Harassment and sexual violence in the workplace

Official title: Harassment and sexual violence in the workplace public consultations - what we heard

Alternate formats

Harassment and sexual violence in the workplace Public consultations What We Heard [PDF - 536 KB]

Request other formats online or call 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105. Large print, braille, audio cassette, audio CD, e-text diskette, e-text CD and DAISY are available on demand.

On this page

Minister message - What we heard report

Consultation on harassment and violence

No one should be subject to harassment or sexual violence of any kind in their workplace, whether it comes from an employer, a manager or a colleague.

Over the course of my career, I have worked with many people who have survived the physical, psychological and practical consequences stemming from violence. I have seen the effect it has on their lives, and on communities.

As Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour, I have been mandated by the Prime Minister to ensure that federal workplaces are free from these unacceptable behaviours.

Over the last year, we’ve consulted Canadians on the best ways to make that happen.

Canadians responding to our online survey told us that harassment and sexual violence in workplaces are underreported, often due to fear of retaliation, and that when they are reported, they are not dealt with effectively. We know that these incidents have profound negative effects, such as harming workers’ health and safety, increasing absenteeism, and costs for employers.

Through roundtable discussions and teleconferences, we also heard from many stakeholders and experts who provided valuable insight into these issues and what needs to be done to address them.

In collaboration with the Leader of the Government in the House of Commons, I also held consultations on Parliament Hill with Members of Parliament and Senators, to ensure this government can also fulfill its commitment to ensure that Parliament is a workplace free from harassment and sexual violence.

This report reflects all these voices, and what we have learned about Canadians’ experiences with harassment and sexual violence at work, as we prepare to take action.

I thank everyone who participated in our consultations. Your contributions are helping us develop ways to address these unacceptable issues.

The Honourable Patty Hajdu, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour

Executive summary

Background

The Government of Canada is taking action to ensure that federal workplaces are free from harassment and sexual violence. We consulted Canadians over the last year to find out how violence and harassment are currently treated in workplaces under federal jurisdiction and how the approach could be strengthened.

The consultation took two forms. We asked all Canadians to respond to an online surveyFootnote 1, and we held a series of roundtable meetings and teleconferences with stakeholders: labour organizations, employer organizations, federal government departments and agencies, academics, and advocacy groups. We also invited stakeholders to provide written submissions. This report presents an overview of what we heard during the consultations. Based on qualitative and—when available—quantitative analysis, it summarizes the issues that participants raised and the experiences they recounted concerning harassment and violence in their workplaces.

Key findings

High levels of harassment and violence

The stakeholder consultations highlighted the need to recognize harassment as an ongoing pattern of inappropriate conduct. Similarly, most online survey respondents who reported that they have experienced harassment, sexual harassment or violence in the past two years indicated that they experienced these behaviours more than once. HarassmentFootnote 2 was the most common type of behaviour experienced by online survey respondents—a full 60% reported having experienced it. Thirty percent of respondents said that they had experienced sexual harassment, 21% that they had experienced violence and 3% that they had experienced sexual violence.

Stakeholders raised the importance of looking at harassment from the perspective of gender-based violence and other forms of discrimination. Among survey respondents, 94% of those who reported experiencing sexual harassment were women, while people with disabilities and members of a visible minority were more likely to experience harassment than other groups.

Preventing incidents of workplace harassment and violence

Stakeholders stressed the importance of prevention measures and highlighted the need to raise awareness among employers and employees about issues of harassment and violence. Similarly, 54% of the survey respondents said that they would like to see education for all supervisors, 51% said that they would like to see education for all employees and 39% thought that an awareness campaign would be useful.

The consultations also suggested that training and education would help employers to understand and respond to what is happening in their workplaces. Most survey respondents reported that although their workplaces have sexual harassment and violence prevention policies in place, they did not receive training on these policies.

Responding to incidents

Stakeholders told us that the goal of any changes to the current legislative and regulatory framework for dealing with violence and sexual harassment should be to reduce their incidence and speed up the internal complaints process. Stakeholders thought that employers should be encouraged to try to resolve issues internally and should be given flexibility to decide how to do this before bringing in a neutral third party. In this regard, stakeholders saw workplace committees as helpful in implementing policies.

Stakeholders felt that employers should be obliged to consider any recommendations made by a neutral third party and that complainants should have access to recourse if an employer refuses to implement a recommendation without offering a valid explanation.

The consultations also underlined that any change to the current framework should differentiate between sexual harassment and violence, since sexual harassment is highly sensitive and raises different privacy considerations.

Although 75% of survey respondents who had experienced harassment, sexual harassment or violence reported the most recent incident, 41% of them stated that no attempt was made to resolve the issue. Of those respondents who did not report the most recent incident, many feared reprisals if they filed a complaint.

Supporting those who experience incidents

Most survey respondents expressed the view that the employer, followed by the Government and unions, should be responsible for providing supports to help victims feel safe and secure in their workplace. Just over half suggested that education for all employees and supervisors would help victims. Stakeholders wanted clear written policies for how organizations respond to allegations of workplace violence and harassment. They told us that these policies must include explicit protection against retaliation for reporting an incident.

Reporting and recording

Stakeholders identified under reporting and insufficient data on workplace harassment and violence as major issues that should be addressed in any new regulatory regime. They also agreed that to reduce workplace harassment and violence and speed up resolution, data should be collected to track results, and privacy of the data collected must be ensured.

Introduction

Despite progress in raising employment and health and safety standards in Canada, too many people continue to experience harassment and violence at work. All workers should be protected against harm in the workplace—including harassment and violence. We are committed to taking action to ensure that federal workplaces are free from harassment and violence, including sexual violence.

To support evidence-based policy development and implementation, and to ensure that a wide range of voices were heard, we launched a series of engagement activities with the Canadian public, unions, employers, non-governmental organizations, academics and other experts.

Two types of consultations took place: a public consultation through an online survey; and a series of roundtables and teleconferences with stakeholders, who were also invited to provide written submissions.

Online survey

The online public consultation was open from February 14 to March 9, 2017. The main goal of the survey was to better understand the types of harassing and violent behaviours that take place in Canadian workplaces, risks that contribute to these behaviours, preventive measures, responses and supports that are being provided, and resources that can help end workplace violence and harassment.

We received a total of 1,349 valid responses to the online survey. Of these, 834 were completed in full and 580 were incomplete. The online survey was composed mostly of closed-ended questions, as well as some partially open-ended questions that allowed participants to provide qualitative responses to fully express their views.

All participants in the online survey self-selected—therefore, they should not be taken as representative of the Canadian population. Annex A presents an overview of survey respondents. Some key facts about them:

- 1005 respondents identified as female; 200 respondents identified as male;

- Over 35% of respondents had a bachelor’s degree;

- Nearly 32% of respondents had a degree above the bachelor’s level; and

- Over 61% of respondents lived in Ontario.

Roundtables and teleconferences

We consulted with stakeholders between June 2016 and April 2017, in three phases:

Phase one: In June and July, we held roundtables with employers, employer and labour associations, advocacy groups, and representatives from other federal government departments and agencies (see Annex B for full list of participants). We also invited stakeholders to provide written submissions in response to questions in a short discussion paper related to the current legislative and regulatory regime for violence and sexual harassment. The results of these meetings and written submissions formed the basis of the second phase of engagement.

Phase two: We held a series of teleconferences in fall 2016. Our goal was to share and validate the key takeaways heard in phase one, and seek views on more specific issues related to violence and harassment in federally regulated workplaces. Attendees at these teleconferences included employers, employer and labour organizations, academics, and members of community groups.

Phase three: In March we held a ministerial roundtable with employee and labour associations. In April, the Minister also consulted with the Status of Women’s Advisory Council on the Federal Strategy Against Gender-based Violence. We asked participants to respond to questions outlined in a backgrounder that was distributed before the events (see Annex C).

This report presents an overview of what we heard from stakeholders during the consultations and what respondents told us in the online survey. We identify key messages and provide additional information about the issues raised. The first section focusses on the different types of harassing behaviours that are being experienced in the workplace. The next three sections discuss what we heard about best practices in dealing with harassment and violence in the workplace—what consultation participants think should be done to prevent it, respond to it when it happens, and support victims.

Details findings

I. Experiencing harassment and violence

This section reports on what consultation participants told us about the types of harassing and violent behaviours that Canadians are experiencing in their workplaces, as well as risks that can contribute to these behaviours. Online survey respondents provided most of the information in this section. A profile of online survey respondents can be found in Annex A.

Types of harassing and violent behaviours

We asked online survey respondents if they had ever experienced harassment, sexual harassment, violence or sexual violence in the workplace. We also asked if they had experienced these types of behaviours in the past two years, then asked a series of follow-up questions about the most recent incident.

We asked respondents about risk factors in their workplaces. We asked them to select from a list of risk factors that research has shown to contribute to workplace harassment, sexual harassment, violence and sexual violence. "Harassment” alone in the survey referred to non-sexual harassment, and "violence” alone to non-sexual violence.

It's important to note that of the online survey respondents, 1,005 identified as female and only 200 identified as male.

Key messages

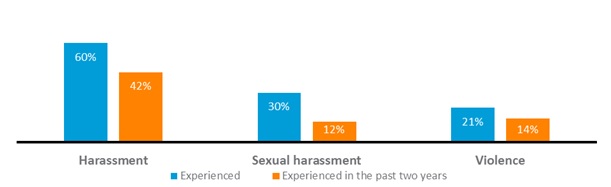

- Online survey respondents reported that harassment was the most common type of behaviour, with 60% having experienced it. Sexual harassment was experienced by 30%, violence by 21% and sexual violence by 3%.

- Most respondents who experienced harassment, sexual harassment or violence in the past two years indicated that they experienced these behaviours more than once. Stakeholder consultations also highlighted the need to recognize that harassment is usually an ongoing pattern of behaviour.

- Half of the survey respondents said that they experienced the harassing or violent behaviour from an individual with authority over them, while 44% experienced the behaviour from a co-worker.

- Among respondents who experienced an incident in the past two years, men were more likely to have experienced harassment than women, and women were more likely to have experienced sexual harassment. Women were also more likely to have experienced violence.

- Respondents who experienced sexual harassment tended to work in environments with a higher ratio of men in positions of power than respondents who experienced non-sexual harassment or violence.

- People with disabilities and members of a visible minority group were more likely to experience harassment than other groups.

Text description of Figure 1

| Experienced | Experienced in the past two years | |

|---|---|---|

| Harassment | 60% | 42% |

| Sexual harassment | 30% | 12% |

| Violence | 21% | 14% |

Q1. Have you ever experienced any of the following in your workplace? Base: All respondents, n = 1,178.

Q2. Have you experienced any of the following in your workplace during the past two years? Calculated using a base of n = 1,178.

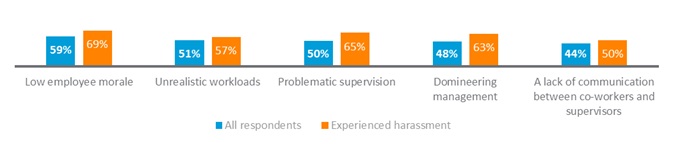

Text description of Figure 2

| All respondents | Experienced harassment | |

|---|---|---|

| Low employee morale | 59% | 69% |

| Unrealistic workloads | 51% | 57% |

| Problematic supervision | 50% | 65% |

| Domineering management | 48% | 63% |

| A lack of communication between co-workers and supervisors | 44% | 50% |

QC17. Research suggests that there are particular risks that can contribute to the occurrence of harassment in the workplace.

Of these risks, have you experienced any in your workplace?

Base: All respondents, n = 869.

Base: Experienced harassment most recently, n = 327.

Text description of Figure 3

| All respondents | Experienced sexual harassment | |

|---|---|---|

| A high ratio of women in your immediate work team | 37% | 23% |

| A high ratio of women in your workplace | 36% | 17% |

| A high ratio of men in positions of power within the organization | 35% | 65% |

| Employees are unaware of the reporting procedures that are available for incidents of workplace sexual harassment | 35% | 48% |

| Employees are unaware of the grievance procedures that are available for incidents of workplace sexual harassment | 31% | 42% |

QC18. Research suggests that there are particular risks that can contribute to the occurrence of sexual harassment in the workplace.

Of these risks, have you experienced any in your workplace?

Base: All respondents, n = 842.

Base: Experienced sexual harassment most recently, n = 60.

"Sexual harassment is still a problem for all women and particularly for more vulnerable women:

Usually, the most vulnerable women are those in lower-paying or less secure jobs; those of a different race or colour than the majority of workers; women in non-traditional types of employment; women with a visible or invisible disability; lesbians; older women; and women whose religion sets them apart from the majority."

Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF)

written submission

Stakeholders raised gender as an important risk factor. One stakeholder suggested in a written submission that sexual harassment acts as a significant barrier to women’s full participation in the paid work environment. They also raised the importance of looking at harassment that is experienced due to other identity factors, such as age, ability or ethnicity, and the need for protections against all forms of discrimination, not just gender-based violence.

Both survey respondents and stakeholders considered the absence of victim support a major risk factor.

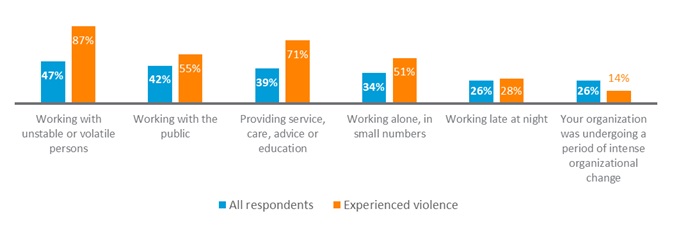

Text description of Figure 4

| All respondents | Experienced violence | |

|---|---|---|

| Working with unstable or volatile persons | 47% | 87% |

| Working with the public | 42% | 55% |

| Providing service, care, advice or education | 39% | 71% |

| Working alone, in small numbers | 34% | 51% |

| Working late at night | 26% | 28% |

| Your organization was undergoing a period of intense organizational change | 26% | 14% |

QC19. Research suggests that there are particular risks that can contribute to the occurrence of violence in the workplace.

Base: All respondents, n = 809.

Base: Experienced violence most recently, n = 85.

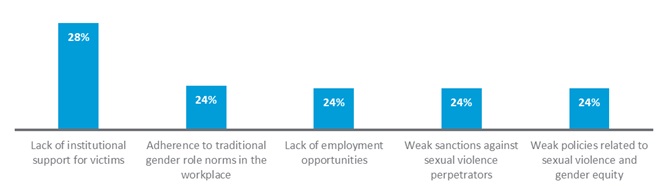

Text description of Figure 5

| Lack of institutional support for victims | 28% |

|---|---|

| Adherence to traditional gender role norms in the workplace | 24% |

| Lack of employment opportunities | 24% |

| Weak sanctions against sexual violence perpetrators | 24% |

| Weak policies related to sexual violence and gender equity | 24% |

QC20. Research suggests that there are particular risks that can contribute to the occurrence of sexual violence in the workplace.

Of these risks, have you experienced any in your workplace?

Base: All respondents n = 704.

II. Preventing incidents of harassment and sexual violence in the workplace

This section summarizes data from the online survey on workplace policies for prevention, as well as stakeholder recommendations on building awareness, educating employers and employees and the role workplace committees play in prevention.

Workplace policies for prevention

To understand the type of prevention policies in place, we asked online survey respondents whether their workplaces have sexual harassment and violence prevention policies in place, and if so, whether training on the policies is available.

Key messages

- Most survey respondents indicated that their workplaces have sexual harassment and violence prevention policies in place, but many of these respondents did not receive training on their workplace policies. Employer size did not appear to influence whether workers were aware of policies related to sexual harassment or violence prevention.

What else we heard

Sexual harassment policies

Just over half of survey respondents agreed with the following statement: "My employer takes preventative actions to create a workplace free from sexual harassment.”

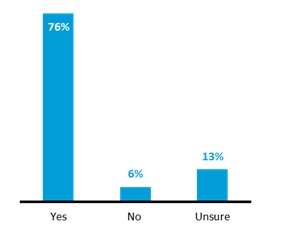

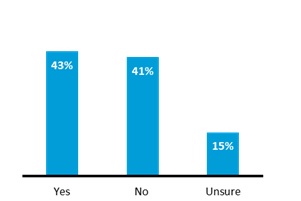

About 76% of survey respondents indicated that their workplace has a sexual harassment policy. However, only 43% of this group have participated in training on the policy. The most common type of training received was web-based training, followed by classroom training.

Around half of the online survey respondents who answered the question about their workplace sexual harassment policy indicated that it outlines the consequences for engaging in these types of behaviours, while 31% are unsure of the consequences.

Text description of Figure 6

| Yes | No | Unsure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 76% | 6% | 13% |

Text description of Figure 7

| Yes | No | Unsure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 43% | 41% | 15% |

QC1. Does your employer have a sexual harassment policy? Base: All respondents, n = 931.

QC3. Have you received training on the sexual harassment policy? Base: Those who have a sexual harassment policy, n = 713.

Violence prevention policies

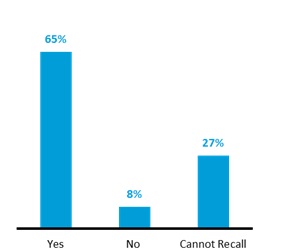

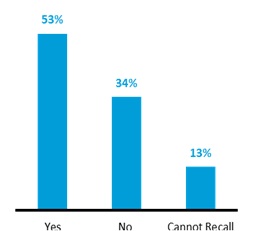

Of the survey respondents who answered the question about workplace violence prevention policies, 65% say a policy is in place. Of those who have a workplace policy, most were given the opportunity to read the policy, while half received violence prevention training. Online training (for example, human resource downloads) is the most common type of violence prevention policy training provided by employers, followed by video or slide show presentations.

We asked survey respondents if they received training on the nature and extent of violence and how they may be exposed to it in their workplace. About 28% of the respondents who answered this question received this type of training. For those who did receive training, 85% said that the training recognized that bullying, teasing and abusive behaviour can constitute workplace violence.

Text description of Figure 8

| Yes | No | Cannot recall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 65% | 8% | 27% |

Text description of Figure 9

| Category | Yes | No | Cannot recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 53% | 34% | 13% | |

| 309 | 198 | 79 |

QC8. Does your employer have a violence prevention policy? Base: All respondents, n = 915.

QC10. Have you received training of the workplace violence prevention policy? Base: Those who have a violence prevention policy, n = 586.

Awareness campaigns

Stakeholders told us that there is a need to raise awareness among employers and employees of their rights and obligations regarding harassment and violence.

Key messages

- Stakeholders stressed that prevention should be the primary focus and should precede any legislative changes.

- The consultations revealed the need for additional human and financial resources to raise awareness.

- Stakeholders recommended that workplace champions and ambassadors promote educational materials and training opportunities to increase awareness of harassment and violence.

- Of the survey respondents who answered the question about what could help them feel safe and secure in their workplace, 39% indicated that an awareness campaign would be a useful resource.

Education materials and tools

Stakeholders told us that ongoing education in the workplace for employees, managers and leaders at all levels is important in preventing violence and harassment.

"Our first recommendation is to include a short segment on sexual harassment in the union’s presentation made during the correctional training program. Future correctional officers must be clearly told that those behaviours are not acceptable, are not part of the job. They must also be explained what are their options to deal with that kind of behaviour."

Inmates' Sexual Harassment on Correctional Officers

Working Group Report

Key messages

- Both stakeholders and survey respondents identified the need to educate supervisors and employees about issues of harassment and violence.

- More than half of survey respondents who answered the question about what supports could help them feel safe and secure in their workplace said they would like to see education for all supervisors, and half would like to see education for all employees.

- The consultations revealed that employer training and education could lead to an improvement in employers’ listening skills, and increased capacity to understand what is happening in their workplace.

What else we heard

One advocacy group proposed that educational toolkits be prepared and shared with other levels of government. Another stakeholder mentioned the broad prevention approach that has been implemented in Ontario. This includes prevention and education at the entry level. (For example, the awareness program on high school and university campuses has resulted in positive changes.)

Workplace committees and training

Some stakeholders told us that workplace committees and health and safety officers could play a key role in prevention.

Key messages

- Stakeholders agreed that workplace committees can play a role in implementing policies and internal processes, and can monitor compliance and address non-compliance.

- While workplace committees can be an important prevention tool, stakeholders stressed that committee members require more training on issues of workplace harassment and violence before they can be involved.

- It was suggested that training committees could also be a good starting point for shaping change in workplace culture.

- One stakeholder pointed out that even with mediators and resources that provide support, employees still need training.

- Some employers, particularly small businesses, had concerns related to the costs associated with the new regime, including potential training costs.

III. Responding to incidents of harassment and violence

This section highlights what survey respondents and stakeholders told us about appropriate responses to workplace harassment and violence.

Resolving incidents

We asked survey respondents to indicate the actions taken to resolve their most recent incident of harassment or violence—whom they notified about the incident, who helped resolve the issue, processes used to resolve the issue, as well as the outcome of the incident and satisfaction with the outcome.

Key messages

- Around 75% of survey respondents who experienced harassment or violence took action—but 41% of them reported that no attempt was made to resolve the issue.

- Most respondents who took action to address their experience faced obstacles when trying to resolve the issues. Satisfaction with how incidents of harassment and violence were resolved was low.

- Following their most recent experience of harassment or violence, 86% of respondents returned to their place of work.

What else we heard

Of the online respondents who took action to address their experiences with harassment or violence, most discussed the matter with a co-worker (64%) or with their supervisor (58%). Relatively few respondents discussed the matter with a human resources advisor (22%) or with the workplace committee or health and safety representative (12%).

About half of respondents who reported their incident indicated that the issue was not resolved. Those incidents that were resolved tended to be resolved by unions (21%), supervisors (20%) or co-workers (19%). Very few matters were resolved by a workplace committee or health and safety representative (3%).

We asked respondents about the types of processes used to resolve their most recent incident. Just over 40% indicated that no attempt was made to resolve the issue, while 21% used an informal conflict resolution process provided by the employer and 16% filed a formal complaint. Around 5% of cases involved using a “competent person” (neutral third party) to conduct an investigation.

Resolution was difficult for respondents, and 75% of those who experienced an incident indicated that they faced obstacles while trying to resolve the issues. Common barriers were:

- the supervisor or manager did not take the complaint seriously

- the supervisor or manager did not initiate an investigation

- the employee experienced retaliation from individuals in positions of authority

"The Director swept the issue under the carpet."

online survey respondent

We asked survey respondents: "What was the outcome of your most recent incident?" Nearly half indicated that the most recent incident they experienced had "no outcome." Around 65% of respondents were dissatisfied with the outcome of the process, while 44% stated they are "still experiencing the negative behaviours."

For the respondents who did not report their most recent experience, the reasons for not reporting were mixed. Some of the common responses were:

- afraid their supervisor and/or employer would retaliate against them

- afraid reporting would hurt their career advancement

- scared to come forward

- concerns about the complaint process (for example confidentiality, how long it would take)

- afraid to lose their job

- not sure if the action would be considered harassment/sexual harassment/physical violence or sexual violenc.

"I was in a contract position and was worried that a grievance would hurt my chances for permanent hire."

online survey respondent

"Assumed it would not be taken seriously as it was happening in front of—and at times by management—so had no reason to believe anything would be done about it."

online survey respondent

The main reason for not reporting the incident by those who experienced harassment or violence was concern that their supervisor and/or employer would retaliate against them. The main reason provided by those who experienced sexual harassment was that they felt the issue was too minor. Some noted that harassment and violence are seen as part of their job, and therefore not taken seriously.

Single regime

The current legal framework for dealing with violence and sexual harassment in federally regulated workplaces is set out in the Canada Labour Code.

This subsection summarizes what we heard during the stakeholder consultations about the legislative and regulatory regime for violence and sexual harassment, in Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) and Part III (Labour Standards) of the Canada Labour Code and the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations.

Violence prevention in the workplace is addressed in Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of the Code. Part II applies to the federally regulated private sector (for example, banking, international and inter-provincial rail, air and road transportation, marine shipping, broadcasting and telecommunications, federal Crown corporations and the federal public service).

Sexual harassment is addressed in Part III (Labour Standards) of the Code, which applies to federally regulated private sector workplaces and federal Crown corporations. It does not apply to the federal public service.

Key messages

- Stakeholders agreed that the goal of any changes to the current framework should be to reduce harassment and violence and speed up internal resolution of complaints.

- Employees and employer associations agreed that existing regulations should be simplified and clarified.

- Some stakeholders agreed that it could be useful to put Part III sexual harassment under Part II of the Code to simplify and clarify the legislative and regulatory requirements. However, the main concern was that sexual harassment would have to be differentiated from workplace violence, as sexual harassment is a more sensitive type of harassment, raising different privacy considerations.

- Stakeholders highlighted the need for employers to have clearly defined workplace policies on harassment and violence, including how to report incidents.

What else we heard

The responsibility and leadership role of employers in discouraging inappropriate behaviour in the workplace before it escalates into a violent or harassing incident affecting an employee was raised as the core element in any regulatory regime. There should be zero tolerance for harassment and violence in the workplace, which requires employees and employers to work together on prevention and resolution.

Some stakeholders expressed concern about the lack of a definition of psychological violence, saying that the term is open to multiple interpretations. It was recognized that bullying and teasing should be considered forms of psychological violence. In addition, the term should be broad enough to include many forms of harassment, such as homophobia and gender-based violence. One barrier cited by 20% of online survey participants was uncertainty about whether the actions they experienced would be considered harassment or violence. Having a clear definition of psychological violence or of a continuum of psychologically violent behaviour would address this problem.

Stakeholders told us that clear written policies must outline:

- the types of behaviour the organization considers to be workplace harassment or violence

- what steps the organization expects employees to take when they become aware of an incident of workplace harassment or violence

- how the organization will respond to allegations of workplace violence or harassment

- explicit protection against retaliation for raising a concern about workplace harassment or violence

- regular reviews of all policies and practices

- multiple channels for reporting incidents, including a channel that does not involve the parties’ direct management

"Employers should be required as part of the violence prevention program to establish appropriate procedures for preventing, limiting harm from and responding to abuse, bullying or harassment in the workplace."

CUPE

written submission

A few stakeholders suggested that the Labour Program may wish to consider reporting of incidents from bystanders and expand current regulations beyond the workplace to include domestic violence. It was also stressed that no individual should be forced to make a complaint.

Investigations

Stakeholders discussed the role of the “competent person” in investigating complaints of violence under Part XX of the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations. Under this part, an employer is required to appoint a competent person when a complaint cannot be resolved informally.

Key messages

- Some stakeholders suggested that the Labour Program maintain a list of competent persons or act as an intermediary when there is disagreement on the selection of the competent person.

- Some recommended that the Labour Program take the lead by setting clear standards for the role of a competent person and ensure consistency in the application of the Regulations across its regions.

- During the roundtables and in the written submissions, most stakeholders identified the need for confidentiality for all parties in any harassment or violence investigation to be confirmed under the Code. This is essential to ensure the issue does not spread beyond the accuser and the accused.

- Stakeholders stated that health and safety officers should not be involved in the investigation of harassment and violence complaints.

- Stakeholders noted that workplace committee members would be better placed in a role related to the implementation of policies.

"Sexual harassment, arguably the most private and sensitive of workplace issues, should be managed by experts not a committee of an employee’s peers. Allowing these committees to be privy to information regarding sexual harassment could have a chilling effect on making complaints in this area."

Canadian Bankers Association,

written submission

What else we heard

One stakeholder noted that while appointing a competent person is the responsibility of the employer, committees and representatives could participate in developing the requirements for the list of competent persons.

Stakeholders said that the competent person mechanism can be effective if the role and responsibility are clearly understood. One stakeholder suggested that impartiality needs to be better defined and others suggested that there should be enough federal resources available to perform the function of competent persons.

There was general agreement that workplace committees and health and safety representatives should not play a role in appointing a competent person and should not receive a copy of the final report resulting from an investigation by a competent person. This ensures that the identity of those involved is protected and that the cases remain confidential. It was suggested that workplace committees be advised only of any findings relevant to their workplace rather than receiving the entire report.

Informal resolution

Stakeholders noted the importance of informal resolution processes as a first step for dealing with issues of harassment and violence in the workplace.

Key messages

- Stakeholders said that any changes to the existing regime should encourage employers and employees to first attempt to resolve their issues internally.

- Stakeholders stressed that it is important for employers to have the opportunity to understand what the issues are and to address them before going to a competent person.

- Employers should have flexibility in the resolution options they can use based on their unique workplace structure. For example, some organizations have informal conflict resolution practices in place, while others look to mediators.

- Any formal investigative process, such as appointing a competent person, should be used only when other means of resolution have not worked, and must be managed in a timely and cost-effective manner.

What else we heard

Most stakeholders agreed that a competent person should be assigned after other attempts to resolve the issue have failed. Assigning a competent person early on can hinder the internal complaint resolution process and limit an employer’s ability to work with parties to resolve the issue.

Stakeholders mentioned that health and safety officers should be better equipped to provide advice in what can be considered highly emotional and sensitive situations.

Offering multiple reporting channels is particularly important when an employer or supervisor is the alleged harasser. Stakeholders gave examples of other reporting channels, such as a human resources advisor or an employee ombudsman office within the organization.

Corrective measures

There was a consensus that an employer should be responsible for corrective action where there is evidence of harassment or violence. However, many respondents were skeptical that such action is being taken.

Key messages

- Only 51% of online survey respondents agreed that their employer would take corrective action against an offender or offenders in the event of an incident.

- An employer should be able to explain why it is or is not recommending an independent investigation.

IV. Supporting victims of incidents of harassment and violence

In the online survey, we asked respondents to indicate the types of supports that were made available to them following the most recent incident they experienced.

Key messages

- Of those who experienced some type of harassment or violence, 23% reported that their employer did not provide any supports following the most recent incident.

- The vast majority of survey respondents (88%) believe that employers should be responsible for providing resources to employees who allegedly conducted or participated in workplace harassment or violence, compared to 49% who thought the Government should be responsible and 39% who thought that unions should be responsible.

- Most survey respondents (61%) suggested counselling would be beneficial for those who allegedly conducted or participated in workplace harassment or violence.

What else we heard

Survey respondents were also asked about the types of supports and resources that are available in their workplaces for victims of sexual harassment. The most common type of support identified is employee assistance programs. However, only 32% of respondents who identified sexual harassment resources felt that the resources provided by their workplace to victims offered adequate support.

Only 30% of respondents indicated that their employer assists employees who have been exposed to workplace violence. Common types of resources provided for those who have been exposed to workplace violence were employee assistance programs and counselling and psychological services.

V. Reporting and recording

Stakeholders noted that the prevalence of incidents of harassment and violence is not clear, since victims must first report incidents, and then information must be collected and shared with a central body, such as the Government.

Key messages

- Under reporting and insufficient data on workplace harassment and violence was cited as a major issue that should be overcome in any new regulatory regime.

- Stakeholders agreed that to reduce workplace harassment and violence and speed up resolution, the necessary data should be collected to track results.

- Some stakeholders suggested that while employers require detailed records to update their policies, processes and supporting tools, the Labour Program only needs a small subset of information.

- Most submissions recognized the need to respect the privacy of the individuals involved and recommended that the Government be mindful of how reporting requirements could create opportunities for breaches of the parties’ privacy.

What else we heard

Stakeholders provided examples in their written submissions about the types of data that should be reported. Some examples of the detailed data that they said employers should report to the Labour Program include:

- the parties involved

- the nature of the incident

- the number of incidents

- the dates of the incidents and time lost

- details about the nature of the injury and type of medical attention sought

- a description of how resolution was reached, including the methods and resources used to resolve the incident

- the recommendations

- a description of how the recommendations were implemented

- the final outcomes of the recommendations

Two stakeholders mentioned that information should be recorded in a way that allows for gender disaggregation. Gender information about the person who committed the act and the victim should be collected. Data collected should be gender-inclusive due to the high rate of violence experienced by transgendered people.

Next steps

We are grateful to the people and organizations that devoted time and effort to tell us about their experiences and share their ideas on preventing and addressing workplace harassment and sexual violence. It is clear that, as a government and as a society, we have our work cut out for us. We listened carefully and are using the information that was shared with us to take meaningful action to counter these profoundly damaging behaviours.

Annex A - Online survey participation

The online survey was open from February 14 to March 9, 2017.

The survey received a total of 1,349 valid submissions. Among the valid submissions, 834 were completed in full and 580 were incomplete.

This annex provides an overview of the 1,349 participants who responded to the survey.

| Percentage of respondents | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Country of residence | 1,241 | |

| Resident of Canada | 98% | 1,217 |

| Not a resident of Canada | 1% | 12 |

| Do not wish to respond | 1% | 12 |

| Province or territory of residence | 1,187 | |

| Alberta | 6% | 69 |

| British Columbia | 11% | 135 |

| Manitoba | 2% | 26 |

| New Brunswick | 1% | 7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1% | 9 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.08% | 1 |

| Nova Scotia | 3% | 38 |

| Nunavut | 0% | 0 |

| Ontario | 61% | 727 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1% | 8 |

| Quebec | 13% | 149 |

| Saskatchewan | 1% | 11 |

| Yukon | 0.17% | 2 |

| Gender of respondents | 1,219 | |

| Female | 82% | 1,005 |

| Male | 16% | 200 |

| Transgender | 0.4% | 5 |

| Non-binary | 1% | 9 |

| Sexual orientation of respondents | 1,220 | |

| Heterosexual (sexual relations with people of the opposite sex) | 86% | 1,053 |

| Homosexual, that is lesbian or gay (sexual relations with people of your own sex) | 3% | 34 |

| Bisexual (sexual relations with people of both sexes) | 4% | 52 |

| I do not wish to respond | 7% | 81 |

| Designated groups | 1,095 | |

| Women | 89% | 972 |

| Indigenous persons | 3% | 28 |

| Persons with a disability | 11% | 116 |

| Members of a visible minority | 11% | 125 |

| I do not wish to respond | 5% | 53 |

| Age of respondents | 1,243 | |

| 17 and under | 0.08% | 1 |

| 18 to 34 | 24% | 297 |

| 35 to 49 | 44% | 551 |

| 50 to 54 | 12% | 151 |

| 55 to 64 | 16% | 200 |

| 65 or older | 2% | 26 |

| I do not wish to respond | 1% | 17 |

| Educational level | 1,220 | |

| Some high school | 0.3% | 4 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 7% | 80 |

| Registered apprenticeship or other trades certificate or diploma | 2% | 19 |

| College, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma | 18% | 216 |

| University certificate or diploma below bachelor’s level | 6% | 72 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 35% | 429 |

| Post-graduate degree above bachelor’s level | 32% | 387 |

| I do not wish to respond | 1% | 13 |

| Language spoken most often at home | 1,213 | |

| English | 73% | 885 |

| French | 13% | 152 |

| English and French | 8% | 100 |

| English and other non-official language | 3% | 40 |

| French and other non-official language | 0.16% | 2 |

| English, French and non-official language | 1% | 12 |

| Other/Non-official language | 1% | 15 |

| I do not wish to respond | 1% | 7 |

| Employment status of respondent during | 809 | |

| Working full-time (35 or more hours per week) | 87% | 704 |

| Working part-time (less than 35 hours per week) | 8% | 67 |

| Self-employed | 1% | 8 |

| Unemployed but looking for work | 0.12% | 2 |

| A student attending school full-time | 2% | 19 |

| Retired | 0.24% | 2 |

| Do not wish to answer | 1% | 8 |

| Type of employment during most recent | 779 | |

| Permanent position | 85% | 663 |

| Non-permanent seasonal job | 2% | 15 |

| Non-permanent temporary, term or contract job | 12% | 91 |

| Non-permanent casual | 1% | 10 |

| Industry at time of most recent experience | 784 | |

| Accommodation and food services | 3% | 23 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 1% | 5 |

| Air transportation | 1% | 4 |

| Armed forces | 1% | 5 |

| Banking | 0% | 3 |

| Construction | 1% | 7 |

| Educational services | 30% | 232 |

| Federal public service | 29% | 228 |

| Feed, flour, seed and grain | 0% | 1 |

| Health care and social assistance | 10% | 82 |

| Indigenous governments | 1% | 4 |

| Information and cultural industries | 2% | 14 |

| Manufacturing | 2% | 13 |

| Maritime transportation | 0% | 1 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 0% | 2 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 4% | 28 |

| Rail transportation | 0% | 2 |

| Retail trade | 3% | 22 |

| Road transportation | 0% | 2 |

| Telecommunications | 2% | 13 |

| Utilities | 1% | 9 |

| Wholesale trade | 0% | 1 |

| Other | 11% | 83 |

* Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Annex B - Stakeholder engagement

Written submissions

The following people and organizations provided written submissions.

Employers

- Air Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Status of Woman Canada

- Treasury Board Secretariat

Employer organizations

- Canadian Bankers Association

- Federally Regulated Employers – Transportation and Communications (FETCO)

Unions and Labour organizations

- Canadian Union of Public Employees

- Inmates’ Sexual Harassment on Correctional Officers Working Group Report

- Union of CBC’s National Health and Safety Policy Committees

Advocacy groups, community groups and other organizations

- Jacquie Carr and Sharon Scrimshaw, Centre of Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children, Western University

- Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF)

Stakeholder participation

The following organizations and individuals participated in roundtable meetings and teleconferences from June 2016 until April 2017.

June 17, 2016

- Air Canada

- Canada Post Corporation

- Canadian Trucking Alliance

- Canadian Union of Public Employees

- CBC/Radio-Canada

- Department of National Defence

- Public Service Alliance of Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Status of Women Canada

- Treasury Board Secretariat

- Union for Canada (UNIFOR)

July 6, 2016

- BC Maritime Employers Association

- Bell Canada

- Brinks Canada

- Canada Air Transport Security Authority

- Canada Bankers Association

- Canada Post Corporation

- Canadian Labour Congress

- Canadian Union of Public Employees

- CBC/Radio-Canada

- Federally Regulated Employers-Transportation and Communications (FETCO)

- International Longshore and Warehouse Union

- Maritime Employers Association

- NAV Canada

- Treasury Board Secretariat

October 26, 2016

- Federally Regulated Employers – Transportation and Communications (FETCO)

- Union for Canada (UNIFOR)

October 27, 2016

- BC Maritime Employers Association

- Canadian Armed Forces

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Trucking Alliance

- Department of National Defence

- House of Commons

- Justice Canada

- Treasury Board Secretariat

October 28, 2016

- Canada Bankers Association

- Canadian Red Cross

- Barb McQuarrie, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women & Children, Faculty of Education, Western University

- DisAbled Women’s Network

- Federally Regulated Employers-Transportation and Communications (FETCO)

- Ontario Native Women’s Association

- Status of Women Canada

- Sandy Welsh, University of Toronto

November 23, 2016

- Canadian Labour Congress

March 20, 2017

- Aboriginal Chamber of Commerce

- Canada Bankers Association

- Canadian Labour Congress

- Federally Regulated Employers – Transportation and Communications (FETCO)

- International Longshore and Warehouse Union

April 10, 2017

- Advisory Council on the Federal Strategy Against Gender-based Violence

Annex C - Backgrounder

Taking action against harassment and sexual violence in federal workplaces

The Government of Canada is taking action to ensure that federal workplaces are free from harassment and sexual violence.

According to Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey (GSS), there were 22 incidents of reported sexual assault per 1,000 Canadians aged 15 or over in 2014 and the rate of sexual violence against female victims was about seven times the rate for males.

Based on the GSS, the Labour Program of Employment and Social Development Canada estimates that there were about 14,100 employees in the federally regulated private sector in 2015 who were victims of sexual assault (inside or outside of the workplace), 12,300 of whom were women.

To this end, the Labour Program is examining the parts of the Canada Labour Code (Code) that deal with violence and harassment. We are assessing whether they:

- ensure that mechanisms are in place to prevent and respond to violence and harassment in federally regulated workplaces

- clearly define roles and responsibilities

- reflect best practices

If we find that they do not, we will look for ways to correct this.

The Honourable Patty Hajdu, Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour, is consulting with stakeholders, civil society organizations, experts and others to hear their views.

Context

The current legal framework for dealing with violence and harassment in federally regulated workplaces is set out in the Code (and related regulations).

Violence prevention in the workplace, which includes harassment, is addressed in Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) of the Code. Part II applies to the federally regulated private sector (for example, banking, international and inter-provincial rail, air and road transportation, marine shipping, broadcasting and telecommunications), federal Crown corporations and the federal public service.

Sexual harassment is addressed in Part III (Labour Standards) of the Code, which applies to federally regulated private sector workplaces and federal Crown corporations. It does not apply to the federal public service.

Issues for discussion

General

- What are the strengths and shortcomings of the current framework under the Code for preventing and responding to violence and harassment in the workplace?

- How do you define the terms “violence” and “harassment”? Should they be treated as related or different?

- Under the Code, what should be the roles and responsibilities of employers, employees, workplace health and safety committees and others in:

- preventing and responding to violence in the workplace

- supporting victims and others who are affected by it

- preventing and responding to harassment in the workplace

- supporting victims and others who are affected by it

- Should violence, sexual assault and harassment be treated in the same way under the Code? If not, why? If yes, should they be addressed under Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) or Part III (Labour Standards)? What changes, if any, would you recommend for the current framework and why?

- What types of measures could be taken in the workplace to better protect and support victims of domestic violence?

- What best practices, set out by law or otherwise, are you aware of in Canada and in other countries to:

- prevent violence and harassment in the workplace

- respond to incidents when they occur

- provide support to victims and others

Compliance and enforcement

- What tools for compliance and enforcement are most effective for preventing and reducing incidents and resolving complaints quickly and appropriately?

- Who should monitor employer responses to incidents? How should repeated non-compliance be handled?

Training and awareness

- Are you aware of any best practices in awareness-building, education and training that could assist in promoting zero tolerance for violence or harassment?

Data analysis and monitoring results

- How should we monitor and measure progress in preventing and reducing incidents and resolving complaints quickly and appropriately? Why?

ESDC consultation and engagement activities privacy notice statement

Purpose of the collection

Consultation and engagement is defined as a process where Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) invites organizations and/or individuals to provide their views on a variety of topics— to help develop better, more informed and more effective policies, programs and services.

Activities include, but are not limited to:

- in-person meetings or events (roundtable meetings or meetings with stakeholders, town halls, public meetings, forums, workshops, advisory committees)

- online consultations (surveys, discussion forums, social media)

- oral or written submissions (telephone, email, fax or mail)

Participation is voluntary

Participation in all ESDC consultation and engagement activities is voluntary. Acceptance or refusal to participate will in no way affect your relationships with ESDC or the Government of Canada.

ESDC’s authority to collect information

Your personal information is collected under the authority of the Department of Employment and Social Development Act (DESDA).

Your personal information will be managed and administered in accordance with DESDA, the Privacy Act and other applicable laws.

Uses and disclosures of your personal information

Uses and/or disclosures of your personal information will never result in an administrative decision being made about you. Your personal information will be used by ESDC, other Government of Canada departments or other levels of government for policy analysis, research, program operations and/or communications.

Handling of your personal information

Information provided for ESDC consultation and engagement activities should not include any identifying personal information about you or anyone else—other than your name, organization and contact information.

If your feedback includes unsolicited personal information for the purpose of attribution, ESDC may choose to include this information in publicly available reports on the consultation and elsewhere.

If personal information is provided by an individual member of the general public (who is not participating on behalf of an organization), ESDC will remove it prior to including the individual’s responses in the data analysis, unless otherwise noted.

Your rights

You have the right to the protection of, access to and correction of your personal information, which is described in Personal Information Bank ESDC-PSU-914 or ESDC-PSU-938.

Instructions for obtaining this information are outlined in ESDC Info Source. Info Source may also be accessed online at any Service Canada Centre.

You have the right to file a complaint with the Privacy Commissioner of Canada regarding ESDC’s handling of your personal information.

Open government

Your submission, or portions thereof, may be published on Canada.ca or included in publicly available reports on the consultation; it may also be compiled with other responses to the consultation in an open-data submission on Open.Canada.ca, or shared throughout the Government of Canada or with other levels of government.

Labour Program

Employment and Social Development Canada

March 2017