Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2019 and ending March 31, 2020 - Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures

In chapter 3

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2019 and ending March 31, 2020.

Abbreviations

- ADR

- Alternative Dispute Resolution

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- B/U Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed ratio

- B/UC Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed Contributor ratio

- BDM

- Benefit Delivery Modernization

- CAWS

- Citizen Access Workstation Services

- CCAJ

- Connecting Canadians with Available Jobs

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CCIS

- Call Centre Improvement Strategy

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSMs

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employment Contact Centre

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- EIR

- Employment Insurance Regulations

- EI SQR

- Employment Insurance Service Quality Review

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FLMM

- Forum of Labour Market Ministers

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- FY *

- Fiscal Year excluding the month of March

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- HRSDC

- Human Resources and Social Development Canada

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- IQP

- Integrated Quality Platform

- ISET

- Indigenous Skills and Employment Training

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MAEST

- Ministry of Advanced Education, Skills and Training

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- MTESS

- Ministère du Travail, de l'Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOS

- National Occupational Standards

- NWS

- National Workload System

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PAAR

- Payment Accuracy Review

- PPEs

- Clients who are Premiums Paid Eligible

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

- PRAR

- Processing Accuracy Review

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- R&I

- Research and Innovation

- RAIS

- Registered Apprenticeship Information System

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RSOS

- Red Seal Occupational Standards

- SA

- Social Assistance

- SCC

- Service Canada Centres

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SLAP

- Softwood Lumber Action Plan

- SME

- Small and medium sized enterprises

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- TRF

- Targeting, Referral and Feedback

- UV ratio

- Unemployment-to-vacancy ratio

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Introduction of chapter 3

Activities conducted under Part II of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act help individuals in Canada prepare for, find and maintain employment. Under the umbrella of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), these activities include programs delivered by provinces and territories under Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), as well as the Government of Canada's pan-Canadian programming and functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

This chapter presents program results for EBSMs achieved under Part II of the EI Act during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2019 and ending on March 31, 2020 (FY1920). Therefore, the impacts from the COVID-19 crisis are only slightly captured through the last 2 weeks of FY1920. Future reports will cover the impacts of Covid-19 more thoroughly.

Section 1 provides a national overview of EBSM-similar programming delivered under the LMDAs and by agreement holders under the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training (ISET) program (formerly known as the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy). Provincial and territorial EI-funded employment programming activities are presented in Section 2, with a description of each jurisdiction's labour market and employment priorities. Section 3 has 2 sub-sections presenting:

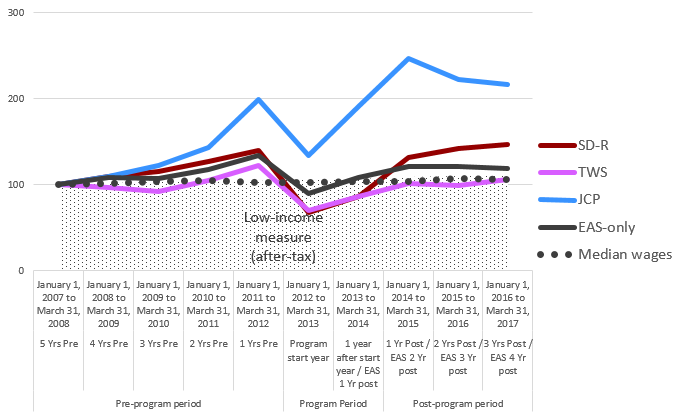

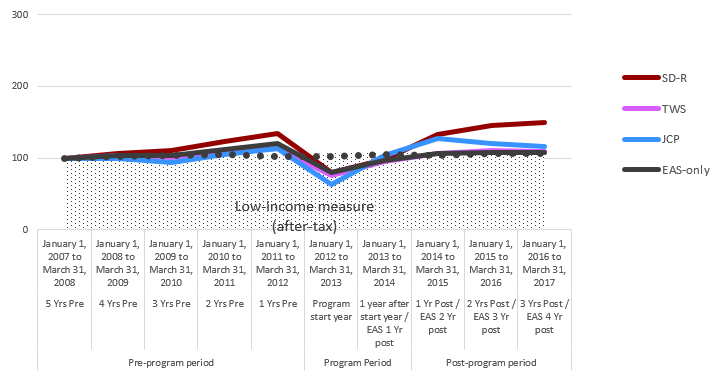

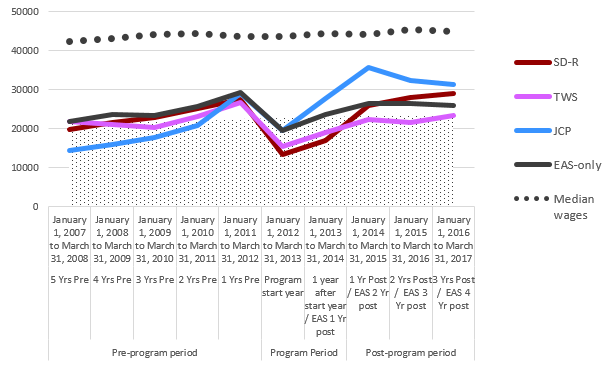

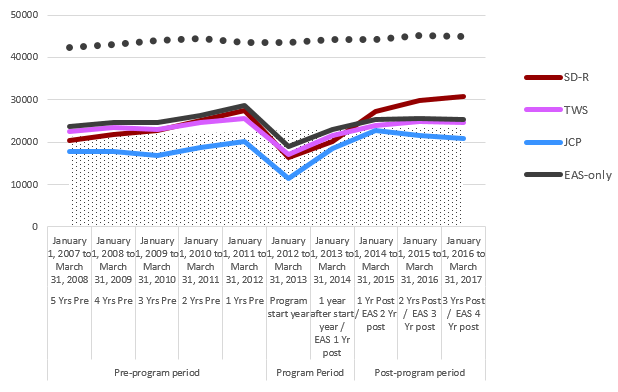

- an overview of an Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) study, with national results from the Third Cycle of LMDA evaluations, and

- the economic security analysis presented in the FY1819 MAR, and explores the impacts of LMDAs on the economic security of LMDA participants by sex, as well as for Indigenous peoples and visible minorities

Section 4 discusses the results of ESDC's delivery of pan-Canadian activities, and the administration of NES functions.

Notes to readers

- The data used to analyze EBSM activities were collected from provinces, territories and ISET agreement holders. Governments continue to improve data quality and collection to ensure accurate, reliable and consistent information. While all data sets are verified before publication, systems and operational changes may affect the comparability of data from year to year.

- References to average levels of activity and to highs and lows are based on the 10-year period from FY0910 to FY1920 as a frame of reference.

- Statistics Canada's Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the main source of labour market data reported. Data for Canada and the provinces are fiscal-year averages, calculated using seasonally unadjusted monthly data, while monthly references are seasonally adjusted. Data for the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are calculated using unadjusted 3-month moving averages of monthly data. In discussions of employment trends by industry, standard industry titles are taken from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

- Real GDP data and other non-LFS macroeconomic indicators are from Statistics Canada's Economic accounts. Forecasts rely on published analyses from the Bank of Canada, Canadian charter banks, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Parliamentary Budget Office of Canada, as well as on internal analysis, using information available as of March 2021.

3.1 National overview

In this section

3.1.1 Economic and labour market context

Economic conditions

In 2019, Canada's economy expanded by 1.9%, compared to 2.4% in 2018, due in part to lower growth in domestic demand. Canadian household final consumption expenditures grew by 1.6% in 2019, a more moderate pace compared to that of 2018 (+2.5%). Nevertheless, the increase in exports (+1.3%) exceeded that of imports (+0.4%), resulting in a positive net effect on real Gross domestic product (GDP).

Economic growth was unequal across Canada's provinces and territories and marked by slower growth in many regions. In 2019, the economy in most provinces and territories grew, except for the Northwest Territories (-8.0%) and Saskatchewan (-0.7 %).Footnote 1 Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador recorded the highest annual growth rates at 6.5%, 5.1% and 4.0%, respectively. The economies of Quebec and British Columbia grew at a lower rate, 2.7%, while those of Nova Scotia and Ontario grew by 2.4% and 2.1%, respectively. In the other provinces and territories, real economic growth was 1.2% in New Brunswick, 0.8% in Yukon and 0.6% in Manitoba. Alberta's economy grew slightly by 0.1% in 2019.

Canada's economic growth in 2019 was driven mainly by services-producing industries.Footnote 2 The services-producing industries recorded growth of 2.4%, the same rate as in 2018, with the strongest growth in:

- professional, scientific and technical services

- health care and social help, and

- real estate and rental and leasing

The goods-producing industries experienced weak growth of 0.2%, compared to 3.1% in 2018, with a slowdown observed in all the industries, except the agriculture sector.

In 2020, real GDP is expected to contract by around 5.4%. This will likely be attributable to the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on the Canadian economy.

Labour market context

In FY1920, employment in Canada increased by 1.6% over FY1819, with 303,100 jobs created on a net basis. This was the tenth consecutive annual increase and the largest increase since the 2008 to 2009 recession. The employment gains were concentrated in full-time employment opportunities and services-producing industries.

Most of the employment growth in FY1920 is attributable to full-time employment, with a 1.7% increase compared to FY1819. Part-time employment increased by 1.2% in FY1920. Employment growth was slightly higher among men (+1.7%) than for women (+1.5%). All age groups experienced an increase in employment, with the strongest growth rate for those 55 years of age and older (+3.8%). Employment for those aged 15 to 24 increased by 0.4% and, for those aged 25 to 54, by 1.2%. This reflects not only the aging of the workforce, but also the greater participation of older workers in the labour market.

Employment grew in both goods-producing (+0.4%) and services-producing industries (+2.0%) in FY1920. The goods-producing industries benefited from strong employment growth in construction (+32,800 or +2.3%). The increase in service-producing industries comes mainly from professional, scientific and technical services (+72,200 or +4.9%), as well as health care and social assistance (+85,500 or +3.5%).

The unemployment rate in Canada was 5.9% in FY1920, the same level as in FY1819. Provinces with a higher unemployment rate were Newfoundland and Labrador (12.3%), Prince Edward Island (8.4%), New Brunswick (8.0%), Nova Scotia (7.7%) and Alberta (7.3%). In the other provinces, the unemployment rates were lower than or equal to the national average in FY1920. The participation rate in Canada remained stable at 65.4%. The employment rate increased by 0.1 percentage point to 61.6%.

According to Statistics Canada's job vacancy surveyFootnote 3, there were approximately 541,500 vacancies in Canada in FY1920. This is a small increase of 3,700 (or +0.7%) compared to FY1819. The number of vacancies rose sharply in Quebec (+16,600 or +14.2%), while it dropped in Ontario (-6,500 or -3.1%), British Columbia (-6,300 or -5.9%) and Alberta (-4,200 or -7.5%).

An analysis by industry reveals that nearly 8 out of 10 job vacancies in Canada are in the services-producing industries.Footnote 4 The following industries registered the largest number of vacancies:

- accommodation and food services (69,000)

- health care and social assistance (67,300), and

- retail trade (63,600)

In the goods-producing industries, the highest numbers of vacancies were in manufacturing (46,300) and construction (37,800).

The vacancy rate, defined as the number of vacancies as a percentage of labour demand (the sum of employment and vacancies) was 3.2 in FY1920, a decrease of 0.1 percentage point compared to FY1819.Footnote 5 Yukon ranked first in Canada with a job vacancy rate of 5.4. British Columbia had the second highest vacancy rate (4.2) among the provinces and territories. In contrast, Newfoundland and Labrador had the lowest job vacancy rate at 2.3.

Table 1 — Selected Labour market indicators, Canada, FY1819 and FY1920

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Indicators | FY1819 | FY1920 | Year-over-year change in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Force | 19.8 | 20.1 | 1.6% |

| Employment | 18.7 | 19.0 | 1.6% |

| Unemployment | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2% |

- Source: Table 14-10-0017-01 Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group monthly unadjusted for seasonality.

| Indicators | FY1819 | FY1920 | Year-over-year change in point of percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Participation rate | 65.4 | 65.4 | 0.0 |

| Employment rate | 61.5 | 61.6 | 0.1 |

- Source: Table 14-10-0017-01 Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group monthly unadjusted for seasonality.

3.1.2 Main results

Decline in the number of EBSM clients and interventionsFootnote 6

In FY1920, provinces and territories served 630,425 clients under the Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), a decline of 6.0% compared to the previous year. The number of LMDA interventions delivered to clients decreased by 5.4% year-over-year, to a total of 968,632 interventions.

Terminology guide

A client is a person who has participated in programs or services funded by the LMDAs or by Indigenous organizations. Consult section 1.3 for details for client types.

An intervention is a discrete program or service in which a client participates. Consult section 1.4 and section 1.5 for the type of interventions available to clients.

Any reference to participants is the number of interventions, where information on designated groups is collected at the intervention level, rather than individual client.

Combined with programs and services delivered by Indigenous organizations through the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training (ISET) Program, a grand total of 652,267 EBSM clients were served (-6.2%), and 1, 010,565 EBSM interventions (-5.4%) were delivered in FY1920.

The overall intervention-to-client ratio was relatively stable at 1.55, compared to 1.54 in the previous year, as the number of interventions declined at a lower rate than the client total.

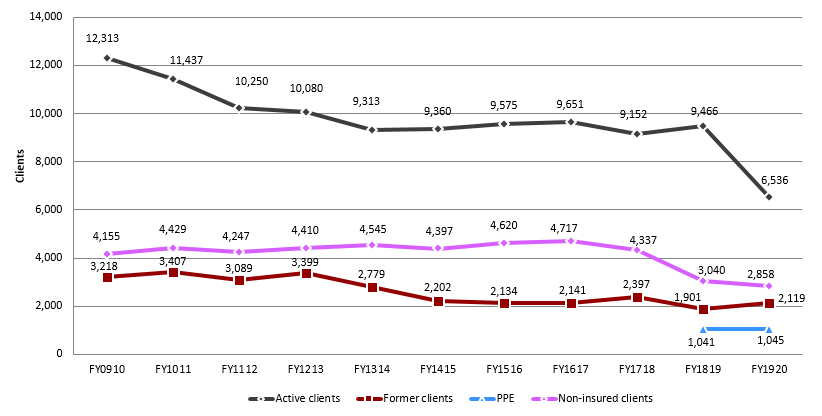

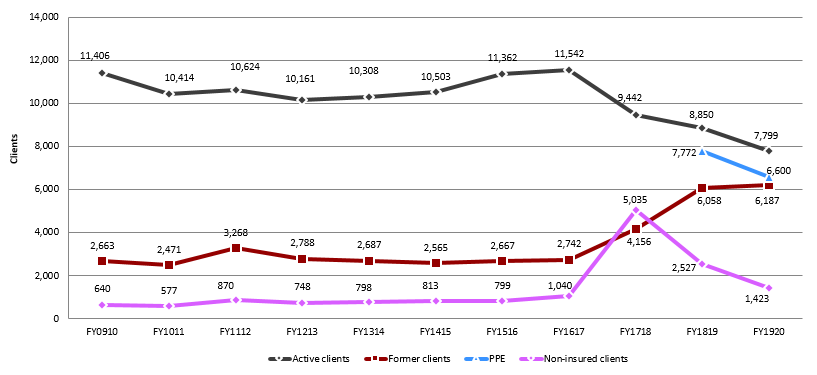

3.1.3 Client profile and participation

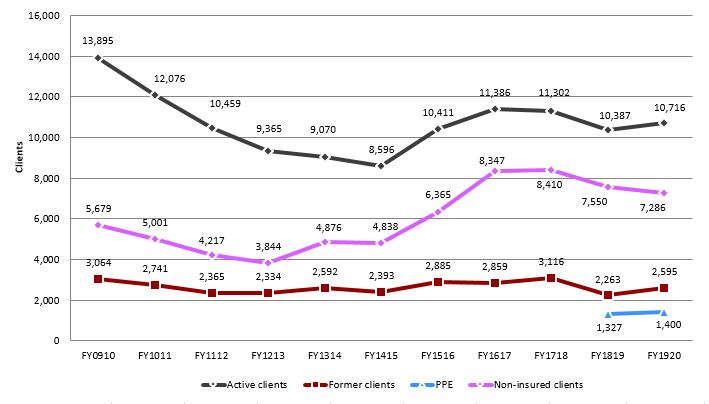

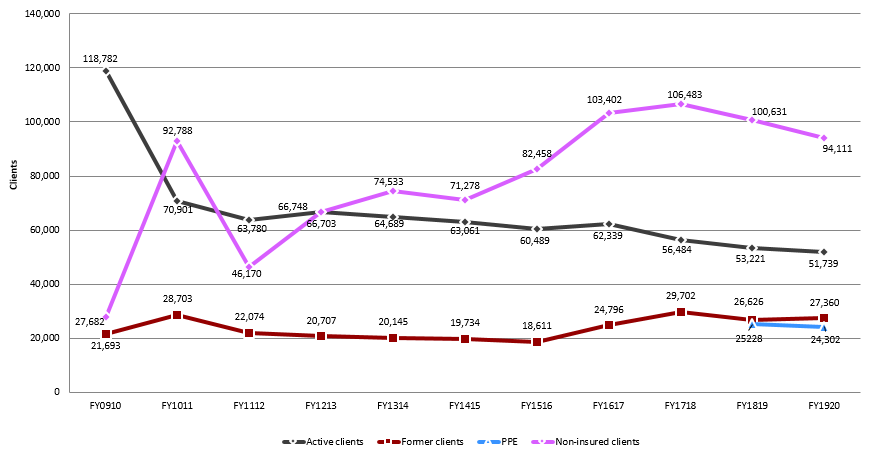

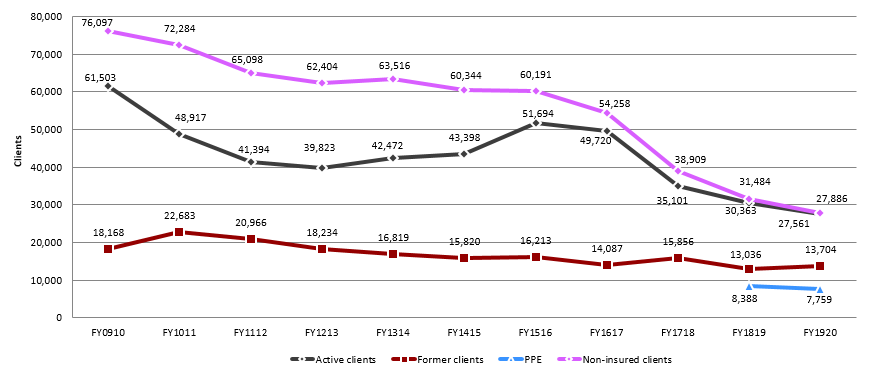

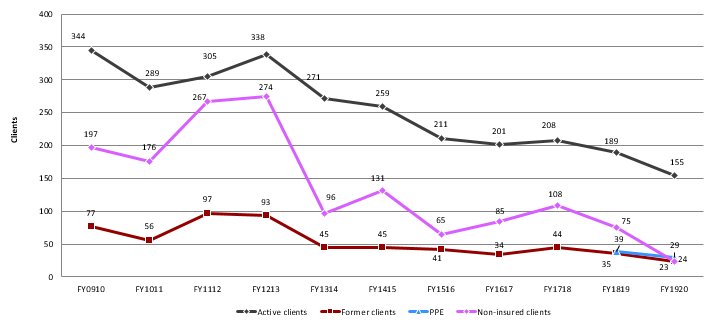

In FY1920, the total number of EBSM clients served declined by 6.2% year-over-year, with varying declines among the 3 traditional client groups. The number of active EI claimants declined by 8.4% year-over-year, to a total of 262,196; non-insured clients dropped by 9.0%, to a total of 218,350, while former EI claimant clients increased by 2.4%, to a total of 104,333. The number of clients served for the last group—Premiums Paid Eligible (PPE)—remained the newest group—Premiums Paid Eligible (PPE)— slightly decreased by 0.2% at 67,388 in FY1920.

As a share of all clients for FY1920, active EI claimants represented 40.2% of total clients, compared to 41.1% in FY1819, and non-insured (33.5%), compared to 34.5% in the previous year. The share of former EI claimants (16%) and PPE (10.3%) increased respectively by 1.4 and 0.6 percentage points, compared to FY1819.

Consult Table 2 for descriptions of the different client types.Footnote 7

Table 2 – Client type descriptions

For accessibility reasons, the information is presented in text format. Consult the PDF version for the table.

Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested assistance under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Typically, they have stronger and more recent job attachment. They tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to employment. Active claimants who are considered job-ready from an analytical point of view often seek out short-term interventions under EI Part II to find their next employment opportunity. Others require longer-term Employment Benefits to upgrade their skills, establish certification or refine their job search strategies.

Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the previous 5 years, or who began a parental or maternity claim in the last 5 years when they requested assistance under Part II. They are no longer in receipt of EI Part I benefits; however, they remain eligible for EI Part II under certain criteria.Footnote 8 Former claimants do not receive income support under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act while they complete an Employment Benefit intervention under EI Part II; however, they may receive Part II income support while completing training activities under their return-to-work action plan.

Premiums-paid Eligible are those who have made minimum Employment Insurance premium contributions above the premium refund threshold (that is $2,000 in earnings) in at least 5 of the last 10 years.

Non-insured clients are unemployed individuals who are neither active, former EI clients, nor PPE. Non-insured clients usually have little substantive or recent job attachment. They include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed without paid employment earnings. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EIPart II, they may access Employment Assistance Services.

Text description of Chart 1

| EBSM client type | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active claimants | 463,158 | 372,340 | 326,892 | 319,904 | 348,909 | 339,795 | 356,828 | 351,362 | 313,998 | 286,197 | 262,196 |

| Former claimants | 104,972 | 114,356 | 104,816 | 100,522 | 97,417 | 91,999 | 92,689 | 95,583 | 115,927 | 101,848 | 104,280 |

| PPE | 67,490 | 67,326 | |||||||||

| Non-insured clients | 209,020 | 269,350 | 214,587 | 241,834 | 264,716 | 257,665 | 284,607 | 304,927 | 285,733 | 240,075 | 218,316 |

Since FY0910, the number of EI active claimants under EI Part II has declined by 43.4%, while that of former EI claimants has remained somewhat stable (-0.6%), while non-insured clients increased by 4.5%. The drop in active EI claimants is largely attributable to the strong performance of Canada's labour market, resulting in an overall decline in EI program use among Canadians. In turn, provinces and territories focused on serving clients with weaker work attachment.

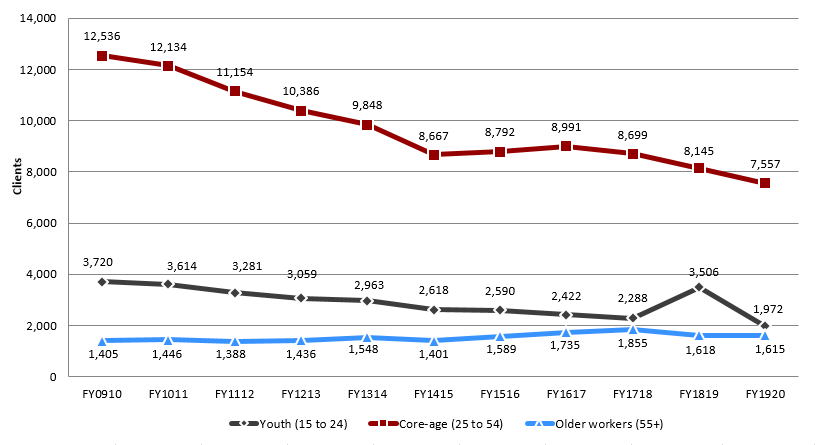

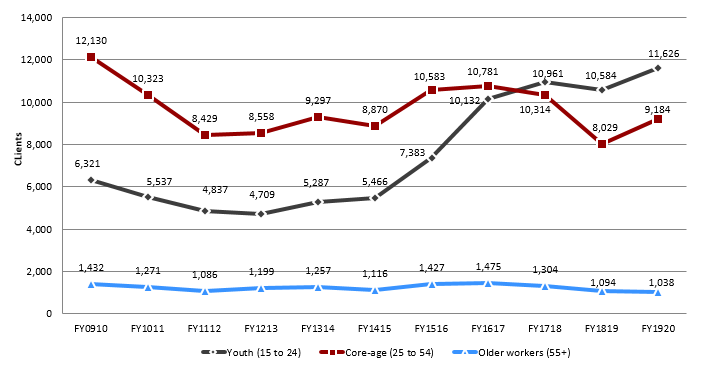

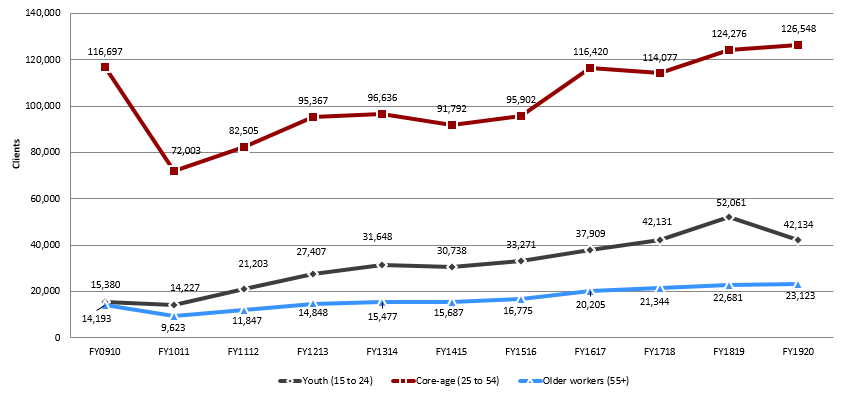

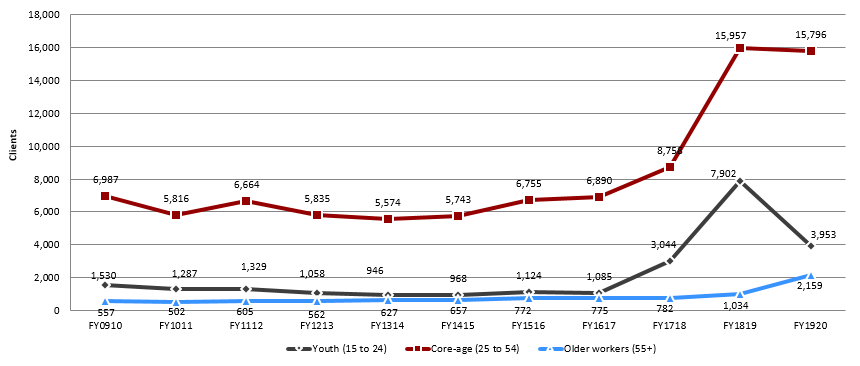

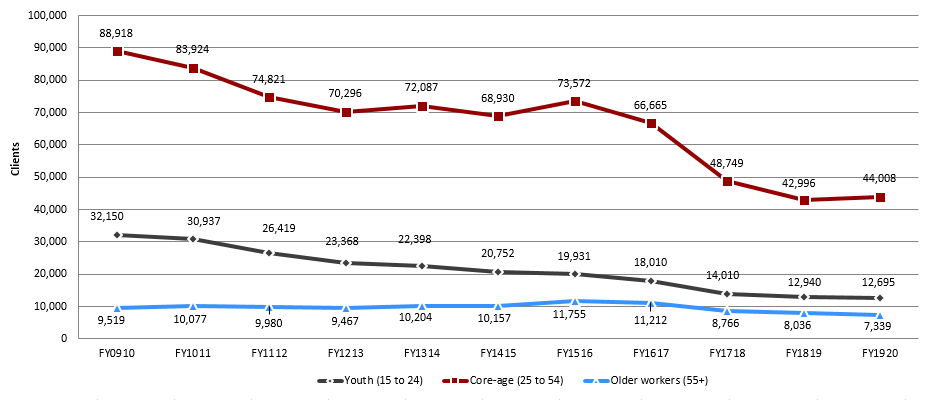

Age distributionFootnote 9

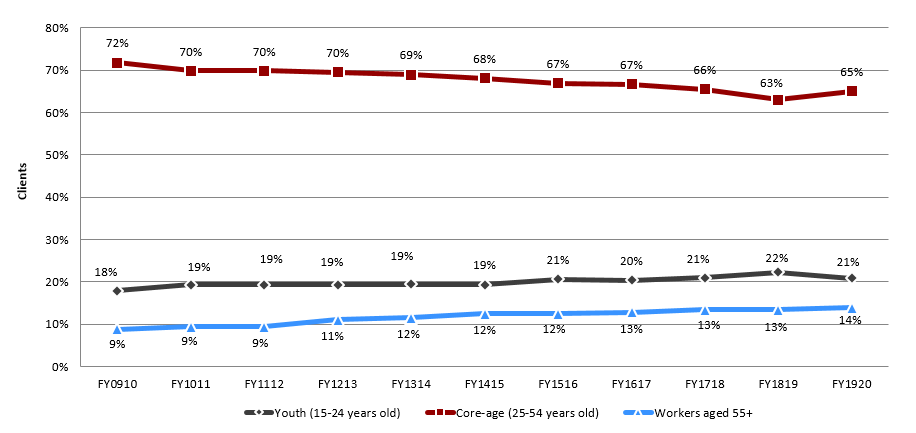

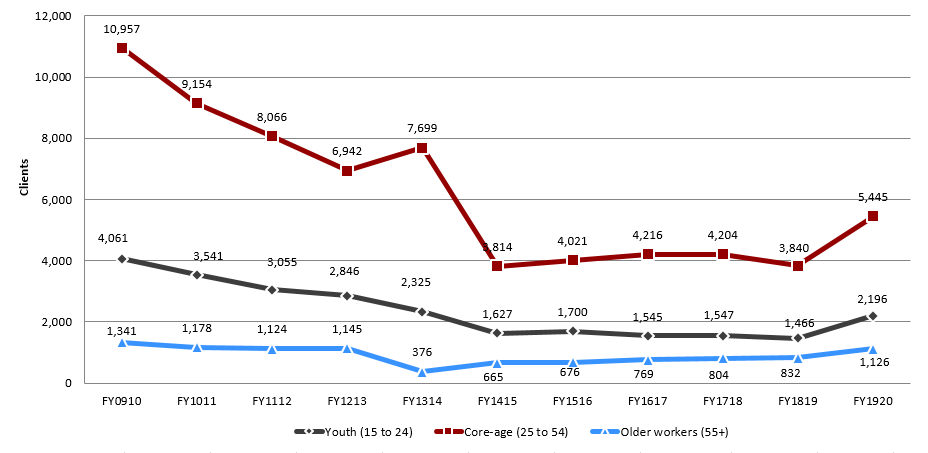

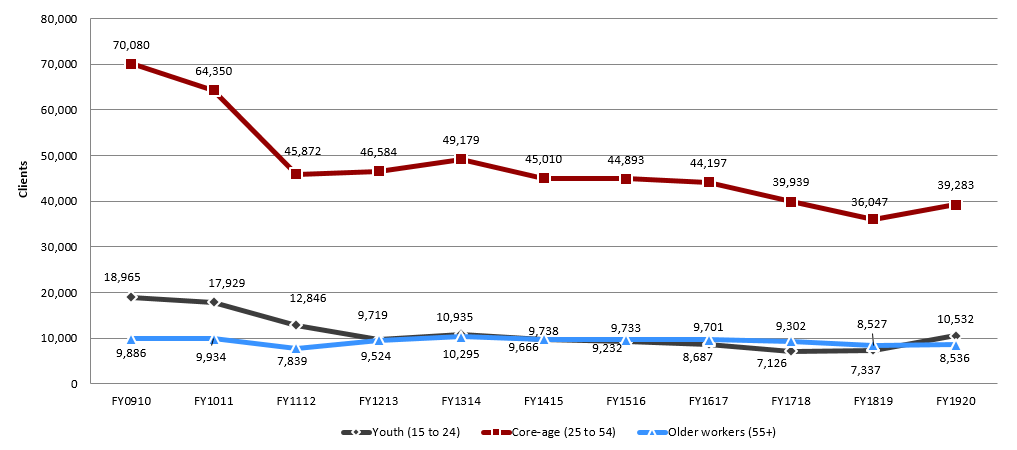

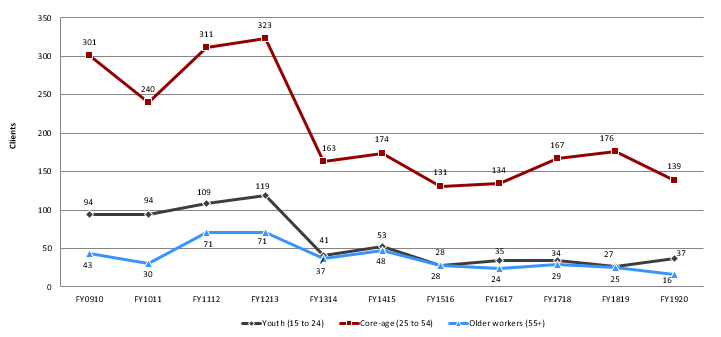

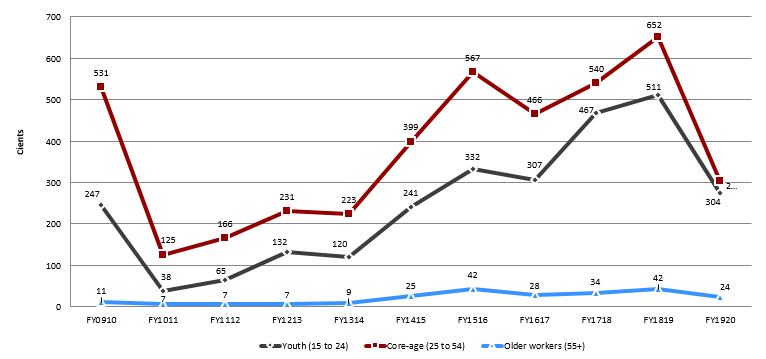

In FY1920, most EBSM clients were in their core working years (25 to 54 years old), totalling 405,644 individuals, or 65.1% of all clients. Youth – 15 to 24 years old – represented 20.9% of all clients (130,345), and clients aged 55 or older made up the remaining 13.9% (86,615 clients). Compared to FY1819, youth clients decreased significantly (-9.3%), while other categories of clients stayed relatively stable: clients aged 55 or older (+0.3%) and core-aged clients (-0.3%).

Text description of Chart 2

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15-24 years old) | 18% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 19% | 21% | 20% | 21% | 22% | 21% |

| Core-age (25-54 years old) | 72% | 70% | 70% | 70% | 69% | 68% | 67% | 67% | 66% | 63% | 65% |

| Workers aged 55+ | 9% | 9% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 12% | 13% | 13% | 13% | 14% |

In the context of an aging labour force, the number of EBSM clients aged 55 or older increased by 48.3% compared to FY0910 results. Clients aged 55 or older now represent 13.9% all total clients, compared to 8.8% a decade earlier.

Despite the decline in FY1920, in the past 10 years, youth participation in active labour market programming has also increased (+10.1%), as provinces and territories prioritized serving younger people to help counter the effects of an aging population, while developing and maintaining a competitive workforce. This age cohort now represents over 20.9% of all clients, compared to 17.9% 10 years earlier.

Given the growth of both youth and clients aged 55 or older, the number of core-age clients (25-54 years old) has declined (-14.5%) over the last 10 years. Core-age workers now represent 65.1% of all clients, compared to 71.8% in FY0910.

Designated groupsFootnote 10

In support of employment equity principles, ESDC collects information on the EBSM participation of women, Indigenous peoples, members of visible minority groups and persons with disabilities. As participantsFootnote 11 voluntarily self-identify, annual fluctuations may be due to changes in self-identification rates.

- Women participated in a total of 445,356 EBSM interventions in FY1920, a 6.2% decrease year-over-year (44.5% of all interventions delivered to Canadians, compared to 45.3% in FY1819). Women accessed predominately EAS interventions (84.2%); at a higher rate than men (75.3%). Women accessed 15.1% of the Employment Benefits delivered in FY1819. Among participants who were women, most were non-insured clients (38.2%), followed by active EI claimants (30.4%) and former EI claimants (19.6%). The remainder of women participants (11.8%) were under the PPE client category

- In FY1920, a total of 137,460 participants self-identified as persons with disabilities, a decrease of 2.5% year-over-year. Persons with disabilities participated in 13.7% of all interventions delivered in FY1920, a 0.3 percentage point increase year-over-year. The vast majority (82.1%) participated in an EAS intervention, compared to 17.9% who participated in Employment Benefits

- Indigenous peoples participated in 128,462 interventions in FY1920, representing an increase of 15.2% year-over-year. As a share of all ESBM interventions delivered in Canada, Indigenous peoples participated in 12.8% of the total (up from 10.6% of interventions in FY1819), including programming delivered through ISET. The vast majority of Indigenous participants (80.3%) participated in an EAS intervention, compared to 19.7% who participated in Employment Benefits

- Members of visible minority groups participated in 97,971 interventions in FY1920, dropping by 32.8% year-over-year. Among all interventions delivered in Canada, members of visible minority groups represented 9.8% of participants, compared to 7.0% in FY1819. The majority of interventions (87%) were EAS, compared to 13% for Employment Benefits

Official languages

To foster the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society, and to help ensure that labour market programs and services are delivered in both official languages, all LMDAs contain commitments by provinces and territories to have programs and services delivered in both official languages, where there is significant demand.

3.1.4 Interventions: Employment benefits

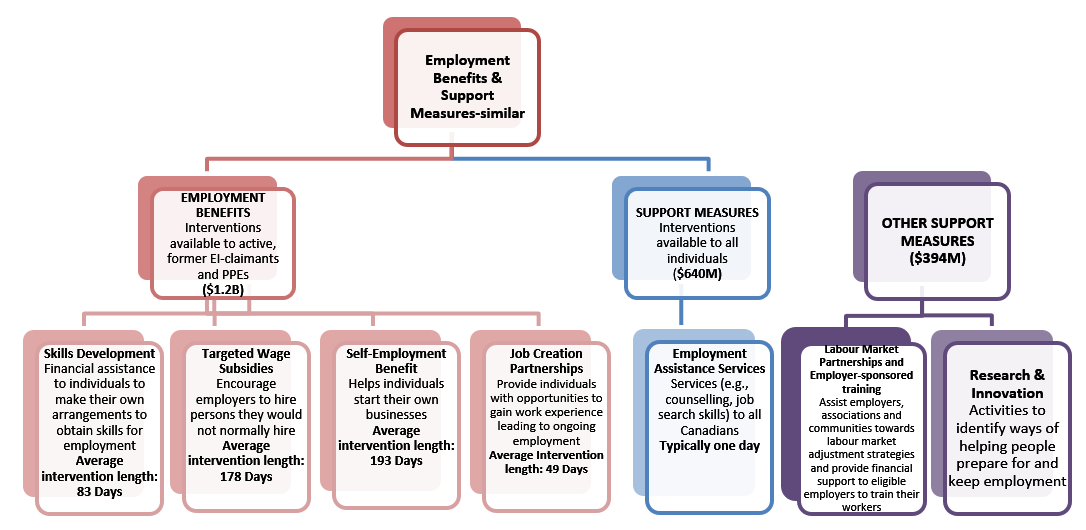

Employment Benefits are longer-term interventions focused on providing the skills or work experience required to regain employment. Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories can provide Employment Benefits similar to the following 6 benefit types outlined in the EI Act: Skills Development-Regular (SD-R); Skills Development-Apprentices (SD-A); Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS); Self-Employment (SE); Job Creation Partnerships (JCPs); and Targeted Earnings Supplements (TES).Footnote 12

In FY1920, Employment Benefit interventions totalled 197,907, a significant increase of 20.4% compared to the previous reporting period. With relatively strong labour market conditions, the rise of Employment Benefits suggests provinces and territories focused on longer-term training and skills development investments. The average length of an Employment Benefit intervention was 97 days in FY1920, considerably shorter than the average duration of 122 days observed in the previous year.

Text description of Table 3

Employment Benefits and Support Measures similar

- Employment benefits: Interventions available to active, former EI-claimants and PPEs ($1.2B):

- Skills Development: Financial assistance to individuals to make their own arrangements to obtain skills for employment. (Average intervention length: 83 Days)

- Targeted Wage Subsidies:Encourage employers to hire persons they would not normally hire (Average intervention length: 178 Days)

- Self-Employment benefit:Helps individuals start their own businesses. (Average intervention length: 193 Days)

- Job Creation Partnerships:Provide individuals with opportunities to gain work experience leading to ongoing employment. (Average Intervention length: 49 Days)

- Support measures:Interventions available to all individuals ($640M):

- Employment Assistance Services:Services (for example, counselling, job search skills) to all Canadians. (Typically one day)

- Other support measures ($0.3B): ($394M)

- Labour Market Partnershipsand Employer-sponsored training:Assist employers, associations and communities towards labour market adjustment strategies and provide financial support to eligible employers to train their workers

- Research & Innovation: Activities to identify ways of helping people prepare for and keep employment

SD-R interventions increased considerably, by 49.9%, to a total of 108,282, with the largest increases in Alberta (+192.0%), Manitoba (+195.9%) and British Columbia (+1,011.9%); while SD-A interventions decreased by 2.6%, to a total of 63,602 in FY1920. Combined, Skills Development interventions made up 86.9% of all Employment Benefits, compared to 83.6% in the previous year. Skills Development expenditures totalled $906.7 million, an increase of 3.3%, or $28.9 million, compared to FY1819.

In FY1920, TWS interventions declined by 19.5% year-over-year, to 15,137, and represented 7.6% of all Employment Benefits. Expenditures on TWS programming totalled $157.1 million, an increase of $14.8 million in spending compared to the previous fiscal year.

The number of SE interventions rose by 16.4%, to 5,792, with their shares among all Employment Benefits representing 2.9%. However, SE expenditures increased in FY1920; going from $60.6 million in FY1819, to $63.2 million in the current reporting year.

Overall, JCP interventions totalled 5,094, increasing 63.2% year-over-year, due to a significant increase in JCP programming in Manitoba (+1,046.7%). JCP expenditures jumped to $42.5 million, compared to $34.0 million in the previous year.

| Employment Benefit | Interventions | Share of Employment Benefits | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($000s) | Estimated cost per intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Wage Subsidies | 15,137 | 7.6% | -19.5% | $157.1 | $10,380 |

| Self-Employment | 5,792 | 2.9% | 16.4% | $63.2 | $10,911 |

| Job Creation Partnerships | 5,094 | 2.6% | 63.2% | $42.5 | $8,347 |

| Skills Development-Regular | 108,282 | 54.7% | 49.9% | $906.7 | $5,275 |

| Skills Development-Apprentices | 63,602 | 32.1% | -2.6% | ||

| Canada | 197,907 | 100% | +20.4% | $1,169.5 | $5,910 |

3.1.5 Interventions: Support measures

Part II of the Employment Insurance Act authorizes 3 support measures: Employment Assistance Services (EAS), Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs) and Research and Innovation (R&I). Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories deliver these measures at regional and local levels, while ESDC retains responsibility for pan-Canadian delivery of LMPs and R&I (consult section 4.1: Pan-Canadian Activities and the National Employment Service). However, LMPs and R&I are generally not associated with direct client services, so counts on participants or interventions are not available. The EAS component of Support Measures provides a full range of self-help and assisted services, such as support in determining career objectives through employment counselling, improving job search techniques, completing a return-to-work action plan and accessing labour market information in support of career choices.

Employment Assistance ServicesFootnote 13

Employment Assistance Services support client to prepare for, find and keep employment, through various services (such as, career advice and employment counselling, job search assistance, or Information on the labour market and education/training opportunities). EAS interventions provide crucial support to those who have been absent from the labour market for an extensive period or who have low job attachment. They may also support new immigrants or young people who are entering the Canadian labour market for the first time. These interventions are reported in 1 of the 3 following categories: Employment Services, Group Services, or Individual Counselling.

In FY1920, a total of 770,725 EAS interventions were delivered, a decrease of 10.3% year-over-year. Total expenditures on EAS were 639.5 million, compared to $705.4 million in the previous reporting year.

Individual Counselling is particularly important when supporting clients who face barriers to employment, and often need action plans as a pathway to Employment Benefits. In FY1920, with an increase of 21.8% year-over-year to a total of 408,261 interventions, Individual Counselling was the most common EAS intervention type, accounting for 53.0% of all EAS interventions (compared to 39% in FY1819). Employment Services interventions was the second most common EAS intervention type, accounting for 45.7% of all EAS interventions in FY1920, compared to 58.8% a year earlier. A total of 352,142 Employment Services interventions were delivered, a decrease of 30.3% year-over-year, with largest decreases in Alberta (-72.4%) and Saskatchewan (-100%). Group Services dropped by 44.8%, for a total of 10,322 interventions delivered. In turn, the share of Group Services among all EAS-type interventions dropped to 1.3%, compared to 2.2% in the previous year.

Other support measures

The Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs) measure facilitates collaboration between employers, employees and employer associations, as well as community groups and communities, to develop solutions to labour force imbalances, such as persistent high unemployment or skill shortages. Under LMPs, employer-sponsored training includes assistance to employers to support approved training activities for employees in order to maintain their employment. This may include employees affected by technological or structural changes in the economy. In FY1920, LMPs expenditures totalled $276.9 million, compared to $253.4 million in the previous year.

Research and Innovation (R&I) initiatives identify better ways of helping people prepare for, return to or maintain employment and participate productively in the labour force. In FY1920, R&I expenditures totalled $117.3 million, compared to $94 million in the previous year.

Table 5 – Support measures and other support measures, Canada, FY1920

For accessibility reasons, the information is presented in text format. Consult the PDF version for the table.

| Employment Assistance Service* | Interventions | Share of employment support measures | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($000s) | Estimated cost per intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment services | 352,139 | 45.7% | -30.3% | n/a | n/a |

| Group services | 10,322 | 1.3% | -44.8% | n/a | n/a |

| Individual counselling | 408,261 | 53.0% | 21.8% | n/a | n/a |

| Total Employment Assistance Services | 770,722 | 100.0% | -10.3% | $705.4 | $821 |

- *Expenditures for Employment Assistance Services are reported at the aggregate level by most provinces and territories.

| Other support measures | Interventions | Share of employment support measures | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($000s) | Estimated cost per intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Market Partnerships** | n/a | n/a | n/a | $253.4 | n/a |

| Research and innovation | n/a | n/a | n/a | $94.0 | n/a |

| Canada | 770,722 | 100% | -10.3% | $1,052.8 | n/a |

**Expenditures for Labour Market Partnerships includes employer-sponsored training.

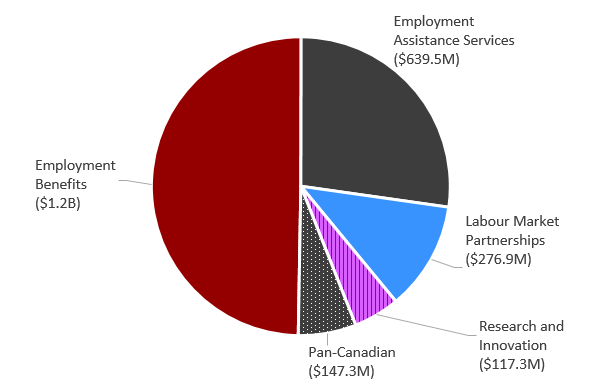

3.1.6 Expenditures

Total expenditures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act were $2.35 billion in FY1920, which included EBSM programming, and pan-Canadian activities. This represented an increase of 1.9% compared to the previous year, driven by additional incremental LMDA funding under Budget 2017 and new available funding under the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training program.

Under the LMDAs, Employment Benefits remained the largest investment, at $1.17 billion, representing more than half of expenditures by provinces and territories. Compared to FY1819, spending on Employment Benefits increased by nearly $55 million (+4.9%). Expenditures on Employment Assistance Services declined by nearly 66 million (-9.3%) to a total of $639.5 million.

Text description of Chart 3

| Chart 5: FY 1920 spending chart | Value | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 1,169,631 | 50% |

| Employment Assistance Services | 639,527 | 27% |

| Labour Market Partnerships | 276,921 | 12% |

| Research and Innovation | 117,288 | 5% |

| Pan-Canadian | 147,252 | 6% |

| n/a | 2,350,620 | n/a |

Expenditures towards LMPs and R&I measures increased, going from $347.4 million in FY1819, to $394.2 million in FY1920.

Pan-Canadian expenditures increased significantly (+5.9%), increasing from $139.0 million in FY1819 to $147.3 million in FY1920. Consult Section 4 of this chapter for details on Pan-Canadian activities.

Targeted Measures under LMDAs in FY1920

In FY1920, the Government of Canada made available additional time-limited targeted funding, under the LMDAs, to support workers and communities affected by duties and tariffs imposed by the United States on steel and aluminum products. In addition, Budget 2018 announced additional funding to assist workers in seasonal industries over 2 years, which started in FY1819. For FY1920, $45.5 million was made available to provinces and territories under 2 measures: $20.5M for workers in seasonal industries and $25M for workers affected by the steel and aluminum trade dispute. Provinces and territories accessed roughly $41.8 million of the funding.

Jurisdictions invested the additional funding in existing and new programming. For example, Newfoundland and Labrador utilized the seasonal worker funding ($1.6 million) for the Impacted Fish Plant Worker Program. This targeted program focused on creating short-term employment for workers from fish plants deemed impacted by the downturn in the fishing sector.

Under the LMDA-funded Sector Council Program, the Nova Scotia Tourism Human Resource Sector Council and the Nova Scotia Fisheries Human Resource Sector Council used the targeted funding ($1.6 million) to provide support to seasonal industry sectors for recruitment, attraction, retention, and training of workers.

In FY1920, Ontario invested targeted funding in programs such as Adjustment Advisory Program, SkillsAdvance Ontario and Pre-Apprenticeship to support workers in seasonal industries and those workers affected by the steel and aluminum trade dispute. The funding involved 24 projects, assisted more than 500 employers and served over 2,000 clients.

In Quebec, the additional targeted funding for workers in seasonal industries ($8 million) supported a pilot project for extending periods of hiring seasonal workers in companies with training and income support once their EI benefits had expired.

Additional information on provincial and territorial activities is available in Section 3.2 of this chapter.

3.1.7 Key Performance IndicatorsFootnote 14

FY1920 Employment benefits and Support Measures key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| EI Active, Former, and Premiums-Paid eligible (LMDA) | Non-Insured clients (LMDA) | Pan-Canadian1 |

|---|---|---|

| 412,075 | 218,350 | 21,842 |

| Active claimants | Former claimants | PPEs | Non-Insured | Youth clients (15–24)2 | Core age workers (25–54)2 | Clients aged 55 or older2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40.40% | 14.30% | 10.70% | 34.60% | 20.90% | 65.10% | 13.90% |

| Interventions | FY1920 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment benefits | 197,907 | 20.40% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 770,725 | 10.30% |

| Pan-Canadian | 41,933 | 5.80% |

| FY1920 | Year-over-year change (p.p.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment benefits | 20.40% | 4.3 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 79.60% | 4.3 |

| FY1920 ($ million) | Year-over-year change | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $1,169.50 | 4.90% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $639.50 | 9.30% |

| LMPs and R&I | $394.20 | 13.50% |

| Pan-Canadian | $147.30 | 5.90% |

| Total expenditures | $2,350.50 | 1.90% |

| Indicator | Total | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Active claimants served | 262,196 | 8.40% |

| Returns to employment | 194,120 | 1.80% |

| Estimated unpaid benefits ($ Million) | $1,054.34 | 1.50% |

- 1 EI Part II Pan-Canadian services to individuals are through the ISET Program.

- 2 Age distribution does not equal 100%, as the "unknown" category is not reported here. Date of birth is not collected for clients in SD-Apprentices and Group Services.

- 3 Totals may not add up exactly due to rounding; accounting adjustments are not included.

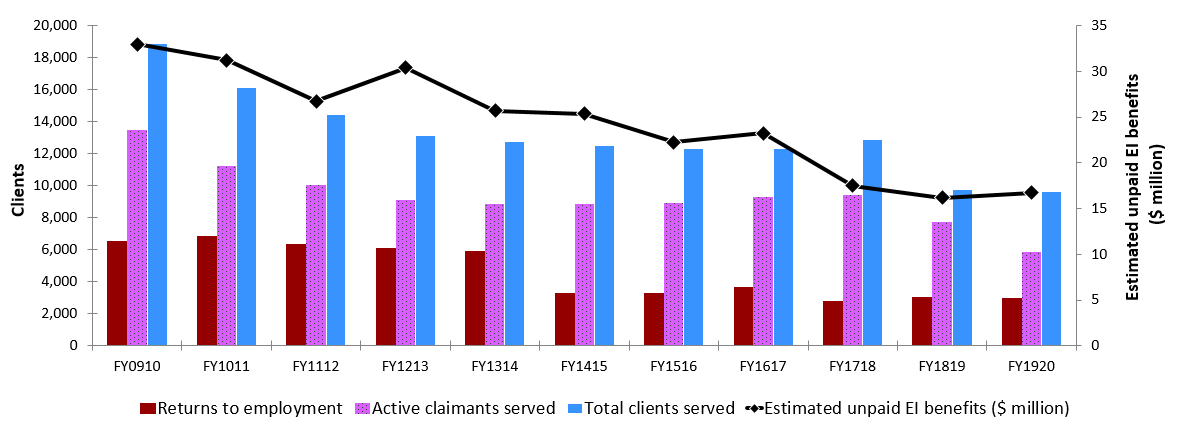

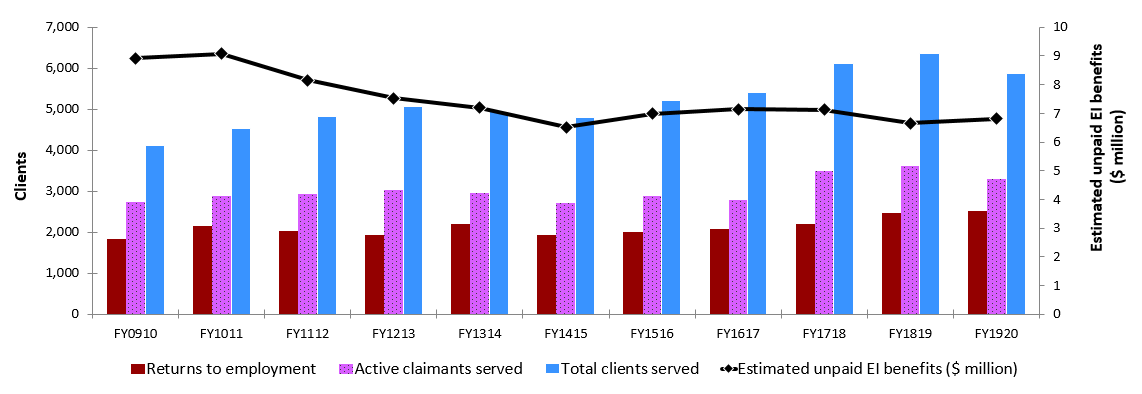

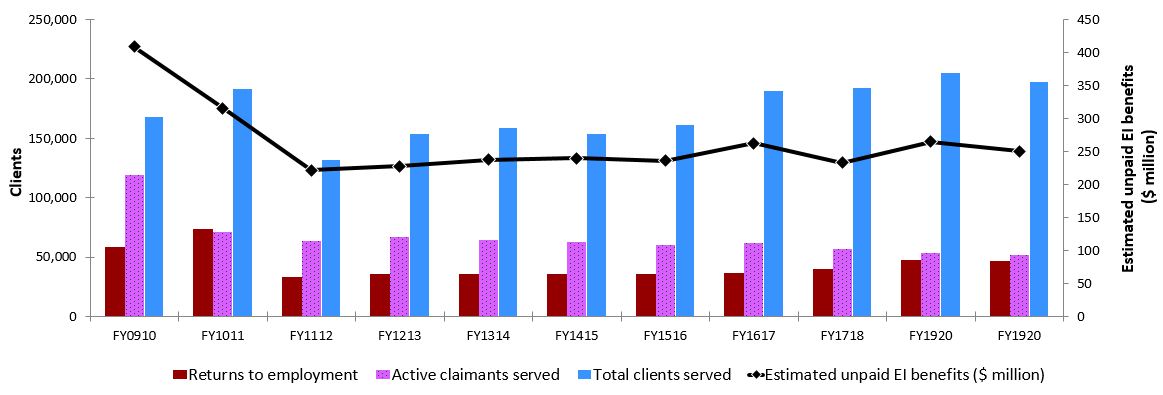

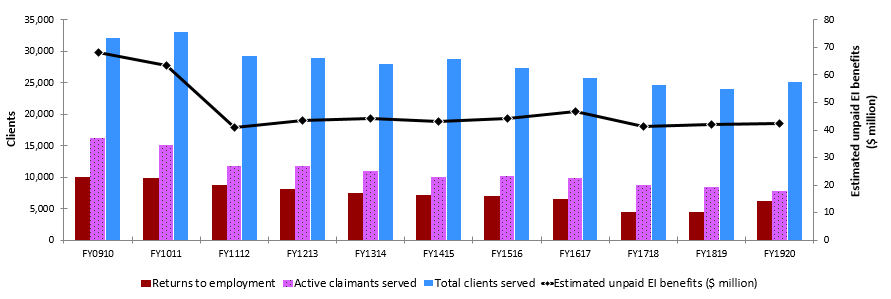

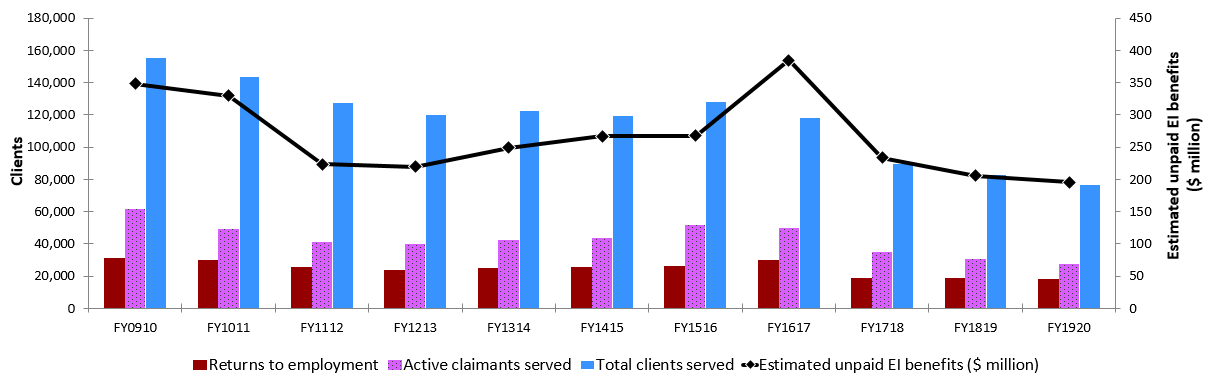

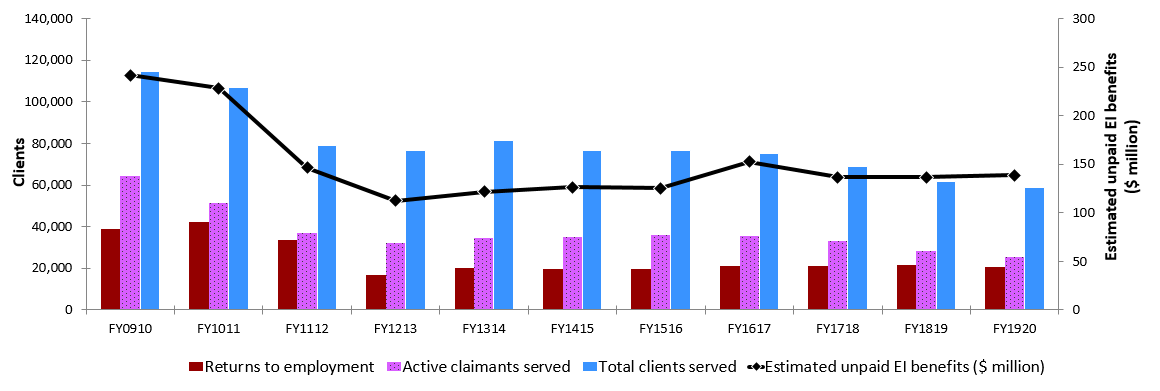

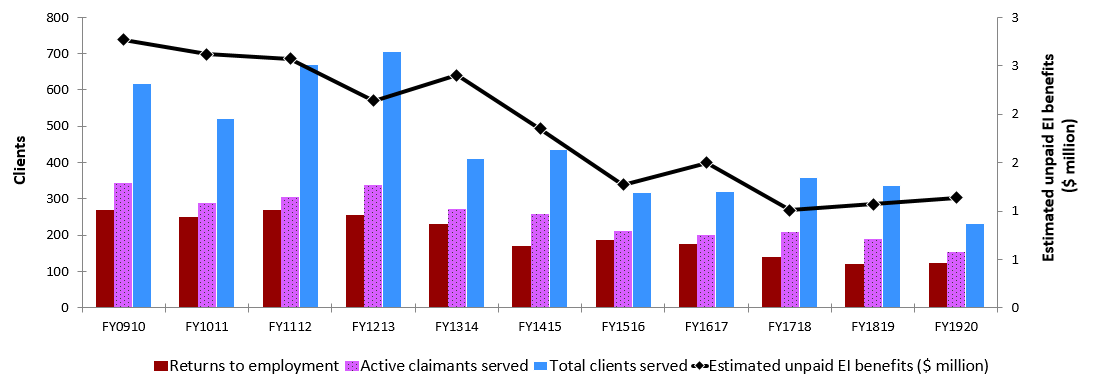

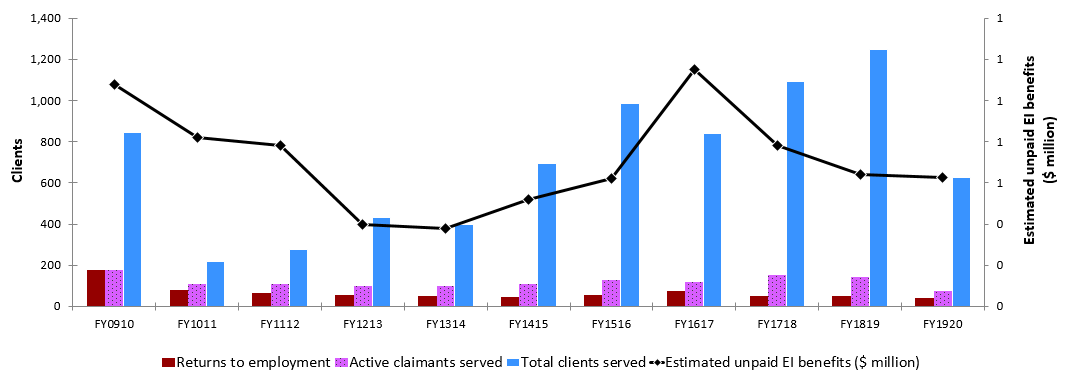

ESDC monitors the results of EBSM-similar programming delivered by provinces and territories through 3 key performance indicators:

- the number of active EI claimants servedFootnote 15

- the number of EI clients who return to employment following an intervention,Footnote 16 and

- the amount of unpaid EI Part I benefits resulting from returns to employment

In the context of improving labour market and economic conditions in FY1920 throughout most parts of Canada, the number of active EI claimants served (262,196) dropped by 8.4% year-over-year. Returns to work increased by 1.8% year-over-year, with a total of 194,120 clients finding employment within 6 months of completing their interventions. Stemming from the decline in active EI claimants, unpaid EI Part I benefits totalled $1.054 billion, going down by 1.5% compared to the previous year.

Table 5 presents supplementary performance indicators at the national and provincial/territorial level, contextualized with labour market aggregates. Since multiple factors can influence results at the individual, jurisdictional and national level, these indicators cannot be solely attributed to the LMDAs.

At the national level, 67.8% of active EI claimants began their first LMDA-funded intervention within 12 weeks after their Benefit Commencement Period (BCP). Compared to FY1819, this is an increase of 5.2 percentage points, where 62.6% of active claimants began within 12 weeks that year. At the provincial/territorial level, most jurisdictions experienced an increase, as well, with results ranging from 79.2% in Quebec, to 35.8% in Newfoundland and Labrador. In FY1920, Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia continued refining their use of the Targeting, Referral and Feedback (TRF) tool, helping provinces and territories identify EI applicants, according to local labour market needs and available EI Part II employment programming. ESDC is working closely with the remaining 10 provinces and territories to onboard to TRF.

In FY1920, Canada's returns to work following interventions among active EI claimants, expressed as a proportion of the country's labour force, was 1.0%. Quebec, Saskatchewan and 3 Atlantic provinces (Newfoundland & Labrador, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick) were above the national average. At the same time, unpaid EI regular benefits stemming from returns to work, expressed as a proportion of total EI regular benefits paid, was 9.5% at the national level. Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia had higher proportions than the national figure. Similar to recent years, Quebec registered above the national average for both of these ratios. This suggests an effective and efficient balance between returning clients to work as soon as possible, while ensuring the necessary active employment services for employment success over a mid- to long-term horizon.

| Province / Territory | Unemployment rate | Job vacancy rate | EI Active Claimants (%) beginning EI Part II within 12 Weeks following their Part I benefit period commencement * | Returns to work among Active EI clients from EBSM Interventions, as a proportion of the labour force | Estimated unpaid EI regular benefits resulting from EBSM interventions, as a proportion of Part I Regular Benefits Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 12.3 | 2.3 | 35.8% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 8.4 | 3.1 | 60.5% | 2.9% | 4.4% |

| Nova Scotia | 7.7 | 2.9 | 51.0% | 0.8% | 3.9% |

| New Brunswick | 8.0 | 3.1 | 58.3% | 2.3% | 3.9% |

| Quebec | 5.3 | 3.5 | 79.2% | 1.7% | 11.5% |

| Ontario | 5.7 | 3.1 | 61.6% | 0.6% | 8.3% |

| Manitoba | 5.4 | 2.6 | 44.1% | 0.9% | 11.4% |

| Saskatchewan | 5.9 | 2.4 | 46.2% | 1.3% | 11.9% |

| Alberta | 7.3 | 2.6 | 68.5% | 0.7% | 14.5% |

| British Columbia | 5.0 | 4.2 | 65.7% | 0.7% | 13.0% |

| Northwest Territories | 8.2 | 2.8 | 56.0% | 0.8% | 7.3% |

| Yukon | 3.5 | 5.4 | 55.5% | 0.5% | 6.6% |

| Nunavut | 13.7 | 3.3 | 53.4% | 0.3% | 5.2% |

| Canada | 5.9 | 3.2 | 67.8% | 1.0% | 9.5% |

- Source: Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months and Table 14-10-0325-01, Job vacancies, payroll employees, job vacancy rate, and average offered hourly wage by provinces and territories, quarterly, unadjusted for seasonality and EI Administrative Data.

- *This includes a small percentage of clients who began EI Part II programming up to 2 weeks prior to their Part I Benefit Period Commencement. SD-A participants and those who were non-insured participants were excluded, if they had received EAS in the previous year.

3.2 Provincial and Territorial EBSM Activities

In this section:

- 3.2.1 Context

- 3.2.2 Newfoundland and Labrador

- 3.2.3 Prince Edward Island

- 3.2.4 Nova Scotia

- 3.2.5 New Brunswick

- 3.2.6 Québec

- 3.2.7 Ontario

- 3.2.8 Manitoba

- 3.2.9 Saskatchewan

- 3.2.10 Alberta

- 3.2.11 British Columbia

- 3.2.12 Northwest Territories

- 3.2.13 Yukon

- 3.2.14 Nunavut

This section analyzes the provincial and territorial economic environment and EBSM-similar activities in FY1920. It links trends in clients served, interventions and expenditures to local labour market conditions, as well as employment programming priorities.

3.2.1 Context

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories receive funding to support the delivery of programs and services, similar to the EBSMs established under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act.Footnote 17 To address unique labour market challenges, provinces and territories deliver employment programming under LMDAs, which were individually negotiated with the Government of Canada. Provinces and territories design and deliver all EI-funded active employment programming, except for pan-Canadian activities, discussed in Section 4 of this chapter.

Broad-based consultations were held in FY1617 with provinces, territories and stakeholders to identify ways to improve the labour market transfer agreements and guide future investments to strengthen labour market programming. Comments received indicated a desire for agreements to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of employers and Canadians, especially underrepresented groups in the workforce.

Budget 2017 announced new measures to rationalize and expand the existing bilateral labour market transfer agreements with provinces and territories, including the LMDAs. This included amending the EI Act to expand eligibility for Employment Benefits to include unemployed individuals who have made minimum Employment Insurance premium contributions in at least 5 of the last 10 years. In addition, eligibility for Employment Assistance Services was broadened to include both the unemployed and employed. Provinces and territories were also provided with increased flexibility to support employer sponsored training under the Labour Market Partnerships Support Measure. These changes took effect on April 1, 2018 and were reflected in amending agreements signed with provinces and territories. These amendments can be found on the LMDA website.

In addition, the amended LMDAs require provinces and territories to consult with employer and employee organizations, as well as stakeholders representing Official Language Minority Communities, as part of their annual planning process. Provinces and territories are required to include information on this engagement, including related outcomes in their annual deliverables.

Budget 2017 also announced an additional $1.8 billion investment in the LMDAs over 6 years (2017-2018 to 2022-2023), to help more Canadians access EI-funded skills training and employment supports.

Overall, Canada's economy and labour market performed well in FY1920, contributing to a decline in the number of clients served and LMDA-funded interventions delivered in most provinces and territories.

Despite varying economic and labour market conditions throughout Canada, all jurisdictions prioritized improvements to the labour market attachment of underrepresented groups, such as persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, youth, and older workers; as well as assuring employers have access to a skilled workforce. An aging workforce and out-migration remain a particular labour market challenges for Atlantic Canada, where the provinces worked with communities and regional stakeholders to ensure labour market programming responds to the demographic pressures. The Managing for Results section for each provincial and territorial summary highlights innovative approaches to improve outcomes for clients.

These include:

- better employer engagement in setting priorities and design

- improved strategies to deliver active employment supports earlier for EI claimants, and

- innovative approaches in some jurisdictions to Research and Innovation support measures

3.2.2 Newfoundland and Labrador

In 2019, Newfoundland and Labrador recorded 1 of the strongest real GDP growth rate (+4.0%) among all territories and provinces, after contracting by 3.5% in 2018. In 2020, the Province's economy is expected to have shrunk by 7.7%, as the COVID-19 crisis and the sharp drop in oil prices have led to serious setbacks across the Province's main industries.

Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Insured clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

8396 |

1253 |

| Intervention type | FY1920 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 9,303 | 28.4% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 15,354 | 12.2% |

| Intervention type | FY1920 | Year-over-year change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 37.7% | 3.1 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 62.3% | 3.1 |

| Total expenditures | FY1920 ($ million) | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $110.5 | 2.5% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $12.6 | 25.4% |

| LMP and R&I | $12.5 | 18.0% |

| Total expenditures* | $135.6 | 1.2% |

| FY1819 | FY1920 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $16.16 | $16.74 | 3.6% |

- * Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

In FY1920, the Province's labour market conditions remained stable, with employment slightly dropping, by 0.4% (-1,000). The unemployment rate was 12.3%, 0.1 percentage point lower than a year earlier, as the Province's labour force shrank by 4,200, or 1.6%. The overall labour market participate rate slid by 0.9 percentage points to 57.6%. The goods-producing industries experienced slight employment decline (-700; -1.6%) while employment in the services-producing industries remained relatively stable (-200;-0.1%). While utilities (-400; -12.2%) and construction (-500; -2.7%) were the most affected sectors in the goods-producing industries, sectors such as finance, insurance, real estate and leasing (-700; -9.9%); professional, scientific and technical services (-1,200; -11.6%); and, health care and social assistance (-1,200; -2.9%) slowed down significantly in the services-producing industries. Positive results were recorded in business, building and other support services (+1,200; +18.1%); accommodation and food services (+1,000; +6.1%); and, other services (+1,700; +17.7%).

In FY1920, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, access to employment assistance was traditionally via a combination of online, telephone and in-person delivery structure. However, the primary engagement tool for individuals was in-person services. The pandemic shut down brought forth challenges in program and service delivery, with the suspension of in-person access for the public and working from home arrangements for staff. All program delivery models had to be reviewed and revised to accommodate an individual's ability to access a complete, alternative, on-line delivery process for both internal and external stakeholders. The transition included online forms, policy and procedural changes, and a virtual approach to case management. Notably, post-secondary training institutions in Newfoundland and Labrador were nimble to transition to online courses. This permitted many individuals to continue studies towards their employment goals during these unprecedented times. However, it also presented challenges, as businesses were not permitted to operate and employees were unable to work.

COVID-19 has affected many key industries in Newfoundland and Labrador, with significant impacts not yet fully understood. These disruptions continue to impact the oil and gas, hospitality and retail sectors. In some cases, the impacts are compounding existing drivers of change, such as the use of digital technologies, the automated creation and application of technology to monitor and control the production as well as the delivery of products and services, outsourcing and offshoring. These effects are reshaping the landscape of skills demands, with potential far-reaching consequences for workers, employers and the overall labour market. While minimal impacts to employment programming plans and priorities were observed in FY1920, future editions of this report will have more details about the effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

3.2.2.1 Managing for results

In 2019 to 2020, Newfoundland and Labrador made significant improvements in capturing data from community partners, to improve reporting and the assessment of results. The Province worked with community organizations to align the Accountability Resource Management System (ARMS) with the required fields outlined in the new performance measurement strategy developed with the Government of Canada. This has permitted a better, more regular and consistent data sharing with the federal government. As well, it has allowed the Province's community partners to demonstrate a larger reach in supporting individuals in employment as well as training programs and services.

3.2.2.2 Clients, interventions and expenditures

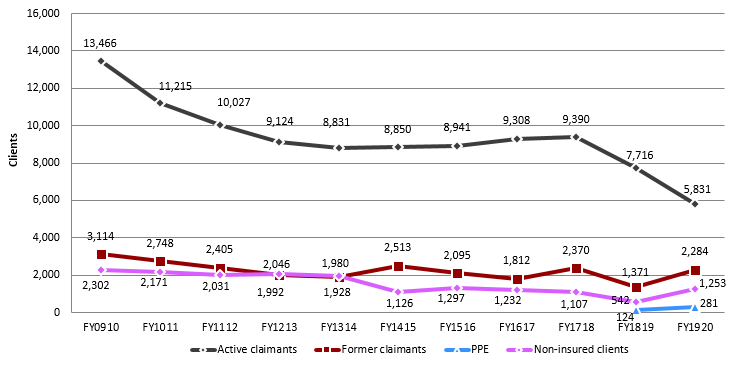

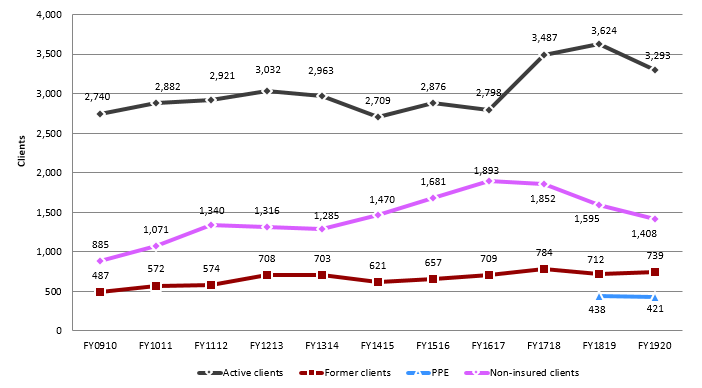

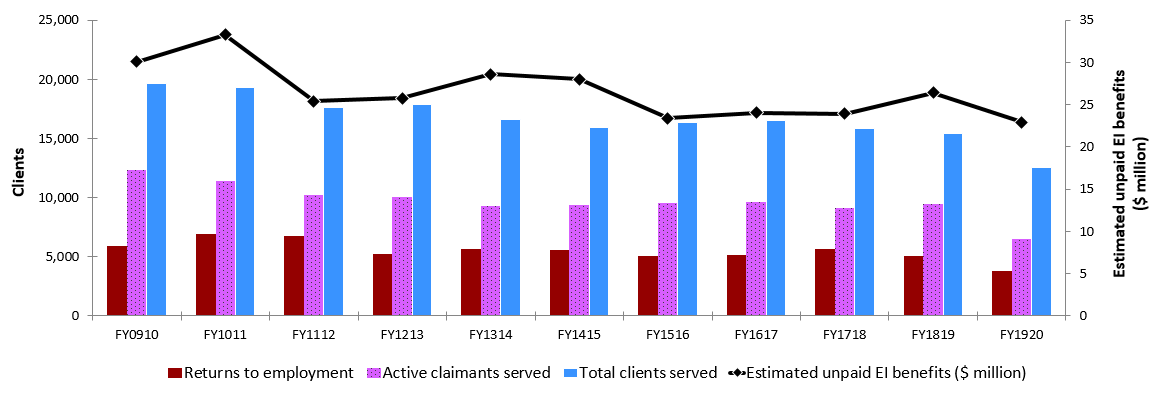

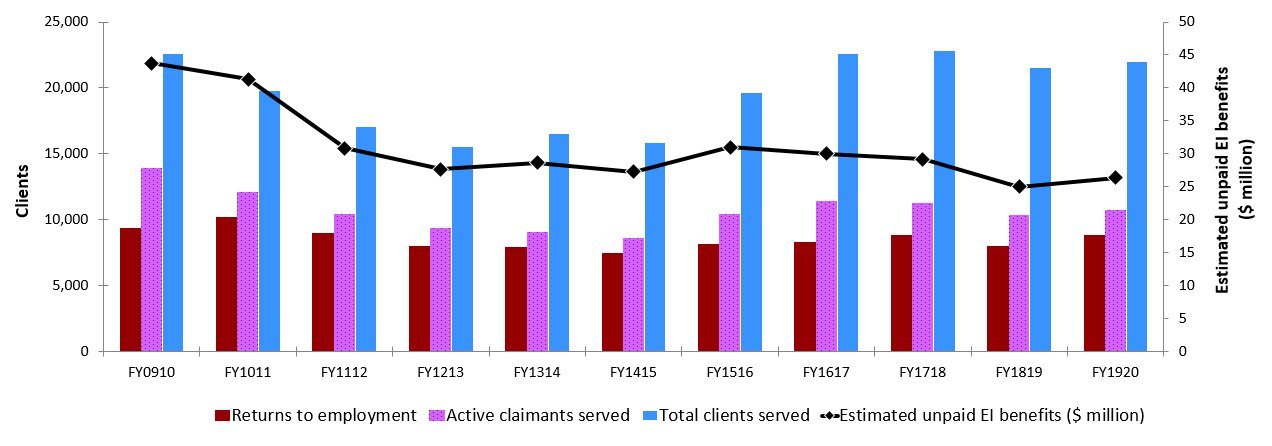

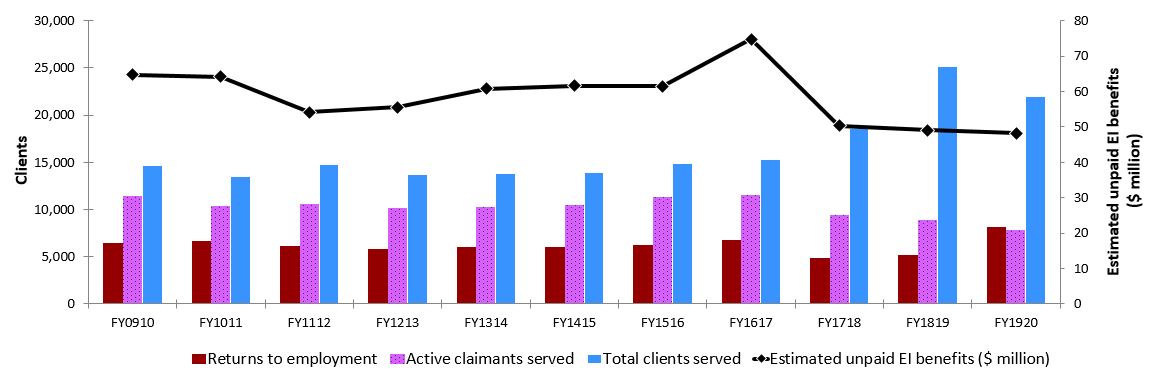

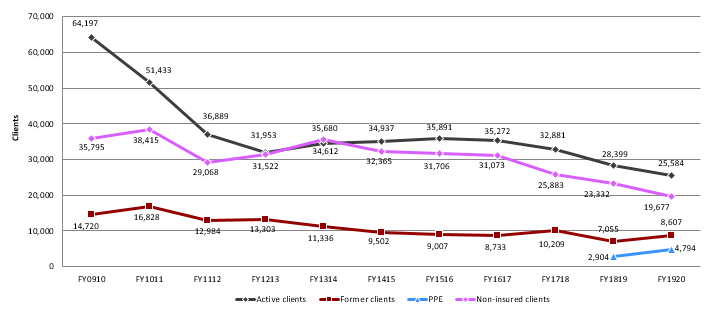

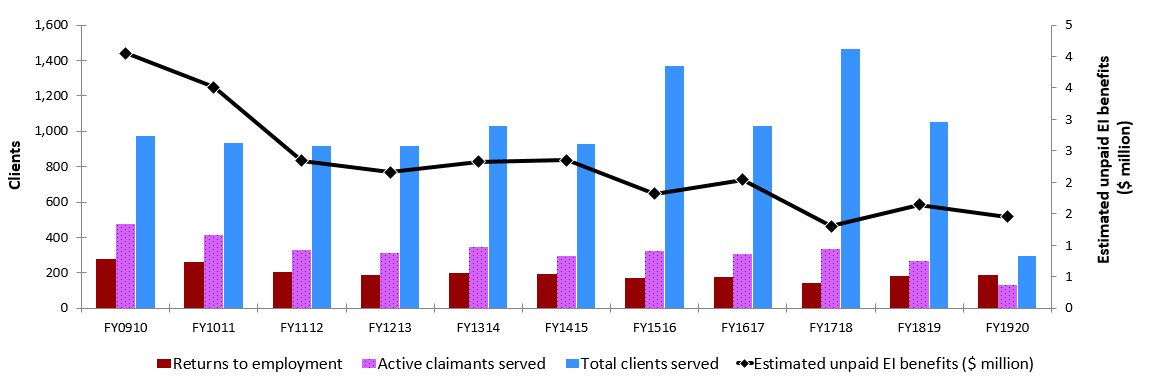

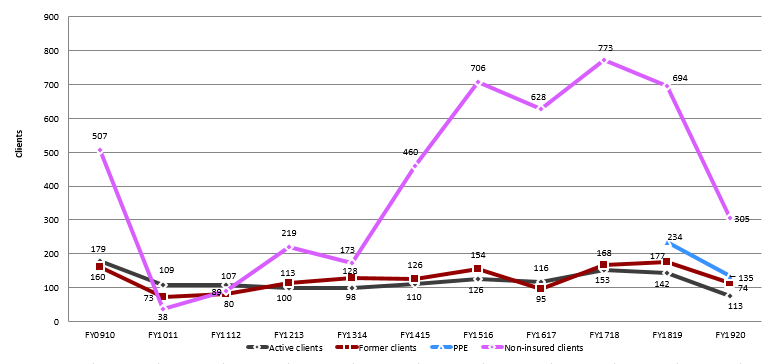

For a second consecutive year, the total number of clients served in Newfoundland and Labrador declined, reaching 9,649 (-1.1%) in FY1920. While the number of active clients dropped by 24.4% (or 1,885) to 5,831, that of former clients (2,284), PPE (281), and non-insured clients (1,253) grew up by 66.6%, 126.6%, and 131.2%, respectively.

PPE, the new client type as of FY1819, accounted for 2.9% for all clients served, representing a year-over-year increase of 1.6 percentage point. The share of active clients fell from 79.1% to 60.4 % of all clients served, that of former clients and non-insured advanced from 14.1% to 23.7%, and 5.6% to 13.0%, respectively.

In FY1920, Newfoundland and Labrador delivered 24,657 (+17.8% year over year) EBSM-similar interventions. Support Measures (62.3%) represented the most delivered interventions, and the proportion of Employment Benefits was 37.7% of all interventions. Compared to the previous year, 2,990 insured clients returned to work after participating in an EBSM-similar program, a 2.1% year-over-year decrease. Unpaid EI benefits increased by 3.6% to $16.74 million.

EBSM total expenditures advanced by 4.0% to $135.6 million, including $9.9 million from the Province's share of the additional $250.0 million LMDA investment announced in Budget 2017, as well as funding measures provided to support workers in seasonal industries ($1.6 million) and those affected by trade disputes in the steel and aluminum industries ($500,000).

Because of the additional funding provided as part of Budget 2017, Newfoundland and Labrador strategically invested funds to support individuals and employers in accessing training and employment services. Some examples of this investment include:

- to address labour market needs, the College of the North Atlantic was supported to develop new offerings of the Practical Nursing program and increase intake within existing programs. As a result, approximately 116 individuals will participate in FY2021

- to assist with government's strategic action plans to enhance the quality of the provincial Early Childhood Education (ECE) workforce and increase educational qualifications in the field, the College of the North Atlantic was supported to address the current waitlist for ECE, as well as to find ways of increasing access to ECE online. Approximately 120 individuals were supported to further develop their ECE credentials

- led by the Community Sector Council NL, the Tapping the Untapped Potential in the Community Sector project will help address the significant labour market issues relevant to community-based, non-profit supply, as well as demand regarding employment potential and growth. Funding was provided for a project to focus on planning for attraction, retention, succession and growth of the paid and unpaid labour force

- Newfoundland and Labrador, in partnership with TradesNL and the Innu Nation, established the Trades NL Indigenous Apprentice Office. This office will recruit, promote, support and advance the economic and professional growth of Indigenous populations of Newfoundland and Labrador within the skilled trades, with an emphasis on trades and Red Seal occupations

Newfoundland and Labrador utilized the seasonal worker funding to respond to circumstances such as industry closures and downsizing (fish plant closures), through the provision of LMDA programs such as skills development and wage subsidy supports, to assist those impacted in seeking meaningful employment.

- The Impacted Fish Plant Worker Program is an example. The targeted program is focused on creating short-term employment for workers, from fish plants deemed impacted by the downturn in the fishing sector. The Fish Plant Worker Program is administered by Municipal Affairs and Environment (MAE), and impacted fish plants are identified by the Department of Fisheries and Land Resources (FLR). Once a fish plant is identified by FLR, MAE will make contact with the plant to obtain a plant worker list, as well as reach out to the community in which the plant is located to secure a sponsor. If another sponsor is needed to accommodate the workers of the impacted plant, then MAE will reach out again and pursue projects in other communities tied to those impacted workers

- As part of The Way Forward, industry and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador collaborated, through the Cabinet Committee on Jobs, to support economic growth and foster private sector job creation. As part of this work, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador and Newfoundland Aquaculture Industry Association Inc. jointly developed the Aquaculture Sector Work Plan, which includes actions that each of the partners will take, to achieve the collective goal of growing the aquaculture industry and stimulating new private sector employment. The Province utilized seasonal funding to create awareness, understanding and interest to promote recruitment to the industry

In FY1920, Newfoundland and Labrador supported individuals who were directly or indirectly affected by the United States' decision to impose tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum products. To provide displaced workers with the training and employment supports they need to successfully transition to new jobs, the province supported 31 wages subsidy plans for employers to hire steel and aluminum workers, as well as provided skills training to an additional 185 individuals.

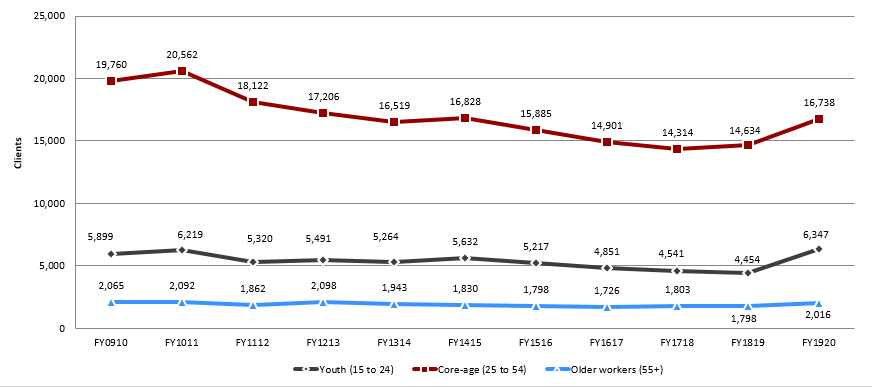

Text description of Chart 4

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active claimants | 13,466 | 11,215 | 10,027 | 9,124 | 8,831 | 8,850 | 8,941 | 9,308 | 9,390 | 7,716 | 5,831 |

| Former claimants | 3,114 | 2,748 | 2,405 | 1,992 | 1,928 | 2,513 | 2,095 | 1,812 | 2,370 | 1,371 | 2,284 |

| PPE | 124 | 281 | |||||||||

| Non-insured clients | 2,302 | 2,171 | 2,031 | 2,046 | 1,980 | 1,126 | 1,297 | 1,232 | 1,107 | 542 | 1,253 |

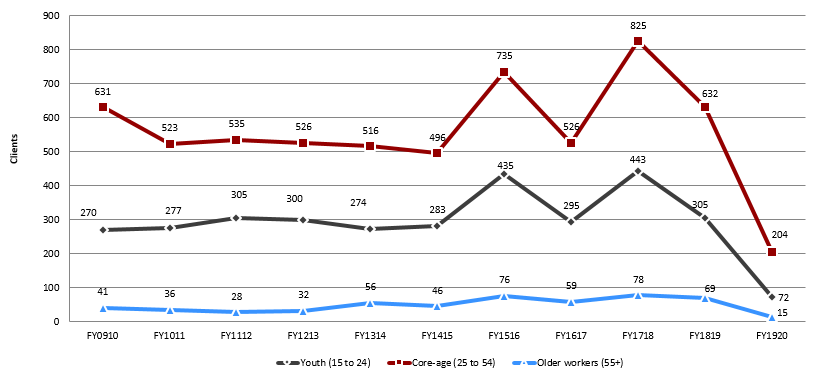

Text description of Chart 5

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24) | 4,061 | 3,541 | 3,055 | 2,846 | 2,325 | 1,627 | 1,700 | 1,545 | 1,547 | 1,466 | 2,196 |

| Core-age (25 to 54) | 10,957 | 9,154 | 8,066 | 6,942 | 7,699 | 3,814 | 4,021 | 4,216 | 4,204 | 3,840 | 5,445 |

| Older workers (55+) | 1,341 | 1,178 | 1,124 | 1,145 | 376 | 665 | 676 | 769 | 804 | 832 | 1,126 |

Text description of Chart 6

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Returns to employment | 6,526 | 6,857 | 6,335 | 6,114 | 5,918 | 3,298 | 3,306 | 3,696 | 2,795 | 3,055 | 2,990 |

| Active claimants served | 13,466 | 11,215 | 10,027 | 9,124 | 8,831 | 8,850 | 8,941 | 9,308 | 9,390 | 7,716 | 5,831 |

| Total clients served | 18,882 | 16,134 | 14,463 | 13,162 | 12,739 | 12,489 | 12,333 | 12,352 | 12,867 | 9,753 | 9,649 |

| Estimated unpaid EI benefits ($ million) | $32.94 | $31.20 | $26.71 | $30.42 | $25.69 | $25.35 | $22.25 | $23.23 | $17.47 | $16.16 | $16.74 |

Table 7 – Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM-similar programming, FY1920

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Employment Benefits | Program name | Interventions | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD-R | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 5,064 | 56.10% | 83,908 |

| SD-A | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 1,355 | -12.40% | |

| TWS | Newfoundland and Labrador Wage Subsidies | 926 | 15.50% | 7,746 |

| SE | Newfoundland and Labrador Self-Employment Assistance | 402 | 50.60% | 7,451 |

| JCP | Newfoundland and Labrador Job Creation Partnerships | 1,556 | 12.30% | 11,390 |

| Support Measures | Program name | Interventions | Year-over-year change | Expenditures ($ 000s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAS | Newfoundland and Labrador Employment Assistance Services | 15,354 | 12.20% | 12,612 |

| LMP | Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 8,447 |

| R&I | Research and Innovation | n/a | n/a | 4,030 |

3.2.2.3 Employment benefits

In FY1920, total number of Employment Benefit interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador jumped by 28.4%, to 9,303. While TWS (+124; +15.5%), SE (+135; +50.6%), JCP (+170; +12.3%) and SD-R (+1,820; +56.1%) increased, SD-A decreased by 12.4% (-192). Total expenditures towards Employment Benefits ($110.5 million) dropped by 2.5%.

Highlights of the Skills Development Employment Benefit

Client Profile: "Susan"

Susan was 56 years old when she requested assistance with job search and career planning. Upon assessment, it was determined that she had multiple barriers to employment. Susan had a grade 8 education and was unable to secure full-time sustainable employment. She began the employment planning process and enrolled in an Adult Basic Education (ABE) program, with a goal to obtain a career in the medical profession. Although the ABE program presented many challenges for this adult learner, she progressed and successfully graduated.

In January of 2020, at the age of 61, Susan successfully completed the Fast Track Acupuncture Diploma Program at the Canadian College of Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine, in Bedford Nova Scotia. She graduated with Honours and has had several job offers upon graduation. Susan started her own practice in January 2020.

In a follow up note to her Case Manager, she wrote:

Thank you so much for everything you have done for me. I am going to have an amazing career and love helping others on their journey to wellness. You know you are doing well in this field when you receive referrals from other patients. Thank you again for believing in me and giving me this fabulous opportunity to learn and succeed in a whole new career.

Client Profile: "Carol"

Carol was 45 years old when she requested assistance in securing employment. She had a history of low paying positions and found it difficult to compete for jobs in today's labour market. Carol had a learning disability, had not graduated high school, and reported that she faced many challenges in the regular school system and had dropped out. Her short-term goal was to successfully complete her high school education, and later complete a Personal Care Attendant or Practical Nursing program.

Carol's Case Manager worked collaboratively with her to get an educational assessment completed. This assessment recommended supportive services, such as tutoring, to assist her to be successful in completing her ABE program - in less weeks than recommended by the educational institution!

Carol went on to complete a Personal Care Attendant program, which resulted in full-time employment with Western Health.

3.2.2.4 Support measures: EAS

EAS interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador rose from 13,687, in FY1819, to 15,354 in FY1920, a 12.2% year-over-year growth. While Employment services (+870; +17.1%) and Individual Counselling (+4,399; +88.1%) interventions increased, Group Services (-3,602; -100.0%) declined compared to the previous fiscal year. Total EAS expenditures advanced by 25.4% to $12.6 million.

3.2.2.5 Other support measures: LMP and R&I

In FY1920, Newfoundland and Labrador's total funding for LMP and R&I reached $12.5 million (+18.0%). While funding towards LMP ($8.4 million) increased by 13.4%, R&I funding ($4.0 million) increased by 29.0%.

Activities offered under the Employer-Sponsored Training component of Labour Market Partnerships

As part of the expanded eligibility included in the amendment to the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador LMDA signed in 2018, the province has increased flexibility to support employer-sponsored training under Labour Market Partnerships. In FY1920, 2 employers availed of this programming:

- Labrador Gem Seafood Incorporated had 40 fish plant workers in Ramea, trained in sea urchin processing, with the assistance of a consultant from Japan. Employees received an introduction to the process flow for this specialized production, followed by the provision of various tools used to generate the best quality product and actual processing. Employees were given work assignments and the instructors monitored, to determine their effectiveness in each role. A daily performance sheet was used to evaluate progress in the position. At the end of the training, a report was issued for each employee, and management decided on the most effective positioning for each person in the process flow. This training will help extend the operating season for this seafood processing facility, thereby decreasing the employee's reliance on EI benefits

- Dallas Mercer Consulting Inc. (DMC) supports hundreds of employers across Canada, by managing workers' compensation and sick leave claims. Due to a skills shortage in the field of expertise, DMC is implementing a coaching and shadowing program. DMC anticipates it will take 12 months for an inexperienced new employee to be fully trained and productive, as a DMC Disability Manager, with continued coaching as needed

During this training process, trainees will be exposed to different approaches to manage sick leave and WorkplaceNL cases, as well as collaborating on unique or challenging cases through reviews. Classroom time will be required, to learn and study all provincial legislation as it relates to workers' compensation, policies, procedures, as well as case studies to understand application.

Each trainee will get experiential learning to:

- review Workers' Compensation Monthly Cost Statements

- understand how to develop relationships with and the value of client interaction

- learn how to interact with workers and obtain answers to questions, and,

- understand what to look for when doing a case review, and where to focus attention to obtain desired outcome

This training began January 2020 and ended in December 2020.

Results/lessons learned for any research and innovation projects that concluded in FY1920.

Although most of the projects funded through the Workforce Innovation Centre were still ongoing at the time this report was made public, it is anticipated the findings from research projects will inform innovative models and best practices for labour market programs and services. Examples of promising practices include:

- evidence for Community Employment Services – Collective Interchange Cooperative (CIC) and Canadian Career Development Foundation (CCDF); $314,732

- led by CIC, in partnership with CCDF, this 3-year project is being implemented across employment support agencies within the Avalon Region of Newfoundland and Labrador. This project aims to answer 2 research questions:

- What employment support interventions will produce the best results given clients existing strengths and weaknesses?

- How can the data collected be used to create system efficiencies and ensure that services meet the client's needs, which would result in outcomes that are beneficial to clients and funders?

Through a survey of career practitioners, it was determined that an enhancement of the Performance Recording Instrument for Meaningful Evaluation (PRIME) interactive software will give employment service providers a mapping of tailored interventions and outcomes. The PRIME 2.0 system will enable meaningful recording and reporting of progress in vital client centered characteristics, which will support the evaluation of client progress and interventions.

The enhancement of PRIME 2.0 is currently being piloted by community agencies in the Avalon Region. This learning may be applied to various career and employment services contexts from community services, post-secondary, to government service delivery. Because of the research completed to date, many of the agencies will continue to use the PRIME 2.0 after the project is completed. It is anticipated the software will be expanded to other jurisdictions.

Improving Psychological Health and Safety in Health Care Workers through Technology Based Support: Project Plan – Eastern Health; $443,000

Eastern Health, in partnership with IBM, is undertaking a pilot project to test ways to improve mental health and safety through technology-based support. The project will help determine if technology based support increases employee knowledge and uptake of psychological support services. It is anticipated that this will also improve employee wellness factors and organizational healthy workplace indicators. This 3-year project will involve the development, implementation and evaluation of application based technology. This will incorporate internal and external supports to the organization, as well as a built in peer "chat" function, that will allow employees to gain timely and appropriate support, as well as information about services and supports available to them.

To date, the Employee Virtual Assistant (EVA) software was developed and launched prior to the COVID pandemic. As a first test, EVA assessed the impacts of the virus on Eastern Health workers. There is significant interest in early adoption of the tool beyond Eastern Heath, to other Health Boards in the province.

3.2.3 Prince Edward Island

In 2019, Prince Edward Island registered, for a second consecutive year, the highest real GDP growth rate among all provinces, with 5.1%, which exceeded the national growth rate (+1.9%). According to Canadian major banks forecasts, the Province's real GDP growth has contracted by 4.8% in 2020.

Prince Edward Island: EBSM key facts

For accessibility reasons, the table has been simplified. Consult the PDF version for the full table.

| Insured clients | Non-insured clients |

|---|---|

4,453 |

1,408  |

Total interventions: 10,387

| Intervention type | FY1920 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 3,525 | 0.014 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 6,862 | 0.004  |

| Intervention type | FY1920 | Year-over-year change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 33.9% | 0.4 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 66.1% | 0.4  |

| Intervention type | FY1920 | Year-over-year change (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 33.9% | 0.4 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 66.1% | 0.4  |

| FY1819 | FY1920 | Year-over-year change |

|---|---|---|

| $6.66 | $6.82 | 2% |

- * Prince Edward Island invested $160,464 of its total allocation towards administration costs, representing almost 6.6% of the Budget 2017 additional funding the Province received in FY1920.

- ** Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

Similar to FY1819, labour market conditions in Prince Edward Island remained solid in FY1920. On a net basis, employment increased by 3,000 (+3.9%) year-over-year, almost entirely in full-time positions, which advanced from 65,100 to 67,700, while part-time positions advanced from 11,900 to 12,300. The Province's unemployment rate fell to 8.4%, representing the lowest rate since comparable data became available in FY7677. Services-producing sector (+2,500; +4.3%) provided the most new employment positions on a net basis, with major gains in public administration (+1,100; +15.4%); professional, scientific and technical services (+200; +5.2%); business, building and other support services (+200; 8.0%); educational services (+200; +4.5%); other services (+300; +10.1%); and, health care and social assistance (+800; +8.1%). Information, culture and recreation (-400; -16.3%); transportation and warehousing (-100; -3.2%); and, accommodation and food services (-100; -1.2%) were the only industries on the services side that experienced net losses. Employment in the goods-producing sector (+500; +2.6%) occurred mainly in construction (+900; +14.9%) and agriculture (+400; +8.8%). This was somewhat counterbalanced by losses in forestry, fishing, mining, oil and gas (-500; -17.9%) as well as in manufacturing (-200; -3.5%).

In FY1920, a shortage of workers in numerous industries represented the main challenge facing Prince Edward Island's labour market. In particular, rural areas experienced an acute demographic decline, affecting local economies. For FY1920, the Province developed key priorities to:

- help individuals develop the necessary skills to prepare for, find and keep employment

- assist persons with disabilities to obtain sustainable employment

- facilitate employers access to a skilled and diverse workforce, and

- ensure communities in Prince Edward Island are able to respond effectively to labour market opportunities and challenges

Besides this, in order to stimulate population growth, the government has committed to increase investments in rural settlement supports to help newcomers better integrate into smaller communities.

3.2.3.1 Managing for Results

In FY1920, PEI invested in substantial IT system updates, to improve the quantity and quality of data collected from clients, programs and outcomes from its LMDA-funded programs.

As part of the new performance measurement strategy developed with the Government of Canada, Prince Edward Island redesigned the Action Plan screens in its client management system. Beginning with the needs assessment, PEI replaced free text collection of skills, employment barriers and personal barriers with extensive pre-defined lists. The Province designed robust reports to support this data collection, allowing for better analysis and understanding of the barriers affecting clients, as well as the barriers leading to specific programming decisions.

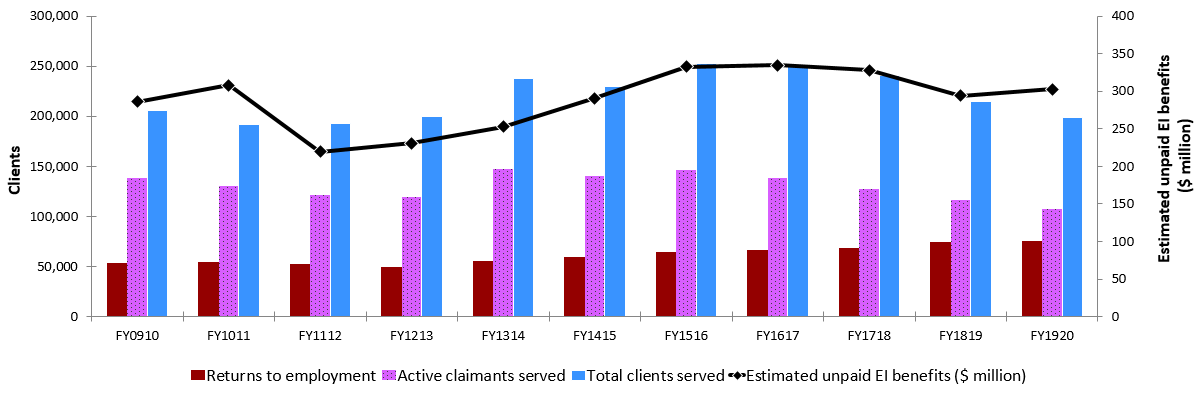

3.2.3.2 Clients, Interventions and Expenditures

After 4 consecutive years of growth, the number of clients served in Prince Edward Island in FY1920 dropped by 8.0%, to 5,861. With the exception of former claimants, which increased by 3.8% (+27), all other client types decreased significantly: active claimants (-331; -9.1%), PPE (-17; -3.9%) and non-insured clients (-187; -11.7%). In terms of their shares relative to the total number of clients, former claimants (12.6%) increased by 1.4 percentage points while non-insured clients (24.0%) decreased by 1.0 percentage point. Other client-types shares relative to the total number of clients showed relative year-over-year stability – active claimants (56.2%; -0.7 percentage points) and PPE (7.2%; +0.3 percentage points).

The total number of interventions delivered in Prince Edward Island (10,387) remained relatively stable (+0.2%) in FY1920. With 66.1% (-0.4 percentage point) of all interventions, EAS was the most delivered intervention, whereas Employment Benefits represented 33.9% of all interventions. In total, 2,508 (+1.5%) individuals were employed after participating in an EBSM-similar intervention. Unpaid EI benefits advanced by 2.4% to $6.82 million. EBSM total expenditures reached $27.2 million (-1.8%). In addition to the Province's share of the ongoing 1.95 billion dollars in LMDA program funding ($23.9 million), expenditures included its share of the additional $250.0 million envelope announced in Budget 2017 ($2.4 million). Expenditures also included the additional targeted funding provided to support workers in seasonal industries ($525,000), as well as those affected by the trade dispute with the US in the steel and aluminum industries ($500,000).

In FY1920, Prince Edward Island increased its funding to support group-based training initiatives, to support key sectors in the Province requiring more workers. The Province has placed an increased emphasis on providing sector specific short-term training, to transition unemployed individuals back to work. Short-term training was provided to job seekers, and included a classroom component, as well as the short duration training certificates/courses (for example, first aid certifications, food safety) needed to meet specific job or industry requirements. In addition, group-based training initiatives provided job seekers with essential skills training, which included a classroom component that focused on upskilling of essential skills (literacy, numeracy, document use, writing, oral communications, thinking, digital technology, working with others or continuous learning).

Investments in targeted funding supported workers directly and indirectly affected by the lumber and steel-aluminum trade disputes, in order to support their transition to sustainable employment, through wage subsidies and training.

Text description of Chart 7

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active clients | 2,740 | 2,882 | 2,921 | 3,032 | 2,963 | 2,709 | 2,876 | 2,798 | 3,487 | 3,624 | 3,293 |

| Former clients | 487 | 572 | 574 | 708 | 703 | 621 | 657 | 709 | 784 | 712 | 739 |

| PPE | 438 | 421 | |||||||||

| Non-insured clients | 885 | 1,071 | 1,340 | 1,316 | 1,285 | 1,470 | 1,681 | 1,893 | 1,852 | 1,595 | 1,408 |

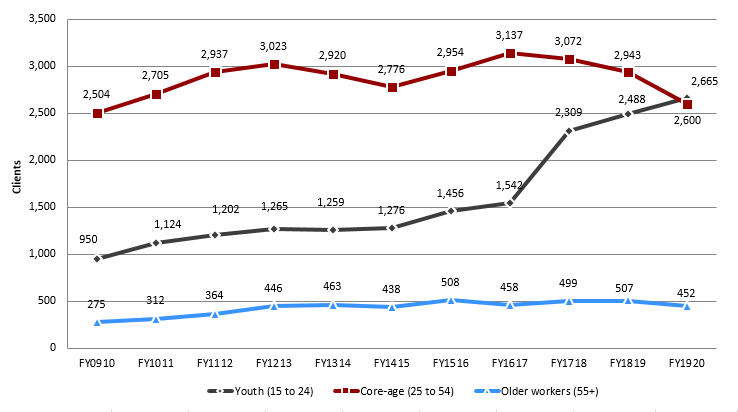

Text description of Chart 8

| Category | FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24) | 950 | 1,124 | 1,202 | 1,265 | 1,259 | 1,276 | 1,456 | 1,542 | 2,309 | 2,488 | 2,665 |

| Core-age (25 to 54) | 2,504 | 2,705 | 2,937 | 3,023 | 2,920 | 2,776 | 2,954 | 3,137 | 3,072 | 2,943 | 2,600 |

| Older workers (55+) | 275 | 312 | 364 | 446 | 463 | 438 | 508 | 458 | 499 | 507 | 452 |

Text description of Chart 9

| FY0910 | FY1011 | FY1112 | FY1213 | FY1314 | FY1415 | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | FY1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

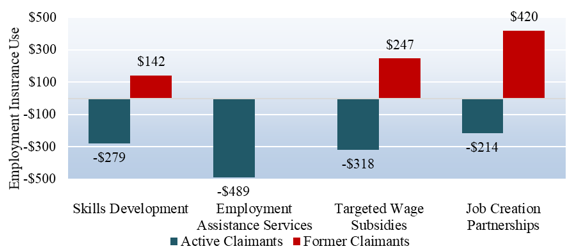

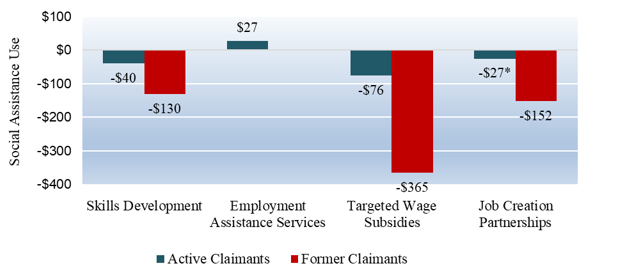

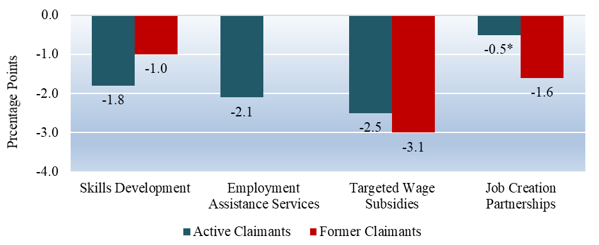

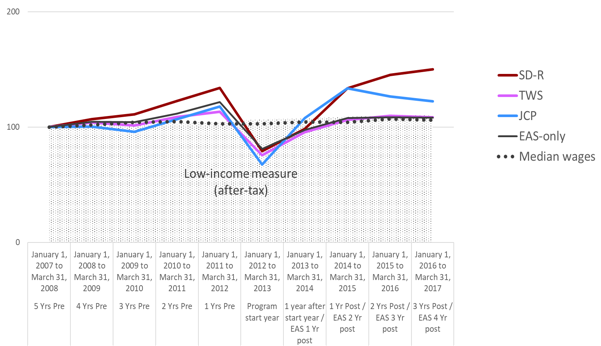

| Returns to employment | 1,839 | 2,159 | 2,034 | 1,939 | 2,194 | 1,934 | 1,997 | 2,081 | 2,202 | 2,470 | 2,508 |