Blueprint for Transformation: the 2023 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of tables

- Dedication

- Message from the Chair

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1 - Introduction

- Chapter 2 - What we know

- Chapter 3 - What we heard

- Chapter 4 - What now: A call to action

- References

- Appendix A - Recommendations from previous reports of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

- Appendix B - Progress on the Government of Canada's commitments and investments

- Appendix C - Organizations that participated in engagement sessions

- Appendix D - Other data tables

Alternate formats

Blueprint for Transformation: the 2023 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty [PDF - 1.6 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQ+

- 2-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CIS

- Canadian Income Survey

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- GBA+

- gender-based analysis plus

- GST/HST

- goods and services tax/harmonized sales tax

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- MBM

- Market Basket Measure

- MBM-N

- Northern Market Basket Measure

- NEET

- not in employment, education or training

- NHS

- National Housing Strategy

- PiT

- point in time

- PRS

- Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy

- QoL

- Quality of Life

- SDGs

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

List of tables

- Table 1 – Poverty rate change by province and territory, 2020 to 2021 and 2015 to 2021

- Table 2 – Poverty rate changes by demographic group, 2020 to 2021 and 2015 to 2021

- Table 3 – Gap between estimated annualized minimum wage income (after deducting income tax and EI and CPP contributions) for full-time minimum wage earners and MBM thresholds – 2021

- Table 4 – Highest and lowest annual welfare income among provinces and gaps with respect to Market Basket Measure (MBM) thresholds, 2021

- Table 5 – Market Basket Measure (MBM) Thresholds for the MBM reference family, 12-month change average of the 53 MBM regions in the provinces, 2015 to 2022

- Table 6 – Change in persons living in a household that experienced moderate or severe food insecurity by selected demographic groups, 2020 and 2021

- Table 7 – Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Dignity

- Table 8 – Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Opportunity and Inclusion

- Table 9 – Summary of multi-dimensional poverty indicator trends – Resilience and Security

- Table 10 – Number of people in poverty and poverty rate by demographic group, 2015, 2020, and 2021

Dedication

The National Advisory Council on Poverty dedicates our 2023 progress report to all those people who selflessly shared their stories of success and struggle, with the hope that their expertise will enable better systems for everyone. You are the thread that binds this report.

Message from the Chair

I am pleased to present, on behalf of the National Advisory Council on Poverty, our 2023 report on the progress of Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS). For this report, we engaged in person for the first time since the start of the pandemic. We discovered that the reality of poverty in 2022 and 2023 is very different from how it was in 2020.

This year we heard about many of the same challenges from all different corners of the country, including:

- housing

- food security

- transportation

- mental health supports

- racism

- discrimination

- wages

- income support

- stigma

These barriers and the way they cruelly interconnect continue to limit the individual and collective potential of our country. Now more than ever, we must give voice to the experiences of people living in poverty. We must follow their lead as we seek long-term, sustainable solutions for our future.

We commend and thank all those people, organizations and institutions that dedicate themselves to reducing poverty. Poverty reduction is a huge undertaking that requires a multi-pronged approach to be engaging, effective and equitable. We feel strongly that it is possible to decrease poverty, as we have seen it. The pandemic can act as a turning point if we, as a society, let it. We saw firsthand how quickly people can come together and how systems can shift swiftly for the better.

We must, as a country, continue to take audacious, strategic action so that everyone in Canada has the opportunity and means to thrive. We think that our recommendations offer a realistic blueprint for sustainably reducing poverty and building a more equitable country.

We don’t know what poverty will look like in the future. However, unless we all act together, we think that those who are made most marginal will continue to bear the brunt of societal challenges, such as:

- climate change

- housing

- health

- employment

- addiction

- food security

- loneliness and social isolation

In some cases, we as a society need to do things in a different way. In other cases, more of what is already being done is needed. Either way, governments must continue to act courageously for Canada and all those living here.

Thank you,

Scott MacAfee

Chair, NACP

Executive summary

The past 3 years have been unprecedented in recent history. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted our health, economic and social systems in massive ways. The public health, education, social services and employment sectors had no choice but to adapt. In some cases, these adaptations revealed new ways of doing things. In other cases, temporary measures were dropped. These changes greatly affected household incomes, government transfers and wages. Society will feel the impacts of the pandemic for years to come. The impacts were not only related to health and incomes. There were some deliberate choices that made people more marginalized. Some people also used the responses to the economic and health impacts of the pandemic to drive people apart. We can see this with hatred, discrimination and vile political discourse that is increasingly directed at specific groups of people who are already made marginal.

While COVID-19 still threatens communities in Canada and around the world, the public health measures have largely been lifted. Temporary economic measures have also ended. At the same time, Canada is also dealing with high inflation and rising interest rates. These issues are making it challenging for many people to meet their basic needs. This contributed to rising poverty rates in 2021. Estimates also suggest further increases in 2022. There is a 1.5-year lag in the availability of annual poverty statistics. This means the impacts of the rising cost of living have only begun to show up in the data. However, rising costs and the removal of temporary pandemic benefits in 2020 and 2021, are likely to have contributed to increasing poverty rates in 2022.

Society can learn many lessons from the pandemic. An important one is the need to adapt existing measures to meet the needs of those made most marginal. Despite low-barrier access, emergency income benefits still often did not reach those made most marginal. There was an overall message of “building back better.” However, we think the focus should be on “building back fairer.”

This year, we held our first in-person engagement sessions since the COVID-19 pandemic alongside targeted virtual sessions. This allowed us to gain firsthand knowledge of poverty in 2022 and uncover policy levers that would change the reality. It has been a privilege to speak to people with lived expertise of poverty, stakeholders, community organizations and experts in their fields. The overall themes that we heard largely reinforce what we have heard in past years, namely:

- income inadequacy and impact of the rising cost of living

- the need to make equity and inclusion a priority

- challenges faced by specific populations made most marginal

- challenges accessing benefits and services

We continued to hear about the inadequacy of income and income supports. The adequacy of employment income and government income support programs have not kept pace with demand for workers. This is happening during a period of low unemployment rates and high corporate profit-taking. Inflation and increases in the cost of living have made the inadequacy worse. Rising food and housing costs have led more people living in Canada to struggle to get by. Increasing interest and borrowing rates, expensive rents and low housing stock are exacerbating the existing housing crisis country-wide.

Discrimination and racism continue to play a big role in creating and perpetuating poverty. Interventions will continue to create or reinforce inequity, specifically the economic, political, social and health disparities of racialized people, unless equity issues are the focus.

Throughout our engagement sessions, we heard about the specific challenges faced by many of the populations made most marginal. While there were many commonalities, some challenges are specific to each population. We also heard about a lack of targeted and specific supports for many groups made marginal. These are populations that disproportionally experience:

- poverty

- food insecurity

- houselessness

- low wages

- poor mental health

- higher levels of chronic disease

- isolation and loneliness

As in past years, we continued to hear about how hard accessing benefits and services is for many people. We particularly heard this from people with multiple identities within marginalized communities. We heard that we need to increase benefits and reduce the administrative burden of access. Low-barrier, increased benefits were provided early in the pandemic, and they had a real material impact on communities.

Data from the 2021 Canadian Income Survey (CIS) show an increase in the overall poverty rate compared to 2020. This is the first time since the Poverty Reduction Strategy was implemented that the poverty rate increased. In 2021, there were about 405,000 more people living in poverty than in 2020. Canada’s overall poverty rate rose by 1.0 percentage point to 7.4%, up from 6.4% in 2020. This is equal to a 15.6% increase in the poverty rate between 2020 and 2021. Although this number is up from 2020, there were 2.3 million fewer people living in poverty compared to 2015. The overall poverty rate in 2021 was close to half the level recorded in 2015.

Over the past 3 years, this Council has made several recommendations that have identified important areas of government action intended to reduce poverty. These recommendations were made by examining existing data and engaging extensively with:

- people with lived expertise of poverty

- stakeholders

- community and advocacy organizations

- academics and experts in the field

This advice also builds on the expertise and experience of the Council members. For this reason, we have chosen to use this report to urge the Government of Canada to take urgent action in the following 5 areas. We strongly believe that these recommendations, implemented collectively, would create a stronger, simpler, more equitable and proactive safety net. They will help reduce poverty, support those who need it most and create a more equitable and inclusive society.

Urgent action to decrease First Nations, Inuit and Métis poverty

The Council believes that the fact that colonial practices, racist policies and programs, and discrimination have created and perpetuated poverty in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities is egregious and shocking. Despite recent investments towards reconciliation, the Government of Canada must continue to work to earn the trust of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people to make much needed progress in reducing poverty for Indigenous people.

Dignity, equity, and inclusion

We know that some groups have been made most marginal through racism and discrimination. The Government of Canada must continue to support equity-enabling efforts (Canada Disability Benefit, Black Entrepreneurs, Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care). It must also challenge any and all discriminatory ideologies that impede equity in policy development and programming.

Income adequacy

We have heard consistently every year that existing government benefits and minimum wage are insufficient to meet people’s needs. Record inflation rates and increases in the cost of living have made this much worse.

The Government of Canada should work with the provinces and territories to establish, by 2030, an income floor above Canada’s Official Poverty Line, whether it be through employment income, income supports including social assistance, new or existing targeted supports or a combination of the 3.

Increasing access to benefits and services

We continue to hear that our current social safety net is complex, difficult to access, inefficient, outdated, inadequate and stigmatizing. Navigating this fragmented and complicated maze can be traumatizing for people who have already been made most marginal in society.

The Government of Canada should streamline benefits to make them low-barrier, easier to access and more responsive to individual needs.

Prevention and protection

Poverty reduction efforts often primarily focus on lifting people out of poverty. However, we stress the need to invest in keeping people from falling into poverty in the first place.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Where we started

Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy and the creation of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

In 2018, the Government of Canada released Opportunity for All – Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy ("the PRS"). The PRS set a vision and foundation for future government investments in poverty reduction. This foundation included:

- establishing an official measure of poverty, Canada's Official Poverty Line, based on the Market Basket Measure

- setting concrete poverty reduction targets to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030, relative to 2015 levels. In 2015, the poverty rate was 14.5%, representing over 5 million Canadians living in poverty

- creating a National Advisory Council on Poverty (established in 2019) to:

- advise the Government on poverty reduction

- report publicly on the progress made toward meeting the targets every year

- foster a national dialogue on poverty reduction

- passing the Poverty Reduction Act, which entrenches the targets, Canada's Official Poverty Line, and the Council in law

Building relationships

Over the years, the Council has cultivated a strong network of persons with lived expertise of poverty, community leaders, experts, academics and practitioners working to end poverty in Canada. The pandemic shortened the Council's in-person engagement in 2020, but we adapted by adopting first a virtual, then a hybrid approach. Since then, we have spoken to more than 1000 people on poverty-related issues that matter to them most. We are grateful for their time and willingness to share their knowledge, experiences, and advice. We strive to honour what we heard in our reports and recommendations.

Investments in poverty reduction since 2018

Since the release of the PRS in 2018, the Government of Canada has made significant investments with expected impacts on poverty reduction. We recognize that these are important investments and encourage the Government to continue with their prompt implementation. These include investments for Canada-wide:

- affordable, accessible and quality early learning and child care

- dental care for low-income Canadians

- enhanced targeted benefits such as the Guaranteed Income Supplement, Old Age Security, Canada Child Benefit and Canada Workers Benefit

- targets for reducing housing need and homelessness in the National Housing Strategy

- Disaggregated Data Action Plan for more representative data collection and enhanced statistics on diverse populations

The Government of Canada likewise announced several commitments in Budget 2023 that we hope will positively impact poverty. These include commitments to:

- increase funding to implement the National Action Plan to End the Tragedy of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- expand the Canadian Dental Care Plan and establish an Oral Health Access Fund to address health gaps among vulnerable populations and reduce barriers to access

- increase funding to develop the Canada Disability Benefit and investments in building the capacity of disability organizations

- increase the eligibility for automatic tax filing through the File My Return program and pilot a new automatic tax filing service for vulnerable Canadians

A more complete list of Government of Canada commitments and investments is available in Appendix B.

Groups made most marginal

Throughout our reports, we refer to specific groups that are underserved and overlooked. These groups face structural and systemic barriers, violence and discrimination, racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, ableism, and colonialism. This makes them more likely to live in poverty. When we refer to groups made most marginal, these are who we are referring to (in alphabetical order):

- 2-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (2SLGBTQ+) people

- Black and other racialized communities

- children and youth in care

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis people

- people who are experiencing houselessness

- people who are involved in the criminal justice system

- people who are living in institutions (such as long-term care homes)

- people who are living in rural and/or remote areas

- people who have emigrated to Canada

- people with disabilities

- people with refugee status or who are undocumented or non-status

- women

Intersectionality

Poverty is multi-faceted, and it affects some groups more than others. Intersectionality refers to the complex and cumulative ways in which the effects of these multiple forms of discrimination combine, overlap or intersect, especially in the experiences of groups made most marginal.

Individuals simultaneously have multiple social identities which all contribute to their unique experiences in society. These identities are formed through experiences of living and existing in different and sometimes overlapping groups based on:

- race

- ability

- class

- gender

- sexuality

- age

- other marginalizing characteristics

For any person, certain social identities may be marginalized due to discrimination, while others are not. The greater number of marginalized identities a person has, the greater their risk of poverty.

Building an equitable and resilient social safety net and system means including everyone in poverty reduction efforts. Equity needs to be a priority when developing policies and programs aimed at reducing poverty. Otherwise, we will continue to leave those made most marginal behind.

Taking stock of progress in poverty reduction

The last 4 years saw significant progress in poverty reduction as well as vast societal disruption. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed serious gaps in our social safety net. Groups made most marginal were more likely to face severe health, social and economic outcomes. Some individuals and families who were not vulnerable to poverty before required help to get by.

Early in the pandemic, the Government of Canada provided unprecedented income support to individuals and families. These supports intended to replace income due to the employment disruptions caused by pandemic responses. However, they also had an impact on poverty reduction. We reported on this in the 2020 report.

However, the emergency response measures did not help everyone equitably. Certain groups made most marginal were not entitled to these benefits at all. For example, new labour market entrants or lower income earners may not have met the minimum earned income threshold to qualify for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Some people faced benefit clawbacks because their incomes temporarily increased. Others must now pay back benefits for which they belatedly learned they did not qualify. Minimum wage earners, among other groups, may have fewer assets and savings to repay any benefits they received. At the same time, they continue to pay for necessities during a cost-of-living crisis.

Despite these shortcomings, emergency benefits significantly lowered poverty rates, which were already on a steady decline since 2015. These response measures have since ended. Rising inflation and cost of living are causing renewed precarity across Canada. We see this through poverty rates that increased for the first time since the PRS was introduced.

Further, we as a council have consistently stressed that progress in poverty reduction has not been equitable. Groups made most marginal continue to face:

- structural and systemic barriers in our society

- violence

- discrimination

- racism

- homophobia

- transphobia

- sexism

- ableism

- colonialism

Many of these groups are underrepresented in or absent from our poverty data. Many are also underserved or unserved by government benefits and supports. Reasons for this include barriers to access or stringent eligibility criteria. For example, the tax system is used to determine income-tested benefits. However, we know that the tax filing rate for racialized people is lower. Reaching Canada's poverty reduction targets is not enough if those furthest behind do not benefit equitably from our progress.

Our previous reports and recommendations

In our past 3 reports, the Council made recommendations on how to reduce poverty in Canada. These recommendations are based on what the Council heard during engagement with persons with lived expertise of poverty, stakeholders, community organizations and experts in the field, and qualitative and quantitative data. The recommendations align along 5 broad themes. In short, the Council recommended that the Government of Canada:

- take urgent and immediate action to reduce poverty among First Nations, Inuit and Métis people, including through co-development of Indigenous indicators of poverty

- address income inadequacy by establishing an income floor above Canada's Official Poverty Line, whether it be through employment income, income supports, new or existing targeted supports, or a combination of the 3

- develop targeted policies and programs that create greater equity, including a commitment to reduce poverty by at least 50% by 2030 for groups made most marginal, and collect and use disaggregated data on these groups to ensure programs reach those who need them most

- increase awareness of, access to and availability of government benefits and supports; ensure persons with lived expertise of poverty are at the centre of design, implementation and evaluation of these policies

- strengthen efforts in early intervention and prevention of poverty with a focus on groups made most marginal, especially children and youth; provide sustainable support for organizations working on the frontlines in this field

The Council reaffirms our past recommendations and continues to call for their urgent implementation. The full list of recommendations is in Appendix A.

Where we are now

What we heard

"There's no hope. The cost of living is too high, rent is too high. Inflation is making everything worse."

In fiscal year 2022 to 2023, the Council held in-person engagement sessions. These took place in Abbotsford, Huntington, Montreal, Ottawa, Regina, Surrey, Toronto, Salaberry de Valleyfield, and Vancouver. The Council also held virtual small-group sessions with participants from across the country. We spoke with diverse groups of people. This included persons with lived expertise of poverty, community organizations and practitioners, academics and other stakeholders. For the first time, we also met with youth in person. We spoke about their thoughts on and experiences of poverty.

This year we noted a growing sense of hopelessness and desperation. Persons with lived expertise of poverty and service providers alike told us that things seem worse now than they were before and during the first years of the pandemic. We heard that people are worried about the rising cost of living and inflation. More people are in crisis, and these crises are more visible in our communities. Many communities lack stable employment opportunities, decent and affordable housing, food, child care, transportation, health care, and other necessary infrastructure for individuals to thrive. We heard that community organizations and their staff are overworked and demoralized. They lack the resources to help everyone who needs it.

In our past engagements, stakeholders expressed optimism around the influx of more inclusive and generous pandemic benefits. Many expressed hope that the lesson of the pandemic would be that we can and must work together to do things in a different way. This year, we heard that instead of coming together as a society, people are pulling away. We heard that those experiencing poverty are feeling more othered.

We heard that chronic issues are becoming more acute. These include inadequate income, unmet housing needs and houselessness, food insecurity and worsening physical and mental health, among others. We heard that groups made most marginal continue to have disproportionately high rates of poverty. We also heard that systemic violence and discrimination, racism, colonialism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, sexism and structural barriers remain serious issues. The lasting impacts of the pandemic and the worsening economic situation are putting added pressures on everyone. This is especially true for those in deep poverty and those at risk of falling into poverty.

What the data says

The Council's first 3 reports noted that between 2015 and 2020, poverty rates in Canada were decreasing. Last year, we reported that according to Canada's Official Poverty Line, the poverty rate fell from 14.5% in 2015 to 6.4% in 2020. As a result, Canada reached its goal of reducing poverty by 50% by 2030, 10 years ahead of time.

However, as we emphasized in our last report, 2020 was an outlier. Temporary pandemic response measures played an outsized role in rapidly declining poverty rates. Existing and new pressures, including record high inflation and a cost-of-living crisis, mean that our poverty rate is increasing. We also know that poverty reduction has not been equitable. Certain groups made most marginal continue to face disproportionately high rates of poverty.

Data from the 2021 Canadian Income Survey (CIS) show an increase in the poverty rate compared to 2020. This is the first time since the PRS was implemented that poverty increased. In 2021, there were about 405,000 more people living in poverty than in 2020. Canada's overall poverty rate rose by 1.0 percentage point to 7.4%, up from 6.4% in 2020. This is equal to a 15.6% increase in the poverty rate between 2020 and 2021. Although this number is up from 2020, there were 2.3 million fewer people living in poverty compared to 2015. This represents a decrease of 49.0% in the poverty rate compared to 2015 (14.5%).

Where we are going

Upcoming challenges

"We will work towards the reduction of poverty, but we support the 100% elimination of poverty in this country."

Since it started, the Council has endeavored to focus on the chronic causes and consequences of poverty in Canada. However, we could not fully explore some issues with increasing challenges in our reports thus far. We encourage the next iteration of the Council to pursue these issues deeply. We also encourage them to identify how poverty is embedded into certain social structures and explore effective solutions. Some, but not all, of these issues are listed below.

Longstanding issues

Inequalities in poverty

Our current systems perpetuate existing inequalities. This contributes to disproportionately higher poverty rates among groups made most marginal. Targeted approaches should try to address specific issues facing specific groups made most marginal. These approaches should acknowledge their unique contexts and risk factors for poverty. This is in line with Canada's commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs endeavour to "leave no one behind" and "reach the furthest behind first".

Health and poverty

Health and poverty are inextricably linked. The pandemic brought this into stark relief. People living in poverty were disproportionately represented among the people who died from COVID-19 and experienced significant excess mortality. We do not yet know the scale of long-term and potentially permanent effects on people's physical and mental health. Beyond COVID-19, we know that the social determinants of health, including low income and experiences of discrimination, among others, contribute to continued health inequities.

Housing crisis

The Council has heard repeatedly that the housing crisis is getting worse. Rising rents, interest rates and a lack of affordable housing is putting pressure on people living in poverty. It has also put pressure on those living on middle incomes. Service providers spoke to a significant rise in houselessness and encampments. Many called for an increase in housing offering wraparound supports to address individuals' complex and unique needs.

Climate change and poverty

Globally, people living in poverty are most likely to experience the negative impacts of climate change. Canada continues to face extreme weather linked to climate change. It is vital that our efforts address resiliency and protect those most at risk.

Contextual issues

Inflation and high cost of living

Globally, we are in an inflationary period. There is a rising cost of living, especially for essentials such as food and housing. The full impacts of inflation on poverty are yet to be fully realized. The worsening economic situation continues to put pressures on those already living in poverty and those on the margins. It is even putting pressure on those living on middle incomes.

Strained frontline services

During its recent engagement, the Council heard that frontline workers and service providers are struggling. Many organizations in the voluntary sector reported underfunding and high case loads. They are often providing services and supports beyond their mandates, to compensate for gaps and/or growing complex needs. As the pandemic has progressed, so have feelings of burnout and labour shortages in essential services. This includes shortages in primary and emergency care and early childhood education.

"We keep returning to the system. Everything goes back to the incapacity of the system to help people."

Transforming our Systems: The 2022 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty, was tabled in Parliament on October 17, 2022. This coincided with the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. Our report spoke to decreases in the poverty rate since 2015. However, we now know that some of these gains were temporary. Urgent action is needed for Canada to meet its 2030 poverty reduction targets as a steppingstone to eradicating poverty.

The Council has made a series of recommendations over the past 3 years. We are taking this opportunity to reiterate them. In a time of growing disparities, it is imperative that we come together to take bold action. We believe our recommendations are more salient than ever to address the challenges we face as a society.

We urge the Government of Canada to strengthen existing benefits and supports and invest in new ones that target those furthest behind first. Many of our systems alienate the people who need them most. Individuals in poverty have complex and intersecting needs. There is a sense that greater efforts are made towards safeguarding our social safety net from fraud or from those deemed undeserving, than expanding and reimagining it so that it protects everyone.

One of our engagement participants said: "While poverty is not only about income, it is always about income." We agree. People need adequate income to thrive in Canada. Working together, all levels of government, the private sector and civil society have a role to play. At the same time, we cannot neglect non-income factors, including access to:

- adequate and affordable housing

- transportation

- food

- physical and mental health supports

- education

- opportunities for civic participation

- culture

- leisure

We need to create an environment which fosters social inclusion.

Chapter 2 – What we know

Notes about data

How poverty is measured

The Poverty Reduction Act (2019) established an Official Poverty Line for Canada based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM). According to the MBM, poverty thresholds are based on the cost of a basket of food, clothing, shelter, transportation and other items representing a modest, basic standard of living. The current MBM establishes thresholds for 53 different geographic regions in the provinces, which can be adjusted to families of different sizes. When a person's or family's disposable income is below the threshold for the size of their family in a particular region, they are considered to be living in poverty.

The Northern Market Basket Measure (MBM-N) for the Yukon and Northwest Territories uses similar methodology to the MBM. However, it accounts for adjustments needed to reflect life in these territories. Statistics Canada officialised the MBM-N for the Yukon and Northwest Territories in 2022 (Devin, Gustajtis, & McDermott, 2022). The creation of the MBM-N starts to fill a major gap in our poverty statistics.

Poverty statistics are not produced for people living in Nunavut at this time. However, work is ongoing to develop an MBM-N for Nunavut.

Missing data for certain populations

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people

Official poverty statistics are missing for First Nations people living on reserve, persons living in Métis settlements and persons living in settlements across the Inuit Nunangat. This is a significant data gap for Indigenous people in Canada. For this reason, these groups are not equitably present in the data chapter. However, from the existing data, we know that Indigenous people are at a higher risk of living in poverty. The Government of Canada is working with First Nations, Inuit and Métis people to co-develop distinctions-based Indigenous indicators of poverty and wellbeing. Despite this, serious gaps still exist.

We consider the limited availability of social and economic indicators for Indigenous people to be problematic. We have repeatedly noted the need for the Government of Canada to work with Indigenous people to reconcile the shameful legacy of colonial practices. These practices have caused high levels of poverty among First Nations, Inuit and Métis people. We continue to call on Canada to undertake actions of reparation. Further, we call on Canada to restore Indigenous people to their rightful economic, political and social place.

Other groups made most marginal

The following groups are under-surveyed or not surveyed at all:

- people living in institutions

- 2SLGBTQ+ people

- people seeking asylum

- people with refugee status

- people with temporary protected status

- people experiencing houselessness

Thus, MBM and poverty statistics are also missing for these groups. We know from available evidence, including from engagement sessions, that these groups are made most marginal and are most underserved. These groups and the individuals within them have unique experiences of poverty. This further emphasizes the need to collect data and publish indicators that capture these experiences. Their inclusion would allow measurement of the impact of policies between and within groups. This would help build understanding as to whether policies are equally benefiting those made most marginal. This would inform equitable policy and program design and implementation.

We also recognize that poverty rates and the impact of poverty are different among children of different ages. They also differ between children at different stages of development and children of families with multiple marginalized identities. Experiencing poverty in childhood can have significant long-term consequences for children. Poverty disrupts the present and future well-being of children as well as the future well-being of Canada. Poverty statistics are not available for children belonging to some groups made most marginal. For example, information on disability status, Indigenous identity and immigration status is only collected or disseminated for persons aged 16 years or older. This data is important for understanding and addressing existing gaps and inequities in poverty reduction efforts. It is also important for preventing child poverty.

Poverty statistics for racialized groups have only been available since the 2020 Canadian Income Survey (CIS). Thus, we cannot measure progress in poverty reduction for racialized groups relative to the targets established in 2015.

Canadian Income Survey (CIS)

Poverty rates based on Canada's Official Poverty Line are estimated using annual results from the CIS. The CIS data has an approximate 15-month lag between a specific reference year and when the results become available. The most current poverty statistics come from the 2021 CIS. Data for Canada's provinces was released on May 2, 2023.

Indicators of poverty

Income is often used to measure poverty. But income alone fails to capture the full experience of living in poverty. The PRS established a dashboard of several indicators related to poverty. The dashboard is not comprehensive but allows progress to be tracked across several dimensions of poverty.

Tables 7 to 10 in Appendix D summarize the progress made on each of the poverty indicators since 2015. We have highlighted several indicators that align with the themes we heard in our engagement sessions throughout the chapter.

Data limitations make it difficult to track trends across all indicators of poverty for groups made most marginal. We have outlined this disparity in our past reports and made recommendations to remediate data gaps for these groups.

Comparing 'What we heard' and the data

The poverty landscape in Canada is not constant. It can change rapidly. We rely on both quantitative data from the CIS and qualitative data from engagement. This helps us understand all aspects of poverty in Canada. Of note, our engagement sessions for this report took place in fall 2022 and winter 2023. This means that there may be differences between what we heard and what the 2021 data supports. We believe that data from the 2022 and 2023 CIS will better align with what we heard this year. In the interim, we have used relevant 2022 data from alternate sources to help us better understand and more accurately reflect the themes discussed during our engagement.

Poverty rate trend in Canada

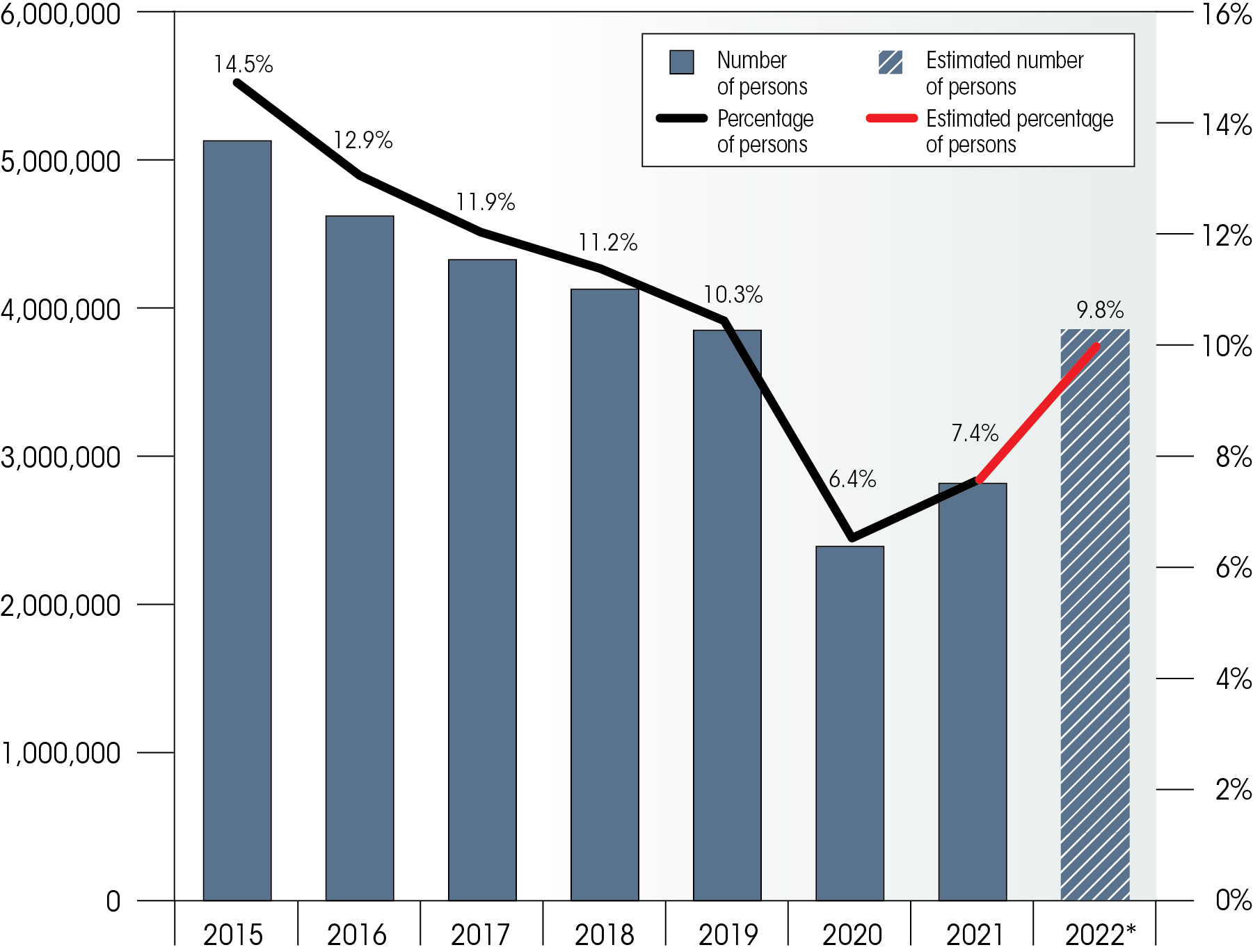

In 2015, the baseline year for measuring progress on the legislated poverty reduction targets, Canada's overall poverty rate was estimated to be 14.5%. From 2015 to 2019, the poverty rate trended downwards steadily. It decreased to 12.9% in 2016, 11.9% in 2017, 11.2% in 2018, and 10.3% in 2019. In 2020, there was a large decrease in the overall poverty rate, which dropped to 6.4%. In other words, Canada's overall poverty rate had decreased by 56% compared to 2015. This meant Canada had reached its commitment under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to reduce poverty by 50% by 2030. However, the large decrease in poverty in 2020 was primarily the result of temporary COVID-19 emergency benefits. The graph below shows these trends as well as the official poverty rate for 2021. We have also chosen to discuss projected trends by including the provisional poverty rate for 2022. This allows us to better contextualize what we heard during our engagement.

Text description of Graph 1

| Year | Number of persons in poverty | Percentage of persons in poverty |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 5,044,000 | 14.5% |

| 2016 | 4,552,000 | 12.9% |

| 2017 | 4,260,000 | 11.9% |

| 2018 | 4,065,000 | 11.2% |

| 2019 | 3,793,000 | 10.3% |

| 2020 | 2,357,000 | 6.4% |

| 2021 | 2,762,000 | 7.4% |

| 2022* | 3,794,000 (Estimated) | 9.8% (Provisional) |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 11-10-0135-01 Low income statistics by age, sex and economic family type.

- Note: * The provisional poverty rate shown for 2022 is an estimate based on modeling (Heisz & Gustajtis, 2023). We estimated the number of persons living in poverty in 2022 using the 2022 provisional poverty rate and the average of the 2022 quarterly population estimates for Canada's provinces (author's calculation). Official poverty rate estimates for 2022 will be available with the release of the 2022 CIS in 2024.

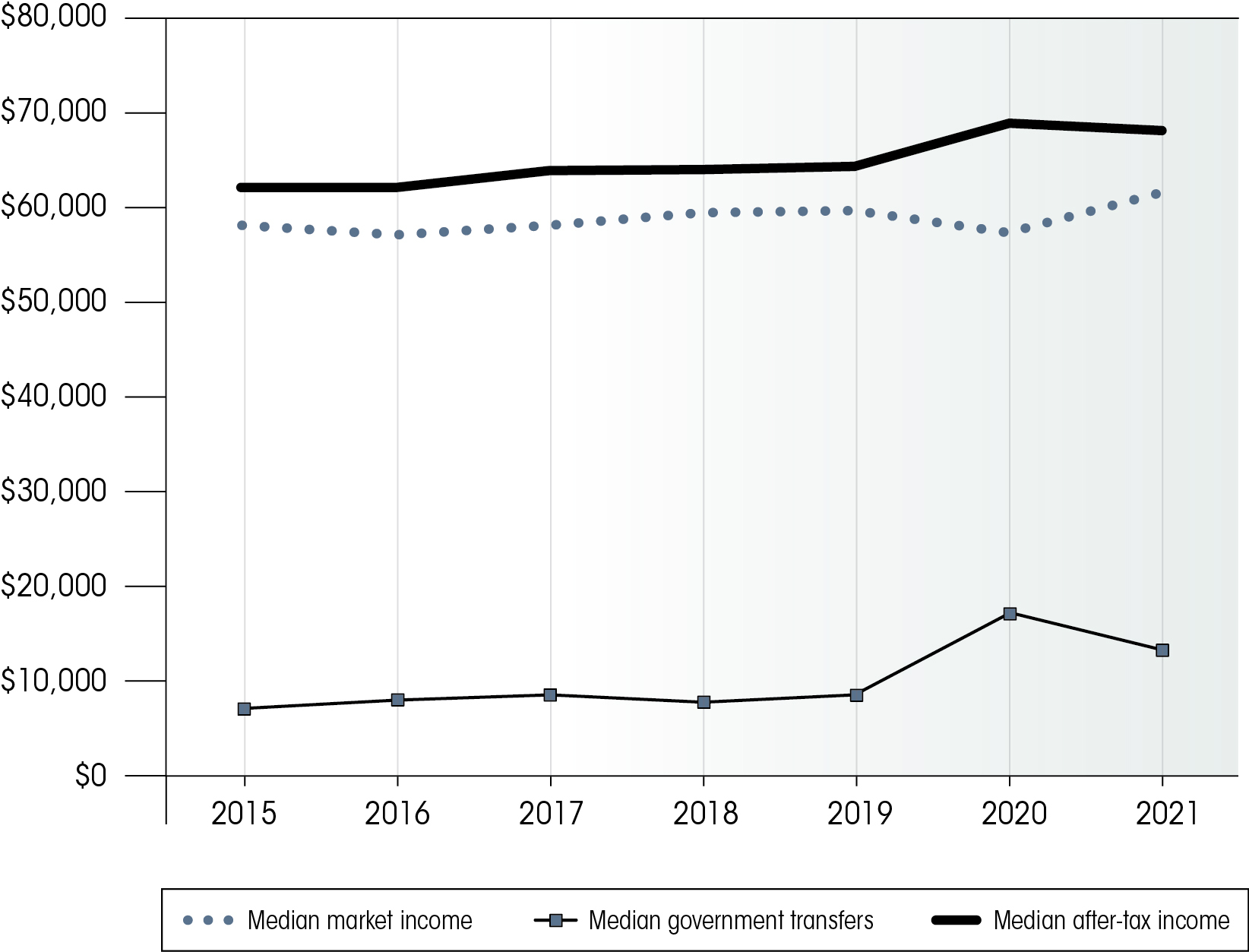

Poverty in Canada in 2020

As we cautioned in our last report, the large decrease in the overall poverty rate in 2020 was an anomaly. It was influenced by the unprecedented temporary increase in government transfers that year. In 2020, the median government transfers received by families and unattached individuals increased to $17,000 (Statistics Canada, 2023h). This is up significantly from $8,500 in 2019. The temporary income supports available during the pandemic more than offset income losses caused by COVID-19 emergency closures. As a result, median after-tax income of families and unattached individuals living in Canada increased from $64,500 in 2019 to $69,000 in 2020 (a 7% increase). Also, average disposable income per household in the bottom income quintile was estimated to have risen from $25,633 in 2019 to $33,024 in 2020, a 29% increase (Heisz & Gustajtis, 2023). This growth in income protected vulnerable individuals and families from falling into poverty. It also helped bring many people above the Official Poverty Line. It is important to keep this context in mind when considering 2020 data and making comparisons to 2021 data.

Official Poverty Rate for 2021 and provisional poverty rate for 2022

Despite maintaining the overall downward trend in poverty since 2015, the phasing out of the COVID-19 income supports alongside higher inflation and increasing cost of living mean that the large reduction in poverty in 2020 was not sustained in 2021. It is anticipated that the poverty rates for 2022 will increase even further.

In 2021, close to 2.8 million people living in Canada were below Canada's Official Poverty Line (Statistics Canada, 2023h). There were about 405,000 more people living in poverty in 2021 than in 2020. Between 2020 and 2021, Canada's overall poverty rate rose by 1.0 percentage point to 7.4%. This is equal to a 15.6% increase in the poverty rate between 2020 and 2021. Compared to 2015, there were close to 2.3 million fewer people living in poverty in Canada in 2021. This is a decrease of 49.0% in the overall poverty rate compared to 2015 (14.5%). Notably, the 2021 poverty rate is still below the pre-pandemic poverty rate (10.3% in 2019).

The year 2021 is the first time since the PRS was implemented that the poverty rate increased compared to the previous year. Modelling conducted by Statistics Canada suggests that the poverty rate will increase again in 2022. It is anticipated that it will increase to a level approaching the pre-pandemic rate of 10.3% in 2019 (Heisz & Gustajtis, 2023). The 2022 provisional poverty rate was estimated to be 9.8%. This would still represent a decrease of 32.4% compared to 2015 (14.5%). This provisional poverty rate is a prediction. It is based on annual data from the Consumer Price Index and average household disposable income (bottom quintile) for only part of 2022. Official poverty rates estimated using 2022 CIS data will be released in 2024.

Regional poverty trends for 2021

Between 2020 and 2021, the poverty rate increased across all provinces except for New Brunswick (-11.8%) and Prince Edward Island (-2.6%). On the other hand, the poverty rate increased the most for Alberta (+41.8%) and Saskatchewan (+35.8%). Compared to 2015, poverty has decreased the most for Quebec (-61.5%) and the least for Alberta (-17.0%). The table below summarizes the changes in poverty rates by province and territory between 2020 and 2021 and 2015 and 2021.

| Province/Territory | Poverty rate (%) 2015 | Poverty rate (%) 2020 | Poverty rate (%) 2021 | % change 2020 to 2021 | % change 2015 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada* | 14.5% | 6.4% | 7.4% | +15.6% | -49.0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 13.0% | 7.0% | 8.1% | +15.7% | -37.7% |

| Prince Edward Island | 15.7% | 7.6% | 7.4% | -2.6% | -52.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 16.8% | 7.7% | 8.6% | +11.7% | -48.8% |

| New Brunswick | 16.2% | 7.6% | 6.7% | -11.8% | -58.6% |

| Quebec | 13.5% | 4.8% | 5.2% | +8.3% | -61.5% |

| Ontario | 15.1% | 6.8% | 7.7% | +13.2% | -49.0% |

| Manitoba | 14.1% | 6.8% | 8.8% | +29.4% | -37.6% |

| Saskatchewan | 12.2% | 6.7% | 9.1% | +35.8% | -25.4% |

| Alberta | 9.4% | 5.5% | 7.8% | +41.8% | -17.0% |

| British Columbia | 18.6% | 7.6% | 8.8% | +15.8% | -52.7% |

| Northwest Territories** | No data | 10.2% | 15.0% | +47.0% | No data |

| Yukon** | No data | 8.8% | 7.7% | -12.5% | No data |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey.

- Notes:

- *The percentage of persons living in poverty in Canada does not include the territories.

- **The percentage of persons living in poverty was estimated using the Northern Market Basket Measure (MBM-N) for the Yukon and Northwest Territories. The estimates for the provinces and Canada use the MBM. No estimate of poverty is available for Nunavut at this time.

Poverty in the Yukon and Northwest Territories

For the first time, we are able to report on poverty estimates for the Yukon and Northwest Territories. In 2021, poverty rates in these jurisdictions were estimated to be higher than the national average (7.4%). The poverty rate was 7.7% for the Yukon and 15.0% for the Northwest Territories. In 2021, Indigenous people made up about 22% of the population in the Yukon and 50% in the Northwest Territories (Statistics Canada, 2023e). High poverty rates in these territories are consistent with what we have heard about continued discrimination through colonial practices and racist policies and programs that make it more likely for Indigenous people to live in poverty.

Poverty trends in Canada by demographic group

Between 2020 and 2021, poverty rates increased for most demographic groups. However, poverty decreased for non-senior singles under age 65 and some racialized groups including persons identified as South Asian, Filipino, Latin American, and Southeast Asian. Notably, the poverty rate for non-senior singles remains among the highest of any demographic group at 26.2% in 2021. On the other hand, poverty rates increased the most for:

- seniors (aged 65 and older) (+80.6%)

- those identified in the "other racialized persons" group (+80.0%)

- persons in male-led lone parent families (+61.1%)

- people identified as Black (+53.3%)

According to Statistics Canada, the increase in the poverty rate for seniors is largely attributable to the decrease in COVID-19 benefits after 2020 (Statistics Canada, 2023h).

Compared to 2015, poverty has decreased for all demographic groups for which 2015 data is available. Despite this, the decrease has not been equal across groups. Relative to 2015 levels, poverty rates have decreased the least for:

- seniors (-21.1%)

- non-senior singles (-32.6%)

- persons in male-led lone parent families (-38.6%)

Importantly, the poverty rate for seniors has been among the lowest of all demographics groups throughout 2015 to 2021. Over the same time, the poverty rate among persons living in male-led lone parent families has been much lower than the poverty rate among persons living in female-led lone parent families. The table below compares the change in poverty rates between 2020 and 2021 and between 2015 and 2021 for specific demographic groups. Table 10 in Appendix D shows the number of people in poverty by demographic group for 2015, 2020 and 2021.

| Group | Poverty rate (%) 2015 | Poverty rate (%) 2020 | Poverty rate (%) 2021 | % change 2020 to 2021 | % change 2015 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overallᶧ | 14.5% | 6.4% | 7.4% | +15.6% | -49.0% |

| Males | 14.1% | 6.3% | 7.0% | +11.1% | -50.4% |

| Females | 14.8% | 6.4% | 7.7% | +20.3% | -48.0% |

| Singles (under age 65) | 38.9% | 27.3% | 26.2% | -4.0% | -32.6% |

| Male singles (under age 65) | 36.5% | 25.4% | 24.2% | -4.7% | -33.7% |

| Female singles (under age 65) | 41.9% | 29.7% | 28.8% | -3.0% | -31.3% |

| Children aged 0 to 17 | 16.3% | 4.7% | 6.4% | +36.2% | -60.7% |

| Children aged 0 to 2 | 17.4% | 4.2% | 5.3% | +26.2% | -69.5% |

| Children aged 3 to 5 | 18.5% | 4.8% | 6.8% | +41.7% | -63.2% |

| Children aged 6 to 11 | 16.7% | 4.8% | 6.8% | +41.7% | -59.3% |

| Children aged 12 to 17 | 14.2% | 4.7% | 6.2% | +31.9% | -56.3% |

| Seniors (aged 65+) | 7.1% | 3.1% | 5.6% | +80.6% | -21.1% |

| Persons in lone parent families | 32.8% | 13.5% | 16.1% | +19.3% | -50.9% |

| Persons in male-led lone parent families | 18.9% | 7.2% | 11.6% | +61.1% | -38.6% |

| Persons in female-led lone parent families | 36.4% | 15.0% | 17.2% | +14.7% | -52.7% |

| Indigenous people living off reserve (aged 16+) | 26.2% | 11.8% | 13.9% | +17.8% | -46.9% |

| Indigenous people living on reserve | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected |

| 2SLGBTQ+ persons | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected |

| Persons with disabilities (aged 16+) | 20.6% | 8.5% | 10.6% | +24.7% | -48.5% |

| Immigrants (aged 16+)ᶧᶧ | 17.5% | 6.8% | 8.1% | +19.1% | -53.7% |

| Recent immigrants (10 years or less) aged 16+ | 28.3% | 8.6% | 10.3% | +19.8% | -63.6% |

| Very recent immigrants (5 years or less) aged 16+ | 34.9% | 11.2% | 12.0% | +7.1% | -65.6% |

| Racialized personsᶧᶧᶧ | not collected | 8.0% | 9.5% | +18.8% | not collected |

| South Asian | not collected | 7.5% | 7.0% | -6.7% | not collected |

| Chinese | not collected | 9.6% | 11.7% | +21.9% | not collected |

| Black | not collected | 7.5%* | 11.5% | +53.3% | not collected |

| Filipino | not collected | 3.6%* | 2.9%* | -19.4% | not collected |

| Arab | not collected | 10.0%* | 12.8%* | +28.0% | not collected |

| Latin American | not collected | 8.7%* | 6.8%* | -21.8% | not collected |

| Southeast Asian | not collected | 10.3%* | 9.1%* | -11.7% | not collected |

| Other racialized persons** | not collected | 8.0% | 14.4% | +80.0% | not collected |

| Persons living in institutions | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected |

| Persons who were formerly incarcerated | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected | not collected |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 11-10-0090-01 Poverty and low-income statistics by disability status; Table 11-10-0093-01 Poverty and low-income statistics by selected demographic characteristics; Table 11-10-0136-01 Low income statistics by economic family type.

- Notes:

- ᶧThe estimated poverty rates in this table only include data from Canada's provinces.

- ᶧᶧReferred to by Statistics Canada as people who are, or have been, landed immigrants in Canada. Canadian citizens by birth and non-permanent residents (persons from another country who live in Canada and have a work or study permit, or are claiming refugee status, as well as family members living here with them) are not considered landed immigrants.

- ᶧᶧᶧReferred to by Statistics Canada as persons designated as visible minorities.

- *Statistics Canada indicates that these data should be used with caution.

- **Other racialized persons includes racialized groups not included elsewhere and persons who identified as more than one racialized group.

2021 poverty rate among specific demographic groups and groups made most marginal

Data from the 2021 CIS show continued high rates of poverty among groups made most marginal. In particular, single or unattached persons (all ages) had a poverty rate of 21.9% compared to 4.4% for persons in families. The poverty rate among persons in lone-parent households was 16.1%. Persons living in female-led lone parent households were more likely to live in poverty (17.2%) than those in male-led lone parent households (11.6%). Among people aged 16 and older, the poverty rate was about twice as high for Indigenous people (13.9%) compared to non-Indigenous people (7.4%). The poverty rate among racialized groups (9.5%) was higher than that for non-racialized groups (6.5%). Of racialized groups, poverty rates were highest for persons identified as Arab (12.8%), Chinese (11.7%), and Black (11.5%).

Factors driving the increasing poverty rate

As noted above, the poverty rate in Canada increased from 6.4% in 2020 to 7.4% in 2021. According to analyses from Statistics Canada, the poverty rate is expected to continue increasing in 2022. It is expected to approach a level near the pre-pandemic rate of 10.3% in 2019. Incomes failing to keep pace with the rising cost of living is likely to drive this expected upward trend in the poverty rate.

Incomes in 2021

The median market income of families and unattached persons rose from $57,500 in 2020 to $61,700 in 2021. This represented an increase of 7.3% in 2021, which erased the decrease observed between 2019 and 2020. On the other hand, the total COVID-19 benefits received by people living in Canada decreased by 68% in 2021. This decreased the median government transfer for families and unattached individuals from a historical high of $17,000 in 2020 to $13,300 in 2021. The 2021 median transfer was still higher than in 2019 ($8,500). This reflected the continued presence of the Canada Recovery Benefit, Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, and Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit. These benefits continued to give support to many Canadians into the 2021 calendar year.

Text description of Graph 2

| Year | Median market income | Median government transfers | Median after-tax income |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | $58,200 | $7,100 | $62,400 |

| 2016 | $57,300 | $8,000 | $62,400 |

| 2017 | $58,200 | $8,300 | $63,900 |

| 2018 | $59,500 | $7,700 | $64,100 |

| 2019 | $59,600 | $8,500 | $64,500 |

| 2020 | $57,500 | $17,000 | $69,000 |

| 2021 | $61,700 | $13,300 | $68,400 |

- Source: Canadian Income Survey, Statistics Canada, Table 11-10-0190-01 Market income, government transfers, total income, income tax and after-tax income by economic family type.

- Notes: Market income is the sum of earnings (from employment and self-employment), net investment income, private retirement income and items under other income. After-tax income refers to income from all sources including government transfers minus income tax.

Median Hourly Wage – An indicator of poverty tracked under the PRS

This indicator measures the hourly wage at which half of the population has a higher wage and half has a lower wage. The median hourly wage (in 2022 constant dollars) decreased from $28.70 in 2020 to $27.76 in 2021 and to $27.00 in 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2023a). The pandemic caused significant employment losses in lower-pay sectors, such as accommodation services and retail. This significantly changed the distribution of wages in 2020 and to some extent, in 2021. Changes in the median hourly wage between 2020 and 2022 need to be considered in this context.

Minimum wage and gap to Official Poverty Line

Being employed does not always mean that people make enough money to support themselves. Even working full-time, those making minimum wage may live below the poverty line, without the addition of government benefits. This brings into question the adequacy of minimum wage rates across Canada. It also emphasizes how important accessible benefits are for people living below the poverty line. The table below shows examples of estimated annualized minimum wage incomes (after deducting income tax and EI and CPP contributions) for a person working full-time and earning the federal minimum wage as well as the highest (British Columbia) and lowest (Saskatchewan) provincial minimum wages in 2021. In this example, minimum wage was inadequate for keeping a full-time worker earning minimum wage above the 2021 Official Poverty Line for their region.

The example calculation used minimum wage rates that were in effect at the end of 2021 for each province. However, the minimum wage rates changed throughout the year. For example, the federal minimum wage ($15.00) came into effect on December 29, 2021. The minimum wage for Saskatchewan increased from $11.45 to $11.81 on October 1, 2021. The minimum wage for British Columbia increased from $14.60 to $15.20 on June 1, 2021. Thus, in our example, even if a person had earned the higher end-of-year minimum wage in their province for the entire year, it would have still been inadequate to keep them out of poverty.

| MBM region | 2021 MBM threshold for 1 person (Official Poverty Line) | Minimum wage* | Estimated annualized minimum wage income after non-discretionary deductions for 2021 (full-time)** | 2021 gap between estimated annualized minimum wage income and MBM threshold for 1 person (Official Poverty Line) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottawa-Gatineau (Ontario-part) | $25,178 | $15.00 | $22,765 | -$2,413 |

| Regina, Saskatchewan | $23,741 | $11.81 | $18,803 | -$4,938 |

| Vancouver, British Columbia | $25,942 | $15.20 | $23,344 | -$2,598 |

- Notes:

- *The MBM threshold for 1 person for the Ottawa-Gatineau (Ontario-part) region was used as a point of comparison for the federal minimum wage. The federal minimum wage applies only to workers in federally regulated sectors.

- **Estimated annualized minimum wage incomes (full-time) were calculated by multiplying each jurisdiction's minimum hourly wage by 35 hours per week and by 52 weeks per year and subtracting estimated income taxes and social security contributions (EI and CPP). This basic calculation shows example incomes for full-time workers earning minimum wage. It does not factor in tax credits, federal, provincial, or territorial supports, or other forms of income.

Some groups who have a higher risk of experiencing poverty are more likely to work in minimum wage jobs. In 2018, of those working in minimum wage jobs:

- 58.8% were women

- 52.3% were between the ages of 15 to 24

- 30.7% were permanent residents (referred to as landed immigrants by Statistics Canada in the Labour Force Survey)

- 25.7% were unattached (single) persons and lone parents (Dionne-Simard & Miller, 2019)

Deep income poverty – An indicator of poverty tracked under the PRS

Deep income poverty measures the percentage of individuals whose family disposable income is less than 75% of the applicable poverty line for their family size. In Canada, the percentage of persons living in deep income poverty increased from 3.0% in 2020 to 3.6% in 2021.

Social assistance and gap to Official Poverty Line

Social assistance provides support of last resort to persons lacking the means to pay for basic or essential needs. In this section, welfare income refers to income from all government transfers, including basic provincial and territorial social assistance, refundable tax credits, child benefits, and any other specific social assistance benefits, as defined by the Maytree Foundation.

According to analyses conducted by the Maytree Foundation, 80% of household types eligible for maximum social assistance benefits across the provinces would have had total welfare incomes below the deep income poverty threshold in 2021 (Laidley & Tabbara, 2022). This means that a large proportion of households that rely only on social assistance and other government transfers lived in deep poverty. The table below shows the highest and lowest total annual welfare incomes relative to the applicable Official Poverty Line for different household types.

| Example household type (Scenario)* | Jurisdiction | Applicable Official Poverty Line (MBM threshold)** | Total annual welfare income | Gap to MBM threshold | % of MBM threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single person (lowest) | Moncton, NB | $22,404 | $7,499 | -$14,905 | 33% |

| Single person (highest) | Montreal, QC | $21,529 | $12,968 | -$8,561 | 60% |

| Single person with a disability (lowest) | Calgary, AB (BFE)ᶧᶧ | $25,910 | $11,195 | -$14,715 | 43% |

| Single person with a disability (highest) | Calgary, AB (AISH)ᶧᶧ | $25,910 | $21,164 | -$4,746 | 82% |

| Single parent, 1 child (lowest) | Halifax, NS | $34,175 | $21,134 | -$13,041 | 62% |

| Single parent, 1 child (highest)ᶧ | Montreal, QC | $30,447 | $24,532 | -$5,915 | 81% |

| Single parent, 1 child (highest)ᶧ | Charlottetown, PEI | $33,050 | $26,639 | -$6,411 | 81% |

| Couple, 2 children (lowest) | Moncton, NB | $44,808 | $27,177 | -$17,631 | 61% |

| Couple, 2 children (highest) | Montreal, QC | $43,058 | $39,659 | -$3,399 | 92% |

- Source: 2021 Welfare in Canada, Maytree Foundation.

- Notes:

- *For the analysis, the head of all households were assumed to be fully "employable," except for the single person with a disability (as reflected in program eligibility definitions). It was also assumed that the households had no earnings, so they were eligible to receive the maximum rate of social assistance.

- **Poverty thresholds for 2021 were estimated by increasing 2020 thresholds in line with the CPI for each applicable city. Thus, MBM poverty thresholds may not reflect 2021 official thresholds.

- ᶧSingle parent, 1-child households in Montreal and Charlottetown were both designated as the highest welfare incomes. Each was 81% of their corresponding MBM threshold.

- ᶧᶧAISH refers to Alberta's Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped program. BFE refers to Alberta's Barriers to Full Employment program.

Analyses by the Maytree Foundation also show that phasing out temporary COVID-19 supports worsened the depth of poverty experienced by households receiving social assistance. Overall, 81% of the household types receiving social assistance experienced a net loss in pandemic-related supports between 2020 and 2021 (Laidley & Tabbara, 2022). The amount lost depended on the household type and jurisdiction. Losses ranged from $33 for a single parent, 1-child household in Prince Edward Island to $5,438 for a couple with 2 children in British Columbia.

Adding to the phaseout of COVID-19 supports, most jurisdictions did not substantially increase social assistance rates in 2021. Amid high inflation, many households that rely only on social assistance and other government transfers were worse off in 2021 than in 2020. The 2021 Welfare in Canada report showed that of the household types examined in the provinces and territories:

- 57% saw decreases in total welfare incomes that were worsened by inflation

- 32% saw total welfare incomes stay the same or increase by rates that were negated by the rate of inflation

- 11% saw their total welfare incomes increase (in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island only)

Cost of living

In April 2022, about 75% of people living in Canada reported that rising costs were affecting their ability to meet day-to-day expenses (Statistics Canada, 2022c). Urban residents reported being most affected by rising food prices, but rural residents reported being most affected by transportation. Of respondents, 27% reported having to borrow money from friends or relatives, take on additional debt or use credit to meet day-to-day expenses in the 6 months before the survey. Of the respondents, some groups were more likely to report needing to borrow money to meet day-to-day expenses. These included:

- those in the bottom 2 household income quintiles

- individuals aged 15 to 39

- households with at least 1 child under 18

- persons with a disability

- persons belonging to racialized groups

By December 2022, 26% of households said they would be unable to cover an unexpected expense of $500 (Statistics Canada, 2023c).

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) tracks the change in prices experienced by consumers in Canada by comparing the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services over time. The CPI is used to estimate inflation and increases in the cost of living. In 2021, the CPI increased by 3.4% on an annual average basis compared to 0.7% in 2020 (Statistics Canada, 2022a). In 2022, the CPI rose 6.8% on an annual average basis, doubling the rate from 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2023b). The recent increases in the cost of living represent one of the most important socioeconomic challenges faced by people living in Canada following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is expected that this will put upward pressure on poverty rates in 2022, especially for groups made most marginal.

Impact of CPI on MBM thresholds

The MBM establishes poverty thresholds for different regions in Canada's provinces. It adjusts those thresholds according to changes in the cost of living. Since 2015 and before the pandemic, MBM thresholds increased on an annual basis between 0.9 to 2.3% on average. However, MBM thresholds increased on average by 3.4% in 2021 and 8.1% in 2022. This reflects the high inflation rates experienced throughout 2022, with large increases in the shelter, transportation and food components of the MBM. The table below shows the trend in the annual growth rate of the average MBM threshold.

| Year | Average MBM threshold (MBM reference family of 4 persons) | Growth rate in average MBM threshold from previous year |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | $41,045 | not applicable |

| 2016 | $41,581 | +1.3% |

| 2017 | $41,963 | +0.9% |

| 2018 | $42,790 | +2.0% |

| 2019 | $43,756 | +2.3% |

| 2020 | $44,141 | +0.9% |

| 2021 | $45,655 | +3.4% |

| 2022 | $49,356 | +8.1% |

- Source: Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0066-01 Market Basket Measure (MBM) thresholds for the reference family by Market Basket Measure region, component and base year. Based on MBM with 2018 base.

Housing

Core housing need, Census 2021

Core housing need is one of the indicators of poverty tracked under the PRS. Households are identified as being in core housing need when they live in housing that is unaffordable, in major need of repairs, or unsuitable for the size and composition of the household and are not able to afford alternative housing in their community. This indicator is officially reported using Census data. Thus, this is the first year since we convened as a council that we can report an update. Importantly, the rate of core housing need for 2021 uses 2020 household incomes. As noted, temporary COVID-19 supports increased median incomes in 2020 which lifted many households above housing affordability thresholds. COVID-19 income supports have since ended. This will likely further strain households already struggling to make ends meet.

According to the Census, core housing need decreased from 12.7% in 2016 to 10.1% in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2023e). All provinces and territories experienced decreases in the proportion of households in core housing need between 2016 and 2021. Nunavut experienced the highest absolute decrease, falling from 36.5% in 2016 to 32.9% in 2021. However, Nunavut's core housing need rate is still the highest among all provinces and territories in Canada. It is about 3 times the national rate. Core housing need was higher for renters (20.0%) than homeowners (5.3%) (Statistics Canada, 2022f). Renters were more than twice as likely to be in unaffordable housingFootnote 1 (33.2%) compared to homeowners (14.8%). Of note, the number of people living in Canada who are renting their home is increasing. Homeownership has become more difficult with the cost of buying a home outpacing household income growth (Statistics Canada, 2022d; Statistics Canada, 2022f).

Children

603,040 children (8.8%) were in core housing need in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2022f). Core housing need was higher for children in lone-parent households (24.7%) compared to those in a couple family (5.4%).

People living alone

In 2021, persons in a couple family were the least likely to be in core housing need (Statistics Canada, 2022f). MillennialsFootnote 2 living alone were more likely to have core housing need (15.3%) than those that lived with a roommate (7.4%) or who lived in a couple (4.5%). Seniors living alone were more likely to live in unaffordable housing when renting (49.0%) compared to those who owned a home (18.8%) (Statistics Canada, 2022d).

People who use social housing

In 2021, about 227,100 households were waiting for social and affordable housing compared with 262,000 in 2018 (Statistics Canada, 2022d). Of those waitlisted, 148,200 (65%) reported waiting 2 years or longer. Further, among those waitlisted, about 66% of lone-parent households, 33% of young adult-led households, and 70% of senior-led households were waiting 2 years or longer.

Shelter costs and housing affordability – 2022

In 2022, shelter costs rose by 6.9% on an annual average basis (Statistics Canada, 2023b). Similarly, rent prices increased by 4.6% in 2022 compared to 1.6% in 2021. Also, in March 2022, the Bank of Canada began increasing interest rates, directly impacting the cost of owning a home. The Mortgage Interest Cost Index grew by 2.6% in 2022 after decreasing by 7.7% between 2020 and 2021. This has the biggest impact on:

- those with a variable-rate mortgage

- those renewing their mortgage

- prospective homebuyers such as young people (Statistics Canada, 2022f)

By December 2022, 58% of those aged 15 to 24 and 56% of those aged 25 to 34 reported being very concerned about their ability to afford housing or rent (Statistics Canada, 2023c). Moreover, members of racialized groups were also more likely to report concern about the cost of housing. About 74% of persons identifying as Black and 65% of persons identifying as South Asian reported being very concerned about the cost of housing. This was compared to 38% of non-Indigenous, non-racialized respondents.

Houselessness in Canada

A point in time (PiT) count conducted between 2020 and 2022 estimated that over 32,000 people in 59 communities across Canada were experiencing absolute houselessness in shelters, transitional housing, and unsheltered locations (Infrastructure Canada, 2023). Among the 55 communities included in the PiT count in 2018, the number of persons experiencing houselessness increased by 12%, with double the number of people living in an unsheltered location.

A PiT count is a one-day snapshot of houselessness in shelters and on the streets in participating communities. A PiT count estimates how many people are experiencing houselessness in emergency shelters, in transitional housing and in unsheltered locations on the day of the count. It does not account for those experiencing hidden houselessness or those experiencing houselessness in communities that did not participate in the PiT. It is therefore likely to underestimate houselessness in Canada.

Of those surveyed between 2020 and 2022, 46% experienced houselessness for the first time before the age of 25. About 71% experienced chronic houselessness compared to 60% in 2018. Around 35% of respondents identified as Indigenous, with most identifying as First Nations. The majority of 2SLGBTQ+ respondents were among youth respondents aged 13 to 24 (24%), followed by adults aged 25 to 49 (12%), older adults aged 50 to 64 (6%), and seniors aged 65 and up (5%).

National Housing Strategy and affordable housing

On top of rising shelter costs, Canada is losing affordable housing faster and in excess of what the National Housing Strategy (NHS) has committed to produce (National Housing Council, 2023). The NHS was designed with a target to produce 150,000+ units of housing that rent for $750/month or less. But estimates suggest that more than 550,000 units renting at this rate have been lost between 2011 and 2021. Further, the 30% shelter cost to income threshold used to define affordable housing may be too high for those experiencing deep poverty. This may prevent housing that is designated as affordable from benefiting those who need it the most.

As demonstrated in the example in Table 3, full-time workers earning minimum wage in Ottawa, Regina, and Vancouver would have had incomes below the 2021 Official Poverty Line. In 2021, the monthly average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in the lowest rental rate category was $1,280 for Ottawa, $953 for Regina, and $1,434 for Vancouver (Statistics Canada, 2023d). For rental costs to be at most 30% of gross income (based on the definition of affordable housing), a person's gross income would have to be $51,200 in Ottawa, $38,120 in Regina, and $57,360 in Vancouver. The incomes shown in Table 3 suggest that full-time minimum wage earners in each of these cities would have to pay much more than 30% of their gross earnings to afford the average rent of a one-bedroom apartment.

Spotlight on the National Housing Council's 2023 Report

In April 2023, The National Housing Council released Renewing Canada's National Housing Strategy: A Report to the Minister of Housing and Diversity and Inclusion on the National Housing Strategy (National Housing Council, 2023). The Report came to the following conclusions:

- many people in core housing need or experiencing houselessness are not reached by the affordable housing being built or the subsidies from the Canada Housing Benefit

- Canada is losing affordable housing faster and in greater quantities than the National Housing Strategy is producing it

- the design of programs under the National Housing Strategy and the definitions of affordable housing exclude specific groups it intends to prioritize, including but not limited to 2SLGBTQ+, Indigenous people, newcomers, people experiencing houselessness, people with disabilities, racialized communities, seniors and women

- while the National Housing Strategy has produced over 115 000 new units of housing as of September 2022, the vast majority of the housing produced, and the subsidies delivered by the Canada Housing Benefit, are not affordable to or reaching those in core housing need or experiencing homelessness

The National Advisory Council on Poverty agrees with and echoes these concerns with the National Housing Council. We feel that the current housing crisis will not be solved through the National Housing Strategy, nor will it help those who are made most vulnerable.

Grocery costs and food insecurity – 2021

Between 2020 and 2021, the cost of groceries increased by 2.2%. This is compared to an increase of 2.4% between 2019 and 2020 (Statistics Canada, 2022a).

Food insecurity and poverty

Based on data from the 2020 CIS, of the total population facing severe food insecurity, 22% were below the poverty line (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2023). Nearly half (45.4%) of those facing severe food insecurity were in economic families with incomes greater than 50% above the poverty line. For persons experiencing severe food insecurity, government transfers were the main source of family income (53.5%), followed by wages and salaries (43.2%).

Research from the interdisciplinary research program PROOF indicates that food insecurity decreases with policies that increase the incomes of very low-income households (Tarasuk & Li, 2022). In other words, poverty reduction policies that help supplement incomes should also help reduce food insecurity across Canada.

In 2021, about 4.8 million people who live in Canada (12.9%) lived in households that experienced food insecurity (defined as moderate or severe) compared to 4.1 million (11.2%) in 2020 (Statistics Canada, 2023h). Groups made most marginal were more likely to experience food insecurity. For example, in 2021, persons living in female-led lone parent households had the highest rates of food insecurity (34.1%). Racialized groups were also more likely to experience food insecurity (16.8%) compared to non-racialized groups (11.3%). Of racialized groups, persons identified as Black experienced the largest absolute increase in food insecurity between 2020 (17.2%) and 2021 (27.2%). Also, in 2021, 24.1% of Indigenous people aged 16 years or older living off reserve experienced food insecurity. Food insecurity rates were particularly high among First Nations people aged 16 years or older living off reserve (29.4%). For comparison, 11.8% of non-Indigenous people aged 16 years or older experienced food insecurity in the same year. The table below shows the change in food insecurity rates between 2020 and 2021 for demographic groups with data available.

| Demographic group | 2020 | 2021 | % change in rate: 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 4,143,000 (11.2%) | 4,821,000 (12.9%) | +15.2% |

| Children (under age 18 years) | 962,000 (13.6%) | 1,223,000 (16.8%) | +23.5% |

| Seniors (aged 65 years and over) | 377,000 (5.7%) | 433,000 (6.3%) | +10.5% |

| Persons in lone-parent households | 467,000 (27.3%) | 537,000 (30.0%) | +9.9% |