to complete the survey

The CASI approach also facilitated instantaneous data collection/entry.

Prospective respondents on the stakeholder list were sent 4 different email reminders to fill out the survey. Additionally, over time, it was identified that certain provinces or territories did not have survey response representation. Therefore, 3 separate emails were sent to each of the groups of stakeholders living in these jurisdictions as a more targeted and personalized attempt to bolster their representation. Despite these relatively aggressive, targeted efforts to ensure representation across every province and territory, certain jurisdictions were unresponsive compared to others.

Sample

Our initial proposed goal was 150 survey respondents. Based on the outreach efforts described above, 489 individuals started to fill out the survey. Of these, 240 people did not go beyond the initial section on basic socio-demographic information into the main sections of the survey on gaps/challenges in preventing or responding to MOA. For the purpose of analysis, we have excluded these 240 individuals who did not provide responses around gaps and challenges. Therefore, the analytic sample for the current project is n = 249. The sample size varies across different questions, since respondents were not required to answer every item and reserved the right to skip questions. Given the budget for this project and, consequently, the non-random sampling strategies employed, the analytic sample is not representative of the Canadian population.

Analysis

Analysis of the open-ended, qualitative text responses followed an iterative, constant comparison process allowing the emergence and reorganizing of gaps/challenges themes as new information across surveys arose (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Analyses combine responses from the English and French administrations of the survey. For the purpose of this report, a “majority” was defined as more than 50% of respondents agreeing or disagreeing with a given survey item statement. A strong majority was defined as more than 2 thirds (66%) of respondents agreeing or disagreeing with a given survey item statement. With 5 item response options in the survey Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree), a “disproportionate” number of respondents agreeing (agree, strongly agree) or disagreeing (disagree, strongly disagree) was defined as more than 40% of responses in either the agreement or disagreement options. Given the variation across survey items in missing responses, survey findings reported on gaps and challenges are based on the valid percentages of item responses.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample (n = 249) included both English (n = 236) and French (n = 13) administrations of the survey. Our inability to solicit survey responses from the province of Quebec contributed to the underrepresentation of French-speaking surveys. Table 1 presents characteristics of the sample. A majority of respondents identified as female (67.5%), followed by male (29.3%), non-binary (1.6%), and two-spirit (0.4%). Some respondents identified as First Nations, Inuk (Inuit), Métis citizen, or other Indigenous identity (7.7%), and 7.6% of respondents identified as a member of an ethno-cultural or visible minority group. Most respondents were between the ages of 40 and 74 (79.1%). A majority of respondents were from Ontario (62.2%) followed by:

- Alberta (9.2%)

- Manitoba (7.6%)

- Northwest Territories (4.8%)

- British Columbia (3.6%) and Nova Scotia (3.6%)

- Québec (2.4%)

- New Brunswick (2.0%)

- Newfoundland and Labrador (1.2%)

- Saskatchewan (0.8%)

- Prince Edward Island (0.8%)

- Nunavut (0.4%)

- Yukon (0.0%)

Respondents worked in urban (45%), rural (34.9%), and suburban (19.3%) geo-cultural contexts. They worked in a range of employment sectors, including social services (23.3%), healthcare (22.5%), government (11.2%), non-profit (6.8%), education (6.0%), business (4.8%), law enforcement (2.0%), and other (13.7%), as well being retired (8.8%). As it relates to the issue of MOA, respondents described their main role/responsibility as practitioner/provider (43.8%), advocacy (37.3%), policy (6.0%), research (4.4%), and other (24.9%). A majority of respondents identified their main role as involving direct service provision with older adults (57.4%).

Primary prevention

Quantitative survey responses

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of survey responses on items related to the topic of primary MOA prevention. Key survey findings related to primary prevention are summarized as follows:

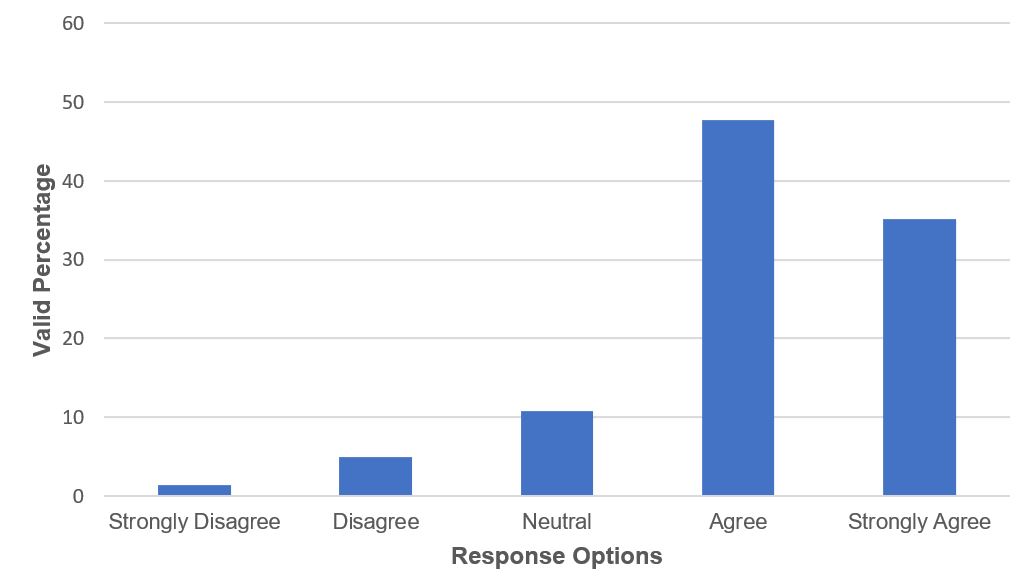

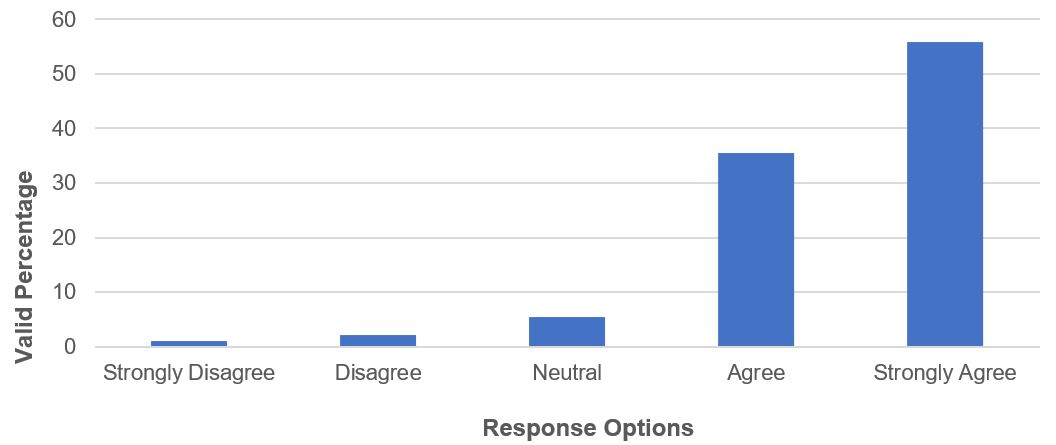

- overall, based on a catch-all question related to primary MOA prevention, over 80% of respondents agreed that it was challenging to prevent at-risk older adults from experiencing MOA during the pandemic (Figure 1)

Figure 1 – Text version

Figure 1 shows a bar graph with response options on the x axis and valid percentage on the y axis. The graph indicates that in response to the statement “Overall, it has been challenging to prevent at-risk older adults from experiencing MOA through the pandemic”, 1.4% of respondents strongly disagreed, 5% of respondents disagreed, 10.8% of respondents had a neutral response, 47.7% of respondents agreed and 35.1% of respondents strongly agreed.

- A majority of respondents perceived that further MOA awareness-raising efforts were required during the pandemic that targeted both the general public and professionals who work with older adults. A majority of respondents also perceived that awareness-raising initiatives for the general public require a more tailored strategy to account for the needs and experiences of older adults from diverse communities. Respondents also disproportionately believed that an inadequate amount of training was available during the pandemic for professionals who work with older adults on how to recognize MOA

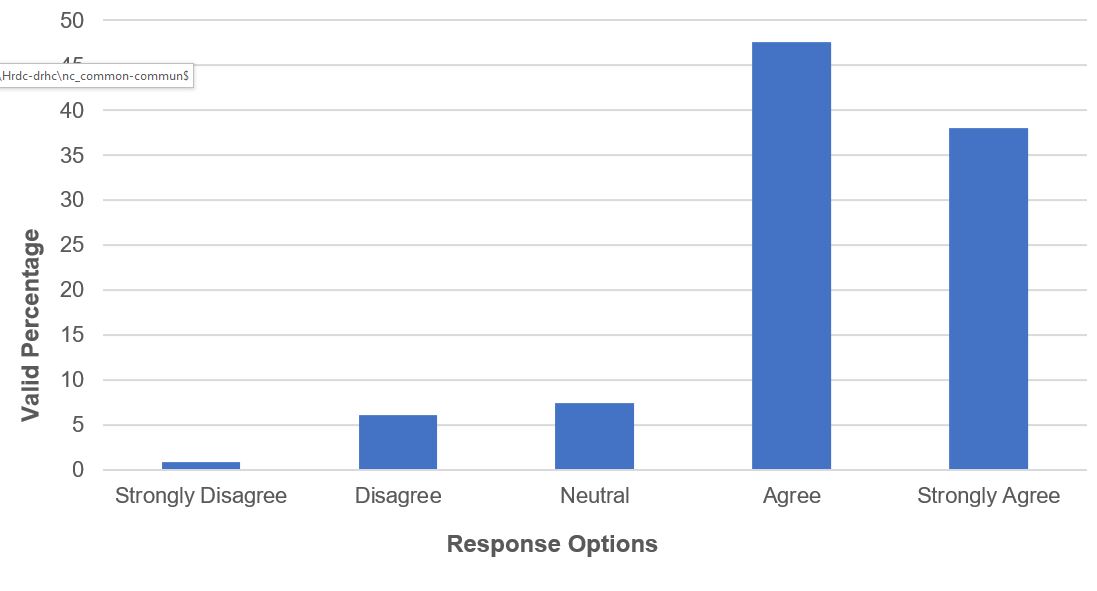

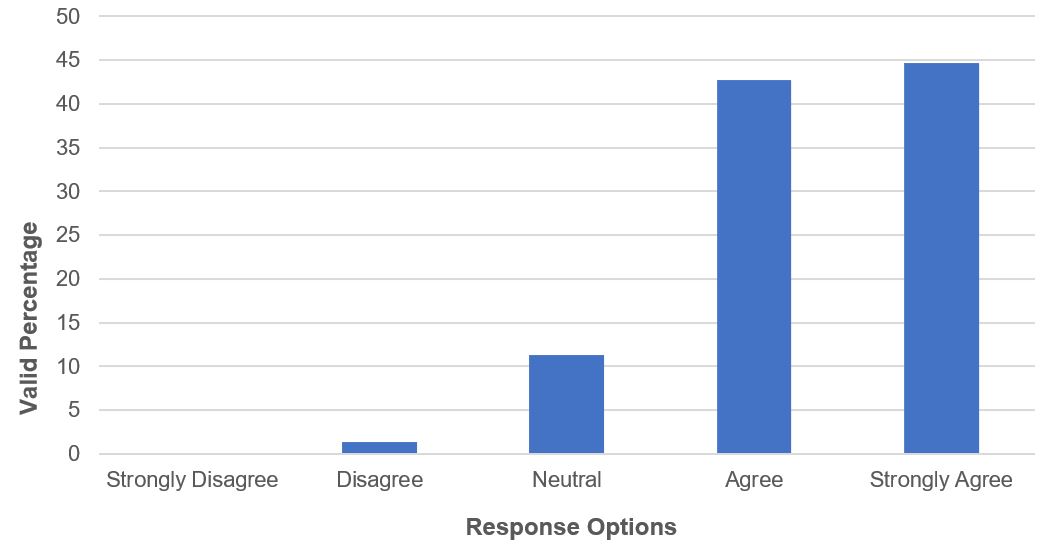

- Over 85% of respondents agreed that both formal service providers (Figure 2) and informal family and friends had difficulty connecting with older adults during the pandemic. A strong majority of respondents agreed that older adults themselves had difficulty engaging with social activities in their communities, accessing supplies within their communities and that older adults with physical, cognitive, or functional limitations had difficulty accessing at-home informal or formal care supports

Figure 2 – Text version

Figure 2 shows a bar graph with response options on the x axis and valid percentage on the y axis. The graph indicates that in response to the statement “Service workers (healthcare, social service) have had difficulty reaching out to or connecting with at-risk older adults throughout the pandemic, including periods of stay-at-home or self-isolation mandates”, 0.9% of respondents strongly disagreed, 6.1% of respondents disagreed, 7.4% of respondents had a neutral response, 47.6% of respondents agreed and 38% of respondents strongly agreed.

- A majority of respondents disagreed that virtual or remote forms of interpersonal or digital communication were feasible or suitable ways of connecting with older adults throughout the pandemic. These forms of communication include:

- video-conferencing

- telephone

- chat

- instant messaging

- Over 90% of respondents agreed that informal caregivers experienced heightened levels of stress or burnout throughout the pandemic

- A strong majority of respondents agreed that ageism toward older adults was elevated throughout the pandemic and increased vulnerability to MOA

Qualitative survey responses

Stakeholder responses to the open-ended, qualitative survey questions reinforced many of the results found from the closed survey questions. When asked about what they perceived as being the top challenges or gaps related to MOA prevention throughout the pandemic, the most common response was the heightened levels of social isolation and loneliness experienced by vulnerable older adults. Stakeholders expressed that restrictions to in-person home visits by health and social service programs represented a major challenge in their capacity to assess older adults or conduct check-ins. Further, they described that virtual or telephone-based services as a replacement of in-person appointments was inappropriate and carried heightened MOA risks. They indicated that many older adults struggled with basic technology skills or had age-associated impairments (vision, hearing, movement) that precluded their use of such virtual service delivery. Stakeholders described the disproportionate impact of restricted or cancelled service access on low-income older adults who relied on subsidized or volunteer programs to access basic needs such as food, cleaning, transportation, and library internet access. Several stakeholders mentioned that the absence of transportation services denied older adults access to appointments or obtaining basic resources.

Stakeholders indicated that informal caregivers experienced heightened levels of stress or burden throughout the pandemic. This resulted from the closure of respite services and the limited opportunities for older adult care recipients to attend senior day programming or other community activities. Relatedly, many stakeholders described the elevated MOA risks associated with the shortage and limited access to personal homecare services. They believed that older adults experienced worsened physical and mental health conditions as a result of insufficient home care, limited access to healthcare and depleted social stimulation, which elevated MOA risk. Restricted access to community-based social services, homecare, healthcare, and social and spiritual activities affected opportunities for contact with others which, in turn, elevated MOA risk. Stay-at-home mandates forced people to live and stay at home alone together for extended periods of time under stressful conditions. This increased opportunities and risk of MOA.

Respondents were also asked an open-ended question about lessons learned or perceived best practices in approaching MOA prevention throughout the pandemic. Most commonly, stakeholders indicated the need to maintain some degree of in-person services throughout the pandemic dedicated to older adults. Respondents understood that precautions needed to be taken, such as the use of PPE. However, in-person wellness checks were required to put eyes on the situation and understand a person’s needs. Respondents indicated that regular check-ins were helpful. Respondents described the importance of strengthening efforts in the community that take responsibility for older adult welfare. Such efforts include strengthening existing MOA networks in the community and the communication between agencies that serve older adults. Several stakeholders remarked that further MOA awareness and education efforts were required to prevent the problem. One respondent suggested a large-scale, free online module describing MOA to raise awareness.

Given the emphasis on internet-based technology throughout the pandemic, respondents suggested the need for programs that teach older adults about using this type of technology. Other suggestions or lessons learned included:

- keeping libraries open

- making transportation available (particularly in rural areas)

- offering grocery delivery services without an extra cost burden

- respite services for caregivers

- more robust financial monitoring systems to identify abusive, irregular patterns of transaction

- using local community-based newspapers to communicate about MOA with older adults who live in rural areas

One respondent described a program involving additional outreach workers in the community to assist low-income older adults with basic needs (for example, transportation, reminders about appointments, dropping off food). Several stakeholders described how volunteer friendly visiting programs would help maintain connections with older adults who would otherwise be isolated. Another respondent from a retirement home described how they created small bubbles within their larger home community. They also created hallway activities and fitness classes to get people out of their suites and moving around. Finally, respondents recognized the need for further research to understand effective MOA prevention strategies.

MOA identification and detection

Quantitative survey responses

Table 3 provides a breakdown of survey responses on items related to the gaps and challenges in identifying and detecting older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA. A summary of key findings are as follows:

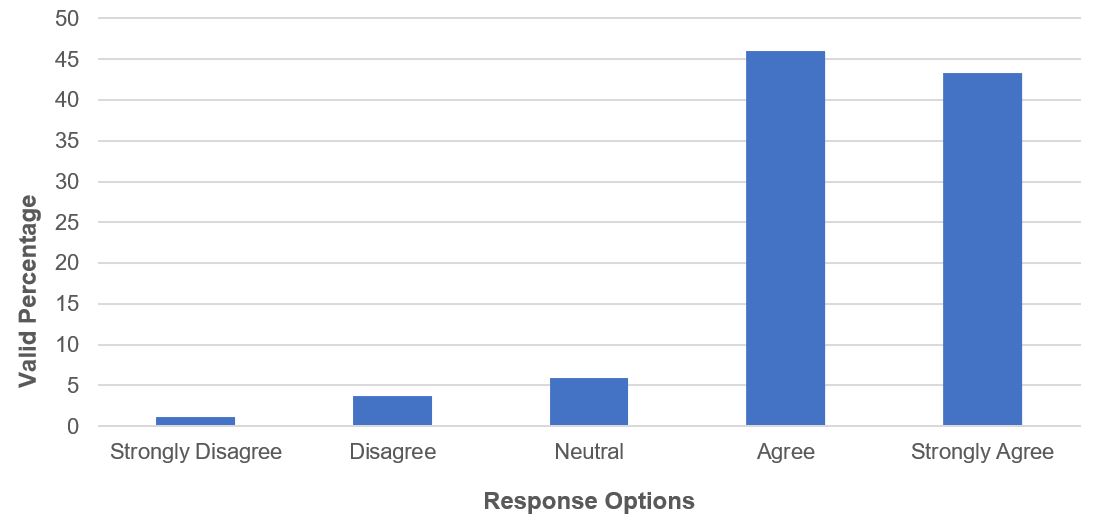

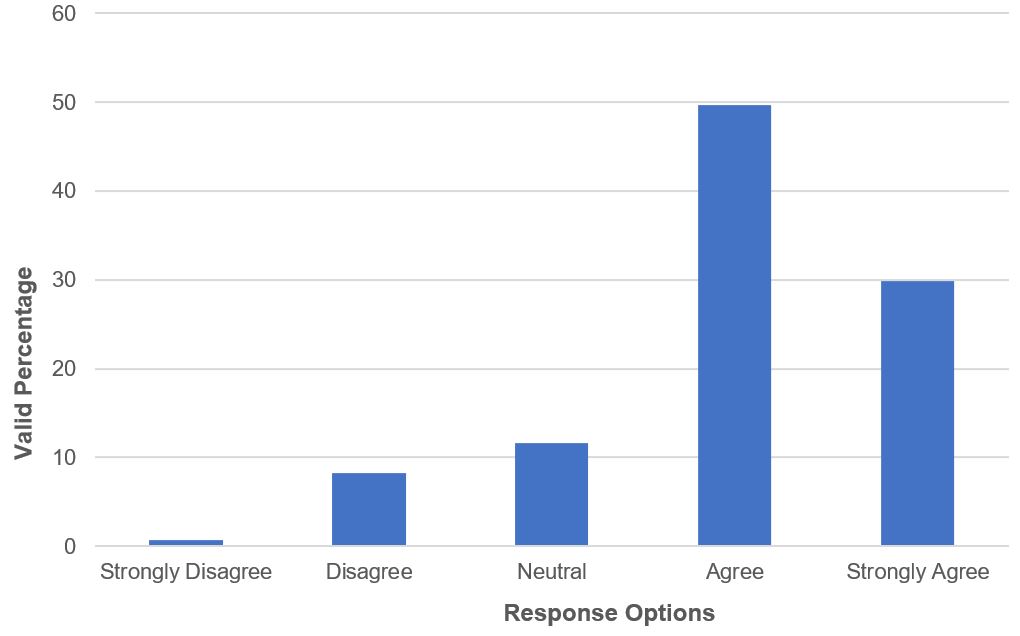

- overall, based on a catch-all question related to MOA identification and detection, nearly 90% of respondents agreed that the process of identifying and detecting older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA was challenging throughout the pandemic (Figure 3)

Figure 3 – Text version

Figure 3 shows a bar graph with response options on the x axis and valid percentage on the y axis. The graph indicates that in response to the statement “Overall, the process of identifying and detecting older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA throughout the pandemic has been a challenge,” 1.1% of respondents strongly disagreed, 3.7% of respondents disagreed, 5.9% of respondents had a neutral response, 46% of respondents agreed and 43.3% of respondents strongly agreed.

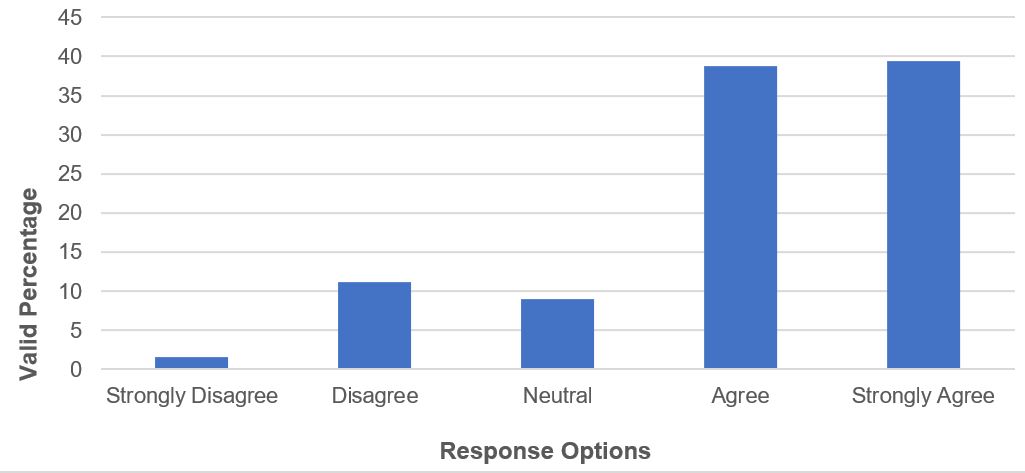

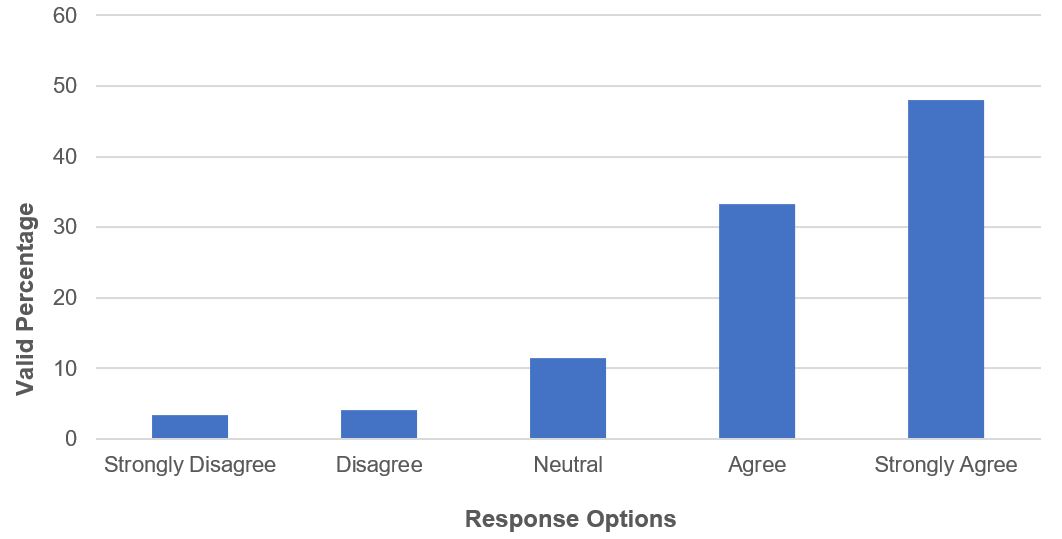

- Approximately 80% of respondents agreed that social distancing requirements and restrictions to in-person services during the pandemic created challenges in identifying and detecting older adults at risk of or experiencing MOA. Relatedly, a strong majority of respondents agreed that service delivery using remote or virtual forms of live interpersonal communication (Figure 4) or digital forms of written communication made it challenging to identify and detect vulnerable older adults

Figure 4 – Text version