2025 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

Official title: We can do better: it is not a safety net if the holes are this big - the 2025 report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of tables

- List of graphics

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Message from the Chairperson

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Progress on meeting Canada’s poverty reduction targets

- Chapter 2: Why it matters

- Chapter 3: Affordability and income security

- Chapter 4: Access to benefits and services

- Chapter 5: Stability through investments in housing

- Chapter 6: Supporting communities

- Chapter 7: Life events, transitions and mental health

- Chapter 8: Active labour force participation

- Conclusion

- References

- Annex A – Organizations that participated in the ongoing dialogues

- Annex B – Glossary of terms

- Annex C – Recommendations from previous reports of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

Alternate formats

We can do better: it is not a safety net if the holes are this big. The 2025 Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty [PDF - 3.50 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQIA+

- Individuals who identify as Two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersexed and/or asexual. The plus is inclusive of people who identify as part of the sexual and gender diverse community, and who use additional terminologies.

- BDM

- Benefits Delivery Modernization programme

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CICP

- Charity Insights Canada Project

- CIS

- Canadian Income Survey

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplement

- GST/HST

- Goods and Services Tax/Harmonized Sales Tax

- IYS

- Integrated Youth Services

- MBM

- Market Basket Measure

- MBM-N

- Northern Market Basket Measure

- NHS

- National Housing Strategy

- NHSA

- National Housing Strategy Act

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- QPP

- Quebec Pension Plan

- SUAP

- Substance Use and Addictions Program

- YESS

- Youth Employment and Skills Strategy

List of tables

List of graphics

List of figures

Acknowledgements

The current members of the National Advisory Council on Poverty are proud to present this year’s report.

- Scott MacAfee, Chairperson

- Marie Christian, Member with particular responsibilities for children’s issues

- Hannah Brais

- Avril Colenutt

- John Cox

- Kristen Desjarlais-deKlerk

- Lindsay (Swooping Hawk) Kretschmer

- Nathalie Lachance

- Noah Lubendo

- Kwame McKenzie

The Council would like to thank former members of the Council whose work has been foundational in promoting poverty reduction in Canada.

The Council would also like to express its gratitude to the government officials who assisted us in our work throughout this year and in previous years. These include the members of the Council’s Secretariat at Employment and Social Development Canada and public servants from Statistics Canada and other key government departments. Their ongoing support makes it possible for the Council to fulfill its mandate.

Dedication

The National Advisory Council on Poverty dedicates this 2025 progress report to all the individuals who selflessly shared their stories of success and struggle. Your invaluable insights are the foundation on which we build better systems, enhance supports and improve the lives of others experiencing poverty or at risk of experiencing it. You’re the foundation for this report.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the lead organizations that supported the Council during our visits to Campbellton (NB), Fredericton (NB), Scarborough (ON) and Winnipeg (MB), and our virtual meetings with groups in Lévis (QC) and Québec (QC). These organizations were instrumental in connecting us with individuals who experience poverty, enabling us to gain a better understanding of how poverty is experienced in their regions. Thank you to:

- ACSA Community Services

- Centraide Québec et Chaudière-Appalaches

- Comité consultatif de lutte contre la pauvreté et l'exclusion sociale

- Restigouche Regional Service Commission

- United Way Winnipeg

Message from the Chairperson

I’m pleased to present, on behalf of the National Advisory Council on Poverty, our 2025 report on the progress of Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy.

In early 2025, we ventured out to meet with people in Canadian regions with some of the highest poverty rates to get a glimpse of their realities and assess the adequacy of the supports they receive or should receive. We met with individuals experiencing poverty and with community organizations that offer them supports in Winnipeg, Scarborough (Greater Toronto Area), Québec, Lévis, Fredericton and Campbellton. We also spoke to several advocates, service providers, and experts who work to identify ways to reduce, and ultimately end, poverty.

We were particularly interested in hearing their views on whom people turn to when they need support, how they access services, and if the existing benefits and programs meet their needs.

Some of the most predominant themes emerging from these conversations included:

- the ongoing struggle with inadequate income and insufficient financial support, especially in the face of a steadily rising cost of living

- the challenges faced by individuals to access, or even be aware of, benefits and supports to which they’re entitled

- the chronic lack of safe, suitable and affordable housing

- the burden placed on the underfunded and overextended non-profit sector to provide essential care and support for people who depend on it to survive

- the various circumstances, including life events and transitions, that have kept people in poverty, including struggles with mental health, substance use and addictions

- the barriers to active labour force participation

This year’s conversations about poverty showed us that any effective response would have to be twofold. First, we must support those currently experiencing poverty—in all its forms. At the same time, we must support those most at risk of experiencing it, intervening before they fall below the poverty line. Tackling both immediate needs and the broader systemic conditions will be challenging, as it will require a divided yet coordinated focus.

The multifaceted nature of poverty emerged as a recurring theme throughout our conversations. We heard about monetary poverty and the pain of social and economic exclusion. Stories highlighted how the past shapes the present, how survival and stability require 2 different mindsets, and how addressing poverty isn’t about fixing 1 thing; it likely requires transforming everything.

That said, I’m heartened to report that countless individuals and organizations across Canada are deeply dedicated to improving the daily lives of others. They hold their communities close to their heart and care for those in need of support. As we move forward, we must find better ways to support them, and to look out for one another.

This report summarizes the conversations we had, the challenges we uncovered, and the courageous choices we must make—as a country, collectively and individually—to end poverty.

Thank you,

Scott MacAfee

Chairperson, National Advisory Council on Poverty

Executive summary

Our social safety net wasn’t designed to handle the current challenges and socio-economic pressures. We need to respond quickly to protect Canadians experiencing poverty and protect others from falling into it.

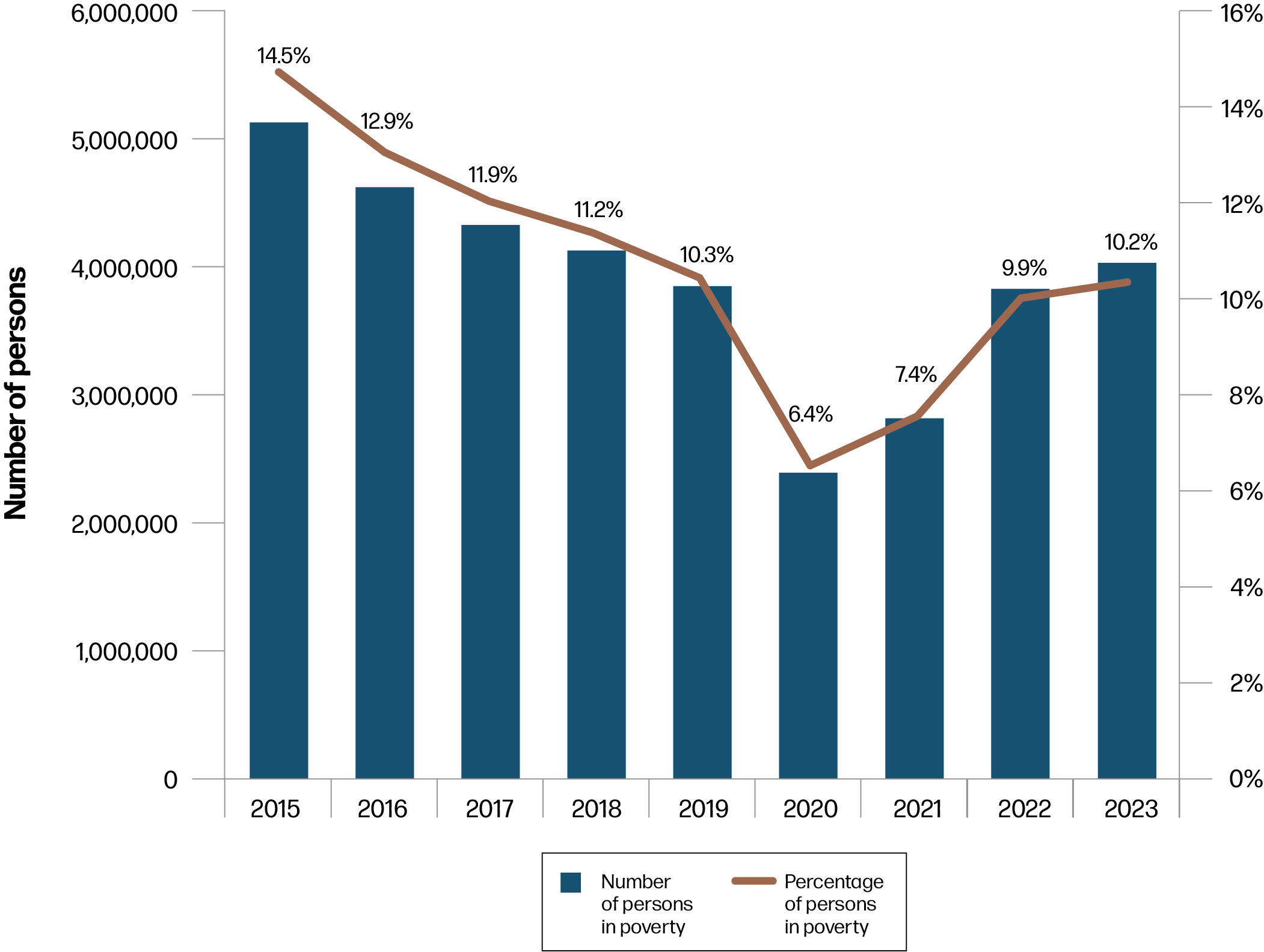

Poverty is going up in Canada and has been since 2021. In 2023, 10.2% of individuals in Canada—about 4 million people—were living in poverty. While poverty grew more slowly between 2022 and 2023, it has increased for 3 years in a row. This is putting Canada at risk of missing its target to reduce poverty by half by 2030.

This year, the National Advisory Council on Poverty held engagement sessions in communities with some of the highest poverty rates to understand how support systems are working for individuals. People shared that many services are often confusing, hard to access and dehumanizing, and fail to meet their needs. Others indicated not knowing who or where to turn to. The Council explored how current systems support poverty reduction and promote dignity, inclusion and resilience. We heard about the importance of both formal supports, like tax credits and benefits, and informal ones, such as help from family or trusted community members.

As the cost of living continues to rise and incomes fail to keep pace, more people are turning to support services, many for the first time. In 2023, Canada invested over $286.4 billion in social protection programs as part of the broader social safety net (Statistics Canada, 2024e). Despite these significant investments, some individuals are still not receiving the benefits, supports and services they need to survive. To ensure no one is left behind, the Government must take stronger action to identify and address these gaps.

Why addressing poverty matters

Poverty is not only about money. Oppression, intergenerational trauma, racism, discrimination, lack of opportunity and other systemic forces shape the experience of poverty.

Poverty isn’t an individual’s failure; it’s a systemic issue rooted in policies and structures that benefit some while disadvantaging others. Throughout this year’s engagement sessions, we heard that poverty is rising due to the increasing cost of living and stagnant wages. Many people described feeling stuck in a cycle that demands time, energy and resilience, with little chance to get ahead. People described poverty as dehumanizing. They feel stigmatized and infantilized by the very systems meant to support them.

While poverty can affect anyone, it often results from discrimination. Black and racialized individuals, Indigenous people, newcomers, 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals, people with disabilities, and seniors all shared how systemic barriers in housing, employment, education and access to services make them more vulnerable.

Poverty divides us and weakens the fabric of our communities. Addressing it at its roots is essential to building a more just and inclusive society.

Affordability and income security

Income adequacy is one of the most critical issues in addressing poverty. Poverty is complex and requires a range of solutions. But if people don’t have a sufficient income, then other essential supports can’t be effectively implemented. The federal government has introduced various initiatives and made numerous commitments since 2015 aimed at reducing poverty, yet challenges persist.

Although inflation has slowed since 2023, steep increases in essential costs—especially in food and shelter—continue to strain household budgets. For many, incomes and financial supports remain inadequate. Neither wages nor government benefits have kept pace with inflation. Even when people work full time, their wages are often too low to lift them out of poverty. While social assistance is a key pillar of Canada’s income security system, every household relying solely on it, even with other related government benefits, remains in poverty.

Access to benefits and services

Canada’s social safety net is complex and difficult to navigate, with supports and services offered by various levels of government, non-profits, and informal networks. Many people face significant barriers when trying to access these supports. Complex programs, unclear application processes, inconsistent rules and rigid eligibility criteria only add to the difficulty. Community organizations and service providers also face resource constraints, making it harder to guide individuals, particularly those with complex needs, through the system. Barriers such as the requirement to file taxes as an eligibility criterion, accessibility challenges and digital exclusion—particularly among groups made most marginal, including 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals, Black and racialized people, First Nations, Inuit and Métis people, persons with disabilities, youth, and seniors—further limit access to essential supports and deepen existing inequity. Support providers should coordinate, co-locate and simplify processes to improve access and outcomes.

Stability through investments in housing

The National Housing Strategy outlines Canada’s housing policy and acknowledges adequate housing as a fundamental human right. Despite various efforts from the federal government, this year people indicated that securing and keeping safe affordable housing was one of their biggest challenges. This was true for those experiencing poverty and was raised as a concern for those living above the poverty line.

We heard from some that the cost of a single room often exceeds social assistance, leaving people with limited choices. This forces some to rent inadequate housing, turn to shelters or live rough, and rely on charity to meet their other needs. Even those who secure housing struggle. High rent leaves little money for essentials, making financial stability fragile.

Homeowners are also feeling the strain, largely due to rising interest rates, with mortgage and utility costs eating into funds meant for necessities like food and transportation. Many social housing residents told us their homes felt unsafe, poorly maintained and infested with pests, making daily life difficult. Homelessness continues to rise, and the underfunded shelter system is unable to support the growing demand. Certain groups are particularly vulnerable. We heard about racism and discrimination from landlords faced by newcomers, refugees and asylum seekers. Additionally, homelessness disproportionately affects Indigenous people and Black and racialized communities.

Supporting communities

Some members of our communities have, and will always have, more complex needs and face challenges that financial support alone can’t resolve. Addressing these requires a broader range of services, often delivered by non-profits through targeted programs and wraparound supports. However, we heard that accessing these services can be incredibly difficult. People often struggle to find the right help, navigate complex systems and receive timely support. Stigma, especially around harm reduction, mental health and homelessness, makes accessing help during crises very hard.

The non-profit sector plays a vital role in supporting people experiencing poverty. It employs compassionate staff and volunteers who are dedicated to making a difference. However, organizations face immense pressure. Growing demand and increasingly complex needs stretch resources thin. Meanwhile, decreased government funding, rising costs and the challenge of securing core funding make sustainability difficult. Despite their expertise, many workers in the sector receive a pay below a living wage, which doesn’t reflect their skills and contributions, and forces some to rely on the very services they provide to meet their basic needs.

Life events, transitions and mental health

Major life changes, like aging out of care, becoming a parent, losing a job or moving to a new country, can seriously affect a person’s well-being and finances, especially for those experiencing poverty. These transitions often require extra support, both financial and non-financial. Youth leaving care, for example, face high risks of homelessness due to sudden loss of support. Additionally, the link between poverty, mental health challenges and substance use can make it harder for people experiencing this combination of struggles to find stability. Services to help with these issues are often hard to access, underfunded and overwhelmed. Canada spends less on mental health than many other countries, and many people don’t get the care they need. Without better, more coordinated support, people in crisis often end up in hospitals, shelters or the justice system.

Active labour force participation

Canada’s labour force has grown significantly, yet many groups, especially those made most marginal, continue to face systemic barriers to employment. A range of structural factors such as unequal access to early work opportunities, limited professional networks, skill mismatches, and credentialism drive these challenges. Together, these barriers can make it harder for even some well-equipped individuals to secure stable and meaningful employment and contribute to Canada’s labour force.

To build a more inclusive labour market, wraparound supports like language training, mental health care, child care and culturally responsive employment services are essential.

Recommendations

The poverty rate in Canada continues to rise despite significant government investments, leaving many unable to meet their basic needs. The Council emphasizes the urgent need for a guaranteed income floor to ensure everyone can live with dignity, regardless of their income source. Many people perceive current social assistance systems as overly complex and ineffective. Some have recommended implementing a basic income, which they consider to be a more dignified and efficient solution. Simplifying access to benefits and services is also critical.

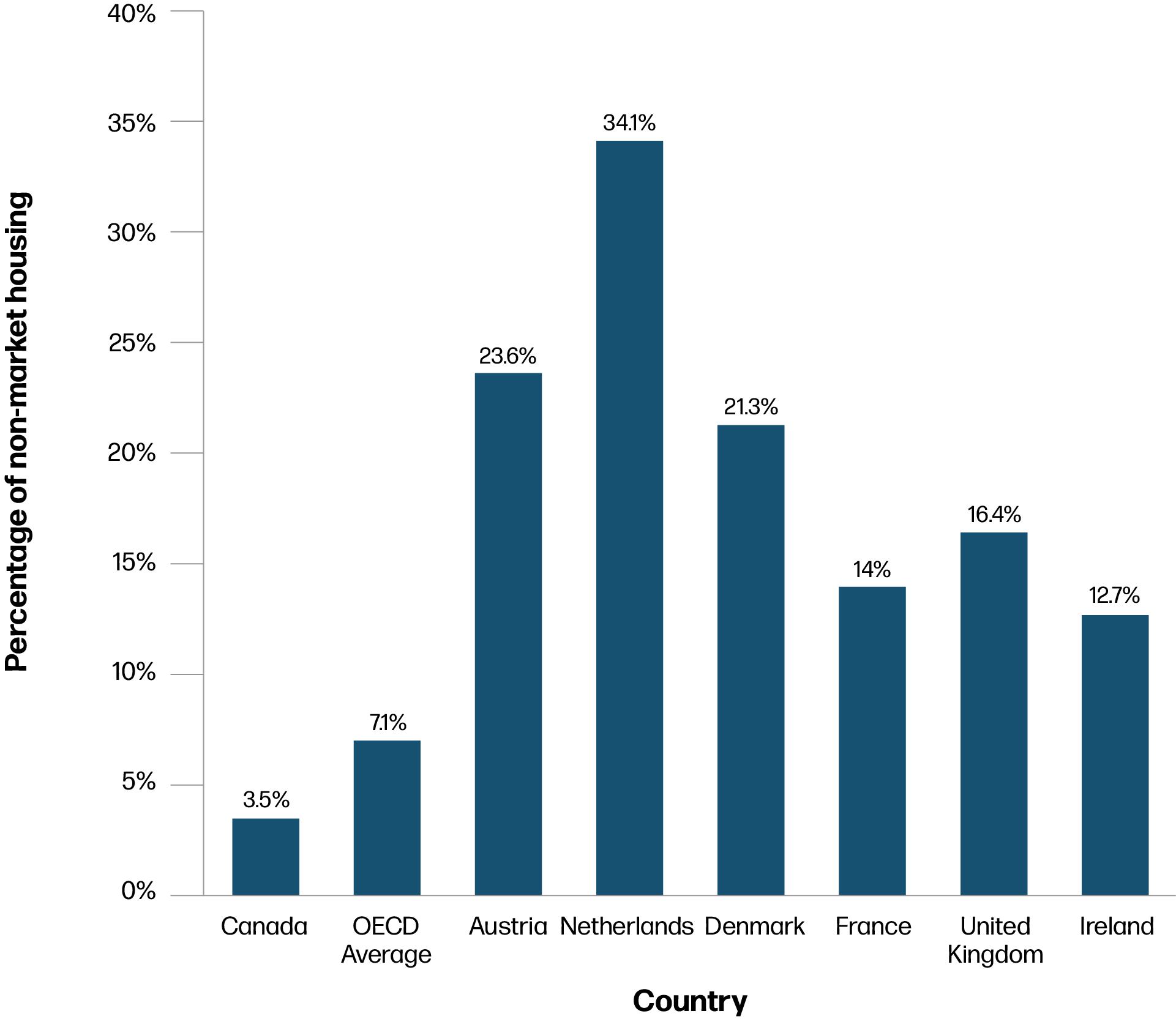

Housing remains a major concern, with the current focus on market-based solutions making it unaffordable for many. The Council calls on the Government to shift priorities toward non-market housing options and better-targeted support for those in core housing need.

Non-profit organizations that offer essential services and assistance, particularly to those made most marginal, are struggling with high demand and not enough funding. They need more stable and adequate funding and stronger federal actions to ease the pressure.

The Council also highlights the importance of supporting people through major life transitions, particularly with increased access to mental health and harm reduction services. Employment is another key factor in reducing poverty, as it promotes financial stability, social inclusion and economic growth. However, many face barriers to entering or staying in the workforce or finding jobs that pay a living wage. Addressing these challenges holistically is essential to breaking the cycle of poverty and ensuring that we leave no one behind.

Based on the conversations the Council has had with individuals experiencing poverty and those who support them, our analysis of the most current data, and our understanding of the current system of supports, we present the Government of Canada with the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Affordability and income support

To lift people out of poverty and to prevent others who are on the margins from falling into poverty, the Government of Canada needs to both increase income, through wages and/or benefits, and decrease costs of essentials for individuals.

Increase income:

To increase income, the Government of Canada should establish an income floor at or above Canada’s Official Poverty line. The Council recommends doing this in 1 of 2 ways:

- introduce a targeted basic income to ensure everyone reaches at least Canada’s Official Poverty Line through wages, government benefits or a combination of both

or

- reform and expand current income supports to more effectively meet the needs, based on regional realities, of those made most marginal. This should include:

- reviewing and improving federal income supports for groups with the highest poverty rates, such as unattached individuals between the ages of 25 and 64, people with disabilities, and equity deserving groups

- setting a living wage in all federally regulated workplaces by 2030 to encourage other levels of government to follow suit

- introducing legislation to strengthen accountabilities by tying Canada Social Transfer payments to provincial and territorial social assistance rates that meet a set percentage of the Market Basket Measure

Reduce costs:

While raising incomes is key to reducing poverty, the Government of Canada should also:

- look for ways to slow the rising cost of essentials—like food, transportation, clothing and other necessities—so that inflation doesn’t offset or cancel the income gains

Recommendation 2: Access to and awareness of benefits and supports

To ensure that everyone—especially those made most marginal—is aware of and receives the benefits they’re entitled to, the Government of Canada should take targeted steps to raise awareness and make access to federal benefits easier. These steps could include:

- making eligibility criteria more flexible so people who don’t fully qualify can still get partial support instead of nothing at all

- expanding automatic tax filing and auto-enrollment initiatives for people experiencing poverty, to help ensure they receive all the federal benefits available to them

- exploring new ways to simplify and streamline applications, making it faster, fairer and easier to use—this could include creating a single simplified application form or using digital tools (such as an electronic profile or key) that work across multiple benefit programs

- increasing and diversifying access points for in-person services (for example, from Service Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, and the Canada Revenue Agency) while continuing to improve phone, mail and online service options

- partnering with other levels of government, community organizations and the non-profit sector to raise awareness of benefits and supports and implement community-based pathways for easier access to benefits and services

Recommendation 3: Support for renters in market housing

To support renters in market housing and address the challenges they face—such as accessing safe, deeply affordable housing and receiving fair treatments by landlords—the Government of Canada should:

- work with provincial and territorial governments to develop and implement an action plan to support and protect renters. This action plan should include:

- ways to implement the policies set out in the Blueprint for a Renters’ Bill of Rights, published in September 2024

Recommendation 4: Investment in non-market housing

To meet housing needs, and support those who are homeless, the Government of Canada must increase non-market housing availability, affordability and adequacy. To do so, the Government of Canada should invest in:

- deeply affordable housing, such as non-profit, social and co-op housing, including projects on public lands and in mixed-income neighbourhoods to diversify housing types

- permanent supportive housing, which provides critical services to help people, once housed, stay housed

- repairing and retrofitting existing social housing to make it safe, in good condition, energy efficient, accessible and environmentally sustainable using Canadian materials

- expanding initiatives that improve housing access for those made most marginal

Recommendation 5: Support for the non-profit sector

To help stabilize an overextended non-profit sector that provides vital and essential supports to people experiencing poverty—particularly those who have been made most marginal—when and where they need them, the Government of Canada should:

- explore a new and efficient funding model that transfers money to provinces and territories to fund the core operations of non-profit groups that help reduce poverty and support people experiencing poverty. The transfer should:

- be process-based, not project-based, to provide stable, long-term, operational funding for non-profit organizations that respects autonomy in how they manage their resources and allows for:

- fair and equitable wages and working conditions for their employees

- flexibility to meet the complex and evolving needs of individuals

- time to develop and implement initiatives that focus on early interventions and prevention

- include an accountability framework with clear criteria around how provinces and territories use and distribute the funds

- focus on equity to help ensure that the funds serve individuals experiencing poverty—particularly those made most marginal

- be process-based, not project-based, to provide stable, long-term, operational funding for non-profit organizations that respects autonomy in how they manage their resources and allows for:

- explore ways to share and transfer knowledge proactively about government supports to non-profit sector service providers to empower them in their roles. This could include:

- providing a dedicated line of communication for organizations to approach the Government with questions about federal benefits, services and supports

Recommendation 6: Investing in mental health and harm reduction services

To further support individuals experiencing poverty who are dealing with mental health challenges, having difficulties with life events and transitions, or struggling with substance use, the Government of Canada should:

- increase and dedicate funding, such as through the health transfers to provinces and territories, for the delivery of low-barrier integrated mental health services. This could be by:

- further promoting and expanding the Integrated Youth Services model to support youth across the country, including those transitioning from the child protection system

- expanding or using a similar approach to the Integrated Youth Services model to reach other age groups

- co-develop standards, with other levels of government and service providers, for the delivery of services for people who are struggling with substance use and addictions, particularly those experiencing poverty. This could include:

- evidence-based best practices for harm reduction sites, detox centres, and other rehabilitation services

Recommendation 7: Supporting labour force participation

To make employment a pathway out of poverty, the Government of Canada must take action to remove the barriers that prevent individuals—particularly those made most marginal—from accessing and maintaining decent work. These barriers often arise at important employment-related transition points. Addressing these will require coordinated efforts across all levels of government, in partnership with the non-profit sector. To that end, the Government of Canada should:

- invest in wraparound supports for people transitioning between benefits (for example, social assistance) and employment

- incentivize employers to prioritize recruitment and retention of individuals from groups made most marginal. This should include:

- increasing opportunities for youth to join the labour force

- continue to increase access to employment benefits (such as employment insurance and paid sick leave) for self-employed workers, workers in the gig economy, and part-time workers

- invest in language, literacy, numeracy, and other essential life skills training programs to increase work readiness and mobility within the labour force

- enhance and reinvigorate trade skills training programs

- build clear and accessible pathways for skilled migrants to enter the labour market in their field. This could include:

- working with professional associations to fast-track foreign credential recognition

Introduction

Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy and the National Advisory Council on Poverty

In 2018, the Government of Canada released Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy. The Poverty Reduction Strategy set a vision and foundation for future government investments in poverty reduction. This foundation included:

- establishing an official measure of poverty, Canada’s Official Poverty Line, based on the Market Basket Measure

- setting concrete poverty reduction targets to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030, relative to 2015 levels (in 2015, the poverty rate was 14.5%, representing over 5 million people living in Canada who were in poverty)

- creating a National Advisory Council on Poverty (established in 2019) that is mandated to:

- advise the Government on poverty reduction

- report yearly on the progress made to meet the poverty reduction targets

- foster a national dialogue on poverty reduction

- passing the Poverty Reduction Act, which entrenches the targets, Canada’s Official Poverty Line and the National Advisory Council on Poverty in law

About this report

The National Advisory Council on Poverty prepares its annual report based on:

- public engagement with hundreds of individuals experiencing poverty and thousands of representatives from groups and organizations across the country

- a review of recently published articles and reports and a disaggregated analysis of poverty-related data from national surveys

- deliberations among members selected for their experience and expertise in poverty-related matters

In 2025, the Council met with individuals experiencing poverty and those who serve them in communities across Canada. In February 2025, we met with people in Winnipeg (MB), Scarborough (ON), Fredericton (NB), and Campbellton (NB). Planned sessions in Québec (QC) and Lévis (QC) were conducted virtually due to a snowstorm. Council members also met with individuals in their regions and had discussions with key stakeholders, national organizations and advocacy groups. Annex A provides a list of organizations that participated in these sessions.

Note:

The Council prepared this report based on what we heard during engagements with individuals, community organizations and service providers this year, available statistical data, and recently published reports. Each year, we strive to engage with a diverse range of people, but we couldn’t reach or speak with all groups due to time and resource limits. For those less involved in our discussions, we relied on data and published sources. While we have done our best to reflect what people shared and what we observed, we don’t claim to speak on behalf of everyone or for any specific group. This year, we were focused on hearing from people made most marginal, specifically about where they turn for help. However, we didn’t explore their various intersecting identities in depth. Some experiences shared are universal, while others are specific to certain groups. Understanding how overlapping identities relate to poverty is something the Council would like to explore in the future.

This year, the Council focused its attention on Canada’s social safety net to gain a deeper understanding of the landscape of both formal and informal supports in Canada. We aimed to assess the system’s effectiveness and efficiency in reducing poverty, while increasing dignity, opportunity, inclusion, resilience and security. We sought to keep the conversation on poverty alive and evolving, gathering views and evidence to offer informed, actionable advice to the Minister of Jobs and Families on effective approaches to reduce it.

The discussions focused on the different kinds of supports people rely on. These include formal supports like tax credits, benefits, services, programs, and both financial and non-financial assistance. The Council also heard about the importance of informal supports—like help from family, friends or neighbours, and trusted relationships in the community, such as with a pharmacist or postal worker—in the broader support landscape. These informal supports are closely tied to people’s sense of dignity, trust and belonging in their communities.

Specifically, through these conversations, the Council sought to better understand:

- the adequacy of existing supports for those who access them

- the challenges with access to and awareness of existing supports

- the changes required to existing supports or need for new supports

While examining the broader social safety net, we focused on federal supports, to learn more about what is working, what isn’t and who still requires more help. We asked people where they go for support, who helps them the most and what challenges they face in getting that help. We also asked for their ideas on how to make supports and services easier to access, available when and where they’re needed, and adequate to help people meet their needs and live with dignity. Annex B provides a glossary of terms used in this report.

The conversations we had were bold, open and honest. We heard some heartbreaking stories, while others shared their views with anger and frustration. But we also met people, community workers and service providers who are doing great things and showing strength in tough times. No matter the tone, each story and opinion helped the Council better understand how the system supports people—or should be supporting them—to meet their basic needs, find stability and move out of poverty. This report includes glimpses of these stories and reflects real experiences of poverty across Canada.

This report summarizes what we heard about supports needed for those experiencing poverty and provides advice on achieving the poverty reduction targets. Specifically, it includes:

- an update on the progress toward Canada’s poverty reduction targets using multiple data sources, including the Canadian Income Survey, the Census of Population, the Labour Force Survey, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment, the Survey of Financial Security, and the Longitudinal Administrative Databank

- views from those engaged on why addressing poverty matters

- an in-depth analysis of the key themes emerging from the Council’s conversations, particularly:

- affordability and income security

- access to and awareness of existing supports and services

- housing needs and impact on stability in one’s life

- investments required in communities, especially non-profit organizations providing essential and vital services

- life events and transition points during which individuals require additional or specific supports, notably mental health supports

- active labour force participation as a pathway out of poverty

- recommendations for federal consideration to further alleviate, and ultimately eliminate, poverty across the country

Setting the context

We live in extraordinary times, facing new and evolving challenges like health crises—including both COVID-19 and the opioid crisis—climate change, and ongoing global conflicts. Further, we write this report at a time of economic challenges and uncertainties, including ever-changing geopolitics, new trade realities and economic shifts. We need to respond quickly to protect Canadians currently experiencing poverty and protect others from falling into it.

At the same time, Canada’s poverty rate is rising and has been since 2021. Canada’s official poverty rate was 10.2% in 2023 (the most recent data available). Challenging economic conditions, such as high inflation, lagging wage growth, affordability issues and the complete phaseout of pandemic benefits, have contributed to recent increases in poverty. Benefit indexation helps to some extent, but often with a lag, and the cost of the basket of essentials to maintain a modest standard of living has increased.

To address these challenges Canada invests significantly in supporting people, in large part through the social safety net. The social safety net refers to a comprehensive system of programs and policies designed to provide support to people living in Canada, particularly those made most marginal. It refers to a combination of federal, provincial, territorial and municipal programs.

In 2023, Canada spent over $286.4 billion on social protection within the social safety net, including on programs like public pension and income security programs, family and disability benefits, unemployment supports, and efforts to reduce social exclusion. These investments come from all levels of government: federal, provincial, territorial and municipal (Statistics Canada, 2024e).

These programs provide people with both short-term and, when needed, long-term support, at different stages in their life course. Still, despite these investments, many individuals have told us that they continue to struggle to get by—and they’re worried things are only getting worse. Policy makers built the social safety net for a different era. With evolving challenges and crises, the current system isn’t flexible enough to adapt to meet current realities.

Some government investments are more effective at reducing poverty than others. For instance, the Canada Child Benefit has made a big difference in reducing child poverty. After the introduction of this benefit in 2016, child poverty dropped from 13.9% to 4.7% in 2020 but has slowly risen since then to 10.7% in 2023 (Statistics Canada, 2025b). The Old Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), along with the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), have provided many seniors with significant income support. This has resulted in a reduction in the poverty rate for seniors, going from 7.1% in 2016 to 3.1% in 2020, though this trend is now reversing and the poverty rate for seniors had risen to 5.0% in 2023 (Statistics Canada, 2025b).

The federal government has also put a lot of money into housing in recent years. However, poverty reduction wasn’t necessarily the main goal of these investments. Most of these investments were focused on market housing, which is often the least affordable housing option for those experiencing poverty. Given the limited investment in non-market housing, the Council was not surprised that access to safe and affordable housing emerged as the top concern among individuals experiencing poverty this year.

Over the years, the Council has heard about the challenges people face in accessing much-needed benefits and supports. People expressed frustration with networks of supports that are confusing, difficult to access, rigid, dehumanizing and inadequate. We heard about the perceived inefficiency of government spending on social programs and from individuals indicating they felt that some of these initiatives aren’t meeting intended targets, are excluding people or are inadequate to meet needs. For this reason, the Council decided to focus our attention this year on supports, including where individuals turn to for help, what works best for them and some gaps in services and challenges they encounter.

We heard that current foundational systems in Canada weren’t benefiting those with low incomes or were benefiting some population groups over others. For instance, the housing market is one of the cornerstones of the economy and has benefited from federal housing policy. It has produced significant profits for developers and those that own homes but has left behind others who don’t own property. More and more people are priced out of the market and an increasing number of people are houseless, homeless, living rough or living in unhealthy housing.

We also heard about the rising cost of food. Many people were concerned about the rise in food insecurity and the use of food banks at a time when some vendors were reporting large profits. This was a troubling sign warning us of deeper systemic issues in our food economy.

We have met yearly with different people experiencing poverty since 2020. We have noticed that the tone of the dialogue with Canadians has shifted over the years. Given the evolving social policy landscape, the hopefulness for meaningful change expressed during the COVID-19 pandemic has faded, replaced by increasing hopelessness, despair, division, and frustration. This year, a broader array of people raised concerns over the cost of living. Not only did individuals currently experiencing poverty express these concerns, but also those who are higher up the income scale. As people struggle to keep up with rising costs and lagging income, more are accessing services for the first time.

During the early part of the pandemic, the Government put in place a raft of benefits and supports. These included the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), eviction prevention, access to health care for the uninsured, expanded access to mental health care and the mobilization of municipal workers to increase social supports to communities. A similar effort to offer widespread benefits and supports to decrease the impacts of the current economic turmoil would help future-proof the nation. We know that the unmitigated impacts of the early pandemic still loom large on communities. Immediate action is essential to decrease the foreseeable effects of the current economic climate.

The Government of Canada has been effective in reducing poverty in the past. Poverty was on a downward trend from 2015 to 2020. We know it’s possible to do it. We need commitment and collaboration across governments to do it again and meet Canada’s poverty reduction target by 2030. In addition to the recommendations presented in this report, Annex C provides a list of the Council’s previous recommendations, which we continue to urge the Government to implement.

Chapter 1: Progress on meeting Canada’s poverty reduction targets

Poverty reduction targets

The National Advisory Council on Poverty reports yearly on the progress made in Canada toward meeting the targets to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030, relative to 2015 levels.

How poverty is measured

A person’s or family’s income level doesn’t always reflect their experience of poverty. However, income is often used as a proxy to measure poverty. The Poverty Reduction Act (2019) established an Official Poverty Line for Canada based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM).

Market Basket Measure

The MBM establishes poverty thresholds based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services representing a modest, basic standard of living. It includes the costs of food, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation and other items for a reference family. The current MBM methodology sets poverty thresholds for 53 geographic regions in the provinces and 13 regions in the territories. Such thresholds are adjustable to reflect families of different sizes. If an individual’s or family’s disposable income is below the threshold for their family size in a particular region, they’re considered to be living in poverty.

The current MBM uses a 2018 base. However, in June 2023, Statistics Canada launched the third comprehensive review of the MBM. The 2023 base of the MBM, to be officially introduced in the fall of 2025, proposes the use of updated data on shelter costs and household expenditures and more disaggregated data on food and clothing items to estimate MBM poverty thresholds. It also proposes the creation of a new communications services component for the MBM basket, to capture the costs of landline, cell phone and internet services for the MBM reference family (Devin et al., 2025). The Northern Market Basket Measure (MBM-N) for the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut uses a similar methodology to the MBM for the provinces. However, it includes adjustments needed to reflect life in these territories such as higher costs, unique geographical conditions found in the north and traditional practices in areas such as food and clothing.

MBM statistics aren’t produced for certain populations that are under-surveyed or not surveyed at all. For example, MBM statistics aren’t produced for First Nations people living on-reserve, people living in institutions, 2SLGBTQIA+ people, people with refugee status, people seeking asylum, and people experiencing homelessness.

Canadian Income Survey

Data from the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) are used to estimate poverty rates based on Canada’s Official Poverty Line. The CIS is an annual survey with an approximate 16-month lag between the end of the reference year and the availability of the results. The most current statistics are from the 2023 CIS, released on May 1, 2025.

Data from the CIS includes persons who reported having an Indigenous identity, that is, First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit), or those who reported more than 1 identity. Excluded from the survey’s coverage are persons living on-reserve and in other Indigenous settlements in the provinces. The Indigenous total includes data on persons reporting being Inuit or having multiple identities, but these aren’t shown separately because of small sample sizes.

Poverty in Canada, 2023

In 2023, according to Canada’s Official Poverty Line, the poverty rate was at 10.2%, which is nearly 4 million people experiencing poverty (Statistics Canada, 2025b). This represents a 30% decrease in the overall poverty rate compared to 2015 (14.5%) and roughly 1 million fewer people living in poverty in Canada since that time.

While the overall poverty rate has decreased compared to 2015, the poverty rate has increased for the third consecutive year in 2023. The 2023 poverty rate is also up 3.8 percentage points from 2020, when poverty was at its lowest point. This means that 1.5 million more people were experiencing poverty in Canada in 2023 compared to 2020.

After significant increases in 2021 and 2022, the poverty rate grew more slowly between 2022 and 2023. But if it doesn’t decrease, Canada will fail to meet the 2030 target of a 50% decrease in poverty compared to 2015.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 11-10-0135-01 Low-income statistics by age, sex and economic family type.

Text description of Graph 1:

| Year | Number of persons in poverty | Percentage of persons in poverty |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 5,044,000 | 14.5% |

| 2016 | 4,552,000 | 12.9% |

| 2017 | 4,260,000 | 11.9% |

| 2018 | 4,065,000 | 11.2% |

| 2019 | 3,793,000 | 10.3% |

| 2020 | 2,357,000 | 6.4% |

| 2021 | 2,762,000 | 7.4% |

| 2022 | 3,772,000 | 9.9% |

| 2023 | 3,971,000 | 10.2% |

Poverty in the provinces

The poverty rate varies by province. Between 2022 and 2023, poverty went down in Nova Scotia (12.9%), Manitoba (10.9%), Alberta (8.9%) and British Columbia (11.3%), but rose in all other provinces. The highest rates of poverty are in Saskatchewan (12.9%) and Nova Scotia (12.9%). In Saskatchewan, the poverty rate has now risen above the 2015 level (12.2%). Quebec remains the province with the lowest poverty rate (7.4%).

| Province | 2015 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 13.0% | 9.8% | 11.5% |

| Prince Edward Island | 15.7% | 9.8% | 11.3% |

| Nova Scotia | 16.8% | 13.1% | 12.9% |

| New Brunswick | 16.2% | 10.9% | 11.6% |

| Quebec | 13.5% | 6.6% | 7.4% |

| Ontario | 15.1% | 10.9% | 11.1% |

| Manitoba | 14.1% | 11.5% | 10.9% |

| Saskatchewan | 12.2% | 11.1% | 12.9% |

| Alberta | 9.4% | 9.7% | 8.9% |

| British Columbia | 18.6% | 11.6% | 11.3% |

Poverty in the territories

Canada’s overall poverty rate (based on the MBM) excludes poverty rates in the territories (based on MBM-N). In 2023, the poverty rate in the territories (22.8%) remained significantly above the provincial average (10.2%). This was also the case for each separate territory apart from the Yukon, which is below the provincial average. People in Nunavut (43.4%) experienced the highest poverty rate, followed by those in the Northwest Territories (17.0%) and the Yukon (9.9%).

Indicators of poverty

The MBM measures whether a person or family has the money to afford a modest standard of living. But the experience of poverty goes further than what the MBM measures. Opportunity for All – Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2018) established a dashboard of 12 indicators, under 3 key pillars, related to poverty:

- dignity: deep income poverty; unmet housing needs and chronic homelessness; unmet health needs; food insecurity

- opportunity and inclusion: relative low income; bottom 40% income share; youth engagement; literacy and numeracy

- resilience and security: median hourly wage; average poverty gap; asset resilience; low-income entry and exit rates

The dashboard isn’t comprehensive, but it allows progress to be tracked across several dimensions of poverty. The descriptions and latest statistics for each indicator are available on the Dimensions of Poverty Hub (Statistics Canada, 2025c). Statistics Canada publishes and maintains the Hub and tracks these indicators. The Government of Canada is also working to co-develop distinctions-based Indigenous indicators of poverty and well-being.

Poverty levels are lower in 2023 than they were in 2015. Some evidence showcases that deep income poverty has decreased (from 7.4% in 2015 to 5.3% in 2023) and the share of income of the lowest 40% has increased. However, several of the indicators have worsened since 2015 (or the initial year of measurement since tracking began under the Poverty Reduction Strategy). These trends are present in the following indicators:

- food insecurity (19.1% of people surveyed reported being in moderate or severe food insecurity in 2023, compared to 11.6% in 2018, when this data was first collected)

- unmet health care needs (9.1% of people aged 15 and older reported unmet health care needs in 2023, compared to 5.1% in 2018, when this data was first collected)

- average poverty gap ratio (increased to 33.3% in 2023 from 31.8% in 2015)

Several indicators improved prior to 2020, but have worsened since then:

- relative low income (decreased from 14.3% in 2015 to 12.0% in 2023)

- bottom 40% income share (increased from 20.2% in 2015 to 21.1% in 2023)

Several indicators of poverty haven’t been updated since the Council’s last report, as new data is not available. These include:

- unmet housing needs (decreased from 12.7% in 2016 to 10.1% in 2021)

- literacy and numeracy (low literacy rates increased from 10.7% in 2015 to 18.1% in 2022; low numeracy rates increased from 14.4% in 2015 to 21.6% in 2022)

- low-income entry rates of tax filers (increased from 3.9% in 2015–2016 to 5.0% in 2021–2022)

- low-income exit rate of tax filers (increased from 27.6% in 2015–2016 to 32.5% in 2021–2022)

Groups made most marginal

Throughout our reports, we refer to different groups that are underserved and overlooked. We have identified these groups from data and engagement sessions over the years. These groups face structural and systemic barriers, violence, discrimination, racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, ableism and colonialism. This makes them more likely to experience poverty. When we refer to groups made most marginal, these include (in alphabetical order):

- Black and other racialized communities

- children and youth, particularly those under the care of child welfare and youth justice systems

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis people

- people experiencing homelessness

- people involved in the criminal justice system

- people living in institutions (such as long-term care homes)

- people living in rural or remote areas

- people who have immigrated to Canada

- people with disabilities

- people with refugee status or who are undocumented

- seniors

- Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual people, and people who identify as part of sexual and gender-diverse communities who use additional terminologies (2SLGBTQIA+)

- unattached (single) individuals aged 25 to 64

- women

Poverty rates among groups made most marginal remain higher than average and reflect persistent inequality throughout the country. The poverty rate for racialized persons was 14.0%, up 1.0 percentage point from 2022 (13.0%), but decreased for non-racialized Canadians (8.5%). In 2023, 17.5% of the Indigenous population living off-reserve lived below the poverty line and the Indigenous population has persistently been significantly more likely to be experiencing poverty compared to the non-Indigenous population (9.9%).

| Group | 2015 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overallᶧ | 5,044,000 (14.5%) | 3,772,000 (9.9%) | 3,971,000 (10.2%) |

| Males | 2,438,000 (14.1%) | 1,859,000 (9.9%) | 1,964,000 (10.1%) |

| Females | 2,606,000 (14.8%) | 1,912,000 (10.0%) | 2,007,000 (10.2%) |

| Singles (under age 65) | 1,582,000 (38.9%) | 1,426,000 (31.0%) | 1,497,000 (31.4%) |

| Male singles (under age 65) | 838,000 (36.5%) | 769,000 (30.1%) | 790,000 (29.9%) |

| Female singles (under age 65) | 744,000 (41.9%) | 657,000 (32.1%) | 707,000 (33.4%) |

| Children aged 0 to 2 | 196,000 (17.4%) | 115,000 (11.1%) | 114,000 (10.8%) |

| Children aged 3 to 5 | 208,000 (18.5%) | 127,000 (10.5%) | 139,000 (11.7%) |

| Children aged 6 to 11 | 386,000 (16.7%) | 248,000 (10.3%) | 281,000 (11.4%) |

| Children aged 12 to 17 | 324,000 (14.2%) | 246,000 (8.9%) | 267,000 (9.5%) |

| Seniors (aged 65+) | 394,000 (7.1%) | 430,000 (6.0%) | 373,000 (5.0%) |

| Persons in lone parent families | 545,000 (32.8%) | 498,000 (22.6%) | 564,000 (24.8%) |

| Persons in male-led lone parent families | 65,000 (18.9%)* | 75,000 (17.6%)* | 81,000 (18.0%) |

| Persons in female-led lone parent families | 480,000 (36.4%) | 423,000 (23.8%) | 483,000 (26.5%) |

| Indigenous people living off-reserve (aged 15+)ᶧᶧᶧ | 205,000 (26.2%) | 167,000 (17.5%) | 174,000 (17.4%) |

| Indigenous people living on-reserve | not collected | not collected | not collected |

| 2SLGBTQI+ persons | not collected | not collected | not collected |

| Persons with disabilities (aged 15+)ᶧᶧᶧ | 1,535,000 (20.6%) | 1,110,000 (12.3%) | 1,105,000 (12.0%) |

| Immigrantsᶧᶧ (aged 15+)ᶧᶧᶧ | 1,303,000 (17.5%) | 937,000 (10.7%) | 1,022,000 (11.0%) |

| Recent immigrantsᶧᶧ (10 years or less) aged 15+ᶧᶧᶧ |

649,000 (28.3%) | 373,000 (14.0%) | 438,000 (15.3%) |

| Very recent immigrantsᶧᶧ (5 years or less) aged 15+ᶧᶧᶧ |

423,000 (34.9%) | 239,000 (16.4%) | 299,000 (17.8%) |

| Racialized persons** | not collected | 1,437,000 (13.0%) | 1,676,000 (14.0%) |

| South Asian | not collected | 346,000 (11.5%) | 480,000 (14.0%) |

| Chinese | not collected | 273,000 (15.6%) | 278,000 (16.4%) |

| Black | not collected | 233,000 (13.9%) | 297,000 (15.5%) |

| Filipino | not collected | 77,000 (6.2%) | 69,000 (5.4%) |

| Arab | not collected | 157,000 (18.7%) | 130,000 (15.7%) |

| Latin American | not collected | 85,000 (11.3%) | 107,000 (13.6%) |

| Southeast Asian | not collected | 73,000 (12.3%) | 59,000 (9.2%) |

| Other racialized persons*** | not collected | 193,000 (16.2%) | 255,000 (17.8%) |

| Persons living in institutions | not collected | not collected | not collected |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 11-10-0135-01 Low-income statistics by age, sex, and economic family type; Table 11-10-0136-01 Low-income statistics by economic family type; Table 11-10-0090-01 Poverty and low-income statistics by disability status; Table 11-10-0093-01 Poverty and low-income statistics by selected demographic characteristics.

Notes:

- ᶧ The estimated poverty rates in this table only include data from Canada’s provinces.

- ᶧᶧ Referred to by Statistics Canada as people who are, or have been, landed immigrants in Canada. Canadian citizens by birth and non-permanent residents (persons from another country who live in Canada and have a work or study permit, or are claiming refugee status, including family members living here with them) aren’t considered landed immigrants.

- ᶧᶧᶧ Persons aged 16 years and over for years before 2022.

- * Statistics Canada indicates that these data should be used with caution.

- ** Referred to by Statistics Canada as persons designated as visible minorities.

- *** Other racialized persons include racialized groups other than Black, Chinese, Latin American, Filipino, Arab, South Asian or Southeast Asian, and persons who identified as more than one racialized group.

Chapter 2: Why it matters

Many people are fortunate enough to go through life never experiencing poverty. Poverty means having fewer choices and limited say or influence. Sometimes, it also means people feel treated with less dignity. Poverty is the result of complex forces. It’s not only about money—many complicated factors in our society and the economy can cause poverty. These include both past and present decisions made in our communities, across Canada, and around the world.

To understand poverty, we need to look at the bigger picture. Things like colonialism, oppression, trauma passed down through generations, lack of opportunities, systemic racism, discrimination, abrupt life changes, mental health challenges and addiction all play a role. Without this understanding, people might wrongly blame individuals for being poor, instead of seeing how our systems have created poverty. Those experiencing poverty face challenges that many others can’t even imagine. Everyone deserves the opportunity to live a life with dignity where their needs are met—without feeling shame or being hurt even more by the process.

For this report, as in past reports, the Council is putting the voices of people who have experienced poverty front and centre. The quotes throughout the report are from conversations held with individuals in different parts of the country with whom we spoke this year. These quotes reflect the views of individuals and organizations touched by poverty, directly or indirectly, day to day. These individuals generously shared their thoughts with us. By sharing their voices within the pages of this report, we hope to build or rebuild empathy for our neighbours, friends and families who face challenging circumstances.

Based on what we heard during our engagement sessions this year, we have summarized the reasons why addressing poverty matters. These views and stories help us better understand how people experience poverty. They demonstrate why the fight against poverty is a national priority. It causes deep and lasting harm to those who experience it, and it has ripple effects felt across Canada. In a country as prosperous as Canada, allowing so many people to struggle to meet their basic needs is a failure of our collective values.

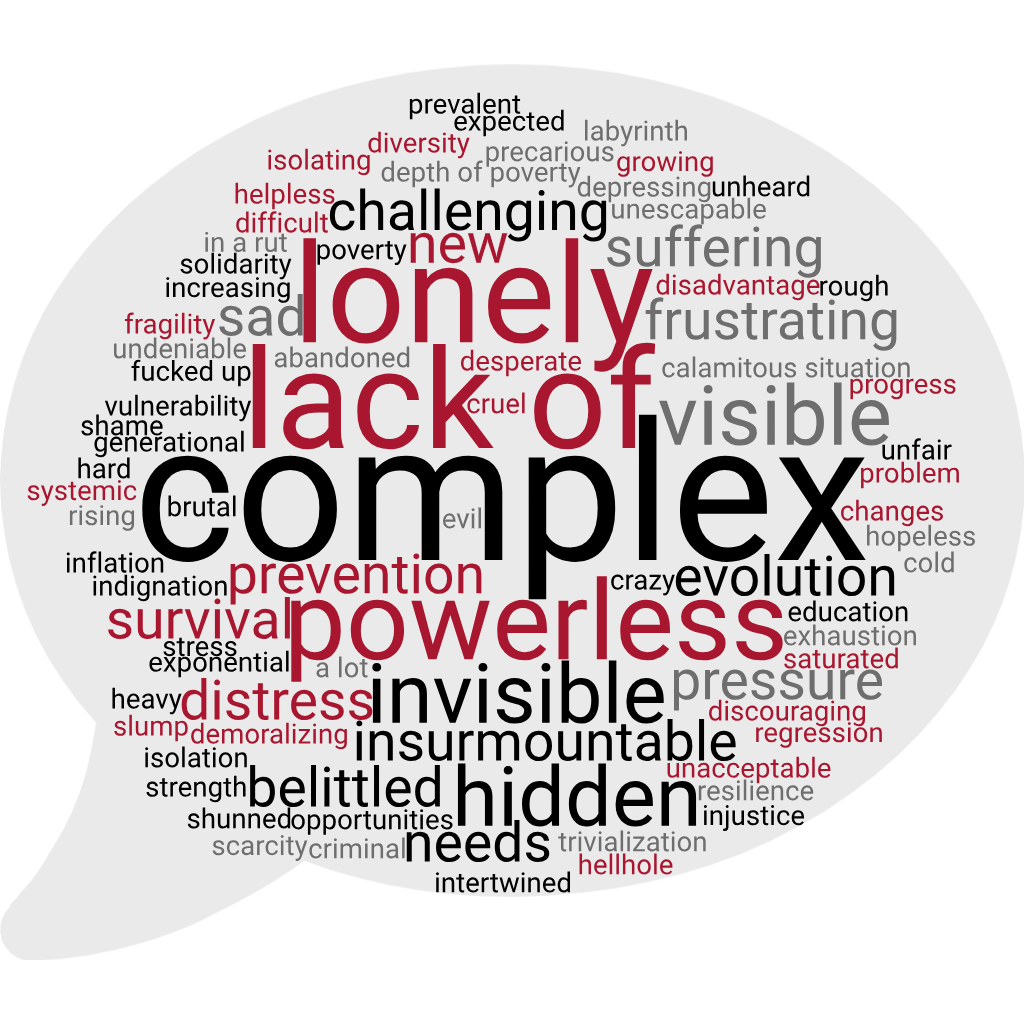

Why it matters: Poverty in one word

In the Council’s conversations, we asked for one-word answers to the question: “What does poverty look like or feel like in your community?” The image below brings together these words. The bigger the word, the more often people said it.

Text description of word cloud:

Words – the higher the word is on the list, the more often people said it:

complex

lack of

lonely

powerless

hidden

invisible

visible

belittled

challenging

distress

evolution

frustrating

insurmountable

isolating

needs

new

pressure

prevention

sad

suffering

survival

a lot

abandoned

brutal

calamitous situation

changes

cold

crazy

criminal

cruel

demoralizing

depressing

depth of poverty

desperate

difficult

disadvantage

discouraging

diversity

education

evil

exhaustion

expected

exponential

fragility

fucked up

generational

growing

hard

heavy

hellhole

helpless

hopeless

in a rut

increasing

indignation

inflation

injustice

intertwined

labyrinth

opportunities

precarious

prevalent

problem

progress

regression

resilience

rising up

rough

saturated

scarcity

shame

shunned

slump

solidarity

strength

stress

systemic

trivialization

unacceptable

undeniable

unescapable

unfair

unheard

vulnerability

Why it matters: Poverty is persistent

Some people described poverty as an epidemic. Those experiencing poverty expressed feeling increasingly desperate amid rising costs that cause suffering and increase poverty. People spoke of the difficulties in affording food, transportation, housing, clothing and other essential needs. They expressed concern about the rising cost of living and stagnating income. This causes more people to experience poverty or struggle to leave it. Additionally, many spoke of intergenerational poverty and trauma. In these circumstances, culturally appropriate services, where people’s languages, traditions and values are respected, and where they feel truly heard and understood, play a vital role in helping individuals move out of poverty. Some called for greater access to mental health supports for people with trauma.

The Council believes it is important to meet the Government’s poverty reduction targets, and that the goal should be that no one experiences poverty. The increasing poverty rate is alarming, as that means more of our neighbours, friends and family members are living in poverty.

In their own words: Poverty is persistent…

Intergenerational trauma and poverty

- “I come from failure on this side and failure on that side, so what am I going to be?”

- “I come from a family that continues to face intergenerational trauma. My whole life, I felt like I was destined to end up the way my whole family ended up.”

- “I see the way that it has affected my family and everyone I have been surrounded by my whole life. We have been affected by something that was not in our control. We have been placed into this curse.”

- “It is going to take 7 generations to get away from the trauma of the ’60s Scoop.”

Survival mode

- “It’s 2025 and hard to believe we are still living under these circumstances.”

- “Forget quality of life, it is just survival.”

- “We are tired of being in survival mode, and therefore, we cannot be productive.”

- “You’re in survival mode all the time.”

- “We are just existing.”

- “We’re all trying to fight to live for just 1 more day.”

- “It’s exhausting that we have to use all of the resources just to survive.”

Why it matters: Poverty is an ongoing struggle

People experiencing poverty described it as all-encompassing and insurmountable. They described feeling demoralized and depressed as they try to get ahead but fail repeatedly. It’s hard for many to see a way out because they feel continually dragged down and exhausted.

Experiencing poverty means struggling to meet basic needs. For some, it leaves little time, energy or money to pursue interests and passions. It’s difficult to think about what comes next when you’re struggling to survive. The Council believes that people should be able to access supports and services in a dignified, simple and seamless way.

Having said this, people experiencing poverty emphasized the need to focus on their strengths. These strengths shape the way they treat each other and navigate the world.

People expressed fear for the future as their sense of community and collective action continues to diminish. The global political context has increased anxiety about the future, particularly for those who already feel left behind. People feel the economy is beyond repair. Youth is afraid of what the future will hold for them if things don’t change.

In their own words: Poverty is an ongoing struggle…

The struggle

- “It’s my life! I don’t really realize it.”

- “I spend a lot of time keeping my head above water.”

- “I’m just trying to make it to tomorrow. That is all I am doing.”

- “I’ve struggled my whole life.”

- “You want poverty to get better, but they just keep holding us down.”

- “People are struggling here a lot.”

- “It’s a struggle to survive.”

- “Everything we go through in life sticks to us.”

Survival

- “You learn resilience when you have to deal with it all the time, so I will figure it out.”

- “When you go through trying periods, you learn to adapt.”

- “It could get better. I can get better.”

- “We are trying to ‘soften our days’ so that each day can be a good enough day.”

- “My integrity is the 1 thing I hold on to.”

- “Every day is a gift.”

- “Keep fighting.”

- “Another day is starting, deal with it. It takes too much energy to be angry at everything. It sucks the life out of you.”

Fear for the future

- “I fear for the future.”

- “There’s a lot of anxiety stemming from the White House.”

- “I don’t have hope. There is no hope to help get you on your feet.”

- “I do have a bit of hope because there are people who are trying to fix it, like you guys.”

- “We’re all suffering from the same thing. We can’t help each other.”

Why it matters: Poverty is dehumanizing

Those living with poverty described feeling infantilized, dehumanized and stigmatized by systems and supports, unable to speak up for themselves and judged when they do. Youth in care said that adults treated them as if they couldn’t understand the systems, while also failing to teach them how those systems work. Those living with poverty expressed feeling shunned by society and judged for using supports. They noted that people have said they should be grateful for the help they receive, even when it’s inadequate.

The Council believes that everyone deserves a life with dignity, where systems treat people with respect and provide them with opportunities to achieve their goals. By accepting poverty, we are accepting the dehumanization and marginalization of others.

In their own words: Poverty is dehumanizing…

- “We’ve been kicked around, slapped around, stepped over in a puddle.”

- “We’re damaged, man.”

- “It’s getting to the point where I don’t have anything to lose anymore.”

- “Poverty makes a man lose his dignity, lose his mind; he becomes an animal.”

- “There is no autonomy.”

- “Everyone wants to be humanized.”

- “The whole system is very judgmental.”

- “We have emotions. We are humans.”

- “We are really humiliated.”

- “We are already poor. We are all humiliated, and we need to be appreciative for the small amount we get.”

- “Too many people are comfortable and don’t know what it is like to be uncomfortable, so they don’t care if people are homeless.”

Why it matters: Poverty is systemic

Poverty is systemic. This means that it’s not an individual’s fault or a result of bad decisions, but the consequence of structures, policies and programs that create and perpetuate economic and social disadvantage for some people. Our systems created poverty. Colonialism, racism, discrimination, some existing programs and policies, and unfounded assumptions put people at risk of experiencing poverty or keep them in poverty. Many of the current systems don’t work for everyone. They create and perpetuate inequality and injustice. At the same time, we heard about the people that are benefiting from these systems and the poverty they create. These include employers paying low wages, landlords taking advantage of vulnerable tenants and unregulated housing markets, and grocers profiting from both shrinkflation and skimpflation.

Some individuals expressed concern that systems often seem designed to create total dependency in people, making transitions out of the cycle of poverty tough. People feel like they’re locked into dependence on charity or government supports, facing punishment for attempting to make progress. For example, individuals currently receiving social assistance or other benefits reported that the system takes back the additional money they earn from employment. This means that they’re no further ahead when they’re working. Some people also mentioned losing non-income benefits (such as housing, discounted or free public transportation access, or other programming) if they leave social assistance. These types of clawbacks make people feel like they can’t get ahead and make them remain dependent on the income support system.

Our current systems don’t always uphold fundamental human rights, like the right to live free from discrimination. Many people lack adequate income, safe and secure housing, nutritious food, and reliable transportation. Those living with poverty described numerous ways the systems fail them. Because systems created poverty, we should be able to use these systems to reduce and eliminate poverty. The Council believes that the Government should reform or adjust the systems to lift all people above the poverty line and prevent others from experiencing poverty at all.

In their own words: Poverty is systemic…

- “People don’t think about the total dependency they create for people. Then they blame them for being dependent.”

- “We have a system where you have to be in crisis to get help.”

- “You’re stuck in a system that is not helping you.”

- “That’s the cycle keeping us in poverty.”

- “You’re having to make programs for people because your systems are broken. If you look at what’s wrong with your systems, and the problems they’re creating, you’ll be saving a lot of money.”

- “We have a system that does not support people.”

- “All of the government regulations put in place are designed to keep people down.”

Why it matters: Poverty needs to be prevented rather than treated

While recognizing that governments make significant investments to assist people experiencing poverty, several people expressed concern that policy makers put too much focus on and invest too much in addressing the symptoms rather than the root causes of poverty. They believe that governments implement short-term band-aid solutions that fail to solve the issues. Some supports offered provide temporary relief and make it easier to cope with poverty but prevent people from moving out of or beyond poverty. Providing supports after people are in crisis is too late.

Sometimes, the solutions contribute to perpetuating poverty. Individuals felt that the Government is more focused on making poverty invisible rather than getting rid of it. Others, particularly community organizations and service providers, indicated they felt like the Government doesn’t prioritize large investments to prevent or eliminate poverty due to a lack of political will or courage. For instance, many people criticized decisions made by provincial, territorial and federal governments to provide one-off assistance cheques rather than investing that money in prevention strategies.

The Council believes that it is better and more cost-effective to support people before they’re in crisis or fall into poverty rather than providing emergency supports or temporary relief. Research suggests that the costs of poverty, such as lost productivity, increased health care usage and criminal justice expenses, far exceed the costs of addressing poverty through proactive social investment (National Council of Welfare Reports, 2011). A report from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) outlined that reducing child poverty can have huge spillover effects on society. It’s estimated that $1 invested in the early years saves between $3 and $9 in future spending on the health and criminal justice systems and on social assistance (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2008). A growing body of evidence internationally and within Canada demonstrates that investing to eliminate poverty costs less than allowing it to persist.

In their own words: Poverty needs to be prevented rather than treated…

- “If we want a safe and healthy community, we have to pay for it. Everyone wants this, but no one wants to pay for other people to have it. We often hear: ‘I don’t want my tax money going to fund people who don’t work.’”

- “We are trying to put a band-aid on an open-heart surgery.”

- “They don’t want to do it. They want to look like they’re doing something.”

- “One-time $200 cheques are not going to help me get a psychiatrist or get my daughter to the doctor faster. Just put the money where it needs to go.”

- “It is harm production, not harm reduction.”

- “They’re just using band-aids to fix things, and it isn’t enough.”

Why it matters: Poverty doesn’t discriminate but can be the result of discrimination

Equity

We heard from many people that poverty doesn’t discriminate—anyone can experience poverty—but that some supports and programs designed to alleviate poverty are discriminatory. Black people, racialized people, Indigenous people, newcomers to Canada, 2SLGBTQIA+ people and people with a disability all spoke to the racism and discrimination they faced in housing, employment, schooling or when accessing supports. Examples included:

- landlords who refused to rent to people with non-European sounding names

- 2SLGBTQIA+ youth who didn’t feel safe in local employment areas

- food banks restricting their services to families only and excluding single people

- employers who overlooked resumes from newcomers

By sharing their stories, people confirmed to the Council that discrimination and racism continue to play a role in creating and perpetuating poverty. They recommended focusing on fairness to fix the harm caused by colonialism, racism and discrimination. Without this focus, the system continues to reinforce the unfair treatment of people in areas like income, health, inclusion and opportunity. People also saw justice as a way to correct past wrongs and improve lives. When justice is a priority, everyone can feel respected, valued and included.

Furthermore, recognizing that poverty is multifaceted, many individuals expressed concerns that poverty affects some groups more than others, pointing to the intersectionality of identities that compound the effects and risks of living below the poverty line. Intersectionality refers to the intersecting effects of categories such as race, class, gender and other characteristics that contribute to an individual’s social identity. It also refers to the complex and cumulative ways in which social identities interact, combine or overlap. People hold multiple, sometimes overlapping, identities, some of which may be marginalized. The more marginalized identities a person has, the higher their risk of poverty.

Urban Indigenous people

Indigenous people we met with shared that they face ongoing hate, discrimination and racism which makes it hard for them to receive services or participate in activities that most take for granted, such as obtaining health care or pursuing their education. They also said they don’t trust government services and institutions because of past experiences. Some Indigenous people said they feel like they’re constantly watched, under a microscope, like people are waiting for a reason to take their children away.

Many individuals experiencing poverty emphasized the need to improve access to benefits for Indigenous people. They described a lack of stable funding for Indigenous organizations and supports, including culturally appropriate education and training opportunities such as programs focused on culture and identity reclamation. Additionally, many spoke of the trauma of the ’60s Scoop, where over 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and home communities by the child welfare system, in concert with many other systems. This traumatic experience makes building relationships and trusting service providers, such as family services, very challenging.

Others noted the lack of training offered to Indigenous staff and a general lack of funding to Indigenous organizations. This limits the capacity of these organizations, prevents opportunities for Indigenous people, and often results in only meeting basic needs, instead of investing in building community and preventing poverty.

Some people noted that the Government is trying to do the right thing by introducing various benefits and programs, but for too many Indigenous people who are struggling, it feels performative and sometimes doesn’t make much sense. Some feel the Government should “get out of the way and stop fighting First Nations and let them organize for themselves,” allowing for moral and economic dignity.

Researchers lack the necessary data to report on poverty for First Nations, Inuit and Métis people. Nonetheless, the data available indicates that Indigenous persons living off-reserve continued to be significantly more likely to experience poverty in 2023 (17.5%) compared to the non-Indigenous population (9.9%) (Statistics Canada, 2025b).

However, this fails to capture all the factors relevant to poverty for Indigenous people, including geography, band membership, infrastructure and the presence of treaties. For example, poverty conditions on-reserve include a lack of clean water, overcrowded and deplorable housing conditions, limited or non-existent access to health care, and the high cost of food in northern and remote communities.

The Council would like to stress the immediate need to reduce poverty among First Nations, Inuit and Métis people. Colonialism and racism have impacted generations of people. This includes land theft and displacement, the forced removal of children through residential schools and the child welfare systems, and the Indian Act’s role in controlling cultural practices and identity. These harms require a systemic renewal of relationships that puts truth and reconciliation at the centre. It requires the Government of Canada to:

- be responsible to the treaties made between First Nations and Canada

- understand the ongoing impacts of systemic and systematic colonialism