Social isolation of seniors: A Focus on Indigenous Seniors in Canada

Official title: Social isolation of seniors—Supplement to the social isolation and social innovation toolkit: A Focus on Indigenous Seniors in Canada

On this page

- Participating governments

- Acknowledgements

- Background

- Introduction

- Part 1: Social isolation of Indigenous seniors

- Diversity of the Indigenous community

- Language and culture

- Social determinants of health and health inequities

- Demographic profile: A growing population

- Increasingly urban

- Preventing social isolation: protective factors

- Awareness of traditional cultural values, languages and kinship systems

- Social isolation risk factors

- Case studies

- Creating opportunities for Indigenous seniors to engage

- Consequences of social isolation for Indigenous seniors

- Community-level success stories

- Core principles of Indigenous social innovation

- Practical strategies to engage Indigenous seniors

- Part 2: Tools and examples of ideas exchange events for Indigenous seniors

- Appendix A: Event planning checklist

- Appendix B: Sample invitation

- Appendix C: Presentation slides

- Appendix D: Case study

- Appendix E: Handouts: Additional considerations for Indigenous seniors

- Appendix F: Protocol for Indigenous elders

- Appendix G: Indigenous peoples of Canada: Demographic profile

- Appendix H: Additional resources for organizers and facilitators

Alternate formats

Social Isolation of Seniors - A Focus on Indigenous Seniors in Canada [PDF - 1.2 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Participating governments

- Government of Alberta

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Canada

Acknowledgements

The Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) Working Group on Social Isolation and Social Innovation would like to thank Dr. Bonita Beatty for leading the development of this product. The views expressed in this product may not reflect the official position of any particular jurisdiction.

The Forum is an intergovernmental body established to share information, discuss new and emerging issues related to seniors, and work collaboratively on key projects.

Québec contributes to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Québec.

Background

This supplement is a resource to help organizations and service providers adopt approaches to help Indigenous seniors strengthen human connections. Social isolation is a silent reality experienced by many seniors, and particularly Indigenous seniors. It is hoped that this resource will heighten awareness and sensitivity and help organizations address their particular social needs.

This supplement should be read in conjunction with two Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Ministers Responsible for Seniors documents. Social Isolation of Seniors: Volume I – Understanding the issue and finding solutions provides an overview of social isolation among seniors in Canada while Social Isolation: Volume II— Ideas exchange event toolkit provides hands-on resources for groups.

The materials included in this supplement are drawn from current research, consultations (including a workshop) with Indigenous partners and other stakeholders, an environmental scan of existing programs and services, and experiences of Indigenous seniors themselves. This supplement consists of two parts: Part 1 explores social isolation from the perspective of Indigenous seniors and Part 2 provides practical tools and resources to encourage human connections to reduce social isolation.

This resource is meant as a starting point to initiate discussions among partners, stakeholder groups and Indigenous seniors and organizations to develop and implement innovative local programs and find ways to increase human connections and reduce social isolation. Action is needed at all levels of planning and decision-making to promote and provide information on strategies to address social isolation. There are a multitude of possibilities for collaborative action to encourage social inclusion of Indigenous seniors.

The contributions from the many service providers working with Indigenous seniors were invaluable in creating this resource. Permission is granted to reproduce with appropriate credits and citation.

Introduction

What is social isolation?

Social isolation is a situation in which someone has infrequent and/or poor-quality contact with other people. A person who is socially isolated typically has few social contacts or social roles, and few or no mutually rewarding relationships. (For information about how seniors can become socially isolated, see Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume I: Understanding the issue and finding solutions.)

Although social isolation is often associated with loneliness, the two are not the same. Loneliness is better described as “a feeling of distress that results from discrepancies between ideal and perceived social relationships.”Footnote 1 That is, loneliness happens when your social relationships do not live up to your expectations, so it can be experienced even when a person has adequate social networks. This document focuses on social isolation, not loneliness. Reaching out to Indigenous seniors who are at risk of being socially isolated may reduce their risk of poor health and poor quality of life.Footnote 2

Using the ideas in this supplement

Before putting into practice the ideas set out in this report, it is important to have a sound understanding of the Indigenous seniors' local and regional contexts. This knowledge is needed to adapt the content of events, determine appropriate venues and provide open and inclusive spaces for dialogue.

Diverse groups of service providers, beyond those only in the medical and social services sectors, are encouraged to take part in such events. Reaching out to all occupational groups can have more far-reaching and significant impact than what might be achieved by only specialists and service providers. The companion document, Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit, provides guidance on hosting effective meetings to exchange ideas to address the social isolation of seniors. This document provides additional information and ideas for events focused on Indigenous seniors.

Social isolation among Indigenous seniors

Indigenous seniors are considered at high risk of experiencing social isolation due to factors such as racism, marginalized language, culture, poverty and historic negative experiences.

Removed from their families and home communities, seven generations of Aboriginal children were denied their identity through a systematic and concerted effort to extinguish their culture, language, and spirit.Footnote 3

The trauma experienced as a result of the residential school experience has built upon trauma from earlier forms of injustice and oppression and continues to be built upon by contemporary forms such that the trauma is cumulative with oppression and abuse becoming internalized leading to a sense of shame and hopelessness that is transmitted and built upon through the generations.Footnote 4

The oppression of Indigenous peoples and their cultures increases the risk that an Indigenous senior may experience social isolation. Although the extent of social isolation among Indigenous seniors has not been quantified, it is estimated that between 19%Footnote 5 and 24%Footnote 6 of seniors are socially isolated.

This document is intended to help Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals, families, community groups, organizations, service providers, policy-makers and others prevent and address the social isolation of Indigenous seniors. More specifically, its purpose is to:

- Raise awareness of social isolation of Indigenous seniors. The risks and protective factors for social isolation are discussed in Part 1.

- Provide tools for engaging with Indigenous seniors, including examples of successful social innovation through community partnerships. Tools and examples are included in Part 2.

The information and tools contained in this supplement can be used to facilitate community conversations in a variety of settings: on reserves, in remote or rural areas, in small towns, or in larger cities. This document is a supplement that builds on the original toolkit by adding information that may be useful for better engaging and working with Indigenous populations specifically.

Part 1: Social isolation of Indigenous seniors

Diversity of the Indigenous community

[Indigenous] peoples have occupied the territory now called Canada for thousands of years. Many diverse and autonomous peoples lived in this territory and had distinct languages, cultures, religious beliefs and political systems. Each community or culture had its own name for its people and names for the peoples around them.Footnote 7

Indigenous peoples in Canada are heterogeneous and have maintained a high degree of cultural diversity. The Canadian Constitution (the Constitution Act, 1982) recognizes three groups of Indigenous peoples: First Nation (or Indian), Métis and Inuit. Within each of these groups are many different communities. Although individual Indigenous persons may share common experiences, their communities would not necessarily have much in common culturally. There are more than 630 First Nation communities in CanadaFootnote 8 and 54 Inuit communities across the northern regions of Canada.Footnote 9 While Métis persons are also dispersed across Canada, according to the 2016 Census, they were the most likely to live in a city, with 62.6% living in a metropolitan area.Footnote 10

In addition to this cultural diversity, there is also a high degree of geographic diversity. Features of geographic diversity may heavily influence whether and how Indigenous seniors experience social isolation. For instance, for seniors who live in northern communities or remote areas, geographic isolation could pose a significant barrier to participation in social events. They may live several hours’ drive from a gathering place. This challenge could be amplified if it is compounded by situations such as lack of access to reliable transportation or living too far from friends and family to get help with mobility or transportation.

Indigenous seniors who live in rural areas and small towns, may also face social isolation due to a lack of supportive Indigenous organizations. While small towns may have general services for seniors, non-Indigenous organizations might not be as knowledgeable about the unique circumstances of Indigenous seniors. Seniors’ organizations or other non-Indigenous organizations may find it challenging to ensure that the small numbers of Indigenous seniors living in their communities are not socially isolated. Larger cities may have Indigenous organizations that host activities for Indigenous seniors and provide other services; however, the challenge may be identifying Indigenous seniors who experience social isolation and ensuring they are able to participate.

Language and culture

Indigenous seniors continue to play important roles in protecting and passing on their cultural identities and languages to their families and communities. Language plays a vital role in preserving cultural and traditional teachings among Indigenous communities while enhancing pride and identity. At the same time, language and culture have been noted as protective factors against health crises and social isolation in Indigenous communities.Footnote 11 Unfortunately, a contributing factor to social isolation among Indigenous seniors is a past characterized by suppressed Indigenous language and culture.

Throughout the pre-Confederation period, European and Aboriginal peoples approached education and Treaty making with different purposes. Aboriginal peoples regarded Treaties as a tool to maintain cultural and political autonomy. Education was a means of ensuring that their children, while remaining rooted in their cultures, could also survive economically within a changing political and economic environment. The British viewed both Treaties and schools as a means of gaining control over Aboriginal lands and eradicating Aboriginal languages and cultures. They wanted Aboriginal people to abandon their languages and cultures.Footnote 12

For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can best be described as “cultural genocide.”Footnote 13

As a result, most Indigenous languages are now considered at risk, and the proportion of Indigenous people who speak Indigenous languages as a mother tongue is declining. “In 2016, 15.6% of the Aboriginal population reported being able to conduct a conversation in an Aboriginal language. This is compared with 21.4% in 2006.”Footnote 14

Despite these declines in Indigenous languages as first languages, they have been experiencing a revival as second languages. In 2016, there were 260,550 Indigenous people who reported being able to speak an Indigenous language—which was more than the 208,720 Indigenous people who speak Indigenous languages as a mother tongue.Footnote 15 A closer analysis of different age groups seems to confirm the revitalization of Indigenous languages: the percentage of Inuit children under age 14 who could speak Inuktitut was 65.2%, compared with 61.3% of Inuit seniors.Footnote 16

Despite past attempts to suppress Indigenous languages, some Indigenous seniors still speak their language primarily, may not be fluent in English or French, and may need a translator. Although finding a translator could prove challenging, there are persons who may speak the appropriate Indigenous language as a second language. Seniors’ families are often a good source. Indigenous persons on-reserve may also be able to provide some support. “In 2016, a higher percentage of First Nations people with Registered Indian status living on-reserve were able to speak an Aboriginal language (44.9%), compared with those living off-reserve (13.4%).”Footnote 17

Social determinants of health and health inequities

Social determinants of health refer to the social, economic, cultural and political factors that impact a person’s health. They can include poverty, employment, working environments, education, geographic location, access to health services, housing, social status, social support networks, food security, language, gender and culture.Footnote 18

Social isolation is associated with health inequities because many of the risk factors for social isolation are more prevalent among socially disadvantaged groups.Footnote 19Social disadvantage describes the situation of not having the opportunity to participate fully in economic, social, political and cultural relationships, and has been associated with vulnerability to negative health outcomes.Footnote 20 Long-standing social disadvantage for Indigenous people in Canada is an offshoot of government policies created during colonization. According to historical accounts: “In the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, the Indian Department became the vehicle for the expression of the new plan of "civilisation". Based upon the foundation that it was Britain's duty to bring Christianity and agriculture to the First Nations people, Indian agents shifted their roles from solidifying military alliances toward encouraging First Nations people to abandon their traditional ways of life and to adopt a more agricultural and sedentary, more British, life style. By doing so, First Nations people would become assimilated into the larger British and Christian agrarian society.”Footnote 21

In a 2007 to 2010 report, Statistics Canada noted that urban First Nation, Métis and Inuit reported poorer health conditions compared with non-Indigenous people, including higher smoking rates (two times higher), higher obesity rates, and greater food insecurity.Footnote 22 According to Statistics Canada, “food insecurity occurs when food quality and/or quantity are compromised, typically associated with limited financial resources.”Footnote 23

Demographic profileFootnote 24: A growing population

The Indigenous population in Canada is growing. This is largely due to a combination of relatively high fertility rates, increased life expectancy, and more people newly identifying as Indigenous on the Census. Among Indigenous Canadians, a growing proportion are seniors: from 2006 to 2016, the percentage of the Indigenous population that was 65 years of age or older grew from 4.8% to 7.3%.Footnote 25

According to population projections, the proportion of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations 65 years of age and older could more than double by 2036.Footnote 26 Here are some other interesting statistics:

- There were 65,025 Inuit in Canada in 2016, up 29.1% from 2006. Close to three-quarters (72.8%) of Inuit lived in Inuit Nunangat.Footnote 27

- In 2016, there were eight metropolitan areas with a population of more than 10,000 Métis: Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa–Gatineau, Montréal, Toronto and Saskatoon. Combined, these areas accounted for just over one-third (34.0%) of the entire Métis population.

- While the First Nations population in the Atlantic Provinces is relatively small (73,655, or 7.5% of the total First Nations population), it more than doubled between 2006 and 2016. Much of the increase is most likely the result of changes in self-reported identification—that is, people newly identifying as First Nations on the Census.

- The First Nations population was concentrated in the Western provinces, with more than half of First Nations people living in British Columbia (17.7%), Alberta (14.0%), Manitoba (13.4%) and Saskatchewan (11.7%).

- Almost one-quarter (24.2%) of the First Nations population lived in Ontario—the largest share among the provinces—while 9.5% lived in Quebec.

- While First Nations people accounted for 2.8% of the total population of Canada, they accounted for 10% of the population in Saskatchewan and Manitoba (10.7% and 10.5%, respectively), and almost one-third of the population in the Northwest Territories (32.1%).Footnote 28

The Indigenous population in CanadaFootnote 29, Footnote 30

Please refer to Statistics Canada’s infographic entitled The AboriginalFootnote 31 population in Canada, 2016 Census of Population, which provides a portrait of the Indigenous population in Canada, including age, growth, population count and the diversity of Aboriginal languages.

Increasingly urban

Indigenous people are increasingly urban, with more than half residing in towns and cities.Footnote 32 The cities with the largest Indigenous populations in 2016 were Winnipeg (92,810), Edmonton (76,205), Vancouver (61,460) and Toronto (46,315).Footnote 33

Research estimates (2012) suggest that 52% of the 82,690 Indigenous seniors in Canada now live in off-reserve population centresFootnote 34, Footnote 35 and reported moving to these centres within the last 10 years after living in their home communities most of their lives. The composition of the urban Indigenous population was estimated to be 50% First Nations, 43% Métis and 3% Inuit.Footnote 36, Footnote 37

Some Indigenous seniors leave their home communities to gain access to health services and supports. Non-insuredFootnote 38 Indigenous First Nations seniors living on reserves may move to cities for access to long-term care facilities, to avoid frequent travel for services that are not available in their home communities, or to be closer to family. This is especially true for those in northern and more isolated communities, where some of the more vulnerable seniors are forced to relocate to urban centres to access the medical care they need.Footnote 39

The move to off-reserve population centres increases the risk for social isolation, as these seniors are separated from the social and cultural supports they are familiar with. In 2012, most urban Indigenous seniors were living with family; among those who reported living alone, there were more women than men. An estimated 8% of urban Indigenous seniors reported lack of social supports and said they had no one to call upon in times of need.Footnote 40 Among all seniors in population centres, Indigenous seniors tended to be poorer, have more experiences with food insecurity, and face more chronic health problems (such as high blood pressure, arthritis, heart disease, diabetes and depression) than non-Indigenous seniors.Footnote 41

Preventing social isolation: protective factors

Seniors with more risk factors face a greater likelihood of social isolation. Because the occurrence of risk factors is high for Indigenous seniors, it is important to find ways to create awareness of social isolation and protect against it. Protective factors could help them remain socially involved.Footnote 42 A 2007 Assembly of First Nations discussion paper on social determinants of health supports the World Health Organization’s acknowledgement that social support and good social relations are important to overall healthFootnote 43—an assertion that is also supported by many studies that have found a link between socio-economic status and health, well-being and longer life. To foster positive social inclusion and support, it is important to reach out to Indigenous Elders.

(Note: Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume I: Understanding the issue and finding solutions has additional general information about protecting seniors from social isolation.)

Awareness of traditional cultural values, languages and kinship systems

A study of Indigenous communities has found that Indigenous culture protects vulnerable communities in several ways. Among the protective factors are connection with the land, traditional medicine, spirituality, traditional foods, traditional activities and language.Footnote 44 These themes provide insight into the values held by Indigenous seniors.

Being aware of key protective factors for Indigenous seniors—such as the interconnected nature of the individual, the land, family and community in traditional cultures—is necessary to plan strategies that address their needs in a holistic fashion. Offering family-friendly events and providing safe and reliable transportation as needed are two examples. This can build confidence and social well-being. Activities and programs that provide practical social support to Indigenous seniors (whether in the form of practical help or friendship) can be important protective factors against social isolation. In health research, there is a growing awareness that social support (positive interaction, emotional support, affection) is a key determinant for thriving health, especially for Indigenous people, whose worldview is based on relationships with family, community, land, nature and Creator. Some ideas are described in the lists below.

Fostering good relationships and helping each other are traditional values that have long acted as protective factors to counter social isolation among Indigenous peoples. Indigenous families traditionally lived close to each other and cared for one another. Families and communities respected Elders for the wisdom and knowledge they had gained from life experience.

Acknowledging and respecting the importance of Indigenous languages to Indigenous seniors can help address social isolation, and can alert service providers and others that translation services and Indigenous staff may be needed to help the more vulnerable seniors. Supporting Indigenous languages through programs, policies and planned events can act as a protective factor for at-risk seniors who may only converse in their own language and may be anxious about engaging in broader social settings. Finding out about the main languages spoken in an area, utilizing translators when needed, and inviting seniors’ families and friends to social events can help make Indigenous seniors feel more comfortable and better able to communicate in social settings.

The following lists identify factors that can help to ensure that Indigenous seniors remain socially engaged.

Protective factors for all seniors

- Being in good physical and mental health

- Having sufficient income and safe housing

- Feeling and being safe in neighbourhood

- Having good literacy and communication skills

- Having satisfying relationships

- Having a supportive network

- Feeling valued

- Being able to access local services offered by community organizations, government programs and services, and health agencies

- Feeling productive in society

- Having access to transportation

- Having higher education

Additional protective factors for Indigenous seniors

- Participating in ceremonies

- Having social support (individual, family and community) that provides practical help, positive interaction, emotional support, and friendship

- Belonging to a community that promotes respect for the Indigenous way of life and cultural values as social norms

- Belonging to a community that promotes respect for Indigenous seniors for their wisdom and knowledge

- Belonging to a community that appreciates Indigenous resilience and the diverse narratives of Indigenous experience

- Having access to social events that respect Elders and experiencing positive interactions that make them feel comfortable

- Having translators when needed

- Having social contact in the form of phone calls, visits, excursions and/or other interactions

- Having access to culturally sensitive health care services within the community

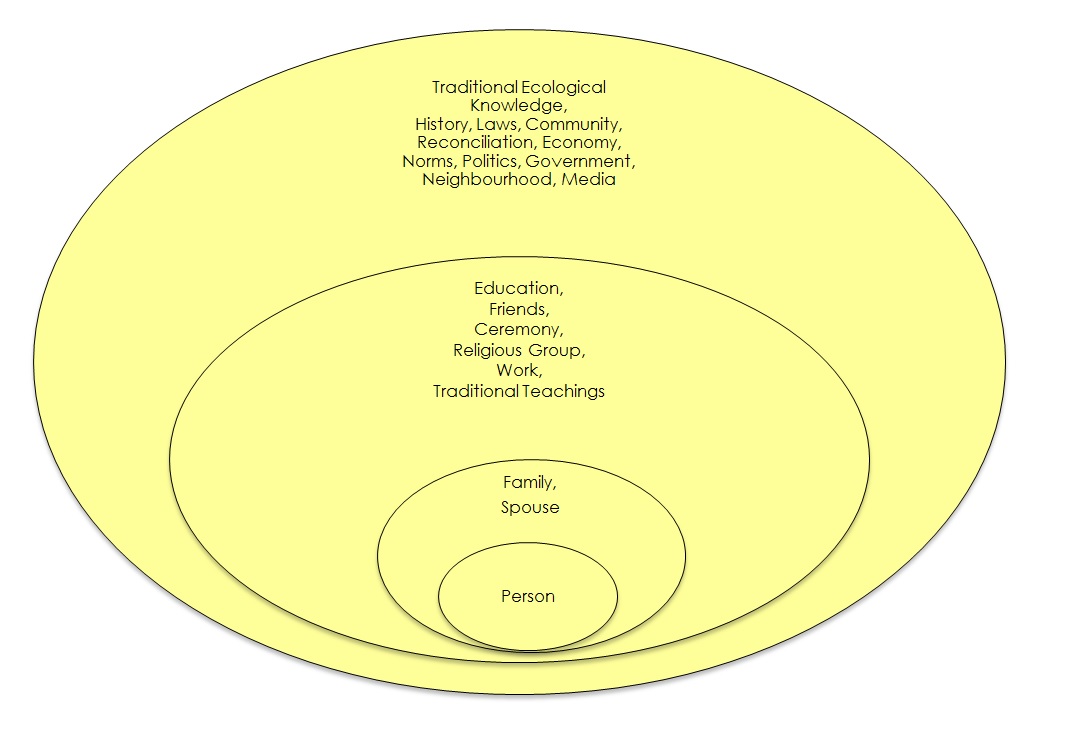

Text description

The diagram is of four circles. The smallest circle represents the person, the next biggest circle contains the smallest circle and it represents the family and the spouse. The next circle contains the first two and it represents education, friends, ceremony, religious group, work, and traditional teachings. The biggest circle contains all of the smaller circles and it represents traditional ecological knowledge, history, laws, community, reconciliation, economy, norms, politics, government, neighbourhood and media.

Indigenous support systems were traditionally based on the values of individual wellness, shared responsibility, shared care, and kinship connections (family and friends). Each layer of the above diagram represents these different spheres of responsibilities that extend beyond the individual. The layers are interconnected and foster harmony by promoting responsibility and reciprocity. Although Indigenous cultures are diverse, they share a belief in the interconnectedness of all living things. The circles represent interaction and interdependence. Both within the circles and between the circles, there are reciprocal relationships; for example, individual to family, and family to community.

Social isolation risk factors

Seniors risk becoming socially isolated when they go through life transitions, such as losing a driver’s license or having their adult children move out, or live in social and environmental conditions associated with social isolation. Certain experiences are common risk factors for most Indigenous seniors, but many diverse experiences that are unique to individuals can also enhance risk.

Examples of common social and economic conditions that are considered risk factors are poverty and inadequate transportation. For example, low-income seniors may lack the funds to pay for memberships or activities; similarly, their budgets might be too restricted to allow them to dine out with family and friends or incur transportation costs to visit or attend events.

Life transitions that can trigger social isolation include retirement, illness, death of a spouse, loss of a key caregiver, moving to a different city, or losing a driver’s licence. Indigenous seniors and their families are often in the difficult position of leaving their home reserve and community to access health and social services. While any of these issues on their own could lead to social isolation, too many at once can be particularly challenging for a senior to address on his or her own.

Indigenous seniors are also at higher risk of social isolation than other seniors due to their generally poorer physical, social and economic conditions. Among Indigenous seniors in cities, 23% were found to have low income compared with 13% of non-Indigenous seniors. Low income was found to be more prevalent among Indigenous senior women than men: 26% of Indigenous senior women were considered to have a low income compared with 18% of Indigenous senior men. Illustrating the compounding effect of combined risk factors, higher percentages of Indigenous seniors who lived alone were part of the low-income population compared with those who lived with a spouse or partner. A relatively high percentage of Indigenous senior women (38%) live alone, almost half (49%) of whom are part of the low-income population.

Another risk factor associated with a lack of social support is food insecurity: 9% of Indigenous seniors reported food insecurity compared with 2% of non-Indigenous seniors. Those who experience food insecurity may be in that situation because they are in a less supportive social network and are unable to get help from friends or family. For others, food insecurity can contribute to social isolation because people who experience it may use alternatives for getting food that do not fit social norms.Footnote 45 For example, a person without enough food at home may have to visit a food bank. For an Indigenous person, not having access to traditional food has been described as an alienating experience. As mentioned earlier, health concerns can also lead to social isolation. Among Indigenous seniors, 88% of women and 86% of men report having at least one chronic condition,Footnote 46 whereas the percentage for Canadian seniors overall is 71%.Footnote 47

Lists of Key risk factors associated with social isolation for all seniors

Demographic

- Living alone

- Over 80 years of age

- Being a caregiverFootnote 48

Health

- Poor physical or mental health

- Mobility issues

- Frailty

- Victim of older adult abuse, including neglect and financial abuseFootnote 49

Social and cultural

- Losing a spouse

- Lack of friends or family

- Unsupportive family systems

- Lack of access to transportation

- Loss of independence

- Lack of communication access, such as no telephone or cell phone

- Discrimination

Economic

- Inability to afford essentials (healthy foods, medication)

- PovertyFootnote 50

Additional risk factors for Indigenous seniors

- Racism

- Living in communities with high crime ratesFootnote 51

- Past institutional experience

- Residential school trauma

- Living in overcrowded housing

- Moving into the city or town from a rural reserve

- Insufficient or remote family supports

- Cultural differences

- Language differences

- Political/jurisdictional isolation

- Lack of access to services

- Lack of culturally appropriate activities and/or ability to access activities

- Lack of appropriate health care and community services on reserves

Case studies

The following case studies describe common scenarios that illustrate both the risk factors and protective factors that Indigenous seniors face. These stories may help generate discussions as part of community “idea exchange” events described in Part Two of this document.

George is 75 years old and only speaks Dene. He lives in a small northern community. He has problems walking as well as health problems associated with diabetes and arthritis. He can no longer care for himself and needs more help than home care can provide. His wife passed away a few years ago. He now lives with his daughter and her family. He likes it there and enjoys continuing the long-held tradition of passing on knowledge from generation to generation through storytelling. He treasures storytelling as an oral tradition to teach about cultural beliefs, values, customs, ceremonies, history, practices, relationships and ways of life. George loves telling stories about his family and history to his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The grandchildren enjoyed sharing this tradition with him when they were younger, but now they prefer their cell phones and high-tech devices. There is very little conversation, and he feels alone. George likes to visit with other Elders and attend community events when they are offered, but he does not want to bother people for rides. He does not have reliable transportation or assistance for his difficulties with walking.

Mary lives on a small rural reserve, with the closest town three hours away. She is 84 years old and has been widowed for many years. She speaks Cree fluently and understands enough English to get by. She is afraid to go shopping alone or go into town because she has experienced racism. She sometimes feels powerlessness and shy or fearful about being alone among “white” strangers and not being able to speak English very well. Mary attended residential school as a child and remembers being punished for speaking Cree, and while she later forged a good life with her late husband, she was still dealing with some old fears. She has eight children and many grandchildren. Mary has a pension and continues to live in her own two-bedroom house. Her granddaughter, Josie, and her two children live with her. Josie works part-time, helps Mary around the house and sometimes takes her shopping or blueberry picking in the summer. However, Josie has a boyfriend who is disrespectful toward Mary, which leads to disagreements between Mary and Josie.

Things are getting increasingly difficult. Mary has poor eyesight and a heart condition, is diabetic, and needs a walker because of her arthritis. A home-care nurse makes regular visits on weekdays, and sometimes the home health aides will drive her to her medical appointments in the city or take her to the Elder suppers and occasional community events. Mary loves being active this way, but it is becoming more of an effort because she needs more help to get anywhere. Mary feels increasingly isolated and anxious. She overheard the nurse and her granddaughter talking about her poor health and the possibility of moving her to a long-term care home in the city (there are none on the reserve). She wants to stay in her home. She is afraid of being alone in some long-term care home where no one speaks her language, no one understands her culture, and traditional foods are not available. She anticipates an experience much like her experience in residential schools, and is worried that they might not treat her well because she is Indigenous. She wants to die at home when her time comes.

Irene is a retired 77-year old Métis Elder who lives with her 83-year old husband. Both speak Michif and English. All their children have moved away except for one daughter, who lives in the city. Irene and her husband have always lived in towns, but moved to the city about 20 years ago. Irene grew up in a small rural Métis community and still misses it. She had been close to her grandmother and relatives who lived in the reserves nearby, and felt comfortable going back and forth to their homes. Things changed when she grew up, got married and moved to the city. Her life was busy: filled with school, working and raising children. Getting older was another change, but Irene was appreciating some of its benefits. In Indigenous culture, Elders are valued as teachers, and it was fun for Irene and her husband to go to Métis community events. However, a stroke five years ago left her with increasing mobility problems, and she is no longer able to drive. Her husband is also now having serious health problems, and Irene finds they are needing help more frequently. Irene has no social life now, apart from her daughter and place of worship, because Irene is caring for her husband. She probably would not go to her place of worship either, without the van that picks seniors up every Sunday.

Irene is more worried about her husband’s failing health than she is about herself. He is showing signs of Alzheimer’s, but Irene is convinced she can continue to take care of him. She feels tired and alone sometimes, but feels good about helping her husband. Although their daughter helps when she can, Irene still does most of the work in the house. Irene is now a full-time caregiver for her husband. Her family and friends are concerned. They think Irene should get respite care or help around the house, but she cannot afford it, and even if she could, it would have to be someone who understood and respected Métis culture.

Creating opportunities for Indigenous seniors to engage

Recovery of Indigenous cultures, language, traditions and ways of knowing can improve Indigenous well-being.Footnote 52 These can be protective factors. Creating opportunities for Indigenous seniors to engage in social events that they can relate to—in settings where they feel comfortable, where they can understand the language and what is being communicated, and where they feel culturally safe sharing their stories and ideas (such as round dances and pow wows)—is crucial. Protective factors that reflect traditional values, such as helping frail Elders on a one-to-one basis, can strengthen Indigenous seniors so that they can participate in safe social activities with others and feel more included and valued.

It is also important to consider seniors who have had to leave their communities to live in long-term care homes. A history of colonization may contribute to a distrust of Western medicine and mainstream institutions. Indigenous seniors and their families may have concerns about non-Indigenous organizations. Indigenous seniors may fear that their families and friends might not be able to visit them, particularly if they are placed in a home far away from the community. Although this fear may not be unique to Indigenous seniors, their anxiety may be higher due to experiences of institutionalization and the residential school system. The protective factors of Indigenous culture and community can help Indigenous seniors who find themselves in long-term care. Although it may be difficult to find staff who are fluent in a given Indigenous language, it would be helpful to ensure that, at a minimum, staff understand Indigenous culture, values and attitudes; incorporate Indigenous recreation programs (such as crafts, games and music) into programming; and make traditions available by inviting the Indigenous community for traditional ceremonies,Footnote 53 offering traditional meals, and providing a space for family gatherings.

An illustrative example is provided below. This Elder is experiencing multiple risk factors of social isolation. In cases like this, the events coordinator(s) in the long-term care facility could arrange with community leaders to organize a visiting program. Support from the Elder’s family is also important to help recognize her vulnerability to social isolation and access collaborative solutions.

My mother is 85 years old. She moved from the north into a long-term care home in the city. She only speaks Michif. I wish there were workers and volunteers who spoke the language and could help her when I am not around.

Consequences of social isolation for Indigenous seniors

The consequences of social isolation and neglect include greater health, social and economic risks which, in turn, are linked to deteriorating well-being and premature death.

For Indigenous seniors, poor health combined with losing kinship and community ties can be especially isolating. Inward fears and grief from the loss of a way of life can lead to depression and social isolation for those who lack social, economic, health and relational supports.

Other consequences of social isolation include:

- Increased vulnerability that could lead to neglect as well as physical, emotional and financial abuse by othersFootnote 54

- Mental health risks related to stress associated with economic issues, such as food insecurity and fears of homelessness

- Health risks, such as increased drinking, smoking, being physically inactive, and having a poor diet

- Loss of personal dignity, economic self-sufficiency and independence

- Inability to access available services

Social isolation of seniors also has consequences for the community, since Indigenous seniors play an important role in language and cultural preservation. Such cultural isolation can contribute to a loss of language and culture for Indigenous society as seniors begin to lose their role in cultural and language preservation.

For more information about the general consequences of isolation for all seniors, see Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume I: Understanding the issue and finding solutions.

Community-level success stories

Community-level success stories help provide important principles and ideas that can contribute to preventing and addressing the social isolation of Indigenous seniors. Here are a few to help illustrate rural reserve, northern reserve/community, and small town/city initiatives.

Shared caregiving in Mitho-PimachesowinFootnote 55

- Purpose: To address the northern/urban divide and help Indigenous seniors better transition into urban-based health care settings

- Type of Community: Reserve — urban

- Jurisdiction: Saskatchewan

- Target Population: Indigenous seniors in frail health from northern multi-community Bands considering long-term care outside the community

- Time frame: Ongoing

- Organizations involved: Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation Health Services Home Care; various long-term care facilities where seniors relocate (Prince Albert, Saskatchewan; Flin Flon, Manitoba)

- Project Description: This is essentially a shared caregiving approach between home care, primary care, seniors and their families. Seniors are supported in their homes (medically and socially) until higher health needs necessitate some of them to move to a city. Community events offered include transportation, Elder suppers, blueberry picking and shopping excursions. Case management planning is used to coordinate the care of seniors, and is done in consultation with those affected (the Elder, their family and health staff). This support includes transitioning into urban-based care homes.

- Outcomes: Collaboration and collective impact that gives voice to seniors and families through care plans and offers medical and social supports can help engage seniors and promote their personal dignity.

Edmonton Aboriginal seniors centreFootnote 56

- Purpose: To create a place for Indigenous seniors in the city

- Type of Community: City

- Jurisdiction: Edmonton, AB

- Target Population: Indigenous seniors in the city

- Time frame: Ongoing

- Organizations involved: Edmonton Aboriginal Seniors Centre and various levels of government

- Project Description: The Aboriginal Seniors Centre is a non-profit organization that has been around for more than 30 years. It holds a holistic vision of wellness and strives to foster a sense of community among Indigenous seniors in Edmonton. It offers a drop-in program, housing registry, and programs in nutrition, foot care, computer literacy and traditional arts. It organizes events such as cultural, spiritual and community field trips and hosts celebratory meals and activities for holiday seasons.

- Outcomes: The centre provides a place for Indigenous seniors to engage in positive social activities, and offers tangible supports for their physical and mental needs through targeted programs.

Community support services programs by the Métis Nation of OntarioFootnote 57

- Purpose: To offer essential support to Métis families and seniors so they can stay at home for as long as possible

- Type of Community: Métis communities in a region

- Jurisdiction: Ontario

- Target Population: Métis seniors who are isolated or have health issues

- Time frame: Ongoing

- Organizations involved: Métis Nation of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and other collaborating agencies

- Project Description: The program has an estimated 14 regional sites, including Ottawa, Thunder Bay and Sudbury. It offers a variety of services to Métis seniors in these urban centres, including information, advocacy and transportation. It coordinates with other community agencies to provide adult day programs for seniors, meals on wheels, friendly visits and caregiver supports, and works with volunteers.

- Outcomes: The program offers an important cultural base for Métis seniors, and provides needed services, such as transportation. It provides advocacy support and engages them in other programs in the broader community.

Tungasuvvingat Inuit (TI)- means “A place where Inuit are welcome”Footnote 58

- Purpose: To offer province-wide programs, services and advocacy to Inuit

- Type of Community: Inuit-specific

- Jurisdiction: Based in Ottawa, Ontario

- Target Population: Inuit in Ontario and urban areas across the country

- Time Frame: Ongoing. It has been operating for 30 years.Footnote 59

- Organizations Involved: Multiple government agencies (for example, Government of Ontario, Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development Canada), non-profit service agencies (for example, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Shepherds of Good Hope), Inuit organizations (for example, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) and fundraising activities

- Project Description: TI is a registered, non-profit, charitable organization—a one-stop shop resource centre for Inuit. It offers a community of frontline integrated services that provide social supports, cultural activities, counselling and crisis intervention. For example, a health systems navigator helps northern Inuit who come to the south for medical care. Cultural education programs and other holistic, culturally responsive services offer Elders’ teas, translation, monthly feasts, traditional games, counselling, housing and other support services.

- Outcomes: Helps Inuit adjust to southern urban communities by providing culturally specific urban programs and services.

Winnipeg Aboriginal Senior Resource CentreFootnote 60

- Purpose: To increase access to information, resources and supports that directly improve the health and well-being of Indigenous seniors in Winnipeg and provide opportunities for participation, safe supportive environment, and opportunities to pass traditional knowledge on to younger generations

- Type of Community: Indigenous seniors in Winnipeg

- Jurisdiction: Manitoba

- Target Population: Indigenous seniors

- Time Frame: Ongoing

- Organizations Involved: United Way, Volunteer MB, and other fundraising organizations

- Project Description: The Winnipeg Aboriginal Senior Resource Centre is a non-profit, charitable organization that offers multiple support services to Indigenous seniors in a culturally respectful holistic environment. These include arts and crafts, sewing, a peer helper program, cultural workshops, health and wellness workshops, advocacy and referrals, bi-weekly bingos, monthly and annual celebrations, and sharing circles with youth, among others.

- Outcomes: These activities help improve the health and well-being of Indigenous seniors through a blend of programs designed to support and socially engage them.

Core principles of Indigenous social innovation

Social innovation is defined as “community organizations, governments and public institutions, researchers, seniors and businesses working together and combining resources and ideas to make new plans and tools that address social problems in creative ways.”Footnote 61 The examples of social inclusion initiatives above demonstrate the core principles needed for social innovation that meets the needs of Indigenous seniors.

Practical strategies to engage Indigenous seniors

Indigenous people are diverse in terms of their experiences, languages, cultures and values. Strategies for engaging them will differ with each location or area. Principles and ideas gleaned from broader research on Indigenous engagement can inform local strategies to prevent the social isolation of Indigenous seniors.

Below are some examples of best practices and lessons learned from various groups engaging with Indigenous communities.

Best practices for Indigenous engagement

- Promote authentic engagement in decision-making by developing plans in partnership with Indigenous communities. Reach out and develop partnerships with Indigenous and non-Indigenous agencies that support Indigenous seniors and families. Start with existing contacts and let word of mouth referrals contribute to the building of an informal network of contacts with Indigenous seniors, families and agencies.

- Develop an Indigenous Engagement Vision Statement to recognize the historic and contemporary importance of Indigenous people, community, culture, tradition and governance structure. Ensure that the different needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis are recognized. A culturally responsive approach to program and service planning is key. An example is to ensure language translation services for the programs and services offered. Hiring Indigenous people or engaging Indigenous organizations can also facilitate effective relations and services for seniors.

- Secure sustainable funding resources for regular activities and programs.

- Ensure involvement and input from Indigenous seniors in the design and development of services, activities and events.

- Learn about local protocols for engagement and create a welcoming environment of mutual respect. The best places to learn about these are through local Indigenous organizations. In larger centres, universities may also have Indigenous cultural resource liaison staff who can offer advice. Find out what the local Indigenous protocols are as far as opening/closing prayers, gift-giving and, if needed, translation. It will be especially useful to reach out to Elders to learn about protocol for meetings (Please refer to Appendix F: Protocol for Indigenous Elders for guidance on inviting and including Elders at an event). This also provides an opportunity for Elders to show they are valued and are passing on knowledge. Facilitate access to social engagement events by creating informal settings, offering food and beverages.

- Involve family members as partners in decision-making. Recognize Indigenous family structures (extended families are important).

- Provide cultural awareness training for volunteers to help reach the Indigenous community. This is critical, and, if necessary, would include paid instructors to deliver the training prior to engagement.

- Develop outreach programs for Indigenous seniors and senior shut-ins (in other words, those who are immobile, confined to their homes or in long-term care facilities).

- All levels of government—federal, provincial, municipal, Indigenous—and community agencies are important partners in any social innovation.

It takes time to build good working relationships and bridge cultural differences. The lessons learned through past programs can support partnerships across sectors and individuals through collective and coordinated efforts. These can start out as small and informal one-to-one chats with a senior over tea or coffee, or small-group discussions in settings designed for comfort (maybe circles or around a small table). If desired, these initiatives can be expanded to larger workshop settings.

As First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities access and revitalize their spirituality, cultures, languages, laws, and governance systems, and as non-Aboriginal Canadians increasingly come to understand Indigenous history within Canada, and to recognize and respect Indigenous approaches to establishing and maintaining respectful relationships, Canadians can work together to forge a new covenant of reconciliation.

Despite the ravages of colonialism, every Indigenous nation across the country, each with its own distinctive culture and language, has kept its legal traditions and peacemaking practices alive in its communities. While Elders and Knowledge Keepers across the land have told us that there is no specific word for “reconciliation” in their own languages, there are many words, stories, and songs, as well as sacred objects such as wampum belts, peace pipes, eagle down, cedar boughs, drums, and regalia, that are used to establish relationships, repair conflicts, restore harmony, and make peace. The ceremonies and protocols of Indigenous law are still remembered and practised in many Aboriginal communities.Footnote 62

The next section provides tools and ideas for engaging with Indigenous seniors.

Part 2: Tools and examples of ideas exchange events for Indigenous seniors

Why use the toolkit?

Many Indigenous seniors face exclusion and racism, both of which contribute to social isolation. For this reason, community initiatives benefit from acknowledging the history of colonialism and its present-day impacts. The aim is reconciliation and healing for past injustices with a focus on moving forward toward a better future for all.

As a first step to finding socially innovative solutions, consider informal conversations with the public, business, and community organizations to generate awareness about the social isolation of Indigenous seniors. Networking and connecting with people and agencies that work with Indigenous seniors in the community is important because of their experience with and knowledge of local Indigenous seniors, cultural considerations and specific protocols. These informal discussions could lead to the development of productive gatherings. More formal meetings will take time, and can vary in size and length depending on community readiness and willingness to participate.

To build strong relationships, it is important to be aware of and incorporate Indigenous protocols, cultural values and traditions into all planned events. Learning about the unique background of each community will increase your understanding of what is important to that community and what its members are proud of. Indigenous Elders and leaders are an invaluable resource in learning how to incorporate Indigenous oral cultures into events. This may also be achieved with help from interpreters, family and gifts, and with respect for Indigenous stories and cultural values. Indigenous cultural practices are diverse across the country, so it is important to find out what the local protocols are by asking Indigenous agencies and Elders in the area.

The tools that follow can help all facilitators to work with Indigenous communities, but getting facilitators who are Indigenous themselves (or who have prior Indigenous engagement experience) is best.

How to use the toolkit

Seniors (or any interested group) can lead conversations and strategies to find solutions. Gatherings can vary in length, group composition, number of participants and dialogue format. Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit provides detailed strategies for ideas exchange events that provide the foundation for this supplement, which is specific to the social isolation of Indigenous seniors.

The purpose of the ideas exchange gatherings is to build awareness, share information, build partnerships, and create opportunities to work together to address the social isolation of Indigenous seniors. The events can be organized for individual organizations or they can bring together organizations from different sectors to work together on community-wide solutions. The toolkit summarizes possible approaches to the dialogue and outlines specific questions for reflection to develop solutions.

How to conduct an event

Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit provides tools and techniques for to guide facilitators through three types of events: a partial-day event, a one-day event and a two-day event. Tools include sample agendas and suggested activities.

In hosting these events, a common, respectful practice in most Indigenous communities is to invite an Elder to offer opening and/or closing prayers and present him or her with a gift. In some Indigenous cultures, tobacco is an appropriate gift; however, this varies across cultural traditions. It is also respectful to acknowledge the traditional Indigenous territory of the area. For example, say, “We welcome you to Saskatoon, situated in Treaty 6 territory, traditional lands of First Nations and Métis people.” Such an acknowledgement is a reminder of the sharing spirit of the Indigenous people and the Creator. It is helpful to ensure that the Elder has transportation and that a translator is available if necessary.

As a courtesy, extend invitations to all levels of Indigenous government (such as First Nation bands, tribal/regional councils, and Indigenous political organizations), particularly for bigger events.

Some of the examples and approaches used in the Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit will need to be adapted to include content that specifically addresses Indigenous seniors, such as the sample invitation, PowerPoint presentations, case study scenarios, community assessment and event planning checklist. They could be adapted by including references to Indigenous culture and practices.

The Social Isolation of Seniors, Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit includes a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis and the Theory of Change exercise; note that these may not work effectively for small Indigenous events. You may find it helpful to set aside some time to allow participants to share their experiences and challenges instead. The facilitator should be prepared to be flexible and should have the skills to address difficult topics or conversations should they arise during the event.

To help with organizing the event, this document includes the following resources:

- How to Adapt the Event Planning Checklist (Appendix A)

- Sample Invitation (Appendix B)

Other resources that could be helpful in ensuring an event specifically addresses Indigenous seniors are:

- Presentation Slides (Appendix C)

- Case Study (Appendix D)

- Handouts: Additional Considerations for Indigenous Seniors (Appendix E)

- Protocol for Indigenous Elders (Appendix F)

- Indigenous Peoples of Canada: Demographic Profile (Appendix G)

- Additional Resources for Organizers and Facilitators (Appendix H)

Appendix A: Event planning checklist

The Event Planning Checklist from Social Isolation of Seniors - Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit has been adapted here with minor modifications to include the Indigenous community and Indigenous seniors

- Form a multi-sector planning committee that includes local champions from the Indigenous community.

- Make connections through personal networks or conduct Web searches of Indigenous organizations and service agencies in the area. Detailed knowledge of local senior and community resources will help generate discussions at ideas exchange events. Participants will also share valuable information that provides a picture of the Indigenous community. Useful information could include the population of Indigenous community, the proportion of seniors, and population characteristics (age, gender, housing, marital status, income level, employment status, and Indigenous background: First Nation, Métis, Inuit, culture, language). It would also be useful to include information on the resources available to Indigenous seniors, including agencies (like the Friendship Centres), transportation services, housing and other social programs.

- Decide who to invite. Indigenous peoples come from diverse cultures and backgrounds. It is important to find community context and connect with people and groups who work with Indigenous seniors and families. Contacting Indigenous agencies that provide public services to Indigenous people is a good place to start. A website search of Indigenous agencies in the area is necessary. The list should include Indigenous seniors, families, community organizations, Indigenous business and political leadership.

- How many participants will be invited?

- Will participants be invited by individual invitations or open calls?

- Set the date, time, length of event (see the partial, 1-day and 2-day formats).

- Secure a venue that is senior friendly: accessible, comfortable and well-lit.

- Plan food and drinks for breaks, considering potential allergies and health restrictions.

- Determine audio-visual needs, such as technology for PowerPoint presentations or a board and markers for a flip chart.

- Develop an agenda, ensuring its pace and breaks are suitable and flexible for seniors’ needs.

- Engage a facilitator, speaker and Elder (Elder for opening and closing prayer; a gift is usually provided for Elders).

- Determine the cost of the meeting and how it will be financed (grants, donations).

- Create a registration form (if needed). Decide if you will need sign-in sheets.

- Invite guests (see Appendix D) or advertise the event.

- Assign volunteers to support seniors with disabilities. You may need to arrange transportation for some seniors. You may also need to help the facilitator by taking notes and arranging for translation.

- Prepare signage suitable for different Indigenous languages if needed; most will likely know English or have translators available.

- Prepare any handouts (such as the agenda, or Appendix F Handouts/Fact sheets in Supplement).

- Print an event feedback form (see Appendix F, Toolkit Volume 2).

- Create a facilitator event report template (see Appendix G, Toolkit Volume 2).

Appendix B: Sample invitation

Hello and welcome.

You are invited to share your ideas about helping to reduce the social isolation of Indigenous seniors in your community. Indigenous seniors play a vital role in the cultural continuity and life knowledge of their families and communities, but they also face many social and economic challenges, which can place them at risk of social isolation.

Social isolation is a growing issue among all seniors, with serious consequences for individuals and society. Finding ways to help is a shared responsibility that is best addressed by different sectors working together, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals, the private sector, non-profits, academia, different levels of government, and Indigenous agencies and leaders.

We [description] are hosting an event to share ideas about how to address social isolation among Indigenous seniors in the community. The purpose of the event is to develop a shared understanding of the risks of social isolation and how to address them. We will look at socially innovative approaches to reducing social isolation.

You are invited to this event because of your involvement with [or concern about, or knowledge about] Indigenous seniors and Elders. Please come and share your ideas about how we can help prevent or reduce social isolation among Indigenous seniors in our community.

Time:

Date:

Location:

Cost: [free or $]

For more information, contact: [insert contact information]

Notes

- The greeting (“hello,” etc.) should reflect the Indigenous languages of the area.

- Ask people to RSVP by a certain date, especially if hosting a meal, and indicate whether meals or refreshments are included.

- You could ask invitees to identify a substitute if they are not able to attend.

- If there is a cost, provide instructions for how to pay.

- Location and parking details are helpful.

- Follow-up phone calls or home visits a few days before the event may be particularly helpful for Indigenous seniors.

Appendix C: Presentation slides

The following slides provide suggested content. Presenters should have sufficient knowledge of the issues to discuss the topics. These slides may be supplemented with additional content as appropriate for the community and the event’s participants.

Slide 1

Indigenous seniors and social isolation

- Indigenous seniors profile

- What is social isolation?

- Key risk factors

- Preventing social isolation

- Social innovation—Key principles

Slide 2

Indigenous seniors profile

- An estimated 6% of the 1.4 million Indigenous people in Canada are seniors (aged 65+ years)

- More than half live in towns and cities with their families and those living alone tend to be women. It is unclear how many reside in long-term care facilities

- They tend to be poorer, have more chronic health problems, older seniors are less fluent in English, and many lack social supports and face housing and food insecurities.

- Many seniors were affected by residential schools and the Sixties Scoop (intergenerational trauma).

- Lack of local medical and support services may continue to push more seniors into the towns and cities which has serious implications for finding solutions to prevent social isolation

Side 3

- What is social isolation?

- Low quantity of and quality of contact with others that is long-term

- It is different from loneliness which can happen periodically to everyone

- It affects health & wellbeing

- It can lead to early death

Slide 4

Key risk factors

- Living alone in unsafe community areas

- Older seniors become more vulnerable

- Senior caregivers without adequate help

- Poor health, chronic illnesses, mobility issues

- Social and cultural changes

Slide 5

Preventing social isolation

- Key protective factors for Indigenous seniors: individual and family supports; awareness of and access to community/government programs and services.

- Cultural awareness, language needs and culturally respectful opportunities for Indigenous seniors to engage.

- Community social supports are important for both the seniors and their families

Slide 6

Social innovation-key principles

- Cultural awareness and respect for diversity

- Respectfully engage seniors, families and leaders

- Engage widely and broadly across all levels of community agencies, groups, governments

- Volunteer and other programs are vital, like transportation, translators, flexible and informal opportunities for participation (visiting/lunches/berry picking, crafts)

Appendix D: Case study

This section is adapted from the Social Isolation of Seniors - Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit.

XYZ is a small prairie town with a population of 1,500. It is within driving distance of a city that has a hospital and major social and recreation services. In XYZ and the surrounding area, a high proportion of the population are older seniors. There are also two First Nation reserves within a few hours’ drive. The town is slowly growing, with working families and recent immigrants moving in. XYZ has a small health centre, a small long-term care facility, a credit union, and array of small businesses and services.

In response to a survey conducted by the municipality, seniors identified numerous challenges. Those living out of town are physically distanced from the services available in XYZ, especially in the winter. Indigenous seniors on reserves do not feel comfortable coming to XYZ community events, and when they do, it is hard to get transportation. Most seniors want to age in their homes and communities, but costs and access to needed services are barriers. Many are facing higher risks of social isolation because of multiple health problems, mobility issues, caregiving responsibilities, and increased stresses related to daily life needs, like transportation and healthy food.

The municipality has organized an area-wide meeting to discuss issues relating to seniors. It has invited XYZ community agencies, local citizens, businesses and governments, including the province and First Nation leaders.

Questions for groups

Activity 1

The goal of this activity is to understand and reduce the risks of social isolation for Indigenous seniors.

- Think about the concerns of Indigenous seniors in XYZ area. What can be done to address some of them?

- What are the risk factors and how can they be minimized?

- How can protective factors like culture and language be supported?

- How can we use these to prioritize initiatives?

Activity 2

The goal of this activity is to apply the principles of social innovation to a case example. This is good for groups who are aware of social isolation and have experience working with Indigenous seniors.

- How can the principles of social innovation lead to solutions to the problems faced by seniors in the XYZ area?

- How could different people, agencies, businesses and governments in the area work together to support a solution to meet seniors’ needs?

- How can XYZ strengthen its assets, programs, funding and expertise to address the social isolation of Indigenous seniors? What cross-sector partnerships are possible?

- Within the local community, are there best practices or lessons learned from other groups and initiatives that could be applied at XYZ?

- Is there a new partnership approach that could be used to better respond to the concerns?

- Are there changing attitudes or developing initiatives to tap into (such as the Age-Friendly Community movement or Indigenous initiatives)? (Social Isolation of Seniors - Volume II: Ideas exchange event toolkit.)

- Could new technologies help create solutions for Indigenous seniors? If so, what measures can we take to support them?

Appendix E: Handouts - Additional considerations for Indigenous seniors

This handout provides additional information about the circumstances and characteristics to consider in addressing social isolation among Indigenous seniors. These could be provided to participants to stimulate discussion or to help keep discussions focused on the challenges faced by Indigenous seniors.

Risk factors

Social isolation happens when a senior’s social participation or social contact drops. Seniors risk becoming socially isolated when they go through life transitions or when they live in social and environmental conditions associated with social isolation.

Risk factors for all seniors

Demographic

- Living alone

- Being older than 80 years

- Being a caregiverFootnote 63

Health

- Poor physical or mental health

- Mobility issues

- Frailty

- Victim of older adult abuse, including neglect and financial abuseFootnote 64

Social and cultural

- Losing a spouse

- Lack of friends or family

- Unsupportive family systems

- Lack of access to transportation

- Loss of independence

- Lack of communication access, such as no telephone or cell phone

- Discrimination

Economic

- Inability to afford essentials (healthy foods, medication)

- PovertyFootnote 65

Additional risk factors for Indigenous seniors

- Racism

- Living in communities with high crime ratesFootnote 66

- Residential school trauma

- Past institutional experience

- Living in overcrowded housing

- Moving into the city or town from a rural reserve for access to health and community services

- Insufficient or remote family supports

- Cultural differences

- Language differences

- Political/jurisdictional isolation

- Lack of access to services

- Inaccessible buildings and community infrastructure (for example, ramps, sloped sidewalks)

- Lack of culturally appropriate activities and/or ability to access activities

Protecting against social isolation

While many factors can increase seniors’ risk of becoming socially isolated, there are others that can help ensure they remain socially engaged. A study of Indigenous language and culture has found that it protects vulnerable communities. Below are factors that can be helpful in maintaining social inclusion for seniors and Indigenous seniors.

Protective factors for all seniors

- Being in good physical and mental health

- Having sufficient income and safe housing

- Feeling and being safe in neighbourhood

- Having good literacy and communication skills

- Having satisfying relationships

- Having a supportive network

- Feeling valued

- Being able to access local services offered by community organizations, government programs and services, and health agencies

- Feeling productive in society

- Having access to transportation

- Having higher education

Additional protective factors for Indigenous seniors

- Participating in ceremonies

- Having social support (individual, family and community) that provides practical help, positive interaction, emotional support, and friendship

- Belonging to a community that promotes respect for the Indigenous way of life and cultural values as social norms

- Belonging to a community that promotes respect for Indigenous seniors for their wisdom and knowledge

- Belonging to a community that appreciates Indigenous resilience and the diverse narratives of Indigenous experience

- Having access to social events that respect Elders and experiencing positive interactions that make them feel comfortable

- Having translators when needed

- Having social contact in the form of phone calls, visits, excursions and/or other interactions

- Having access to culturally sensitive health care services within the community

Principles of social innovation

Social innovation combines the resources and ideas of community organizations, governments and public institutions, researchers, seniors and businesses to make new plans and tools that address social problems in creative ways. Experience in Indigenous communities has identified additional best practices to help prevent and address the social isolation of Indigenous seniors.

Core principles of social innovation

- Committing to work together to address the needs of the community

- Welcoming new partners

- Adjusting new activities, services and programs to new audiences

- Drawing on expertise and resources from partners

- Being open to taking risks to address issues

- Relating solutions to changing attitudes and behaviours and to structural institutional and systemic change

- Adjusting new technologies

Additional core principles of social innovation for Indigenous seniors

- Connecting solutions to changing attitudes and systemic changes

- Respecting the diversity of Indigenous seniors

- Identifying the needs of Indigenous seniors through engagement opportunities

- Engaging all levels of government (federal, provincial/territorial, municipal, Chief and Council, Indigenous, First Nation administration) and community agencies

- Recognizing the importance of volunteers and volunteer programs that provide services, for example, transportation, translation

- Engaging and working with Indigenous community organizations

- Working on programs and services that target the needs of Indigenous seniors

Appendix F: Protocol for Indigenous elders

Elders play an important and respected role in Indigenous cultures. They are the knowledge keepers and are held in high regard. Elders are leaders, teachers, role models, and mentors in their respective communities and often provide the same functions as advisors, professors and doctors.

Here are some guidelines on inviting an Elder, caring for them respectfully, and offering honoraria:

How to make a request

- Invitation in person (preferred): For First Nations or Métis Elders, it is customary to offer tobacco. Tobacco is one of the four sacred medicines, and is offered when making a request. The offering can be in the form of a tobacco pouch or tobacco tie (loose tobacco wrapped in a small cloth). (Inuit Elders do not expect tobacco offerings, because it is not part of their traditional customs. A small gift may be offered in the same spirit with which one would make a request to a First Nations or Métis Elder.) Place the tobacco/gift in front of you and state your request. The Elder indicates acceptance of your request by taking the gift in their hands. The exchange of tobacco/gift is similar to a contract or agreement between two parties. Ask the Elder if there is anything they need for the event.

- Invitation by phone or email: It is preferable to make requests to Elders in person, as tobacco can then be offered. However, many Elders will also accept requests by phone (or by email if you cannot reach them by any other means). If you are making a request to an Elder by phone or email, let the Elder know you will have tobacco or a gift to offer when you see them, then make your request.