Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015: Chapter III - Impacts and Effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs – Part II of the Employment Insurance Act)

Introduction

Activities delivered under Part II of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act help unemployed individuals in Canada prepare for, find and maintain suitable employment. Under the umbrella of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), these activities include similar programs delivered by provinces and territories under Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), as well as the Government of Canada's pan-Canadian programming and functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

This chapter presents EBSM program results achieved under Part II of the EI Act during the 2014/2015 reporting period. A national overview of EBSM-similar programming, delivered under the LMDAs and by Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS) agreement holders, is provided in section I, entitled "National Overview". Provincial and territorial employment programming activities are presented in section II, "Provincial and Territorial Summaries", with a description of each jurisdiction's labour market and employment priorities. Section III presents the results of an analysis of the incremental impacts of LMDAs for the "long-tenured workers" EI claimant type and a cost-benefit analysis of all LMDAs. Finally, section IV discusses the results of Employment and Social Development Canada's (ESDC's) delivery of pan-Canadian activities, and the administration of certain NES functions.

Notes to Readers

- The data used to analyze EBSM activities were collected from provinces, territories and ASETS agreement holders. Accordingly, the data were processed through several systems using a variety of sources. Governments are continuing to improve data quality and collection to ensure accurate, reliable and consistent information. While all data sets are verified before publication, systems and operational changes may affect the comparability of data from year-to-year. These instances are noted, where applicable.

- Throughout this chapter, references to average levels of activity, and highs and lows generally use the 10-year period from 2004/05 to 2014/2015 as a frame of reference.

- Statistics Canada's Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the source of labour market data reported herein. Data for Canada and the provinces are fiscal-year averages, calculated using seasonally unadjusted data, while monthly references are seasonally adjusted. Data for the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are calculated using unadjusted three-month moving average monthly data. In discussions of employment trends by industry, standard industry titles are taken from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

- Real GDP data and other non LFS macroeconomic indicators are from Statistics Canada's Economic accounts. Forecasts are based on published analysis from the Bank of Canada, the Conference Board of Canada, Canadian Banks, OECD and Statistics Canada, as well as on internal analysis, using information available as of February 2016.

1. National Overview

1.1 Context

1.1.1 Economic Conditions

Canada's real growth domestic product (GDP) rose moderately by 2.4% in 2014, slightly above the 2.1% growth recorded in 2013. At the subnational level, the strongest real GDP growth in 2014 was recorded in the Northwest Territories (+5.9%) followed by Alberta (+4.5%), Nunavut (+3.6%), British Columbia (+2.6%) and Ontario (+2.5%). Growth rates in Manitoba (+2%), Saskatchewan (+1.6%), Prince Edward Island (+1.5%), Quebec (+1.4%), and Nova Scotia (0.7%) were below the national average. New Brunswick (-0.3%), Yukon (-0.8%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (-2.3%) all experienced negative growth.

The Canadian economy experienced a mild recession through the first half of 2015. For the whole year, Canada's real GDP growth will likely be around 1.2%. The sharp decline in crude oil prices has weighed on the Canadian economy. Since peaking at $107USD per barrel in June 2014, oil prices have experienced a steady decline, averaging under $50 USD per barrel in the first quarter 2015 Footnote 1 . This drop has had an impact on Canada's energy sector, as high-cost oil producers responded by cancelling capital projects, decreasing drilling activities and laying off workers.

In 2014, Canada's economy was driven mainly by an increase in household final consumption expenditure (+2.8%), as outlays on goods (+3.4%) and services (+2.2%) both advanced. Spending on durable (+5.3%), semi-durable (+3.6%) and non-durable (+2.4%) goods all increased. Household disposable income (in current dollars) grew by 3.4%, the slowest pace in five years. As a result, the household saving rate declined from 5.2% in 2013 to 4.0% in 2014.

In 2014, exports rose by 5.4% after increasing 2.0% in the previous year. Exports of goods rose by 6.0%, while those of services were 2.3% higher. Imports grew 1.7%, following a 1.3% increase the previous year. The imports of goods increased by 2.4% and were partially offset by a 1.3% decline in imports of services.

Governments' gross fixed capital formation decreased (-2.3%) for the fourth consecutive year, amid fiscal constraint among many of the provincial and territorial governments throughout 2014/2015.

Mining and oil and gas extraction, as well as manufacturing, were the main contributors to overall growth in goods production (+2.4%). Construction and utilities also grew. The gains were partly offset by a decrease in the agriculture and forestry sectors, pulled down by falling crop production following strong growth in 2013. Wholesale and retail trade; finance and insurance; the public sector (education, health and public administration combined); transportation and warehousing services; professional services; as well as accommodation and food services, contributed to the increase in the service-producing sector (+2.4%).

In 2014, Canada's business productivity grew by 2.5%, following a gain of 1.2% in the previous year. Business productivity increased in every province and territory except Yukon, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick. Growth in business productivity was above the national average in Nunavut (10%) and British Columbia (3%), while Alberta (2.6%), Quebec (2.5%), Ontario (2.4%) and Saskatchewan (2.3%) were similar to the national growth rate. Business productivity remained unchanged in New Brunswick, while Yukon and Newfoundland and Labrador declined by -10% and -1.5%, respectively.

Compared internationally, Canada's annualized real GDP growth is forecasted at 2.4% for 2014, which is above the OECD average of 1.8%. Among the G-7 countries, Canada's 2014 forecast ranks second—along with that of the United States—only behind the United Kingdom's. For 2015, Canada's ranking is expected to slip, with a real GDP growth rate of just over 1%. The United Kingdom, the United States and Germany are projected to experience stronger growth. Footnote 2 Lower oil prices have had a net negative impact on Canada's economy, while creating large regional differences. According to the Conference Board of Canada, Canada's oil industry is expected to post a pre-tax loss of $2.1 billion in 2015, compared to a profit of close to $6 billion the previous year. Footnote 3

1.1.2 Labour Market Context

Overall, labour market conditions improved in Canada for a fifth consecutive year, with employment levels reaching an all-time high of 17.8 million, and a net gain of 103,000 jobs recorded in 2014/2015. This represented a 0.6% year-over-year increase. In addition, both full-time and part-time employment jobs expanded, by 0.4% and 1.2%, respectively. The work force expanded by 1.1% to a total of 29.06 million, while the labour force grew at a rate of 0.4% (19.1 million).

1.1.3 Client Trends

Provinces and territories supported a lower number of LMDA clients (-3.1%) accessing EBSM interventions in 2014/2015. All three client type counts declined, as EI active claimants dropped by 2.7%, former clients edged down by 6.0% and non-insured clients decreased by 2.7%. The share of active clients (49.3%) edged down by 0.2 percentage points year-over-year, while former clients (12.5%) dropped by 0.4 percentage points. The share of non-insured clients increased by 0.2 percentage points to a total of 38.2%, representing an all-time high, as provinces and territories increasingly provided Employment Assistance Services (Support Measures) to non-insured clients.

1.1.4 Trends in Program Delivery

In 2014/2015, the number of EBSM interventions delivered by provinces, territories and Indigenous organizations decreased by 2.8%. Both Employment Benefits and Support Measures were down year-over-year, -4.8% and -2.7% respectively. Support Measures, which represented 86.8% of all interventions, increased in their share by 0.3 percentage points as clients relied more heavily on short-term interventions for quicker returns to work in a strengthening labour market.

Canada: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Active & Former |

Non-Insured | Pan-Canadian1 |

|---|---|---|

431,794

|

257,665

|

15,378

|

| Active | Former | Non-Insured |

49.3%

|

13.3%

|

37.4%

|

| Youth (15-24)2 |

Core Age (25-54) |

Older Workers (55+) |

| 19.4% - | 68.1%

|

12.5%

|

| 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 142,389 | 4.8%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 936,144 | 2.7%

|

| Pan-Canadian | 28,217 | 7.0%

|

| 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 13.2% | 0.2

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 86.6% | 0.2

|

| 2014/2015 ($ Million) |

Year-over-Year Change |

|

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $1,149.2 | 2.4%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | $629.9 | 6.1%

|

| LMPs and R&I | $160.7 | 1.2%

|

| Pan-Canadian | $116.7 | 0.2%

|

| Total Expenditures3 | $2,056.6 |

0.5%

|

| Indicator | Total | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Active Claimants Served | 339,795 | 2.6%

|

| Returns to Employment (active and former clients) |

173,593 | 1.0%

|

| Unpaid Benefits ($ Million) | $1,121.98 | 5.7%

|

- 1 EI Part II Pan-Canadian services to individuals are through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy.

- 2 Age distribution does not equal 100%, as the "unknown" category is not reported here. Date of birth is not collected for clients in SD-Apprentices and Group Services.

- 3 Totals may not add up exactly due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

1.2 Main Results

Provinces, territories and Indigenous organizations helped a total of 689,459 clients prepare for, obtain and maintain employment during the 2014/2015 reporting period. This represented a 3.0% drop year over year. Canada's unemployed accessed a declining number (1,106,750) of EBSM interventions (-2.8% year over year). Accordingly, the ratio of the number of interventions per client increased slightly to 1.61, compared with 1.60 in the previous year. The number of EI active and former claimants returning to employment after participation in EBSM-similar programming rose to 173,593 (+1.0%), while unpaid benefits from the EI Operating Account increased significantly, reaching $1,121,980 in 2014/2015 (+5.7%).

1.2.1 Canada's Labour Market

Key Labour Market Indicators

In 2014/2015, Canada's labour market recorded soft but continued growth. Employment edged up by 0.6% adding 103,000 jobs, compared to 1.2% growth the previous year. Unemployment fell by 2.3% year over year (-30,600), bringing Canada's unemployment rate down to 6.9%. This was the first fiscal year since 2008/09 with an unemployment rate below 7%.

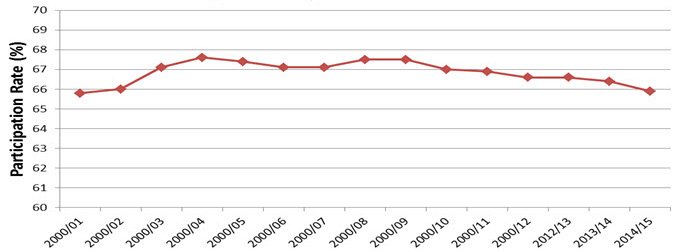

For a second consecutive year, the employment rate edged down in 2014/2015, dropping to 61.4%. As well, the labour market participation rate declined to 65.9%, a drop of 0.5 percentage points, the lowest rate since 2000/01. While the economy has continued to expand since the 2008-2009 recession, the downward trending participation rate will likely remain in place over the medium term as the baby-boomer generation enters retirement with fewer labour market entrants to replace them.

Show Data Table

| Year | Participation rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 2000/2001 | 65.8 |

| 2000/2002 | 66 |

| 2000/2003 | 67.1 |

| 2000/2004 | 67.6 |

| 2000/2005 | 67.4 |

| 2000/2006 | 67.1 |

| 2000/2007 | 67.1 |

| 2000/2008 | 67.5 |

| 2000/2009 | 67.5 |

| 2000/2010 | 67 |

| 2000/2011 | 66.9 |

| 2000/2012 | 66.6 |

| 2012/2013 | 66.4 |

| 2013/2014 | 65.9 |

| 2014/2015 | 66.5 |

Source: Labour Force Survey

In 2014/2015, employment gains were concentrated in the services-producing sector (+128,000), which more than offset the employment losses in the goods-producing sector (-25,000). All goods-producing industries recorded employment losses with the exception of construction, which experienced a growth of 3,900 net jobs. The manufacturing sector is often seen as the segment of the Canadian economy that benefits the most from the fall in oil prices through its weakening effect on the Canadian dollar. However, the export growth has been weaker than initially anticipated, holding back potential job gains. The services-producing sector was sustained by strong employment increases in: health care and social assistance (+42,400); accommodation and food services (+35,400); and, educational services (+30,200). Employment losses in the services-producing sector were observed in: other services (-12,200); information, culture and recreation (-4,700); and business, building, and other support services (-1,600).

Labour Market Tightness

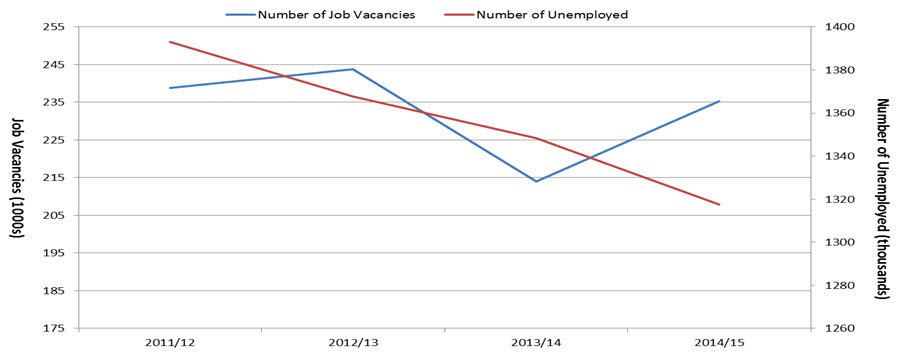

According to Statistics Canada's Business Payroll Survey (BPS)

Footnote 4

, Canadian businesses reported on average 235,300 job vacancies in 2014/2015, representing a 10% increase compared to the 214,000 average reported in 2013/14. In absolute terms, growth in the number of job vacancies was concentrated in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, which respectively registered increases of 14,200 (21.8%), 4,700 (11.6%) and 4,400 (14.7%). Job vacancies declined in Alberta (-2,800 or -5.8%) and Manitoba (-1,300 or -12.8%) and remained relatively constant in other provinces.

Over the same period, the number of unemployed persons across Canada was 1.317 million, compared to 1.348 million in 2013/14, a decrease of 2.3% year-to-year Footnote 5 . The largest drops in unemployed persons were recorded in Ontario (-23,800), British Columbia (-11,200) and Quebec (-2,800). Alberta and Newfoundland & Labrador saw the largest increase in the unemployed, with jumps of 9,500 and 1,000 respectively.

Labour market tightness is often assessed using the unemployment-to-job vacancies (U/V) ratio Footnote 6 . In 2014/2015, 5.6 individuals sought employment for every job vacancy, compared to 6.3 a year earlier. The decrease in the U/V ratio (number of unemployed people for every vacant position) suggests employers face more challenges in filling job vacancies, as the number of unemployed workers shrinks, or they are increasingly unable to find the required skills for their job openings.

| 2013/14 | 2014/2015 | Year-To-Year Change |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Unemployed | 1.348 Million | 1.317 Million | -2.3% |

| Number of Job Vacancies | 214,000 | 235,300 | +10% |

| Unemployment-to-Vacancy Ratio | 6.3 | 5.6 | -11.1% |

At the subnational level, the largest drop in the U/V ratio was observed in Prince Edward Island, sliding from 17.3 to 8.8 year-over-year. Moderate U/V ratio drops were also registered in Nova Scotia (from 10 to 8.4), Ontario (from 8.5 to 6.7) and British Columbia (from 5.3 to 4.3), pointing to a tightening labour market year-over-year. New Brunswick, Manitoba and Alberta recorded modest increases (0.3, 0.5 and 0.5, respectively) in their U/V ratios, suggesting greater slack in the labour market compared to 2013/14. Nonetheless, Alberta and Manitoba continued to register among the lowest U/V ratios in Canada (2.7 and 4.1, respectively) pointing to tight labour markets.

Since 2011/12, the national U/V ratio decreased modestly, from 5.8 to 5.6 as the number of unemployed persons has been on a steady decline (-5.4%). This suggests an overall tightening of the Canadian labour market over this period. Footnote 7 The trend is expected to continue in the coming years as large cohorts of workers begin to retire, with fewer younger workers to replace them.

Show Data Table

| 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Vacancies (thousands) | 238.8 | 243.85 | 214 | 235.325 |

| Number of Unemployed (thousands) | 1392.93 | 1367.78 | 1348.35 | 1317.48 |

Share of Job Vacancies by Industry

Of the annual average of 235,300 BPS job vacancies reported in 2014/2015, the following industries showed the most vacancies:

- health care and social assistance (39,800; 16.9%);

- accommodation and food services (31,100; 13.2%);

- retail trade (26,700; 11.3%);

- manufacturing (17,000; 7.2%); and

- construction (16,000, 6.8%).

Compared against their employment growth Footnote 8 in 2014/2015, these industries were among the strongest to record employment gains: health care and social assistance employment grew by 2.0%; accommodation and food services increased by 1.9%; retail trade was up 0.7%, and construction employment increased by 3.5%. Manufacturing employment dropped by 0.3%, despite being ranked as the 4th highest Canadian industry in terms of job vacancies over the same period.

Across all industries, finance and insurance (1.6), as well as health care and social assistance (1.3), posted the lowest U/V ratios. This suggests tighter labour market conditions in those industries than all others. Conversely, the highest U/V ratios were recorded in arts, entertainment and recreation (8.6), mining, quarrying, and oil and gas (7.6) and educational services (7.6). The high ratio points to more unemployed persons relative to job vacancies in those industries across Canada.

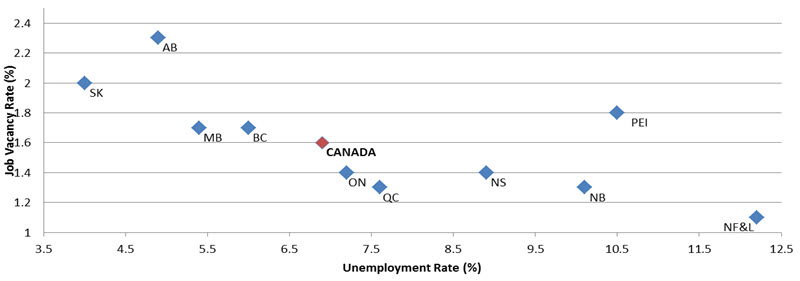

Job vacancy rates and unemployment rates by province

Among all provinces, Western Canada registered the highest job vacancy rates (i.e., the share of jobs that are unfilled out of all payroll jobs available) and lowest unemployment rates. Despite the recent downturn in Alberta's and Saskatchewan's resource sector, the two provinces posted the highest job vacancy rates and lowest unemployment rates as both goods and service-producing sectors of the two economies recorded employment growth. Manitoba's growth in key sectors like manufacturing, agriculture and construction had a positive impact on the labour market. The province registered an unemployment rate of 5.4%, which is well below the Canadian average. In Quebec and Ontario, slow growth in the provinces' trade sectors triggered some slack in the labour markets. Atlantic Canada's relatively high unemployment rates and low job vacancy rates suggested a significant mismatch between available job seekers and job vacancies.

Show Data Table

| Area | Job Vacancy Rate (%) | Unemployment Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1.6 | 6.9 | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.1 | 12.2 | 11.6 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.8 | 10.5 | 11.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 1.4 | 8.9 | 9 |

| New Brunswick | 1.3 | 10.1 | 10 |

| Quebec | 1.3 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| Ontario | 1.4 | 7.2 | 7.5 |

| Manitoba | 1.7 | 5.4 | 5.5 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 4 | 4.2 |

| Alberta | 2.3 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

| British Columbia | 1.7 | 6 | 6.5 |

Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, and Business and Payroll Survey.

Skills in Demand – Employment Growth by Skill Type

Footnote 9

In 2014/2015, employment in Canada grew by 103,000, to a total of 17.8 million; an increase of 0.6% compared to the previous year. By skill type, the largest proportional employment growth occurred in:

- Sales and Service Occupations (+59,300 or +1.4%)

- Natural and Applied Sciences and related occupations (+47,400 or +3.6%)

- Education, Law and Social, Community and Government Services (+23,600 or 1.2%)

- Art, Culture, Recreation and Sport (+13,300 or +2.5%)

- Health Occupations (+10,000 or +0.8%).

Employment declines were recorded in: management (-65,300 or -4.0%) and natural resources, agriculture, and related production occupations (-3,200 or -0.8%).

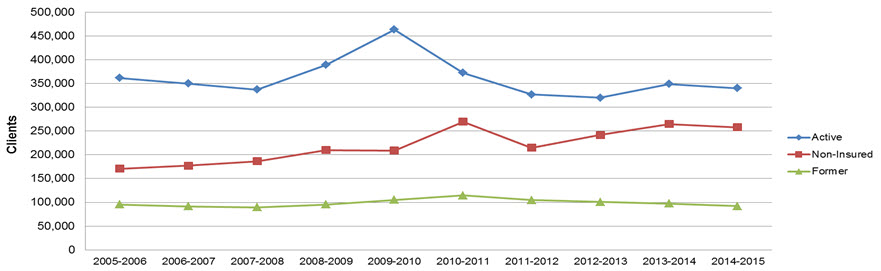

1.3 Client Profile and Participation

The number of EBSM clients decreased by 3.0% in 2014/2015, reaching a total of 689,459 as a result of improving labour market conditions in the Canadian economy. All three client type counts dropped: active claimants (-2.6%), former (-5.6%) and non-insured (-2.7%).

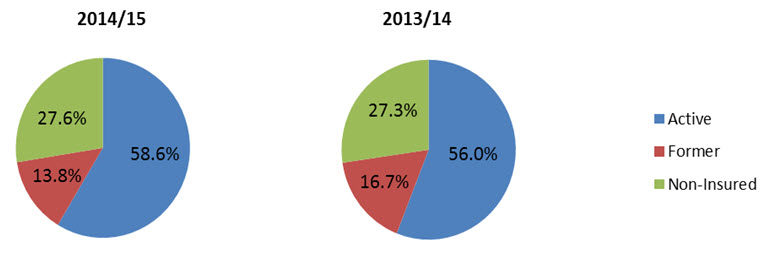

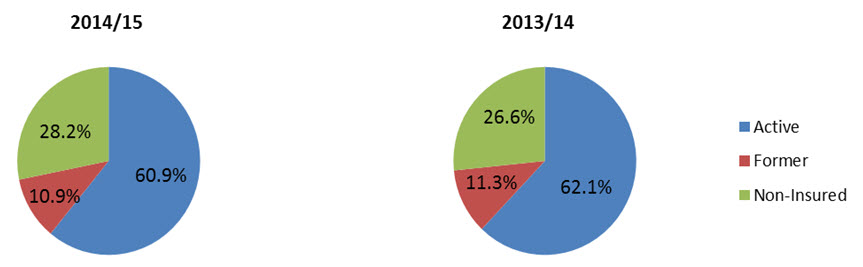

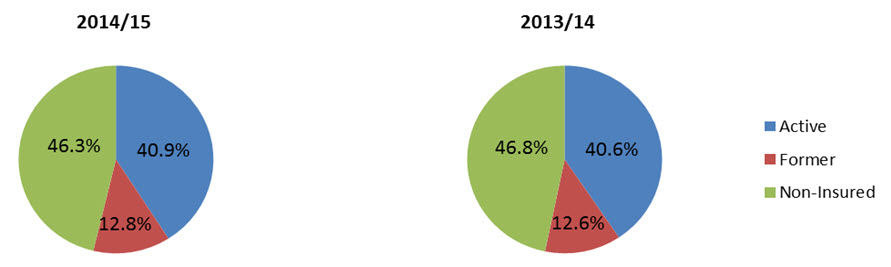

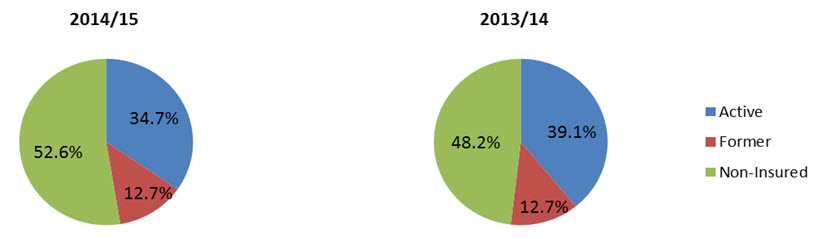

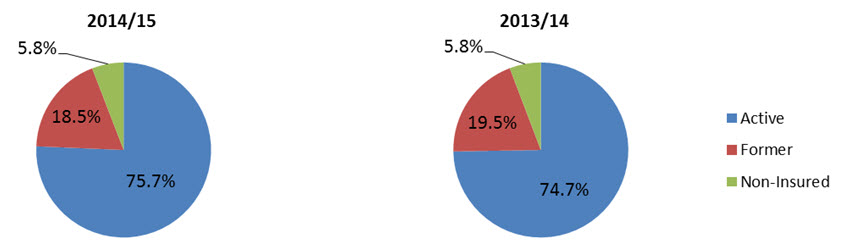

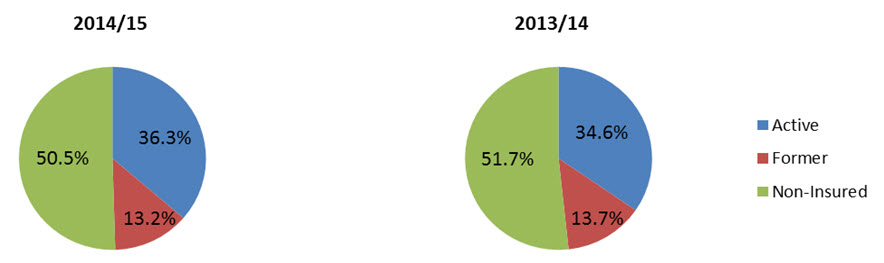

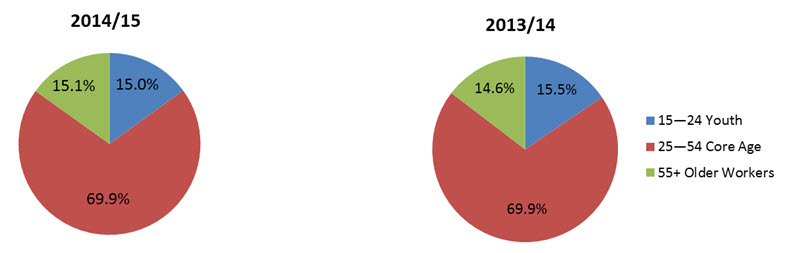

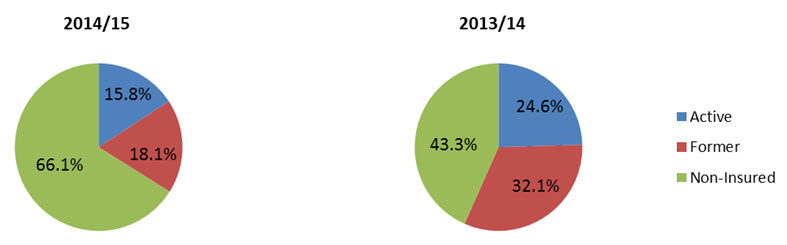

1.3.1 Client Types

Three client types can access EBSMs: active claimants, former claimants and non-insured clients. In 2014/2015, the distribution of client types continued to reveal an upward trend from the non-insured clients among provinces and territories. Their share of all clients increased to an all-time high of 38.2% (increase of 0.2 percentage points), while active clients increased by 0.2 percentage points to a total of 49.3% and former clients saw their share decrease to 12.5% from 12.9% in the previous year.

Since 2005/06, the number of non-insured clients has increased by 50.9%, while those of active and former claimants have declined by 6.1% and 3.3%, respectively. The rising numbers in non-insured clients can be attributed to the increasing reliance of provinces and territories on using Support Measures for quicker, short-term interventions to support the unemployed in finding jobs when they may otherwise face challenges in searching for employment on their own.

Show Data Table

| Clients | 2005/2006 | 2006/2007 | 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Clients | 361,490 | 349,865 | 337,148 | 388,714 | 463,158 | 372,340 | 326,892 | 319,904 | 348,909 | 339,795 |

| Non-Insured Clients | 170,714 | 176,879 | 186,159 | 209,871 | 209,020 | 269,350 | 214,587 | 241,834 | 264,716 | 257,665 |

| Former Clients | 95,499 | 91,458 | 89,315 | 95,468 | 104,972 | 114,356 | 104,816 | 100,522 | 97,417 | 91,999 |

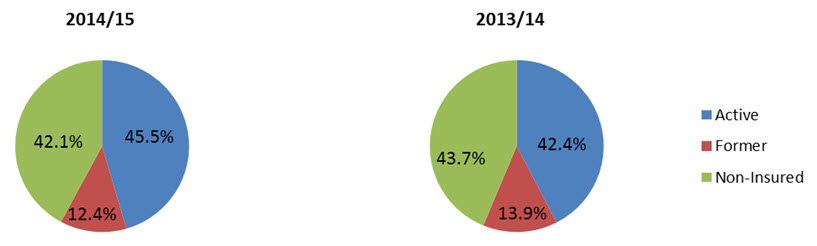

Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested assistance under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Typically, they have stronger recent labour force attachment and tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to the labour market. Active claimants who are job ready often seek out short-term interventions under EI Part II to find their next employment opportunity. Others require longer-term Employment Benefits to upgrade their skills, establish certification or refine their job search strategies.

In total, the number of active claimants served in Canada declined to 339,795, a year-over-year decrease of 2.6%. Their share of all clients increased slightly (+0.2 percentage points) to 49.3% year over year. The proportion of active claimants returning to work after participating in an EBSM-similar programming was 45.8%, compared to 43.6% in 2013/14.

Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the past three years, or who began a parental or maternity claim in the preceding five years. They are no longer eligible for EI Part I; however, they remain eligible for EI Part II under certain criteria. Footnote 10 Former claimants do not receive income support under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act while they complete an Employment Benefit intervention; however, they may receive Part II support while completing their return-to-work action plan.

During the 2014/2015 reporting period, the number of former claimants fell to 91,999 (-5.6%) year over year. In addition, their share of all EBSM clients declined to 12.5% (-0.4 percentage points). The number of former claimants returning to work decreased moderately (-3.0%), to a total of 22,424, which represents 24.4% of the 91,999 former claimants served.

Non-insured clients are unemployed individuals who are neither active nor former EI claimants and usually have little substantive or recent labour force attachment. They include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EI Part II, they may access interventions similar to EAS.

In 2014/2015, the numbers of non-insured clients dropped by 2.7%, to reach 257,665. However, their share among all client types increased to 37.4% (+0.2 percentage points). Since the 2004/05 reporting period, the share of non-insured clients has jumped by 13.2 percentage points, whereas the other two client types witnessed their share of total clients decline over the same time. Overall, 41,954 non-insured clients returned to work in 2014/2015 following their EBSM participation, a 6.5% increase from the previous year. Footnote 11

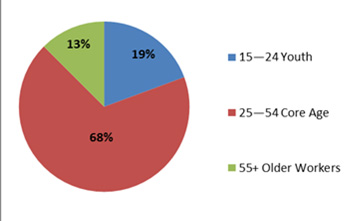

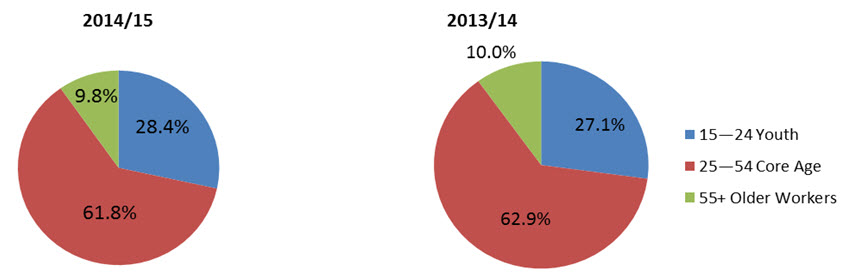

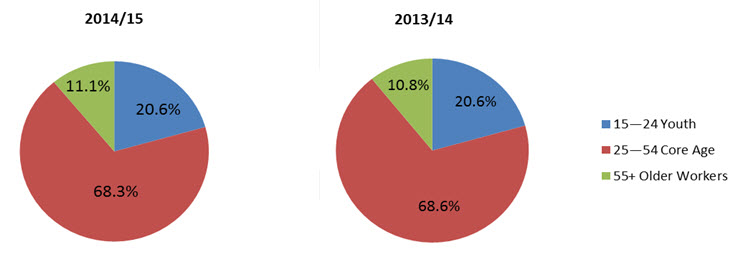

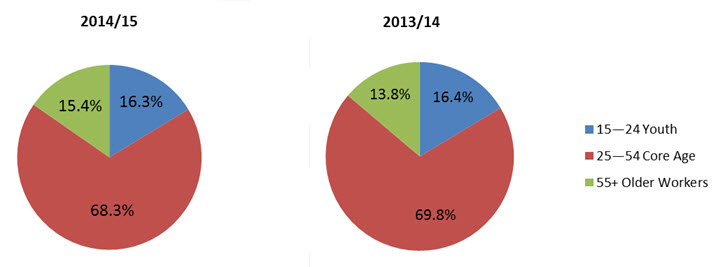

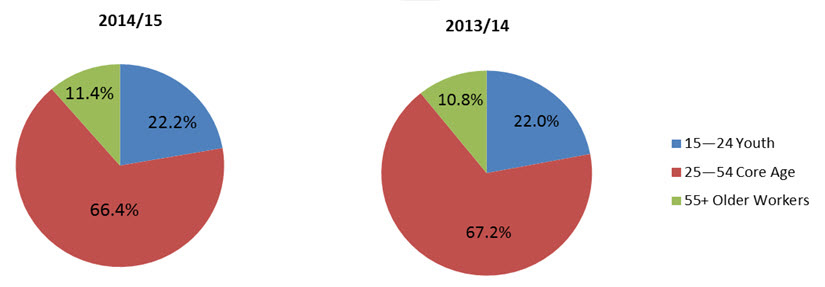

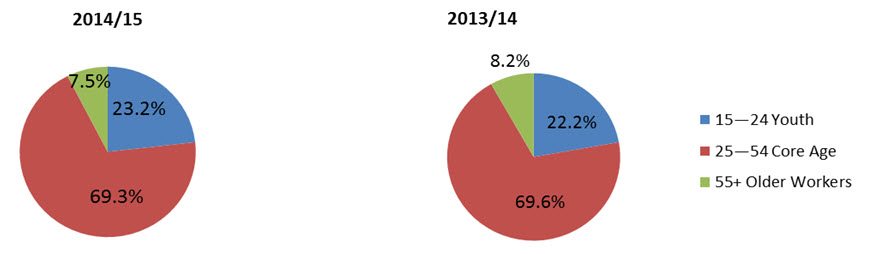

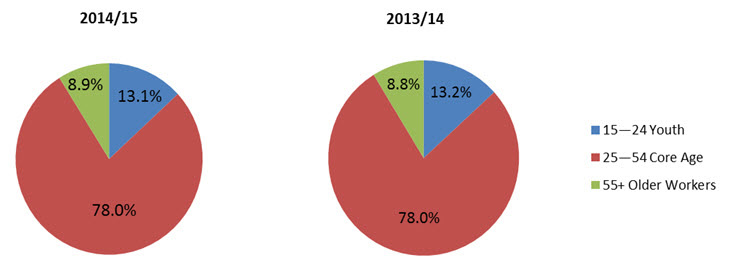

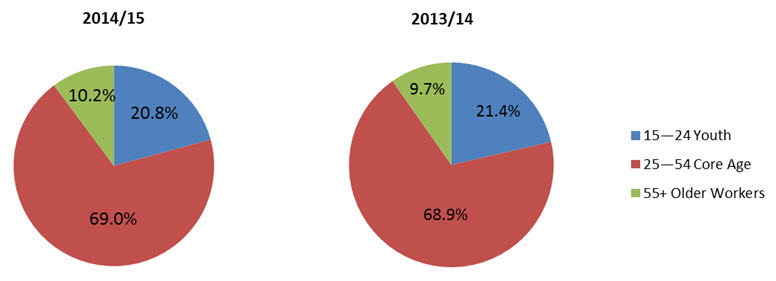

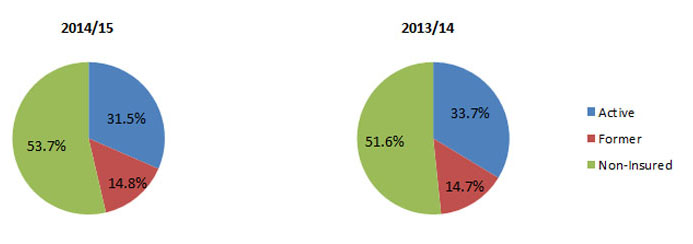

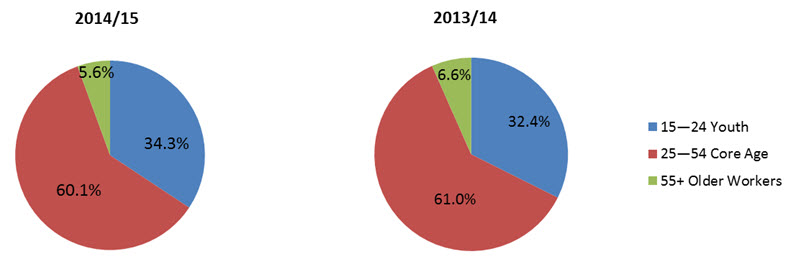

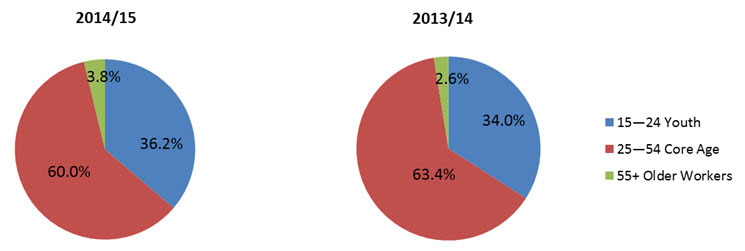

1.3.2 Age Distribution Footnote 12

Consistent with the growth of Canada's senior population, the older workers category (55+ years) was the only age group to experience growth in EBSM usage. This category increased by 5% with 73,170 clients served. Its share of the total age distribution increased by 0.9 percentage points, reaching 12.5%. In the last decade, older workers have consistently increased their share among all EBSM clients, reflecting greater use of active employment programs to improve their employability. Older workers' participation in the labour market reflects these trends; a cohort that now represents 35% of Canada's labour population. In 2014/2015, the labour population of older workers surpassed 10 million, on the strength of rapid growth in the last 10 years that added 1.5 million older workers into the workforce. This represents a 66% growth in this age group, which is significantly higher than any other age group. Consistent with these trends, older workers are increasingly reliant on employment supports, consistent with their growing share of Canada's labour force.

Show Data Table

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 15–24 Youth | 113,492 | 19.4% |

| 25–54 Core Age | 399,428 | 68.1% |

| 55+ Older Workers | 73,170 | 12.5% |

| Unknown | 130 | 0.0% |

| Total | 586,220 | 100.0% |

In 2014/2015, the labour population of older workers surpassed 10 million, on the strength of rapid growth in the last 10 years that added 1.5 million older workers into the workforce. This represents a 66% growth in this age group, which is significantly higher than any other age group. Consistent with these trends, older workers are increasingly reliant on employment supports, consistent with their growing share of Canada's labour force.

The total number for the core-aged workers (25-54 years old) dropped by 3.7% year over year to 399,428. The share of the core-aged workers, as a proportion of all age groups, decreased by 0.9 percentage points to 68.1% in 2014/2015. Among core-aged workers, all the subgroups experienced drops with the largest declines among the 50-54 year olds (-4,462 or -7.1%). This trend among core-aged workers is consistent with labour market indicators: the total number of the unemployed among the core-aged workers declined by 20,000 (-2.7%) year over year. As well, the group's unemployment rate (5.7% in 2014/2015) has also continued on a downward trend since the recent high of 7.2% in 2009/10.

Following two years of growth, youth (15-24 year olds) participation decreased by 3,359 or -2.9% year-over-year, for a total of 113,492 youth clients. Its relative share remained unchanged at 19.4% year-over-year. Although youth continue to face struggles in the labour market, their employment prospects are beginning to improve. In 2014/2015, the youth unemployment rate dropped to 13.3%. This is a general downward trend observed in the last five years, since the youth unemployment rate hit a generational high of 15.6% in 2009/10. Other indicators of improved conditions for youth in 2014/2015 include employment being up by 14,400 year-over-year and unemployment being down by 8,000 in the same period. The Youth employment rate and participation rate are up for the second straight year, reaching 55.7% and 64.3%, respectively.

1.3.3 Designated Groups Footnote 13

ESDC collects information on the EBSM participation of women, Indigenous people, members of visible minorities and persons with a disability in support of employment equity principles.

- Women participated in a total of 471,765 EBSM interventions in 2014/2015, a 2.9% decrease year over year. Women represented 44.1% of all participants, slightly lower than their share in 2013/14. Similar to the previous year, the vast majority of women (92.1%) accessed EAS interventions, while their male counterparts had a lower rate of EAS participation (81.8%). This trend is explained by the lower participation of women in the Skills Development Apprentice program, and by the fact that women are more likely to work in part-time occupations, which results in lower EI eligibility rates and, therefore, less access to Employment Benefits. Overall, 47.7% of female EBSM participants were non-insured this year, compared with 37.4% of male EBSM participants.

- A total of 104,063 EBSM participants self-identified as persons with a disability. The share of persons with a disability increased 0.6 percentage points to 9.7%. Non-insured clients represented 57% of this client segment, a slight increase of 0.1 percentage points, year over year.

- Indigenous people participated in 79,687 EBSM interventions. This represented 5.1% more than the previous year. Indigenous people participated in 7.5% of all EBSM interventions delivered in 2014/2015, including programming delivered through ASETS. A total of 38.3% of Indigenous clients participated as non-insured clients. As a share of participation in all interventions delivered to Indigenous clients, Employment Benefits increased from 3.8% to 3.9% year over year.

- Members of visible minority groups participated in 42,788 interventions, a significant drop of 23.1% over year. Corresponding with this decline, visible minorities' share of total EBSM participants dropped to 4%, a 1.1 percentage point slide year-over-year. It is worth noting that representation rates may be influenced by changes in self-identification behaviour and recent demographic trends.

1.3.4 Official Languages

ESDC furthers the commitment of the Government of Canada to foster the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society by ensuring that labour market programs and services are delivered in both official languages. In this context, all LMDAs contain commitments by provinces and territories to have programs and services delivered in both official languages where there is sufficient demand.

LMDA programming continues to evolve, with provinces and territories adapting program design and service delivery to meet local needs. ESDC is working with provinces and territories to improve the capture of official languages related data, in order to better assess how official languages requirements are being met.

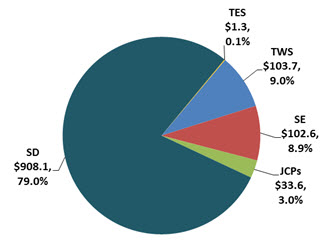

1.4 Interventions: Employment Benefits

Employment Benefits are available only to insured clients (active and former claimants). Historically, Employment Benefits have consisted of longer-term interventions focused on providing skills or work experience required to regain employment. Under LMDAs, provinces and territories provide employment benefits similar to the following six benefits types: Skills Development-Regular (SD-R); Skills Development-Apprentices (SD-A); Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS); Self-Employment (SE); Job Creation Partnerships (JCPs); and Targeted Earnings Supplements (TES).

Show Data Table

| $ | % | |

|---|---|---|

| TWS | 103,671 | 9.0% |

| SE | 102,550 | 8.9% |

| JCPs | 33,599 | 2.9% |

| SD | 908,122 | 79.0% |

| TES | 1,302 | 0.1% |

| Total | 1,149,244 | 100.0% |

Total Employment Benefits interventions declined for a fourth consecutive year, reaching 142,389. In addition, Employment Benefits interventions lasted an average of 2 days longer, a 1.9% increase compared with the previous reporting period. At 13.2% of all EBSMs, the share of Employment Benefits continues to decline year over year, reflecting a focus on shorter-term interventions to help unemployed people return to work quickly. Employment Benefits expenditures totalled $1.15 billion, a decline of 2.4% from the previous year.

1.4.1 Skills Development

Skills Development (SD) is the most common Employment Benefit delivered under LMDAs. This benefit helps insured clients cover the cost of gaining the new skills they often need when facing a career change. In 2014/2015, the use of SD-Regular (SD-R) interventions fell significantly by 10.1% year over year, to 49,091. Also, the share of SD-R of all benefits trended downwards for a fifth consecutive year, dropping to 34.5%. In comparison, the number of SD-Apprentice (SD-A) interventions increased by 4.1%, to 68,437. Corresponding with this increase, the share of SD-A edged up to 48.1%, due to steady demand for skilled trades across Canada. SD expenditures saw a decline of $46.3M (-4.9%) for a total of $908 million.

EBSMs in Action:

Skills Development-Regular

Yukon

Yukon uses the SD-R program to assist eligible participants obtaining skills for employment, ranging from basic to advanced skills, through direct assistance to individuals to cover certain costs associated with taking a course/program or instruction or training. Eligible participants are those individuals who meet the 'Insured Participant' definition as per the Employment Insurance Act and who have been identified by a case manager as having insufficient employment or marketable skills to successfully obtain employment. The key principles of the program include: reinforcement that if participants plan their future development, commit to an action plan and contribute to the implementation of the plan are most likely to succeed; the action plan identifies lack of marketable skills as an employment barrier, and demonstrates that a SD-R intervention will support re-entry into employment; the level of assistance accorded to an eligible participant to take a course, program of instruction or training is negotiated; providing a mechanism that allows participants to make an appropriate financial contribution to the costs of the intervention where required; and, demonstrating that training activity supports the participants' ability to enhance their skills to obtain and maintain a job.

EBSMs in Action:

Skills Development-Apprentices

Ontario

Ontario's SD-Apprentices program provides temporary financial assistance to eligible apprentices who participate in full-time classroom training. As apprentices do not work for the duration of their in-class training, they may experience a significant financial impact during this portion of their apprenticeship training program. Participants include individuals currently eligible for Employment Insurance benefits or who were in receipt of Employment Insurance benefits in the past three to five years. Although the majority of training occurs in the workplace, the in-classroom training component is critical to apprentices' success as it provides them with the theoretical training that supports the practical on-the-job training. Full-time classroom training can be up to eight weeks in length and typically occurs two to three times during an apprenticeship training program. Along with basic living costs, this program provides personal supports, which includes dependent care allowance, travel allowance, living-away-from-home assistance and disability allowance.

Alberta

Skills Development-Apprentices benefits provide financial assistance to individuals to make their own arrangements to obtain skills for employment, including apprenticeship training. Alberta's apprenticeship and industry training is an industry-driven system that ensures Alberta has a highly skilled, professional and internationally competitive workforce in more than 50 designated trades and occupations. The Alberta Apprenticeship and Industry Training Board works with industry to set training and certification standards. The Board makes recommendations to the government to meet the needs of Alberta's labour market for skilled and trained workers, and the designation of trades and occupations. The Government of Alberta's priority is to ensure that the over 60,000 apprentices currently engaged at various stages in their learning career successfully meet the requirements for journeyman certification, and are therefore able to contribute to the continued growth of Alberta.

Nunavut

The Adult Learning and Training Supports (ALTS) program remains the flagship labour market program for skills development for apprentices and non-apprentices in the territory. Under ALTS, apprentices access support for technical training. Other non-apprentice clientele access ALTS to pursue training that responds to labour market demand and opportunity.

1.4.2 Targeted Wage Subsidies

Targeted Wage Subsidies encourage employers to hire individuals they would not normally hire, giving them a chance to complete a successful career transition. In 2014/2015, TWS interventions decreased considerably by 7.2% year over year, to 11,643. The share of TWS of all Employment Benefits interventions dropped to 8.2%. While total expenditures for TWS increased by 28.3% to $103.7 million, reflecting rising average cost per intervention in most jurisdictions, the duration of TWS interventions decreased, on average, by 0.6% year over year.

EBSMs in Action:

Targeted Wage Subsidies

Yukon

Yukon supports the Targeted Wage Subsidy (TWS) program, which assists individuals who lack work experience by enhancing their skills through employment. A wage subsidy is provided to the employer to hire someone they would not normally hire in the absence of a subsidy. Individuals who are approved for TWS may include individuals who do not have recent work experience, who may require substantial employer training, and/or who might have difficulty getting their "foot in the door" for other reasons. Employment offered under the TWS provides individuals with full-time (may be part-time for persons with disabilities) on-the-job work experience. Wages earned by the individual are insurable and provided directly by the employer. The employer is then reimbursed with a subsidy for a specified percentage of the wage. Financial assistance may be provided to employers to cover the costs associated with employment related costs (including workers' compensation actual costs). However, in most cases, employers are encouraged to cover such costs. The duration and level of subsidy are based on the needs of the participant. The TWS is intended to off-set costs related to hiring the individual and is not intended to resolve an employer's human resource or cash-flow problem. The expectation is that normally the subsidy will lead to permanent employment with the TWS employer.

1.4.3 Self-Employment

The Self-Employment intervention helps insured clients start their own businesses, through counselling and development related to launching a new business. In 2014/2015, participation in SE decreased by 8.3%, to 7,361 interventions. SE's share of total benefits interventions edged down slightly to 5.2% (-0.2 percentage points). Corresponding with these trends, SE total expenditures decreased by $8.5 million (-7.7%) for total of $102.5 million in 2014/2015.

EBSMs in Action:

Self-Employment

New Brunswick

The Self-Employment (SE) program helps insured clients start their own businesses, through counselling and development related to launching a new business or becoming a self-employed worker. New Brunswick's Workforce Expansion Self-Employment Benefit Program helps unemployed individuals create a job for themselves by starting a new business. The program provides various types of support during the initial development phase of the business including financial assistance, coaching and ongoing technical advice. Coaching is tailored to meet individual needs and can include subjects such as business plan development, accounting, and marketing. This program is delivered in partnership with non-profit, private and/or public organizations.

1.4.4 Job Creation Partnerships

Job Creation Partnerships provide EI-insured clients with work experience while helping the community and local economy. Provinces and territories delivered a significant increase (+9.5%) of JCP interventions, totalling 3,165. JCPs' share of total benefits interventions edged up by 0.3 percentage points for a total 2.2%. JCP expenditures reached $33.6 million (+19.4%), an increase of $5.5 million.

EBSMs in Action:

Targeted Wage Subsidies

British Columbia

Job Creation Partnerships (JCP) provides EI-insured clients with work experience while helping the community and local economy. In British Columbia, a number of JCP projects were funded to provide individuals with opportunities to gain work experience leading to ongoing employment. These include:

- Qatuwas 2014: Participants were members of the Heiltsuk First Nations community, who worked on the preparation, production, and post-production of the cultural celebration of canoe culture of Coastal First Nations. Their activities include building bleachers, kiosks, signage, harvesting and preparing traditional cuisine and making ceremonial gifts. Participants gained skills in event preparation while also connecting to their cultural legacy.

- Lake Babine Timber: Participants took part in a 47-week project to build firewood storage sheds and two timber bridges, as well as to perform general timber cutting. The Lake Babine First Nation plans to build a biomass plant for heating homes in the area. Participants gained skills in forestry and carpentry that should prepare them for participating in building the biomass plant.

- Plan@t: Participants with disabilities assessed and provided accessibility ratings for various Lower Mainland business for the Rick Hansen Foundation Plan@t website. People can use this site to search and review the accessibility of places worldwide.

1.4.5 Targeted Earnings Supplements

Targeting Earning Supplements provide insured clients with incentives to accept employment. In 2014/2015, Quebec offered TES-similar programming through its Return to Work Supplement program. This TES-similar benefit supported 2,692 participants in 2014/2015, a significant drop of 53.3% decrease year over year. In line with the drop in the number of interventions delivered, Quebec's total expenditure for this benefit fell 54.4% to $1.3 million.

1.5 Interventions: Support Measures

Part II of the Employment Insurance Act authorizes three support measures: Employment Assistance Services (EAS), Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs), and Research and Innovation (R&I). Through LMDAs, provinces and territories deliver these measures at the regional and local levels, while ESDC retains responsibility for pan-Canadian delivery of LMPs and R&I (see section IV of this chapter). Support Measures are available to all unemployed individuals in Canada, including non-insured clients; however, LMPs and R&I are generally not associated with direct client service and therefore do not have participants or interventions. Delivered by the provinces and territories, the EAS component of the Support Measures provides a full range of self-help and assisted services, such as help with determining career objectives through employment counselling; improving job search techniques; completing a return-to-work action plan; and accessing labour market information in support of career choices.

1.5.1 EAS Interventions

Provinces and territories design and deliver interventions similar to EAS, which are available to all unemployed people in Canada. In addition to helping EI-insured clients, EAS interventions provide crucial support to those who have been absent from the labour market for an extensive period or who have low labour market attachment. They may also support new immigrants or young people who are entering the Canadian labour market. These interventions are reported in one of the three following categories: Employment Services, Group Services, and Individual Counselling. In 2014/2015, a total of 936,144 EAS interventions were delivered, a notable year-over-year decrease of 2.7%. This decline reflects improving labour market conditions and less reliance by unemployed workers to require short-term active employment measures. However, its relative share of all EBSM interventions increased to 86.8% in 2014/2015; an increase of 0.3 percentage points year over year. Total expenditures on EAS increased to 629.9 million (+6.1%) in 2014/2015.

1.5.1.1 Employment Services

Interventions similar to Employment Services continued to be the most common EAS intervention type at 61.8% of all EAS interventions in 2014/2015. A total of 578,292 Employment Services interventions were provided to unemployed individuals in Canada, which represents a decline of 2.7% compared to 2013/14. Compared to 2009/10, a year during which provinces and territories were addressing unemployment peaks stemming from the recession, the number of Employment Services interventions is down by 44,652 or 7.2% in 2014/2015.

EBSMs in Action:

Employment Assistance Services

Manitoba

The Employment Assistance Service (EAS) program provides employment assistance to unemployed and underemployed Manitobans to help with career counselling and job search. Manitoba delivers EAS directly through 13 provincially operated Manitoba Jobs and Skills Development Centres, as well as indirectly through a vast network of third party service providers. In addition to supporting mainstream service providers that deliver services to all Manitobans, the province partners with a select number of specialized agencies to assist immigrants and refugees in various communities with large newcomer communities, including Winnipeg, Brandon, Steinbach, Winkler and Morden. These agencies provide tailored supports to address the employment needs of newcomers, such as offering multilingual services. In 2014/2015, these agencies assisted nearly 1,000 newcomers.

Yukon

Yukon's EAS program assists eligible participants to find and obtain employment, or to develop the skills necessary to maintain employment. Eligible recipients are individuals from businesses (including crown corporations), organizations (formal, ad hoc or partnerships), municipalities, First Nation organizations, governments and councils, public health and post-secondary educational institutions. Eligible participants are those who are unemployed, legally entitled to work in Canada and available for and actively seeking employment. Clients work with their case manager in a collaborative process in order to assess, plan, and facilitate activities and services that will meet the employment needs of the Participant. Each step in the case management process is important in developing an action plan that accurately reflects the participant's circumstances, existing skills, employment barriers and the related interventions. An action plan must be developed with the active input and agreement of both the participant and the case manager.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Fiscal 2014/2015 was the first full year in which Newfoundland and Labrador delivered EAS through its internal service delivery network for the majority of its clients, following the decision in 2013 to internalize the supports and services previously offered through third-party contracts for EAS. In an effort to improve access for clients, Newfoundland and Labrador has enhanced and promoted the use of on-line application for service, and on-line courses and workshops. In 2013, the Employment and Training Assessment (ETA) was introduced to allow clients to complete an on-line guided self-assessment of employment readiness and apply for employment and training supports. As well, a series of on-line workshops are available to assist individuals in their career and employment planning process, and to assist employers with a host of human resource related needs were developed in conjunction with the Bluedrop CoursePark Learning Management System (CPLMS). In 2014/2015, 3,570 workshops were accessed by individuals and employers.

Nunavut

Clients in Nunavut can receive face-to-face Employment Assistance Services through Career Development Officers (CDO) located in one of three regional offices in Pangnirtung, Rankin Inlet and Cambridge Bay, or in the communities of Arviat, Baker Lake, Igloolik, Iqaluit, and Kugluktuk. Career Development Officers are responsible for conducting community visits to locales where a CDO is not physically located. Clients can also contact the regional offices via a toll-free number.

1.5.1.2 Group Services

Group Services dropped significantly by 19.5% for a total of 37,849 interventions delivered in 2014/2015. In this context, the share of Group Services of all EAS-type interventions decreased by 0.9 percentage points for a total 4.0%.

1.5.1.3 Individual Counselling

In addition to being the initial intervention for establishing action plans and potential access to Employment Benefits, Individual Counselling can be an important measure for multi-barriered clients. A total of 320,003 Individual Counselling interventions were supported in 2014/2015. This represented a drop of 0.4% year over year. Individual Counselling accounted for 34.2% of all EAS interventions, edging up from its 33.4% share in 2013/14. The use of Individual Counselling is consistent with the increased numbers of multi-barriered clients, who access EBSM-similar programming following short-term unemployment, as well as an indication of the participation of displaced workers. Footnote 14

1.5.2 Labour Market Partnerships

The Labour Market Partnership (LMP) initiative facilitates the collaboration of employers, employee and employer associations, community groups, and communities to develop solutions to labour force imbalances such as persistent high unemployment or skill shortages. LMP expenditures contracted for a second consecutive year, dropping significantly to a total of $128.6 million in 2014/2015 (-10.5%). Almost all jurisdictions made noticeable investments in LMP initiatives in 2014/2015, with strongest commitments made by Quebec, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, British Columbia and Manitoba.

EBSMs in Action:

Labour Market Partnerships

Ontario

Ontario's LMP funding provides financial assistance to local communities, employers, sector groups and employee and employer associations to aid the development and implementation of strategies that address and respond to labour force adjustments, local economic development and human resource planning needs. For example, funding was provided to an Employment Ontario service provider in Windsor that is seeking to better understand the challenges that employers face in recruiting, hiring and retaining women in the skilled trades. This funding allowed them to identify strategies that increase employment and also identify potential policy strategies that promote women's employment in the trades. Funding was also provided to a community stakeholder with a background in addressing labour market issues to determine common success factors for people who were able to find a job match and begin an apprenticeship. In addition, the project explored whether there are differences in success factors between industries or specific trades based on considerations such as level of education, related training, and willingness to travel.

Nova Scotia

In 2014/2015, LMP funding in Nova Scotia was used exclusively for the Sector Council Program—a cooperative partnership between Labour and Advanced Education and various industry sector organisations to support human resource development, attraction and retention, and training. The purpose of the Sector Council Program is to support an industry-led approach to human resource development tailored to meet the labour market needs of industry sectors. The program focuses on ensuring that small- and medium-sized enterprises in Nova Scotia have increased access to expertise, resources and support in the area of human resource planning. The three priority areas of the program include human resource planning; attraction and retention; and, training. The sector council program was created as a 3 year pilot program, and an evaluation was competed in the final year of the pilot. Results from the evaluation have shown that the objectives laid out in the program were the correct ones, and that the 3 year funding model allowed for strategic planning and investments, and for the ability to reach the employer community. The program received a great deal of support and is planned to continue.

Northwest Territories

In the Northwest Territories, LMP funding supports Skills Canada-NWT to assist with their mission to promote careers in skilled trades and technology for northern youth. The organization pursues this mission through community-based skills clubs, youth conferences, regional skills competitions, and a territorial skills competition, as well as taking a team to the annual Skills Canada National Competition. The organization also hosts career expos with its competitions and offers presentations about careers in skilled trades. Skills Canada-NWT is well positioned to link youth, employers, and educators. The organization works with stakeholders in many sectors including education, government, and industry.

Saskatchewan

In partnership with New Brunswick, Community Based Organizations, and the Canadian Career Development Foundation, Saskatchewan contributed to evidence-based research for the Career Development field of practice. Launched in July 2014 and concluded in 2015, Transforming the Culture of Evaluation in Career and Employment Services, Common Indicators Project-Phase II, was conducted by the Canadian Career Development Foundation. It focused on determining changes job seekers experience as a result of career and employment programs and services. The study identified the types of interventions and delivery methods best suited to achieve outcomes with EI eligible job seekers. In Saskatchewan, 31 career practitioners and 249 job seekers participated. The project provided a model and incremental resources to enhance career practitioners' skills and professional competence to better serve Saskatchewan job seekers. Furthermore, the project served to enhance Saskatchewan's evaluation of how career and employment programs and services respond to the needs of diverse job seekers, help job seekers make meaningful progress in the employability dimensions and connect to employment.

1.5.3 Research and Innovation

Research and Innovation (R&I) initiatives identify better ways of helping people prepare for, return to or maintain employment, and participate productively in the labour force. In 2014/2015, all jurisdictions with R&I programs increased investments in this area, more than doubling expenditures from $15.1 million to $32.1 year over year. Five provinces and territories Footnote 15 used $21 million in LMDA funding through R&I projects to test the reach and impact of the Canada Job Grant (CJG). The CJG encourages employer involvement and investment in training by providing financial assistance to employers on a cost-shared basis to help Canadians develop the skills needed for available jobs.

EBSMs in Action:

Research and Innovation (R&I) Activities

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island continues to support R & I projects to identify creative ways of helping Islanders prepare for, return to or keep employment and become productive participants in the labour force. In the context of higher rates of youth unemployment, the province continues to develop strategies to ensure youth are well informed about future career opportunities and have the support to make successful transitions to training and employment. In 2014/2015, collaboration between the province's secondary and post-secondary systems resulted in the development of the Student Graduation and Transition Planner. This pilot project is designed to assist all secondary students with planning their graduation pathways, post-secondary transitions and labour market attachment. The Student Graduation and Transition Planner will include career planning tools that focus on pertinent labour force information. The objective is to permit more informed career pathway choices and a foundation to empower secondary students to engage in a comprehensive, personalized three-year planning process of personal and career goals during their secondary school years. Teachers, students, parents/guardians, and post-secondary partners will work together to ensure informed educational and career transition goals are developed and articulated.

Ontario

Using R&I funding, in 2014/2015, Ontario launched the Canada-Ontario Job Grant, working with small, medium and large enterprises to establish pilot approaches that encourage employers to take a greater role in skills training and workforce development investments. The three pilots were:

- Canada-Ontario Job Grant: the program helps businesses purchase short-term training for new or existing workers that will help meet workforce performance needs.

- Canada–Ontario Job Grant: Customized Training Pilot: supports partnerships between employers and training institutions to develop and implement new-firm-specific technical or essential skills where no such training exists.

- Canada–Ontario Job Grant: UpSkill Pilot: supports partnerships between employers and training providers to develop and deliver sector-specific integrated and technical skills training to meet employers' needs, specifically targeting low and medium skilled occupations.

Following the launch, Ontario estimated approximately 2,500 clients would benefit from training under this new program in the first year.

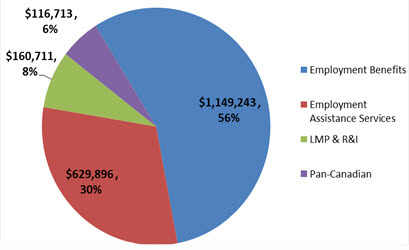

1.6 Expenditures

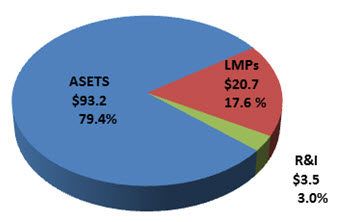

In 2014/2015, total expenditures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act increased by 0.5% to $2.06 billion. Footnote 16 Of that amount, Employment Benefits remained the largest category of expenditures, representing 55.9% of the total, while its relative share decreased by 1.6 percentage points from last year. LMPs and R&I increased by 1.2% to a total of $160.1 million. EAS expenditures increased 6.1%, representing a greater share of overall expenditures (30.6%, or an increase of +1.6 percentage points). Pan-Canadian expenditures remained unchanged with a slight drop of $242,000 for a total of $116.7 million (-0.2%).

Show Data Table

| 2013/2014 | ||

|---|---|---|

| $ | % | |

| Employment Benefits | 1,149,243 | 56% |

| Employment Assistance Services | 629,896 | 31% |

| LMP & R&I | 160,711 | 8% |

| Pan-Canadian | 116,713 | 6% |

| Total | 2,056,563 | 100% |

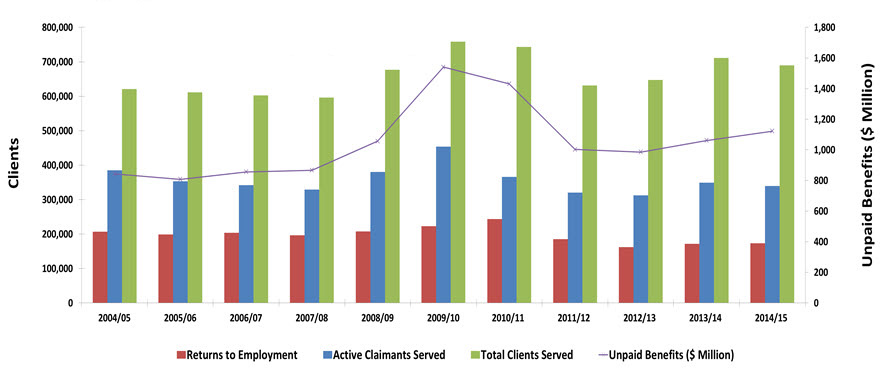

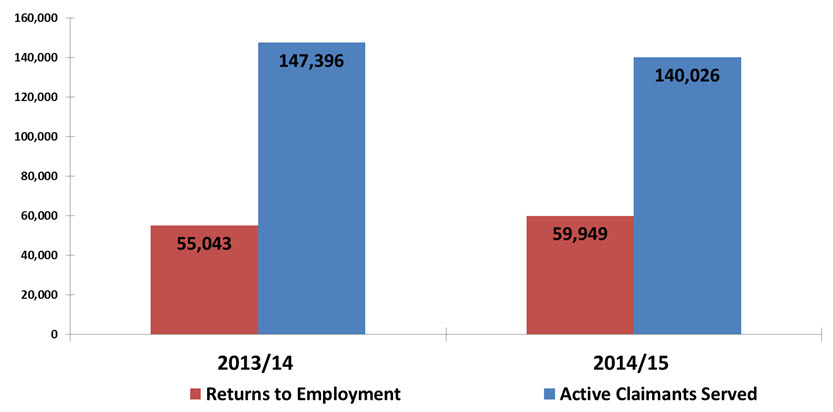

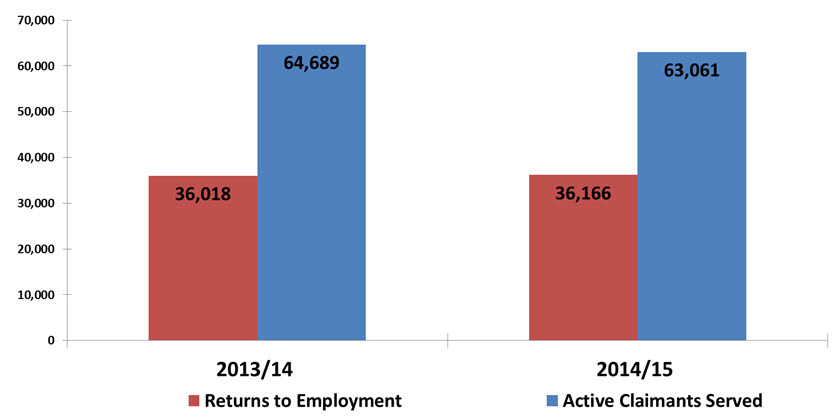

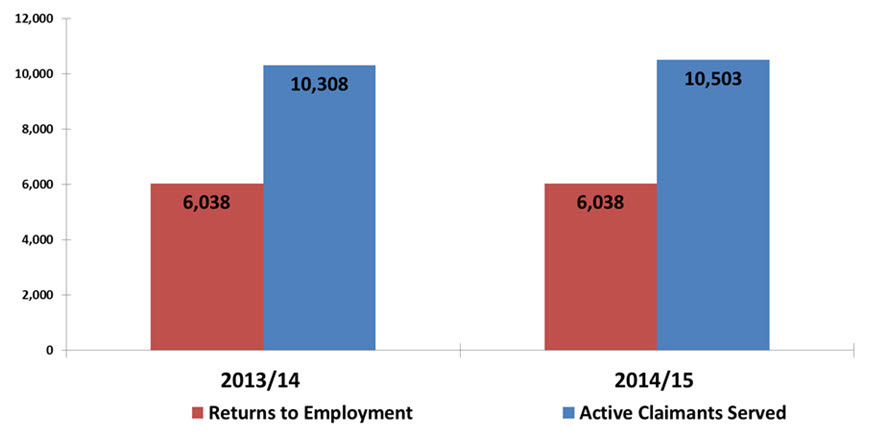

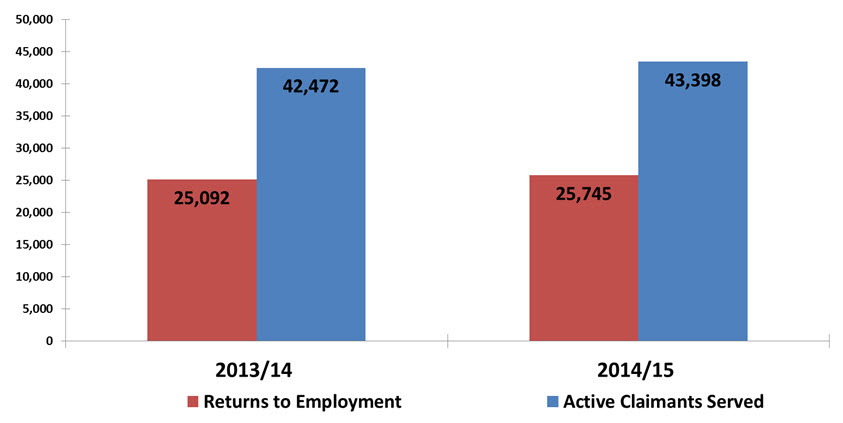

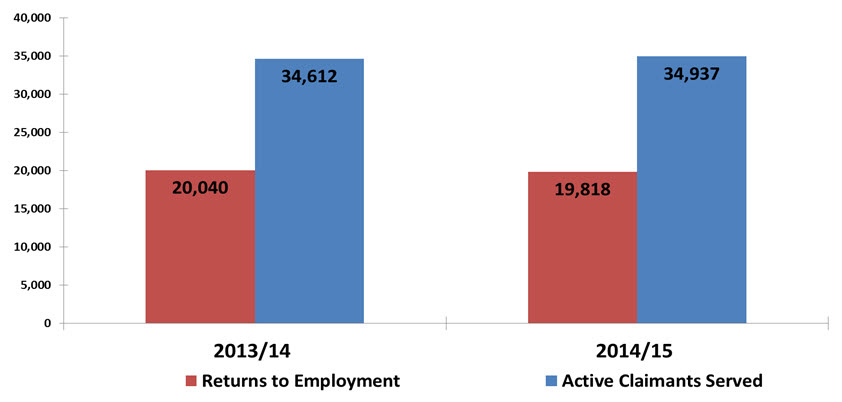

1.7 Key Performance Indicators Footnote 17

ESDC monitors the results of EBSM-similar programming delivered by provinces and territories through three key performance indicators:

- the number of active EI claimants served; Footnote 18

- the number of EI clients (active and former) who return to employment following an intervention; Footnote 19 and

- the amount of unpaid EI Part I benefits resulting from the returns to employment.

Show Data Table

| 2004/2005 | 2005/2006 | 2006/2007 | 2007/2008 | 2008/2009 | 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returns to Employment | 207,073 | 198,727 | 203,692 | 196,498 | 207,927 | 222,526 | 243,476 | 185,029 | 161,993 | 171,956 | 173,593 |

| Active Claimants Served | 385,213 | 353,542 | 342,145 | 329,127 | 380,181 | 453,781 | 365,978 | 320,006 | 312,553 | 348,909 | 339,795 |

| Total Clients Served | 620,787 | 611,420 | 602,157 | 595,910 | 676,842 | 758,761 | 724,907 | 631,522 | 647,127 | 711,042 | 689,459 |

| Unpaid Benefits ($ Million) | $843.08 | $807.47 | $856.30 | $866.90 | $1,056.70 | $1,540.30 | $1,430.40 | $1,002.86 | $985.44 | $1,061.50 | $1,121.98 |

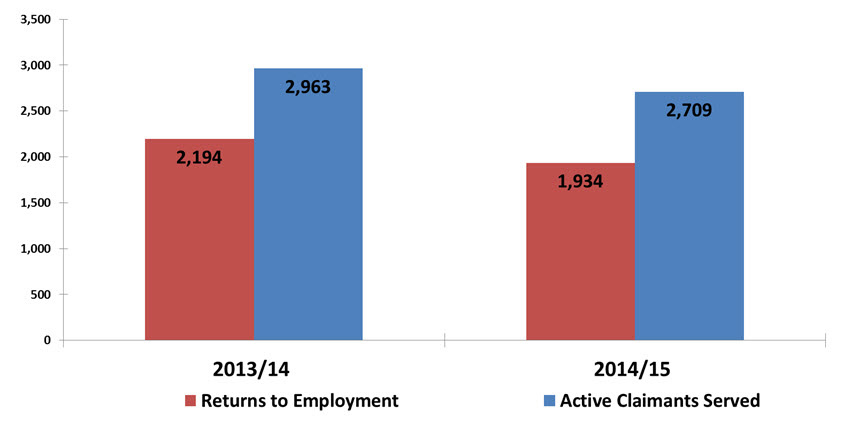

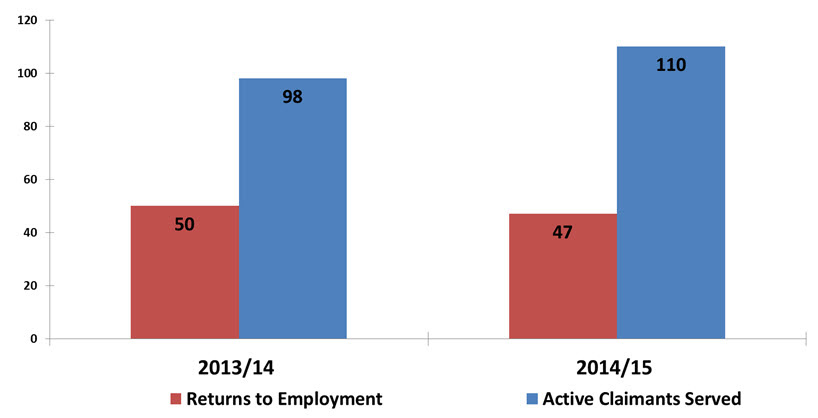

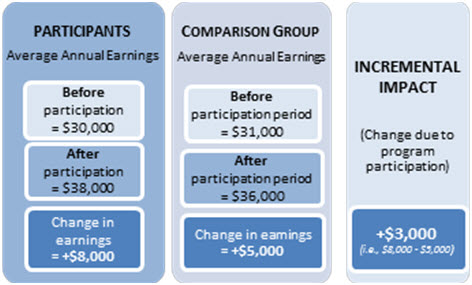

In 2014/2015, the three main performance indicators overall reflected Canada's labour market performance. The number of clients (173,593) employed increased by 1.0% year over year, while number of active claimants served (332,099) dropped by 2.7%. As a result, unpaid benefits ($1,122 million) increased by 5.7%. That said, the average length of an Employment Benefits intervention increased by 2 days (106 days), stemming from duration increases for all benefits.

1.8 Early Interventions with EI clients

The Government of Canada is committed to working with interested provinces and territories to make active employment supports available to EI claimants earlier in their claim, and to study the impacts of such measures. In 2013/14, this included Collaboration Projects with British Columbia and Manitoba, which tested the impact of early interventions in the delivery of active measures on EI claimants. Results suggest that the Collaboration Projects were most effective when early interventions focused on clients with relatively high re-employment potential.

These results complement internal evaluation work, previously mentioned in the 2013/14 EI MAR, on the timing of participation in EAS. This study showed that participants who started their intervention within four weeks after initiating an EI claim achieved quicker returns to employment and had earnings gains in both the short and medium term after participation.

Such evidence provided the rationale for the development of a national Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) tool to help provinces and territories identify and target EI applicants for employment programming based on local labour market needs. Similar tools for targeted interventions have been implemented in the United States, Australia and Denmark to support unemployed individuals with active employment services. The Province of Québec pioneered the development of the TRF with the Government of Canada, and in 2014 implemented an improved national TRF system. British Columbia also implemented the TRF system in the fall of 2015 to promote early interventions with clients.

2. Provincial and Territorial EBSM Activities

This section analyzes the provincial and territorial economic environment and EBSM-similar activities in 2014/2015, linking trends in clients served, interventions and expenditures to local labour market conditions, as well as employment programming priorities.

2.1 Context

To address their unique labour market challenges, provinces and territories deliver employment programming under LMDAs, which were individually negotiated with the Government of Canada. Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories receive funding to support the delivery of programs and services that are similar to the EBSMs established in Part II of the EI Act. Footnote 20 Provinces and territories design and deliver virtually all EI-funded employment programming, with the exception of pan-Canadian activities, which are discussed in Section IV of this chapter.

In 2014/2015, most provinces and territories recorded modest to moderate economic growth. In this context, the demand for EBSM-similar programming in most jurisdictions decreased, as observed in declining numbers of all client types (active, former, and non-insured), stemming from somewhat improving labour market conditions. In terms of interventions, all Employment Benefits declined, with the exception of Skills Development-Apprentices and Job Creation Partnerships, which saw a moderate increase. For provinces and territories, apprentice training remains an integral component as a means of preparing their workforce for skilled trades.

Provinces and territories continued to identify an aging workforce, and skills and labour shortages, as the key labour market challenges they planned to address with EBSM-similar programming. They also focused on developing and delivering skills training to meet current and future skills requirements, and on optimizing the existing labour supply, by working to increase the participation of underrepresented groups in the labour force, such as immigrants, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities and youth.

To support EI clients with programming earlier in their EI claims, some jurisdictions have implemented mechanisms to support targeted early interventions aimed at quicker returns to employment. Some of the strategies are discussed in this section under the provincial and territorial summaries. In addition, all jurisdictions set targets for the three key performance indicators: clients served, clients employed and unpaid benefits to the EI Account.

2.2 Newfoundland and Labrador Footnote 21

In 2014, Newfoundland and Labrador experienced negative growth as real GDP shrank by 3.0%. In 2015, real GDP is poised to decline by roughly 2.0% as well. The weakness in commodity prices presented significant challenges for the Newfoundland and Labrador economy. However, the weaker Canadian dollar had a positive impact on the provincial manufacturing sector.

In 2014/2015, Newfoundland and Labrador registered an average of 2,200 (+100 year over year) job vacancies, with the strongest labour demand observed in health care, construction and retail trade. The province's job vacancy rate of 1.1% was below the national average of 1.6%, suggesting a relatively loose labour market, which is consistent with the decline in the province's real GDP for 2014.

Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Clients | Non-Insured Clients |

|---|---|

11,363

|

1,126

|

| Interventions Type | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 8,591 | 15.5%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 15,745 | 43.1%

|

| Interventions Type | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 35.3% | 5.0

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 64.7% | 5.0

|

| Total Expenditures | 2014/2015 ($ Million) |

Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $115.7 | 7.0%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | $5.0 | 9.1%

|

| LMPs and R&I | $1.5 | 49.9%

|

| Total Expenditures1 | $122.2 | 5.6%

|

| 2013/14 | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| $25.69 | $25.35 | 1.3%

|

- 1 Totals may not add due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

In this economic context, the unemployment rate in Newfoundland and Labrador edged up by 0.6 percentage points to 12.2%. Employment decreased to 237,100 (-4,800), with full-time employment declining by 6,000 and part-time employment increasing by 1,200. The province's unemployment totals increased by 3% (+1,000). Newfoundland and Labrador's labour market participation rate stood at 60.8%, a downward slide of 0.7 percentage points year over year.

Employment in the goods-producing industries edged down by 1,800, reaching a total of 54,300 in 2014/2015. The biggest losses were experienced in the manufacturing (-1,200) and forestry, fishing, mining, oil and gas (-900) industries. Employment in the services-producing sector dropped to 182,800 (-3,000 or -1.6%). Employment losses were concentrated in: other services (-2,300 or -16.3%); public administration (-2,200 or -11.5%); educational services (-1,300 or -6.8%); as well as in health care and social assistance (-1,300 or -3.3%). Solid employment gains were recorded in professional, scientific, and technical services (+1,400 or +14.6%) and trade (+3.3% or +1,300).

Skill shortages and mismatches continued to be among the main labour market challenges in Newfoundland and Labrador. Other issues include population aging combined with declining population growth, and a relatively large proportion of the labour force in rural areas of the province (47% versus 16% in Canada). The province identified a number of labour market priorities in 2014/2015 to address labour and skill shortages and mismatches. To ensure a sufficient supply of skilled workforce is available, Newfoundland and Labrador focused its efforts on recruitment and retention and skills development strategies, investing significantly in employment and training programs, as well as in working closely and collaboratively with stakeholders, including with its recently established network of 27 employment centres to implement education and employment training objectives.

| Employment Benefits | Interventions | Year-over-Year Change | Expenditures ($ 000s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWS | Newfoundland and Labrador Wage Subsidies | 880 | +22.1% | 7,860 |

| SE | Newfoundland and Labrador Self-Employment Assistance | 179 | -5.8% | 5,382 |

| JCPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Job Creation Partnerships | 1,196 | +42.6% | 8,156 |

| SD-R | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 3,609 | +7.3% | 94,319 |

| SD-A | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 2,727 | +17.1% | |

| Support Measures | ||||

| EAS | Newfoundland and Labrador Employment Assistance Services | 15,745 | +43.1% | 4,973 |

| LMPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Partnerships | N/A | N/A | 1,521 |

| R&I | Research and Innovation | N/A | N/A | |

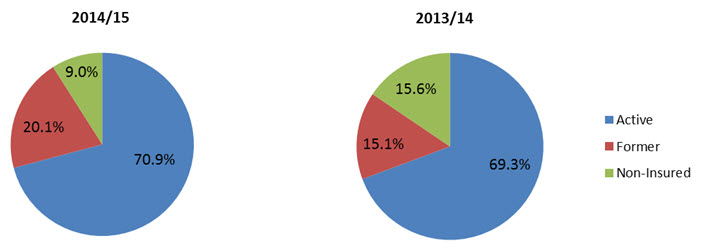

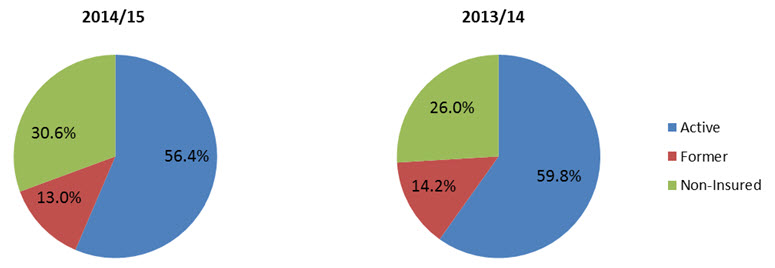

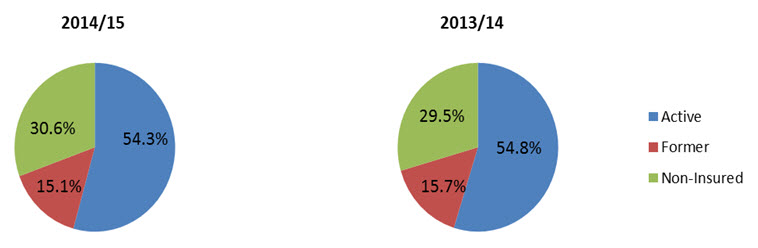

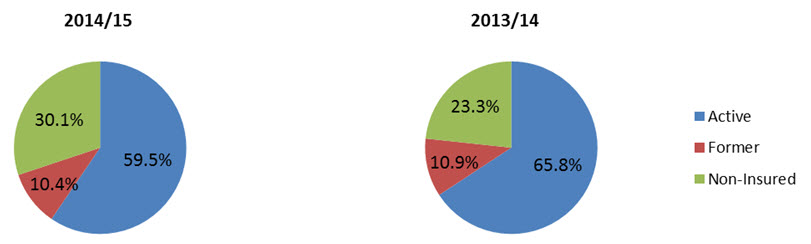

In 2014/2015, Newfoundland and Labrador served a decreasing numbers of clients, totaling 12,489 (-2.0%), compared to 12,739 in 2013/14. This is recorded in the context of a downward trend over the last five years. Two of the three client types expanded, with the numbers of active (8,850) and former (2,513) claimants both rising, though at different pace (+0.2% and +30.3%, respectively). Similarly, the shares of active (70.9%) and former (20.1%) claimants both rose, the first by 1.6 percentage points, and the second more significantly (+5.0 percentage points), consistent with the shift in their respective numbers. In contrast, the non-insured clients fell considerably from the 2013/14 total of 1,980, down to 1,126, influencing the overall total in terms of clients served. Similarly, its share of all clients served also contracted significantly to 9.0% (-6.5 percentages points).

Show Data Table

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Active Clients | 8,850 | 70.9% |

| Former Clients | 2,513 | 20.1% |

| Non-Insured | 1,126 | 9.0% |

| Total | 12,489 | 100.0% |

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Active Clients | 8,831 | 69.3% |

| Former Clients | 1,928 | 15.1% |

| Non-Insured | 1,980 | 15.5% |

| Total | 12,739 | 100.0% |

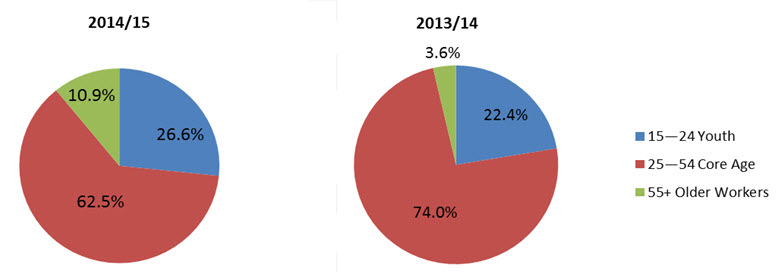

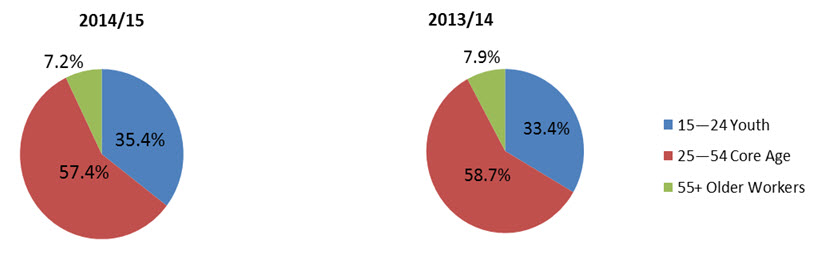

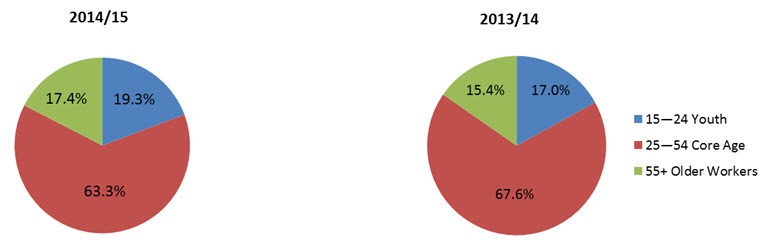

Show Data Table

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 15–24 Youth | 1,627 | 26.6% |

| 25–54 Core Age | 3,814 | 62.5% |

| 55+ Older Workers | 665 | 10.9% |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.0% |

| Total | 6,107 | 100.0% |

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 15–24 Youth | 2,325 | 22.3% |

| 25–54 Core Age | 7,699 | 73.9% |

| 55+ Older Workers | 376 | 3.6% |

| Unknown | 18 | 0.0% |

| Total | 10,418 | 100.0% |

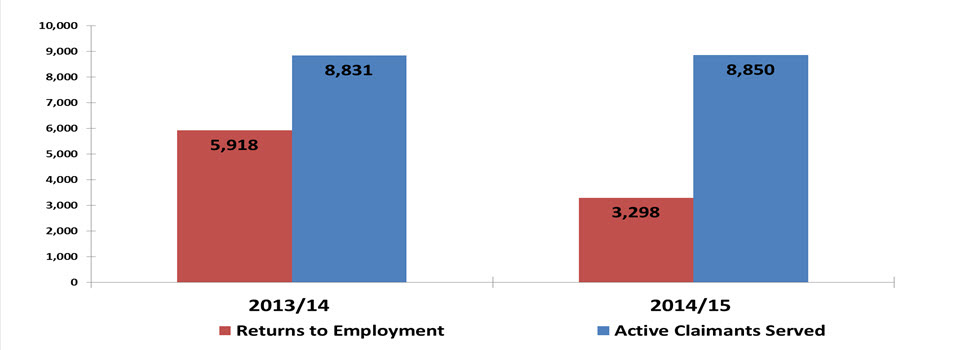

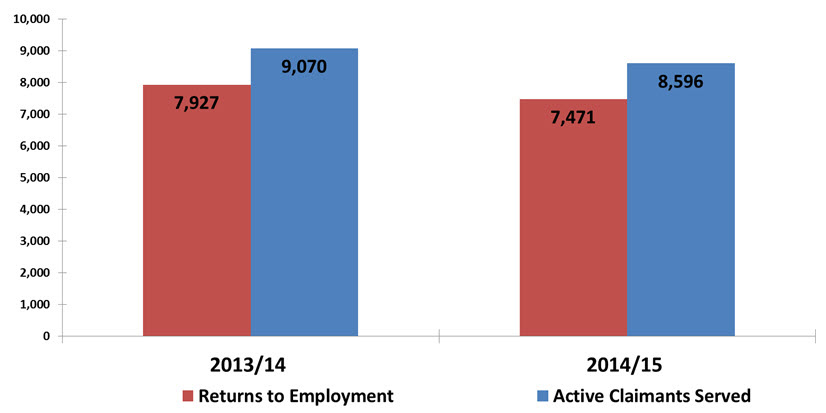

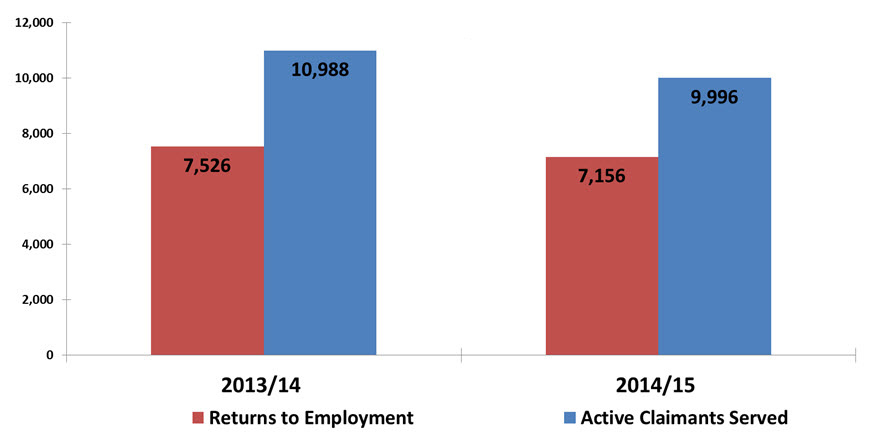

Newfoundland and Labrador's clients accessed a growing number (24,336) of EBSM-similar interventions in 2014/2015, a sharp year-over-year increase of 32.0%, largely attributed to the province resuming its Group Services support measure. Employment Benefits accounted for a declining share of 35.3%, while the numbers of its interventions expanded to a total of 8,591 (+15.5%), compared to 7,441 in the previous year. Consistent with the shift in the numbers of the EAS interventions, its share of all interventions increased, up to 64.7% from last year's 59.6%. A significantly declining total (3,298) of EI clients returned to employment following participation in the program (-44.3% year-over-year). Expenditures for EBSM-similar programming totalled $122.2 million of the $128.0 million allocated.

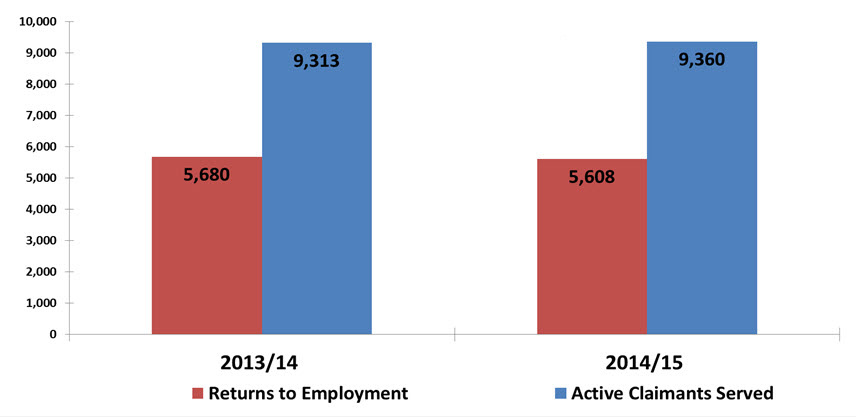

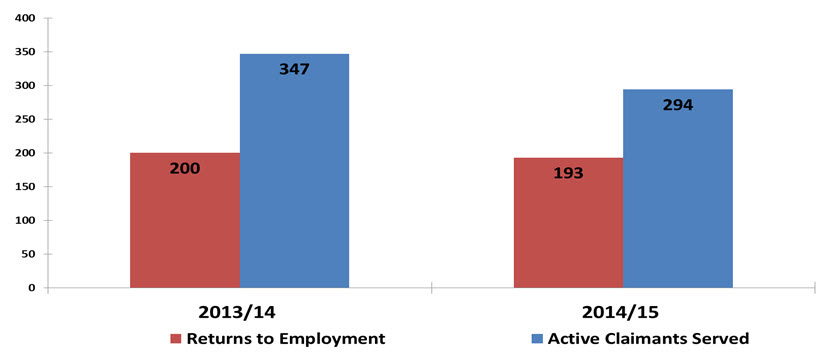

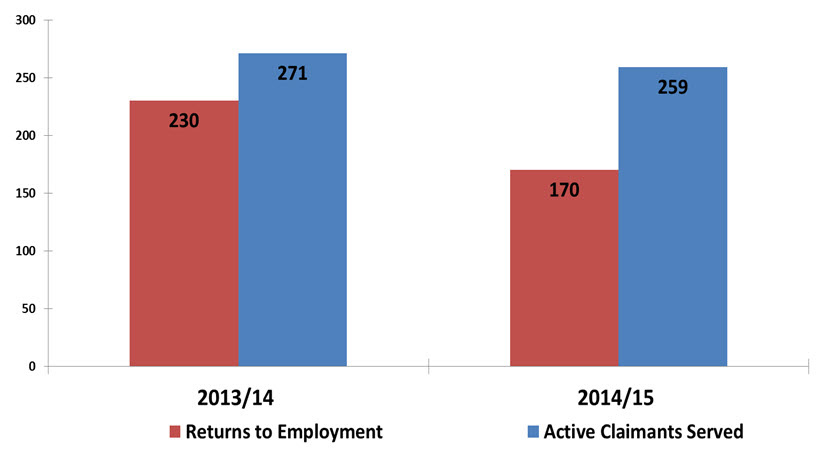

Show Data Table

| 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | |

|---|---|---|

| Returns to Employment | 5,918 | 3,298 |

| Active Claimants Served | 8,831 | 8,850 |

2.2.1 Employment Benefits

In 2014/2015, the province delivered significantly more Employment Benefit interventions, totaling 8,591 (+15.5% year over year increase). The use for Skill Development interventions rose, with SD-R (3,609) and SD-A (2,727) both expanding significantly by 7.3% and 17.1%, respectively. JCP (1,196) is another benefit intervention that experienced considerable growth (+42.6%). In addition, TWS (880) grew for a second consecutive year, edging up significantly in 2014/2015 by 22.1%, while SE (179) fell (-5.8%) this year, after expanding in 2013/14. As for the shares of the benefit types, SD-R accounted for a decreasing proportion of all benefits at 42.0%, but the share of SD-A edged up slightly to 31.7% (+0.4 percentage points). Combined SD-R and SD-A accounted for a 73.8% share of all benefits, compared to 76.5% in the previous year, reflecting a continued focus on skills development and enhancement. Employment Benefits total expenditures rose significantly to a total of $115.7 million (+7.0%), consistent with the increase in the number of benefit interventions delivered.

2.2.2 Support Measures: EAS

After four consecutive years of decline, the use of EAS in Newfoundland and Labrador increased considerably in 2014/2015, with total numbers reaching a five-year high of 15,745 (+43.1). The EAS types delivered in the province all recorded noticeable gains, though at different paces. Employment Services—the most widely used EAS—grew significantly to a total of 8,238 (+5.6%), and Individual Counselling (4,500) edged up sharply (+40.6%). Additionally, Group Services—an intervention that was last used in 2009/10—resumed in 2014/2015, with a total number of interventions delivered reaching 3,007. The noticeable increase in the EAS numbers can be attributed to a growing demand for employment programming due to weakening labour market conditions. EAS expenditures reached a total of $5.0 million (+9.1%), consistent with the increase in the total numbers of EAS interventions.

2.2.3 Other Support Measures: LMPs

After expanding significantly to $6.4 million in 2012/13, expenditures for Newfoundland and Labrador's LMPs contracted over the past two years, with total expenditures dropping to $1.5 million in 2014/2015. This represented almost half of last year's value and a 10-year low. LMP expenditures accounted for a smaller share of 1.2%, compared to 2.6% in 2013/14.

2.2.4 Managing for Results

Newfoundland and Labrador manages for results through its new management information system, the Labour Market Programs Support System (LaMPSS), which has been operational as of 2014/2015. The LaMPSS is expected to maximize efficiency and improve service delivery for labour market programs and services. Data on interventions delivered in 2014/2015 are estimates based on the results generated through Newfoundland and Labrador's regional service delivery network. However, the province is undertaking supplementary data analysis in order to improve data quality for 2015/16.

2.3 Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island's real GDP rose by 1.2% in 2014 and is forecasted to have increased by 1.5% in 2015. The strength of the Island's construction, manufacturing, as well as surging exports, contributed to this growth. Strong demand for lobster in the United States and Europe is expected to boost the fishing industry, which makes up nearly one-third of the Island's primary sector. Coming off a strong year for tourism in 2014, the low Canadian dollar will continue to attract visitors from the United States, as well as Canadian-based traffic. However, weak growth in non-commercial services such as education as well as health and social services was observed in a period of government spending restraints.

Prince Edward Island: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Clients | Non-Insured Clients |

|---|---|

3,330

|

1,470

|

| Interventions Type | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 1,991 | 6.8%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 5,597 | 6.1%

|

| Interventions Type | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 26.2% | 2.6

|

| Support Measures: EAS | 73.8% | 2.6

|

| Total Expenditures | 2014/2015 ($ Million) |

Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $18.6 | 6.3%

|

| Support Measures: EAS | $4.7 | 3.7%

|

| LMPs and R&I | $2.4 | 38.0%

|

| Total Expenditures1 | $25.7 | 1.6%

|

| 2013/14 | 2014/2015 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| $7.19 | $6.08 | 15.4%

|

- 1 Totals may not add due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

In 2014/2015, Prince Edward Island recorded an average of 1,000 job vacancies (+500 year over year) with labour demand strongest in health care and social assistance, retail trade, and manufacturing. PEI's job vacancy rate (1.8%) surpassed the national average of 1.6% suggesting a relatively tight labour market.

In line with its moderate economic growth, Prince Edward Island's labour market reacted accordingly. Unemployment rate was down a full percentage point, going from 11.5% to 10.5%. Employment remained unchanged at 73,900, as full-time employment grew slightly by 1,000 while part-time employment declined marginally by 900. Participation rate dropped to 68.4%, a drop of a full percentage point year-over-year.