Transforming our Systems: the 2022 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

From: National Advisory Council on Poverty

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of tables

- 5.2 Table: Poverty rate reduction by jurisdiction, 2019 and 2020

- 5.3 Table: Number of people in poverty and corresponding poverty rate by demographic group, 2019 and 2020

- 5.6 Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020

- 5.6.a. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Sex

- 5.6.b. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Age

- 5.6.c. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Economic family type

- 5.6.d. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Disability type (aged 16 to 65)

- 5.6.e. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Immigrants – years since landed (aged 25 to 64)

- 5.6.f. Table: Poverty rate reduction by demographic group, 2015, 2019 and 2020 – Dimension: Indigenous identity (aged 16+) (off-reserve and outside the territories)

- 5.7 Table: Poverty rates among racialized people by sex, 2020

- 5.8 Table: Poverty rates among racialized people by age, 2020

- 5.9 Table: Number and percentage in poverty by race, 2020

- 5.10 Table: Poverty rates among recent immigrants (aged 25 to 64), 2020

- 5.11 Table: Deep poverty among people with disabilities (aged 16+), 2020

- 5.12 Table: Highest and lowest annual welfare income among provinces and gaps with respect to Market Basket Measure thresholds and Deep Income Poverty Thresholds, 2020

- 5.13 Table: Poverty rates by economic family type and sex, 2020

- 5.14 Table: Poverty rates by economic family type and sex for racialized individuals, 2020

- 5.15 Table: Child poverty rates by age for all children, 2020

- 5.16 Table: Child poverty rates by age for racialized children, 2020

- D.1 Table: Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Dignity

- D.2 Table: Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Opportunity and inclusion

- D.3 Table: Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Resilience and security

- D.4 Table: Labour market indicators by immigration status and sex (aged 25 to 54), 2021

- D.5 Table: Labour market indicators for landed immigrants by educational attainment (aged 25 to 54), 2021

- D.6 Table: Labour market indicators for those born in Canada by educational attainment (aged 25 to 54), 2021

- D.7 Table: Labour market indicators by Indigenous status and educational attainment (aged 25 to 54), 2021

- D.8 Table: Labour force characteristics by visible minority group, three-month moving averages, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality (aged 25 to 54), 2021

Message from the Chair

It is once again my honour and pleasure to present the National Advisory Council on Poverty’s 2022 report on the progress of Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy.

This year the Council sought out deep conversations on a wide range of issues. We hosted 7 conversations with more than 1,000 people across the country about the underlying and overlapping causes and impacts of poverty. We then hosted a series of 8 small group sessions where people with lived expertise of poverty could share their personal stories. We heard about the struggle, resilience, frustration, and perseverance that is poverty in Canada. Those conversations and the insights that the participants shared are the foundation of this report.

This year we collectively talked about all things poverty. This included the reality of inadequate benefits that are hard to access; our shredded social safety net; troubling transitions through systems; underpaid employment and challenges with system navigation.

These conversations stressed the need for affordable and accessible child care, housing and food; secure work, a living wage, adequate benefits, and access to mental health services.

We talked about structural challenges, including deep discrimination within systems and beneath broader society, structural violence, gender discrimination and health inequity.

This included conversations about the need to ensure that community emergency planning for things like pandemics, climate change and conflict is centred on those made most marginal.

We discussed exclusion, missed or stolen opportunities and the loss of hope that living in poverty can lead to.

We heard about the constant search for stability, safety and security; the slippery slope that injury, illness, or addiction can have; the frustration of not being able to access supports early when things are clearly not working. We heard about the importance of prevention to support people before they are in crisis.

There was a sense that people are constantly being blamed or punished for being poor. Then they feel ashamed for trying to change their circumstances—whether asking for help, receiving help or leaving help.

Overall we spoke about the systems underpinning our social safety net. We heard that they are antiquated, challenging to navigate, racist and in many cases ineffective. They are also complex, interconnected and woven deeply into our culture. This means that changing one system will require re-examining them all, including our own perceptions and values. This feels big and overwhelming but can and must be done.

To start making these necessary changes, we must ask ourselves as a society why we accept that some of our fellow Canadians must live in poverty. Shouldn’t we instead strive for the best version of Canada, where not one of us lives in poverty, where we all live with dignity, equity, and opportunity?

Sincerely,

Scott MacAfee

Executive summary

In our first 2 annual reports, we have sought to better understand the systems that make up Canada’s social safety net and the role they play in creating, sustaining and perpetuating poverty. This year, we are taking that understanding to look for concrete ways to transform the social safety net and build a more equitable, just and poverty-free country.

This is an extraordinary year. For the first time, we have low-income statistics from year one of the pandemic. This data allows us to better understand the impact of the pandemic on incomes and other indicators of poverty. It provides us with an opportunity to understand the impact and outcome of the significant investments made to mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

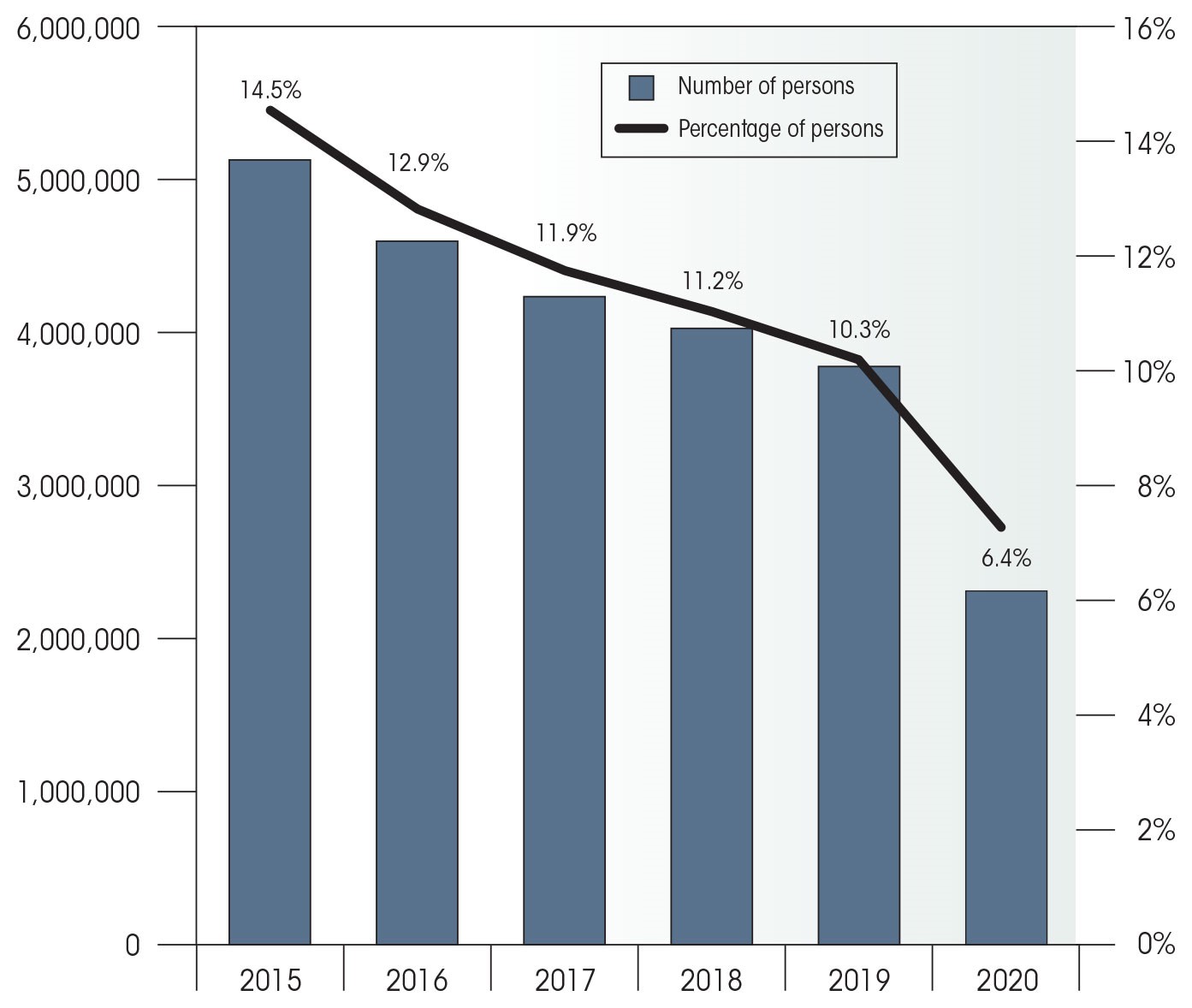

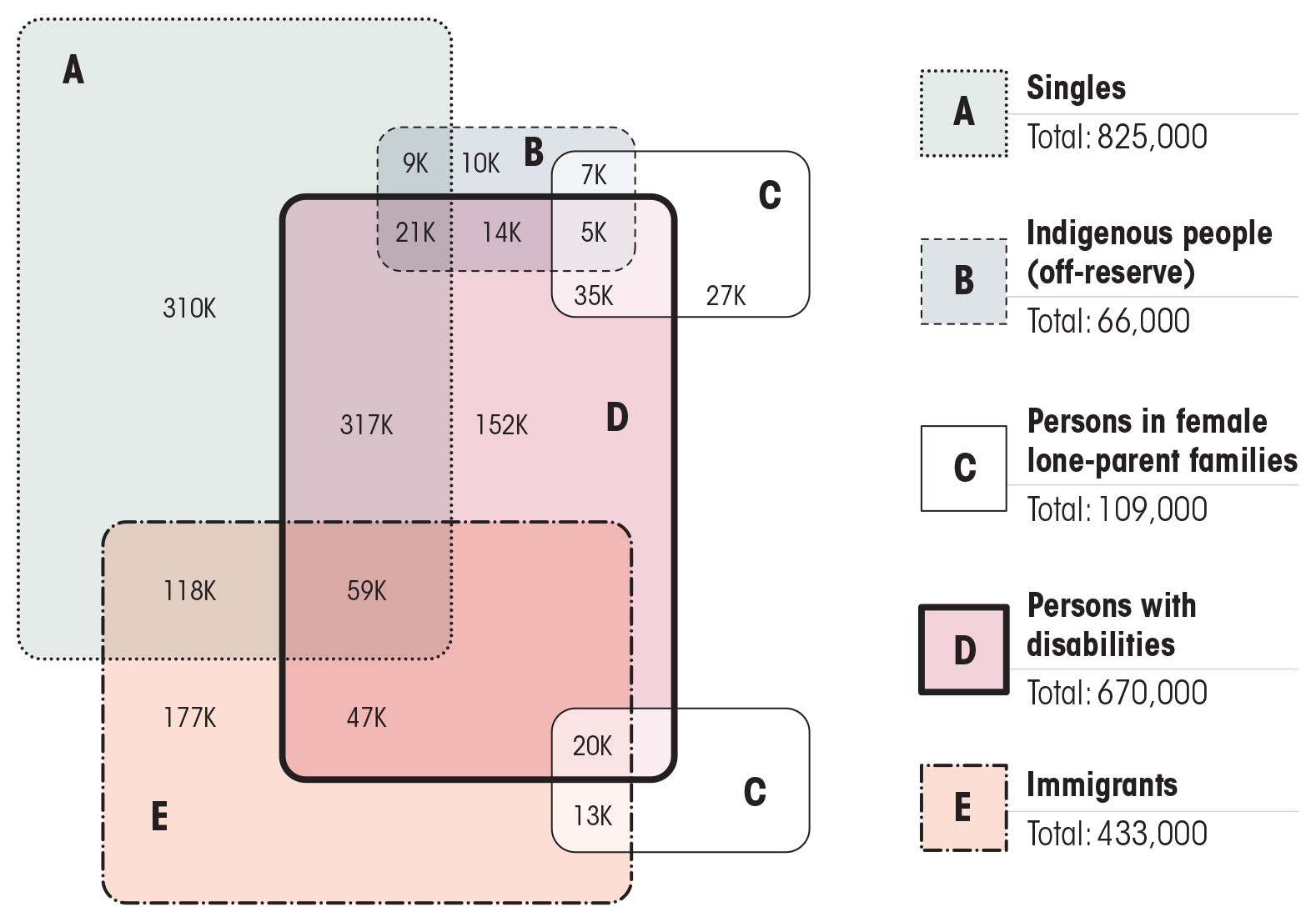

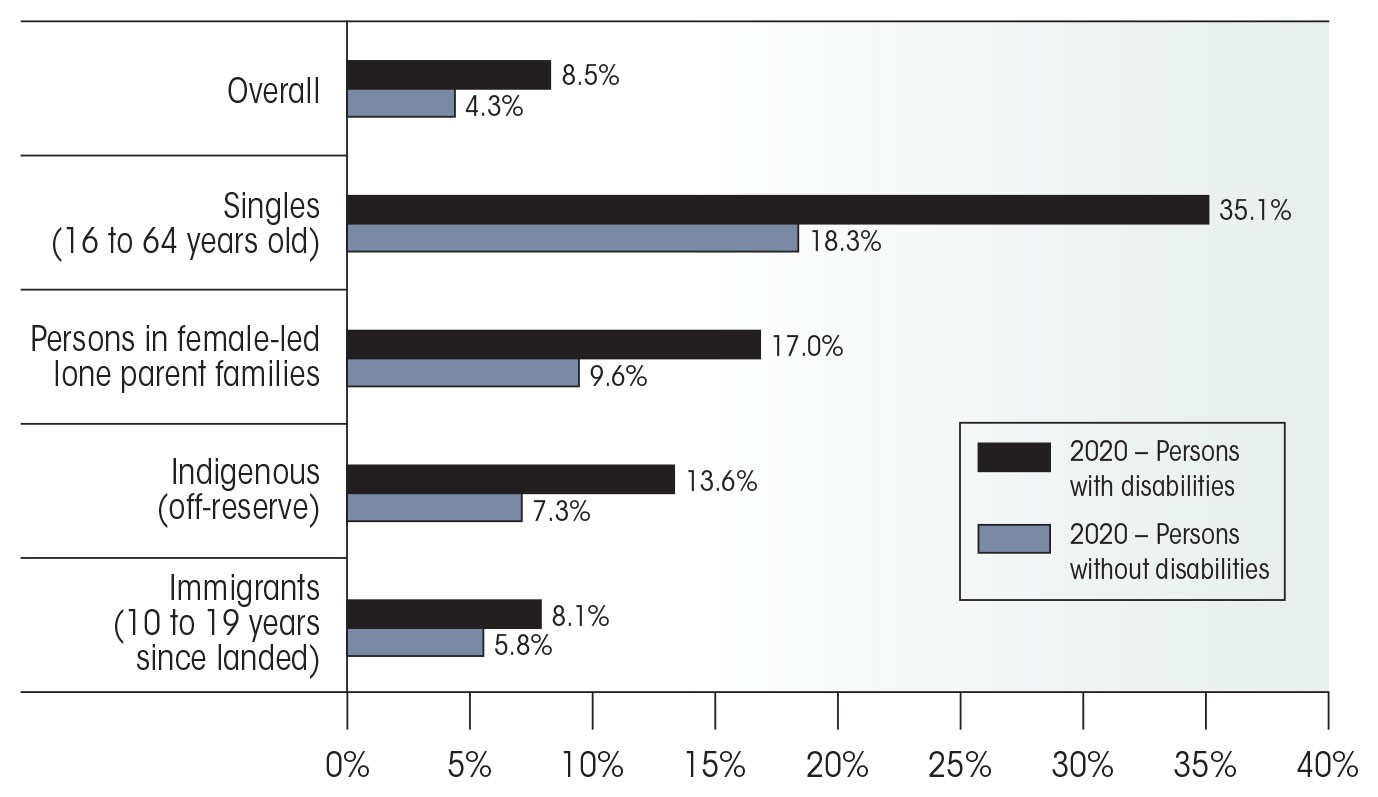

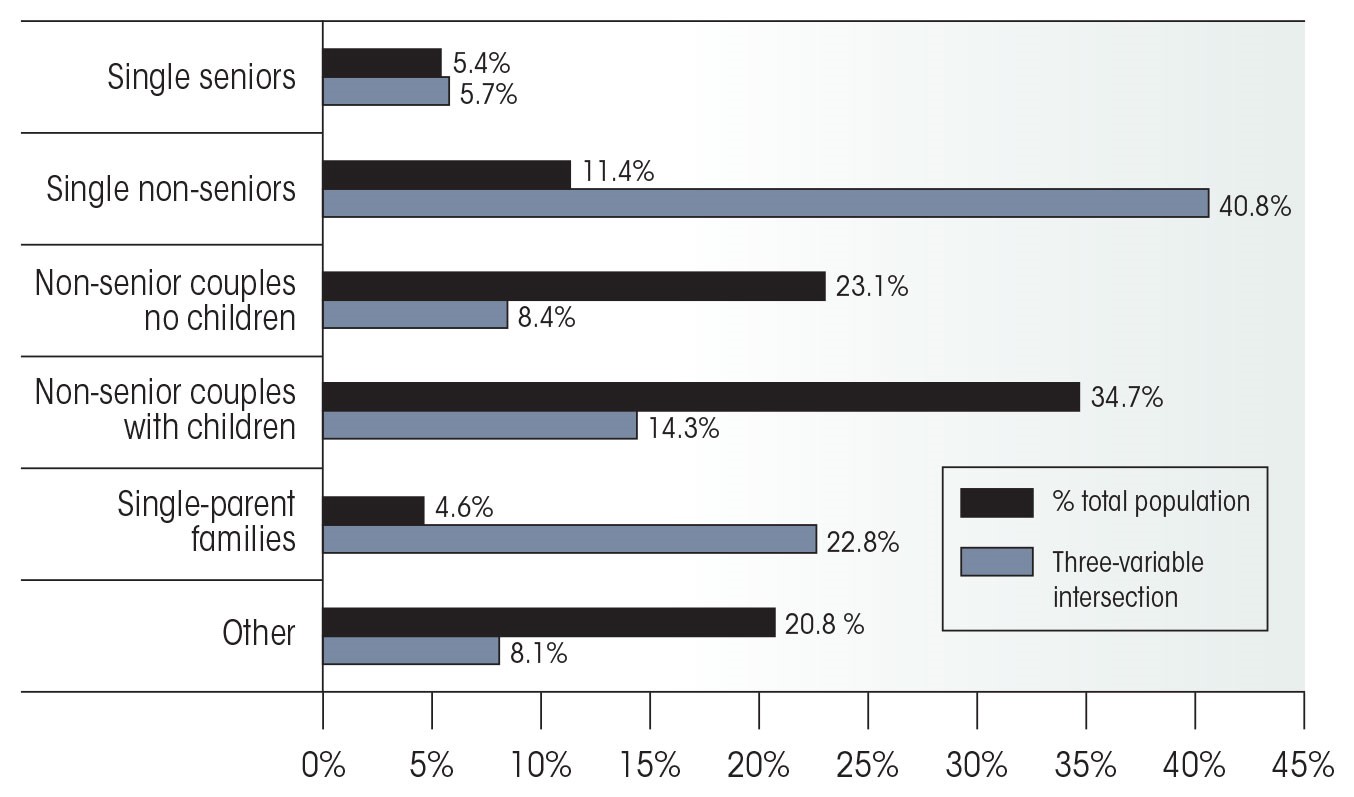

According to data from the Canadian Income Survey (CIS), the overall poverty rate, as measured by Canada’s Official Poverty Line (the Market Basket Measure or MBM), fell from 14.5% in 2015 to 10.3% in 2019 and 6.4% in 2020. This means that Canada has met both its interim target of reducing poverty by 20% by 2020, relative to 2015 levels, and of reducing poverty by 50% by 2030, 10 years ahead of time. However, as the report shows, the full story of poverty in Canada is more nuanced.

In 2020 and 2021, the Government of Canada spent billions of dollars on new and existing programs to support Canadians affected by the pandemic. Many of these measures were temporary and focussed on income replacement for individuals who were not able to work because of individual COVID-19 health impacts or the related public health measures.

We know that the pandemic did not impact everyone equally. Groups made most marginal were more likely to face adverse health and economic impacts. The pandemic is not over and we still have yet to see its long-term affects. As the Government of Canada continues to phase out emergency supports, populations made most marginal will face renewed precarity amid rising inflation, the high cost of living and long-term impacts of the pandemic—such as long COVID and increased rates of disability, mental health problems, and delays in the education and development of children and youth.

Throughout our engagement sessions we heard again about the challenges facing many people and families, including inadequate income (benefits/supports and employment income); difficulty accessing benefits and supports; and racism and discrimination that permeate our systems and broader society.

We have decided that in this report it is important to reiterate some of our previous recommendations. We feel strongly that the recommendations we have made in our first 2 reports will not only help the Government of Canada reach its overall poverty reduction goals, but that they will also help to build a more equitable and just society. Our recommendations seek to not just move people above Canada’s Official Poverty Line, but to create a society where all people are supported before they are in crisis, and to build an environment where people can thrive, not merely survive. We also did not shy away from recommendations that require bold, systemic change. Some of our recommendations will require creative solutions or new ways of doing things. We recognize that, but believe they are too important to ignore.

1. Poverty reduction with First Nations, Inuit and Métis people

We recommend that:

- the Government of Canada take urgent action to implement the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the calls for justice from Reclaiming Power: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- the Government of Canada re-commit to co-development of any new and existing poverty reduction measures

- the Government of Canada continue to work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis people to improve data collection to allow for the evaluation of poverty reduction investments and supports for Indigenous people. In particular, this can help to provide a baseline to evaluate new measures, including Bill C-92, An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families

2. Establish an income floor above the Official Poverty Line

- The Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to establish, by 2030, an income floor above Canada’s Official Poverty Line, whether it be through employment income, income supports including social assistance, new or existing targeted supports, or a combination of the 3

We also recommend that:

- the Government of Canada lead by example by working to establish a living wage in all federally regulated work places by 2030

- the Government of Canada introduce worker protections through the Canada Labour Code to address precarious work

- the Government of Canada accelerate and expand existing work on targeted benefits and supports for populations with disproportionately high rates of poverty. For example, the Government of Canada should accelerate work on the Canada Disability Benefit and ensure it provides income and employment supports that prevent persons with disabilities from falling below Canada’s Official Poverty Line. The Government of Canada should also consider targeted supports for other high-risk and underserved populations, for example, youth from care

- the Government of Canada strengthen existing and new benefits and supports that provide assistance with and improve housing, food security, health and mental health, employment and skills training, and other indicators of poverty beyond income. Both income and non-income supports have an essential role to play in sustainable poverty reduction and improved quality of life

3. Reduce poverty by at least 50% by 2030 for populations made most marginal

- The Government of Canada commit to reducing poverty by at least 50% by 2030 for all populations made most marginal

To this end, we recommend:

- the Government of Canada commit to developing and resourcing a plan to reduce current inequalities in poverty

- the Government of Canada accelerate the collection, analysis, application of and access to disaggregated data for all populations made most marginal to support evidence-based decision making and reporting of disparities. For example, Statistics Canada should accelerate work to introduce inclusive gender and sex questions and response options to key data sources on socioeconomic conditions, such as the Labour Force Survey and Canadian Income Survey

4. Early intervention and prevention of child and youth poverty

- The Government of Canada identify children and youth most at risk of the intergenerational impacts of poverty and address these impacts through benefits and programs focused on early intervention and prevention

Drawing on the recommendations for Canada of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Council endorses that:

- the Government of Canada establish an independent National Commissioner for Children and Youth. The role of the Commissioner would be to focus on children and youth who are made most marginal. Their role could include:

- identifying which children and youth are most at risk of poverty and why they are at risk

- bringing the voice of those with lived expertise in poverty to the design and development of supports and services for children and youth

- ensuring that the rights of children and youth are considered and protected in all federal policies, services, laws and practices

- examining some of the structures that are placing children and youth at high risk

5. Increase awareness of, access to and availability of government benefits and supports

- The Government of Canada increase awareness of, access to and availability of government benefits and supports as an essential tool in poverty reduction. The Government of Canada should also increase investments in sustained core funding for non-profit and community-based organizations that support Canadians living with low incomes, including those that (could) serve as systems navigators for individuals and families trying to access government benefits and supports

We also recommend that:

- the Government of Canada increase the incidence of tax filing through automatic tax filing for Canadians with low incomes, followed by implementation of automatic enrolment in other benefits and programs, particularly those that are income-tested

- the Government of Canada put people with lived expertise of poverty at the centre of design, implementation and evaluation of its policies, programs and services. Populations made most marginal should be included in the development, design and review of supports that meet their specific challenges and needs

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Transforming our Systems: The 2022 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty meets our mandate commitments by providing:

- an update on Canada’s progress toward meeting its poverty reduction targets

- recommendations that could help the Government of Canada continue its progress toward reaching its poverty reduction targets

Transforming our Systems builds on our previous reports, Building Understanding: The First Report of the National Advisory Councilon Poverty and Understanding Systems: The 2021 Report of the National Advisory Council . In Building Understanding, we examined the complex nature of poverty in Canada. Understanding Systems looked at the factors and structures that keep people in poverty. To provide recommendations for an inclusive, resilient and sustainable path forward, this third report examines:

- progress towards implementing the recommendations from our first 2 reports

- what has helped us reach our poverty reduction targets

- what it will take to maintain this progress

- who has been left behind in this process

A note on poverty rate estimates

As is customary with the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) and other household surveys, when revised population estimates become available following post-census coverage studies, survey weights are updated retroactively to better reflect overall population counts. This was the case with the 2020 CIS release, which also published revised poverty estimates for years prior to 2020. As a result, the CIS poverty estimates for years 2015 to 2019 referenced in this report will be slightly different from those referenced in previous reports.

Progress on poverty reduction

Meeting the 2030 poverty reduction targets

The first 2 annual reports of the National Advisory Council on Poverty noted that by 2019 Canada had met and passed its interim aim of a 20% reduction in poverty by 2020 but that progress in poverty reduction had not been equitable. The release of the 2020 Canadian Income Survey (CIS) data shows that there was a further drop in poverty rates during the first year of the pandemic. According to the data, the overall poverty rate, as measured by Canada’s Official Poverty Line, fell from 10.3% in 2019 to 6.4% in 2020. This means that by 2020 Canada met its target of reducing poverty by 50% by 2030, 10 years ahead of time. However, the full story of poverty in Canada is more nuanced. Inequities in poverty reduction continue and meeting poverty reduction targets does not mean that poverty reduction will be maintained.

In 2020, the Government of Canada spent billions of dollars on new and existing programs to support Canadians affected by the pandemic. Many of these measures, such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), were temporary. As governments move to phase out emergency supports, some groups will face renewed precarity. New pressures such as the longer-term impacts of the pandemic, growing income and social inequality and issues of affordability may also impact poverty rates in the years to come.

Groups made most marginal

Throughout this report, we refer to a number of populations that are underserved, overlooked and that face high levels of discrimination, racism and stigma. When we refer to groups made most marginal, these are the people to whom we are referring, including:

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis people

- immigrants

- refugees

- women

- children and youth in care

- people with disabilities

- 2SLGTBQ people

- people who:

- are experiencing homelessness

- are living in institutions

- are involved in the criminal justice system

- are living in remote areas

- identify as members of ethno-cultural groups, Black and other racialized communities

While the numbers are important, they do not tell the whole story. We must also understand poverty through the narratives and testimonies of those experiencing it. Our previous reports stressed the importance of targeting poverty reduction efforts to those “furthest behind first.” This is in line with Canada’s commitment to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. We must continue to listen to the voices of those living in poverty. Our efforts should address those most impacted, including those who have multiple marginalized identities and children and youth suffering from intergenerational poverty and trauma. We must also address the legacy of colonialism, racism, ableism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and all other forms of discrimination and stigma.

Reaching Canada’s poverty targets means reaching them for everyone, but especially those made most marginal by our society. Finally, it is crucial that Canada’s poverty reduction efforts are sustainable.

Discrimination

Throughout the report, when we reference discrimination, we are talking about the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people. We are referring to all forms of discrimination: sex, age, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, immigration status or place of origin, family status or composition, disability, institutionalization, and exposure to violence.

Progress on recommendations

Summary of past recommendations

Recommendations from Building Understanding: The First Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

- Continued poverty reduction efforts and investments, as well as increased funding in 4 key areas: food insecurity, housing and homelessness, literacy and numeracy, and the poverty gap

- Urgent action to tackle Indigenous poverty with more specific measures

- Increased data disaggregation to better account for and give a voice to marginalized populations

- Applying an equity lens in policy-making

- Streamlining and coordination of benefits and bringing a level of support that is at least at Canada’s Official Poverty Line

Recommendations from Understanding Systems: The 2021 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

- Indigenous prosperity through truth, reconciliation and renewed relationships. (Implementing the calls to action from both the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls)

- Building equity through programs, supports and benefits. (Inclusive data collection and commit to reducing poverty by 50% by 2030 for marginalized populations)

- Dignity through enhanced access and improved service design and provision. (Simplify the delivery of programs and supports for all people)

- Develop robust systems and structures focused on early intervention and poverty prevention

- Employment income and income support. (Ensure a coordinated and robust social safety net in Canada by collectively providing income support that is at least at the level of Canada's Official Poverty Line)

The full recommendations from Building Understanding and Understanding Systems can be found in Appendix A.

Progress on Government of Canada’s commitments and investments

Since Understanding Systems was released, the Government of Canada has made a number of investments that we expect will have an impact on poverty reduction, including:

- reaching agreements with all 13 provinces and territories and with First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities to build an affordable Canada-wide early learning and child care system

- increasing the length of Employment Insurance (EI) sickness benefits from 15 to 26 weeks, as of summer 2022, to better support those with longer-term illness (Department of Finance Canada, 2022)

- expanding the Canada Workers Benefit to support one million more low-income workers (Department of Finance Canada, 2021)

- increasing regular Old Age Security (OAS) payments for pensioners aged 75 and older by 10% as of July 2022 (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2021)

In addition, the Government of Canada has announced a number of commitments in Budget 2022 that will help address poverty. We encourage the Government of Canada to implement the following measures as quickly as possible:

- increase funding for affordable housing through Reaching Home, the Rapid Housing Initiative, the National Housing Co-Investment Fund, and other initiatives to help address housing and homelessness issues

- increase funding to support the implementation of An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families to address disparities in the child and family services system

- create a national dental care program for low-income Canadians, with coverage for children under 12 years of age starting in late 2022, to address a gap in services for low-income Canadians

- create a new anti-racism strategy and national action plan on combatting hate to ensure Black and racialized Canadians and religious minorities can fully participate in the Canadian economy

- develop a national school food policy to address food insecurity among children (Department of Finance Canada, 2022)

A more complete list of Government of Canada commitments and investments can be found in Appendix B.

Progress made on data collection and surveys

Since Understanding Systems was released, the Government of Canada has made progress on the collection of disaggregated data to support better decision-making and reporting on poverty. Disaggregated data includes collecting data and creating categories that account for the individual experiences of specific groups.

Last year, Canada became the first country in the world to collect and publish data on gender diversity in its national census. The 2021 Census included a question on gender and added precision to the sex question to allow individuals to indicate their sex “at birth.” These changes follow the introduction of inclusive gender and sex questions on most Statistics Canada health and social surveys in previous years.

As of July 2020, the Labour Force Survey includes a question on racialized status. The 2020 CIS collected and published poverty data for racialized communities for the first time. Taken together, these updates could contribute to better understanding the poverty rates of racialized people in Canada. Collecting data is a good first step. Now the Government of Canada needs to use it to ensure that its poverty reduction efforts promote equity by reaching populations made most marginal.

Statistics Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada continue to collaborate to develop a Northern Market Basket Measure (MBM-N) that will allow official poverty rates to be calculated for Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Work to develop an MBM for Nunavut is also ongoing.

Where progress is still needed

Despite progress in a number of areas where the Council has made recommendations, areas remain where we recommend the Government of Canada act to meet poverty reduction targets more broadly, but also to create a more equitable society. Many people do not have access to secure work with a living wage and portable benefits. The Government of Canada needs to look for ways to prevent precarious work, ensure protections, and help people access benefits without gaps when they need it most—for example, when they lose their job or their benefits, or are suffering from poor mental or physical health. In many cases, benefits remain below Canada’s Official Poverty Line, trapping people in poverty. Additionally, benefits remain difficult to access for many people. We will speak to this further in our recommendations.

Transforming systems

Forging an inclusive and resilient path forward

The benefits of a strong social safety net permeate outwards and ripple through families and communities.

Throughout our engagement sessions for this report, we heard that we must transform our systems, and our society as a whole, if we want to meet our poverty reduction targets and eliminate poverty. The reasons people fall into and remain in poverty are complex and systemic. At the same time, we know what the chronic problems are. Over and over, we heard about drivers of poverty, such as:

- inadequate employment income and income supports

- the growth of precarious work

- rising unaffordability due to inflation

- the ongoing marginalization and vulnerability of groups through discrimination and exclusion

We also heard repeatedly about the lack of effective strategies to prevent poverty:

- a broken social safety net

- inaccessible benefits and supports

- governments and other organizations that do not work together

We heard of differential treatment because of systemic racism, and that some within our systems and the wider public hold prejudiced views about those living in poverty. These beliefs and assumptions strip people of dignity and agency over their lives. They perpetuate the myth that some people are unworthy or undeserving and undermine anti-poverty strategies.

We know that the pandemic has been eye-opening. We learned that no matter who you are or how “safe” you are, poverty is not too far away. Many people who considered themselves fully independent would not have endured without government support. We also quickly saw that the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequities, with populations made most marginal more likely to face lost income, risk of serious illness or death, and challenges accessing affordable housing, food and other essential services.

The pandemic responses also showed us that as a country we could do things differently and better. Data shows that increasing eligibility for benefits, providing greater income support and targeting populations made most marginal had a real and positive impact on poverty rates.

The pandemic provided us with a real world, large-scale pilot project of what a more substantial and inclusive social safety net could look like. Of course, this does not mean that no one was left behind. Some of the populations made most marginal could not access adequate supports and fell further behind, as the bulk of supports were available only to those in the labour market. Also, while many people’s incomes went up, other indicators of poverty worsened, such as food and housing insecurity. We must learn from the successes and failures of the last 2 years to rebuild a social safety net that works for everyone.

The true safety net is the communities we build and bring together.

Effective and equitable poverty reduction will require a whole-of-society commitment to rebuild and maintain systems that leave no one behind. People who rely on our existing systems—which were specifically designed to help them—have told us that those systems often hurt them instead. We need to prioritize effective poverty reduction. We need to ensure that we reduce disparities by focusing on those furthest behind. At the same time, poverty does not begin and end with government income benefits. There needs to be cooperation and coordination between all orders of government to ensure that:

- people who are in full-time work are not left in poverty

- people who are receiving benefits are not in poverty

- programs which are set up to prevent people falling into poverty or to help pull people out of poverty work equitably and reach those furthest behind

This requires the active engagement of many groups in Canada, including employers, civil society, community and government.

Chapter 2 – What we heard: Challenges

Background

Engagement to inform the development of this report took part in 2 stages. Between February and April 2022, the National Advisory Council on Poverty held 7 virtual engagement sessions with over 1000 stakeholders, including people with lived expertise in poverty (a full list of Stakeholder groups that participated can be found in Appendix C). These sessions encouraged cross-sectoral conversations on the following topics:

- The future of work: From precarity to security

- From communities, by communities: Grassroots responses to poverty

- The poverty trap, chronic and transient poverty

- Transitions in and out of support systems: poverty prevention, early interventions, and targeted supports

- The future of health and poverty: Building resiliency, equity and justice

- Future-proofing the social safety net

- Climate change and poverty: Addressing vulnerabilities, creating resiliency

Phase 2 was a series of small group conversations with people with lived expertise in poverty. While poverty can affect anyone, we know that certain populations are far more likely to experience vulnerability to poverty, discrimination and exclusion. Often these same voices are missing from official narratives and data. The goal of this year’s engagement sessions was to foster an environment where individuals from diverse backgrounds and communities could share their ideas and experiences while connecting and breaking siloes in poverty reduction. We also made a concerted effort to reach new populations. For the first time, we heard from children and youth about their thoughts on poverty.

These sessions allowed us to speak directly to people with lived expertise in poverty so they could share with us their experiences, challenges and what has worked and not worked for them. These sessions were a key piece of our engagement. Over the last 3 years, we have tried to share the voices, expertise and experiences of some of the individuals made most marginal in our society. We are grateful to them. Their knowledge, expertise and personal circumstances are the backbone of this chapter and are woven throughout the entire report.

When voices are amplified and stories are heard it normalizes the story without desensitizing us […] when people are given their voice and own their story, the community comes around them.

However, we were not able to reach everyone. There are many layers of vulnerability, and we understand that some people are fearful of sharing their story or are unable to do so. We will continue to find ways to include the voices of those made most marginal by our society at the centre of our work. The remainder of the chapter provides a summary of some of the key themes and highlights that emerged from the discussions. The richness and diversity of what we heard is difficult to capture in a concise manner, but we feel it is important to share the stories, experiences and voices of the people with whom we engaged, in their own words. These expressions do not necessarily reflect our own thoughts, feelings or beliefs. In some cases, data backs the opinions we heard. In other cases, there may not be adequate data to support them. Either way, this summary aims to present what we heard in an authentic and honest way.

Complexity and intersectionality

We have tried to capture a vast amount of information and organize it in a meaningful way. However, we believe that it is essential to reflect fully the needs of those in deepest poverty. People with multiple, intersecting vulnerabilities are significantly more likely to be living in poverty with complex needs. Addressing one issue, or parts of an issue, will not be enough. Therefore, while many solutions are offered below, nothing can replace a comprehensive approach that puts people at the centre and addresses their interwoven and complex needs as a whole.

Systemic challenges

There were many significant and specific challenges raised throughout the engagement sessions. Overall, the systemic challenges we heard about fall into 3 main themes:

- inadequate income (benefits/supports and employment income)

- access challenges and barriers to take-up of benefits/supports

- racism and discrimination

We continued to hear that income benefits and employment income fall short of people’s needs. People who rely on government supports are made marginal and left in precarious situations. This is either by design or due to the unintended consequences of their implementation. Vulnerability is built into the system.

People with lived expertise in poverty described their experiences trying to access supports within a tangle of different systems. They described the systems as fragmented, cumbersome and operating in silos. Trying to navigate the systems left them feeling overwhelmed, stripped of their dignity, and dehumanized.

Participants spoke about systems that are built for particular groups and a particular type of person. That person tends to be white, male, heterosexual, cisgender and born in Canada. This means that many people are left to navigate systems that were not built for them. These systems perpetuate discrimination and create challenges for many groups.

We heard clearly that the poverty reduction is a government responsibility first, but not exclusively. Employers, non-profit organizations and people in general all have a role to play, with the government’s leadership.

Income from minimum wage employment and government benefits is not sufficient to lift people out of poverty

Poverty isn’t only about income, but it is always about income.

Income adequacy is the primary issue

The social safety net begins with income stability.

The overarching theme throughout the sessions was income adequacy. Whether it is minimum wage, gig or precarious employment, or government benefits, those who are living in poverty do not have sufficient income. People spoke passionately about the mental weight of not being able to meet their basic needs. Rising prices due to record inflation and housing costs are further straining many individuals and families. This is especially true for those living in poverty or close to it. There is a sense that prices keep going up but wages and social assistance rates do not. People spoke about the stress that this causes and described the situation as “scary.”

Poverty is not a choice. Nobody chooses this. We all want better things for ourselves and for our children.

Income support is a fundamental part of our social safety net in Canada. However, we heard that the support, particularly social assistance, is woefully inadequate. Benefits are not lifting people above poverty, but rather are keeping them there. There was a strong consensus that government benefits should be at or above the poverty line, not below it.

The MBM is not designed for people to thrive.

There is also a sense that the Government of Canada has enough money to solve these problems, but not the will to do it. Many of the necessary support systems exist, but the amount of supports needs to be increased and the systems improved. Participants acknowledged the significant impact of the Canada Child Benefit, but mentioned that they wanted to see programs like it and Employment Insurance (EI) expanded. EI can be difficult to access, as many people do not work a sufficient number of hours to qualify. Many families are forced into poverty while on parental leave, even when receiving EI. We heard the view that supports are inadequate on purpose, to drive people to enter the labour market. However, low-paid work is precarious and does not provide sufficient compensation for meeting basic needs. This type of work also rarely provides benefits, like sick leave, dental and extended health benefits.

The consistent missing link is political will.

First-person experience – Maternity and parental benefits: Starting life in poverty

Many of the participants shared their experiences of accessing maternity and parental benefits. While employees are able to access up to 18 months of parental leave to care for their babies, the reality is that many families living with low incomes are not able to make ends meet on their EI benefits. EI provides a maximum amount of $638 per week (2022). However, only people that have $60,300 of insurable earnings receive this. Someone with $30,000 of insurable earnings would get a maximum of $317 a week (55% of $30,000, on a weekly basis). This is below current poverty thresholds and insufficient to meet a family’s needs. Parents are often forced to choose between continuing to work rather than taking parental leave, and living in poverty. For many families, the first year of a child’s life is therefore a life in poverty.

The social safety net is broken

I now envision the social safety ‘net’ as shredded fishnet stockings.

We heard from participants that the social safety system has not kept up with social, economic and labour market changes. It also intervenes with too little, too late. Instead, the social safety net should empower and support people before they are in crisis. As we have learned from the pandemic, systems also need to be nimble and inclusive to respond to shocks. To do this, however, they also need proper investments. We need to break down siloes to make systems more accessible, seamless and responsive to the complex needs of individuals and families. The social safety net should include every government department and it should allow everyone in society to feel safe.

Work is not always enough to reduce poverty

We can put anyone into a minimum wage job, but it doesn’t get you out of poverty.

Many people work but that doesn’t always provide them the means to survive.

Another consistent theme to emerge from the conversations is that work is no longer a guaranteed pathway out of poverty. Too many people are working in minimum wage jobs, precarious jobs and/or the gig economy. The pandemic exacerbated this situation. Minimum wage is insufficient for people to escape from poverty. Furthermore, low-wage employment— which people living in poverty are likely to get—often does not provide extended benefits, sick days or protections.

When can I afford to be ill or when can I afford to take care of my children?

Without extended benefits, it is hard to be healthy. Also, not having benefits limits the options of parents living in poverty. People reported feeling constantly anxious that they or their children would get sick and they would have to miss work.

Child care and caring for ill or elderly family members, and those with disabilities, can make work out of reach as well. People, particularly women, who are responsible for unpaid care work, often face challenges balancing their care responsibilities with paid employment. Women are often forced out of the labour market for care work. This results in a loss of benefits, loss of income, and can impact EI contributions (affecting insurable earnings). The high cost of care relative to low wages makes staying home more cost effective in many cases. The signing of early learning and child care agreements in all 13 provinces and territories is a promising development on this front.

We need better labour market systems and structures to again make employment a pathway out of poverty.

Clawbacks discourage transitioning to paid work

Clawbacks for people with disabilities can really end up destabilizing someone’s life.

Benefit clawbacks (deductions from or loss of eligibility for one support when receiving another) are a significant concern for many people living on a low income. Clawbacks (real or perceived) of wrap-around and income supports often have the unintended consequence of creating disincentives to work. People often fear the prospect of losing benefits such as social housing when they transition to work.

Stakeholders stressed the need for a social safety net that does not penalize people for working (or trying to work). Participants also noted the significant challenges for people with disabilities, particularly in jurisdictions where they face steep clawbacks of their employment income. This can destabilize their current situation and keep them in or instigate a future in poverty.

If you are getting support and make just a tiny bit of money you will lose the support.

First-person experience – Turning down a promotion: The cost of clawbacks

Clawbacks can take different forms. They can be dollar for dollar reductions of income benefits. They can also mean the loss of supports and services or of social housing.

One person shared the experience of receiving a promotion opportunity at work. The increase in pay would have resulted in earning just above the threshold for social housing. The loss of social housing far outweighed the benefits of the pay raise, so they turned down the promotion.

Unintended consequences can force people to make impossible choices

In addition to clawbacks, rules, eligibility requirements and program interactions can leave people feeling as though they have no choice. They also force people to make impossible choices. Many people shared that they felt as though the system was designed to make them fail. The rules are often complicated, counterintuitive or punitive.

For example, we heard that for certain types of addictions counselling, people are required to not be working while undergoing treatment. When someone finishes their counselling and achieves sobriety, they then face the challenge of unemployment. This can lead to homelessness.

Benefits and services are difficult to access

It’s an incredibly complex set of mismatched tools that governments have put together. It feels like you have to have a PhD to navigate it.

The social safety net is complex and inefficient

The things that are meant to be Canada’s social safety net—government income supports—they are all challenging to access and insufficient and keep people in poverty.

We heard that all of the programs and benefits that make up the social safety net are difficult to access. There are so many different support programs at the federal, provincial/territorial and municipal level, as well as services provided by the non-profit sector. Some of these overlap, but there are also gaps. This makes the system very complex and confusing. People miss out on benefits and supports, often because the system is too difficult to navigate, and they are discouraged.

One misstep and you won’t make it out.

Some of the specific access challenges that we heard include:

- the movement to online service delivery can be a barrier for those who lack computer literacy or cannot afford internet services or a computer (not all websites work with a cell phone)

- long waits for telephone help lines use up people’s limited cell phone minutes while they are waiting on hold

- difficulty finding programs that can help—there are potentially many programs, but the information is too vague or too much and overwhelming

- complicated forms take a long time to complete, and they sometimes require supporting documentation that takes additional time and money to get

- there is a long wait for a response after submitting the application

It’s just mind-blowing how many barriers there are.

In addition to being difficult to navigate, we heard that the current system wastes people’s time and energy. For example, we heard frustration about the government making people submit information that it already has, placing an unnecessary burden on individuals. We also heard that the government often seems too focused on eligibility. Too much money and time is spent making sure trivial abuses of the system do not occur. Meanwhile, people who do need support wind up falling through the cracks. All of that energy should be put into making sure that everyone who is eligible knows that they are eligible, and ensuring they access the supports to which they are entitled. A lot of money is unclaimed because people do not know how to access it. An income support system that leaves people living in poverty is inefficient and ineffective.

Nets are meant to catch or trap people. It’s a full-time job to navigate this so-called safety net. It takes up so much time and energy.

Physical and mental health and dental services are hard to access

Many participants shared their difficulties with accessing health services and described the impacts of this on their overall health and wellbeing. Some spoke about the challenges accessing a primary care provider, especially if they have multiple diagnoses, addictions issues or involvement in the criminal justice system. Others noted the challenges of accessing mental health services. Youth participants talked about the increase in mental health challenges caused by the pandemic and the associated public health measures.

My teeth are falling out of my head and there isn’t anything I can do about it.

Cost is a significant barrier to health services. Often, mental health and counselling services limit people to one free session and many are unable to pay for ongoing care. Dental care is simply unaffordable to many people. Medications are not always covered. One participant shared that they were eligible for a nebulizer for asthma, but not the medication that goes in it.

First-person experience – Failure to heal properly: The impact of an unaffordable healthcare system

While Canada is known for its free medical care, there are significant limits to the care and services that are offered at no cost.

One person with lived expertise in poverty shared the experience of an injury—a broken bone—resulting from violence. They were able to go the emergency room and receive care without any out-of-pocket expenses. However, the injury required follow-up care, including physiotherapy. The follow-up care required out-of-pocket payment and they were not able to pay for it. The injury never properly healed and resulted in chronic pain.

Racism and discrimination are pervasive and our systems replicate and perpetuate inequality

Equity is the process, equality is the outcome.

Racism and discrimination are pervasive in the social safety net

It is a tragedy that young Indigenous families have their children torn away from them not because they’re bad parents, but because they’re in poverty.

We heard that discrimination is built into our systems. Poverty rates are high for groups made most marginal. This demonstrates that the social safety net does not reflect the diversity of needs and does not work for these individuals and families. We also heard that there is a sense that First Nations communities do not have a social safety net.

Staff at many important access points and services lack the awareness and understanding required to work successfully and respectfully with individuals who are made most marginal. We heard this in particular for 2SLGBTQ youth and youth with disabilities. Infantilizing behaviour towards youth limits their input into how their lives or issues are treated. General attitudes towards people with disabilities, trans people and others are a barrier to their inclusion.

There is a lack of focus on mental health and addictions training.

Disaggregated data is essential for understanding the experience of groups made most marginal

The experience of poverty is disproportionately different across groups. Some populations face more disadvantages and challenges, and until recently, their experiences have been left to anecdotal evidence. As a result, previous change efforts did not recognize those disproportionate inequities.

Some participants suggested that poverty rates should be a measure of how municipal and provincial/territorial governments are performing. Disaggregated poverty and homelessness rates should be easily accessible to voters to better inform them and to help build political will.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people need to be involved in program and policy design

In my community there’s a death every month. A lot of people don’t realize what […] Indigenous communities face.

Access to culturally appropriate services for First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities is a key aspect to delivering support. Applying for government programs is a burden for community-based organizations—often First Nations do not have the human resources capacity to do it. Participants spoke of the need for governments to discuss with First Nations before designing and implementing programs and policies. Often the government designs programs that, despite good intentions, do not reflect realities in First Nations communities—yet communities must adopt them and adapt to them. Instead, funding should be given directly to First Nations to design their own responses. Consideration should be given to creating a specific First Nations, Inuit and Métis poverty reduction strategy.

Some participants stressed that in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, colonialism is the cause of poverty. There was no such thing as poverty before colonialism. Traditional economies have been destroyed, putting First Nations, Inuit and Métis people at risk.

I think that we always need to be centering Indigenous nations and Indigenous sovereignty in these issues.

Colonial, western health systems do not serve everyone

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people experience an incredible depth of racism within the healthcare system that strongly deters them from accessing healthcare. When they leave their communities, they fall through the cracks in the healthcare system. To address gaps, we need to look at solutions from Indigenous perspectives. Services could better encompass spiritual and social aspects, not just medical/physical aspects of care.

Healthcare professionals must work to understand cultural differences. Interpretation and translation are often not available in the healthcare system. The root causes of poor health must be examined from the perspective of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people. The impact of colonialism underpins the social and economic marginalization and health inequalities that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Continued impact of the pandemic on youth

In our engagement sessions, many youth spoke about the impact that the pandemic has had on them, including challenges with online schooling. Some youth lacked a stable connection to the internet. Others spoke about different challenges, including:

- lack of connection to peers, including congregating with peers

- inability to ask their teachers questions or to have informal discussions with them after class

- trying to study/learn in overcrowded housing

- parents who were not able to help with homework

Children and youth faced a wide range of challenges. Many children faced disruptions to their development, for example through the closure of schools, extracurricular activities, camps etc. This also means disrupted access to nutrition, child development and health screenings, and a safe adult to speak with if needed. Older youth also spoke about disrupted pathways, as they lost or could not find jobs due to the pandemic (for example, losing income they counted on for school). Others faced challenges with online schooling. They continue to experience mental health challenges, including anxiety and depression. We are into the third year of disruption of both education and of the child wellness and protection systems embedded in the school system.

Poverty can lead to criminalization

Contact with the legal system is not a rare experience. In BC, over a 3 year period, 75% of low-income individuals experienced at least one everyday legal problem (a problem arising out of the normal activities of people's daily lives that has a legal aspect and has a potential legal solution). Consumer problems accounted for 43% of these (Sentis, 2018). Nationally, nearly half of all adults encountered a family or civil justice problem over that same reference period, meaning that almost all Canadians are expected to be confronted with a legal problem during their lifetime.

Poverty affects every aspect of how one experiences being accused and possibly convicted of a criminal offence. This includes the likelihood of being considered as a suspect, interactions with police, making bail (a decision affected by whether someone has a fixed address, is properly documented, has a job, etc.), plea decisions and sentencing.

Lack of representation is a significant issue. Lawyers are expensive and out of reach for many people living in poverty. People living in poverty often plead guilty because the alternative is too difficult for them. Public defenders are paid for a set amount of time and it limits the preparation and defense time for any case. This adds structural pressures to accept plea-bargaining and plea decisions. One woman shared the challenges of accessing legal aid. She noted that if she earned over $1600 dollars a month, she would lose her legal aid and her lawyers who were trying to fight for her life. She could not afford to pay for a lawyer, so she had to be sure to earn less than $1600 to keep her legal aid. At the same time, though, she had to show the court that she was a contributing member of society. Working full-time would improve her chances of demonstrating this.

If I worked to my ability I would lose my representation.

First-person experience – A vicious cycle: Meeting the conditions of a sentence

More than one participant shared with us the realities of trying to navigate the criminal justice system as a person living in poverty. In many cases the court imposes volunteer hours and/or counselling as part of a sentence. However, there are limited volunteer opportunities for someone with a criminal record, and counselling sessions have a fee. For many people living on a low income, this can result in a failure to complete the sentencing requirement, which in turn leads to their incarceration. This is due to poverty, not an individual’s unwillingness to comply.

Intimate partner violence can leave women vulnerable to poverty

Many female victims of domestic violence experience multiple episodes of poverty. Economic abuse in the home (preventing women from having paid employment, and/or controlling the money) has 2 consequences: creating invisible functional poverty for women and preventing women from fleeing the home.

When they do escape, women often remain financially dependent on their abusers, due to their reliance on alimony and child support. Abusers often use the family court system to continue economic and psychological abuse—for example, drawing out the court proceedings and/or withholding alimony and child support. The family court system is failing women, leaving many in poverty.

We also heard about the need for more of other types of supports. For example, there is a lack of female-only shelters in some jurisdictions; many women do not feel comfortable in mixed-gender shelters.

If I am a woman fleeing domestic violence, I don’t want to go into a mixed-gender shelter.

Chapter 3 – What we heard: Possible solutions

The conversations focused on many of the challenges caused by benefits and services that are inadequate and difficult to access. However, there were also significant discussions around the systems changes needed to address poverty in a meaningful way, especially for those who have been made most marginal.

System change is required to address poverty and challenges caused by unaffordability

We can’t make progress on any of these issues without making progress on all of these issues.

Provide income above the poverty line

There were many discussions about ways to achieve an income floor above the poverty line, below which no one could fall—whether they are working, receiving benefits, or both. Some suggestions include:

- expanding existing benefits and supports (for example: Canada Child Benefit, Canada Workers Benefit, Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement)

- a universal basic income

- a negative income tax model (a system which reverses the direction in which tax is paid for incomes below a certain level)

- a combination of both a living wage (from employment) and a basic income (government-provided support)

The idea that you can buy one less coffee in a month and you will get out of poverty is f*cking bullsh*t.

Universal basic income meets basic needs and allows people to participate in the labour force to the extent that they are able

What if we made sure everyone had enough to live well?

Participants noted that a universal basic income would help alleviate many of the existing system challenges, including:

- difficulties accessing EI

- needing to take time off from paid work to upgrade skills

- loss of benefits when leaving social assistance for employment

In addition, a guaranteed basic income would allow individuals to participate in the labour force to the extent of their ability. This would in turn free up funding and resources to devote to people with more complex needs.

Everyone wants to contribute. Nobody wants to feel like a burden.

A living wage is key to enabling working without poverty

Many people work but that doesn’t always provide them the means to survive.

Many people believe that a basic income alone is not the answer, but that it must go hand in hand with a liveable wage. They see the absence of a living wage as a crucial driver of poverty. A living wage is an important part of poverty reduction efforts. While participants agreed with the need for a living wage, there was discussion around who is responsible for it—employers or government. Some suggestions included employer incentives or a federal top-up benefit (to match the regional Market Basket Measure) to reach all Canadians.

Need to leave behind the charitable model and move to a human rights model

Participants spoke about how a human rights-based model would create accountability for governments. It would also shift the focus from a charity-based lens to treating and supporting people with the dignity that they deserve. People should not have to rely on charity to meet their basic human needs.Early intervention and upstream investments have a significant impact

Everything we do is all down river and reactionary.

Many participants spoke about the need for early, focussed and cohesive interventions for families in precarious situations. The social safety net often kicks in too late, when people are already in crisis. The focus should be on prevention, not just reaction. Helping people to thrive before they are in crisis is more effective, compassionate and humane. Support should continue until people’s situations are stabilized. Cutting off support too early can leave people in poverty, without resiliency, or make their exit from poverty inhumanely temporary.

We heard that there is a need for policy change to stop the revolving door of poverty, oppression, and trauma. Governments focus on short-term solutions. Preventive measures would improve health, social and economic outcomes in the longer run, as well as reduce costs associated with reactive interventions later. Participants also noted that the roots of poverty are not being addressed—colonialism, discrimination, mistrust, etc.

The healthcare system is one area where early intervention is critical and can help to address challenges related to intergenerational poverty. Poor health outcomes perpetuate themselves from generation to generation. It is much easier and more cost-effective to provide resources to families upstream, before they are in crisis or in transition.

Attention is given to those who need it the most— it’s prioritized. You don’t receive all the care you need until you’re in critical need.

Comprehensive wrap-around services are an essential part of the social safety net and an important poverty reduction tool

Poverty is generally the result of exclusion and a lack of supports.

Wrap-around supports are essential for people who are transitioning between benefits and employment

When your basic benefits of life are tied to an employer you don’t have much freedom of mobility.

Universal, portable benefits can help to alleviate some of the challenges when people are moving from a program like social assistance to employment, or for those working in the gig economy.

People have complex needs and require comprehensive supports, but those supports are provided in silos. Many participants noted that every point of access should be a doorway to all services, regardless of who the service provider is, and of what system they are a part. For example, someone accessing employment services could at the same time find out about other services and supports that may be helpful (for example, housing, health, food). Another example is for healthcare providers to provide links to available social services and supports. A more holistic approach and crossover between systems will help to break these silos. In short, we need to start with the person—what supports do they need and how do we ensure they receive them?

Individual support is essential

Need to start from the lens of what is beneficial to the individual.

Families and individuals have unique experiences, and they do not all find themselves in poverty for the same reasons. We cannot solve complex problems with simple, one-size-fits-all solutions. Targeted services and supports are the most effective. Social services need to be appropriately staffed. Caseloads are unmanageable. There is a tendency to focus more on immediate crisis than taking the time to think through and provide supports to help people to move out of social assistance programs.

As a person who experienced poverty, it doesn’t feel like you are living. You are in a survival mode.

Emotional supports can help protect mental health and safety as people are transitioning between systems

I wish there was more intentional and respectful discharges (from prisons, hospitals, addictions treatments) ... if you don’t have meaningful discharge plans ... if you don’t have some kind of intentional, respectful plan ... they will end up back in that system because they don’t have those supports.

There is a need for a softer, smoother and more thoughtful transition between systems. Many people go abruptly from having supports to receiving none. One underlying problem is a failure to recognize that these transitions often break up their informal positive social support systems. Governments and community groups need to help people establish or re-establish these networks, not just support them financially. People exiting a system (for example, the criminal justice and child welfare systems) need to be connected to new communities, new ways of living, and positive people.

Trauma-informed care is essential

It is so hard to share our private experiences when we don’t need to.

We heard that people often experience trauma as they move between systems, and that it is important that service providers are trauma-informed. Continuity of connection with caregivers can support children, youth and adults as they move through systems. A lack of trauma-informed care can make services re-traumatizing, and make people not want to access them. For example, some healthcare professionals do not have training in trauma-informed care. As a result, many people experiencing homelessness, mental health and/or addictions issues face stigma when accessing services. We must also consider intergenerational trauma (for example, because of colonialism). Children in families confronting these issues are also in need of supports.

Social prescribing offers a more holistic approach to caring for people

On a few occasions, participants raised the idea of social prescribing—prescribing non-medical treatments and referring people to community services that can help them connect with activities for their health and wellbeing. Examples include spending time in nature (with a park pass), fitness activities (with a recreational facility pass), and connecting people with affordable housing access to food, etc.

The non-profit sector is one of the most dynamic, responsive and resilient parts of our social safety net.

Community-based organizations need long-term, flexible, sustainable base funding to meet complex needs

NGOS are overworked and underserved.

It takes significant human and financial resources to provide targeted yet comprehensive services and supports for people with complex needs. However, funding is often specific to a program or service focused on meeting a single need (for example, employment or housing). This makes it more difficult for organizations to focus on the long-term preventive supports and services that are most effective and culturally safe. Narrowly focused programs compartmentalize solutions, but individuals have complicated needs that require broad and flexible responses.

We heard that community-based organizations and service providers should receive sustainable and equitable funding to offer a broader range of services. Trust is so important for people who are seeking supports. Community-based organizations have their trust, but not the resources to tailor their approaches to what people need.

For example, youth told us that community-based organizations have helped them with things like:

- school enrollment

- homework

- sports training, to help achieve goals

- summer volunteer opportunities

They also stressed the need for more availability of such services.

I am so used to just dreaming about having things but getting the support to be able to work towards my goals really helps.

Sustainable and sufficient funding would also allow organizations to pay decent wages and benefits to their staff. Many working in community-based or non-profit organizations are underpaid, and organizations must fundraise much of their budget. We heard that people working in community social services sometimes have to use foodbanks themselves. Female workers dominate this sector and often have lower incomes than in other areas. This, coupled with lesser access to benefits, means they are at greater risk of poverty in retirement.

The non-profit sector continues to take on increasing responsibility for people’s health, social and economic wellbeing. However, they do not receive adequate funding to do so. Whether it is an unintended consequence or by design, the current safety net relies a lot on non-profits.

Better collaboration is needed to ensure access to benefits and services

More coordination would be a great step forward.

Automatic enrolment can increase access to benefits

Participants emphasized the need for real efforts to simplify access to benefits and supports, including those that are dependent on filing personal income tax. We heard from many participants that lack of information, misinformation, complicated application forms and long processing times dissuade people from following through or deter them from applying to begin with. Many people expressed that automatic tax filing, automatic enrollment for programs and benefits, and automatic renewal could help to increase take-up of needed benefits and supports for which people are eligible and entitled. There is a belief that the Government of Canada has the necessary information to do this, and could therefore shift the burden from individuals, removing barriers for those made most marginal.

Systems navigators can be a vital tool for people navigating systems and transitioning between them

Navigators represent the dysfunction of the system—why do we have a system that needs navigators?

Systems are antiquated and complex. Eligibility criteria are rigid and hard to understand, even for workers, let alone individuals. In addition, the social safety net is not comprised of a single system, but multiple systems (health, social services, justice, child welfare, etc.) controlled by multiple levels of government. There are also supports and services provided by the non-profit sector. The lack of coordination between these systems causes some people give up when trying to access transition support. Without allies and advocates, navigating complex systems feels impossible. Navigators can help people access supports before a transition, so they do not need to transition in the first place. There is great demand for system navigators (those who have worked in various programs) who can advocate and assist with paperwork or establishing networks.

Literacy level and comprehension level are often low so people cannot understand the information provided or how to access services. The onus should be on the Government of Canada to facilitate access to programs. However, individuals in a liaison role can help participants with lower literacy or comprehension levels by using understandable and culturally appropriate language.

Despite significant support for systems navigators as a tool to increase benefit uptake, some pointed to the need for systems navigators as a problem in itself. They advocate for simplifying systems instead of adding more complexity through navigators.

Participants shared specific solutions for improved coordination including:

- community hubs as one-stop resources to help with communication and coordination

- public servants dedicated to work specifically with community-based organizations—this could take the form, for example, of a multi-agency helpline where people can learn about services from all levels of government and non-profit organizations

- systems mapping to help to identify how systems are connected and how they interact to create obstacles or unintended negative consequences

- wraparound services

- inclusion of families in supports for children and youth, for example allowing families to receive support to help reduce the level of youth homelessness (when it is safe to do so)

Information sharing can improve services for people experiencing poverty

It is traumatizing for people to have to retell (and relive) the reasons why they need help. Information sharing within and between governments can reduce this burden.

Privacy legislation can make it difficult to share information. We heard that people do not understand the legislation well. Therefore, they err on the side of less information sharing. This leads to people falling through the cracks. It was suggested that we develop a system that puts the control of information in the hands of people accessing supports, allowing them to easily share with government and service providers as needed.

Need to help those who are in deep poverty

How do I get out of it?

The social safety net currently helps those hovering close to the poverty line, but not those furthest behind. We have seen significant strides in poverty reduction, but they are not reaching all people equally. The Government of Canada needs to mobilize resources and deliver them to the most disadvantaged groups.

People with disabilities need targeted supports

The social safety net does not adequately address the needs of people with disabilities. Targeted supports are necessary. Benefits and supports often do not reflect the additional costs associated with living with a disability. For example, affordable and accessible housing is in short supply, to the detriment of those who need it.

We also heard about the high clawback rate of employment income that is often part of disability supports. These clawbacks limit the ability to work and earn additional income, trapping people in poverty.

Employment Equity is an effective tool and should be more broadly applied

For me, as a person with multiple disabilities, I think many employers are afraid to hire me. Sign language interpreters cost a lot to provide access. It seems we are cast aside and forgotten.

Many participants spoke about discrimination in the workforce. There is a strong business case to be made for a diverse workforce. However, employers may need an incentive to build a more diverse workforce and to provide employment that is more flexible. One of the most powerful tools for equity, fairness and racial justice is strong employment equity legislation. Employment equity needs to be applied federally, provincially/territorially and municipally, and existing frameworks need to be expanded to include 2SLGBTQ individuals. Equity programs/frameworks also need to be adequately resourced, monitored, audited and enforced as we "build back better." Employment equity can help foster greater labour market participation and all of the benefits that come along with it.

Children and youth in care need more supports

Every child coming in to the foster care system has trauma, even babies.

Once children and youth in care turn 18 and leave the child welfare system, they lose supports that are often not picked up by other programs for young adults. Addressing what a young person will need once they leave care is key to preventing poverty. It is also important to recognize that every child coming into the child welfare system has trauma, even babies. These traumas need to be addressed as early as possible. This will allow children and youth the best possible outcomes once they are out of the system. Importantly, wraparound supports and services should be in place to keep kids from being removed from their families in the first place. We heard about children who are removed from their parents as a result of living in poverty and placed into care. Participants stressed the need to support children’s families in the first place so they can stay together.

It is a tragedy that young Indigenous families have their children torn away from them not because they’re bad parents, but because they’re in poverty.

Participants also spoke to the need to provide supports not just for youth from care, but also children who leave their families (for example to escape violence or because of rejection for 2SLGBTQ youth). They require trauma-informed supports to avoid poverty, homelessness and further violence.

When you’re in care, you have so much trauma—I don’t think I lived my first ‘healthy’ year until I was 24—before that, I lived in a constant state of crisis.

Some participants noted that people living in institutions are stripped of their identities and given new ones by the system. They become a “youth in care.” As a result, their desires, needs and voices are less valuable than the views of social workers, staff, and the institutions themselves. Children and youth in care are blamed and punished for standing up for themselves, or for trying to escape the trauma and abuse that they are exposed to in care.

I’ve been so stigmatized to think that I’m less than because I was in care, I’m less than because I don’t have parents, I’m less than because of my mental health—I don’t feel like I am qualified to be someone.

Additionally, many participants stressed the need to provide supports to families before their kids are taken into care. They pointed to the contradiction of removing children from their families due to poverty, and then financially supporting them in care.

Poverty reduction will not work without affordable housing

Housing First approach helps people get back on their feet

Everything fell apart without housing.

There is a housing crisis, and if it is not addressed, poverty will not be addressed. Housing is the single greatest cost for individuals and families, and affordable housing is increasingly out of reach. A ‘housing first’ approach is important because, as one participant noted, “everything falls apart without housing.”

56 years old and homeless for the first time. I thought I would be dead within the week.

First-person experience – Housing: Safety is paramount

Living in poverty can often mean a lack of choices and a lack of mobility. Housing costs can leave people trapped in situations where they do not feel safe.